Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis: Methods, Tools, and Best Practices for Robust Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to model validation and selection for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) and flux balance analysis (FBA), essential constraint-based modeling frameworks in systems biology and metabolic...

Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis: Methods, Tools, and Best Practices for Robust Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to model validation and selection for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) and flux balance analysis (FBA), essential constraint-based modeling frameworks in systems biology and metabolic engineering. We explore foundational concepts of metabolic flux mapping, detail current methodological approaches for validating 13C-MFA and FBA predictions, address common troubleshooting challenges and optimization strategies, and present comparative analyses of validation frameworks. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances to enhance confidence in flux estimation and prediction, ultimately supporting more reliable applications in biotechnology and biomedical research.

Understanding Metabolic Flux Analysis: Core Principles and Validation Imperatives

The Critical Role of Metabolic Fluxes in Systems Biology and Biotechnology

In the multidisciplinary fields of systems biology and biotechnology, metabolic flux analysis (MFA) has emerged as a powerful methodology for quantifying the integrated functional phenotype of living systems. Metabolic fluxes represent the rates at which metabolites are converted through biochemical pathways, providing a dynamic perspective on cellular physiology that static measurements of genes, transcripts, or proteins cannot capture [1] [2]. These fluxes represent the ultimate output of complex cellular regulation and thus serve as a critical link between cellular organization and physiological function [3]. The analysis of metabolic fluxes, or "fluxomics," has become increasingly important for both basic biological discovery and biotechnological applications, from elucidating disease mechanisms to engineering microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production [4].

The growing significance of flux analysis necessitates robust validation frameworks to ensure the accuracy and biological relevance of computational models and their predictions. As metabolic modeling advances toward more complex systems and larger-scale networks, the development and application of rigorous validation methods become paramount for maintaining scientific credibility and enhancing the predictive power of these approaches [3]. This review examines the critical methodologies in metabolic flux analysis, compares their applications across biological contexts, and addresses the essential validation frameworks required for confident biological interpretation.

Methodological Landscape of Metabolic Flux Analysis

Comparative Framework of Flux Analysis Techniques

Several constraint-based modeling approaches have been developed to estimate or predict metabolic fluxes, each with distinct theoretical foundations, data requirements, and application scopes [5] [3]. The table below systematically compares the principal methodologies in current use.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Abbreviation | Labelled Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | Not Required | Required | Not Required | Genome-scale modeling, Strain design |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | Not Required | Required | Not Required | Core metabolism studies |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Required | Required | Required | Detailed flux mapping in central carbon metabolism |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | INST-MFA | Required | Required | Not Required | Systems with slow isotope equilibration |

| Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis | DMFA | Not Required | Not Required | Not Required | Transient processes, Dynamic systems |

| 13C-Dynamic MFA | 13C-DMFA | Required | Not Required | Not Required | Dynamic flux analysis with isotopic labeling |

| COMPLETE-MFA | COMPLETE-MFA | Required (multiple) | Required | Required | High-resolution flux mapping |

Among these techniques, 13C-MFA has become the gold standard for experimental flux determination in central carbon metabolism, utilizing stable isotope tracers (typically 13C-labeled substrates) to track carbon fate through metabolic networks [5]. This approach relies on feeding cells with isotopically labeled substrates, followed by measurement of the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites using mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [5]. The computational analysis of these labeling distributions allows researchers to infer the in vivo flux map that best explains the experimental data [3].

Experimental Workflow for 13C-MFA

The standard protocol for 13C-MFA involves a series of carefully orchestrated steps to ensure accurate flux determination [5]:

Cell Cultivation and Tracer Application: Cells are cultivated in a metabolic steady state, followed by replacement of the growth medium with an identical medium containing specifically chosen 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C]glucose). The system is then allowed to reach an isotopic steady state.

Metabolite Quenching and Extraction: Metabolism is rapidly quenched, typically using cold methanol, to immediately halt all enzymatic activity. Intracellular metabolites are then extracted using appropriate solvent systems.

Analytical Measurement: The labeling patterns of metabolic intermediates are measured using MS or NMR techniques. Mass spectrometry is more commonly employed due to its higher sensitivity and throughput [5].

Computational Modeling and Flux Estimation: The measured mass isotopomer distributions are integrated with a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network. Computational tools are then used to find the flux map that minimizes the difference between simulated and experimental labeling data [3] [2].

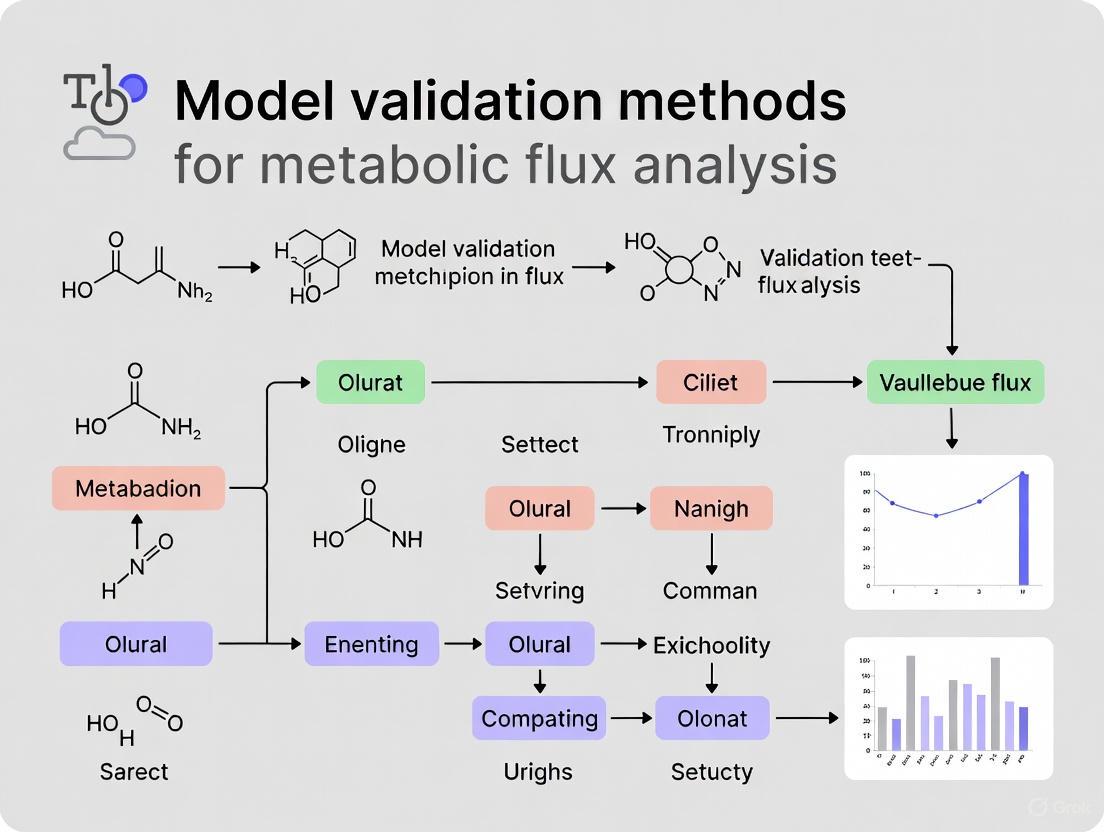

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage process and the key decision points in experimental design and data interpretation.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

Experimental Applications and Validation in Disease Research

Mitochondrial Toxicity of Environmental Contaminants

A recent investigation into the toxicological mechanisms of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in human lung cells exemplifies the power of 13C-MFA to elucidate subtle metabolic dysregulation before overt toxicity manifests [6]. Researchers exposed A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells to sub-cytotoxic concentrations of PFOA (100-300 μM) for 48 hours and employed [U-13C6]glucose as a tracer to quantify metabolic pathway activities.

Table 2: Key Metabolic Flux Changes in PFOA-Treated Human Lung Cells

| Metabolic Parameter | Experimental Finding | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability | No significant reduction at ≤300 μM PFOA | Metabolic changes precede cytotoxicity |

| TCA Cycle Flux | Significantly inhibited | Mitochondrial dysfunction identified as early toxicological target |

| Glycolytic Flux | Less affected than TCA cycle | Preferential disruption of oxidative metabolism |

| Mitochondrial ETC Activity | Impaired | Mechanism linking flux changes to functional deficit |

| Cell Cycle Progression | Dysregulated at subtoxic concentrations | Connection between metabolic and proliferative disruption |

This study demonstrated that PFOA preferentially inhibited the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle over glycolysis, identifying mitochondrial function as a sensitive toxicological target [6]. The integration of flux data with measurements of mitochondrial respiratory function revealed a coherent story of metabolic disruption, providing a robust validation of the biological significance of the measured flux changes. This approach highlights how MFA can detect metabolic dysregulation at subtoxic exposure levels, offering earlier biomarkers of chemical toxicity than traditional cytotoxicity assays.

Metabolic Reprogramming in Cell Differentiation

The application of 13C-MFA to study erythroid differentiation in K562 cells provides another compelling example of flux analysis revealing fundamental biological insights [7]. This research aimed to identify metabolic factors associated with erythroid differentiation for regenerative medicine applications. Using 13C-MFA, researchers compared flux maps before and after chemically induced differentiation and discovered a significant metabolic shift toward oxidative metabolism.

The differentiated cells showed decreased glycolytic flux and increased TCA cycle flux compared to their undifferentiated counterparts [7]. This flux redistribution was functionally significant, as demonstrated by the experimental validation showing that oligomycin-mediated inhibition of ATP synthase significantly suppressed K562 cell differentiation. This finding directly implicated the activation of oxidative metabolism as a requirement for proper erythroid differentiation, showcasing how MFA can identify metabolic checkpoints in developmental processes.

Cancer Metabolism and the Aerobic Glycolysis Paradox

A comprehensive 13C-MFA study across 12 human cancer cell lines addressed the long-standing question of why cancer cells preferentially utilize inefficient aerobic glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation for ATP regeneration—a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect [8]. The flux analysis revealed that the total ATP regeneration flux did not correlate with cellular growth rates, challenging simplistic energetic explanations for the Warburg effect.

Through integration with flux balance analysis (FBA), the researchers discovered that the measured flux distributions could be best reproduced by modeling approaches that maximize ATP consumption while considering limitations of metabolic heat dissipation [8]. This novel thermodynamic perspective was further validated experimentally through OXPHOS inhibition and low-temperature culturing, which demonstrated that cancer cells rewire their metabolic networks to maintain thermal homeostasis while meeting energy demands. This study exemplifies how multi-modal flux analysis approaches can reveal fundamental metabolic principles operating in disease states.

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Research Reagent Solutions for MFA

The experimental practice of 13C-MFA relies on specialized reagents and computational tools that enable precise tracking of metabolic fluxes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in MFA |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [U-13C6]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, 13C-CO2, 13C-NaHCO3 | Carbon tracers for metabolic pathway tracing |

| Cell Culture Media | Glucose-free RPMI-1640, Custom formulations | Controlled environment for tracer experiments |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR spectrometers | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Oligomycin, Pharmacological agents | Experimental validation of flux predictions |

| Quenching Solutions | Cold methanol | Immediate halting of metabolic activity |

| Derivatization Reagents | MtBSTFA + 1% tBDMCS, MOX, Pyridine | Chemical modification for improved MS detection |

| Computational Platforms | INCA, OpenFLUX, METRAN | Flux estimation from labeling data |

| Model Validation Tools | χ2-test of goodness-of-fit, Statistical comparison | Assessment of model fit and selection |

The selection of appropriate 13C-labeled tracers represents a critical experimental consideration, as different labeling patterns probe different metabolic pathways with varying effectiveness [5]. For central carbon metabolism, uniformly labeled [U-13C6]glucose has been widely employed, providing comprehensive information about glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle fluxes [6] [5]. The development of parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers has significantly improved flux resolution by providing complementary labeling constraints [3].

Model Validation Frameworks in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Critical Importance of Validation in Constraint-Based Modeling

Both 13C-MFA and FBA require careful validation to ensure that their predictions accurately reflect in vivo physiology. As these methods estimate rather than directly measure intracellular fluxes, validation procedures are essential for building confidence in their biological insights [3]. The χ2-test of goodness-of-fit has been the most widely used validation approach in 13C-MFA, providing a statistical measure of how well the model-derived flux map explains the experimental labeling data [3]. However, reliance on this single metric has limitations, and current best practices recommend complementary validation approaches.

Recent advances in validation methodologies include the incorporation of metabolite pool size information into the model evaluation process and the development of Bayesian techniques for characterizing uncertainties in flux estimates [3]. For FBA predictions, one of the most robust validation methods remains comparison against experimental fluxes determined by 13C-MFA, when available [3]. The integration of these multi-faceted validation strategies strengthens the biological conclusions drawn from flux studies and enhances the reliability of models for biotechnological applications.

Relationship Between Modeling Approaches and Validation Strategies

The following diagram illustrates how different flux analysis methods interrelate and the corresponding validation frameworks that ensure their biological relevance.

Figure 2: Validation frameworks for metabolic flux analysis methods

Metabolic flux analysis has matured into an indispensable methodology in systems biology and biotechnology, providing unique insights into the integrated metabolic phenotype of biological systems. The continuing development of more sophisticated analytical techniques, computational tools, and validation frameworks promises to further enhance the resolution and reliability of flux measurements. As these methods become more accessible and are applied to an expanding range of biological questions and biotechnological challenges, their role in elucidating metabolic regulation and engineering improved metabolic functions will undoubtedly grow. The critical role of metabolic fluxes as determinants and indicators of cellular physiological states ensures that flux analysis will remain at the forefront of systems biology research for the foreseeable future.

Quantifying the flow of metabolites through biochemical networks is fundamental to advancing systems biology and rational metabolic engineering. Metabolic fluxes represent an integrated functional phenotype that emerges from multiple layers of biological organization, including the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [3]. However, unlike other molecular entities, in vivo fluxes cannot be measured directly, necessitating computational approaches for their estimation or prediction [3] [9]. The two primary constraint-based frameworks addressing this challenge are 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). Both methods rely on metabolic network models operating at steady state, where reaction rates and metabolic intermediate levels are invariant [3]. While they share this foundational principle, their underlying methodologies, data requirements, and applications diverge significantly. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two powerful techniques, with a specific focus on model validation methods essential for ensuring biological relevance and prediction reliability.

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is a linear optimization approach that predicts metabolic fluxes by defining a biological objective function and solving for a flux distribution that optimizes this function, subject to stoichiometric and capacity constraints [9]. The metabolic network is mathematically represented by the stoichiometric matrix (S), which tabulates the stoichiometric coefficients for all metabolic reactions and transport processes [9]. The core assumption is that the cell has evolved to optimize a particular physiological objective, most commonly the maximization of biomass production or growth rate [3] [9]. FBA computes flux distributions by solving a linear programming problem, typically without requiring extensive experimental data beyond the network stoichiometry and constraints on external fluxes [3]. This computational tractability allows FBA to be applied to Genome-Scale Stoichiometric Models (GSSMs) that incorporate all known reactions believed to occur in an organism [3]. Several related methods extend the FBA framework, including Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) and Regulatory On/Off Minimization (ROOM), as well as techniques that incorporate various types of omic data [3].

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

In contrast to FBA, 13C-MFA is a model-based estimation technique that infers intracellular fluxes by fitting a metabolic network model to experimental data obtained from 13C-labeling experiments [3] [9]. Cells are fed substrates containing stable 13C isotopes, and the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured using mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [3] [10]. These labeling patterns, known as Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs), depend on the specific pathways active within the cell and the fluxes through them [11]. 13C-MFA works by minimizing the differences between measured MIDs and those simulated by the model by varying the flux estimates [3]. This approach does not assume an optimization principle for cellular behavior but rather identifies fluxes that are most consistent with the empirical labeling data [9]. While traditionally applied to central carbon metabolism, 13C-MFA is considered the gold standard for flux quantification due to its strong empirical foundation [9] [12].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of 13C-MFA and FBA

| Aspect | 13C-MFA | FBA |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Estimation from experimental isotopic labeling data | Prediction via optimization of a biological objective function |

| Data Requirements | High (13C-labeling data, extracellular fluxes) | Low (Stoichiometry, constraints, objective function) |

| Mathematical Basis | Nonlinear regression/optimization | Linear programming |

| Typical Network Scale | Core metabolic networks (dozens to hundreds of reactions) | Genome-scale networks (thousands of reactions) |

| Key Assumption | Metabolic and isotopic steady state | Steady state and optimal cellular performance |

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of FBA and 13C-MFA. FBA (green) is a prediction-first approach driven by network constraints and optimization, while 13C-MFA (blue) is an estimation-first approach driven by experimental isotopic labeling data. Both output a flux map (red) representing reaction rates through the metabolic network.

Model Validation and Selection Frameworks

Validation Methods for FBA Predictions

Validating flux predictions from FBA presents unique challenges since the true intracellular fluxes are unknown. The most robust validation involves direct comparison against experimental flux data, ideally obtained from 13C-MFA studies [3]. This comparative approach assesses how well the FBA-predicted fluxes, based on optimality assumptions, align with empirically determined fluxes. Other important validation strategies include:

- Comparison against 13C-MFA fluxes: This serves as the most authoritative method for testing the accuracy of FBA predictions [3].

- Evaluation of alternative objective functions: Different biological objectives (e.g., maximizing ATP yield, minimizing nutrient uptake) should be evaluated to identify those yielding predictions that best match experimental data [3] [9].

- Flux variability analysis: This technique characterizes the range of possible fluxes within the constrained solution space, providing insight into the flexibility and uniqueness of the predicted flux distribution [3].

- Genetic perturbation validation: Comparing predicted flux changes (e.g., using MOMA) with measured physiological changes following gene knockouts provides a functional test of model predictions [3] [9].

Validation and Selection for 13C-MFA

In 13C-MFA, validation primarily focuses on assessing the goodness-of-fit between the model simulations and the experimental labeling data, and selecting the most appropriate model structure from competing alternatives [3] [11].

- χ²-test of goodness-of-fit: This is the most widely used quantitative validation approach. It tests whether the differences between measured and simulated data are statistically significant given the measurement errors [3] [11]. A model is typically considered valid if the χ²-statistic is below a critical threshold corresponding to a chosen confidence level (e.g., 95%).

- Limitations of the χ²-test: This test can be problematic when measurement errors are inaccurately estimated, which occurs frequently. Errors may be underestimated due to instrumental bias or overestimated due to unaccounted-for experimental bias [11]. This can lead to either rejecting valid models or accepting overfitted ones.

- Validation-based model selection: A more robust approach uses independent validation data not used during model fitting. This method selects the model that best predicts new labeling experiments, protecting against overfitting and being less sensitive to errors in measurement uncertainty estimates [11].

- Flux confidence intervals: Determining statistical confidence intervals for estimated fluxes through parameter bootstrap sampling or monte carlo approaches is a crucial part of validation, quantifying the uncertainty in flux estimates [3] [10].

Table 2: Model Validation and Selection Techniques

| Method | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ²-test of goodness-of-fit | 13C-MFA model validation | Standardized statistical framework; Widely implemented in software | Sensitive to inaccurate error estimates; Can promote overfitting |

| Validation-based selection | 13C-MFA model selection | Robust to measurement error uncertainty; Reduces overfitting | Requires additional labeling experiments; More computationally intensive |

| Flux confidence intervals | Both 13C-MFA and FBA | Quantifies uncertainty in flux estimates; Identifies well-constrained fluxes | Computationally demanding for large networks |

| Comparison to 13C-MFA data | FBA prediction validation | Provides empirical test of predictive accuracy | 13C-MFA data not always available |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | FBA solution space analysis | Characterizes alternative optimal solutions; Identifies flexible nodes | Does not directly validate accuracy |

Experimental Design and Protocols

Key Experimental Protocols

13C Tracer Experiment Design for 13C-MFA

The accuracy of 13C-MFA heavily depends on the careful design of tracer experiments. Key considerations include:

- Tracer Selection: The choice of 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) determines which pathways can be resolved. Parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers provide significantly more flux information than single tracer studies [3] [10].

- Isotopic Steady State: For traditional 13C-MFA, cells must be harvested at isotopic steady state, where labeling patterns no longer change with time [9]. This typically requires multiple cell divisions in the presence of the labeled substrate.

- Measurement Techniques: Mass isotopomer distributions are most commonly measured via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS). Tandem mass spectrometry can provide positional labeling information, improving flux resolution [3] [10].

- Data Collection: Best practices require reporting uncorrected mass isotopomer distributions in tabular form with standard deviations, along with the measured isotopic purity of tracers [10].

Experimental Constraints for FBA

While FBA requires less experimental data than 13C-MFA, its predictions benefit greatly from physiologically relevant constraints:

- Extracellular Flux Measurements: Quantifying substrate uptake rates, product secretion rates, and growth rates constrains the solution space [9].

- Biomass Composition: Accurate determination of macromolecular cellular composition (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, DNA, RNA) improves predictions when maximizing biomass is the objective [3].

- Gene Essentiality Data: Data on which gene knockouts are lethal or non-lethal provides valuable validation of model predictions [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon sources with specific positional 13C enrichment; Creates measurable labeling patterns in metabolites | 13C-MFA |

| Isotopic Standard Mixtures | Calibration of mass spectrometry instruments; Verification of labeling measurements | 13C-MFA |

| Chemically Defined Media | Precisely controlled nutrient environment; Essential for accurate extracellular flux measurements | Both 13C-MFA and FBA |

| Stoichiometric Genome-Scale Model | Computational representation of metabolic network; Contains all known biochemical reactions | FBA |

| Core Metabolic Network Model | Simplified model focusing on central carbon metabolism; Includes atom transition information | 13C-MFA |

| Specialized Software | Tools for flux estimation (13C-MFA) or optimization (FBA); Enables data interpretation | Both 13C-MFA and FBA |

Applications and Comparative Performance

Strengths and Limitations in Practice

The choice between 13C-MFA and FBA depends heavily on the research question, available resources, and desired outcome.

13C-MFA excels when:

- High quantitative accuracy of fluxes in core metabolism is required [9].

- Validating or refuting the activity of specific pathways or cycles [10].

- Studying non-model organisms where optimality assumptions may not hold [9].

- Characterizing metabolic perturbations where the objective function may shift [3].

FBA is more suitable for:

- Genome-scale analyses encompassing secondary metabolism [3].

- Predictive studies where experimental labeling data is unavailable [9].

- High-throughput screening of genetic modifications in metabolic engineering [3].

- Integrating multi-omic data to contextualize transcriptomic or proteomic measurements [3].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The fields of 13C-MFA and FBA continue to evolve with several promising directions:

- Integrated validation frameworks: New approaches combining metabolite pool size information with labeling data are being developed to improve model selection in 13C-MFA [3].

- Machine learning integration: Both fields are beginning to incorporate machine learning to improve prediction accuracy and identify patterns in large-scale flux datasets [9].

- Single-cell and microbial community applications: Novel methods like peptide-based 13C-MFA are enabling flux analysis in microbial communities by using peptide labeling patterns that can be attributed to specific species [12].

- Uncertainty quantification: Enhanced methods for characterizing uncertainty in both FBA predictions and 13C-MFA estimates are increasing confidence in model-derived conclusions [3] [11].

Both 13C-MFA and FBA are powerful constraint-based modeling frameworks that provide unique insights into metabolic function. 13C-MFA stands as the gold standard for empirical flux quantification, offering high accuracy in core metabolism but requiring substantial experimental effort. FBA provides a genome-scale predictive framework based on optimality principles, requiring minimal experimental input but potentially sacrificing quantitative accuracy. Robust model validation is essential for both approaches—whether through statistical tests against labeling data for 13C-MFA or through comparison with empirical fluxes for FBA. The emerging trend of validation-based model selection promises to enhance the reliability of 13C-MFA, while continued efforts to integrate diverse experimental data will improve FBA predictions. For the research and drug development professional, the choice between these methods should be guided by the specific biological question, the scale of metabolism under investigation, and the availability of experimental resources.

Why Model Validation and Selection Matter for Reliable Flux Predictions

The Critical Role of Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Metabolic flux analysis, comprising techniques like 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), provides crucial insights into the operational capabilities of metabolic networks in living systems [3]. These computational methods estimate or predict in vivo reaction rates (fluxes) that cannot be measured directly, serving essential roles in basic biological research, metabolic engineering, and biotechnology [3] [13]. However, the reliability of these flux predictions hinges critically on appropriate model validation and selection practices—areas that have been historically underappreciated in the field [3] [14]. Without robust validation procedures, researchers risk drawing conclusions based on inaccurate flux maps that poorly reflect biological reality, potentially misdirecting scientific understanding and engineering efforts.

The core challenge stems from the inherent indirect nature of flux determination. Both 13C-MFA and FBA use metabolic network models operating at steady state and require researchers to make choices about network structure and composition [3]. Model validation provides the necessary checks to ensure these choices yield predictions faithful to the biological system under study, while model selection offers statistical justification for choosing one model architecture over competing alternatives [3] [11].

Model Validation Methods: Comparing 13C-MFA and FBA Approaches

Validation techniques differ substantially between 13C-MFA and FBA, reflecting their distinct theoretical foundations and data requirements.

Validation in 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C-MFA works by fitting a metabolic network model to experimental mass isotopomer distribution (MID) data obtained from isotope labeling experiments [3] [11]. The primary validation method has historically been the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, which statistically assesses whether the differences between measured and model-predicted MID values are likely due to random measurement error [3] [11]. When a model passes this test (typically at a 5% significance level), it is considered statistically acceptable [11].

However, this approach faces several limitations that researchers must recognize:

- Error Model Accuracy: The χ²-test depends on accurate estimates of measurement uncertainties, which are often difficult to determine precisely and may not account for all sources of experimental bias [11].

- Network Structure Dependence: The test validates how well a specific model structure fits the data but cannot confirm whether the model structure itself is biologically correct [11].

- Multiple Testing Issues: During iterative model development, researchers may test multiple structures using the same dataset, increasing the risk of eventually finding a structure that passes the χ²-test by chance [11].

Validation in Flux Balance Analysis

FBA predicts fluxes through linear optimization of an objective function (such as growth rate maximization) within a constrained solution space [3] [14]. Unlike 13C-MFA, FBA does not inherently fit experimental data, leading to more varied validation approaches:

Table 1: Validation Methods for Flux Balance Analysis

| Validation Method | What It Tests | Key Limitations | Appropriate Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth/No-Growth on Substrates [14] | Presence/absence of metabolic routes for substrate utilization | Qualitative only; does not test accuracy of internal flux values | When viability under different conditions is the primary interest |

| Growth Rate Comparisons [14] | Consistency of network with observed biomass synthesis efficiency | Uninformative regarding accuracy of internal flux predictions | When overall growth efficiency across multiple conditions is relevant |

| Comparison with 13C-MFA Fluxes [3] | Agreement between predicted and MFA-estimated internal fluxes | Requires additional experimental data collection | Most rigorous validation when MFA data is available |

| MEMOTE Quality Control [14] | Basic model functionality and stoichiometric consistency | Does not validate context-specific predictions | Essential first-step model quality assurance |

Quality control pipelines like MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) provide important initial validation of basic model functionality, ensuring that models cannot generate energy without substrates or synthesize biomass without required nutrients [14]. However, these basic checks do not validate the accuracy of context-specific flux predictions, for which comparison with experimental 13C-MFA fluxes remains the gold standard [3].

Model Selection Strategies: Moving Beyond Traditional Practices

Model selection addresses the critical question of which metabolic network structure—including specific reactions, compartments, and metabolites—is most statistically justified given available data.

The χ²-Test Approach and Its Limitations

Traditional model selection in 13C-MFA often involves an iterative process where model structures are successively modified and tested against the same dataset until one passes the χ²-test [11]. This approach is problematic because it uses the same data for both model fitting and selection, potentially leading to either:

- Overfitting: Selecting an overly complex model that fits noise in the estimation data, resulting in poor predictive performance [11]

- Underfitting: Selecting an overly simple model that misses key biological mechanisms [11]

The problem is compounded by uncertainty in measurement errors, which directly influences χ²-test outcomes and can lead researchers to select different model structures depending on their error estimates [11].

Advanced Model Selection Methods

Recent methodological developments offer more robust approaches to model selection:

Validation-Based Model Selection: This approach uses independent validation data not used during model fitting, choosing the model that best predicts this new data [11] [15]. Simulation studies demonstrate this method consistently selects the correct model structure regardless of measurement uncertainty estimates [11].

Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA): This framework addresses model uncertainty by combining flux estimates across multiple plausible models, weighted by their statistical support [16]. BMA acts as a "tempered Ockham's razor," automatically balancing model complexity and fit without overpenalizing either [16].

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA): This method integrates enzyme expression data at the pathway level to predict flux changes, striking an optimal balance between reaction-specific and whole-network approaches [17].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in validation-based model selection:

Comparative Performance: Quantitative Assessments of Validation and Selection Methods

Validation-Based vs. χ²-Test Model Selection

A systematic comparison of model selection approaches reveals significant differences in performance, particularly under realistic conditions of uncertain measurement error:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Model Selection Methods in 13C-MFA

| Selection Method | Dependence on Measurement Error Estimates | Risk of Overfitting | Robustness to Error Model Misspecification | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional χ²-test [11] | High - different error estimates lead to different selected models | High - particularly with iterative testing on same data | Low - highly sensitive to inaccurate error estimates | Low - widely implemented in MFA software |

| Validation-Based Approach [11] [15] | Low - consistent model selection regardless of error estimates | Low - protected by independent validation data | High - maintains performance even with poor error estimates | Medium - requires additional validation experiments |

| Bayesian Model Averaging [16] | Medium - incorporates uncertainty but depends on prior specifications | Low - naturally balances model fit and complexity | Medium - depends on appropriateness of priors | High - requires specialized statistical expertise |

Validation-based model selection demonstrates particular strength in its independence from measurement uncertainty estimates, a significant advantage since true measurement errors can be difficult to determine precisely in practice [11]. In one isotope tracing study on human mammary epithelial cells, this approach successfully identified pyruvate carboxylase as a key model component that might have been missed using traditional methods [11].

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis Performance

The enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) algorithm represents a significant advance in predicting flux changes from enzyme expression data. By integrating expression data at the pathway level rather than focusing on individual reactions or the entire network, eFPA achieves optimal predictive performance [17].

The following diagram illustrates the eFPA algorithm workflow and its key innovation of pathway-level integration:

When evaluated against experimental flux data from yeast, eFPA demonstrated superior performance in predicting relative flux levels compared to methods focusing solely on individual reactions or employing whole-network integration [17]. This approach also proved effective with human tissue data, generating consistent predictions using either proteomic or transcriptomic datasets, and handled the sparsity and noisiness of single-cell RNA-seq data robustly [17].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Model Validation

Implementing rigorous model validation requires careful experimental design and execution. The following protocols detail key methodologies cited in the literature.

Protocol for Validation-Based Model Selection in 13C-MFA

This protocol adapts the methodology described by Sundqvist et al. (2022) for implementing validation-based model selection [11] [15]:

Experimental Design Phase

- Plan two independent isotope labeling experiments: one for estimation (training) and one for validation

- Ensure validation experiments have neither too much nor too little novelty compared to estimation data

- Use different tracer substrates or tracer mixtures to provide complementary information

Data Collection Phase

- For each experiment, measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for target metabolites

- Quantify technical and biological variability to estimate measurement uncertainties

- Record external fluxes (substrate uptake, product secretion, growth rates)

Model Selection Phase

- Develop multiple candidate model structures based on biological knowledge

- Fit each candidate model to the estimation dataset

- Test each fitted model's predictive performance on the validation dataset

- Select the model that minimizes prediction error on validation data

Validation Assessment Phase

- Quantify prediction uncertainty using appropriate statistical methods

- Verify that selected model provides biologically plausible flux estimates

- Perform additional checks for identifiability and parameter uncertainty

Protocol for Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis

This protocol outlines the implementation of eFPA for predicting flux changes from enzyme expression data, based on the methodology optimized using yeast data [17]:

Data Preparation

- Obtain paired datasets of enzyme levels (proteomic or transcriptomic) and metabolic fluxes

- Adjust flux values for growth rate variations by dividing flux by the specific growth rate

- Map enzyme expression data to corresponding metabolic reactions in a genome-scale model

Parameter Optimization

- Systematically test different distance parameters controlling network neighborhood size

- Identify optimal pathway scope for integrating expression data

- Validate parameters using known flux-enzyme expression relationships

Flux Prediction

- For each reaction of interest, integrate expression levels of enzymes in its pathway neighborhood

- Apply distance-weighted integration, giving more influence to closer reactions

- Calculate flux potential scores representing predicted relative flux changes

Validation and Application

- Compare predicted flux changes with experimentally measured fluxes

- Apply to new datasets (e.g., human tissue proteomics or single-cell transcriptomics)

- Use optimized parameters for robust predictions across different biological contexts

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing robust validation and selection procedures requires specific experimental and computational resources. The following table details key solutions used in the cited research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Flux Analysis Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates [13] [11] | Biochemical reagent | Tracing metabolic pathways via isotopic labeling | 13C-MFA estimation and validation experiments |

| Mass Spectrometry [3] [11] | Analytical instrument | Quantifying mass isotopomer distributions | Measuring MID data for model fitting and validation |

| COBRA Toolbox [14] | Software package | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA model implementation and basic validation |

| MEMOTE Pipeline [14] | Quality control suite | Testing metabolic model functionality | Initial validation of FBA model stoichiometry and consistency |

| Bayesian MFA Framework [16] | Statistical software | Bayesian flux estimation and model averaging | Multi-model inference and model selection uncertainty quantification |

| eFPA Algorithm [17] | Computational method | Predicting flux changes from expression data | Integrating omics data for flux prediction validation |

Model validation and selection are not mere statistical formalities but fundamental components of rigorous metabolic flux analysis. The continuing development and adoption of robust methods like validation-based model selection, Bayesian Model Averaging, and enhanced Flux Potential Analysis represent significant advances over traditional practices [16] [11] [17]. These approaches systematically address critical limitations of conventional methods, particularly their susceptibility to measurement error miscalibration and model selection bias.

As the field progresses, the integration of diverse data types—from isotope labeling patterns to enzyme expression levels—coupled with sophisticated statistical frameworks will further enhance the reliability of flux predictions [17] [18]. This methodological evolution promises to strengthen confidence in constraint-based modeling outcomes, ultimately supporting more informed biological discoveries and more effective metabolic engineering strategies [3]. For researchers seeking to implement these approaches, beginning with validation-based model selection for 13C-MFA and pathway-level integration of expression data for FBA provides a robust foundation for generating biologically meaningful flux predictions.

Key Challenges in Estimating In Vivo Fluxes That Cannot Be Directly Measured

Quantifying the rates of biochemical reactions, known as metabolic fluxes, is fundamental to understanding cellular physiology in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to drug development. A central paradox in this endeavor is that in vivo metabolic fluxes cannot be measured directly [3] [14]. Instead, researchers must infer them through a combination of experimental data and computational models, primarily using two constraint-based frameworks: 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [3] [14]. Both methods rely on metabolic network models operating at steady state, where reaction rates and metabolic intermediate levels are invariant [3] [14]. The reliability of these estimated or predicted fluxes hinges entirely on the robustness of model validation and selection procedures—a area that remains underappreciated and underexplored in metabolic modeling [3] [14] [11]. This guide examines the key challenges in flux estimation, comparing methodological approaches through the critical lens of model validation.

Core Methodologies for Flux Estimation

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA works by feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates and measuring the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites using mass spectrometry or NMR techniques [3] [14]. The computational process then works backward: "by minimizing the differences between measured and estimated Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) values by varying flux estimates" [3]. This approach provides estimated values of intracellular fluxes based on experimental labeling data [3] [14]. For complex systems where all labeled atoms effectively originate from a single source pool, such as in autotrophic plant metabolism or nitrogen labeling experiments, Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) becomes necessary, utilizing time-resolved labeling data before the system reaches isotopic equilibrium [19].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

In contrast to 13C-MFA, FBA uses linear optimization to identify flux maps that maximize or minimize a defined objective function, such as biomass production or ATP yield [3] [14]. This method requires a metabolic network structure but typically utilizes less experimental data, enabling the analysis of genome-scale models [3]. FBA provides predicted flux values based on assumed cellular objectives rather than direct experimental measurement of labeling patterns [3] [14]. Related methods like Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) and Regulatory On/Off Minimization (ROOM) extend the FBA framework to account for regulatory effects [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Flux Estimation Methodologies

| Feature | 13C-MFA | FBA |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | 13C-labeling data, extracellular fluxes | Stoichiometric model, constraints (often extracellular fluxes) |

| Computational Basis | Non-linear optimization fitting labeling patterns | Linear optimization of objective function |

| Flux Output | Estimated fluxes (based on experimental data) | Predicted fluxes (based on optimization principle) |

| Model Scale | Typically core metabolism | Genome-scale possible |

| Key Assumption | Metabolic and isotopic steady state (except INST-MFA) | Metabolic steady state, evolution toward optimality |

Workflow Relationship Between Methods

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different flux estimation approaches and where validation challenges occur:

Critical Challenges in Model Validation and Selection

Statistical Limitations in 13C-MFA Validation

The most widely used quantitative validation approach in 13C-MFA is the χ2-test of goodness-of-fit, which evaluates how well model-simulated labeling patterns match experimental data [3] [11]. However, this method faces several critical limitations that can compromise flux reliability:

Dependence on accurate error estimation: The χ2-test requires accurate knowledge of measurement errors, which is often difficult to determine in practice [11]. Standard deviations from biological replicates may not account for all error sources, including analytical bias or deviations from metabolic steady-state [11].

Circularity in model selection: Models are often developed iteratively using the same dataset for both fitting and validation, increasing the risk of overfitting [11]. As noted by Sundqvist et al., "model selection is often done informally during the modelling process, based on the same data that is used for model fitting (estimation data). This can lead to either overly complex models (overfitting) or too simple ones (underfitting)" [11].

Uncertainty in parameter identifiability: Correct application of the χ2-test requires knowing the number of identifiable parameters, which is challenging to determine for nonlinear MFA models [11].

Robustness of FBA Predictions

Validating FBA predictions presents distinct challenges, primarily centered on the selection of appropriate objective functions and the integration of experimental constraints:

Objective function justification: "Since the objective function, together with the network architecture and empirical and/or theoretical constraints introduced by the modeler, is a key determinant of the flux maps generated by FBA, careful selection, justification, and, ideally, validation of objective functions is crucial" [3]. Different hypotheses about cellular objectives can yield dramatically different flux predictions.

Qualitative vs. quantitative validation: Many FBA validations focus on qualitative predictions, such as whether a model correctly predicts growth or no-growth on specific substrates [14]. As noted in the literature, "Validation is qualitative, only indicating the existence of metabolic routes. Does not test the accuracy of predicted internal flux values" [14].

Integration of omics data: While methods exist to incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data into FBA frameworks, these introduce additional layers of uncertainty regarding how well mRNA or protein levels reflect actual metabolic flux [3] [14].

Computational and Experimental Limitations

Global optimization challenges: In 13C-MFA, the flux calculation problem becomes a non-convex optimization problem that may have multiple local minima [20]. As highlighted by Ghosh et al., "none of the currently available algorithms for MFA calculation guarantees that a global minimum is found at the end of the procedure, due to the non-convex nature of the feasible region" [20].

Data completeness requirements: Methods like Dynamic Flux Estimation (DFE) require "more or less complete time series data" and systems with "as many independent fluxes as metabolites" to avoid underdetermination [21]. Most real pathway systems contain more fluxes than metabolites, creating inherent mathematical challenges.

Time-scale disparities: In INST-MFA, large-scale networks contain metabolites with dramatically different labeling time scales, creating numerical difficulties in fitting a unified model [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Validation Approaches and Their Limitations

| Validation Method | Application Context | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2-test of goodness-of-fit | 13C-MFA model selection | Standardized statistical framework | Sensitive to error estimation; promotes overfitting [11] |

| Validation-based model selection | 13C-MFA with independent data | Robust to measurement error uncertainty; prevents overfitting [11] | Requires additional experimental data |

| Growth/no-growth comparison | FBA model validation | Simple to implement; qualitative assessment | Does not test accuracy of internal flux values [14] |

| Flux comparison with 13C-MFA | FBA prediction validation | Provides quantitative assessment of internal fluxes | 13C-MFA itself has estimation uncertainties [3] |

| MEMOTE tests | FBA model quality control | Comprehensive stoichiometric consistency checks | Does not validate context-specific predictions [14] |

Advanced Model Selection Frameworks

Validation-Based Model Selection for 13C-MFA

To address limitations of traditional χ2-testing, Sundqvist et al. propose a validation-based model selection approach that uses independent datasets for model training and validation [11]. This method:

Leverages separate validation data: "Using an adopted approach to calculate the uncertainty of model predictions, we identify new validation experiments, which are neither too similar, nor too dissimilar, compared to the previous training data" [11].

Reduces sensitivity to error estimation: "Tests on simulated data where the true model is known, shows that the validation-based method is robust when the magnitude of the error in the measurement uncertainty is unknown, something that conventional methods are not" [11].

Provides practical implementation: The authors demonstrate application to human mammary epithelial cells, where the method "identified pyruvate carboxylase as a key model component" [11].

Incorporation of Metabolite Pool Size Information

Recent advances propose combining metabolite pool size measurements with labeling data for improved model selection [3] [14]. This approach is particularly valuable in INST-MFA, where "pool size measurements can also be included in the minimization process" [3] [14]. The integration of pool size data provides additional constraints that can help resolve flux ambiguities and select more biologically plausible models.

Local vs. Global INST-MFA Approaches

For isotopically nonstationary MFA, methods can be categorized as global or local approaches, each with distinct advantages for model validation:

Global INST-MFA: Simultaneously estimates all identifiable fluxes in a network but faces computational challenges with large networks and can suffer from numerical instabilities [19].

Local INST-MFA approaches (Kinetic Flux Profiling, NSMFRA, ScalaFlux): Estimate fluxes for specific sub-networks or reactions, requiring less data and being computationally more tractable [19]. As noted in a systematic comparison, "local approaches for INST-MFA, that only estimate the flux of a specific reaction or a subset of reactions in a sub-network, circumvent these issues due to the much smaller size of the resulting computational problems" [19].

The following diagram illustrates the model selection and validation workflow for robust flux estimation:

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

Parallel Labeling Experiments for Enhanced 13C-MFA Precision

Protocol Objective: To increase the precision and reliability of flux estimates through multiple isotopic tracers.

Detailed Methodology:

- Design of tracer combinations: Utilize multiple 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, and [1,2-13C]glucose) in parallel experiments [3].

- Cultivation conditions: Maintain metabolic steady state through chemostat cultivation or carefully controlled batch conditions [3] [20].

- Mass isotopomer measurement: Quench metabolism rapidly and extract intracellular metabolites for GC-MS or LC-MS analysis [11].

- Data integration: "Simultaneously fit [results] to generate a single 13C-MFA flux map" rather than analyzing tracers separately [3].

- Statistical evaluation: Apply validation-based model selection using one tracer combination as estimation data and another as independent validation data [11].

Expected Outcomes: "This enables more precise estimation of fluxes than experiments with individual tracers or tracer combinations allow" [3].

Cross-Validation Between FBA and 13C-MFA

Protocol Objective: To leverage 13C-MFA as validation for FBA predictions.

Detailed Methodology:

- 13C-MFA reference fluxes: Establish a set of core metabolic fluxes using rigorous 13C-MFA with validation-based model selection [11].

- FBA model calibration: "Alternative objective functions can, and should, be evaluated to identify those that result in the best agreement with experimental data" [3].

- Constraint refinement: Adjust FBA constraints based on 13C-MFA flux estimates to improve predictive accuracy for unmeasured fluxes [3].

- Predictive testing: Validate the calibrated FBA model against 13C-MFA data from different genetic or environmental conditions [3].

Expected Outcomes: "One of the most robust validations that can be conducted for FBA predictions is comparison against MFA estimated fluxes" [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Flux Estimation Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks | 13C-MFA and INST-MFA experiments [3] [19] |

| Mass spectrometry platforms | Quantifying mass isotopomer distributions | Measurement of labeling patterns for MFA [3] [11] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA simulation and model validation [14] |

| INCA software | Integrated metabolic flux analysis | INST-MFA implementation [19] |

| MEMOTE test suite | Metabolic model testing | Quality control for FBA model stoichiometry [14] |

| Global optimization algorithms | Solving non-convex MFA problems | Robust flux estimation [20] |

Estimating in vivo fluxes presents fundamental challenges centered on the indirect nature of flux measurements and the critical importance of robust model validation. The key challenges include: (1) the statistical limitations of goodness-of-fit tests like the χ2-test in 13C-MFA; (2) the subjectivity in objective function selection for FBA; (3) the computational difficulties in achieving global optimization solutions; and (4) the experimental constraints in obtaining comprehensive labeling data. Advances in validation-based model selection that utilize independent datasets [11] and integration of metabolite pool sizes with labeling data [3] [14] represent promising paths toward more reliable flux estimation. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these robust validation practices is essential for generating metabolic insights that can reliably inform engineering and therapeutic strategies.

Validation in Practice: Methodological Approaches for 13C-MFA and FBA

The χ2-test of goodness-of-fit serves as a fundamental statistical tool in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) for validating how well a candidate metabolic model explains experimental isotopic labeling data [11] [14]. This review delineates the precise application of this test within the 13C-MFA workflow and critically examines its significant limitations, including a pronounced sensitivity to measurement error estimates and a propensity to promote overfitting during model selection [11]. Furthermore, we present emerging alternative validation strategies, such as validation-based model selection and the integration of metabolite pool size data, which offer more robust frameworks for model discrimination and enhance the reliability of flux estimations in metabolic research [11] [14] [3].

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a cornerstone technique for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity in various biological systems, from microbes to mammalian cells [22]. By tracing the incorporation of 13C-labeled substrates into intracellular metabolites, researchers can infer reaction rates (fluxes) that define the functional metabolic state of an organism [22] [23]. The process relies on fitting a mathematical model of the metabolic network to experimental mass isotopomer distribution (MID) data [14] [3]. A critical yet often underappreciated step in this process is model validation—determining whether the proposed metabolic network and estimated fluxes provide a statistically acceptable fit to the empirical data. The χ2-test of goodness-of-fit has been the traditional tool for this purpose [14] [3]. However, its application in 13C-MFA involves specific assumptions and challenges that, if unaddressed, can compromise the accuracy and biological relevance of the resulting flux map. This article examines the role of this test, its limitations, and the advanced methodologies that are shaping the future of model validation in flux analysis.

The Role of the χ2-Test in the 13C-MFA Workflow

In 13C-MFA, the χ2-test is employed as a formal statistical check at the culmination of the flux estimation procedure. The following workflow diagram illustrates the central role of this test.

The core of the test involves comparing the experimentally observed MIDs with those simulated by the metabolic model. The test statistic (χ²) is calculated as:

[ \chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O{i} - E{i})^2}{\sigma_{i}^2} ]

Where ( O{i} ) is the observed MID data, ( E{i} ) is the model-simulated expectation, and ( \sigma_{i} ) is the standard deviation of the measurement [11] [14]. This statistic measures the weighted sum of squared differences between the model and the data. The model is typically considered an acceptable fit if the χ² value is below a critical threshold from the χ² distribution, with degrees of freedom equal to the number of independent labeling measurements minus the number of estimated parameters [14] [3].

Table 1: Key Components of the 13C-MFA χ2-Test

| Component | Description | Role in χ2-Test |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) | Measured relative abundances of different isotopic forms of a metabolite [11]. | The experimental observations (( O_{i} )) against which the model is tested. |

| Model-Simulated MIDs | Isotopomer distributions predicted by the metabolic model for a given set of fluxes [14]. | The theoretical expectations (( E_{i} )) used for comparison. |

| Measurement Variances (( \sigma^2 )) | Estimated uncertainties in the MID measurements [11]. | Used as weights in the χ² calculation; critical for test outcome. |

| Degrees of Freedom | Number of independent labeling measurements minus number of estimated flux parameters [14]. | Determines the critical χ² value for a chosen significance level (e.g., α=0.05). |

Critical Limitations of the χ2-Test in 13C-MFA

Despite its widespread use, the χ2-test possesses several limitations that can undermine its effectiveness as a standalone validation tool in 13C-MFA.

High Sensitivity to Measurement Error Estimates

The test's outcome is profoundly sensitive to the accuracy of the measurement variance estimates (( \sigma_i )) [11]. In practice, these variances are often estimated from the standard deviations of biological replicates, which can be very small (e.g., below 0.01) [11]. However, such low estimates may not capture all sources of error, such as:

- Systematic instrumental bias from mass spectrometers, which can cause underestimation of minor isotopomers [11].

- Deviations from metabolic steady-state in batch cultures, which are common but difficult to quantify [11]. When the assumed variances are underestimated, the χ² statistic becomes artificially inflated, leading to the statistically unjustified rejection of potentially valid models. Conversely, overestimating variances can lead to the acceptance of overly simplistic models that fail to capture important metabolic features [11].

The Model Selection Dilemma and Overfitting

Model development in 13C-MFA is often an iterative process where the network structure is modified to improve the fit [11]. Using the same dataset for both model fitting (parameter estimation) and model validation (χ2-test) creates a high risk of overfitting [11] [14]. A researcher may be tempted to add reactions or compartments to the model until it passes the χ2-test. While this yields a good fit to the estimation data, the resulting model may have poor predictive power for new, independent data, and the estimated fluxes may not reflect the true in vivo physiology [11].

The Goodness-of-Fit "Gray Zone"

The binary outcome of the χ2-test ("pass" or "fail") can be misleading. A model may pass the test statistically yet still exhibit systematic, biologically relevant discrepancies in the labeling patterns of specific metabolites [14]. Conversely, a model that fails the test might still provide accurate and useful estimates for the majority of central carbon metabolic fluxes. Relying solely on the χ2-test can thus obscure important nuances in model performance.

Emerging Alternatives and Complementary Methods

To address the limitations of the traditional χ2-test, several advanced validation and model selection strategies have been developed.

Validation-Based Model Selection

This approach uses an independent validation dataset that was not used for model fitting to evaluate model performance [11]. The model that demonstrates the best predictive power for this separate dataset is selected. This method is robust to inaccuracies in measurement error estimates and effectively guards against overfitting [11]. As Sundqvist et al. demonstrated, this technique consistently identified the correct model structure in simulations, unlike methods reliant solely on the χ2-test [11].

Integration of Metabolite Pool Size Data

A powerful extension for isotopically nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) is the simultaneous fitting of time-dependent labeling data and metabolite pool sizes [14] [3]. This provides an additional layer of constraints for the model. A combined model validation framework that incorporates pool size information can significantly enhance the identifiability of fluxes and the discrimination between alternative model structures [14] [3].

Bayesian and Resampling Methods

While not covered in depth in the provided search results, Bayesian methods for characterizing uncertainty in flux estimates have been developed [3]. These methods can provide a more complete picture of parameter uncertainties and model plausibility compared to a single χ2 statistic. Similarly, resampling techniques can be used to assess the stability and reliability of flux estimates.

Table 2: Comparison of Model Validation Approaches in 13C-MFA

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2-Test of Goodness-of-Fit | Tests if differences between model and data are statistically significant given measurement errors [14] [3]. | Well-established, computationally straightforward, provides a clear threshold. | Highly sensitive to error estimates; promotes overfitting when used for model selection [11]. |

| Validation-Based Selection | Selects model that best predicts a separate, independent validation dataset [11]. | Robust to unknown measurement errors; directly penalizes overfitting. | Requires collection of additional experimental data. |

| Pool Size Integration (INST-MFA) | Uses measurements of metabolite concentrations as additional constraints during flux estimation [14] [3]. | Increases number of data points and constraints; can improve flux resolution. | Requires precise concentration measurements and more complex INST-MFA modeling. |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced 13C-MFA Validation

To implement the validation-based model selection approach, the following experimental methodology is recommended.

Parallel Tracer Cultures for Training and Validation

A robust strategy involves designing parallel labeling experiments with different tracer substrates [11] [24].

- Training Data Set: Cultivate cells in a defined medium containing one type of 13C tracer (e.g., [1-13C] glucose). Measure the MIDs of target metabolites.

- Validation Data Set: Cultivate a separate culture of the same cell line under identical metabolic conditions but using a different 13C tracer (e.g., [U-13C] glucose). Measure the MIDs for the same set of metabolites [11]. This protocol ensures that the validation data is independent yet physiologically relevant. The model is fitted using only the training data and is then used to predict the MIDs of the validation experiment. The model with the best predictive performance for the validation data is selected [11].

Protocol for INST-MFA with Pool Size Quantification

For INST-MFA, which is particularly useful for systems where achieving isotopic steady state is difficult or slow (e.g., mammalian cells, cyanobacteria), the protocol involves [23] [24]:

- Rapid Sampling: After introducing the 13C tracer, collect samples at multiple time points (e.g., seconds to minutes) during the transient labeling period before isotopic steady state is reached.

- Quenching Metabolism: Rapidly quench cell metabolism immediately upon sampling using cold solvents to "freeze" the metabolic state.

- Dual Data Extraction: For each sample, extract and analyze metabolites to determine both:

- Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs): Via GC-MS or LC-MS.

- Metabolite Pool Sizes (Concentrations): Using appropriate quantitative analytical methods alongside internal standards.

- Integrated Modeling: The INST-MFA computational model is then fitted to the combined time-course of both MIDs and pool sizes, providing a more constrained and reliable flux estimation [14] [3].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for 13C-MFA Validation

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Substrates for carbon labeling experiments; enable tracking of metabolic pathways. | [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [1,2-13C]Glucose for parallel labeling studies [23] [24]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS, LC-MS) | Analytical core for measuring Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of metabolites [22] [24]. | Quantifying 13C incorporation into proteinogenic amino acids or intracellular metabolites [24]. |

| Stoichiometric Metabolic Model | Mathematical representation of the metabolic network, including atom mappings. | Defining the set of possible fluxes and simulating MIDs for a given flux map [14]. |

| Flux Estimation Software | Computational tools for solving the inverse problem of calculating fluxes from MIDs. | Software packages that implement parameter optimization, χ2-test, and uncertainty analysis [14]. |

| Quality Control Standards | Labeled internal standards for metabolite quantification and instrument calibration. | Ensuring accuracy and precision in both MID and pool size measurements [24]. |

The χ2-test of goodness-of-fit remains an important, though imperfect, tool in the 13C-MFA workflow. Its primary value lies in providing an initial check for gross model inadequacy. However, its sensitivity to measurement error and its inadequacy for model selection necessitate a more sophisticated approach. The future of robust flux validation lies in multi-faceted strategies that combine independent validation data, time-resolved labeling and pool size information from INST-MFA, and advanced statistical frameworks. By moving beyond a reliance on the χ2-test alone, researchers can generate metabolic flux maps with greater confidence, ultimately accelerating discoveries in systems biology and guiding more effective metabolic engineering strategies.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands as a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic fluxes within biochemical networks. By leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), FBA calculates flow distributions of metabolites through an organism's metabolism by optimizing a specified biological objective, such as biomass maximization, under steady-state and constraints [25] [26]. While FBA's predictive power has made it invaluable for applications ranging from microbial strain engineering to drug discovery, its reliability hinges on a critical, often challenging step: model validation [3].

Validation transforms FBA from a theoretical exercise into a trusted scientific tool. The process involves systematically comparing model predictions against experimental data to assess accuracy, identify model shortcomings, and build confidence in its predictive capabilities [3]. This guide provides a comparative examination of contemporary FBA validation methodologies, focusing on their capacity to corroborate both external growth predictions and internal flux distributions. We dissect experimental protocols, present quantitative performance data, and outline the essential toolkit for researchers undertaking model validation.

Comparative Analysis of FBA Validation Methods

The following table summarizes the core validation approaches, detailing their core principles, applications, and inherent limitations.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of FBA Validation Methodologies

| Validation Method | Core Principle | Data Used for Corroboration | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth/Product Yield Comparison | Compares predicted vs. measured growth rates or metabolite secretion [25]. | Biomass measurements, product titers from bioreactors [25]. | Initial model sanity checking, medium optimization, preliminary strain design [25]. | Does not validate internal flux distribution; insensitive to model topology errors [3]. |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Uses isotopic tracer data to estimate intracellular fluxes [3]. | Mass isotopomer distribution (MID) data from MS/NMR [3]. | Gold standard for validating internal flux maps in central metabolism [3]. | Experimentally intensive; limited to core metabolic networks. |

| Topology-Informed Objective Find (TIObjFind) | Infers objective functions & key reactions by aligning FBA with expt. data via pathway analysis [26] [27]. | Experimental flux data (e.g., from 13C-MFA) [26]. | Identifying context-specific metabolic objectives; enhancing interpretability [26] [27]. | Relies on availability of prior flux data; computational complexity. |

| Surrogate Model Validation | Uses machine learning (e.g., ANN) as a proxy for FBA; validates against dynamic data [28]. | Time-course data on biomass and metabolite concentrations [28]. | Validating model performance in dynamic environments and community settings [28]. | Black-box nature of ML models; requires large training dataset. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Methodologies

Protocol for 13C-MFA Validation of Internal Fluxes

13C-MFA remains the most rigorous method for validating the internal flux predictions of an FBA model [3]. The typical workflow is as follows:

- Experimental Design: Choose one or more 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C] glucose) that will generate distinct labeling patterns in downstream metabolites [3].

- Cultivation: Grow the organism in a controlled bioreactor with the labeled substrate, ensuring metabolic steady-state is reached before sampling [3].

- Mass Spectrometry Measurement: Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites. Analyze the extract using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) to measure the Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of proteinogenic amino acids or other metabolites [3].

- Computational Flux Estimation: Use dedicated software to find the flux map that minimizes the difference between the simulated MIDs (based on a network model and atom transitions) and the experimentally measured MIDs [3].

- Comparison and Validation: Statistically compare the fluxes estimated by 13C-MFA against the fluxes predicted by the FBA model. Techniques like flux spectrum analysis can be used to evaluate the agreement and identify significant discrepancies that point to model gaps or incorrect constraints [3].

Protocol for TIObjFind-Based Objective Function Validation

The TIObjFind framework validates and refines the biological objective function used in FBA, which is critical for accurate predictions [26] [27]. Its workflow involves:

- Data Integration: Collect experimental flux data ((v^{exp})), which can be obtained from 13C-MFA or other sources, for a set of key reactions under specific conditions [26].

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Perform FBA and map the solution to a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), a directed graph where nodes are reactions and edges represent metabolite flow [26] [27].

- Pathway Analysis via Minimum Cut: Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify the critical pathways connecting a source (e.g., substrate uptake) to a target (e.g., product formation) [26] [27].

- Coefficient of Importance (CoI) Calculation: The algorithm calculates CoIs, which are weights that quantify each reaction's contribution to the objective function. A higher CoI suggests the reaction flux is critical for aligning with the experimental data [26] [27].

- Model Refinement: The inferred CoIs can be used to define a weighted objective function, improving the model's alignment with experimental fluxes and providing insights into the organism's true metabolic objectives [26] [27].

Figure 1: The TIObjFind workflow for validating and refining FBA objective functions using experimental data and metabolic pathway analysis [26] [27].

Protocol for Dynamic Validation using Surrogate Models

For validating FBA models in dynamic environments, a machine learning-based approach can be highly effective [28].

- FBA Solution Space Sampling: Randomly sample the input space (e.g., varying substrate and oxygen uptake rates) and run FBA for each point to generate a comprehensive dataset of input-condition-to-output-flux mappings [28].

- Surrogate Model Training: Train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) on the generated dataset. A Multi-Input, Multi-Output (MIMO) architecture is often optimal for predicting all exchange fluxes simultaneously [28].