Metabolic Engineering for Renewable Resource Utilization: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolic engineering strategies for the efficient utilization of renewable resources, with a focus on lignocellulosic biomass.

Metabolic Engineering for Renewable Resource Utilization: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolic engineering strategies for the efficient utilization of renewable resources, with a focus on lignocellulosic biomass. It explores foundational concepts of microbial biocatalysts, details advanced methodological frameworks including computational design and genetic tools like CRISPR/Cas9, and addresses critical troubleshooting for process optimization. By synthesizing validation techniques and comparative analyses of microbial hosts, the content offers researchers and scientists in biotechnology and drug development a structured guide to developing robust, economically viable bio-based production processes for fuels and chemicals.

Harnessing Nature's Bounty: Foundational Principles of Renewable Feedstocks and Microbial Biocatalysts

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), the most abundant renewable resource on Earth, represents a critical pillar in the global transition toward sustainable bioeconomies and a viable alternative to fossil-based resources [1]. With an astonishing annual production rate of 181.5 billion tons worldwide, this plant-based material holds immense potential for producing biofuels, biochemicals, and biomaterials through modern biorefining techniques [2]. The significance of LCB extends beyond its abundance; its utilization offers a carbon-neutral pathway for energy and chemical production, as the carbon dioxide released during its conversion is approximately equal to the amount absorbed by plants during growth [3]. This review examines the composition, abundance, and multifaceted potential of LCB, with a specific focus on its role as a feedstock for metabolic engineering applications aimed at renewable resource utilization.

Composition and Global Availability

Structural Components

LCB primarily consists of three key structural polymers that form a complex, recalcitrant matrix in plant cell walls. The composition varies based on plant source, geographical location, and growing conditions, but generally falls within the ranges shown in Table 1 [4].

Table 1: Typical composition of lignocellulosic biomass components

| Component | Chemical Characteristic | Percentage of Dry Weight (%) | Function in Plant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Linear polymer of β-D-glucopyranose units with β-1,4-glycosidic bonds [4] | 35–52% [5] | Provides structural strength and stability |

| Hemicellulose | Branched heteropolymer of various sugars (xylose, arabinose, mannose, etc.) [4] | 20–35% [5] | Binds cellulose and lignin, contributes to strength |

| Lignin | Complex, cross-linked phenolic polymer from phenylpropane units [4] | 10–25% [5] | Provides rigidity, waterproofing, and microbial resistance |

This structural complexity contributes to the recalcitrance of LCB, presenting a significant challenge for its efficient deconstruction and conversion into valuable products [4]. Lignin, in particular, acts as a protective barrier by forming covalent cross-links with hemicellulose and surrounding cellulose microfibrils, creating a robust lignocellulosic matrix that resists microbial and enzymatic degradation [4] [6].

The global generation of LCB is substantial, with agricultural residues constituting a major component. Table 2 quantifies the annual availability of key agricultural waste feedstocks, highlighting the scale of this renewable resource [5].

Table 2: Global annual generation of major agricultural residues

| Agricultural Residue | Annual Generation (Million Tons) |

|---|---|

| Wheat Straw | ~350 |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 279–300 |

| Corn Stover | ~170 |

| Rice Husk | ~101.8 |

LCB sources are categorized based on their origin. Agricultural residues (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover, sugarcane bagasse) and forestry residues represent the most immediate and sustainable feedstocks, as they utilize existing waste streams without competing with food production [7] [1]. Dedicated energy crops (e.g., switchgrass, miscanthus) and industrial processing by-products (e.g., sawdust, pulp residues) further expand the diverse feedstock base for biorefineries [3].

The global lignocellulosic biomass market is projected to grow significantly, from USD 4.61 billion in 2025 to USD 9.76 billion by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% and underscoring its increasing economic importance [3].

Applications and Conversion Pathways in Metabolic Engineering

From Biofuels to High-Value Chemicals

Metabolic engineering has enabled the microbial conversion of LCB-derived sugars into a wide spectrum of valuable products, moving beyond first-generation biofuels to include high-value chemicals and materials.

Table 3: Selected high-value chemicals produced from lignocellulosic biomass via metabolic engineering

| Product | Microbial Host(s) | Production Titer (from LCB) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid | Actinobacillus succinogenes, Basfia succiniciproducens [2] | 1.07–40.2 g/L [2] | Platform chemical for 1,4-butanediol, biodegradable polymers [2] |

| Lactic Acid | Lactobacillus spp., Bacillus coagulans [2] | 4.4–129.47 g/L [2] | Bioplastics (PLA), food industry [2] |

| Xylitol | Candida tropicalis, Kluyveromyces marxianus [2] | 24.2–109.5 g/L [2] | Food sweetener, dental health products [2] |

| 2,3-Butanediol | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Paenibacillus polymyxa [2] | 10.30–75.03 g/L [2] | Chemical feedstock for synthetic rubber, plastics [2] |

The conversion process typically involves several key steps: pretreatment to disrupt the lignocellulosic matrix, enzymatic hydrolysis to depolymerize cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars (e.g., glucose and xylose), and microbial fermentation by engineered strains to convert these sugars into target products [8]. A major focus of metabolic engineering is developing robust microbial cell factories capable of efficiently utilizing all the sugar monomers present in LCB hydrolysates, particularly the hemicellulose-derived pentose sugars like xylose, while tolerating inhibitors generated during pretreatment [9] [2].

Metabolic Pathways for Sugar Utilization

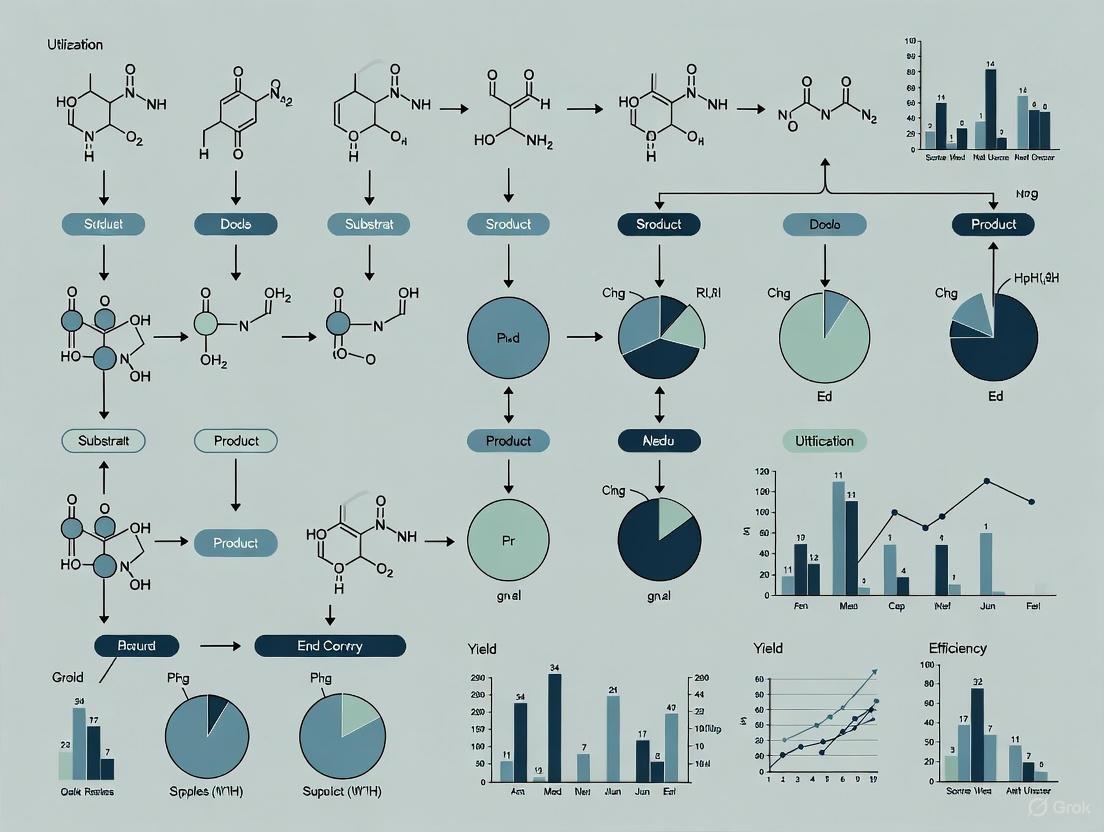

Engineered microorganisms catabolize LCB-derived sugars through central metabolic pathways. The following diagram illustrates the key pathways involved in the conversion of glucose and xylose into representative high-value chemicals.

Figure 1: Key Metabolic Pathways for LCB Sugar Conversion. This diagram outlines the central metabolic routes through which engineered microbes convert glucose and xylose from LCB into platform chemicals. Abbreviations: P (Phosphate), TCA (Tricarboxylic Acid), PPP (Pentose Phosphate Pathway).

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Consolidated Bioprocessing Workflow for Chemical Production

The following protocol outlines a generalized workflow for the microbial production of high-value chemicals (e.g., succinic acid) from LCB, integrating pretreatment, hydrolysis, and fermentation.

Figure 2: Consolidated Bioprocess Workflow from LCB to Product.

Protocol 1: Production of Succinic Acid from LCB Hydrolysate

Key Materials:

- Feedstock: Milled wheat straw or corn stover (particle size ~2 mm)

- Microorganism: Engineered Actinobacillus succinogenes or Basfia succiniciproducens [2]

- Enzymes: Commercial cellulase cocktail (e.g., from Trichoderma reesei) and β-glucosidase

- Chemicals: For fermentation medium and analytical standards

Procedure:

Pretreatment:

- Employ a dilute acid pretreatment using 1-2% (w/v) sulfuric acid at 160-180°C for 30-60 minutes with a solid loading of 10-20% (w/v) [7] [5].

- Neutralize the slurry to pH ~6.0-7.0 using calcium carbonate or sodium hydroxide.

- Alternatively, for a milder approach, biological pretreatment with lignin-degrading fungi (e.g., Ceriporiopsis subvermispora) can be applied for 2-4 weeks [6].

Enzymatic Hydrolysis:

- Suspend the pretreated biomass in a citrate buffer (pH 4.8-5.0) at 5-10% solid loading.

- Add cellulase enzymes (e.g., 15-20 FPU/g dry biomass) and β-glucosidase (e.g., 15-30 CBU/g dry biomass).

- Incubate at 50°C with agitation (150-200 rpm) for 48-72 hours [6].

Inoculum Preparation:

- Grow the production strain (e.g., A. succinogenes) in a rich medium (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth) for 12-16 hours.

- Centrifuge and resuspend the cells in sterile saline to an OD600 of ~10-20 for inoculation.

Fermentation:

- Use a bioreactor containing the sterile fermentation medium (e.g., containing yeast extract, salts, and neutralizing agent like MgCO₃).

- Add the sugar hydrolysate (filter-sterilized) as the primary carbon source.

- Inoculate at 5-10% (v/v) with the prepared cell suspension.

- Conduct fermentation under controlled conditions: temperature 37°C, pH 6.5-7.0 (maintained with Na₂CO₃ or NaOH), and moderate agitation. Anaerobic or microaerobic conditions are often required [2].

- Monitor sugar consumption and product formation over 48-96 hours.

Product Analysis:

- Withdraw samples periodically and centrifuge to remove cells.

- Analyze the supernatant using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a UV/RI detector and a suitable column (e.g., Aminex HPX-87H for organic acids) to quantify succinic acid, byproducts, and residual sugars [2].

Protocol for Advanced Biosensor-Enabled High-Throughput Screening

This protocol utilizes biosensors to rapidly identify high-performing microbial variants, a cutting-edge tool in metabolic engineering for optimizing LCB conversion [8].

Protocol 2: Biosensor-Mediated Screening for Enhanced Xylitol Production

Key Materials:

- Biosensor Strain: Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Candida tropicalis with a xylose-responsive transcription factor (e.g., based on Gal4 in S. cerevisiae) regulating a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) [8].

- Induction Molecule: Xylose or xylitol.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer or microplate fluorometer.

Procedure:

Library Construction:

- Generate a diverse library of microbial variants through random mutagenesis (e.g., UV, chemical mutagens) or targeted genetic engineering (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9) of genes in the xylose assimilation pathway.

Cultivation and Induction:

- Grow the biosensor strain library in a minimal medium with a low, non-saturating concentration of xylose (or xylitol) as the inducer.

- For high-throughput screening, cultivate cells in 96-well or 384-well deep-well plates.

Signal Detection and Sorting:

- After sufficient growth (mid-log phase), measure the fluorescence intensity of individual cells using a flow cytometer or well-level fluorescence using a microplate reader.

- The fluorescence signal is directly correlated with the intracellular concentration of the target metabolite (xylose/xylitol) or the flux through the pathway, serving as a proxy for productivity.

Variant Isolation and Validation:

- Use the flow cytometer to sort the top 0.1-1% of the population with the highest fluorescence intensity.

- Plate the sorted cells on solid medium to obtain single colonies.

- Validate the performance of the isolated variants in shake-flask fermentations using real LCB hydrolysate, quantifying final xylitol titer, yield, and productivity using HPLC as described in Protocol 1 [8] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key research reagents and materials for LCB conversion research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase from Trichoderma reesei | Hydrolyzes cellulose to cellobiose and glucose | Activity: ≥700 units/g [6] |

| β-Glucosidase from Aspergillus niger | Hydrolyzes cellobiose to glucose, relieving end-product inhibition | Activity: ≥250 units/g [6] |

| Xylanase | Hydrolyzes hemicellulose (xylan) into xylose | Activity: ≥1000 units/g [6] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Genome editing tool for metabolic engineering of microbial hosts | Includes Cas9 nuclease and sgRNA for target gene knockout/knock-in [1] |

| Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor | Real-time monitoring and high-throughput screening of metabolite production | e.g., Xylose-responsive biosensor with GFP output [8] |

| Lignin-Degrading Fungi | Biological pretreatment to delignify biomass | e.g., Ceriporiopsis subvermispora, Phanerochaete chrysosporium [6] |

| HPLC Column (Aminex HPX-87H) | Analytical separation and quantification of sugars, organic acids, and inhibitors | Column size: 300 x 7.8 mm; Operating Temp: 45-65°C [2] |

| Oleaginous Yeast Strains | Microbial platforms for lipid accumulation from LCB sugars for biodiesel | e.g., Yarrowia lipolytica, Rhodotorula toruloides [6] |

Lignocellulosic biomass stands as a cornerstone for a sustainable bio-based economy, offering a vast and renewable carbon source to decarbonize energy and industrial sectors. Its complex composition, while presenting a challenge of recalcitrance, is also the source of its rich potential, providing the foundational polymers for a diverse array of fuels, chemicals, and materials. Advances in metabolic engineering, particularly the development of robust microbial cell factories and the integration of tools like biosensors and CRISPR-based genome editing, are pivotal to unlocking this potential. By providing detailed protocols and a toolkit for researchers, this application note underscores the practical pathways toward harnessing LCB, aligning with the broader thesis of advancing metabolic engineering for the efficient and sustainable utilization of renewable resources.

The efficient utilization of lignocellulosic biomass is fundamental to developing a sustainable bioeconomy. Lignocellulose, the most abundant renewable organic resource on earth, consists of approximately 25% lignin and 75% carbohydrate polymers (cellulose and hemicellulose) [10]. While cellulose is a glucose polymer, hemicellulose is a heteropolymer containing significant amounts of pentose sugars, primarily xylose and arabinose [11] [10]. In fact, xylose is the second most abundant sugar in nature after glucose [10]. The economic viability of lignocellulosic biorefineries depends critically on the complete utilization of all sugar components, making the bioconversion of pentose sugars a central challenge in metabolic engineering and renewable resource utilization [12] [10]. This application note provides detailed methodologies and experimental frameworks for addressing this challenge, with a focus on engineering robust microbial catalysts.

Background and Significance

Lignocellulosic biomass represents a promising alternative for sustainable energy and industrial applications, with potential to displace 30% of fossil fuel consumption [1]. The United States alone could potentially convert 2.45 billion metric tons of biomass to 270 billion gallons of ethanol annually—approximately twice the annual gasoline consumption [10]. Efficient utilization of the hemicellulose component could reduce the cost of producing fuel ethanol by 25% [10].

However, a significant bottleneck exists: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the most established industrial fermentation yeast, cannot naturally metabolize pentose sugars [11] [13] [14]. This limitation represents a substantial economic hurdle, as pentose sugars can constitute 10-35% of the total carbohydrate content in lignocellulosic feedstocks [10]. The development of robust microorganisms capable of efficient fermentation of all sugar types is therefore essential to underpin the economic production of biofuels and bio-based chemicals from biomass feedstocks [11] [14].

Pentose Sugar Metabolism Pathways

Microorganisms employ distinct pathways for pentose metabolism, primarily differing between bacteria and fungi:

- Bacterial Pathway: Xylose is directly converted to xylulose by a xylose isomerase (EC 5.3.1.5) and subsequently phosphorylated by xylulokinase (EC 2.7.1.17) to yield D-xylulose-5-phosphate, which enters the pentose phosphate pathway [11].

- Fungal Pathway: Xylose is first reduced to xylitol by a reductase (XR) and then oxidized to xylulose by a dehydrogenase (XDH) before phosphorylation by xylulokinase (XK) [11] [13]. This pathway creates a redox cofactor imbalance because the reductase typically uses NADPH while the dehydrogenase uses NAD+, leading to xylitol accumulation under anaerobic conditions [11].

Metabolic Engineering Strategies and Protocols

This section outlines core strategies and detailed experimental protocols for engineering pentose fermentation capabilities into industrial microorganisms.

Engineering the Xylose Assimilation Pathway inS. cerevisiae

Objective: To introduce and optimize a functional xylose metabolic pathway in S. cerevisiae.

Background: The fungal XR-XDH pathway from native pentose-fermenting yeasts like Scheffersomyces stipitis (formerly Pichia stipitis) is commonly introduced into S. cerevisiae [11] [15].

Protocol 3.1.1: Heterologous Gene Expression

- Gene Cloning: Amplify coding sequences for XYL1 (xylose reductase), XYL2 (xylitol dehydrogenase) from S. stipitis, and the endogenous XYL3 (xylulokinase) from S. cerevisiae.

- Vector Construction: Clone genes into a multi-copy expression vector under the control of strong, constitutive yeast promoters (e.g., PGK1, TEF1). A common strategy is to create a polycistronic expression cassette.

- Yeast Transformation: Introduce the construct into an industrial S. cerevisiae strain using standard lithium acetate transformation.

- Selection and Screening: Select transformants on synthetic complete medium lacking uracil (if using URA3 selection) and screen for growth on minimal plates with 2% xylose as the sole carbon source.

Protocol 3.1.2: Addressing Cofactor Imbalance via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

- Rational Design: The cofactor preference of Xylose Reductase (XR) can be altered from NADPH to NADH through specific point mutations. The mutation K270M in P. stipitis XR reduces its affinity for NADPH [11]. Double mutants like K274R+N276D in C. tenuis XR show a more complete reversal of coenzyme preference [11].

- Mutagenesis: Perform site-directed mutagenesis on the XYL1 gene in your expression vector using a commercial kit (e.g., QuikChange). The primer pair for the K270M mutation should be:

5'-GTG GTT [A→G at codon 270, AAG→ATG] GCT AAC -3'(forward) and its reverse complement. - Validation: Sequence the entire XYL1 gene to confirm the intended mutation and absence of PCR errors.

- Functional Analysis: Compare the ethanol yield and xylitol production of strains expressing wild-type vs. mutated XR in fermentation assays (see Protocol 4.1).

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Strain Robustness

Objective: To improve the fermentation performance and inhibitor tolerance of engineered strains in lignocellulosic hydrolysates.

Background: ALE enriches for spontaneous mutants with improved phenotypes under selective pressure [15].

- Protocol 3.2.1: Serial Transfer in Hydrolysate

- Medium Preparation: Prepare a fermentation medium containing 80% (v/v) undetoxified, enzymatically saccharified hydrolysate (e.g., from Ammonia Fiber Expansion-pretreated corn stover or dilute acid-pretreated switchgrass) [15]. Supplement with necessary nitrogen sources to a carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of 37:1 to 42:1 [15].

- Inoculation and Cultivation: Inoculate the engineered S. cerevisiae strain into 5 mL of the medium in a shake flask. Incubate at 30°C with shaking.

- Serial Transfer: Once the culture reaches mid-log phase (OD600 ~ 4-6), transfer 0.5 mL into 4.5 mL of fresh, pre-warmed medium. Repeat this transfer for 50-100 generations.

- Selection Pressure: Periodically introduce additional stresses, such as 4% (v/v) ethanol or incremental increases in hydrolysate concentration, to select for robust mutants.

- Isolation and Archiving: At regular intervals, plate the culture on YM agar to obtain single colonies. Archive intermediate populations and isolates in 10% glycerol at -80°C.

Deletion of Competing Pathways

Objective: To minimize byproduct formation and redirect carbon flux toward ethanol.

- Protocol 3.3.1: GRE3 Deletion

- Rationale: The native S. cerevisiae aldose reductase (encoded by GRE3) reduces xylose to xylitol, contributing to byproduct loss, especially when a xylose isomerase pathway is used [11].

- Deletion Cassette: Design a deletion cassette containing a selectable marker (e.g., KanMX) flanked by ~500 bp homology arms upstream and downstream of the GRE3 open reading frame.

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the cassette into the engineered yeast strain. Verify correct gene replacement via PCR and phenotype (reduced xylitol production on xylose plates).

The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic pathways and engineering targets for enabling xylose fermentation in S. cerevisiae.

Analytical Methods and Data Presentation

Rigorous analytical methods are required to evaluate the performance of engineered strains.

Fermentation Performance Assay

Objective: To quantitatively measure sugar consumption and product formation kinetics.

- Protocol 4.1.1: Anaerobic Batch Fermentation

- Setup: Use 250 mL baffled shake flasks with rubber stoppers and airlocks filled with 100 mL of defined medium (e.g., ODM [15]) containing 20 g/L glucose and 50 g/L xylose. Inoculate with an initial OD600 of 1.0.

- Conditions: Incubate at 30°C with magnetic stirring at 150 rpm. Maintain anaerobic conditions by sparging the headspace with nitrogen gas.

- Sampling: Take 1 mL samples every 3-6 hours over a 72-hour period. Centrifuge to separate cells from supernatant.

- Analysis:

- Sugars and Alcohols: Analyze supernatant by HPLC equipped with a refractive index detector and a Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H column (or equivalent). Use 5 mM H₂SO₄ as mobile phase at 0.6 mL/min, 65°C.

- Cell Growth: Monitor optical density at 600 nm (OD600) from the cell pellet.

The table below summarizes typical performance metrics for different engineered strains, highlighting the impact of various metabolic engineering strategies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Engineered S. cerevisiae Strains for Xylose Fermentation

| Engineering Strategy | Key Genetic Modifications | Ethanol Yield (g/g xylose) | Xylitol Yield (g/g xylose) | Maximum Ethanol Titer (g/L) | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XR-XDH (Wild-type) | XYL1, XYL2, XYL3 from P. stipitis | ~0.30 | ~0.50 | 10-15 | Baseline strain [11] |

| XR-XDH (Cofactor Engineered) | XYL1 (K274R+N276D mutant from C. tenuis), XYL2, XYL3 | ~0.42 (42% increase) | ~0.15 (70% decrease) | 15-20 | Improved yield & reduced byproduct [11] |

| Xylose Isomerase (XI) | XYLA (from Piromyces sp.), ΔGRE3 | ~0.35 | Low | 10-15 | Avoids redox issue, but low activity [11] |

| ALE-Improved Strain | Base XR-XDH pathway + 50-100 gen ALE in hydrolysate | ~0.39 | ~0.20 | >40 | High titer & inhibitor tolerance [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pentose Fermentation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate | Authentic fermentation substrate containing inhibitors and mixed sugars. | AFEX-pretreated Corn Stover Hydrolysate (AFEX CSH) or Dilute Acid Pretreated Switchgrass Hydrolysate Liquid (PSGHL) [15]. |

| Defined Synthetic Medium (ODM) | Controlled fermentation studies and pre-culture preparation. | Optimal Defined Medium for S. stipitis; allows precise control of carbon and nitrogen sources [15]. |

| Nitrogen Supplements (N1, N2) | Provide essential nutrients in hydrolysate medium for robust fermentation. | N1: Defined amino acids & vitamins. N2: Cost-effective urea & soy flour [15]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision genome editing (e.g., gene knockouts, promoter swaps). | Enables deletion of GRE3 or integration of heterologous pathways [1] [16]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Engineering enzyme properties (e.g., cofactor preference of XR). | Commercial kits (e.g., QuikChange) for creating point mutations like XR K270M [11]. |

| HPLC with RI/UV Detector | Quantification of sugars, alcohols, and organic acids in fermentation broth. | Essential for calculating yields and productivities. Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H column is standard. |

The bioconversion of pentose sugars from hemicellulose remains a critical frontier in metabolic engineering for renewable resource utilization. Success hinges on integrated strategies that combine pathway engineering to establish functional xylose assimilation, redox balancing to minimize byproduct formation, and adaptive evolution to enhance strain robustness in industrial-relevant conditions. The protocols and data presented herein provide a foundational framework for researchers to develop next-generation microbial biocatalysts, ultimately advancing the economic viability of lignocellulosic biorefineries and contributing to a more sustainable bio-based economy. Future work will increasingly leverage synthetic biology tools like CRISPR and machine learning to further optimize these complex traits [1].

In the pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing, the engineering of microbial chassis—cellular hosts engineered to function as platforms for biochemical production—has become a cornerstone of metabolic engineering. These chassis are indispensable in microbial production as introduced heterologous pathways often fail to function optimally in wild-type strains [17]. The selection and systematic engineering of these platform biocatalysts enable the efficient conversion of renewable resources into value-added chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals, supporting the transition toward a circular bioeconomy.

The most commonly utilized chassis organisms include the bacterium Escherichia coli and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, favored for their well-characterized genetics and extensive engineering toolkits [17] [18]. However, the field is increasingly expanding to non-model hosts such as Pseudomonas putida, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Yarrowia lipolytica, and various lactic acid bacteria, chosen for their unique native metabolic capabilities, robustness, and tolerance to industrial process conditions [17] [19] [18]. The core principle involves reprogramming these microorganisms through genetic modifications to enhance the supply of metabolic precursors, balance energy cofactors, functionally express heterologous pathway enzymes, and improve the influx of substrates and efflux of target products [17] [20].

Host Selection and Evaluation

Criteria for Chassis Selection

Selecting an appropriate microbial host is a critical first step, guided by the specific demands of the bioprocess and the target product. The ideal chassis should possess a combination of physiological, metabolic, and genetic traits conducive to large-scale production.

Key selection criteria include:

- Physiological Nature: Tolerance to high product concentrations, heat, and other environmental stresses is crucial for achieving high titers [17]. A robust cell envelope is necessary to withstand harsh industrial conditions, including shear forces [18].

- Metabolic Potential: The host should have an abundant supply of key intracellular precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis) and redox cofactors (e.g., NADPH) required for the target pathway [17] [20].

- Substrate Utilization Range: The ability to grow on inexpensive, non-food, or waste feedstocks, such as one-carbon (C1) compounds (methanol, CO2), glycerol, or aromatic compounds, enhances sustainability [19] [21].

- Genetic Accessibility: The availability of a complete genome sequence, well-developed genetic modification tools, and a deep understanding of its regulatory network are fundamental for efficient engineering [17] [22].

- Lifestyle and Process Compatibility: The host's oxygen requirement (aerobic, anaerobic, or facultative) must align with the planned fermentation mode [19] [18].

Comparative Analysis of Microbial Chassis

The table below summarizes the properties and applications of prominent bacterial and yeast chassis organisms.

Table 1: Properties and Applications of Selected Microbial Chassis

| Organism | Gram/ Type | Lifestyle | Native Advantages / Key Applications | Notable Engineering Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Gram-negative | Chemoheterotroph, Facultative Anaerobe | Fast growth, extensive genetic tools, production of small molecules and proteins [17] [18] | Fully synthetic E. coli with a recoded 4-Mb genome for improved genetic stability [17] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Gram-negative | Aerobic | Metabolic diversity, robust cell envelope, high stress tolerance, bioremediation [19] [18] | Large-scale genomic deletions yielding cells with robust growth and simplified metabolism [18] [22] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Gram-positive | Aerobic | Amino acid production, naturally low endotoxin, robust industrial host [17] | Engineered for production of stilbenes and (2S)-flavanones [17] |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | Gram-positive | Anaerobic | Solvent production (acetone, butanol), biofuels from complex feedstocks [18] | --- |

| Bacillus subtilis | Gram-positive | Aerobic | High extracellular protein secretion, low immunogenicity, enzyme production [17] [22] | Engineered delta6, MG1M, and MGB874 strains for enhanced protein productivity [22] |

| Lactococcus lactis | Gram-positive | Facultative Anaerobe | Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS), food-grade, probiotic, vaccine delivery [22] | Genome-reduced strain with 6.9% deletion showing 17% shorter generation time [22] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yeast | Facultative Anaerobe | Robust industrial fermentation, GRAS status, eukaryotic protein processing [17] [20] | Engineered for production of fatty acid-derived hydrocarbons and opioids [17] [23] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Yeast | Aerobic | Oleaginous, high lipid accumulation, organic acid production [17] [23] | Metabolic engineering for high-level production of lipids and oleochemicals [17] |

| Synechocystis spp. | Cyanobacterium | Photosynthetic | CO2 fixation, biofuel and chemical production using light and CO2 [17] [18] | Engineered for production of aromatic amino acids and phenylpropanoids [17] |

Core Engineering Methodologies and Protocols

The engineering of a microbial chassis involves a multi-faceted approach, from genome-wide modifications to precise pathway regulation.

Workflow for Developing an Engineered Microbial Chassis

The following diagram outlines the generalized Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle for chassis development, integrating various engineering methodologies.

First-Generation Engineering: Modifying Natural Microbes

This approach involves targeted genetic interventions in natural microorganisms to optimize them for production.

Protocol 1: Enhancing Precursor Supply via Gene Deletion and Overexpression (e.g., for Fatty Acid Production in S. cerevisiae)

- Objective: To increase the cytosolic acetyl-CoA pool, a key precursor for fatty acid synthesis.

- Materials:

- S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., BY4741)

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid system for yeast

- Donor DNA for gene deletion and integration

- SC-URA dropout medium

- Analytical equipment (GC-MS for fatty acid analysis)

- Methodology:

- Deletion of Competing Pathways: Use a CRISPR-Cas9 system to knock out the gene encoding pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC), redirecting pyruvate flux away from ethanol formation [20].

- Expression of Heterologous Enzymes: Assemble a gene expression cassette containing the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) bypass genes—cytosolic pyruvate dehydrogenase, phosphopantetheinyl transferase, and acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS). Codon-optimize these genes for S. cerevisiae.

- Genetic Transformation: Co-transform the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid (for PDC deletion) and the donor DNA cassette (for PDH bypass integration) into the yeast strain using a standard lithium acetate protocol.

- Selection and Screening: Select transformants on SC-URA plates. Verify gene deletion and integration via colony PCR and sequencing.

- Evaluation: Cultivate engineered strains in shake flasks. Quantify intracellular acetyl-CoA levels and analyze fatty acid production titers using GC-MS.

Advanced Engineering: Synthetic Biology Approaches

Synthetic biology enables more radical rewiring of cellular machinery, moving beyond modifications of natural hosts.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Synthetic C1 Assimilation Pathway in a Polytrophic Host (e.g., P. putida)

- Objective: Engineer a non-model, robust host like P. putida to assimilate methanol, a sustainable C1 feedstock.

- Materials:

- P. putida KT2440

- Broad-host-range plasmid or chromosomal integration system

- Genes for the methanol dehydrogenase (MDH) and the RuMP/ribulose monophosphate cycle enzymes (Hxl, Hxl, etc.)

- Methanol-minimal medium

- Native, methanol-inducible promoters from a methylotroph [19]

- Methodology:

- Pathway Selection and Design: Choose a synthetic assimilation pathway, such as the RuMP cycle, known for its high energy efficiency and theoretical yield [19].

- Vector Construction: Synthesize and assemble the MDH and RuMP cycle genes into a broad-host-range vector. Use native, methanol-inducible promoters to regulate expression and minimize metabolic burden.

- Strain Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into P. putida via electroporation or conjugation.

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Grow the engineered strain in serial passages with increasing concentrations of methanol as the sole carbon source to select for mutants with improved growth and methanol utilization.

- Systems-Level Analysis: Perform transcriptomics and metabolomics on the evolved strain to understand the adaptive changes and identify potential bottlenecks for further engineering.

Genome Reduction for Chassis Streamlining

Creating minimal genomes reduces cellular complexity and diverts resources toward production.

Protocol 3: Computational Prediction of Essential Genes for Genome Reduction

- Objective: Identify a minimal set of essential genes in Lactococcus lactis to create a streamlined chassis for therapeutic protein production.

- Materials:

- Annotated genome sequence of L. lactis (e.g., from NCBI)

- Genome-scale metabolic (GSM) model (if available, e.g., iML1515)

- Computational tools: DEG (Database of Essential Genes), essentiality predictors (e.g., TraDIS, Tn-seq analysis tools)

- Methodology:

- In Silico Essentiality Prediction: Use a combination of homology-based search against the DEG and computational algorithms to predict genes essential for growth in a defined medium.

- Metabolic Model Simulation: Employ the GSM model with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to simulate growth and identify metabolic genes that are indispensable under various nutrient conditions [22].

- Design Deletion Sets: Compile a list of non-essential genes, prioritizing large genomic regions like prophages and genomic islands for deletion. Design overlapping PCR primers for sequential deletion rounds.

- Experimental Validation: Systematically delete predicted non-essential regions using CRISPR-based genome editing. Measure the impact on growth rate, generation time, and transformation efficiency.

- Functional Testing: Test the genome-reduced strain for its capacity to express heterologous proteins, comparing productivity to the wild-type strain [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Successful chassis engineering relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Microbial Chassis Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12a (Cpfl), base editors | Enables precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and point mutations [20] [22]. |

| DNA Assembly & Synthesis | Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly, oligonucleotide pools, synthetic gene fragments | Facilitates construction of complex genetic circuits and heterologous pathways [17] [24]. |

| Specialized Vectors | Broad-host-range plasmids (e.g., RSF1010 origin), chromosomal integration vectors (e.g., with Tn7 transposon), inducible expression systems | Allows for stable maintenance and controlled expression of heterologous genes in diverse hosts [19] [18]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Genome annotation pipelines (RAST, Prokka), metabolic modeling software (COBRApy), essentiality prediction tools | Supports in silico design and analysis of engineered chassis [22]. |

| Analytical & Omics Tools | GC-MS / LC-MS, HPLC, RNA-Seq, proteomics platforms | Critical for quantifying products (titers, yields) and understanding host responses at a systems level [20] [19]. |

Metabolic Pathways and Engineering Strategies

A critical application of engineered chassis is the production of fatty acid-derived biofuels. The following diagram illustrates the integrated metabolic engineering strategies applied in yeast.

Supporting Protocol for Fatty Acid-Derived Hydrocarbon Production in Yeast:

- Host: Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Yarrowia lipolytica.

- Engineering Steps:

- Precursor Augmentation (Node E1): Overexpress acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) and ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) to enhance cytosolic acetyl-CoA supply [20] [23].

- Cofactor Engineering (Node E2): Overexpress enzymes in the pentose phosphate pathway (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) to increase NADPH regeneration [20].

- Pathway Engineering (Node E4): Introduce heterologous genes for a specific hydrocarbon pathway, such as acyl-ACP reductase (AAR) and aldehyde deformylating oxygenase (ADO), to convert fatty acids to alka(e)nes [23].

- Remove Competition (Node E3): Knock out genes involved in storage lipid formation (e.g., DGAT1) to channel fatty acids toward the hydrocarbon pathway.

- Tolerance Engineering (Node E5): Employ adaptive laboratory evolution or engineer membrane composition (e.g., by overexpressing elongase genes) to improve tolerance to toxic hydrocarbon products [20].

The strategic engineering of microbial chassis, encompassing both classical genetic modifications and cutting-edge synthetic biology, provides a powerful platform for renewable resource utilization. The continued diversification of chassis organisms, coupled with advanced tools in genome editing, systems biology, and computational modeling, is pivotal for overcoming existing challenges in yield, toxicity, and substrate scope. By systematically applying the protocols and strategies outlined in this article, researchers can design next-generation platform biocatalysts tailored for efficient and sustainable bioprocesses, ultimately advancing the goals of a circular bioeconomy.

Expanding the Substrate and Product Spectra for Bio-based Production

The transition from a fossil-based economy to a sustainable bio-based economy is a central pillar of global efforts to combat climate change and ensure energy security [25] [26]. Metabolic engineering serves as a key enabling technology in this transition, allowing for the rewiring of microbial metabolism to convert renewable resources into valuable chemicals and fuels [27]. A significant challenge in this field is the inherent recalcitrance of non-food biomass and the limited natural capabilities of industrial microbial workhorses to utilize diverse carbon streams and produce non-native compounds [25] [28]. This application note details advanced protocols and strategies for expanding both the substrate spectrum to include cost-effective lignocellulosic sugars and the product spectrum to encompass high-value, high-density biofuels and chemicals, framed within the context of a broader thesis on renewable resource utilization.

Expanding the spectra for bio-based production involves engineering at multiple hierarchical levels, from individual enzymes to the entire cellular network [27]. The overarching goal is to create efficient microbial cell factories that can convert low-cost, renewable feedstocks into a wide array of products with maximal yield, titer, and productivity [28].

Core Challenges:

- Substrate Spectrum: Lignocellulosic biomass, the most abundant renewable carbon source, is difficult to degrade and contains a mixture of hexose and pentose sugars (e.g., glucose, xylose, arabinose) [25] [26]. Furthermore, pretreatment processes generate microbial inhibitors like furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) [29].

- Product Spectrum: Many industrially relevant chemicals, such as long-chain alcohols and bio-hydrocarbons, are not naturally produced by industrial microbes at high yields [29].

Engineering Solutions: The field has progressed through three waves of innovation: rational pathway engineering, systems biology-guided optimization, and synthetic biology-enabled construction of novel pathways [27]. The protocols below focus on the application of these advanced strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Engineering Sucrose Catabolism in Non-Native Bacterial Hosts

Background: Sucrose, a major component of low-cost molasses, is not metabolized by many industrially relevant bacteria like Pseudomonas putida [30]. This protocol describes the introduction of a sucrose-splitting pathway.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli W (DSM 1116) as gene donor; P. putida KT2440 or Cupriavidus necator as recipient chassis.

- Vectors: pSEVA plasmids or pBAMD1-2 as backbones for constructing mini-transposons (e.g., pSST) [30].

- Key Genes:

cscA(encoding sucrose invertase),cscB(encoding sucrose permease) from E. coli W. - Media: LB for routine cultivation; M9 minimal medium with 3 g/L sucrose for growth assays.

Methodology:

- Gene Cloning: Amplify

cscAandcscBfrom E. coli W genomic DNA. Clone them into the pSEVA or pBAMD1-2 backbone to create mini-Tn5 transposons, generating two constructs: one carrying onlycscAand another carrying bothcscAandcscB. - Conjugation: Transfer the constructed plasmids into the recipient P. putida or C. necator via conjugation using the helper strain E. coli HB101 (pRK600). Select transconjugants on M9 citrate medium with appropriate antibiotics.

- Growth Phenotype Validation:

- Inoculate engineered strains into M9 medium with sucrose as the sole carbon source.

- Cultivate in 500 mL shake flasks with 50 mL medium at 30°C and 220 rpm.

- Monitor optical density (OD600) every 20 minutes over 72 hours using a microplate reader to determine growth rates.

- Analysis: Compare the growth rates of strains carrying

cscAalone versuscscAB. In P. putida,cscAalone is often sufficient for sucrose growth due to extracellular sucrose splitting, while in C. necator,cscBmay additionally facilitate glucose uptake [30].

Table 1: Growth Performance of Engineered Strains on Sucrose

| Host Strain | Genetic Construct | Maximum OD600 | Specific Growth Rate (μ, h⁻¹) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. putida KT2440 | None (Wild-type) | < 0.2 | ~0 | No growth on sucrose |

| P. putida KT2440 | pSST-cscA |

~1.8 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | Functional extracellular invertase |

| P. putida KT2440 | pSST-cscAB |

~1.8 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | Permease has minimal additional effect |

| C. necator | pSST-cscAB |

~2.1 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | Permease may function as glucose transporter |

Protocol 2: Optimizing Artificial Cellulosomes for Enhanced Biomass Degradation

Background: Efficient hydrolysis of cellulose requires synergistic action of multiple enzymes. Some microbes produce enzyme complexes called cellulosomes. This protocol outlines the creation of a synthetic microbial consortium for consolidated bioprocessing of cellulose.

Materials:

- Strains: Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains engineered to display specific cellulolytic enzymes.

- Enzymes: Endoglucanase II (EG II), Cellobiohydrolase I (CBH I), β-glucosidase I (BG I) from Penicillium oxalicum [31].

- Biomass: Pre-treated cellulosic materials (e.g., acid-pretreated corn stover, ammonium sulfite-pretreated wheat straw).

Methodology:

- Consortium Design: Engineer a consortium of yeast strains where individual strains display mini scaffoldins (e.g., mini CipA) or different cellulases (EG II, CBH I, BG I) on their cell surface [29] [31].

- Enzyme Cocktail Optimization (for in vitro use):

- Use a mixture design method to determine the optimal ratio of the core cellulase components (EG II, CBH I, BG I).

- Perform enzymatic hydrolysis assays on different pre-treated cellulosic materials at high solids loading (e.g., 20% w/w).

- Measure the release of reducing sugars (e.g., glucose) over time to calculate hydrolysis efficiency.

- Consolidated Bioprocessing (CBP) Fermentation:

- Cultivate the engineered yeast consortium directly with cellulose substrate.

- Monitor the production of the target biofuel (e.g., ethanol) directly, bypassing the need for external enzyme addition [29].

Table 2: Optimal Cellulase Cocktail Compositions for Different Substrates

| Pretreatment Method | Substrate | Optimal Enzyme Ratio (EG II:CBH I:BG I) | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Pretreatment | Corn Stover | 25 : 60 : 15 | High CBH I proportion critical, likely due to strong adsorption on lignin |

| Ammonium Sulfite | Wheat Straw | 40 : 45 : 15 | Higher EG II requirement for efficient hydrolysis |

| Alkaline Pretreatment | Sugarcane Bagasse | 30 : 50 : 20 | Balanced composition for effective degradation |

Protocol 3: Engineering Inhibitor Tolerance inE. coli

Background: Furfural is a potent inhibitor generated during lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment. This protocol details genetic modifications to enhance microbial tolerance.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli production chassis (e.g., DH5α or production-oriented derivatives).

- Genetic Tools: CRISPR/Cas9 for precise gene deletion and integration [29].

- Media: M9 or rich medium supplemented with furfural (≥ 1.5 g/L) for tolerance assays.

Methodology:

- Gene Deletion: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to delete the

yqhDgene, which encodes an NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase that depletes NADPH pools upon furfural detoxification [29]. - Gene Overexpression:

- Overexpress the

pntABgenes, encoding transhydrogenase, to enable NADH to NADPH conversion and restore cofactor balance. - Overexpress oxidoreductases like

fucO(lactaldehyde reductase) which can reduce furfural using NADH.

- Overexpress the

- Tolerance Assay:

- Grow engineered and control strains in media containing a defined concentration of furfural.

- Measure the growth lag phase and the specific growth rate. Successful engineering significantly reduces the lag phase and increases the growth rate under inhibitor stress [29].

- Cofactor Analysis: Monitor intracellular NADPH/NADP⁺ ratios to confirm the restoration of redox balance.

Protocol 4: Rewiring Metabolism for Advanced Biofuel Production

Background: This protocol focuses on expanding the product spectrum beyond ethanol to advanced biofuels like n-butanol and isoprenoids in model hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli or S. cerevisiae.

- Pathway Components: Heterologous genes for n-butanol (e.g.,

thl,hbd,crt,bcd,adhE2from Clostridium) or isoprenoid (e.g., mevalonate pathway genes, terpene synthases) biosynthesis. - Analytical Tools: GC-MS for fuel molecule detection and quantification.

Methodology:

- Heterologous Pathway Expression: Assemble and express the complete biosynthetic pathway for the target advanced biofuel in the chosen host.

- Host Engineering:

- Cofactor Engineering: Modify cofactor specificity of key enzymes to match the cellular redox state (e.g., favor NADH over NADPH) [27] [29].

- Competitor Pathway Knockout: Use multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE) or CRISPR/Cas9 to delete genes involved in competing metabolic pathways (e.g., lactate, acetate formation) [29].

- Transporter Engineering: Overexpress cellobiose transporters to enhance sugar uptake from lignocellulosic hydrolysates [29].

- Pathway Optimization: Employ metabolic flux analysis to identify rate-limiting steps. Use synthetic biology tools to fine-tune the expression of pathway genes via promoter and RBS engineering.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Pathways for Pentose Sugar Assimilation

The diagram below illustrates the primary natural pathways used by microorganisms to assimilate pentose sugars from lignocellulosic biomass, a key step in expanding the substrate spectrum [28].

Hierarchical Metabolic Engineering Workflow

This workflow outlines the systematic, multi-level engineering approach for developing robust microbial cell factories [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pSEVA / pBAMD Vectors | Modular, broad-host-range plasmids for gene expression and transposon delivery. | Introducing sucrose catabolism genes (cscA, cscB) into non-native hosts like P. putida [30]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed genome editing. | Deleting the yqhD gene in E. coli to increase furfural tolerance [29]. |

| Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) | Allows for simultaneous, automated mutation of multiple genomic sites. | Optimizing production pathways by fine-tuning expression levels of multiple genes in a single experiment [29]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico models predicting organism metabolism; used to identify engineering targets. | Predicting gene knockout strategies for enhanced lycopene or succinic acid production [27]. |

| Cellulase Enzyme Cocktails | Mixtures of endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases for biomass hydrolysis. | Optimizing ratios of EG II, CBH I, and BG I for efficient saccharification of pre-treated feedstocks [31]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) | "Green solvents" for efficient pretreatment and deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass [28]. | Generating fermentable sugars from biomass with reduced inhibitor formation. |

Methodological Frameworks and Practical Applications in Strain Design and Engineering

In the pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing, metabolic engineering aims to redesign microbial metabolism for efficient production of chemicals from renewable resources. A cornerstone strategy in this field is growth-coupled production, where the synthesis of a target compound is genetically linked to the host organism's growth and survival [32]. This strategy leverages the power of adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE), as evolved mutants with higher growth rates inherently possess higher product synthesis rates [33] [32]. Implementing growth-coupled designs, however, is non-trivial. Computational strain design algorithms are essential for identifying the complex genetic interventions required to enforce this coupling. Two pivotal approaches for this task are OptKnock and Minimal Cut Sets (MCSs), which use constraint-based metabolic modeling to predict gene knockout strategies that force the cell to produce valuable chemicals as a byproduct of its growth [34] [35].

This note details the principles, applications, and protocols for these algorithms, providing a practical guide for researchers and scientists engaged in developing microbial cell factories.

Algorithmic Foundations and Key Concepts

Theoretical Principles of Growth-Coupling

Growth-coupled production can be classified based on the strength of the coupling between biomass formation and product synthesis, which is visualized through a production envelope [35]. The classification is as follows:

- Weak Growth-Coupling (wGC): Product synthesis is only required at elevated growth rates, a behavior often observed naturally in overflow metabolism.

- Holistic Growth-Coupling (hGC): A non-zero minimum production rate is maintained across all growth rates greater than zero.

- Strong Growth-Coupling (sGC): Product synthesis is mandatory for all metabolic states, including zero growth, making the product a necessary byproduct of substrate consumption [35].

The primary metabolic principles used to enforce these couplings are:

- Creating an Essential Carbon Drain: Engineering the network such that a significant portion of carbon flux must be diverted to the product to enable biomass synthesis [35].

- Inducing Cofactor Imbalance: Designing the network so that cofactors (e.g., redox equivalents) can only be balanced through reactions involved in the synthesis of the target product [35].

OptKnock

OptKnock is a bilevel optimization framework that identifies gene knockouts to maximize the production of a target chemical while maintaining a predetermined level of growth [34] [35]. The algorithm operates under the assumption that the cell maximizes its growth rate (inner problem), while the engineer selects knockouts that maximize product flux (outer problem). This bi-level programming problem can be reformulated into a Mixed Integer Linear Program (MILP), making it solvable with standard optimization software [34]. A key variant, RobustKnock, maximizes the minimally guaranteed production rate at maximum growth, leading to more robust designs [35]. Further adaptations, like gcOpt, maximize the minimum production at a fixed, medium growth rate to prioritize designs with higher coupling strength across a wider range of growth states [35].

Minimal Cut Sets (MCSs)

A Minimal Cut Set (MCS) is defined as a minimal set of reactions whose removal from the metabolic network blocks a defined target function, such as growth without product formation [36] [34]. The power of the MCS approach lies in its duality with Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs). An MCS is a minimal hitting set for all EFMs that support an undesired network function [36] [34]. For growth-coupled production, MCSs are computed to disable all EFMs that allow for growth without simultaneously producing the desired product [35]. Initially limited by the need to enumerate all EFMs, advancements like the MCSEnumerator algorithm now allow for the calculation of MCSs in genome-scale models without full EFM enumeration [35]. The framework has been generalized to Constrained MCSs (cMCSs), which allow the definition of both desired (e.g., a minimum growth rate) and undesired (e.g., zero product synthesis) functionalities, providing immense flexibility in strain design [34].

Table 1: Comparison of OptKnock and Minimal Cut Sets (MCSs) for Growth-Coupled Strain Design.

| Feature | OptKnock | Minimal Cut Sets (MCSs) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Bilevel optimization (cell vs. engineer) | Minimal intervention sets to block target network functions |

| Mathematical Basis | Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Dual network analysis / Elementary Mode (EM) duality |

| Primary Output | One (often optimal) knockout strategy | Enumerates all possible minimal intervention strategies |

| Handling Multiple Solutions | Returns a single solution per run; requires iterative runs for alternatives | Systematically enumerates all minimal strategies up to a defined size |

| Consideration of Constraints | Can incorporate constraints via the model's linear inequalities | Extended to Constrained MCSs (cMCSs) to define desired/undesired functions |

| Computational Scalability | Applicable to genome-scale models | Historically limited by EM enumeration; now feasible for large models with modern tools |

Computational Protocols and Workflows

A Generic Workflow for Computational Strain Design

The following workflow, illustrated in the diagram below, outlines the key steps for applying OptKnock and MCSs.

Diagram Title: Computational Strain Design Workflow

Protocol 1: Implementing an OptKnock Simulation

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for running an OptKnock simulation using a COBRA-compatible toolbox in Python or MATLAB.

Objective: Identify gene knockout strategies for growth-coupled production of a target metabolite. Input Requirements: A genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., E. coli iJO1366), a defined growth medium, and a target exchange reaction.

- Model Preparation: Load the model and set constraints to reflect the desired cultivation conditions (e.g., anaerobic growth: oxygen uptake = 0; glucose uptake = 10 mmol/gDCW/h).

- Define the Production Objective: Specify the exchange reaction of the target metabolite (e.g., 'EXsucce' for succinate) as the objective to maximize in the outer problem.

- Algorithm Configuration: Set the OptKnock parameters:

maxKnocks: The maximum number of allowed gene or reaction knockouts (e.g., 5).targetBound: The minimum desired production rate (can be set to zero initially).biomassRxn: The identifier of the biomass reaction (e.g., 'BIOMASSEciJO1366core59p81M').

- Execution: Run the OptKnock algorithm. This solves the bilevel optimization problem, typically reformulated as an MILP.

- Output Analysis: The algorithm returns a set of suggested reaction knockouts. Validate the design by simulating the mutant model with FBA and performing Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to examine the range of possible production rates at maximum growth.

Protocol 2: Calculating Minimal Cut Sets for Strain Design

This protocol outlines the process for calculating MCSs using tools like aspefm or MCSEnumerator.

Objective: Enumerate all minimal reaction sets that couple growth to target metabolite production. Input Requirements: A metabolic model (core or genome-scale), defined constraints, and target/desired functions.

- Model Compression: Pre-process the model to remove blocked reactions and compress the network, which drastically reduces computational complexity [37].

- Formulate the cMCS Problem: Define the intervention problem using sets of target and desired modes or directly as network functionalities:

- Algorithm Configuration: Set parameters such as the maximum MCS size (number of reactions in the cut set) and the numerical tolerance.

- Computation: Execute the MCS enumeration algorithm. Modern tools like

aspefmuse logic programming to efficiently find MCSs, even in large networks [37]. - Post-processing: The output is a list of MCSs. Filter these sets to eliminate strategies that are biologically infeasible or difficult to implement (e.g., knocking out a substrate uptake reaction).

Protocol 3: Evaluating and Ranking Strain Designs

Not all in silico designs perform equally in vivo. This protocol describes a robust workflow for filtering and ranking designs, considering both metabolic and proteomic constraints.

- Calculate Production Envelopes: For each design, compute the production envelope to visualize the relationship between growth rate and the minimum/maximum production rate. This classifies the coupling strength (wGC, hGC, sGC) [35].

- Assess Robustness with ME-models: Test the designs using a Metabolism and Expression (ME) model, which incorporates enzyme catalytic rates (

k_effvalues) and biosynthetic costs. A design is considered robust if growth-coupled production is maintained across multiple sampled sets of kinetic parameters [33]. - Remove Redundant Knockouts: Identify and remove non-essential knockouts from a design if their removal does not significantly decrease the carbon yield, substrate-specific productivity, or coupling strength [33].

- Ranking: Rank designs based on multiple criteria, such as:

- Minimally guaranteed product yield at a fixed growth rate.

- Predicted maximum theoretical yield.

- Number of required genetic modifications.

- Robustness score from ME-model analysis.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Resources for Computational Strain Design.

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Stoichiometric representations of an organism's metabolism. Serve as the in silico testbed for simulations. | E. coli iJO1366; S. aureus iYS854; P. aeruginosa iPae1146 [33] [37]. |

| Models of Metabolism & Expression (ME-models) | GEMs extended with constraints on gene expression and enzyme capacity. Provide more realistic predictions. | iOL1650-ME model for E. coli; used to account for protein burden and validate design robustness [33]. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction & Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | A software suite (MATLAB/Python) providing essential functions for constraint-based modeling. | Running FBA, OptKnock, and other strain design algorithms [38]. |

| MCS Enumeration Software (aspefm, MCSEnumerator) | Specialized tools for calculating Minimal Cut Sets from metabolic networks. | Identifying all possible genetic intervention strategies for complex engineering goals [37] [35]. |

| Chemically Defined Media (e.g., CSP Medium) | A medium with a known exact chemical composition. Crucial for constraining the model's extracellular environment. | In silico simulation of chronic wound conditions for a S. aureus-P. aeruginosa consortium model [37]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The applications of OptKnock and MCSs extend beyond engineering single microbes for chemical production.

- Therapeutic Targeting: MCSs can identify synthetic lethal reaction sets in pathogenic bacteria or cancer cells. For example, MCSs were applied to a consortium model of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa to find drug targets that disrupt the synergistic interactions making these co-infections resilient [37].

- Optimization of Synthetic Modules: Growth-coupling is a powerful tool for selecting and improving the performance of synthetic metabolic pathways. By designing selection strains where a heterologous module is essential for producing a biomass precursor, growth rate becomes a direct readout for module efficiency, accelerating the DBTL cycle [32].

- Integration with Multi-Omics Data: Future strain design will increasingly integrate diverse datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to create context-specific models. Machine learning and methods that incorporate enzyme kinetic constraints (e.g., GECKO) will further enhance the prediction accuracy of computational designs, closing the gap between in silico predictions and in vivo performance [38].

The field of metabolic engineering is dedicated to rewiring cellular metabolism to transform microbes into efficient factories for producing chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources [27]. The evolution of this discipline has been propelled by advances in genetic engineering tools, progressing from early random mutagenesis to highly precise, rational genome engineering [39]. Among these, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR/Cas9) and Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) represent two of the most powerful technologies enabling systematic and precise genomic alterations. These tools facilitate the optimization of complex metabolic pathways, allowing researchers to overcome cellular limitations and significantly enhance the production of valuable compounds in model organisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [29]. Their application is crucial for developing sustainable bioprocesses that utilize lignocellulosic biomass and other renewable feedstocks, aligning with the global transition towards a circular bioeconomy [40].

CRISPR/Cas9: A Programmable Genome Editing Platform

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering by providing unprecedented precision and programmability. Originally identified as a bacterial adaptive immune system, it has been repurposed as a versatile molecular tool for targeted DNA cleavage. The system's core components are the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA), which directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus complementary to the gRNA sequence [41]. The resulting double-strand break (DSB) is then repaired by the host cell's machinery, enabling gene knockouts, insertions, or precise edits through homology-directed repair (HDR) [39].

The applications of CRISPR/Cas9 in metabolic engineering are extensive. Its high efficiency, with precision levels ranging from 50% to 90% compared to the 10–40% obtained with earlier techniques, has enabled remarkable improvements in bacterial productivity [39]. The toolset has expanded beyond simple gene cutting to include transcriptional modulators (CRISPRa/i), epigenome editors, base/prime editors, and biosensor-integrated logic gates, forming a versatile synthetic biology "Swiss Army Knife" for microalgal and bacterial engineering [41]. This allows for tunable gene expression, stable epigenetic reprogramming, DSB-free nucleotide-level precision editing, and coordinated rewiring of complex metabolic networks [41].

MAGE: Multiplexed Genome-Scale Engineering

MAGE represents a complementary approach for large-scale genomic optimization. This technology utilizes synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides (ss-oligos) and bacteriophage single-strand annealing proteins (SSAPs), such as Redβ from the λ phage, to introduce targeted mutations across multiple genomic locations simultaneously [42] [39]. Unlike CRISPR/Cas9, MAGE does not rely on creating double-strand breaks, instead facilitating direct recombination of oligonucleotides into the genome during DNA replication [42].

The principal advantage of MAGE is its ability to perform multiplexed editing, enabling the rapid exploration of combinatorial genetic space. This is particularly valuable for optimizing metabolic pathways where multiple gene adjustments are required to balance flux and maximize yield [29]. Early multiplex strategies using ss-oligos, such as MAGE, have been extended by techniques like CoS-MAGE, pORTMAGE, and TRMR (Traceable RMR) [42]. Furthermore, the development of dsDNA Recombineering-assisted Multiple Genome Engineering (dReaMGE) and its enhanced version, ReaL-MGE, has expanded multiplex capabilities to include kilobase-scale DNA manipulations, allowing for simultaneous insertions and deletions of large genetic constructs [42].

Quantitative Comparison of Advanced Genetic Tools

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Key Genome Engineering Tools

| Tool | Editing Precision | Key Feature | Typical Editing Efficiency | Primary Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Nucleotide-level | RNA-programmed DNA cleavage | 50% - 90% [39] | Gene knockouts, knock-ins, transcriptional regulation [41] |

| MAGE | Oligo-mediated | Multiplexed automated editing | Varies with site [42] | Combinatorial library generation, pathway optimization [42] |

| ReaL-MGE | Kilobase-scale | dsDNA multiplex integration | Demonstrated 22 kb-scale integrations [42] | Large pathway insertion, genome reduction, complex network engineering [43] [42] |

| Base/Prime Editors | Single-nucleotide | DSB-free editing | Varies by system [41] | Point mutations, precise amino acid substitutions [41] |

Integrated Tools and Reagents for Genome Engineering

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Genome Editing

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Protein Variants | SpCas9, FnCas12a, CasMINI [41] | Catalyzes DNA cleavage; different variants offer varying PAM requirements and sizes for broad host applicability. |

| Recombineering Proteins | Redγβα (from λ phage), RecET (from Rac phage) [43] [42] | SSAPs that mediate homologous recombination with ss-oligos or dsDNA substrates in recombineering and MAGE. |

| Delivery Vectors | pBBR1-PRha-Redγβα-PBAD-Cas9-Km [42] | Broad-host-range plasmid for inducible expression of recombineering and CRISPR machinery. |

| Linear Editing Substrates | PCR fragments with phosphorothioate ends [42] | Protects linear DNA from exonuclease degradation, enhancing recombination efficiency in ReaL-MGE. |

| Inducible Promoters | pBAD (arabinose-inducible), pRHA (rhamnose-inducible) [43] [42] | Tightly regulates expression of cytotoxic proteins like Cas9 and recombinases to minimize cell stress. |

| Biosensor Plasmids | RK2-J233-GFP-genta-FapR-amp [43] | Reports on intracellular metabolite levels (e.g., malonyl-CoA) via GFP fluorescence, enabling high-throughput screening. |

Application Notes in Metabolic Engineering

Enhancing Malonyl-CoA Biosynthesis Using ReaL-MGE

Malonyl-CoA is a central precursor for polyketide synthases (PKS) and fatty acid synthases (FAS), making its elevated production a key objective in metabolic engineering. The ReaL-MGE platform was successfully applied to engineer malonyl-CoA metabolism in three bacterial hosts: E. coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Schlegelella brevitalea [42].

In a single engineering round with E. coli BL21, ReaL-MGE was used to create a strain (E. coli* BL21.C33) with 14 targeted genomic modifications. These edits included a multi-dimensional strategy involving malonyl-CoA metabolic network engineering and genome reduction [42]. The resulting strain exhibited a 26-fold increase in intracellular malonyl-CoA levels. This elevated precursor pool directly translated to an 11.4-fold improvement in the yield of alonsone, a heterologously expressed type III PKS compound [42].

This case demonstrates the power of multiplex dsDNA editing for complex trait engineering, simultaneously modulating multiple regulatory nodes and pathway genes that would be impractical to target sequentially with older methods.

Production of Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts

CRISPR/Cas9 and MAGE are instrumental in developing microbial cell factories for next-generation biofuels that surpass the limitations of first-generation bioethanol. These tools engineer pathways for biofuels like n-butanol, iso-butanol, isoprenoids, and fatty-acid-derived biofuels, which have higher energy density and are more compatible with existing infrastructure [29].

A prominent application is the engineering of E. coli and S. cerevisiae to utilize lignocellulosic biomass, a renewable and non-competitive feedstock. Key strategies include:

- Microbial Engineering for Lignocellulose Utilization: Engineering microbes to express cellulases (endoglucanases, exoglucanases, β-glucosidases) and hemicellulases (xylanases, β-xylosidases) to hydrolyze biomass into fermentable sugars [29].

- Tolerance Engineering: Using CRISPR to modify microbial responses to inhibitors (e.g., furfural, acetic acid) generated during lignocellulose pre-treatment. For example, in E. coli, engineering the expression of the pntAB transhydrogenase gene and knocking out the yqhD oxidoreductase gene can mitigate NADPH depletion caused by furfural, enhancing growth and fermentation [29].

- Pathway Optimization: Rewiring central metabolism to redirect carbon flux toward target biofuels. CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise knockouts of competing pathways and integration of heterologous biosynthetic genes, while MAGE allows for the fine-tuning of enzyme expression levels across an entire pathway [29].

Experimental Protocols

Recombineering-assisted Linear CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Multiplex Genome Editing (ReaL-MGE)

ReaL-MGE synergizes the RNA-guided programmability of CRISPR/Cas9 with the 5’-3’ exonuclease and single-strand DNA annealing protein activities of phage recombinases. This protocol enables precise, simultaneous kilobase-scale DNA manipulation at multiple genomic loci in bacteria, mitigating off-target effects and circumventing the complexities of assembling multiple gRNAs on circular vectors [43] [42]. The entire procedure requires approximately 9 days.

Day 1: Plasmid Transformation

- Steps 1-10 (3 hours): Construction of Expression and Biosensor Plasmids. Clone the necessary components (e.g., inducible Cas9, phage recombinases) into appropriate broad-host-range vectors (e.g., pBBR1 origin). Similarly, prepare the metabolite biosensor plasmid (e.g., malonyl-CoA sensing FapR-GFP system) [43].

- Steps 11-19 (3 hours): Electroporation. Introduce the expression and biosensor plasmids into the target bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli BL21, P. putida KT2440) via electroporation [43].

- Steps 20-22 (4 hours): Transformation Verification. Culture transformed cells on selective media containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin for the pBBR1 plasmid) to verify successful transformation [43].

Day 2: Seamless Modifications by ReaL-MGE

- Steps 23-29 (12 hours):

- Induction of Recombinases: Grow the transformed strain and induce the expression of phage recombinases (e.g., Redγβα) with L-rhamnose [43] [42].

- Electroporation of dsDNA Donors: Co-electroporation of multiple linear, asymmetrically phosphorothioate-protected, PCR-generated dsDNA HR substrates (kibase-scale) into the induced cells. These substrates contain homology arms for targeted integration [42].

- Induction of Cas9: After the first electroporation, induce Cas9 expression with L-arabinose during the recovery period to promote counterselection [42].

- Second Electroporation with gRNA Fragments: Perform a second electroporation with a mixture of 5’-end phosphorothioate-protected, linear gRNA-expressing PCR fragments (e.g., total input of 200 ng). These linear gRNAs direct Cas9 to cleave the wild-type, unedited genomes, enriching for successfully edited cells [42].

Day 3-9: Screening and Validation

- Steps 30-40 (Day 3, 5 hours): FACS Sorting. For metabolite engineering, use the biosensor plasmid to screen for high-producing clones. Cells with elevated target metabolite (e.g., malonyl-CoA) will exhibit higher GFP fluorescence, which can be sorted using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [43].

- Steps 41-48 (Day 3, 2 hours): Analytical Quantification. Validate the production titers of the target compound (e.g., polyketide) using analytical methods like HPLC or MS. Quantify intracellular malonyl-CoA levels enzymatically or via LC-MS [43].

- Remaining Days: Continue with colony PCR, DNA sequencing, and fermentations to fully characterize the engineered strains and confirm the absence of off-target mutations [42].

Diagram 1: ReaL-MGE workflow for multiplex bacterial genome editing.

CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Pathway Engineering in Microalgae

Microalgae are promising platforms for biofuel production due to their ability to use sunlight and CO₂. This protocol outlines the use of advanced CRISPR tools (beyond cutting) for metabolic engineering in microalgae.

1. Tool Selection and Design:

- Select CRISPR System: Choose a Cas protein variant suited to the microalgal species. High-fidelity SpCas9 is common, but smaller variants (Cas12a, CasMINI) or those with different PAM requirements may be needed [41].

- Design gRNAs: Design gRNAs with high on-target efficiency and low off-target potential for the genes of interest (e.g., genes in lipid biosynthesis).

- Choose Effector Domain: For CRISPRa/i, design sgRNAs fused to transcriptional activator (e.g., VP64) or repressor (e.g., KRAB) domains. For base editing, select the appropriate base editor (CBE or ABE) [41].

2. Construct Assembly and Delivery:

- Assembly: Clone the selected Cas variant, gRNA(s), and any effector domains into a microalgal expression vector with species-specific promoters and selectable markers.

- Delivery: Introduce the constructs into microalgae using optimized methods. Electroporation is widely used, though particle bombardment (biolistics) and PEG-mediated transformation are also common. Engineered viruses or Agrobacterium-based systems represent advanced delivery options [41].

3. Screening and Phenotypic Validation:

- Regeneration and Selection: Regenerate whole plants or cells under antibiotic selection to obtain stable transformants. A key advantage of editors like base editors is the ability to generate transgene-free edited plants by delivering pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [41] [44].

- Genotypic Analysis: Confirm edits via DNA sequencing of target loci to verify intended mutations and check for off-target effects.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Assess the engineered microalgae for target traits, such as:

- Lipid content (e.g., for biodiesel) via Nile Red staining or GC-MS.

- Growth rate and stress resilience under scale-up conditions.

- Titer of specific high-value compounds (e.g., carotenoids, PUFAs) [41].

Diagram 2: CRISPR pathway engineering workflow for microalgae.