Minimizing Byproduct Formation in Engineered Microbes: Advanced Strategies for Efficient Bioproduction

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies to minimize byproduct formation in engineered microbial systems, a critical challenge in biotechnology for enhancing the yield and purity of biofuels,...

Minimizing Byproduct Formation in Engineered Microbes: Advanced Strategies for Efficient Bioproduction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies to minimize byproduct formation in engineered microbial systems, a critical challenge in biotechnology for enhancing the yield and purity of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms of undesirable metabolite formation, details cutting-edge methodological interventions from metabolic engineering to synthetic biology, and presents robust frameworks for troubleshooting and validating strain performance. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this resource aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to design more stable, efficient, and economically viable microbial cell factories.

Understanding the Challenge: The Sources and Impacts of Undesirable Byproducts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the primary types of byproducts in engineered microbial systems? Byproducts in engineered microbes generally fall into three categories [1]:

- Toxic End-Products: Such as organic acids, alcohols, and aromatic compounds, which can damage cell membranes and disrupt energy balance.

- Toxic Intermediates: Including compounds like aldehydes and reactive oxygen species, which can interfere with protein stability and DNA integrity.

- Compounds from Environmental Stress: Resulting from solvent accumulation, osmotic pressure, or pH shifts during large-scale fermentation.

Why is byproduct formation particularly problematic in slow-growing cultures? In slow-growing cultures, there can be an imbalance between the engineered pathway's capacity and the cell's actual metabolic needs. For instance, an overcapacity of enzymes like phosphoribulokinase (PRK) and RuBisCO in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae relative to the low NADH generation from biosynthesis in slow-growth conditions can lead to significant accumulation of toxic byproducts like acetaldehyde and acetate [2].

How can byproduct formation be mitigated without compromising the main product yield? Strategies include fine-tuning the expression levels of pathway enzymes, using growth-rate-dependent promoters, and reducing the copy number of key enzyme genes. These approaches balance pathway flux, prevent enzyme overcapacity, and minimize the diversion of carbon and energy toward unwanted byproducts [2].

What role do microbial communities play in reducing byproduct formation? Synthetic microbial communities can be designed to divide labor, where one member consumes a byproduct produced by another. This creates a cross-feeding system that recycles byproducts, improves overall resource utilization, and can increase the yield of the target product [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Acetaldehyde and Acetate Accumulation in Slow-Growing Cultures

Background This issue was observed in anaerobic, slow-growing chemostat cultures of S. cerevisiae engineered with a PRK/RuBisCO pathway for redox balancing and reduced glycerol production. The strain showed an 80-fold increase in acetaldehyde and a 30-fold increase in acetate compared to the reference strain at a dilution rate of 0.05 h⁻¹ [2].

Diagnosis Table

| Observation | Possible Cause | Investigation Method |

|---|---|---|

| High acetaldehyde/acetate at low growth rates only | Imbalance between high in vivo PRK/RuBisCO activity and low biosynthetic NADH formation | Measure enzyme activity and metabolite profiles at different growth rates [2] |

| Reduced maximum growth rate | Excessive metabolic burden or toxicity from byproducts | Compare growth curves of engineered and reference strains in batch culture [2] |

| Persistent glycerol production | Ineffective bypass of native glycerol formation pathway | Analyze glycerol yields at various dilution rates [2] |

Solution Strategies Table

| Solution Strategy | Protocol Outline | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce Enzyme Copy Number | Lower the genomic copy number of the RuBisCO-encoding cbbm cassette (e.g., from 15 to 2 copies) [2]. | Reduced acetaldehyde and acetate production without affecting glycerol suppression at low growth rates [2]. |

| Engineer Enzyme Stability/Level | Fuse a degradation tag (e.g., a 19-amino-acid tag) to the PRK enzyme to reduce its cellular concentration [2]. | Significant decrease in byproduct formation (e.g., 94% reduction in acetaldehyde) [2]. |

| Use Dynamic Promoters | Express the PRK gene using a promoter (e.g., ANB1) whose activity correlates with the growth rate [2]. | Byproduct formation is reduced at low growth rates without compromising performance at high growth rates [2]. |

Problem: Product Toxicity and Inhibition of Microbial Growth

Background The accumulation of toxic end-products (e.g., biofuels, organic acids) or intermediates can inhibit cell growth and limit production titers in bioproduction processes [1].

Diagnosis Table

| Observation | Possible Cause | Investigation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Decline in cell viability as product titer increases | Damage to cell membrane by hydrophobic products | Conduct membrane integrity assays (e.g., propidium iodide staining) [1]. |

| Reduced metabolic activity and ATP levels | Disruption of cellular energy balance or proton motive force | Measure intracellular ATP levels and membrane potential [1]. |

| Inhibition of specific enzyme activities | Interaction of toxic intermediates with proteins/DNA | Perform enzyme activity assays and check for protein aggregation [1]. |

Solution Strategies Table

| Solution Strategy | Protocol Outline | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Envelope Engineering | Modify membrane lipid composition (e.g., phospholipid head groups, sterol content) in bacteria or yeast to enhance stability [1]. | Enhanced tolerance to solvents and organic acids; shown to increase fatty acid and alcohol productivity [1]. |

| Overexpress Efflux Transporters | Overexpress endogenous or heterologous transporter proteins (e.g., ATP-binding cassette transporters) to actively export the toxic compound [1]. | Increased secretion of the toxic product (e.g., 5-fold increase in fatty alcohol secretion), reducing intracellular accumulation [1]. |

| Apply Evolutionary Engineering | Subject the production strain to gradual increases in the concentration of the toxic compound over multiple generations [1]. | Isolation of mutant strains with naturally enhanced tolerance and improved production performance [1]. |

Byproduct Reduction in Engineered Yeast Strains

The following table summarizes quantitative data from experiments with engineered S. cerevisiae strains aimed at reducing byproducts. The reference strain is IME324 (GPD2), and the initial engineered strain is IMX1489 (Δgpd2, non-ox PPP↑, pDAN1-prk, 15x cbbm, GroES/GroEL) [2].

Table: Byproduct and Product Yields in Anaerobic Chemostat Cultures (Dilution Rate = 0.05 h⁻¹) [2]

| Strain & Relevant Genotype | Glycerol Yield (C-mol/C-mol Biomass) | Acetaldehyde Yield (C-mol/C-mol Biomass) | Acetate Yield (C-mol/C-mol Biomass) | Ethanol Yield (C-mol/C-mol Glucose) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IME324 (Reference) | 0.92 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 1.65 |

| IMX1489 (15x cbbm) | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.60 | 1.73 |

| IMX2584 (2x cbbm) | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.43 | 1.74 |

| IMX2812 (2x cbbm, pANB1-prk) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1.74 |

Performance of Microbial Tolerance Engineering Strategies

This table compiles data from various studies where engineering the microbial cell envelope enhanced tolerance to toxic compounds [1].

Table: Cell Envelope Engineering for Enhanced Tolerance

| Strategy | Target Toxin/Stress | Microbial Host | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modification of phospholipid head group | Octanoic acid | E. coli | 66% increase in octanoic acid titer | [1] |

| Adjustment of fatty acid chain unsaturation | Octanoic acid | E. coli | 41% increase in octanoic acid titer | [1] |

| Overexpression of heterologous transporter protein | Fatty alcohols | S. cerevisiae | 5-fold increase in the secretion of fatty alcohols | [1] |

| Cell wall engineering | Ethanol | E. coli | 30% increase in ethanol titer | [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mitigating Byproducts via PRK Enzyme Tuning in Yeast

This protocol details the method to reduce acetaldehyde and acetate formation in slow-growing cultures of S. cerevisiae by destabilizing the PRK enzyme [2].

Key Reagents and Strains

- S. cerevisiae strain with a PRK/RuBisCO pathway (e.g., IMX1489 background).

- Plasmid or integration cassette for expressing C-terminal degradation-tagged PRK (e.g., PRK with a 19-amino-acid tag).

- Anaerobic bioreactor setup for chemostat cultures.

- HPLC or GC-MS system for quantifying metabolites (acetaldehyde, acetate, glycerol, ethanol).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Strain Construction: Clone the gene for spinach PRK, fused C-terminally to a 19-amino-acid degradation tag, into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., under the control of the DAN1 or ANB1 promoter).

- Transformation: Integrate the expression cassette into the genome of your target S. cerevisiae PRK/RuBisCO strain, replacing the original PRK gene.

- Cultivation: Inoculate the engineered strain and a control strain in defined synthetic medium with glucose as the carbon source.

- Anaerobic Chemostat Cultivation: Operate bioreactors as anaerobic chemostats at a low dilution rate (e.g., 0.05 h⁻¹) to mimic slow-growth conditions. Maintain strict anaerobic conditions by sparging the culture with nitrogen gas.

- Sampling and Analysis: Once steady-state is reached (typically after 3-5 volume changes), take samples from the culture broth.

- Metabolite Quantification: Centrifuge the samples and analyze the supernatant using HPLC or GC-MS to determine the concentrations of glucose, glycerol, ethanol, acetaldehyde, and acetate.

- Validation: Confirm the reduced protein level of the tagged PRK compared to the untagged version using Western blotting.

Expected Results The strain with the destabilized PRK should show a significant reduction in acetaldehyde (e.g., ~94%) and acetate (e.g., ~61%) yields compared to the strain with high PRK levels, while maintaining low glycerol production at a dilution rate of 0.05 h⁻¹ [2].

Protocol 2: Reducing Toxic Byproduct Formation in Photochemical Uncaging

This protocol describes a chemical approach to prevent the formation of a toxic byproduct (adrenochrome) during the light-induced release of epinephrine [4].

Key Reagents and Strains

- Classical "caged" epinephrine (ortho-nitrobenzyl group on the amino group).

- Carbamate-type "caged" epinephrine (ortho-nitrobenzyl group with a carbamate linker).

- UV light source (e.g., 350-365 nm LED).

- Plate reader or spectrometer for UV-Vis analysis.

- NMR spectrometer for structural confirmation.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Synthesis: Synthesize the classical caged epinephrine (Compound 1) and the carbamate-type caged epinephrine (Compound 2) as described in the literature [4].

- Photolysis: Prepare identical aqueous solutions of Compound 1 and Compound 2. Irradiate both samples simultaneously under the same conditions (e.g., with a 365 nm LED).

- Reaction Monitoring: Use UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor the photolysis reaction. The formation of adrenochrome is characterized by a distinct absorption peak at around 490 nm.

- Product Analysis: Analyze the photolysis products using analytical chromatography (e.g., TLC or HPLC) and NMR spectroscopy to confirm the identity and purity of the released epinephrine and any byproducts.

- Biological Validation: Test the biological activity of the released epinephrine in a relevant assay, such as a platelet activation assay.

Expected Results The classical caged epinephrine (Compound 1) will lead to the formation of adrenochrome, detectable by UV-Vis and chromatography. In contrast, the photolysis of the carbamate-type caged epinephrine (Compound 2) will result in the clean release of epinephrine without significant adrenochrome formation [4].

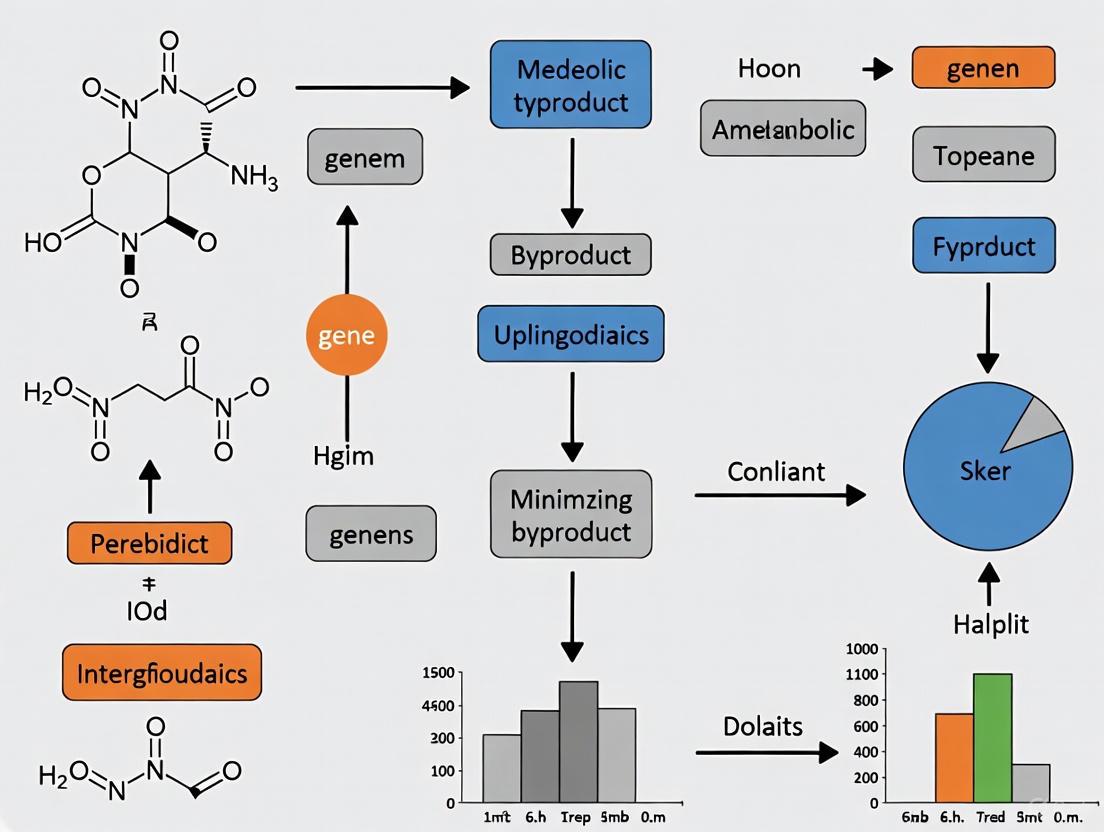

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Pathway for PRK/RuBisCO Bypass and Byproduct Formation

Diagram Title: PRK/RuBisCO Bypass and Byproduct Formation Pathways

This diagram illustrates the engineered pathway where PRK and RuBisCO convert Ribulose-5-P to 3-phosphoglycerate (3PG), facilitating NAD+ regeneration via ethanol production instead of glycerol. The red nodes highlight the problematic byproducts, acetaldehyde and acetate, which accumulate when the flux through this pathway is imbalanced, often due to enzyme overcapacity relative to biosynthetic NADH production [2].

Experimental Workflow for Byproduct Troubleshooting

Diagram Title: Byproduct Troubleshooting Workflow

This workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and solving byproduct formation issues, as demonstrated in the case of acetaldehyde accumulation [2]. The process involves metabolite profiling, hypothesis generation about the cause (e.g., enzyme overcapacity), and testing targeted solutions like enzyme tuning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating and Mitigating Byproduct Formation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoribulokinase (PRK) & RuBisCO Expression Cassettes | Engineered into yeast to provide a redox-balancing bypass, reducing glycerol formation and increasing ethanol yield. | Studying and optimizing carbon flux to minimize derailment into acetaldehyde and acetate [2]. |

| C-terminal Degradation Tags | Fused to proteins to reduce their intracellular stability and concentration, fine-tuning pathway enzyme levels. | Mitigating byproducts caused by enzyme overcapacity in slow-growing cultures [2]. |

| Growth-Rate Dependent Promoters (e.g., ANB1) | Drive gene expression in a growth-dependent manner, dynamically matching enzyme levels to metabolic demand. | Automatically adjusting PRK expression to prevent overcapacity at low growth rates [2]. |

| Membrane Lipid Modulators | Chemicals or genetic tools to alter membrane composition (e.g., phospholipid head groups, sterol content). | Enhancing microbial tolerance to toxic end-products like organic acids and biofuels [1]. |

| Heterologous Efflux Transporters | Proteins engineered to be overexpressed for active export of toxic compounds from the cell. | Reducing intracellular accumulation of toxic fatty alcohols or other products, improving tolerance and titer [1]. |

| Carbamate-Linker Caging Moieties | Photolabile protecting groups with a carbamate linker for clean drug release upon irradiation. | Enabling light-controlled release of epinephrine without the toxic byproduct adrenochrome [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary economic impacts of byproduct formation in bioprocesses? Byproduct formation directly undermines the economic viability of bioprocesses by reducing the titer, yield, and productivity (TYP) of the target compound. This leads to lower final product concentrations, inefficient substrate conversion, and reduced volumetric output. Economically, this translates to higher production costs for purification, increased raw material expenses, and lower overall process efficiency, making it difficult to compete with traditional chemical synthesis routes [5] [6].

Q2: Which common microbial byproducts are most detrimental to cell factories? Common detrimental byproducts include:

- Organic acids (e.g., acetate in E. coli), which inhibit cell growth and perturb central metabolism.

- CO₂ from decarboxylation reactions, representing a direct carbon loss [7].

- Toxic metabolites like formaldehyde in C1 metabolism, which can damage cellular components [7].

- Biogenic amines formed during fermentation of plant-based byproducts, which pose safety risks [8].

Q3: What operational strategies can minimize byproduct formation during scale-up? Key operational strategies include:

- Optimizing aeration and mixing to minimize shear stress and oxygen transfer limitations that can induce anaerobic byproducts [5].

- Implementing fed-batch or perfusion modes to avoid substrate overflow metabolism [9] [6].

- Using continuous processing with integrated monitoring for better control, though this introduces challenges with operational complexity and contamination risks [6].

Q4: How can machine learning help reduce byproduct formation? Machine learning models like CatBoost, Random Forest, and XGBoost can predict optimal fermentation conditions to maximize target bioproducts and minimize byproducts. For instance, Bayesian optimization-trained models can identify ideal setpoints for variables like reaction time, mineral medium concentration, and illumination conditions, significantly improving yield [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Titer Due to Carbon Loss to CO₂

Description: A significant portion of the carbon substrate is lost as CO₂ instead of being directed toward the target product, drastically reducing titer.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Confirm: Track carbon flux using ¹³C metabolic flux analysis.

- Act:

- Decouple Growth from Production: Use dynamic regulation or two-stage processes to separate biomass generation from product synthesis.

- Reduce Metabolic Burden: Identify and knock down non-essential high ATP- and NADPH-consuming reactions using tools like CRISPRi screening (CECRiS method) to reallocate energy toward product formation [10].

- Implement Linear Pathways: Introduce orthogonal, non-native pathways like the reductive glycine pathway (rGlyP) for C1 assimilation, which have higher carbon efficiency and fewer side reactions compared to natural cyclic pathways [7].

Problem: Accumulation of Inhibitory Organic Acids

Description: Acids like acetate accumulate, inhibiting cell growth and reducing productivity, especially at high cell densities.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Confirm: Measure acetate levels offline or with online sensors.

- Act:

- Modulate Carbon Uptake: Use controlled feeding strategies to avoid sugar overflow.

- Engineer Central Metabolism: Knock out genes involved in acetate synthesis pathways (e.g., pta, ackA) and enhance glyoxylate shunt or TCA cycle activity.

- Control Redox Balance: Fine-tune the supply of NADPH to prevent imbalances that lead to acid formation [10].

Problem: Scale-Up-Induced Byproduct Formation

Description: A process that performs well at bench-scale shows increased byproduct formation and heterogeneity when scaled to industrial bioreactors.

Investigation & Resolution:

- Confirm: Use scale-down models to simulate large-scale heterogeneities (e.g., nutrient gradients) in a small bioreactor.

- Act:

- Improve Mixing and Mass Transfer: Optimize impeller design and aeration strategies to ensure uniform conditions. Address oxygen transfer limitations, a common scale-up challenge [5].

- Use Robust Promoters: Replace constitutive promoters with native C1-inducible or other robust promoters that remain stable under fluctuating industrial bioreactor conditions [7].

- Implement Advanced Process Control: Integrate sensors and control systems for real-time monitoring and adjustment of pH, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient feed to maintain optimal parameters [5] [6].

Data Presentation

| Model | Key Input Variables | Predicted Maximum Yields (Example) | Primary Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | Reaction time, Organic matter concentration, Mineral medium, Volume exchange %, Illumination | Polyhydroxybutyrate: 569 mg/L, Coenzyme Q10: 13 mg/g dw | Highest predictive correlation, lowest error, handles categorical data well |

| XGBoost | C/N ratio, Ethanol, Bicarbonate, Operation mode (batch/semicontinuous) | Biomass: 2040 mg/L, 5-aminolevulinic acid: 79 µmol/L | High performance, fast execution, good for structured data |

| Random Forest | Levulinic acid, Ferric citrate, Illumination conditions | Carotenoids: 7 mg/g dw, Bacteriochlorophylls: 17 mg/g dw | Robust to overfitting, provides feature importance |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering to Reduce Byproducts

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application in Byproduct Mitigation |

|---|---|

| CRISPRi/dCas9 | Silencing non-essential genes that consume high ATP/NADPH, redirecting energy to product synthesis [10]. |

| Cofactor Engineering (CECRiS) | Identifies energy-draining genes to rebalance ATP/NADPH supply for enhanced product yield [10]. |

| Native C1-inducible Promoters | Provides tight regulatory control in non-model hosts, preventing metabolic burden and unwanted side reactions [7]. |

| Fusion Tags (e.g., CrOAS-CPR) | Enhances electron transfer and catalytic efficiency of enzyme complexes, improving pathway flux and reducing intermediate byproducts [11]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Computational algorithm to find global optimum process conditions for maximizing target product formation [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CECRiS for Redirecting Cellular Energy

Objective: To identify and silence genes that excessively consume ATP and NADPH, thereby reallocating metabolic energy to product synthesis and minimizing energy-dissipating byproducts [10].

Materials:

- CRISPRi system (dCas9 and sgRNA expression plasmids)

- sgRNA library targeting ATP/NADPH consuming genes

- Host strain (e.g., E. coli)

- Media and inducers

Procedure:

- Library Design: Design an sgRNA library targeting 80 NADPH-consuming and 400 ATP-consuming genes.

- Transformation: Introduce the dCas9 and sgRNA library into the host strain.

- Screening: Culture the transformed library and use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to screen for clones with improved product titer.

- Validation: Sequence the sgRNAs from high-performing clones to identify target genes.

- Fine-tuning: For essential genes, implement a quorum sensing-based knockdown system to reduce their expression only after sufficient biomass growth [10].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Process Optimization

Objective: To use machine learning models to predict the optimal combination of fermentation parameters that maximize target product yield and minimize byproducts [9].

Materials:

- Historical or experimentally generated dataset of process parameters and outcomes.

- Machine learning environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, CatBoost).

- Bayesian optimization toolbox.

Procedure:

- Data Compilation: Compile a dataset with input variables (e.g., reaction time, substrate concentrations, C/N ratio, illumination) and output variables (e.g., bioproduct titers).

- Model Training & Selection: Train multiple models (e.g., CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest). Use Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning and select the best model based on R², RMSE, and MAPE.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use the selected model to identify the most influential process parameters on byproduct formation.

- Prediction & Validation: Apply the model with a Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm to determine the global optimum conditions. Validate these conditions in a lab-scale bioreactor [9].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Figure 1: Integrated troubleshooting workflow for overcoming byproduct limitations, combining metabolic engineering and bioprocess optimization.

Figure 2: Metabolic network showing competition for resources and the detrimental impact of byproduct formation on target product synthesis.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Minimizing Byproduct Formation

FAQ 1: What are the common root causes of byproduct formation in engineered microbial systems for biofuel and polyketide production?

Byproduct formation often stems from inherent properties of the native microbial metabolic networks. Key causes include:

- Low Enzyme Specificity: The catalytic enzymes in the desired pathway may have broad substrate specificity or low product specificity, leading to the formation of derailment products. For instance, in type III polyketide synthases (PKSs) like chalcone synthase (CHS), the enzyme can catalyze lactonization of reaction intermediates, producing unwanted compounds like p-coumaroyltriacetic acid lactone (CTAL) instead of the target naringenin chalcone [12].

- Competing Metabolic Pathways: Native host metabolism can divert key precursors away from the desired product. In E. coli, thioesterases can hydrolyze crucial acyl-CoA starter molecules or intermediates, making them unavailable for the engineered polyketide pathway and reducing yield [12].

- Insufficient Precursor Supply: An imbalance in the intracellular concentration of essential precursors, such as malonyl-CoA for polyketide synthesis or methylmalonyl-CoA for complex macrolides, can stall the main pathway and promote side reactions [13] [14].

- Toxicity and Stress Responses: The accumulation of target products (e.g., biofuels) or intermediates can inhibit microbial growth and metabolism, triggering stress responses that negatively impact production and sometimes increase byproduct formation [15].

FAQ 2: What genetic strategies can be employed to enhance the specificity of a biosynthetic pathway and reduce byproducts?

Advanced metabolic engineering and synthetic biology strategies are highly effective:

- Enzyme Engineering: Directly evolve key enzymes for higher specificity. A growth-based selection system in E. coli was used to evolve a beneficial CHS mutant, which resulted in a ~3-fold improvement in naringenin production and a significant reduction in byproducts [12].

- Pathway Refactoring: Completely redesign the native biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) by replacing its native promoters and regulatory elements with well-characterized, constitutive ones. This decouples production from complex native regulation and can optimize the stoichiometry of enzyme expression. Refactoring a 79-kb spinosyn cluster into 7 operons with strong promoters in Streptomyces albus led to successful heterologous production [16].

- Knockout of Competing Pathways: Genetically disrupt genes encoding enzymes that lead to byproduct formation or that divert flux away from your target product. This can include deleting genes for native thioesterases or other hydrolases that consume essential pathway intermediates [12] [17].

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement regulatory circuits that automatically downregulate competing pathways when the flux through the desired pathway is high, thereby optimizing carbon allocation [18].

FAQ 3: How can I use a growth selection system to identify microbial strains with reduced byproduct formation?

A growth selection system links the survival of the microbe to the desired metabolic outcome. One effective design is based on the detoxification of a toxic intermediate:

- Principle: A toxic intermediate, such as a fatty acyl-CoA, is overproduced due to a blocked pathway. The accumulation of this intermediate inhibits cell growth. If a functional heterologous pathway (e.g., a PKS) is introduced that can utilize this toxic compound as a starter molecule, its consumption relieves the toxicity and allows the cell to grow [12].

- Application: This system was used to select for E. coli strains with functional CHS expression. Strains that efficiently converted the toxic p-coumaroyl-CoA into naringenin chalcone grew rapidly, while those with inefficient pathways or high byproduct formation were outcompeted. This enabled the direct evolution of both the CHS enzyme and the host genome for superior performance [12].

FAQ 4: What host engineering approaches can improve precursor availability for my pathway?

Engineering the host's central metabolism is crucial for supplying building blocks:

- Augmenting Precursor Pools: To produce 6-deoxyerythronolide B (6-dEB) in E. coli, engineers deleted the propionate catabolism genes (

prpRBCD) to prevent precursor degradation. They also overexpressed a propionyl-CoA synthetase (prpE) and a propionyl-CoA carboxylase from Streptomyces coelicolor to enhance the supply of the extender unit methylmalonyl-CoA [13]. - Enhancing Cofactor Supply: Many pathways require specific cofactors. Introducing heterologous genes or modulating the expression of native genes can increase the availability of cofactors like malonyl-CoA, NADPH, or acetyl-CoA, which are essential for many biofuel and polyketide pathways [15] [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing a Growth Selection System for Pathway Optimization

This protocol is adapted from a study that engineered E. coli for efficient naringenin production [12].

Objective: To select for engineered microbial strains with enhanced flux through a desired pathway and reduced byproduct formation, using a growth-based screen.

Materials:

- Strain: An E. coli production strain (e.g., CUR01 [12]) with a knocked-out native pathway that leads to accumulation of a toxic intermediate.

- Plasmids: Expression vectors containing the heterologous biosynthetic pathway genes (e.g., p-coumarate:CoA ligase and Chalcone Synthase).

- Media: Yeast extract M9 media (YM9).

Methodology:

- Library Creation: Generate a library of genetic variants. This can be a mutant library of your key biosynthetic enzyme (created via error-prone PCR) or a random mutagenesis library of the host genome.

- Transformation: Introduce the plasmid library containing your heterologous pathway genes into the selection host strain.

- Selection Pressure: Plate the transformed cells onto solid YM9 media or grow in liquid culture under conditions that induce the expression of the genes leading to the toxic intermediate accumulation.

- Screening for Growth: Incubate and monitor for colonies that demonstrate significantly improved growth. These "fast-growing" clones have likely evolved more efficient mechanisms to consume the toxic intermediate via your engineered pathway.

- Validation and Characterization: Isolate the fast-growing clones and characterize them in shake-flask fermentation. Quantify the titers of your target product and prominent byproducts using HPLC or LC-MS to confirm the enhanced product specificity.

Protocol 2: Refactoring a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for Heterologous Expression

Objective: To reconfigure a large, native biosynthetic gene cluster for optimal expression in a heterologous host like Streptomyces albus or E. coli.

Materials:

- DNA Source: The native polyketide BGC.

- Cloning System: An appropriate system for large DNA manipulation (e.g., ExoCET, TAR cloning, or CRISPR-Cas9 assisted cloning) [16].

- Host Strain: A heterologous host with a clean metabolic background (e.g., S. albus J1074, E. coli BAP1).

Methodology:

- Cluster Analysis: Identify all open reading frames and regulatory elements within the native BGC using bioinformatics tools.

- Design Synthetic Operons: Break the large cluster into smaller, logical operons. Replace native promoters with strong, constitutive promoters (e.g., from Streptomyces albus [16]).

- Vector Assembly: Use a suitable cloning technique to assemble the refactored operons into a single capturing vector (e.g., a bacterial artificial chromosome).

- Heterologous Expression: Introduce the refactored gene cluster into the heterologous host.

- Fermentation and Analysis: Culture the engineered host and screen for the production of the target compound using LC-MS or other analytical methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Byproduct Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Host Organism | Target Product | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Selection & Enzyme Evolution | E. coli | Naringenin | Product specificity (E value) improved from 50.1% to 96.7%; Titer reached 1082 mg/L in flask. | [12] |

| Pathway Refactoring | S. albus | Spinosyns | Successful heterologous production of a complex polyketide from a 79-kb synthetic multi-operon assembly. | [16] |

| Precursor Pool Engineering | E. coli BAP1 | 6-deoxyerythronolide B | Achieved titers of ~1.1 g/L by optimizing methylmalonyl-CoA supply and fermentation. | [13] |

| Iterative PKS Engineering | E. coli | Pentadecaheptaene (PDH) | Optimizing the PKS:Thioesterase ratio enabled high-yield production of a single-form hydrocarbon. | [14] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Troubleshooting Workflow for Byproduct Minimization

Byproduct Formation in Type III PKS Catalysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Engineering Microbial Factories

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed engineering. | Reducing lignin content in barley to improve bioethanol yield [15]; Activating silent gene clusters [16]. |

| Strong Constitutive Promoters | To drive high-level, consistent expression of pathway genes in heterologous hosts, independent of native regulation. | Refactoring polyketide clusters in S. albus using promoters from its own genome [16]. |

| Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases (e.g., Sfp) | Essential for activating carrier proteins (ACPs) in PKS and NRPS systems by adding the phosphopantetheine arm. | Essential for functional expression of DEBS in E. coli strain BAP1 [13]. |

| Chassis Strains (e.g., E. coli BAP1, S. albus J1074) | Engineered heterologous hosts with clean metabolic backgrounds, improved precursor supply, and simplified genetics. | BAP1: Production of 6-dEB and erythromycin A [13]. J1074: Heterologous expression of refactored spinosyn and kinamycin clusters [16]. |

| Growth Selection Systems | High-throughput screening method that links cell survival to the functional activity of a desired pathway. | Selecting for E. coli with high naringenin production and low byproduct formation [12]. |

| Thioesterases (TEs) | Release enzymes that cleave the final product from the PKS assembly line. Their specificity is critical for product outcome. | SgcE10 TE was engineered for high-yield production of the hydrocarbon PDH [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Unusual Byproduct Accumulation in E. coli

Problem: Unexpected acetate accumulation is inhibiting cell growth and reducing recombinant protein yield.

Investigation Checklist:

- Confirm Measurement: Verify acetate concentration using your HPLC or enzymatic assay method.

- Check Carbon Source: Is glucose concentration excessive? Measure residual glucose in the medium.

- Assess Aeration: Dissolved Oxygen (DO) levels should be maintained above 20-30% air saturation. Check for stirrer faults or clogged spargers.

- Review Strain Genetics: Confirm the genetic background of your production strain and the integrity of pathway modifications (e.g., acetate pathway knockouts like ackA-pta).

Solutions:

- Implement a Fed-Batch Protocol: Switch from batch culture to a controlled glucose feed to avoid overflow metabolism. Maintain glucose at a low, growth-limiting concentration.

- Optimize Aeration: Increase agitation, aeration rate, or oxygen partial pressure. Antifoam agents may be necessary if oxygen transfer is limited by foam.

- Consider Strain Engineering: Utilize engineered E. coli strains with reduced acetate production pathways (e.g., ackA-pta deletions) or enhanced glyoxylate shunt activity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Ethanol Build-Up in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Problem: Ethanol production under aerobic conditions (the Crabtree effect) is diverting carbon from biomass and target products.

Investigation Checklist:

- Measure Ethanol: Quantify ethanol concentration in the culture supernatant.

- Verify Aeration & Mixing: Ensure DO probes are calibrated and functional. Confirm that culture volume does not exceed flask/bioreactor working volume recommendations for optimal gas transfer.

- Check Glucose Concentration: High glucose (> critical concentration, often ~0.1-1 g/L for Crabtree-positive yeasts) triggers aerobic fermentation.

Solutions:

- Reduce Glucose Feeding Rate: Implement a fed-batch strategy with a low, constant feed rate or an exponential feed matching the organism's maximum respiratory capacity.

- Use an Alternative Carbon Source: Replace glucose with a non-fermentable carbon source like glycerol or ethanol for pre-culture or specific production phases.

- Select a Crabtree-Negative Strain: For processes requiring fully respiratory metabolism, use Crabtree-negative yeasts like Kluyveromyces marxianus or Pichia pastoris (Komagataella phaffii).

Troubleshooting Guide: Reduced Product Titer in Cyanobacteria

Problem: Low yield of target product (e.g., fatty acid, alcohol) despite genetic modifications.

Investigation Checklist:

- Confirm Light Intensity: Measure light intensity at the culture surface. Sub-saturating light limits the energy and carbon supply.

- Check for Self-Shading: High cell density cultures can cause severe light attenuation, limiting growth and production.

- Analyse Carbon Partitioning: Determine if carbon is being directed towards other storage compounds (e.g., glycogen, exopolysaccharides) instead of the desired product.

- Assess Nutrient Balance: Ensure nitrogen and/or phosphorus are not limiting unless intended for a specific production phase.

Solutions:

- Optimize Light Regime: Increase light intensity to saturating levels (strain-dependent, often 50-200 μmol photons/m²/s). Consider light-dark cycling in photobioreactors.

- Manage Cell Density: Maintain an optimal, lower cell density to minimize self-shading and ensure uniform light exposure.

- Engineer Carbon Flux: Knock out competing pathways (e.g., glycogen synthesis) and overexpress key enzymes in the product synthesis pathway.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Byproduct Minimization

Q1: What are the primary causes of byproduct formation in engineered microbes? Byproducts typically arise from metabolic imbalances. Key causes include carbon overflow metabolism (excess carbon influx, e.g., acetate in E. coli, ethanol in yeast), redox imbalance (cells generate reduced byproducts to regenerate NAD+), and limiting co-factors or nutrients (e.g., oxygen, nitrogen) that disrupt normal metabolic flow [20].

Q2: How can I rapidly identify an unknown byproduct that is accumulating? A combination of analytical techniques is most effective. Start with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for separation and quantification. Couple this with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for identification. For volatile compounds (e.g., alcohols, acetone), Gas Chromatography (GC-MS) is the preferred method.

Strain-Specific Issues

Q3: My E. coli culture is producing acetate even in a controlled fed-batch. What could be wrong? This could indicate a micro-aerobic environment. Check that your dissolved oxygen (DO) probe is accurately calibrated and that the DO control loop is functioning correctly. Even brief periods of oxygen limitation can trigger acetate formation. Also, verify the genotype of your strain to ensure acetate pathway mutations are intact.

Q4: I am using a cyanobacterium for production. Why is my product titer low even with a strong promoter? Cyanobacteria often face energy and redox limitations. The product pathway may be consuming too much ATP or generating redox imbalance, causing metabolic stress and low yields. Consider engineering the ATP/NAD(P)H supply, using a tunable promoter instead of a strong constitutive one, or optimizing the light intensity and CO2 supply to enhance the native energy generation capacity.

Experimental Design & Analysis

Q5: What is the most important parameter to monitor in a microbial byproduct minimization experiment? The growth rate (μ) is critical. A sudden change in growth rate often signals metabolic stress or byproduct formation. Continuously monitor and control key environmental parameters like dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH, as these directly influence metabolic pathways. Off-gas analysis (e.g., CER, OUR) can provide real-time insights into metabolic activity.

Q6: How do I calculate the yield of my target product versus a problematic byproduct?

Calculate the yield coefficient (YP/S). This is the mass of product (P) or byproduct (B) formed per mass of substrate (S, e.g., glucose) consumed. Formula: Y_P/S = (P_final - P_initial) / (S_initial - S_final). Comparing YP/S for your target product and key byproducts quantitatively assesses carbon efficiency.

Table 1: Common Microbial Byproducts and Their Impact

| Microbial Host | Common Byproduct | Typical Formation Condition | Impact on Fermentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Acetate | High glucose, O₂ limitation | Inhibits growth, reduces recombinant protein yields |

| S. cerevisiae | Ethanol | High glucose (Crabtree effect) | Diverts carbon from biomass, can be inhibitory at high concentrations |

| Cyanobacteria | Glycogen/Exopolysaccharides | Nitrogen depletion, high light | Diverts carbon away from target products (e.g., biofuels) |

| E. coli | D-Lactate | Mixed-acid fermentation, low pH | Contributes to medium acidification |

| Lactobacillus | Lactic Acid | Anaerobic respiration | Lowers pH, can inhibit own growth |

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Byproduct Profiling

| Technique | Measured Analytes | Sample Requirements | Key Output Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC | Organic acids (acetate, lactate), alcohols, sugars | Cell-free supernatant | Concentration (g/L), Yield (Y_P/S) |

| GC-MS | Volatile compounds (ethanol, acetone, butanol), fatty acids | Derivatized or volatile extract | Concentration, Positive identification |

| Enzymatic Assays Kits | Specific metabolites (acetate, lactate, glycerol) | Cell-free supernatant | Concentration (mM or g/L) |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Broad range of metabolites, unknown ID | Whole broth or extract | Relative concentrations, Pathway mapping |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Acetate in E. coli Cultures

Principle: This protocol uses High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to separate and quantify acetate from other components in the culture broth.

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV/RI detector

- HPLC column (e.g., Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H, 300 mm x 7.8 mm)

- Mobile Phase: 5 mM H₂SO₄, filtered (0.2 μm) and degassed

- Acetate standard solutions (e.g., 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 g/L)

- Sample vials and filters (0.2 μm, nylon or PTFE)

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge 1 mL of culture broth at high speed (e.g., 13,000 x g) for 5 minutes. Carefully filter the supernatant through a 0.2 μm filter into an HPLC vial.

- HPLC Setup:

- Column Temperature: 50-60 °C

- Mobile Phase Flow Rate: 0.6 mL/min

- Detector: Refractive Index (RID), temperature ~35-50 °C

- Injection Volume: 10-20 μL

- Run Time: ~20-30 minutes (acetate typically elutes at ~14-16 min on an HPX-87H column).

- Execution:

- Run the acetate standards to create a calibration curve (Peak Area vs. Concentration).

- Inject your prepared samples.

- Integrate the acetate peaks and use the calibration curve to calculate the concentration in your samples.

Protocol 2: Inducing and Measuring the Crabtree Effect in Yeast

Principle: This experiment demonstrates how high glucose levels trigger aerobic fermentation and ethanol production in S. cerevisiae.

Materials:

- S. cerevisiae wild-type (Crabtree-positive) strain

- Shake flasks containing defined media (e.g., YNB) with high (2%) and low (0.1%) glucose

- Orbital shaker incubator

- Spectrophotometer

- HPLC or GC-MS system for ethanol quantification

Method:

- Inoculation and Growth: Inoculate two flasks (high and low glucose) with an overnight pre-culture. Incubate at 30°C with vigorous shaking (e.g., 250 rpm) to ensure full aeration.

- Monitoring: Monitor cell growth by measuring optical density (OD600) every 2-3 hours.

- Sampling: Take samples during mid-exponential growth phase. Centrifuge to obtain cell-free supernatant.

- Analysis:

- Analyze the supernatants for glucose consumption and ethanol production using HPLC or an enzymatic assay.

- Compare the growth curves and ethanol levels between the high and low glucose cultures. Expect significant ethanol accumulation only in the high-glucose condition.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Aerobic Fermentation in Yeast

Microbial Byproduct Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Byproduct Analysis

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Aminex HPX-87H HPLC Column | Separation of organic acids, alcohols, and sugars. | Industry standard for fermentation broth analysis. Use with 5 mM H₂SO₄ mobile phase. |

| R-Biopharm Enzymatic BioAnalysis Kits | Specific, spectrophotometric quantification of metabolites (e.g., acetate, ethanol). | High specificity; ideal for validating HPLC data or for labs without dedicated HPLC systems. |

| Defined Minimal Media (e.g., M9, YNB) | Provides controlled nutrient environment for precise metabolic studies. | Essential for carbon tracing experiments and for eliminating interference from complex media components. |

| RNAprotect / RNA Later Reagent | Rapid stabilization of cellular RNA to preserve in-vivo gene expression profiles. | Critical for analyzing transcriptomic changes in response to byproduct accumulation or metabolic stress. |

| C13-Labeled Glucose (e.g., U-13C6) | Tracer for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) to quantify pathway activities. | Allows researchers to map the precise flow of carbon through central metabolism and into byproducts. |

Engineering Solutions: From Metabolic Routing to Synthetic Biology

In the pursuit of developing efficient microbial cell factories, a central challenge is overcoming the robust regulation of native metabolic networks. Redirecting carbon flux toward desired products while minimizing byproduct formation is a fundamental goal in metabolic engineering. This technical resource center addresses this challenge by providing targeted troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for implementing advanced carbon flux redirection strategies, with a specific focus on shunting pathways such as the glyoxylate shunt and non-oxidative glycolysis [21].

The field has evolved from initial rational approaches to contemporary third-wave strategies that integrate systems biology, synthetic biology, and computational modeling. These approaches enable precise rewiring of cellular metabolism across multiple hierarchies—from individual enzymes and pathways to genome-scale networks [21]. This guide consolidates the most current methodologies and troubleshooting knowledge to support researchers in overcoming common bottlenecks in metabolic engineering projects aimed at minimizing carbon waste.

Core Principles: Carbon Flux Redirection and Pathway Shunting

Understanding Key Metabolic Engineering Strategies

Carbon Flux Redirection involves systematically manipulating metabolic networks to enhance the flow of carbon precursors from central metabolism toward target biosynthetic pathways. This typically requires down-regulating competing pathways while strengthening rate-limiting steps in the desired production route [21].

Pathway Shunting creates shortcuts in native metabolic networks, often bypassing decarboxylation steps or long, regulated routes to conserve carbon and improve yield. The glyoxylate shunt is a prime example, bypassing two decarboxylation steps in the TCA cycle to directly convert isocitrate to malate via glyoxylate, significantly enhancing succinate production in engineered microorganisms [22].

The successful implementation of these strategies requires a multidimensional approach, as demonstrated in recent high-performance systems:

- Dual-pathway coordination: Simultaneous operation of native and heterologous pathways for the same product, as demonstrated in 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) production where endogenous C5 and exogenous C4 pathways were dynamically coordinated [23]

- Non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG): Introduced in Yarrowia lipolytica to enhance acetyl-CoA supply for betulinic acid production, significantly improving precursor availability [24]

- Quorum sensing regulation: Used to dynamically control critical pathway genes like hemB in E. coli, automatically balancing cell growth and product biosynthesis [23]

Quantitative Performance of Advanced Metabolic Engineering Strategies

Table 1: Performance metrics of carbon flux redirection strategies in recent studies

| Host Organism | Target Product | Engineering Strategy | Performance Achieved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) | Dual-pathway (C5/C4) coordination, quorum sensing regulation of hemB, NOG pathway | 37.34 g/L in 5L bioreactor | [23] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Betulinic acid | Multidimensional engineering: protein engineering of CYP716A155 (E120Q), NOG pathway, redox engineering | 271.3 mg/L in shake flask; 657.8 mg/L in 3L bioreactor | [24] |

| Synechococcus elongatus PCC 11801 | Succinate | Heterologous glyoxylate shunt (ICL+MS), SDH knockout via CRISPR-Cpf1 | Extracellular succinate production achieved | [22] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Lysine | Pyruvate carboxylase and aspartokinase overexpression based on flux analysis | 150% increase in productivity | [21] |

| E. coli | Succinate | Glyoxylate pathway activation, manipulation of TCA cycle | High yields under aerobic conditions | [22] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Addressing Metabolic Engineering Bottlenecks

Q1: My engineered strain shows good target gene expression but minimal product formation. What could be wrong?

This typically indicates metabolic bottlenecks downstream of transcription. Several factors could be responsible:

- Insufficient precursor supply: The carbon flux through central metabolism may be inadequate. Consider introducing non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) to enhance acetyl-CoA supply [24] or engineering precursor pathways as demonstrated in betulinic acid production [24].

- Cofactor imbalance: NADPH/NADP+ or ATP/ADP ratios may be limiting. Implement redox engineering strategies such as introducing NADP+-dependent enzymes (GPD1, MCE2) to convert NADH to NADPH [24].

- Competing pathways: Native metabolism may be diverting carbon. Use CRISPR-based tools to knockout competing genes, as demonstrated with succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) knockout to prevent succinate conversion to fumarate [22].

- Product toxicity: The target compound may inhibit growth. Strengthen efflux mechanisms and oxidative stress tolerance systems, which significantly improved 5-ALA production [23].

Q2: How can I dynamically balance cell growth and product biosynthesis?

Quorum sensing-based regulatory systems provide an effective solution. This approach was successfully implemented in 5-ALA production, where hemB expression was dynamically regulated to automatically shift resources from growth to production at appropriate cell densities [23]. Alternative approaches include:

- Promoter engineering: Use native, tunable promoters rather than strong constitutive ones. In cyanobacterial succinate production, native promoters (cpcb300, psbA1) ensured better metabolic integration than strong heterologous promoters [22].

- Two-stage fermentation: Separate growth and production phases, activating the product pathway specifically during the production phase through controlled feeding strategies [23].

Q3: What strategies effectively enhance carbon efficiency toward my target product?

- Implement shunting pathways: The glyoxylate shunt successfully enhanced succinate production in multiple hosts by bypassing decarboxylation steps [22].

- Mobilize storage pools: In Y. lipolytica, mobilizing lipid metabolism pathways redirected carbon from storage lipids to target products [24].

- Down-regulate competing pathways: Fine-tuning glycolysis and reducing flux through sterol pathways improved carbon efficiency for betulinic acid production [24].

- Improve carbon conservation: Non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) significantly improves carbon efficiency compared to Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway [23] [24].

Q4: How can I optimize difficult enzyme reactions like cytochrome P450 catalysis?

Protein engineering combined with subcellular engineering addresses common P450 limitations:

- Rational mutagenesis: Introducing the E120Q mutation in CYP716A155 enhanced catalytic activity for betulinic acid production [24].

- Organelle engineering: Subcellular compartmentalization of key enzymes and enhancing membrane contact sites (MCSs) accelerated downstream carbon flux [24].

- Cofactor balancing: Ensure adequate heme and NADPH supply for P450 function.

Troubleshooting Metabolic Imbalances

Table 2: Diagnostic and solution framework for common metabolic engineering challenges

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Approaches | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product titer despite high pathway gene expression | Metabolic bottlenecks, cofactor limitations, precursor shortage | Flux balance analysis, metabolomics, cofactor measurements | Implement NOG pathway [24], introduce redox engineering [24], enhance precursor supply |

| Byproduct accumulation | Competing pathways, insufficient pathway specificity | Metabolite profiling, ({}^{13}C)-flux analysis | Knock out competing genes (e.g., SDH for succinate [22]), fine-tune pathway expression |

| Growth impairment after engineering | Metabolic burden, toxicity, resource depletion | Growth curve analysis, RNA-seq, ATP/ADP measurements | Implement dynamic regulation [23], two-stage fermentation [23] |

| Declining production in extended fermentation | Genetic instability, enzyme inhibition, resource depletion | Plasmid stability assays, enzyme activity tests | Use chromosomal integration [22], promoter engineering [22] |

| Inefficient cofactor regeneration | Cofactor imbalance, insufficient regeneration capacity | NADPH/NADP+ and NADH/NAD+ measurements | Introduce NADP+-dependent enzymes (GPD1, MCE2) [24] |

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Workflow for Implementing the Glyoxylate Shunt

Protocol: Implementing Glyoxylate Shunt for Enhanced Succinate Production

Based on successful implementation in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 11801 [22]:

Materials:

- Host strain (e.g., S. elongatus PCC 11801, E. coli)

- BG-11 medium for cyanobacteria or LB for E. coli

- Isocitrate lyase (ICL) and malate synthase (MS) genes (from E. coli MG1655)

- Native promoters (Pcpcb300, PpsbA1 for cyanobacteria)

- CRISPR-Cpf1 system for gene knockout

- Fermentation equipment

Procedure:

Construct Design and Assembly

- Amplify ICL and MS genes separately using specific primers

- Clone genes under selected native promoters (Pcpcb300 showed superior performance for operon expression)

- Assemble expression cassettes with appropriate terminators (Tlac, TrrnB)

- Verify constructs by sequencing

Strain Engineering

- Transform host strain with glyoxylate pathway constructs

- For enhanced succinate accumulation, perform SDH knockout using CRISPR-Cpf1 to prevent succinate conversion to fumarate

- Verify chromosomal integration and genotype

- Screen for stable transformants

Cultivation and Analysis

- Grow engineered strains in appropriate medium (BG-11 for cyanobacteria at 38°C with continuous illumination)

- Monitor growth and metabolite production over time

- Analyze extracellular succinate accumulation

- Perform untargeted metabolomics under elevated CO₂ conditions to identify additional bottlenecks

Optimization

- Adjust cultivation parameters based on initial results

- Consider fine-tuning expression levels if needed

- Scale up promising strains to bioreactor scale

Protocol for Dual-Pathway Dynamic Regulation

Implementing Stage-Specific Pathway Activation for 5-ALA Production [23]

Materials:

- E. coli host strain

- gltX, hemA, and hemL genes for C5 pathway

- C4 pathway genes

- Quorum sensing regulatory parts

- Fed-batch fermentation system

Procedure:

Dual-Pathway Construction

- Multi-copy overexpression of native C5 pathway genes (gltX, hemA, hemL)

- Introduce inducible exogenous C4 pathway

- Enhance glutamate supply and introduce NOG pathway for improved carbon efficiency

Dynamic Regulation System

- Implement quorum sensing-based regulation of hemB

- Design system to automatically downregulate hemB at appropriate cell density

- Balance cell growth and product biosynthesis

Fermentation Strategy

- Employ controlled glycine feeding to specifically activate C4 pathway during later fermentation stage

- Use fed-batch fermentation in bioreactor (5L scale demonstrated)

- Monitor 5-ALA production throughout process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for carbon flux engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Usage | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cpf1 System | Targeted gene knockout | SDH knockout to enhance succinate accumulation [22] | More precise than traditional knockout methods |

| Non-Oxidative Glycolysis (NOG) Pathway | Enhanced acetyl-CoA supply | Betulinic acid production in Y. lipolytica [24] | Improves carbon efficiency over EMP pathway |

| Native Promoters (Pcpcb300, PpsbA1) | Regulated gene expression | Glyoxylate shunt expression in S. elongatus [22] | Prevents metabolic imbalance from strong promoters |

| Quorum Sensing Regulatory System | Dynamic pathway control | hemB regulation in 5-ALA production [23] | Automatically balances growth and production |

| NADP+-dependent Enzymes (GPD1, MCE2) | Redox engineering, NADPH regeneration | Cytosolic NADH to NADPH conversion [24] | Addresses cofactor limitations in heterologous pathways |

| Glyoxylate Shunt Enzymes (ICL, MS) | Carbon-conserving TCA cycle bypass | Succinate production in engineered cyanobacteria [22] | Bypasses decarboxylation steps, conserves carbon |

Visualization of Key Metabolic Pathways

Glyoxylate Shunt Engineering in the TCA Cycle

Multidimensional Metabolic Engineering Framework

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering continues to expand the boundaries of sustainable bioproduction. Fourth-generation biofuels exemplify this trend, utilizing genetically modified algae and photobiological solar fuels with advanced genome-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN to create exact adjustments to metabolic pathway networks [25].

Emerging strategies focus on synthetic C1 assimilation in non-model organisms, leveraging unique native metabolic properties for more sustainable bioprocesses using one-carbon substrates like methanol, formate, and CO₂ [7]. This approach aligns with circular carbon economy principles and represents the cutting edge of carbon flux engineering.

Machine learning and AI-driven optimization are increasingly employed to predict optimal enzyme combinations, pathway configurations, and cultivation parameters, accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle in metabolic engineering [25]. These computational approaches complement experimental methods described in this guide, providing powerful tools for the next generation of microbial cell factories designed for minimal byproduct formation and maximal carbon efficiency.

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists engineering microbial strains for Growth-Coupled Production (GCP). The core principle of GCP is to genetically engineer a microorganism's metabolism so that the synthesis of your target product becomes obligatory for growth. This alignment ensures that during cultivation, the fastest-growing cells are also the highest producers, thereby enhancing process stability and productivity [26] [27]. This resource, framed within a thesis on minimizing byproduct formation, provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address common experimental challenges in developing such strains.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common GCP Design and Implementation Challenges

| Problem Phenotype | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Checks | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low/No Product Yield in Coupled Strain | Incomplete gene knockout; Activation of alternative bypass pathways; Incorrect growth condition (e.g., aeration). | Verify knockouts via PCR/sequencing; Perform flux variability analysis on model; Check for unexpected byproducts in supernatant. | Reconstruct knockout mutant; Use M-model to find and knock out alternative pathways [28]; Re-run simulation for current condition. |

| Poor Microbial Growth Post-Engineering | Overly restrictive metabolism; Accumulation of toxic intermediates; High metabolic burden from synthetic pathways. | Measure growth rate vs. wild-type; Check for metabolite secretion not in model; Model enzyme usage cost with ME-model [28]. | Use ME-model to assess enzyme cost and identify bottlenecks [28]; Supplement medium with essential metabolites if model allows. |

| Strain Instability & Loss of Coupling | Emergence of suppressor mutations; Non-growth-coupled subpopulations; Genetic reversion. | Sequence evolved strain to find new mutations; Single-colony isolation and productivity screening. | Increase coupling strength by adding knockouts from cMCS calculation [29] [27]; Use adaptive laboratory evolution to enforce coupling. |

| Unpredicted Byproduct Formation | Model incompleteness; Incorrect constraints on exchange reactions; Regulation not captured by model. | Metabolomics analysis of culture supernatant; Check model for missing reactions. | Add constraints to model and re-compute design; Knock out genes responsible for new byproduct formation. |

Computational Design Troubleshooting

| Computational Issue | Root Cause | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| No Feasible GCP Solution Found | The required product yield is set too high; The metabolic network cannot support coupling for the target metabolite. | Lower the minimum product yield threshold (e.g., from 50% to 30% of theoretical max) and re-run the algorithm [27]. |

| Solution Suggests Excessively High Number of Knockouts | The algorithm finds a complex, non-minimal solution. | Use a cMCS extraction step to iteratively remove non-essential knockouts from the solution set [29]. |

| Model Predicts Growth, but In Vivo Strain Does Not Grow | The in silico model does not fully capture all biological constraints, such as enzyme kinetics or regulatory effects. | Use a Metabolism and Gene Expression (ME) model to account for biosynthetic costs of the proteome and refine the design [28]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

GCP Strategy and Design

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between weak, holistic, and strong growth-coupling? These terms describe the strength of the coupling between growth and production, visualized by the production envelope [30]:

- Weak GC (wGC): Production occurs only at elevated growth rates, but can be zero at lower growth rates.

- Holistic GC (hGC): The minimum production rate is above zero for all growth rates greater than zero.

- Strong GC (sGC): Production is mandatory even when growth is zero (i.e., during substrate consumption without growth). This is the most robust form of coupling and requires a positive constraint on the ATP maintenance requirement (ATPM) reaction in silico [30].

Q2: For which metabolites can growth-coupled production be engineered? Theoretical and computational studies demonstrate that strong growth-coupled production is feasible for the vast majority of metabolites producible from a substrate in major production organisms. One study found suitable intervention strategies for over 96% of metabolites in E. coli and S. cerevisiae under aerobic conditions [27].

Q3: What are the main metabolic principles used to enforce growth-coupling? Two major underlying principles have been identified [30]:

- Essential Carbon Drain: Curtailing the metabolic network to make product formation an essential sink for carbon, often by controlling the consumption of key intermediates like pyruvate.

- Cofactor/Energy Imbalance: Designing the network such that balancing energy (ATP) or redox (NADH) cofactors is impossible without producing the target molecule. This principle is particularly effective under anaerobic conditions where ATP generation pathways are limited.

Experimental Implementation

Q4: My engineered GCP strain grows very slowly. What could be wrong? Slow growth often indicates an overly restrictive metabolism or high metabolic burden. Diagnose this by:

- In Silico Check: Ensure your engineered model still predicts a reasonable growth rate. If not, the design may be too restrictive.

- Experimental Check: Use metabolomics to check for the accumulation of toxic intermediates not accounted for in the model.

- Burden Check: Consider using an ME-model to evaluate if the metabolic flux demands an unsustainably high enzyme production cost [28]. A solution may be to relax the coupling strength or supplement the medium with critical metabolites.

Q5: How can I improve the stability of my production strain and prevent non-producers from taking over? The primary goal of GCP is to stabilize production. If instability is observed:

- Strengthen the Coupling: Ensure you have implemented a strong coupling strategy. Non-producers emerge when there is a feasible metabolic state that allows for growth without production. Re-evaluate your design using RobustKnock or gcOpt algorithms that maximize the minimum guaranteed production rate [30] [31].

- Use Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Subject your GCP strain to serial passaging, always selecting for the fastest-growing cells. In a properly growth-coupled strain, ALE will simultaneously select for improved growth and higher production [28] [27].

Q6: How can I minimize the formation of unwanted byproducts in my GCP strain? Byproduct formation is a classic failure mode of GCP designs.

- Computational Filtering: During the in silico design phase, use methods like RobustKnock or kinetic parameter sampling with a ME-model to identify and filter out strain designs that are susceptible to alternative production phenotypes [28].

- Identify and Knock Out: If byproducts appear experimentally, identify them analytically, then return to the metabolic model to find reaction knockouts that disable their production while maintaining the core growth-coupling.

Key Computational Tools and Methods

| Algorithm Name | Core Principle | Key Feature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OptKnock | Bilevel optimization: Maximizes product yield while model optimizes for growth. | First computational method for GCP strain design. | [31] |

| RobustKnock | Bilevel max-min optimization: Maximizes the minimum guaranteed production at max growth. | Identifies strategies less susceptible to alternative sub-optimal pathways. | [31] |

| cMCS (Constrained Minimal Cut Sets) | Identifies minimal reaction sets to knock out to disable all low-yield modes while retaining high-yield modes. | Directly enforces a desired phenotype by cutting unwanted network functionalities. | [29] [27] |

| gcOpt | Maximizes the minimally guaranteed production rate at a fixed, medium growth rate. | Prioritizes designs with elevated growth-coupling strength across a range of growth rates. | [30] |

| OptEnvelope | User selects a target (growth, production) point; finds minimal active reactions to support it. | Target-point oriented; allows user to directly aim for a desired operational point. | [31] |

Standard Protocol: Checking Feasibility of GCP using cMCS

This protocol, based on established procedures [29], tests if strong growth-coupling is possible for a metabolite.

Objective: To determine if a set of reaction knockouts exists that enforces strong coupling for a target metabolite at a specified minimum yield.

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Use a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli). Set substrate uptake (e.g., glucose) to a fixed value and allow unlimited uptake of essential inorganics. Define a non-zero ATP maintenance (ATPM) requirement.

- Identify Candidate Metabolite: Add an export reaction for the target metabolite if it doesn't exist.

- Calculate Maximum Yield: Maximize the flux through the product exchange reaction. The carbon yield (mmol C in product / mmol C in substrate) is the theoretical maximum yield (Ymax).

- Set Minimum Yield Threshold: Define the desired coupling yield (e.g., 10%, 30%, or 50% of Ymax).

- Formulate MILP Problem: Set up a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming problem to find a cut set (reaction knockouts) where:

- Desired behavior is feasible: A flux distribution exists with growth rate > 0 and product yield > minimum threshold.

- Undesired behavior is infeasible: No flux distribution exists with product yield < minimum threshold.

- Solve and Validate: Run the MILP solver. If a solution (cut set) is found, verify with separate Linear Programming (LP) problems that the knockouts indeed enforce the desired coupling.

- Extract cMCS: The found cut set may not be minimal. Iteratively remove each knockout and check if coupling is maintained to find the smallest set of required interventions (the cMCS).

Workflow Diagram: Integrated Computational & Experimental GCP Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Key Reagents for GCP Strain Construction and Validation

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (M-model) | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes and identification of knockout targets. | iJO1366 for E. coli; iMM904 for S. cerevisiae [28] [31]. |

| ME-model (Metabolism & Expression) | Advanced modeling that includes enzyme costs and gene expression constraints for more realistic predictions. | iLE1678-ME for E. coli; used to filter out designs with high protein burden [28]. |

| Knockout Library Strains | Pre-constructed single- or multiple-gene deletion mutants for rapid experimental validation. | Keio collection (E. coli) or EUROSCARF ( S. cerevisiae). |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precise, multiplexed genome editing for simultaneous knockout of multiple target reactions. | Essential for implementing complex cMCS strategies involving 3-5 knockouts. |

| HPLC/GC-MS System | Analytical quantification of target product and key byproducts in culture supernatant. | Critical for validating in silico predictions and diagnosing failed couplings. |

| Chemostat/Turbidostat | Continuous cultivation system for performing Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE). | Enforces selection for growth, thereby improving productivity in GCP strains [26]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q: My CRISPR experiment resulted in very low editing efficiency in my microbial culture. What are the primary factors I should investigate?

A: Low editing efficiency is a common challenge. Focus on these key areas:

- Guide RNA (gRNA) Design: Ensure your gRNA has high predicted on-target activity. Use design software to select a gRNA with minimal off-target sites in your specific microbial genome. The target sequence must be adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) that your Cas enzyme recognizes (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [32] [33].

- Delivery System Efficiency: The method used to get CRISPR components into your cells is critical. For hard-to-transfect microbes, consider optimizing electroporation conditions or using viral vectors suitable for your organism [33].

- Cas9 Expression and Version: Verify the promoter driving Cas9 expression is functional in your host microbe. Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) to improve specificity, though they may have slightly reduced activity [34] [33].

Q: How can I minimize the formation of unintended byproducts like large genomic deletions or translocations during editing?

A: Beyond classic off-target effects, recent studies highlight the risk of larger structural variations (SVs) [34]. To minimize these byproducts:

- Avoid DNA-PKcs Inhibitors: Do not use small-molecule inhibitors like AZD7648 to promote Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). These can dramatically increase the frequency of kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [34].

- Choose the Right Editor: For single nucleotide changes, use base editing or prime editing systems that do not create full double-strand breaks, thereby significantly reducing the risk of SVs [35] [36].

- Validate with Long-Read Sequencing: Standard short-read sequencing can miss large deletions. Use long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to fully characterize editing outcomes and detect any major structural aberrations [34].

Q: My HDR efficiency is very poor, leading to a high proportion of indels instead of precise edits. How can I improve this?

A: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) often outcompetes HDR. To tilt the balance:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: HDR is most active in the S and G2 phases. Synchronizing your cell culture can enrich for cells proficient in HDR [34].

- Use Nicksase Strategies: Using a Cas9 nickase (Cas9n) with a pair of adjacent gRNAs creates two single-strand breaks instead of one double-strand break, which can promote repair pathways with higher fidelity than NHEJ, though it does not eliminate SV risks entirely [34] [33].

- Optimize the Repair Template: Ensure your donor DNA template has sufficiently long homology arms (specifics vary by organism) and is delivered in high molar excess relative to the CRISPR machinery [33].

Q: What are the critical steps for validating my edit and ensuring no off-target effects in a synthetic biology context?

A: Thorough validation is essential for both research accuracy and future therapeutic applications.

- On-Target Validation: Use Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) of PCR amplicons spanning the target site to confirm the intended edit is present [33].

- Off-Target Assessment: In silico prediction tools can identify potential off-target sites for PCR validation. For a comprehensive profile, especially in a clonal population, use genome-wide methods like CAST-Seq or LAM-HTGTS, which are sensitive enough to detect chromosomal translocations and other SVs [34].

- Phenotypic Screening: Beyond genetic validation, conduct functional assays to confirm the desired metabolic or phenotypic change has occurred without unexpected secondary effects, which could indicate disruptive off-target edits [37].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Basic CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout in Microbes

Objective: To permanently disrupt a target gene in an engineered microbe via NHEJ-mediated indel formation.

Materials:

- Plasmid vectors expressing a microbial-specific promoter driving Cas9 and your gRNA.

- Repair template (for HDR-based edits).

- Equipment for microbial transformation (e.g., electroporator).

- Agar plates with appropriate selection antibiotics.

- PCR thermocycler and Sanger sequencing capabilities.

Methodology:

- gRNA Design and Cloning: Design a gRNA targeting an early, constitutive exon of your target gene using specialized software. Synthesize the oligos, anneal them, and clone them into your gRNA expression plasmid [33].

- Delivery: Co-transform your microbial host with the Cas9 expression plasmid and the gRNA plasmid using your optimized method (e.g., electroporation) [33].

- Selection and Screening: Plate transformed cells on selective media. Pick individual colonies and inoculate them in culture for genomic DNA extraction.

- Validation: Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze the products. A successful knockout will show a mixture of indel mutations, detectable by Sanger sequencing (seen as messy chromatograms after the cut site) or more clearly by NGS. Verify the loss of protein function through a phenotypic assay [33].

Protocol for Prime Editing to Minimize Byproducts

Objective: To introduce a precise point mutation without creating a double-strand break, thereby minimizing indels and structural variations.

Materials:

- Prime Editor plasmid (e.g., expressing Cas9 nickase-reverse transcriptase fusion).

- Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA) plasmid. The pegRNA contains both the spacer sequence and the template for the new edit [35] [36].

- Delivery materials (e.g., electroporation kit for your microbe).

Methodology: