Systems Metabolic Engineering: Principles, Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems metabolic engineering, an interdisciplinary field that integrates systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering to optimize metabolic networks in cells.

Systems Metabolic Engineering: Principles, Applications, and Future Directions for Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems metabolic engineering, an interdisciplinary field that integrates systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering to optimize metabolic networks in cells. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from the core functions of metabolism to the engineering of novel pathways. The content explores advanced methodological tools for network reconstruction and analysis, tackles troubleshooting and optimization strategies for overcoming production bottlenecks, and examines validation techniques and comparative analyses that demonstrate real-world success in producing pharmaceuticals and high-value chemicals. The review concludes by synthesizing key takeaways and highlighting the transformative potential of emerging trends, including AI-integrated models and cell-free systems, for advancing biomedical and clinical research.

The Foundations of Systems Metabolic Engineering: From Core Metabolism to Engineered Cell Factories

Defining Metabolic Engineering and Its Evolution into a Systems-Scale Discipline

Metabolic engineering is a specialized field at the intersection of biology and chemistry that emerged in the 1990s, dedicated to the purposeful modification and optimization of metabolic pathways within living organisms [1]. The core principle involves using genetic engineering tools to redesign existing biochemical pathways or design novel pathways that do not exist in nature, enabling enhanced production of desired compounds [2] [1]. This discipline has transformed microorganisms into efficient biocatalysts for the production of secondary metabolites that serve as resources for industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fuels [2].

The fundamental tasks of metabolic engineering include improving productivity and yield of specific pathways, expanding substrate range, eliminating waste products, enhancing process performance, and broadening the array of products that can be biologically synthesized [1]. By altering nutrient flow, reducing cellular energy consumption, or minimizing waste production, metabolic engineers can optimize cellular factories for industrial applications [1]. The field has gained significant importance in providing sustainable alternatives to traditional chemical synthesis, particularly for biofuel and pharmaceutical production [3] [1].

The Evolution of Metabolic Engineering

From Traditional to Systems Metabolic Engineering

Traditional metabolic engineering initially focused on manipulating a handful of genes and pathways based on known literature information and rational thinking [4]. Early strategies typically involved overexpressing rate-limiting enzymes in biosynthetic pathways, inhibiting competing metabolic pathways, expressing heterologous genes, and engineering enzymes for improved function [5]. While these approaches achieved notable successes, they were often limited by their piecemeal nature and inability to account for the complex, interconnected nature of cellular metabolism [2].

The field evolved significantly with advances in omics technologies, computational bioscience, and systems biology, which provided unprecedented global views of cellular metabolism and physiology [4]. This transformation gave rise to systems metabolic engineering, which incorporates concepts and techniques from systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering into the metabolic engineering framework [2] [6]. This integrated approach enables system-level analysis and engineering of microorganisms, offering a powerful framework for developing superior microbial cell factories [2] [7].

Table: Evolution of Metabolic Engineering Approaches

| Era | Key Characteristics | Primary Tools | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Metabolic Engineering (1990s) | Manipulation of individual genes and pathways; Rational, intuitive approaches based on known literature | Gene knockout/knockin; Plasmid-based expression; Classical strain development | Piecemeal approach; Limited by incomplete knowledge of cellular networks; Unable to account for complex regulation |

| Systems Metabolic Engineering (2000s-present) | Holistic, system-wide analysis and engineering; Integration of multiple disciplines | Omics technologies; Genome-scale models; Synthetic biology; Evolutionary engineering | Computational complexity; Requirement for high-throughput data; Integration of multiple data types |

Key Technological Drivers

Several technological advances propelled the transition to systems metabolic engineering. The development of high-throughput omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, fluxomics) provided comprehensive data on cellular components and their interactions [2] [7]. Genome-scale metabolic models emerged as powerful computational tools for simulating and predicting cellular behavior under different genetic and environmental conditions [2]. The rise of synthetic biology provided tools for creating novel biological parts, modules, and systems, enabling more precise control over metabolic pathways [7]. Additionally, evolutionary engineering strategies allowed for simultaneous optimization of multiple genes through adaptive laboratory evolution [8] [7].

Principles of Systems Metabolic Engineering

Conceptual Framework

Systems metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from local pathway optimization to global cellular network engineering. It employs a holistic approach that considers the complex interactions between metabolic pathways, gene regulation, protein-protein interactions, and signal transduction networks [2] [4]. This integrated perspective enables identification of non-obvious genetic targets and regulatory bottlenecks that would be missed when focusing solely on the primary biosynthetic pathway of interest.

The framework synergistically combines three core approaches: increased understanding of cellular systems through systems biology, creation of novel biological systems through synthetic biology, and adaptation of cellular systems through evolutionary engineering [7]. This integration allows metabolic engineers to address challenges that were previously intractable using traditional methods alone.

Key Methodological Components

Systems Biology Approaches

Systems biology provides the analytical foundation for systems metabolic engineering through several key methodologies:

Omics Integration: Combined analysis of transcriptome, metabolome, and fluxome data provides comprehensive insights into different phases of cell growth and product formation [6]. For instance, such integrated analysis has been applied to Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-lysine production, revealing critical regulatory nodes [6].

In Silico Simulation and Modeling: Genome-scale metabolic models enable flux response analysis and prediction of metabolic consequences of genetic modifications [6] [7]. Tools like OptKnock and OptForce employ bilevel programming to identify gene knockout strategies that couple cellular growth with product formation [7].

Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA): This mathematical framework helps quantify how control of metabolic flux is distributed among various enzymes in a pathway, identifying rate-limiting steps and potential engineering targets [2].

Synthetic Biology Tools

Synthetic biology provides the constructive elements for systems metabolic engineering:

Pathway Engineering: Design and construction of novel metabolic pathways for production of non-native or unnatural chemicals [7]. This includes de novo biosynthetic pathways that can convert existing cellular metabolites into desired products [7].

Genetic Circuit Design: Implementation of synthetic regulatory circuits for fine-tuning gene expression, dynamic pathway control, and implementation of Boolean logic operations in response to environmental signals [7].

CRISPR-Cas Systems: Precision genome editing tools that enable efficient gene knockouts, knockins, and regulatory element engineering [8] [3]. These systems have been successfully implemented in various production hosts including E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and K. marxianus [8].

Evolutionary Engineering Strategies

Evolutionary engineering complements rational design through empirical optimization:

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Long-term cultivation of microorganisms under selective pressure to improve desired phenotypes such as product tolerance, substrate utilization, or overall productivity [8] [7]. For example, ALE of engineered K. marxianus for lactic acid production resulted in an 18% increase in titer, reaching 120 g/L [8].

Biosensor-Based Selection: Employment of metabolite-responsive genetic circuits coupled with selectable markers to enable high-throughput screening of improved producers [6]. An L-valine responsive sensor based on Lrp in C. glutamicum increased titers by 25% while reducing byproducts [6].

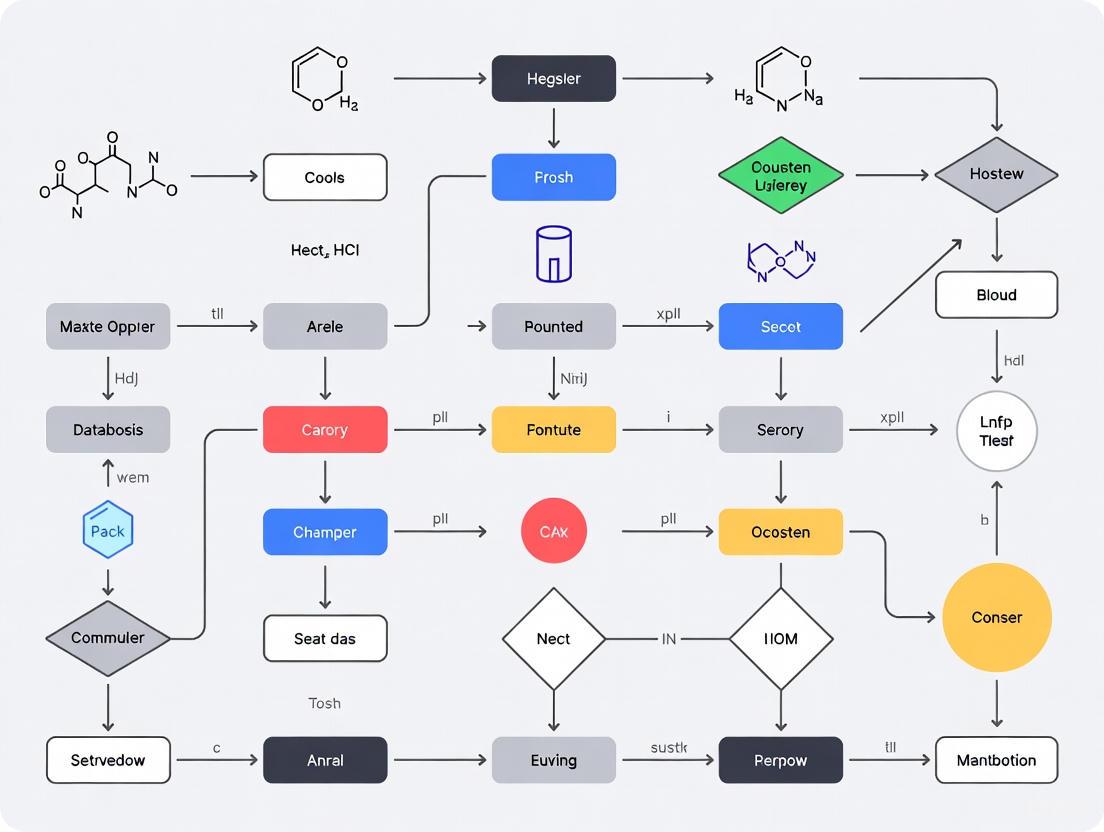

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of systems metabolic engineering, showing how these components interact in the design-build-test-learn cycle:

Applications and Products

Pharmaceutical Production

Metabolic engineering has made significant contributions to pharmaceutical production, particularly for complex natural products that are difficult to synthesize chemically or extract efficiently from natural sources [1]. Key successes include:

Taxol Production: The anticancer drug Taxol, originally isolated from Pacific yew bark, has been produced through metabolic engineering of isoprenoid pathways in microorganisms [1]. This approach addresses supply limitations of plant extraction.

Alkaloid Biosynthesis: Complex plant alkaloids such as morphine have been synthesized from amino acids through engineered pathways in E. coli and S. cerevisiae [1].

Isoprenoid Derivatives: Various isoprenoids including carotenoids and plant-derived terpenes have been successfully produced using engineered microorganisms [1]. S. cerevisiae serves as an effective cell factory for isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Biofuels and Sustainable Chemicals

The production of biofuels and renewable chemicals represents a major application area for systems metabolic engineering:

Next-Generation Biofuels: Engineering of microorganisms like bacteria, yeast, and algae for enhanced processing of lignocellulosic biomass into advanced biofuels [3]. Notable achievements include 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency from lipids and a 3-fold increase in butanol yield in engineered Clostridium species [3].

Lactic Acid and Bioplastics: Engineering of Kluyveromyces marxianus for lactic acid production reaching titers of 120 g/L with a yield of 0.81 g/g [8]. Lactic acid serves as the monomer for polylactic acid (PLA), a promising bioplastic.

Amino Acid Production: Systems metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli for industrial production of amino acids including L-lysine (over 2.2 million tons annual production) and L-glutamate [6].

Table: Representative Products of Systems Metabolic Engineering

| Product Category | Specific Products | Host Organism | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | Taxol, Alkaloids, Isoprenoids | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Production of complex plant-derived drugs in microorganisms |

| Amino Acids | L-Lysine, L-Glutamate, L-Threonine | C. glutamicum, E. coli | Annual production of >2.2 million tons of L-lysine |

| Biofuels | Biodiesel, Butanol, Ethanol | Clostridium spp., S. cerevisiae | 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency; 3x butanol yield improvement |

| Bioplastics Precursors | Lactic Acid, Succinic Acid | K. marxianus, E. coli | 120 g/L lactic acid titer; 0.81 g/g yield |

Experimental Protocols in Systems Metabolic Engineering

Pathway-Focused Engineering

Pathway-focused approaches aim to increase product yield through targeted modifications to specific metabolic routes:

Carbon Source Utilization Engineering: Replacement of phosphotransferase system (PTS) with non-PTS transport to conserve phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) for product synthesis [6]. For example, combined overexpression of iolT1 or iolT2 with ppgK in C. glutamicum improved PEP supply for L-lysine production [6].

Precursor Enrichment and Byproduct Elimination: Enhancement of key enzyme expression to maximize precursor availability while eliminating competing pathways [6]. In C. glutamicum, deletion of thrB and mcbR combined with plasmid-based expression of homm-lysCm increased precursor supply for L-methionine production [6].

Transporter Engineering: Modification of export systems to enhance product secretion and reduce feedback inhibition [6]. Overexpression of brnFE and deletion of brnQ in C. glutamicum increased production of branched-chain amino acids and L-methionine [6].

CRISPR-Cas Mediated Strain Engineering

The following protocol outlines CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing in Kluyveromyces marxianus as described in recent literature [8]:

Materials:

- pUCC001 CRISPR plasmid (contains hygromycin-resistance marker)

- Donor DNA template (90 bp oligonucleotides with homology to flanking regions)

- K. marxianus host strain

- Transformation reagents: 50% PEG 3350, 1M lithium acetate, single-stranded carrier DNA

- Selection media with hygromycin

Procedure:

- Design guide RNA sequences targeting specific genomic loci

- Amplify donor DNA template using Phusion polymerase

- Grow K. marxianus overnight in YPD medium at 30°C

- Subculture in fresh 2x YPAD medium for 3.5-4 hours

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with sterile water

- Prepare transformation mix containing PEG, lithium acetate, carrier DNA, CRISPR plasmid (400 ng), and donor DNA (4-6 μg)

- Incubate cells with transformation mix

- Plate on selective media containing hygromycin

- Verify genetic modifications by Sanger sequencing

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) protocols optimize strains through serial passaging under selective pressure [8]:

Procedure:

- Start with an engineered production strain (e.g., LA-producing K. marxianus)

- Maintain cultures in production medium under selective conditions (e.g., low pH, high product concentration)

- Perform serial transfers to fresh medium at regular intervals (e.g., 24-48 hours)

- Monitor population performance metrics (growth rate, product titer, yield)

- Isolate improved clones from endpoint populations

- Sequence genomes of evolved clones to identify causal mutations

- Reverse-engineer beneficial mutations into parent strain to confirm causality

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Kluyveromyces marxianus | Platform organisms for metabolic engineering; Well-characterized genetics and established tools |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems (e.g., pUCC001 plasmid), Donor DNA templates, Homology-directed repair systems | Precision genome editing; Gene knockout/knockin; Regulatory element engineering |

| Expression Components | Codon-optimized genes, Constitutive and inducible promoters, Terminators, Plasmid vectors | Heterologous gene expression; Pathway engineering; Fine-tuning metabolic flux |

| Analytical Tools | RNA-seq kits, LC-MS/MS systems, GC-MS systems, NMR spectroscopy, Metabolic flux analysis software | Omics data generation; Metabolic profiling; Flux quantification |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes (hygromycin, kanamycin), Auxotrophic markers (URA3, LEU2) | Selection of successfully engineered strains; Maintenance of genetic constructs |

| Culture Media Components | Defined minimal media, Carbon sources (glucose, xylose, glycerol), Nitrogen sources, Inducers (IPTG, galactose) | Controlled cultivation conditions; Substrate utilization studies; Induction of pathway expression |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, systems metabolic engineering faces several challenges. Economic feasibility remains a hurdle for many bio-based products competing with petroleum-derived alternatives [3]. Technical bottlenecks include the efficient utilization of mixed substrates, particularly lignocellulosic hydrolysates, and managing cellular stress responses under industrial conditions [8] [3]. Regulatory hurdles and public acceptance of genetically modified organisms also present challenges for commercial implementation [3].

Future directions include leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning for enzyme and pathway discovery, strain optimization, and predictive modeling [2] [3]. Expanding the range of non-food feedstocks, particularly waste streams and one-carbon substrates, will enhance sustainability [3]. Development of modular co-culture systems where different specialists perform distinct metabolic steps represents another promising avenue [7]. As the field advances, metabolic engineering is poised to play an increasingly central role in the transition to a sustainable bio-based economy.

Systems metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in the design of microbial cell factories, integrating systems biology, biotechnology, and synthetic biology to optimize microorganisms for the bio-based production of chemicals, materials, and fuels [9]. This discipline moves beyond traditional single-gene approaches to consider the metabolic network as an interconnected whole, enabling the global analysis and engineering of microorganisms at unprecedented efficiency and versatility. The core principles of pathway identification, genetic manipulation, and flux analysis form the foundational pillars of this approach, allowing researchers to rationally engineer strains with superior production capabilities [9]. By combining in silico and experimental strategies, systems metabolic engineering provides a powerful framework for addressing the complexity of cellular metabolism and identifying effective genetic engineering targets that couple cellular objectives with desired product formation [10] [11].

The industrial relevance of these principles is well-established in biotechnology. For instance, Corynebacterium glutamicum is used to produce over two million tons of amino acids annually, while filamentous fungi like Aspergillus niger are widely exploited for industrial enzyme production [10]. The success of these production strains often requires a combination of multiple genetic targets, necessitating sophisticated approaches to navigate the complex metabolic networks [10]. This technical guide examines the core methodologies driving advances in systems metabolic engineering, with particular focus on their application in strain optimization for biotechnological production.

Pathway Identification Methodologies

Pathway identification constitutes a critical first step in metabolic engineering, enabling researchers to map the biochemical routes from substrates to products within microbial cell factories. Several computational approaches have been developed to elucidate these pathways, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Elementary Flux Mode Analysis

Elementary flux mode (EFM) analysis is a fundamental approach for decomposing complex metabolic networks into unique, non-decomposable biochemical pathways [10]. Each EFM represents a minimal set of enzymes that can operate at steady state, with the entire set of EFMs defining the metabolic capabilities of an organism. The computation of EFMs relies on stoichiometric balancing and thermodynamic feasibility constraints [10].

The mathematical foundation for EFM analysis begins with the mass balance equation: S ∙ r = 0 where S is the stoichiometric matrix with dimensions m × q (m = number of metabolites, q = number of reactions), and r is a q × 1 flux vector [10]. This equation must satisfy the thermodynamic constraint for all irreversible reactions: rᵢ ≥ 0.

Algorithms for computing EFMs, such as the double description method with recursive enumeration and bit pattern trees, enable the systematic investigation of all possible physiological states without a priori knowledge of measured fluxes [10]. The relative flux (νᵢ,ⱼ) for each reaction i in elementary mode j, normalized to substrate uptake flux, can be calculated as follows, where ξ represents the molar carbon content in c-mol per mol:

$$ \nu_{i,j} = \frac{r_{i,j}}{r_{substrate,j}} \times \frac{\xi_{substrate}}{\xi_{hexose}} $$

This normalization facilitates comparison across different carbon sources by referencing fluxes to a hexose unit [10].

Metabolic Building Blocks and m-DAGs

MetaDAG represents a more recent approach that constructs metabolic networks as reaction graphs, then transforms them into metabolic directed acyclic graphs (m-DAGs) by collapsing strongly connected components into single nodes called metabolic building blocks (MBBs) [12]. This methodology significantly reduces network complexity while maintaining connectivity information, enabling efficient analysis of large-scale metabolic networks.

The MetaDAG tool automates metabolic network reconstruction using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database identifiers, allowing users to generate networks for individual organisms, groups of organisms, specific reactions, enzymes, or KEGG Orthology identifiers [12]. The tool computes both the reaction graph (where nodes represent reactions and edges represent metabolite flow) and the simplified m-DAG, where edges between MBBs indicate at least one pair of connected reactions in the original graph [12].

Pathway Enumeration for Engineering Applications

Pathway enumeration techniques serve not only for mapping metabolic capabilities but also for identifying potential engineering targets. For instance, elementary mode analysis enabled the identification of acetate and propionate activation pathways in C. glutamicum, revealing both the primary acetate kinase-phosphotransacetylase (AK-PTA) pathway and a redundant CoA transferase system (Cg2840) that operates when glucose is present as a co-substrate [13]. This comprehensive pathway identification provides the foundation for targeted genetic manipulations aimed at optimizing strain performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Identification Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Outputs | Applications | Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elementary Flux Mode Analysis | Decomposes network into minimal biochemical pathways | Complete set of independent metabolic pathways; Theoretical yields | Identification of all possible metabolic states; Gene deletion strategy prediction | null space approach [10] |

| m-DAG Construction | Collapses strongly connected components into metabolic building blocks | Simplified directed acyclic graph of metabolic network | Large-scale network comparison; Taxonomy classification; Diet analysis | MetaDAG [12] |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Linear programming to optimize objective function | Optimal flux distribution for given objective | Prediction of wild-type flux distributions; Growth phenotype prediction | OptKnock, OptGene [11] |

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Metabolic flux analysis (MFA) quantifies the actual flow of metabolites through metabolic networks, providing critical insights for pathway engineering. The integration of flux measurements with other omics data and computational modeling has become a cornerstone of systems metabolic engineering.

Flux Correlation Analysis

Flux correlation analysis identifies potential genetic targets by calculating the correlation between the flux through an objective reaction (e.g., product formation) and fluxes through all other reactions in the network [10]. This approach, termed Flux Design, computes a target potential coefficient (αᵢ,ₒbⱼ) for each reaction i relative to the objective reaction obj:

αᵢ,ₒbⱼ = (νᵢ ± βᵢ,ₒbⱼ) / νₒbⱼ

where βᵢ,ₒbⱼ represents the intercept [10]. The calculation is performed using the covariance of νₒbⱼ and νᵢ divided by the square of the standard deviation of νₒbⱼ:

$$ \alpha_{i,obj} = \frac{cov(\nu_{obj}, \nu_i)}{\delta^2(\nu_{obj})} $$

Positive αᵢ,ₒbⱼ values indicate amplification targets, while negative values suggest deletion or attenuation targets [10]. Statistical validation is crucial, with a cutoff of r² = 0.7 for the regression coefficient and t-test verification (TS > t(f,P)) ensuring significance [10].

Structural Flux Analysis

Structural flux (StruF) represents an innovative approach that bridges pathway enumeration and objective function-centered methods [11]. Derived from the concept of control effective flux (CEF), structural fluxes incorporate biological objectives while accounting for all optimal and sub-optimal routes in a metabolic network.

The efficiency (ε) of each elementary mode i is defined as the ratio of the mode's output (typically growth or ATP production) to the investment required (sum of absolute flux values in the mode) [11]:

εᵢ = e / (∑|νⱼ|)

The structural flux for each reaction k is then calculated as a weighted average across all elementary modes:

StruFₖ = (∑ᵢ εᵢ × νₖ,ᵢ) / (∑ᵢ εᵢ)

This formulation enables the prediction of flux distributions that respect biological objectives while considering the full range of metabolic capabilities [11]. The iStruF algorithm leverages this concept to identify gene deletion strategies that increase the structural flux of a desired product by evaluating mutants without recomputing elementary modes for each perturbation [11].

Experimental Flux Validation

¹³C-labeling experiments provide critical experimental validation for computational flux predictions [13]. In C. glutamicum studies, these experiments confirmed that the carbon skeleton of acetate is conserved during activation to acetyl-CoA via the alternative CoA transferase pathway when the AK-PTA pathway is absent [13]. Metabolic flux analysis during growth on acetate-glucose mixtures revealed that elimination of the AK-PTA pathway increased carbon fluxes through glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and anaplerosis, while decreasing flux through the glyoxylate cycle [13].

Table 2: Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Methodological Basis | Data Requirements | Key Outputs | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis | ¹³C isotope labeling and mass distribution measurements | ¹³C-labeled substrates; Mass spectrometry or NMR data | In vivo intracellular flux maps; Pathway activities | Experimental intensity; Cost of labeled substrates |

| Flux Correlation Analysis | Statistical correlation of fluxes across elementary modes | Stoichiometric model; Elementary modes | Amplification and deletion targets; Quantitative target potential | Depends on quality of elementary mode computation |

| Structural Flux Analysis | Weighted average of fluxes from elementary modes based on efficiency | Stoichiometric model; Elementary modes; Biological objective | Biologically relevant flux predictions; Gene deletion targets | Computational intensity for large networks |

Genetic Manipulation Strategies

Genetic manipulation constitutes the implementation phase of metabolic engineering, where identified targets are modified to redirect metabolic fluxes toward desired products.

Gene Deletion Strategies

Gene deletion remains a fundamental approach for eliminating competing pathways and redirecting metabolic fluxes. OptKnock represents one of the first model-based frameworks for identifying gene deletion strategies, using a bi-level optimization approach to find reaction deletions that maximize product formation while maintaining cellular growth [11]. Subsequent algorithms like OptGene expanded this approach to accommodate non-linear objective functions and larger networks [11].

The iStruF algorithm introduces a pathway-centric approach to gene deletion, identifying targets that increase the structural flux of desired products by considering both optimal and sub-optimal metabolic routes [11]. This method demonstrated particular value for improving ethanol and succinate production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, identifying non-intuitive deletion targets that would be missed by optimality-focused approaches alone [11].

Gene Amplification Strategies

Amplification of rate-limiting enzymes represents a complementary approach to gene deletion. Flux correlation analysis enables the systematic identification of amplification targets by detecting reactions with fluxes positively correlated to the desired product flux [10]. In C. glutamicum for lysine production, this approach successfully identified known successful metabolic engineering strategies and provided insights into the flexibility of energy metabolism [10].

DNA microarray experiments can further support target identification by detecting constitutively highly expressed genes. For example, in C. glutamicum, microarray analysis identified cg2840 as a highly expressed CoA transferase gene, which was subsequently confirmed through enzyme purification and activity assays to function in acetate and propionate activation [13].

Comprehensive Pathway Engineering

Successful metabolic engineering often requires combined deletion and amplification strategies. Studies in C. glutamicum demonstrated that strains lacking both the CoA transferase and AK-PTA pathways lost the ability to activate acetate or propionate regardless of glucose presence, confirming that these systems provide redundant activation mechanisms when short-chain fatty acids are co-metabolized with other carbon sources [13]. This comprehensive understanding enables strategic rewiring of metabolic networks for enhanced production.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Pathway Identification Protocol

Objective: Identify all potential metabolic pathways for target compound production in microbial systems.

Methodology:

- Network Compilation: Reconstruct metabolic network from KEGG database using organism-specific identifiers [12]

- Elementary Mode Calculation: Apply double description method with recursive enumeration to compute elementary modes [10]

- Pathway Analysis: Calculate theoretical maximum yields for each elementary mode using the formula: Yᴘ/ᴄ,ⱼ = (∑ξᴘ × sᴘ) / (∑ξᴄ × sᴄ) where ξ is molar carbon content and s is stoichiometric coefficient [10]

- Target Identification: Perform flux correlation analysis with statistical validation (r² > 0.7, t-test significance) [10]

Expected Output: Prioritized list of pathway options with theoretical yields and identified genetic targets.

Metabolic Flux Analysis Protocol

Objective: Quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes under specific growth conditions.

Methodology:

- ¹³C-Labeling Experiment: Grow cells on specifically ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-¹³C]glucose) [13]

- Mass Isotopomer Measurement: Analyze labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites using GC-MS or LC-MS

- Flux Calculation: Apply computational fitting to determine flux distribution that best matches measured labeling patterns

- Validation: Compare experimental fluxes with predicted structural fluxes to assess biological relevance [11]

Expected Output: Quantitative intracellular flux map identifying key branch points and rate-limiting steps.

Genetic Manipulation Validation Protocol

Objective: Implement and validate genetic modifications for metabolic engineering.

Methodology:

- Strain Construction:

- For gene deletions: Use homologous recombination to replace target genes with selection markers [13]

- For gene amplifications: Implement plasmid-based expression or promoter engineering

- Phenotypic Characterization:

- Measure growth rates on various carbon sources

- Quantify substrate consumption and product formation rates

- Enzyme Activity Assays:

- Purify His-tagged enzymes (e.g., Cg2840 CoA transferase) [13]

- Measure specific activity with different substrates (e.g., acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, succinyl-CoA)

- Flux Analysis: Conduct ¹³C-labeling experiments to quantify flux changes in engineered strains [13]

Expected Output: Functionally characterized strain with verified metabolic alterations.

Visualization of Metabolic Engineering Workflows

Metabolic Pathway Analysis Diagram

Flux Analysis Integration Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates | Tracing metabolic fluxes via isotopic labeling | ¹³C metabolic flux analysis; Pathway validation | Position-specific labeling provides different flux information |

| His-Tag Purification Systems | Protein purification for enzyme activity assays | Characterization of CoA transferase activity (Cg2840) [13] | Enables rapid purification of functional enzymes |

| DNA Microarray Kits | Genome-wide expression analysis | Identification of constitutively highly expressed genes [13] | Provides complementary data to flux analyses |

| Homologous Recombination Systems | Targeted gene deletion or insertion | Creation of AK-PTA pathway knockout strains [13] | Essential for precise genetic modifications |

| GC-MS/LS-MS Instrumentation | Analysis of metabolite concentrations and labeling patterns | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions | High sensitivity required for intracellular metabolites |

| KEGG Database Access | Metabolic network reconstruction and pathway analysis | Retrieval of organism-specific metabolic networks [12] | Curated content essential for accurate model building |

| MetaDAG Tool | Metabolic network analysis and visualization | Construction of reaction graphs and m-DAGs [12] | Web-based interface simplifies complex analysis |

The integration of pathway identification, genetic manipulation, and flux analysis represents the core of modern systems metabolic engineering. By combining computational approaches like elementary mode analysis, flux correlation, and structural flux calculation with experimental validation through ¹³C-labeling and enzymatic assays, researchers can systematically identify and implement metabolic engineering targets. These methodologies have proven successful in optimizing industrial workhorses like C. glutamicum and A. niger for amino acid and enzyme production [13] [10].

Future advances will likely focus on enhancing the scalability of pathway enumeration methods, improving the integration of multi-omics data, and developing more sophisticated algorithms that better predict cellular behavior following genetic perturbations. As these core principles continue to evolve, they will further enable the rational design of microbial cell factories for sustainable bio-based production of chemicals, materials, and fuels, representing a key technology for global green growth [9].

The Central Role of Metabolism in Cellular Functions and Bioprocessing

Metabolism constitutes the complete set of life-sustaining chemical transformations that occur within living organisms, enabling cells to extract energy from nutrients, build essential cellular components, and eliminate waste products [14]. These biochemical processes follow the fundamental laws of thermodynamics, where energy transforms from one state to another but is neither created nor destroyed, with each reaction increasing overall entropy in the universe [14]. At the cellular level, metabolism unfolds through three primary stages: first, complex molecules are broken down into simpler units through digestion; second, these simpler molecules undergo incomplete oxidation; and third, the resulting compounds enter central metabolic pathways like the Krebs cycle for complete oxidation and energy extraction [14].

The chemical carrier of energy throughout these processes is adenosine triphosphate (ATP), synthesized primarily within mitochondria through the electron transport chain [14]. Metabolism is conventionally divided into two complementary branches: catabolism, which breaks down organic matter to harvest energy through cellular respiration, and anabolism, which utilizes this energy to construct complex cellular components like proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. The intricate balance between these processes maintains cellular homeostasis, with imbalances leading to pathological states ranging from obesity to cachexia [14].

Metabolic Pathways and Their Interconnectivity

Carbohydrate Metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism centers primarily on glucose processing, which begins immediately upon cellular uptake with conversion to glucose-6-phosphate—a charged molecule that cannot exit the cell [14]. This critical first step is catalyzed by hexokinase in the liver and pancreas, and glucokinase in other tissues. Glucose-6-phosphate serves as a key metabolic intermediate accessible to multiple pathways, including glycolysis for energy production and glycogenesis for storage [14]. Cells store carbohydrates as glycogen granules, with the liver capable of storing approximately 100g to maintain blood glucose stability, and skeletal muscle storing up to 350g to fuel muscle contraction [14].

Through glycolysis, all cells convert glucose to pyruvate in an anaerobic process that generates 2 molecules each of pyruvate, NADH, and ATP [14]. Pyruvate fate depends on cellular conditions: mitochondrial transport for acetyl-CoA production, cytosolic conversion to lactate, or utilization in gluconeogenesis via alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The pentose phosphate pathway represents another glucose-6-phosphate fate, generating nucleotides, certain lipids, and maintaining glutathione in its reduced form under regulation by glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [14]. Carbohydrate metabolism is hormonally regulated, with insulin stimulating glycolysis and glycogenesis, while catecholamines, glucagon, cortisol, and growth hormone promote gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis [14].

Lipid Metabolism

Lipids serve as energy-dense molecules that represent the principal energy source for mammalian tissues, though their insolubility requires specialized transport systems and they cannot be utilized anaerobically [14]. Following intestinal absorption as micelles, enterocytes break down fats into free fatty acids and glycerol for reassembly into triglycerides, which bind with proteins to form chylomicrons for transport to the liver via the portal vein system [14]. The liver processes these complex molecules and secretes very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) to transport endogenous lipids to peripheral tissues expressing hormone-sensitive lipase and lipoprotein lipase.

This enzyme progressively reduces VLDL to low-density lipoprotein (LDL), which is enriched with cholesterol and engulfed by target tissues—a process termed "forward cholesterol metabolism" [14]. When excess lipids accumulate in peripheral tissues, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) facilitates "reverse cholesterol metabolism" by transporting cholesterol to the biliary system for excretion [14]. Insulin serves as the primary regulator of lipid metabolism, stimulating lipases while simultaneously suppressing lipolysis throughout the organism [14].

Amino Acid Metabolism

Humans typically consume approximately 100g of protein daily, with the body maintaining about 10kg of protein that undergoes continuous turnover at a rate of roughly 300g per day [14]. Amino acids, the structural units of proteins, are categorized as essential (obtained solely from diet) or non-essential (synthesized by the body). Following enterocyte absorption, amino acid metabolism generates ammonium—a neurotoxic compound detoxified primarily through the hepatic urea cycle [14].

Amino acid processing occurs through two principal chemical reactions: transamination mediated by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and deamination catalyzed by glutamate dehydrogenase [14]. After deamination, the carbon skeletons yield seven metabolic intermediates: alpha-ketoglutarate, oxaloacetate, succinyl-CoA, fumarate, pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and acetoacetyl-CoA [14]. The first five contain three or more carbons and can feed into gluconeogenesis, while the latter two with only two carbons are directed toward lipid synthesis. Unlike other metabolic pathways, amino acid metabolism is regulated primarily by cortisol and thyroid hormone rather than insulin [14].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Pathways and Their Functions

| Metabolic Pathway | Primary Substrates | Key Products | Cellular Location | Regulatory Hormones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | Glucose | Pyruvate, ATP, NADH | Cytosol | Insulin (stimulates), Glucagon (inhibits) |

| Krebs Cycle (TCA) | Acetyl-CoA | ATP, NADH, FADH₂, CO₂ | Mitochondrial Matrix | Calcium, ATP, ADP, NAD+ |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway | Glucose-6-phosphate | NADPH, Ribose-5-phosphate | Cytosol | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Beta-Oxidation | Fatty Acids | Acetyl-CoA, NADH, FADH₂ | Mitochondrial Matrix | Insulin (inhibits), Glucagon (stimulates) |

| Urea Cycle | Ammonia, CO₂ | Urea | Mitochondria & Cytosol | N-Acetylglutamate |

Figure 1: Integrated Metabolic Network Showing Convergence of Major Pathways

Metabolism in Bioprocessing and Industrial Applications

Metabolomics for Bioprocess Optimization

Bioprocessing harnesses living cells to produce desired compounds across diverse sectors including biotherapeutics, food ingredients, agricultural products, and cosmetics [15]. Central to bioprocess optimization is the precise manipulation of cellular metabolism to ensure efficient target molecule production with consistent quality while minimizing waste byproducts and maximizing final yields [15]. Metabolomics has emerged as a powerful tool for bioprocess monitoring by providing real-time snapshots of cellular metabolism, enabling engineers to develop more robust and reproducible manufacturing processes [15].

Global, untargeted metabolomic profiling delivers comprehensive understanding beyond conventional methodologies, revealing underlying causes of metabolic bottlenecks and intrinsic connections between cellular physiological requirements and peak performance [15]. For instance, simply adding depleted amino acids to culture media may not improve performance if those amino acids are catabolized through alternative pathways rather than utilized for proliferation or protein production [15]. Metabolomics interrogates amino acid, lipid, nucleotide, carbohydrate, and vitamin/co-factor metabolic pathways and their interconnectivity, generating insights into redox balance, mitochondrial efficiency, antioxidant capacity, energetics, endoplasmic reticulum stress, lipid metabolism, and glycosylation patterns [15].

Applications Across Industries

Metabolomics applications span multiple bioprocessing sectors with demonstrated success in biologic manufacturing (monoclonal antibodies), beverage fermentation (beer, wine), biochemical production (biofuels), gene therapy vectors (CAR-T vectors), vaccine development, and therapeutic stem cell expansion [15]. These applications benefit from metabolomics integration throughout the bioprocessing workflow, including process development (culture method selection, scale-up, tech transfer), process optimization (media optimization, root-cause analysis), process characterization (clone/cell-line selection, strain engineering), and process monitoring (interventional strategy development, performance/quality prediction) [15].

Several studies have elegantly demonstrated metabolomics value in biological manufacturing. For example, multiomics research by Biogen, Inc. elucidated the critical importance of cysteine feed concentration in maintaining cellular viability, preserving redox balance, mitigating ER stress, and supporting mitochondrial homeostasis [15]. By employing metabolomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, researchers identified bioprocess monitoring biomarkers and revealed new targets for genetic engineering approaches, ultimately improving cell growth, viability, titer, specific productivity, and monoclonal antibody glycosylation [15].

Table 2: Metabolomics Applications in Bioprocessing Industries

| Industry Sector | Key Application | Measured Outcomes | Reference Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopharmaceuticals | Monoclonal antibody production | Improved cell growth, viability, titer, specific productivity, glycosylation | [15] |

| Biofuels & Biochemicals | Butanol production from Clostridium cellulovorans | Significantly increased butanol production via metabolic engineering | [15] |

| Beverage Production | Beer and wine fermentation | Optimization of fermentation conditions and yeast performance | [15] |

| Gene Therapy & Vaccines | CAR-T vector and vaccine development | Enhanced vector production and vaccine antigen yield | [15] |

| Stem Cell Therapeutics | Therapeutic stem cell expansion | Improved expansion protocols and cell quality | [15] |

Systems Metabolic Engineering Principles

Foundational Concepts

Systems metabolic engineering represents an advanced framework that integrates systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering with traditional metabolic engineering approaches to develop microbial cell factories for bio-based production of chemicals, materials, and fuels from renewable resources [9]. This discipline has evolved from designs targeting handfuls of genes with close metabolic network relationships to increasingly complex engineering requiring modification of dozens of genes spanning diverse metabolic functions including transporters, pathway enzymes, and tolerance genes [16].

Modern metabolic engineering follows iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles that link pathway design algorithms with active machine learning, next-generation DNA synthesis and assembly with genome engineering, and laboratory automation with ultra-high throughput genomics methods [16]. The three fundamental pillars of metabolic engineering are titer, yield, and rate (TYR), which serve as benchmarks for evaluating cost-competitiveness of engineered cell factories [16]. Through engineering heterologous pathways and optimizing endogenous metabolism, metabolic engineers now manufacture diverse products including commodity chemicals, novel materials, sustainable fuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable feedstocks [16].

Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Strategies

Static metabolic engineering approaches involving gene knockouts, promoter replacements, and heterologous gene introductions have achieved significant success but face limitations in managing trade-offs between growth and production [17]. Dynamic metabolic engineering has emerged as an advanced strategy that allows rebalancing of metabolic fluxes according to changing cellular conditions or fermentation stages [17]. This approach enables better management of essential genes whose complete knockout would be lethal but whose transient control could redirect carbon flux toward desired products [17].

Implementation typically employs genetic circuits that sense metabolic states and respond by modulating pathway enzyme expression [17]. For example, researchers have engineered E. coli strains to sense acetyl-phosphate buildup—an indicator of excess metabolic capacity—and respond by expressing phosphoenolpyruvate synthase (pps) and isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase (idi) only when excess glycolytic flux occurs [17]. This dynamic control strategy improved lycopene yields by 18-fold over constitutive expression strains while maintaining growth profiles comparable to host controls [17]. Similar approaches have demonstrated success using controlled protein degradation systems and genetic toggle switches to dynamically regulate essential enzymes like glucokinase, citrate synthase, and FabB [17].

Figure 2: Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) Cycle in Modern Metabolic Engineering

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Approaches

Quantitative Metabolomics and Flux Analysis

Advanced metabolomics methodologies enable precise quantification of metabolic states and fluxes. The Quantitative Metabolism and Imaging Core at UT Southwestern exemplifies sophisticated approaches, offering expertise in targeted metabolomics, tracer methodologies, and metabolic flux analysis [18]. Their services include quantification of intermediary metabolites and cofactors—organic acids (lactate, pyruvate, TCA cycle intermediates), amino acids, acylcarnitines (C2-C18), and nucleotides/short-chain acyl-CoAs (AMP, ADP, ATP, NAD+, NADH, acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA)—typically using GC/MS or LC/MS/MS platforms [18].

Tracer analysis represents a more advanced approach where researchers administer isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., ¹³C-glucose) and track incorporation patterns to elucidate metabolic pathway activities [18]. Methodologies include tracer-enhanced metabolomics for semiquantitative pathway insight, whole-body metabolite turnover studies to measure appearance and disposal rates, deuterated water approaches to assess biosynthetic rates, and comprehensive metabolic flux analysis using carbon-13 isotopomer distributions [18]. The recent development of spatial quantitative metabolomics using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) with ¹³C-labeled yeast extracts as internal standards enables quantification of over 200 metabolic features while maintaining spatial resolution in tissues [19]. This approach has revealed previously unappreciated metabolic remodeling in histologically unaffected brain regions following stroke, demonstrating superior performance compared to traditional normalization methods like total ion count or root mean square approaches [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering and Metabolomics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | ¹³C-glucose, ¹⁵N-glutamine, Deuterated water (²H₂O) | Track metabolic fluxes through specific pathways | Metabolic flux analysis, biosynthesis rates, pathway tracing |

| Internal Standards | U-¹³C-labeled yeast extract, ¹³C-labeled amino acids | Normalization and quantification in mass spectrometry | Quantitative metabolomics, spatial metabolomics normalization |

| Mass Spectrometry Matrices | N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDC) | Facilitate analyte desorption/ionization | MALDI-MSI spatial metabolomics |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic metabolite standards (organic acids, amino acids, nucleotides) | Compound identification and quantification | Targeted metabolomics, method validation |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Specific pathway modulators | Manipulate metabolic flux experimentally | Pathway validation, metabolic control analysis |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Cysteine, specialized media components | Optimize culture conditions and product yields | Bioprocess optimization, media development |

Metabolism serves fundamental roles in cellular functions and industrial bioprocessing, with advanced understanding enabling remarkable capabilities in metabolic engineering and systems biotechnology. The integration of multiomics approaches—combining metabolomics with genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—delivers comprehensive insights into cellular activity, allowing researchers to fine-tune bioprocesses with unprecedented precision [15]. As metabolomics and systems metabolic engineering continue evolving, their importance in bioprocessing will undoubtedly expand, paving the way for more efficient, sustainable, and high-quality production across pharmaceutical, chemical, and energy sectors [15] [16].

Future advancements will likely focus on dynamic control strategies that automatically adjust metabolic fluxes in response to changing bioreactor conditions, further enhancing product yields while maintaining cellular viability [17]. The ongoing development of quantitative spatial metabolomics will illuminate metabolic heterogeneity within industrial bioreactors and biological systems, enabling more targeted engineering approaches [19]. Together, these technologies will continue transforming biological systems into efficient cell factories for sustainable manufacturing, supporting the global transition toward bio-based economies and addressing critical challenges in energy, materials, and medicine [9] [16].

Optimizing Gibbs Free Energy and Building Block Production

The optimization of Gibbs free energy represents a fundamental thermodynamic objective in systems metabolic engineering, directly influencing the efficiency and yield of microbial production for valuable chemicals and building blocks. Within living cells, Gibbs free energy determines the spontaneity of biochemical reactions, establishing the thermodynamic feasibility of both native and engineered metabolic pathways [20]. In contemporary bioproduction, where microbial cell factories are engineered to synthesize chemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources, thermodynamic constraints often limit maximum achievable yields [21]. The minimization of Gibbs free energy provides a critical framework for predicting equilibrium states in complex biochemical systems, enabling metabolic engineers to design pathways that favor desired products while minimizing energy losses and byproduct formation [22].

The field of metabolic engineering has evolved through three distinct waves of innovation, each bringing new capabilities for addressing thermodynamic challenges. The first wave established rational approaches to pathway analysis and flux optimization, while the second wave incorporated systems biology and genome-scale metabolic models. Currently, the third wave leverages synthetic biology tools to design, construct, and optimize complete metabolic pathways for both natural and non-inherent chemicals [21]. Throughout this evolution, thermodynamic principles have remained central to engineering efficient microbial cell factories, with Gibbs free energy minimization serving as a cornerstone for predicting and optimizing chemical production in biological systems [22].

Theoretical Framework: Gibbs Free Energy in Biological Systems

Fundamental Principles and Computational Approaches

The Gibbs free energy function enables prediction of spontaneous directionality for systems under constant temperature and pressure constraints that universally apply to living organisms [20]. In metabolic engineering contexts, this thermodynamic framework allows researchers to model and predict the behavior of complex biochemical networks, particularly when optimizing for production of specific building blocks. The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of a reaction determines its thermodynamic feasibility, with negative values indicating spontaneous reactions. For pathway engineering, this means thermodynamic profiling can identify potential bottlenecks where reactions may proceed too slowly or require additional energy input through cofactors like ATP.

Computational methods for Gibbs energy minimization have advanced significantly, with metaheuristic optimization algorithms now capable of solving highly nonlinear and non-convex free energy surfaces that characterize biological systems. Recent research demonstrates that hybrid optimization frameworks combining multiple algorithmic approaches can effectively find equilibrium points of reacting components under specified operational conditions [22]. For instance, the Levy flight-assisted hybrid Sine-Cosine Aquila optimizer has shown particular promise for solving chemical equilibrium problems through Gibbs free energy minimization, overcoming limitations of traditional optimization methods when dealing with complex biological systems [22].

Thermodynamic Constraints in Cellular Metabolism

Cellular metabolism faces inherent thermodynamic constraints that impact building block production. The energy conservation principle dictates that energy must be invested to drive non-spontaneous reactions, typically through coupling with energy-releasing reactions or input of external energy sources. In engineered systems, this often manifests as competition between growth-associated energy demands and production-oriented metabolic fluxes [23]. Understanding these constraints is essential for designing effective metabolic engineering strategies, as they ultimately determine the theoretical maximum yield of any target compound.

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Parameters in Metabolic Engineering

| Parameter | Symbol | Biological Significance | Engineering Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy Change | ΔG | Determines reaction spontaneity and direction | Identifies thermodynamic bottlenecks in pathways |

| Enthalpy Change | ΔH | Reflects heat release or absorption | Impacts cellular temperature regulation and energy balance |

| Entropy Change | ΔS | Measures system disorder | Influences protein folding and molecular interactions |

| Equilibrium Constant | Keq | Relates reactant and product concentrations at equilibrium | Predicts maximum theoretical yield under given conditions |

| ATP Coupling | ΔGATP | Energy currency of the cell | Determines energy requirements for non-spontaneous reactions |

Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Building Block Production

Hierarchical Engineering Approaches

Modern metabolic engineering employs hierarchical strategies that operate at multiple biological levels to optimize building block production. At the part level, engineering focuses on individual enzymes through directed evolution or rational design to improve catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, or stability [21]. The pathway level involves assembling multiple enzymes into coordinated sequences that efficiently convert substrates to desired products while minimizing energy losses and byproduct formation. At the network level, engineers modify regulatory interactions and flux distributions to redirect metabolic resources toward target compounds. Genome-level engineering employs CRISPR-Cas systems and other editing tools to make multiplex modifications that eliminate competing pathways or introduce non-native capabilities [3]. Finally, at the cell level, strategies focus on optimizing cellular physiology and resource allocation to maximize production performance in bioreactor environments [21].

The integration of synthetic biology has revolutionized these hierarchical approaches, enabling precise manipulation of metabolic pathways using standardized genetic elements. CRISPR-Cas systems allow for precise genome editing, while de novo pathway engineering enables production of advanced biofuels and building blocks such as butanol, isoprenoids, and jet fuel analogs that boast superior energy density and compatibility with existing infrastructure [3]. These tools have facilitated remarkable achievements, including a 3-fold increase in butanol yield in engineered Clostridium spp. and approximately 85% xylose-to-ethanol conversion in engineered S. cerevisiae [3].

Host-Aware Modeling and Resource Allocation

A critical advancement in metabolic engineering has been the development of host-aware modeling frameworks that explicitly capture competition for limited cellular resources [23]. These models recognize that engineered production pathways compete with host metabolism for both metabolic precursors and gene expression resources, creating inherent trade-offs between cell growth and product synthesis. Computational approaches using multiobjective optimization have revealed that maximal volumetric productivity and yield from batch cultures require careful balancing of host enzyme and production pathway expression levels [23].

The fundamental growth-synthesis trade-off represents a key challenge in metabolic engineering for building block production. Strains engineered for high product yield typically exhibit slow growth but fast synthesis rates, while strains optimized for productivity demonstrate moderate growth with balanced synthesis capabilities [23]. This creates a Pareto front of optimal designs where improvement in one objective necessitates compromise in another. For instance, engineering for maximum productivity requires an optimal sacrifice in growth rate (approximately 0.019 min-1 in one model system) to achieve the highest volumetric productivity [23]. This insight suggests traditional engineering strategies focused solely on maximizing cell growth may fail to identify strains with optimal culture-level performance.

Experimental Results and Quantitative Analysis

Performance Metrics for Building Block Production

Systematic evaluation of metabolic engineering strategies requires standardized performance metrics that enable comparison across different systems and conditions. The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent advances in building block production, highlighting the effectiveness of various metabolic engineering approaches.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Engineered Building Block Production

| Chemical | Host Organism | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Key Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid | C. glutamicum | 62.6 | 0.51 | - | Substrate engineering, Genome editing [21] |

| L-Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | 212 | 0.98 | - | Modular pathway engineering [21] |

| D-Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | 264 | 0.95 | - | Modular pathway engineering [21] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | 153.36 | - | 2.13 | Modular pathway engineering, High-throughput genome engineering [21] |

| Lysine | C. glutamicum | 223.4 | 0.68 | - | Cofactor engineering, Transporter engineering [21] |

| Butanol | Clostridium spp. | - | 3-fold increase | - | Metabolic engineering [3] |

| Biodiesel | Microalgae | - | 91% conversion | - | Lipid pathway engineering [3] |

Advanced Biofuel Production Case Studies

Biofuel production exemplifies the successful application of Gibbs energy optimization in metabolic engineering. Second-generation biofuels utilizing non-food lignocellulosic feedstocks demonstrate significantly improved sustainability profiles compared to first-generation alternatives [3]. The integration of synthetic biology tools has enabled development of fourth-generation biofuels that employ genetically modified microorganisms with enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and lipid accumulation capabilities [3]. These advances rely fundamentally on thermodynamic optimization to ensure efficient conversion of feedstocks to desired fuel molecules.

Notable achievements in biofuel production include engineered enzymatic systems for biomass deconstruction, with key enzymes such as cellulases, hemicellulases, and ligninases facilitating conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars [3]. Consolidated bioprocessing approaches further enhance efficiency by combining enzyme production, biomass hydrolysis, and sugar fermentation in a single step, reducing energy inputs and improving overall process economics. These advances highlight how thermodynamic principles applied at multiple scales can dramatically improve the efficiency of biological production systems.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Gibbs Free Energy Minimization Techniques

Computational optimization of Gibbs free energy in metabolic systems requires specialized approaches capable of handling highly nonlinear and nonconvex energy landscapes. The Levy flight-assisted hybrid Sine-Cosine Aquila optimizer (AQSCA) represents a recent advancement that addresses limitations of conventional optimization methods [22]. This hybrid algorithm integrates the nature-inspired Aquila Optimizer, which simulates eagle hunting behaviors, with the mathematical search equations of the Sine-Cosine Algorithm, creating a synergistic framework that enhances both global exploration and local exploitation capabilities.

The AQSCA methodology incorporates several innovative components: (1) Levy Flight distributions for generating random numbers that enable more efficient search space exploration; (2) Ikeda Map for producing chaotic random numbers that enhance population diversity; and (3) dynamically varying weight parameters that iteratively adjust to balance exploration and exploitation throughout the optimization process [22]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in solving chemical equilibrium problems through Gibbs free energy minimization, particularly for systems characterized by complex reaction networks and multiple phases.

Host-Aware Strain Optimization Protocol

Implementing host-aware metabolic engineering requires a systematic protocol for strain development that accounts for resource competition effects. The following workflow outlines key steps for designing production strains optimized for culture-level performance metrics:

The protocol begins with development of a mechanistic host-aware model that captures dynamics of cell growth, metabolism, host enzyme and ribosome biosynthesis, heterologous gene expression, and product synthesis [23]. This model is then augmented with expressions describing population growth, nutrient consumption, and production dynamics in batch culture. Multiobjective optimization methods are applied to identify optimal enzyme expression levels that maximize both volumetric productivity and product yield, revealing the fundamental trade-offs between these performance metrics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | Precision manipulation of metabolic pathways | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs [3] |

| Synthetic Biological Parts | Modular control of gene expression | Promoters, RBSs, terminators, plasmids [21] |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of metabolites and products | LC-MS/MS standards, NMR reference compounds |

| Enzyme Engineering Kits | Directed evolution and enzyme optimization | Error-prone PCR kits, DNA shuffling systems |

| Host-Aware Modeling Software | Computational strain design and optimization | COBRA toolbox, RAVEN, GECKO [23] |

| Fermentation Media Components | Support high-density cultivation and production | Defined media, nutrient feeds, induction agents |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

Emerging Trends and Integration of Advanced Technologies

The field of metabolic engineering for building block production is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends likely to shape future research directions. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with traditional metabolic engineering approaches shows particular promise for accelerating strain development and optimization [21]. AI-driven systems are already being employed to improve material formulations, predict optimal pathway configurations, and optimize manufacturing schedules, potentially reducing development timelines from years to months [24]. These approaches leverage large datasets from omics technologies to build predictive models that can guide engineering decisions without exhaustive experimental testing.

Another significant trend involves the development of multi-scale models that integrate molecular-level thermodynamic constraints with cellular, bioreactor, and process-level considerations [23]. These comprehensive modeling frameworks enable more accurate prediction of performance in industrial settings, reducing the scale-up challenges that often plague metabolic engineering projects. The incorporation of thermodynamic constraints into genome-scale metabolic models has been particularly valuable for predicting feasible metabolic flux distributions and identifying energy-efficient pathway alternatives [22].

Challenges and Limitations in Current Approaches

Despite significant advances, metabolic engineering for building block production still faces several fundamental challenges. Economic feasibility remains a concern, particularly for commodities competing with petroleum-derived products, as technical bottlenecks in yield, titer, and productivity continue to limit commercial viability [3]. The recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass presents particular challenges for second-generation biofuels and biochemicals, necessitating costly pretreatment steps and specialized enzyme cocktails [3]. Additionally, regulatory hurdles surrounding genetically modified organisms, especially for fourth-generation biofuels using engineered algae, create uncertainty and delay industrial implementation [3].

The inherent trade-offs between growth and production represent another fundamental challenge, as cells optimized for rapid growth typically achieve lower product yields, while high-yield strains often grow too slowly for economical production [23]. This has prompted interest in two-stage bioprocesses where cells first grow to high density before switching to production mode, often using genetic circuits that dynamically regulate metabolism. Advanced circuit designs that inhibit host metabolism to redirect resources toward product synthesis have shown particular promise for breaking the growth-production trade-off [23].

The optimization of Gibbs free energy and building block production through systems metabolic engineering represents a powerful approach for sustainable chemical manufacturing. By applying thermodynamic principles to guide pathway design and cellular engineering, researchers can develop microbial factories that efficiently convert renewable resources into valuable products. The integration of computational optimization methods, host-aware modeling frameworks, and advanced genetic tools has enabled significant advances in both fundamental understanding and practical applications.

Future progress will likely depend on continued development of multi-scale models that incorporate thermodynamic constraints, innovative genetic circuits that dynamically regulate metabolism, and machine learning approaches that accelerate the design-build-test cycle. As these technologies mature, metabolic engineering promises to play an increasingly important role in the transition toward a sustainable bioeconomy, reducing dependence on fossil resources while enabling production of complex molecules with precision and efficiency. The principles and methodologies outlined in this review provide a foundation for ongoing research in this rapidly evolving field.

Historical Context and the Convergence of Systems Biology with Metabolic Engineering

The field of metabolic engineering, which seeks to manipulate microbial metabolism for the efficient production of chemicals and materials, has been fundamentally transformed through integration with systems biology. This convergence has given rise to systems metabolic engineering, an interdisciplinary framework that leverages tools from systems biology, synthetic biology, and evolutionary engineering to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches [25]. Where traditional metabolic engineering often relied on sequential, single-gene modifications, the systems-level approach enables comprehensive analysis and engineering of biological systems across multiple scales, from enzymes to entire cells and bioreactors [26] [27]. This paradigm shift has accelerated the development of microbial cell factories for sustainable production of fuels, pharmaceuticals, and chemical precursors, enhancing both productivity and economic viability [28] [25]. The transition toward a holistic perspective represents a form of methodological antireductionism in biological research, focusing on emergent properties and system-level behaviors rather than isolated components [29].

The Evolution from Metabolic Engineering to Systems Metabolic Engineering

Limitations of Traditional Metabolic Engineering

Traditional metabolic engineering faced significant challenges in developing industrially competitive microbial strains. The approach primarily focused on modifying individual enzymatic steps or deleting competing pathways without comprehensive understanding of cellular network regulation. This often resulted in suboptimal performance due to unforeseen metabolic burdens, regulatory conflicts, and cellular stress responses [25]. The development process required substantial time, effort, and cost, with diminishing returns for complex metabolic traits involving multiple genes and regulatory elements. Furthermore, the inability to predict system-wide responses to genetic modifications frequently necessitated extensive trial-and-error experimentation, limiting the speed and efficiency of strain development.

The Emergence of Systems Biology

Systems biology emerged as a transformative approach at the beginning of the 21st century, evolving through three distinct phases of development [29]. The initial phase witnessed the transformation of molecular biology into systems molecular biology, incorporating high-throughput data generation and computational analysis. Prior to the second phase, applied general systems theory converged with nonlinear dynamics, enabling the formation of systems mathematical biology. The final phase integrated these disciplines for comprehensive biological data analysis, completing the formation of modern systems biology as a holistic research paradigm [29]. This progression represented a fundamental shift from reductionist perspectives to methodological antireductionism, emphasizing emergent properties and network behaviors that cannot be understood by studying individual components in isolation.

Conceptual Integration

The convergence of systems biology with metabolic engineering created a powerful framework for addressing complex biological engineering challenges. Systems metabolic engineering integrates multi-omics data analysis, mathematical modeling, and synthetic biology tools to optimize microbial cell factories systematically [27] [25]. This integration enables researchers to account for the inherent complexity of cellular systems, including multiscale, multirate, nonlinear, and uncertain dynamics that traditionally limited bioprocess performance [26]. The holistic perspective allows for simultaneous consideration of multiple engineering targets, regulatory networks, and system constraints, leading to more predictable and successful strain development outcomes.

Core Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Systems metabolic engineering employs a diverse toolkit of computational and experimental methods spanning multiple biological scales. The table below summarizes key methodological categories and their specific applications in advancing microbial cell factory development.

Table 1: Core Methodologies in Systems Metabolic Engineering

| Method Category | Specific Tools/Approaches | Primary Applications | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint-based Modeling | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Prediction of metabolic flux distributions, Identification of gene deletion targets | Addressing growth-production trade-offs, Designing stable microbial consortia [26] |

| Kinetic Modeling | Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis, Mechanistic Enzyme Kinetics | Capturing metabolite accumulation, Predicting dynamic metabolic behaviors | Identifying dynamic metabolic control strategies [26] |

| Multi-omics Integration | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Fluxomics, Metabolomics | Constructing and validating mathematical models, Understanding cellular regulation | Linking metabolic potential to catalytic capacity [26] |

| Synthetic Biology Tools | CRISPR-Cas systems, De novo pathway engineering, Promoter engineering | Precise genome editing, Pathway reconstruction, Regulatory circuit design | Production of advanced biofuels (butanol, isoprenoids, jet fuel analogs) [28] |

| Machine Learning & AI | Neural networks, Feature selection algorithms | Strain optimization, Model parameterization, Predictive biology | Enhanced model predictability, Guided strain design [26] |

Multi-omics Data Integration and Analysis

The rise of high-throughput experimental platforms has moved biotechnology into the domain of big data, with multi-omics playing a crucial role in constructing and validating mathematical models [26]. Each omics layer provides distinct insights into cellular physiology: genomics defines metabolic potential by identifying which enzymes can be synthesized; transcriptomics reveals regulatory mechanisms influencing enzyme expression; proteomics quantifies enzyme abundance; fluxomics measures metabolic flux distributions; and metabolomics determines intracellular metabolite concentrations [26]. The integration of these complementary data types enables comprehensive understanding of cellular states and provides the empirical foundation for computational model construction and validation.

Computational Modeling Frameworks

Constraint-based Modeling