Overcoming Metabolic Burden in Engineered Microbial Strains: Strategies for Robust Bioproduction

Metabolic burden, the physiological stress imposed on cells by engineered pathways, remains a significant bottleneck in developing efficient microbial cell factories for therapeutic and high-value compound production.

Overcoming Metabolic Burden in Engineered Microbial Strains: Strategies for Robust Bioproduction

Abstract

Metabolic burden, the physiological stress imposed on cells by engineered pathways, remains a significant bottleneck in developing efficient microbial cell factories for therapeutic and high-value compound production. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to understand, mitigate, and overcome metabolic burden. We explore the foundational stress mechanisms in model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, detail advanced methodological strategies from pathway balancing to dynamic regulation, present troubleshooting protocols for optimizing strained systems, and discuss validation frameworks for assessing strain performance and industrial viability. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this review aims to equip scientists with practical tools to engineer more robust and productive microbial strains for biomedical applications.

Deconstructing Metabolic Burden: From Cellular Stress Symptoms to Root Causes

Metabolic burden describes the negative physiological impacts on a host cell—such as decreased growth rate, impaired protein synthesis, and genetic instability—that result from engineering efforts to redirect metabolism toward the production of a specific product [1]. In industrial biotechnology, engineering bacterial strains to produce valuable compounds often involves introducing new genetic material and overexpressing pathways. However, the host's metabolism is a highly regulated system evolved for growth and maintenance, and rewiring it disrupts this natural balance [1]. Understanding and mitigating metabolic burden is therefore a critical focus in developing efficient and economically viable microbial cell factories.

Key Stress Symptoms & Mechanisms: FAQ

This section addresses the fundamental questions researchers have about the causes and symptoms of metabolic burden.

FAQ 1: What are the primary observable symptoms of metabolic burden in my culture? You may observe several key stress symptoms in your engineered strains [1]:

- Decreased Growth Rate: A reduction in the maximum specific growth rate (µmax) and a prolonged fermentation cycle.

- Impaired Protein Synthesis: Reduced efficiency in producing functional proteins, both native and heterologous.

- Genetic Instability: Loss of newly acquired characteristics, especially over long fermentation runs, often due to plasmid loss or mutations.

- Aberrant Cell Morphology: Cells may show an abnormal size or shape. These symptoms collectively lead to lower production titers and reduced process efficiency on an industrial scale [1].

FAQ 2: What are the core metabolic triggers behind these symptoms? The core triggers are often linked to the (over)expression of heterologous proteins, which creates multiple interconnected stresses [1]:

- Resource Depletion: High-level protein synthesis drains the cellular pools of amino acids and energy molecules (ATP, NADPH).

- Charged tRNA Depletion: Expressing a heterologous protein with a codon usage that differs from the host's can lead to over-use of rare codons. This depletes the corresponding charged tRNAs, causing ribosomes to stall [1].

- Protein Misfolding: Stalled ribosomes and the removal of native rare-codon regions (via codon optimization) that provide time for correct folding can both increase the production of misfolded proteins [1].

- Activation of Stress Responses: The depletion of amino acids and charged tRNAs, along with an accumulation of misfolded proteins, triggers global stress responses like the stringent response (via alarmones like ppGpp) and the heat shock response [1].

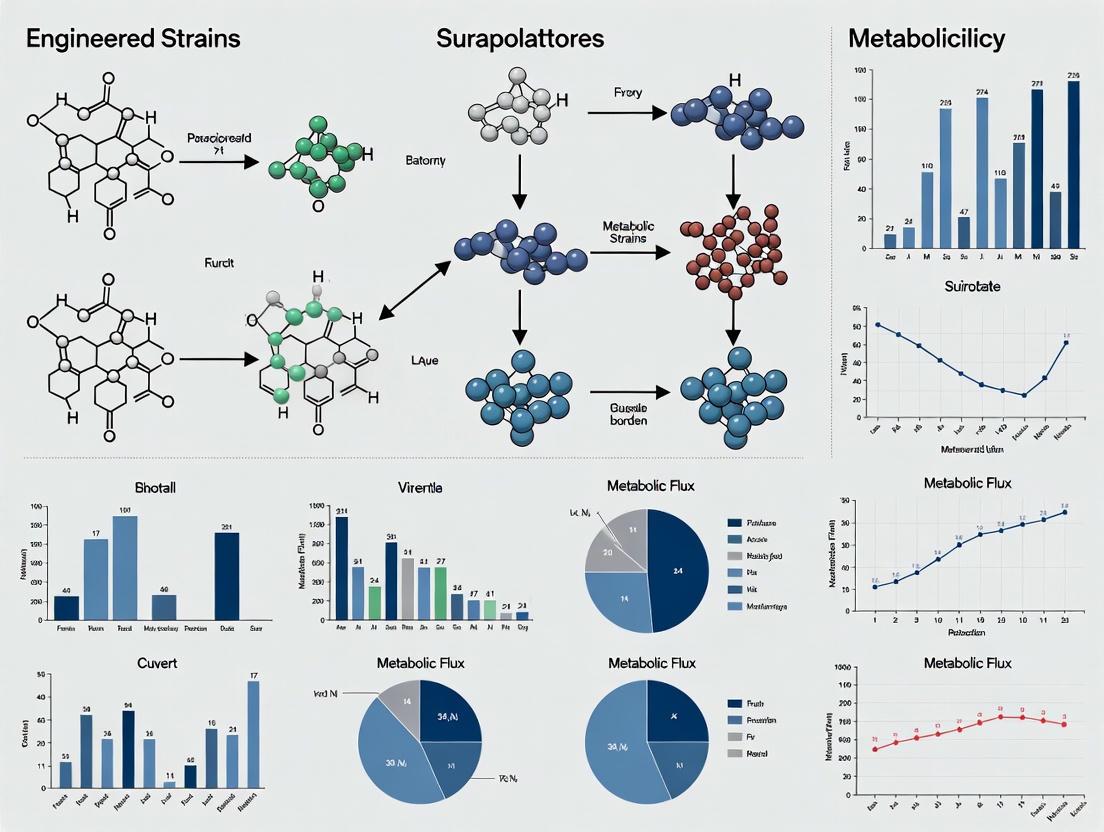

The diagram below illustrates how these triggers and mechanisms are interconnected, leading to the observed stress symptoms.

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosis & Mitigation

This guide provides a structured approach to diagnosing and solving common problems related to metabolic burden.

Problem: My recombinant strain is growing very slowly after induction.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| High metabolic load from protein production. | Measure growth rate (OD600) and plasmid stability pre- and post-induction [2]. Run SDS-PAGE to check recombinant protein expression levels [2]. | Use a weaker or inducible promoter. Optimize induction timing (e.g., induce at mid-log phase) [2]. Reduce inducer concentration. |

| Nutrient depletion or toxic byproduct accumulation. | Analyze media for substrate consumption (e.g., glucose). Test for accumulation of organic acids or other inhibitors. | Switch to a richer growth medium (e.g., from M9 to LB) [2]. Use fed-batch cultivation to avoid nutrient depletion. Engineer the host to be more robust. |

| Activation of the stringent response. | Quantify intracellular ppGpp levels. Use RNA-seq to check for upregulation of stress response genes. | Use a host with a relA mutation to disable the stringent response. Optimize the heterologous gene's codon usage without removing all rare codons crucial for folding [1]. |

Problem: The yield of my recombinant protein is low, despite high cell density.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Codon usage bias leading to translation inefficiency. | Analyze the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) of your gene sequence. Check for ribosomal stalling. | Perform partial codon optimization, avoiding regions that may be critical for protein folding [1]. Use a plasmid that supplements rare tRNAs. |

| Protein misfolding and aggregation. | Analyze the protein solubility fraction vs. inclusion bodies. Use Western blot to detect truncated or degraded products. | Lower the cultivation temperature post-induction. Co-express relevant chaperones (e.g., DnaK/DnaJ). Use a fusion tag to enhance solubility. |

| Genetic instability or plasmid loss. | Plate cells on selective and non-selective media to check for plasmid retention. Check plasmid integrity via restriction digest. | Increase antibiotic concentration (if applicable). Use a stable, low-copy-number plasmid. Implement genomic integration of the gene of interest. |

Problem: My culture shows high phenotypic heterogeneity or loses the production trait over time.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic instability due to high metabolic burden. | Perform a plasmid stability assay over multiple generations. Sequence the production plasmid from evolved populations. | Switch to a more stable expression system (e.g., genomic integration). Use dynamic regulation to delay production until after a growth phase [3]. |

| Toxicity of the pathway intermediate or final product. | Measure growth inhibition in the presence of the product/intermediate. Use biosensors to monitor intracellular metabolite levels [4]. | Engineer export systems for the product. Evolve the host for higher product tolerance. Re-engineer the pathway to avoid toxic intermediates. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

This section provides quantitative data and a detailed protocol to help you plan and analyze your experiments.

Quantitative Impact of Metabolic Burden

The table below summarizes experimental data demonstrating how different engineering decisions impact growth and production, highlighting the trade-offs caused by metabolic burden [2].

| Host Strain | Growth Medium | Induction Point (OD600) | Maximum Specific Growth Rate, µmax (h⁻¹) | Recombinant Protein Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Early-log (0.1) | Lowest | Early expression, but diminished in late phase |

| E. coli M15 | Defined (M9) | Mid-log (0.6) | Higher than early induction | Retained expression in late growth phase |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Early-log (0.1) | High | Early expression, but diminished in late phase |

| E. coli M15 | Complex (LB) | Mid-log (0.6) | Highest | Strong, sustained expression |

| E. coli DH5α | Defined (M9) | Mid-log (0.6) | Moderate | Lower yield compared to M15 strain |

Detailed Protocol: Analyzing Host Response via Proteomics

This protocol outlines a method to systematically investigate the impact of recombinant protein production on your host strain, helping to identify the root causes of metabolic burden [2].

Goal: To understand the cellular dynamics and metabolic perturbations in engineered E. coli strains under different production conditions.

Materials:

- Strains: Your recombinant E. coli strain and an empty-vector control strain.

- Media: LB and a defined minimal medium (e.g., M9).

- Reagents: IPTG (or relevant inducer), Lysis buffer, Protease inhibitors, SDS-PAGE reagents.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, Shaking incubator, Centrifuge, SDS-PAGE apparatus, Mass Spectrometer for proteomic analysis (optional).

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Inoculate your test and control strains in both LB and M9 media. For each condition, plan to induce protein expression at two different growth phases: early-log phase (OD600 ~0.1) and mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6).

- Cultivation and Monitoring:

- Inoculate primary cultures and grow overnight.

- Dilute secondary cultures and start monitoring optical density (OD600) to generate growth curves.

- Calculate the maximum specific growth rate (µmax) for each condition.

- Induction and Sampling:

- At the target OD600, induce the culture with an optimized concentration of IPTG.

- Collect samples at key time points: e.g., at mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.8) and late-log phase (12 hours post-inoculation).

- Centrifuge samples to harvest cells. Wash cell pellets with PBS and store at -80°C.

- Protein Extraction and Analysis:

- Lyse cell pellets using a method like sonication in a suitable lysis buffer.

- Determine the total protein concentration of each sample.

- Load equal amounts of protein (e.g., 50 µg) onto an SDS-PAGE gel to check the recombinant protein expression profile and purity.

- Proteomic Analysis (Label-Free Quantification):

- Digest the protein samples into peptides.

- Analyze the peptides using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Use bioinformatics tools to identify and quantify proteins across samples. Compare the proteomes of your production strain to the control strain under identical conditions.

- Data Interpretation: Focus on significant changes in the abundance of proteins involved in:

- Transcription and translation machinery

- Chaperones and proteases (heat shock response)

- Amino acid biosynthesis

- Central carbon metabolism (Glycolysis, TCA cycle)

- Stress response proteins

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and tools used in the field to study and alleviate metabolic burden.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Metabolic Burden Research |

|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Genes synthesized with host-preferred codons to improve translation speed and accuracy. Note: Full optimization can disrupt protein folding; consider partial optimization [1]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Plasmids for co-expressing chaperones like DnaK/DnaJ or GroEL/GroES to assist with proper folding of recombinant proteins and reduce aggregation [1]. |

| Strain Engineering Tools (CRISPR) | For precise genomic integration of pathways, eliminating the need for high-copy plasmids and thus reducing the genetic load on the host [3]. |

| Biosensors | Genetically encoded devices (e.g., transcription-factor based) that detect metabolite levels, enabling high-throughput screening of optimized strains or dynamic pathway regulation [4]. |

| Tunerable Promoters | Inducible promoters (e.g., pBAD, T7 lac) that allow fine control over the strength and timing of gene expression, preventing premature metabolic overload [2]. |

| ppGpp-Null (ΔrelA) Strains | Engineered host strains that cannot initiate the stringent response, useful for decoupling growth from production stress, though this can have complex consequences [1]. |

Key Signaling Pathways

A deep understanding of the stringent response is crucial for diagnosing metabolic burden. This pathway is a primary reaction to the burden imposed by heterologous protein production.

FAQs: Understanding Metabolic Burden

What is "metabolic burden" and what are its common symptoms in engineered strains? "Metabolic burden" refers to the stress state of a microbial host caused by metabolic engineering strategies, such as the (over)expression of heterologous proteins. This burden diverts energy and resources from native cellular processes, leading to observable stress symptoms [1].

Common symptoms include:

- Decreased growth rate and final biomass

- Impaired protein synthesis

- Genetic instability (e.g., plasmid loss)

- Aberrant cell size and morphology

- Low production titers, especially in long fermentation runs [1]

What are the primary triggers of resource depletion that activate stress responses? The primary triggers are often linked to the intense resource demand of producing non-native proteins and metabolites. Key triggers include [1]:

- Depletion of Amino Acids and Charged tRNAs: High expression levels drain the cellular pool of amino acids and their corresponding charged tRNAs.

- Codon Usage Mismatch: Heterologous genes may over-use rare codons for which the host has limited cognate tRNAs, causing ribosome stalling.

- Misfolded Proteins: Rapid translation or improper folding leads to an accumulation of misfolded proteins, overwhelming the quality control systems.

How does the bacterial stringent response relate to metabolic burden? The stringent response is a primary stress mechanism activated by metabolic burden. It is triggered by the presence of uncharged tRNAs in the ribosomal A-site, a direct consequence of amino acid or charged tRNA depletion. This leads to the accumulation of alarmones (ppGpp), which dramatically shift cellular metabolism away from growth and ribosome synthesis towards amino acid biosynthesis, imposing a severe growth penalty [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Decreased Growth Rate in Production Strain

A significant reduction in the growth rate of your engineered strain compared to the wild-type is a classic sign of high metabolic burden.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

- Confirm the Observation: Repeat the growth curve experiment to ensure the result is reproducible and not an artifact [5].

- Check Your Controls:

- Compare your production strain to an empty-vector control, not just the wild-type. This isolates the effect of the genetic construct from the background strain [5].

- Include a positive control (e.g., a strain with a known, well-tolerated construct) to benchmark performance.

- Inspect Genetic Stability: Plate cultures on selective and non-selective media to check for plasmid loss. A high rate of plasmid loss indicates the genetic load is unsustainable [1].

- Systematically Reduce Burden: Test a series of constructs to pinpoint the source of burden [5]:

- Test a Weaker Promoter: Reduce the transcription level of your heterologous pathway.

- Modulate Gene Copy Number: If using a multi-copy plasmid, switch to a low-copy or genomic integration system.

- Simplify the Pathway: If expressing a multi-gene pathway, determine if all genes are essential at high levels.

Problem: Low Protein Expression Titer

The expression titer of your target heterologous protein is lower than expected, despite high initial cell density.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

- Verify Protein Function: Ensure the protein is being expressed in a functional, soluble form and not as inclusion bodies. Check activity with a functional assay.

- Analyze mRNA and Protein Levels:

- Use qPCR to check mRNA levels. Low mRNA suggests transcription issues (promoter strength, mRNA instability).

- Use Western Blot to detect the protein. A strong mRNA signal with a weak protein signal indicates a translation problem [6].

- Investigate Translation Bottlenecks:

- Check for Codon Bias: Analyze the gene sequence for clusters of rare codons. Consider partial codon optimization of these regions, being cautious to maintain any natural pause sites needed for folding [1].

- Ensure Adequate Charged tRNA Levels: In cases of severe codon bias or high expression, consider co-expressing a plasmid encoding rare tRNAs.

- Assess Host Health: Monitor the induction kinetics. If the titer peaks early and then drops, the host may be experiencing severe stress or cell lysis. Harvest earlier or use a milder induction strategy.

Signaling Pathways and Stress Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the core cellular triggers and activated stress responses linked to metabolic burden.

Stress Response Network: This workflow maps the consequences of heterologous protein expression in a model organism like E. coli. Key triggers (white nodes) activate specific stress mechanisms (colored nodes), which collectively lead to the observed symptoms of metabolic burden (gray nodes) [1].

Quantitative Data: Stress Symptoms & Triggers

The table below summarizes the quantitative and qualitative data linking specific stress triggers to their outcomes.

Table 1: Metabolic Burden Triggers and Associated Stress Symptoms

| Trigger Category | Specific Trigger | Activated Stress Response | Observed Stress Symptom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Depletion | Depletion of amino acid pools [1] | Stringent Response, Nutrient Starvation Response [1] | Decreased growth rate, Impaired protein synthesis [1] |

| Translation Issues | Accumulation of uncharged tRNAs in A-site [1] | Stringent Response (ppGpp synthesis) [1] | Growth arrest, Reduced ribosome synthesis [1] |

| Translation Issues | Over-use of rare codons / Codon bias [1] | Ribosome stalling, Translation errors [1] | Increased misfolded proteins, Low functional protein titer [1] |

| Protein Damage | Accumulation of misfolded proteins [1] | Heat Shock Response (e.g., DnaK/DnaJ induction) [1] | Chaperone overload, Impaired cellular function [1] |

| Genetic Load | High-level plasmid maintenance & replication [1] | Continuous resource drain on energy and precursors [1] | Genetic instability (plasmid loss), Aberrant cell size [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments and broader metabolic engineering field, with explanations of their function.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Synthetic genes where codons are replaced with host-preferred synonyms to enhance translation speed and efficiency, though careful design is needed to avoid disrupting protein folding [1]. |

| tRNA Supplement Plasmids | Plasmids encoding genes for rare tRNAs; co-expressed to alleviate ribosome stalling caused by codon mismatch in heterologous gene expression [1]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Systems for co-expressing chaperone proteins (e.g., DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE, GroEL-GroES) to assist with the folding of heterologous proteins and reduce aggregation [1]. |

| Promoter Libraries | A collection of genetic constructs with varying promoter strengths, allowing fine-tuning of gene expression levels to balance metabolic flux and minimize burden [1]. |

| Protease-Deficient Strains | Host strains (e.g., E. coli BL21) with mutations in Lon and OmpT proteases to reduce degradation of recombinant proteins [1]. |

| Antibodies for Western Blot | Used to detect and confirm the expression and size of specific heterologous proteins, helping to diagnose translation issues or degradation [6]. |

| ppGpp Detection Kits | Assays (e.g., HPLC, enzymatic) to measure intracellular levels of the (p)ppGpp alarmones, providing a direct readout of stringent response activation [1]. |

In metabolic engineering, rewiring a host's metabolism to produce target compounds often triggers intrinsic stress response mechanisms. Two of the most critical are the stringent response and the heat shock response. These conserved systems activate when engineered strains experience stress from recombinant protein production, nutrient limitation, or resource diversion, leading to a phenomenon known as "metabolic burden" [1]. This burden manifests as reduced growth rates, impaired protein synthesis, and decreased productivity, ultimately undermining bioprocess efficiency [1] [2]. Understanding and troubleshooting these stress pathways is therefore essential for developing robust microbial cell factories.

This guide provides a technical resource for researchers facing experimental challenges related to these stress responses, with targeted troubleshooting advice, detailed protocols, and visual aids to diagnose and overcome these issues within the context of metabolic engineering.

Understanding the Key Stress Responses

The Stringent Response

The stringent response is a highly conserved bacterial stress response to nutrient-limiting conditions, particularly amino acid starvation [7] [8]. It is characterized by the rapid synthesis of alarmone molecules, guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp), collectively known as (p)ppGpp [8].

- Primary Trigger: Nutrient starvation (amino acids, fatty acids, nitrogen, iron) [7] [8].

- Key Actors: RSH enzymes (RelA and SpoT in E. coli). RelA is primarily activated by uncharged tRNA in the ribosomal A-site during amino acid starvation. SpoT mainly hydrolyzes (p)ppGpp but can also synthesize it under other stresses [7] [8] [1].

- Cellular Impact: (p)ppGpp dramatically reprograms cellular metabolism by binding to RNA polymerase and other targets. This shifts resources away from growth and division (inhibiting rRNA/tRNA synthesis, replication, and ribosome biogenesis) and toward amino acid synthesis and stress survival [7] [8].

The Heat Shock Response

The heat shock response (HSR) is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism that protects cells from proteotoxic stress caused by elevated temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals [9] [10]. Its main function is to maintain proteostasis (protein homeostasis) by preventing the accumulation of misfolded proteins.

- Primary Trigger: Accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins [9] [10].

- Key Actors: Heat shock factors (HSFs) and heat shock proteins (HSPs). In vertebrates, HSF1 is the master regulator. It trimerizes upon stress, translocates to the nucleus, and binds to heat shock elements (HSEs) in the promoters of heat shock protein (HSP) genes [9] [10].

- Cellular Impact: Induced synthesis of molecular chaperones (e.g., HSP70, HSP90, HSP60) that facilitate the refolding of misfolded proteins or target irreversibly damaged proteins for degradation [10].

Interconnection and Relation to Metabolic Burden

In metabolic engineering, these pathways are often unintentionally activated. The high-level expression of recombinant proteins can drain amino acid pools and lead to uncharged tRNAs, activating the stringent response [1]. Simultaneously, the rapid synthesis of heterologous proteins or the inherent instability of some recombinant proteins can lead to misfolding, activating the heat shock response [1] [2]. These responses compound the "metabolic burden," diverting energy and resources away from the intended production goal and toward cellular survival, thereby reducing titers, yields, and productivity [1] [2].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Stringent and Heat Shock Responses

| Feature | Stringent Response | Heat Shock Response |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Trigger | Nutrient starvation (e.g., amino acids) [7] [8] | Proteotoxic stress (e.g., heat, misfolded proteins) [9] [10] |

| Key Signaling Molecule | Alarmones (p)ppGpp [7] [8] | Heat Shock Factors (HSFs, e.g., HSF1) [9] [10] |

| Main Effector Molecules | RNA polymerase, metabolic enzymes, GTPases [7] [8] | Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs: HSP70, HSP90, HSP60) [9] [10] |

| Primary Cellular Outcome | Halts growth; reprograms transcription for survival [7] [8] | Increases chaperones; refolds or degrades damaged proteins [9] [10] |

| Key inducible E. coli Genes | relA, spoT |

rpoH (encodes σ³²), dnaK, groEL [10] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ 1: My engineeredE. colistrain shows severely reduced growth after induction of a recombinant pathway. How can I determine if the stringent response is the cause?

Answer: A sudden drop in growth rate post-induction is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, often linked to stringent response activation. Here is a systematic troubleshooting approach, adapted from general scientific troubleshooting principles [11].

Step 1: Identify the Problem. Define the observation precisely: "A reduction in growth rate (from X to Y) occurs Z hours after induction of the pathway."

Step 2: List Possible Causes.

- Stringent Response Activation: Amino acid depletion or uncharged tRNAs due to high metabolic demand [1].

- Toxicity: The product or an intermediate of the engineered pathway is toxic to the cell [1].

- Resource Depletion: General depletion of energy (ATP) or cofactors.

- Heat Shock Response Activation: Misfolding of recombinant proteins [2].

Step 3: Collect Data.

- Run Controls: Compare growth with an empty-vector control strain under identical induction conditions.

- Analyze Metabolites: Use HPLC/MS to check for amino acid depletion in the medium.

- Monitor Stress Markers: Use qPCR to measure transcript levels of key stress genes. A >5-fold increase in

relAtranscription or known (p)ppGpp-regulated genes is a strong indicator [1] [2].

Step 4: Eliminate Explanations & Check with Experimentation.

- Test Different Induction Conditions: Reduce the inducer concentration or induce at a higher cell density (mid-log phase) to lessen the sudden metabolic burden. Induction at the mid-log phase has been shown to help maintain growth rates and protein expression [2].

- Supplement Media: Add casamino acids or a specific, potentially depleted amino acid to the culture medium at induction. If growth recovers, amino acid starvation is likely the trigger.

Step 5: Identify the Cause. Based on the experimental data, you can confirm or rule out the stringent response. For example, if growth normalizes in the amino acid-supplemented medium and

relAexpression is high, you have identified the root cause.

FAQ 2: I suspect recombinant protein misfolding is triggering the heat shock response and lowering my yields. What can I do?

Answer: Protein misfolding is a common issue in heterologous expression. The following protocol helps diagnose and address HSR-related failures.

Step 1: Verify Misfolding.

- Check for Insolubility: Perform cell lysis and fractionation via centrifugation. Analyze the soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions by SDS-PAGE. A dominant band in the pellet indicates aggregation.

- Monitor HSR Activation: Use a reporter plasmid with a GFP gene under the control of a heat shock promoter (e.g.,

dnaKp) or measurerpoH(σ³²) transcript levels by qPCR [12].

Step 2: List Causes of Misfolding.

- Codon Usage: The gene contains codons that are rare in your expression host, causing translational stalling and misfolding [1].

- Lack of Proper Chaperones: The host's native chaperone system is overwhelmed or insufficient for your specific protein.

- Burden from High Expression: The sheer rate of synthesis outstrips the capacity of the folding machinery [2].

- Sub-optimal Growth Conditions: Temperature, pH, or media composition are not conducive to proper folding.

Step 3: Experimentation and Solutions.

- Reduce Expression Burden: Lower the induction temperature (e.g., to 25-30°C) and/or use a weaker promoter. This slows down synthesis, giving chaperones more time to act [2].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express plasmid-borne chaperone systems (e.g., GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE) to augment the host's folding capacity.

- Codon Optimization: Optimize the gene sequence to use the host's preferred codons, but be cautious of removing rare codons that may be strategically important for correct co-translational folding [1].

FAQ 3: My fermentation data is variable and I observe high cell-to-cell heterogeneity. Which stress response is likely involved and how can I stabilize production?

Answer: Population heterogeneity in bioreactors is a classic sign of stress and can be caused by both stringent and heat shock responses. The variability often arises because some cells in the population experience stress more acutely than others (e.g., due to uneven nutrient distribution or stochastic gene expression) [1].

Diagnosis:

- Use flow cytometry with stress-specific fluorescent reporters (e.g., for (p)ppGpp or σ³²) to quantify the degree of heterogeneity and identify which sub-populations are stressed.

- Analyze cell size distributions via microscopy or a particle analyzer. Aberrant cell sizes (filamentation) can be linked to stress responses [1].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Dynamic Process Control: Implement fed-batch strategies to avoid nutrient spikes and starvation. Maintain a steady, growth-limiting feed rate to prevent the boom-bust cycles that trigger the stringent response.

- Use Weaker, Constitutive Promoters: Instead of strong inducible promoters, consider using well-tuned constitutive promoters that place less sudden burden on the cell, thereby reducing stress response induction.

- Strain Engineering: Knock out

relAto ablate the stringent response, but be cautious as this can make cells fragile. A better approach is to engineer promoters for your pathway that are less sensitive to (p)ppGpp repression.

Experimental Protocols for Stress Response Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying Stringent Response Activation via RT-qPCR

Objective: To measure the transcriptional activity of the stringent response in engineered versus control strains.

Materials:

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., TRIzol)

- DNase I

- cDNA synthesis kit

- SYBR Green qPCR master mix

- Primers for

relA,spoT,spot 42(a known (p)ppGpp-regulated gene), and a housekeeping gene (e.g.,rpoD).

Method:

- Sample Collection: Collect cell samples from the bioreactor or culture flasks at specific time points (pre-induction, and 1, 2, and 4 hours post-induction). Immediately stabilize RNA with a suitable reagent.

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA following the kit protocol. Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA using a reverse transcription kit.

- qPCR Setup: Prepare reactions in triplicate for each gene of interest and the housekeeping gene. A sample setup for a 20 µL reaction is below.

- Data Analysis: Calculate fold-change using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method, comparing induced samples to the pre-induction control.

Table 2: qPCR Reaction Setup

| Component | Volume | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green Master Mix (2X) | 10 µL | 1X |

| Forward Primer (10 µM) | 0.8 µL | 400 nM |

| Reverse Primer (10 µM) | 0.8 µL | 400 nM |

| cDNA template | 2 µL | ~10 ng |

| Nuclease-free H₂O | 6.4 µL | - |

| Total Volume | 20 µL |

Protocol 2: Analyzing Cellular Resource Allocation via Proteomics

Objective: To understand the global impact of recombinant protein production on cellular machinery and stress responses, as demonstrated in [2].

Materials:

- Luria-Bertani (LB) and defined (e.g., M9) media.

- Lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, pH 8.0).

- Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit for protein quantification.

- Equipment for SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry.

Method:

- Strain and Culture Conditions: Use two different E. coli host strains (e.g., M15 and DH5α) harboring your expression plasmid and an empty-vector control [2].

- Induction Strategy: Induce recombinant protein expression at different growth phases (e.g., early-log phase OD₆₀₀ ~0.1 and mid-log phase OD₆₀₀ ~0.6) in both complex (LB) and defined (M9) media [2].

- Sample Preparation: Harvest cells at mid-log and late-log phases. Lyse cells using a combination of chemical and mechanical methods.

- Protein Quantification and Analysis: Determine total protein concentration with a BCA assay. Analyze equal protein amounts by SDS-PAGE for a quick expression check.

- Proteomic Analysis: For a deeper dive, submit samples for label-free quantitative (LFQ) proteomics. This will identify significant changes in the abundance of proteins involved in transcription, translation, fatty acid biosynthesis, and stress responses (e.g., RpoH, GroEL) between your test and control conditions [2].

Pathway Diagrams and Visual Guides

Diagram 1: The Stringent Response Signaling Pathway in E. coli

This diagram illustrates the activation mechanism and major regulatory targets of the stringent response.

Diagram 2: The Heat Shock Response and Protein Homeostasis

This diagram shows the activation cycle of HSF1 and the roles of major HSPs in maintaining proteostasis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Stress Response Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LB & M9 Media | Provides complex and defined growth conditions for comparing metabolic burden and stress. | Identifying if stress is nutrient-specific; M9 media often shows greater burden impact [2]. |

| Different E. coli Strains (e.g., M15, DH5α, BL21) | Hosts with varying genetic backgrounds and metabolic capacities. | Screening for optimal recombinant protein expression with minimal stress induction [2]. |

| qPCR Kits and Primers | Quantifies transcriptional changes in stress-related genes (e.g., relA, rpoH, dnaK). |

Directly measuring the activation level of the stringent or heat shock response [1]. |

| SDS-PAGE Equipment | Analyzes protein expression, solubility, and aggregation. | Quick diagnostic for recombinant protein misfolding and inclusion body formation. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits (e.g., GroEL/ES, DnaK/J) | Co-expression vectors to augment the host's protein folding machinery. | Rescuing the expression of aggregation-prone recombinant proteins [1]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Visualizes and quantifies stress activation in single cells via FACS or microscopy. | Monitoring population heterogeneity and real-time stress response dynamics [12]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Core Challenges and Solutions

This guide addresses the most common issues encountered during heterologous protein expression, framed within the context of mitigating metabolic burden in engineered strains.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Heterologous Protein Expression Challenges

| Observed Problem | Potential Primary Cause | Underlying Stress Mechanism | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Protein Yield | Suboptimal codon usage leading to inefficient translation [13] [14] | Depletion of charged tRNAs for rare codons; activation of the stringent response [1] | Implement codon optimization (see FAQ 1); consider tRNA co-expression plasmids [14] |

| Protein Misfolding & Aggregation | Translation proceeding too rapidly due to codon optimization, not allowing time for co-translational folding [1] | Accumulation of misfolded proteins; saturation of chaperone systems (e.g., DnaK/J) [1] [15] | Use codon harmonization instead of full optimization; co-express relevant molecular chaperones [13] [16] |

| Reduced Host Cell Growth & Viability | High metabolic burden from resource drain (amino acids, ATP) and protein toxicity [17] [1] | Global stress responses (stringent, heat shock); impaired synthesis of native proteins [1] | Use inducible promoters; engineer host for robustness; optimize cultivation media [13] [17] |

| Incorrect Protein Function | Translation errors (mis-incorporation, frameshifts) due to rare codons and uncharged tRNAs in the A-site [1] [14] | Amino acid starvation leading to increased error rate; production of non-functional polypeptide chains [1] | Ensure amino acid supplementation; codon-optimize gene sequence [1] [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the difference between common codon optimization strategies, and which should I choose?

The choice of strategy significantly impacts protein expression and host health. The three primary methods are [13]:

- Use Best Codon (UBC): Replaces every codon with the single most frequent synonymous codon for the host. This can maximize speed but may cause tRNA depletion and protein misfolding [18] [1].

- Match Codon Usage (MCU): Adjusts the codon sequence to match the natural codon frequency distribution of the host. This avoids extreme tRNA demand and can preserve regions of slower translation important for folding [13] [18].

- Harmonize Relative Codon Adaptiveness (HRCA): Aims to match the codon usage bias of the source organism but adjusted for the new host. This is thought to best preserve the natural rhythm of translation [13].

Table 2: Performance of Different Codon Optimization Strategies in Various Hosts

| Optimization Strategy | Reported Effect on Protein Level | Reported Impact on Host Metabolism | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use Best Codon (UBC) | >50-fold increase observed in engineered PKS [13] | Can lead to severe metabolic burden and tRNA imbalance [18] [1] | Initial high-level screening when protein simplicity is high |

| Match Codon Usage (MCU) | High-level, reliable expression; up to 10-15 fold increases reported [13] [14] | Lower burden than UBC; more balanced tRNA usage [19] | General-purpose, robust expression for most proteins |

| Codon Harmonization (HRCA) | Can improve functional yields for complex proteins [13] | Theoretically minimizes disruption to the host's translation machinery | Large, complex proteins prone to aggregation |

FAQ 2: How does heterologous expression lead to tRNA depletion and what are the consequences?

Expression of a heterologous gene with a codon usage bias different from the host's can lead to the overuse of certain codons [14]. The tRNAs corresponding to these overused codons become scarce, leading to their depletion in the charged (aminoacyl-) state [19] [1]. Consequences include [1]:

- Ribosome Stalling: Ribosomes pause at rare codons, waiting for the correct charged tRNA.

- Activation of the Stringent Response: The presence of uncharged tRNAs in the ribosomal A-site triggers the synthesis of the alarmone (p)ppGpp, a global regulator that drastically shifts cellular metabolism away from growth and inhibits the synthesis of rRNA and tRNA [1].

- Translation Errors: Prolonged stalling can lead to frameshifts, amino acid misincorporation, and premature translation termination, increasing the load of misfolded and non-functional proteins [1].

FAQ 3: My protein is produced in high amounts but is inactive. Could misfolding be the issue?

Yes, high production does not guarantee proper folding. Misfolding can occur if the protein fails to reach its native conformation, often aggregating into insoluble inclusion bodies or non-functional soluble oligomers [15]. This is particularly common when using strong, non-regulated promoters or codon-optimized sequences that remove natural pauses, not allowing sufficient time for domain folding [1]. Strategies to address this include [16] [1]:

- Lowering Expression Temperature: Slows down translation, providing more time for folding.

- Using Weaker or Inducible Promoters: Reduces the initial burst of synthesis.

- Co-expressing Chaperones: Proteins like DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE or GroEL-GroES can assist in the folding process [1].

- Applying Codon Harmonization: Preserves regions of slower translation that may be critical for co-translational folding.

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Codon Usage-Related Issues

Objective: To determine if poor protein expression is linked to codon adaptation and tRNA demand.

Materials:

- Plasmid containing the gene of interest (GOI) with its native codon usage.

- Codon-optimized version of the GOI (e.g., using MCU strategy).

- Appropriate expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21).

- Equipment for SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting or activity assays.

Methodology:

- Clone both the native and codon-optimized genes into identical expression vectors.

- Transform both constructs into your expression host.

- Induce expression under standard conditions in parallel cultures.

- Analyze the outcome:

- Measure cell growth (OD600) over time to assess metabolic burden.

- Analyze total protein yield via SDS-PAGE.

- Quantify soluble vs. insoluble protein fractionation.

- Measure specific activity of the recombinant protein, if possible.

- Interpretation: A significant increase in yield and/or activity with the optimized construct, potentially accompanied by less growth inhibition, indicates that native codon usage was a major limiting factor [13] [14].

Protocol 2: Assessing and Engineering tRNA Availability

Objective: To directly investigate the role of tRNA abundance and engineer a host with tailored tRNA levels.

Materials:

- Computer-Aided Design (CAD) tool for simulating translation (e.g., colloidal dynamics simulator) [19].

- Method for direct RNA synthesis (e.g., Tunable Implementation of Nucleic Acids - TINA) [19].

- In vitro protein synthesis system (e.g., PURE system) [19].

Methodology:

- Computational Design:

- Use a CAD tool (e.g., CD-CAD) to input your GOI sequence and the host's transcriptome-wide codon usage.

- The tool will simulate translation dynamics and output an optimized tRNA abundance distribution designed to either maximize or minimize translation speed for your goal [19].

- System Assembly:

- Use RNA synthesis (TINA) to create a set of synthetic tRNAs matching the computationally designed abundance profile [19].

- In vitro Testing:

- Assemble a defined protein synthesis system (like PURE) incorporating your custom tRNA pool.

- Express your GOI in this system and compare the protein synthesis rate and yield to a control system with a wild-type tRNA distribution [19].

- Application: This first-principles approach allows for the rational design of cellular translation machinery to relieve tRNA-related bottlenecks, directly addressing a key component of metabolic burden [19].

Visualizing the Stress Pathways and Solutions

This diagram illustrates the interconnected cascade of events triggered by heterologous protein expression, from initial codon usage to the activation of global stress responses.

Figure 1: The Interplay of Codon Usage, Stress Responses, and Metabolic Burden. This map shows how heterologous expression triggers a cascade of stress events and potential solutions (dashed lines) to mitigate them.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Addressing the Heterologous Protein Challenge

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| BaseBuddy Online Tool | A free, transparent, and highly customizable web tool for codon optimization using up-to-date codon usage tables [13]. | Implementing Match Codon Usage (MCU) or Harmonization (HRCA) strategies for initial gene design. |

| DNA Chisel | An open-source Python toolkit that offers fine control over codon optimization algorithms and other sequence engineering constraints [13]. | For advanced, programmable codon optimization and sequence design. |

| Specialized tRNA Plasmids | Plasmids encoding clusters of tRNAs for codons that are rare in the expression host (e.g., AGA, AGG Arg codons in E. coli) [14]. | Co-expression to supplement the host's tRNA pool and relieve depletion for specific rare codons without full gene resynthesis. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Vectors for co-expressing key chaperone systems like GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE [16]. | To assist with protein folding in vivo, reducing aggregation and increasing soluble, functional yield. |

| PURE System | A reconstituted in vitro protein synthesis system composed of purified components, allowing for precise manipulation of tRNA abundances and other factors [19]. | For systematically studying the direct effects of tRNA abundance on translation efficiency and for prototyping custom tRNA mixes. |

| Colloidal Dynamics CAD (CD-CAD) | A computer-aided design tool using first-principles physics modeling to simulate and optimize tRNA abundance distributions for a desired protein synthesis rate [19]. | To rationally design a host's tRNA profile to minimize bottlenecks for a specific target gene or pathway. |

In the field of metabolic engineering and recombinant strain development, distinguishing between metabolic burden and metabolomic alterations is crucial for optimizing bioproduction processes. Metabolic burden refers to the stress symptoms and growth defects observed when host cells are engineered to produce heterologous proteins or products, redirecting resources away from regular cellular activities [20] [1]. In contrast, metabolomic alterations represent changes in the complete set of small-molecule metabolites within a biological system, which may occur without immediately apparent physiological impacts [20] [21]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to help researchers identify, distinguish, and address these challenges in their work with engineered microbial strains.

FAQs: Understanding Core Concepts

1. What is the fundamental difference between metabolic burden and metabolomic alterations?

Metabolic burden manifests as observable stress symptoms such as decreased growth rate, impaired protein synthesis, genetic instability, and aberrant cell size resulting from the redirection of cellular resources toward recombinant protein production [1]. Metabolomic alterations, however, refer specifically to changes in the molecular fingerprint of a cell—the comprehensive profile of small-molecule metabolites—which may occur without detectable changes in growth parameters or production yields [20] [21]. Research has demonstrated that engineered strains can show significant metabolomic perturbations while maintaining metabolic homeostasis and no apparent metabolic burden [20].

2. What are the primary triggers of metabolic burden in engineered strains?

The key triggers include:

- Depletion of amino acids and charged tRNAs due to heterologous protein expression [1]

- Over-use of rare codons in heterologous genes, leading to translation delays and errors [1]

- Competition for limited transcriptional and translational resources [20] [1]

- Plasmid amplification and maintenance costs [2]

- Energy drainage from native cellular processes to support recombinant pathways [20] [2]

3. How can I detect metabolomic alterations in my engineered strain?

Metabolomic alterations are detectable through several analytical techniques:

- Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy provides rapid molecular fingerprinting of the metabolic state [20]

- Mass spectrometry (MS) coupled with liquid or gas chromatography enables sensitive identification and quantification of metabolites [22] [23]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers structural information on metabolites without destruction of samples [23] These approaches can reveal metabolic reshuffling involved in maintaining homeostasis even when no growth defects are observed [20].

4. Can metabolomic alterations occur without metabolic burden?

Yes. Studies on Saccharomyces cerevisiae engineered with multiple δ-integration of a β-glucosidase gene demonstrated that metabolomic profiles were significantly altered under both growing and stressing conditions, yet the strain showed no detectable metabolic burden in terms of growth parameters or ethanol production [20] [21]. This indicates that metabolic reshuffling can maintain homeostasis without manifesting as traditional burden symptoms.

5. What strategies can mitigate metabolic burden in engineered strains?

Effective strategies include:

- Using genomic integration instead of plasmid-based expression systems [20]

- Optimizing codon usage while preserving important rare codon regions for proper protein folding [1]

- Implementing dynamic regulation to delay heterologous expression until sufficient biomass is achieved [2]

- Selecting industrial host strains with inherent robustness to stress [20]

- Engineering precursor and energy availability to support both native and heterologous functions [17]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Recombinant Strain Shows Reduced Growth Rate

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Troubleshooting Reduced Growth Rate in Engineered Strains

| Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Resource competition | Measure ATP levels, amino acid pools; conduct proteomic analysis [2] | Use stronger promoters for energy/metabolite generation genes; supplement media with key nutrients |

| Toxic metabolite accumulation | Metabolomic profiling via LC-MS/GC-MS; measure product/substrate toxicity [22] | Implement product export systems; dynamic pathway control; host engineering for tolerance |

| Protein misfolding | Analyze inclusion body formation; monitor chaperone expression [1] | Co-express chaperones; lower expression temperature; optimize codon usage [1] |

| Transcriptional/translational overload | RNA-seq to monitor rRNA/tRNA levels; proteomics for ribosome subunits [2] | Genomic integration vs. plasmids; optimize promoter strength; tune expression timing |

Experimental Protocol: Growth Analysis with Metabolite Profiling

- Culture Conditions: Grow parental and engineered strains in appropriate media with necessary selection pressure. Use at least 3 biological replicates [20].

- Growth Monitoring: Measure OD600 every 30-60 minutes. Calculate maximum specific growth rate (μmax) during exponential phase [2].

- Metabolite Sampling: At key growth phases (early exponential, late exponential, stationary), rapidly collect cells via vacuum filtration and quench metabolism in liquid nitrogen [20].

- Metabolite Extraction: Use 40:40:20 methanol:acetonitrile:water with 0.1% formic acid at -20°C for 1 hour [22].

- FTIR Analysis: As described in [20], resuspend cell pellets in saline solution, dry on IR slides, and acquire spectra in transmission mode (4000-600 cm⁻¹ range).

- Data Interpretation: Compare growth parameters and metabolomic profiles between strains. Significant metabolomic changes without growth impacts suggest metabolic reshuffling rather than burden.

Problem: Heterologous Protein Expression Declines Over Time

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Troubleshooting Unstable Protein Expression

| Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic instability | Plate stability tests; plasmid copy number quantification; sequencing [1] | Use genomic integration; implement selective pressure; optimize genetic design |

| Metabolic burden | Proteomic analysis of ribosomal proteins; monitor energy charges [2] | Weaken promoter strength; inducible expression; dynamic regulation [17] |

| Cumulative toxicity | Long-term culturing with periodic expression checks; viability staining [2] | Periodic culture reinoculation; host engineering for tolerance; media optimization |

Experimental Protocol: Proteomic Analysis for Burden Assessment

- Sample Preparation: Culture E. coli M15 or DH5α strains in LB or M9 media. Induce recombinant protein expression at different growth phases (OD600 = 0.1 vs 0.6) [2].

- Protein Extraction: Harvest cells at mid-log and late-log phases. Lyse using ultrasonication in appropriate buffer.

- Label-Free Quantification (LFQ) Proteomics: Digest proteins with trypsin, desalt peptides, and analyze by LC-MS/MS [2].

- Data Analysis: Identify significant changes in proteins involved in transcription, translation, fatty acid biosynthesis, and stress response pathways.

- Correlation with Performance: Compare proteomic profiles with growth metrics and protein production yields to identify burden indicators.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Burden Assessment Using FTIR Spectroscopy

Based on the methodology from [20] with Saccharomyces cerevisiae:

Materials:

- Yeast strains (parental and engineered)

- YPD medium (yeast extract 1%, peptone 1%, dextrose 2%)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- FTIR spectrometer with transmission module

- Aluminum slides for sample presentation

Procedure:

- Inoculate strains in YPD medium at OD600 = 0.2 and grow for 18 hours at 25°C with shaking at 200 rpm.

- Harvest cells during early exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.8) by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 5 minutes.

- Wash cells twice with sterile PBS and resuspend in appropriate volume for FTIR analysis.

- Apply uniform cell suspension to IR-transpatible slides and air-dry under laminar flow.

- Acquire FTIR spectra in transmission mode with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, averaging 64 scans per sample.

- Process spectra using multivariate analysis (principal component analysis) to identify metabolomic alterations.

Expected Results: Engineered strains may show significant differences in lipid (3000-2800 cm⁻¹), protein (1700-1500 cm⁻¹), and carbohydrate (1200-900 cm⁻¹) region absorbances indicating metabolomic alterations, even without growth defects [20].

Protocol 2: Proteomic Workflow for Metabolic Burden Investigation

Adapted from [2] with E. coli:

Materials:

- E. coli strains (control and recombinant)

- LB and M9 minimal media

- Lysis buffer (8 M urea, 2 M thiourea in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0)

- Trypsin for protein digestion

- C18 desalting columns

- LC-MS/MS system with nanoflow capabilities

Procedure:

- Culture strains in LB and M9 media, inducing protein expression at OD600 of 0.1 and 0.6.

- Harvest cells at mid-log (OD600 ≈ 0.8) and late-log (12 hours post-inoculation) phases.

- Lyse cells by sonication in urea/thiourea buffer, reduce with DTT, and alkylate with iodoacetamide.

- Digest proteins with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio) overnight at 37°C.

- Desalt peptides using C18 columns and analyze by nano-LC-MS/MS.

- Process data using MaxQuant or similar software, comparing protein abundance changes between conditions.

Expected Results: Recombinant strains may show significant alterations in proteins involved in transcription, translation, fatty acid biosynthesis, and stress response, with the extent of changes dependent on induction timing and media composition [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Metabolic Burden Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Molecular fingerprinting of metabolic state | Rapid detection of metabolomic alterations in whole cells [20] |

| LC-MS/MS System | Identification and quantification of metabolites/proteins | Targeted and untargeted metabolomics and proteomics [22] [2] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (¹³C-glucose, ¹⁵N-ammonia) | Metabolic flux analysis | Mapping carbon/nitrogen flow through pathways [22] |

| pQE30 Vector System (T5 promoter) | Recombinant protein expression | Controlled protein production in E. coli [2] |

| Specialized Growth Media (M9 minimal media) | Defined growth conditions | Investigating nutrient-specific effects on metabolism [2] |

Visualizations

Metabolic Burden Triggers and Responses

Experimental Workflow for Burden Assessment

Engineering Solutions: Advanced Strategies to Alleviate Cellular Burden

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource is designed to assist researchers in navigating common challenges in metabolic engineering. The following guides and protocols provide actionable solutions for optimizing pathway flux and ensuring the long-term stability of engineered microbial strains, directly addressing the metabolic burden that often undermines industrial bioprocessing.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is "metabolic burden" and what are its common symptoms? Metabolic burden refers to the stress imposed on a host cell after metabolic engineering, which can include the (over)expression of heterologous proteins or the introduction of new synthetic pathways. This stress drains the cell's resources and disrupts its finely tuned metabolic balance [1]. Common observable symptoms include [1]:

- Decreased cellular growth rate

- Impaired protein synthesis

- Genetic instability

- Aberrant cell size

- Low production titers in large-scale fermentations

FAQ 2: Why does my engineered strain lose productivity over long fermentation runs?

This is a classic sign of strain degeneration [24]. Engineered, productive cells (X1) often face a metabolic burden, giving them a competitive disadvantage compared to non-productive mutant cells (X2) that may arise. In a bioreactor, these faster-growing non-productive cells can outcompete and overtake the population, leading to a loss of overall production [24]. The mathematical model below describes this dynamic, where ( \theta ) represents the rate at which productive cells degenerate into non-productive revertants.

\begin{align*}

\frac{dX_1}{dt} &= \mu_1 X_1 - \theta X_1 - D X_1 \\

\frac{dX_2}{dt} &= \mu_2 X_2 + \theta X_1 - D X_2

\end{align*}

FAQ 3: How can I select the best objective function for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to match my experimental data? Traditional FBA uses a static objective (e.g., biomass maximization), which may not reflect real metabolic behavior under all conditions. The TIObjFind framework addresses this by integrating FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to infer context-specific objective functions from your experimental flux data. It calculates Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions, which act as weights to create an objective function that aligns model predictions with experimental observations [25] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Imbalanced Pathway Flux and Low Product Yield

Potential Cause: The heterologous pathway is not well integrated with the host's metabolism, leading to insufficient precursor flux, accumulation of toxic intermediates, or improper expression levels of pathway enzymes [27] [1].

Solutions:

- Combinatorial Pathway Optimization: Instead of sequential "de-bottlenecking," use combinatorial libraries to simultaneously vary multiple pathway elements. This includes testing different gene homologs and tuning expression levels via promoters, RBSs, and gene dosage to find a globally optimal balance [27].

- Implement Dynamic Metabolic Control: Use growth-coupled feedback genetic circuits. These circuits tie the production of the target compound to the cell's growth fitness, creating a "metabolic reward" system that selectively advantages high-producing cells during fermentation [24].

Problem 2: Strain Degeneration in Continuous Bioreactors

Potential Cause: Non-producing revertant cells (X2) have a significant growth advantage (( \mu2 > \mu1 )) over your productive engineered cells (X1), leading to their eventual dominance in the population [24].

Solutions:

- Strengthen Metabolic Coupling: Enhance the design of your genetic circuits to create a stronger obligatory link (quantified by a higher metabolic coupling coefficient, ( \Gamma )) between product formation and essential growth processes. This makes it metabolically costly for cells to lose the production phenotype [24].

- Optimize Bioreactor Operation: In a Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactor (CSTR), the dilution rate (D) is a critical parameter. Our analysis indicates that a metabolic-reward mediated positive feedback loop can create a bistable system. Operating within this bistable region allows productive cells to maintain a stable population despite the presence of non-producing variants [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Metabolic Objectives with TIObjFind

This protocol uses the TIObjFind framework to determine a data-driven objective function for FBA, improving flux prediction accuracy [25] [26].

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Gather your genome-scale metabolic model (in SBML format) and measured experimental flux data ((v^{exp})) for key metabolites under your specific condition [25] [26].

- Single-Stage Optimization: Solve an optimization problem to find flux distributions that minimize the squared error between FBA predictions and (v^{exp}). This step generates a candidate flux distribution ((v^*)) [25] [26].

- Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction: Map the flux distribution (v^*) onto a directed, weighted graph where nodes represent reactions and edges represent metabolite flow [25] [26].

- Pathway Analysis via Minimum-Cut: Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify critical pathways and reactions between a source (e.g., glucose uptake) and a sink (e.g., product secretion) [25].

- Coefficient Calculation: The minimum-cut analysis yields Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for each reaction, quantifying their contribution to the objective [25] [26].

Technical Notes:

- Implementation: The TIObjFind framework was implemented in MATLAB, utilizing its

maxflowpackage for minimum-cut calculations [25]. - Visualization: Results can be visualized in Python using packages like

pySankey[25].

Protocol 2: Simulating Population Dynamics to Combat Strain Degeneration

This protocol uses a mathematical model to predict and prevent the takeover of a bioreactor by non-productive cells [24].

Workflow Overview:

Methodology:

- Define the Model: Use the system of equations provided in FAQ 2 to describe the interaction between productive (X1) and non-productive (X2) cell populations [24].

- Parameterize the System: Estimate or measure key parameters:

- ( \mu1, \mu2 ): Growth rates of productive and non-productive cells.

- ( \theta ): The rate of degeneration (mutation) from X1 to X2.

- ( D ): Dilution rate in the CSTR.

- ( \Gamma ): Metabolic coupling coefficient, representing how strongly product formation is tied to growth [24].

- Numerical Simulation: Implement the model in a computational environment like MATLAB (using

ode15sorode45solvers) to simulate the population dynamics over time [24]. - Stability Analysis: Analyze the simulation output to find steady-state solutions and determine their stability. The goal is to identify operating conditions (values of ( D ) and ( \Gamma )) where the steady-state population of X1 is stable and dominant [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Pathway Optimization |

|---|---|

| SBML Model Files | Standardized XML files that define the stoichiometric metabolic network, enabling interoperability between simulation tools like Arcadia, CellDesigner, and COPASI [28]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A constraint-based modeling approach used to predict metabolic flux distributions by optimizing a cellular objective (e.g., growth). It is the foundation for advanced frameworks like TIObjFind [25] [26]. |

| Combinatorial Gene Library | A collection of genetic constructs where multiple pathway elements (e.g., promoters, RBSs, gene homologs) are systematically varied. This library allows for high-throughput screening of optimally balanced pathways [27]. |

| Growth-Coupled Genetic Circuit | A synthetic biology construct that links the production of a target metabolite to the host's growth fitness or survival, enforcing evolutionary stability of the production phenotype [24]. |

| Coefficient of Importance (CoI) | A quantitative metric calculated by the TIObjFind framework that weights the contribution of individual metabolic reactions to a data-informed cellular objective function [25] [26]. |

Quantitative Parameters for Strain Stability

The following table summarizes key parameters from the population dynamics model that influence strain degeneration in a CSTR [24].

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Coupling Coefficient | ( \Gamma ) | Quantifies the strength of the link between product formation and growth. | A higher ( \Gamma ) strengthens the selective advantage of productive cells (X1), countering degeneration. |

| Dilution Rate | ( D ) | The rate at which fresh media is added and culture is removed from the bioreactor (1/time). | Must be carefully optimized with ( \Gamma ); an incorrect ( D ) can lead to washout of X1 even with strong coupling. |

| Degeneration Frequency | ( \theta ) | The rate at which productive cells mutate into non-productive revertants (1/time). | A lower ( \theta ) is always desirable, as it slows the generation of competing X2 cells. |

| Growth Rate Ratio | ( \mu2 / \mu1 ) | The relative fitness of non-productive vs. productive cells. | A ratio >1 indicates a strong fitness disadvantage for the engineered strain, requiring stronger countermeasures (higher ( \Gamma )). |

A primary obstacle in developing efficient microbial cell factories is metabolic burden, a stress condition triggered by engineering metabolic pathways. This burden manifests as decreased growth rate, impaired protein synthesis, and genetic instability, ultimately reducing production titers and process viability [1]. Multidimensional metabolic engineering addresses these challenges through integrated strategies that simultaneously optimize pathway flux, cofactor balance, and subcellular organization to create robust production hosts.

The following technical support content provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for implementing these integrated strategies, based on recent advances in the field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is multidimensional metabolic engineering and how does it differ from traditional approaches? Multidimensional metabolic engineering moves beyond sequential single-gene edits to implement simultaneous, synergistic modifications across multiple cellular domains. This includes pathway engineering, cofactor manipulation, and organelle engineering, all coordinated to overcome the complex limitations of engineered strains [29] [30]. Where traditional approaches might address enzyme expression alone, multidimensional strategies concurrently optimize precursor supply, energy availability, and spatial organization to maximize production while minimizing metabolic burden.

Q2: Why does my engineered strain show reduced growth after introducing a heterologous pathway? Reduced growth is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, primarily caused by:

- Resource competition between native and heterologous pathways for precursors, energy, and amino acids

- Cellular stress responses activated by protein overexpression and intermediate accumulation

- Toxicity of pathway intermediates or products to the host [1] [2] This growth retardation indicates that the host's metabolic network is overwhelmed, requiring rebalancing through the multidimensional strategies outlined in this guide.

Q3: How can organelle engineering help overcome metabolic bottlenecks? Organelle engineering addresses bottlenecks by:

- Creating specialized subcellular environments with optimized conditions for specific reactions

- Preventing metabolic crosstalk between heterologous and native pathways through physical separation

- Concentrating substrates and enzymes to enhance reaction kinetics [31] [32] For example, targeting pathways to peroxisomes or engineering membrane contact sites can significantly increase carbon flux to desired products [29].

Q4: What are the most critical cofactors to balance in engineered strains? NADPH is frequently a limiting cofactor, particularly in biosynthetic pathways like betulinic acid production where it serves as a crucial electron donor [29]. Additionally, ATP and acetyl-CoA availability often constrains pathway flux. Implementing redox engineering strategies, such as introducing NADP+-dependent enzymes to convert NADH to NADPH, can dramatically improve production outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Multidimensional Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Metabolic Engineering Challenges

| Problem Symptom | Root Cause | Multidimensional Solution | Validated Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product titer despite high pathway expression | Insufficient precursor supply; Cofactor limitation | Introduce non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) or isoprenol utilization pathway (IUP); Implement redox engineering [29] | Betulinic acid production increased with enhanced acetyl-CoA and IPP supply [29] |

| Toxic intermediate accumulation | Metabolic crosstalk; Slow conversion rates | Subcellular compartmentalization; Enzyme engineering to improve catalytic efficiency [29] [32] | CYP716A155 mutation (E120Q) enhanced activity and reduced intermediate accumulation [29] |

| Growth impairment in production hosts | Metabolic burden; Energy depletion | Global metabolic rewiring; Mobilize lipid metabolism; Fine-tune glycolysis [29] [1] | Engineered Y. lipolytica achieved high titers without severe growth defects [29] |

| Declining production in extended cultures | Genetic instability; Stress response activation | Dynamic induction control; Mid-log phase induction; Optimize media composition [2] | Induction at OD600 ~0.6 maintained expression versus early induction [2] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Multidimensional Engineering

Protocol: Enhancing Cofactor Supply via Redox Engineering

Purpose: Increase NADPH availability to support NADPH-dependent biosynthetic reactions.

Procedure:

- Identify NADPH-dependent steps in your target pathway and quantify NADPH requirements.

- Introduce NADP+-dependent enzymes such as GPD1 and MCE2 to convert cytosolic NADH to NADPH [29].

- Implement transhydrogenation cycles to balance NADH/NADPH pools.

- Verify cofactor balancing by measuring NADPH/NADP+ ratios and pathway flux.

Validation: In betulinic acid production, this approach significantly improved carbon conversion efficiency [29].

Protocol: Subcellular Compartmentalization for Pathway Isolation

Purpose: Physically separate heterologous pathways from native metabolism to reduce crosstalk and intermediate toxicity.

Procedure:

- Select target organelle based on pathway requirements (peroxisomes, ER, or mitochondria) [31].

- Engineer signal peptides to target pathway enzymes to selected organelles.

- Enhance organelle biogenesis if necessary to accommodate heterologous enzymes.

- Optimize transport of substrates and products across organelle membranes.

- Consider engineering membrane contact sites (MCSs) to accelerate inter-organelle metabolite transfer [29].

Validation: Organelle engineering in Yarrowia lipolytica accelerated downstream carbon flux for betulinic acid synthesis [29].

Protocol: Multi-modular Pathway Balancing

Purpose: Coordinate expression and activity across multiple pathway modules to prevent intermediate accumulation or depletion.

Procedure:

- Divide pathway into logical modules (e.g., precursor supply, core reactions, diversification).

- Fine-tune expression of each module using promoters of varying strengths or inducible systems.

- Monitor key intermediate levels to identify bottlenecks.

- Apply protein engineering to optimize enzyme kinetics for rate-limiting steps.

- Down-regulate competing pathways to redirect carbon flux.

Validation: In Yarrowia lipolytica, this approach included mobilization of lipid metabolism, down-regulation of competing sterol pathways, and fine-tuning of glycolysis [29].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table: Performance Metrics from Multidimensional Metabolic Engineering Implementation

| Engineering Strategy | Host Organism | Target Product | Reported Titer | Key Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multidimensional engineering (Pathway, Cofactor, Organelle) [29] | Yarrowia lipolytica | Betulinic acid | 271.3 mg L⁻¹ (shake-flask); 657.8 mg L⁻¹ (bioreactor) | Highest reported titer; Cost-effective mannitol utilization |

| Organelle engineering & spatial organization [32] | Model systems | Various | Pathway-dependent (1-4 order magnitude flux enhancement predicted) | Enhanced kinetics; Reduced intermediate toxicity |

| Timed induction optimization [2] | E. coli (M15) | Acyl-ACP reductase | Significantly higher than early induction | Reduced metabolic burden; Sustained protein expression |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Multidimensional Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Carbon Sources | Alternative carbon utilization to reduce metabolic burden | Mannitol from algal biomass for betulinic acid production [29] |

| NADP+-dependent Enzymes | Cofactor engineering to enhance NADPH supply | GPD1 and MCE2 for NADH to NADPH conversion [29] |

| Organelle-Targeting Signal Peptides | Subcellular compartmentalization of heterologous pathways | Targeting enzymes to peroxisomes or ER for pathway isolation [31] |

| Engineered P450 Enzymes | Enhanced catalytic activity for oxidative reactions | CYP716A155 with E120Q mutation for improved betulinic acid production [29] |

| Non-oxidative Glycolysis (NOG) Pathway | Enhanced precursor supply | Increased acetyl-CoA for betulinic acid biosynthesis [29] |

Visual Guide: Multidimensional Engineering Workflow

Multidimensional Engineering Workflow

This diagram illustrates the integrated troubleshooting approach for overcoming metabolic burden through multidimensional engineering strategies. The process begins with diagnosing metabolic burden symptoms, then simultaneously applies pathway, cofactor, and organelle engineering to develop an integrated solution strategy, ultimately producing an optimized cell factory.

Integrated Strategy for Betulinic Acid Production

This diagram details the successful multidimensional engineering strategy implemented in Yarrowia lipolytica for betulinic acid production, demonstrating how pathway, cofactor, and organelle engineering work synergistically to achieve high product titers.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common CRISPR/Cas9 Experimental Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency [33] [34] | - Poor gRNA design- Inefficient delivery- Low Cas9/gRNA expression | - Design & test 3-4 different gRNA targets [34]- Optimize delivery method (electroporation, lipofection) [33]- Use a strong, cell-type-appropriate promoter [33] |

| High off-target activity [33] [34] | - gRNA binding to unintended sites- High Cas9/gRNA concentration | - Use highly specific gRNA design tools [33]- Titrate sgRNA and Cas9 amounts [34]- Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [33] [35] |

| Cell toxicity [33] | - High metabolic burden- Persistent Cas9 expression- Off-target DSBs | - Titrate CRISPR component concentrations [33]- Use Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery instead of plasmids [34] |

| No PAM sequence near target [34] | - Target sequence constraints | - Use NAG as an alternative PAM (with lower efficiency) [34]- Employ PAM-flexible Cas9 variants (e.g., xCas9, SpCas9-NG) [35] |

Common MAGE Recombineering Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low recombineering efficiency [36] [37] | - Inefficient oligo design- Active mismatch repair system- Low λ-Red expression | - Use 90-mer oligos with 20-35 bp homology arms [37]- Use a strain with a transient or permanent mutS knockout [36] [37] |

| Difficulty screening recombinants [36] [37] | - No phenotypic change- Low fraction of modified cells in population | - Couple with CRISPR/Cas9 for negative selection against wild-type cells [36] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

CRISPR/Cas9 Design and Application

Q: What are the key considerations for designing a high-quality sgRNA? A: The most critical factors are:

- Specificity: The 20-nucleotide spacer sequence should be unique to your target to minimize off-target effects. Tools like Synthego's design tool or CHOPCHOP can help predict specificity [38].

- PAM Site: The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) must be present immediately adjacent to your target site. For SpCas9, this is 5'-NGG-3' [35].

- Seed Sequence: Ensure the 8-12 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA (the "seed" sequence adjacent to the PAM) have perfect homology to your target, as mismatches here are most likely to prevent cleavage [34] [35].

- GC Content: Aim for a GC content between 40% and 80% for optimal gRNA stability and performance [38].