Strategic Host Chassis Selection for Advanced Metabolic Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Next-Generation Platforms

Selecting an optimal microbial chassis is a critical, multi-faceted decision that determines the success of metabolic engineering projects aimed at biomanufacturing high-value therapeutics and chemicals.

Strategic Host Chassis Selection for Advanced Metabolic Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Next-Generation Platforms

Abstract

Selecting an optimal microbial chassis is a critical, multi-faceted decision that determines the success of metabolic engineering projects aimed at biomanufacturing high-value therapeutics and chemicals. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, synthesizing current knowledge from foundational principles to emerging trends. We explore the essential criteria for chassis evaluation, including genetic tractability, metabolic compatibility, and industrial robustness. The article further details advanced methodological tools like biosensors and genome-scale models, tackles common troubleshooting challenges, and offers a comparative analysis of both established and next-generation chassis platforms. This guide is designed to accelerate the Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle and inform strategic chassis selection for efficient, scalable bioproduction.

Defining the Ideal Chassis: Core Principles and Essential Criteria for Selection

In synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, a microbial chassis is defined as the physical, metabolic, and regulatory containment system that hosts engineered genetic circuits and devices [1]. This concept draws a clear distinction between the biological "hardware" (the chassis itself) and the "software" (the implanted genetic program) [1]. The selection of an optimal microbial chassis is a critical determinant of success, influencing the efficiency, yield, and stability of engineered biological systems [2] [1].

Historically, synthetic biology has been biased toward a narrow set of well-characterized model organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, due to their genetic tractability and the availability of robust engineering toolkits [2]. However, a paradigm shift is underway toward Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Synthetic Biology, which redefines the microbial host from a passive platform into an active, tunable design component [2]. This approach leverages microbial diversity to access a larger design space for applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics.

Core Selection Criteria for Microbial Chassis

Selecting an appropriate chassis requires a balanced consideration of intrinsic physiological properties, engineering feasibility, and application-specific demands. The table below summarizes the core criteria for chassis selection.

Table 1: Key Criteria for Selecting a Microbial Chassis

| Criterion | Description | Examples/Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tractability | Availability of tools for targeted genome manipulation. | CRISPR/Cas systems, replicative/suicide plasmids, characterized promoters [1] [3]. |

| Metabolic & Physiological Knowledge | Depth of understanding of physiology, metabolism, and regulation. | Availability of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics) [1] [3]. |

| Growth & Robustness | Fast growth on simple, cheap media; tolerance to process stresses. | High salinity (e.g., Halomonas bluephagenesis), thermotolerance, robust growth in bioreactors [2] [1]. |

| Native Functional Traits | Innate metabolic capabilities that align with the application. | Photosynthesis (cyanobacteria), C1 compound utilization (methylotrophs), high product yield (e.g., Zymomonas mobilis for ethanol) [2] [4]. |

| Resource Allocation & Burden | How cellular resources are allocated to host functions vs. engineered circuits. | Impacts circuit performance, predictability, and can cause growth defects [2]. |

| Regulatory & Safety Compliance | Suitability for industrial-scale and potentially open-environment applications. | Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status; non-pathogenicity [1]. |

A core principle in BHR synthetic biology is to treat the chassis as either a functional module or a tuning module [2]. As a functional module, the chassis's innate traits (e.g., photosynthesis, stress tolerance) are integrated directly into the design concept. As a tuning module, the host's unique cellular environment is used to adjust the performance specifications of a genetic circuit, such as its responsiveness, sensitivity, and output strength [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Prominent Microbial Chassis

The field utilizes a spectrum of chassis, from traditional workhorses to emerging non-model organisms with specialized capabilities. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of several key microbial chassis.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Selected Microbial Chassis and Their Engineering Outcomes

| Chassis Organism | Key Native characteristic | Target Product(s) | Reported Experimental Yield / Titer | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Rapid growth, extensive genetic toolset | Diverse biochemicals, proteins | N/A (Model organism) | General metabolic engineering, proof-of-concept [2] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Solvent tolerance, metabolic versatility | Engineered for C1 assimilation | N/A (Platform development) | Bioremediation, bioproduction from non-sugar feedstocks [1] [4] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Organic acid secretion, food-grade status | Amino acids, organic acids | N/A (Established industrial host) | Industrial bioproduction [1] [4] |

| Zymomonas mobilis | High sugar uptake, high ethanol yield & tolerance | D-lactate, 2,3-butanediol, ethylene | D-lactate: >140 g/L from glucose; >104 g/L from corncob residue (Yield >0.97 g/g) [3] | Lignocellulosic biorefinery [3] |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis | High salinity tolerance, reduced sterility needs | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | N/A (Platform development) | Large-scale production under open, non-sterile conditions [2] [1] |

| Clostridium spp. (Engineered) | Solventogenic metabolism | Butanol | 3-fold yield increase reported in engineered strains [5] | Advanced biofuel production [5] |

| S. cerevisiae (Engineered) | Eukaryotic expression system, ethanol producer | Ethanol (from xylose) | ~85% conversion of xylose to ethanol [5] | Lignocellulosic biofuel production [5] |

Experimental Workflow for Chassis Development and Engineering

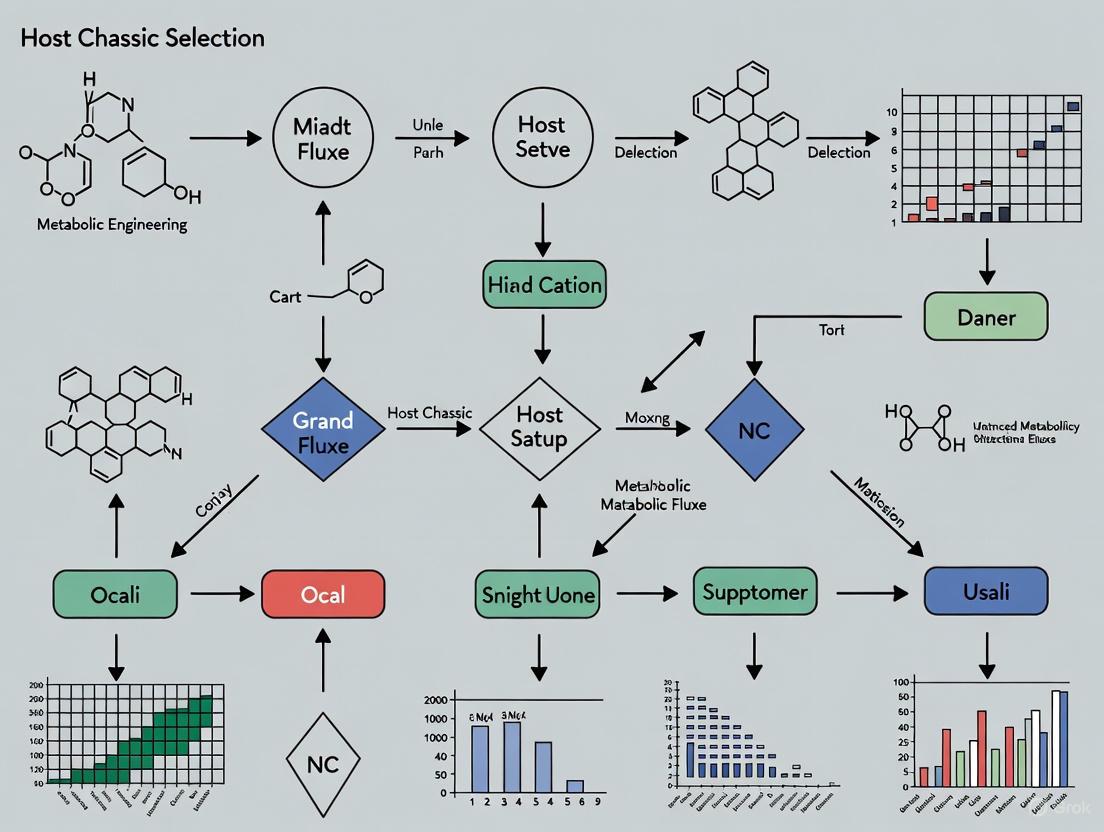

Engineering a non-model microorganism into a reliable chassis requires a systematic, multi-stage workflow. The following diagram and protocol outline this process.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Developing a Non-Model Chassis

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

Genome Sequencing and Curation

- Objective: Obtain a complete and accurately annotated genome sequence.

- Methodology: Utilize next-generation sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina) often combined with long-read technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) for a high-quality draft or complete genome. Functional annotation is performed using databases like KEGG, UniProt, and COG to identify metabolic pathways and potential pathogenic factors [1].

Genetic Toolbox Development

- Objective: Establish methods for introducing and manipulating DNA.

- Methodology:

- Transformation: Optimize protocols for chemical or electroporation-based DNA uptake.

- Vector Design: Construct shuttle vectors with origins of replication functional in the new host and E. coli, along with selectable markers.

- Genome Editing: Implement CRISPR-Cas systems (e.g., Cas9, Cas12a) or other nucleases for targeted gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and repression. For polyploid organisms like Zymomonas mobilis, efficient editing may rely on endogenous repair pathways like microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) [3].

Systems Biology Analysis and Metabolic Modeling

- Objective: Understand and model the host's metabolic network.

- Methodology:

- Omics Data Collection: Conduct transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics under relevant growth conditions.

- (^{13})C-Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA): Quantitatively determine intracellular metabolic reaction rates [3].

- Genome-Scale Model (GEM) Construction: Build a stoichiometric model of metabolism. This can be enhanced into an Enzyme-Constrained Model (ecModel) by integrating enzyme kinetic data (kcat values), which improves prediction accuracy by accounting for proteome limitations [3]. Tools like ECMpy and AutoPACMEN can be used for this purpose.

Pathway Design and In Silico Validation

- Objective: Design and simulate the performance of heterologous pathways.

- Methodology: Use the refined GEM (e.g., eciZM547 for Z. mobilis) [3] to perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). This predicts theoretical maximum yields, identifies potential metabolic bottlenecks, and checks for cofactor balance before embarking on costly laboratory experiments.

Strain Construction and Laboratory Validation

- Objective: Build and test the engineered strain.

- Methodology: Use the genetic tools from Step 2 to implement the design from Step 4. This involves chromosomal integration or plasmid-based expression of pathway genes. Performance is validated in lab-scale bioreactors, measuring titer, yield, productivity, and growth rates.

Scale-Up and Sustainability Assessment

- Objective: Evaluate industrial potential and environmental impact.

- Methodology:

- Scale-Up: Transition fermentation to pilot and eventually industrial-scale bioreactors, optimizing parameters like oxygen transfer, pH, and feed strategy.

- Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA): Model the production costs to assess economic viability [4] [3].

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Quantify the environmental footprint (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions) of the entire production process [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, tools, and materials essential for chassis engineering experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chassis Engineering

| Item Name / Category | Function / Description | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas System | Enables precise genome editing (knock-out, knock-in, repression). | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12a; requires a Cas nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [5] [3]. |

| Modular Vector Systems | Replicative plasmids for gene expression; suicide plasmids for chromosomal integration. | Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA); broad-host-range plasmids with modular origins of replication [2]. |

| Characterized Biological Parts | Standardized DNA sequences to control gene expression predictably. | Promoters (constitutive and inducible), Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS), terminators [1] [3]. |

| Enzyme Kinetics Database | Provides kcat values for constraining metabolic models and predicting flux limitations. | AutoPACMEN, DLkcat; used to build enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) [3]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | In silico model of metabolism for simulating and predicting strain behavior. | iZM547 for Zymomonas mobilis; E. coli's iJO1366. Improved predictions when enzyme-constrained (ecGEM) [3]. |

| C1 Assimilation Pathway Kit | Synthetic gene modules for enabling growth on one-carbon substrates. | Modules for the Reductive Glycine Pathway (rGlyP), Ribulose Monophosphate (RuMP) cycle [4]. |

Advanced Concepts and Overcoming the "Chassis Effect"

A significant challenge in BHR synthetic biology is the "chassis effect"—where identical genetic constructs perform differently across various host organisms due to host-construct interactions [2]. These interactions arise from:

- Resource Competition: Competition for finite cellular resources like RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and precursor metabolites [2].

- Metabolic Burden: Expression of heterologous genes diverts energy and resources from growth, triggering global physiological changes [2].

- Regulatory Crosstalk: Differences in transcription factor specificity, abundance, or sigma factor interactions can alter device behavior [2].

Case Study: EngineeringZymomonas mobilisas a Biorefinery Chassis

Zymomonas mobilis naturally directs most of its carbon flux through its dominant ethanol production pathway. Directly engineering it for other products often results in low yields due to this innate metabolic dominance. A novel strategy termed Dominant-Metabolism Compromised Intermediate-Chassis (DMCI) was developed to overcome this [3].

The strategy involves first weakening the dominant native pathway by introducing a competing, low-toxicity pathway that creates cofactor imbalance, forcing the chassis to adapt and rewire its metabolism. Subsequently, this adapted "intermediate chassis" is more amenable to engineering for high-yield production of the target biochemical, such as D-lactate [3]. The metabolic logic of this strategy is shown below.

Diagram Title: DMCI Strategy to Bypass Dominant Metabolism

The field of microbial chassis engineering is rapidly evolving from reliance on a few model organisms toward a BHR paradigm that strategically selects or engineers hosts based on application-specific criteria. The integration of advanced genomics, systems biology, and synthetic biology tools is enabling the systematic domestication of non-model microbes with unique, advantageous phenotypes.

Future development will be driven by several key trends: the use of AI and machine learning to accelerate enzyme and pathway discovery [5], the refinement of ecModels for more predictive design [3], and the early application of TEA and LCA to guide sustainable process development [4] [3]. Furthermore, the exploration of novel, polytrophic chassis for the utilization of next-generation feedstocks like C1 compounds (e.g., methanol, CO2) will be crucial for establishing a circular bioeconomy [4]. As these tools and concepts mature, the rational selection and engineering of microbial chassis will continue to be the foundational engine of innovation in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

In the field of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, a biological chassis serves as the foundational cellular platform—the physical, metabolic, and regulatory containment for installing and operating genetic circuits and biosynthetic pathways [1]. The selection and optimization of this host organism is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of success across biomanufacturing, therapeutic development, and fundamental research. Historically, metabolic engineering has focused predominantly on a narrow set of model organisms, but emerging research demonstrates that host selection represents a crucial design parameter that profoundly influences the behavior of engineered genetic systems through resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [2].

This technical guide establishes a structured framework for chassis selection based on six essential pillars, providing researchers with methodologies to systematically evaluate and engineer microbial hosts. By treating the chassis not as a passive vessel but as an integral tunable component, scientists can unlock greater predictability, stability, and functionality in their engineered biological systems [2]. The principles outlined herein support the broader thesis that strategic chassis development expands the design space for biotechnology applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics.

The Conceptual Framework: Beyond Passive Vessels to Tunable Biological Modules

The paradigm of chassis selection has evolved significantly from the early days of metabolic engineering. Where host organisms were once viewed primarily as passive providers of cellular machinery, they are now recognized as active participants in determining system performance [2]. This conceptual shift acknowledges that the same genetic construct can exhibit dramatically different behaviors depending on the host context—a phenomenon known as the "chassis effect" [2]. This effect manifests through multiple mechanisms including resource competition for ribosomes and RNA polymerase, metabolic burden, promoter–sigma factor interactions, and host-specific regulatory crosstalk [2].

Contemporary biodesign recognizes two complementary roles for chassis: as functional modules whose innate biological traits are integrated into the design concept, and as tuning modules that adjust the performance specifications of genetic circuits [2]. For example, the native photosynthetic capabilities of cyanobacteria can be rewired for biosynthetic production from CO₂, while the natural stress tolerance of extremophiles makes them ideal chassis for processes requiring robust performance in harsh environments [2]. This dual perspective enables synthetic biologists to leverage the vast diversity of microbial physiology rather than attempting to engineer all desired traits into a limited set of model organisms.

The Six Pillars: Comprehensive Evaluation Criteria

Pillar 1: Genetic Tractability

Genetic tractability encompasses the ease and precision with which a host organism can be genetically modified, representing the foundational enabler for metabolic engineering. This pillar includes the availability of efficient DNA delivery methods, genome editing tools, and well-characterized regulatory parts for controlling gene expression.

Table: Essential Genetic Toolkits for Bacterial Chassis Development

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Host Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12, Red recombinase, I-SceI meganuclease | Targeted gene knock-in/knock-out, point mutations | Broad (CRISPR) to specific (Red recombinase for E. coli) |

| Vector Systems | SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture), p15A-based shuttle vectors | Modular genetic constructs with standardized parts | Broad-host-range specific |

| DNA Delivery Methods | Electroporation, conjugation, transduction | Introduction of foreign DNA into host | Method-dependent |

| Regulatory Parts | Native inducible promoters, synthetic RBS libraries | Fine-tuned control of gene expression | Often host-specific |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Genetic Tractability

- Transformation Efficiency Quantification: Prepare electrocompetent cells and transform with a standardized plasmid (e.g., pUC19). Calculate transformation efficiency as CFU/μg DNA.

- Gene Editing Success Rate Assessment: Introduce a CRISPR-Cas9 system targeting a non-essential gene with a silent mutation. Sequence 20+ colonies to determine editing efficiency.

- Tool Compatibility Testing: Assess functionality of broad-host-range tools (e.g., SEVA vectors) through antibiotic resistance markers and fluorescence reporters.

- Parts Characterization: Measure expression strength and leakage of promoter libraries using transcriptional reporters (e.g., GFP).

Pillar 2: Growth and Physiological Properties

Optimal chassis candidates must demonstrate robust growth characteristics under both laboratory and industrial conditions. Key metrics include specific growth rate, biomass yield, nutritional requirements, and resilience to process-induced stresses. Industrial bioprocesses demand organisms with simple nutritional requirements that can utilize low-cost feedstocks while achieving high cell densities [1].

Industrial Streptomyces chassis development exemplifies this principle. When comparing potential hosts for Type II polyketide production, Streptomyces aureofaciens J1-022 was selected over S. rimosus based on superior physiological properties including shorter fermentation cycles (approximately half the time), better colony morphology for reliable genetic manipulation, and higher transformation efficiency [6]. These characteristics directly impact research and development timelines and manufacturing economics.

Table: Growth Characteristics of Model Chassis Organisms

| Organism | Doubling Time (hours) | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Maximum Biomass (gDCW/L) | Common Feedstocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 0.3-1.0 | 37 | 10-100 | Glucose, glycerol, lactose |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0.5-1.5 | 37 | 5-50 | Glucose, sucrose, starch |

| Streptomyces aureofaciens | 2-4 | 28-30 | 10-40 | Glucose, soybean meal |

| Pseudomonas putida | 1-2 | 30 | 5-80 | Glucose, glycerol, organic acids |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | 1-2 | 30 | 10-100 | Glucose, sucrose, acetate |

Pillar 3: Metabolic Capabilities

The native metabolic network of a chassis determines its potential for engineering novel biosynthetic pathways. Key considerations include precursor metabolite availability, cofactor balance, energy metabolism, and the presence of competing or orthogonal pathways. Metabolic versatility enables efficient utilization of diverse feedstocks, including non-traditional carbon sources like C1 compounds (methanol, formate, CO₂) [4].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolic Flux Analysis

- Isotope Labeling: Grow cells on ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-¹³C]glucose) to isotopic steady state.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Quantify ¹³C enrichment in intracellular metabolites via GC-MS or LC-MS.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational modeling (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis, ¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis) to determine intracellular reaction rates.

- Pathway Efficiency Assessment: Compare theoretical and experimental yields of target metabolites to identify flux bottlenecks.

Advanced chassis engineering often employs genome streamlining to reduce metabolic complexity and redirect resources toward product formation. For Streptomyces hosts, this involves identifying and deleting non-essential secondary metabolite clusters to minimize precursor competition and create a "clean background" for heterologous pathway expression [6]. The resulting chassis demonstrates enhanced metabolic efficiency without compromising viability or biosynthetic capability.

Pillar 4: Safety and Biocontainment

Biological safety is paramount when engineering organisms for industrial or environmental applications. This encompasses both innate properties (non-pathogenicity, lack of toxin production) and engineered safeguards (auxotrophies, kill switches) to prevent unintended proliferation. For industrial biotechnology, Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status facilitates regulatory approval and public acceptance [1].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing Biosafety

- Pathogenicity Factor Screening: In silico analysis of genome sequences for known virulence factors and toxin genes.

- Antibiotic Resistance Profiling: Determine intrinsic resistance patterns and screen for acquired resistance genes.

- Environmental Survival Assessment: Measure viability under non-permissive conditions (e.g., nutrient limitation, temperature extremes).

- Containment System Validation: Test engineered auxotrophies or inducible kill switches under simulated escape scenarios.

Pillar 5: Robustness and Stress Tolerance

Industrial bioprocesses expose microorganisms to numerous stresses—substrate and product inhibition, osmotic pressure, shear forces, and oxidative damage. A superior chassis possesses inherent robustness or can be engineered for improved tolerance. Systems biology approaches enable identification of stress response mechanisms that can be enhanced through metabolic engineering [1].

Table: Stress Tolerance Mechanisms in Bacterial Chassis

| Stress Type | Cellular Impact | Native Tolerance Mechanisms | Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Inhibition | Membrane disruption, protein denaturation | Efflux pumps, membrane modification | Heterologous transporter expression, membrane engineering |

| Osmotic Pressure | Water efflux, growth inhibition | Compatible solute synthesis | Enhanced osmolyte production pathways |

| Thermal Stress | Protein misfolding, membrane fluidity | Heat shock proteins, chaperones | Regulatory circuit engineering for stress response |

| Oxidative Stress | Macromolecule damage | Antioxidant systems, DNA repair | Overexpression of catalase, superoxide dismutase |

Pillar 6: Secretion and Export Capabilities

Efficient product secretion simplifies downstream processing, reduces product inhibition, and enables continuous bioprocessing. Native secretion systems vary significantly across microbial hosts, with some exhibiting exceptional capacity for protein export or metabolite efflux. For non-secreted products, chassis engineering can introduce or enhance export machinery [1].

Experimental Protocol: Secretion Efficiency Evaluation

- Extracellular Product Quantification: Separate cells from culture broth via centrifugation, then measure product concentration in supernatant.

- Cell Integrity Assessment: Monitor intracellular enzyme release to distinguish true secretion from cell lysis.

- Transporters Identification: Use genome mining to identify putative efflux systems and secretion machinery.

- Secretion Engineering: Heterologously express transporters from native producers (e.g., Bacillus subtilis protein secretion systems).

Integrated Workflow for Chassis Evaluation and Engineering

A systematic approach to chassis development incorporates all six pillars through iterative design-build-test-learn cycles. The workflow begins with multi-parameter assessment of candidate hosts, proceeds to targeted engineering, and culminates in performance validation under industrially relevant conditions.

Case Study: Streptomyces Chassis for Polyketide Production

The development of Streptomyces aureofaciens Chassis2.0 exemplifies the practical application of the six pillars framework [6]. This specialized chassis was created specifically for efficient production of diverse Type II polyketides (T2PKs), compounds with important pharmacological activities.

Genetic tractability was established through implementation of ExoCET technology for direct cloning of large biosynthetic gene clusters and CRISPR-based genome editing [6]. Growth properties were optimized by selecting a host with rapid growth cycle and robust colony morphology. Metabolic capabilities were enhanced through in-frame deletion of two endogenous T2PKs gene clusters (ctc and aureol) to eliminate precursor competition, creating a "pigmented-faded" host [6].

The resulting Chassis2.0 demonstrated remarkable performance improvements:

- Oxytetracycline production increased by 370% compared to commercial production strains

- Efficient synthesis of tri-ring type T2PKs (actinorhodin and flavokermesic acid)

- Direct activation of an unidentified pentangular T2PKs biosynthetic gene cluster, leading to discovery of novel compound TLN-1 [6]

This case study demonstrates how strategic chassis engineering enables both overproduction of known compounds and discovery of novel natural products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Chassis Development and Evaluation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning Systems | SEVA vectors, p15A-based shuttle vectors, BAC vectors | Heterologous expression, pathway engineering | Host range, copy number, modularity |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9/Cas12 systems, I-SceI meganuclease, Red recombinase | Targeted genetic modifications | Efficiency, off-target effects, host compatibility |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, auxotrophic markers | Strain selection and maintenance | Compatibility with industrial applications |

| Reporter Systems | GFP, RFP, lux operon | Promoter characterization, flux measurements | Quantification sensitivity, stability |

| Analytical Standards | ¹³C-labeled metabolites, authentic product standards | Metabolic flux analysis, product quantification | Isotopic purity, chemical stability |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The field of chassis development is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Broad-host-range synthetic biology is redefining the role of microbial hosts by moving beyond traditional model organisms to leverage the vast diversity of microbial physiology [2]. Automation and machine learning are accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle, enabling high-throughput evaluation of chassis properties and engineering strategies.

The integration of techno-economic analysis and life cycle assessment at early stages of chassis development ensures that biological optimization aligns with economic viability and sustainability goals [4]. For C1-based biomanufacturing, this means selecting chassis and pathways that maximize carbon efficiency while minimizing energy inputs and environmental impacts [4].

The concept of specialized chassis is gaining traction, with hosts being engineered for specific applications rather than general-purpose use. Examples include Streptomyces strains optimized for polyketide production [6] and non-model organisms engineered for C1 compound utilization [4]. This specialization enables researchers to "match the chassis to the challenge" rather than relying on one-size-fits-all solutions.

As synthetic biology continues to mature, the systematic application of the six pillars framework will support development of next-generation chassis with enhanced capabilities for sustainable biomanufacturing, therapeutic production, and environmental applications.

The selection of a microbial host chassis is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering and industrial biotechnology, directly impacting the success and efficiency of bioproduction. Among the plethora of available organisms, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have emerged as the most established and widely adopted chassis due to their well-characterized genetics, extensive toolkits, and proven industrial track records. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these three cornerstone chassis, framing their unique attributes and recent advancements within the critical context of host selection criteria for research and development. For scientists and drug development professionals, understanding the evolving capabilities of these workhorses—from E. coli's new role in C1 fermentation to B. subtilis's enhanced protein secretion and S. cerevisiae's exploitation of natural diversity—is essential for strategic experimental design and platform development.

Core Characteristics and Industrial Applications

Escherichia coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, remains the preeminent prokaryotic chassis for metabolic engineering. Its rapid growth, high-density cultivation feasibility, and unparalleled genetic tractability have solidified its position. Recent innovations have dramatically expanded its substrate range, notably with the creation of synthetic methylotrophic strains capable of growth on methanol, a renewable one-carbon feedstock [7]. This advancement positions E. coli for carbon-negative bioproduction from greenhouse gas-derived substrates.

Bacillus subtilis, a Gram-positive bacterium, is a premier host for protein secretion. Its naturally high secretion capacity, GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status, and well-developed fermentation technologies make it an ideal chassis for industrial enzyme production [8] [9]. The absence of an outer membrane simplifies the secretion process for recombinant proteins, and recent progress in systems metabolic engineering has further enhanced its capabilities [8].

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a eukaryotic yeast, offers the distinct advantage of performing complex eukaryotic post-translational modifications. This makes it a preferred chassis for producing complex eukaryotic proteins, including human biopharmaceuticals. It has a proven track record in the commercial production of therapeutics like insulin, growth hormones, and vaccines for hepatitis B and HPV [10]. Its robustness and cost-effective culturing are significant benefits for industrial-scale operations.

Quantitative Chassis Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of the three chassis to facilitate direct comparison for research and development planning.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Established Microbial Chassis

| Feature | Escherichia coli | Bacillus subtilis | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism Type | Gram-negative Bacterium | Gram-positive Bacterium | Eukaryotic Yeast |

| Doubling Time | ~4.3 h (on methanol) [7] | Varies by strain/conditions | Varies by strain/conditions |

| Recombinant Protein Yield | High intracellular, challenging secretion | High extracellular secretion | Capable of secreting large, modified proteins [10] |

| Key Engineering Tool | CRISPR, Continuous Evolution | CRISPR Toolkits, Promoter Engineering [11] | High-throughput Screening, Pan-genome Mining [10] |

| Post-Translational Modification | Limited (prokaryotic) | Limited (prokaryotic) | Advanced (eukaryotic; e.g., glycosylation) |

| Exemplar Bioproduct | Itaconic acid (1 g/L from methanol) [7] | Amylase (High extracellular activity) [9] | Fungal Laccases [10] |

| Primary Industrial Application | Biochemicals, Biopharmaceuticals | Industrial Enzymes | Biopharmaceuticals, Biofuels |

Detailed Chassis Analysis

Escherichia coli: The Versatile Metabolic Engineer

Recent Advancements in Methylotrophy: A landmark achievement in metabolic engineering is the development of a synthetic methylotrophic E. coli strain. This chassis was engineered with the ribulose monophosphate (RuMP) cycle for methanol assimilation. Through extensive laboratory evolution spanning over 1,200 generations, researchers isolated a strain (MEcoliref2) capable of growth on methanol with a doubling time of 4.3 hours, a performance comparable to natural methylotrophs [7]. This strain serves as a platform for bioproduction from methanol, with demonstrated synthesis of lactic acid, polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), itaconic acid, and p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) from key metabolic nodes [7].

Key Genetic Adaptations: Genomic analysis of the evolved methylotrophic strains revealed convergent evolution in several critical metabolic units. Key mutations included:

- Methanol Dehydrogenase (Mdh): Amino acid substitutions (e.g., F279I) that lower the enzyme's KM for methanol from 164 mM to 112 mM, enhancing activity at lower methanol concentrations [7].

- hps-phi Operon Promoter: Mutations fine-tuning the expression of 3-hexulose-6-phosphate synthase and 6-phospho-3-hexuloisomerase, crucial for efficient formaldehyde assimilation [7].

- 6-Phosphogluconate Dehydrogenase (gnd): Mutations in this dissimilatory RuMP cycle enzyme, likely impacting NADPH regeneration and formaldehyde detoxification fluxes [7].

The diagram below illustrates the engineered methanol utilization pathway in E. coli.

Bacillus subtilis: The Protein Secretion Specialist

Engineering an Autoinducible Expression System: A significant bottleneck in using exogenous quorum sensing (QS) systems in B. subtilis has been their low autoinducible expression. A recent study addressed this by systematically engineering the LuxI/R-type QS device from Vibrio fischeri [9]. The system was decomposed into a sensing module (containing luxI and luxR) and a response module (containing the gene of interest under a QS-responsive promoter). Researchers enhanced autoinducible expression by engineering both modules:

- Sensing Module Promoter (SPluxI): The core (-10 and -35) and critical (UP and spacer) regions were optimized to increase the baseline expression of the AHL synthase (LuxI) and receptor (LuxR) [9].

- Response Module Promoter (RPluxIR6): The core region and the copy number of the lux box (the binding site for the LuxR-AHL complex) were engineered to strengthen the response to AHL signaling [9]. The optimized construct (Sc-R2) achieved a 2.7-fold and 3.1-fold increase in extracellular amylase activity compared to the constitutive Pveg promoter in shake flask and 3-L fermenter fermentations, respectively [9].

Advanced Genome Engineering with CRISPR: The development of CRISPR-based genetic toolkits has revolutionized genome editing and regulation in B. subtilis. These tools have moved beyond simple gene knockouts to include:

- Transcriptional Regulation: Using nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressors or activators for fine-tuning gene expression [11].

- Base Editing: Employing Cas9 nickase fused to deaminase enzymes for precise point mutations without requiring double-strand breaks or donor templates [11].

- Multiplexed Editing: Enabling simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci, which is crucial for complex metabolic engineering [11]. These advancements have accelerated the engineering of B. subtilis for the production of biochemicals and proteins, narrowing the gap with traditional industrial chassis like E. coli [11].

Table 2: Key Reagents for B. subtilis Autoinducible System Development

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| LuxI/R Device | Core QS system from V. fischeri; comprises AHL synthase (LuxI) and receptor protein (LuxR). Bioorthogonal to native B. subtilis systems [9]. |

| Acylhomoserine Lactone (AHL) | Autoinducer molecule; diffuses freely and, at high concentration, activates LuxR to initiate expression of the gene of interest [9]. |

| Engineered Promoters (SPluxI, RPluxIR6) | Genetically modified promoter sequences in sensing and response modules to enhance system performance and reduce expression leakage [9]. |

| Reporter Proteins (Amylase, Levansucrase) | Enzymes used to quantitatively measure the performance and generalizability of the expression system via extracellular activity assays [9]. |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae: The Eukaryotic Production Platform

Leveraging Natural Diversity for Enhanced Production: Recombinant protein yields in S. cerevisiae can be limited by cellular bottlenecks. To identify novel engineering targets, a high-throughput screen of approximately 1,000 diverse S. cerevisiae isolates (including wild, industrial, and laboratory strains) was conducted to find strains with a naturally high capacity for producing fungal laccases [10]. The screen identified 20 strains with significantly improved laccase production compared to the common laboratory strain BY4741. Intriguingly, most high-producing strains showed lower recombinant mRNA levels, indicating that post-transcriptional and post-translational processes are key drivers of the improved phenotype [10].

Proteomic and Genomic Characterization: Analysis of the high-producing strains revealed several potential pathways for engineering:

- Carbohydrate Catabolism: Changes in genes/proteins involved in sugar metabolism may redirect metabolic flux and energy towards recombinant protein production [10].

- Thiamine Biosynthesis: Alterations in this vitamin's biosynthesis could influence cofactor availability for various enzymes, indirectly aiding production [10].

- Vacuolar Degradation: Modifications in vacuolar function may reduce the degradation of the recombinant protein [10].

- Transmembrane Transport: Changes in transport systems could improve secretion efficiency [10]. Guided by this analysis, targeted gene deletions confirmed new engineering targets. Deleting the hexose transporter HXT11 and the ER-to-Golgi transport genes PRM8/9 in the lab strain S288c significantly improved laccase production [10]. The workflow for this systems-level approach is depicted below.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of S. cerevisiae for Protein Production

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to identify yeast strains with superior recombinant laccase production [10].

1. Strain Library and Plasmid Preparation:

- Strains: Utilize a diverse library of S. cerevisiae strains (e.g., wild, industrial, laboratory isolates). Ensure the collection is sequence-verified.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the gene of interest (e.g., ttLCC1 laccase) into a CEN/ARS plasmid with a dominant selectable marker (e.g., kanMX6 for G418 resistance) under the control of a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., GPD1).

2. Transformation and Arraying:

- Transform the expression plasmid into the entire strain library using a high-efficiency transformation method.

- Array successful transformants into 96-deep-well plates, maintaining a single replicate of each strain per plate. Include a control strain (e.g., BY4741) in multiple positions on each plate as an internal reference.

3. Cultivation and Assay:

- Inoculate cultures in the deep-well plates using a liquid handling robot and grow for a defined period (e.g., 96 hours) at 30°C with shaking.

- Centrifuge the plates to pellet cells. Carefully transfer the clarified supernatant to a new assay plate.

- Activity Assay: Mix the supernatant with an appropriate substrate (e.g., ABTS for laccase). Measure the reaction product spectrophotometrically (e.g., absorbance at 420 nm for ABTS oxidation).

4. Data Analysis and Hit Confirmation:

- Normalize the activity data from all strains against the internal plate controls.

- Set a hit threshold (e.g., activity > 3 median absolute deviations above the median).

- Re-transform the hit strains to confirm the phenotype, this time cultivating multiple biological replicates for robust statistical analysis.

Protocol: Fermentation of Engineered B. subtilis in a 3-L Bioreactor

This protocol outlines the process for evaluating an autoinducible expression system in B. subtilis at a bioreactor scale [9].

1. Seed Culture Preparation:

- Inoculate a single colony of the engineered B. subtilis strain (e.g., WB600 harboring the Sc-R2 construct) into a test tube containing 5 mL of LB medium.

- Incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm.

- Sub-culture the primary seed into a larger volume (e.g., 60 mL of 2xYT medium) and incubate at 37°C for approximately 12 hours to obtain a secondary seed culture.

2. Bioreactor Setup and Inoculation:

- Use a 3-L fermenter with an initial working volume of 1.2 L of basic production medium (e.g., containing molasses, soybean peptone, yeast extract, salts, and trace elements).

- Inoculate the sterilized and tempered bioreactor with the secondary seed culture at 5% (v/v) inoculation ratio.

3. Fermentation Process Control:

- Maintain the fermentation temperature at 30°C.

- Control pH within a defined range (e.g., 6.5-7.5) by the automated addition of NH₄OH and HCl.

- Maintain dissolved oxygen (DO) at approximately 30% saturation by automatically adjusting the stirrer speed and air flow rate.

- Initiate a feeding strategy once the initial carbon source is depleted, using a feed medium with concentrated nutrients.

4. Analytical Monitoring:

- Periodically sample the broth.

- Biomass: Measure optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀).

- Product Titer: For enzyme production, assay extracellular activity (e.g., amylase activity via starch hydrolysis).

- Substrate/Metabolites: Analyze concentrations of key carbon and nitrogen sources using HPLC or other suitable methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below consolidates key reagents and tools utilized in the advanced engineering strategies discussed for these chassis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chassis Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Chassis | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Toolkit | B. subtilis [11], E. coli | Enables efficient, programmable genome editing, transcriptional regulation, and base editing. |

| Ribulose Monophosphate (RuMP) Cycle Genes | E. coli [7] | Allows engineering of synthetic methylotrophy for growth on methanol. |

| LuxI/R Quorum Sensing Device | B. subtilis [9] | Provides a bioorthogonal, autoinducible system for dynamic gene expression without external inducers. |

| Dominant Selectable Markers (e.g., kanMX6) | S. cerevisiae [10] | Allows for plasmid selection in non-auxotrophic, wild, and industrial strains. |

| Reporter Genes (β-galactosidase, sfGFP, Laccase) | All | Facilitates rapid, quantitative screening of promoter strength, secretion efficiency, and system optimization. |

| CEN/ARS Plasmids | S. cerevisiae [10] | Low-copy number plasmids for stable gene expression with reduced metabolic burden. |

E. coli, B. subtilis, and S. cerevisiae continue to be pillars of metabolic engineering, each offering a unique combination of characteristics that can be meticulously matched to project goals. The selection criteria extend beyond traditional metrics to include newer capabilities such as the utilization of alternative feedstocks, the sophistication of autoinduction systems, and the potential unlocked by natural diversity. The ongoing refinement of genetic toolkits, particularly CRISPR-based systems, ensures that these established chassis remain at the forefront of biotechnological innovation. For researchers, the strategic selection and engineering of these hosts, informed by the latest advancements in systems and synthetic biology, are paramount to developing efficient and economically viable bioprocesses for the production of therapeutics, enzymes, and renewable chemicals.

The selection of a microbial chassis is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering, directly influencing the economic viability and scalability of bioprocesses. While traditional workhorses like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have dominated the field, their limitations in specific applications have accelerated the exploration of non-model organisms with specialized, advantageous phenotypes. The emergence of next-generation industrial biotechnology (NGIB) leverages robust microbes that can drastically reduce production costs by enabling open, non-sterile fermentation processes [12] [13]. This in-depth technical guide evaluates three promising emerging chassis—Vibrio natriegens, Halomonas spp., and Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)—within the critical context of host chassis selection criteria. We detail their unique physiological traits, the development of synthetic biology toolkits, metabolic engineering case studies, and provide a structured framework for selecting the optimal chassis for specific research and industrial applications.

Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics

The comparative advantage of each chassis stems from its innate physiological and metabolic characteristics, which should be aligned with the target product and production process.

Table 1: Comparative Physiological Traits of Emerging Chassis

| Feature | Vibrio natriegens | Halomonas spp. | Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Growth Rate | 4.24–4.42 h⁻¹ (doubling time: ~10 min) in rich medium [14] | Varies by species; moderate growth rate | Moderate growth rate; dependent on species and conditions |

| Growth Rate (Minimal Medium) | 1.48–1.70 h⁻¹ on glucose [14] [15] | Varies by species | Varies by species and sugar source |

| Salt Requirement | Requires Na⁺ (marine bacterium) [14] | Extreme halophile (3-30% NaCl w/v) [12] | Non-halophilic |

| Oxygen Requirement | Facultatively anaerobic [14] | Aerobic [12] | Mostly anaerobic; aero-tolerant [16] |

| Primary Metabolism | Glycolysis (EMP), PPP, Entner-Doudoroff [14] | Standard aerobic respiration [12] | Homo- or heterofermentative [16] [17] |

| Key Native Products | Acetate, succinate, lactate (anaerobic) [14] | PHB, ectoine, hydroxyectoine [12] | Lactic acid, diacetyl, acetoin [16] |

| Primary Industrial Application | Platform for small molecules, proteins [14] [15] | NGIB: non-sterile production of bioplastics and chemicals [12] [13] | Food fermentations, bioplastics (PLA) precursors, probiotics [16] [17] |

| Major Cost-Reduction Feature | Ultra-high substrate uptake rate & productivity [18] | Contamination-resistant growth enabling low-cost reactors [12] [13] | Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS) status; simple nutritional needs [17] |

Genetic Toolbox and Engineering Methods

The feasibility of a chassis is contingent on the availability of efficient genetic tools. Significant progress has been made in developing toolkits for these non-model organisms.

Vibrio natriegens

V. natriegens benefits from its rapid growth, which accelerates the design-build-test-learn cycle. A suite of genetic tools has been developed, including:

- Cloning Vectors: Broad-host-range plasmids (e.g., SEVA system) and IPTG-inducible systems like Ptac [15].

- Genome Editing: CRISPR-Cas9 systems have been implemented for efficient gene knockouts and integrations [18]. A prophage-free strain (PYR02) was created to improve genetic stability and cell robustness during fermentation [18].

- Regulatory Parts: A library of constitutive promoters of varying strengths and RBS elements for fine-tuning gene expression is available [18]. This allows for precise metabolic engineering, such as the down-regulation of the aceE gene to modulate pyruvate dehydrogenase activity [18].

Halomonas spp.

The genetic system for Halomonas, particularly H. bluephagenesis, is advanced, supporting its status as a premier NGIB chassis.

- Cloning Vectors: Stable plasmid systems that leverage the host's halophily for selection and maintenance [12] [13].

- Genome Editing: Conjugation-based gene transfer and CRISPR-Cas systems enable chromosomal integration and gene knockout [12] [13].

- Pathway Engineering: Tools have been used to engineer complex pathways, such as the nine-gene module for the production of C5 chemicals from L-lysine in H. bluephagenesis [13].

Lactic Acid Bacteria

LAB are genetically diverse, but Lactococcus lactis serves as a model with a well-developed toolkit.

- Expression Systems: The Nisin-Inducible Controlled Expression (NICE) system allows for tightly regulated, high-level gene expression [16].

- Metabolic Engineering Strategies: Common approaches include deleting genes for competing pathways (e.g., ldh for lactate dehydrogenase) and overexpressing key enzymes like phosphofructokinase (PFK) to increase glycolytic flux [16].

- Surface Display: Systems for anchoring heterologous proteins on the cell surface are well-established, facilitating vaccine and biocatalyst development [19].

Metabolic Engineering Case Studies & Protocols

Case Study 1: High-Rate Pyruvate Production inVibrio natriegens

Pyruvate is a key metabolic hub, and the high substrate uptake rate of V. natriegens makes it an ideal candidate for achieving high volumetric productivities [18].

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Stabilization: Delete the two inducible prophage gene clusters (VPN1 and VPN2) from the wild-type V. natriegens to generate a robust base strain (e.g., PYR02) [18].

- Block Byproduct Formation: Knock out genes encoding enzymes for major byproducts:

- pflB (pyruvate formate-lyase) to eliminate formate production.

- lldh and dldh (L- and D-lactate dehydrogenases) to eliminate lactate production.

- pps1 and pps2 (PEP synthases) to prevent conversion of pyruvate to phosphoenolpyruvate [18].

- Attenuate TCA Cycle Entry: Down-regulate the key gene aceE (pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component) using a weak constitutive promoter (e.g., part P2) or rare start codons (GTG/TTG). This is critical, as a full knockout is lethal [18].

- Balance Anapleurosis: Fine-tune the expression of ppc (phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase) to ensure sufficient oxaloacetate supply for growth while maximizing pyruvate yield [18].

- Fermentation: Cultivate the engineered strain (e.g., PYR32) in a defined minimal medium with glucose, sucrose, or gluconate as carbon source in a fed-batch bioreactor under aerobic conditions [18].

Result: The engineered strain PYR32 produced 54.22 g/L pyruvate from glucose in 16 hours, achieving an average productivity of 3.39 g/L/h, one of the highest reported rates [18].

Case Study 2: Production of C5 Chemicals inHalomonas bluephagenesis

This case demonstrates the use of H. bluephagenesis for the complex biosynthesis of value-added chemicals from L-lysine under non-sterile conditions [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Strain and Plasmid Design: Use H. bluephagenesis TD01 as the chassis. Construct modules for the production of 5-Aminovalerate (5-AVA), 5-Hydroxyvalerate (5HV), and the copolymer P(3HB-co-5HV).

- Module 1 (5-AVA): Express the genes cadA (lysine decarboxylase) and pduP (putrescine/5-AVA transaminase) to convert L-lysine to 5-AVA via cadaverine.

- Module 2 (5HV): Express patA (5-AVA transaminase) and patD (5-AVA dehydrogenase) to convert 5-AVA to 5HV.

- Module 3 (PHA Copolymer): Co-express the 5HV module with the native PHA synthesis machinery (phaCAB) to incorporate 5HV units into the polymer chain.

- Fermentation: Perform fed-batch fermentation in a minimal medium with high salt content (e.g., 60 g/L NaCl) and glucose as the primary carbon source, supplemented with L-lysine. The process can be run open and unsterile [13].

Result: The engineered strain produced 9.76 g/L of 5-AVA and the system demonstrated the ability to synthesize the novel copolymer P(3HB-co-5HV), showcasing the platform's capability for advanced biopolymer production [13].

Figure 1: A logical workflow for selecting an appropriate microbial chassis based on process requirements, host physiology, genetic tools, and economic factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Chassis | Specific Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEVA Plasmids | Broad-host-range modular cloning vectors [2] | V. natriegens, Halomonas | Heterologous gene expression and pathway assembly across species. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing (knockouts, integrations) | V. natriegens, Halomonas | Deleting prophage regions [18] or competing metabolic genes. |

| Constitutive Promoter Library | Fine-tuned control of gene expression without inducers | V. natriegens | Down-regulating essential genes like aceE for pyruvate accumulation [18]. |

| NICE System | Nisin-inducible, high-level gene expression | LAB (e.g., L. lactis) | Controlled overexpression of pathway enzymes or difficult-to-express proteins [16]. |

| Anchoring Motifs (e.g., pgsA) | Surface display of recombinant proteins | LAB, Halomonas | Displaying antigenic proteins for vaccine development [19] [2]. |

| High-Salt LB (LBv2) | Culture medium for marine/halophilic bacteria | V. natriegens, Halomonas | Routine cultivation and maintenance; supports ultra-fast growth of V. natriegens [15]. |

Selecting the optimal chassis is a multi-parameter optimization problem that must align with the final application. The framework in Figure 1 and the summary below provide guidance.

Choose Vibrio natriegens when the primary objective is maximum volumetric productivity and speed. Its unparalleled growth and substrate uptake rates are ideal for processes where bioreactor time is a major cost driver. It is best suited for products aligned with its central metabolism (e.g., pyruvate, 2,3-butanediol) and when its salt requirement is not a prohibitive downstream concern [14] [15] [18].

Choose Halomonas spp. when the goal is low-cost, large-scale production of commodities like bioplastics. Its ability to grow under high-salt and high-pH conditions without sterilization dramatically reduces capital and operational expenses, making it the prototype for NGIB. It is the superior choice for open, continuous fermentation processes [12] [13].

Choose Lactic Acid Bacteria when the application involves food-grade products, probiotics, or mucosal delivery. Their GRAS status and expertise in food fermentations are unmatched. They are also the natural choice for efficient production of L-lactic acid as a monomer for polylactic acid (PLA) bioplastics [16] [17] [19].

In conclusion, the future of metabolic engineering is diversifying beyond traditional hosts. V. natriegens, Halomonas, and LAB each offer a compelling blend of unique innate capabilities and increasingly sophisticated engineering toolkits. The rational selection of a chassis, based on a systematic evaluation of process and product requirements, is paramount to developing economically competitive and sustainable biotechnological processes.

Within the field of microbial metabolic engineering, the selection of an appropriate host chassis is a critical determinant of success for both research and industrial applications. While Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have historically dominated as model organisms, the Gram-positive bacterium Lactococcus lactis has emerged as a superior chassis for specific therapeutic and industrial applications. This case study examines the rationale for selecting L. lactis based on a set of defined criteria, including safety profile, genetic tractability, production efficiency, and specialized functional capabilities. Originally known for its role in dairy fermentations, L. lactis is classified as a Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) organism and offers a unique combination of low immunogenic potential, efficient protein secretion, and advanced engineering tools that make it particularly suited for biomedical applications [20] [21]. Its lack of immunogenic lipopolysaccharides and low exoprotein production further distinguish it from Gram-negative alternatives, mitigating critical safety concerns for therapeutic development [20].

Advantages of the L. lactis Chassis System

Safety and Regulatory Profile

The safety credentials of L. lactis are foundational to its therapeutic application. Extensive evaluation through genomic and phenotypic analyses confirms the absence of major virulence factors and toxigenic genes in engineered strains [22]. Specific safety assessments reveal no hemolytic activity, susceptibility to clinically relevant antibiotics (including ampicillin, erythromycin, and tetracycline), and an absence of D-lactate and biogenic amine production [22]. Single-dose oral toxicity studies in rats have confirmed the absence of adverse effects, further validating its safety for human consumption [22]. These properties have supported the progression of multiple engineered L. lactis strains into clinical trials, establishing a regulatory precedent that facilitates future therapeutic development [20].

Production Capabilities and Yield Optimization

L. lactis demonstrates remarkable versatility in recombinant protein production, particularly for complex molecules requiring proper folding and disulfide bond formation. Research has shown successful production of disulfide-rich recombinant proteins from Plasmodium falciparum, with yields ranging from 1 to 40 mg/L for challenging targets that proved difficult to express in other systems [23]. A systematic evaluation of 31 malaria antigens revealed an overall production success rate of 55%, which increased significantly for cysteine-free proteins (80% success) [23]. For problematic disulfide-rich proteins, fusion with intrinsically disordered protein domains like GLURP-R0 dramatically improved yields, demonstrating the system's adaptability [23].

Table 1: Key Advantages of L. lactis as a Therapeutic Chassis

| Feature | Advantage | Application Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| GRAS Status [24] [22] | "Generally Recognized As Safe" regulatory classification | Simplified regulatory pathway for therapeutics |

| Absence of Endotoxins [20] [21] [24] | No immunogenic lipopolysaccharides | Reduced pyrogenicity and inflammatory responses |

| Protein Secretion [21] [23] | Direct export to culture medium | Simplified downstream purification |

| Low Proteolytic Activity [21] [25] | Minimal protein degradation | Enhanced recombinant protein stability |

| Genetic Tractability [20] [26] | Well-developed expression systems and engineering tools | Straightforward strain development |

Cultural conditions significantly impact protein quality and yield in L. lactis. Studies with an aggregation-prone GFP variant demonstrated that fermentative growth is superior to respiratory growth for producing functional proteins, with solubility reaching 67% at 3 hours post-induction—significantly higher than comparable E. coli systems (10-18%) [24]. Temperature optimization also plays a crucial role, with suboptimal temperatures (16°C) improving the conformational quality of soluble proteins, though with a trade-off in overall yield [24].

Metabolic Engineering Potential

The well-characterized central metabolism of L. lactis provides a platform for significant metabolic redirection. By manipulating the pyruvate node, engineers have successfully rerouted carbon flux from homolactic fermentation to alternative valuable compounds. Exemplifying this potential, disruption of the native lactate dehydrogenase (ldh) gene combined with expression of Bacillus sphaericus alanine dehydrogenase enabled a complete shift from homolactic to homoalanine fermentation [27]. Further disruption of the alanine racemase gene allowed stereospecific production (>99%) of L-alanine [27]. Similar strategies have achieved high-yield production of compounds including diacetyl, acetoin, and 2,3-butanediol through pyruvate node engineering, with the latter reaching the highest reported levels in L. lactis to date [20] [28]. The ability to switch between fermentative and respirative metabolism when hemin is present has been elegantly exploited for NAD+ regeneration, enhancing production of reduced compounds [20].

Genetic Toolbox and Engineering Methodologies

Expression Systems

The genetic toolbox available for L. lactis is comprehensive and continually expanding. The Nisin-Controlled Expression (NICE) system represents the most widely used and optimized platform, featuring tight regulation and high inducibility using sub-inhibitory amounts of nisin (0.1-5 ng/mL) [20] [21]. This system is built upon a two-component signal transduction system (NisR and NisK) that activates the PnisA promoter upon nisin induction [21]. Alternative systems including ZIREX (zinc-regulated) and ACE (agmatine-controlled) provide additional flexibility, potentially enabling sequential expression patterns when used in combination [20]. Recent vector developments have incorporated multiple affinity tags (His-tag, Strep-tag II, AVI-tag) and protease cleavage sites (TEV protease) to facilitate protein purification and labeling [25].

Advanced Genetic Engineering Techniques

Recent methodological advances have significantly expanded the genetic manipulation capabilities for L. lactis. Electroporation remains the gold standard for DNA introduction, though conjugation and a recently developed natural competence system provide alternative delivery methods [20]. For chromosomal modifications, recombineering approaches using plasmids like pCS1966 enable efficient markerless deletions or insertions through double cross-over events [20]. A particularly sophisticated advancement is the establishment of orthogonal translation systems for genetic code expansion. By incorporating the archaeal pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase–tRNAPyl pair from Methanosarcina mazei, researchers have achieved site-specific incorporation of non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) like Nε-Boc-L-lysine (BocK) into ribosomally synthesized peptides such as nisin [26]. This technique allows precise reprogramming of the amber stop codon (TAG) to incorporate novel chemical functionalities, creating "new-to-nature" antimicrobial peptides with expanded properties [26].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for L. lactis Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| NICE System [20] [21] | Tightly regulated gene expression | Controlled production of therapeutic proteins |

| pNZ-based Vectors [26] [21] | Shuttle vectors for gene expression | Heterologous protein production |

| PylRS–tRNAPyl Pair [26] | Orthogonal translation system | Incorporation of non-canonical amino acids |

| TEV Protease Site [23] [25] | Specific cleavage sequence | Removal of affinity tags from purified proteins |

| Multiple Affinity Tags [25] | Protein purification and detection | His-tag, Strep-tag II, AVI-tag for purification |

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation

Live Biotherapeutic Applications

The most advanced therapeutic application of engineered L. lactis is in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. A landmark achievement was the development of a thymidine-dependent L. lactis strain secreting human interleukin-10 (IL-10) for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment, which became the first genetically modified organism to reach clinical trials [20]. This was followed by a phase Ib/IIa study testing L. lactis secreting both IL-10 and proinsulin (AG019) for early-onset type 1 diabetes [20]. Additional clinical advances include a phase 2 trial of an oral rinse containing L. lactis engineered to secrete the mucosal protectant human trefoil factor (hTFF1), and a phase 1 trial demonstrating the safety and efficacy of L. lactis producing anti-TNF-alpha nanobodies for IBD treatment [20]. These clinical successes validate L. lactis as a robust platform for mucosal delivery of therapeutic molecules.

Vaccine and Antimicrobial Applications

L. lactis shows significant promise in vaccine development, particularly as an oral vaccine delivery vehicle that can express antigens at mucosal surfaces to stimulate both systemic and mucosal immunity [20]. The system has been successfully employed for the production of complex malaria vaccine candidates, including the disulfide-rich protein Pfs48/45, which had proven difficult to produce in other expression systems [23]. In the antimicrobial domain, engineering of the native lantibiotic nisin through lanthionine ring shuffling has generated novel antimicrobial peptides with unprecedented host ranges [20]. The incorporation of non-canonical amino acids into nisin has further expanded the chemical space of antimicrobials produced in L. lactis, creating derivatives with potentially enhanced activity spectra [26].

Production of Plant Natural Products

Beyond therapeutic proteins, L. lactis serves as an efficient platform for sustainable production of plant natural products with health-beneficial properties. The chassis has been successfully engineered for functional expression of plant and fungal membrane proteins and soluble enzymes involved in the synthesis of polyphenols, terpenoids, and esters [20] [24]. Complete functional pathways for nutraceuticals like resveratrol and anthocyanins have been assembled in L. lactis, providing an attractive alternative to plant extraction or chemical synthesis [20]. The development of metabolic biosensors for key precursors such as malonyl-CoA has enabled monitoring of intracellular precursor pools and informed strategies to improve product yield [20].

Lactococcus lactis represents a paradigm of how strategic chassis selection can accelerate and de-risk therapeutic development programs. Its compelling safety profile, coupled with continuously expanding genetic tools and demonstrated success in clinical translation, positions it as a premier platform for biomedical innovation. Future development trajectories will likely focus on enhancing product yields through systems-level metabolic engineering, expanding the genetic code for novel peptide therapeutics, and developing more sophisticated regulatory circuits for precise temporal control of therapeutic molecule delivery. The established clinical efficacy of multiple L. lactis-based therapeutics validates its utility as a versatile chassis and provides a roadmap for researchers selecting host platforms for metabolic engineering and therapeutic development initiatives. As the field advances, L. lactis is poised to play an increasingly significant role in bridging the gap between microbial engineering and clinical application.

Toolkits and Workflows: Practical Strategies for Chassis Engineering and Implementation

In the field of synthetic biology, the engineering of biological systems follows a systematic framework known as the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. This iterative engineering paradigm provides a structured approach for developing microorganisms with enhanced functionalities for diverse applications in biomanufacturing, therapeutics, and environmental remediation [29] [30]. While traditional synthetic biology has heavily focused on optimizing genetic components within a limited set of model organisms, contemporary research has demonstrated that the host organism itself—the "chassis"—is far from a passive container [2]. The chassis effect, wherein identical genetic constructs exhibit significantly different behaviors across host organisms, represents both a challenge and an opportunity for optimizing biological system performance [31] [2]. This technical guide examines the DBTL cycle through the critical lens of systematic chassis development, providing researchers with methodologies and frameworks for selecting and optimizing host organisms to maximize the success of metabolic engineering initiatives.

The DBTL Cycle: Core Principles and Phases

The DBTL cycle embodies a systematic, iterative workflow for engineering biological systems. In the Design phase, researchers define objectives and create blueprint biological systems using computational tools and domain knowledge [32]. The Build phase involves physical assembly of DNA constructs and their introduction into selected host organisms [29] [30]. During the Test phase, engineered constructs are experimentally characterized to measure performance against design objectives [30]. Finally, the Learn phase involves analyzing collected data to extract insights that inform the next design iteration [29] [33]. This cyclic process enables continuous refinement of biological systems, with each iteration incorporating knowledge gained from previous cycles to progressively improve system performance and functionality.

The Paradigm Shift: From DBTL to LDBT

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) are fundamentally reshaping the traditional DBTL cycle. The increasing success of zero-shot predictions—where models can accurately predict biological behavior without additional training—enables a paradigm shift from DBTL to "LDBT" (Learn-Design-Build-Test) [32]. In this reconfigured cycle, learning precedes design through ML algorithms that leverage vast biological datasets. Protein language models (e.g., ESM, ProGen) and structure-based design tools (e.g., ProteinMPNN, MutCompute) can now generate functional biological designs without initial experimental testing [32]. This approach potentially reduces the need for multiple iterative cycles, moving synthetic biology closer to a "Design-Build-Work" model akin to more established engineering disciplines [32].

Chassis Selection as a Critical Design Parameter

The selection of an appropriate microbial host represents a fundamental strategic decision in the DBTL cycle, with profound implications for system performance and functionality.

The Chassis Effect: Empirical Evidence

Recent comparative studies have systematically documented the chassis effect across diverse bacterial hosts. Research evaluating genetic inverter circuits across six Gammaproteobacteria species demonstrated that circuit performance metrics—including output signal strength, response time, and growth burden—varied significantly depending on the host organism [31]. Multivariate statistical analysis revealed that similarity in host physiology, rather than phylogenetic relatedness, was a better predictor of similar circuit performance [31]. This finding underscores the importance of physiological metrics over evolutionary relationships when selecting compatible chassis for synthetic biology applications.

Strategic Expansion Beyond Model Organisms

Broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology represents an emerging subdiscipline that seeks to expand the engineerable domain beyond traditional model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [2]. This approach reconceptualizes the chassis from a passive platform to an active tunable component in system design [2]. Organisms with specialized native capabilities—such as the photosynthetic capacity of cyanobacteria, the environmental robustness of halophiles, or the specialized metabolism of Streptomyces species—can serve as superior chassis for specific applications by providing pre-evolved phenotypes that would be difficult to engineer into conventional hosts [2] [6].

Table 1: Chassis Selection Criteria for Different Application Domains

| Application Domain | Preferred Chassis Traits | Example Organisms | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomanufacturing | High precursor availability, Robust growth in bioreactors, High burden tolerance | Corynebacterium glutamicum, Pseudomonas putida | Enhanced flux to target compounds, Operational stability [34] |

| Therapeutics | Biosafety profile, Human microbiome compatibility, Functional protein folding | Engineered Lactobacillus spp., Bacteroides spp. | Suitable for in vivo applications, Proper post-translational modifications [2] |

| Environmental Remediation | Stress tolerance (temperature, salinity, pH), Biofilm formation, Substrate utilization diversity | Halomonas bluephagenesis, Rhodopseudomonas palustris | Functionality in non-laboratory conditions [2] |

| Natural Product Discovery | Native secondary metabolism, Precursor supply, Compatibility with biosynthetic machinery | Streptomyces aureofaciens, S. coelicolor | Efficient expression of complex pathways [6] |

DBTL Cycle Implementation: Phase-Specific Methodologies

Design Phase: Knowledge-Driven and Computational Approaches

The initial Design phase benefits significantly from strategic approaches that maximize prior knowledge utilization:

Knowledge-Driven DBTL: This approach incorporates upstream in vitro investigation before full DBTL cycling to gain mechanistic insights [33]. For dopamine production in E. coli, researchers first used cell-free protein synthesis systems to test different enzyme expression levels, informing subsequent in vivo strain engineering [33].

Mechanistic Kinetic Modeling: For metabolic pathway optimization, kinetic models simulate pathway behavior under different enzyme expression scenarios, providing a framework for in silico testing of combinatorial designs before physical assembly [35].

Host-Agnostic Genetic Design: BHR synthetic biology employs genetic parts and devices (e.g., Standard European Vector Architecture plasmids) that function across diverse hosts, facilitating chassis comparison and selection [2].

Build Phase: High-Throughput DNA Assembly and Chassis Engineering

Advanced genetic toolkits have dramatically accelerated the Build phase:

Automated DNA Assembly: Modular cloning systems like BASIC (Biopart Assembly Standard for Idempotent Cloning) enable rapid, standardized assembly of genetic constructs from standardized parts [31].

Chassis Optimization: Strategic genome engineering creates specialized chassis with enhanced capabilities. For type II polyketide production, researchers developed Streptomyces aureofaciens Chassis2.0 through in-frame deletion of two endogenous polyketide gene clusters, reducing precursor competition while maintaining high production capacity [6].

High-Throughput Transformation: Electroporation protocols optimized for diverse bacterial species enable efficient introduction of DNA libraries into non-model hosts [31].

Test Phase: Analytical and Phenotypic Characterization

Comprehensive testing generates the data necessary for informed learning:

Multi-Omics Characterization: High-throughput sequencing and mass spectrometry generate large amounts of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data at the single-cell level [29].

High-Throughput Screening: Automated cultivation systems in multi-well plates coupled with continuous fluorescence and absorbance measurements enable parallel characterization of hundreds of strains under standardized conditions [31] [33].

Cell-Free Prototyping: Cell-free expression systems accelerate testing by bypassing cell membrane barriers and internal regulation, allowing direct characterization of enzyme activities and pathway performance without the constraints of living cells [32] [33].

Learn Phase: Machine Learning and Data Integration

The Learn phase represents the critical knowledge extraction step that informs subsequent cycles:

Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling: ML algorithms, particularly gradient boosting and random forest models, have demonstrated strong performance in predicting strain performance from limited datasets, enabling more intelligent design selection for subsequent DBTL cycles [35].

Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Techniques such as Principal Coordinates Analysis and Procrustes Superimposition enable researchers to correlate chassis physiology with genetic circuit performance, identifying key physiological predictors of system behavior [31].

Mechanistic Insight Extraction: Beyond performance optimization, the Learn phase can reveal fundamental biological insights. For example, analysis of dopamine production strains revealed the impact of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on translation efficiency [33].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches in the DBTL Cycle

| ML Method | Application in DBTL | Advantages | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | Combinatorial pathway optimization [35] | Robust to training set biases and experimental noise | Outperforms other methods in low-data regimes [35] |

| Random Forest | Predicting metabolic flux optimization [35] | Handles high-dimensional data well | Comparable performance to gradient boosting [35] |