Resolving Toxic Intermediate Accumulation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Synthetic Pathways

This article provides a comprehensive examination of toxic intermediate accumulation, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology.

Resolving Toxic Intermediate Accumulation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Synthetic Pathways

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of toxic intermediate accumulation, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. It explores the fundamental mechanisms by which toxic intermediates disrupt cellular function, from inhibiting growth to causing genetic instability. The content details strategic methodologies for pathway design and control, including dynamic optimization and computational modeling, to prevent intermediate toxicity. Furthermore, it covers essential troubleshooting frameworks for identifying and resolving flux imbalances, and outlines rigorous validation protocols using orthogonal analytical methods and comparative toxicity assessments. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes foundational knowledge with practical applications to enhance the design and optimization of robust synthetic pathways for bioproduction and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Core Challenge: The Origins and Impacts of Toxic Intermediate Accumulation

Defining Toxic Intermediates and Their Cellular Consequences

FAQs: Understanding the Core Problem

What is a toxic intermediate in the context of synthetic pathways? A toxic intermediate is a transient, highly reactive molecule formed during a chemical reaction in a synthetic or metabolic pathway that can cause cellular damage. Unlike final products, these intermediates are short-lived, do not appear in the overall reaction equation, and are consumed in subsequent steps [1]. Their toxicity arises from their high reactivity, which can disrupt essential cellular structures and functions.

What are the primary cellular consequences of toxic intermediate accumulation? The accumulation of toxic intermediates primarily triggers two fundamental pathological processes [2]:

- Acute Lethal Injury: Interference with cellular energy metabolism (e.g., inhibition of glycolysis, mitochondrial respiration, or oxidative phosphorylation), leading to ATP depletion, failure of ion pumps, cellular swelling, and ultimately, cell death [2].

- Autoxidative Cellular Injury: Many reactive intermediates are electrophiles or free radicals that potentiate oxygen toxicity. They deplete intracellular antioxidants like glutathione, causing oxidative stress, damage to cell membranes (lipid peroxidation), impairment of calcium pumps, DNA damage, and mutations [2].

How can I predict if my synthetic pathway might generate toxic intermediates? Computational tools are increasingly valuable for predicting potential toxic intermediates during pathway design. You can leverage:

- Retrosynthesis Software: Uses biochemical big-data to predict potential biosynthetic routes and their intermediates [3].

- Compound & Pathway Databases: Consult databases like KEGG, MetaCyc, and PubChem to research known reactions and compound properties [3].

- Enzyme Engineering Tools: Use platforms like BRENDA and UniProt to investigate enzyme functions and substrate specificities that might lead to reactive species [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Suspected Metabolic Activation Leading to Cytotoxicity

Problem: Cell viability drops in cultures exposed to a precursor compound, suggesting the synthesis pathway is generating a toxic intermediate through metabolic activation.

Background: Many chemicals are bioactivated by cellular enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450s) into reactive intermediates like free radicals or electrophiles, which then inhibit cellular functions and damage macromolecules [4].

Investigation Protocol:

- Confirm Covalent Binding: Use radiolabeled (e.g., ¹⁴C) precursor compounds. After exposure, precipitate cellular proteins and measure associated radioactivity to indicate covalent adduct formation by reactive intermediates [4].

- Assay Glutathione Depletion: Measure intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels spectrophotometrically or via HPLC. A rapid decline in GSH is a hallmark of electrophilic intermediate formation and oxidative stress [2] [4].

- Detect Lipid Peroxidation: Quantify thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) or use fluorescent probes (e.g., C11-BODIPY⁵⁸¹/⁵⁹¹) in cell membranes to confirm free radical-mediated membrane damage [4].

- Measure Calcium Homeostasis: Use fluorescent dyes (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) and confocal microscopy to detect a sustained rise in cytosolic Ca²⁺, a key event in both autoxidative and acute lethal cell injury [2] [5].

Solution Strategies:

- Co-factor Supplementation: Supplement culture media with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or antioxidants to bolster cellular glutathione reserves and redox capacity [4].

- Enzyme Inhibition: Co-incubate with specific inhibitors of metabolic activation enzymes (e.g., CYP450 inhibitors like 1-aminobenzotriazole) to block the formation of the toxic intermediate [4].

- Pathway Redesign: Use computational retrosynthesis tools to design a novel pathway that avoids the formation of the problematic intermediate structure [3].

Issue 2: Off-Target Activity and Apoptosis in Target Tissues

Problem: The desired final product is synthesized, but off-target toxicity (e.g., in hepatocytes or thymocytes) is observed, potentially due to a stable intermediate activating unintended death pathways.

Background: Toxic intermediates can trigger programmed cell death (apoptosis) by mechanisms such as endonuclease activation, often mediated by a sustained elevation of cytosolic calcium concentration [5].

Investigation Protocol:

- Characterize Cell Death Morphology: Use fluorescence microscopy with stains like Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide to distinguish apoptotic (chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation) from necrotic cells.

- Confirm Apoptosis Biochemically:

- Caspase-3/7 Activation: Use a commercial luminescent or fluorescent assay to measure the activity of these executioner caspases.

- DNA Fragmentation Analysis: Perform a TUNEL assay or gel electrophoresis to detect internucleosomal DNA cleavage.

- Quantify Cytosolic Ca²⁺: As in the previous protocol, use fluorescent indicators to confirm the role of calcium as a key secondary messenger in the toxicity [5].

Solution Strategies:

- Structural Masking: Modify the functional groups on the precursor to make it less recognizable to the off-target activation enzyme. This is a core principle of toxicological chemistry [6].

- Calcium Chelation: Test if extracellular or intracellular calcium chelators (e.g., BAPTA-AM) can rescue the cells, confirming the mechanism and suggesting a temporary mitigation strategy [5].

- Prodrug Approach: Redesign the synthetic sequence to use a prodrug that is only activated in the target tissue, minimizing systemic exposure to the intermediate [6].

Issue 3: Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Production Cell Lines

Problem: Engineered microbial production strains (e.g., E. coli, yeast) show growth arrest and reduced yield, with evidence of high oxidative stress during synthesis.

Background: Synthetic pathways can impose a high metabolic burden, disrupting native electron transport chains and leading to electron leakage. This, combined with redox-active intermediates, can generate superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals, damaging DNA, proteins, and lipids [2] [4].

Investigation Protocol:

- Quantify ROS Generation: Use cell-permeable fluorescent probes (e.g., H₂DCFDA for general ROS, MitoSOX Red for mitochondrial superoxide) and flow cytometry for quantitative measurement.

- Analyze Antioxidant Defense: Measure the activity and expression levels of key antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase.

- Profile Central Carbon Metabolites: Use LC-MS or GC-MS to perform metabolomics. Look for accumulation of metabolites just before the blockage, which can indicate the toxic intermediate, and check for depletion of TCA cycle intermediates, indicating energy metabolism disruption [2].

Solution Strategies:

- Overexpress Antioxidant Enzymes: Co-express genes for SOD and catalase in the production host to enhance its ability to scavenge ROS [4].

- Promote Cofactor Regeneration: Engineer pathways to improve the regeneration of redox cofactors (NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+) to reduce electron leakage and restore redox balance.

- Dynamic Pathway Control: Implement a genetic circuit that delays the expression of the problematic synthetic pathway until the late growth phase, uncoupling production from rapid growth and its associated oxidative metabolism.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Investigating Toxic Intermediates

| Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Precursor for glutathione synthesis; bolsters cellular defense against electrophilic intermediates and oxidative stress [4]. |

| Glutathione Assay Kit | For quantifying intracellular glutathione (GSH/GSSG) levels, a key indicator of oxidative stress and electrophile burden [4]. |

| H₂DCFDA / MitoSOX Red | Fluorescent probes for detecting general reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial superoxide, respectively [4]. |

| Caspase-3/7 Assay Kit | Luminescent or fluorescent assay to measure caspase enzyme activity, confirming the activation of apoptosis [5]. |

| Fluo-4 AM | Cell-permeable, fluorescent calcium indicator for monitoring changes in cytosolic Ca²⁺ concentration, a central event in toxicity [5]. |

| Cytochrome P450 Inhibitors | e.g., 1-Aminobenzotriazole; used to inhibit bioactivation enzymes and confirm metabolic activation of a precursor to a toxic intermediate [4]. |

| BAPTA-AM | Cell-permeable calcium chelator; used to investigate the role of calcium in mediating cell death [5]. |

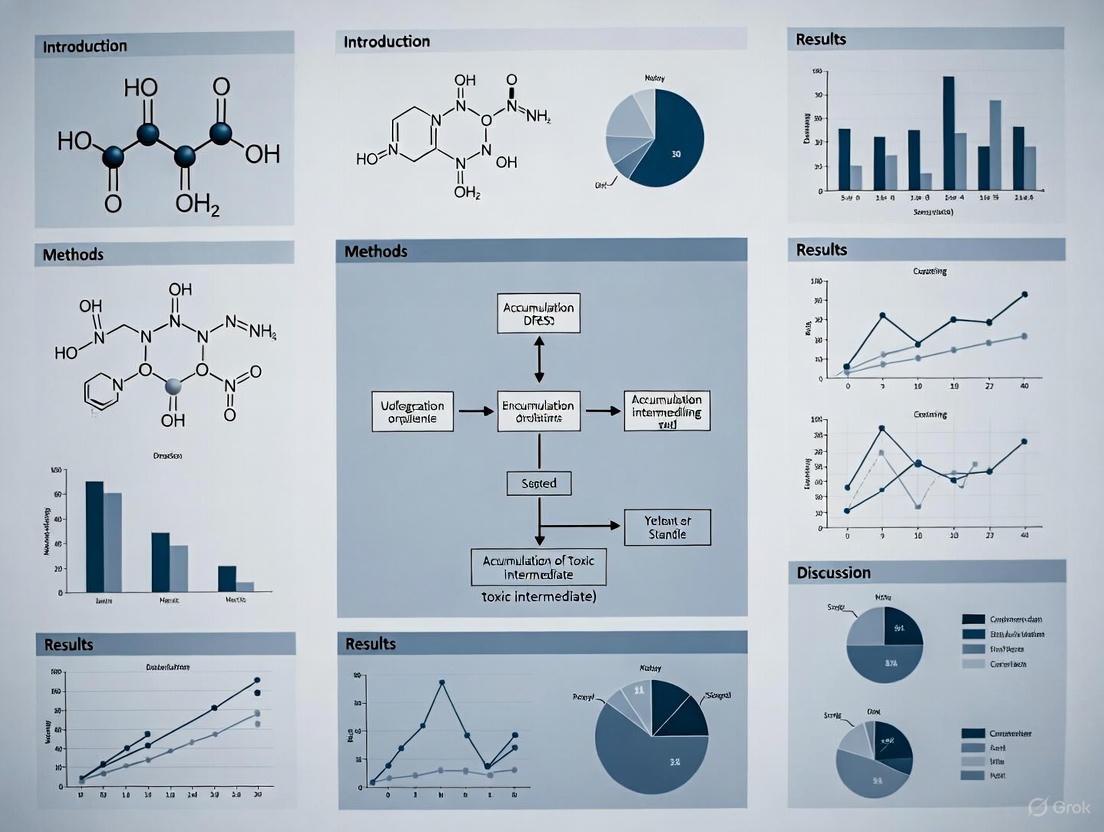

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Cellular Toxicity Pathways

Diagram 2: Investigation Workflow

Evolutionary Principles of Natural Pathway Regulation to Minimize Toxicity

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the core evolutionary principles that can be applied to minimize toxicity in synthetic pathways? Evolutionary principles provide a framework for understanding and intervening in biological systems to achieve desired outcomes, such as reducing the accumulation of toxic intermediates in synthetic pathways. Four key themes are particularly relevant [7]:

- Variation: Natural phenotypic variation, stemming from genetic differences, plasticity, and other forms of inheritance, determines how a system responds to selective pressures.

- Selection: Selective pressures can be managed to favor pathways or organisms with reduced toxic byproduct formation.

- Connectivity: Gene flow and interactions between different pathways or cellular compartments can influence the spread of beneficial or detrimental traits.

- Eco-evolutionary Dynamics: The traits of organisms (e.g., engineered microbes) and their resulting products can feedback to influence their own environment and subsequent evolution.

FAQ 2: Why does toxicity often arise from metabolic pathways, and how can this be predicted? Toxicity in synthetic pathways often arises not from the parent compounds, but from reactive metabolites generated during metabolism [8]. Metabolic enzymes, such as the cytochrome P450 family, evolved to convert chemicals into more soluble forms for clearance. However, in some cases, this process—known as bioactivation—generates metabolites that are dangerously reactive to DNA, RNA, and proteins [8]. Predicting this requires toxicity assays that incorporate representative metabolic enzymes to produce these reactive metabolites.

FAQ 3: Our reaction mixture is more cytotoxic than predicted from its individual components. What is the cause? This is a common finding. The cytotoxicity of a complete reaction mixture is often significantly underestimated when assessed solely on the toxicity of single substances [9]. This is due to synergistic effects between components in the mixture, where the combined toxic impact is greater than the sum of their individual effects. Non-covalent interactions between compounds can facilitate these harmful effects [9]. Therefore, safety assessments must evaluate the final mixture, not just its parts.

FAQ 4: What is a key evolutionary concept for understanding suboptimal pathway performance? A key unifying concept is phenotypic mismatch [7]. This describes a mismatch between an organism's current phenotypic traits (e.g., its native metabolic enzyme levels) and the traits that would be optimal for a new environment (e.g., your engineered synthetic pathway). When this mismatch is large, the system is poorly adapted, leading to issues like toxic intermediate accumulation and reduced yield [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting High Cytotoxicity in Catalytic Reaction Mixtures

Problem: The final reaction mixture shows unacceptably high cytotoxicity, despite the individual components appearing relatively safe.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Assess Mixture, Not Just Components | Do not rely only on the cytotoxicity (e.g., CC50 values) of individual substances. Test the actual chemical reaction mixture at its real molar ratios, as synergistic effects are common [9]. |

| 2. Use Predictive Models | Employ the Concentration Addition (CA) model for a rapid, preliminary safety evaluation. While it may not capture all synergies, it provides a conservative risk estimate and is a good starting point [9]. |

| 3. Identify Toxic Synergists | Systematically screen combinations of reagents to identify which components are interacting to produce enhanced toxicity. Pay special attention to catalysts and solvents [9]. |

| 4. Consider Alternative Pathways | Evaluate multiple synthetic routes to your target product. A different catalytic reaction or set of reagents may achieve the same goal with a significantly improved toxicity profile [9]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Unexpected Metabolic Toxicity in Biocatalysis

Problem: A biosynthetic pathway in an engineered microbe produces the desired product but also generates genotoxic metabolites, damaging microbial DNA and crashing the culture.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Genotoxicity | Use a high-throughput genotoxicity assay like the GreenScreen (GS) assay. This eukaryotic assay uses a GFP reporter to detect growth arrest and DNA damage (GADD) and can identify toxins that bacterial Ames tests might miss [8]. |

| 2. Profile Metabolites | Use LC-MS/MS to map the complete chemical pathway and identify the specific reactive metabolites causing the damage. This provides a roadmap for pathway re-engineering [8]. |

| 3. Introduce Detoxification | Engineer a detoxification step into the pathway. This mimics natural evolutionary solutions; for example, enhancing the expression of a bioconjugation enzyme like glucuronyltransferase to derivatize and safely eliminate a reactive intermediate [8]. |

| 4. Apply Selective Pressure | Use directed evolution or adaptive laboratory evolution. Apply a gentle selective pressure for growth while the pathway is active. This will enrich for mutants that have naturally evolved reduced toxicity, for example, through mutations that down-regulate a problematic enzyme or up-regulate a protective one [7]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cytotoxicity Assessment of Chemical Reaction Mixtures

Purpose: To evaluate the integrated cytotoxicity of a catalytic reaction mixture and its individual components, accounting for synergistic effects [9].

Materials:

- Reaction components (starting materials, catalyst, base, solvent)

- Appropriate human cell lines (e.g., HepG2 hepatocytes)

- Cell culture media and reagents

- 96-well microtiter plates

- Incubator

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare the complete reaction mixture at the final molar ratios used in your synthesis.

- Also, prepare separate solutions of each individual reaction component.

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a standardized density and allow them to adhere overnight.

- Treatment: Treat cells with a dilution series of (a) the complete reaction mixture and (b) each individual component. Include a negative control (vehicle only).

- Incubation: Incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Viability Assay: Perform a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT, resazurin).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50) for each individual component and the mixture.

- Use the Concentration Addition (CA) model to predict the expected mixture toxicity based on individual CC50 values.

- Compare the predicted CC50 to the experimentally observed CC50. A lower observed CC50 indicates synergistic toxicity [9].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Genotoxicity Screening Using GreenScreen Assay

Purpose: To detect genotoxic effects of metabolites or reaction products in a high-throughput, eukaryotic system [8].

Materials:

- Test compound (e.g., isolated reaction intermediate)

- GreenScreen assay kit (Gentronix) or engineered yeast cells with a GFP-GADD plasmid

- Metabolic activation system (e.g., human liver S9 fraction or microsomes)

- Microtiter plates (96-well or 384-well)

- Fluorescence plate reader

Method:

- Metabolic Activation: Pre-incubate the test compound with a metabolic activation system (e.g., S9 fraction) to generate potential reactive metabolites.

- Cell Exposure: Add the metabolized compound to the GreenScreen reporter cells seeded in a microtiter plate.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate for a defined period (typically 24-48 hours) to allow for genotoxin-induced expression of the GADD reporter.

- Fluorescence Measurement: Read the plate using a fluorescence plate reader to quantify GFP expression.

- Data Interpretation: A significant increase in fluorescence in the treated samples compared to the negative control indicates genotoxicity. This assay can be used to rank the genotoxic potential of different pathway intermediates [8].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Toxicity Mitigation via Pathway Evolution

Mixture Toxicity Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Metabolic Toxicity and Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs) | Source of multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes and cyt P450 reductase for metabolic bioactivation of test compounds [8]. | Used in cytotoxicity and genotoxicity assays to generate human-relevant metabolites. |

| S9 Liver Fraction | A liver homogenate fraction containing a broad array of metabolic enzymes, including cyt P450s and bioconjugation enzymes [8]. | Provides a comprehensive metabolic profile for general toxicity screening. |

| Supersomes | Microsome-like vesicles engineered to express a single, specific cytochrome P450 enzyme and its reductase [8]. | Ideal for studying the metabolic contribution and potential toxicity linked to a specific P450 enzyme. |

| GreenScreen Assay | A eukaryotic bioassay that uses a GFP reporter gene to detect genotoxicity via the growth arrest and DNA damage (GADD) pathway [8]. | High-throughput screening for DNA damage caused by compounds or their metabolites. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry for separating, identifying, and quantifying metabolites in a complex mixture [8]. | Elucidating chemical pathways of toxicity by mapping all metabolites formed from a parent compound. |

This technical support center document addresses the critical challenge of toxic intermediate accumulation in engineered metabolic pathways, focusing on L-homoserine and aspartate-β-semialdehyde (ASA) in the aspartate biosynthetic pathway. These toxicity issues present significant bottlenecks in metabolic engineering projects aimed at producing valuable amino acids and other bioproducts. The following troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols provide targeted strategies to identify, mitigate, and resolve these specific toxicity mechanisms, enabling more efficient and robust pathway engineering.

Troubleshooting Guide: Toxicity Symptoms and Solutions

Table 1: Common Problems and Recommended Actions

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth inhibition in presence of L-homoserine | L-homoserine interfering with protein synthesis or ammonium assimilation [10] | Implement adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE); Overexpress threonine conversion pathway (thrABC) [10] | Measure growth rate (OD600) in minimal media ± L-homoserine |

| Inability to utilize L-homoserine as nitrogen source | Inefficient ammonium release from L-homoserine catabolism [10] | Activate threonine degradation pathway II and glycine cleavage system [10] | Growth assay with L-homoserine as sole nitrogen source |

| Low flux towards target amino acids (Lys, Met, Thr, Ile) | Feedback inhibition or enzyme regulation [11] [12] | Use feedback-resistant enzyme mutants (e.g., AK, HSD); Modulate pathway expression | Measure intermediate concentrations (e.g., ASA, HSE) via HPLC/MS |

| Insufficient inhibitor specificity for ASADH | Off-target effects of lead compounds [12] | Leverage structural differences in active sites between pathogen and host ASADH [12] | Enzymatic inhibition assays with purified ASADH from target and model organisms |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are L-homoserine and ASA considered toxic intermediates in microbial systems?

A1: L-homoserine toxicity manifests through multiple mechanisms. In E. coli, it potently inhibits growth by potentially competing with leucine for tRNA aminoacylation, disrupting protein synthesis fidelity. It can also inhibit key metabolic enzymes like NADP+-glutamate dehydrogenase by up to 50% at 10 mM concentration, impairing ammonium assimilation [10]. ASA toxicity is less documented but its accumulation likely disrupts cellular redox balance and drains metabolic precursors.

Q2: What makes ASADH an attractive target for antibiotic development?

A2: Aspartate-β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ASADH) is essential for the biosynthesis of lysine, methionine, threonine, and isoleucine in prokaryotes, fungi, and some plants. Crucially, this complete aspartate pathway is absent in humans, making ASADH an ideal selective target for antimicrobial, fungicidal, and herbicidal agents with minimal risk of off-target effects in mammals [13] [12]. Deletion of the asd gene encoding ASADH is lethal in many pathogens [12].

Q3: How can I engineer a microbial host to overcome L-homoserine toxicity?

A3: A proven strategy involves Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE). One successful approach evolved an E. coli strain capable of growing with L-homoserine as the sole nitrogen source. Key genomic modifications included a truncation in the thrL gene, resulting in a longer leader peptide (thrL) that constitutively activated the threonine operon (thrABC*). This enhanced conversion of toxic L-homoserine into threonine, alleviating toxicity and enabling growth [10].

Q4: What computational tools are available for designing synthetic pathways that avoid toxic intermediate accumulation?

A4: Bioinformatics tools like Pathway Tools support metabolic reconstruction and flux-balance analysis to predict pathway bottlenecks [14]. Other specialized software includes:

- RetroPath/XTMS: Scores enzyme performance and predicts intermediate toxicity [15].

- Metabolic Tinker: Prioritizes pathways based on thermodynamic feasibility [15].

- GEM-Path: Incorporces flux efficiency calculations for pathway ranking [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) to Alleviate L-Homoserine Toxicity

Background: This protocol describes an ALE workflow to generate E. coli strains resistant to L-homoserine inhibition and capable of utilizing it as a nitrogen source [10].

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli MG1655 (or other target strain)

- Media:

- LB Medium: For routine cultivation.

- M9 Minimal Medium: Contains 0.2% (w/v) glucose and a permissive nitrogen source (e.g., 10 mM L-aspartate) for initial cultivation.

- Selection Medium: M9 Minimal Medium with L-homoserine as the sole nitrogen source.

- Equipment: Turbidostat or serial batch culture setup, spectrophotometer.

Procedure:

- Initial Cultivation: Grow the wild-type population in the permissive M9 medium in a turbidostat until the growth rate stabilizes.

- Selection Pressure: Transition the culture to the selection medium, where L-homoserine serves as the sole nitrogen source.

- Continuous Evolution: Maintain the culture in a turbidostat mode, allowing the population to evolve over multiple generations. Monitor growth (OD600) regularly.

- Isolation and Screening: Plate samples periodically on solid selection medium. Isolate single colonies and screen for improved growth in liquid medium containing L-homoserine.

- Genomic Analysis: Sequence the genomes of evolved clones to identify causative mutations (e.g., mutations in the thrL region) [10].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Characterization of Homoserine Dehydrogenase (HSD)

Background: Understanding the enzymatic properties of HSD is crucial for optimizing flux through the aspartate pathway and mitigating bottlenecks [11].

Materials:

- Purified HSD Enzyme: Overexpressed and purified from Bacillus subtilis (BsHSD) or your target organism.

- Reaction Buffer: 100 mM CHES buffer, pH 9.0, containing 400 mM NaCl [11].

- Substrates: L-homoserine (L-HSE) and NADP+.

- Equipment: UV/Vis spectrophotometer capable of monitoring absorbance at 340 nm.

Procedure:

- Enzyme Assay: Standard reactions contain 100 mM L-HSE, 1 mM NADP+, 400 mM NaCl, 0.5 μM BsHSD in 100 mM CHES buffer, pH 9.0.

- Activity Measurement: Monitor the increase in absorbance at 340 nm (indicating NADPH production) at 25°C.

- Kinetic Analysis: Vary the concentration of one substrate while keeping the other constant.

- For L-HSE kinetics: Use 0.5-100 mM L-HSE with a fixed, saturating NADP+ concentration.

- For NADP+ kinetics: Use 0.05-2 mM NADP+ with a fixed, saturating L-HSE concentration.

- Data Analysis: Calculate initial velocities. Plot data and fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine Km and Vmax values [11].

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters of Bacillus subtilis Homoserine Dehydrogenase (BsHSD)

| Parameter | Substrate | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Km | L-Homoserine | 35.08 ± 2.91 mM | pH 9.0, 400 mM NaCl [11] |

| Km | NADP+ | 0.39 ± 0.05 mM | pH 9.0, 400 mM NaCl [11] |

| Vmax | L-Homoserine | 2.72 ± 0.06 μmol/min⁻¹ mg⁻¹ | pH 9.0, 400 mM NaCl [11] |

| Vmax | NADP+ | 2.79 ± 0.11 μmol/min⁻¹ mg⁻¹ | pH 9.0, 400 mM NaCl [11] |

| Cofactor Preference | NADP+ vs NAD+ | Exclusively prefers NADP+ [11] | - |

| Optimal pH | - | 9.0 [11] | - |

| Optimal [NaCl] | - | 0.4 M [11] | - |

Pathway Visualization and Mechanisms

The diagram below illustrates the aspartate biosynthesis pathway, highlighting the positions of homoserine and ASA, their connectivity to essential amino acids, and their associated toxicity mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Investigating Pathway Toxicity

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| M9 Minimal Medium | Defined mineral medium for controlled growth experiments. | Assessing growth defects and nitrogen source utilization (e.g., with L-homoserine as sole N source) [10]. |

| L-Homoserine | Non-canonical amino acid; pathway intermediate and toxicant. | Used in toxicity assays and as a selection pressure in ALE experiments [10]. |

| NADP+ | Essential cofactor for ASADH and HSD enzymes. | Required for in vitro enzyme activity and kinetic assays [11] [12]. |

| S-methyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (SMCS) | Mechanism-based inhibitor that covalently modifies ASADH active site (Cys134) [13]. | Probing ASADH enzyme mechanism and structure-based inhibitor design [13] [12]. |

| Pathway Tools Software | Bioinformatics software for metabolic reconstruction and analysis [14]. | Developing organism-specific metabolic databases and predicting pathway bottlenecks. |

| AntiSMASH Software | Bioinformatics tool for identifying and annotating biosynthetic gene clusters [15]. | Discovering native regulatory elements and potential resistance mechanisms in host genomes. |

The Link Between Intermediate Accumulation, Metabolic Flux Imbalance, and Cell Death

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my engineered microbial production strain suddenly stop growing or show a rapid drop in viability?

A: Sudden growth arrest or cell death often results from the accumulation of toxic metabolic intermediates. When a heterologous pathway is introduced or a native pathway is overdriven, flux imbalances can occur. This means that one enzyme in the pathway operates much faster than the next, causing a backlog of an intermediate compound. Some of these intermediates can be inherently toxic or can disrupt central metabolism by CoA depletion, membrane disruption, or generating reactive oxygen species, ultimately triggering apoptosis or necrosis [16]. Diagnostic steps include:

- Measurement: Use LC-MS or GC-MS to profile metabolites and identify the accumulating intermediate [17].

- Inspection: Check for known toxic molecules in your pathway, such as acyl-CoA compounds or reactive aldehydes.

Q2: How can I determine which specific enzyme in my pathway is causing a bottleneck?

A: Pinpointing the bottleneck enzyme requires a combination of metabolic flux analysis and targeted enzyme quantification.

- 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): This is the gold-standard technique for quantifying intracellular reaction rates (fluxes). By feeding cells with 13C-labeled glucose (e.g., [1-13C] glucose) and tracking the label distribution in proteinogenic amino acids or other biomass components via GC-MS, you can calculate the in vivo flux through your pathway of interest. A significantly lower flux value for a particular reaction indicates a bottleneck [17].

- Enzyme Activity Assays: Complement 13C-MFA by measuring the in vitro activity of each enzyme in your pathway from cell lysates. A low specific activity can confirm a bottleneck.

Q3: What are the most effective strategies to prevent intermediate accumulation and cell death?

A: The most effective modern strategies are combinatorial and proactive, moving beyond sequential debugging.

- Combinatorial Pathway Optimization: Instead of optimizing one gene at a time, create libraries that simultaneously vary multiple pathway components. This includes testing different enzyme homologs (from various organisms) and tuning expression levels using diverse promoters and Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS) [16].

- Predictive Computational Design: Use bioinformatics tools to select better parts from the start. Tools like antiSMASH can identify natural enzyme variants, while RetroPath and GEM-Path can predict efficient pathways and flag potential thermodynamic or toxicity issues [15].

- Dynamic Metabolic Control: Implement synthetic genetic circuits that sense the buildup of a toxic intermediate and respond by downregulating upstream enzymes or activating rescue pathways [18].

Q4: What is the molecular link between a metabolic imbalance and the activation of cell death?

A: Metabolic imbalances are sensed by the cell as a severe form of stress, engaging core cellular decision-making machinery.

- Mitochondrial Checkpoints: The Bcl-2 protein family is a key integrator. Stress signals can activate pro-apoptotic proteins like Bax and Bak, which induce Mitochondrial Outer Membrane Permeabilization (MOMP). This releases cytochrome c into the cytosol, triggering the caspase cascade and apoptosis [19] [20].

- Energy and Redox Crisis: Flux imbalances can lead to a depletion of ATP or a reduction in NADPH pools, preventing cells from managing oxidative stress. This energy catastrophe can push the cell into a more inflammatory form of death like necrosis or ferroptosis [19] [21].

- Direct Signaling by Oncometabolites: In some contexts, accumulated metabolites can directly inhibit or activate enzymes that regulate cell death pathways [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Flux Imbalance

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product yield, slow growth | General pathway imbalance, minor toxicity | 13C-MFA to map fluxes; RNA-seq to see if stress responses are activated | Fine-tune expression levels using combinatorial RBS or promoter libraries [16] |

| Rapid cell death after pathway induction | Acute accumulation of a highly toxic intermediate | Targeted metabolomics to identify and quantify the peak intermediate | Screen for alternative enzyme homologs that do not produce the toxic compound; implement a dynamic control circuit [16] [18] |

| Reduced growth rate, but high viability | Metabolic burden, resource competition | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to model nutrient allocation | Optimize chassis metabolism by gene knockouts to eliminate competing pathways using tools like OptKnock [15] |

| Unstable production over long fermentation | Genetic instability or evolving population heterogeneity | Whole-genome sequencing of endpoint populations; Flow cytometry of reporter strains | Use genome-integrated pathways instead of plasmids; engineer auxotrophies to link production to growth [16] |

Experimental Protocol: 13C-MFA for Flux Quantification

This protocol, based on established methodologies [17], allows for precise quantification of metabolic fluxes, enabling the identification of bottlenecks.

1. Experimental Design and Cell Cultivation

- Tracer Selection: Use at least two parallel cultures with different 13C-labeled glucose tracers (e.g., [1-13C] glucose and [U-13C] glucose) for optimal flux resolution [17].

- Culture Conditions: Grow your engineered microbe in a controlled bioreactor or chemostat to ensure steady-state growth. Harvest cells during mid-exponential phase.

2. Sample Preparation and Derivatization

- Hydrolysis: Hydrolyze cell pellet biomass (~10-20 mg) in 6M HCl at 105°C for 24 hours to release protein-bound amino acids.

- Derivatization: Convert the hydrolyzed amino acids into volatile tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) derivatives for GC-MS analysis.

3. GC-MS Measurement and Data Processing

- Measurement: Inject the derivatized samples into a GC-MS system.

- Data Extraction: Quantify the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of the proteinogenic amino acids from the resulting chromatograms. These MIDs represent the patterns of 13C incorporation.

4. Computational Flux Analysis

- Software: Use dedicated 13C-MFA software like Metran (available from MIT) [17].

- Modeling: Input the measured MIDs, a metabolic network model, and extracellular flux data (e.g., growth rate, substrate uptake).

- Optimization: The software will perform a non-linear regression to find the set of intracellular fluxes that best fits the experimental labeling data.

- Statistics: Compute confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes to determine their precision and identify which fluxes are significantly constrained.

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, BRENDA | Reference databases for pathway (KEGG, MetaCyc) and enzyme (BRENDA) information [3]. |

| Computational Tools | antiSMASH | Identifies and annotates biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data [15]. |

| RetroPath/XTMS, GEM-Path | Platform for designing and ranking novel biosynthetic pathways [15]. | |

| RBS Calculator | Predicts and designs ribosome binding sites to fine-tune translation rates [15]. | |

| Analytical Standards | 13C-Labeled Glucose | Essential tracer for 13C-MFA experiments (e.g., [1-13C], [U-13C]) [17]. |

| Software | Metran | Software platform for performing 13C-MFA and calculating metabolic fluxes [17]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Imbalance to Cell Death Pathway

Combinatorial Pathway Optimization Workflow

How Toxic Intermediates Disrupt Genome Stability and Promote Rearrangements

In both metabolic and DNA repair pathways, the accumulation of toxic intermediates presents a significant threat to genomic integrity. These compounds, which are transient chemical species formed during normal biochemical processes, can cause severe cellular damage if their concentrations are not properly regulated. In synthetic biology, engineering novel pathways often inadvertently leads to the accumulation of such intermediates, resulting in growth defects, mutagenesis, and ultimately, genomic rearrangements that compromise both research and production outcomes. Understanding how these intermediates disrupt cellular processes and implementing strategies to mitigate their effects is therefore crucial for successful pathway engineering and maintenance of genome stability.

Key Mechanisms of Toxicity and Genome Disruption

DNA Replication and Repair Interference

Toxic intermediates can directly interfere with DNA replication and repair processes. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, studies on the Srs2 DNA helicase demonstrate how disrupted recombination intermediates lead to genomic instability. A helicase-dead mutant (srs2K41A) proves lethal in diploid cells but not in haploid cells, specifically due to accumulated inter-homolog joint molecule intermediates. These structures interfere with chromosome segregation and promote gross chromosomal rearrangements [22] [23].

The Srs2 helicase normally prevents toxic recombination intermediates by disrupting Rad51 filaments, and its dysfunction leads to accumulated joint molecules that become toxic during chromosome segregation. Similarly, the Mus81-Mms4 complex provides an essential pathway for resolving these toxic structures, as diploid srs2Δ mus81Δ double mutants exhibit severe growth defects with concomitant accumulation of joint molecules [22].

Metabolic Pathway Toxicity

In metabolic engineering, toxic intermediates often accumulate when synthetic pathways are implemented in non-native hosts. According to dynamic optimization studies of prokaryotic metabolism, intermediates vary significantly in their toxicity, and their accumulation triggers regulatory responses that minimize flux through affected pathways [24].

Key principles governing this relationship include:

- Transcriptional regulation favors control of highly efficient enzymes with less toxic upstream intermediates

- Enzyme efficiency influences regulatory targeting, with highly efficient enzymes being preferentially regulated to minimize accumulation of downstream toxic intermediates

- Pathway architecture determines vulnerability, with linear pathways particularly susceptible to intermediate accumulation

The toxicity of metabolic intermediates is often quantified through half-inhibitory concentration (IC50), representing the concentration at which half of a bacterial population experiences growth inhibition [24].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my engineered pathway cause growth defects in production hosts? A: Growth defects frequently indicate accumulation of toxic intermediates. This occurs when downstream enzymes cannot process intermediates at the rate they are generated, especially common in heterologous pathway expression where host metabolism lacks native regulation mechanisms [25] [24].

Q2: How can I identify which intermediate in my pathway is toxic? A: Systematic approaches include: (1) expressing pathway segments progressively, (2) supplementing suspected toxic intermediates to wild-type strains, (3) monitoring metabolite accumulation via LC-MS, and (4) using transcriptomics to identify cellular stress responses [25] [24].

Q3: What genetic strategies can mitigate toxic intermediate accumulation? A: Effective approaches include: (1) balancing enzyme expression levels via promoter engineering, (2) implementing protein scaffolds for substrate channeling, (3) compartmentalization strategies, (4) adaptive laboratory evolution to select for improved tolerance, and (5) introducing bypass pathways to avoid problematic intermediates [26] [25].

Q4: How do toxic intermediates actually cause genome rearrangements? A: They primarily interfere with DNA replication and repair. Toxic recombination intermediates like joint molecules can block replication forks, leading to fork collapse and double-strand breaks. Improper repair of these breaks then results in chromosomal rearrangements, translocations, and loss of heterozygosity [22] [23].

Q5: Why are some intermediates toxic in diploid cells but not haploid cells? A: This ploidy-dependent toxicity often involves DNA repair mechanisms. In diploid cells, homologous recombination can occur between homologous chromosomes, creating toxic joint molecules that interfere with chromosome segregation. Haploid cells predominantly use sister chromatids for repair, avoiding these toxic intermediates [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Recombinant strain shows poor viability after pathway induction

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic intermediate accumulation | Metabolite profiling; suppressor mutant isolation | Adjust promoter strengths; implement metabolic valves |

| Redox/energy imbalance | ATP/NADH measurements; transcriptomics | Cofactor engineering; bypass pathways |

| Protein misfolding/aggregation | Proteostasis markers; fluorescence microscopy | Codon optimization; chaperone co-expression |

| Essential resource competition | Growth rate analysis; RNA-seq | Resource reallocation; orthogonal systems |

Problem: Increasing genomic instability during prolonged cultivation

| Observation | Potential Mechanism | Intervention Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Rising mutation frequency | DNA replication stress | Optimize pathway flux; enhance DNA repair |

| Chromosome loss/rearrangement | Toxic recombination intermediates | Modulate recombination enzymes; improve pathway regulation |

| Amplified stress responses | General protein/cellular damage | Dynamic pathway control; stress response engineering |

Problem: Pathway performance deteriorates over serial passages

| Monitoring Approach | Root Cause Analysis | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-genome sequencing | Adaptive mutations disrupting regulation | Isolate clonal variants; implement mutation-proof controls |

| Metabolite time-course | Regulatory drift or metabolite inhibition | Continuous cultivation optimization; feedback inhibition removal |

| Proteomic analysis | Enzyme degradation or inactivation | Protein engineering; stabilization tags |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Intermediate Toxicity in Engineered Pathways

Principle: This method systematically evaluates whether pathway intermediates inhibit growth when externally supplemented to host cells [24].

Materials:

- Wild-type host strain (non-pathway engineered)

- Suspected toxic intermediates (purified)

- Appropriate culture medium

- Microplate reader or spectrophotometer

- Sterile 96-well plates

Procedure:

- Prepare culture medium with varying concentrations of the suspected toxic intermediate (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 mM typically)

- Inoculate wild-type strain into each condition in triplicate

- Monitor growth kinetics via OD600 every 30-60 minutes

- Calculate specific growth rates for each condition

- Determine IC50 values by fitting growth inhibition data to appropriate models

Interpretation: Significant growth inhibition at physiologically relevant concentrations indicates potential intermediate toxicity. Compare inhibition curves to estimated intracellular concentrations in your engineered strain.

Protocol: Detecting Toxic Recombination Intermediates

Principle: This approach monitors DNA recombination intermediates in yeast using genetic and molecular tools, adapted from Keyamura et al. (2016) [22] [23].

Materials:

- Yeast strains (appropriate genotypes)

- Restriction enzymes

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

- 2D gel electrophoresis supplies

- Rad52 focus detection reagents (GFP-tagged Rad52)

Procedure:

- Strain Construction: Generate diploid strains with relevant genetic modifications (srs2 mutants, mus81Δ, etc.)

- Spontaneous Recombination Assay:

- Grow cultures to mid-log phase

- Fix cells and visualize Rad52 foci formation via fluorescence microscopy

- Quantify percentage of cells with spontaneous Rad52 foci

- Joint Molecule Detection:

- Prepare genomic DNA under non-denaturing conditions

- Perform 2D gel electrophoresis to resolve replication/recombination intermediates

- Detect specific structures using Southern blotting

- Viability Assay:

- Spot serial dilutions of relevant strains on appropriate media

- Compare growth patterns between haploid and diploid strains

Interpretation: Increased Rad52 foci, abnormal 2D gel electrophoresis patterns, and diploid-specific synthetic sickness indicate toxic recombination intermediate accumulation.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis

Toxicity Parameters of Metabolic Intermediates

Table: Experimentally determined toxicity thresholds for selected metabolic intermediates

| Intermediate | Pathway | Organism | IC50 (mM) | Primary Toxicity Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homoserine | Amino acid biosynthesis | E. coli | 2.5 | Feedback inhibition; metabolic imbalance |

| Methylglyoxal | Glycolysis bypass | Multiple | 0.8 | Protein glycation; DNA damage |

| Dihydroxyacetone phosphate | Glycolysis | E. coli | 5.2 | Redox imbalance; phosphate sequestration |

| Reactive oxygen species | Oxidative metabolism | Multiple | Varies | Protein/DNA/lipid oxidation |

| Inter-homolog joint molecules | DNA repair | S. cerevisiae | N/A | Chromosome segregation interference |

Genetic Suppressors of Toxic Intermediate Accumulation

Table: Genetic modifications that alleviate toxicity from pathway intermediates

| Toxicity Source | Suppressor Mutation/Modification | Mechanism of Suppression | Applicable Hosts |

|---|---|---|---|

| General intermediate accumulation | Promoter engineering | Balanced enzyme expression | Multiple bacteria, yeast |

| Homoserine accumulation | thrA* feedback-resistant mutant | Deregulated aspartate kinase | E. coli |

| Toxic recombination intermediates | RAD51 deletion | Reduced Rad51 filament formation | S. cerevisiae |

| Electron acceptor limitation | NADH oxidase expression | Redox balancing | E. coli, yeast |

| Membrane stress | Lipid composition engineering | Membrane integrity preservation | Multiple |

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Toxic recombination intermediates pathway. This diagram illustrates how DNA damage leads to toxic joint molecule formation when resolution pathways are compromised, ultimately causing genome instability. Key protective roles of Srs2 and Mus81-Mms4 are highlighted.

Diagram 2: Metabolic intermediate toxicity regulation. This diagram shows the relationship between enzyme efficiency, intermediate toxicity, and transcriptional regulation in metabolic pathways, illustrating why toxic intermediates accumulate when regulation targets inappropriate enzymes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential reagents for studying toxic intermediates and genome stability

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Repair Mutants | srs2Δ, mus81Δ, rad51Δ (yeast) | Studying recombination intermediate toxicity | Ploidy-specific effects critical |

| Metabolite Standards | Homoserine, methylglyoxal, DHAP | Toxicity profiling; analytical standards | Purity essential for accurate IC50 |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Rad52-GFP, DNA damage response reporters | Visualizing recombination intermediates | Quantification methods must be standardized |

| Pathway Engineering Tools | Modular promoters, CRISPRi, riboswitches | Fine-tuning enzyme expression levels | Orthogonality to host regulation important |

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS, 2D gel electrophoresis, PFGE | Detecting intermediates; genome rearrangements | Method sensitivity limits detection |

| Model Systems | S. cerevisiae, E. coli MG1655, C1 metabolism specialists | Pathway implementation; toxicity screening | Choose based on genetic tractability needs |

Strategic Design and Control: Methodologies to Prevent Toxic Buildup

Dynamic Optimization for Predicting Optimal Regulatory Programs

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

Q1: My dynamic model simulations are unstable or fail to converge. What could be the cause?

Instability in dynamic simulations often originates from incorrect model formulation, improper solver settings, or highly stiff systems.

- Check Model Formulation: Ensure mass and energy balances are correctly defined and units are consistent. Verify that all initial conditions are physically realistic.

- Adjust Solver Parameters: For stiff systems, use an implicit solver (e.g., ODE15s in MATLAB) and reduce the maximum time step size.

- Inspect Model Parameters: Review kinetic parameters and thermodynamic properties for errors or magnitudes that could lead to numerical instability.

- Simplify the Model: If the model is highly complex, try simulating sub-systems individually to isolate the problematic component.

Q2: The optimization solver returns a suboptimal solution or fails to find a feasible point. How can I improve this?

Solver failures in dynamic optimization are frequently due to poor initialization, overly restrictive constraints, or a poorly scaled problem.

- Improve Initial Guess: Provide a better initial guess for the decision variables, potentially from a previously solved, similar scenario or a simplified version of the model.

- Relax Constraints: Temporarily relax path and endpoint constraints to see if a feasible solution exists. Then, gradually tighten them to the desired values.

- Scale Variables and Equations: Ensure all variables and equations are scaled so their values are of a similar order of magnitude (e.g., between 0.1 and 10). This improves numerical conditioning.

- Verify Problem Bounds: Check that the lower and upper bounds on all variables are sensible and do not conflict.

Q3: My simulated pathway accumulates toxic intermediates, leading to failed predictions. How can I resolve this?

Toxic intermediate accumulation is a common issue in synthetic pathway optimization and indicates a bottleneck or imbalance in the system's dynamics [27].

- Identify the Bottleneck: Use sensitivity analysis (e.g., local or global Morris method) on your dynamic model to identify which kinetic parameters most significantly influence the accumulation of the toxic compound.

- Implement Dynamic Control: Reformulate the optimization problem to include a path constraint that explicitly limits the concentration of the toxic intermediate over time.

- Introduce a Bypass or Sink: Model an additional reaction or transport process that consumes or sequesters the toxic compound. Optimize the kinetics of this new pathway to prevent accumulation [27].

- Apply Multi-Objective Optimization: Frame the problem with two competing objectives: maximizing product yield and minimizing peak toxic intermediate concentration. This generates a Pareto front of optimal compromises.

Troubleshooting Methodology

When encountering problems, a systematic approach is more effective than random checks. The following methodologies can be applied [28]:

- Top-Down Approach: Start with the highest-level system overview (e.g., the overall process flow diagram) and work down to the level of the specific problem. This is best for complex, integrated systems [28].

- Divide-and-Conquer Approach: Break down the dynamic optimization problem into smaller, more manageable subproblems (e.g., state estimation, parameter identification, control optimization). Solve these recursively and combine the solutions [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Real-Time Optimization (RTO) and Dynamic Real-Time Optimization (DRTO)?

A: Conventional RTO operates on a steady-state model of the process, making it suitable for processes that spend most of their time at equilibrium. However, for systems with long transient dynamics or frequent changes, its representation is limited and can lead to suboptimal or infeasible solutions. Dynamic RTO (DRTO) directly uses a dynamic prediction model, allowing it to handle transitions between states and optimize processes that have not yet reached steady-state [29].

Q2: What are the main implementation architectures for DRTO?

A: There are two primary approaches [29]:

- Two-Layer Scheme: DRTO sits at the top, calculating optimal set-point trajectories over a long horizon. A lower-level controller (e.g., MPC) executes these trajectories at a faster sampling rate.

- Single-Layer Economic MPC (EMPC): This combines optimization and control into a single layer that uses an economic objective function directly. While more direct, it is often computationally heavy and can cause feedback delays.

Q3: What is Closed-Loop DRTO (CL-DRTO) and why is it beneficial?

A: CL-DRTO is an advanced form of DRTO that incorporates the predicted closed-loop response of the lower-level controller into its calculations. By embedding the controller's behavior (e.g., its optimality conditions), CL-DRTO can proactively adjust set-points to account for plant-model mismatch and controller limitations, leading to significantly better performance than a typical DRTO that assumes perfect control [29].

Q4: How can dynamic optimization help in elucidating biosynthetic pathways in metabolic engineering?

A: Dynamic optimization can be used to fit kinetic models to time-series metabolomics data. By optimizing model parameters to match experimental data, you can predict missing enzymatic steps, identify rate-limiting reactions, and test hypotheses about pathway regulation and toxic intermediate accumulation [27]. This is particularly powerful when biosynthesis is localized to specific, nascent plant tissues, providing a clear context for data collection and modeling [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Implementing a Two-Stage Dynamic Optimization Framework

This protocol outlines the implementation of a dynamic optimization framework suitable for bioprocess applications, based on the principles of Parameter-Dependent Differential Dynamic Programming (PDDP) [29].

1. System Identification and Dynamic Modeling

- Develop a dynamic model, typically a set of Differential-Algebraic Equations (DAEs), representing your system (e.g., a bioreactor or metabolic pathway).

- Collect experimental data to estimate unknown model parameters using a parameter estimation technique (nonlinear regression). The objective is to minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental data [30].

2. Formulate the Dynamic Optimization Problem

- Objective Function (Φ): Define what you want to optimize (e.g., maximize final product concentration, minimize accumulated toxic intermediate).

- Decision Variables (u(t)): Choose the variables you can control over time (e.g., substrate feed rate, temperature).

- Constraints: Define any path constraints (e.g., maximum allowable toxin concentration) and endpoint constraints (e.g., total batch time).

3. Apply the Optimization Algorithm

- The PDDP algorithm solves the problem iteratively [29]:

- Backward Sweep: Starting from the final time, compute the value function and a local control law that is affine in both the state and the system parameters.

- Forward Sweep: Simulate the system forward in time using the updated control law.

- This process repeats until convergence to a locally optimal trajectory.

4. Validation and Closed-Loop Implementation

- Validate the optimal trajectory by applying it to a high-fidelity model or in a real experiment.

- For robust performance, implement a closed-loop strategy where the optimization is re-run at regular intervals (e.g., CL-DRTO) to compensate for disturbances and model inaccuracies [29].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: WCAG Color Contrast Standards for Data Visualization Adhering to accessibility guidelines is critical for creating clear and readable diagrams and reports. The following standards for contrast ratios should be followed [31] [32].

| Element Type | WCAG Level AA Minimum Ratio | WCAG Level AAA Minimum Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 |

| Large Text (≥18pt or ≥14pt & bold) | 3:1 | 4.5:1 |

| Graphical Objects & UI Components | 3:1 | - |

Table 2: Example Color Contrast Analysis from a Standard Palette This table analyzes the contrast ratios between foreground and background colors from a common palette, demonstrating that many color pairs are unsuitable for text. White (#FFFFFF) or a very light gray (#F1F3F4) on a dark background (#202124) typically provides the best readability.

| Foreground Color | Background Color | Contrast Ratio | Passes AA for Normal Text? |

|---|---|---|---|

| #4285F4 (Blue) | #FFFFFF (White) | 4.5:1 | Yes |

| #EA4335 (Red) | #FFFFFF (White) | 4.8:1 | Yes |

| #FBBC05 (Yellow) | #202124 (Dark Gray) | 13.4:1 | Yes |

| #34A853 (Green) | #FFFFFF (White) | 3.7:1 | No |

| #4285F4 (Blue) | #F1F3F4 (Light Gray) | 3.1:1 | No |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Alkaloid Biosynthesis This table lists key materials used in the study of complex plant pathways, such as the Amaryllidaceae alkaloids, which is a relevant case study for toxic intermediate management [27].

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| 4'-O-Methylnorbelladine (4OMN) | The central precursor and committed intermediate for the biosynthesis of all major classes of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (e.g., galantamine, lycorine) [27]. |

| Heterologous Hosts (S. cerevisiae, E. coli) | Scalable microbial systems used for the sustainable production of plant natural products and for testing the functionality of putative biosynthetic enzymes [27]. |

| Cytochrome P450 Enzymes (e.g., CYP96T1) | Key enzymes that catalyze the regioselective phenolic coupling of 4OMN, determining the scaffold type (e.g., para-para') and thus the downstream alkaloid class [27]. |

| L-Phenylalanine & L-Tyrosine | The primary amino acid precursors from which the norbelladine scaffold is derived via reductive condensation [27]. |

Pathway & Workflow Diagrams

Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Biosynthetic Pathway

Diagram 1: Diversity-oriented biosynthesis of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids from a common precursor. The gatekeeping oxidative coupling step, catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes, determines the structural class and potential for toxic intermediate accumulation [27].

Closed-Loop Dynamic RTO Workflow

Diagram 2: Two-layer closed-loop dynamic real-time optimization (CL-DRTO) architecture. The upper DRTO layer uses a dynamic model and knowledge of the lower-level controller to compute optimal set-points, which are then executed by the fast controller [29].

Host Organism Selection and Pathway Architecture Design for Innate Detoxification

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Topic 1: Host Organism Viability

Q: My engineered E. coli culture shows significantly reduced growth rates or cell lysis after induction of the synthetic pathway. What is the most likely cause?

- A: This is a classic symptom of toxic intermediate accumulation. The heterologous pathway is likely producing a compound that the host's native metabolism cannot process efficiently, leading to inhibition of essential cellular processes. Troubleshooting steps include:

- Analyze Intermediate Toxicity: Use in silico tools (e.g., ToxTree) to predict the toxicity of pathway intermediates.

- Profile Metabolites: Perform LC-MS/MS on culture supernatants and cell lysates to identify and quantify the accumulating toxic intermediate.

- Host Switching: Consider a host with innate resistance, such as Pseudomonas putida for aromatic compounds or Rhodosporidium toruloides for lipid-like toxins.

- Pathway Compartmentalization: Re-engineer the pathway to be expressed in a cellular compartment (e.g., peroxisome in yeast) that can sequester the toxin.

- A: This is a classic symptom of toxic intermediate accumulation. The heterologous pathway is likely producing a compound that the host's native metabolism cannot process efficiently, leading to inhibition of essential cellular processes. Troubleshooting steps include:

Q: Why does my chosen yeast host (S. cerevisiae) perform well in small-scale cultures but fail in the bioreactor?

- A: Scale-up issues often exacerbate toxicity. In bioreactors, higher cell densities and metabolite concentrations can lead to a critical threshold of toxic intermediate being reached. Solutions include:

- Dynamic Pathway Control: Implement a metabolite-responsive promoter to delay expression of the toxin-producing enzyme until the culture reaches a robust density.

- In Situ Product Removal (ISPR): Integrate a resin or solvent extraction system in the bioreactor to continuously remove the toxic product or intermediate from the cultivation broth.

- A: Scale-up issues often exacerbate toxicity. In bioreactors, higher cell densities and metabolite concentrations can lead to a critical threshold of toxic intermediate being reached. Solutions include:

Topic 2: Enzyme & Pathway Optimization

Q: I have confirmed toxic intermediate accumulation via HPLC. How can I resolve this without switching hosts?

- A: Pathway architecture redesign is your primary tool.

- Enzyme Engineering: Use directed evolution or rational design to alter the substrate specificity or catalytic efficiency of the upstream enzyme to reduce the flux into the bottleneck.

- Co-localization: Create synthetic enzyme scaffolds (e.g., using protein-protein interaction domains) to bring consecutive enzymes in close proximity, facilitating channeling and minimizing intermediate diffusion.

- Add a Detoxification Module: Introduce a heterologous enzyme (e.g., a transferase, oxidase, or transporter) that converts the toxic intermediate into a benign molecule or exports it from the cell.

- A: Pathway architecture redesign is your primary tool.

Q: My pathway uses enzymes from multiple different source organisms, and overall titers are low. Could enzyme incompatibility be the issue?

- A: Yes. Differences in co-factor preference (NADH vs. NADPH), pH optimum, or subcellular localization between heterologous enzymes can create inefficiencies that lead to intermediate pooling.

- Cofactor Balancing: Introduce transhydrogenases or use enzyme engineering to swap cofactor specificity to create a balanced system.

- Promoter Tuning: Use a library of promoters with varying strengths to optimize the expression ratio of each enzyme, rather than relying on a single strong promoter for all genes.

- A: Yes. Differences in co-factor preference (NADH vs. NADPH), pH optimum, or subcellular localization between heterologous enzymes can create inefficiencies that lead to intermediate pooling.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metabolite Profiling for Toxic Intermediate Identification

Objective: To identify and quantify intermediates accumulating in an engineered microbial host.

Materials:

- Centrifuge and microcentrifuge tubes

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system

- Solvents: Methanol, Acetonitrile (LC-MS grade)

- Internal standards (e.g., stable isotope-labeled analogs of expected intermediates)

- Quenching solution (60% methanol, -40°C)

Methodology:

- Culture Sampling: Withdraw culture aliquots at multiple time points (e.g., pre-induction, 2h, 4h, 8h post-induction).

- Rapid Metabolite Quenching: Immediately mix 1 mL of culture with 4 mL of pre-cooled quenching solution (-40°C). Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 13,000 x g, 5 min, -9°C).

- Metabolite Extraction: Discard supernatant. Resuspend cell pellet in 1 mL of extraction solvent (40:40:20 Acetonitrile:Methanol:Water). Vortex vigorously for 1 minute.

- Clearance: Centrifuge at 13,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Transfer the supernatant to a new vial.

- Analysis: Inject the extracted sample into the LC-MS/MS system. Use multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for targeted analysis of predicted intermediates or full-scan for untargeted discovery.

Protocol 2: Testing Detoxification Enzyme Efficacy

Objective: To evaluate the ability of a candidate detoxification enzyme to restore growth in the presence of a toxic intermediate.

Materials:

- Two plasmid systems: one for the candidate detoxification gene, one as an empty vector control.

- Solid and liquid growth media with and without the purified toxic intermediate.

- Microplate reader for growth curve analysis.

Methodology:

- Strain Transformation: Transform your production host with either the detoxification plasmid (Test) or the empty vector control (Control).

- Growth Curve Assay: Inoculate 200 µL of media in a 96-well plate with each strain. Use two media conditions: with and without a sub-lethal concentration of the toxic intermediate.

- Monitoring: Place the plate in a microplate reader and incubate with continuous shaking. Measure optical density (OD600) every 15-30 minutes for 24-48 hours.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the maximum growth rate (µmax) and final biomass yield (OD600 max) for each condition. A significant improvement in the Test strain compared to the Control in the presence of the toxin confirms enzyme efficacy.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Host Organisms for Innate Toxin Resistance

| Host Organism | Innate Strengths / Resistances | Common Toxins Handled Poorly | Preferred Pathway Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Fast growth, high yields, extensive toolkit | Hydrophobic compounds, reactive electrophiles, membrane disruptors | Balanced, moderate expression; Exporters; Fusion proteins |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Eukaryotic PTMs, compartmentalization, robust | Short-chain alcohols, organic acids, Farnesyl pyrophosphate | Peroxisomal targeting; Cofactor balancing; ATP-driven exporters |

| Pseudomonas putida | Solvent tolerance, oxidative stress resistance, diverse metabolism | N/A (Generalist with high innate tolerance) | High-flux, linear pathways; Leverage native robust metabolism |

| Bacillus subtilis | Protein secretion, GRAS status, sporulation | N/A (Good general stress resistance) | Secretion-directed pathways; Inducible systems |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Detoxification Strategies on Model Pathway Titer

| Strategy | Final Titer (mg/L) | Max Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Toxic Intermediate Conc. (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Unoptimized) | 150 ± 22 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 450 ± 60 |

| Promoter Tuning | 380 ± 45 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 210 ± 30 |

| Enzyme Scaffolding | 510 ± 62 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 95 ± 15 |

| + Heterologous Transporter | 890 ± 105 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 35 ± 8 |

Visualizations

Troubleshooting Logic for Toxicity

Toxic Intermediate Pathway Bottleneck

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | For targeted identification and precise quantification of pathway intermediates and products in complex biological samples. |

| CRiSPRi/dCas9 Toolkits | Enables fine-tuning of gene expression without altering the DNA sequence, ideal for dynamic pathway control and balancing. |

| Protein Scaffolding Systems | Synthetic complexes (e.g., based on SH3/PDZ domains) to co-localize sequential enzymes, minimizing intermediate diffusion. |

| Cytometric Bead Assays | High-throughput method to measure relative levels of specific metabolites or co-factors (e.g., NADPH/NADP+) in single cells. |

| In Silico Toxicity Predictors (e.g., ToxTree) | Software to predict the chemical toxicity of proposed pathway intermediates, guiding pre-emptive pathway design. |

Implementing Transcriptional Control of Highly Efficient Enzymes

Accumulating toxic intermediates is a significant challenge in engineered metabolic pathways, often leading to reduced product yields and host cell toxicity. A powerful strategy to overcome this is the transcriptional control of highly efficient enzymes. This approach is grounded in the optimality principle that transcriptional regulation preferentially targets highly efficient enzymes to minimize the accumulation of toxic downstream metabolites [33]. This technical support center provides a foundational guide to the key concepts, troubleshooting, and experimental protocols for implementing this strategy in your research.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Why should I focus transcriptional control on highly efficient enzymes rather than known rate-limiting steps?

Traditional views often target rate-limiting, inefficient enzymes. However, dynamic optimization models reveal that regulating highly efficient enzymes upstream of a toxic intermediate allows for a more rapid flux adjustment, preventing the accumulation of toxic compounds while minimizing the overall protein production cost for the cell [33].

Q2: What are the common experimental outcomes when transcriptional control fails to prevent toxicity?

Failed experiments often manifest in several observable ways. The table below summarizes these outcomes and their potential causes.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Toxicity from Failed Transcriptional Control

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low product yield, slow cell growth | Accumulation of toxic intermediates inhibits cell metabolism and diverts flux [33] [34]. | Re-engineer the promoter regulating the upstream, highly efficient enzyme to allow for stronger or more responsive induction. |

| High metabolic burden, slow response | The transcriptional program is not optimally tuned, leading to excessive protein expression or slow adaptation to demand changes [33]. | Fine-tune promoter strength and use dynamic regulation systems to express enzymes only when needed. |

| Inconsistent performance across conditions | Fixed-level transcriptional control is insufficient for pathways with multiple toxic intermediates or complex regulation [33]. | Implement a multi-layered control strategy that includes synthetic scaffolds to organize enzymes [34] or incorporate post-translational regulation. |

Q3: How can I identify which highly efficient enzymes to target for transcriptional control in my pathway?

The efficiency of an enzyme is determined by its kinetic parameters. The following protocol outlines a methodology for a systematic evaluation.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Enzyme Efficiency for Transcriptional Control

Objective: To identify highly efficient enzymes in a metabolic pathway based on their kinetic parameters for targeted transcriptional regulation.

Materials:

- Purified Enzymes: Each enzyme in the pathway of interest, expressed and purified.

- Substrates: Relevant substrates for each enzymatic reaction.

- Spectrophotometer or LC-MS: For quantifying reaction rates.

Method:

- Determine Kinetic Parameters: For each enzyme, measure the reaction velocity (V) at varying substrate concentrations [S].

- Calculate kcat and Km: Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (V = (kcat * [E] * [S]) / (Km + [S])) to obtain:

- kcat (turnover number): The maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. A higher kcat indicates a more efficient enzyme.

- Km (Michaelis constant): The substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax. A lower Km indicates a higher substrate affinity.

- Calculate Catalytic Efficiency: Compute the ratio kcat/Km. This second-order rate constant represents the enzyme's overall efficiency.

- Prioritize Targets: Rank the enzymes in your pathway based on their kcat/Km values. For resolving toxic intermediate accumulation, prioritize the transcriptional control of enzymes with high catalytic efficiency that are located upstream of a known toxic metabolite [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential tools and reagents for experiments involving the transcriptional control of enzymes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Promoters | DNA sequences that allow precise control over the timing and level of gene expression in response to a chemical or physical signal. | Tightly regulating the expression of a highly efficient enzyme to dynamically adjust metabolic flux [33]. |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Engineered proteins, such as TAL effectors or CRISPR-based regulators, designed to bind specific DNA sequences and control transcription [35]. | Creating orthogonal regulatory circuits to control pathway enzymes without interfering with native host regulation. |

| Synthetic Scaffolds | Engineered proteins, RNA, or DNA structures that co-localize multiple enzymes in a pathway to facilitate substrate channeling [34]. | Preventing the diffusion of toxic intermediates by channeling them directly between enzyme active sites, often used in conjunction with transcriptional control. |

| Plasmid Libraries with Varying Promoter Strength | A collection of expression vectors where the same gene is under the control of promoters with different, characterized transcriptional strengths. | Systematically tuning the expression level of a target enzyme to find the optimal balance between flux and toxicity [33]. |

Visualizing the Core Regulatory Strategy

The following diagram illustrates the core logic for selecting enzyme targets for transcriptional control to mitigate intermediate toxicity.

Pathway Engineering Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps for designing and testing a metabolically engineered pathway with optimized transcriptional control.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the primary cause of toxic intermediate accumulation in engineered metabolic pathways, and how can it be detected?

Toxic intermediate accumulation often occurs when a downstream enzymatic step in a biosynthetic pathway becomes a bottleneck or is completely blocked. This is particularly problematic with pathway intermediates that have detergent-like properties, which can disrupt cellular membranes and inhibit growth [36] [37]. A case study in Acinetobacter baumannii demonstrated that blocking the LpxH enzyme in the lipid A biosynthesis pathway led to the accumulation of UDP-2,3-diacyl-GlcN. This accumulation caused visible damage to the cell's inner membrane and impaired growth, even in a strain where the final pathway product (LPS) was non-essential [36] [37].

Detection Methodologies:

- Mass Spectrometry: Directly measure the cellular levels of pathway intermediates. In the LpxH study, this technique confirmed the significant buildup of UDP-2,3-diacyl-GlcN and other intermediates upon enzyme depletion [36].

- Electron Microscopy: Visualize ultrastructural damage to cellular membranes resulting from intermediate toxicity [36] [37].

- Viable Cell Counts: Monitor culture viability. A drop in viable counts correlates with intermediate accumulation and growth impairment [37].

Q2: During metabolic model gapfilling, why does my model fail to grow even after adding reactions, and how can I resolve this?

Gapfilling failure can stem from several issues. The process is designed to find a minimal set of reactions enabling growth on a specified medium [38]. Failure may indicate that the algorithm is trapped in a non-optimal solution or that essential pathways remain incomplete.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Verify Media Composition: Ensure the defined growth medium in your simulation matches the experimental conditions. An incorrect or incomplete medium definition is a common cause of failure.

- Inspect the Gapfilling Solution: Examine the reactions added by the algorithm. The output table can be sorted by the "Gapfilling" column. Newly added reactions are typically irreversible (=> or <=), while existing reactions made reversible are indicated by "<=>" [38].