Validating Genome-Scale Models: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Translation

The predictive power of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) is revolutionizing biomedical research, from identifying novel drug targets to engineering microbial cell factories.

Validating Genome-Scale Models: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Translation

Abstract

The predictive power of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) is revolutionizing biomedical research, from identifying novel drug targets to engineering microbial cell factories. However, the true value of these in silico predictions hinges on rigorous and multi-faceted validation strategies. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the current best practices, common pitfalls, and emerging frontiers in GEM validation. We explore the foundational concepts of model reconstruction and curation, detail methodological advances for simulating phenotypes and integrating multi-omic data, address troubleshooting and optimization techniques to overcome prediction limitations, and finally, present a framework for the comparative analysis and benchmarking of model performance against robust experimental datasets. Mastering these validation principles is paramount for building confidence in model-driven hypotheses and accelerating their translation into clinical and biotechnological breakthroughs.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles of Building and Curating Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational frameworks in systems biology that mathematically represent an organism's metabolism. Their core components work in concert to enable the simulation and prediction of metabolic phenotypes under various genetic and environmental conditions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these components—the stoichiometric matrix, Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules, and biomass objectives—focusing on their roles in the validation of model predictions.

Stoichiometric Matrix: The Biochemical Backbone

The stoichiometric matrix forms the mathematical foundation of any GEM. This matrix, denoted as S, encapsulates the stoichiometry of all metabolic reactions in the network.

Definition and Function: The matrix defines the interconnection between metabolites and reactions. If the network contains m metabolites and n reactions, S is an m × n matrix where each element Sᵢⱼ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [1]. The fundamental equation

S · v = 0describes the system at steady-state, wherevis the vector of reaction fluxes (metabolic reaction rates) [1]. This equation represents the mass-balance constraint, ensuring that the total production and consumption of each internal metabolite are balanced.Role in Validation: The structure of the S matrix directly determines the network's capabilities. During validation, the model's ability to perform a set of defined metabolic tasks is tested by applying different constraints to the inputs and outputs of metabolites and checking if a feasible flux vector exists [1]. A model that fails to perform an essential metabolic task indicates a gap or error in the stoichiometric matrix that requires curation.

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules: Connecting Genotype to Phenotype

GPR rules are logical Boolean statements that associate genes with the metabolic reactions they enable, creating a direct link between an organism's genotype and its metabolic phenotype.

Structure and Logic: GPR rules typically take the form of "AND" and "OR" logic. An "AND" relationship (

gene1 AND gene2) indicates that the gene products form a protein complex essential for the reaction's catalysis. An "OR" relationship (gene1 OR gene2) signifies that multiple isozymes can catalyze the same reaction independently [1] [2].Application in Model Validation and Essentiality Prediction: GPRs are crucial for predicting gene essentiality. The concept of genetic Minimal Cut Sets (gMCS) relies on GPRs to identify minimal sets of genes whose simultaneous inactivation is required to prevent an unwanted metabolic state, such as biomass production or the execution of an essential metabolic task [1]. The quality of GPR associations directly impacts the accuracy of these predictions. Advanced tools like GEMsembler can optimize GPR combinations from consensus models, which has been shown to improve gene essentiality predictions even in manually curated gold-standard models [3].

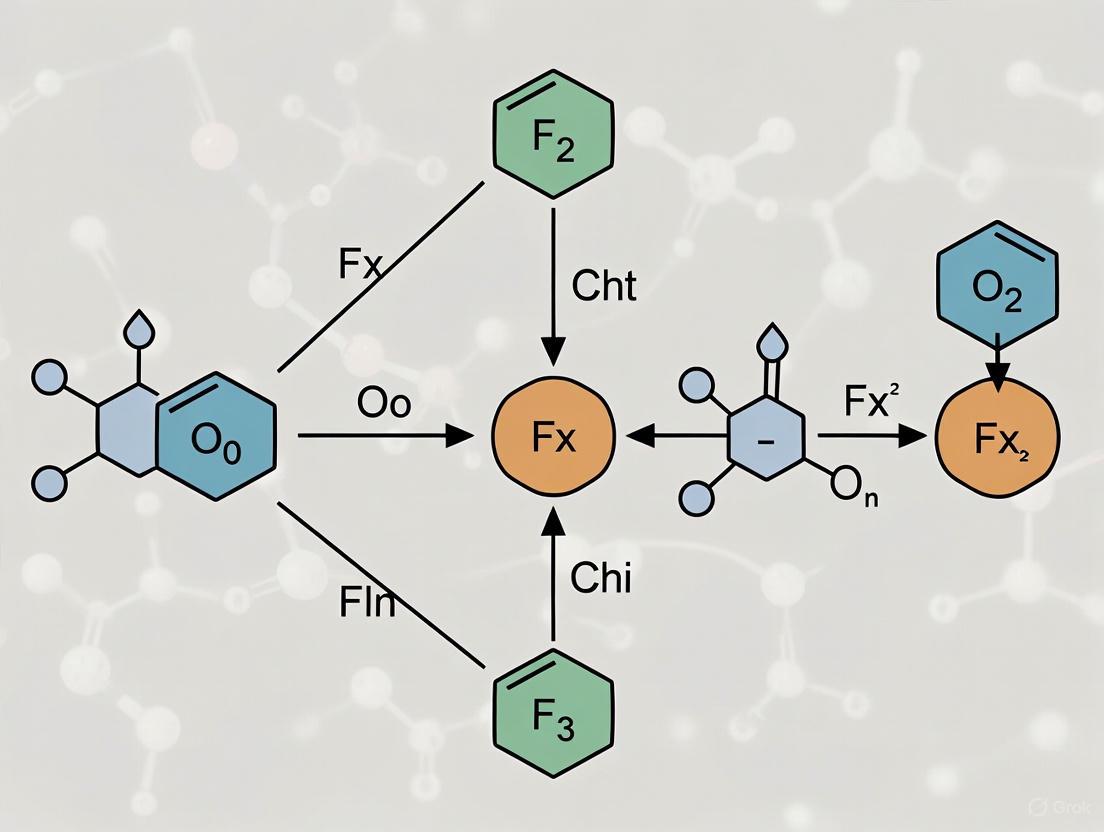

The following diagram illustrates how these core components integrate within a GEM and are used for validation.

Biomass Objectives: From Growth to Functional Tasks

The biomass objective function is a critical component that mathematically represents the biological goal of the modeled cell. It quantifies the drain of metabolic precursors and energy required to form a new unit of cell mass.

The Traditional Growth-Centric View: In classical GEM simulations, particularly for microbes and cancer cells, maximizing the flux through the biomass reaction is often the default objective, based on the assumption that cells evolve to maximize growth [4] [2]. Methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) use this objective to predict metabolic fluxes and growth phenotypes [4].

Beyond Growth: The Essential Metabolic Tasks: The assumption of biomass maximization is an oversimplification for many cell types, such as quiescent human cells (e.g., neurons, muscle cells) which prioritize tissue-specific functions over proliferation [4]. This limitation has spurred the expansion of objective functions to include essential metabolic tasks. These are biochemical functions indispensable for the survival and operation of any human cell, such as ATP rephosphorylation, nucleotide synthesis, and phospholipid turnover [1]. For human GEMs, a list of 57 crucial metabolic tasks has been identified, which can be grouped into broader categories like energy supply, internal conversion processes, and synthesis of metabolites [1].

Comparative Analysis: Biomass vs. Metabolic Tasks as Objectives

The choice of objective function significantly impacts model predictions and their validation. The table below compares the use of a biomass objective versus metabolic tasks in the context of identifying genetic targets and toxicities.

Table 1: Comparing the Impact of Biomass vs. Metabolic Task Objectives in Human GEMs

| Aspect | Biomass Objective Alone | Biomass + Metabolic Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Prevent cell proliferation [1]. | Prevent proliferation and disrupt essential cellular functions [1]. |

| Therapeutic Target Identification | Identifies gene knockouts that stop growth. | Reveals additional, potentially more selective targets that cripple core cellular functions [1]. |

| Toxicity Assessment (gMCS) | Detects generic toxicities that prevent any cell growth [1]. | Uncovers a wider spectrum of toxicities that could damage specialized healthy tissues [1]. |

| Quantitative Outcome (Example) | In the generic Human1 model, 106 generic toxicities were detected [1]. | The number of detected generic toxicities increased to 281 (136 single genes, 49 gene pairs) [1]. |

| Biological Relevance | Reasonable for rapidly proliferating cells (e.g., bacteria, cancers) [4]. | Essential for modeling non-proliferative cells and for comprehensive toxicity screening [4] [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Core Components

Validation is crucial for ensuring GEM predictions are biologically accurate. Below are protocols for key validation experiments tied to the core components.

Protocol 1: Gene Essentiality Prediction

This protocol validates the GPR associations and network connectivity.

- In Silico Simulation: For each gene in the model, simulate a gene knockout by constraining the flux of all reactions associated with that gene (via its GPR rules) to zero.

- Phenotype Prediction: Calculate the maximum biomass yield or check the feasibility of essential metabolic tasks in the knocked-out model using FBA.

- Classification: A gene is predicted as "essential" if the biomass yield falls below a threshold (e.g., <5% of wild-type) or if a critical metabolic task cannot be performed.

- Experimental Validation: Compare predictions against experimental data from genome-wide knockout libraries (e.g., for yeast S. cerevisiae) or essentiality databases.

- Metric Calculation: Assess prediction accuracy using metrics like precision (fraction of correct essential gene predictions) and recall (fraction of true essential genes identified) [3].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Task Validation

This protocol validates the completeness of the stoichiometric matrix and the defined biomass objective.

- Task Definition: Compile a list of essential metabolic tasks the model must perform, such as ATP production from glucose or the synthesis of a key metabolite [1].

- In Silico Testing: For each task, formulate the model constraints. For a "production task," the lower bound for the metabolite exchange reaction is set to a small positive value, and the model checks for a feasible solution. For a "connection task," the consumption of a source and production of a target metabolite are enabled simultaneously [1].

- Gap Analysis: If a task fails, inspect the network for missing reactions or incorrect stoichiometry in the S matrix. This guides manual curation.

- Context-Specific Validation: Ensure that models for specific tissues (e.g., liver, heart) can perform tasks relevant to their physiological function [1].

Protocol 3: Auxotrophy Prediction

This protocol tests the model's ability to simulate growth on different media, validating the network's nutrient utilization pathways.

- Media Definition: Define the composition of the minimal media in the model by opening the exchange reactions for the available nutrients (e.g., glucose, ammonium, phosphate) and closing all others.

- Growth Simulation: Perform FBA with biomass maximization as the objective to predict the growth rate.

- Auxotrophy Identification: If no growth is predicted, sequentially open exchange reactions for one absent metabolite at a time (e.g., an amino acid or vitamin). A metabolite whose availability enables growth is identified as a required nutrient, indicating an auxotrophy.

- Benchmarking: Compare the predicted auxotrophies with experimental growth profiles to assess model accuracy [3].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Resources for GEM Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| AGORA2 [5] | Database | Repository of 7,302 curated, strain-level GEMs of human gut microbes. Used to screen for interspecies interactions and LBP candidates. |

| Human-GEM / Human1 [1] | Model | A generic, consensus GEM of human metabolism. Serves as a template for generating context-specific models of tissues and cell lines. |

| GEMsembler [3] | Software Tool | A Python package that compares, analyzes, and builds consensus models from multiple input GEMs, improving predictions for auxotrophy and gene essentiality. |

| RAVEN Toolbox [1] [2] | Software Tool | A MATLAB toolbox used for the reconstruction, curation, and simulation of GEMs, including the generation of context-specific models via the ftINIT algorithm. |

| COBRApy [1] | Software Tool | A Python package for constraint-based modeling of metabolic networks. Used for running FBA, FVA, and other core simulations. |

| Gene Knockout Library (e.g., for yeast) | Experimental Data | A collection of mutant strains, each with a single gene deletion. Provides gold-standard data for validating model predictions of gene essentiality. |

| Pandora Spectrometer [6] | Instrument | Note: Used for atmospheric GEM validation. Included here as an example of physical validation apparatus. Provides high-precision ground-truth data for validating satellite-derived atmospheric models. |

The core components of a GEM—the stoichiometric matrix, GPR rules, and biomass objectives—form an integrated system for translating genomic information into predictive metabolic models. Moving beyond a simplistic biomass maximization objective to include essential metabolic tasks has proven to significantly enhance the predictive power and biological relevance of GEMs, especially in biomedical applications like drug target discovery and toxicity assessment. As the field progresses, the continued refinement of these components through rigorous validation against experimental data remains paramount for advancing systems biology and accelerating therapeutic development.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMS) serve as powerful computational frameworks that integrate genes, metabolic reactions, and metabolites to simulate metabolic flux distributions under specific conditions [7]. The reconstruction pipeline for these models begins with genome annotation, proceeds through draft model construction, and culminates in manual curation—a process that significantly determines model predictive accuracy and biological relevance. The validation of GSMM predictions fundamentally depends on this pipeline, as inaccurate annotations propagate errors through subsequent model construction and simulation phases.

Annotation heterogeneity presents a substantial challenge in comparative genomics, where different annotation methods can erroneously identify lineage-specific genes. Studies demonstrate that annotation heterogeneity increases apparent lineage-specific genes by up to 15-fold, highlighting how methodological differences rather than biological reality can drive findings [8]. This annotation variability directly impacts metabolic reconstructions, as inconsistent gene assignments lead to incomplete or incorrect reaction networks.

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Methodologies

Automated vs. Manual Curation Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Reconstruction Pipelines

| Method | Key Tools/Platforms | Advantages | Limitations | Validation Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Reconstruction | Model SEED [9] [7], RAVEN Toolbox [9] | High-throughput capability; rapid draft model generation | Potential for annotation errors and metabolic gaps | 71.6%-79.6% agreement with experimental gene essentiality data [7] |

| Manual Curation | COBRA Toolbox [9] [7], BLASTp [7], MEMOTE | Addresses metabolic gaps; incorporates physiological data | Labor-intensive process; requires expert knowledge | 74% MEMOTE score for curated S. suis model [7] |

| Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic | Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) [10] | Improves quantitative phenotype predictions; requires smaller training sets | Complex implementation; emerging methodology | Systematically outperforms constraint-based models [10] |

Quantitative Assessment of Model Performance

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Organism | Model Name | Genes | Reactions | Metabolites | Experimental Validation Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus suis | iNX525 [7] | 525 | 818 | 708 | 71.6%-79.6% gene essentiality prediction |

| Escherichia coli | iML1515 [10] | 1,515 | 2,666 | 1,875 | Basis for hybrid model improvements [10] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Not specified | 3,238 knockout strains analyzed [11] | - | - | 98.3% true-positive rate for GO assignment [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Reconstruction Validation

Model Construction and Gap-Filling Methodology

The standard protocol for GSMM reconstruction begins with genome annotation using platforms such as RAST, followed by automated draft construction with ModelSEED [7]. The critical manual curation phase involves:

- Homology-Based GPR Association: Using BLASTp with thresholds of ≥40% identity and ≥70% match length against reference organisms to assign gene-protein-reaction (GPR) relationships [7].

- Metabolic Gap Analysis: Employing the

gapAnalysisprogram in the COBRA Toolbox to identify and fill metabolic gaps through biochemical database consultation and literature mining [7]. - Biomass Composition Definition: Curating organism-specific biomass equations based on experimental data or phylogenetically related organisms [7].

- Stoichiometric Balancing: Checking and correcting mass and charge imbalances using the

checkMassChargeBalanceprogram [7].

Phenotypic Validation Experiments

Growth assays under defined conditions provide critical validation data. For bacterial models like S. suis:

- Cultivate strains in complete chemically defined medium (CDM) during logarithmic growth phase [7]

- Perform leave-one-out experiments by systematically excluding specific nutrients from CDM [7]

- Measure optical density at 600nm at 15 hours and normalize growth rates to complete CDM [7]

- Compare in silico growth predictions with experimental measurements across multiple conditions

Machine Learning-Enhanced Function Prediction

For predicting gene functions beyond homology-based methods:

- Generate MALDI-TOF mass fingerprints from knockout libraries (e.g., 3,238 S. cerevisiae knockouts) [11]

- Convert mass spectra (m/z 3,000-20,000) to 1,700-digit binary vectors at 10 m/z intervals [11]

- Train support vector machine (SVM) and random forests algorithms on known gene ontology terms [11]

- Validate predictions with metabolomics analysis of intracellular metabolite changes in predicted knockouts [11]

Workflow Visualization: Reconstruction Pipeline

Figure 1: GSMM Reconstruction and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GSMM Reconstruction

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Reconstruction | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [9] [7] | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Gap filling, model validation, and flux balance analysis [7] |

| ModelSEED [9] [7] | Automated platform for high-throughput draft model construction | Initial draft reconstruction from RAST annotations [7] |

| GUROBI Optimizer [7] | Mathematical optimization solver for FBA simulations | Solving linear programming problems in metabolic flux calculations [7] |

| RAST [7] | Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology for genome annotation | Initial functional annotation of target genomes [7] |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [7] | Manually annotated protein knowledgebase | BLASTp searches for GPR assignments [7] |

| MEMOTE [7] | Community-developed metric for model quality assessment | Quality scoring of curated models (e.g., 74% for iNX525) [7] |

| Chemically Defined Media [7] | Precisely controlled growth conditions for model validation | Leave-one-out experiments for phenotypic testing [7] |

Advanced Approaches: Enhancing Predictive Power

Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic Modeling

The artificial metabolic network (AMN) approach embeds FBA within artificial neural networks to overcome limitations in quantitative phenotype predictions [10]. This hybrid methodology:

- Replaces Simplex solvers with differentiable alternatives (Wt-solver, LP-solver, QP-solver) to enable gradient backpropagation [10]

- Uses a neural preprocessing layer to predict medium uptake fluxes from extracellular concentrations [10]

- Requires training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods [10]

- Systematically outperforms traditional constraint-based models while maintaining mechanistic constraints [10]

Mass Fingerprinting for Functional Annotation

MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting of knockout libraries provides an annotation-independent approach for gene function prediction [11]. This experimental methodology:

- Achieves average AUC values of 0.994 and 0.980 with random forests and SVM algorithms, respectively, for GO term assignment [11]

- Captures functional changes in proteome and metabolome not inferable from sequence information alone [11]

- Enables functional predictions for proteins lacking sequence homology to characterized proteins [11]

- Successfully suggested new functions for 28 previously uncharacterized yeast genes [11]

The reconstruction pipeline from genome annotation to manual curation remains foundational for developing predictive genome-scale metabolic models. Integration of machine learning approaches with traditional constraint-based modeling demonstrates significant potential for enhancing predictive accuracy while addressing the inherent limitations of both automated and manual curation methods. As hybrid modeling approaches mature and experimental validation methodologies advance, the reconstruction pipeline will continue to evolve, providing increasingly robust platforms for metabolic engineering and drug target identification.

In the rapidly advancing field of genomic artificial intelligence, the pursuit of biologically accurate and clinically relevant models hinges on a critical, yet often underestimated component: the development of robust benchmark training sets. These carefully curated datasets serve as the "gold standard" for both training and evaluating models, ensuring that performance metrics reflect true biological understanding rather than computational artifacts. The emergence of powerful genomic language models (gLMs) like Evo2, with 40 billion parameters trained on over 128,000 genomes, has intensified the need for rigorous benchmarking practices [12]. Without standardized evaluation frameworks, even the most sophisticated models may fail to translate their computational prowess into genuine biological insight or clinical utility.

This comparison guide examines current benchmark suites across genomic and drug discovery applications, evaluating their composition, implementation, and effectiveness in refining model performance. By objectively analyzing experimental data and methodologies, we provide researchers with a comprehensive resource for selecting appropriate gold standards that drive meaningful model refinement in genome-scale prediction research.

Comparative Analysis of Genomic and Drug Discovery Benchmark Suites

The table below summarizes key benchmark suites used for training and evaluating genomic and drug discovery models, highlighting their scope, strengths, and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Benchmark Suites for Model Refinement

| Benchmark Suite | Primary Application Domain | Key Tasks & Metrics | Notable Features | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNALONGBENCH [13] | Genomic DNA Prediction | 5 tasks including enhancer-target gene interaction, 3D genome organization; AUROC, AUPR, Pearson correlation | Long-range dependencies up to 1 million base pairs; most comprehensive long-range benchmark | Expert models consistently outperform DNA foundation models; contact map prediction most challenging (0.042-0.733 score range) |

| BEND [14] | Genomic Sequence Analysis | 4 tasks: gene finding, chromatin accessibility, histone modification, CpG methylation; AUROC, MCC | Framed as sequence labeling tasks; enables self-pretraining approaches | Self-pretraining improved gene finding MCC from 0.50 to 0.64; CRF augmentation substantially boosts performance |

| WelQrate [15] | Small Molecule Drug Discovery | 9 datasets across 5 therapeutic target classes; hit rate prediction, virtual screening | Hierarchical curation with confirmatory/counter screens; PAINS filtering | Covers realistically imbalanced data (0.039%-0.682% active compounds); spans GPCRs, kinases, ion channels |

| gLM Evaluation [12] | Genomic Language Models | Zero-shot performance, variant effect prediction, regulatory element identification | Focuses on distinguishing understanding vs. memorization | Current gLMs often learn token frequencies rather than complex contextual relationships |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Analysis

DNALONGBENCH Implementation and Results

DNALONGBENCH addresses a critical gap in long-range genomic dependency modeling by providing five biologically significant tasks spanning up to 1 million base pairs [13]. The benchmark employs rigorous evaluation protocols comparing three model classes: (1) task-specific expert models, (2) convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and (3) fine-tuned DNA foundation models including HyenaDNA and Caduceus variants.

The evaluation methodology demonstrates that highly parameterized expert models consistently outperform DNA foundation models across all tasks [13]. This performance gap is particularly pronounced in regression tasks such as contact map prediction and transcription initiation signal prediction, where foundation models struggle to capture sparse real-valued signals. For example, in transcription initiation signal prediction, the expert model Puffin achieved an average score of 0.733, significantly surpassing CNN (0.042) and foundation models (approximately 0.11) [13].

Table 2: Detailed DNALONGBENCH Task Performance Comparison

| Task | Expert Model | CNN | HyenaDNA | Caduceus-PS | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancer-Target Gene Prediction | ABC Model | Three-layer CNN | Fine-tuned foundation model | Fine-tuned foundation model | AUROC, AUPR |

| Contact Map Prediction | Akita | CNN with 1D/2D layers | Fine-tuned with linear layers | Fine-tuned with linear layers | Stratum-adjusted correlation, Pearson correlation |

| eQTL Prediction | Enformer | Three-layer CNN | Reference/allele sequence concatenation | Reference/allele sequence concatenation | AUROC, AUPRC |

| Regulatory Sequence Activity | Enformer | CNN with Poisson loss | Feature vector extraction | Feature vector extraction | Task-specific regression metrics |

| Transcription Initiation Signals | Puffin-D | CNN with MSE loss | Feature vector extraction | Feature vector extraction | Average score (0.733 expert vs ~0.11 foundation) |

BEND Benchmark and Self-Pretraining Methodologies

The BEND benchmark provides an alternative approach through task-specific self-pretraining, challenging the convention that pretraining on the full human genome is always necessary for strong performance [14]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Architecture: A residual CNN encoder with 30 convolutional layers (kernel size 9), 512 hidden channels, and dilation doubling each layer (reset every 6 layers, maximum 32)

- Self-Pretraining: Masked language modeling on unlabeled task-specific sequences with 15% masking probability and standard 80/10/10 replacement strategy

- Fine-Tuning: Replacement of MLM head with task-specific predictors (two-layer CNN with linear output layer)

- Structured Prediction Enhancement: Addition of neural linear-chain Conditional Random Fields for gene finding to model label dependencies

This methodology demonstrates that self-pretraining matches or exceeds scratch training under identical compute budgets, with particular success in gene finding (MCC improvement from 0.50 to 0.64) and CpG methylation prediction (5-point absolute improvement) [14]. The CRF augmentation proves especially valuable for enforcing biologically consistent label transitions, mimicking the structured approach of established tools like Augustus.

WelQrate Curation Pipeline for Drug Discovery

WelQrate addresses critical data quality issues in small molecule benchmarking through a rigorous hierarchical curation process [15]:

- Related Bioassays Identification: Manual inspection of PubChem bioassay descriptions to establish relationships and experimental details

- Data Retrieval: Selection based on therapeutic relevance, established protocols with validation screens, and consistent measurement units

- Hierarchical Curation: Utilization of primary, confirmatory, and counter-screen data to minimize false positives

- Domain-Driven Filtering: Application of Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) filtering and chemical structure standardization

- Multi-Format Output: Provision of standardized formats including isomeric SMILES, InChI, SDF, and 2D/3D graph representations

This meticulous process yields high-quality datasets with realistic imbalance (0.039%-0.682% active compounds) that reflect true high-throughput screening challenges, enabling more reliable virtual screening model development [15].

Visualization of Benchmark Evaluation Workflows

Genomic Benchmark Evaluation Pipeline

Self-Pretraining Methodology for Genomic Models

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Model Development

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENCODE Data [14] | Experimental Dataset | Provides ground truth labels for regulatory genomics | Chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, gene expression across cell lines |

| GENCODE Annotations [14] | Genome Annotation | Gold standard for gene structure evaluation | Comprehensive exon-intron boundaries, splice sites, non-coding regions |

| PubChem BioAssays [15] | Chemical Screening Database | Source for small molecule activity data | Primary, confirmatory, and counter-screen data with established protocols |

| COBRA Methods [16] | Metabolic Modeling Framework | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks | Biochemical, genetically, and genomically structured knowledge bases (BiGG k-bases) |

| ResNet CNN Encoder [14] | Model Architecture | Base feature extractor for genomic sequences | 30 convolutional layers with dilation, 512 hidden channels, GELU activation |

| Conditional Random Fields [14] | Structured Prediction Layer | Models label dependencies in sequence labeling | Captures biological transition constraints (e.g., exon-intron boundaries) |

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparative analysis reveals that while benchmark suites share the common goal of standardizing model evaluation, their effectiveness depends heavily on how well they capture biologically meaningful challenges. DNALONGBENCH excels in addressing long-range genomic dependencies—a critical frontier in regulatory genomics [13]. Meanwhile, BEND's demonstration of effective self-pretraining offers a compute-efficient alternative to full-genome pretraining, particularly valuable for researchers with limited computational resources [14].

A concerning finding across multiple studies is that current genomic language models, despite their scale, often fail to outperform well-tuned supervised baselines and sometimes prioritize memorization over genuine understanding [12] [14]. This underscores the importance of benchmarks that can distinguish between these capabilities, pushing the field beyond pattern recognition toward true biological insight.

Future benchmark development should prioritize several key areas: (1) incorporation of more diverse genetic contexts beyond reference genomes, (2) standardized evaluation of model interpretability and biological plausibility, (3) integration of multi-modal data including epigenetic and structural information, and (4) development of more sophisticated metrics that quantify model robustness across population variants and experimental conditions.

Gold standard training sets represent far more than mere performance benchmarks—they embody the scientific community's consensus on biologically meaningful challenges and proper evaluation methodologies. As genomic models grow in complexity and scale, the role of these carefully curated datasets becomes increasingly critical for ensuring that computational advances translate into genuine biological understanding and clinical impact.

The benchmark suites examined herein provide diverse but complementary approaches to this challenge, from DNALONGBENCH's focus on long-range dependencies to WelQrate's rigorous small-molecule curation. By selecting appropriate benchmarks that align with their specific research questions and employing methodologies like self-pretraining and structured prediction, researchers can significantly enhance model refinement outcomes. Ultimately, continued investment in benchmark development remains essential for bridging the gap between computational performance and biological relevance in genome-scale predictive modeling.

In the field of genome-scale model research, robust validation is paramount for assessing the predictive power of computational tools. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy form the foundational triad of metrics used to quantitatively evaluate model performance against experimental data. These metrics provide researchers with standardized measures to judge how well their models correctly identify true positive cases (sensitivity), true negative cases (specificity), and overall correctness of positive predictions (predictive accuracy) [17]. As genome-scale modeling techniques become increasingly sophisticated—from metabolic models guiding live biotherapeutic development to machine learning approaches predicting gene deletion effects [5] [18]—understanding these validation metrics becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on model predictions to guide experimental design and therapeutic development.

The interdependence of these metrics necessitates a balanced approach to validation. A model with high sensitivity minimizes false negatives, while high specificity reduces false positives; predictive accuracy, often expressed through positive and negative predictive values, adds crucial context about a test's practical utility in specific populations [17] [19]. This guide examines these metrics within the context of genome-scale model validation, providing structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to empower researchers in their model development and assessment workflows.

Fundamental Definitions and Mathematical Foundations

Core Metric Definitions and Calculations

The validation of genome-scale models relies on precise mathematical definitions for each key metric, derived from counts of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) [17]:

Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): The proportion of actual positive cases that a model correctly identifies. It quantifies a model's ability to detect the phenomenon of interest when it exists [17]. Calculated as: Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN).

Specificity (True Negative Rate): The proportion of actual negative cases that a model correctly identifies. It measures a model's ability to exclude cases without the target condition [17]. Calculated as: Specificity = TN / (TN + FP).

Positive Predictive Value (PPV) (Precision): The probability that a case identified as positive truly is positive. This metric indicates the reliability of positive predictions [17] [19]. Calculated as: PPV = TP / (TP + FP).

Negative Predictive Value (NPV): The probability that a case identified as negative truly is negative, indicating the reliability of negative predictions [17] [19]. Calculated as: NPV = TN / (TN + FN).

Accuracy: The overall correctness of the model across both positive and negative cases [19]. Calculated as: Accuracy = (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN).

Critical Relationships and Tradeoffs

These validation metrics exhibit fundamental mathematical relationships that researchers must consider when evaluating genome-scale models:

Inverse Relationship: Sensitivity and specificity typically have an inverse relationship; increasing one often decreases the other, requiring researchers to balance these metrics based on their specific application [17].

Prevalence Dependence: While sensitivity and specificity are considered intrinsic test properties, predictive values (PPV and NPV) are highly dependent on disease prevalence in the study population [17]. A model with fixed sensitivity and specificity will yield different PPV and NPV values when applied to populations with different prevalence rates of the target condition.

Likelihood Ratios: These metrics combine sensitivity and specificity into single indicators of diagnostic power. The positive likelihood ratio (LR+) equals Sensitivity / (1 - Specificity), while the negative likelihood ratio (LR-) equals (1 - Sensitivity) / Specificity [17]. Unlike predictive values, likelihood ratios are not influenced by disease prevalence.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these core validation metrics and their application in genome-scale model research:

Figure 1: Logical relationships between core validation metrics and their derivation from experimental results. Metrics are calculated from confusion matrix components (TP, TN, FP, FN) and collectively inform model validation.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches in Genome-Scale Research

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

Different computational approaches for genome-scale model predictions exhibit distinct strengths and weaknesses in sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of prominent methods based on recent research:

Table 1: Performance comparison of genome-scale model validation methods

| Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Predictive Accuracy | Best Application Context | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [18] | Moderate | High | ~93.5% (E. coli) | Gene essentiality prediction in microbes | Fast computation; Well-established framework | Requires optimality assumption; Performance drops in complex organisms |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [18] | High | High | ~95% (E. coli) | Metabolic gene deletion phenotypes | No optimality assumption; Superior accuracy vs. FBA | Computationally intensive; Large memory requirements |

| Machine Learning on MALDI-TOF Fingerprints [11] | 0.983 (SVM) | 0.993 (SVM) | AUC: 0.980-0.994 | Gene function prediction from mass spectra | High-throughput; Does not require sequence homology | Requires extensive training data; Specialized equipment needed |

| ROC Curve Multi-Parameter Optimization [19] | Adjustable via cutoff | Adjustable via cutoff | Varies with prevalence | Biomarker validation; Diagnostic cutoff determination | Enables balanced tradeoffs between metrics | Complex implementation; Population-specific results |

Advanced Metric Integration Frameworks

Recent methodological advances enable more sophisticated integration of multiple validation metrics:

Multi-Parameter ROC Analysis: Traditional sensitivity-specificity ROC curves have been expanded to include precision (PPV), accuracy, and predictive values in a single graph with integrated cutoff distribution curves [19]. This approach allows researchers to identify optimal cutoff values that balance multiple diagnostic parameters simultaneously, rather than maximizing a single metric like the Youden index (Sensitivity + Specificity - 1).

Prevalence-Aware Validation: Since PPV and NPV depend on disease prevalence, proper validation of genome-scale models requires testing in populations with different prevalence rates or mathematically adjusting for expected prevalence in target applications [17]. A model demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity in a high-prevalence research cohort may show markedly different PPV when applied to general screening populations with lower prevalence.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Protocol 1: Validation of Gene Essentiality Predictions

This protocol outlines the procedure for validating predictions of metabolic gene essentiality using Flux Cone Learning (FCL), based on the methodology that achieved 95% accuracy in E. coli [18]:

Training Data Preparation:

- Obtain genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for target organism (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli)

- Generate Monte Carlo samples (recommended: 100 samples/cone) for each gene deletion mutant

- Compile experimental fitness labels for each deletion from essentiality screens

- Format feature matrix with dimensions (k × q rows × n columns), where k = number of gene deletions, q = samples per deletion cone, and n = number of reactions in GEM

Model Training:

- Implement random forest classifier using 80% of deletion mutants for training

- Remove biomass reaction from training data to prevent model from learning this direct correlation

- Train model on flux samples with corresponding essentiality labels

Model Validation:

- Test trained model on remaining 20% of held-out gene deletions

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy using standard formulas

- Compare performance against FBA predictions using the same test set

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Perform feature importance analysis to identify reactions most predictive of essentiality

- Calculate distance metrics between deletion and wild-type strain flux cones

- Validate top predictions with targeted experimental gene deletions

Protocol 2: MALDI-TOF Fingerprinting for Gene Function Prediction

This protocol describes the validation of gene function predictions using mass fingerprinting and machine learning, which achieved sensitivity of 0.983 and specificity of 0.993 with SVM classifiers [11]:

Sample Preparation:

- Culture yeast knockout library strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae deletion collection) in 96-well plates

- Perform automatic high-throughput cell extraction with formic acid

- Prepare matrix solution with sinapinic acid (SA) for MALDI-TOF analysis

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Perform MALDI-TOF analysis across mass range m/z 3,000-20,000

- Convert spectra to binary vectors by dividing into 1,700 segments at 10 m/z intervals

- Quality control: exclude spectra with poor peak resolution or high background noise

Machine Learning Classification:

- Correlate digitized mass fingerprints with Gene Ontology (GO) annotations

- Train support vector machine (SVM) and random forest algorithms

- Implement k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting

Function Prediction and Validation:

- Apply trained models to predict functions for uncharacterized gene knockouts

- Validate predictions with metabolomics analysis of selected knockout strains

- Confirm predicted metabolic alterations (e.g., changed methionine-related metabolites in methylation-related knockouts)

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for validating genome-scale models using multiple experimental approaches:

Figure 2: Integrated workflow for genome-scale model validation combining mass fingerprinting, metabolic modeling, and multi-parameter statistical analysis.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for genome-scale model validation

| Category | Specific Product/Resource | Application in Validation | Key Features | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Collections | S. cerevisiae Deletion Collection (Invitrogen) | Comprehensive knockout library for functional validation | 4,847 single-gene knockout strains; 96-well format | Gene function prediction via mass fingerprinting [11] |

| Metabolic Models | AGORA2 | Curated GEMs for 7,302 human gut microbes | Strain-level reconstruction; Community modeling | Top-down LBP candidate screening [5] |

| Mass Spectrometry | MALDI-TOF with Sinapinic Acid Matrix | High-throughput mass fingerprinting | m/z 3,000-20,000 range; Minimal sample prep | Functional profiling of knockout libraries [11] |

| Sampling Algorithms | Monte Carlo Samplers | Flux cone characterization for FCL | Random sampling of feasible flux space | Training data for phenotype prediction [18] |

| Machine Learning | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Classification of mass fingerprints | High specificity (0.993) and sensitivity (0.983) | Gene Ontology term assignment [11] |

| Validation Frameworks | Multi-Parameter ROC Analysis | Optimal cutoff determination | Integrates sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV | Biomarker validation and cutoff optimization [19] |

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy provide the fundamental framework for validating genome-scale models across diverse applications, from metabolic engineering to therapeutic development. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that method selection significantly impacts validation outcomes, with emerging approaches like Flux Cone Learning and MALDI-TOF fingerprinting with machine learning offering superior performance characteristics for specific applications. As the field advances, integration of multiple metrics through frameworks like multi-parameter ROC analysis will enable more nuanced model validation that balances the inherent tradeoffs between sensitivity and specificity while accounting for population-specific factors through predictive values. By applying the standardized protocols and analytical frameworks outlined herein, researchers can consistently validate genome-scale models to ensure their reliability in guiding scientific discovery and therapeutic development.

From In Silico Predictions to Real-World Applications: Key Methods and Use Cases

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands as a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic phenotypes from genetic information [20] [21]. By combining genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) with an optimality principle, typically biomass maximization for unicellular organisms, FBA enables researchers to simulate the entire set of biochemical reactions in a cell without requiring extensive kinetic parameters [22] [7]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for predicting gene essentiality—identifying genes whose deletion impairs cell survival—and estimating growth capabilities under different nutrient conditions [23] [21]. The fundamental principle underlying FBA is the steady-state mass balance constraint, expressed mathematically as Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v represents the flux vector, coupled with capacity constraints that define upper and lower flux bounds for each reaction [22] [24].

The validation of genome-scale model predictions represents a critical research area, as computational methods increasingly complement experimental approaches in biological discovery, biomedicine, and biotechnology [22]. Due to the cost and complexity of genome-wide deletion screens, computational prediction of gene essentiality has gained significant importance [23]. For metabolic genes, FBA serves as the established gold standard, but its predictive power faces limitations, particularly in higher-order organisms where optimality objectives are unknown or when cells operate at sub-optimal growth states [22] [21]. This comparative guide examines the current landscape of FBA methodologies for phenotype prediction, objectively evaluating their performance against emerging machine learning and data integration approaches.

Method Comparison: Performance Evaluation Across Organisms and Conditions

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Organisms Tested | Reported Accuracy | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FBA | Optimization of biomass objective function [21] | E. coli [22] | ~93.5% for E. coli in glucose [22] | Established benchmark; fast computation [22] | Assumes optimal growth; performance drops in complex organisms [22] |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | Monte Carlo sampling + supervised learning [22] | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, CHO cells [22] | ~95% for E. coli; best-in-class accuracy [22] | No optimality assumption; versatile for multiple phenotypes [22] | Computationally intensive; requires substantial training data [22] |

| ΔFBA | Direct prediction of flux differences using differential expression [20] | E. coli, human muscle [20] | More accurate flux difference prediction [20] | No objective function needed; integrates transcriptomics [20] | Requires paired gene expression data [20] |

| corsoFBA | Protein cost minimization at sub-optimal growth [21] | E. coli central carbon metabolism [21] | Better predicts internal fluxes at sub-optimal growth [21] | Accounts for sub-optimal states; incorporates protein cost [21] | Not ideal for growth rate prediction [21] |

| Mass Flow Graph + ML | Graph analysis of wild-type FBA solutions + classifiers [23] | E. coli [23] | Near state-of-the-art accuracy [23] | Uses wild-type data only; no optimality assumption for mutants [23] | Limited validation across diverse organisms [23] |

| TIObjFind | Integrates MPA with FBA to identify objective functions [24] | C. acetobutylicum, multi-species system [24] | Good match with experimental data [24] | Identifies condition-specific objectives; improves interpretability [24] | Complex implementation; requires experimental flux data [24] |

Case Study: Gene Essentiality Prediction in Escherichia coli

The iML1515 model of E. coli provides a benchmark for evaluating gene essentiality prediction methods. Traditional FBA achieves approximately 93.5% accuracy in predicting metabolic gene essentiality during aerobic growth on glucose [22]. In comparative studies, Flux Cone Learning demonstrated a significant improvement, reaching 95% accuracy on held-out test genes, with particular enhancements in classifying both nonessential (1% improvement) and essential genes (6% improvement) [22]. This performance advantage stems from FCL's ability to learn correlations between flux cone geometry and experimental fitness without presuming deletion strains optimize the same objectives as wild-type cells [22].

Performance in Higher Organisms and Specialized Applications

For the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammalian Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, methods that avoid strict optimality assumptions generally outperform traditional FBA [22]. The reconstruction and application of specialized models, such as the iNX525 model for Streptococcus suis, further demonstrate how FBA can be extended to identify potential drug targets by analyzing genes essential for both growth and virulence factor production [7]. In one study, the iNX525 model predictions aligned with 71.6-79.6% of gene essentiality results from experimental mutant screens [7].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Flux Cone Learning Workflow for Gene Essentiality Prediction

Objective: To predict metabolic gene essentiality using machine learning on flux cone samples without optimality assumptions [22].

Methodology:

- Model Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) with gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations [22].

- Gene Deletion Simulation: For each gene deletion, modify reaction bounds using GPR rules (set ({V}{i}^{\,{\mbox{min}}\,}={V}{i}^{max}=0) for affected reactions) [22].

- Monte Carlo Sampling: Generate multiple random flux samples (typically 100-5000) from the metabolic space of each deletion mutant [22].

- Feature-Label Pairing: Assign experimental fitness scores (labels) to all flux samples from the same deletion mutant [22].

- Model Training: Train a supervised learning algorithm (e.g., random forest) on the flux sample dataset [22].

- Prediction Aggregation: Apply majority voting on sample-wise predictions to generate deletion-wise essentiality calls [22].

Diagram Title: Flux Cone Learning Experimental Workflow

ΔFBA Protocol for Predicting Metabolic Alterations

Objective: To predict metabolic flux differences between conditions (e.g., perturbation vs. control) using differential gene expression data without specifying a cellular objective [20].

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Collect paired transcriptomic data for control and perturbation conditions [20].

- Constraint Setup: Apply the steady-state flux balance constraint to flux differences: SΔv = 0, where Δv = vP - vC [20].

- Consistency Optimization: Formulate and solve a mixed integer linear programming (MILP) problem to maximize consistency between flux changes and differential gene expression [20].

- Flux Difference Prediction: Obtain Δv representing metabolic alterations between conditions [20].

- Validation: Compare predictions against experimental flux measurements or physiological readouts [20].

TIObjFind Framework for Identifying Metabolic Objectives

Objective: To infer context-specific metabolic objective functions from experimental data using topology-informed optimization [24].

Methodology:

- Data Integration: Incorporate experimental flux data and stoichiometric constraints [24].

- Optimization Problem: Minimize difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [24].

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Map FBA solutions onto a graph structure for pathway-based interpretation [24].

- Pathway Extraction: Apply minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to identify critical pathways [24].

- Coefficient Calculation: Compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) to quantify reaction contributions to cellular objectives [24].

Computational Tools and Software Platforms

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [20] [7] | MATLAB-based platform for constraint-based modeling | Implementing FBA and related methods [20] |

| ModelSEED [7] | Automated metabolic model reconstruction | Draft model generation from genome annotations [7] |

| GUROBI Optimizer [7] | Mathematical optimization solver | Solving linear programming problems in FBA [7] |

| MEMOTE [7] | Metabolic model testing suite | Quality assessment of genome-scale models [7] |

| Monte Carlo Samplers [22] | Random sampling of metabolic flux space | Generating training data for Flux Cone Learning [22] |

| Machine Learning Libraries (Scikit-learn, TensorFlow) [22] [11] | Supervised learning algorithms | Training classifiers for phenotype prediction [22] |

Experimental Data Requirements for Method Validation

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: High-quality, manually curated models such as iML1515 for E. coli [22] or organism-specific reconstructions like iNX525 for Streptococcus suis [7] provide the foundational biochemical networks for simulations.

Gene Essentiality Data: Experimental deletion screens using CRISPR-Cas9 or transposon mutagenesis provide essential ground truth data for training and validation [22] [23].

Fluxomic Measurements: (^{13})C metabolic flux analysis and mass spectrometry data enable validation of internal flux predictions [24] [21].

Transcriptomic Profiles: RNA-seq or microarray data for paired conditions facilitate methods like ΔFBA that integrate gene expression [20].

Phenotypic Growth Data: Quantitative fitness measurements under different nutrient conditions or genetic backgrounds serve as key validation metrics [7].

Diagram Title: Resource Ecosystem for Phenotype Prediction

The validation of genome-scale model predictions represents an evolving frontier where traditional optimization-based methods like FBA are increasingly complemented by machine learning and data integration approaches [22] [20]. While FBA remains a valuable tool for predicting gene essentiality and growth phenotypes, particularly in model organisms like E. coli, emerging methods such as Flux Cone Learning and ΔFBA demonstrate measurable improvements in accuracy and versatility [22] [20]. The integration of multiple data types, including transcriptomic profiles and experimental flux measurements, with sophisticated computational frameworks promises to enhance our predictive capabilities across diverse biological systems, from microbial engineering to human disease modeling [20] [24] [7]. As these methods continue to mature, they establish a foundation for more accurate in silico prediction of phenotypic outcomes, ultimately accelerating biological discovery and therapeutic development.

The validation of predictions generated by genome-scale models (GEMs) represents a critical frontier in systems biology. GEMs provide computational predictions of cellular functions by leveraging gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations and constraint-based modeling approaches [16] [25]. However, the accuracy of these models hinges on their ability to recapitulate real biological states, necessitating robust experimental validation frameworks. The integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data has emerged as a powerful strategy for contextualizing GEM predictions, moving beyond individual molecular layers to achieve cell-specific insights. This approach is particularly valuable because mRNA and protein expression data from the same cells under similar conditions often show surprisingly low correlation, with studies reporting Spearman rank coefficients as low as 0.4 [26] [27]. This discrepancy arises from post-transcriptional regulation, varying half-lives of molecules, and other biological factors that complicate direct extrapolation from transcriptome to proteome [26]. This review compares current methodologies for integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data to validate and refine genome-scale model predictions, providing researchers with a structured analysis of experimental approaches, performance metrics, and practical implementation frameworks.

Multi-Omics Integration Methodologies: Comparative Analysis

Computational Mapping and Deep Learning Approaches

scTEL (Transformer-based Deep Learning Framework) The scTEL framework represents a cutting-edge approach that utilizes Transformer encoder layers with LSTM cells to establish a mapping from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data to protein expression in the same cells [28]. This method addresses the high experimental costs of simultaneous transcriptome and proteome measurement techniques like CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing). The model employs a unique processing workflow where unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts are normalized by the total UMI counts in each cell, multiplied by the median of total UMI counts across all cells, and natural logarithm transformation is applied [28]. The final step involves z-score normalization to ensure mean expression of 0 and standard deviation of 1 for each gene. Empirical validation on multiple public datasets demonstrates that scTEL significantly outperforms existing methods like Seurat and totalVI in protein expression prediction, cell type identification, and data integration tasks [28].

Comparison with Alternative Computational Methods Traditional workflows for integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data include Seurat and totalVI (Total Variational Inference). Seurat provides a comprehensive R package for single-cell data analysis offering preprocessing, normalization, clustering, dimensionality reduction, and visualization tools. totalVI employs a unified probabilistic framework based on variational inference and Bayesian methods to model both RNA and protein measurements [28]. However, these methods face limitations in fully correcting for batch effects when consolidating multiple CITE-seq datasets with partially overlapping protein panels. Another deep learning framework, sciPENN, utilizes recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for protein expression prediction but suffers from gradient vanishing issues during training [28]. The performance advantages of scTEL's Transformer architecture highlight how innovative computational approaches are revolutionizing multi-omics integration.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Integration Methods

| Method | Key Algorithm | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scTEL | Transformer Encoder + LSTM | Effective capture of gene interrelationships; superior data integration | Requires substantial computational resources | Significantly outperforms existing methods in protein prediction [28] |

| Seurat | Statistical normalization and clustering | Comprehensive toolkit; user-friendly R implementation | Limited batch effect correction with overlapping protein panels | Popular but outperformed by newer deep learning approaches [28] |

| totalVI | Variational inference + Bayesian methods | Probabilistic framework; handles uncertainty | Distribution assumptions may not match actual data | Reasonable performance but surpassed by transformer models [28] |

| sciPENN | Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) | Multiple task capability | Gradient vanishing issues; suboptimal for expression data | Underperforms compared to transformer architectures [28] |

Constraint-Based Modeling and Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) methods utilize genome-scale models to predict biological capabilities by mathematically representing metabolic reactions through stoichiometric coefficients arranged in matrix form [16]. These approaches impose flux balance constraints ensuring metabolic production equals consumption at steady state, with upper and lower bounds defining allowable reaction fluxes. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) calculates metabolite flow through networks under steady-state assumptions, using linear programming to identify optimal solutions within defined constraints [16] [25].

The conversion of network reconstructions to computational models involves defining exchange reactions that determine nutrient availability and secretion rates. GEMs have evolved substantially since the first model for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999, with current databases containing manually curated GEMs for numerous organisms [25]. For example, the iML1515 model for Escherichia coli contains 1,515 open reading frames and demonstrates 93.4% accuracy for gene essentiality simulation across minimal media with different carbon sources [25]. Similarly, metabolic models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis have enabled understanding of pathogen metabolism under hypoxic conditions and antibiotic pressure [25].

Table 2: Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for Biological Prediction

| Organism | Model Name | Gene Coverage | Prediction Accuracy | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | iML1515 | 1,515 open reading frames | 93.4% gene essentiality simulation accuracy [25] | Metabolic engineering, core metabolism understanding |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yeast 7 | Comprehensive metabolic genes | Thermodynamically feasible flux predictions [25] | Biotechnology, eukaryotic biology |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | iEK1101 | Curated pathogen metabolism | Condition-specific metabolic states [25] | Drug target identification, host-pathogen interaction |

| Neurospora crassa | FARM-reconstructed | 836 metabolic genes | 93% sensitivity/specificity on viability phenotypes [29] | Biochemical genetics, mutant phenotype prediction |

| Bacillus subtilis | iBsu1144 | Re-annotated genome information | Incorporates thermodynamic feasibility [25] | Enzyme and recombinant protein production |

Experimental Integration and Analytical Pipelines

Beyond computational prediction, simultaneous experimental measurement of transcriptomes and proteomes provides critical validation datasets. CITE-seq enables parallel mRNA sequencing and surface protein profiling using antibodies at single-cell resolution [28]. This technique has facilitated important discoveries, including immune cell shifts in COVID-19 severity and macrophage populations that prevent heart damage [28]. However, technical challenges include antibody cross-reactivity, nonspecific binding, and limited antibody availability.

Integrated analytical pipelines have been developed to process joint transcriptomic-proteomic data. One established workflow involves fluorescence-activated cell sorting of specific cell populations followed by RNA sequencing and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for protein identification and quantification [27]. Proteins are typically extracted using modified Folch extraction, reduced with DTT, alkylated with iodoacetamide, digested, and desalted using C18 SPE cartridges before LC-MS/MS analysis [27]. Identification and quantification are performed using software like MaxQuant, with expression values log2-transformed and median-normalized.

These experimental approaches have revealed that approximately 40% of RNA-protein pairs show coherent expression, with cell-specific signature genes involved in characteristic functional processes demonstrating higher correlation between transcript and protein levels [27]. This consistency provides an essential framework for understanding cell-type-specific functions.

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Validation

CITE-seq Protocol for Simultaneous Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling

Sample Preparation and Cell Sorting

- Cell Isolation and Staining: Resuspend single-cell suspensions in PBS containing Fc receptor blocking reagent and antibody-conjugated markers for target surface proteins. Incubate for 30 minutes on ice, protected from light [28].

- Cell Sorting: Isolate specific cell populations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with appropriate gating strategies. For human lung studies, endothelial cells (CD45−/CD326−/CD31+/144+), epithelial cells (CD45−/CD326+/CD31−/CD144−), immune cells (CD45+/CD326−/CD31−/CD144−), and mesenchymal cells (CD45−/CD326−/CD31−/CD144−) have been effectively separated using this approach [27].

- Library Preparation: Follow established CITE-seq protocols for generating barcoded libraries for both mRNA and antibody-derived tags (ADTs). The 10X Genomics platform provides commercial solutions for this process.

Sequencing and Data Processing

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing on compatible platforms. Recommended read depths depend on cell numbers and complexity.

- UMI Normalization: Process raw count data using Scanpy or similar packages. Normalize UMI counts by dividing by total UMI counts per cell, then multiply by the median total UMI counts across all cells: [{v}{ij}=\log \left(\frac{{u}{ij}}{\mathop{\sum }\nolimits{j = 1}^{g}{u}{ij}}\cdot \,\text{median}\,({\bf{U}})+1\right)] where ({\bf{U}}={{{u}{ij}}}{n\times g}) represents the original expression matrix with n cells and g genes [28].

- Z-score Normalization: Apply standardization to ensure mean expression of 0 and standard deviation of 1 for each gene: [{x}{ij}=\frac{{v}{ij}-{\mu }{j}}{{\sigma }{j}}] where ({\mu }{j}=\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits{i = 1}^{n}{v}{ij}) and ({\sigma }{j}=\sqrt{\frac{1}{n-1}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits{i = 1}^{n}{({v}{ij}-{\mu }_{j})}^{2}}) [28].

Integrated Analysis Workflow for Validation of GEM Predictions

Multi-Omics Data Integration

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Identify biological processes and pathways enriched in both transcriptomic and proteomic data. Tools like GOrilla, Enrichr, or clusterProfiler effectively perform this analysis.

- Concordance-Discordance Assessment: Classify gene-protein pairs as coherent (both show similar expression trends) or non-coherent (divergent expression). Approximately 40% of pairs typically show coherence [27].

- Cell-Specific Signature Identification: Apply statistical methods to identify genes and proteins that uniquely define specific cell types. These signatures often show higher RNA-protein correlation and represent essential functional frameworks for each cell type [27].

Validation of GEM Predictions

- Flux Predictions Comparison: Compare transcriptomic and proteomic data with GEM-predicted flux distributions. Discrepancies may indicate post-transcriptional or post-translational regulation not captured in the model.

- Context-Specific Model Extraction: Generate condition-specific models from global GEMs using transcriptomic and proteomic data as constraints. Methods like iMAT, INIT, or mCADRE support this process.

- Gene Essentiality Validation: Compare experimentally determined essential genes from knockout studies with GEM predictions. High-quality models like those for Neurospora crassa achieve 93% sensitivity and specificity [29].

Diagram 1: Multi-omics Integration Workflow for GEM Validation. This workflow illustrates the process of integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data to validate and contextualize genome-scale model predictions, resulting in biologically relevant insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CITE-seq | Simultaneous mRNA and surface protein profiling | Single-cell multi-omics studies | Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing [28] |

| 10X Genomics Single Cell Immune Profiling | Library preparation for single-cell sequencing | Immune cell characterization | Commercially available platform for CITE-seq [28] |

| Scanpy | Python-based single-cell analysis | scRNA-seq and CITE-seq data processing | UMI normalization, clustering, visualization [28] |

| Seurat | R package for single-cell analysis | Multi-omics data integration | Normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering [28] |

| MaxQuant | Mass spectrometry data analysis | Proteomic quantification and identification | Label-free quantification, LFQ algorithm [27] |

| FACSAria II | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | Cell population isolation | High-speed sorting with multi-laser capabilities [27] |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Protein identification and quantification | Proteomic profiling | High sensitivity and specificity for protein detection [27] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based metabolic modeling | GEM simulation and analysis | Flux balance analysis, phenotype prediction [16] |

Applications and Biological Insights

Case Studies in Disease Research

Integrated transcriptomic-proteomic analyses have provided critical insights into human diseases. In pulmonary research, combined analysis of endothelial, epithelial, immune, and mesenchymal cells from normal human infant lung tissue revealed cell-specific biological processes and pathways [27]. Signature genes for each cell type were identified and compared at both mRNA and protein levels, demonstrating that cell-specific signature genes involved in characteristic functional processes showed higher correlation with their protein products. This research led to the development of "LungProteomics," a web application that enables researchers to query protein signatures and compare protein-mRNA expression pairs [27].

In cancer research, CITE-seq has been employed to classify breast cancer cells based on cellular composition and treatment responses, creating a comprehensive transcriptional atlas that elucidates tumor heterogeneity [28]. Similarly, COVID-19 studies utilizing CITE-seq identified significant immune cell shifts between mild and moderate disease states, revealing potential mechanisms of disease progression [28].

Plant Biology and Environmental Stress Response

Integrative omics approaches have illuminated molecular mechanisms underlying plant stress responses. Research on tomato plants exposed to carbon-based nanomaterials (CBNs) under salt stress combined transcriptomic (RNA-Seq) and proteomic (tandem MS) data to identify restoration of expression patterns at both omics levels [30]. This integrated analysis revealed that elevated salt tolerance in CBN-treated plants associated with activation of MAPK and inositol signaling pathways, enhanced ROS clearance, stimulated hormonal and sugar metabolism, and regulation of aquaporins and heat-shock proteins [30]. The study demonstrated complete restoration of 358 proteins and partial restoration of 697 proteins in CNT-exposed seedlings under salt stress, with 86 upregulated and 58 downregulated features showing consistent expression trends at both omics levels [30].

Diagram 2: Plant Stress Tolerance Mechanisms Revealed by Multi-Omics. This diagram shows how integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis revealed the mechanisms by which carbon-based nanomaterials enhance salt stress tolerance in tomato plants through coordinated molecular responses.

The integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data provides an essential framework for validating and contextualizing genome-scale model predictions. While multiple approaches exist—from constraint-based modeling and deep learning to experimental profiling—each offers complementary strengths for extracting cell-specific insights. The relatively low correlation typically observed between mRNA and protein expression (approximately 40% coherence) highlights the biological complexity that models must capture and the critical importance of multi-layer validation [26] [27].

Transformative advances in this field continue to emerge, particularly through deep learning architectures like scTEL that leverage transformer networks, and sophisticated experimental techniques like CITE-seq that enable simultaneous molecular profiling [28]. These approaches, combined with the rigorous mathematical framework of COBRA methods [16] [25] and detailed experimental validation pipelines [27] [29], are progressively enhancing our ability to predict cellular behavior with increasing accuracy. As these methodologies evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate drug development, personalized medicine, and biotechnology applications by providing more reliable, context-specific biological models that faithfully represent the complex interplay between transcriptional and translational regulation in living systems.

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains a major global health threat, causing millions of deaths annually [31] [32]. The extraordinary metabolic flexibility of Mtb is a key factor in its success as a pathogen and its ability to persist in the human host for decades [31] [33]. Understanding Mtb metabolism is therefore crucial for developing new therapeutic strategies. Genome-scale metabolic networks (GSMNs) have emerged as powerful systems biology tools for studying pathogen metabolism as an integrated whole, rather than focusing on individual enzymatic components [31]. These computational models enable researchers to simulate bacterial growth, generate hypotheses, and identify potential drug targets by systematically probing metabolic networks for reactions essential for survival [34] [33]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of available GSMNs for Mtb, evaluates their performance in predicting essential genes and nutrient utilization, and details experimental protocols for model application in drug target identification.

Comparative Analysis of Mtb Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Model Descriptions and Lineage

Multiple GSMNs have been developed for Mtb since the first models were published in 2007 [34]. The models have undergone iterative improvements to expand their scope and accuracy [31] [32]. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the most prominent Mtb metabolic models.

Table 1: Key Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis

| Model Name | Year | Predecessor Models | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSMN-TB [34] | 2007 | Original model | 849 reactions, 739 metabolites, 726 genes; first web-based model; 78% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality |

| iNJ661 [32] | 2007 | Original model | Concurrently developed model with different reconstruction approach |

| iNJ661v [32] | 2011 | iNJ661 | Modified for simulating in vivo growth conditions |

| iOSDD890 [31] | 2014 | iNJ661 | Manual curation based on genome re-annotation; lacks β-oxidation pathways |

| sMtb [32] | 2014 | Integration of multiple models | Combined three previously published models |

| iEK1011 [31] [32] | 2017 | Consolidated model | Uses standardized nomenclature from BiGG database |

| sMtb2018 [31] [32] | 2018 | sMtb | Designed specifically for modeling Mtb metabolism inside macrophages |

The models sMtb2018 and iEK1011 represent the most advanced iterations, with systematic evaluations identifying them as the best-performing models for various simulation approaches [31] [32]. These consolidated models share gene similarities with all other models (>60% to <98.4%), demonstrating their independence from the original iNJ661 and GSMN-TB lineages [32].

Performance Comparison in Predictive Tasks

A systematic evaluation of eight Mtb-H37Rv GSMNs assessed their performance in key predictive tasks including growth analysis, gene essentiality prediction, and nutrient utilization [31] [32]. Table 2 summarizes the comparative performance of the top models across these critical applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Leading Mtb Metabolic Models

| Model | Gene Coverage | Pathway Coverage Strength | Performance in Gene Essentiality Prediction | Performance on Lipid Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iEK1011 | High GPR coverage | Comprehensive, including virulence-associated metabolism | High accuracy | Excellent (includes β-oxidation, cholesterol degradation) |

| sMtb2018 | High GPR coverage | Comprehensive, including virulence-associated metabolism | High accuracy | Excellent (includes β-oxidation, cholesterol degradation) |

| iOSDD890 | Moderate | Strong in nitrogen, propionate, pyrimidine metabolism; weaker in lipid pathways | Moderate | Poor (lacks β-oxidation pathways) |

| iNJ661v_modified | Moderate | Limited lipid metabolism | Moderate | Poor (limited β-oxidation, cholesterol degradation) |

The models sMtb2018 and iEK1011 provide the greatest coverage of gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations and contain genes associated with survival and virulence within the host, such as transport systems, respiratory chain components, fatty acid metabolism, dimycocerosate esters, and mycobactin metabolism [31] [32]. These comprehensive pathway coverage makes them particularly suitable for studying Mtb metabolism during intracellular growth.

Experimental Protocols for Model Application and Validation

Core Workflow for GSMN-Based Drug Target Prediction