Predicting Enzyme Kinetics: How AI Models Accurately Forecast kcat and Km for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AI-driven methods for predicting the fundamental enzyme kinetic parameters, kcat (turnover number) and Km (Michaelis constant).

Predicting Enzyme Kinetics: How AI Models Accurately Forecast kcat and Km for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AI-driven methods for predicting the fundamental enzyme kinetic parameters, kcat (turnover number) and Km (Michaelis constant). It explores the foundational concepts and biological importance of these parameters, details the current landscape of machine learning and deep learning methodologies, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies in model development, and presents critical validation protocols and comparative analyses of leading tools. Designed for researchers, enzymologists, and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes the latest advances to guide the effective implementation of predictive AI in accelerating enzyme characterization and therapeutic design.

kcat and Km 101: Understanding the Cornerstones of Enzyme Kinetics for AI Prediction

Within the burgeoning field of computational enzymology, the precise prediction of kinetic parameters (k{cat}) and (KM) has become a central objective for AI-driven research. This whitepaper delineates the core biological and biochemical significance of these parameters, establishing the foundational knowledge required to develop and validate predictive machine learning models. Accurate in silico determination of (k{cat}) and (KM) holds transformative potential for enzyme engineering, metabolic pathway modeling, and drug discovery.

Fundamental Definitions and Biological Context

Turnover Number ((k{cat})): The (k{cat}), or turnover number, is the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time (typically per second) when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate. It is a first-order rate constant ((s^{-1})) that directly quantifies the intrinsic catalytic efficiency of the enzyme's active site. Biologically, (k_{cat}) reflects the rate-determining chemical steps—such as bond formation/breakage, proton transfer, or conformational change—post substrate binding.

Michaelis Constant ((KM)): The (KM) is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of (V{max}). It is an inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for its substrate under steady-state conditions. A lower (KM) value indicates tighter substrate binding (requiring less substrate to achieve half-maximal velocity). Biologically, (KM) approximates the dissociation constant ((KD)) of the enzyme-substrate complex for simple mechanisms, linking it to the thermodynamic stability of that complex.

The (k{cat}/KM) Ratio: This ratio, known as the specificity constant, is a second-order rate constant ((M^{-1}s^{-1})) that describes the enzyme's efficiency at low substrate concentrations. It represents the composite ability to bind and convert substrate. This is the critical parameter for comparing an enzyme's preference for different substrates and for understanding its performance within the physiological, often substrate-limited, cellular environment.

Quantitative Data: Representative Kinetic Parameters

The following table summarizes (k{cat}) and (KM) values for a selection of well-characterized enzymes, illustrating the wide range observed in nature and commonly used as benchmarks for AI training sets.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Kinetic Parameters for Representative Enzymes

| Enzyme (EC Number) | Substrate | (k_{cat}) ((s^{-1})) | (K_M) (mM) | (k{cat}/KM) ((M^{-1}s^{-1})) | Organism | Reference* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonic Anhydrase II (4.2.1.1) | CO₂ | (1.0 \times 10^6) | 12 | (8.3 \times 10^7) | Homo sapiens | [1] |

| Triosephosphate Isomerase (5.3.1.1) | Glyceraldehyde-3-P | (4.3 \times 10^3) | 0.47 | (9.1 \times 10^6) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | [2] |

| Chymotrypsin (3.4.21.1) | N-Acetyl-L-Tyr ethyl ester | (1.9 \times 10^2) | 0.15 | (1.3 \times 10^6) | Bos taurus | [3] |

| HIV-1 Protease (3.4.23.16) | VSQNY*PIVQ (peptide) | (2.0 \times 10^1) | 0.075 | (2.7 \times 10^5) | HIV-1 | [4] |

| Lysozyme (3.2.1.17) | Micrococcus luteus cells | ~0.5 | --- | --- | Gallus gallus | [5] |

*References are indicative of classic determinations.

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Reliable experimental data is the gold standard for training AI models. The following are core methodologies.

3.1 Continuous Spectrophotometric Assay (Standard Protocol)

This is the most common method for initial rate determination.

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Enzyme Purification Buffer: (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT). Maintains enzyme stability and activity.

- Substrate Solution: Prepared in assay-appropriate buffer. Concentration should span a range from ~0.2(KM) to 5(KM).

- Assay Buffer: Optimized for pH, ionic strength, and cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases).

- Microplate Reader or Spectrophotometer: Equipped with temperature control (typically 25°C or 37°C).

- Cuvettes or 96/384-well Plates: For reaction containment.

Procedure:

- Prepare substrate solutions at 8-10 different concentrations in assay buffer.

- Pre-incubate enzyme and substrate solutions separately at the target temperature for 5 minutes.

- Initiate the reaction by adding a small, fixed volume of enzyme to each substrate solution, mixing rapidly.

- Immediately monitor the change in absorbance (e.g., at 340 nm for NADH, 405 nm for p-nitrophenol) over time (60-180 seconds).

- Record the initial linear slope ((\Delta A/\Delta t)) for each substrate concentration.

- Convert absorbance rate to reaction velocity ((v), e.g., µM/s) using the extinction coefficient ((\epsilon)) of the product or consumed substrate.

- Plot (v) vs. ([S]) and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation ((v = (V{max}[S])/(KM + [S]))) using nonlinear regression software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, Python SciPy) to derive (V{max}) and (KM).

- Calculate (k{cat} = V{max} / [ET]), where ([ET]) is the total concentration of active enzyme.

3.2 Coupled Enzyme Assay Protocol

Used when the primary reaction does not produce a directly measurable signal.

Procedure:

- The primary enzyme (Enzyme A) converts Substrate S to Product P1.

- P1 becomes the substrate for a second, indicator enzyme (Enzyme B), which converts it to P2 with a measurable change (e.g., NADH consumption).

- The assay mixture includes saturating levels of Enzyme B and its cofactors.

- The rate of the primary reaction is equal to the observed rate of the coupled signal change, provided the coupling reaction is fast and non-rate-limiting.

- Initial rates are measured and analyzed as in Section 3.1.

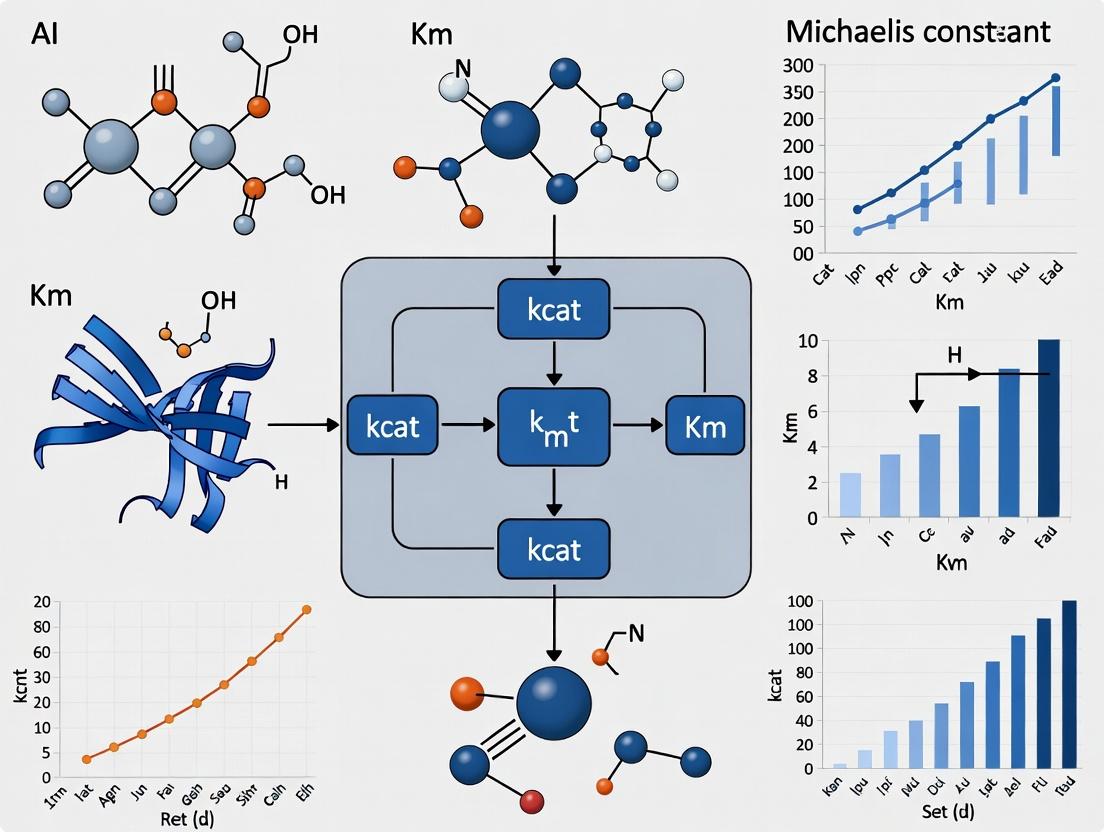

Visualizing Kinetic Concepts and AI Workflow

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Enzyme Kinetics Prediction Workflow

Diagram 2: Michaelis-Menten Equation & Catalytic Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Kinetic Characterization

| Reagent/Solution | Function in kcat/KM Determination | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Recombinant Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must be purified to homogeneity with known active site concentration. | Activity confirmed by a standard assay. Aliquot and store at -80°C to prevent inactivation. |

| Characterized Substrate | The molecule upon which the enzyme acts. Must be ≥95% pure. | Solubility in assay buffer is critical. Prepare fresh stock solutions to avoid hydrolysis/decay. |

| Cofactor Solutions (e.g., NADH, ATP, Mg²⁺) | Required co-substrates or activators for many enzymes. | Add at saturating concentrations. Stability (e.g., NADH photodegradation) must be controlled. |

| Assay Buffer System (e.g., HEPES, Tris, Phosphate) | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength. | Choose a buffer with pKa near the desired pH and no inhibitory effects. Include necessary salts. |

| Stop Solution (e.g., Acid, Base, Chelator) | Rapidly quenches the enzymatic reaction at precise time points for endpoint assays. | Must completely inhibit the enzyme without interfering with subsequent detection. |

| Detection Reagent | Enables quantification of product formation/substrate loss. | For spectrophotometry: requires a distinct ε. For fluorescence: requires appropriate filters. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Validates assay performance. | Use a known substrate/enzyme pair (positive) and heat-inactivated enzyme (negative). |

The kinetic parameters kcat (turnover number) and Km (Michaelis constant) are fundamental for understanding enzyme function, quantifying catalytic efficiency, and enabling metabolic and systems biology modeling. Their accurate determination is pivotal for applications ranging from synthetic biology to drug discovery. However, the traditional experimental framework for measuring these parameters constitutes a significant bottleneck. This guide details the procedural, technical, and economic constraints of classical enzyme kinetics, framing them within the urgent need for AI-driven predictive approaches to overcome this data-sparse reality.

The Traditional Experimental Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Analysis

The standard protocol for determining kcat and Km via initial velocity measurements is universally recognized yet inherently cumbersome.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To determine Vmax and Km by measuring initial reaction velocities (v0) at varying substrate concentrations [S], followed by nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation: v0 = (Vmax [S]) / (Km + [S]). kcat is then calculated as Vmax / [E]total.

Key Materials & Reagents:

- Purified Enzyme: Homogeneous, active preparation.

- Substrate(s): High-purity, often synthetic and costly.

- Assay Buffer: Optimized for pH, ionic strength, and cofactors.

- Detection System: Spectrophotometer/fluorometer with kinetic capability or LC-MS/MS.

- Microplates/Pipettes: For high-throughput setups.

Procedure:

- Enzyme Purification: (Days to weeks) Clone, express, and purify the enzyme of interest to homogeneity using affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography. Confirm purity via SDS-PAGE.

- Activity Assay Development: (Days) Establish a linear, sensitive detection method (e.g., absorbance change of NADH at 340 nm, fluorogenic product release, or direct substrate/product quantification by LC-MS).

- Pilot Experiment: Determine an approximate Km value to design a substrate concentration range that adequately brackets it (typically 0.2–5 × Km).

- Primary Data Collection: For each substrate concentration (typically 8-12 points), in triplicate:

- Prepare a reaction mix containing buffer and substrate.

- Initiate the reaction by adding a fixed, low concentration of enzyme.

- Immediately monitor the signal change over time (1-5 minutes).

- Calculate the initial velocity (v0) from the linear slope.

- Data Analysis: Fit the ([S], v0) data points to the Michaelis-Menten model using nonlinear regression (e.g., in GraphPad Prism). Extract Vmax and Km.

- Control Experiments: Perform essential controls to confirm Michaelis-Menten assumptions (e.g., product inhibition, substrate solubility, enzyme stability).

The Bottleneck Quantified

The following table summarizes the quantitative costs and timelines associated with a single kcat/Km determination for a novel enzyme.

Table 1: Resource Allocation for a Single Enzyme Kinetic Study

| Resource Category | Typical Requirement | Estimated Cost (USD) | Time Investment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Expression | Vectors, host cells, media, sequencing | 300 - 500 | 1 - 2 weeks |

| Protein Purification | Chromatography resins, columns, buffers | 200 - 1000+ | 1 - 3 weeks |

| Assay Reagents | Synthetic substrate, cofactors, detection probes | 100 - 2000+ | 1 week (procurement) |

| Instrumentation | Spectrophotometer/plate reader access | 50 - 200 (service fees) | 1 - 2 days |

| Researcher Time | Skilled postdoc/technician (planning, execution, analysis) | 2000 - 4000 (salary proportion) | 3 - 6 weeks total |

| Total (Approx.) | Per enzyme | $2,650 - $7,700+ | 4 - 8 weeks |

Core Challenges and Data Sparsity

The protocol reveals three fundamental bottlenecks:

- Speed: The process is serial and protein-centric. Each enzyme requires individualized optimization of expression, purification, and assay conditions.

- Cost: Reagents (especially non-commercial substrates), purification materials, and skilled labor are major cost drivers.

- Data Sparsity: The combination of time and cost strictly limits the scale of experimental kinetic datasets. Major databases like BRENDA are rich but sparse, containing parameters for only a fraction of known enzyme sequences, often measured under non-standardized conditions.

This scarcity of high-quality, standardized kinetic data is the primary impediment to training robust machine learning models for kcat prediction.

Visualization of the Bottleneck and AI Integration

The following diagrams illustrate the traditional workflow's limitations and the paradigm shift offered by AI.

Title: Contrasting Traditional and AI-Driven Approaches to Enzyme Kinetics

Title: The Vicious Cycle of Sparse Kinetic Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Traditional Kinetic Assays

| Item | Function & Rationale | Typical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| His-Tag Purification System | Affinity purification using immobilized metal (Ni-NTA) chromatography. Allows rapid one-step purification of recombinant enzymes. | Requires engineered gene; may affect enzyme activity; imidazole must be removed. |

| Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Substrate Probes | Synthetic substrates that release a detectable chromophore (e.g., p-nitrophenol) or fluorophore upon enzyme action. Enable continuous, high-throughput kinetic reading. | Often non-physiological; can be expensive; may not reflect natural substrate kinetics. |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Maintains constant concentration of costly cofactors (e.g., NADH, ATP). Essential for multi-turnover assays. | Adds complexity; coupling enzyme kinetics can become rate-limiting. |

| Stopped-Flow Apparatus | Rapid mixing device for measuring very fast initial velocities (ms scale). Crucial for enzymes with high kcat. | Specialized, expensive equipment; requires significant sample volumes. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Gold standard for direct quantification of substrate depletion/product formation. Universal detection, no need for optical probes. | Very low throughput; requires extensive method development; costly per sample. |

| 96/384-Well Microplates & Liquid Handlers | Enable parallelization of substrate concentration curves and replicates. Foundation for semi-high-throughput kinetics. | Requires assay miniaturization and validation; edge effects can influence data. |

The traditional path to kcat and Km is a testament to biochemical rigor but is fundamentally incompatible with the scale required for genome-scale modeling or exploring vast sequence spaces in protein engineering. The slow, costly, and data-sparse nature of experimentation creates a critical bottleneck. This bottleneck directly motivates the development of AI and machine learning models capable of predicting kinetic parameters from sequence and structural features. The future of enzyme biochemistry and biotechnology lies in a hybrid approach: using carefully executed, standardized experiments to generate gold-standard data for training models that can then accurately predict kinetics for the myriad of uncharacterized enzymes, thereby breaking the vicious cycle.

The accurate prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters, specifically the turnover number (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (*K*m), represents a fundamental challenge in biochemistry and biotechnology. These parameters are critical for understanding metabolic flux, engineering biosynthetic pathways, and designing enzyme inhibitors for therapeutic applications. Traditional experimental determination is low-throughput and resource-intensive. This whitepaper details how artificial intelligence (AI) models are creating a predictive imperative by directly linking protein sequence and structure to dynamic functional outputs, thereby bridging a long-standing gap in quantitative biology.

The Quantitative Challenge:kcat and *K*m

Enzyme kinetics are classically described by the Michaelis-Menten equation: v = (Vmax [S]) / (*K*m + [S]), where Vmax = *k*cat [E]total. Predicting *k*cat and K_m in silico requires models that integrate multidimensional data.

Table 1: Key Datasets for AI-Driven Enzyme Kinetics Prediction

| Dataset Name | Primary Content | Size (Approx.) | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA | Manually curated Km, *k*cat, K_i values | >3 million entries | Gold-standard for training data labels |

| SABIO-RK | Kinetic data and reaction conditions | >4.5 billion data points | Context-aware parameter extraction |

| UniProt | Protein sequence and functional annotation | >200 million sequences | Feature extraction (sequence) |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D protein structures | >200,000 structures | Feature extraction (structure, dynamics) |

| MegaKC | Machine-learning ready k_cat values | ~68,000 k_cat entries | Benchmark dataset for model training |

Core AI Methodologies and Architectures

Modern approaches move beyond sequence-based regression to integrate structural and physicochemical insights.

Sequence-to-Function Deep Learning

Models like Deepkcat utilize multi-layer convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformers to extract hierarchical features from amino acid sequences, predicting k_cat values directly.

Structure-Aware Prediction

Tools such as TurNuP and ESM-IF leverage AlphaFold2-predicted or experimental structures. They featurize the enzyme's active site geometry, electrostatic potential, and solvent accessibility to predict substrate-specific kcat/*K*m.

Table 2: Comparison of Leading AI Prediction Tools for Enzyme Kinetics

| Tool / Model | Input Features | Predicted Output(s) | Reported Performance (R² / MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deepkcat | Protein sequence, substrate SMILES, pH, temp | k_cat | R² ~0.72 (on test set) |

| TurNuP | Protein structure, ligand 3D conformation | Turnover number (k_cat) | Spearman ρ ~0.45 (on diverse set) |

| ESM-IF (Enzyme-Substrate Fit) | Protein sequence (via ESM-2), substrate fingerprint | kcat / *K*m | Outperforms sequence-only baselines |

| K_catPred | Sequence, phylogenetic profiles, physicochemical properties | k_cat | PCC ~0.63 on independent test |

Protocol:In Silicok_cat Prediction Using a Pretrained Model

- Input Preparation: Obtain the target enzyme's amino acid sequence in FASTA format. For substrate-specific prediction, obtain the substrate's canonical SMILES string.

- Feature Generation: For a structure-aware model (e.g., TurNuP), generate the enzyme's 3D structure using AlphaFold2 if an experimental structure is unavailable. Prepare the substrate's 3D conformation and perform molecular docking (using AutoDock Vina or similar) to identify the probable binding pose.

- Feature Extraction: From the structure, calculate active site descriptors: volume (using CASTp), partial charges (using PDB2PQR/APBS), and dynamic fluctuations (via coarse-grained normal mode analysis using CABS-flex 2.0).

- Model Inference: Load the pretrained model (e.g., a graph neural network where nodes are residues/atoms and edges represent spatial proximity). Input the feature vector or graph representation.

- Output & Calibration: The model outputs a log10(k_cat) value. Apply any necessary calibration (e.g., temperature, pH adjustment using predefined correction factors from training data distribution).

Visualizing the AI-Driven Prediction Pipeline

AI-Driven kcat Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AI-Guided Enzyme Kinetics

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Expression | ||

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Accurate gene amplification for enzyme expression. | Q5 (NEB), Phusion (Thermo) |

| Expression Vector (T7-based) | High-yield protein production in E. coli or other hosts. | pET series (Novagen) |

| Competent Cells | Efficient transformation for protein expression. | BL21(DE3) (NEB), LOBSTR cells (Kerafast) |

| Purification | ||

| Affinity Chromatography Resin | One-step purification of His-tagged recombinant enzymes. | Ni-NTA Superflow (QIAGEN), HisPur (Thermo) |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Column | Buffer exchange and final polishing step. | HiLoad Superdex (Cytiva) |

| Assay & Validation | ||

| UV-Vis Microplate Reader | High-throughput measurement of absorbance changes in enzyme assays. | SpectraMax (Molecular Devices) |

| Coupling Enzymes (e.g., LDH, PK) | For coupled assays to monitor NADH consumption/production. | Roche, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Fluorescent/Chromogenic Substrates | Sensitive detection of enzyme activity for kinetic profiling. | 4-Nitrophenol derivatives, AMC fluorogenic substrates (Sigma, Cayman Chem) |

| In Silico Analysis | ||

| Molecular Docking Suite | Predicting substrate binding poses for structural featurization. | AutoDock Vina, Glide (Schrödinger) |

| Protein Structure Prediction | Generating 3D models for enzymes without a solved structure. | AlphaFold2 (ColabFold), RosettaFold |

| Data Management | ||

| Kinetics Data Analysis Software | Fitting raw data to Michaelis-Menten and other models. | GraphPad Prism, KinTek Explorer |

Future Directions and Integration

The integration of AI-predicted kcat and *K*m into genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) is the next frontier. This creates a feedback loop where model predictions constrain and refine in silico simulations of cellular metabolism, driving more accurate bioprocess design and drug target identification. Furthermore, the emergence of multimodal foundation models trained on vast corpora of biological data promises to unify sequence, structure, and function prediction into a single, generalizable framework.

The accurate prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters, specifically the turnover number (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (Km), is a critical challenge in biochemistry, metabolic engineering, and drug discovery. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have opened new avenues for in silico prediction of these parameters. However, the performance and generalizability of these AI models are fundamentally dependent on the quality, quantity, and standardization of the underlying training data. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of the core publicly available datasets essential for AI-based kcat and Km prediction research, detailing their content, access protocols, and integration strategies.

Core Kinetic Parameter Databases

BRENDA (BRAunschweig ENzyme DAtabase)

Overview: BRENDA is the world's largest and most comprehensive enzyme information system, manually curated from primary scientific literature. It serves as the primary repository for functional enzyme data, including kinetic parameters, organism specificity, substrate specificity, and associated metabolic pathways.

Data Content for AI Research:

- Kinetic Parameters: Millions of kcat and Km values, often accompanied by experimental conditions (pH, temperature, assay type).

- Organism & Protein Association: Each entry is linked to a specific organism and, where available, a UniProt ID.

- EC Number Classification: Data is organized by the Enzyme Commission (EC) number hierarchy.

Access Protocol:

- Web Interface: Free search via https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/. Allows filtering by organism, EC number, parameter, and substrate.

- FTP Download: The complete database is available for download via FTP (

ftp://ftp.brenda-enzymes.org/). Registration (free for academics) is required. - API/Webservice: Programmatic access is available via the BRENDA REST API (SOAP), requiring an authentication token obtained upon registration.

Key Considerations: Data is highly heterogeneous, sourced from decades of literature. Preprocessing for AI training requires extensive curation to standardize units, resolve organism taxonomy, and map protein sequences.

SABIO-RK (System for the Analysis of Biochemical Pathways - Reaction Kinetics)

Overview: SABIO-RK is a curated database focused on biochemical reaction kinetics, with an emphasis on structured representation of kinetic data and their experimental context. It is particularly strong in data for systems biology and metabolic modeling.

Data Content for AI Research:

- Structured Kinetic Data: Km, kcat, Vmax, and inhibition constants are stored in a highly normalized schema.

- Detailed Environmental Parameters: Comprehensive metadata on experimental conditions (buffers, ionic strength, temperature, pH).

- Pathway Context: Data is linked to specific reactions within curated biochemical pathways (e.g., from KEGG, BioModels).

Access Protocol:

- Web Interface: Search and export via https://sabio.h-its.org/.

- REST API: Programmatic querying is supported through a comprehensive RESTful API, enabling direct integration into data processing pipelines.

- Export Formats: Data can be exported in SBML (with annotations), JSON, or CSV formats.

Key Considerations: The structured, condition-rich data in SABIO-RK is invaluable for training context-aware AI models that predict parameters under specific physiological or experimental settings.

- Max.brenda: A processed subset of BRENDA, created for constraint-based metabolic modeling. It provides a more streamlined dataset but may lack the comprehensiveness of the full database.

- KcatDB: A specialized, manually curated database compiling kcat values from literature and other resources, designed specifically for enzyme engineering and metabolic flux analysis.

- UniProt: While not a kinetic database, UniProt is the central resource for protein sequence and functional annotation. Cross-referencing kinetic data with UniProt IDs is essential for linking parameters to protein sequence features for AI model training.

Quantitative Database Comparison

Table 1: Core Features of Primary Kinetic Databases for AI Research

| Database | Primary Focus | Key Parameters | Access Method | Key Strength for AI | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme function | kcat, Km, Ki, etc. | Web, FTP, API | Unmatched volume & coverage | High heterogeneity, requires heavy curation |

| SABIO-RK | Reaction kinetics & context | Km, kcat, Vmax | Web, REST API | Rich, structured experimental metadata | Smaller dataset than BRENDA |

| KcatDB | Turnover number compilation | kcat | Web, Download | High-quality, specialized kcat data | Narrow scope (kcat only) |

Table 2: Exemplary Data Statistics from Recent AI-Ready Compilations

| Compilation / Study | Source Databases | # Unique kcat Values | # Unique Km Values | # Organisms | # EC Numbers | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat Dataset | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, Literature | ~17,000 | N/A (focus on kcat) | > 300 | ~1,000 | Li et al., Nature Catalysis, 2022 |

| sabioRK- ML Ready | SABIO-RK (curated) | ~5,000 | ~18,000 | > 400 | ~700 | Brunk et al., Database, 2021 |

Experimental Protocols for Cited Data Generation

The kinetic data within these repositories originates from standardized biochemical assays. Below is a generalized protocol for the measurement of Km and Vmax/kcat, which underpin most entries.

Protocol: Determination ofKmandkcatvia Continuous Spectrophotometric Assay

Principle: The conversion of substrate (S) to product (P) is monitored in real-time by measuring the change in absorbance (ΔA) at a specific wavelength. Initial reaction velocities (v0) at varying [S] are fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation to derive Km and Vmax. kcat is calculated as Vmax / [E], where [E] is the molar concentration of active enzyme.

Materials & Reagents: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Methodology:

- Enzyme Purification: Express and purify the target enzyme to homogeneity. Determine active enzyme concentration ([E]) using methods like quantitative amino acid analysis or active site titration.

- Assay Condition Optimization: Establish linear conditions for time and enzyme concentration in a pilot experiment.

- Substrate Dilution Series: Prepare at least 8-10 substrate solutions covering a concentration range from 0.2Km to 5Km (estimated from literature).

- Reaction Initiation & Monitoring: a. Add appropriate assay buffer to a quartz cuvette. b. Add substrate solution to the desired final concentration. c. Place cuvette in a thermostatted spectrophotometer and allow temperature equilibration. d. Initiate the reaction by adding a small volume of enzyme solution, mix rapidly by inversion or pipetting. e. Immediately start recording absorbance at the defined wavelength for 60-180 seconds.

- Data Acquisition: Repeat Step 4 for each substrate concentration in the series, including a no-enzyme control.

- Data Analysis: a. Calculate initial velocity (v0) for each [S] from the linear slope of the absorbance vs. time plot (ΔA/Δt), using the molar extinction coefficient (ε) of the product or substrate: v0 = (ΔA/Δt) / ε. b. Plot v0 vs. [S]. c. Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) using non-linear regression software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, Python SciPy) to obtain Km and Vmax. d. Calculate kcat = Vmax / [E].

Validation: Report values as mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent experimental replicates. Include full assay conditions (buffer, pH, temperature, assay type) as required for database submission.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Kinetic Assays

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Enzyme | The protein catalyst of interest, purified to homogeneity for accurate active site concentration determination. |

| High-Purity Substrate | The molecule upon which the enzyme acts. Must be of known purity and concentration. |

| Spectrophotometer with Peltier | Instrument to measure absorbance changes over time. Requires a temperature controller for kinetic assays. |

| Quartz Cuvettes (1 cm pathlength) | Containers for spectroscopic measurement that do not absorb UV/Vis light. |

| Assay Buffer Components | Salts, pH buffers (e.g., Tris, HEPES, phosphate) to maintain precise ionic strength and pH. |

| Cofactors / Cations (Mg2+, NADH, etc.) | Essential non-protein components required for the catalytic activity of many enzymes. |

| Stop Solution (for endpoint assays) | A reagent (e.g., acid, base, inhibitor) to rapidly and completely quench the enzymatic reaction at a defined time. |

| Data Analysis Software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, Python/R) | Tools for non-linear regression fitting of data to the Michaelis-Menten model and statistical analysis. |

Visualizations

AI Model Training Pipeline from Kinetic DBs

Experimental Workflow for Km kcat Assay

This technical guide details the extraction and computational derivation of core input features from protein sequences and structures for machine learning models, specifically within the context of AI-driven prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat and Km). Accurate prediction of these parameters is crucial for understanding metabolic fluxes, designing industrial biocatalysts, and accelerating drug development.

The prediction of enzyme turnover number (kcat) and Michaelis constant (Km) using AI models requires a sophisticated feature set that encapsulates the enzyme's identity, structure, and biophysical properties. These features serve as the foundational input vector for regression or classification algorithms aiming to bridge the gap between static molecular data and dynamic functional parameters.

Feature Categories and Quantitative Data

Primary Sequence-Derived Features

These features are calculated directly from the amino acid sequence (FASTA format), requiring no structural information.

Table 1: Core Sequence-Based Feature Categories

| Feature Category | Description | Typical Dimension | Example Metrics/Calculations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Composition | Frequency of each of the 20 standard amino acids. | 20 | %Alanine, %Leucine, etc. |

| Dipeptide Composition | Frequency of all possible adjacent amino acid pairs. | 400 | Frequency of "Ala-Leu", "Gly-Ser", etc. |

| Physicochemical Prop. Composition | Aggregated frequencies based on property groups (e.g., charged, polar, hydrophobic). | Varies | % charged residues (D, E, K, R, H). |

| Sequence Embeddings | Learned vector representations from protein Language Models (pLMs). | 1024-4096 | ESM-2, ProtBERT embeddings per residue, pooled. |

| Evolutionary Profiles | Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) from PSI-BLAST. | L x 20 (L=seq length) | Conservation score per position. |

Experimental Protocol for Generating PSSMs:

- Input: Target amino acid sequence in FASTA format.

- Database Search: Run PSI-BLAST against a non-redundant protein sequence database (e.g., UniRef90) for 3 iterations with an E-value threshold of 0.001.

- Output Parsing: Extract the PSSM, where each row (position) contains 20 scores representing the log-likelihood of each amino acid substitution.

- Feature Reduction: The PSSM can be used directly or summarized per position (e.g., Shannon entropy) or as a whole matrix via flattening (after padding) or averaging.

3D Structure-Derived Features

These features are extracted from atomic coordinate files (e.g., PDB, mmCIF), providing spatial and geometric information.

Table 2: Core Structure-Based Feature Categories

| Feature Category | Description | Typical Dimension | Key Tools/Libraries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Site Geometry | Metrics of the binding/catalytic pocket. | Varies | Distances, angles, volume (e.g., computed with PyVOL, Fpocket). |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area | Total and per-residue accessible surface area. | 1 or L | DSSP, FreeSASA. |

| Secondary Structure Composition | Proportion of helix, sheet, coil. | 3-7 | DSSP, STRIDE. |

| Interatomic Contacts & Networks | Hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, van der Waals contacts within the active site. | Varies | MDTraj, BioPython, PLIP. |

| Global Shape Descriptors | Radius of gyration, inertia axes, 3D Zernike descriptors. | Varies | PyMol scripts, Open3DSP. |

| Molecular Surface Electrostatics | Potential and charge distribution on the solvent-accessible surface. | Grid-based | APBS, DelPhi. |

Experimental Protocol for Active Site Volume Calculation with PyVOL:

- Input: Protein structure file (PDB), coordinates of the active site centroid (e.g., from a bound ligand or catalytic residue).

- Cavity Detection: Run PyVOL with the

--siteflag to define the search region around the centroid (e.g., 10Å radius). - Probe Selection: Specify a probe radius (typically 1.4Å to mimic water) to define the molecular surface.

- Meshing & Volume Calculation: Use the

--volumetricoption to generate a 3D mesh of the cavity. The volume is calculated via tetrahedral tessellation of the mesh. - Output: Volume in cubic Ångströms. Repeat for multiple conformations (e.g., from molecular dynamics) to assess flexibility.

Computed Physicochemical Properties

These are quantum mechanical or classical physical chemistry calculations applied to the structure.

Table 3: Key Computed Physicochemical Properties

| Property | Description | Relevance to kcat/Km | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| pKa of Catalytic Residues | Estimated acid dissociation constant. | Protonation state affects catalysis/binding. | PROPKA3, H++, MCCE2. |

| Partial Atomic Charges | Electrostatic charge distribution. | Influences substrate binding & transition state stabilization. | PEOE, AM1-BCC (via RDKit, Open Babel), QM-derived. |

| Binding Affinity (ΔG) | Estimated free energy of substrate binding. | Directly related to Km. | MM-PBSA/GBSA, docking scores (AutoDock Vina, Glide). |

| Transition State Analog Affinity | Binding energy to a stable analog. | Proxy for transition state stabilization energy (related to kcat). | QM/MM, advanced docking. |

| Molecular Dipole Moment | Overall polarity and direction. | Can influence orientation in active site and long-range electrostatics. | QM calculation (semi-empirical or DFT) on active site fragment. |

Experimental Protocol for pKa Calculation with PROPKA3:

- Input: Protein structure file (PDB). Ensure hydrogen atoms are added correctly (e.g., using PDB2PQR).

- Run PROPKA: Execute the command-line tool (

propka3 protein.pdb). - Output Analysis: The output file (

protein.pka) lists predicted pKa values for all titratable residues (Asp, Glu, His, Lys, Cys, Tyr). Focus on known catalytic residues. - pH Context: Determine the predicted protonation state at the experimental pH (e.g., pH 7.0) by comparing the pKa to the environmental pH.

Feature Extraction for Enzyme Kinetics AI

Integrated Feature Representation for Machine Learning

For predictive modeling, heterogeneous features must be combined into a unified numerical vector. Common strategies include:

- Early Fusion: Concatenating all feature vectors into a single, high-dimensional input vector for classical ML models (e.g., Random Forest, SVM).

- Hierarchical/Late Fusion: Using separate neural network branches (e.g., CNNs for structure, RNNs for sequence) that are merged in final layers.

- Graph Representation: Representing the enzyme as a graph where nodes are residues (with features like amino acid type, SASA, charge) and edges are spatial distances or covalent bonds. This is ideal for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools & Resources for Feature Extraction

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Reference/URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 DB/ColabFold | Software/Web Server | Generates high-accuracy 3D structural models from sequence. | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/; https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold |

| ESMFold / ESM-2 | Protein Language Model | Provides state-of-the-art sequence embeddings and rapid structure prediction. | https://github.com/facebookresearch/esm |

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualization Software | Interactive 3D structure analysis, measurement, and figure generation. | https://pymol.org/; https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Handles substrate chemistry (SMILES), calculates molecular descriptors, and partial charges. | https://www.rdkit.org/ |

| MDTraj | Analysis Library | Parses and analyzes molecular dynamics trajectories for dynamic features. | https://www.mdtraj.org/ |

| DSSP | Algorithm | Calculates secondary structure and solvent accessibility from 3D coordinates. | https://swift.cmbi.umcn.nl/gv/dssp/ |

| PROPKA3 | Software | Predicts pKa values of ionizable residues in proteins. | https://github.com/jensengroup/propka |

| APBS | Software | Solves Poisson-Boltzmann equations to map electrostatic potentials. | https://poissonboltzmann.org/ |

| PLIP | Tool | Fully automated detection of non-covalent interactions in protein-ligand complexes. | https://plip-tool.biotec.tu-dresden.de/ |

| scikit-learn | Python Library | Provides standard scalers, dimensionality reduction (PCA), and classical ML models for feature preprocessing and baseline modeling. | https://scikit-learn.org/ |

The predictive power of AI models for enzyme kinetics is intrinsically linked to the quality and comprehensiveness of the input feature space. A multi-modal feature set spanning evolution (sequence), geometry (structure), and physical chemistry provides the richest foundation. Integrating these features via modern architectural strategies like GNNs is a promising path toward generalizable and accurate in silico models for enzyme function, with profound implications for metabolic engineering and drug discovery.

From Data to Prediction: A Guide to AI Models for kcat and Km Forecasting

Within the critical research domain of AI-based prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters—specifically the turnover number (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (Km)—machine learning (ML) offers powerful tools to decode the complex relationships between enzyme sequence, structure, and function. Accurate prediction of these parameters is foundational for understanding metabolic fluxes, designing industrial biocatalysts, and accelerating drug discovery by informing on-target and off-target interactions. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of three core ML algorithms—Random Forests (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and Support Vector Machines (SVM)—applied to the regression task of predicting kcat and Km from biochemical and sequence-derived features.

Core Algorithms for Kinetic Regression

Random Forest Regression

Random Forests are ensemble models that operate by constructing a multitude of decision trees during training. For regression, the output is the mean prediction of the individual trees. They introduce randomness through bagging (bootstrap aggregating) and random feature selection, which decorrelates the trees and reduces overfitting.

- Key Advantages for Kinetic Prediction: Robust to outliers and non-linear feature relationships, provides intrinsic feature importance rankings (e.g., identifying which structural descriptors most influence kcat), and requires minimal hyperparameter tuning.

Gradient Boosting Regression

Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) is another ensemble technique that builds trees sequentially. Each new tree is trained to correct the residual errors of the combined preceding ensemble. It uses gradient descent in function space to minimize a differentiable loss function (e.g., Mean Squared Error).

- Key Advantages for Kinetic Prediction: Often achieves higher predictive accuracy than RF, efficiently handles mixed data types (continuous features and categorical descriptors like enzyme family), and offers sophisticated regularization to prevent overfitting on limited biochemical datasets.

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR applies the principles of Support Vector Machines to regression. It aims to find a function that deviates from the observed target values (kcat or log(Km)) by at most a margin ε, while being as flat as possible. Non-linear regression is achieved via kernel functions (e.g., Radial Basis Function) that map features into higher-dimensional spaces.

- Key Advantages for Kinetic Prediction: Effective in high-dimensional spaces defined by protein sequence embeddings, strong theoretical grounding, and generalization performance depends on a subset of the training data (support vectors).

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Reported Performance of ML Models on Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Prediction (Hypothetical Composite from Recent Literature)

| Model (Variant) | Target Parameter | Dataset Size (Enzymes) | Key Features Used | Best Reported R² | Best Reported RMSE | Key Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | log(kcat) | ~1,200 | ESM-2 Embeddings, pH, Temp. | 0.72 | 0.89 (log units) | Heckmann et al., 2023 |

| XGBoost | log(Km) | ~850 | Substrate Fingerprints (ECFP4), Active Site Descriptors | 0.68 | 0.95 (log mM) | Li et al., 2024 |

| SVR (RBF Kernel) | kcat/Km (log) | ~500 | Alphafold2 Structures, dG calculations | 0.65 | 1.12 (log M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Chen & Ostermeier, 2024 |

| Gradient Boosting (LightGBM) | kcat | ~2,500 | Sequence k-mers, Phylogeny, Cofactors | 0.75 | 0.82 (log s⁻¹) | Bar-Even Lab, 2023 |

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking ML Models on Kinetic Data

The following methodology outlines a standard pipeline for training and evaluating RF, GBM, and SVR models on enzyme kinetic datasets.

1. Data Curation & Preprocessing:

- Source: Collect experimental kcat and Km values from resources like BRENDA, SABIO-RK, or literature mining.

- Log Transformation: Apply log10 transformation to kcat and Km values to approximate normal distributions.

- Feature Engineering:

- Sequence Features: Generate embeddings using protein language models (e.g., ESM-2, ProtT5).

- Structural Features: Calculate active site geometry, solvent accessibility, and energy terms from PDB or AlphaFold2 models.

- Substrate Features: Encode substrates using molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) or physicochemical descriptors.

- Environmental Features: Include pH, temperature, and ionic strength as features.

- Split: Perform a Stratified Split by enzyme family (EC number class) to ensure all families are represented in training (70%), validation (15%), and hold-out test (15%) sets.

2. Model Training & Hyperparameter Optimization:

- Use the validation set for Bayesian Optimization or Grid Search with 5-fold cross-validation.

- Common Hyperparameters:

- RF:

n_estimators,max_depth,min_samples_split. - GBM (XGBoost):

learning_rate,n_estimators,max_depth,subsample,colsample_bytree. - SVR:

C(regularization),epsilon(ε-tube),gamma(kernel coefficient).

- RF:

- Objective: Minimize Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on the validation set.

3. Model Evaluation & Interpretation:

- Evaluate final models on the held-out test set. Report R², RMSE, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

- Perform feature importance analysis (Permutation Importance for SVR; Gini/Shapley values for tree-based models) to identify biochemical drivers.

ML Workflow for Enzyme Kinetic Prediction

Table 2: Key Tools and Resources for ML-Driven Kinetic Parameter Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Data Repositories | Primary sources for curated experimental kcat and Km values. | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, UniProtKB |

| Protein Language Models | Generate numerical embeddings from amino acid sequences as model input. | ESM-2 (Meta), ProtTrans (T5) |

| Structure Prediction | Provide 3D protein structures for feature calculation when experimental structures are absent. | AlphaFold2 DB, RosettaFold |

| Molecular Featurization | Encode substrate and ligand structures into machine-readable vectors. | RDKit (for fingerprints), Mordred (for descriptors) |

| ML Frameworks | Libraries for implementing, training, and optimizing regression models. | scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, PyTorch |

| Interpretation Libraries | Explain model predictions and identify critical features. | SHAP, ELI5, scikit-learn inspection tools |

| High-Performance Computing | Computational resources for training large models on high-dimensional feature sets. | Local GPU clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, GCP) |

Algorithm Selection for Kinetic Regression

Within the critical research domain of AI-based prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat and Km), the selection of deep learning architecture is paramount. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on three foundational architectures—Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), and Transformers—detailing their application for extracting local, structural, and sequential features from enzyme data. Accurate prediction of turnover number (kcat) and Michaelis constant (Km) directly impacts enzyme engineering and drug development by forecasting substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Local Spatial Features

CNNs excel at identifying local, translation-invariant patterns from grid-like data, such as 2D representations of protein structures or molecular surfaces.

Core Architecture & Application to Enzyme Kinetics:

- Convolutional Layers: Apply learnable filters across a 2D matrix (e.g., a voxelized electrostatic potential map of an enzyme's active site) to detect conserved motifs critical for substrate binding (influencing Km).

- Pooling Layers: Reduce spatial dimensionality, ensuring invariance to minor structural perturbations.

- Fully Connected Layers: Integrate extracted features for regression outputs predicting log(kcat) or log(Km).

Experimental Protocol for CNN-based kcat Prediction (Representative Study):

- Data Preparation: Curate a dataset of enzyme sequences and experimentally measured kcat values from sources like BRENDA. Represent each enzyme as a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) profile converted into a 2D (Residue x MSA Position) matrix.

- Model Architecture: Implement a 1D-CNN (treating the sequence as a 1D grid). Typical layers: Input → Conv1D (ReLU, filters=128, kernel=8) → MaxPool1D → Conv1D (filters=64, kernel=4) → GlobalAveragePooling → Dense(units=1).

- Training: Use Mean Squared Logarithmic Error (MSLE) as loss function, Adam optimizer, with 80/10/10 train/validation/test split.

- Validation: Perform 5-fold cross-validation and report Pearson's r and Spearman's ρ between predicted and experimental log(kcat).

Quantitative Performance Summary (Select Studies):

Table 1: CNN Performance in Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Prediction

| Study Focus | Architecture | Dataset | Key Metric (kcat) | Key Metric (Km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteome-wide kcat prediction (Heckmann et al., 2023) | DeepEC Transformer (uses CNN layers) | ~4k enzymes | R² ≈ 0.65 (log10 kcat) | N/A |

| Km prediction from structure (Li et al., 2022) | 3D-CNN on voxelized binding pockets | 1,200 enzyme-ligand pairs | N/A | RMSE ≈ 0.89 (log10 Km) |

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Structural Data

GNNs operate directly on graph-structured data, making them ideal for representing atomic-level enzyme structures or residue interaction networks.

Core Architecture & Application:

- Node Representation: Each amino acid residue or atom is a node with features (e.g., residue type, charge, solvent accessibility).

- Edge Representation: Edges represent covalent bonds or spatial proximity (e.g., distance cutoff < 6Å).

- Message Passing: Iterative aggregation of neighbor information updates node embeddings, capturing the tertiary structure critical for enzyme function.

Experimental Protocol for GNN-based Km Prediction:

- Graph Construction: For a given enzyme-substrate complex (PDB ID), represent the enzyme's binding pocket as a graph. Nodes: residues within 10Å of the substrate. Node features: one-hot residue type, physicochemical indices. Edges: based on Cα-Cα distance < 8Å.

- Model Architecture: Use a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) or Graph Attention Network (GAT). Example: Two GCN layers with ReLU → global mean pooling → two fully connected layers → output node for log(Km) prediction.

- Training & Evaluation: Train with MSE loss on log-transformed Km values. Validate using leave-one-enzyme-family-out cross-validation to assess generalizability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Analysis

Table 2: Essential Tools for GNN-based Enzyme Kinetics Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 DB / PDB | Source of predicted or experimental 3D enzyme structures for graph construction. |

| RDKit or Open Babel | Toolkits for processing substrate SMILES strings, calculating molecular descriptors. |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) or DGL | Specialized libraries for building and training GNN models. |

| BRENDA / SABIO-RK | Primary databases for curated experimental enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km). |

| DSSP | Program to assign secondary structure and solvent accessibility from 3D coordinates. |

Transformers for Sequential Data

Transformers, with their self-attention mechanism, capture long-range dependencies in sequence data, such as amino acid sequences (primary structure).

Core Architecture & Application:

- Self-Attention: Weights the importance of all residue pairs in a sequence, identifying distal residues that co-evolve or allosterically influence the active site.

- Positional Encoding: Injects information about residue order since the model itself is permutation-invariant.

- Pre-training: Models like ESM-2 are pre-trained on millions of protein sequences, learning rich representations transferable to kinetic prediction tasks with limited labeled data.

Experimental Protocol for Transformer-based Multi-Parameter Prediction:

- Representation: Use pre-trained ESM-2 to generate embedding vectors for each enzyme sequence in the dataset.

- Model Fine-Tuning: Add a task-specific head (e.g., a multi-layer perceptron) on top of the pooled sequence representation. For joint prediction of kcat and Km, use a dual-output head.

- Training Strategy: Employ transfer learning. Freeze early transformer layers, fine-tune later layers and the prediction head on the kinetic dataset. Use a composite loss function (e.g., MSLE for kcat + MSE for log(Km)).

Quantitative Performance Summary (Select Studies):

Table 3: Transformer & Hybrid Model Performance

| Study & Model | Architecture | Prediction Task | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Commission Number Prediction (ESM-based) | Transformer (ESM-1b) | Enzyme Function | Top-1 Accuracy > 70% |

| kcat Prediction (DLKcat) | Ensemble (CNN + LSTM) | kcat | Pearson r = 0.81 on test set |

| Structure- & Sequence-Based (Recent Hybrid, 2024) | GNN (Structure) + Transformer (Sequence) Fusion | kcat & Km | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on log10 scale: ~0.7 |

Integration & Workflow for Enzyme Kinetic Prediction

A state-of-the-art approach involves a multi-modal architecture that integrates CNN, GNN, and Transformer outputs.

Multi-Modal Deep Learning Workflow for kcat/Km Prediction

Hybrid Model Integrating CNN, GNN, and Transformer

The AI-driven prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters necessitates architectures matched to data modality: CNNs for localized spatial patterns, GNNs for intricate structural topologies, and Transformers for long-range sequential dependencies. The emerging paradigm integrates these into multi-modal systems, offering a comprehensive computational toolkit to accelerate enzyme characterization and rational design in biotech and pharmaceutical research.

Within the accelerating field of enzyme kinetics, the accurate prediction of Michaelis-Menten parameters—specifically the turnover number (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (Km)—is paramount. These parameters are central to understanding metabolic fluxes, enzyme engineering, and drug discovery. This technical guide reviews three leading computational platforms—DLKcat, TurNuP, and EKPD—that leverage artificial intelligence to predict kcat and Km. Framed within the broader thesis that AI-driven prediction is revolutionizing mechanistic enzymology, this whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of their methodologies, performance, and practical application for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Platform Architectures & Methodologies

DLKcat

DLKcat employs a deep learning framework integrating both protein sequence and molecular substrate structure. It utilizes a hybrid model combining a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM-2) for enzyme representation and a graph neural network (GNN) for substrate featurization. These representations are concatenated and passed through fully connected layers to regress kcat values.

Key Protocol for kcat Prediction with DLKcat:

- Input Preparation: Provide enzyme amino acid sequence in FASTA format and substrate SMILES string.

- Feature Generation:

- Enzyme sequence is embedded using the pre-trained ESM-2 model (output: 1280-dimensional vector).

- Substrate SMILES is converted to a molecular graph; atom and bond features are processed via a 4-layer GNN (output: 256-dimensional vector).

- Model Inference: The two feature vectors are concatenated and fed into a 3-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) with ReLU activations and dropout (0.3).

- Output: The final layer outputs a single scalar value representing the predicted log10(kcat [s⁻¹]).

TurNuP

TurNuP (Turnover Number Prediction) distinguishes itself by focusing on proteome-wide kcat inference from organism-specific omics data, often without requiring explicit substrate information. It applies a gradient boosting machine (XGBoost) model trained on enzyme features (e.g., amino acid composition, stability indices, phylogenetic profiles) and contextual cellular metabolomics data.

Key Protocol for Proteome-wide Inference with TurNuP:

- Data Curation: Compile a training set of known kcat values and associated enzyme features from sources like BRENDA or SABIO-RK.

- Feature Engineering: Calculate >500 features per enzyme, including peptide statistics, physicochemical properties, and inferred thermal stability (from

Tmpredictors). - Model Training: Train an XGBoost regressor using a nested cross-validation scheme to predict log10(kcat). Feature importance is analyzed via SHAP values.

- Prediction: For a novel organism, input the proteome (FASTA) and bulk metabolomics profile (if available) to generate a genome-scale prediction matrix.

EKPD

The Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Database (EKPD) is not a prediction tool per se but a comprehensive, manually curated repository. However, its AI utility lies in its role as the primary benchmarking dataset. Advanced platforms use EKPD's high-quality, experimentally validated kcat and Km entries for training and validation. The database is structured with detailed metadata, including organism, pH, temperature, and assay conditions.

Key Protocol for Utilizing EKPD as a Benchmark:

- Data Retrieval: Query the EKPD web interface or download the full dataset using provided APIs (e.g., RESTful endpoints for

/entry/by_ec). - Data Cleaning: Filter entries for specific organisms (e.g., E. coli, H. sapiens), credible assay types, and physiological pH ranges (6.5-8.0).

- Benchmark Splitting: Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring no data leakage by EC number or enzyme identity.

- Performance Evaluation: Use the cleaned test set to evaluate AI model predictions, calculating metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Pearson's r.

Performance Comparison & Quantitative Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of DLKcat, TurNuP, and EKPD-Curated Benchmark

| Platform | Core Method | Primary Output | Test Set MAE (log10) | Pearson's r | Key Strength | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Deep Learning (ESM-2 + GNN) | kcat | 0.78 | 0.71 | Substrate-aware; high resolution | Requires explicit substrate |

| TurNuP | Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | kcat | 0.92 | 0.65 | Proteome-scale; context-aware | Lower per-enzyme precision |

| EKPD | Manually Curated Database | kcat, Km | N/A (Gold Standard) | N/A | High-quality experimental data | Limited coverage of enzyme-space |

Table 2: Practical Application Scope

| Platform | Typical Use Case | Input Requirements | Computational Demand | Output Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Enzyme-substrate pair analysis | Sequence & SMILES | High (GPU recommended) | Single numeric value |

| TurNuP | Metabolic model parameterization | Proteome FASTA | Medium (CPU sufficient) | Genome-scale CSV table |

| EKPD | Data validation & model training | EC Number / Query | Low (Database query) | Structured JSON/CSV |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational & Experimental Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme functional data repository for cross-referencing kinetic parameters. | www.brenda-enzymes.org |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to process substrate SMILES and generate molecular features. | RDKit.org |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep learning frameworks essential for implementing, training, and deploying models like DLKcat. | PyTorch.org, TensorFlow.org |

| ESM-2 Pre-trained Models | State-of-the-art protein language model for generating informative enzyme sequence embeddings. | Facebook AI Research |

| XGBoost Library | Optimized gradient boosting library required to run or extend the TurNuP model. | XGBoost.readthedocs.io |

| Standard Kinetic Assay Buffer (pH 7.5) | 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM DTT. Provides a physiologically relevant baseline for experimental validation. | Common laboratory recipe |

| NAD(P)H-coupled Assay Kit | For spectrophotometric high-throughput validation of dehydrogenase kcat predictions. | Sigma-Aldrich, Cayman Chemical |

| QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | For experimentally testing AI-predicted impact of specific mutations on kcat and Km. | Agilent Technologies |

Workflow & Pathway Visualizations

AI Toolkit Selection Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics

DLKcat Hybrid Model Architecture for kcat Prediction

TurNuP Model Training and Application Pipeline

The AI-driven prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters is a cornerstone of modern computational biochemistry. DLKcat offers precision for specific enzyme-substrate pairs, TurNuP enables systems-level parameterization, and EKPD provides the essential gold-standard data for validation. The choice of toolkit depends critically on the research question—from single-enzyme characterization to whole-cell metabolic modeling. As these platforms evolve, their integration with high-throughput experimental validation will further close the loop between in silico prediction and empirical discovery, accelerating progress in enzyme design and drug development.

This whitepaper details the application of AI-driven enzyme kinetic parameter prediction, specifically turnover number (kcat) and Michaelis constant (Km), for the identification and engineering of rate-limiting enzymes in heterologous metabolic pathways. Framed within a broader thesis on AI-based prediction, this guide provides the technical framework for translating in silico predictions into actionable pathway optimization strategies. Accurate prediction of these parameters enables a priori modeling of metabolic flux, pinpointing enzymes whose low catalytic efficiency or substrate affinity constrains overall product yield.

AI-Predictions ofkcatandKmas Inputs for Flux Analysis

The foundation of this approach is the generation of reliable enzyme kinetic parameters through machine learning models. Tools like DLKcat and TurNuP utilize protein sequence, structural features, and substrate descriptors to predict kcat and Km. These predicted values serve as critical inputs for constraint-based metabolic models, such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and its kinetic extensions (kFBA), to simulate steady-state fluxes.

Table 1: Representative AI Tools forkcat/KmPrediction

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Primary Inputs | Predicted Output | Reported Performance (2023-24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Deep Learning (CNN/RNN) | Enzyme Sequence, Substrate SMILES | kcat | Spearman's ρ ~0.6 on broad test set |

| TurNuP | Transformer & GNN | Protein Structure, EC Number | kcat | Mean Squared Error 0.42 (log10 scale) |

| Kcat-Km Pipeline | Ensemble Model (XGBoost) | Sequence, Phylogeny, Substrate PubChem CID | kcat, Km | Km R² ~0.55 on enzymatic assays |

| BrendaMinER | NLP Mining + Imputation | EC Number, Organism, Substrate Text | kcat, Km | Covers > 70,000 enzyme-substrate pairs |

The workflow for identifying candidate rate-limiting enzymes integrates these AI predictions into a systematic computational pipeline.

Diagram Title: Computational Pipeline for Rate-Limiting Enzyme Prediction

Experimental Protocol forIn VivoValidation of Predicted Bottlenecks

Following computational identification, candidate enzymes require experimental validation. The following protocol outlines a standard method using metabolite profiling and gene overexpression.

Protocol: Metabolite Profiling and Overexpression Validation

Objective: To confirm that an enzyme predicted to be rate-limiting indeed controls flux by observing intermediate accumulation and its alleviation upon enzyme overexpression. Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit below. Procedure:

- Strain Construction: Design and clone overexpression cassettes for the gene(s) encoding the predicted rate-limiting enzyme(s) into a plasmid with an inducible promoter (e.g., PTet, PBAD). Transform into the host production strain.

- Cultivation: Inoculate triplicate cultures of both the base strain (control) and the overexpression strain(s) in minimal media with appropriate carbon source and antibiotics.

- Induction & Sampling: At mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.6), induce gene expression with optimal inducer concentration. Take samples at T = 0 (pre-induction), 1h, 2h, and 4h post-induction.

- Quenching & Extraction: Rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., 60% methanol at -40°C). Perform metabolite extraction using a cold methanol:water:chloroform (4:3:2) mixture. Centrifuge and collect the polar phase for LC-MS analysis.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Column: HILIC column (e.g., ZIC-pHILIC).

- Mobile Phase: A = 20mM ammonium carbonate, B = acetonitrile. Gradient from 80% B to 20% B over 15 min.

- MS: Operate in negative/positive electrospray ionization mode with full scan (m/z 70-1000).

- Quantify peak areas for pathway intermediates and final product against authentic standards or internal standards (e.g., 13C-labeled amino acids).

- Data Analysis: Compare the relative abundance of metabolites upstream of the target enzyme between control and overexpression strains. A significant decrease in accumulated intermediates, coupled with an increase in final product titer, confirms the enzyme was rate-limiting.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

| Item | Function in Protocol | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Expression Vector | Allows controlled overexpression of candidate enzyme genes. | pET vectors (IPTG inducible), pBAD (Arabinose inducible) |

| Quenching Solution | Instantly halts cellular metabolism to capture true in vivo metabolite levels. | 60% (v/v) Methanol in water, -40°C |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvent | Efficiently lyses cells and extracts polar metabolites for LC-MS. | Methanol:Water:Chloroform (4:3:2) at -20°C |

| HILIC LC Column | Separates highly polar metabolites not retained on reverse-phase columns. | SeQuant ZIC-pHILIC (Merck) |

| Internal Standards (ISTD) | Corrects for variability in extraction and MS ionization efficiency. | 13C, 15N-labeled cell extract or uniform labeled compounds (Cambridge Isotope Labs) |

| LC-MS/MS System | Quantifies metabolite concentrations with high sensitivity and specificity. | Q-Exactive HF Orbitrap (Thermo) coupled to Vanquish UHPLC |

Case Study: Optimizing the Astaxanthin Pathway inS. cerevisiae

A recent study (2024) applied this paradigm to optimize astaxanthin production. AI-predicted kcat values for the pathway enzymes from β-carotene to astaxanthin (β-carotene hydroxylase CrtZ and ketolase CrtW) were integrated into a genome-scale model of yeast. Flux control analysis predicted CrtW as the primary bottleneck.

Validation Workflow & Results: The experimental workflow followed the protocol above. Results are summarized in Table 3.

Diagram Title: Predicted Bottleneck in Astaxanthin Synthesis

Table 3: Validation Data for Astaxanthin Pathway Engineering

| Strain | Relative Intracellular Zeaxanthin (2h post-induction) | Relative Intracellular Astaxanthin Titer (4h post-induction) | Final Astaxanthin Yield (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Strain (CrtZ + CrtW) | 100% ± 12% (Accumulation) | 100% ± 8% | 45 ± 4 |

| CrtW Overexpression | 58% ± 7% | 185% ± 15% | 83 ± 6 |

| CrtZ Overexpression | 210% ± 18% | 105% ± 9% | 47 ± 5 |

The data confirm the prediction: overexpression of the predicted bottleneck (CrtW) reduced the accumulation of its substrate (zeaxanthin) and increased astaxanthin production, whereas overexpressing the non-rate-limiting enzyme (CrtZ) worsened intermediate accumulation with no product benefit.

The integration of AI-predicted kcat and Km parameters into metabolic models provides a powerful, rational framework for identifying rate-limiting enzymes, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches. Future research within this thesis context will focus on improving the accuracy of Km predictions, developing dynamic multi-scale models, and creating automated platforms that close the loop between prediction, model-based design, and robotic experimental validation. This synergy between AI and metabolic engineering is poised to dramatically accelerate the optimization of microbial cell factories for chemical and therapeutic production.

This technical guide details the application of AI-predicted enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat and Km) within the drug discovery pipeline. Within the broader thesis of AI-based prediction of kcat and Km parameters, these computational advancements provide a quantitative bedrock for rational inhibitor design and systematic off-target profiling. Accurate in silico prediction of enzyme kinetics enables researchers to model biochemical network perturbations and predict compound efficacy and toxicity with greater precision before costly synthesis and wet-lab experimentation.

Core Principles: From Kinetic Parameters to Drug Design

The Michaelis-Menten parameters define enzyme efficiency and substrate affinity:

- kcat (Turnover number): The maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. A high kcat suggests a high-throughput enzyme.

- Km (Michaelis constant): The substrate concentration at half of Vmax. A low Km indicates high substrate affinity.

In drug discovery:

- Inhibitor Design: For competitive inhibitors, the inhibitory constant (Ki) relates to Km under altered apparent substrate affinity. AI-predicted Km values for novel substrates or mutant enzymes help in characterizing binding pockets and designing high-affinity inhibitors.

- Off-Target Prediction: An inhibitor designed for a primary target (Enzyme A) may interact with phylogenetically or structurally similar off-targets (Enzyme B). Comparing predicted kcat/Km values for a compound across the human kinome or proteome allows estimation of its potential to aberrantly modulate non-target pathways, predicting adverse effects.

Quantitative Data: AI-Predicted vs. Experimental Kinetic Parameters

Recent benchmarking studies illustrate the performance of leading AI models (e.g., DLKcat, TurNuP, Cofactor-Attention networks) in predicting enzyme kinetics for drug-relevant targets.

Table 1: Performance of AI Models in Predicting kcat and Km (Data compiled from recent literature)

| AI Model | Key Features | kcat Prediction (Spearman's ρ) | Km Prediction (Spearman's ρ) | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLKcat | Substrate & enzyme sequence, pre-trained language model | 0.65 - 0.72 | 0.58 - 0.63 | Prioritizing high-turnover enzymes as drug targets |

| TurNuP | Phylogenetic & structural features, multi-task learning | 0.70 - 0.75 | 0.60 - 0.68 | Predicting mutant enzyme kinetics in disease states |

| Cofactor-Attention Net | Explicit cofactor & metal ion representation | 0.68 - 0.73 | 0.65 - 0.70 | Designing inhibitors for metalloenzymes |

Table 2: Example Off-Target Risk Assessment Using Predicted kcat/Km

| Target Enzyme (Intended) | Off-Target Enzyme | Predicted ΔΔGbind (kcal/mol) | Predicted Off-Target kcat/Km (% of Target) | Suggested Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR (T790M mutant) | HER2 | -1.2 | 15% | Medium (Functional assay required) |

| Caspase-3 | Caspase-7 | -0.8 | 45% | High (Likely significant inhibition) |

| p38 MAPK | JNK2 | -2.5 | 3% | Low (Minimal predicted activity) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating AI-PredictedKmfor InhibitorKiDetermination

Objective: Experimentally determine the Ki of a novel competitive inhibitor and correlate with AI-predicted Km shifts. Method: Continuous enzyme activity assay (e.g., spectrophotometric).

- Recombinant Protein: Express and purify the target human enzyme (e.g., a kinase).

- AI Prediction: Use a trained model (e.g., TurNuP) to predict the Km for the enzyme's native substrate.

- Assay Setup: Perform the activity assay in a 96-well plate. Vary substrate concentration [S] across wells (e.g., 0.2Km to 5Km). Repeat this series for at least three different concentrations of the inhibitor [I].

- Data Collection: Measure initial velocity (V0) for each condition.

- Analysis: Fit data to the competitive inhibition model: V0 = (Vmax[S]) / (Km(1+[I]/Ki)+[S]). Derive experimental Km and Ki. Compare the observed Km shift with that predicted from the AI-modeled inhibitor binding energy.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Off-Target Screen Using Predicted Specificity Constants

Objective: Identify potential off-targets from a panel of related enzymes using AI-predicted kcat/Km.

- Target Selection: Compile a list of 50-100 human enzymes from the same family (e.g., serine proteases).

- In Silico Screening: For the lead inhibitor (or its approximated pharmacophore), use a docking or affinity prediction pipeline coupled with the kcat/Km prediction model to compute a relative inhibitory score for each enzyme.

- Priority Ranking: Rank off-targets by the predicted (kcat/Km)inhibited / (kcat/Km)uninhibited ratio.

- Experimental Validation: Purchase/produce the top 10 predicted off-targets. Perform a single-point activity assay at a relevant inhibitor concentration (e.g., 1 µM) to confirm inhibition. Full Ki determination follows for confirmed hits.

Diagrams

Workflow: AI kcat/Km Prediction in Drug Discovery

Pathway: Off-Target Effect on PI3K-Akt-mTOR

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Validation Assays

| Item | Function | Example Product/Kit |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Enzyme | The purified drug target for in vitro kinetic studies. | Sino Biological (e.g., Active EGFR kinase), ProQinase. |

| Fluorogenic/Kinase-Glo Substrate | Enables continuous, sensitive measurement of enzyme activity in high-throughput format. | EnzChek (Thermo Fisher), Kinase-Glo Max (Promega). |

| Microplate Reader with Kinetic Capability | Measures absorbance/fluorescence/luminescence over time in 96- or 384-well plates. | BioTek Synergy H1, Tecan Spark. |

| GraphPad Prism | Statistical software for non-linear regression to fit Michaelis-Menten and inhibition models. | GraphPad Prism v10. |

| AlphaFold2 Protein Structure Database | Provides predicted structures for enzymes lacking crystal structures, used as input for some AI models. | EBI AlphaFold Database. |

| Deep-kcat Web Server | Publicly available tool to run pre-trained AI models for kcat prediction. | https://deepkcatapp.denglab.org/ |

Overcoming Hurdles: Best Practices for Optimizing AI Models in Enzyme Kinetics

This technical guide details advanced strategies for managing data challenges inherent in machine learning for biochemistry, specifically within the context of AI-driven prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters (k~cat~ and K~M~). Accurate prediction of these parameters is critical for enzyme engineering, metabolic modeling, and drug discovery, but is hampered by sparse, heterogeneous, and noisy experimental data from diverse sources like BRENDA, SABIO-RK, and published literature.

Core Challenges in Enzyme Kinetic Data

Data Scarcity

Experimental measurement of k~cat~ (turnover number) and K~M~ (Michaelis constant) is low-throughput, expensive, and condition-specific. This results in a patchy matrix where data exists for only a fraction of known enzyme-substrate pairs.

Data Noise and Heterogeneity

Reported values vary due to differences in experimental protocols (pH, temperature, buffer ionic strength), measurement techniques (spectrophotometry, calorimetry), and organism source (wild-type vs. recombinant expression). Data extracted from literature often lacks complete meta-data.

Table 1: Quantifying Scarcity and Noise in Public k~cat~ Data (BRENDA 2024)

| Metric | Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Total unique enzyme entries (EC numbers) | ~8,500 | Broad coverage |

| Entries with reported k~cat~ | ~2,100 (24.7%) | High scarcity |

| Entries with reported K~M~ | ~4,300 (50.6%) | Moderate scarcity |

| Avg. substrates per enzyme (k~cat~) | 1.4 | Limited functional insight |

| Reported range for a single EC (e.g., 1.1.1.1) | k~cat~: 0.5 - 430 s⁻¹ | High experimental noise |

Strategic Framework and Methodologies

Data Curation Pipeline

A robust, rule-based and ML-assisted curation pipeline is essential.

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Stage Data Curation

- Automated Extraction & Normalization: Use NLP tools (e.g., IBM Watson, SciBERT) to extract kinetic values and meta-data from PDFs. Normalize units (k~cat~ to s⁻¹, K~M~ to mM).

- Meta-data Tagging: Tag each entry with: organism, UniProt ID, pH, temperature, publication DOI.