Strategies for Enhancing Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency in Synthetic Pathways: From Protein Engineering to Industrial Applications

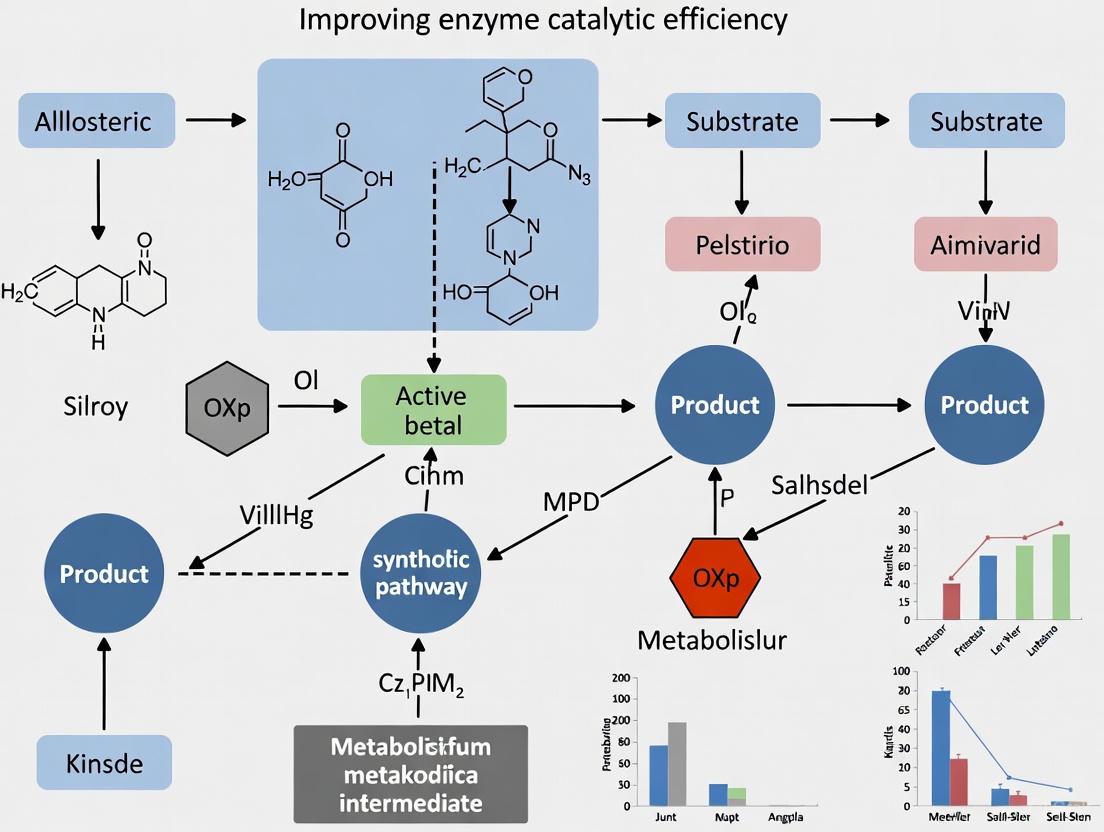

This comprehensive review explores multidisciplinary approaches for improving enzyme catalytic efficiency within synthetic pathways, a critical focus for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals.

Strategies for Enhancing Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency in Synthetic Pathways: From Protein Engineering to Industrial Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores multidisciplinary approaches for improving enzyme catalytic efficiency within synthetic pathways, a critical focus for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals. The article establishes foundational principles of enzyme catalysis and spatial organization, then details advanced methodologies including protein engineering, computational design, and multi-enzyme cascade systems. It provides practical troubleshooting frameworks for overcoming common optimization challenges and presents rigorous validation techniques through case studies of industrially implemented enzyme cascades for drug synthesis. By synthesizing recent advances in directed evolution, DNA scaffolding, kinetic modeling, and ecological assessment, this resource offers both theoretical insights and practical implementation strategies for developing efficient biocatalytic processes in pharmaceutical manufacturing and beyond.

Understanding Enzyme Catalysis: Principles and Spatial Organization in Synthetic Pathways

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Enzyme Catalysis and Efficiency Barriers

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Enzyme Efficiency Issues

FAQ: My enzyme reaction is proceeding too slowly. What could be the cause?

A slow reaction rate can result from several factors related to enzyme kinetics and reaction conditions. The table below summarizes common issues and their solutions.

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low reaction rate | Substrate concentration below KM | Measure initial rate at different [S]; plot on Michaelis-Menten graph [1] | Increase substrate concentration to saturating levels (>10x KM if known) [1] |

| Incomplete conversion | Unfavorable reaction equilibrium | Measure product concentration at equilibrium; compare to theoretical ΔG [2] | Remove product or couple to a secondary, favorable reaction [3] |

| No detectable activity | Incorrect reaction conditions (pH, buffer, temperature) | Test activity with a standard control substrate under recommended conditions [4] | Verify and adjust buffer, pH, and temperature to enzyme's optimum; check for essential cofactors [3] [4] |

| Gradual loss of activity | Enzyme instability or denaturation | Pre-incubate enzyme at reaction temperature for different times, then assay activity [4] | Add stabilizing agents (e.g., BSA, glycerol); ensure proper storage conditions; avoid freeze-thaw cycles [4] |

| Unexpected products | Enzyme purity issues or "star activity" | Analyze products via HPLC or gel electrophoresis; check for contaminating activities [4] | Use purer enzyme preparation; optimize buffer conditions to avoid high glycerol, extreme pH, or organic solvents [4] |

FAQ: My enzyme is producing unexpected products or shows altered specificity.

This problem, often related to "star activity" or the presence of inhibitors, frequently occurs under suboptimal conditions [4]. High glycerol concentration (>5% in the final reaction), an incorrect enzyme-to-DNA ratio, non-optimal pH, or the presence of organic solvents can induce off-target cleavage or activity [4]. To resolve this, ensure you are using the recommended assay buffer, avoid excessive enzyme concentrations, and eliminate potential contaminants like DMSO or ethanol from your reaction mix [4]. If working with DNA, be aware that methylation (e.g., DAM, DCM, or CpG methylation) can block specific recognition sites and alter the expected cleavage pattern [4].

Understanding Enzyme Kinetics and Catalytic Mechanisms

FAQ: What are the fundamental kinetic parameters I need to characterize my enzyme?

To fully characterize an enzyme's catalytic efficiency, you must determine its key kinetic parameters. These parameters are derived from the Michaelis-Menten model and provide insight into the enzyme's affinity for its substrate and its maximum catalytic rate [1]. The following table defines these critical constants.

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Experimental Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | Vmax | The maximum rate of reaction achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [1]. | Measured from the plateau of a Michaelis-Menten plot (rate vs. [S]) [1]. |

| Michaelis Constant | KM | The substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax. A lower KM often indicates higher substrate affinity [1]. | Determined from the substrate concentration at 1/2 Vmax on a Michaelis-Menten plot, or from the x-intercept of a Lineweaver-Burk plot [1]. |

| Turnover Number | kcat | The number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time when the enzyme is fully saturated [1]. | Calculated as kcat = Vmax / [Etotal]. |

| Catalytic Efficiency | kcat/KM | A measure of how efficiently an enzyme converts substrate to product at low substrate concentrations. The upper limit is diffusion-controlled (~10^8 to 10^9 M⁻¹s⁻¹) [1]. | Calculated from the determined values of kcat and KM. |

FAQ: What are the primary chemical mechanisms enzymes use to catalyze reactions?

Enzymes employ a combination of several well-established mechanisms to lower the activation energy of reactions and achieve tremendous rate enhancements, often over a million-fold [3] [5]. The major mechanisms include:

- Induced Fit and Substrate Orientation: The enzyme may undergo a conformational change upon substrate binding that brings the reactive groups into close proximity and optimal orientation, significantly increasing the "effective concentration" and the probability of a successful reaction [3] [6].

- Covalent Catalysis: A nucleophilic residue in the active site (e.g., serine, cysteine, or histidine) forms a transient covalent bond with the substrate, creating a more reactive intermediate. This is a key feature in serine proteases like chymotrypsin [3] [5].

- Acid-Base Catalysis: Specific amino acid side chains (e.g., histidine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid) act as general acids or bases by donating or accepting protons during the reaction, stabilizing charged transition states [5] [6]. The enzyme's environment can significantly alter the pKa of these residues to optimize their catalytic function [6].

- Electrostatic Catalysis and Transition State Stabilization: The active site provides an environment that stabilizes the high-energy transition state of the reaction far more effectively than it stabilizes the substrate itself. This can involve strategic placement of charged residues or metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺ in carboxypeptidase) to interact with developing charges in the transition state [3] [6]. This is considered a major contributor to catalytic power [6].

Diagram: Serine Protease Catalytic Mechanism

Experimental Protocols for Mechanistic Studies

Protocol 1: Determining Basic Kinetic Parameters (KM and Vmax)

This protocol outlines the steps for determining the Michaelis constant (KM) and the maximum velocity (Vmax) for an enzyme, which are fundamental for assessing its catalytic efficiency [1].

- Prepare Substrate Dilutions: Create a series of substrate solutions with concentrations spanning a range both above and below the suspected KM (e.g., from 0.2 to 5 times KM). Use at least 6-8 different concentrations.

- Initiate Reactions: In separate tubes, add a fixed, known amount of enzyme to each substrate solution to start the reaction. The volume of enzyme should be small relative to the total reaction volume to avoid dilution. Ensure all other conditions (pH, temperature, ionic strength) are constant and optimal.

- Measure Initial Rates: For each reaction, measure the initial velocity (v0) by quantifying the appearance of product or the disappearance of substrate over a short time period during which the reaction is linear (typically before 5-10% of the substrate has been consumed). Use a sensitive method appropriate for your product/substrate (e.g., spectrophotometry, fluorescence, HPLC).

- Plot and Analyze Data: Plot the initial velocity (v0) against the substrate concentration ([S]). Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 = (Vmax [S]) / (KM + [S])) using nonlinear regression software to obtain values for KM and Vmax. Alternatively, linearize the data using a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot.

Diagram: Kinetic Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Investigating Catalytic Residues via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis is a powerful method for probing the role of specific amino acids in enzyme catalysis [7]. This protocol describes a general approach for characterizing mutant enzymes.

- Target Selection: Based on structural data (e.g., X-ray crystallography) or sequence alignment with related enzymes, identify candidate catalytic residues (e.g., active site serines, histidines, aspartates). A common mutation is to replace a nucleophilic residue like serine or cysteine with alanine (e.g., S40A).

- Generate Mutant Enzymes: Use molecular biology techniques (e.g., PCR-based mutagenesis) to create plasmids encoding the desired mutant enzymes.

- Express and Purify: Express the wild-type and mutant enzymes in a suitable host system (e.g., E. coli) and purify them to homogeneity using affinity or ion-exchange chromatography.

- Characterize Kinetics: Determine the KM and kcat for the wild-type and mutant enzymes as described in Protocol 1. A dramatic decrease in kcat with little change in KM strongly suggests a direct role for the mutated residue in the chemical catalysis step, rather than in substrate binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and materials used in the study and optimization of enzyme catalysis, along with their critical functions in experimental workflows.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactors (e.g., NAD+, Metal Ions) | Small molecules or metal ions that are essential for the activity of many enzymes. They act as carriers of specific chemical groups or electrons [3]. | Identify required cofactors for your enzyme. Ensure they are added to the reaction buffer and are present at sufficient concentrations. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Used during enzyme extraction and purification to prevent proteolytic degradation of the target enzyme, thereby preserving activity. | Use a broad-spectrum cocktail. Consider the specificity of inhibitors relative to your enzyme's class. |

| Stabilizing Agents (Glycerol, BSA) | Added to enzyme storage buffers to prevent denaturation and maintain long-term stability. Glycerol prevents ice crystal formation [4]. | Keep final glycerol concentration in reactions <5% to avoid potential inhibition or "star activity" [4]. |

| Stopped-Flow Apparatus | A rapid-mixing instrument used to study the fast kinetics of enzymatic reactions on millisecond timescales, allowing observation of transient intermediates. | Essential for pre-steady-state kinetic analysis. Requires specialized equipment and relatively large amounts of purified enzyme. |

| Computational Tools (e.g., EzMechanism) | Automated tools that propose potential catalytic mechanisms for a given enzyme active site structure, helping to generate testable hypotheses [8]. | Useful in the initial stages of mechanistic studies. Proposed mechanisms must be validated experimentally [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using DNA-guided scaffolding to improve catalytic efficiency? The core principle is spatial organization. By co-localizing sequential enzymes in a metabolic pathway onto a synthetic DNA scaffold, the local concentration of enzymes and intermediates is increased. This mimics the substrate channeling observed in natural multi-enzyme complexes, reducing the diffusion of intermediates to the bulk solution, minimizing cross-talk with native pathways, and thereby accelerating the overall metabolic flux and improving product titers [9] [10].

Q2: What are the primary advantages of using DNA over other types of scaffolds, like RNA or proteins? DNA scaffolds offer distinct advantages of stability, robustness, and high configurability. Unlike RNA, which can be fragile, DNA is a stable molecule, making the scaffold more robust for long-term applications in living cells. Furthermore, DNA's predictable base-pairing rules and the ease of programming specific binding sites (e.g., for zinc fingers or TALEs) make it highly configurable for organizing various numbers and ratios of enzymes [9] [11] [10].

Q3: My product titer is lower than expected after implementing a DNA scaffold. What could be the issue? Low titers can result from several factors. You should troubleshoot the following:

- Scaffold Architecture: The order and stoichiometry of enzyme binding sites on the DNA scaffold must match the metabolic pathway's sequence. Verify that your scaffold design positions enzymes correctly [9].

- Binding Efficiency: Ensure your DNA-binding domains (e.g., zinc fingers, TALEs) are efficiently fused to your enzymes and have high specificity for their target sequences on the scaffold. Binding efficiency can be confirmed with methods like ChIP-PCR [10].

- Enzyme-Scaffold Ratio: An imbalance between the expressed enzymes and the available scaffold binding sites can lead to unbound enzymes and inefficient channeling. Optimize the expression levels of both components [9].

Q4: Can DNA-guided scaffolding be applied in prokaryotic systems like E. coli? Yes, DNA-guided scaffolding is highly effective in prokaryotic hosts like E. coli. In fact, a primary motivation for its development is to overcome the weak innate multi-enzyme co-localization mechanisms in prokaryotes, which often lead to low local concentrations of heterologous enzymes and substrates [10]. The original 2012 study and subsequent work have successfully demonstrated its application in E. coli [9] [11] [10].

Q5: Are there alternatives to Zinc-Finger proteins for anchoring enzymes to the DNA scaffold? Yes, Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) are a powerful alternative. TALEs are DNA-binding proteins that can be engineered to bind specific DNA sequences. A TALE-based DNA scaffold system has been successfully used to accelerate a heterologous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) biosynthesis system in E. coli, demonstrating its effectiveness as a scaffold system [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Product Yield Despite Scaffold Implementation

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Consistently low product titer across different scaffold designs. | Inefficient binding of enzyme-fusion proteins to the DNA scaffold. | Perform a split GFP assay. Co-express scaffold and enzymes fused to complementary halves of GFP; fluorescence recovery confirms proper complex assembly [10]. |

| The scaffold architecture does not optimize the metabolic pathway. | Rationally re-design the scaffold, varying the order and ratio of enzyme binding sites. Test these new architectures in vivo and measure catalytic output [9]. | |

| Titer decreases or cell growth is impaired. | Cellular toxicity from the heterologous expression of DNA-binding proteins and scaffolds. | Optimize cultivation conditions, particularly the induction temperature (e.g., 25°C). Use weaker inducible promoters to reduce the metabolic burden on the host chassis [10]. |

| One enzymatic step becomes a new bottleneck. | The kinetics of individual enzymes are not balanced after scaffolding. | Re-engineer the scaffold to increase the local concentration of the rate-limiting enzyme or use enzyme engineering to improve the specific activity of the slowest enzyme [12]. |

Issue: Verification of Scaffold Assembly In Vivo

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to confirm if enzymes are binding to the scaffold inside the cell. | Lack of a direct method to detect protein-DNA complex formation in vivo. | Perform Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Use an antibody against your DNA-binding domain (e.g., against a fused GFP tag) to pull down the protein complex, followed by PCR with primers specific to your DNA scaffold to confirm binding [10]. |

| Unclear if the spatial organization is functional. | Proximity between enzymes is not achieved. | Conduct a proximity-dependent labeling assay. Fuse enzymes to tags like HALO or SNAP that can covalently bind fluorescent ligands; colocalization via microscopy indicates successful clustering on the scaffold. |

Table 1: Documented Improvements in Metabolic Product Titers Using DNA-Guided Scaffolding.

| Metabolic Product | Host Organism | Scaffold System | Reported Improvement | Key Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resveratrol | E. coli | Zinc-Finger / Plasmid DNA | Titer increased as a function of scaffold architecture. | [9] |

| 1,2-Propanediol | E. coli | Zinc-Finger / Plasmid DNA | Titer increased as a function of scaffold architecture. | [9] |

| Mevalonate | E. coli | Zinc-Finger / Plasmid DNA | Titer increased as a function of scaffold architecture. | [9] |

| Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | E. coli | TALE / Plasmid DNA | System effectiveness validated via split-GFP; accelerated biosynthesis. | [10] |

Table 2: Comparison of DNA-Binding Domains for Scaffolding Applications.

| DNA-Binding Domain | Key Characteristics | Pros & Cons | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Finger (ZF) | Engineered modular proteins where each finger recognizes ~3 bp of DNA. | Pro: Well-established, configurable.Con: Design can be complex; context-dependent effects. | DNA-guided assembly in E. coli for resveratrol, 1,2-propanediol, and mevalonate pathways [9]. |

| Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) | Central repeat domain where each repeat recognizes a single DNA base; high specificity. | Pro: Simple design rules, high specificity, lower toxicity reported.Con: Large gene size can be challenging for cloning. | TALE-based scaffold for spatial organization of IAA biosynthetic enzymes in E. coli [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Zinc-Finger Based DNA Scaffold System

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing and testing a metabolic pathway assembled on a custom DNA scaffold using zinc-finger (ZF) domains, based on the foundational work by Conrado et al. [9].

A. Design and Assembly

- Select Target Enzymes: Identify the 2-4 sequential enzymes from your heterologous metabolic pathway to be scaffolded.

- Design DNA Scaffold Plasmid:

- Design a plasmid containing unique binding sites for each ZF domain. The order of sites should reflect the metabolic pathway sequence.

- The number of binding sites for each ZF can be varied to control the enzyme stoichiometry on the scaffold.

- Create Enzyme-ZF Fusions:

- Genetically fuse the coding sequence of each selected enzyme to a gene encoding a ZF domain that specifically binds one of the sites on the DNA scaffold.

- Cloning can be performed using standard methods (e.g., BioBrick assembly, Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate) [10].

B. Expression and Testing

- Co-transform: Co-transform the DNA scaffold plasmid and the plasmids carrying the enzyme-ZF fusions into your production host (e.g., E. coli).

- Induction and Cultivation: Induce expression of the enzyme-ZF fusions and the scaffold. The original study found that a cultivation temperature of 25°C can be optimal for proper folding and complex formation [10].

- Measure Output: Harvest cells and measure the titer of your target metabolic product using HPLC or GC-MS. Compare the titer against a control system with no scaffold or a scrambled scaffold.

Protocol 2: Verifying Scaffold Assembly via Split GFP Assay

This method provides a visual and quantitative confirmation that your scaffold is successfully bringing enzymes into close proximity in vivo [10].

- Construct Split GFP Components:

- Fuse one enzyme to the N-terminal fragment of GFP (GFP1-10).

- Fuse a second, adjacent enzyme to the C-terminal fragment of GFP (GFP11).

- Include the DNA scaffold with the appropriate binding sites for these fusions.

- Co-express in Host: Co-express all three components (two split-GFP fusions + scaffold) in your host cell.

- Measure Fluorescence: If the enzyme fusions are brought into close proximity by the scaffold, the GFP fragments will reconstitute, leading to fluorescence.

- Quantification: Measure the fluorescence intensity (Ex: 488 nm; Em: 538 nm) and normalize it to cell density (OD600). A significant increase in fluorescence compared to a no-scaffold control confirms successful complex assembly.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

DNA-Guided Scaffolding Workflow

This diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for designing, building, and testing a DNA-guided scaffold, from initial design to functional validation.

Enzyme Organization Concept

This diagram contrasts unorganized enzymes with a DNA-scaffolded system, highlighting the principle of substrate channeling that leads to improved efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Components for DNA-Guided Scaffolding Experiments.

| Item | Function & Description | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Domains | Engineered proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to anchor enzymes to the scaffold. | Zinc Finger (ZF) domains [9] [11] or Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) [10]. Choice depends on design simplicity and specificity requirements. |

| Scaffold Plasmid | A plasmid vector containing the engineered array of DNA binding sites. Acts as the physical scaffold. | A high-copy-number plasmid (e.g., pSB1C3 derivative) with a configurable multi-cloning site for inserting binding site arrays [10]. |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for expressing the enzyme-DNA-binding domain fusion proteins. | Vectors with inducible promoters (e.g., pET, pBAD) to control the timing and level of fusion protein expression. |

| Assembly Method | The cloning technique used to construct the scaffold and fusion plasmids. | BioBrick Standard Assembly [10], Golden Gate, or Gibson Assembly. Choice affects speed and modularity. |

| Production Host | The living chassis where the scaffolded pathway is implemented. | Escherichia coli (E. coli) is the most common and well-characterized host for these systems [9] [10]. |

| Validation Tools | Reagents and methods to confirm scaffold assembly in vivo. | Split GFP system [10] for proximity; Antibodies for ChIP (e.g., anti-GFP) [10] for binding confirmation. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Low Conversion Rates

Problem: Your enzyme catalyst is not achieving the expected substrate conversion.

| Common Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution | Relevant Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-optimal reaction conditions (pH, temperature) | Measure initial reaction rates across a pH (e.g., 5-9) and temperature (e.g., 20-70°C) gradient. | Adjust buffer system and incubation temperature to the identified optimum for your specific enzyme. | Protocol: Determining Optimal pH and Temperature 1. Prepare a series of buffered substrate solutions covering a pH range. 2. Incubate separate reaction mixtures with a fixed enzyme amount at each pH. 3. Repeat at a fixed optimal pH across a temperature gradient. 4. Measure initial reaction rates (e.g., product formation per unit time) to identify maxima [13]. |

| Enzyme instability under reaction conditions | Pre-incubate the enzyme at reaction temperature for different time intervals (0-60 min) before adding substrate and measuring residual activity. | Engineer enzyme for stability (e.g., directed evolution, immobilization on a solid support) or add stabilizing agents to the reaction mixture [14]. | |

| Mass transfer limitations (especially for immobilized enzymes) | Compare reaction rates using free enzyme versus immobilized enzyme at the same protein concentration. | Optimize support porosity, reduce particle size of the immobilization support, or increase agitation speed. | |

| Insufficient enzyme concentration | Perform experiments with increasing concentrations of enzyme while keeping substrate concentration constant. | Increase the amount of enzyme catalyst in the reaction mixture, ensuring it is proportional to the substrate load. | Protocol: Testing Enzyme Concentration Dependence 1. Prepare a series of reactions with a fixed, saturating substrate concentration. 2. Vary the enzyme concentration across the series. 3. Plot initial velocity (V₀) versus enzyme concentration [13]. A linear increase confirms the enzyme is the limiting factor. |

| Low intrinsic activity of the enzyme | Determine the Turnover Number (kcat): the maximum number of substrate molecules converted per enzyme molecule per second. | Employ enzyme engineering strategies to improve the catalytic efficiency of the active site [14] [15]. | Protocol: Determining Kinetic Parameters (kcat, KM) 1. Perform a series of reactions with varying substrate concentrations. 2. Measure initial velocities for each substrate concentration. 3. Plot data on a Michaelis-Menten or Lineweaver-Burk plot. 4. Calculate KM and Vmax. kcat = Vmax / [Total Enzyme]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Poor Product Selectivity

Problem: Your catalyst is producing unwanted byproducts instead of the desired target molecule.

| Common Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution | Relevant Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inherent enzyme promiscuity | Analyze the reaction mixture via HPLC or LC-MS to identify and quantify all products formed from the primary substrate. | Use directed evolution or rational design to narrow the enzyme's active site and suppress off-target activities [14] [16]. | |

| Non-specific binding of intermediates | Use in situ spectroscopy (e.g., DRIFTS) to identify adsorbed intermediate species on the catalyst or support surface [17]. | Modify the support material or enzyme environment to prevent undesirable interactions that lead to side reactions. | |

| Unfavorable reaction thermodynamics/kinetics for desired pathway | Calculate the theoretical thermodynamic landscape of potential pathways. Use modeling to predict flux distributions. | Redesign the synthetic pathway using "mix and match" approaches or introduce novel enzyme chemistries to create a more selective route [14]. | Protocol: Analyzing Reaction Selectivity 1. Run the catalytic reaction to a low conversion (e.g., <20%). 2. Quench the reaction rapidly. 3. Use a calibrated analytical method (e.g., GC-FID, HPLC-UV) to separate and quantify all products and remaining substrate. 4. Calculate Selectivity (%) = (Moles of Desired Product / Total Moles of All Products) × 100%. |

| Mis-identification of native enzyme function | Perform genome mining and sequence analysis with tools like genome neighborhood networks to better predict enzyme specificity [14] [16]. | Characterize putative enzymes biochemically to confirm activity before integrating them into a pathway. |

Troubleshooting Guide 3: Loss of Catalytic Stability

Problem: Your catalyst's activity decreases significantly over time or across reaction cycles.

| Common Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution | Relevant Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme denaturation (thermal, chemical) | Measure residual enzyme activity after incubating under reaction conditions for different time periods. | Implement enzyme immobilization strategies to rigidify the protein structure, or use a polymer matrix to provide a stabilizing microenvironment [18]. | Protocol: Testing Operational Stability Over Time 1. Set up a single reaction mixture or a continuous flow system. 2. Periodically sample the reaction and measure the reaction rate or product yield. 3. Plot Relative Activity (%) vs. Time-on-Stream (TOS) or Number of Reaction Cycles to visualize the decay profile [19]. |

| Oxidative deactivation or irreversible inhibition | Test if activity can be restored by dialysis or buffer exchange to remove small molecules. Add reducing agents (e.g., DTT) to the mix. | Identify and remove the source of the inhibitor from the substrate stream. Use engineered strains with oxidative stress resistance. | |

| Leaching of metal cofactors or active sites | Analyze the reaction supernatant after catalysis using ICP-MS for metal content. | Improve metal binding affinity through protein engineering or use more stable metal-organic frameworks for encapsulation. | |

| Sintering or agglomeration of catalytic species | Use techniques like STEM before and after reaction cycles to observe changes in particle size and dispersion [18]. | Choose or design supports that induce Strong Metal-Support Interactions (SMSI) to anchor catalytic atoms and prevent their migration [19] [18]. | |

| Fouling or coking (carbon deposition) | Use Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to measure weight loss due to carbon burn-off on spent catalysts. | Introduce supports with high Oxygen Storage Capacity (OSC), like ceria-zirconia (CZ), to gasify carbon deposits as they form [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important metric for comparing two different catalysts? There is no single most important metric; a balanced evaluation is crucial. Conversion tells you how much substrate is consumed, Selectivity tells you how efficiently that consumed substrate is turned into your desired product, and Stability tells you how long the catalyst can maintain its performance. A catalyst with high conversion but poor selectivity wastes resources, while a highly selective but unstable catalyst is not practical for industrial use.

Q2: How can I rapidly improve the selectivity of an existing enzyme in my pathway? A rapid approach is to use data-driven enzyme engineering [15]. You can create a mutant library and use high-throughput screening to identify variants with altered selectivity. Alternatively, explore the enzyme's natural diversity by mining genomic databases for homologous enzymes with similar functions but potentially different selectivity profiles [16].

Q3: Our immobilized catalyst shows good initial activity but rapidly deactivates. What is the most likely culprit? The most common causes are leaching of the active species from the support or pore blockage/sintering [18]. To diagnose leaching, analyze the reaction solution after catalysis for the presence of the catalytic metal or enzyme. To diagnose sintering, examine the spent catalyst with electron microscopy to see if nanoparticle size has increased.

Q4: What are the best practices for reporting catalytic stability in a publication? Always report data as activity (or conversion/selectivity) versus time-on-stream (TOS) for continuous processes, or activity versus cycle number for batch processes. The plot should clearly show the deactivation profile. Additionally, characterize the spent catalyst to propose a mechanism for deactivation (e.g., via TGA for coking, STEM for sintering, or XPS for oxidation state changes) [19].

Q5: How can I design a synthetic pathway that is inherently more efficient than natural pathways? Move beyond basic "copy, paste, and fine-tuning" of natural pathways. Employ "mix and match" approaches that freely recombine enzymes from different organisms to create more direct, thermodynamically favorable routes. For the greatest gains, consider incorporating novel enzyme chemistries created through computational design to access reactions not found in nature [14].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics and Their Calculations

| Metric | Formula / Definition | Ideal Value / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion (X) | ( X (\%) = \frac{[S]0 - [S]}{[S]0} \times 100 ) | Depends on process goals; high conversion is typically desired. |

| Where [S]₀ is initial substrate concentration and [S] is concentration at time t. | ||

| Selectivity (S) | ( S (\%) = \frac{[P]}{[S]_0 - [S]} \times 100 ) | Closer to 100% indicates efficient use of consumed substrate to form the desired product (P). |

| Yield (Y) | ( Y (\%) = \frac{[P]}{[S]_0} \times 100 = \frac{X \times S}{100} ) | A holistic metric combining conversion and selectivity. |

| Turnover Number (TON) | ( TON = \frac{\text{Moles of converted substrate}}{\text{Moles of catalytic site}} ) | Higher TON indicates a more productive and cost-effective catalyst. |

| Turnover Frequency (TOF) | ( TOF (s^{-1}) = \frac{TON}{\text{Time (s)}} ) | The reaction rate per active site. A higher TOF indicates a more active catalyst [18]. |

| Time-on-Stream (TOS) | Total time the catalyst is exposed to reactant flow under operational conditions. | A longer TOS with stable performance indicates superior catalyst stability [19]. |

Table 2: Exemplary Catalytic Performance from Literature

| Catalyst System | Reaction | Key Performance Indicators | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiCo Bimetal Alloy | CO₂ Hydrogenation to CH₄ | CH₄ Selectivity: 98%Production Rate: 55.60 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹Stability: ~18.82% decline after 86 h TOS | [17] |

| Pt/FeOx Single-Atom Catalyst | CO Oxidation | Turnover Frequency (TOF): 0.311 s⁻¹CO Conversion: 20% at 80°C | [18] |

| Ir/CZ (Ceria-Zirconia) | Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM) | Stability: Stable TOS performanceCoking Resistance: Superior to Ir on other supports (Ir/γ-Al₂O₃ > Ir/ACZ > Ir/CZ) | [19] |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Diagram: Troubleshooting Workflow

Diagram: Enzyme Engineering for Improved Catalysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Catalytic Performance Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Evaluation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ceria-Zirconia (CZ) Support | High oxygen storage capacity (OSC) support for metal catalysts. Promotes CO₂ activation and removes carbon deposits, enhancing stability and selectivity [19]. | Ideal for reactions prone to coking, like dry reforming of methane (DRM). |

| Polymer Matrices (N-containing) | Stabilize single-atom catalysts (SACs) by coordinating metal atoms with lone-pair electrons from heteroatoms like nitrogen, preventing agglomeration [18]. | Useful for creating well-defined, sinter-resistant catalytic sites. |

| Enzyme Immobilization Resins | Solid supports (e.g., functionalized polymers, silica) for attaching enzymes. Improve enzyme stability, facilitate reusability, and simplify product separation. | Choice of resin (pore size, functionality) depends on the enzyme and reaction conditions. |

| Directed Evolution Kits | Commercial kits for creating mutant enzyme libraries. Enable rapid improvement of enzyme properties like selectivity, stability, and activity under non-natural conditions [14] [15]. | Require a high-throughput screening assay for the desired catalytic property. |

| Analytical Standards (Substrates/Products) | Pure compounds used for calibrating analytical equipment (GC, HPLC, LC-MS). Essential for accurate quantification of conversion, yield, and selectivity. | Critical for generating reliable and reproducible performance data. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Enzyme Experimentation Issues

Incomplete or No DNA Digestion with Restriction Enzymes

Problem: Restriction enzymes fail to cut DNA completely at recognition sites, leading to unexpected DNA fragment sizes on gels [20].

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Enzyme Inactivation | Check expiration date; avoid >3 freeze-thaw cycles; store at -20°C in non-frost-free freezer [20]. |

| Suboptimal Buffer | Use manufacturer-recommended buffer; ensure required cofactors (Mg²⁺, DTT, ATP) are present [20]. |

| High Glycerol | Keep final glycerol concentration <5% (enzyme volume ≤10% of total reaction) [20]. |

| DNA Methylation | Check enzyme methylation sensitivity; use dam⁻/dcm⁻ E. coli hosts for plasmid propagation [20]. |

| Substrate Structure | For supercoiled plasmids, use 5-10 units/μg DNA; ensure sites aren't buried or near DNA ends [20]. |

Unexpected Cleavage Patterns (Star Activity)

Problem: DNA fragments appear at sizes not matching expected cleavage pattern due to non-specific activity [20].

- Reduce Enzyme Amount: Use ≤10 units/μg DNA; avoid prolonged incubation [20] [21].

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Use recommended salt concentration and pH; avoid substituting divalent cations [20].

- Prevent Evaporation: Use thermal cycler with heated lid to maintain reaction volume and prevent glycerol concentration increases [20].

- Consider HF Enzymes: Use engineered High-Fidelity (HF) restriction enzymes designed to eliminate star activity [21].

Diffused or Smeared DNA Bands

Problem: Poorly separated, blurry bands make interpretation difficult [20].

- Improve DNA Quality: Repurify DNA if smearing appears in undigested controls; use silica spin-column purification [20].

- Remove Enzyme-DNA Complexes: Heat digested DNA at 65°C for 10 minutes with loading buffer containing 0.2% SDS prior to electrophoresis [20] [21].

- Eliminate Nuclease Contamination: Prepare fresh reagents, buffers, and gels; use nuclease-free water [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the fundamental differences between natural enzymes and synthetic enzymes (synzymes)?

The table below summarizes key distinctions between natural and synthetic enzyme systems based on their origin, stability, and applications [22] [23].

| Category | Natural Enzymes | Synthetic Enzymes (Synzymes) |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Biological macromolecules (proteins, ribozymes) | Engineered frameworks (MOFs, DNAzymes, small molecules) [22]. |

| Stability | Sensitive to pH, temperature, and organic solvents | High stability across broad environmental ranges [22]. |

| Specificity | Highly specific, evolved for particular reactions | Tunable specificity via rational design and selection [22]. |

| Catalytic Efficiency | High under optimal physiological conditions | Comparable or superior in non-physiological conditions [22]. |

| Production Method | Fermentation or cell culture extraction | Chemical synthesis or nanofabrication [22]. |

| Customization | Limited by evolutionary constraints | Readily modified for target applications [22]. |

How is artificial intelligence revolutionizing enzyme engineering?

AI and machine learning are transforming enzyme catalysis by [24]:

- Accelerating Design: Generative models explore vast sequence spaces more efficiently than directed evolution, predicting functional enzymes with novel activities [24].

- Enabling De Novo Creation: AI models like protein language models can design entirely new enzyme structures not found in nature [24].

- Optimizing Pathways: Graph neural networks help design compatible modular enzyme assemblies for complex biosynthesis [25].

- Predicting Compatibility: AI tools forecast functional interoperability between enzyme modules in synthetic pathways [25].

What advantages do synthetic enzyme systems offer for industrial applications?

Synzymes provide significant benefits for industrial biotechnology and drug development [22] [26]:

- Environmental Robustness: Function under extreme pH, temperature, and solvent conditions that denature most natural enzymes [22].

- Sustainable Manufacturing: Enable greener chemical processes with reduced waste and energy consumption [22].

- Novel Reactivity: Perform chemical transformations inaccessible to natural enzymes, expanding synthetic possibilities [26].

- Biosensing Capabilities: Synthetic peroxidases and oxidases effectively detect biomarkers and pollutants [22].

How can researchers balance synthetic biology with synthetic chemistry approaches?

The most effective strategies combine both approaches [26]:

- Hybrid Pathways: Use synthetic biology for multi-step biosynthesis under uniform conditions, then apply synthetic chemistry for final modifications [26].

- In Vitro Biocatalysis: Employ purified enzymes for specific challenging reactions within traditional synthetic sequences [26].

- Cellular Manufacturing: Engineer cells to perform numerous consecutive steps without intermediate purification, then use synthetic chemistry for final product isolation [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function in Enzyme Experiments |

|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | Specific DNA cleavage for cloning and assembly; require optimized buffers [20]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous synzyme scaffolds providing high surface areas and tunable catalysis [22]. |

| Synthetic Coiled-Coils | Standardized connectors for modular enzyme assembly and complex formation [25]. |

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher | Protein conjugation system creating covalent links between enzyme modules [25]. |

| DNAzymes | Programmable DNA-based catalysts for specific biochemical reactions and biosensing [22]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Statistical approach optimizing multiple assay parameters simultaneously rather than one-factor-at-a-time [27]. |

Experimental Workflow: DBTL Cycle for Enzyme Engineering

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a systematic framework for engineering modular enzyme assemblies, integrating computational design with experimental validation [25].

Experimental Protocol: Optimization of Enzyme Assay Conditions

For reliable enzyme kinetics and activity measurements, follow this systematic optimization protocol [27]:

Materials Required

- Purified enzyme (natural or synthetic)

- Substrate(s) with varying concentrations

- Recommended reaction buffer system

- Cofactors or additives (Mg²⁺, DTT, NAD+, etc.)

- Stop solution or detection reagents

- Spectrophotometer or appropriate detection instrument

Step-by-Step Methodology

Initial Buffer Screening

- Test multiple buffer systems (phosphate, Tris, HEPES) at physiological pH (6-8)

- Include essential cofactors based on enzyme requirements

- Run preliminary activity assays to identify promising conditions

Design of Experiments (DoE) Setup

- Instead of one-factor-at-a-time, use fractional factorial design

- Simultaneously vary key parameters: pH, temperature, ionic strength, enzyme concentration

- This approach identifies optimal conditions in days rather than weeks [27]

Response Surface Methodology

- Refine optimal conditions from initial screening

- Model interactions between factors for maximum activity

- Establish robust assay window with adequate signal-to-noise

Validation and Reproducibility

- Confirm optimal conditions with triplicate measurements

- Test enzyme stability under optimized conditions over time

- Establish linear range for enzyme concentration and incubation time

This systematic approach ensures reproducible, optimized enzyme assays for both natural and synthetic enzyme systems, facilitating accurate comparison of catalytic efficiency.

Advanced Engineering Techniques: Protein Design, Computational Modeling, and Cascade Implementation

In the quest to optimize enzymatic catalysts for synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development, two powerful strategies have emerged: directed evolution, which mimics natural selection in the laboratory, and rational design, which leverages computational and structural insights. For researchers engineering synthetic pathways, enhancing the catalytic efficiency of flux-controlling enzymes is often the key to achieving viable production yields. This technical support center provides practical guidance for troubleshooting and implementing these enzyme engineering methodologies, enabling the development of robust biocatalysts for next-generation applications from biomanufacturing to drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between directed evolution and rational design?

- Directed Evolution is an iterative laboratory methodology that involves introducing random mutations into a gene and then screening or selecting for variants with enhanced properties, such as activity, stability, or substrate specificity. It does not require prior structural knowledge and is ideal for optimizing complex functions that are not fully understood [28] [29].

- Rational Design relies on computational models and structural knowledge of the enzyme to make specific, targeted mutations that are predicted to improve function. This approach is more targeted but requires detailed understanding of structure-function relationships [30].

Q2: When should I choose one method over the other? The choice often depends on the available information and tools.

- Use Directed Evolution when:

- High-throughput screening methods are available for your enzyme's function.

- The structural basis for the desired function is unknown.

- You need to improve complex traits like organic solvent stability or alter substrate promiscuity.

- Use Rational Design when:

- A high-resolution structure or a reliable model of your enzyme is available.

- You have a clear hypothesis about which residues or regions to mutate (e.g., active site engineering).

- You want to make minimal, targeted changes, such as for mechanistic studies.

- Hybrid Approaches that combine both methods are increasingly common and powerful [28].

Q3: What are common reasons for failure in directed evolution campaigns? Common pitfalls include:

- Inadequate Library Diversity: The library does not sample a sufficient portion of sequence space to find beneficial mutations.

- Low-Quality Screening Assays: The screening method is not sufficiently sensitive, specific, or high-throughput to identify improved variants amidst a large background of neutral or deleterious mutants.

- Epistatic Interactions: Beneficial single mutations may not combine favorably in higher-order mutants, a phenomenon known as epistasis [31].

- Expression and Solubility Issues: Improved variants may not express well or may aggregate, masking potential gains in activity.

Q4: How can computational tools and AI accelerate enzyme engineering? Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are transforming both directed evolution and rational design.

- Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM-2) can predict the fitness of sequence variants, helping to design smarter, higher-quality initial libraries for directed evolution [31].

- Fully Computational Workflows can now design stable, efficient enzymes de novo without any experimental optimization, as demonstrated by the design of Kemp eliminases with catalytic efficiencies rivaling natural enzymes [30].

- Autonomous Platforms integrate AI and robotics to run fully automated design-build-test-learn cycles, dramatically speeding up the engineering process [31].

- Function Prediction Tools like SOLVE use interpretable ML models to predict enzyme function directly from primary sequence, aiding in the annotation and prioritization of candidate enzymes [32].

Q5: How can I improve the spatial organization of enzymes in a synthetic pathway? Spatial organization is critical for multi-step catalytic cascades. The iMARS framework provides a standardized method for the rational design of optimal multienzyme architectures. It uses a "space-efficiency code" that integrates high-throughput activity tests and structural analysis to predict the performance of different multienzyme complexes, thereby maximizing the catalytic efficiency of the entire pathway [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inefficient Restriction Digestion in Cloning Steps

Cloning is a fundamental step in constructing gene libraries for enzyme engineering. Inefficient digestion can halt progress.

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or No Digestion [20] [34] | Inactive enzyme, improper storage, or too many freeze-thaw cycles. | Store enzymes at –20°C; avoid frost-free freezers; limit freeze-thaw cycles; use a benchtop cooler. |

| Incorrect reaction buffer or cofactors. | Use the manufacturer's recommended buffer; verify need for additives like DTT or Mg²⁺. | |

| Methylation of DNA blocking cleavage. | Check enzyme's methylation sensitivity; propagate plasmid in dam⁻/dcm⁻ E. coli strains. | |

| Enzyme activity inhibited by contaminants. | Repurify DNA using silica spin-columns or phenol-chloroform extraction. | |

| Unexpected Cleavage Pattern [20] [34] | Star activity (non-specific cleavage). | Reduce enzyme amount and incubation time; ensure glycerol concentration is <5%; use High-Fidelity (HF) enzymes. |

| Contamination with another enzyme. | Use new, aliquoted tubes of enzyme and buffer to avoid cross-contamination. | |

| Bound enzyme altering DNA migration. | Heat digested DNA with SDS (0.1-0.5%) prior to electrophoresis to dissociate the enzyme. |

Problem 2: Low Catalytic Efficiency in Designed Enzyme Variants

This is a common challenge in both rational design and directed evolution.

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low kcat/KM [30] | Sub-optimal active site geometry. | Use advanced computational design (e.g., FuncLib) to optimize the electrostatic preorganization and precise positioning of catalytic residues. |

| Low protein stability or expressibility. | Incorporate stabilizing mutations throughout the protein scaffold, not just the active site, to enhance foldability and expression yield. | |

| Low kcat (Turnover) [30] [29] | Inefficient chemical step. | Focus design and evolution on transition state stabilization. Consider conformational dynamics and long-range electrostatic effects often missed in static designs. |

| Poor substrate binding or product release. | Engineer access tunnels and surface loops to facilitate substrate diffusion and product egress. | |

| Low Activity in a Multi-Enzyme Pathway [33] | Sub-optimal spatial organization. | Use a framework like iMARS to design synthetic enzyme complexes that channel intermediates, enhancing overall pathway flux. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Fully Computational Workflow for De Novo Enzyme Design

This protocol, based on a recent breakthrough in designing highly efficient Kemp eliminases, enables the creation of stable and active enzymes from scratch without experimental optimization [30].

- Backbone Generation: For your target protein fold (e.g., TIM-barrel), generate thousands of diverse backbones using combinatorial assembly of fragments from homologous natural proteins.

- Scaffold Stabilization: Apply a computational protein repair tool (e.g., PROSS) to stabilize the designed conformations and ensure foldability.

- Active Site Design:

- Define a "theozyme" (theoretical catalytic constellation) using quantum-mechanical calculations for your target reaction.

- Use geometric matching to position the theozyme into each generated backbone.

- Optimize the entire active site and surrounding residues using atomistic design calculations (e.g., with Rosetta).

- Filtering and Selection: Filter the millions of resulting designs using a multi-objective function that balances low system energy, high catalytic desolvation, and optimal geometry.

- In Silico Affinity Maturation: For the top designs, apply a flexible active-site redesign method (e.g., FuncLib) to computationally optimize residues for enhanced catalysis, using only atomistic energy as the guide.

Protocol 2: Autonomous Enzyme Engineering Using a Biofoundry

This protocol outlines an AI-powered autonomous workflow for rapidly engineering enzymes, as demonstrated for a halide methyltransferase and a phytase [31].

- Initial Library Design:

- Input: Provide the wild-type protein sequence.

- AI Design: Use a protein Large Language Model (LLM) (e.g., ESM-2) combined with an epistasis model (e.g., EVmutation) to generate a list of ~180 high-quality, diverse single-point mutants for the first round.

- Automated Build & Test Cycle:

- Build: The biofoundry (e.g., iBioFAB) executes automated modules for HiFi-assembly-based mutagenesis, transformation, colony picking, and protein expression.

- Test: The platform performs automated, high-throughput enzyme assays to quantify the fitness (e.g., specific activity) of each variant.

- Machine Learning & Iteration:

- The assay data is used to train a low-data machine learning model to predict variant fitness.

- The trained model proposes the next set of mutants, often combining beneficial mutations.

- The cycle (Steps 2-3) repeats autonomously for multiple rounds (e.g., 4 rounds over 4 weeks).

AI-Powered Autonomous Engineering Cycle

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Enzyme Engineering |

|---|---|

| TIM-barrel Scaffolds [30] | A stable and highly designable protein fold used as a backbone for grafting novel active sites in de novo enzyme design. |

| Kemp Elimination Substrate (5-nitrobenzisoxazole) [30] | A benchmark non-natural substrate used to test and validate the success of de novo enzyme design methodologies. |

| Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) [31] | A model enzyme for engineering altered substrate preference (e.g., improving ethyltransferase over methyltransferase activity). |

| Phytase (YmPhytase) [31] | A model enzyme for engineering improved activity under non-native conditions (e.g., enhanced activity at neutral pH). |

| iMARS Framework [33] | A standardized computational framework for designing optimal spatial architectures of multi-enzyme complexes to enhance cascade efficiency. |

| High-Fidelity (HF) Restriction Enzymes [34] | Engineered restriction enzymes that minimize star activity (non-specific cutting), crucial for reliable cloning of gene variants. |

| dam⁻/dcm⁻ E. coli Strains [20] [34] | Bacterial hosts used for plasmid propagation to avoid DNA methylation that can block digestion by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes. |

| FuncLib [30] | A computational method for designing smart, focused mutant libraries by restricting mutations to those found in natural protein families, then selecting low-energy combinations. |

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent successful enzyme engineering campaigns, highlighting the dramatic improvements achievable with modern methods.

| Engineered Enzyme / System | Engineering Method | Key Improvement | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) / Other Metric | Application / Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kemp Eliminase (Des27 opt) [30] | Fully Computational Design | >10,000-fold vs. early designs | 12,700 M⁻¹s⁻¹ (kcat = 2.8 s⁻¹) | De novo design; surpasses previous computational designs by two orders of magnitude. |

| Kemp Eliminase (with essential residue) [30] | Computational Design | Comparable to natural enzymes | >10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ (kcat = 30 s⁻¹) | Achieves parameters typical of natural enzymes. |

| Aldehyde Deformylating Oxygenase (ADO) [29] | Directed Evolution | 1000% (10-fold) increase in activity | Not specified | Terminal enzyme in propane synthesis pathway for next-generation biofuels. |

| Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) [31] | Autonomous AI Platform | 90-fold improved substrate preference; 16-fold higher ethyltransferase activity | Fold-improvement in specified activity | Synthesis of SAM analogs for biocatalytic alkylation. |

| Phytase (YmPhytase) [31] | Autonomous AI Platform | 26-fold higher activity at neutral pH | Fold-improvement in specified activity | Animal feed additive to improve phosphate nutrition. |

| Multienzyme Complexes (e.g., for resveratrol) [33] | iMARS (Rational Architecture) | 45.1-fold improved production | Fold-increase in product yield | Biomanufacturing of high-value compounds in vivo. |

Decision Workflow for Enzyme Engineering Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using QM/MM over pure QM methods for studying enzyme catalysis? The key advantage is efficiency. Quantum Mechanical (QM) methods that provide accuracy for modeling chemical reactions can scale poorly with system size (often O(N³) or worse), making them prohibitively expensive for entire enzymes. Molecular Mechanics (MM), which uses classical force fields, is much faster and allows for simulation of large systems. QM/MM combines the strengths of both: the region where the chemistry occurs (e.g., the active site) is treated with accurate QM, while the rest of the protein and solvent is treated with fast MM, making detailed studies of enzymes feasible [35] [36].

Q2: How do I decide which atoms to include in the QM region? The QM region should include the substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors, and key ions involved in the reaction. It is crucial to include enough atoms to accurately represent the chemistry, such as ensuring that charge transfer effects are captured. At the same time, the region should be as small and compact as possible to conserve computational resources, as the cost of QM calculations grows rapidly with the number of atoms [37] [38] [39]. Special care must be taken if the boundary between QM and MM regions cuts through a covalent bond (see Troubleshooting section).

Q3: What is the difference between mechanical and electrostatic embedding? This is a critical choice regarding how the QM and MM regions interact electrostatically.

- Mechanical Embedding: The QM-MM electrostatic interactions are treated at the MM level. The QM region's electron density is not polarized by the MM environment. This is not recommended for modeling reactions as the charge distribution in the QM region changes during the reaction, and a single set of MM parameters cannot accurately describe it [35] [39].

- Electrostatic Embedding: The partial charges of the MM atoms are included in the Hamiltonian for the QM calculation. This means the QM electron density is polarized by the MM environment, providing a more realistic description. This is the most widely used and recommended embedding scheme for biochemical applications [35] [38] [39].

Q4: My QM/MM calculation stops without an error message. What could be wrong? This is a common issue that can often be traced to problems with the MM force field parameters or the setup of the QM-MM boundary. Specifically, the force field may lack necessary parameters for certain atom types in the system, leading to a silent failure. Another potential cause is having a QM-MM boundary that does not cut through a carbon-carbon bond, as some interfaces require the linked MM atom to be carbon to properly cap the dangling bond [40]. Consult the troubleshooting guide below for detailed steps.

Q5: How do I validate my QM/MM setup and results? Validation is a multi-step process:

- System Preparation: Always minimize and equilibrate your system using MM before running QM/MM simulations [37].

- Methodology Check: Run a single-point energy calculation first to ensure the self-consistent field (SCF) converges and the energy is sensible [37].

- Energetic Plausibility: Compare calculated activation energies with known experimental ranges for enzymes (typically 5–25 kcal/mol, with most between 14–20 kcal/mol). Results outside this range may indicate a problem with the setup or proposed mechanism [39].

- Environmental Consistency: A good test is to compare reaction energetics in the gas phase, in water, and in the enzyme. A competent QM/MM model should clearly show the catalytic effect of the protein environment [39].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Errors and Solutions

Table 1: Common QM/MM errors, their likely causes, and solutions.

| Error / Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation stops without an error message. | Missing MM force field parameters for specific atom types; Incorrect boundary atom type. | Use a user-defined force field to supply missing parameters; Ensure the QM-MM boundary cuts through a carbon-carbon bond where the linked MM atom is a carbon [40]. |

| Self-Consistent Field (SCF) failure; electron density does not converge. | The QM region is not electronically neutral or has an incorrect spin state; The MM partial charges are too close to the QM density. | Check the total charge and spin multiplicity (e.g., singlet, doublet) of the QM region are set correctly; Consider using a larger QM region or a different QM/MM electrostatic scheme [37] [39]. |

| Unphysical energy or geometry results. | The MM system was not properly minimized and equilibrated before the QM/MM run; The QM method or basis set is inadequate. | Always run a full MM minimization and equilibration protocol before starting QM/MM [37]; Validate your QM method (functional/basis set) on a smaller model system resembling the active site [39]. |

| Artifacts from the QM-MM boundary cutting a covalent bond. | The dangling bond in the QM region is not properly saturated. | Employ a boundary scheme such as the link atom method, where a hydrogen atom is added to cap the QM valence [35] [38]. |

Workflow for a Robust QM/MM Simulation

The following diagram outlines a recommended workflow to prevent common issues and ensure reliable results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key software and computational "reagents" for QM/MM simulations in enzyme design.

| Item | Function in QM/MM Simulation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| System Preparation Tool | Prepares the initial protein structure: adds missing hydrogens, assigns protonation states, and solvates the system. | Examples: PDB2PQR, CHARMM-GUI, LEaP (AmberTools). Note: Correct protonation of catalytic residues is critical. |

| Molecular Mechanics (MM) Force Field | Describes the energy and forces for the classical region of the system (protein, solvent). | Examples: AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS. Note: Must be compatible with your QM/MM software [37]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Package | Performs the electronic structure calculation for the QM region; the "engine" for the chemistry. | Examples: CP2K [37] [38], Gaussian [41], Q-Chem [40]. Note: Must support QM/MM interfaces. |

| QM/MM Wrapper/Interface | Manages the communication and coupling between the QM and MM software. | Examples: GROMACS-CP2K interface [38], ONIOM (integrated in Gaussian) [41] [39]. Note: Can be additive or subtractive [39]. |

| Density Functional (Functional) | The approximation used to solve the quantum mechanical problem; determines accuracy for reaction energetics. | Examples: B3LYP, PBE, BLYP [41] [42] [38]. Note: Dispersion corrections are often essential for biomolecules [39]. |

| Basis Set | A set of mathematical functions that describes the QM region's electron orbitals. | Examples: DZVP-MOLOPT [38], 6-31G(d) [41]. Note: Polarization functions are a minimum requirement; diffuse functions can cause issues near the QM/MM boundary [39]. |

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Protocol for an Enzyme-Catalysed Reaction Study

The following protocol, adapted from best practices, outlines the steps for setting up a QM/MM simulation to study a reaction mechanism in an enzyme [37] [36] [39].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial protein structure (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank).

- Use a system preparation tool to add missing hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states to residues (especially in the active site), and add solvent molecules and ions to create a physiological simulation box.

- Generate the necessary MM topology and parameter files using a force field like AMBER, CHARMM, or GROMOS.

MM Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization of the entire system using MM to remove bad atomic contacts.

- Gradually heat the system from 0 K to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and equilibrate it under the desired ensemble (NVT, NPT). This step is crucial for achieving a stable starting structure for subsequent QM/MM runs.

QM Region Selection and Input Setup:

- Select the atoms for the QM region, typically the substrate, key catalytic residues, and any cofactors or metal ions.

- Set up the QM/MM input file. In a program like CP2K, this involves:

- Setting

METHOD = QMMMin the&FORCE_EVALsection. - Defining the

&QMMMsubsection to specify the QM atom indices and the type of embedding (use electrostatic embedding). - Defining the

&DFTsubsection to specify the QM method (e.g., functional like B3LYP, basis set like DZVP-MOLOPT), charge, and multiplicity.

- Setting

Testing and Production:

- Run a single-point energy calculation (

RUN_TYPE = ENERGY) first. Verify that the SCF procedure converges and that the total energy is sensible. - Once the setup is stable, perform the production simulation. This could be a geometry optimization to find minima and transition states, or a QM/MM molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for sampling. For MD, change

RUN_TYPEtoMDand add the appropriate&MDsubsection in the&MOTIONsection.

- Run a single-point energy calculation (

Advanced Considerations for Method Selection

- Additive vs. Subtractive Schemes: Additive QM/MM schemes are now generally preferred in biomolecular applications. They explicitly calculate QM-MM coupling terms and do not require MM parameters for the QM atoms, which is advantageous when the electronic structure changes during a reaction [39].

- Handling Covalent Boundaries: When the QM/MM boundary cuts through a covalent bond, the dangling bond on the QM atom must be capped. The most common method is the link atom scheme, where a hydrogen atom (the link atom) is added to saturate the QM valence. The forces on this link atom are then distributed to the atoms in the real bond [35] [38].

- Beyond DFT: While Density Functional Theory (DFT) offers the best trade-off for most enzymatic systems, for highest accuracy, especially for reactions involving biradicals or strong correlation, methods like spin-component scaled MP2 (SCS-MP2) can provide significant improvements over standard DFT functionals [39].

Multi-enzyme cascade reactions represent a powerful paradigm in synthetic biology and biocatalysis, integrating multiple enzymatic steps into unified processes that transform simple, inexpensive substrates into complex, high-value products. For researchers in drug development and synthetic pathway engineering, these cascades offer significant advantages: they eliminate the need for intermediate purification, shift unfavorable reaction equilibria toward product formation, and can handle unstable intermediates more effectively than single-step biotransformations [43]. Furthermore, the absence of cellular membranes enables direct process control and facilitates more straightforward bottleneck identification compared to whole-cell systems [44]. However, achieving high catalytic efficiency in these systems requires careful optimization across multiple parameters, as inefficiencies in any single component enzyme can dramatically reduce overall pathway performance. This technical guide addresses the most common optimization challenges and provides evidence-based solutions to enhance the productivity, yield, and stability of your multi-enzyme cascade systems.

Cascade Optimization Principles and Performance Metrics

Successful cascade optimization begins with clearly defined performance goals. Different applications may prioritize different metrics, and these goals can sometimes conflict, requiring careful balancing during the optimization process [45].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Enzyme Cascade Optimization

| Metric | Description | Impact on Process |

|---|---|---|

| Product Concentration | Final amount of target product (e.g., g·L⁻¹) | Influences downstream processing costs and reactor volume |

| Yield | Moles product per mole substrate (%) | Determines raw material efficiency and atomic economy |

| Space-Time Yield | Product formed per reactor volume per time (g·L⁻¹·h⁻¹) | Measures overall reactor productivity |

| Total Turnover Number (TTN) | Moles product per mole catalyst | Indicates catalyst lifetime and economic viability |

| Reaction Rate | Speed of product formation | Affects required enzyme load and processing time |

| Step & Atom Economy | Efficiency of conversion steps and atom incorporation | Reflects environmental impact and waste generation |

Competing optimization goals are common. For instance, high product concentrations do not always correlate with high reaction rates, as demonstrated by a 27-enzyme cascade for monoterpene production that achieved >95% yield and >15 g·L⁻¹ titers but at suboptimal reaction rates for industrial application [45]. Similarly, enzyme stability and activity do not necessarily correlate, as evidenced by a cascade where introducing a 40-fold more active enzyme came at the expense of reduced thermostability and lower total turnover numbers [45]. A careful ranking of optimization objectives specific to your application is therefore essential before beginning experimental work.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Cascade Challenges and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Multi-Enzyme Cascade Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Overall Conversion | • Suboptimal enzyme ratios• Cofactor depletion/limitation• Thermodynamic constraints• Incompatible optimal conditions for different enzymes | • Titrate enzyme activities to balance flux [44]• Implement cofactor regeneration systems [43]• Analyze pathway thermodynamics (ΔG'°) [46]• Find compromise conditions or use enzyme engineering |

| Product Inhibition | • Accumulation of inhibitory intermediates or final products | • Remove products in situ (e.g., continuous systems)• Engineer enzymes for reduced inhibition [46]• Increase enzyme load at inhibited step |

| Cofactor Limitations | • Stoichiometric consumption of expensive cofactors (ATP, NADPH) | • Incorporate efficient regeneration systems (e.g., PPK for ATP [43], GDH for NADPH)• Use polyphosphate for ATP regeneration instead of PEP [43] |

| Enzyme Incompatibility | • Differing pH or temperature optima• Proteolytic degradation• Cross-inhibition | • Compromise on single set of conditions [45]• Use enzyme immobilization for stabilization [47]• Spatial compartmentalization of incompatible steps |

| Accumulation of Intermediates | • Kinetic bottleneck at specific cascade step | • Identify rate-limiting step via time-course analysis• Increase enzyme load or find more active enzyme at bottleneck• Apply directed evolution to improve kinetic properties [47] |

| Poor Enzyme Stability | • Harsh reaction conditions (temperature, solvents)• Mechanical shear forces• Long process durations | • Screen thermostable enzyme variants [44]• Implement enzyme immobilization techniques [47]• Use continuous feeding of sensitive enzymes |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I quickly identify the rate-limiting step in my multi-enzyme cascade? Monitor intermediate accumulation over time using analytical methods (HPLC, GC, MS). The intermediate that accumulates significantly is likely the product of the rate-limiting step. Alternatively, systematically vary the concentration of each enzyme while keeping others constant; the enzyme that, when increased, yields the largest improvement in overall flux is likely the primary bottleneck [45] [44].

Q2: What strategies are most effective for balancing enzyme ratios in a cascade? Two primary approaches exist: knowledge-based and empirical. The knowledge-based approach involves determining kinetic constants (KM, vmax) for each enzyme and using modeling to predict optimal ratios [44]. The empirical approach involves titrating one enzyme at a time against fixed amounts of others to identify the ratio that maximizes product formation [44]. A combination of both methods often works best.

Q3: How can I maintain cofactor balance in redox-neutral or energy-requiring cascades? Design cascades to be inherently cofactor-balanced where possible. For ATP-dependent reactions, implement efficient regeneration systems such as polyphosphate kinases (PPK2) with inexpensive polyphosphate as a phosphate donor [43]. For NAD(P)H-dependent systems, couple oxidative and reductive steps to achieve redox neutrality, or use formate dehydrogenase for NADH regeneration [46].

Q4: What practical methods can enhance cascade stability for industrial applications? Enzyme immobilization on solid supports significantly enhances thermal stability, pH stability, and enables enzyme reuse [47]. Screening for and engineering thermostable enzyme variants, often from thermophilic organisms, can dramatically improve operational lifetime [44]. Process design strategies like continuous operation with enzyme retention can also extend functional cascade duration.

Q5: How do I approach optimizing a cascade when reaction conditions (pH, T) differ between enzymes? First, identify a compromise condition where all enzymes maintain sufficient activity. If this fails, consider spatial compartmentalization to separate incompatible steps, or engineer enzyme variants (through directed evolution or rational design) to function optimally under your desired unified conditions [45] [47].

Experimental Protocols for Key Optimization Procedures

Protocol: Enzyme Ratio Optimization by Empirical Titration

This protocol outlines a systematic method for determining the optimal enzyme ratio in a multi-enzyme cascade, based on the approach used to optimize an L-alanine production cascade [44].

Materials:

- Purified enzyme components (E1, E2, E3...En)

- Substrate solution

- Reaction buffer

- Cofactors (NAD, ATP, etc. as required)

- Stopping reagent (e.g., acid, heat)

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Establish Baseline Activity: Set up the complete cascade reaction with equal mass or activity units of each enzyme. Measure initial product formation rate.

- Single-Enzyme Titration: Hold all enzymes constant except one (E1). Vary E1 concentration over a defined range (e.g., 0.1x to 10x baseline).

- Product Measurement: Incubate reactions under standard conditions (temperature, pH) and quantify product formation at multiple time points.

- Identify Optimal Point: Determine the E1 concentration that maximizes product yield or rate without causing substrate depletion or inhibition.

- Iterate Process: Using the optimized E1 concentration, repeat steps 2-4 for E2, then E3, and so forth through all cascade components.

- Final Validation: Confirm the optimized ratio in a single experiment with all enzymes at their determined optimal concentrations.

Notes: This iterative process may require 2-3 complete cycles for convergence. Monitor intermediate accumulation to ensure balanced flux. The optimized L-alanine cascade achieved >95% yield through this approach [44].

Protocol: ATP Regeneration System for Nucleotide-Dependent Cascades

This protocol details the implementation of a polyphosphate-based ATP regeneration system to support ATP-dependent enzymes in cascade reactions, adapted from cGAMP synthesis research [43].

Materials:

- Adenosine kinase (ScADK)

- Polyphosphate kinase 2 (AjPPK2, SmPPK2)

- Adenosine or AMP

- Polyphosphate (polyP, average chain length >100)

- GTP (for cGAMP synthesis example)

- cGAS enzyme

- Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, pH 8.0

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare master mix containing:

- Buffer components

- 5 mM adenosine

- 10 mM GTP

- 10 mM polyphosphate

- 5 mM MgCl₂

- Enzyme Addition: Add optimized concentrations of:

- ScADK (0.1-1 µM)

- AjPPK2 (0.5-2 µM)

- SmPPK2 (0.5-2 µM)

- cGAS (0.5-5 µM)

- Reaction Incubation: Incubate at 37°C with gentle mixing for 2-24 hours.

- Product Quantification: Monitor cGAMP formation by HPLC or spectrophotometric assay.

- System Optimization: Adjust enzyme ratios to ensure ATP supply matches consumption rate, preventing accumulation of AMP/ADP.

Notes: This system enabled synthesis of pharmacologically relevant 2'3'-cGAMP from inexpensive adenosine, demonstrating efficient cofactor recycling [43]. For different ATP-consuming enzymes, adjust enzyme ratios to match specific ATP consumption rates.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Multi-Enzyme Cascade Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Cascade Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Polyphosphate kinases (PPK2) with polyphosphate [43], Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) with glucose [44], Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) with formate | Regenerate expensive cofactors (ATP, NAD(P)H) stoichiometrically, drastically reducing costs |

| Thermostable Enzymes | Dihydroxyacid dehydratase from Sulfolobus solfataricus (SsDHAD) [44], L-alanine dehydrogenase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AfAlaDH) [44] | Enhance cascade stability at elevated temperatures and extend operational lifetime |

| Enzyme Engineering Tools | Error-prone PCR kits, DNA shuffling kits, High-throughput screening systems [47] | Create enzyme variants with improved activity, stability, or altered specificity for cascade balancing |