Strategic Optimization of Gene Expression in Heterologous Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Optimizing gene expression levels is a critical determinant for the successful implementation of heterologous pathways in bioproduction and therapeutic development.

Strategic Optimization of Gene Expression in Heterologous Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

Optimizing gene expression levels is a critical determinant for the successful implementation of heterologous pathways in bioproduction and therapeutic development. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists, synthesizing foundational principles with cutting-edge methodological advances. We explore the strategic selection of host organisms—from classic E. coli and yeast systems to emerging non-model bacteria—and detail modern techniques like condition-specific codon optimization and precise transcriptional control. A dedicated troubleshooting framework addresses common obstacles including low expression, protein aggregation, and host toxicity. Furthermore, we examine rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques essential for evaluating the performance and evolutionary context of engineered pathways. This holistic guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance yield, functionality, and scalability in the production of valuable secondary metabolites and biopharmaceuticals.

Core Principles and Host Selection for Heterologous Expression

Defining Heterologous Pathways and Their Role in Metabolic Engineering

Core Concepts: Heterologous Pathways and Metabolic Engineering

What is a heterologous pathway?

A heterologous pathway is a linked series of biochemical reactions introduced into a host organism through foreign genes, enabling the host to produce compounds it does not naturally synthesize [1] [2]. In metabolic engineering, these pathways are incorporated into microbial hosts to create microbial cell factories for producing valuable chemicals, fuels, pharmaceuticals, and materials from renewable resources [3] [4].

What is the fundamental goal of metabolic engineering?

Metabolic engineering aims to rewire cellular metabolism through genetic modifications to enhance production of desired substances [5]. It operates on three key metrics known as TYR: Titer, Yield, and Rate [4]. The field has evolved through three distinct waves, from initial rational pathway analysis to systems biology approaches, and now to modern synthetic biology applications that allow complete design and construction of synthetic pathways for both natural and non-natural chemicals [4].

Why are heterologous pathways crucial for metabolic engineering?

Heterologous pathways allow researchers to expand the biosynthetic capabilities of well-characterized host organisms. Instead of relying on native producers that may be difficult to cultivate or engineer, scientists can transfer metabolic pathways into hosts that are genetically tractable, robust, and optimized for industrial fermentation [1]. This approach has successfully produced antimalarial drug precursors like artemisinic acid, biofuels, and numerous commodity chemicals [3] [4].

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Heterologous Pathway Engineering

Host Selection and Engineering

FAQ: How do I select the most appropriate host organism for my heterologous pathway?

Choosing a suitable host is one of the most critical decisions in metabolic engineering [1]. Consider the factors in Table 1, which compares common eukaryotic hosts [1] [2].

Table 1: Eukaryotic Host Organisms for Heterologous Pathway Expression

| Host | Benefits | Handicaps | Common Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | Low-maintenance, fast-growing, high protein expression, GRAS status, good protein folding and modification [1] [2] | Potential hyperglycosylation, tough cell wall, low diversity of native secondary metabolites [1] [2] | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris, Yarrowia lipolytica [3] [1] |

| Filamentous Fungi | Low-maintenance, fast-growing, high diversity of native secondary metabolites [1] [2] | Complex metabolism competition, hazardous spores, limited expression levels [1] [2] | Aspergillus spp., Neurospora crassa [1] |

| Plants | Suitable for plant pathway expression, large enzyme expression, chloroplast localization [1] [2] | High cost, complex transformation, low growth rates [1] [2] | Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis thaliana [1] |

| Animal Cell Cultures | Efficient for animal-derived enzymes, specific protein modifications [1] [2] | Very high cost, specific cultivation needs, low growth rate [1] [2] | Mammalian cells, Insect cells [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: My pathway isn't functioning after introduction into the host. What should I check?

- Verify Gene Integration and Expression: Confirm successful integration of heterologous genes and transcription using PCR and RT-PCR.

- Check Codon Optimization: Ensure heterologous genes are codon-optimized for your host organism to improve translation efficiency [4].

- Assess Enzyme Function: Test for the presence and activity of the expressed enzymes, as heterologous expression can sometimes lead to misfolding or inclusion bodies.

- Evaluate Metabolic Burden: High expression of heterologous pathways can burden host metabolism; consider using inducible promoters to decouple growth and production phases [6].

Pathway Balancing and Optimization

FAQ: I've confirmed my pathway is expressed, but product titers are low. What are the common causes?

Low product titers often result from imbalanced pathway expression, leading to metabolic bottlenecks or accumulation of toxic intermediates [4] [7]. A recent study on astaxanthin production in yeast demonstrated that combinatorial optimization of gene expression alone can double production titers [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Pathway Balancing in Astaxanthin Production [7]

| Engineering Strategy | Expression Range for Pathway Genes | Resulting Improvement in Pathway Flux | Final Titer Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEMbLeR Method (Promoter/terminator shuffling) | 120-fold variation per gene | Significantly enhanced | >2-fold increase |

Troubleshooting Guide: How can I balance the expression of multiple genes in a pathway?

- Modular Pathway Engineering: Divide the pathway into modules (e.g., upstream precursor supply and downstream biosynthesis) and optimize them separately [4].

- Combinatorial Optimization: Use advanced tools like the GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) system [7]. This method uses Cre recombinase to shuffle promoter and terminator modules flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites, generating vast strain libraries with varying expression profiles for each gene in a single step.

- Computational Modeling: Employ genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) and flux balance analysis to predict enzyme expression levels and identify flux constraints [8] [4] [5]. The QHEPath algorithm is one such tool that can suggest heterologous reactions to break theoretical yield limits [8].

Cofactor and Metabolic Burden Management

FAQ: My pathway functions initially but production stops or cells lose viability. Why?

This can indicate cofactor imbalance, toxicity of intermediates or products, or an unsustainable metabolic burden [4]. Cells may also evolve to inactivate the pathway if it imposes a fitness cost.

Troubleshooting Guide: Strategies to improve stability and viability

- Cofactor Engineering: Balance the supply and demand of crucial cofactors like NADH, NADPH, and ATP. This can involve overexpressing enzymes that regenerate required cofactors or engineering enzymes to use different, more abundant cofactors [4].

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement genetic circuits that sense metabolic states and dynamically regulate pathway expression. This can decouple growth and production phases, preventing toxicity and burden during critical growth periods [4].

- Tolerance Engineering: Evolve or engineer host strains to be more tolerant to the target product or toxic intermediates. This can be done through adaptive laboratory evolution or by engineering membrane transporters [4].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Standard Workflow for Heterologous Pathway Expression

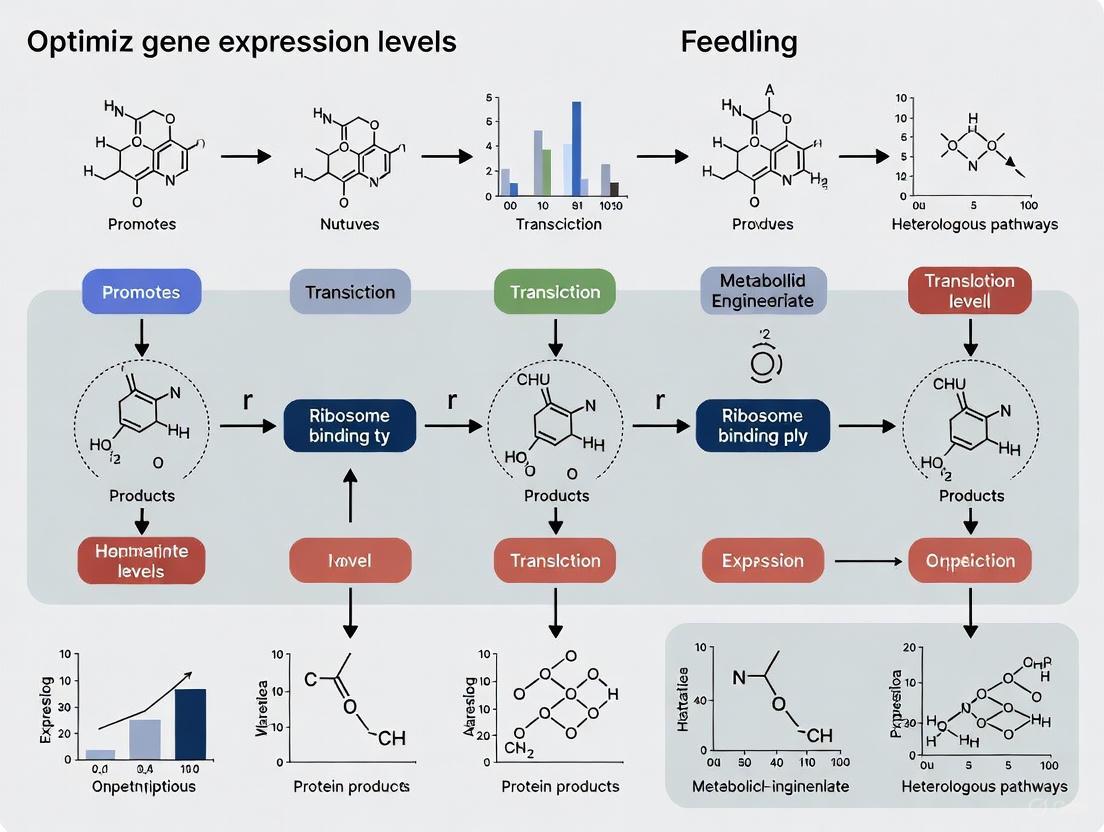

The typical workflow for establishing a heterologous pathway involves a cyclic process of design, build, test, and learn (DBTL) [3] [1], as visualized below.

Protocol Details:

- DNA Isolation and Gene Identification: Isolate genes or gene clusters responsible for biosynthesis of the target compound from the native producer. With advancing bioinformatics, these genes are often identified from genomic databases [1] [2].

- Vector Construction: Incorporate the biosynthetic pathway genes into stable expression vector(s). Use standardized assembly techniques (e.g., Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly) for efficiency. Ensure vectors are compatible with the chosen host [1] [2].

- Host Selection and Transformation: Select an appropriate host based on the criteria in Table 1. Transform the constructed vector into the host organism using suitable methods (e.g., electroporation, chemical transformation, conjugation) [1].

- Cultivation and Screening: Cultivate the engineered strain and screen for production of the target metabolite using analytical methods like HPLC or GC-MS [1].

- Pathway Optimization: This is an iterative step. Apply strategies like promoter engineering, codon re-optimization, and enzyme engineering to balance flux and improve yield [4] [7].

- Process Scale-up: Optimize fermentation conditions (media, feeding strategy, aeration) in bioreactors to maximize titer, yield, and productivity (TYR) at scale [6].

The GEMbLeR method is a powerful technique for rapidly optimizing expression of multiple pathway genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Principle: The system uses Cre recombinase to shuffle libraries of promoter and terminator modules flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites, generating extensive diversity in gene expression profiles.

Key Steps:

Strain Construction:

- Replace the native promoter and terminator of each target pathway gene with a custom 5' Gene Expression Modulator (GEM) and 3' GEM module.

- The 5' GEM is an array of different upstream promoter elements separated by LoxPsym sites.

- The 3' GEM is an array of different terminator sequences separated by orthogonal LoxPsym sites (to prevent recombination with the 5' array).

- The expression of each gene is initially driven by the first promoter and terminator in each array.

Library Generation:

- Induce the expression of Cre recombinase in the engineered strain.

- Cre catalyzes inversion, deletion, duplication, and translocation events between the LoxPsym sites within each GEM module.

- This creates a vast library of strains, where each strain has a unique combination of promoters and terminators driving the expression of the pathway genes.

Screening and Selection:

- Screen the resulting library for high producers of the target compound.

- In the astaxanthin case, a single round of GEMbLeR created a library where gene expression varied over 120-fold and successfully doubled production titers [7].

Pathway Visualization and Engineering Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core engineering process of introducing and optimizing a heterologous pathway within a host's native metabolic network to achieve high-level production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Heterologous Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors & Platforms | P. pastoris vectors (pPICZ), E. coli plasmids (pET), S. cerevisiae integration vectors [1] | Stable maintenance and expression of heterologous genes in specific hosts. |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12, Cre-LoxP systems [6] [7] | Precise genome editing, gene knockout, and advanced functions like GEMbLeR-based shuffling [7]. |

| Expression Modulators | Constitutive & inducible promoters (PAOX1, PTEF1), synthetic terminator libraries, RBS variants [1] [7] | Fine-tuning the strength and regulation of gene expression for pathway balancing. |

| Computational & Modeling Tools | Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), OptFlux, QHEPath algorithm [8] [5] | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes, identification of bottlenecks, and design of engineering strategies. |

| Analytical Techniques | GC-MS, HPLC, Raman spectroscopy [6] [5] | Quantification of metabolites, tracking of isotopic labels (for flux analysis), and monitoring fermentation processes. |

For researchers and scientists in drug development and metabolic engineering, achieving efficient heterologous pathway expression is a fundamental objective. This process involves introducing foreign genetic material into a host organism to produce a target compound, such as a pharmaceutical ingredient or biofuel. However, this endeavor is frequently hampered by a set of interconnected biological challenges. This technical support center outlines the key challenges—toxicity, metabolic burden, and failed expression—and provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you navigate these complex issues within the context of optimizing gene expression levels.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Challenges

1. What are the primary causes of "strain degeneration" or loss of productivity in long-term fermentations? Strain degeneration is often driven by metabolic burden and the selection of non-productive subpopulations. Engineered strains experience metabolic stress due to the overexpression of synthetic pathways, which can lead to a decline in cellular fitness. Over time, this creates a selective pressure where non-productive mutant cells (revertants), which do not carry the metabolic load, outcompete the productive engineered cells [9].

2. Why do my heterologous pathways fail to express functional enzymes even after successful gene integration? Failed expression can stem from multiple factors, including:

- Transcriptional Inefficiency: The use of weak or unsuitable promoters that do not drive sufficient gene expression under your specific cultivation conditions [10].

- Post-Translational Limitations: Inefficient protein folding, lack of necessary post-translational modifications, or degradation by host proteases can prevent functional enzyme production. This is particularly relevant when expressing eukaryotic proteins in prokaryotic hosts or vice versa [1] [11].

3. How can I mitigate the toxicity of pathway intermediates or products? Toxic intermediates can halt production and kill cells. Strategies include:

- Dynamic Regulation: Implementing feedback genetic circuits that tie the production of the target compound to cell growth fitness. This "metabolic reward" system ensures that production only occurs when it benefits the cell, enhancing stability [9].

- Protein Engineering: Optimizing the secretory pathway in fungal hosts (e.g., Aspergillus niger) to rapidly export proteins, thereby reducing intracellular accumulation. This can involve engineering signal peptides, chaperones, and vesicle trafficking components [6] [11].

4. What practical steps can I take to reduce the metabolic burden on my host organism? Reducing metabolic burden is crucial for maintaining stability:

- Genomic Integration: Prefer stable genomic integration of pathway genes over plasmid-based systems, which require constant antibiotic selection and can be unstable [1] [11].

- Promoter and Pathway Optimization: Use strong, tailored promoters and balance the expression levels of all pathway enzymes to avoid bottlenecks and unnecessary energy expenditure [10] [12].

- Growth-Coupled Design: Design pathways where the production of the target compound is essential for the host's growth, creating a selective advantage for productive cells [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low or No Product Titer

Problem: Expected product is not detected, or titer is very low.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Gene Expression | Check transcript levels via RT-qPCR. Run SDS-PAGE to detect protein expression. | Codon-optimize genes. Test stronger or condition-specific promoters [10]. Verify plasmid stability or genomic integration. |

| Toxic Intermediate/Product | Monitor cell growth and morphology. Use analytics (e.g., LC-MS) to detect intermediate accumulation. | Implement a dynamic control circuit to decouple growth from production [9]. Engineer the host's tolerance via adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE). |

| Insufficient Precursor Supply | Analyze intracellular metabolite pools. Check growth and product yield with supplemented precursors. | Overexpress key precursor pathway genes (e.g., for tyrosine or malonyl-CoA) [12]. Knock out competing metabolic pathways. |

| Inefficient Secretion (for proteins) | Measure intracellular vs. extracellular protein concentration. | Engineer the secretory pathway (e.g., overexpress chaperones, optimize signal peptides) [6] [11]. Disrupt extracellular protease genes (e.g., PepA in A. niger) [11]. |

Guide 2: Managing Strain Instability and Loss of Productivity

Problem: Productivity declines significantly over multiple generations in batch or continuous culture.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | Measure the growth rate difference between engineered and wild-type strains. Use flow cytometry to detect non-producing subpopulations. | Use growth-coupled selection circuits [9]. Reduce the copy number of high-burden genes to an optimal level. Switch from a batch to a continuous reactor with controlled dilution rates [9]. |

| Genetic Instability | Sequence evolved, non-producing strains to identify common mutations. | Use stable genomic loci for integration. Employ genetic redundancy to protect critical pathway genes. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

Case Study: Stepwise Optimization of a Heterologous Pathway

Research on the de novo production of naringenin in E. coli provides an excellent template for systematic troubleshooting. The study achieved a high titer of 765.9 mg/L by optimizing each step of the pathway [12].

Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines the logical process for the step-by-step validation and optimization of a heterologous pathway, as demonstrated in the naringenin case study.

Quantitative Data from Enzyme Screening: Table: Performance of different enzyme combinations for Naringenin production in E. coli [12]

| Pathway Step | Enzyme Source (Gene) | Host Strain | Key Performance Indicator | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAL | Flavobacterium johnsoniae (FjTAL) | E. coli M-PAR-121 | p-Coumaric Acid Production | 2.54 g/L |

| 4CL & CHS | A. thaliana (At4CL) & C. maxima (CmCHS) | E. coli M-PAR-121 | Naringenin Chalcone Production | 560.2 mg/L |

| Full Pathway | FjTAL, At4CL, CmCHS, M. sativa (MsCHI) | E. coli M-PAR-121 | Final Naringenin Titer | 765.9 mg/L |

Protocol: Building a Low-Background Chassis inAspergillus niger

For high-yield protein expression, reducing background noise and enhancing secretion is critical. The following protocol is adapted from a study that created an efficient expression platform in the industrial strain A. niger AnN1 [11].

Methodology:

- Delete Background Genes: Use a CRISPR/Cas9-assisted marker recycling system to disrupt multiple copies of native high-expression genes (e.g., 13 out of 20 copies of the glucoamylase TeGlaA gene in strain AnN1).

- Knock Out Proteases: Disrupt major extracellular protease genes (e.g., PepA) to prevent degradation of the heterologous protein.

- Integrate Target Gene: Integrate your gene of interest into the newly vacated, transcriptionally active loci using a modular donor DNA plasmid with strong native promoters (e.g., AAmy promoter).

- Enhance Secretion (Optional): Further boost yield by overexpressing components of the vesicular trafficking system, such as the COPI component Cvc2, which was shown to increase production of a thermostable pectate lyase (MtPlyA) by 18% [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential reagents and strategies for troubleshooting pathway integration.

| Reagent / Strategy | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Enables precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and multiplexed editing. | Deleting native protease genes or integrating pathways into specific genomic loci in A. niger [6] [11]. |

| Growth-Coupled Feedback Circuits | Links cell survival or fitness to product formation, stabilizing production phenotypes. | Preventing strain degeneration in long-term fermentation of mevalonic acid-producing E. coli [9]. |

| Strong/Inducible Promoters | Provides high-level or conditional control of gene expression. | Using the SED1 or TDH3 promoters in S. cerevisiae to enhance xylanase expression on non-native substrates [10]. |

| Chassis Strains with Enhanced Precursor Supply | Host strains engineered to overproduce key metabolic precursors. | Using the tyrosine-overproducing E. coli M-PAR-121 strain to boost flux into the naringenin pathway [12]. |

| Secretory Pathway Components | Proteins involved in protein folding, vesicle transport, and secretion. | Overexpressing the COPI component Cvc2 in A. niger to improve heterologous protein secretion [11]. |

Pathway Dynamics and Stability

Understanding the population dynamics between productive and non-productive cells is vital for designing stable bioprocesses. The following diagram illustrates the core concept of how metabolic stress and reward circuits influence this competition.

Mathematical modeling of these dynamics reveals that in continuous reactors, the interplay between metabolic coupling strength and dilution rate is critical in determining whether productive cells dominate [9].

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a critical first step in the successful optimization of gene expression levels in heterologous pathways. Biological expression systems serve as fundamental tools for the production of recombinant proteins across industrial and medical fields, including the development of recombinant vaccines, therapeutic drugs, and agricultural products [13]. Researchers commonly utilize both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells to overcome challenges associated with recombinant protein production, with each system offering distinct advantages and limitations [13]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of four principal host systems: Escherichia coli (prokaryotic), Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris (eukaryotic yeasts), and filamentous fungi (eukaryotic). The guidance presented herein is specifically framed within the context of optimizing heterologous pathway research, with troubleshooting protocols designed to address common experimental challenges encountered by researchers and drug development professionals.

Organism-Specific Expression Characteristics

Comparative Analysis of Host System Attributes

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary host organisms used in heterologous protein expression, providing researchers with essential data for initial system selection.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Host Expression Systems

| Characteristic | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Pichia pastoris | Filamentous Fungi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubling Time | 30 minutes [13] | 90-120 minutes | 60-120 minutes [13] | 120-180 minutes |

| Cost of Growth Medium | Low [13] | Low | Low [13] | Low to Moderate |

| Expression Level | High [13] | Low to Moderate | Low to High [13] | Moderate to High |

| Extracellular Expression | Secretion to periplasm [13] | Secretion to medium | Secretion to medium [13] | High secretion capability |

| Protein Folding | Refolding usually required [13] | Generally proper | Proper folding [13] | Generally proper |

| N-Linked Glycosylation | None [13] | High mannose, hyperglycosylation | High mannose [13] | Complex, heterogeneous |

| O-Linked Glycosylation | No [13] | Yes | Yes [13] | Yes |

| Phosphorylation & Acetylation | No [13] | Yes | Yes [13] | Yes |

| Primary Drawbacks | Endotoxin contamination, misfolding, no PTMs [13] | Hyperglycosylation, secretion limitations | Codon bias, methanol requirement [13] | Complex genetics, high protease activity |

Experimental Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision-making process for selecting an appropriate host organism based on protein characteristics and experimental goals.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

General Gene Expression Troubleshooting

Table 2: General Gene Expression Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| No amplification in qPCR | Inhibitors present, low expression levels, primer issues [14] | Dilute template, check RNA quality, redesign primers, use positive control | Verify RNA integrity, test primer efficiency, include controls |

| Amplification in NTC | Contamination, primer-dimer formation [14] | Use fresh reagents, UV-treat workspace, redesign primers | Separate pre- and post-PCR areas, use filter tips |

| Poor PCR efficiency (slope < -3.6) | Primer issues, inhibitor presence, suboptimal reaction conditions [14] | Redesign primers, purify template, optimize Mg²⁺ concentration | Validate primer specificity, use high-quality reagents |

| Non-sigmoidal amplification curves | Incorrect baseline setting, high background fluorescence [14] | Set manual baseline, check for fluorescent contaminants | Validate instrument calibration, use appropriate reporter dyes |

| High Ct values | Low template concentration, inefficient amplification [14] | Concentrate template, optimize reaction conditions | Verify template quantification, use high-efficiency master mix |

Q1: Why am I seeing amplification in my no-template control (NTC) reactions?

A: Amplification in NTC reactions typically indicates contamination of your reaction components with template DNA or amplicon carryover. This problem can also result from primer-dimer formation. We recommend using fresh aliquots of all reagents, implementing UV irradiation of workspaces and equipment, and redesigning primers if dimerization is suspected. For TaqMan Gene Expression assays, we guarantee that assays run in NTC reactions will not produce detectable amplification signal (Ct > 38) when contamination is not present [14].

Q2: How do I address poor PCR efficiency when validating expression levels?

A: PCR efficiency should ideally be between 90% and 100% (-3.6 ≥ slope ≥ -3.3). If the efficiency is 100%, the Ct values of a 10-fold dilution series will be 3.3 cycles apart. For poor efficiency, consider primer redesign to avoid secondary structures, template purification to remove inhibitors, and optimization of Mg²⁺ concentration and annealing temperature. Slope values below -3.6 indicate poor efficiency that requires troubleshooting [14].

Q3: What endogenous controls should I use for my heterologous expression system?

A: For proper normalization in gene expression studies, we recommend performing a literature search in PubMed for your specific host organism and target gene to identify what other researchers use as endogenous controls. You can also screen for potential endogenous controls by ordering organism-specific endogenous control array plates if available. These plates are pre-plated with multiple endogenous control genes in triplicates on a 96-well plate format for systematic validation [14].

Pichia pastoris Optimization

Q4: How do I optimize methanol induction conditions for Pichia pastoris?

A: Methanol concentration, temperature, and induction time must be empirically optimized for each recombinant protein and strain. Key parameters to optimize include: methanol concentration (typically 0.5-1.0%), induction temperature (often reduced to 20-30°C), and induction duration (1-5 days). The optimal conditions differ according to the target protein and host strain characteristics [13]. For MutS strains (like KM71), remember that growth on methanol is slower, requiring longer induction periods compared to Mut+ strains.

Q5: What are the key advantages of using Pichia pastoris for heterologous expression?

A: The Pichia pastoris expression system offers several significant advantages: (1) appropriate folding in the endoplasmic reticulum; (2) secretion of recombinant proteins to the external environment of the cell using Kex2 as signal peptidase; (3) limited production of endogenous secretory proteins, simplifying purification; (4) post-translational modifications including O- and N-linked glycosylation and disulfide bond formation; and (5) high similarity of glycosylation to mammalian cells [13]. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for production of subunit vaccines and therapeutic proteins.

E. coli-Specific Issues

Q6: How can I address protein misfolding and inclusion body formation in E. coli?

A: When encountering misfolding and inclusion body formation: (1) Reduce expression temperature (25-30°C) to slow protein synthesis and favor proper folding; (2) Use lower inducer concentrations (e.g., 0.1-0.5 mM IPTG); (3) Employ fusion tags (MBP, Trx, GST) that enhance solubility; (4) Co-express molecular chaperones (GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE); (5) Switch to engineered strains specifically designed for disulfide bond formation (Origami) or enhanced folding (ArcticExpress). For proteins requiring refolding, systematic screening of refolding buffers is essential.

Eukaryotic Host Challenges

Q7: How do I address hyperglycosylation issues in S. cerevisiae?

A: S. cerevisiae often produces N- and O-hyperglycosylated proteins, which may affect immunogenicity and function. To address this: (1) Consider using glycoengineered yeast strains (e.g., Δoch1) that produce humanized glycosylation patterns; (2) Introduce specific glycosylation sites via mutagenesis to control attachment; (3) Utilize in vitro deglycosylation enzymes post-purification; (4) Switch to alternative yeast systems like P. pastoris that typically produce less extensive glycosylation [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous Expression Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Host Compatibility | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Quantitative RT-PCR for expression validation [14] | All systems | Verify no amplification in NTC (Ct > 38) [14] |

| Methanol (HPLC grade) | Inducer for AOX1 promoter in P. pastoris [13] | P. pastoris | Optimize concentration (0.5-1.0%) for each strain [13] |

| Sorbitol | Co-substrate for P. pastoris growth & induction | P. pastoris | Can improve viability during methanol induction |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent recombinant protein degradation | All eukaryotic systems | Essential for secretion-deficient strains |

| Signal Peptides (e.g., α-factor) | Direct secretory expression | Yeast systems | Kex2 cleavage site required for processing [13] |

| Antibiotics for Selection | Maintain expression plasmids | All systems | Use organism-specific antibiotics (zeocin, G418) |

| Chromogenic Substrates | Detect enzyme expression & activity | All systems | Enables rapid screening of expression clones |

| Endogenous Control Panels | qPCR normalization genes [14] | All systems | Pre-validated controls for accurate normalization [14] |

Advanced Methodologies

CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Optimization

Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas technology have revolutionized genetic engineering in various host organisms. The CRISPR/Cas system provides precise, versatile, and efficient methods for targeted genome editing [15]. The system has evolved from its origins as a prokaryotic immune defense mechanism into a highly programmable nuclease platform [15]. For expression optimization, CRISPR/Cas enables targeted integration of expression cassettes into genomic hot spots, precise promoter engineering to modulate expression levels, and multiplexed gene disruptions to eliminate proteases or redirect metabolic flux.

The development of high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, HypaCas9) addresses off-target concerns, while Cas12 systems with different PAM requirements (recognizing T-rich regions) expand targeting flexibility [15]. Catalytically impaired derivatives (nCas9 and dCas9) enable more subtle modulation through base editing, prime editing, and transcriptional regulation without permanent DNA cleavage [15]. These advanced tools are particularly valuable for optimizing heterologous pathways by fine-tuning the expression of multiple genes simultaneously.

Experimental Pathway for Strain Engineering

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for CRISPR-mediated optimization of host organisms for enhanced heterologous expression.

Quantitative Expression Analysis Protocol

For accurate quantification of heterologous expression levels, follow this detailed qRT-PCR protocol:

- RNA Extraction: Use high-quality, RNase-free reagents for RNA isolation. Include DNase I treatment to eliminate genomic DNA contamination.

- Reverse Transcription: Perform cDNA synthesis using random hexamers and reverse transcriptase with RNase inhibitor. Include a no-RT control for each sample.

- qPCR Setup: Use validated gene-specific primers or TaqMan assays. Ensure PCR efficiency is between 90-100% (slope of -3.6 to -3.3) [14]. Include no-template controls (NTC) and positive controls in each run.

- Data Analysis: Calculate Ct values using appropriate baseline and threshold settings. For absolute quantification, use a standard curve with known template concentrations. For relative quantification, use the ΔΔCt method with validated endogenous controls [14].

- Normalization: Use geometric averaging of multiple endogenous controls when possible, as this approach provides more reliable normalization than single reference genes [14].

For data analysis software, tools like DataAssist or ExpressionSuite can generate p-values from ΔΔCt data once biological groups are assigned with at least 2 samples in each group [14]. These tools also support analysis using multiple endogenous controls or global normalization, which is particularly useful when studying large numbers of targets [14].

The Role of Computational Models and Retrosynthetic Algorithms in Pathway Design

The engineering of microbes to produce valuable chemicals, from pharmaceuticals to biofuels, hinges on the effective design and implementation of heterologous biosynthetic pathways. A central challenge in this field is optimizing gene expression levels to balance metabolic flux, maximize product yield, and maintain host cell fitness. Computational models and retrosynthetic algorithms have become indispensable for navigating the vast design space of potential pathways and expression parameters. This technical support center provides a foundational guide for researchers tackling the experimental hurdles that arise when moving from computational predictions to a functional, optimized pathway in the lab. The following sections offer troubleshooting guides, detailed protocols, and key resources to directly address specific issues encountered during these experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Databases and Reagents

A successful pathway engineering project relies on a foundation of high-quality data and molecular tools. The tables below summarize key resources for computational design and experimental optimization.

Table 1: Key Biological Databases for Pathway Design

| Data Category | Database Name | Primary Function | Website URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | PubChem [16] | Repository of chemical structures, properties, and biological activities | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| ChEBI [16] | Focused database of small molecular entities | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chebi/ | |

| Reactions/Pathways | KEGG [16] | Integrated database of pathways, diseases, drugs, and organisms | https://www.kegg.jp/ |

| MetaCyc [16] | Database of metabolic pathways and enzymes across species | https://metacyc.org/ | |

| Rhea [16] | Curated resource of biochemical reactions | https://www.rhea-db.org/ | |

| Enzymes | BRENDA [16] | Comprehensive enzyme information database | https://brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| UniProt [16] | Central hub for protein sequence and functional data | https://www.uniprot.org/ | |

| AlphaFold DB [16] | Database of highly accurate predicted protein structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Expression Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| LoxPsym Sites [7] | Enables Cre-mediated recombination for promoter/terminator shuffling. | Creating diverse expression libraries in the GEMbLeR system. |

| Cre Recombinase [7] | Executes site-specific recombination at LoxPsym sites. | Inducing genomic rearrangements in vivo to generate strain diversity. |

| Heterologous GEM Arrays [7] | Provides a library of promoter and terminator parts of varying strengths. | Systematically tuning the expression level of a pathway gene. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [17] | Enables precise genomic edits, deletions, and integrations. | Disrupting endogenous protease genes (e.g., PepA in A. niger) to reduce background protein secretion [17]. |

Computational Workflow and Experimental Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for designing and optimizing a heterologous biosynthetic pathway, from initial target selection to a high-titer production strain.

Diagram 1: Integrated pathway design and optimization workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How do I balance expression of multiple genes in a heterologous pathway?

Issue: Unbalanced expression leads to low product yield, accumulation of toxic intermediates, and reduced host fitness.

Solution: Employ combinatorial, in vivo methods to generate and screen large libraries of expression variants.

- Recommended Tool: GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) in yeast [7].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Construct Design: For each gene in your pathway, replace its native promoter and terminator with a 5' GEM array (containing multiple upstream promoter elements) and a 3' GEM array (containing multiple terminators), respectively. Each part within an array is flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites to prevent cross-recombination between arrays [7].

- Strain Generation: Integrate these GEM-constructs for all pathway genes into your host chassis strain.

- Library Induction: Introduce and induce Cre recombinase expression. This will stochastically shuffle the promoter and terminator parts within their respective arrays for each gene, creating a vast library of strains with unique expression profiles for the entire pathway [7].

- Screening & Selection: Screen the library for high product titers, for example, using colorimetric assays for pigments like astaxanthin or high-throughput chromatography. A single round of GEMbLeR has been shown to double astaxanthin production titers [7].

FAQ 2: My computationally designed pathway is not stoichiometrically feasible in the host. What should I check?

Issue: Linear pathway designs often fail because they do not account for cofactor balancing, energy demands, or connections to the host's native metabolism.

Solution: Use advanced pathway finding algorithms that extract balanced, stoichiometrically feasible subnetworks.

- Recommended Tool: SubNetX algorithm [18].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Cofactor Balancing: Ensure the proposed pathway does not rely on cofactors not natively produced by your host (e.g., tetrahydrobiopterin in E. coli). Use SubNetX in a search mode that avoids non-native cofactors to force the algorithm to find alternatives [18].

- Check Energy and Redox Balance: The algorithm should integrate the subnetwork into a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., of E. coli) and use constraint-based optimization (like Flux Balance Analysis) to verify the pathway can produce the target while sustaining growth [18] [19].

- Expand Reaction Databases: If a pathway is incomplete, supplement known reaction databases (e.g., ARBRE) with larger databases of predicted reactions (e.g., ATLASx) to fill in missing gaps and connect the target to host metabolites [18].

FAQ 3: How can I find a viable enzymatic step for a non-natural or orphan reaction?

Issue: A key reaction in your planned pathway has no known or efficient natural enzyme.

Solution: Leverage AI-driven tools for enzyme discovery and de novo design.

- Recommended Tools: Retrosynthesis algorithms (DeepRetro) combined with structure prediction tools (AlphaFold) [16] [20] [21].

- Action Plan:

- Identify Candidate Reactions: Use a retrosynthesis framework like DeepRetro, which integrates large language models (LLMs) with traditional biochemical knowledge, to propose plausible novel reactions and disconnections for your target [21].

- Discover Enzyme Templates: Search enzyme databases (BRENDA, UniProt) using the reaction SMILES or molecular similarity of substrates/products. AI-based functional annotation tools can suggest known enzymes that might catalyze similar reactions [16] [20].

- Model and Engineer: Use the predicted protein structures from AlphaFold DB to model the binding of your non-natural substrate into a candidate enzyme's active site. This guides rational engineering or de novo design of an enzyme with the desired activity [16] [20].

FAQ 4: My model predicts high yield, but I observe low production and high metabolic burden.

Issue: The objective function in the computational model does not reflect the true physiological state of the engineered host.

Solution: Refine your metabolic model to better capture the host's adaptive responses.

- Recommended Tool: TIObjFind framework, which integrates Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) [19].

- Procedure:

- Incorporate Experimental Data: Collect experimental flux data (e.g., from isotopologue profiling) or product secretion rates from your struggling strain.

- Re-calibrate the Objective: Use the TIObjFind framework to determine a context-specific objective function. It calculates "Coefficients of Importance" for reactions, identifying which metabolic goals the cell is actually prioritizing (e.g., stress response over production) [19].

- Re-run Simulation: Perform FBA with the newly identified objective function to generate flux predictions that are more aligned with your experimental data. This can reveal hidden bottlenecks, such as unexpected cofactor limitations or conflicts with native metabolic fluxes [19].

Considerations for Metabolic Network Balance and Cofactor Availability

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my heterologous pathway producing the target metabolite at very low yields, even though all genes express successfully?

Problem: Low productivity despite successful gene expression often stems from an imbalanced metabolic network where the heterologous pathway drains essential precursors or cofactors, disrupting the host's core metabolism.

Diagnosis & Solution:

- Diagnostic Method: Use Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to quantify flux through central carbon pathways (e.g., glycolysis, TCA cycle). Compare flux distributions between your engineered strain and the wild-type host. A significant redirection of flux or accumulation of certain intermediates indicates a bottleneck or imbalance [22] [23].

- Solution: Implement dynamic regulatory circuits to decouple growth from production. Instead of constitutive expression, use promoters induced after the growth phase. This prevents the heterologous pathway from overwhelming central metabolism during rapid growth [23].

FAQ 2: How can I identify which specific cofactor or precursor is limiting production in my engineered pathway?

Problem: Unknown cofactor or precursor limitations create metabolic bottlenecks that are difficult to pinpoint.

Diagnosis & Solution:

- Diagnostic Method: Employ Metabolic Tracing with stable isotopes (e.g., 13C-glucose). Track the incorporation of labeled atoms into your target metabolite and key pathway intermediates. This reveals flux and identifies steps where metabolites pool or labels are lost, indicating a bottleneck [24] [25].

- Solution: If tracing shows a drain on energy cofactors, engineer a heterologous NADPH regeneration pathway. Replacing the native E. coli glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) with a NADP-dependent enzyme from Clostridium acetobutylicum has been shown to increase NADPH supply and enhance product synthesis [23].

FAQ 3: My pathway produces excessive byproducts (e.g., acetate or lactate). How do I reduce this carbon loss?

Problem: Overflow metabolism leads to byproduct formation, reducing carbon efficiency and yield.

Diagnosis & Solution:

- Diagnostic Method: Analyze extracellular metabolites (e.g., using HPLC or GC-MS) to quantify byproduct secretion. High byproduct levels often indicate an imbalance between glycolytic flux and the capacity of downstream pathways like the TCA cycle [23] [25].

- Solution: Knock out key byproduct-forming genes. Sequential deletion of poxB (pyruvate oxidase), pta-ackA (acetate kinase pathway), and ldhA (lactate dehydrogenase) in E. coli has been proven effective in reducing acetate and lactate formation, thereby redirecting carbon flux toward the desired product [23].

FAQ 4: How does the host organism's native metabolic network topology influence the success of my heterologous pathway?

Problem: The inherent structure of the host's metabolic network imposes constraints on heterologous pathway function.

Diagnosis & Solution:

- Diagnostic Principle: Recognize that enzymes in highly connected, central parts of the metabolic network (e.g., TCA cycle) evolve under greater constraints and carry high metabolic flux. Introducing a heterologous pathway that interacts with these central nodes is more likely to cause toxicity or require extensive optimization [22].

- Solution: When possible, design pathways that utilize precursors from less central, peripheral metabolic pathways to minimize interference with core metabolism. Computational models can help predict the availability of precursors and the thermodynamic feasibility of the integrated pathway [1] [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metabolic Flux Analysis using 13C-Metabolic Tracing

Purpose: To quantitatively track the activity of metabolic pathways and identify bottlenecks in your engineered strain [24] [25].

Workflow:

Key Considerations:

- Tracer Selection: The labeled atom must be retained through the pathways of interest. For central carbon metabolism, U-13C glucose (uniformly labeled) is common [24].

- Time Points: Harvest at multiple time points (seconds to hours) to capture pathway kinetics. Fast metabolic pathways require rapid sampling [24].

- Data Analysis: Use specialized software (e.g., INCA, IsoCor) to interpret mass isotopomer distributions and calculate metabolic fluxes [25].

Protocol 2: Systematic Troubleshooting of Cofactor Imbalance

Purpose: To diagnose and resolve limitations in cofactor supply (NADPH, ATP) that restrict pathway performance [23].

Workflow:

Key Considerations:

- Measurement: Quantify intracellular cofactor ratios using enzymatic assays or targeted LC-MS/MS.

- Auxotrophic Test: If the heterologous pathway produces a cofactor precursor (e.g., D-pantothenic acid for CoA), test if it rescues the growth of a cofactor-auxotrophic mutant. This confirms functional integration [23].

- Engineering: Install heterologous, non-regulated enzymes for cofactor regeneration (e.g., NADP-dependent GAPDH for NADPH) to bypass native regulatory loops [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Network Analysis and Engineering.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Enables dynamic tracking of atom fate through metabolic pathways via Mass Spectrometry [24] [25]. | U-13C-Glucose; 2H- or 15N-labeled compounds. Critical for Metabolic Flux Analysis. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Software | In silico prediction of metabolic flux distributions and identification of optimization targets [22]. | COBRA Toolbox (Matlab), Pathway Tools. Requires a genome-scale metabolic model. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Enables temporal control over gene expression, allowing separation of growth and production phases [1] [23]. | PAOX1 (methanol-induced in P. pastoris), L-rhamnose-inducible promoters in E. coli. |

| Heterologous Cofactor Enzymes | Replaces native enzymes to alter cofactor specificity and alleviate redox/energy limitations [23]. | NADP-dependent GAPDH from C. acetobutylicum; water-forming NADH oxidases. |

| Gene Knockout Tools | Eliminates competitive pathways that divert carbon and energy to unwanted byproducts [23]. | CRISPR-Cas9 for precise deletions; used to remove acetate, lactate, or ethanol formation genes. |

| Quorum Sensing Circuits | Enables dynamic, population-density-dependent regulation of pathway genes to maintain metabolic homeostasis [23]. | AHL-based systems (e.g., LuxI/LuxR) to activate expression only after high cell density is achieved. |

Advanced Strategies for Codon Optimization and Transcriptional Control

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is condition-specific codon optimization, and how does it fundamentally differ from traditional methods like the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI)?

Traditional codon optimization tools often rely on static, genome-wide metrics like the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI), which selects codons based on their overall frequency in the host organism's highly expressed genes [26]. In contrast, condition-specific codon optimization is a dynamic strategy that designs codon sequences based on the codon usage bias of genes that are highly expressed under a specific physiological or environmental condition relevant to your experiment [27]. This is critical because factors like tRNA abundance and availability can shift with changes in the environment, growth phase, or cell type [27]. While traditional CAI-based optimization can sometimes improve expression, it does not guarantee success and may even reduce expression in over 30% of cases [27]. Condition-specific optimization accounts for the actual translational machinery state in your specific experimental context, leading to more reliable and robust protein expression.

FAQ 2: My CAI-optimized gene is not expressing well in my fermentation process. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue that highlights the limitation of traditional optimization. Your fermentation conditions (e.g., specific carbon sources, dissolved oxygen, pH, or the stationary growth phase) create a unique cellular environment. The tRNA pool under these conditions likely differs from the "average" tRNA pool assumed by CAI [27]. A CAI-optimized gene might use codons that correspond to scarce tRNAs in your specific fermentation setup, causing ribosomal stalling and reduced yield. To troubleshoot:

- Analyze your condition: Identify the specific growth condition (e.g., high cell density, stationary phase) where expression is low.

- Re-optimize for the condition: Generate a new codon usage bias matrix using highly expressed genes from RNA-seq data of your host organism under the same or similar fermentation conditions. Use this matrix for a condition-specific re-design of your gene [27]. One study achieved a 2.9-fold improvement in enzyme activity by optimizing for stationary phase production in S. cerevisiae, significantly outperforming a commercial CAI-based tool [27].

FAQ 3: What are the key technical challenges in implementing a condition-specific optimization strategy?

The primary challenge is obtaining high-quality, condition-specific biological data to inform the optimization model.

- Data Dependency: The method requires genomic-scale expression data (e.g., RNA-seq) for your host organism under the precise condition of interest [27]. For novel conditions or non-model hosts, this data may not be publicly available and must be generated in-house.

- Computational Complexity: Building a custom codon bias matrix and designing sequences probabilistically is more complex than running a standard CAI-based algorithm [27].

- Multi-gene Pathway Balancing: When optimizing multiple genes in a pathway, using the same set of optimal codons can lead to competition for the same charged tRNAs, creating a new bottleneck. It is crucial to use a probabilistic design algorithm that generates a balance of synonymous codons rather than exclusively using the single "best" codon for each amino acid [27].

FAQ 4: How do AI and deep learning models advance condition-specific optimization?

Deep learning frameworks represent a significant leap forward. They move beyond simple codon frequency by directly learning the complex relationship between mRNA sequence features and translational efficiency from large-scale experimental data.

- Direct Learning from Translation Data: Models like RiboDecode are trained on ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) data, which provides a genome-wide snapshot of actively translating ribosomes [28]. This allows the model to learn codon usage patterns that directly correlate with high translation efficiency, not just mRNA abundance.

- Integration of Cellular Context: Advanced models can integrate multiple inputs, including the mRNA codon sequence, mRNA abundance data from RNA-seq, and even gene expression profiles that represent the cellular state [28]. This creates a truly context-aware optimization system.

- Exploration of Vast Sequence Space: Using generative AI and gradient ascent, these models can explore a much larger space of synonymous codon sequences than rule-based methods, discovering novel, highly efficient sequences that were previously inaccessible [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Heterologous Protein Yield in a Specific Host Strain or Culture Condition

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low protein yield in stationary phase, but good yield in log phase. | tRNA pool has shifted in stationary phase, making the optimized sequence suboptimal. | Generate a condition-specific codon usage table using highly expressed genes from stationary phase RNA-seq data. Re-design the gene using this table. | Compare protein activity/yield of the new construct vs. the original in stationary phase. |

| High expression of a single gene, but poor expression when multiple optimized genes are co-expressed in a pathway. | tRNA pool depletion due to multiple genes competing for the same "optimal" tRNAs. | Use a probabilistic optimization algorithm that generates a balanced use of synonymous codons to avoid overloading specific tRNAs [27]. | Measure expression of all pathway genes simultaneously and assay final product titer. |

| Poor protein expression in a non-model fungal host. | Standard codon tables do not reflect the host's true codon bias under industrial conditions. | Use a deep learning tool like FUN-PROSE, trained on fungal promoters and expression data, to predict and optimize expression for your specific host and condition [29]. | Quantify mRNA levels and protein output of the optimized construct. |

Problem: Inefficient mRNA Translation Despite High mRNA Levels

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong mRNA signal from qPCR/RNA-seq, but low protein detection. | Suboptimal codon usage is causing slow translation elongation and ribosome stalling. | Employ a translation-centric optimization tool like RiboDecode that is trained on Ribo-seq data to maximize ribosome occupancy and translation efficiency [28]. | Perform ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) to visualize ribosome occupancy on the mRNA. |

| mRNA is degraded rapidly. | Synonymous codon changes have inadvertently created unstable mRNA secondary structures or regulatory motifs. | Use an optimizer that jointly considers translation and mRNA stability (e.g., minimum free energy - MFE). Ensure the optimization algorithm includes mRNA structure prediction in its cost function [28]. | Measure mRNA half-life (e.g., using transcriptional inhibition assays). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Condition-Specific Codon Optimization for a Heterologous Gene in Yeast

This protocol outlines a method to optimize a gene for expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under a specific condition (e.g., high xylose concentration) using a condition-specific codon bias matrix [27].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Host Strain: Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C or other relevant industrial strain.

- Condition-Specific Expression Data: RNA-seq dataset (e.g., from GEO under accession GSE208095) of the host strain growing under the target condition [26].

- Software Tools: Python scripts for generating codon bias matrices and probabilistic gene design (e.g.,

CodonUsageAnalysisandGeneDesign) [27]. - Synthesis & Cloning: Service for gene synthesis and cloning into an appropriate expression vector for yeast.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Obtain RNA-seq data for S. cerevisiae cultivated under your target condition (e.g., high xylose) and a relevant control condition.

- Identify the set of genes that are significantly up-regulated or highly expressed under the target condition. This can be done using differential expression analysis tools (e.g., in R/Bioconductor).

Generate Condition-Specific Codon Bias Matrix:

- Using the

CodonUsageAnalysisscript, extract the coding sequences (CDS) of the highly expressed gene set. - Calculate codon frequencies and, critically, codon-pair (di-codon) frequencies from these CDS. The output is a 61x61 matrix representing the probability of each codon pair occurring in the expressed genes for that condition.

- Using the

Probabilistic Gene Design:

- Input the amino acid sequence of your target heterologous gene into the

GeneDesignscript. - The script will use the condition-specific codon bias matrix to probabilistically reconstruct the DNA sequence. For each amino acid pair in the sequence, it selects a codon pair based on the probabilities in the matrix.

- Run the script multiple times to generate several (e.g., 5-10) candidate DNA sequences that follow the same codon context rules.

- Input the amino acid sequence of your target heterologous gene into the

Synthesis, Transformation, and Validation:

- Synthesize the top candidate genes and clone them into your expression vector.

- Transform the constructs into your S. cerevisiae host strain and cultivate under the target condition.

- Validate using functional assays (e.g., enzyme activity, fluorescence) to identify the highest-performing variant.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Utilizing a Deep Learning Framework (RiboDecode) for mRNA Therapeutics Optimization

This protocol describes the use of the RiboDecode deep learning framework to optimize mRNA sequences for enhanced translation and therapeutic efficacy [28].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software Framework: RiboDecode deep learning model.

- Training Data: Paired Ribo-seq and RNA-seq datasets from relevant human tissues or cell lines (e.g., from 24 different human tissues/cell lines) [28].

- In vitro/In vivo Models: For validation (e.g., cell-based protein expression assays, mouse models for antibody response or therapeutic efficacy).

Methodology:

- Model Input and Goal Setting:

- Input the wild-type codon sequence of your target therapeutic protein (e.g., influenza hemagglutinin (HA) or nerve growth factor (NGF)).

- Define the optimization goal by setting the parameter

w(wherew=0optimizes for translation only,w=1for mRNA stability/Minimum Free Energy only, and0<w<1for a joint optimization) [28].

Generative Sequence Optimization:

- The RiboDecode optimizer begins with the original sequence and uses a gradient ascent approach (activation maximization) to iteratively adjust the codon distribution.

- A synonymous codon regularizer ensures all changes are synonymous, preserving the amino acid sequence.

- In each cycle, the sequence is fed into the prediction models, which output a fitness score. The optimizer adjusts codons to maximize this score over multiple iterations, exploring a vast sequence space.

Output and Experimental Validation:

- The output is one or more optimized mRNA codon sequences predicted to have high translation efficiency and/or stability.

- Validate the optimized mRNAs in vitro by transferring cells and measuring protein expression levels via Western blot or ELISA, comparing against the wild-type sequence and sequences from other methods (e.g., LinearDesign).

- Proceed to in vivo validation. For vaccines, immunize mice and measure neutralizing antibody responses. For therapeutic proteins like NGF, test efficacy in a disease model (e.g., optic nerve crush model) at different dose levels.

The structure of the RiboDecode framework is visualized below:

Performance Data Tables

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Condition-Specific vs. Traditional Optimization

| Optimized Gene / System | Optimization Method | Host / Condition | Key Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechol 1,2-dioxygenase (CatA) | Condition-specific (stationary phase) | S. cerevisiae / Stationary phase | ~2.9-fold higher enzyme activity vs. commercial algorithm | [27] |

| Influenza HA mRNA | RiboDecode (AI-based) | Mice / Vaccination | ~10x stronger neutralizing antibody response vs. unoptimized | [28] |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) mRNA | RiboDecode (AI-based) | Mice / Neuroprotection | Equivalent neuroprotection at 1/5 the dose vs. unoptimized | [28] |

| Astaxanthin Pathway | GEMbLeR (Promoter/Terminator Shuffling) | S. cerevisiae | >2-fold increase in production titer | [7] |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Codon Optimization Effectiveness

| Metric | Description | Application & Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | Measures the similarity of a gene's codon usage to the usage in highly expressed host genes. | Simple, widely used. Limited by its static, condition-agnostic nature [26]. |

| tRNA Adaptation Index (tAI) | Estimates translation efficiency based on the correspondence between codon usage and tRNA gene copy numbers. | More mechanistic than CAI, but still assumes a static tRNA pool [30]. |

| Minimum Free Energy (MFE) | Predicts the stability of mRNA secondary structure. Lower MFE often correlates with better translation. | Crucial for mRNA therapeutics. Can be jointly optimized with translation efficiency [28]. |

| Codon-Pair Bias (CPB) | Measures the frequency of adjacent codon pairs (di-codons) compared to random expectation. | Can influence translation elongation rate and accuracy. Condition-specific matrices are most effective [27]. |

Incorporating Codon Context and Di-codon Usage for Improved Translational Efficiency

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Codon Usage and Heterologous Expression

This guide addresses common experimental challenges faced when optimizing heterologous pathways, providing targeted solutions based on the latest research.

FAQ 1: My heterologous protein expresses poorly in the new host despite a high Codon Adaptation Index (CAI). What could be wrong?

- Problem: A high CAI indicates good alignment with the host's overall codon preferences but does not account for codon context (di-codon usage) or other regulatory factors [26] [31]. Poor expression can result from non-optimal codon pairs, which can cause ribosome stalling and reduce efficiency, or from overlooked parameters like mRNA secondary structure [32] [28].

- Solution:

- Perform Multi-Parameter Analysis: Use analysis tools like GenRCA to evaluate a comprehensive set of over 30 Codon Usage Bias (CUB) indices, not just CAI [31]. No single index is universally best, and the most predictive metrics vary by species [31].

- Check Codon-Pair Bias (CPB): Analyze and optimize your sequence for host-preferred codon pairs. A negative CPB score indicates suboptimal pairing that can hinder translational efficiency and co-translational folding [32] [26].

- Evaluate mRNA Stability: Assess the minimum free energy (MFE) of mRNA secondary structures, particularly around the start codon, as stable structures can block translation initiation [28] [33].

FAQ 2: How can I diagnose if ribosome stalling due to rare codons or poor codon context is causing protein truncation or misfolding?

- Problem: Consecutive rare codons or negatively biased codon pairs can cause ribosome stalling. This leads to truncated proteins due to premature translation termination or misfolded proteins due to disrupted co-translational folding [32] [34].

- Solution:

- Rare Codon Analysis: Use tools like VectorBuilder's Rare Codon Analysis or GenRCA to identify clusters of rare codons in your sequence. A few dispersed rare codons may be tolerable, but clusters are particularly problematic [35] [34] [31].

- Experimental Validation with Ribosome Profiling: If available, ribosome profiling (Ribo-seq) can provide experimental evidence of ribosome stalling at specific positions in the coding sequence, directly linking sequence features to translation bottlenecks [32] [28].

- Host Strain Engineering: For bacterial expression, use engineered host strains that supply tRNAs for rare codons (e.g., Rosetta strains). This can alleviate stalling without the need for extensive sequence redesign [34].

FAQ 3: My codon-optimized gene expresses well in one cell line but poorly in another, despite the same species. Why?

- Problem: Traditional codon optimization often uses a single, genome-wide codon usage table. However, codon preference can be tissue-specific or cell line-specific due to variations in tRNA expression pools, a phenomenon known as "tRNA heterogeneity" [32] [28].

- Solution:

- Adopt Context-Aware Optimization: Use next-generation optimization tools like RiboDecode that can incorporate cell-specific data, such as transcriptome (RNA-seq) and translatome (Ribo-seq) data, to tailor the sequence to the specific translational machinery of your target cell line [28].

- Leverage Deep Learning Models: Frameworks like RiboDecode learn from large-scale datasets across multiple tissues and cell lines, enabling them to predict translation levels more accurately in specific cellular environments [28].

FAQ 4: After codon optimization, my protein is expressed at high levels but is inactive. What steps should I take?

- Problem: While optimizing for speed, the algorithm may have disrupted regions critical for co-translational folding. If the ribosome moves too quickly through a segment that requires pause for proper folding, the protein can misfold and lose function, even if the amino acid sequence is correct [32].

- Solution:

- Introduce Strategic Pauses: Re-introduce specific, non-optimal codon pairs at positions known to be critical for functional folding. These pauses give the nascent polypeptide chain time to form correct secondary and tertiary structures [32].

- Analyze Codon Context Fitness: Ensure the optimization tool considers codon context (CC). The fitness of codon pairs can be calculated and optimized to mimic the patterns found in highly expressed native proteins [26].

- Refold or Co-Express Chaperones: In vitro, attempt to denature and refold the protein. In vivo, co-express molecular chaperones to assist with the folding process [33].

Key Parameters for Effective Codon Optimization

The following table summarizes critical parameters to analyze and optimize for improved heterologous expression, moving beyond simple CAI.

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for Codon Optimization

| Parameter | Description | Role in Translational Efficiency | Optimal Range (Varies by Host) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | Measures the similarity of a gene's codon usage to the preferred usage of highly expressed genes in the host organism [36]. | High CAI generally correlates with high expression potential, but is not sufficient alone [26] [31]. | >0.8 is considered good, closer to 1.0 is ideal [35]. |

| Codon Context (CC) / Codon-Pair Bias (CPB) | The non-random occurrence of pairs of adjacent codons; measured by CC fitness or CPB score [26]. | Optimal codon-pairs facilitate smoother ribosome movement and accurate translation, reducing stalling and errors [32] [26]. | Varies by host. Aim for a CC/CPB distribution that matches highly expressed host genes. |

| GC Content | The percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA/RNA sequence that are guanine or cytosine. | Affects mRNA stability and secondary structure; extremes can be detrimental to transcription and translation [35] [26]. | Typically 30-70%, with organism-specific ideals (e.g., ~60% for human cells, lower for E. coli) [35] [26]. |

| mRNA Secondary Structure (ΔG) | The stability of folded mRNA, measured by Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG); often predicted by Minimum Free Energy (MFE) [28] [26]. | Stable structures near the 5' end can inhibit ribosome binding and initiation; internal structures can slow elongation. | Weaker structures (less negative ΔG) around the start codon are generally preferred [28] [33]. |

| Effective Number of Codons (ENC) | Measures the deviation from random codon usage, indicating the bias strength [31]. | A low ENC indicates strong bias, typical of highly expressed genes. | Ranges from 20 (extreme bias) to 61 (no bias). Values below 35 often indicate strong bias. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Comprehensive Codon Optimization

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for analyzing and optimizing coding sequences for heterologous expression, incorporating codon context.

Step 1: Initial Sequence Analysis

- Input Sequence: Start with your protein's amino acid sequence or native DNA coding sequence.

- Baseline Assessment: Use a comprehensive analysis tool like GenRCA [31] with your target host organism selected.

- Generate Report: Calculate all major CUB indices, including CAI, ENC, and GC content. Pay special attention to the "rare codon heatmap" to identify clusters of problematic codons.

Step 2: Multi-Factor Optimization

- Select an Advanced Tool: Choose an optimization tool that incorporates multiple parameters. Examples from a recent comparative study include GeneOptimizer and ATGme, which showed strong performance by integrating several design criteria [26]. For therapeutic mRNA design, RiboDecode is a state-of-the-art deep learning framework [28].

- Set Parameters: Configure the optimizer to:

- Maximize CAI.

- Optimize GC content to the host's preferred range.

- Minimize stable mRNA secondary structures, especially near the start codon.

- Enable codon context or codon-pair bias optimization where available.

- Avoid specific sequence motifs (e.g., restriction sites, cryptic splice sites, internal polyA signals) [35] [26].

Step 3: In Silico Validation of the Optimized Sequence

- Re-analyze the Output: Run the newly generated optimized sequence through GenRCA again.

- Compare Metrics: Ensure that the CAI is high, GC content is appropriate, and the number of rare codons is minimized. Verify that the codon context fitness has improved compared to the original sequence.

- Predict mRNA Structure: Use tools like RNAfold to check that the 5' end of the optimized mRNA does not form stable secondary structures that could impede initiation [26].

Step 4: Cloning and Experimental Expression

- Gene Synthesis: The optimized sequence is typically synthesized de novo due to the extensive synonymous changes.

- Cloning: Clone the synthesized gene into your expression vector.

- Pilot Expression Test: Follow a standard protein expression troubleshooting guide [34]:

- Transform the plasmid into an appropriate expression host.

- Induce expression and run a time-course experiment.

- Analyze total protein and purified product via SDS-PAGE and Western blot to check for yield and full-length product.

- If Problems Persist: Revisit the troubleshooting FAQs above. Consider using a different host strain or further optimizing induction conditions (e.g., temperature, inducer concentration) [34].

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving codon-related expression issues, as detailed in the troubleshooting guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Codon Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Codon Analysis Tools | Provides quantitative assessment of codon usage bias and other sequence parameters. | GenRCA [31] (comprehensive, 31+ indices), VectorBuilder's tool [35] (user-friendly, CAI/GC focus), CodonExplorer [36] (theoretical analysis). |

| Advanced Codon Optimizers | Generates improved coding sequences by integrating multiple design parameters, including codon context. | RiboDecode [28] (deep learning, context-aware), GeneOptimizer & ATGme [26] (strong multi-parameter performance). |

| tRNA-Supplemented E. coli Strains | Host strains that supply tRNAs for codons that are rare in E. coli, helping to prevent stalling and truncation. | Rosetta, BL21-CodonPlus strains. Essential for expressing genes with A/T-rich origins (e.g., Plasmodium) [34]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | Rapidly test the translation efficiency of optimized DNA templates without the complexity of live cells. | NEBExpress System [33]. Useful for screening multiple sequence variants and troubleshooting translation issues. |

| Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-seq) | An advanced NGS technique providing a genome-wide snapshot of ribosome positions, enabling empirical identification of stalling sites. | Not a reagent, but a service/specialized protocol. The gold standard for validating translation dynamics in vivo [32] [28]. |

Designing 'Typical Genes' to Resemble Host-Specific Expression Patterns

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core difference between a "typical gene" and a "codon-optimized" gene? The core difference lies in their design goals. Codon optimization primarily aims to maximize protein expression by using a host's most frequent codons, often focusing on a reference set of highly expressed genes. In contrast, designing a typical gene aims to replicate the nuanced codon usage patterns of a specific subset of the host's genes (e.g., lowly expressed genes, metabolic genes, or transmembrane protein genes). This approach seeks to integrate the gene more naturally into the host's existing regulatory networks, which can be crucial for avoiding cellular stress, achieving proper protein folding, or mimicking native expression levels for functional studies [37].

Q2: Why would I want to design a typical gene instead of just optimizing for high expression? There are several critical scenarios where designing a typical gene is advantageous:

- Expressing Toxic Proteins: For proteins that are toxic to the host cell (e.g., human α-synuclein), using a high-expression codon optimization can be detrimental. Designing a typical gene that resembles the codon usage of the host's lowly expressed genes can result in tolerable, functional expression levels [37].

- Metabolic Pathway Balancing: In heterologous pathways, maximizing the expression of every enzyme can lead to metabolic imbalances, resource competition, and accumulation of intermediate metabolites. Using typical genes helps fine-tune expression stoichiometry to achieve optimal flux [38].

- Physiological Relevance: When the goal is to study protein function in a model organism, mimicking the expression level and regulation of analogous native genes can provide more biologically relevant results.

Q3: What is "inverted codon usage" and when is it used? Inverted codon usage is a specific design strategy within the typical gene framework. It involves systematically reversing the codon usage bias observed in a reference set of genes (e.g., highly expressed ones) relative to the genome-wide average [37]. This technique is particularly useful for designing genes that need to be expressed at low levels, as it deliberately avoids the codons favored by the host's robust translational machinery.

Q4: My heterologous protein is being degraded. How can designing a typical gene help? While typical gene design focuses on transcriptional and translational regulation, its outcome can indirectly affect protein stability. By avoiding unnatural, high-speed translation that can lead to misfolding, a typical gene may promote correct protein folding, reducing its susceptibility to proteolysis by cellular quality control systems [6]. For a direct solution, also consider engineering the host strain, for example, by disrupting major extracellular protease genes (e.g., PepA in Aspergillus niger) [11].