Resolving Cofactor Imbalance in Engineered Metabolic Pathways: Strategies for Enhanced Bioproduction

Cofactor imbalance is a critical bottleneck that obstructs productivity in metabolically engineered cells for chemical and drug manufacturing.

Resolving Cofactor Imbalance in Engineered Metabolic Pathways: Strategies for Enhanced Bioproduction

Abstract

Cofactor imbalance is a critical bottleneck that obstructs productivity in metabolically engineered cells for chemical and drug manufacturing. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of cofactor demands in synthetic pathways. It details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including in situ cofactor enhancing systems, protein engineering, and computational modeling for rebalancing NAD(P)H, ATP, and other cofactors. The content further covers advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques to overcome flux limitations, alongside rigorous validation frameworks for comparative pathway assessment. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as an essential guide for designing efficient microbial cell factories with optimized cofactor metabolism to improve yields in biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding Cofactor Imbalance: The Fundamental Challenge in Metabolic Engineering

Defining Cofactor Imbalance and Its Impact on Pathway Productivity

Cofactor imbalance is a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering that occurs when the demand for a specific cofactor form (e.g., reduced or oxidized) in an engineered pathway exceeds the cell's capacity to regenerate it, leading to suboptimal production of target compounds. Cofactors are non-protein compounds essential for the catalytic function of numerous enzymes, with NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ pairs being among the most highly connected metabolites in cellular metabolic networks [1]. These cofactors serve as redox carriers for biosynthetic and catabolic reactions and act as important agents in energy transfer for the cell [2]. In engineered pathways, imbalances disrupt redox homeostasis, causing widespread metabolic changes that ultimately limit pathway productivity and strain stability [1] [3] [4].

The significance of cofactor engineering has grown with the increased use of engineered organisms to produce valuable chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels from renewable resources [5]. By manipulating cofactor concentrations and specificity, metabolic engineers can maximize metabolic fluxes toward desired products, reduce operation costs by substituting expensive cofactors with more stable alternatives, and overcome natural thermodynamic constraints [5] [2]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for identifying, troubleshooting, and resolving cofactor imbalance issues in engineered metabolic pathways.

FAQ: Understanding Cofactor Imbalance

Q1: What are the primary manifestations of cofactor imbalance in engineered strains?

Cofactor imbalance typically presents through several observable phenomena:

- Accumulation of pathway intermediates: Reduced pathway flux due to cofactor limitations often leads to buildup of intermediate metabolites [3]. For example, in engineered S. cerevisiae strains containing fungal pentose utilization pathways, xylitol accumulation occurs due to differing cofactor specificities of xylose reductase (preferring NADPH) and xylitol dehydrogenase (preferring NAD+) [3].

- Reduced target product yields: The ultimate manifestation is lower than theoretically possible production of the target compound, as seen in cyanobacterial production systems where the naturally abundant NADPH pool creates limitations for NADH-dependent enzymes commonly sourced from heterotrophic microbes [6].

- Growth impairments and reductive stress: Excess NADH can inhibit critical metabolic enzymes, impair cofactor regeneration, and cause reductive stress, potentially triggering strain degradation over multiple fermentation batches [4].

Q2: How does cofactor imbalance specifically reduce pathway efficiency?

Cofactor imbalance impacts pathway efficiency through multiple mechanisms:

- Thermodynamic constraints: When the ratio of reduced to oxidized cofactors becomes unfavorable, the thermodynamic driving force for cofactor-dependent reactions decreases, potentially making some reactions non-spontaneous [7].

- Enzyme inhibition: Many dehydrogenases are sensitive to NADH/NAD+ ratios, and imbalance can lead to product inhibition or suppressed enzymatic activity [1].

- Precursor diversion: Redox imbalances can alter the availability of key precursors from central carbon metabolism, such as α-keto acids and acetyl-CoA, which serve as precursors for many volatile compounds and other metabolites [1].

- Energy metabolism disruption: In anaerobic conditions, NADH is oxidized by specific dehydrogenases, and ATP production occurs mainly through substrate-level phosphorylation. Cofactor imbalance disrupts this energy generation [8].

Q3: What are the key differences between NADH and NADPH in metabolic engineering?

Although NADH and NADPH are structurally similar, they play distinct metabolic roles and have different stability and cost considerations:

Table 1: Key Differences Between NADH and NADPH

| Characteristic | NADH | NADPH |

|---|---|---|

| Primary metabolic role | Catabolic processes, energy generation | Anabolic processes, biosynthesis |

| Cellular compartmentalization | Mitochondria and cytosol | Predominantly cytosol |

| Stability | More stable | Less stable due to phosphate group |

| Production cost | Less expensive | More expensive to synthesize |

| Standard reduction potential (E₀') | -0.32 V | -0.32 V |

| Major generation pathways | Glycolysis, TCA cycle, fatty acid oxidation | Pentose phosphate pathway, NADP-dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase |

The phosphate group makes NADPH less stable than NADH, and therefore more expensive to synthesize, creating economic incentives for substituting NADPH-dependent enzymes with NADH-dependent alternatives where possible [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Cofactor Imbalance

Step 1: Diagnostic Symptoms and Detection Methods

Table 2: Diagnostic Approaches for Cofactor Imbalance

| Symptom | Detection Method | Potential Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced product yield with intermediate accumulation | HPLC/Gas Chromatography, Mass Spectrometry | Cofactor limitation at specific pathway steps |

| Decreased growth rate or cell viability | Cell counting, dry weight measurements | Reductive stress or energy deficit |

| Altered byproduct profile | Metabolic flux analysis | Compensatory pathway activation |

| Declining production across fermentations | Time-series metabolite profiling | Cumulative redox stress and strain instability |

| Inefficient co-substrate utilization | Cofactor concentration assays (NAD+/NADH, NADP+/NADPH ratios) | Direct cofactor imbalance evidence |

Step 2: Quantitative Analysis of Cofactor States

Monitoring intracellular cofactor concentrations and ratios provides direct evidence of imbalance. Key metrics include:

- NAD+/NADH ratio: Typically ranges from 3-10 in healthy cells under normal conditions; lower values indicate reductive stress [1].

- NADP+/NADPH ratio: Generally maintained at lower values (approximately 0.005-0.1) to favor reductive biosynthesis [1].

- ATP/ADP ratio: Reflects cellular energy status; imbalances in redox cofactors often affect energy metabolism.

Analytical techniques for quantification include:

- Enzymatic assays: Using specific dehydrogenases coupled to chromogenic or fluorogenic reporters.

- HPLC-based methods: Separating and quantifying oxidized and reduced forms.

- Mass spectrometry: Providing comprehensive coverage of cofactor pools and related metabolites.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cofactor Engineering Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactor-Regenerating Enzymes | NADH oxidase (Nox), Formate dehydrogenase (Fdh) | Oxidize or reduce cofactors to maintain balance |

| Engineered Enzymes | Cofactor-specificity mutated Gre2p, PdxA variants | Altered cofactor preference (NADPH to NADH or vice versa) |

| Pathway Enzymes | NADP-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB), CoA-acylating butyraldehyde dehydrogenase (Bldh) | Replace native enzymes to match host cofactor availability |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, Expression plasmids (pRSFDuet-1), Site-directed mutagenesis kits | Enable genome editing and pathway engineering |

| Analytical Standards | NAD+, NADH, NADP+, NADPH, ATP, ADP | Quantification of cofactor pools and ratios |

| Specialized Growth Media | Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, Synthetic grape must (SM250), Defined fermentation media | Controlled culture conditions for reproducible experiments |

Experimental Protocols for Cofactor Balancing

Protocol 1: Switching Cofactor Specificity through Protein Engineering

Background: This protocol describes the process of changing an enzyme's cofactor preference from NADPH to NADH, which can significantly reduce production costs due to NADPH's higher cost and lower stability [5].

Materials:

- Target enzyme with known structure (e.g., Gre2p)

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

- Expression vector and host strain (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae)

- Analytics: HPLC, GC-MS, or enzyme activity assays

Procedure:

- Identify critical residues: Determine amino acids in the active site that interact with the 2'-phosphate group of NADPH through structural analysis. For Gre2p, Asn9 was identified as critical for NADPH binding [5].

- Design mutations: Substitute identified residues with amino acids that favor NADH binding. For Gre2p, replacing Asn9 with Glu (glutamic acid) produced stronger effects than Asp (aspartic acid) due to the extra carbon in its side chain [5].

- Implement mutagenesis: Use site-directed mutagenesis to create variant enzymes.

- Express and purify: Produce mutant enzymes in suitable expression systems.

- Characterize kinetics: Determine KM, kCAT, and enzyme activity with both NADPH and NADH. Successful engineering of Gre2p doubled the maximum reaction velocity when using NADH [5].

- Test in pathway context: Incorporate the engineered enzyme into the full pathway and assess impact on product yield and cofactor balance.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Cofactor Regeneration System

Background: This protocol establishes a minimal enzymatic pathway for controlling the redox state of NADH and NADPH in engineered systems, using formate as a driving force [7].

Materials:

- Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) from Starkeya novella

- Soluble transhydrogenase (SthA)

- Phospholipids for vesicle formation (if using compartmentalized systems)

- NAD+, NADP+

- Sodium formate

Procedure:

- Enzyme preparation: Express and purify FDH and transhydrogenase enzymes.

- System assembly:

- For cell-free systems: Combine enzymes with cofactors in appropriate buffer.

- For vesicle systems: Encapsulate enzymes and cofactors in liposomes.

- Initiate regeneration: Add formate to drive the system.

- Monitor cofactor conversion: Track NADH formation by fluorescence (excitation 340 nm, emission 460 nm).

- Validate functionality: Couple the regeneration system to a target pathway enzyme (e.g., glutathione reductase) to confirm efficient cofactor recycling.

Key parameters:

- FDH KM for formate: 2.15 mM [7]

- Optimal formate concentration: >5 mM

- System stability: Remains active for up to 7 days in vesicle systems [7]

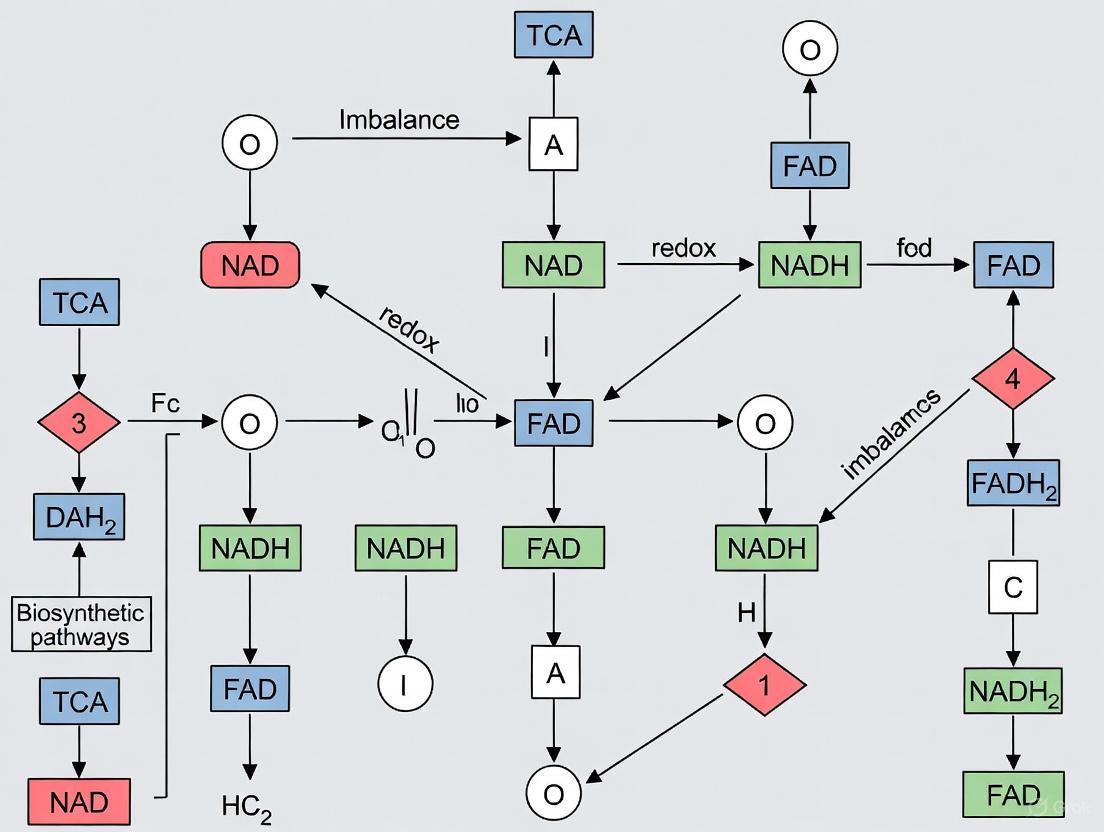

Pathway Diagrams and Engineering Workflows

Cofactor Balancing Engineering Workflow

NADPH vs NADH Pathway Balancing Strategy

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Case Study 1: Enhancing Pyridoxine Production in E. coli

Problem: Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) biosynthesis generates three NADH molecules per molecule of product, creating significant redox imbalance that limits production efficiency [4].

Engineering strategies implemented:

- Enzyme engineering: Designed NAD+-dependent enzymes to reduce cofactor demand.

- NAD+ regeneration: Introduced heterologous NADH oxidase (Nox) from Streptococcus pyogenes to oxidize NADH back to NAD+.

- NADH production reduction: Modified glycolytic pathway to reduce NADH generation while maintaining carbon flux.

Results: The engineered E. coli strain achieved a pyridoxine titer of 676 mg/L in shake flasks within 48 hours, demonstrating the effectiveness of multiple coordinated cofactor engineering strategies [4].

Case Study 2: Overcoming NADPH/NADH Imbalance in Cyanobacteria

Problem: Cyanobacteria possess an naturally abundant NADPH pool but limited NADH supply, creating challenges when expressing NADH-dependent enzymes from heterotrophic microbes [6].

Solutions applied:

- Enzyme substitution: Replaced NADH-dependent enzymes in the 1-butanol production pathway with NADPH-dependent alternatives:

- Replaced hydroxybutyric dehydrogenase (Hbd) with acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB)

- Substituted aldehyde dehydrogenase activity of AdhE2 with CoA-acylating butyraldehyde dehydrogenase (Bldh)

- Cofactor specificity engineering: Changed the cofactor preference of key enzymes from NADH to NADPH through protein engineering.

Outcome: Successfully created a functional 1-butanol production pathway in S. elongatus by matching enzyme cofactor requirements to host cofactor availability [5] [6].

FAQ: Implementation Challenges

Q4: What are the key considerations when choosing between protein engineering and pathway substitution for cofactor balancing?

The decision depends on multiple factors:

- Enzyme knowledge: Well-characterized enzymes with known structural information are better candidates for protein engineering approaches.

- Alternative availability: When natural enzymes with different cofactor specificities exist, pathway substitution is often more straightforward.

- Regulatory constraints: For pharmaceutical production, regulatory considerations may favor using natural enzyme sequences over engineered ones.

- Time and resources: Protein engineering requires significant investment in screening and characterization, while pathway substitution can sometimes be implemented more rapidly.

Q5: How can I determine whether cofactor imbalance is limiting my pathway productivity?

Diagnostic approaches include:

- Stoichiometric analysis: Calculate the theoretical cofactor demand of your pathway and compare it to the host's regeneration capacity.

- Cofactor profiling: Measure intracellular concentrations of NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADP+ during production phase.

- Isotopic tracing: Use 13C metabolic flux analysis to identify bottlenecks and alternative pathway usage.

- Enzyme activity assays: Measure in vitro enzyme activities with different cofactors to identify potential limitations.

- Computational modeling: Use genome-scale metabolic models to predict flux distributions and identify cofactor-related limitations [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Cofactor Imbalances

Cofactor imbalance is a major obstacle in metabolic engineering, often leading to reduced cell growth, accumulation of by-products, and low yields of the target compound. The table below outlines common symptoms, their likely causes, and potential solutions.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Proposed Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product yield despite high pathway expression | Insufficient reducing power (NADPH) for biosynthesis. | Engineer the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) by overexpressing 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (gndA) or glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (gsdA). [9] | [8] [9] |

| Accumulation of metabolic intermediates or by-products (e.g., acetate) | Imbalance in energy cofactors (ATP/ADP) or acetyl-CoA. | Modulate the acetate pathway to regulate acetyl-CoA levels. [8] Implement a sugar phosphate boosting system (e.g., XR/lactose) to enhance ATP and acetyl-CoA biosynthesis. [10] | [10] [8] |

| Poor enzyme activity in vitro due to costly cofactor requirement | The process is stoichiometrically limited by expensive cofactors like NADPH. | Incorporate an enzymatic cofactor regeneration system, such as a mutant phosphite dehydrogenase (RsPtxDHARRA) for NADPH regeneration. [11] | [11] [12] |

| Suboptimal thermodynamic driving force | Native enzyme cofactor specificity (NADH/NADPH) is misaligned with network thermodynamics. | Swap enzyme cofactor specificity from NADPH to the more affordable and stable NADH, or vice-versa, to match in vivo cofactor ratios. [5] [13] | [5] [13] |

| Inconsistent product formation in light-dependent systems (e.g., FAP) | Limited supply of FAD cofactor. | Employ a generic cofactor booster like the XR/lactose system to increase precursor pools for FAD biosynthesis. [10] | [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most efficient strategies for regenerating NADPH in a bacterial cell factory?

There are several effective strategies, each with advantages:

- Strengthening the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP): Overexpression of key PPP enzymes, particularly 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (gndA), has been shown to significantly increase the intracellular NADPH pool and enhance product yields like glucoamylase. [9]

- Employing Synthetic Cofactor Regeneration Systems: Enzymes like engineered, thermostable phosphite dehydrogenases (e.g., RsPtxDHARRA) can be coupled with your main reaction. This system uses inexpensive phosphite to continuously regenerate NADPH from NADP+, greatly improving process economics. [11]

- Implementing a Sugar Phosphate Boosting System: Expression of a xylose reductase (XR) with lactose induction can rewire central metabolism to increase sugar phosphate pools, which are precursors for NADPH biosynthesis. This is a "minimally perturbing" generic tool that allows the cell to customise cofactor generation based on demand. [10]

FAQ 2: How can I thermodynamically favor my desired biosynthetic pathway?

The thermodynamic driving force of a network is shaped by the cofactor specificity of its reactions. [13] Computational analyses indicate that the native NAD(P)H specificities in E. coli are already optimized for maximal thermodynamic driving force. [13] Therefore, for a heterologous pathway, you should:

- Analyze Cofactor Ratios: Determine the in vivo ratio of NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ in your host under production conditions.

- Match Cofactor Use: Select or engineer pathway enzymes to use the cofactor (NADH or NADPH) that has the most favorable in vivo concentration ratio for their specific reaction direction, thereby maximizing the negative ΔG of each step. [13]

FAQ 3: Can I change an enzyme's cofactor preference from NADPH to NADH to reduce costs?

Yes, this is a established application of cofactor engineering. NADPH is more expensive and less stable than NADH. [5] Through site-directed mutagenesis, you can alter the amino acids in the enzyme's cofactor-binding pocket. For example, mutating a key asparagine to aspartic acid or glutamic acid in the dehydrogenase Gre2p decreased its dependency on NADPH and increased its affinity for NADH, reducing operational costs for chiral synthesis. [5]

FAQ 4: What is a generic method to boost multiple cofactors (e.g., NADPH, FAD, ATP) simultaneously without extensive pathway engineering?

The XR/lactose system is designed for this purpose. By expressing xylose reductase (XR) and using lactose as an inducer/carbon source, you can increase the cellular pool of sugar phosphates. These sugar phosphates are connected to the biosynthesis pathways of multiple essential cofactors. This single genetic modification has been shown to enhance productivities in systems with different cofactor demands (fatty alcohols, bioluminescence, alkanes) by 2-4 fold. [10]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the XR/Lactose Cofactor Boosting System

This protocol details how to construct and test the versatile XR/lactose system in E. coli to enhance multiple cofactors for improved bioproduction. [10]

1. Principle The system utilizes xylose reductase (XR) to reduce the hexose sugars (glucose and galactose) derived from lactose hydrolysis. The resulting hexitols are metabolized, leading to an accumulation of sugar phosphates that serve as precursors for NAD(P)H, FAD, FMN, and ATP biosynthesis. [10]

2. Materials

- Strains: E. coli BL21(DE3) chassis, engineered with your pathway of interest (e.g., FAR for fatty alcohols, LuxCDEAB for bioluminescence, or FAP for alkanes).

- Plasmids: Expression vector containing the XR gene from Hypocrea jecorina.

- Culture Media: LB or defined medium with lactose as the sole carbon source and inducer (typical concentration 2-20 g/L). [10]

- Equipment: Standard bioreactor or shake flasks, GC-MS/HPLC for product analysis.

3. Procedure 1. Strain Construction: Transform the XR expression plasmid into your engineered E. coli production strain to create the test strain (e.g., E. coli-far-xr). The parent strain without the XR plasmid serves as the control. 2. Culture Induction: Inoculate main cultures and induce protein expression with lactose. The study used a 6-hour induction period. [10] 3. Bioconversion Assay: Harvest cells after induction. Use these cells as biocatalysts in a production assay, again supplying lactose as a substrate. 4. Analysis: Quantify the final product titer (e.g., fatty alcohols via GC-MS) and compare the productivity (μmol/L/h) between the control and the XR-equipped strain. Metabolomic analysis can confirm increased sugar phosphate levels. [10]

4. Expected Results The XR/lactose system typically increases productivity by 2 to 4-fold compared to the control system. For example, in a fatty alcohol production system, the productivity increased from 58.1 μmol/L/h (control) to 165.3 μmol/L/h with XR. [10]

Diagram 1: The XR/Lactose Cofactor Boosting System Workflow.

Protocol 2: Engineering an NADPH Regeneration System using Phosphite Dehydrogenase

This protocol describes using an engineered phosphite dehydrogenase (RsPtxD) for in situ regeneration of NADPH in a coupled enzyme reaction. [11]

1. Principle The mutant RsPtxDHARRA oxidizes inexpensive phosphite to phosphate, concurrently reducing NADP+ to NADPH. This reaction has a large negative ΔG, providing a strong thermodynamic driving force and allowing a single molecule of NADPH to be reused many times. [11]

2. Materials

- Enzymes: Purified mutant RsPtxDHARRA and your NADPH-dependent target enzyme (e.g., Shikimate dehydrogenase from T. thermophilus). [11]

- Reagents: NADP+, Sodium phosphite, Substrate for your target enzyme (e.g., 3-dehydroshikimate).

- Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl. [11]

- Equipment: Thermostated reactor (e.g., water bath at 45°C), Spectrophotometer.

3. Procedure 1. Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing: * Buffer * NADP+ (catalytic amount) * Sodium phosphite (10-50 mM, sacrificial substrate) * Your target substrate (e.g., 20 mM 3-dehydroshikimate) 2. Enzyme Addition: Start the reaction by adding both the target enzyme (e.g., shikimate dehydrogenase) and the RsPtxDHARRA mutant. 3. Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 45°C with mixing for several hours. [11] 4. Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by tracking the consumption of your substrate or the formation of your product (e.g., shikimic acid) using HPLC. Alternatively, follow the stable concentration of NADPH spectrophotometrically at 340 nm.

4. Expected Results The coupled system should achieve a high total turnover number (TTN, moles of product per mole of NADP+) for the cofactor. The RsPtxDHARRA mutant enables efficient conversion at 45°C, a temperature at which the parent enzyme could not support the reaction, demonstrating its utility for thermostable processes. [11]

Diagram 2: NADPH Regeneration via Phosphite Dehydrogenase.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and tools used in the experiments cited in this guide.

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Key Details / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Xylose Reductase (XR) | A sugar reductase used in a cofactor boosting system to increase sugar phosphate and cofactor pools. [10] | From Hypocrea jecorina; reduces glucose and galactose to their corresponding hexitols using NADPH. [10] |

| Engineered Phosphite Dehydrogenase (RsPtxDHARRA) | A highly active and thermostable enzyme for efficient NADPH regeneration from NADP+ and phosphite. [11] | Mutant with 44.1 μM⁻¹ min⁻¹ catalytic efficiency for NADP; stable at 45°C for 6 hours. [11] |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | An alternative enzyme for NAD(P)H regeneration, using glucose as a sacrificial substrate. [10] [11] | Produces gluconic acid, which may lower pH and inhibit some reactions. [11] |

| Tet-on Gene Switch | A tunable genetic system for precise control of gene expression in host organisms like A. niger. [9] | Induced by doxycycline (DOX); allows tight, metabolism-independent control of overexpression genes (e.g., gndA, maeA). [9] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A genetic tool for precise genome editing, used to integrate genetic constructs into specific genomic loci. [9] | Ensures consistent genetic background when comparing the effects of different genetic modifications. [9] |

How Heterologous Pathways Disrupt Cellular Redox and Energy Homeostasis

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Cofactor Imbalance in Engineered Pathways. This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers addressing the common challenge of redox and energy disruption when introducing heterologous pathways into microbial hosts. Introducing non-native metabolic pathways often overwhelms the host's native cofactor pools and energy systems, leading to metabolic burden, redox imbalance, and reduced product yield [14] [15]. The guides below are designed to help you diagnose, understand, and resolve these specific issues, framed within the broader thesis of achieving balanced cofactor metabolism for efficient bioproduction.

Troubleshooting FAQs

What are the primary indicators of redox imbalance in my engineered strain?

Several phenotypic and metabolic signs can indicate your strain is experiencing redox stress:

- Growth Retardation: Observed slow growth or low maximum biomass, often from resource competition between heterologous expression and host maintenance [14].

- Byproduct Accumulation: Build-up of metabolic intermediates or organic acids (e.g., acetate) suggests inefficient metabolic flux and disrupted redox balancing [14].

- Reduced Product Titer: Insufficient cofactor supply can directly limit the activity of cofactor-dependent enzymes in your pathway [15].

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: At the single-cell level, significant cell-to-cell variation in oxidative states and metabolite levels can be a key indicator, as revealed by single-cell metabolomics [16].

Why does my pathway with multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes perform poorly?

Cytochrome P450 enzymes are particularly challenging due to their complex cofactor demands:

- High Cofactor Demand: Each P450 catalytic cycle consumes NADPH and involves redox partners like cytochrome P450 reductases (CPRs) that require FAD(H₂) [17].

- Electron Leakage: Inefficient electron transfer from CPRs to P450s can cause electrons to leak, generating Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) that damage cellular components [17].

- Cellular Mislocalization: Poor localization of these membrane-bound enzymes in the endoplasmic reticulum can further reduce efficiency [17].

My pathway requires NADPH, but the cell's NADPH regeneration is insufficient. What can I do?

This is a common bottleneck. A multi-pronged "open source and reduce expenditure" strategy is often effective [18]:

- Enhance Supply ("Open Source"):

- Reprogram central carbon metabolism to favor the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), a major NADPH source [15] [18].

- Introduce heterologous transhydrogenases (e.g., udhA) or NADH kinases (e.g., pos5) to convert the NADH pool to NADPH [15] [18].

- Overexpress enzymes in the native NADPH synthesis pathway [18].

- Reduce Consumption ("Reduce Expenditure"):

How can I dynamically sense and manage redox imbalances?

Implementing biosensors allows for real-time monitoring and regulation:

- Dual-Sensing Biosensors: Develop biosensors that respond to both the target product (e.g., L-threonine) and NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio. These can be coupled with Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to screen for high-producing strain variants [18].

- Enzyme-Based Regulation: Utilize enzymes like phosphite dehydrogenase (PtxD), which regenerates NADH from phosphite. This can decouple cofactor supply from central metabolism, providing a flexible way to boost driving force for reduction reactions without over-burdening native pathways [19].

Quantitative Impact of Cofactor Engineering

The following table summarizes quantitative data from recent studies demonstrating the success of various cofactor engineering strategies in boosting production.

Table 1: Cofactor Engineering Outcomes in Recent Metabolic Engineering Studies

| Target Product | Host Organism | Key Cofactor Strategy | Reported Titer/Yield | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Pantothenic Acid | E. coli | Integrated optimization of NADPH, ATP, and one-carbon (5,10-MTHF) metabolism. | High-efficiency production; yield surpassed previously reported maximums. [15] | |

| L-Threonine | E. coli | Redox Imbalance Forces Drive (RIFD): Increased NADPH pool and reduced its consumption. | 117.65 g/L; Yield: 0.65 g/g glucose [18] | |

| Asiatic Acid | S. cerevisiae | Engineered P450-CPR systems, enhanced NADPH regeneration, and boosted FAD/heme supply. | 1068.92 mg/L (in a 5-L bioreactor) [17] | |

| Poly(3HB-co-LA) | E. coli | PtxD-based NADH regeneration module to drive lactate formation. | Lactate fraction up to 41.3 mol%; 8.57 g/L copolymer [19] | |

| Adipic Acid | E. coli | Balanced cofactor metabolism via udhA and dppD overexpression. | 4.97 g/L (in a 5-L bioreactor) [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Redox Imbalance Forces Drive (RIFD) Strategy

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to create and harness an imbalanced NADPH pool to drive product synthesis, as used for L-threonine production [18].

- Strain Background: Use an L-threonine-producing E. coli strain (e.g., strain TN) as the starting chassis.

- Increase NADPH Pool ("Open Source"):

- Strategy I (Cofactor Conversion): Express a soluble transhydrogenase (e.g., udhA) to convert NADH to NADPH.

- Strategy II (Heterologous Enzymes): Introduce a heterologous, NADPH-dependent enzyme like GapC from Clostridium acetobutylicum to replace the native NADH-dependent GAPDH.

- Strategy III (NADPH Synthesis): Overexpress enzymes in the NADPH synthesis pathway, such as NAD kinase (pos5).

- Reduce NADPH Consumption ("Reduce Expenditure"): Use genome editing to knockout non-essential NADPH-consuming genes (e.g., gnd, aspA).

- Strain Evolution: Subject the redox-imbalanced strain to Multiplexed Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) to introduce mutations that further improve growth and production.

- High-Throughput Screening: Employ a NADPH and product (L-threonine) dual-sensing biosensor combined with FACS to isolate high-performing clones.

Protocol 2: Engineering a Cofactor-Coupled P450 System

This protocol details steps to alleviate redox limitations in pathways involving cytochrome P450 enzymes, as demonstrated for asiatic acid biosynthesis [17].

- Combinatorial P450-CPR Screening:

- Clone candidate P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP716A subfamily) and Cytochrome P450 Reductases (CPRs) from various plant species into compatible expression vectors.

- Co-transform different P450-CPR pairs into your S. cerevisiae production host and screen for the combination that yields the highest titer of the desired oxidized product.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Engineering:

- Overexpress key ER membrane biosynthesis genes (e.g., ino2, ino4) to expand the ER surface area, providing more membrane for P450 localization.

- Modular Cofactor Supply Enhancement:

- NADPH Regeneration: Overexpress enzymes in the PPP (e.g., ZWF1) or introduce a transhydrogenase.

- FAD Supply: Overexpress riboflavin kinase (*RFK) to enhance the conversion of riboflavin to FAD.

- Heme Biosynthesis: Overexpress genes in the heme biosynthesis pathway (e.g., HEM2, HEM12) and consider feeding the precursor 5-aminolevulinate (5-ALA).

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Scale up the production of the best-performing engineered strain in a controlled bioreactor to validate titers.

Diagram: Redox Disruption and Restoration Logic. This diagram visualizes the logical flow of how heterologous pathways disrupt homeostasis and the corresponding engineering interventions to restore balance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Addressing Redox and Cofactor Imbalance

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble Transhydrogenase | Converts NADH to NADPH, balancing redox pools. | E. coli UdhA [18]. |

| NAD Kinase | Phosphorylates NAD⁺ to NADP⁺, expanding the NADPH precursor pool. | S. cerevisiae Pos5 [15]. |

| Phosphite Dehydrogenase (PtxD) | Regenerates NADH from NAD⁺ using phosphite, providing a flexible, external driver for reductive biosynthesis. | Useful for driving NADH-dependent reactions like lactate production [19]. |

| Cofactor Biosensors | Enables real-time monitoring of NADPH/NADP⁺ ratios or product levels for high-throughput screening. | Dual-sensing biosensors for L-threonine and NADPH used with FACS [18]. |

| Heterologous Cytochrome P450 Reductases (CPRs) | Provides efficient electron transfer from NADPH to cytochrome P450 enzymes, improving catalysis and reducing ROS. | Screen CPRs from various plant species (e.g., Arabidopsis, C. roseus) for optimal P450 pairing [17]. |

| Heme Precursor (5-ALA) | Feed to boost intracellular heme levels, essential for P450 and other hemo-enzyme function. | 5-Aminolevulinate [17]. |

Diagram: Cofactor Engineering and Metabolic Flux. This diagram shows how key reagents and enzymes (highlighted) interface with central metabolism to enhance the supply of NADPH, NADH, and other cofactors for heterologous pathways.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Hurdles

Q1: Why does my engineered S. cerevisiae strain produce high amounts of xylitol instead of ethanol when grown on D-xylose?

A: This is a classic symptom of cofactor imbalance in the heterologously expressed fungal pentose utilization pathway [3] [21] [22].

- Root Cause: The fungal D-xylose pathway uses two enzymes with different cofactor specificities. Xylose reductase (XR) prefers NADPH to reduce D-xylose to xylitol. Subsequently, xylitol dehydrogenase (XDH) uses NAD+ to oxidize xylitol to D-xylulose [21] [22]. This mismatch creates an imbalance in the cell's redox cofactor pools, leading to xylitol accumulation and reduced ethanol yield.

- Diagnosis: Monitor extracellular metabolite profiles (sugars, xylitol, ethanol) and intracellular cofactor ratios (NADPH/NADP+, NADH/NAD+). A significant accumulation of xylitol is a key indicator [3].

Q2: Our cofactor-balanced strain shows good performance in lab-scale cultures but fails to scale up. What could be the issue?

A: This often relates to inadequate mass transfer and cellular viability in larger-scale bioreactors [23].

- Root Cause: Inefficient transport of substrates and products between cellular compartments or the extracellular environment can become a critical bottleneck at scale. Furthermore, engineered strains with high metabolic loads may show reduced viability in industrial conditions [23].

- Diagnosis: Perform flux balance analysis (FBA) at different scales to identify potential transport limitations. Check for a significant drop in cell viability between small and large-scale fermentations [23] [3].

Q3: After engineering the pentose pathway, sugar consumption is sequential (glucose first, then pentoses) instead of simultaneous, prolonging fermentation time. How can this be resolved?

A: This is due to catabolite repression, a native regulatory mechanism in yeast that prioritizes glucose consumption [24].

- Root Cause: Even in engineered strains, the presence of glucose can strongly inhibit the uptake and metabolism of pentose sugars like xylose and arabinose [24].

- Diagnosis: Measure the consumption rates of glucose and pentose sugars (xylose, arabinose) when provided in a mixture. Sequential consumption patterns confirm catabolite repression [24]. Solutions involve evolutionary engineering for co-utilization or engineering regulatory networks to dampen glucose repression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental difference between a cofactor-imbalanced and a cofactor-balanced pentose pathway?

A: The key difference lies in the cofactor specificity of the second enzyme in the pathway, XDH.

- Imbalanced Pathway: XR (NADPH-dependent) → XDH (NAD+-dependent). This consumes NADPH and produces NADH, creating a redox cofactor imbalance [21] [22].

- Balanced Pathway: The cofactor specificity of XDH is engineered to use NADP+, making the pathway redox-neutral as both steps now utilize the NADP+/NADPH couple [3] [22].

Q: Beyond protein engineering, what other metabolic engineering strategies can help alleviate cofactor imbalance?

A: Two effective strategies are:

- Cofactor Regeneration: Introduce alternative systems for NADPH regeneration. Expressing a heterologous NADP+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GDP1) provides a route to generate NADPH without coupling it to CO2 production, enhancing ethanol yield from D-xylose [21].

- Compartmentalization: Localize pathway enzymes in specific organelles like the cytoplasm and peroxisomes to create favorable microenvironments, isolate pathways, and enhance flux. This spatial separation can improve the production of compounds like squalene and α-farnesene [23].

Q: Are there native yeasts that efficiently ferment pentoses without cofactor imbalance issues?

A: Yes, non-conventional yeasts like Spathaspora passalidarum and Scheffersomyces stipitis possess innate pentose utilization pathways [24]. However, they often face other challenges, such as strong inhibition of xylose metabolism by glucose and lower tolerance to industrial stressors like ethanol and inhibitors from lignocellulosic pretreatments [24].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from computational and experimental studies on cofactor balancing in S. cerevisiae.

Table 1: Impact of Cofactor Balancing on Pentose Fermentation Performance

| Strain / Model Configuration | Ethanol Production | Xylitol Production | Substrate Utilization Time | Key Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered Cofactor-Imbalanced Model | Baseline | High | Baseline | XR (NADPH), XDH (NAD+) |

| Engineered Cofactor-Balanced Model | Increased by 24.7% [3] [22] | Significantly Lowered [21] | Reduced by 70% [3] [22] | XDH cofactor specificity switched to NADP+ [3] [22] |

| Strain with GDP1 Expression & ZWF1 Deletion | Higher Rate and Yield [21] | Levels Lowered [21] | Information Not Specified | Alternative NADPH regeneration via NADP-GAPDH [21] |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnostic and Solution Workflow

The following diagram and protocol outline a standard workflow for diagnosing cofactor imbalance and implementing a balancing strategy.

Diagram 1: Workflow for diagnosing and solving cofactor imbalance.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Fermentation and Metabolite Profiling:

- Cultivate your engineered S. cerevisiae strain in a defined medium with D-xylose or L-arabinose as the sole carbon source under microaerobic conditions [3] [21].

- Collect samples periodically throughout the fermentation.

- Analyze supernatant using HPLC to quantify the concentrations of the substrate (xylose/arabinose), the product (ethanol), and the key intermediate (xylitol). A high and persistent xylitol titer is a primary indicator of imbalance [3] [22].

Diagnosis of Cofactor Imbalance:

- Correlate the metabolite profile with the known cofactor requirements of your heterologous pathway.

- For the fungal D-xylose pathway, the simultaneous depletion of NADPH (for XR) and generation of NADH (by native XDH) confirms the imbalance [21] [22]. Genome-scale metabolic modeling (GSMM) can be used to predict this flux imbalance in silico [3] [22].

Implementation of Balancing Strategy:

- Protein Engineering: Use site-directed mutagenesis to alter the cofactor specificity of XDH from NAD+ to NADP+. This is a targeted approach to make the pathway redox-neutral [3] [22].

- Cofactor Regeneration: Clone and express the gene for NADP+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GDP1) from a source like Kluyveromyces lactis in your strain. This provides an additional, efficient source of NADPH. For further effect, consider deleting the gene ZWF1 (coding for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) to reduce competition for carbon flux [21].

- Pathway Compartmentalization: Re-target the expression of pathway enzymes to specific organelles. For instance, targeting the pathway to peroxisomes can harness their native biochemical environment and concentrate substrates, potentially mitigating cytoplasmic cofactor issues [23].

Validation:

- Re-run the fermentation with the newly engineered strain and compare the metabolite profiles (see Table 1 for expected outcomes).

- Use techniques like (^{13})C Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA) or constraint-based Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with a genome-scale model to quantitatively confirm the redirection of carbon flux from xylitol to ethanol [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Pentose Pathway Cofactor Balance

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A computational model of the organism's metabolism. | In silico prediction of maximal growth and product yield; simulation of cofactor balancing effects (e.g., iMM904 model for S. cerevisiae) [3] [22]. |

| NADP+-dependent GAPDH (GDP1) | An enzyme that generates NADPH during glycolysis without CO2 production. | Engineered into strains to provide an alternative, efficient route for NADPH regeneration, improving ethanol yield from xylose [21]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | A kit for introducing specific point mutations into DNA sequences. | Used to change the cofactor specificity of key enzymes like Xylitol Dehydrogenase (XDH) from NAD+ to NADP+ [3] [22]. |

| HPLC System | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for separating and quantifying metabolites. | Essential for measuring concentrations of sugars (xylose), alcohols (ethanol), and organic acids (xylitol) in culture broth during fermentation trials [21] [24]. |

Global Metabolic Consequences Revealed by Genome-Scale Models

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical cofactors to consider when engineering a metabolic pathway, and why?

The most critical common cofactors are ATP/ADP, NAD(P)/NAD(P)H, and acetyl-CoA/CoA. These cofactors are indispensable participants in biochemical reactions across industrial microbes. Systematic exploration using genome-scale models has shown they play fundamental roles in determining cell growth, metabolic flux distribution, and industrial robustness. Imbalances in these cofactor pools can trigger widespread metabolic responses to various environmental stresses [25].

FAQ 2: My engineered pathway is theoretically sound but isn't producing the expected yield. Could cofactor imbalance be the cause?

Yes, cofactor imbalance is a common bottleneck. For instance, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered with fungal pentose utilization pathways, inherent cofactor imbalance (where different pathway enzymes prefer different cofactor forms, e.g., NADPH vs. NAD+) leads to metabolite accumulation (like xylitol) and inefficient product formation. Genome-scale modeling can predict these imbalances and their global consequences before you invest in extensive laboratory engineering [22].

FAQ 3: How can I use a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) to diagnose and correct cofactor imbalances?

GEMs allow you to simulate metabolism at a system-wide level. The process involves:

- Reconstructing or using an existing model for your host organism.

- Introducing the engineered pathway into the model, including its specific reactions and cofactor demands.

- Running simulations (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) to predict growth and product yield.

- Analyzing flux distributions to identify cofactor imbalances that create bottlenecks.

- In silico testing of solutions, such as switching enzyme cofactor specificity or introducing support pathways, to rebalance the cofactor pools and improve performance [26] [22].

FAQ 4: What software tools are available for building and analyzing these models?

Several open-source and commercial platforms are available:

- PyFBA: An extensible Python-based package for building models from functional annotations and running Flux Balance Analysis [26].

- COBRA Toolbox: A widely-used MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling [26].

- Model SEED / KBase: Web-based platforms that facilitate the automated reconstruction, gap-filling, and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models [26] [27].

- CoMAP: A specialized tool for analyzing pathways overrepresented with specific cofactors in human, mouse, and yeast biology [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inefficient Substrate Utilization in an Engineered Strain

This problem manifests as slow growth, low product yield, or accumulation of intermediate metabolites when a new substrate (e.g., a pentose sugar like xylose) is introduced to a host organism.

Investigation and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Construction | Build a genome-scale model (GEM) of your engineered strain that includes the new utilization pathway. Use tools like PyFBA or the Model SEED [26] [27]. | A computational model ready for simulation. |

| 2. In silico Diagnosis | Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to simulate growth on the new substrate. Analyze the flux through the engineered pathway and check for cofactor dependencies (e.g., NADH vs. NADPH) in key reactions [22]. | Identification of a potential cofactor imbalance, often seen as a bottleneck reaction. |

| 3. Propose a Solution | In the model, modify the cofactor specificity of the imbalanced enzyme(s) (e.g., change Xylitol Dehydrogenase from NAD+ to NADP+ dependency) to make the pathway redox-cofactor neutral [22]. | The modified model predicts increased substrate uptake and growth rate. |

| 4. Experimental Validation | Use protein engineering to create the cofactor-specificity switch in the lab strain as guided by the model. | The engineered strain shows improved substrate utilization and reduced byproduct accumulation in bioreactor experiments [22]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting this problem using a genome-scale model:

Problem: Low Product Yield Despite High Substrate Consumption

In this scenario, the cell consumes the substrate but directs metabolic resources away from the desired product, often towards biomass or byproducts.

Investigation and Solution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dynamic Simulation | Perform Dynamic FBA (dFBA) to simulate batch fermentation. This tracks metabolite concentrations over time [22]. | The simulation reveals how cofactor availability shifts during fermentation, limiting product synthesis. |

| 2. Analyze Cofactor Pools | Examine the model-predicted dynamics of key cofactors like ATP and NADPH. Check if their consumption in non-essential pathways or futile cycles drains them from the production pathway [25]. | Identification of energy-draining reactions or competing pathways. |

| 3. In silico Intervention | Manipulate cofactor availability and balance in the model. Strategies include: 1) Knocking out competing reactions; 2) Overexpressing enzymes for cofactor biosynthesis [25]. | The model predicts a higher flux towards the desired product and improved final titer. |

| 4. Implementation | Apply the genetic modifications suggested by the model simulation to the production host. | Fermentation data confirms an increase in product yield and a reduction in byproducts. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a Draft Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

Purpose: To build a computational model of an organism's metabolism from its genome sequence, which can be used to simulate growth and diagnose cofactor imbalances [26].

Materials:

- Genome Sequence: FASTA file of the organism's genome.

- Annotation Tool: Software like RAST, PROKKA, or BG7 for identifying genes and assigning functional roles.

- Reconstruction Software: PyFBA, Model SEED, or the COBRA Toolbox.

- Biochemistry Database: Model SEED or KEGG to connect functional roles to biochemical reactions.

Methodology:

- Genome Annotation: Submit the genome sequence to an annotation tool. This identifies protein-encoding genes and assigns them functional roles (e.g., "xylose reductase").

- Convert Roles to Reactions: The reconstruction software maps these functional roles to the enzyme complexes they form and the specific biochemical reactions they catalyze. This step uses the biochemistry database to create a list of all possible metabolic reactions in the organism.

- Build Stoichiometric Matrix: The software converts the list of reactions into a mathematical matrix (the stoichiometric matrix) that defines how metabolites are interconverted.

- Gap Filling: The initial draft model often has gaps (missing reactions) that prevent it from growing in simulation. The software compares the model to known metabolic functions and adds critical missing reactions to enable growth on a defined medium.

- Model Validation: Simulate growth on different carbon sources (e.g., glucose, xylose) and compare the model's predictions with known experimental growth data to assess its accuracy.

Protocol: Simulating Cofactor Balancing with Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (DFBA)

Purpose: To predict the effect of balancing cofactors in an engineered pathway on overall metabolism and product yield over the course of a fermentation [22].

Materials:

- Validated GEM: A genome-scale model of your host organism.

- Simulation Software: PyFBA, COBRA Toolbox, or similar that supports DFBA.

- Computational Resources: A standard desktop computer is often sufficient.

Methodology:

- Model Modification: Introduce the genes, enzymes, and reactions for the engineered pathway (e.g., a fungal xylose pathway) into the base GEM. Create two versions: one with the native, imbalanced cofactor usage and one where the cofactor specificity of key enzymes has been switched to achieve balance.

- Define Fermentation Parameters: Set up the simulation for a batch culture, including initial concentrations of substrates (e.g., glucose and xylose).

- Run DFBA: Execute the DFBA simulation. This method combines FBA with external substrate uptake kinetics to predict time-dependent changes in metabolite levels, biomass, and product formation.

- Analyze Results: Compare the output of the cofactor-imbalanced and cofactor-balanced models. Key metrics to analyze include:

- Ethanol Production: Final titer and production rate.

- Substrate Utilization Time: Time taken to consume the available substrate.

- Byproduct Accumulation: Levels of intermediates like xylitol.

- Global Flux Changes: How flux is redistributed across the entire metabolic network after cofactor balancing.

The diagram below outlines the core steps in the DFBA protocol for analyzing cofactor balance:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key resources used in the construction and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models, as referenced in the provided guides and protocols.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RAST Annotation Server | A web-based service for automated annotation and analysis of microbial genomes. | Generating the initial list of functional roles from a genome sequence to begin model reconstruction [26]. |

| PyFBA (Python for FBA) | An open-source Python library for building metabolic models and performing Flux Balance Analysis. | Converting a list of functional roles into a stoichiometric model and running growth simulations [26]. |

| Model SEED / KBase | An integrated platform for the annotation of genomes and the reconstruction and analysis of metabolic models. | Drafting, gap-filling, and publicly distributing a genome-scale metabolic model [26] [27]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB suite for performing constraint-based reconstructions and analyses of metabolic networks. | Performing advanced analyses like flux variability analysis and creating context-specific models [26]. |

| GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) | An open-source solver for large-scale linear programming problems. | Serving as the optimization kernel for PyFBA or the COBRA Toolbox to solve the FBA problem [26]. |

| KEGG Pathway Database | A collection of manually drawn pathway maps representing molecular interaction and reaction networks. | Visualizing metabolic pathways and checking the consistency of a reconstructed model [29] [30]. |

| CoMAP (Cofactor Mapping & Analysis Program) | A tool to identify pathways significantly dependent on specific cofactors via overrepresentation analysis. | Determining which human biological pathways are most affected by a deficiency in an iron cofactor [28]. |

Strategic Solutions: Methodologies for Cofactor Balancing in Engineered Systems

A major bottleneck in metabolic engineering is cofactor imbalance, where the demand for essential cofactors like NAD(P)H, ATP, FAD, and FMN exceeds the host cell's natural supply, limiting the productivity of engineered pathways [10]. Traditional approaches to regenerate single cofactors often involve extensive genetic modifications that can create metabolic burdens and lack flexibility for different pathway demands [10] [15].

The XR/lactose system represents a minimally perturbing alternative that enhances multiple cofactors simultaneously by increasing intracellular sugar phosphate pools, which serve as precursors for cofactor biosynthesis [10] [31]. This system employs xylose reductase (XR) with the common inducer lactose to create a "user-pool" model where cells draw upon enhanced metabolite pools according to their specific cofactor demands [31] [32].

Understanding the XR/Lactose System

System Mechanism and the "User-Pool" Effect

The XR/lactose system functions by rewiring hexitol metabolism to boost central metabolic intermediates. The mechanism can be summarized as follows:

- Lactose enters the cell and is hydrolyzed to D-glucose and D-galactose [10]

- Xylose reductase (XR), which has activity on both hexoses, reduces them to sorbitol and galactitol respectively [10]

- These sugar alcohols enter degradation pathways to form sugar phosphates (sorbitol-6-phosphate and galactitol-1-phosphate) [10]

- Increased sugar phosphate pools propagate through central metabolism, enhancing precursors for NAD(P)H, FAD, FMN, ATP, and acetyl-CoA biosynthesis [10] [31]

The "user-pool" effect describes how different engineered pathways selectively draw upon these enhanced metabolite pools based on their specific cofactor requirements, as demonstrated by varying metabolite enhancement patterns across different production systems [31] [32].

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

The XR/lactose system has been validated across multiple engineered pathways with different cofactor demands, consistently showing 2-4 fold enhancements in productivity [10] [32]. The table below summarizes key experimental results:

Table 1: Performance Enhancement with XR/Lactose System in Various Production Systems

| Production System | Key Cofactors Required | Enhancement Factor | Specific Productivity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Alcohol Biosynthesis [10] | NADPH, Acetyl-CoA | 3-fold | Increased from 58.1 to 165.3 μmol/L/h; total titer reached 0.77 mg/mL |

| Bioluminescence Light Generation [10] | FMNH₂, NAD(P)H, ATP | 2-4 fold | Significant increase in light output |

| Alkane Biosynthesis [10] | FAD | 2-4 fold | Increased alkane production |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Sugar Reductase Systems for Cofactor Enhancement

| System | Enhancement Mechanism | Relative Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| XR/Lactose [10] | Increases sugar phosphate pools | 3-fold increase in fatty alcohol production | Minimally perturbing, versatile across pathways |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) [10] | NADPH regeneration from glucose | Less yield enhancement than XR | Targets single cofactor specifically |

| Traditional Cofactor Regeneration [15] | Formate dehydrogenase, polyphosphate kinase | Limited efficiency | Does not increase total cofactor pool, can create metabolic burden |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does the XR/lactose system work better than traditional cofactor regeneration approaches? Traditional systems like formate dehydrogenase or polyphosphate kinase regenerate specific cofactors without increasing the total cofactor pool. The XR/lactose system increases precursor sugar phosphate pools, enabling the cell to naturally enhance multiple cofactors based on demand. This "user-pool" effect is more flexible and creates less metabolic burden than extensively engineered pathways [10] [31].

Q2: What is the optimal timing for lactose induction in the XR/lactose system? Lactose should be added during both the protein induction phase and the bioconversion phase. Research shows that lactose supplementation at both stages resulted in optimal productivity, with significant metabolite changes detectable as early as 5 minutes after bioconversion begins [10] [31].

Q3: Can the XR/lactose system be applied to pathways with different cofactor demands? Yes, the system's versatility has been demonstrated in three distinct systems with different cofactor requirements. Metabolomic analysis confirms that different metabolite enhancement patterns occur depending on the specific pathway's cofactor demands, demonstrating the adaptive "user-pool" effect [10] [31] [32].

Q4: How does the XR/lactose system affect overall cell metabolism and growth? Unlike extensive metabolic engineering that can compromise cell fitness, the XR/lactose approach is minimally perturbing. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses show that primarily only metabolites involved in relevant cofactor biosynthesis are altered, minimizing disruptive effects on central metabolism [10].

Q5: What are the key analytical methods for verifying system functionality? Untargeted metabolomics has been crucial for validating metabolite pattern changes. Additionally, transcriptomic analysis confirms the metabolic pathways affected. For specific applications, monitoring output (e.g., bioluminescence, product titers) with and without the system provides functional validation [10] [33].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for XR/Lactose System Implementation

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low productivity enhancement | Incorrect lactose concentration or timing | Use lactose during both induction and bioconversion phases; optimize concentration (typically 2-20 g/L) [10] |

| Reduced cell growth | Metabolic burden from protein overexpression | Verify XR expression levels; consider inducible promoter systems to minimize basal expression [10] |

| Inconsistent results across different pathways | Non-optimized system for specific cofactor demands | Remember the "user-pool" effect varies; analyze specific cofactor requirements of your pathway [31] |

| Difficulty verifying system function | Insufficient metabolic analysis | Implement untargeted metabolomics to detect sugar phosphate and cofactor precursor changes [10] [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for XR/Lactose System Implementation

| Reagent/Component | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Xylose Reductase (XR) from Hypocrea jecorina [10] | Reduces D-glucose and D-galactose to sugar alcohols | Shows activity on both hexoses with kcat values of 4.80±0.20 s⁻¹ (glucose) and 1.28±0.06 s⁻¹ (galactose) |

| Lactose [10] | Inducer and hexose source | Serves dual purpose as inducer and substrate; cost-effective alternative to IPTG |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) host strain [10] | Engineering host | Contains gal mutation preventing natural galactose utilization, directing carbon through XR pathway |

| NADPH [10] | Cofactor for XR activity | Essential for reductase function; intracellular levels are enhanced by the system |

| Fatty acyl-ACP/CoA reductase (FAR) [10] | Validation enzyme system | For testing system with fatty alcohol production (requires NADPH) |

| Bacterial luciferase (LuxCDEAB) [10] | Validation enzyme system | For testing with bioluminescence (requires FMNH₂, NAD(P)H, ATP) |

| Fatty acid photodecarboxylase (FAP) [10] | Validation enzyme system | For testing with alkane production (requires FAD) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Implementation Protocol

Strain Construction and Culture Conditions:

- Clone XR gene from Hypocresa jecorina into appropriate expression vector with inducible promoter [10]

- Transform into E. coli BL21(DE3) host strain alongside pathway-specific enzymes [10]

- Culture conditions: Grow cells in appropriate medium with antibiotics at 37°C until OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8 [10]

- Induction: Add lactose to final concentration of 2-20 g/L to induce protein expression [10]

- Incubation: Continue cultivation for 6 hours post-induction for protein expression [10]

- Bioconversion: Harvest cells and use as biocatalysts in production phase with additional lactose supplementation [10]

Analytical Validation Methods

Metabolomic Analysis:

- Sample collection: Collect samples at multiple time points (as early as 5 minutes for initial changes) [31]

- Quenching: Rapidly quench metabolism using cold methanol or similar methods [33]

- Untargeted metabolomics: Utilize LC-MS platforms to analyze global metabolite changes [10] [33]

- Data analysis: Focus on sugar phosphates, sugar alcohols, and cofactor precursors [10]

Functional Assessment:

- Product quantification: Use GC-MS for fatty alcohols or alkanes; luminometry for bioluminescence [10]

- Cofactor measurements: Employ enzymatic assays or HPLC for NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios [10]

- Transcriptomic analysis: Validate pathway alterations through RNA sequencing [10]

The XR/lactose system represents a significant advancement in cofactor engineering, offering a versatile, minimally disruptive approach to enhance multiple cofactors simultaneously. Its "user-pool" model allows engineered pathways to selectively draw upon enhanced metabolite pools based on their specific cofactor demands, making it applicable across diverse metabolic engineering applications. As synthetic biology continues to address complex pathway engineering challenges, systems like XR/lactose that work with cellular metabolism rather than against it will be crucial for achieving high productivity in microbial cell factories.

Protein Engineering for Altered Cofactor Specificity in Redox Enzymes

FAQs: Cofactor Specificity and Pathway Balancing

Q1: Why is altering the cofactor specificity of redox enzymes important in metabolic engineering?

Altering cofactor specificity is a fundamental strategy to overcome cofactor imbalance in engineered metabolic pathways. Many native enzymes consume NADH, but microbial hosts like cyanobacteria have an inherently NADPH-abundant pool [6]. Using an NADH-dependent enzyme in such a host can cause a net overproduction of NADH, creating reductive stress, inhibiting key metabolic enzymes, and limiting the yield of your target product [4]. By re-engineering enzymes to accept NADPH instead, you can align cofactor demand with the host's natural supply, enhancing pathway efficiency and production titers [6].

Q2: What are the primary strategies for changing the cofactor preference of an enzyme?

The main strategies can be categorized as follows:

- Protein Engineering: Using rational design or directed evolution to mutate the enzyme's cofactor-binding pocket. This is a direct approach to switch specificity from, for example, NADH to NADPH [6].

- Utilizing Non-Canonical Cofactors: A more advanced strategy involves engineering central metabolic enzymes to utilize orthogonal cofactors (e.g., Nicotinamide Mononucleotide, NMN+). This creates a separate redox pool dedicated to your biosynthetic pathway, insulating it from native metabolism [34].

- Cofactor Regeneration Systems: Introducing external enzymes, such as a NADH oxidase (Nox), to oxidize excess NADH to NAD+, thereby regenerating the oxidized cofactor and maintaining redox balance [4].

- Pathway Engineering: Re-engineering upstream metabolic steps to reduce native NADH production or increase NADH consumption, thus addressing the imbalance at the systemic level [4].

Q3: During a directed evolution campaign, my enzyme variants show high activity in cell lysates but fail to improve production in whole-cell assays. What could be wrong?

This common issue often points to problems outside the engineered enzyme itself. Key areas to investigate include:

- Insufficient Cofactor Regeneration: Your variant may be highly active, but the intracellular supply of its preferred cofactor (e.g., NADPH) cannot keep up with the new demand. Consider coupling your enzyme with a cofactor regeneration system [4].

- Persistent Global Redox Imbalance: Even with a specific enzyme switched, the overall pathway or host metabolism may still generate an imbalance (e.g., excess NADH), creating a bottleneck elsewhere and negating the benefit of your engineered enzyme [1] [2].

- Substrate Transport or Toxicity: Ensure your substrate can efficiently enter the cell and that the product or intermediates are not toxic or inhibiting growth.

Q4: How can I troubleshoot a low product titer after integrating a cofactor-specificity mutant into my pathway?

Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide:

- Verify Enzyme Function In Vivo: Confirm that your engineered enzyme is expressed and folded correctly inside the cell. Use SDS-PAGE and in vivo activity assays.

- Measure Intracellular Cofactor Pools: Quantify the NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratios in your engineered strain versus the control. This will directly indicate if the redox imbalance has been resolved or shifted [1].

- Profile Central Metabolites: Analyze key pathway precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA, α-keto acids). A redox imbalance can directly affect their availability, creating a secondary bottleneck [1].

- Check for Genetic Instability: Prolonged fermentation can lead to strain degradation if the redox imbalance imposes a high metabolic burden. Perform serial passage tests to ensure strain stability [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Activity in a Rational Design Mutant

You have designed a cofactor-switched mutant using a structure-based approach, but it shows severely reduced activity.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Greatly reduced catalytic activity | Mutations disrupt the active site geometry or key catalytic residues. | Revert mutations suspected of causing steric clashes. Use a computational tool (e.g., Rosetta) to model the transition state and identify interfering residues [34]. |

| Poor protein expression or solubility | Mutations cause protein misfolding or aggregation. | Co-express with chaperone proteins; lower induction temperature; try different expression strains. |

| Weakened cofactor binding | Mutations in the binding pocket overly weaken interactions with the new cofactor. | Perform saturation mutagenesis at key positions and screen for improved binders. Consider adding second-shell mutations to stabilize the cofactor. |

| Incorrect oligomeric state | Mutations at the subunit interface disrupt the active tetramer formation, which is crucial for some enzymes like GapA [34]. | Introduce compensatory mutations at the oligomer interface to re-stabilize the active form, as demonstrated by the G187Q mutation in GapA [34]. |

Guide 2: Solving Metabolic Imbalances After Enzyme Engineering

Your engineered enzyme functions well in isolation, but the overall production titer in the host organism does not improve.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Accumulation of pathway intermediates | A new rate-limiting step is created elsewhere in the pathway due to cofactor scarcity. | Measure intermediate levels. Engineer the next enzyme in the pathway or modulate its expression. |

| Reduced cell growth or fermentation arrest | The engineered pathway creates a severe redox imbalance (e.g., NADH accumulation), leading to reductive stress [4]. | Implement an NAD+ regeneration system (e.g., express a water-forming NADH oxidase, Nox) [4]. |

| Low titer despite high precursor availability | The cofactor swap is insufficient; the total cofactor pool (NADPH) is being depleted. | Engineer upstream pathways to increase the total NADPH supply (e.g., overexpress glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). |

| High by-product formation (e.g., glycerol) | The host's native metabolism is attempting to correct the redox imbalance through overflow mechanisms [1] [2]. | Knock out competing NADH-consuming pathways (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase) to direct flux toward your product. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rational Design to Switch Cofactor Specificity from NAD+ to NADP+

This protocol outlines a structure-guided approach to engineer a new cofactor binding pocket, based on methods used to create NMN+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapA) [34].

Key Reagents:

- Plasmid containing the wild-type gene of your target enzyme (e.g., gapA from E. coli).

- Kits for site-directed mutagenesis (e.g., Q5 from NEB).

- Purified native cofactor (NAD+) and target cofactor (NADP+ or NMN+).

- Equipment for UV/Vis spectrophotometry to measure enzyme kinetics.

Methodology:

- Identify Key Residues: Analyze the high-resolution crystal structure of your enzyme bound to its native cofactor (e.g., from PDB database). Identify residues within 5 Å of the 2'-phosphate group of the adenine ribose in NADP+ (or the analogous region in NMN+). A key residue is often an amino acid with a side chain that hydrogen-bonds with the 2'- and 3'-hydroxyl groups of NAD+ (e.g., an aspartate or glutamate).

- Design Mutations: To accommodate the extra phosphate group in NADP+, the common strategy is to replace the identified residue with a positively charged one (e.g., Arg, Lys) or a serine to create a hydrogen bond donor for the phosphate [34]. For example, the A180S mutation in GapA was crucial for NMN+ utilization.

- Introduce Mutations: Use site-directed mutagenesis to create the desired point mutations in your plasmid. Verify the sequence by Sanger sequencing.

- Express and Purify Variants: Transform the mutant plasmid into an appropriate expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21). Induce protein expression, lyse the cells, and purify the mutant enzyme using affinity chromatography.

- Characterize Cofactor Specificity:

- Determine the kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) for both the native (NAD+) and new (NADP+/NMN+) cofactors.

- Calculate the specificity switch ( [kcat/Km for new cofactor] / [kcat/Km for native cofactor] ). A successful engineering effort, like the GapA RSQ variant, can achieve a switch factor of over 10,000 [34].

Protocol 2: Implementing an NADH Oxidase (Nox)-Based Cofactor Regeneration System

This protocol details the integration of an external NADH oxidation system to resolve NADH accumulation in a production host [4].

Key Reagents:

- Heterologous gene for a water-forming NADH oxidase (e.g., nox from Streptococcus pyogenes, SpNox).

- Expression vector with an inducible promoter (e.g., pET, pBAD).

- Fermentation equipment for microaerobic or aerobic cultivation.

Methodology:

- Clone and Express Nox: Clone the nox gene into your chosen expression vector. Transform this plasmid into your production strain.

- Optimize Expression: Test different induction points and inducer concentrations (e.g., IPTG, arabinose) to find a level of Nox expression that effectively recycles NADH without compromising cellular ATP production from the respiratory chain.

- Monitor Cofactor Ratios: From fermentation samples, perform metabolite extraction and use enzymatic assays to quantify NADH and NAD+ levels. Compare the NADH/NAD+ ratio in strains with and without the nox gene.

- Evaluate Production: Measure the titer of your target product. A successful implementation will show a lower NADH/NAD+ ratio and a corresponding increase in product formation, as seen in pyridoxine production where such strategies boosted titers to 676 mg/L [4].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Cofactor Engineering Strategies in Various Systems

| Host Organism | Target Product | Engineering Strategy | Key Performance Metric | Result (Engineered vs. Control) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) | Multiple strategies: NAD+ regeneration via Nox; Reduced NADH production in glycolysis. | PN titer in shake flask | 676.6 mg/L vs. baseline (e.g., 453 mg/L) | [4] |

| E. coli | Glycolytic Enzyme (GapA) | Rational design to switch cofactor specificity from NAD+ to NMN+. | Specificity Switch (kcat/Km,NMN / kcat/Km,NAD) | ~28,000-fold switch for the final RSQ variant | [34] |

| Cyanobacteria | Various Biofuels/Chemicals | General approach: Change enzyme cofactor specificity from NADH to NADPH. | Production Yield | Overcomes inherent NADPH/NADH imbalance, enhancing yields of e.g., 1-butanol, isopropanol. | [6] |

| S. cerevisiae | Volatile Compounds (e.g., Isoamyl alcohol) | Targeted perturbation of NAD+/NADH balance. | Metabolite Formation | Significant, coordinated changes in aroma compound profiles, linked to central carbon metabolism. | [1] |

Visualization: Experimental Workflow and Strategies

Cofactor Engineering Workflow

Cofactor Balancing Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function / Application in Cofactor Engineering |

|---|---|

| Non-Canonical Cofactors (e.g., NMN+) | Used in assays to test and characterize enzymes engineered for orthogonal redox cofactor systems, helping to create insulated metabolic pathways [34]. |

| NADH Oxidase (Nox) | A recombinant enzyme, often from Streptococcus pyogenes, used as a tool to oxidize excess NADH to NAD+ in vivo, thereby regenerating the NAD+ pool and relieving reductive stress [4]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Commercial kits (e.g., from NEB or Agilent) used to introduce specific point mutations into plasmid DNA, enabling rational design of cofactor-binding pockets. |

| Cofactor Analogs | Synthetic analogs of NAD+/NADP+ used for structural studies and enzymatic assays to understand binding specificity and guide engineering efforts. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits for NAD/NADH & NADP/NADPH | Ready-to-use kits for the quantitative measurement of intracellular redox cofactor ratios, essential for diagnosing imbalance and validating the success of engineering interventions [1]. |

Transhydrogenase-like Shunts for NADH/NADPH Interconversion

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary physiological roles of the two transhydrogenase isoforms in E. coli? The two transhydrogenase isoforms in E. coli have divergent, specialized functions to provide metabolic flexibility. The proton-translocating, energy-consuming transhydrogenase PntAB serves as a major source of NADPH for biosynthesis, accounting for 35-45% of biosynthetic NADPH during standard aerobic growth on glucose. In contrast, the energy-independent transhydrogenase UdhA is crucial for re-oxidizing NADPH under metabolic conditions where its formation is excessive, such as growth on acetate or in a phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi) mutant catabolizing glucose via the pentose phosphate pathway [35]. Their expression is modulated by the cellular redox state, allowing the cell to dynamically respond to varying catabolic and anabolic demands [35].