Validating Flux Balance Analysis: A Comprehensive Framework for Benchmarking FBA Predictions Against Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists in biomedical and drug development on validating Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions against experimental flux data.

Validating Flux Balance Analysis: A Comprehensive Framework for Benchmarking FBA Predictions Against Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists in biomedical and drug development on validating Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions against experimental flux data. It covers the foundational principles of FBA and the critical importance of validation, explores advanced methodologies and computational frameworks for improving predictive accuracy, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for model refinement, and presents rigorous comparative and validation techniques to assess model performance. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and application of constraint-based metabolic modeling in biotechnological and clinical research.

Foundations of FBA and the Critical Need for Experimental Validation

Core Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling and Flux Balance Analysis

Constraint-based modeling is a powerful computational approach in systems biology that enables the prediction of cellular metabolism without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. At the heart of this methodology lies Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a mathematical framework that models metabolic networks using stoichiometric constraints and optimization principles. FBA operates on the fundamental premise that metabolic systems operate at a steady state, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, ensuring that total input flux equals total output flux for each metabolite within the network [1].

The significance of FBA extends across multiple domains, including drug discovery, microbial strain improvement, systems biology, and disease diagnosis [2]. By leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that incorporate all known metabolic reactions in an organism, researchers can simulate cellular behavior under various conditions, predict the effects of genetic modifications, and identify potential therapeutic targets. The iML1515 model for E. coli, for instance, contains 1,515 open reading frames, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites, representing one of the most comprehensive metabolic reconstructions available [3].

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Framework

Core Assumptions and Constraints

FBA relies on several key assumptions that enable the analysis of large-scale metabolic networks:

Steady-State Assumption: The core principle of FBA is that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, meaning the rate of production equals the rate of consumption for each metabolite [1] [3]. This is represented mathematically as Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector.

Mass Balance Constraints: The model ensures that total input flux equals total output flux for each metabolite, maintaining the conservation of mass within the system [1].

Physiological Flux Bounds: Each reaction flux is constrained by lower and upper bounds (αi ≤ vi ≤ β_i) that represent physiological limits, enzyme capacities, or environmental conditions [1].

Optimality Principle: FBA assumes that metabolic networks evolve toward optimizing specific cellular objectives, such as maximizing biomass production or ATP yield [1].

Mathematical Formulation

The FBA framework can be formally represented through these key components:

Stoichiometric Matrix (S): A mathematical representation of the metabolic network where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent reactions, with elements indicating stoichiometric coefficients [1].

Flux Vector (v): Contains the flux values for each metabolic reaction in the network, representing the rate at which metabolites are converted [1].

Objective Function (Z = c^T v): A linear combination of fluxes that the cell purportedly optimizes, where c is a vector of weights that define the biological objective [1].

The complete FBA optimization problem is formulated as:

This linear programming problem identifies the flux distribution that maximizes the objective function while satisfying all imposed constraints [1].

Methodological Comparisons: Validation Approaches

Validating FBA predictions against experimental data remains a critical challenge in metabolic modeling. Several methodological frameworks have been developed to address this challenge, each with distinct approaches and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of FBA Validation and Enhancement Methodologies

| Method | Core Approach | Key Features | Experimental Data Requirements | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-MFA Validation | Compares FBA predictions against fluxes from 13C isotopic labeling | Statistical validation using χ²-test of goodness-of-fit; quantifies flux uncertainty [4] | 13C-labeled substrate feeding experiments; mass isotopomer distribution (MID) measurements [4] | Gold standard validation; model discrimination; uncertainty quantification [4] |

| TIObjFind Framework | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA | Determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs); uses minimum-cut algorithm; pathway-specific weighting [2] [5] | Experimental flux data; reaction stoichiometry; pathway topology [2] [5] | Identifying context-specific objective functions; analyzing metabolic adaptations [2] |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA | Incorporates enzyme capacity constraints | Adds enzyme availability constraints via kcat values; avoids unrealistic flux predictions [3] | Enzyme kinetics data (kcat values); protein abundance measurements; molecular weights [3] | Improving flux prediction accuracy; modeling engineered strains with modified enzyme activity [3] |

| Topology-Based ML | Machine learning using graph-theoretic features | Uses network topology (betweenness centrality, PageRank) rather than simulation [6] | Curated gene essentiality datasets; reaction network topology [6] | Predicting gene essentiality; identifying critical network nodes [6] |

Workflow Diagrams for Key Methodologies

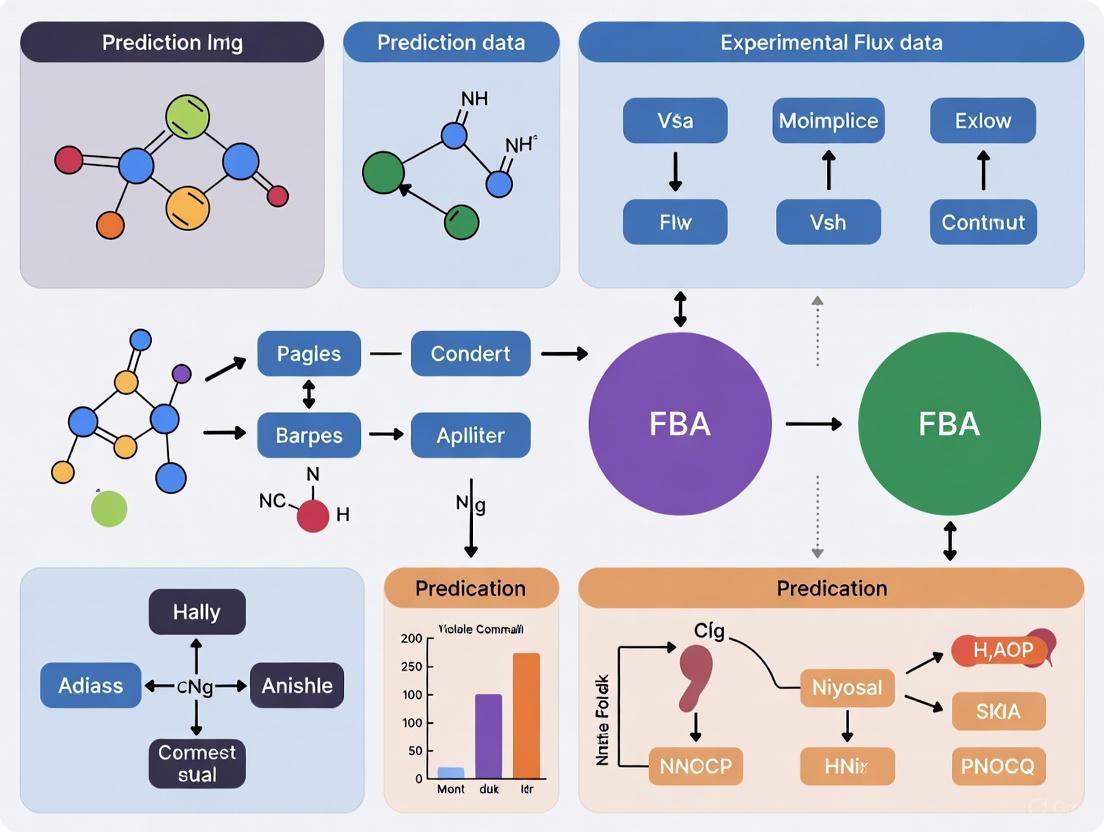

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for FBA Prediction Validation

Figure 2: TIObjFind Framework Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Data Requirements

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) Protocol

13C-MFA serves as the gold standard for validating intracellular metabolic fluxes predicted by FBA. The detailed experimental protocol involves:

Tracer Design: Selection of appropriate 13C-labeled substrates (typically glucose or glutamine) with specific labeling patterns [4].

Isotope Feeding Experiment: Culturing cells under controlled conditions with the 13C-labeled substrate until metabolic and isotopic steady state is achieved [4].

Mass Isotopomer Measurement: Extraction of intracellular metabolites followed by analysis using mass spectrometry or NMR to determine mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) [4].

Flux Estimation: Computational fitting of metabolic flux values that minimize the difference between measured and simulated MIDs using optimization algorithms [4].

Statistical Validation: Application of χ²-test of goodness-of-fit to evaluate model quality and flux uncertainty assessment to determine confidence intervals for estimated fluxes [4].

Parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers have been shown to enhance flux resolution and reduce estimation uncertainty [4].

TIObjFind Implementation Protocol

The TIObjFind framework introduces a novel approach for identifying context-specific objective functions:

Data Integration: Collection of experimental flux data and stoichiometric information from metabolic networks [2] [5].

Optimization Problem Formulation: Setting up a multi-objective optimization that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [2].

Mass Flow Graph Construction: Mapping FBA solutions onto a directed, weighted graph representing metabolic flux distributions [2] [5].

Pathway Analysis: Application of a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) [2].

Objective Function Refinement: Using CoIs as pathway-specific weights to develop improved objective functions that better align with experimental data [2].

The technical implementation typically utilizes MATLAB for core computations, with Python employed for visualization [2].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Validation Metrics

Table 2: Performance Comparison of FBA Methodologies Against Experimental Data

| Validation Method | Accuracy Metric | Performance Result | Reference Organism | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA | Gene Essentiality Prediction | F1-Score: 0.000 (failed to identify essential genes) [6] | E. coli core model | Computational efficiency; genome-scale application [1] [6] |

| Topology-Based ML | Gene Essentiality Prediction | F1-Score: 0.400 (Precision: 0.412, Recall: 0.389) [6] | E. coli core model | Superior to FBA for essentiality prediction; handles biological redundancy [6] |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA | Flux Prediction Accuracy | Improved prediction vs. standard FBA; more realistic flux distributions [3] | E. coli K-12 (iML1515) | Incorporates enzyme limitation; better engineering guidance [3] |

| TIObjFind | Flux Prediction Error | Reduced prediction error vs. single-objective FBA [2] | C. acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii | Captures metabolic adaptation; pathway-specific insight [2] |

Limitations and Challenges

Each validation approach presents distinct limitations that researchers must consider:

13C-MFA: Requires expensive isotopic tracers, complex analytical instrumentation, and specialized computational expertise [4]. The χ²-test has limitations for model selection, particularly with large datasets where small differences may appear statistically significant [4].

TIObjFind: Dependent on availability of experimental flux data, with potential for overfitting to specific conditions [2]. The framework requires pathway definition, which may introduce bias [2].

Enzyme-Constrained FBA: Limited by incomplete enzyme kinetic databases, particularly for transport reactions and secondary metabolism [3]. The assumption of optimal enzyme allocation may not hold in all biological contexts [3].

Standard FBA: Assumes optimal cellular behavior, which may not reflect biological reality, and cannot capture dynamic responses or regulatory effects [1].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FBA Validation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/Databases | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracing metabolic fluxes through specific pathways; validating intracellular fluxes [4] | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories; Sigma-Aldrich | 13C-MFA experiments; flux validation [4] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Structured representation of metabolic network for in silico simulation [3] | BiGG Models; MetaNetX; KEGG [2] | FBA simulation; model reconstruction; gap analysis [3] |

| Enzyme Kinetic Parameters | Constraining flux capacities in enzyme-constrained models [3] | BRENDA; SABIO-RK [3] | ecFBA; understanding enzyme limitations [3] |

| Protein Abundance Data | Determining enzyme concentration constraints [3] | PAXdb; EcoCyc [3] | ecFBA; understanding proteome allocation [3] |

| Flux Analysis Software | Implementing FBA and related algorithms [2] [3] | COBRApy; TIObjFind (MATLAB); ECMpy [2] [3] | Metabolic flux prediction; model validation [2] |

| Experimental Flux Data | Benchmarking and validating computational predictions [2] [4] | Literature curation; parallel labeling experiments [4] | Model validation; objective function identification [2] |

Constraint-based modeling and Flux Balance Analysis provide powerful frameworks for predicting metabolic behavior, but their utility ultimately depends on rigorous validation against experimental data. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that while standard FBA offers computational efficiency for genome-scale predictions, its accuracy can be substantially improved through integration with experimental flux measurements, enzyme constraints, and pathway-aware objective functions.

Emerging methodologies such as TIObjFind represent a shift toward context-aware modeling that captures metabolic adaptations across different environmental conditions [2]. Similarly, the integration of machine learning with topological network analysis demonstrates potential for overcoming limitations of traditional optimization-based approaches, particularly for applications like gene essentiality prediction [6].

Future developments in FBA validation will likely focus on multi-omic integration, dynamic modeling approaches, and improved statistical frameworks for model selection. As constraint-based modeling continues to evolve, robust validation against experimental data will remain paramount for ensuring biological relevance and translational applications in biotechnology and medicine.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has established itself as a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, enabling researchers to predict cellular behavior by optimizing an assumed biological objective, most commonly biomass maximization [7]. This computational approach leverages genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate the complete set of biochemical reactions within a cell, providing invaluable insights for metabolic engineering, drug discovery, and basic biological research [7] [5]. However, the accuracy and biological relevance of FBA predictions frequently suffer from inherent methodological limitations and the fundamental challenge of constraining models with insufficient experimental data [8] [9]. Standalone FBA operates under steady-state assumptions, depends critically on the appropriate selection of an objective function, and often fails to capture the complex regulatory mechanisms that govern cellular metabolism in living systems [5] [9]. This review objectively compares the performance of traditional FBA against emerging methodologies that integrate additional biological data and computational approaches, examining their predictive accuracy through experimental validation and highlighting the critical gaps that remain in metabolic flux prediction.

Fundamental Limitations of Standalone FBA

The Objective Function Problem and Solution Multiplicity

A primary weakness of traditional FBA lies in its reliance on a pre-defined cellular objective function. While biomass maximization proves effective for modeling rapidly growing microbes, this assumption often fails for complex organisms, stressed conditions, or industrial bioprocesses where multiple competing objectives may operate simultaneously [7] [5]. The selection of an inappropriate objective function can dramatically skew flux predictions, leading to biologically unrealistic results [7] [9]. Furthermore, the optimal solution identified by FBA is frequently non-unique; multiple flux distributions can yield the same objective value, creating uncertainty about which pathway the cell actually utilizes [7] [9]. Methods like parsimonious FBA (pFBA) address this by selecting the simplest flux distribution, but this introduces another assumption—that cells minimize protein investment—which may not hold universally [7].

Integration Challenges with Experimental Data

Standalone FBA models typically incorporate limited experimental constraints, primarily focusing on substrate uptake rates. This sparse integration of omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) creates a significant gap between model predictions and biological reality [8]. Without adequate constraints from experimental measurements, FBA solutions may be mathematically optimal but biologically infeasible [9]. The problem is particularly acute for genome-scale models, where the number of reactions far exceeds the number of metabolites, creating an underdetermined system with innumerable possible flux distributions [10]. This fundamental mathematical limitation underscores why additional biological constraints are indispensable for obtaining meaningful predictions.

Comparative Performance: Standalone FBA vs. Next-Generation Methods

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment for Metabolic Gene Essentiality

Gene essentiality prediction provides a critical benchmark for evaluating metabolic modeling methods. The following table compares the performance of traditional FBA against two advanced methodologies using Escherichia coli as a model organism:

| Methodology | Prediction Accuracy | Key Strengths | Reference Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 93.5% | Established gold standard; computationally efficient | E. coli [11] |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | ~95% (Average) | No optimality assumption required; outperforms FBA for essential gene identification | E. coli [11] |

| ΔFBA (deltaFBA) | More accurate than 8 existing FBA methods | Directly predicts flux differences; does not require specifying cellular objective | E. coli, Human [7] |

Flux Cone Learning (FCL), a machine learning framework that identifies correlations between metabolic space geometry and experimental fitness data, demonstrates superior performance by leveraging Monte Carlo sampling and supervised learning without presupposing a cellular objective [11]. Notably, FCL maintains high accuracy even with sparse sampling, with models trained on as few as 10 samples per metabolic state matching traditional FBA performance [11].

Performance in Predicting Metabolic Flux Alterations

Accurately predicting how metabolic fluxes change between conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased, wild-type vs. mutant) presents a distinct challenge. The ΔFBA method addresses this by directly integrating differential gene expression data with GEMs to evaluate flux differences without specifying a cellular objective [7]. Instead, it maximizes consistency between predicted flux alterations and gene expression changes through a constrained mixed integer linear programming (MILP) formulation [7]. In direct comparisons, ΔFBA demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting metabolic alterations caused by genetic and environmental perturbations in Escherichia coli and type-2 diabetes in human muscle compared to eight existing FBA-based methods, including pFBA, GIMME, iMAT, and RELATCH [7].

Community Modeling and Interspecies Interaction Prediction

Predicting metabolic interactions in microbial communities presents particular challenges for standalone FBA. A systematic evaluation of FBA-based tools for predicting microbial interactions found that except for curated GEMs, predicted growth rates and interaction strengths showed no correlation with experimentally measured values from in vitro data [10]. This performance gap highlights the limitations of semi-curated GEMs and the critical importance of model quality. For binary synthetic communities, dynamic approaches like DynamiCom have shown promise in predicting both cross-fed metabolites and the evolution of interspecies interactions over time, capabilities lacking in steady-state community FBA methods [12].

Methodological Approaches: From Standalone FBA to Integrated Frameworks

Workflow Comparison: Traditional vs. Next-Generation Methods

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences in methodology between traditional FBA and two advanced approaches:

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

ΔFBA Validation Protocol

- Data Input Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) and differential gene expression data between two conditions (e.g., perturbation vs. control) [7].

- Flux Balance Constraints: Apply steady-state mass balance constraints to the flux difference vector: SΔv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and Δv represents flux differences [7].

- MILP Formulation: Implement the mixed integer linear programming problem to maximize consistency (and minimize inconsistency) between flux differences and gene expression changes using binary variables zU and zD to represent up- and down-regulation [7].

- Flux Prediction: Solve the optimization problem to obtain quantitative predictions of flux differences between conditions [7].

- Validation: Compare predicted flux differences against experimental fluxomic data (e.g., from 13C-MFA) or growth phenotype data from deletion studies [7].

Flux Cone Learning Protocol

- Model Preparation: Obtain a curated GEM for the target organism [11].

- Monte Carlo Sampling: Generate multiple random flux samples (typically 100-5000) for each gene deletion variant by zeroing out reaction bounds according to gene-protein-reaction associations [11].

- Feature Matrix Construction: Create a training dataset where each row represents a flux sample and columns represent reaction fluxes, labeled with experimental fitness measurements [11].

- Model Training: Train a supervised learning algorithm (e.g., random forest classifier) to predict phenotypic outcomes from flux distributions [11].

- Prediction and Aggregation: Generate sample-wise predictions for new gene deletions and aggregate results using majority voting to produce deletion-wise predictions [11].

TIObjFind Protocol for Objective Function Identification

- Data Collection: Acquire experimental flux data for the organism under specific conditions [5].

- Optimization Problem Setup: Formulate an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [5].

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Map FBA solutions onto a flux-dependent weighted reaction graph [5].

- Pathway Analysis: Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) [5].

- Validation: Assess whether the identified objective function improves prediction accuracy across multiple conditions [5].

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Metabolic Flux Research |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Platforms | COBRA Toolbox [7] | MATLAB suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| KBase [13] | Web-based platform for comparative FBA solutions analysis | |

| MEMOTE [9] | Test suite for metabolic model quality assurance | |

| COMETS [10] | Tool for dynamic FBA simulations in spatial environments | |

| Databases & Models | BiGG Models [9] | Repository of curated genome-scale metabolic models |

| AGORA [10] | Resource of semi-refined metabolic reconstructions for gut bacteria | |

| Analytical Methods | 13C-MFA [9] | Experimental method for flux quantification using isotopic labeling |

| Flux Variability Analysis [9] | Computational method to characterize flux solution spaces | |

| Random Sampling [9] | Technique for exploring possible flux distributions |

The critical gap between standalone FBA predictions and experimental flux data stems from fundamental methodological limitations, particularly the reliance on assumed cellular objectives and insufficient integration of biological constraints. As the quantitative comparisons demonstrate, next-generation methods like ΔFBA, Flux Cone Learning, and objective function identification frameworks consistently outperform traditional FBA across multiple validation metrics, including gene essentiality prediction and metabolic alteration assessment [7] [11] [5]. However, significant challenges remain in model curation, community simulation, and incorporating multi-omics data. The future of metabolic flux prediction lies in hybrid approaches that combine mechanistic modeling with data-driven machine learning, leverage high-quality experimental flux data for validation, and develop flexible frameworks that adapt to context-specific cellular objectives without relying on rigid optimization assumptions. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to enhance the predictive power of metabolic models, ultimately accelerating progress in biotechnology, drug development, and fundamental biological research.

Constraint-based metabolic modeling has become an indispensable tool for quantifying cellular phenotypes in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research. Among these techniques, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands out for its ability to predict metabolic fluxes at a genome-scale using optimization principles. However, the reliability of FBA predictions fundamentally depends on the objective functions and constraints used in simulations, which often embody unverified assumptions about cellular optimization behavior [4] [14]. This validation challenge has established 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) as the gold standard for experimental validation, providing a critical benchmark against which FBA predictions can be tested and refined [15] [14].

13C-MFA provides direct empirical constraints on intracellular fluxes by tracing the fate of 13C-labeled atoms through metabolic pathways. Unlike FBA, which predicts fluxes based on hypothesized cellular objectives, 13C-MFA works backward from measured isotopic labeling patterns to infer the metabolic fluxes that must have created them [4] [16]. This fundamental difference positions 13C-MFA as an authoritative reference for validating constraint-based models. The fit between 13C-MFA data and model predictions provides a quantitative measure of validation that is otherwise absent from pure FBA simulations [14]. As the field advances toward genome-scale 13C-MFA (GS-MFA), the potential for comprehensive model validation continues to expand, enabling more reliable predictions for metabolic engineering and drug development [17] [18].

Comparative Analysis: 13C-MFA versus FBA as Validation Tools

Fundamental Methodological Differences

The core distinction between 13C-MFA and FBA lies in their approach to flux determination. 13C-MFA is a deductive, data-driven methodology that infers fluxes from experimental measurements of isotopic labeling, typically using mass spectrometry or NMR [16]. In contrast, FBA is a predictive, hypothesis-driven approach that uses linear programming to identify flux distributions that optimize an assumed cellular objective, such as biomass maximization [4] [14]. This fundamental difference manifests in their respective strengths and limitations for flux validation.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of 13C-MFA and FBA

| Aspect | 13C-MFA | FBA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary basis | Experimental measurement of 13C labeling patterns | Optimization of assumed cellular objective function |

| Network scope | Traditionally core metabolism; expanding to genome-scale | Genome-scale from inception |

| Key inputs | Isotopic tracer, mass isotopomer distributions, extracellular fluxes | Stoichiometric matrix, exchange constraints, objective function |

| Key outputs | Estimated fluxes with confidence intervals | Predicted flux distributions |

| Validation approach | Goodness-of-fit tests (e.g., χ²-test) to labeling data | Comparison with experimental data (e.g., 13C-MFA, growth rates) |

| Uncertainty quantification | Statistical confidence intervals for fluxes | Flux variability analysis |

| Computational demand | High (non-linear fitting) | Low to moderate (linear programming) |

Quantitative Validation Performance

When deployed as a validation tool, 13C-MFA provides quantitative metrics that assess the biological realism of FBA predictions. Studies that have directly compared FBA predictions against 13C-MFA fluxes consistently reveal significant discrepancies, particularly for engineered strains where evolutionary optimization assumptions may not apply [14]. For example, in E. coli, FBA predictions based on biomass maximization often fail to accurately capture the split ratios at key branch points like the pentose phosphate pathway and TCA cycle, which are precisely quantified by 13C-MFA [18] [14].

The statistical rigor of 13C-MFA stems from its ability to provide goodness-of-fit measures and flux confidence intervals, enabling researchers to distinguish between biologically relevant and erroneous FBA solutions [4] [16]. This quantitative validation is particularly valuable for testing alternative objective functions in FBA, as 13C-MFA fluxes can identify which cellular optimization principles (if any) best align with experimental observations across different growth conditions and genetic backgrounds [4] [16].

Experimental Protocols: 13C-MFA Workflow and Validation Standards

Core Experimental Workflow

Implementing 13C-MFA as a validation benchmark requires strict adherence to established experimental and computational protocols. The complete workflow encompasses everything from tracer design to statistical validation, with each step critically influencing the reliability of the resulting flux estimates [16].

Figure 1: The 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow for Generating Validation-Quality Flux Data

Minimum Information Standards for Reproducibility

To ensure that 13C-MFA studies provide reliable validation benchmarks, the field has established minimum information standards that should be reported in any publication. These standards address common shortcomings in reproducibility and enable critical evaluation of flux estimates [16].

Table 2: Minimum Reporting Standards for 13C-MFA Validation Studies

| Category | Essential Information | Validation Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment Description | Cell source, culture conditions, tracer composition, sampling times | Enables experimental replication and assessment of physiological relevance |

| Metabolic Network Model | Complete reaction list, atom transitions, balanced metabolites | Allows evaluation of model completeness and potential network gaps |

| External Flux Data | Growth rates, substrate consumption, product formation rates | Provides basis for flux normalization and constraint validation |

| Isotopic Labeling Data | Raw mass isotopomer distributions, standard deviations | Enables statistical validation of fitting procedures and uncertainty analysis |

| Flux Estimation | Software used, fitting algorithm, optimization criteria | Permits evaluation of computational approaches and potential biases |

| Goodness-of-Fit | χ²-values, residuals analysis, confidence intervals | Quantifies statistical reliability of flux estimates for validation use |

Adherence to these standards is particularly crucial when 13C-MFA fluxes are used to validate FBA predictions, as omissions in any category can compromise the validation effort. Notably, one review found that only about 30% of published 13C-MFA studies provided sufficient information to be considered acceptable, highlighting the need for greater rigor in the field [16].

Technical Implementation: From Data to Validation Insights

Successfully implementing 13C-MFA as a validation benchmark requires specific experimental and computational resources. The table below summarizes key solutions and their functions in generating high-quality flux data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 13C-MFA

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in 13C-MFA Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine, 13C-labeled substrates | Create distinct labeling patterns that trace metabolic pathway activities |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR systems | Quantify mass isotopomer distributions in metabolic intermediates |

| Metabolic Network Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, MetRxn, BiGG Models | Provide atom mapping information and reaction stoichiometries |

| Flux Analysis Software | Iso2Flux, INCA, OpenFLUX, 13CFLUX2 | Perform flux estimation, statistical analysis, and confidence interval calculation |

| Stoichiometric Models | COBRA Toolbox, cobrapy, MEMOTE | Enable FBA simulations and comparison with 13C-MFA flux benchmarks |

Advanced Model Selection and Validation Frameworks

Beyond traditional goodness-of-fit tests, advanced statistical frameworks are emerging to enhance the validation power of 13C-MFA. These approaches address known limitations of conventional methods, particularly the χ²-test's sensitivity to error model misspecification [15].

The validation-based model selection approach utilizes independent labeling experiments to select models based on their predictive performance for new data, rather than solely on goodness-of-fit to a single dataset [15]. This method demonstrates greater robustness to uncertainties in measurement errors and protects against both overfitting and underfitting. In studies where the true model structure was known, validation-based selection consistently identified the correct model, whereas χ²-test-based approaches selected different model structures depending on assumed measurement uncertainty [15].

Similarly, Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) has emerged as a powerful alternative that explicitly accounts for model uncertainty in flux estimation [19]. By weighting flux estimates from multiple competing models according to their statistical support, BMA provides more robust flux inferences that are less vulnerable to incorrect model selection. This approach resembles a "tempered Ockham's razor," automatically balancing model complexity against explanatory power without requiring arbitrary significance thresholds [19].

Figure 2: Advanced Statistical Frameworks for 13C-MFA Model Selection and Validation

13C-MFA establishes an essential empirical foundation for validating predictive metabolic models like FBA. By providing direct, quantitative measurements of intracellular fluxes, 13C-MFA moves metabolic modeling beyond purely theoretical predictions into the realm of empirically grounded systems biology. The statistical rigor of 13C-MFA—through goodness-of-fit tests, confidence interval estimation, and advanced model selection approaches—creates a robust benchmark against which FBA predictions can be evaluated and refined [4] [15].

As the field progresses toward genome-scale 13C-MFA and more sophisticated validation frameworks, the synergy between experimental flux measurement and computational prediction will continue to strengthen. This partnership is particularly valuable for drug development and metabolic engineering applications, where reliable flux predictions can guide intervention strategies and optimize bioproduction strains [17] [19]. By maintaining high standards of experimental execution and data reporting, and by adopting robust validation practices, researchers can enhance confidence in constraint-based modeling and accelerate progress in understanding and engineering cellular metabolism.

Advanced Methodologies for Enhancing FBA Predictive Power

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has served as a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling for decades, enabling researchers to predict cellular phenotypes from genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) by leveraging physicochemical constraints and optimization principles [20] [21]. However, traditional FBA faces significant limitations in predictive accuracy, particularly when dealing with complex biological systems where optimality assumptions break down or when quantitative predictions of metabolic fluxes under varying conditions are required [22] [23]. The emergence of hybrid modeling approaches, which integrate mechanistic FBA frameworks with machine learning (ML) techniques, represents a paradigm shift in metabolic systems biology, offering enhanced predictive power while maintaining biochemical fidelity [20] [24].

This integration addresses a fundamental challenge in biological modeling: mechanistic models provide interpretability but struggle with complexity, while ML models offer predictive capacity but require large training datasets and operate as "black boxes" [20]. Hybrid approaches leverage the strengths of both, creating systems that obey biological constraints while learning patterns from experimental data [21] [24]. Within the broader context of FBA prediction validation against experimental flux data, hybrid modeling provides a framework for systematically improving model accuracy through data integration, moving beyond traditional FBA's limitations in capturing the full complexity of cellular metabolism [2] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Hybrid FBA Approaches

Methodological Spectrum of Hybrid FBA Frameworks

Table 1: Comparison of Major Hybrid FBA Modeling Approaches

| Approach | Core Methodology | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Validation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid (AMN) | Embeds FBA within artificial neural networks with custom loss functions [20] | Medium (small training sets sufficient) [20] | Systematic outperformance of FBA; requires smaller training sets [20] | Improved growth rate predictions in E. coli and P. putida across media [20] |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | Monte Carlo sampling of metabolic space + supervised learning [11] | Large (requires extensive sampling) [11] | Best-in-class essentiality prediction; no optimality assumption [11] | 95% accuracy vs. 93.5% for FBA in E. coli gene essentiality [11] |

| NEXT-FBA | Hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven framework [25] | Not specified | Open access; improved intracellular flux predictions [25] | Not specified in available abstract [25] |

| Topology-Informed ML | Graph-theoretic features + Random Forest classifier [23] | Medium (network topology + essentiality data) [23] | Overcomes FBA redundancy limitation; structure-first approach [23] | F1-score: 0.400 vs. 0.000 for FBA in E. coli core network [23] |

| SBML-Compliant Hybrid | Merges mechanistic models with DNNs under SBML standard [24] | Variable (depends on model complexity) | Facilitates widespread use; compatible with existing model databases [24] | Validated on E. coli threonine synthesis, signal transduction, yeast glycolysis [24] |

Performance Benchmarking Against Experimental Data

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Organisms and Tasks

| Organism | Prediction Task | Traditional FBA Performance | Hybrid Model Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Gene essentiality (multiple carbon sources) [11] | 93.5% accuracy [11] | 95% accuracy (FCL) [11] | Curated essential gene datasets [11] |

| E. coli core metabolism | Gene essentiality [23] | F1-score: 0.000 (failed to identify essentials) [23] | F1-score: 0.400 (Precision: 0.412, Recall: 0.389) [23] | PEC database cross-referenced with computational studies [23] |

| S. cerevisiae | Gene essentiality [11] | Lower than E. coli (organism complexity) [11] | Outperformed FBA (specific metrics not provided) [11] | Experimental fitness scores from deletion screens [11] |

| CHO cells | Bioprocess characterization [22] | Informative value varies with data partition [22] | Higher accuracy across all data partitions [22] | 33 experiments in fractional factorial design space [22] |

| P. putida | Growth rate in different media [20] | Standard FBA limitations [20] | Systematic outperformance of FBA [20] | Experimental growth rate measurements [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid Model Development

The Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) approach represents a foundational methodology for integrating FBA directly within machine learning architectures [20]. The protocol involves these critical steps:

- Model Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format and convert it to a suitable computational framework (e.g., COBRApy) [20] [26].

- Solver Replacement: Replace the standard Simplex solver with gradient-friendly alternatives (Wt-solver, LP-solver, or QP-solver) to enable backpropagation through the FBA solution process [20].

- Neural Layer Design: Implement a trainable neural network layer that processes input conditions (medium composition or gene knockout status) to predict uptake flux bounds [20].

- Hybrid Architecture Construction: Connect the neural layer to the modified FBA solver, creating an end-to-end differentiable architecture [20] [24].

- Model Training: Train the hybrid model using reference flux distributions (either FBA-generated or experimental) with loss functions that incorporate both prediction error and constraint satisfaction [20].

Diagram 1: AMN hybrid model architecture showing the integration of neural networks with mechanistic FBA solvers [20].

Flux Cone Learning Implementation

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) provides an alternative approach that leverages the geometry of metabolic space rather than embedding FBA within neural networks [11]:

- Metabolic Space Sampling: Use Monte Carlo sampling to generate numerous flux distributions for each gene deletion variant of the GEM, creating a comprehensive representation of the metabolic space [11].

- Feature-Label Pairing: Assign experimental fitness scores (e.g., from deletion screens) as labels to all flux samples from the corresponding deletion mutant [11].

- Model Training: Train supervised learning models (random forests perform well) on the sampled flux distributions to predict phenotypic outcomes from flux patterns [11].

- Prediction Aggregation: Apply majority voting across all samples from a deletion cone to generate deletion-wise predictions [11].

Diagram 2: Flux Cone Learning workflow demonstrating how Monte Carlo sampling enables phenotype prediction [11].

Multi-Omic Data Integration Protocol

For systems with available transcriptomic and fluxomic data, a comprehensive hybrid protocol enables condition-specific metabolic modeling [27]:

- Data Preprocessing: Convert transcriptomic data (RPKM) to fold changes relative to control conditions and prepare the GEM for constraint-based analysis [27].

- Regularized FBA: Perform flux balance analysis with regularization terms, using different biological objective functions (e.g., biomass-ATP maintenance, biomass-photosystem I/II) [27].

- Multi-Omic Dataset Creation: Concatenate transcript fold changes with computed flux distributions to create integrated datasets [27].

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, LASSO regression) to identify key transcript-flux relationships [27].

- Pattern Recognition: Implement clustering algorithms (k-means) to group conditions with similar metabolic-regulatory profiles [27].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Hybrid FBA Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Modeling Platforms | COBRApy [26], Cobrapy [20] | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks | FBA simulation, model manipulation [20] [26] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn [23], TensorFlow/PyTorch [20] | Implementation of neural networks and classical ML algorithms | Random forest classifiers, neural network layers [20] [23] |

| Model Repositories | BioModels [24], JWS Online [24] | Source of curated SBML models for various organisms | Access to validated mechanistic models [24] |

| Network Analysis Tools | NetworkX [23] | Graph theory and network analysis | Calculation of topological features for metabolism [23] |

| Hybrid Modeling Specialized Tools | SBML2HYB [24] | Conversion between SBML and hybrid model formats | Creating SBML-compliant hybrid models [24] |

| Sampling Algorithms | Monte Carlo samplers (e.g., optGpSampler) [11] | Exploration of metabolic flux space | Flux Cone Learning feature generation [11] |

| Experimental Validation Databases | PEC database [23], deletion screen datasets [11] | Ground truth for model training and validation | Essential gene identification [11] [23] |

Validation Frameworks and Performance Interpretation

Validation Metrics and Benchmarking Strategies

The validation of hybrid FBA models requires careful consideration of multiple performance dimensions beyond simple accuracy metrics. For essentiality prediction, metrics should include precision, recall, and F1-scores to account for class imbalance between essential and non-essential genes [11] [23]. For quantitative flux predictions, correlation coefficients with experimental flux measurements, mean squared error, and significance testing against null models provide comprehensive validation [2].

Cross-validation strategies must account for the hierarchical structure of metabolic data, where multiple flux samples may originate from the same gene deletion [11]. Leave-one-deletion-out cross-validation or stratified sampling that maintains deletion-wise integrity prevents overoptimistic performance estimates. Additionally, validation across multiple organisms with varying metabolic network complexity (from E. coli core to CHO cells) tests the generalizability of hybrid approaches [22] [11].

Interpretation of Model Performance Disparities

The significant performance advantages of hybrid models over traditional FBA stem from their ability to address fundamental limitations of pure optimization-based approaches [20] [11] [23]. FBA's poor performance in identifying essential genes, particularly in networks with redundancy, arises from its assumption that cells can instantly reroute flux through alternative pathways [23]. Hybrid models overcome this by learning from experimental data which topological positions (graph centrality metrics) or flux patterns actually correlate with essentiality, regardless of theoretical rerouting potential [11] [23].

For quantitative phenotype predictions, traditional FBA requires accurate specification of uptake flux bounds, which rarely derive from simple conversion of extracellular concentrations [20]. Hybrid models address this through neural network layers that learn the complex mapping between medium composition and effective flux constraints from experimental data [20]. This explains the systematic outperformance of hybrid models across different media conditions and genetic backgrounds.

Hybrid modeling approaches that integrate machine learning with mechanistic FBA frameworks represent a significant advancement in metabolic systems biology, consistently outperforming traditional FBA across multiple prediction tasks and organisms. The neural-mechanistic AMN architecture, Flux Cone Learning, topology-based ML, and SBML-compliant hybrid models each offer distinct advantages depending on the available data and prediction goals [20] [11] [24].

These approaches demonstrate that combining the interpretability and constraint satisfaction of mechanistic models with the pattern recognition capabilities of machine learning creates synergistic effects, enabling more accurate predictions while maintaining biological plausibility. As the field progresses, standardization of hybrid model formats [24] and sharing of trained models through public repositories will accelerate adoption across basic research and drug development applications.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the emerging toolkit of hybrid FBA methods provides powerful alternatives when traditional FBA fails to capture biological complexity, particularly for higher organisms where optimality assumptions break down or when predicting non-growth-related phenotypes. The continued validation of these approaches against experimental flux data will further refine their capabilities and expand their application domains in both academic and industrial settings.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has long been a cornerstone of metabolic modeling, providing a computational framework to predict how metabolic fluxes are distributed throughout a cellular network. Traditional FBA relies heavily on the assumption that cells optimize for a single objective, most commonly biomass maximization, which simulates maximized growth. While this paradigm has proven useful, especially for microbial systems in controlled environments, it often fails to capture the complex metabolic behaviors observed in diverse biological contexts, including mammalian cells, diseased tissues, and engineered bioproduction systems. This limitation has spurred the development of sophisticated methods that move beyond a single, fixed objective. This guide compares these advanced approaches, evaluating their performance against experimental flux data and providing a roadmap for researchers seeking to apply them in drug development and metabolic engineering.

Method Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core features, validation data, and primary applications of key methods that optimize or bypass the need for a pre-defined objective function.

| Method Name | Core Approach | Optimization Strategy | Key Experimental Validation | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEXT-FBA [8] [25] | Hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven; uses ANN trained on exometabolomic data. | Derives intracellular flux bounds from exometabolomic data via pre-trained models. | 13C-labeled intracellular fluxomic data in CHO cells. [8] | Outperforms existing methods in predicting intracellular fluxes aligned with experimental data. [8] |

| TIObjFind [5] | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA. | Infers pathway-specific "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) for objective functions from data. | Experimental flux data from Clostridium acetobutylicum and a multi-species system. [5] | Reduces prediction error and improves alignment with experimental data. [5] |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [11] | Machine learning-based; uses Monte Carlo sampling of the metabolic flux cone. | Learns correlations between flux cone geometry and phenotypes from deletion screen fitness data. | Gene essentiality screens in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and CHO cells. [11] | 95% accuracy for E. coli essentiality, outperforming FBA; versatile for other phenotypes. [11] |

| ΔFBA [7] | Leverages differential gene expression between two conditions. | Maximizes consistency/minimizes inconsistency between flux alterations and gene expression changes. | Environmental/genetic perturbations in E. coli; T2D in human muscle. [7] | More accurate prediction of flux differences compared to other FBA methods. [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

NEXT-FBA: A Hybrid Modeling Protocol

NEXT-FBA (Neural-net EXtracellular Trained Flux Balance Analysis) addresses the challenge of limited intracellular data by leveraging more readily available exometabolomic data [8].

Core Workflow:

- Data Collection: Gather exometabolomic data (extracellular metabolite measurements) and paired 13C-based intracellular fluxomic data from cultures, for example, of Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells [8].

- ANN Training: Train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to learn the underlying relationships between the exometabolomic profiles and the intracellular flux distributions [8].

- Bound Prediction: Use the trained ANN model, in conjunction with new exometabolomic data, to predict upper and lower bounds for intracellular reaction fluxes within a Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) [8].

- Flux Prediction: Perform FBA using the newly derived, biologically relevant constraints to obtain a context-specific intracellular flux prediction [8].

NEXT-FBA integrates machine learning with constraint-based modeling.

Flux Cone Learning for Phenotype Prediction

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) abandons the optimality assumption altogether, instead using the shape of the metabolic solution space to predict deletion phenotypes [11].

Core Workflow:

- Define Deletion Cones: For each gene deletion in a GEM, zero out the flux bounds of associated reactions using the Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) map. This defines a new "flux cone" for the mutant [11].

- Monte Carlo Sampling: Use a Monte Carlo sampler to generate a large number of random, feasible flux distributions (samples) from the flux cone of each gene deletion and the wild-type model [11].

- Model Training: Construct a feature matrix where each row is a flux sample and each column is a reaction flux. Train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., a random forest classifier) using these samples, with labels from experimental fitness data (e.g., essential vs. non-essential) [11].

- Prediction & Aggregation: For a new gene deletion, sample its flux cone and use the trained model to make a sample-wise prediction. Aggregate these predictions (e.g., by majority voting) to produce a final, deletion-wise phenotypic prediction [11].

FCL uses machine learning on flux distributions to predict phenotypes.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following table compiles key quantitative results from validation studies, providing a direct comparison of predictive accuracy against experimental data.

| Method | Validation Context | Benchmark (vs. FBA) | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [11] | Gene essentiality prediction in E. coli. | FBA (93.5% accuracy). | 95% accuracy; 1% and 6% improvement for non-essential and essential genes, respectively. |

| NEXT-FBA [8] | Intracellular flux prediction in CHO cells. | Unspecified existing methods. | Outperforms existing methods in predicting fluxes that align closely with experimental 13C-fluxomic data. |

| ΔFBA [7] | Predicting flux differences in E. coli under perturbation. | REMI, pFBA, iMAT, etc. (8 methods). | More accurate prediction of flux differences compared to all other tested methods. |

| TIObjFind [5] | Predicting flux in C. acetobutylicum. | Standard FBA objective. | Reduces prediction error and improves alignment with experimental flux data. |

Successfully implementing these advanced FBA techniques requires a suite of computational and data resources.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | A stoichiometric matrix of all known metabolic reactions in an organism. | The iML1515 model for E. coli is used as a base for constraint-based simulations [3]. |

| COBRA Toolbox / cobrapy | Software suites for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. | Used to implement FBA, FVA, and other algorithms; essential for running simulations [9]. |

| Exometabolomic Data | Measurements of extracellular metabolite uptake and secretion rates. | Used in NEXT-FBA to train models for predicting intracellular flux bounds [8]. |

| 13C-Fluxomic Data | Intracellular metabolic fluxes estimated from 13C-labeling experiments. | Serves as the "ground truth" for training and validating methods like NEXT-FBA [8] [9]. |

| Differential Gene Expression Data | Transcriptomic data comparing two biological conditions (e.g., disease vs. healthy). | Integrated by ΔFBA to directly predict changes in metabolic fluxes between conditions [7]. |

| Gene Deletion Fitness Data | Experimental data on cell growth or viability after gene knockout. | Used as training labels for supervised learning in Flux Cone Learning [11]. |

The field of metabolic modeling is rapidly evolving beyond the simplistic assumption of biomass maximization. Methods like NEXT-FBA, TIObjFind, Flux Cone Learning, and ΔFBA represent a paradigm shift towards data-driven, context-aware objective function optimization. As the benchmarks show, these approaches can achieve superior agreement with experimental flux data by leveraging different types of omics data and sophisticated computational frameworks. For researchers in drug development and metabolic engineering, selecting the right method depends on the specific biological question and the available data. When direct intracellular flux data is scarce, NEXT-FBA offers a powerful alternative by using exometabolomics. For predicting the phenotypic outcomes of genetic perturbations without an optimality assumption, Flux Cone Learning is a best-in-class choice. For analyzing metabolic rewiring between two states, such as diseased versus healthy tissue, ΔFBA provides a robust solution. By adopting these advanced tools, scientists can build more predictive models of cellular metabolism, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and the design of efficient cell factories.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, enabling researchers to predict metabolic flux distributions by optimizing a specified cellular objective [5] [2]. However, its predictive accuracy heavily depends on selecting an appropriate objective function, which may shift under different physiological or environmental conditions [5] [2]. Traditional FBA implementations often assume static objectives—typically biomass maximization or metabolite production—which can fail to capture the dynamic reprogramming of metabolic networks observed in experimental data [5] [9]. This fundamental limitation has driven the development of more sophisticated frameworks that can infer context-specific objective functions directly from experimental measurements.

The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework represents a significant methodological advancement by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically identify metabolic objectives that align with experimental flux data [5] [2]. Through its novel implementation of Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), TIObjFind quantifies each metabolic reaction's contribution to an inferred cellular objective, thereby providing a data-driven approach to objective function selection [5]. This framework not only enhances the biological interpretability of complex metabolic networks but also addresses the critical validation gap between FBA predictions and experimental flux measurements [9]. By examining adaptive shifts in cellular responses across different biological stages, TIObjFind offers researchers a powerful tool for uncovering context-dependent metabolic priorities in both natural and engineered biological systems.

Understanding TIObjFind's Methodology and Workflow

Core Theoretical Foundations

TIObjFind builds upon the established ObjFind framework, which introduced Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) as weighting factors that quantify each metabolic flux's additive contribution to a chosen objective function [2]. However, where ObjFind assigned weights across all metabolites with potential overfitting concerns, TIObjFind introduces a topology-informed approach that focuses on specific pathways rather than the entire network [5] [2]. This strategic refinement enhances both interpretability and adaptability by leveraging the inherent organization of metabolic networks.

The framework operates on several key theoretical principles. First, it recognizes that cellular objectives often manifest as weighted combinations of fluxes rather than the optimization of a single reaction [5]. Second, it incorporates the concept that metabolic networks exhibit modular organization, where certain pathways collectively serve specific physiological functions. Third, it acknowledges that environmental perturbations trigger adaptive responses that alter flux priorities throughout the network [5] [2]. By formalizing these principles into a mathematical framework, TIObjFind provides a systematic approach for inferring cellular objectives from experimental data while respecting biochemical constraints and network topology.

Three-Step Technical Workflow

The TIObjFind framework implements a structured computational workflow consisting of three integrated phases, each building upon the previous to progressively refine objective function identification. The table below summarizes the key components and outputs of each step.

Table: The Three-Step TIObjFind Workflow

| Step | Primary Action | Key Components | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Optimization Problem Reformulation | Single-level KKT formulation; Thermodynamic, mass balance, and uptake constraints; Dual variables (uᵢ, g) [28] [29] | Best-fit FBA solutions aligned with experimental data |

| Step 2 | Mass Flow Graph Construction | Mapping of FBA solutions to graph structure; Dual network transformation; Self-loops for autocatalytic reactions [28] [29] | Flux-dependent weighted reaction graph (Mass Flow Graph) |

| Step 3 | Pathway Importance Quantification | Minimum-cut algorithm application; Edge weight normalization; Pathway flux distribution analysis [5] [28] | Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions |

Visualization of the TIObjFind computational workflow, illustrating the three-stage process from experimental data to validated objective function.

Technical Implementation Details

The TIObjFind framework was implemented in MATLAB, utilizing custom code for the primary analysis with minimum cut set calculations performed using MATLAB's maxflow package [5] [2]. The implementation employs the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for solving minimum-cut problems, selected for its computational efficiency and near-linear performance across varying graph sizes [5] [2]. For visualization of results, the framework incorporates Python with the pySankey package, enabling intuitive representation of complex flux distributions and pathway relationships [5] [2].

A critical innovation in TIObjFind is its application of duality theory from linear programming. In the dual formulation, primal reactions become metabolites while primal metabolites serve as constraints, creating a transformed network that reveals sensitivity relationships [28] [29]. The mass flow graph constructed in Step 2 represents reaction fluxes as edge weights, with self-loops capturing autocatalytic reactions where products also serve as reactants [28]. This mathematical reformulation enables the framework to move beyond simple flux prediction to uncover the fundamental organizational principles governing metabolic responses to environmental changes.

Comparative Analysis: TIObjFind vs. Alternative FBA Approaches

Methodological Comparison

The landscape of FBA-based methodologies encompasses diverse approaches for predicting metabolic flux distributions, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation strategies. The table below provides a systematic comparison of TIObjFind against established alternatives across key methodological dimensions.

Table: Methodological Comparison of FBA Approaches

| Method | Core Approach | Objective Function | Data Integration | Network Topology Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | Combines MPA with FBA using optimization | Infers weighted combination of fluxes | Experimental flux data | High (Pathway-based via minimum cut) |

| Traditional FBA | Linear programming optimization | Predefined single reaction (e.g., biomass) | Growth/no-growth data | Low (Constraint-based only) |

| ObjFind | Multi-objective optimization scalarization | Weighted sum of fluxes across all reactions | Experimental flux data | Medium (Network-wide weights) |

| rFBA | Incorporates Boolean regulatory rules | Predefined with regulatory constraints | Gene expression data | Medium (Through regulatory rules) |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Supervised learning from omics data | Implicit in training data | Transcriptomics/proteomics data | Low (Pattern recognition-based) |

TIObjFind distinguishes itself through its tight integration of pathway topology with optimization principles. While traditional FBA relies on predefined objective functions that may not reflect actual cellular priorities under specific conditions, TIObjFind infers context-dependent objectives directly from experimental measurements [5] [2]. Compared to its predecessor ObjFind, which assigned weights across all network reactions, TIObjFind's pathway-focused approach enhances biological interpretability while reducing overfitting risks [2]. Unlike machine learning methods that operate as black boxes, TIObjFind maintains a direct connection to biochemical constraints, ensuring predicted fluxes remain thermodynamically feasible [30].

Performance Metrics and Validation

Quantitative assessment of FBA methodologies requires multiple validation metrics to evaluate predictive accuracy and biological relevance. The following table compares the performance of TIObjFind against alternative approaches using standardized evaluation criteria.

Table: Performance Comparison of FBA Validation Frameworks

| Method | Flux Prediction Error | Condition Adaptability | Interpretability | Computational Demand | Validation Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | Low (Case-specific reduction) [5] | High (Stage-specific objectives) [5] | High (Pathway-level CoIs) [5] | Medium (Optimization + MPA) [5] | Strong (Experimental flux alignment) [5] |

| Traditional FBA | Variable (Condition-dependent) [9] | Low (Static objectives) [9] | Medium (Flux distribution only) | Low (Single LP) | Weak (Growth/no-growth only) [9] |

| ObjFind | Medium (Potential overfitting) [2] | Medium (Weight adjustments) | Medium (Reaction-level weights) | Medium (Multi-objective optimization) | Medium (Flux alignment) [2] |

| 13C-MFA | Very Low (Gold standard) [9] | Low (Condition-specific fitting) | High (Experimentally determined) | High (Isotopic simulation) | Very Strong (Direct experimental fit) [9] |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Low (Small prediction errors) [30] | High (Condition-trained models) | Low (Black box) | Variable (Training vs. prediction) | Medium (Statistical measures) [30] |

In practical applications, TIObjFind has demonstrated significant reductions in prediction error while improving alignment with experimental data [5]. The framework's capability to capture stage-specific metabolic objectives was validated through case studies examining Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and a multi-species isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) system [5] [2]. In these implementations, TIObjFind successfully identified shifting metabolic priorities across different biological stages, achieving a good match with observed experimental data [5]. The Coefficients of Importance derived through the framework provided quantitative insights into how different pathways contribute to cellular adaptation under changing environmental conditions.

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Protocol for TIObjFind Implementation

Implementing the TIObjFind framework requires a systematic experimental and computational workflow. The following protocol outlines the key steps for applying TIObjFind to validate FBA predictions against experimental flux data:

Experimental Flux Data Collection: Acquire quantitative flux measurements through ¹³C-tracer experiments or isotopic nonstationary metabolic flux analysis (INST-MFA) [9]. Target key central metabolic reactions and exchange fluxes to establish a ground truth for validation.

Stoichiometric Model Preparation: Curate a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction or core metabolic model containing relevant pathways. Ensure mass and charge balance in all reactions and verify network connectivity.

Constraint Definition: Establish physiological constraints based on experimental conditions, including:

TIObjFind Optimization Execution:

- Implement the single-level KKT reformulation with duality theorem

- Solve the optimization problem to obtain best-fit flux distributions

- Construct the Mass Flow Graph from FBA solutions

- Apply the minimum-cut algorithm to identify critical pathways

- Calculate Coefficients of Importance for key reactions [5] [28]

Validation and Interpretation:

- Compare TIObjFind predictions with experimental flux data

- Analyze pathway-level Coefficients of Importance to infer cellular objectives

- Identify shifts in metabolic priorities across conditions or biological stages

- Validate inferred objectives through genetic or environmental perturbations [5]

This protocol emphasizes the iterative nature of model validation, where discrepancies between TIObjFind predictions and experimental data may indicate either methodological limitations or opportunities to discover novel metabolic regulation [9].

Case Study: Clostridium acetobutylicum Fermentation

The application of TIObjFind to glucose fermentation by Clostridium acetobutylicum demonstrates its capability to capture dynamic metabolic adaptations [5] [2]. In this case study, the framework was used to determine pathway-specific weighting factors that explain observed flux distributions during different fermentation phases [5]. The analysis revealed shifting Coefficients of Importance for reactions involved in acid production versus solventogenesis, aligning with known metabolic transitions in this organism.

Through the implementation of different weighting strategies, researchers assessed the influence of Coefficients of Importance on flux predictions, demonstrating their significant impact on reducing prediction errors while improving alignment with experimental data [5]. The pathway-centric approach of TIObjFind enabled identification of key metabolic bottlenecks and alternative routing strategies that would be overlooked by traditional FBA with static objective functions. This case study highlights how TIObjFind moves beyond mere flux prediction to provide mechanistic insights into metabolic adaptation mechanisms.

Case Study: Multi-Species IBE System

In a more complex application, TIObjFind was applied to a multi-species system comprising C. acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii for isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) production [5] [2]. This case study exemplified the framework's ability to handle multi-organism metabolic networks and identify species-specific contributions to overall system performance. The Coefficients of Importance served as hypothesis coefficients within the objective function to assess cellular performance in a community context [5].

The TIObjFind framework successfully captured stage-specific metabolic objectives throughout the fermentation process, demonstrating a good match with observed experimental data [5] [2]. The analysis revealed how metabolic分工 emerges in microbial consortia, with different species optimizing different metabolic objectives that collectively enhance system performance. This application underscores TIObjFind's value in analyzing complex biological systems where traditional single-objective FBA approaches would fail to capture emergent metabolic behaviors.

Essential Research Tools for FBA Validation

Computational and Experimental Reagents

Implementing robust FBA validation frameworks like TIObjFind requires specific computational tools and experimental approaches. The table below catalogues essential "research reagents" for conducting such studies, along with their primary functions and applications.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for FBA Validation Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application in TIObjFind |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATLAB with COBRA Toolbox | Software | Constraint-based modeling and analysis | Implementing optimization and MPA [5] [9] |

| Python with pySankey | Software | Data visualization and workflow design | Visualizing flux distributions and pathways [5] |

| 13C-labeled substrates | Biochemical reagent | Tracing metabolic flux through networks | Generating experimental flux data for validation [9] |

| Mass Spectrometry/NMR | Analytical instrument | Measuring isotopic labeling patterns | Quantifying mass isotopomer distributions [9] |

| Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm | Computational method | Solving graph min-cut/max-flow problems | Identifying critical pathways in Mass Flow Graph [5] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Knowledge base | Representing biochemical reaction networks | Providing stoichiometric constraints [5] [9] |

| MEMOTE Test Suite | Validation tool | Quality control for metabolic models | Ensuring model stoichiometric consistency [9] |

Implementation Considerations

Successful application of TIObjFind requires careful attention to several implementation factors. Data quality is paramount, as the framework's output depends heavily on accurate experimental flux measurements [9]. ¹³C-MFA experiments should be designed with multiple tracer inputs to sufficiently constrain flux estimates and reduce confidence intervals [9]. Computational resources must accommodate the dual-layer optimization and graph analysis, which, while more demanding than traditional FBA, remains tractable for genome-scale models using efficient algorithms like Boykov-Kolmogorov [5] [2].

Researchers should also consider model scope when applying TIObjFind. While the framework can operate on genome-scale models, focusing on core metabolic pathways often enhances interpretability without sacrificing biological insights [9]. Additionally, the selection of start and target reactions for pathway analysis should reflect biologically meaningful inputs and outputs, such as glucose uptake for start reactions and product secretion or biomass formation as targets [5] [2]. These implementation decisions significantly influence the biological relevance of the derived Coefficients of Importance and their utility in understanding metabolic adaptation.

Integration with Multi-Omics Data

The TIObjFind framework presents significant opportunities for expansion through integration with multi-omics data types. While the current implementation primarily utilizes flux data, future iterations could incorporate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic measurements to further constrain objective function identification [30]. Such integration would enable more accurate prediction of metabolic behavior across diverse genetic and environmental contexts. Machine learning approaches that leverage omics data for flux prediction show promise in this regard [30], and their combination with TIObjFind's topology-informed optimization could yield powerful hybrid methodologies.

Another promising direction involves extending TIObjFind to dynamic systems through integration with dynamic FBA (dFBA) [5] [9]. This advancement would enable researchers to track temporal changes in Coefficients of Importance, capturing how metabolic objectives evolve throughout bioprocesses or physiological transitions. Such capability would be particularly valuable in biotechnology applications where understanding time-dependent metabolic reprogramming could optimize production strategies.

Concluding Perspectives

The TIObjFind framework represents a significant advancement in FBA validation by addressing the critical challenge of objective function selection through its novel integration of metabolic pathway analysis with optimization principles. Its introduction of Coefficients of Importance provides a quantitative mechanism for inferring cellular objectives directly from experimental data, moving beyond the assumption of static optimization goals that limits traditional FBA [5] [2]. The framework's pathway-centric approach enhances biological interpretability while maintaining mathematical rigor, creating a valuable bridge between computational predictions and experimental observations.

As metabolic engineering and systems biology increasingly tackle complex biological systems, from microbial consortia to human diseases, methodologies like TIObjFind that explicitly address context-dependent metabolic optimization will become increasingly essential [5] [9]. By providing a systematic approach for identifying metabolic objective functions that align with experimental data, TIObjFind enhances both the predictive power and biological relevance of constraint-based modeling, ultimately strengthening our ability to understand and engineer metabolic systems.

Constraint-based metabolic modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), serves as a fundamental tool for predicting intracellular metabolic fluxes in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Traditional FBA predicts flux distributions by assuming organisms optimize objectives such as biomass maximization, relying solely on stoichiometric constraints and external flux measurements. However, these predictions often diverge from experimental data as they largely ignore the complex regulatory layers of transcriptional and translational control that significantly influence metabolic activity.

The integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data as additional constraints represents a sophisticated advancement in refining flux predictions. This multi-omics approach aims to narrow the solution space of possible flux distributions, thereby enhancing the biological fidelity of models. This guide objectively compares the performance of various methods that incorporate transcriptomic and proteomic constraints against traditional FBA, evaluating them against experimental fluxomics data.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Several computational strategies have been developed to integrate expression data into metabolic models. The protocols below detail the workflows for key methods, enabling direct comparison.

Linear Bound Flux Balance Analysis (LBFBA)

LBFBA is a hybrid approach that uses expression data to impose soft, violable bounds on reaction fluxes.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Training Phase: Utilize a training dataset containing paired transcriptomic/proteomic data and experimentally determined fluxomics data (e.g., from 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis) for a set of reactions (

Rexp). - Parameter Estimation: For each reaction in

Rexp, calculate parameters (a_j,b_j,c_j) that define its linear flux bounds as a function of its gene/protein expression level (g_j). The bounds are formulated as:v_glucose · (a_j * g_j + c_j) ≤ v_j ≤ v_glucose · (a_j * g_j + b_j). - Prediction Phase: For a new condition with only expression data available, calculate the expression-derived flux bounds for reactions in