Modular Metabolic Engineering: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Biobased Chemical Production

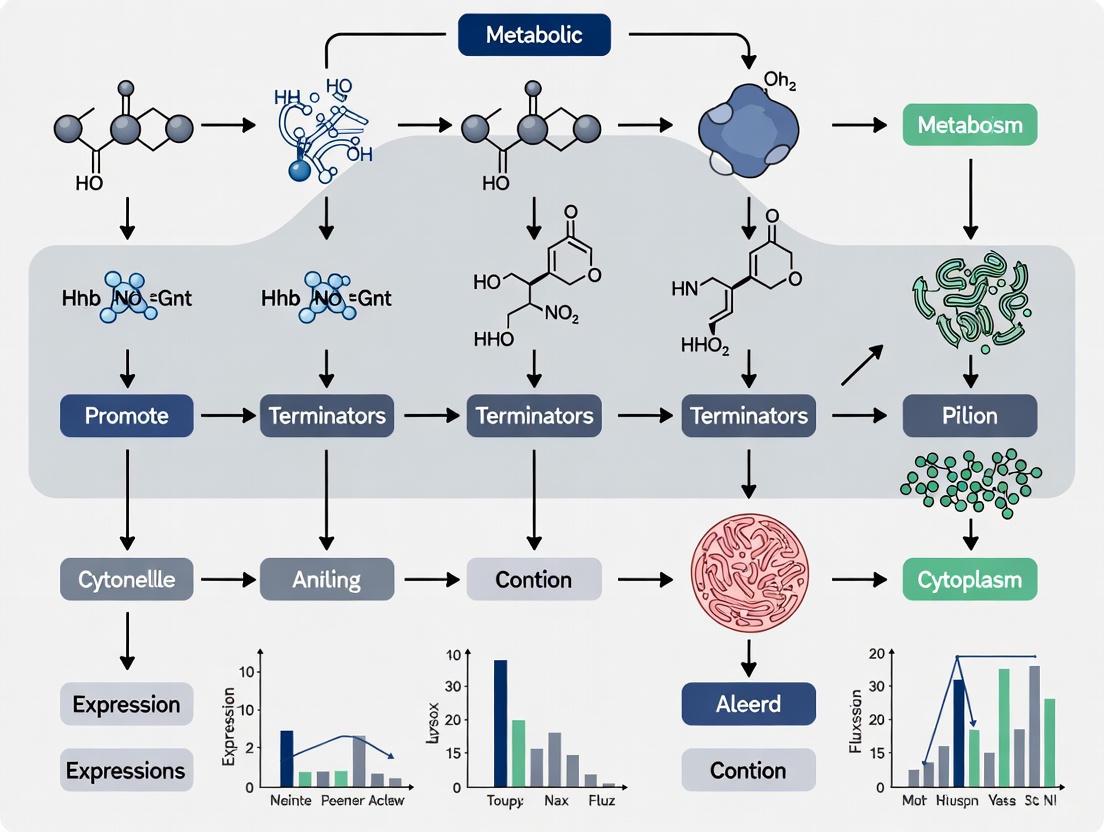

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modular metabolic engineering (MME), a transformative approach that addresses the challenges of metabolic imbalance in engineered microbial strains.

Modular Metabolic Engineering: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Biobased Chemical Production

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modular metabolic engineering (MME), a transformative approach that addresses the challenges of metabolic imbalance in engineered microbial strains. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore MME's foundational principles, which involve partitioning complex pathways into manageable, fine-tuned modules. The scope encompasses detailed methodological applications across diverse hosts like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for producing high-value chemicals, including pharmaceuticals, fragrances, and amino acids. We further delve into advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies, such as multivariate modular metabolic engineering (MMME) and synthetic cocultures, and validate these approaches through comparative analysis of titers, yields, and productivity. The integration of MME with genome-scale models and advanced analytics is highlighted as a critical pathway for accelerating the development of robust microbial cell factories and revitalizing the pipeline for antibiotic discovery and biomanufacturing.

Deconstructing Modular Metabolic Engineering: Core Principles and System-Level Benefits

Modular metabolic engineering is a synthetic biology strategy that breaks down complex metabolic pathways into smaller, standardized, and manageable functional units, or modules [1]. This approach transforms the engineering of cellular factories from a trial-and-error process into a more predictable and systematic endeavor, facilitating the optimization of metabolic flux and the division of labor [2]. The core principle is to reduce complexity by designing, building, and testing discrete pathway modules that can be independently optimized and reassembled in different combinations. This is particularly vital for overcoming the challenge of metabolic burden and imbalanced flux in engineered strains, which often penalizes cell fitness and pathway productivity [1]. By applying principles of modularity, researchers can more efficiently develop microbial platforms for the sustainable production of biobased chemicals, moving from proof-of-concept to economically viable systems [1] [3].

Theoretical Foundations of Pathway Modularity

The concept of modularity in biological systems is supported by the inherent organization of metabolism. Fundamental research on metabolic networks has revealed that they are composed of conserved sequences of reactions, known as reaction modules, which function as reusable building blocks [4]. These modules are defined by conserved chemical structure transformation patterns and often correspond to functional units in genomic data, such as operon-like gene clusters [4].

In practical metabolic engineering, this foundational insight translates into several distinct strategic applications [2]:

- Modular Cloning: Utilizing standardized DNA parts to rapidly generate combinatorial libraries of expression cassettes for optimizing gene expression levels.

- Modular Pathway Engineering: Dividing a long biosynthetic pathway into shorter, coherent functional modules (e.g., a precursor synthesis module and a product formation module) that can be individually balanced.

- Modular Coculture (MCE): Distributing different metabolic modules across multiple microbial strains in a consortium, leveraging the unique strengths of each specialist strain.

Key Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering (MMME) in a Single Host

MMME is a combinatorial approach designed to balance metabolic flux by treating a biosynthetic pathway as two core modules: the Upstream Module and the Downstream Module [1]. The upstream module typically generates central precursors, while the downstream module converts these precursors into the final target compound. The key is to tune the expression of genes within each module independently to find the optimal flux distribution that maximizes yield without overburdening the host.

Protocol: Implementing MMME for Flux Balancing

- Pathway Division: Split the target biosynthetic pathway into two logical modules. The upstream module often involves core metabolism (e.g., acetyl-CoA synthesis), while the downstream module contains the specific heterologous enzymes for product synthesis.

- Module Characterization: Quantify the individual performance of each module. This may involve measuring precursor accumulation for the upstream module and conversion efficiency from supplemented precursor for the downstream module.

- Combinatorial Assembly: Assemble a library of strains containing different combinations of expression levels for the two modules. This is typically achieved by using libraries of promoters or ribosome binding sites (RBS) of varying strengths for the genes in each module.

- High-Throughput Screening: Screen the combinatorial library for target molecule production. Advanced methods, such as biosensors coupled to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), are ideal for high-throughput analysis [3].

- Systems-Level Analysis: For top-performing strains, conduct multi-omics analysis (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to identify persistent bottlenecks or stress responses [3].

- Iterative Optimization: Use the insights gained from omics data to inform the next cycle of design, potentially refining module boundaries or expression parts.

The dot language script below illustrates the MMME concept.

Modular Coculture Engineering (MCE)

MCE, or synthetic coculture, extends modularity by distributing different metabolic modules across multiple engineered microbial strains [1]. This strategy alleviates the metabolic burden on a single host and allows each specialist strain to be optimized for its specific task. A classic division of labor involves one strain dedicated to producing a key intermediate and a second strain specialized in converting that intermediate into the final product.

Protocol: Designing and Optimizing a Synthetic Coculture

- Host Selection and Pathway Division: Choose two or more compatible microbial hosts (e.g., E. coli and S.. cerevisiae) and divide the target biosynthetic pathway accordingly. Consider the native strengths and weaknesses of each host (e.g., growth rate, precursor availability, tolerance to intermediates).

- Strain Construction: Genetically engineer each host to contain its designated metabolic module. Ensure that the module in the downstream strain is equipped to uptake and utilize the intermediate produced by the upstream strain.

- Establish Mutualism: Design the coculture system to be mutually beneficial. This can be achieved by cross-feeding essential nutrients or designing the product pathway such that it removes a growth-inhibiting intermediate [1].

- Optimize Cultivation Conditions: Systematically test different culture media to ensure they support the growth of all consortium members. Determine the optimal inoculation ratio (e.g., 1:1, 1:10) of the different strains to maximize product titer and yield [2].

- Monitor Community Dynamics: Use selective plating, flow cytometry, or strain-specific fluorescent markers to track the population composition of the coculture over time.

- Scale-Up Evaluation: Transition the optimized coculture from microplates or shake flasks to bioreactors, where parameters like dissolved oxygen and pH can be tightly controlled to maintain community stability.

The dot language script below illustrates a two-member coculture system.

Application Note: Raspberry Ketone Production inS. cerevisiae

A 2023 study effectively demonstrated all three modular strategies for the de novo production of raspberry ketone (RK) in S. cerevisiae, achieving the highest yield (2.1 mg/g glucose) reported in any organism without precursor supplementation [2]. The pathway was broken down into four distinct metabolic modules.

The dot language script below illustrates the modular pathway for raspberry ketone production.

Key Findings and Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance of Modular Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Raspberry Ketone Production in S. cerevisiae [2]

| Engineering Strategy | Strain / Community Description | RK Titer (mg/L) | RK Yield (mg/g glucose) | Key Precursor (HBA) Titer (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Pathway (Best Monoculture) | Engineered with Aro, p-CA, M-CoA, and RK modules | 63.5 | 2.1 | Not detected |

| Modular Coculture (CL_RK1) | Two-member community structure | 6.8 | 0.34 | 308.4 |

| Modular Coculture (CL_RK3) | Three-member community structure | 13.3 | 0.67 | 280.0 |

The data shows that while the optimized monoculture achieved the highest RK titer and yield, certain cocultures excelled at producing the direct precursor, 4-hydroxy benzalacetone (HBA), at very high levels (over 300 mg/L) [2]. This highlights how modular cocultures can be tuned for different production goals, such as generating intermediates for semi-synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Modular Metabolic Engineering

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Toolkits | Standardized DNA assembly for creating combinatorial gene expression libraries. | EcoFlex for E. coli; Golden Gate-based systems like MoClo for yeast and plants [2]. |

| Promoter & RBS Libraries | Fine-tuning gene expression strength within each module. | Constitutive and inducible promoters of varying strengths (e.g., PJ23100 series in E. coli; pCUP1 in yeast) [3]. |

| Biosensors | High-throughput screening of strain libraries for metabolite production. | Transcription factor-based or RNA aptamer-based systems linked to fluorescent reporters [3]. |

| Analytical Chromatography | Accurate identification and quantification of target molecules and pathway intermediates. | HPLC/UV, GC-MS, LC-MS for precise measurement of titer, yield, and productivity [3]. |

| Genome Editing Systems | Rapid genomic integration of metabolic modules. | CRISPR-Cas9 for precise, multiplexed genome editing in a wide range of hosts [1]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Pathway prediction, analysis, and metabolic model simulation. | Pathway Tools for metabolic reconstruction and flux-balance analysis (FBA) [5]. KEGG for reaction module analysis [4]. |

Modularity provides a powerful framework for tackling the inherent complexity of metabolic engineering. By decomposing pathways into functional units, researchers can systematically manage metabolic flux in single hosts or distribute the biochemical workload across synthetic microbial consortia. The application of modular cloning, modular pathway engineering, and modular cocultures, as demonstrated in the production of compounds like raspberry ketone, significantly accelerates the DBTL cycle. This structured approach is pivotal for advancing the sustainable bioproduction of valuable chemicals, moving the field from artisanal efforts toward standardized, predictable engineering principles.

Metabolic engineering aims to reprogram microbial cellular metabolism to convert renewable resources into valuable chemicals, materials, and fuels [6]. However, this rewiring often creates metabolic imbalances that reduce both product yields and host fitness. These imbalances occur when heterologous pathway expression creates burdens—resource competition, thermodynamic bottlenecks, and toxicity—that limit industrial scalability [7] [8].

Modular metabolic engineering addresses these challenges through a structured design paradigm. This approach partitions complex metabolic networks into discrete, functional units called modules, each dedicated to specific functions: carbon core processing, energy generation, or target product synthesis [7] [8]. This separation allows for independent optimization of individual modules before reintegration, minimizing disruptive interactions and enabling more predictable system behavior.

The theoretical foundation of modularization aligns with the broader evolution of metabolic engineering. The field has progressed through distinct waves: first, rational pathway design; second, systems biology integration; and now, a third wave driven by synthetic biology that enables complete pathway design and construction using synthetic DNA elements [6]. Modular design represents a maturation within this third wave, applying engineering principles of functional separation and standardized interfaces to biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Defining Metabolic Modules

In modular metabolic engineering, pathways are decomposed into functional units with distinct metabolic roles:

- Chassis Modules: Core metabolic networks in the host organism that maintain essential functions including central carbon metabolism, energy production, and growth capabilities. These modules provide precursor metabolites and cofactors for downstream production modules [7].

- Production Modules: Heterologous pathways introduced for biosynthesis of target compounds. These modules convert chassis-derived precursors into desired end products [7] [8].

- Energy Module: Specialized modules that optimize cofactor regeneration and energy management, often through synthetic pathways that enhance reducing equivalent supply [9].

This architectural separation enables independent optimization of growth and production functions, allowing engineers to balance resource allocation between cellular maintenance and product synthesis [7].

The Growth-Coupling Principle

A cornerstone of modern modular design is growth-coupled selection, where target product formation becomes intrinsically linked to host fitness [8]. This approach strategically introduces gene deletions that create auxotrophies or metabolic dependencies, then rescues growth through activity of introduced production modules. The resulting strain grows only when the production module is functionally active, creating a powerful selective pressure for pathway optimization during adaptive laboratory evolution [8].

The metabolic network below illustrates how this growth-coupling principle functions within a modular framework:

Diagram: Growth-coupling through modular design. Strategic gene deletions create metabolic dependencies rescued only by production module activity, linking product formation to host fitness.

Computational Frameworks for Modular Design

Model-Assisted Modular Optimization

Computational tools enable predictive design of modular cell factories through multi-objective optimization formulations. The ModCell2 framework designs modular chassis strains compatible with large libraries of exchangeable production modules [7]. This approach treats each target phenotype activated by a module as an independent objective within a Pareto optimization problem, identifying optimal gene knockout sets that maximize compatibility across diverse production pathways.

Advanced algorithms like ModCell-HPC utilize high-performance computing to solve modular design problems with hundreds of objectives, representing production modules for biochemically diverse compounds [7]. These computational methods have identified modular chassis designs with minimal gene sets that maintain compatibility with extensive product libraries, demonstrating the scalability of modular approaches.

Quantitative Pathway Design Algorithms

The QHEPath algorithm provides quantitative assessment of heterologous pathway designs, evaluating over 12,000 biosynthetic scenarios across 300 products and 4 substrates in 5 industrial organisms [9]. This systematic analysis revealed that over 70% of product pathway yields can be improved by introducing appropriate heterologous reactions, with 13 identified engineering strategies effective for breaking stoichiometric yield limitations.

Cross-species metabolic network models enable quantitative prediction of pathway performance across different chassis organisms. These models incorporate quality-controlled biochemical reactions from multiple species, eliminating errors that previously limited predictive accuracy [9].

Application Notes: Implementing Modular Designs

Growth-Coupled Selection Workflow

The experimental pipeline for implementing growth-coupled modular designs follows an adapted Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle where biomass formation serves as the primary screening metric [8]. This approach bypasses analytical bottlenecks in high-throughput strain engineering by using growth as a proxy for module performance.

Diagram: Growth selection-based DBTL cycle for modular engineering. Biomass measurement replaces analytical chemistry as primary test metric, accelerating optimization.

Quantitative Performance Data

Modular approaches have demonstrated significant improvements in metabolic efficiency across diverse host organisms and product classes. The table below summarizes representative achievements:

Table: Performance Metrics of Modular Metabolic Engineering in Model Organisms

| Host Organism | Target Product | Modular Strategy | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Lycopene | Modular cofactor engineering + pathway balancing | 58 mg/g DCW | [9] |

| Escherichia coli | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) | Non-oxidative glycolysis module | Yield exceeded stoichiometric limit | [9] |

| Escherichia coli | N-hexanol | Growth-coupled upper pathway optimization | Enhanced precursor supply | [8] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | β-carotene | Lipid engineering + pathway modularization | 217.5 mg/g DCW | [10] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Lysine | Transporter + cofactor module engineering | 223.4 g/L, 0.68 g/g glucose | [6] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Malonic acid | Modular pathway + genome editing | 63.6 g/L, 0.41 g/L/h | [6] |

These implementations demonstrate how modularization enables deep metabolic rewiring that surpasses inherent stoichiometric limitations of native networks. For example, introducing the non-oxidative glycolysis pathway in E. coli enables generation of three acetyl-CoA molecules per glucose instead of the native two, fundamentally changing carbon efficiency [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing Growth-Coupled Selection Strains

This protocol creates selection strains where module functionality is coupled to host fitness through strategic gene deletions.

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial chassis (e.g., E. coli MG1655)

- CRISPR-Cas9 system for precise genome editing

- Synthtic gene modules codon-optimized for host

- M9 minimal medium with defined carbon sources

- Antibiotics for selection pressure

- Analytical standards for target metabolites

Procedure

In Silico Design Phase

- Identify target gene deletions that create auxotrophy for module-derived metabolite

- Verify producibility using genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., CSMN model)

- Design rescue module with heterologous enzymes to overcome metabolic lesion

Strain Construction Phase

- Transform host with CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid targeting deletion loci

- Introduce heterologous module via plasmid or genomic integration

- Verify genotype through colony PCR and sequencing

Validation Phase

- Culture selection strain in minimal medium without metabolite supplementation

- Measure growth kinetics (OD600) as proxy for module functionality

- Compare with control strains (wild-type, deletion without rescue)

- Quantify metabolite production via LC-MS/HPLC to correlate with growth

Adaptive Evolution

- Serial passage selection strain under selective conditions

- Monitor growth improvement over 50-100 generations

- Isolate evolved clones and sequence to identify causal mutations

Protocol 2: Modular Pathway Optimization Using Computational Tools

This protocol employs computational design tools to identify optimal modular configurations before experimental implementation.

Materials and Reagents

- Genome-scale metabolic model of host organism (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli)

- ModCell-HPC software for modular design

- QHEPath web server for heterologous pathway evaluation

- LASER database of curated metabolic engineering designs

Procedure

Model Preparation

- Download and validate genome-scale model from BiGG Database

- Incorporate heterologous reactions using biochemical databases

- Apply thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible cycles

Modular Design Implementation

- Define production module stoichiometry based on target compound

- Run ModCell-HPC to identify optimal gene knockout sets for modular chassis

- Evaluate compatibility across product library using Pareto front analysis

- Select chassis design with maximal product coverage and minimal gene set

Pathway Validation

- Input target product and substrate into QHEPath algorithm

- Evaluate yield improvement potential with heterologous reactions

- Compare multiple pathway variants for carbon efficiency

- Select optimal pathway based on predicted yield and host compatibility

Experimental Translation

- Implement computational designs using synthetic DNA assembly

- Validate model predictions through fermentation experiments

- Iterate using machine learning to improve model accuracy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for Modular Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision genome editing | Creating gene deletions for growth coupling | Enable multiplexed deletions for complex modular chassis |

| Genome-Scale Models | Metabolic flux prediction | Identifying yield-limiting steps | Constrain with experimental data for improved accuracy |

| Cross-Species Metabolic Network (CSMN) | Heterologous pathway design | Evaluating non-native reactions in host context | Quality-controlled to eliminate thermodynamic errors |

| ModCell-HPC Algorithm | Modular chassis design | Identifying gene knockouts for product compatibility | Scalable to hundreds of production objectives |

| QHEPath Web Server | Quantitative pathway evaluation | Predicting yield improvements | Covers 300+ products across multiple industrial hosts |

| LASER Database | Design rule extraction | Accessing curated metabolic engineering designs | Contains 417 designs with 2661 genetic modifications |

| Adaptive Laboratory Evolution | Strain optimization under selection | Improving module flux capacity | Requires 50-100 generations for significant improvement |

Modular metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in microbial strain development, replacing ad hoc optimization with systematic design principles. Through strategic functional separation and growth-coupling, this approach addresses fundamental challenges of metabolic imbalance that have limited industrial bioproduction.

Future advancements will likely focus on increasing modular predictability through improved computational models that incorporate enzyme kinetics and regulatory constraints [11]. The integration of machine learning with mechanistic models will enhance design accuracy, while emerging tools for multiplex genome engineering will accelerate implementation of complex modular designs [7] [11].

As the field matures, standardized modular parts and interfaces may enable plug-and-play metabolic engineering, where production pathways can be readily exchanged between optimized chassis strains. This interoperability would dramatically accelerate development timelines for microbial chemical production, ultimately expanding the range of sustainably manufactured products available to society [6] [8].

Modular metabolic engineering (MME) is a synthetic biology strategy that breaks down complex metabolic pathways into smaller, manageable, and standardized functional units, or modules. This approach simplifies the optimization of microbial cell factories by allowing for independent tuning of different pathway segments, thereby addressing challenges such as metabolic burden, intermediate toxicity, and cofactor imbalance. The three primary system architectures in MME—Univariate, Multivariate (MMME), and Coculture (MCE) Strategies—provide a structured framework for engineering efficient bio-production systems. By refactoring pathways into modules for precursor synthesis, cofactor regeneration, or product formation, MME enables a more rational and high-throughput exploration of the design space, leading to accelerated development of strains for the sustainable production of chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fuels [2] [12].

Univariate Strategies

Core Principle and Application Notes

Univariate strategies focus on the optimization of a single variable or genetic part at a time while keeping all other parameters constant. This approach is foundational for establishing baseline performance and understanding the individual impact of specific components within a metabolic pathway, such as promoters, ribosome binding sites (RBS), or gene copy number. It is particularly effective for initial pathway debugging and for identifying rate-limiting steps in a biosynthetic process.

A prime application is modular cloning for promoter engineering. By constructing combinatorial libraries of promoters to drive the expression of individual genes in a pathway, researchers can identify the optimal expression level for each enzyme. For instance, in the production of raspberry ketone (RK) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a library of promoters with varying strengths can be assembled to control the expression of genes like 4CL (4-coumaroyl-CoA ligase) and BAS (benzalacetone synthase), allowing for the systematic identification of the best-performing strain variant [2].

Experimental Protocol: Promoter Library Construction and Screening

Objective: To optimize the production of a target compound by screening a library of promoter variants for a key pathway gene.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation; a microbial chassis (e.g., S. cerevisiae) for production.

- Vectors: A modular cloning system (e.g., Golden Gate or EcoFlex).

- Media: Appropriate rich and selective media (e.g., LB for E. coli, YPD or synthetic complete for yeast).

- Reagents: Restriction enzymes, ligase, PCR reagents, and sequencing primers.

Procedure:

- Library Design: Select a set of native or synthetic promoters with a range of known strengths.

- Module Assembly: Use a standardized modular cloning toolkit to assemble each promoter variant upstream of the target gene's coding sequence into a destination vector containing the rest of the pathway.

- Transformation: Transform the assembled library of plasmid variants into the production chassis.

- Screening: Inoculate individual transformants in deep-well plates containing production medium.

- Fermentation: Incubate with shaking for a defined period (e.g., 72-96 hours for yeast).

- Product Quantification: Analyze the culture supernatant or cell extracts using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or LC-MS to quantify target compound titers.

- Validation: Isolate plasmids from top-performing clones and sequence the promoter region to confirm identity.

Data Interpretation: Compare the titer, yield, and productivity across the different promoter strains. The variant yielding the highest metric indicates the optimal expression level for that particular gene under the tested conditions.

Pathway Visualization: Univariate Optimization

Diagram 1: Univariate Promoter Screening. A library of promoter variants drives the expression of a single target gene (Gene X), allowing for the systematic identification of the optimal expression level that maximizes flux towards the final product through a fixed downstream pathway.

Multivariate (MMME) Strategies

Core Principle and Application Notes

Multivariate strategies, or Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering (MMME), involve the simultaneous engineering of multiple variables or modules. This approach recognizes that metabolic pathways are interconnected networks and that optimal performance requires coordinated expression of multiple genes. MMME is highly effective for balancing flux across different segments of a pathway and managing metabolic burden.

The core application is modular pathway engineering, where a full biosynthetic pathway is divided into distinct functional modules. For de novo raspberry ketone production, the pathway was split into four modules: the Aromatic amino acid synthesis module (Mod. Aro), the p-Coumaric acid synthesis module (Mod. p-CA), the Malonyl-CoA synthesis module (Mod. M-CoA), and the RK synthesis module (Mod. RK). These modules were then combinatorially assembled and expressed in different combinations to identify the optimal pathway balance. This strategy led to a strain producing 63.5 mg/L RK from glucose, the highest reported titer in yeast without precursor feeding [2].

Experimental Protocol: Modular Pathway Assembly and Testing

Objective: To maximize the production of a target compound by combinatorially assembling and testing different expression levels of functional pathway modules.

Materials:

- Strains and Vectors: As in Protocol 2.2, with pre-assembled modules for each pathway segment.

- Media: As in Protocol 2.2.

Procedure:

- Module Definition: Deconstruct the target pathway into logical modules (e.g., precursor supply, cofactor regeneration, core product synthesis).

- Module Construction: Assemble each module as a separate, standardized genetic unit (e.g., on a single plasmid or integrated at a specific genomic locus).

- Combinatorial Assembly: Use combinatorial assembly techniques (e.g., transformation-associated recombination or serial integration) to generate a library of strains containing different combinations of module expression levels (e.g., low, medium, high for each module).

- High-Throughput Cultivation: Grow the strain library in microtiter plates or microbioreactors.

- Metabolite Analysis: Use HPLC, LC-MS, or in vivo biosensors to quantify product formation and potential toxic intermediates.

- Systems Analysis: Apply multivariate data analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) to correlate module expression profiles with performance outcomes.

Data Interpretation: The best-performing strain combination reveals the optimal balance between the different pathway modules. The effect of module interactions on overall performance can be modeled to guide further engineering.

Quantitative Data for MMME: Raspberry Ketone Production

Table 1: Performance of different modular strategies for Raspberry Ketone production in S. cerevisiae [2].

| Strategy | Host | Genetic Modifications | Titer (mg/L) | Yield (mg/g glucose) | Medium/Precursor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Pathway (Monoculture) | S. cerevisiae | Mod. Aro, Mod. p-CA, Mod. M-CoA, Mod. RK | 63.5 | 2.1 | Synthetic minimal |

| Coculture (CL_RK1) | S. cerevisiae | Division of labor between community members | 6.8 (RK) / 308.4 (HBA*) | 0.34 | Synthetic minimal |

| Coculture (CL_RK3) | S. cerevisiae | Division of labor between community members | 13.3 (RK) / 280 (HBA*) | 0.67 | Synthetic minimal |

| With Precursor Feeding | S. cerevisiae | RtPAL, AtC4H, At4CL1, Pc4CL2, RpBAS | 7.5 | 0.38 | YPD + p-CA |

*HBA: 4-hydroxy benzalacetone, the direct precursor of RK.

Pathway Visualization: Multivariate Modular Engineering

Diagram 2: Multivariate Modular Pathway. A biosynthetic pathway is divided into three independent modules (Precursor Supply, Cofactor Regeneration, Product Synthesis). Each module contains genes that can be tuned in concert (e.g., via promoter libraries), enabling the balanced optimization of the entire system through combinatorial testing.

Coculture (MCE) Strategies

Core Principle and Application Notes

Coculture strategies, or Microbial Coculture Engineering (MCE), involve the use of two or more engineered microbial strains growing together in a shared environment to achieve a common bioprocessing goal. This approach leverages "division of labor," where the metabolic burden of a complex pathway is distributed among specialist strains. MCE is particularly advantageous for isolating incompatible metabolic processes, minimizing intermediate toxicity, and optimizing the local environment for different enzymatic steps.

In the context of raspberry ketone production, synthetic cocultures were constructed where one strain was specialized in producing the precursor p-coumaric acid or HBA, while another strain expressed the enzymes for the final conversion to RK. The performance was highly dependent on the community structure, inoculation ratio, and culture media. In certain conditions, cocultures outperformed their monoculture counterparts, with one community (CL_RK3) showing a 7.5-fold increase in the production of the intermediate HBA (308.4 mg/L) compared to relevant monocultures [2].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing and Optimizing a Synthetic Coculture

Objective: To implement a biosynthesis pathway using a synthetic microbial community and optimize its population dynamics for maximum production.

Materials:

- Strains: At least two engineered strains, each containing a dedicated module of the pathway.

- Media: Standard media, potentially with selective markers to maintain plasmid retention.

Procedure:

- Pathway Partitioning: Split the target biosynthesis pathway into two or more modules that can be functionally separated (e.g., upstream precursors in one strain, downstream conversion in another).

- Strain Development: Engineer individual specialist strains for each module. Ensure compatibility (e.g., pH, temperature, oxygen requirements).

- Inoculation Optimization: Co-inoculate the strains at different ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:9, 9:1) in shake flasks or bioreactors.

- Community Cultivation: Ferment the coculture system. Monitor optical density (OD) to track overall growth.

- Population Dynamics: Use flow cytometry, selective plating, or strain-specific fluorescent markers to track the population ratio of each strain over time.

- Metabolite Profiling: Quantify the target product and key intermediates in the culture broth over the fermentation period.

- Process Control: In a bioreactor, control environmental parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen) to stabilize the community.

Data Interpretation: The optimal inoculation ratio and process conditions are those that maintain a stable community and maximize the final product titer. A trade-off between individual strain growth and community productivity is often observed.

Pathway Visualization: Coculture Division of Labor

Diagram 3: Coculture Division of Labor. A biosynthetic pathway is divided between two specialist microbial strains. Strain A converts the carbon source into a key intermediate, which is then cross-fed to Strain B for final conversion into the target product. This separation can reduce metabolic burden and improve overall pathway efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and tools for implementing modular metabolic engineering strategies.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Toolkits | Standardized DNA assembly systems using Golden Gate or similar methods for combinatorial part assembly. | EcoFlex for E. coli; Golden Gate toolkits for S. cerevisiae and other yeasts [2]. |

| Promoter/RBS Libraries | Collections of genetic parts with a range of transcriptional/translational strengths for tuning gene expression. | Univariate optimization of a rate-limiting enzyme in a pathway [2]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Tools for precise genome editing, enabling targeted gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and multiplexed engineering. | Integration of metabolic modules into genomic safe harbors to enhance genetic stability [12]. |

| Biosensors | Genetic circuits that link metabolite concentration to a measurable output (e.g., fluorescence). | High-throughput screening of strain libraries for improved production of a target compound. |

| Analytical Standards | Pure chemical compounds for quantifying metabolites, products, and intermediates via HPLC or LC-MS. | Accurate measurement of raspberry ketone titers in culture supernatants [2]. |

| Specialized Chassis Strains | Engineered host organisms with pre-optimized backgrounds (e.g., precursor enrichment, reduced byproduct formation). | S. cerevisiae chassis with enhanced malonyl-CoA supply for polyketide production [2] [12]. |

The strategic application of Univariate, Multivariate (MMME), and Coculture (MCE) architectures provides a powerful, multi-faceted toolkit for advancing modular metabolic engineering. The choice of architecture depends on the complexity of the pathway, the compatibility of enzymatic steps, and the desired scale of optimization. Univariate methods offer precision for foundational tuning, MMME enables system-level balancing of complex pathways, and MCE opens the door to implementing even more complex or incompatible biochemistries through spatial and functional separation.

Future developments will focus on the integration of machine learning and automation with these architectures. AI-powered platforms can predict optimal module designs and coculture configurations, dramatically accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle [12]. Furthermore, overcoming scale-up challenges such as population stability in cocultures and metabolic burden in highly engineered monocultures will be critical for the industrial translation of these advanced strategies, paving the way for more efficient and sustainable biomanufacturing processes [12].

The Role of Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling in Pathway Design and Module Definition

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent structured knowledge-bases that systematically abstract biochemical transformations within target organisms. These computational reconstructions have become indispensable tools in systems biology, providing a biochemical, genetic, and genomic (BiGG) framework for analyzing cellular metabolism [13]. In the context of modular metabolic engineering for chemical production, GEMs serve as blueprints for identifying pathway bottlenecks, predicting metabolic fluxes, and designing optimized production chassis. By converting biological knowledge into mathematical formulations, GEMs enable researchers to simulate phenotypic characteristics under varying genetic and environmental conditions, facilitating rational strain design without extensive experimental trial and error [13] [14].

The reconstruction process transforms genomic annotations and biochemical data into stoichiometric matrices that represent the entire metabolic network of an organism. This network reconstruction forms the foundation for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA), which uses flux balance analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic behavior at systems level [13]. For metabolic engineers, this approach provides unprecedented capability to model the complex interplay between native metabolism and engineered pathways, enabling identification of key regulatory nodes and potential metabolic bottlenecks that limit chemical production. The integration of GEMs into metabolic engineering workflows has dramatically accelerated the design-build-test-learn cycle for developing microbial cell factories.

Core Principles of GEM Development and Reconstruction

The Metabolic Reconstruction Process

The development of high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstructions follows a meticulous, multi-stage process that transforms genomic information into predictive computational models. This protocol typically spans four major stages, requiring significant time investment from six months for well-studied bacteria to two years for complex eukaryotic organisms [13]. The initial stage involves creating a draft reconstruction from genomic data, identifying metabolic genes through homology searches, and mapping these genes to their corresponding enzymatic reactions using organism-specific databases and biochemical knowledge [13].

The reconstruction process progresses through several critical phases: (1) draft reconstruction generation from genome annotation; (2) manual network refinement and curation; (3) conversion to mathematical format for simulation; and (4) iterative validation and debugging against experimental data [13]. Throughout this process, quality control and quality assurance (QC/QA) procedures are essential to ensure model functionality and predictive accuracy. The manual curation phase is particularly crucial, as automated reconstructions often miss organism-specific features such as substrate preferences, cofactor specificity, and reaction directionality under physiological conditions [13]. This comprehensive approach ensures the resulting GEM accurately represents the biochemical capabilities of the target organism.

Protocol: Metabolic Network Reconstruction

Creating a Draft Reconstruction:

- Data Compilation: Collect genome sequence annotation, biochemical data from resources like KEGG and BRENDA, and organism-specific physiological information [13].

- Gene-Reaction Mapping: Associate metabolic genes with their corresponding enzymatic reactions using Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules that define protein complexes and isozymes [13].

- Compartmentalization: For eukaryotic organisms, assign intracellular localization to reactions based on prediction tools like PSORT or experimental data [15] [13].

- Biomass Composition: Define the biomass objective function quantifying cellular composition (amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, cofactors) based on experimental measurements [15] [13].

Network Refinement and Curation:

- Gap Analysis: Identify metabolic gaps (missing reactions) through network connectivity analysis and fill using biochemical literature and comparative genomics [13].

- Directionality Assignment: Assign thermodynamically feasible reaction directions using experimental data and group contribution methods [13].

- Transport Reactions: Include membrane transport processes based on genomic annotation and experimental evidence of metabolite uptake/secretion [13].

Model Validation and Testing:

- Growth Simulation: Test model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions [13].

- Gene Essentiality: Compare predicted essential genes with experimental knockout studies [13].

- Metabolite Production: Validate against known metabolic secretion profiles and byproduct formation [13].

Table 1: Essential Databases for GEM Reconstruction

| Database Type | Database Name | Primary Function | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | KEGG | Pathway information and gene annotation | www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| Genomic Databases | SEED | Comparative genomics platform | theseed.uchicago.edu/FIG/index.cgi |

| Biochemical Databases | BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme information | www.brenda-enzymes.info/ |

| Biochemical Databases | MetaCyc | Metabolic pathways and enzymes | metacyc.org |

| Organism-Specific Databases | EcoCyc | E. coli database | ecocyc.org |

| Transport Databases | Transport DB | Membrane transport systems | www.membranetransport.org/ |

| Simulation Tools | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based simulation environment | systemsbiology.ucsd.edu/Downloads/Cobra_Toolbox |

GEM Applications in Pathway Design and Optimization

Metabolic Target Identification and Validation

Genome-scale metabolic models provide a powerful framework for identifying potential targets for metabolic engineering through systematic in silico analysis. By simulating gene knockout and knockdown scenarios, GEMs can predict which genetic modifications will enhance production of desired compounds while maintaining cellular viability [16] [14]. For instance, GEMs have been successfully applied to identify gene editing targets for overproduction of immune-modulating metabolites like butyrate through bi-level optimization algorithms that simultaneously maximize product formation and cellular growth [16]. This approach enables researchers to prioritize metabolic interventions with the highest predicted impact before committing to laborious experimental work.

The predictive power of GEMs extends to forecasting the outcomes of pathway manipulations in complex metabolic networks. Recent applications include the reconstruction of iSO1949_N.oceanica, a comprehensive model of the oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica that enables simulation of metabolic fluxes under varying environmental conditions [15]. This model, specifically curated on core microalgal metabolism and lipid biosynthesis pathways, allows researchers to predict how genetic modifications will impact lipid production under different light regimes—a crucial capability for biofuel applications [15]. Similarly, GEMs have guided media optimization for fastidious microorganisms by predicting essential nutrients, as demonstrated with Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium longum [16].

Protocol: Metabolic Target Identification Using FBA

Flux Balance Analysis for Pathway Design:

- Model Constraining: Apply constraints to reflect physiological conditions, including substrate uptake rates, oxygen availability, and byproduct secretion [13] [17].

- Objective Definition: Set the optimization objective, typically biomass production for growth simulation or metabolite secretion for product formation [13].

- Gene Deletion Analysis: Systematically simulate single and double gene knockouts to identify targets that increase product yield while maintaining viability [16] [14].

- Solution Space Analysis: Use flux variability analysis (FVA) to determine the range of possible fluxes through each reaction in the network [13].

Pathway Prediction and Validation:

- Shadow Price Analysis: Identify metabolites whose availability limits production through shadow price calculations in FBA solutions [13].

- Moisty-Constrained Modeling: Track conserved metabolic moieties (e.g., ATP, NADH) to identify energy bottlenecks [13].

- In Silico Gene Overexpression: Simulate increased enzyme activity by relaxing flux constraints on target reactions [14].

- Experimental Correlation: Compare predicted essential genes, substrate utilization, and secretion profiles with experimental data for validation [13].

Table 2: GEM Applications in Metabolic Engineering

| Application Area | Specific Methodology | Key Outcome | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Gene deletion simulation | Identification of knockout targets for enhanced production | Butyrate overproduction in engineered strains [16] |

| Nutrient Optimization | Growth simulation in defined media | Prediction of essential nutrients and growth factors | Cultivation medium optimization for Bifidobacterium [16] |

| Strain Design | Constraint-based modeling | Rational design of production chassis | Lipid production in Nannochloropsis oceanica [15] |

| Condition Optimization | Environmental constraint application | Prediction of optimal growth and production conditions | Light acclimation modeling in microalgae [15] |

| Metabolic Interaction Analysis | Multi-strain community modeling | Prediction of synthetic consortium behavior | Live biotherapeutic product design [16] |

Advanced GEM Integration for Module Definition

Multi-Omics Integration and Machine Learning Approaches

The integration of multi-omics data with genome-scale metabolic models has significantly enhanced their predictive power and applications in modular metabolic engineering. Modern GEMs incorporate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create context-specific models that reflect cellular states under different conditions [17] [14]. For instance, the integration method (iMAT) uses transcriptomic data to create tissue- or condition-specific models by categorizing reaction expression levels into lowly, moderately, and highly expressed groups, then constraining the model to reflect these expression patterns [17]. This approach was successfully applied in lung cancer metabolism studies, where gene expression data from 43 paired lung tissue samples were integrated with the Human1 metabolic model to identify cancer-specific metabolic signatures [17].

Machine learning algorithms further augment GEM capabilities by identifying complex patterns in large-scale metabolic datasets. In one application, a random forest classifier distinguished between healthy and cancerous lung tissues with high accuracy based on metabolic signatures derived from GEMs [17]. Similarly, ML approaches can predict enzyme kinetic parameters, estimate flux distributions, and identify regulatory patterns that are difficult to capture through traditional constraint-based modeling alone [14]. The synergy between GEMs and machine learning creates a powerful framework for identifying metabolic modules—discrete functional units within metabolic networks that can be engineered independently—and predicting how modifications to these modules will impact overall system performance [17] [14].

Protocol: Multi-Omics Integration for Module Definition

Data Integration Workflow:

- Transcriptomic Data Mapping: Map RNA-seq data to metabolic genes using GPR rules, calculate reaction expression levels, and categorize into expression bins (low, medium, high) [17].

- Proteomic Constraints: Incorporate absolute protein abundance measurements to constrain enzyme catalytic capacities using enzyme-constrained models [14].

- Metabolomic Integration: Use intracellular metabolite concentration data to inform reaction directionality and thermodynamic feasibility [14].

- Context-Specific Model Reconstruction: Apply algorithms like iMAT or INIT to generate condition-specific models based on omics data [17].

Machine Learning Enhancement:

- Feature Selection: Use random forest or similar algorithms to identify metabolic reactions most predictive of phenotypic states [17].

- Kinetic Parameter Prediction: Train neural networks on enzyme sequence and structure data to predict kinetic parameters for poorly characterized reactions [14].

- Flux Prediction: Develop supervised learning models to predict metabolic flux distributions from multi-omics input data [14].

- Module Identification: Apply clustering algorithms to flux variability analysis results to identify correlated reaction sets and metabolic modules [17].

Application Notes: Implementing GEMs in Metabolic Engineering Projects

Case Studies in Bioprocessing and Therapeutic Development

Microalgae for Biofuel Production: The implementation of iSO1949_N.oceanica for lipid production in the oleaginous microalga Nannochloropsis oceanica demonstrates the power of GEMs in guiding photosynthetic chassis optimization. This model, extensively curated on core metabolism, lipid biosynthesis, and pigment pathways, incorporates two distinct "light acclimation modes" based on long-term acclimation to low- and high-light conditions [15]. By accounting for acclimation-specific biomass compositions, oxygen exchange rates, and maintenance requirements derived from photosynthesis-irradiance curves, the model accurately predicts carbon assimilation under varying light regimes [15]. For metabolic engineers, this capability enables rational design of lipid-overproducing strains by identifying targets in lipid biosynthesis pathways that maximize triacylglycerol yield without compromising photosynthetic efficiency.

Live Biotherapeutic Products Development: GEMs provide a systematic framework for designing and optimizing live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), as demonstrated by the screening of 43 GEMs of therapeutic microbial strains [16]. This approach enables in silico assessment of candidate strains for quality, safety, and efficacy by simulating their metabolic interactions with resident gut microbiota and host cells [16]. Through AGORA2, a resource containing 7,302 curated strain-level GEMs of gut microbes, researchers can perform top-down screening of microbes from healthy donor microbiomes or bottom-up approaches driven by predefined therapeutic objectives [16]. The GEM-guided framework allows for prediction of therapeutic metabolite production (e.g., short-chain fatty acids for inflammatory bowel disease), assessment of strain compatibility in multi-species consortia, and identification of potential adverse interactions before experimental testing [16].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM Applications

| Category | Item/Resource | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Reconstruction | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | Network reconstruction, FBA, gene deletion analysis [13] |

| Model Reconstruction | ModelSEED | Web-based platform for automated model reconstruction | Draft model generation from genome annotation [15] |

| Data Integration | iMAT Algorithm | Integration of transcriptomic data into GEMs | Context-specific model reconstruction [17] |

| Data Integration | AGORA2 Resource | 7,302 curated GEMs of gut microbes | LBP development and microbiome studies [16] |

| Simulation & Analysis | Human1 Model | Comprehensive GEM of human metabolism | Cancer metabolism studies, host-microbe interactions [17] |

| Simulation & Analysis | Random Forest Classifier | Machine learning algorithm for pattern recognition | Identification of metabolic signatures distinguishing physiological states [17] |

| Experimental Validation | CIBERSORTx | Computational tool for cell type deconvolution | Estimation of cell type-specific gene expression from bulk data [17] |

| Experimental Validation | Biolog Plates | Phenotypic microarray systems | Experimental validation of substrate utilization predictions [13] |

Protocol: Multi-Strain Community Modeling for Consolidated Bioprocessing

Community Metabolic Modeling:

- Individual Model Preparation: Curate GEMs for each strain in the proposed consortium, ensuring consistent annotation and biomass composition [16].

- Metabolic Complementarity Analysis: Simulate pairwise growth to identify potential cross-feeding relationships and metabolic dependencies [16].

- Community Model Assembly: Create a compartmentalized community model with separate metabolic networks for each strain linked through shared extracellular space [16].

- Division of Labor Design: Identify metabolic pathways that can be distributed across different strains to optimize overall community productivity [16].

Consortium Performance Optimization:

- Steady-State Analysis: Use community FBA to predict flux distributions that maximize community biomass or target metabolite production [16].

- Stability Assessment: Analyze community composition stability through dynamic FBA simulations across multiple generations [16].

- Parameter Sensitivity: Identify critical parameters (e.g., metabolite exchange rates) that significantly impact community function [16].

- Experimental Implementation: Test predicted optimal strain ratios in controlled co-culture systems and measure target metabolite production [16].

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The field of genome-scale metabolic modeling is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends poised to expand its applications in pathway design and module definition. The integration of kinetic parameters and thermodynamic constraints represents a significant frontier, addressing limitations of traditional constraint-based models [14]. Recent innovations like Metabolic Thermodynamic Sensitivity Analysis (MTSA) enable researchers to assess metabolic vulnerabilities across different physiological conditions, such as temperature variations from 36-40°C in cancer cells [17]. This approach identified impaired biomass production in cancerous mast cells across physiological temperatures, revealing temperature-dependent metabolic vulnerabilities that could be exploited for therapeutic interventions [17].

Machine learning integration with GEMs is another advancing frontier, enhancing both the reconstruction process and predictive capabilities. ML algorithms can now predict enzyme kinetic parameters, suggest network gaps, and identify optimal gene manipulation strategies from large training sets of biological data [14]. As these approaches mature, they will enable more accurate predictions of metabolic behavior in complex, non-linear regimes beyond the capabilities of traditional FBA. Furthermore, the application of GEMs in emerging biotechnological fields like cultivated meat production demonstrates their expanding relevance [18]. By adapting approaches proven in biomanufacturing (e.g., Chinese hamster ovary cell optimization), GEMs can guide the development of serum-free media and enhanced cellular engineering strategies for cultivated meat production, addressing key challenges in cost reduction and scalability [18]. These advances position GEMs as increasingly central tools in the modular metabolic engineering toolkit, enabling more predictive and efficient design of biological systems for chemical production.

From Theory to Bioproduction: Implementing Modular Strategies for Diverse Chemicals

Modular metabolic engineering (MME) represents a foundational paradigm in synthetic biology for overcoming the inherent challenges of optimizing complex biosynthetic pathways. Traditional engineering of long, multi-gene pathways in a single host often creates significant metabolic imbalances, leading to suboptimal performance due to the accumulation of intermediate metabolites, resource competition for cellular machinery, and potential toxicity issues [19] [20]. The core principle of MME is to deconstruct these complex pathways into smaller, more manageable functional units or modules. This segmentation allows for independent optimization of each module, enabling a more rational and systematic approach to balancing metabolic flux and enhancing the overall production of target chemicals [19] [20].

Two primary strategies have emerged within this framework: Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering (MMME) and Modular Coculture Engineering (MCE). MMME involves compartmentalizing different segments of a pathway within a single microbial host, typically using different genetic elements (e.g., plasmids) to control and balance the expression of each module [20]. In contrast, MCE, also known as synthetic coculture, adopts a "division-of-labor" approach by distributing different pathway modules across multiple microbial strains [19] [2]. This spatial separation can alleviate the metabolic burden on a single strain and leverage the unique physiological strengths of different organisms [19]. Both strategies are supported by an expanding toolkit of synthetic biology tools, including modular cloning, advanced genome-editing techniques like CRISPR-Cas9, and computational models, which collectively facilitate the design, construction, and optimization of these systems for the efficient production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and other valuable chemicals [19] [2] [21].

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Principles of Pathway Segmentation

The segmentation of a long biosynthetic pathway into discrete modules is not arbitrary; it follows key biological and engineering principles to maximize system performance. Effective segmentation strategically decouples competing metabolic processes, allowing independent fine-tuning of specific pathway sections. Common segmentation strategies include:

- Upstream/Downstream Module Separation: Dividing the pathway into precursor-supply modules and product-formation modules enables targeted enhancement of precursor availability without immediately creating downstream bottlenecks [19] [22].

- Core Pathway Segregation: Isolating the core product-synthesis steps allows for optimization focused specifically on the heterologous enzymes and their interactions [2].

- Cofactor Balancing Modules: Creating separate modules for managing cofactors like NADPH or ATP can resolve redox imbalances and energy issues that often constrain production [19] [22].

A critical consideration in this segmentation is the interface between modules, often referred to as the "choke point." This is the metabolic intermediate that connects two modules, and its concentration must be carefully managed. An imbalance can lead to the accumulation of a toxic intermediate or a bottleneck that starves downstream reactions [19]. In MMME, this is managed by tuning gene expression levels, while in MCE, the transport and uptake of this intermediate between different microbial populations become a key engineering parameter [19] [2].

Quantitative Metrics for Module Balancing

Successful module integration requires quantitative assessment of metabolic performance. The following table summarizes the key metrics used to evaluate and balance modular systems.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Modular Systems

| Metric | Description | Application in Module Balancing |

|---|---|---|

| Titer | Final concentration of the target product (e.g., in mg/L or g/L) [2]. | The primary indicator of overall process success and economic viability. |

| Yield | Amount of product formed per unit of substrate consumed (e.g., mg product/g glucose) [2]. | Measures pathway efficiency and carbon conservation; helps identify yield-limiting modules. |

| Productivity | Titer produced per unit of time (e.g., g/L/h) [23]. | Crucial for assessing the commercial potential of a bioprocess. |

| Metabolic Flux | The rate of metabolite conversion through a metabolic pathway [21] [22]. | Used with computational models (e.g., FBA) to identify flux bottlenecks within or between modules. |

| Energy Charge | Ratio of ATP and other adenylate phosphates [22]. | Indicates the cellular energy state; essential for balancing modules with high ATP demand. |

Beyond these standard metrics, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and LC/MS-based Systems Metabolic Profiling (SMP) are advanced techniques used to gain a deeper, systems-level understanding. For instance, SMP was instrumental in identifying a critical accumulation of inosine monophosphate (IMP) and a low ATP regeneration capacity in an L-histidine producing strain of Corynebacterium glutamicum, guiding targeted interventions to rebalance energy metabolism [22].

Performance Analysis of Modular Strategies

The application of MME strategies has led to significant improvements in the production of a diverse range of chemicals. The following table compiles quantitative data from key studies, illustrating the performance gains achieved through modular engineering.

Table 2: Performance of Modular Metabolic Engineering in Biobased Chemical Production

| Target Product | Host Organism | Modular Strategy | Key Modular Interventions | Performance Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Ketone | S. cerevisiae | MMME | Four modules: Aro, p-CA, M-CoA, RK synthesis. | 63.5 mg/L from glucose; highest yield (2.1 mg/g glucose) without precursor feeding. | [2] |

| L-Histidine | C. glutamicum | MMME | Promoter engineering of his operons; energy and C1 metabolism engineering. | Yield of 0.093 mol/mol glucose; resolved ATP and C1 supply limitations. | [22] |

| Raspberry Ketone | S. cerevisiae | MCE (Coculture) | Division of pathway across 2-3 specialist strains. | Up to 308.4 mg/L of the precursor HBA (7.5-fold increase over monoculture). | [2] |

| Terpenoids | E. coli & Plants | MMME & MCE | Module for precursor (MVA/MEP) and module for terpene synthases. | 25-fold paclitaxel increase; 38.9% artemisinin yield enhancement. | [24] |

| n-Butanol, Flavonoids | Various | MCE | Distributed pathway steps in synthetic microbial consortia. | Improved titer, rate, and yield by leveraging unique host strengths. | [19] |

The data demonstrates that both MMME and MCE are powerful and versatile strategies. The choice between them depends on the specific pathway and host constraints. MMME is often preferred for pathways with tight coupling or toxic intermediates, while MCE is advantageous when pathway steps require incompatible cellular environments or to distribute metabolic burden [19]. A prime example is the production of raspberry ketone, where a modular coculture approach achieved a dramatic 7.5-fold increase in the direct precursor, 4-hydroxy benzalacetone, highlighting the potential of division-of-labor for overcoming specific bottlenecks [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Multivariate Modular Metabolic Engineering (MMME)

This protocol outlines the process for designing, constructing, and optimizing a biosynthetic pathway using the MMME approach in a single microbial host, based on successful applications in E. coli and yeast [2] [20].

Design Phase

- Pathway Deconstruction: Divide the target biosynthetic pathway into logical modules (typically 2-4). Common divisions are:

- Upstream Module: Biosynthesis of central precursors (e.g., aromatic amino acids, malonyl-CoA).

- Midstream Module: Conversion of precursors to late-stage intermediates.

- Downstream Module: Final steps to the target product.

- Cofactor Regeneration Module: Dedicated to balancing ATP, NADPH, etc. [2] [22].

- Module Assembly: Clone the genes for each module onto separate, compatible plasmids with different copy numbers (e.g., high, medium, low) to pre-emptively vary gene dosage. Use a standardized modular cloning system (e.g., Golden Gate or EcoFlex) to facilitate the swapping of genetic parts [2] [20].

- Combinatorial Library Construction: For each gene within a module, assemble a library of expression cassettes using a range of promoters and ribosome binding sites (RBSs) of varying strengths. This creates a multivariate search space for optimal balance [2] [20].

Construction & Optimization Phase

- Strain Transformation: Co-transform the host organism with the combination of modular plasmids.

- Screening and Analysis: Screen the resulting library for product titer and yield. Use analytical methods like HPLC or LC-MS to quantify the product and key intermediates.

- Systems Analysis: For high-performing strains, employ Systems Metabolic Profiling (SMP) to quantify a wide range of intracellular metabolites. This helps identify unanticipated bottlenecks, such as the accumulation of IMP in L-histidine production [22].

- Iterative Re-balancing: Based on analytical data, refine the system. This may involve:

Diagram 1: MMME Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle

Protocol 2: Establishing a Modular Synthetic Coculture (MCE)

This protocol details the creation of a synthetic microbial consortium for distributed bioproduction, based on methods used for raspberry ketone and other chemicals [19] [2].

Design and Strain Engineering Phase

- Host Selection and Pathway Division: Choose two or more microbial species (e.g., E. coli and S. cerevisiae, or different E. coli derivatives) that are physiologically compatible. Divide the target pathway such that each host specializes in a specific module, leveraging its native metabolic strengths [19].

- Engineering Individual Specialist Strains:

- Engineer each strain with its designated pathway module.

- Ensure the first strain in the pathway can export the intermediate product that the second strain will consume.

- Engineer the second strain for efficient uptake of that intermediate.

- To stabilize the consortium, consider introducing cross-feeding dependencies for essential nutrients (e.g., amino acids) to create mutualistic interactions [19].

Coculture Optimization Phase

- Inoculation and Cultivation: Inoculate the specialist strains into a shared bioreactor. Test different inoculation ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:5, 5:1) to find the optimal starting population for balanced function [2].

- Medium Optimization: Adjust the culture medium to support the growth of all strains. This may involve balancing carbon sources or adding specific nutrients that one strain provides to the other [19] [2].

- Performance Monitoring: Monitor coculture density (e.g., by flow cytometry if strains are distinguishable), substrate consumption, and product formation over time.

- Stability Assessment: Sequence the genome of cells sampled from the coculture at different time points to check for genetic mutations that may cause instability. Use selective agents or dynamic regulation to suppress non-producing cheaters [19] [23].

Diagram 2: Synthetic Coculture with Division of Labor

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of modular metabolic engineering relies on a specific set of molecular tools and reagents. The following table catalogues key solutions for constructing and optimizing engineered modules.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Modular Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Module Design & Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Cloning Systems | Golden Gate Assembly, EcoFlex toolkit [2] [20]. | Enables rapid, modular, and combinatorial assembly of DNA parts (promoters, genes, terminators) into pathway modules. |

| Expression Plasmids | Plasmid vectors with different copy numbers (high, medium, low) and compatible replication origins [20]. | Allows simultaneous expression of multiple modules in one host and tuning of gene dosage. |

| Promoter & RBS Libraries | Synthetic promoter libraries of varying strength; RBS variant libraries [2] [21]. | Provides a genetic toolbox for fine-tuning the expression level of each gene within a module to balance flux. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPRi, MAGE [19] [20]. | Used for knocking out competing pathways, integrating modules into the genome, and dynamically regulating gene expression. |

| Biosensors | Transcription factor-based biosensors for metabolites [23]. | Enables high-throughput screening of strain libraries and implements dynamic feedback control of pathway expression. |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic standards for target product and key pathway intermediates (e.g., p-coumaric acid, HBA, IMP) [2] [22]. | Essential for accurate quantification of titer, yield, and intracellular metabolite levels during systems metabolic profiling. |

Modular metabolic engineering, through its MMME and MCE frameworks, provides a powerful and systematic methodology for overcoming the pervasive challenge of metabolic imbalance in engineered biological systems. By strategically segmenting complex pathways into functional units, researchers can more effectively manage metabolic flux, resource allocation, and inter-strain interactions. The continued development of supporting technologies—such as more robust genetic toolkits, advanced computational models, and machine learning algorithms—is poised to further enhance the precision and efficiency of module design and construction [19] [21]. As these tools mature, modular metabolic engineering will undoubtedly accelerate the development of microbial cell factories for the sustainable production of a wider array of high-value chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Within the broader framework of a thesis on modular metabolic engineering for chemical production, this case study examines the application of these principles to overcome the historical challenges in microbial L-methionine biosynthesis. L-Methionine is an essential sulfur-containing amino acid with critical roles in the food, feed, and pharmaceutical industries. Although chemical synthesis dominates industrial production, it yields a racemic mixture (D,L-methionine) and employs hazardous substrates such as methyl mercaptan, acrolein, and hydrogen cyanide, raising significant environmental concerns [25] [26]. The development of fermentative L-methionine production has been hampered by the pathway's complex regulation, strong feedback inhibition, and intricate metabolic network within the host organism, typically Escherichia coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum [27] [26]. This study details how the systematic engineering of defined metabolic modules in E. coli—specifically the terminal L-methionine synthesis module and the precursor L-cysteine module—enabled the achievement of high-yield production, providing a replicable blueprint for the microbial manufacturing of complex chemicals.

Key Engineering Strategies and Performance Data

Advanced metabolic engineering strategies have significantly pushed the boundaries of L-methionine production in E. coli. The table below summarizes the key approaches and their resulting performance metrics from recent landmark studies.

Table 1: Key metabolic engineering strategies and outcomes for L-methionine production in E. coli

| Engineering Strategy / Strain Feature | Host Strain | L-Methionine Titer (Scale) | Key Genetic Modifications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative multi-module modification | E. coli W3110 | 36.06 g/L (5-L bioreactor) | Strengthened sulfate pathway, one-carbon unit supply, and cell membrane permeability in a non-auxotrophic chassis. | [25] |

| Multivariate modular engineering | E. coli W3110 | 21.28 g/L (5-L fermenter) | Strengthened terminal module (metAfbr, metC, yjeH) and L-cysteine module (cysEfbr, serAfbr, cysDN); deleted pykA/F. | [26] [28] [29] |

| Dynamic deregulation in non-auxotrophic strain | E. coli W3110 | 17.74 g/L (5-L bioreactor) | Repaired L-lysine pathway with dynamic promoter PfliA; modified central metabolism and L-cysteine catabolism. | [30] |

| One-carbon module engineering | E. coli W3110 M2 | 18.26 g/L (5-L fermenter) | Overexpression of metF and glyA; enhanced L-homocysteine and L-cysteine supply via MalY and FliY. | [31] |

| Pathway conversion (trans- to direct-sulfurylation) | E. coli MG1655 | ~0.7 g/L (Shake flask) | Deleted metA/B; complemented with metX/metY from D. geothermalis; deleted metJ; overexpressed yjeH. | [32] |

Quantitative Impact of Modular Engineering

The stepwise improvement of L-methionine titer through specific modifications is crucial for understanding the contribution of each module. The following table quantifies the effect of individual and combined interventions in a multivariate modular engineering approach.

Table 2: Quantitative impact of modular interventions on L-methionine and byproduct accumulation in shake flask fermentation

| Engineered Strain / Intervention | L-Methionine Titer (g/L) | L-Isoleucine Accumulation (g/L) | Key Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| MET1 (Baseline) | 0.00 | - | ΔmetJ |

| MET2 | 0.58 | - | metAfbr (R27C, I296S, P298L) |

| MET4 | 0.86 | 0.61 | + Ptrc-metAfbr integration at rhtA |

| MET8 | 1.36 | 1.14 | + Ptrc-metC integration |

| MET10 | 1.93 | - | + ΔmetD, Ptrc-yjeH |

| MET13 | 2.51 | - | + ΔpykA, ΔpykF |

| MET17 (Final) | 2.95 | 0.81 | + Strengthened L-cysteine module (cysEfbr, serAfbr, cysDN) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Strengthening the L-Methionine Terminal Synthetic Module

This protocol outlines the process to engineer the core pathway from L-homoserine to L-methionine.

- Principle: To deregulate the key, feedback-inhibited step and enhance carbon flux towards L-methionine while facilitating its export from the cell.

- Materials:

- Strain: E. coli W3110 ΔmetJ (MET1).

- Plasmids & Tools: CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing, pBR322 for mutant screening.

- Culture Media: LB medium for routine cultivation; defined minimal medium (e.g., MOPS) with glucose for fermentation.

- Procedure:

- Generate a feedback-resistant MetA variant: Introduce the mutations R27C, I296S, and P298L into the chromosomal metA gene to create strain MET2 (MET1 metAfbr). This alleviates feedback inhibition by L-methionine and SAM [26].

- Enhance expression of key genes: Integrate an additional copy of the feedback-resistant metAfbr and the gene metC (cystathionine β-lyase) under the control of a strong promoter (e.g., Ptrc) into the genome, for example, at the rhtA locus, to generate strains MET4 and MET8, respectively [26].

- Engineer transport systems: Delete the L-methionine importer system (metNIQ) to prevent re-uptake. Subsequently, overexpress the exporter gene yjeH to promote extracellular accumulation, creating strain MET10 [26] [32].

- Validation: Measure L-methionine and L-isoleucine titers in shake flask fermentation using HPLC. The success of steps 1-3 is indicated by a stepwise increase in L-methionine titer from 0 g/L (MET1) to 1.93 g/L (MET10), though with significant co-accumulation of L-isoleucine [26].

Protocol 2: Engineering the L-Cysteine Synthesis Module

This protocol addresses the byproduct L-isoleucine accumulation and enhances the supply of the sulfur-containing precursor L-cysteine.

- Principle: Insufficient L-cysteine supply leads to the promiscuous activity of cystathionine γ-synthetase (MetB), which catalyzes an elimination reaction on O-succinyl-L-homoserine to form α-ketobutyrate, a precursor of L-isoleucine. Strengthening L-cysteine synthesis redirects flux back to L-methionine [26].

- Materials:

- Strain: An L-methionine producing strain with a strengthened terminal module (e.g., MET13).

- Reagents: Ammonium thiosulfate, as an efficient sulfur source.

- Procedure: