The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle in Metabolic Engineering: A Framework for Accelerating Strain Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a foundational and iterative framework in modern metabolic engineering.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle in Metabolic Engineering: A Framework for Accelerating Strain Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a foundational and iterative framework in modern metabolic engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles of the DBTL cycle, detailing its application in optimizing microorganisms for the production of valuable compounds, from antibiotics to biotherapeutics. The content delves into methodological advancements, including the integration of automation and machine learning, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies to escape 'involution' cycles, and validates the approach through comparative case studies and performance analysis. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current trends, this article serves as a guide for implementing efficient DBTL cycles to streamline bioprocess development and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

Foundations of the DBTL Cycle: The Core Engine of Modern Metabolic Engineering

The design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle is a foundational, iterative framework in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology used to develop and optimize microbial strains for the production of valuable compounds [1]. By systematically cycling through four defined phases—Design, Build, Test, and Learn—researchers can efficiently navigate complex biological systems to enhance product titers, yields, and productivity (TYR) [1]. This iterative process is central to modern biofoundries and is increasingly augmented by machine learning (ML) and automation, which help to overcome challenges such as combinatorial explosion of the design space and the costly nature of experimental trials [1] [2]. This guide details the technical execution of each phase within the context of metabolic engineering for a professional audience.

The Design Phase

The Design phase involves the rational selection of genetic targets and the planning of genetic constructs for the subsequent Build phase. The goal is to propose specific genetic modifications expected to improve microbial performance.

- Objective and Process: The objective is to select engineering targets, such as genes to be knocked out, overexpressed, or modulated. In classical metabolic engineering, this often involves sequential debottlenecking of rate-limiting steps. However, combinatorial pathway optimization, which targets multiple components simultaneously, reduces the chance of missing the global optimum pathway configuration [1]. Initial designs can be informed by prior knowledge, hypotheses, or computational models. In a knowledge-driven DBTL approach, upstream in vitro investigations in cell lysate systems can be used to assess enzyme expression levels and inform the initial design for the in vivo environment [3].

- Key Methodologies and Tools:

- Mechanistic Kinetic Modeling: Using ordinary differential equation (ODE) models to simulate pathway behavior and predict the effect of perturbations, such as changes in enzyme concentration, on metabolic flux [1].

- Machine Learning and AI: ML models can propose new designs by learning from data generated in previous DBTL cycles. More recently, large language models (LLMs) trained on protein sequences, such as ESM-2, are used to predict the fitness of protein variants, aiding in the design of high-quality mutant libraries for enzyme engineering [2].

- Library Design: For pathway optimization, designs are often based on a DNA library of components (e.g., promoters, ribosomal binding sites) that affect enzyme levels [1]. Tools like the UTR Designer can be used to modulate RBS sequences for fine-tuning gene expression [3].

The Build Phase

The Build phase is the physical implementation of the designed genetic constructs in the host organism. This phase is increasingly automated in biofoundries to ensure high throughput and reproducibility.

- Objective and Process: The objective is to rapidly and accurately assemble the designed genetic constructs and introduce them into the microbial host to create a library of strains. Automation is key to handling combinatorial libraries [2].

- Key Methodologies and Tools:

- Automated Molecular Cloning: Biofoundries, such as the Illinois Biological Foundry for Advanced Biomanufacturing (iBioFAB), use fully automated, modular workflows for cloning. This includes automated modules for mutagenesis PCR, DNA assembly, transformation, and colony picking [2].

- Genetic Toolkits: Common techniques include:

- Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Engineering: A powerful method for fine-tuning the relative expression levels of genes within an operon. This can be achieved by modulating the Shine-Dalgarno sequence to alter the translation initiation rate without significantly affecting secondary structures [3].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis (SDM): For protein engineering, a high-fidelity (HiFi) assembly-based mutagenesis method can be used to create variant libraries without the need for intermediate sequence verification, enabling a continuous workflow [2].

- Genome Engineering: Using CRISPR/Cas systems or other methods to make genomic modifications, such as knocking out regulatory genes (e.g., tyrR) or mutating feedback inhibition (e.g., in tyrA) to increase precursor availability [3].

The Test Phase

The Test phase involves cultivating the newly built strains and characterizing their performance through analytical methods to collect high-quality data.

- Objective and Process: The objective is to measure the fitness or performance of the engineered strains, typically by quantifying the production of the target compound (titer), biomass yield, and growth rate. This data is essential for the subsequent Learn phase.

- Key Methodologies and Tools:

- Cultivation Systems: Strains are cultivated in controlled bioreactors, from small-scale microtiter plates to 1 L batch reactors, to monitor biomass growth and substrate consumption [1] [3].

- Analytical Chemistry: Techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are used to quantify extracellular metabolites, precursors, and products (e.g., L-tyrosine, L-DOPA, dopamine) [3].

- Advanced Metabolomics:

- Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI): Methods like "RespectM" enable single-cell level metabolomics, detecting metabolites from hundreds of cells per hour. This reveals metabolic heterogeneity within a cell population, generating large datasets that can power deep learning models [4].

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS): Crude cell lysate systems can be used to test pathway enzyme expression and function in vitro, bypassing whole-cell constraints [3].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics in the Test Phase

| Metric | Description | Example Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Titer | Concentration of the target product in the fermentation broth | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L of dopamine [3] |

| Yield | Amount of product per unit of biomass | 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g˅biomass of dopamine [3] |

| Productivity | Rate of product formation | Often reported as mg/L/h |

| Enzyme Activity | Catalytic efficiency of engineered enzymes | 26-fold improvement in phytase activity at neutral pH [2] |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity | Variation in metabolite levels across a cell population | 4,321 single-cell metabolomics data points [4] |

The Learn Phase

The Learn phase is where data from the Test phase is analyzed to extract insights, update models, and generate new hypotheses to inform the design of the next DBTL cycle.

- Objective and Process: The objective is to learn important characteristics of the engineered pathway or enzyme from the experimental data. The complexity of biological systems often means that the outcomes of genetic perturbations are non-intuitive, making this a critical phase [1].

- Key Methodologies and Tools:

- Machine Learning: Supervised ML models are trained on the experimental data to predict strain performance based on genetic design.

- Model Training: In the low-data regime typical of early DBTL cycles, gradient boosting and random forest models have been shown to be robust to training set biases and experimental noise [1].

- Heterogeneity-Powered Learning (HPL): Single-cell metabolomics data, representing metabolic heterogeneity, can be used to train deep neural networks (DNNs). These HPL-based models can then suggest minimal genetic operations to achieve a desired metabolic output, such as high triglyceride production [4].

- Recommendation Algorithms: Once a model is trained, algorithms are used to recommend the most promising designs for the next DBTL cycle. These algorithms balance exploration (testing new regions of the design space) and exploitation (focusing on areas with predicted high performance) [1].

- Machine Learning: Supervised ML models are trained on the experimental data to predict strain performance based on genetic design.

Table 2: Machine Learning Models Used in the Learn Phase

| Model/Algorithm | Application in DBTL Cycles | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | Predicting strain performance from genetic design data [1] | High predictive performance with small datasets |

| Random Forest | Predicting strain performance from genetic design data [1] | Robust to noise and bias in training data |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Learning from single-cell metabolomics data (HPL) [4] | Can model complex, non-linear relationships in large datasets |

| Epistasis Model (EVmutation) | Guiding the design of protein variant libraries [2] | Uses evolutionary sequences to predict mutation effects |

| Protein LLM (ESM-2) | Designing initial protein variant libraries [2] | Predicts amino acid likelihoods from sequence context |

DBTL Workflow and Cycle Strategies

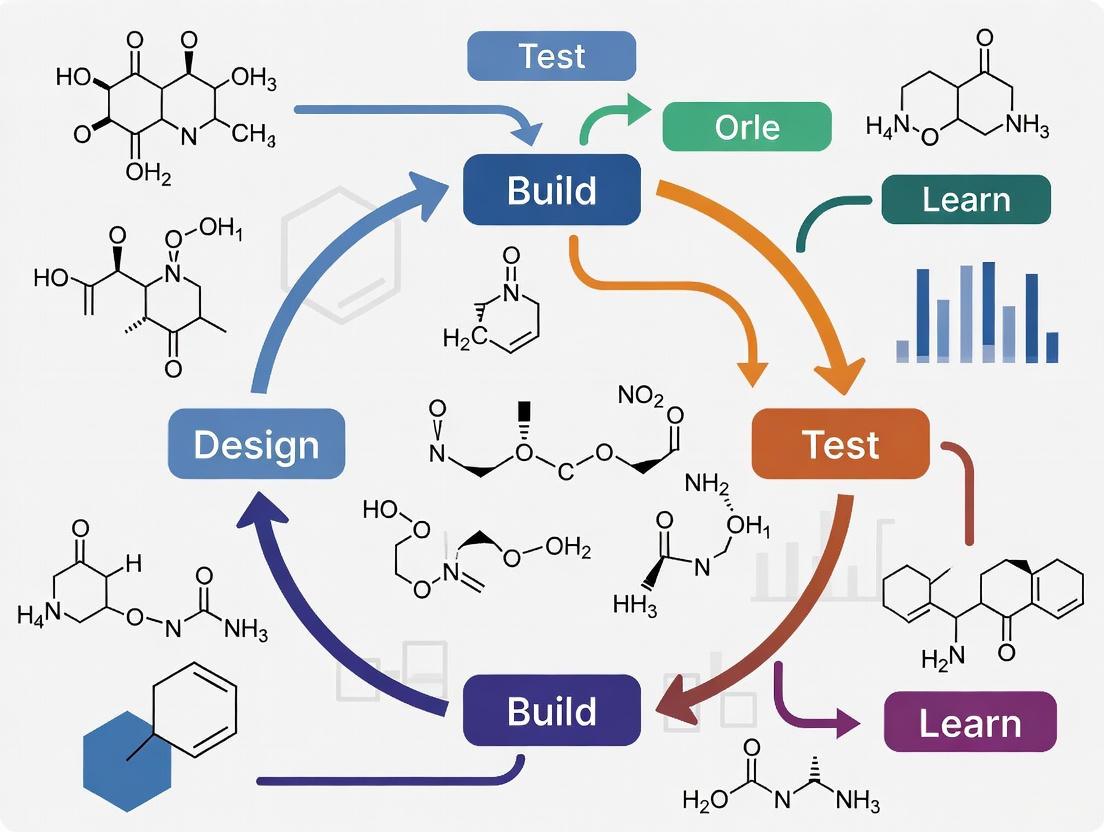

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative workflow of a DBTL cycle, incorporating automated and AI-powered elements.

Strategy for Efficient Cycling: A key operational question is how to allocate resources across multiple DBTL cycles. Simulation studies using kinetic models suggest that when the total number of strains to be built is limited, it is more effective to start with a large initial DBTL cycle rather than distributing the same number of strains evenly across every cycle [1]. This initial large dataset provides a more robust foundation for the machine learning models in the Learn phase, leading to better recommendations in subsequent cycles.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and resources essential for executing a DBTL cycle in metabolic engineering.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Cycles

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| RBS Library | A predefined set of ribosomal binding site sequences used to fine-tune the translation initiation rate of genes. | Fine-tuning expression of hpaBC and ddc genes in a dopamine pathway [3]. |

| Promoter Library | A collection of promoter sequences of varying strengths to control transcription levels of pathway genes. | Combinatorial optimization of enzyme concentrations in a synthetic pathway [1]. |

| pET / pJNTN Plasmid Systems | Common plasmid vectors used for heterologous gene expression in E. coli. | Serving as storage vectors for genes or for constructing plasmid libraries for pathway expression [3]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System | A crude cell lysate system used for in vitro transcription and translation, bypassing whole-cell constraints. | Testing relative enzyme expression levels and pathway function in vitro before DBTL cycling [3]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) | An analytical technique for detecting and visualizing the spatial distribution of metabolites. | Acquiring single-cell level metabolomics data (e.g., using RespectM) to study metabolic heterogeneity [4]. |

| Automated Biofoundry (e.g., iBioFAB) | An integrated robotic platform for automating laboratory processes in synthetic biology. | Executing end-to-end protein engineering workflows, from library construction to functional assays [2]. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., ESM-2, EVmutation) | Computational models used to predict the effect of genetic changes on protein function or pathway performance. | Designing high-quality initial mutant libraries for enzyme engineering campaigns [2]. |

The DBTL cycle is a powerful, iterative framework that structures the scientific and engineering process in metabolic engineering. Its effectiveness is greatly enhanced by the integration of automation, high-throughput analytics, and artificial intelligence. As these technologies continue to advance, they will further accelerate the DBTL cycle, reducing the time and cost required to develop robust microbial cell factories for the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and sustainable chemicals.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework for optimizing microbial cell factories in metabolic engineering. This iterative process enables researchers to progressively enhance strain performance through consecutive rounds of design intervention, genetic construction, phenotypic testing, and data analysis. Recent advances demonstrate how the DBTL cycle, particularly when augmented with upstream knowledge and mechanistic insights, accelerates the development of high-yielding strains for bio-based production. This technical guide examines the core principles and implementation strategies of the DBTL framework, highlighting its spiral nature where each iteration generates valuable knowledge that informs subsequent cycles, ultimately driving continuous improvement toward optimal strain performance.

The DBTL cycle has emerged as a cornerstone methodology in modern metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, providing a structured approach to strain development. This engineering paradigm integrates tools from synthetic biology, enzyme engineering, omics technologies, and evolutionary engineering to optimize metabolic pathways in microbial hosts [5]. The cyclic nature of this process distinguishes it from traditional linear approaches, creating a feedback loop where learning from each test phase directly informs the subsequent design phase. This iterative refinement enables researchers to navigate the complexity of biological systems methodically, addressing multiple engineering targets while accumulating mechanistic understanding of pathway regulation and host physiology.

In industrial biotechnology, the DBTL framework has revolutionized the development of microbial cell factories as sustainable alternatives to traditional petrochemical processes [5]. The cycle begins with rational design based on available knowledge, proceeds to physical construction of genetic variants, advances to rigorous phenotypic testing, and culminates in data analysis that extracts meaningful insights for the next iteration. The power of this approach lies in its flexibility—it can be applied across different microbial platforms, from well-established workhorses like Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli to non-conventional organisms, with each spiral of the cycle propelling the strain closer to its performance targets.

Deconstructing the DBTL Cycle: Phase-by-Phase Analysis

Design Phase: Rational Planning of Strain Engineering

The Design phase establishes the foundational blueprint for strain modification, combining computational tools, prior knowledge, and strategic planning. In metabolic engineering projects, this typically involves identifying target pathways, selecting appropriate enzymes, choosing regulatory elements, and predicting potential metabolic bottlenecks. Modern design strategies increasingly incorporate in silico modeling and bioinformatics tools to prioritize engineering targets, moving beyond random selection toward hypothesis-driven approaches [3]. The design phase may also include enzyme engineering strategies to alter substrate specificity or improve catalytic efficiency, and genome-scale modeling to predict system-wide consequences of pathway manipulations.

A significant advancement in this phase is the "knowledge-driven DBTL" approach, which incorporates upstream in vitro investigations before committing to genetic modifications in the production host [3]. For instance, researchers developing dopamine-producing E. coli strains first conducted cell lysate studies to assess enzyme expression levels and pathway functionality under controlled conditions. This pre-validation enables more informed selection of engineering targets for the subsequent in vivo implementation, potentially reducing the number of DBTL iterations required to achieve optimal performance. The design phase thus transforms from a purely computational exercise to an experimentally informed strategy that de-risks the subsequent build and test phases.

Build Phase: Genetic Construction of Engineered Strains

The Build phase translates design specifications into physical biological entities through genetic engineering. This stage encompasses the assembly of DNA constructs, pathway integration into host chromosomes, and development of variant libraries for testing. Advanced modular cloning techniques and automated DNA assembly platforms have dramatically accelerated this phase, enabling high-throughput construction of genetic variants [3]. For metabolic pathways, this often involves combining multiple enzyme-coding genes with appropriate regulatory elements into coordinated expression systems.

A key build strategy featured in recent implementations is ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering for fine-tuning gene expression in synthetic pathways [3]. By modulating the Shine-Dalgarno sequence without altering the coding sequence or creating secondary structures, researchers can precisely control translation initiation rates for optimal metabolic flux. In the dopamine production case study, researchers created RBS libraries to systematically vary the expression levels of the hpaBC and ddc genes, enabling identification of optimal expression ratios for maximal dopamine yield [3]. The build phase increasingly leverages automation and standardized genetic parts to enhance reproducibility and scalability across multiple DBTL iterations.

Test Phase: Phenotypic Characterization of Engineered Strains

The Test phase involves rigorous experimental characterization of built strains to evaluate performance against design specifications. This encompasses cultivation experiments under controlled conditions, analytical chemistry techniques to quantify metabolites, and omics analyses to assess system-wide responses. For metabolic engineering projects, the test phase typically measures key performance indicators such as product titer, yield, productivity, and cellular fitness [3]. Advanced cultivation platforms enable parallel testing of multiple strain variants, generating robust datasets for the subsequent learning phase.

In the dopamine production case study, researchers employed minimal medium cultivations with precise monitoring of biomass and dopamine accumulation over time [3]. The test phase quantified both volumetric production (69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L) and specific production (34.34 ± 0.59 mg/gbiomass), representing a 2.6-fold and 6.6-fold improvement over previous reports, respectively. Similarly, in the C. glutamicum C5 chemical production platform, the test phase evaluated the performance of engineered strains in converting L-lysine to higher-value chemicals [5]. Comprehensive testing generates the essential data required for meaningful analysis in the learning phase, creating a direct link between genetic modifications and phenotypic outcomes.

Learn Phase: Data Analysis and Insight Generation

The Learn phase represents the critical knowledge extraction component of the cycle, where experimental data transforms into actionable insights. This stage employs statistical analysis, machine learning algorithms, and mechanistic modeling to identify relationships between genetic modifications and phenotypic outcomes [3]. The learning phase answers fundamental questions about which engineering strategies succeeded, which failed, and why—thereby generating hypotheses for the next design iteration. For researchers, this phase involves comparing experimental results with design predictions, identifying performance bottlenecks, and proposing new modification targets.

In the knowledge-driven DBTL approach, the learning phase extends beyond correlation to establish mechanistic causality [3]. For instance, dopamine production studies revealed how GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence directly influences RBS strength and consequently pathway performance. The iGEM Engineering Committee emphasizes that in this phase, teams should "link your experimental data back to your design and complete the first iteration of the DBTL cycle," using the data to "create informed decisions as to what needs to be changed in your design" [6]. Effective learning requires both quantitative analysis of performance metrics and qualitative understanding of biological mechanisms that explain the observed phenotypes.

Quantitative Analysis of DBTL Implementation

Table 1: Performance Metrics from DBTL-Optimized Dopamine Production in E. coli [3]

| Strain Generation | Dopamine Titer (mg/L) | Specific Dopamine Production (mg/gbiomass) | Fold Improvement Over Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Literature) | 27.0 | 5.17 | 1.0 |

| DBTL-Optimized | 69.03 ± 1.2 | 34.34 ± 0.59 | 2.6 (titer), 6.6 (specific) |

Table 2: Clay Prototype Comfort Ratings for Pipette Grip Design [7]

| Mold Iteration | Thin Section (mm) | Mid Section (mm) | Thick Section (mm) | Comfort Rating (out of 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.24 | 11.0 | 10.55 | 8 |

| 2 | 6.35 | 19.0 | 14.34 | 8 |

| 3 | 10.78 | (missed) | 37.0 | 2 |

| 4 | 10 | 26 | 13 | 4.5 |

| 5 | without clay | without clay | without clay | 5 |

| 6 | 7.54 | 23.05 | 14.15 | 6 |

| 7 | 5.65 | 13.38 | 19.68 | 8.2 |

| 8 | 10.47 | 10.47 | 11.11 | 10 |

Experimental Protocols for DBTL Implementation

Knowledge-Driven DBTL with Upstream In Vitro Testing

The knowledge-driven DBTL cycle incorporates upstream in vitro investigation before proceeding to in vivo strain engineering [3]. This protocol begins with preparation of crude cell lysate systems from potential production hosts. The reaction buffer is prepared with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) supplemented with 0.2 mM FeCl₂, 50 µM vitamin B6, and pathway-specific substrates (1 mM L-tyrosine or 5 mM L-DOPA for dopamine production) [3]. Heterologous genes are cloned into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pJNTN system) and expressed in the lysate system. Pathway functionality is assessed by measuring substrate conversion and product formation rates, enabling preliminary optimization of enzyme ratios and identification of potential bottlenecks before genetic modification of the production host.

Following in vitro validation, the protocol proceeds to high-throughput RBS engineering for in vivo implementation. Genetic constructs are designed with modular RBS sequences varying in Shine-Dalgarno composition while maintaining constant coding sequences. Library construction employs automated DNA assembly techniques, with transformation into appropriate production hosts (e.g., E. coli FUS4.T2 for dopamine production) [3]. Strain cultivation utilizes minimal medium containing 20 g/L glucose, 10% 2xTY medium, phosphate buffer, MOPS, vitamin B6, phenylalanine, and essential trace elements. Cultivation proceeds with appropriate antibiotics and inducers (e.g., 1 mM IPTG), followed by analytical measurement of target metabolites to identify top-performing variants for the next DBTL iteration.

Iterative Prototyping for Hardware-Design Integration

The DBTL cycle also applies to hardware development complementing biological engineering, as demonstrated by the UBC iGEM team's pipette add-on project [7]. The protocol begins with preliminary CAD modeling based on user needs assessment (Design phase). The Build phase employs rapid prototyping with accessible materials like air-dry clay to create physical models for initial user testing. The Test phase involves structured user interviews with quantitative comfort ratings recorded for different design iterations (see Table 2). During interviews, users physically interact with prototypes and provide comfort feedback, enabling dimensional optimization.

The Learn phase employs decision matrices to translate qualitative user feedback into quantitative design parameters [7]. For the pipette project, this revealed that "reducing the need for extensive gripping" was the highest priority (60% weight), followed by maintaining low weight (28% weight), using soft materials (8% weight), and reducing knob pressure (4% weight) [7]. This learning directly informed the next design iteration, with prototype modifications focusing on these weighted parameters. The process demonstrates how DBTL cycles effectively integrate user-centered design into biological engineering projects.

Visualizing DBTL Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: The Core DBTL Cycle in Metabolic Engineering

Diagram 2: Knowledge-Driven DBTL with Upstream In Vitro Testing

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in DBTL Cycle | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Crude Cell Lysate Systems | Enables in vitro pathway testing before in vivo implementation | Testing enzyme expression levels and pathway functionality [3] |

| RBS Library Kits | Facilitates fine-tuning of gene expression in metabolic pathways | Modulating translation initiation rates for optimal metabolic flux [3] |

| Minimal Medium Formulations | Provides controlled cultivation conditions for phenotype testing | Assessing strain performance under defined nutritional conditions [3] |

| Analytical Standards | Enables accurate quantification of metabolites and products | Measuring dopamine production titers via HPLC or LC-MS [3] |

| CAD Software | Supports hardware design for experimental automation | Creating 3D models of custom lab equipment [7] |

| Data Analysis Platforms | Facilitates learning phase through statistical analysis | Using R, MATLAB, or Python for data processing and visualization [6] |

The iterative nature of the DBTL cycle creates a spiral of continuous improvement in metabolic engineering, where each iteration builds upon knowledge gained from previous cycles. This structured approach transforms strain development from a trial-and-error process to a systematic engineering discipline, efficiently navigating the complexity of biological systems toward optimal performance. The integration of upstream knowledge generation, automated workflows, and multi-omic analyses further enhances the efficiency of each DBTL iteration, accelerating the development of microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction. As DBTL methodologies continue to evolve with advances in synthetic biology and automation, they will undoubtedly remain central to the optimization of strain performance for industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

Overcoming Combinatorial Explosions in Pathway Optimization

Metabolic engineering aims to reprogram microbial metabolism to produce valuable compounds, from pharmaceuticals to sustainable fuels [8]. A fundamental strategy involves introducing heterologous pathways or optimizing native ones. However, engineering these pathways often reveals significant imbalances in metabolic flux, leading to the accumulation of toxic intermediates, side products, and suboptimal yields [8]. Classical "de-bottlenecking" approaches address these limitations sequentially. While sometimes successful, this method often fails to find a globally optimal solution for the pathway because it neglects the complex, holistic interactions between multiple pathway components and the host's native metabolism [8] [1].

Combinatorial pathway optimization has emerged as a powerful alternative, enabled by dramatic reductions in the cost of DNA synthesis and advances in DNA assembly and genome editing [8]. This approach involves the simultaneous diversification of multiple pathway parameters—such as enzyme homologs, gene copy number, and regulatory elements—to create vast libraries of genetic variants [8]. The major constraint of this method is combinatorial explosion, where the number of potential permutations increases exponentially with the number of components being optimized [8] [1]. For example, diversifying just 10 pathway elements with 5 variants each generates 9,765,625 (5^10) unique combinations, making exhaustive screening experimentally infeasible [1].

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a structured framework to navigate this vast design space efficiently. By iteratively applying this cycle, researchers can gradually steer the optimization process toward high-performing strains with manageable experimental effort [1] [3] [9]. This guide details the core objectives and methodologies for overcoming combinatorial explosions within the DBTL paradigm.

The DBTL Cycle: A Framework for Efficient Optimization

The DBTL cycle is an iterative engineering process that transforms the daunting task of combinatorial optimization into a manageable, data-driven workflow. Its power lies in using information from each cycle to intelligently guide the design of the next, progressively focusing on a more promising and smaller region of the design space.

Table: The Four Phases of the DBTL Cycle and Their Role in Combating Combinatorial Explosion

| DBTL Phase | Core Objective | Key Activities | How It Addresses Combinatorial Explosion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Plan a library of genetic variants based on prior knowledge or data. | Selection of enzyme homologs, promoters, RBS sequences, and gene order; Use of statistical design (DoE) to reduce library size. | Reduces the initial search space from millions to a tractable number (e.g., 10s-100s) of representative constructs. |

| Build | Physically construct the designed genetic variants. | Automated DNA assembly, molecular cloning, and genome engineering. | Enables high-throughput, reliable construction of variant libraries, often leveraging robotics. |

| Test | Characterize the performance of the built variants. | Cultivation in microplates, automated metabolite extraction, analytics (e.g., LC-MS), and product quantification. | Generates high-quality data linking genotype to phenotype (e.g., titer, yield, rate) for the screened library. |

| Learn | Analyze data to extract insights and generate new hypotheses. | Statistical analysis, machine learning (ML) model training, and identification of limiting factors or optimal patterns. | Creates a predictive model of pathway behavior, which is used to design a more efficient library in the next cycle. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and information flow of an iterative DBTL cycle, highlighting how learning from one cycle directly informs the design of the next.

Core Strategies for Library Diversification

A primary lever for controlling combinatorial explosion is the strategic choice of which pathway elements to diversify. The goal is to maximize the potential for improvement while minimizing the number of variables.

Variation of Coding Sequences (CDS)

This strategy involves swapping the enzymes that catalyze each reaction. It is crucial when enzyme properties like catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, or inhibitor sensitivity are unknown or suspected to be suboptimal.

- Methodology: Identify multiple structural or functional gene homologs from different organisms for each enzymatic step in the pathway. These homologs can be sourced from public databases or metagenomic libraries [8]. For instance, to engineer xylose utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, researchers screened a library of xylose isomerase homologs from various bacteria to identify the most functional variant in yeast [8].

- Experimental Protocol:

- In silico Identification: Use tools like BLAST or enzyme-specific databases (e.g., BRENDA) to identify potential homologs.

- Gene Synthesis: Commercially synthesize the selected coding sequences with codon optimization for the host chassis.

- Standardized Assembly: Clone each homolog into a standardized expression vector (e.g., with a fixed promoter and RBS) using high-throughput DNA assembly methods like Golden Gate or Gibson Assembly.

- Screening: Transform the library into the production host and screen for the desired phenotype (e.g., product titer, growth rate).

Engineering of Expression Levels

Fine-tuning the expression level of each pathway gene is often the most effective way to balance metabolic flux and prevent the accumulation of intermediates.

- Methodology: Key tunable elements include:

- Promoter Strength: Replacing the native promoter with a library of constitutive or inducible promoters of varying strengths [8] [9].

- Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Engineering: Designing a library of RBS sequences with varying translation initiation rates (TIR) to control translational efficiency [8] [3]. Tools like the UTR Designer can assist in this process [3].

- Gene Dosage: Using plasmids with different origins of replication (copy numbers) or integrating varying gene copies into the genome [8] [9].

- Experimental Protocol (RBS Library Example):

- Library Design: Define a set of Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences with varying calculated strengths, ensuring minimal alteration to mRNA secondary structure [3].

- PCR-based Construction: Use overlap extension PCR or specialized cloning techniques (e.g., ligase cycling reaction) to generate a library of constructs where the target gene is preceded by different RBS variants.

- Characterization: Measure the resulting protein expression levels for a subset of variants via SDS-PAGE or fluorescence assays to validate the library's functional diversity.

Combined and Integrated Approaches

The most powerful optimization campaigns often simultaneously target multiple layers of regulation. For example, a single pathway can be optimized by combining the best-performing enzyme homologs with optimally tuned expression levels for each [8]. A notable example is the combinatorial refactoring of a 16-gene nitrogen fixation pathway, which involved the simultaneous optimization of promoters, RBSs, and gene order, leading to a significant improvement in function [8].

Key Methodologies for Managing Experimental Effort

Statistical Design of Experiments (DoE)

Instead of testing all possible combinations, DoE selects a representative subset of the full factorial library. This allows for the efficient exploration of the design space and the statistical identification of the main effects and interactions of each diversified component.

- Application: In one study optimizing a 4-gene flavonoid pathway, a combinatorial design of 2592 possible configurations was reduced to just 16 representative constructs using orthogonal arrays and a Latin square design—a compression ratio of 162:1. Screening this small library was sufficient to identify copy number and specific promoter strengths as the most critical factors influencing production [9].

Machine Learning (ML)-Guided Recommendation

Machine learning has become a cornerstone of the "Learn" phase, enabling semi-automated strain recommendation.

- Workflow: In the first DBTL cycle, an initial library of strains is built and tested to generate a dataset. An ML model (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) is trained on this data to learn the complex relationships between genetic design features (e.g., promoter strength, RBS sequence) and phenotypic outcomes (e.g., titer) [1]. This model then predicts the performance of all possible, untested designs and recommends a shortlist of the most promising candidates for the next "Build" phase.

- Performance: Simulation studies show that ML models like gradient boosting and random forest are particularly effective in the low-data regime typical of early DBTL cycles and are robust to experimental noise [1]. An Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) that uses an ensemble of models has been successfully applied to optimize the production of compounds like dodecanol and tryptophan [1].

Knowledge-Driven and Hybrid Approaches

Incorporating prior mechanistic knowledge can dramatically improve the efficiency of the initial DBTL cycle.

- In Vitro Prototyping: Before moving to in vivo strain construction, pathway bottlenecks can be identified using cell-free transcription-translation systems (TXTL) or crude cell lysate systems [3]. For dopamine production in E. coli, researchers first used a cell lysate system to test different relative expression levels of the pathway enzymes. The insights gained directly informed the design of the in vivo RBS library, leading to a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over the state-of-the-art in just one DBTL cycle [3].

- Kinetic Modeling: Mechanistic kinetic models of the pathway embedded in cell physiology can be used to simulate DBTL cycles in silico. This provides a framework for benchmarking ML algorithms and optimizing the DBTL strategy itself (e.g., determining the ideal number of strains to build per cycle) before committing to costly wet-lab experiments [1].

Table: Comparison of Strategies for Reducing Experimental Effort

| Strategy | Mechanism | Best-Suited Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Uses statistical principles to select a representative subset of all combinations. | Early DBTL cycles with many factors to explore; when factor interactions are unknown. | Efficiently identifies major influential factors with minimal experiments. | Limited ability to model highly non-linear, complex interactions compared to ML. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Learns a non-linear model from data to predict high-performing designs. | Later DBTL cycles after initial data is available; complex pathways with interacting elements. | Can find non-intuitive optimal combinations; improves with each cycle. | Requires initial dataset; predictive performance can be poor with very small or biased data. |

| Knowledge-Driven Design | Uses upstream experiments (e.g., in vitro tests) or prior knowledge to constrain initial design. | Pathways with known toxic intermediates or well-characterized enzymes. | Reduces initial blind exploration; provides mechanistic insights. | Requires established upstream protocols; may introduce bias if knowledge is incomplete. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Pathway Optimization |

|---|---|

| Commercial DNA Synthesis | Provides the raw genetic material for constructing variant libraries of coding sequences, promoters, and RBSs [8]. |

| Standardized Plasmid Vectors | Act as modular scaffolds for the assembly of pathway variants. Vectors with different origins of replication (e.g., ColE1, p15a, pSC101) allow for control of gene dosage [9]. |

| High-Throughput DNA Assembly Kits (e.g., Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate, LCR) | Enable the rapid, parallel, and often automated assembly of multiple DNA parts into functional constructs [8] [9]. |

| Cell-Free Transcription-Translation (TXTL) Systems | Used for in vitro prototyping of pathways to rapidly identify flux bottlenecks and inform in vivo library design without cellular constraints [3]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Library Kits | Pre-designed collections of RBS sequences with characterized strengths, used for fine-tuning translational efficiency of pathway genes [3]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., target product, pathway intermediates) | Essential for calibrating analytical equipment (e.g., LC-MS) and quantitatively measuring the performance of engineered strains during the Test phase [9]. |

Combinatorial explosion is not an insurmountable barrier but a fundamental characteristic of biological complexity that can be managed through a disciplined DBTL framework. The convergence of robust library diversification strategies, high-throughput automation, and sophisticated computational learning methods has transformed pathway optimization from a sequential, trial-and-error process into a rapid, iterative, and predictive engineering science. By strategically applying statistical design, machine learning, and mechanistic insights, researchers can systematically navigate the vast combinatorial search space to develop high-performing microbial cell factories with unprecedented efficiency.

The field of metabolic engineering has undergone a radical transformation, evolving from a purely descriptive science into a sophisticated design discipline. This evolution is characterized by the adoption of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a framework that has revolutionized both classic antibiotic discovery and contemporary bioproduction efforts. Where traditional antibiotic discovery in organisms like Streptomycetes often relied on observational methods and trial-and-error approaches, modern bioengineering leverages automated, iterative DBTL cycles to precisely optimize microbial strains for producing valuable compounds, from biofuels to pharmaceuticals [10] [11]. This shift has been enabled by technological advancements in genetic editing, automation, and data science, allowing researchers to systematically convert cellular factories into efficient producers of target molecules.

The DBTL cycle provides a structured framework for metabolic engineering experiments. In the Design phase, biological systems are conceptualized and modeled. The Build phase implements these designs in biological systems through genetic construction. The Test phase characterizes the performance of built strains, and the Learn phase analyzes data to inform the next design iteration [12]. This cyclic process has become the cornerstone of modern synthetic biology, enabling continuous improvement of microbial strains through successive iterations [9].

The DBTL Cycle: Core Components and Workflow

The DBTL cycle represents a systematic framework for metabolic engineering that has largely replaced the traditional, linear approaches to strain development. Each phase contributes uniquely to the iterative optimization process:

Design: This initial phase employs computational tools to select pathways and enzymes, design DNA parts, and create combinatorial libraries. Tools like RetroPath and Selenzyme facilitate automated enzyme selection, while PartsGenie designs reusable DNA components with optimized ribosome-binding sites and coding regions. Designs are statistically reduced using design of experiments (DoE) to create tractable libraries for laboratory construction [9].

Build: Implementation begins with commercial DNA synthesis, followed by automated pathway assembly using techniques like ligase cycling reaction (LCR) on robotics platforms. After transformation into microbial hosts, quality control is performed via automated purification, restriction digest, and sequence verification. This phase benefits from standardization through repositories like the Inventory of Composable Elements (ICE) [10] [9].

Test: Constructs are introduced into production chassis and evaluated using automated cultivation protocols. Target products and intermediates are detected through quantitative screening methods, typically ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). Data extraction and processing are automated through custom computational scripts [9].

Learn: This crucial phase identifies relationships between design factors and production outcomes using statistical methods and machine learning. The insights generated inform the next Design phase, creating a continuous improvement loop. Modern implementations often employ tools like the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART), which leverages machine learning to provide predictive models and recommendations for subsequent experimental designs [10].

Automated DBTL Workflow Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the information flow and key components in an automated DBTL pipeline:

Classic Antibiotic Discovery in Streptomycetes

Historical Significance and Workflow

Streptomycetes represent a historically significant platform for antibiotic production, having driven the golden age of antibiotics in the 1950s and 1960s. These Gram-positive bacteria are producers of a wide range of specialized metabolites with medicinal and industrial importance, including antibiotics, antifungals, and pesticides [11]. Traditional discovery approaches involved:

- Screening Natural Isolates: Researchers screened thousands of Streptomyces isolates from soil samples for antimicrobial activity.

- Mutation and Selection: Random mutagenesis using chemicals or UV radiation followed by screening for improved producers.

- Medium Optimization: Empirical testing of various carbon and nitrogen sources to enhance titers.

- Process Scale-up: Laboratory findings were translated to fermentation processes with minimal mechanistic understanding.

Despite the success of these approaches in producing first-generation antibiotics, technological advancements over the last two decades have revealed that only a fraction of the biosynthetic potential of Streptomycetes has been exploited [11]. Given the urgent need for new antibiotics due to the antimicrobial resistance crisis, there is renewed interest in applying engineering approaches like the DBTL cycle to explore and engineer this untapped potential.

DBTL Cycle Application to Streptomycetes

The contemporary application of the DBTL cycle to Streptomycetes engineering involves specialized approaches tailored to these actinobacteria:

- Design: Bioinformatics tools identify novel biosynthetic gene clusters and predict their functions. Pathway refactoring optimizes gene arrangement for heterologous expression.

- Build: Advanced genetic tools like CRISPR-Cas9 enable precise genome editing. Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) allows simultaneous modification of multiple genomic locations.

- Test: Analytical platforms (LC-MS/MS) characterize metabolite production and identify novel compounds. Cultivation platforms optimize production conditions.

- Learn: Multi-omics integration (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) reveals regulatory networks and metabolic bottlenecks.

This systematic approach has significantly accelerated the discovery and production of novel specialized metabolites from Streptomycetes, addressing the critical need for new antibiotics [11].

Contemporary Bioproduction: Automated DBTL Pipelines

Integrated Workflow Implementation

Modern biofoundries have implemented highly automated DBTL pipelines that significantly accelerate strain development cycles. These integrated systems demonstrate the power of contemporary bioproduction approaches:

Full Automation Integration: The pipeline runs from in silico selection of candidate enzymes through automated parts design, statistically guided pathway assembly, rapid testing, and rationalized redesign [9]. This integrated approach provides an iterative DBTL cycle underpinned by computational and laboratory automation.

Modular Design: The pipeline is constructed in a modular fashion, allowing laboratories to replace individual components while preserving overall principles and processes. This flexibility enables technology adoption as methods advance [9].

Compression of Design Space: Combinatorial design approaches generating thousands of possible configurations are reduced to tractable numbers using statistical methods like orthogonal arrays combined with Latin squares. This achieves compression ratios of 162:1 (2592 to 16 constructs), making comprehensive exploration feasible [9].

Case Study: Flavonoid Production in E. coli

The application of an automated DBTL pipeline to (2S)-pinocembrin production in E. coli demonstrates the efficiency of contemporary approaches:

- Initial Library Design: 2592 possible configurations were designed varying vector copy number, promoter strength, and gene order [9].

- DoE Reduction: Statistical reduction yielded 16 representative constructs [9].

- Production Range: Initial pinocembrin titers ranged from 0.002 to 0.14 mg L⁻¹ [9].

- Key Findings: Vector copy number had the strongest significant effect on production, followed by chalcone isomerase promoter strength [9].

- Second Cycle Optimization: Incorporating learnings from the first cycle improved production by 500-fold, achieving competitive titers up to 88 mg L⁻¹ [9].

This case study illustrates how iterative DBTL cycling with automation at every stage enables rapid pathway optimization, compressing development timelines that traditionally required years into weeks or months.

Quantitative Comparison of DBTL Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Applications

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of DBTL Applications in Metabolic Engineering

| Application | Host Organism | Target Compound | Production Improvement | Key Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoid Production | E. coli | (2S)-pinocembrin | 500-fold increase (to 88 mg L⁻¹) | Vector copy number, CHI promoter strength | [9] |

| Dopamine Production | E. coli | Dopamine | 2.6-6.6-fold improvement (69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L) | RBS engineering, GC content in SD sequence | [13] |

| Isoprenol Production | E. coli | Isoprenol | 23% improvement predicted | Machine learning recommendations from multi-omics | [10] |

Methodological Comparison

Table 2: Methodological Approaches in DBTL Implementation

| Methodological Aspect | Classic Approach | Contemporary Approach | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Methodology | Manual design based on literature | Automated computational tools (RetroPath, Selenzyme) | Comprehensive exploration, reduced bias |

| Build Technique | Manual cloning, restriction enzyme-based | Automated LCR assembly, robotics platform | Higher throughput, reduced human error |

| Test Capacity | Low-throughput analytics | UPLC-MS/MS with automated sample processing | Higher data quality, more replicates |

| Learn Mechanism | Empirical correlation | Machine learning (ART), statistical DoE | Predictive power, pattern recognition |

| Cycle Duration | Months to years | Weeks to months | Accelerated optimization |

Enabling Technologies and Methodologies

Computational and Analytical Tools

The implementation of effective DBTL cycles relies on sophisticated computational infrastructure and analytical tools:

Machine Learning Integration: ML methods like gradient boosting and random forest have demonstrated superior performance in the low-data regime common in early DBTL cycles. These methods show robustness to training set biases and experimental noise [14]. Automated recommendation algorithms leverage ML predictions to propose new strain designs, with studies showing that large initial DBTL cycles are favorable when the number of strains to be built is limited [14].

Multi-omics Data Integration: Tools like the Experiment Data Depot (EDD) serve as open-source repositories for experimental data and metadata. When combined with the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) and Jupyter Notebooks, researchers can effectively store, visualize, and leverage synthetic biology data to enable predictive bioengineering [10].

Data Visualization: Advanced visualization techniques like GEM-Vis enable the dynamic representation of time-course metabolomic data within metabolic network maps. These visualization approaches allow researchers to observe metabolic state changes over time, facilitating new insights into network dynamics [15]. Effective visualization strategies are particularly crucial for interpreting complex untargeted metabolomics data throughout the analytical workflow [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions in DBTL Workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Type | Function in DBTL Workflow | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Medium | Defined carbon source, salts, trace elements | Controlled cultivation conditions | Dopamine production in E. coli [13] |

| SOC Medium | Tryptone, yeast extract, salts, glucose | Recovery after transformation | Cloning steps in strain construction [13] |

| Phosphate Buffer | KH₂PO₄/K₂HPO₄ at pH 7 | Reaction environment for cell-free systems | In vitro testing in knowledge-driven DBTL [13] |

| Reaction Buffer | Phosphate buffer with FeCl₂, vitamin B6, substrates | Supporting enzymatic activity | Crude cell lysate systems for pathway testing [13] |

| Trace Element Solution | Fe, Zn, Mn, Cu, Co, Ca, Mg salts | Providing essential micronutrients | Supporting robust cell growth in production [13] |

Advanced DBTL Methodologies

Knowledge-Driven DBTL Framework

A recent innovation in DBTL methodology is the knowledge-driven approach that incorporates upstream in vitro investigation:

Mechanistic Understanding: This approach uses cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems and crude cell lysate systems to test enzyme expression levels and pathway functionality before implementing changes in living cells. This bypasses whole-cell constraints such as membranes and internal regulation [13].

RBS Engineering: Simplified ribosome binding site engineering modulates the Shine-Dalgarno sequence without interfering with secondary structures, enabling precise fine-tuning of relative gene expression in synthetic pathways [13].

Implementation Workflow: The knowledge-driven cycle begins with in vitro testing using crude cell lysate systems to assess different relative expression levels. Results are then translated to the in vivo environment through high-throughput RBS engineering, accelerating strain development [13].

This approach demonstrated its effectiveness in optimizing dopamine production in E. coli, where it achieved concentrations of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L, representing a 2.6-6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art production methods [13].

Multi-omics Integration and Visualization

The integration of multiple data types represents another significant advancement in DBTL capabilities:

Multi-omics Data Collection: Contemporary approaches leverage exponentially increasing volumes of multimodal data, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [10].

Synthetic Data Generation: Tools like the Omics Mock Generator (OMG) library produce biologically believable multi-omics data based on plausible metabolic assumptions. While not real, this synthetic data provides more realistic testing than randomly generated data, enabling rapid algorithm prototyping [10].

Dynamic Visualization: Methods like GEM-Vis create animated visualizations of time-course metabolomic data within metabolic network maps, using fill levels of nodes to represent metabolite amounts at each time point. These dynamic visualizations enable researchers to observe system behavior over time, facilitating new insights [15].

The relationship between data types, analytical methods, and visualization strategies can be represented as follows:

The evolution from classic antibiotic discovery to contemporary bioproduction represents a fundamental paradigm shift in metabolic engineering. The adoption of systematic DBTL cycles, enhanced by automation, machine learning, and multi-omics integration, has transformed the field from a trial-and-error discipline to a predictive engineering science. Where traditional approaches to antibiotic discovery in Streptomycetes relied on observational methods and empirical optimization, modern bioengineering leverages designed iterations with computational guidance to achieve precise metabolic outcomes.

This transition has profound implications for addressing contemporary challenges, from antimicrobial resistance to sustainable bioproduction. The continued refinement of DBTL methodologies—including knowledge-driven approaches, enhanced visualization techniques, and integrated biofoundries—promises to further accelerate the development of next-generation bacterial cell factories. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly expand the scope of accessible biological products and increase the efficiency of their production, ultimately strengthening the bioeconomy and addressing critical human needs.

Why Streptomycetes and E. coli are Prime Model Organisms for DBTL Applications

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework for accelerating microbial strain development in metabolic engineering. This iterative engineering paradigm involves designing genetic modifications, building engineered strains, testing their performance, and learning from the data to inform the next design cycle [1]. The DBTL framework has become central to synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, with automated biofoundries increasingly implementing these cycles to streamline development processes [3]. The power of the DBTL approach lies in its ability to continuously integrate experimental data to refine metabolic models and engineering strategies, thereby reducing the time and resources required to develop industrial-grade production strains.

This technical review examines why Escherichia coli and Streptomyces species have emerged as premier model organisms for implementing DBTL cycles in metabolic engineering. We analyze their complementary strengths, present experimental case studies, and provide detailed methodologies that demonstrate their utility in optimized bioproduction.

Escherichia coli as a DBTL Chassis

Physiological and Genetic Advantages

Escherichia coli possesses several inherent characteristics that make it exceptionally suitable for DBTL-based metabolic engineering. Its rapid growth rate (doubling times as short as 20 minutes), easy culture conditions, and metabolic plasticity enable quick iteration through DBTL cycles [17]. The wealth of biochemical and physiological knowledge accumulated over decades of research provides a strong foundation for rational design phases. Furthermore, E. coli's status as the best-characterized organism on Earth means researchers have access to an extensive collection of genetic tools and well-annotated genomic resources [17].

From a genetic manipulation perspective, E. coli exhibits high transformation efficiency and supports a wide variety of cloning vectors and engineering techniques. This genetic tractability significantly accelerates the "Build" phase of DBTL cycles. The availability of advanced techniques such as CRISPR-based genome editing, λ-Red recombineering, and MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) enables precise and rapid strain construction [17]. These attributes collectively make E. coli an ideal platform for high-throughput metabolic engineering approaches.

Case Study: Knowledge-Driven DBTL for Dopamine Production

A recent implementation of the knowledge-driven DBTL cycle in E. coli demonstrates the efficient optimization of dopamine production [3]. Researchers developed a highly efficient dopamine production strain capable of producing 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (equivalent to 34.34 ± 0.59 mg/g biomass), representing a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous state-of-the-art production systems [3].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics in E. coli DBTL Case Studies

| Product | Host Strain | Titer Achieved | Fold Improvement | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | E. coli FUS4.T2 | 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L | 2.6-6.6x | RBS engineering of hpaBC and ddc genes [3] |

| 1-Dodecanol | E. coli MG1655 | 0.83 g/L | >6x | Machine learning-guided protein profile optimization [18] |

| 2-Ketoisovalerate | E. coli W | 3.22 ± 0.07 g/L | N/A | Systems metabolic engineering with non-conventional substrate [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Knowledge-Driven DBTL with RBS Engineering

Design Phase: The dopamine pathway was designed to utilize L-tyrosine as a precursor, with conversion to L-DOPA catalyzed by the native E. coli 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) and subsequent decarboxylation to dopamine by L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) from Pseudomonas putida [3]. The key innovation was the upstream in vitro investigation using crude cell lysate systems to test different relative enzyme expression levels before in vivo implementation.

Build Phase: The engineering strategy employed high-throughput ribosome binding site (RBS) engineering to fine-tune the expression levels of hpaBC and ddc genes. The pET plasmid system served as a storage vector for heterologous genes, while the pJNTN plasmid was used for library construction. The production host E. coli FUS4.T2 was engineered for high L-tyrosine production through depletion of the transcriptional dual regulator TyrR and mutation of the feedback inhibition of chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase (tyrA) [3].

Test Phase: Strains were cultured in minimal medium containing 20 g/L glucose, 10% 2xTY medium, and appropriate supplements. Analytical methods quantified dopamine production and biomass formation, with high-throughput screening enabling rapid evaluation of multiple RBS variants [3].

Learn Phase: Data analysis revealed the impact of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on RBS strength, providing mechanistic insights that informed subsequent design iterations. This knowledge-driven approach minimized the number of DBTL cycles required to achieve significant production improvements [3].

Machine Learning Integration in DBTL Cycles

The integration of machine learning with DBTL cycles has significantly enhanced E. coli metabolic engineering. In a notable example, researchers implemented two DBTL cycles to optimize dodecanol production using 60 engineered E. coli MG1655 strains [18]. The first cycle modulated ribosome-binding sites and acyl-ACP/acyl-CoA reductase selection in a pathway operon containing thioesterase (UcFatB1), reductase variants (Maqu2507, Maqu2220, or Acr1), and acyl-CoA synthetase (FadD). Measurement of both dodecanol titers and pathway protein concentrations provided training data for machine learning algorithms, which then suggested optimized protein expression profiles for the second cycle [18]. This approach generated a 21% increase in dodecanol titer in the second cycle, reaching 0.83 g/L – more than 6-fold greater than previously reported batch values for minimal medium [18].

Streptomycetes as a DBTL Chassis

Physiological and Metabolic Specialization

Streptomyces species are Gram-positive bacteria renowned for their exceptional capacity to produce diverse secondary metabolites. These soil-dwelling bacteria possess complex genomes (8-10 MB with >70% GC content) encoding numerous biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) – approximately 36.5 per genome on average [20] [21]. Their natural physiological specialization for secondary metabolite production includes sophisticated regulatory networks, extensive precursor supply pathways, and specialized cellular machinery for compound secretion and self-resistance [21].

Streptomycetes exhibit a complex developmental cycle involving mycelial growth and sporulation, processes intrinsically linked to their secondary metabolism [21]. This inherent metabolic complexity provides a favorable cellular environment for the heterologous production of complex natural products, particularly large bioactive molecules such as polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides that often challenge other production hosts due to folding, solubility, or post-translational modification requirements [21].

Case Study: Systems Metabolic Engineering of Streptomyces Coelicolor

Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) have played a crucial role in advancing DBTL applications in Streptomycetes. The iterative development of S. coelicolor models – from iIB711 to iMA789, iMK1208, and the most recent iAA1259 – demonstrates how increasingly sophisticated computational tools enhance DBTL efficiency [22]. Each model iteration has incorporated expanded reaction networks, improved gene-protein-reaction relationships, and updated biomass composition data, leading to progressively more accurate predictive capabilities.

Table 2: Streptomyces DBTL Tools and Applications

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Examples | Function in DBTL Cycle | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tools | pIJ702, pSETGUS, pIJ12551 | Cloning and heterologous expression [20] [23] | |

| Computational Models | iAA1259 GSMM | Predicting metabolic fluxes and engineering targets [22] | |

| Automation Tools | ActinoMation (OT-2 platform) | High-throughput conjugation workflow [23] | |

| Database Resources | StreptomeDB | Natural product database for target identification [20] |

The iAA1259 model represents a significant advancement, incorporating multiple updated pathways including polysaccharide degradation, secondary metabolite biosynthesis (e.g., yCPK, gamma-butyrolactones), and oxidative phosphorylation reactions [22]. Model validation demonstrated substantially improved dynamic growth predictions, with iAA1259 achieving just 5.3% average absolute error compared to 37.6% with the previous iMK1208 model [22]. This enhanced predictive capability directly supports more effective Design phases in DBTL cycles.

Experimental Protocol: Automated Conjugation Workflow

A key limitation in Streptomyces DBTL cycles has been the laborious and slow transformation protocols. Recent work has addressed this bottleneck through automation with the ActinoMation platform, which implements a semi-automated medium-throughput workflow for introducing recombinant DNA into Streptomyces spp. using the open-source Opentrons OT-2 robotics platform [23].

The methodology involves:

- Strain Preparation: Preparation of donor E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 strains carrying the desired plasmid and recipient Streptomyces spores.

- Automated Conjugation: The robotic platform performs the conjugation protocol, including mixing of donor and recipient cells, plating on appropriate media, and incubation.

- Selection and Analysis: Exconjugants are selected using appropriate antibiotics, with efficiency rates varying by strain and plasmid combination [23].

Validation across multiple Streptomyces species (S. coelicolor M1152 and M1146, S. albidoflavus J1047, and S. venezuelae DSM40230) demonstrated conjugation efficiencies ranging from 1.21×10⁻⁵ for S. albidoflavus with pSETGUS to 6.13×10⁻² for S. venezuelae with pIJ12551 [23]. This automated approach enables scalable DBTL implementation without sacrificing efficiency.

Comparative Analysis and Future Perspectives

Complementary Strengths in DBTL Applications

E. coli and Streptomycetes offer complementary advantages that make them suitable for different metabolic engineering applications within the DBTL framework:

E. coli excels in:

- Rapid DBTL iteration due to fast growth and well-established high-throughput tools

- Precise genetic control with extensive characterized parts (promoters, RBSs)

- Superior performance for products requiring precursors from central metabolism

- Advanced machine learning integration with rich historical data [3] [17] [18]

Streptomycetes excel in:

- Production of complex secondary metabolites requiring specialized tailoring enzymes

- Native capacity for antibiotic production and self-resistance

- Superior protein secretion capabilities benefiting downstream processing

- Natural enzymatic diversity for biotransformations [20] [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Applications

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Strains/Plasmids |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Production Strains | Metabolic engineering chassis | FUS4.T2 (high L-tyrosine), MG1655 (dodecanol production), W (2-KIV production) [3] [18] [19] |

| Streptomyces Production Strains | Heterologous expression hosts | S. coelicolor M1152/M1146, S. albidoflavus J1047, S. venezuelae DSM40230 [23] |

| Cloning Vectors (E. coli) | Genetic manipulation | pET system (gene storage), pJNTN (library construction) [3] |

| Cloning Vectors (Streptomyces) | Heterologous expression | pSETGUS, pIJ12551, pIJ702 [20] [23] |

| Database Resources | Design phase guidance | StreptomeDB (natural products), GSMM models (iAA1259) [20] [22] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The future of DBTL applications in both model organisms points toward increased integration of machine learning algorithms, automation, and multi-omics data integration. For E. coli, research focuses on expanding substrate utilization to non-conventional carbon sources [17] [19] and enhancing predictive models through deeper mechanistic understanding [1]. For Streptomycetes, efforts concentrate on developing more efficient genetic tools [21] [23] and leveraging genomic insights to unlock their extensive secondary metabolite potential [20] [22].

A particularly promising direction is the use of simulated DBTL cycles for benchmarking machine learning methods, as demonstrated in recent research showing that gradient boosting and random forest models outperform other methods in low-data regimes [1]. This approach enables optimization of DBTL strategies before costly experimental implementation, potentially accelerating strain development for both organism classes.

E. coli and Streptomycetes each occupy distinct but complementary niches as model organisms for DBTL applications in metabolic engineering. E. coli provides a streamlined platform for rapid iteration and high-throughput engineering, particularly valuable for products aligned with its central metabolism. Streptomycetes offer specialized capabilities for complex natural product synthesis, leveraging their native metabolic sophistication. The continued development of genetic tools, computational models, and automated workflows for both organisms will further enhance their utility in the DBTL framework, accelerating the development of microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction across diverse applications.

Visual Appendix: DBTL Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: The DBTL Cycle in Metabolic Engineering. This iterative framework forms the foundation for modern strain development, with each phase generating outputs that inform subsequent cycles.

Diagram 2: Comparative Strengths of E. coli and Streptomycetes as DBTL Chassis. Each organism offers specialized capabilities that make them suitable for different metabolic engineering applications.

Implementing the DBTL Cycle: Tools, Automation, and Real-World Applications

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a cornerstone framework in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, enabling the systematic development of microbial strains for chemical production [24]. Within this iterative process, the Design phase serves as the critical foundational stage where theoretical strategies and precise genetic blueprints are formulated before physical construction begins. This phase has been transformed by computational tools, allowing researchers to move from intuitive guesses to data-driven designs [25].

This technical guide examines the core components of the Design phase, focusing on computational methods for strain design and the subsequent translation of these designs into actionable DNA assembly protocols. We will explore the algorithms and software tools that predict effective genetic modifications, the standardization of genetic parts, and the detailed planning of assembly strategies that ensure successful transition to the Build phase [26]. The precision achieved during Design directly determines the efficiency of the entire DBTL cycle, reducing costly iterations and accelerating the development of high-performance production strains.

Computational Methods for Strain Design

Computational strain design leverages genome-scale metabolic models and sophisticated algorithms to predict genetic modifications that enhance the production of target compounds. These tools identify which gene deletions, additions, or regulatory changes will redirect metabolic flux toward desired products while maintaining cellular viability [25].

Key Computational Approaches and Tools

Table 1: Computational Tools for Metabolic Engineering Strain Design

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Methodology | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RetroPath [9] | Pathway discovery | Analyzes metabolic networks to identify novel biological routes to target chemicals | Automated enzyme selection for flavonoid production pathways in E. coli |

| Selenzyme [9] | Enzyme selection | Selects suitable enzymes for specified biochemical reactions | Selecting enzymes for (2S)-pinocembrin pathway from Arabidopsis thaliana and Streptomyces coelicolor |

| OptKnock [25] | Gene knockout identification | Uses constraint-based modeling to couple growth with product formation | Predicting gene deletions to overproduce metabolites in yeast |

| Protein MPNN [27] | Protein design | AI-driven protein sequence design for creating novel enzymes | Generating protein libraries for biofoundry services |

These tools address different aspects of the design challenge. Pathway design tools like RetroPath explore what compounds can be made biologically using native, heterologous, or enzymes with broad specificity [25] [9]. Strain optimization algorithms then determine the genetic modifications needed to improve production titers, yield, and productivity for the designed pathways. Recent advancements have focused on improving runtime performance to identify more complex metabolic engineering strategies and incorporating kinetic considerations to improve prediction accuracy [25].

Implementing Computational Designs

The transition from computational prediction to implementable design requires careful consideration of genetic context. The PartsGenie software facilitates this transition by designing reusable DNA parts with simultaneous optimization of bespoke ribosome-binding sites and enzyme coding regions [9]. These tools enable the creation of combinatorial libraries of pathway designs, which can be statistically reduced using Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies to manageable sizes for laboratory construction and screening [9].

For example, in a project aiming to produce the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in E. coli, researchers designed a combinatorial library covering 2,592 possible configurations varying vector copy number, promoter strengths, and gene orders. Through DoE, this was reduced to 16 representative constructs, achieving a 162:1 compression ratio while maintaining the ability to identify significant factors affecting production [9].

DNA Assembly Protocol Design

Once a strategic strain design has been established computationally, the focus shifts to designing the physical DNA assembly protocols that will bring the design to life. This process involves selecting appropriate assembly methods, designing genetic parts with correct specifications, and generating detailed experimental protocols.

DNA Assembly Methodologies

Table 2: Common DNA Assembly Methods in Metabolic Engineering

| Method | Key Feature | Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Gate Assembly [28] | Type IIS restriction enzyme-based | Modularity, one-pot reaction, standardization | Pathway construction, toolkit development (e.g., YaliCraft) |

| Gibson Assembly [29] | Isothermal assembly | Seamless, single-reaction, no sequence constraints | Plasmid construction, multi-fragment assembly |

| Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) [9] | Oligonucleotide assembly | High efficiency, error-free, customizable | Pathway library construction, automated workflows |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Integration [28] | Genome editing | Marker-free integration, chromosomal insertion | Direct genomic integration, multiplexed editing |

Modern metabolic engineering projects often employ hierarchical modular cloning systems that combine these methods. For instance, the YaliCraft toolkit for Yarrowia lipolytica employs Golden Gate assembly as its primary method, organized into seven individual modules that can be applied in different combinations to enable complex strain engineering operations [28]. The toolkit includes 147 plasmids and enables operations such as gene overexpression, gene disruption, promoter library screening, and easy redirection of integration events to different genomic loci.

Protocol Design Considerations

When designing DNA assembly protocols, several technical factors must be addressed:

- Restriction enzyme selection: For Golden Gate assembly, careful selection of Type IIS restriction enzymes is crucial to ensure compatibility and avoid internal cut sites [26].

- Homology arm design: For CRISPR/Cas9 integration, homology arms typically require 500-1000bp flanking sequences for efficient homologous recombination in yeast systems [28].

- Parts compatibility: Automated software tools can verify compatibility among DNA fragments, considering factors such as GC content, secondary structure, and repetitive elements [26].

- Inventory optimization: Advanced design platforms can optimize the use of existing lab inventory, reducing additional DNA synthesis orders and associated costs [26].