Metabolic Engineering for Advanced Biofuels: Pathway Optimization, Novel Hosts, and Industrial Scale-Up

This article synthesizes current advancements and methodologies in applying metabolic engineering to biofuel production, tailored for researchers and scientists in biotechnology and drug development.

Metabolic Engineering for Advanced Biofuels: Pathway Optimization, Novel Hosts, and Industrial Scale-Up

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advancements and methodologies in applying metabolic engineering to biofuel production, tailored for researchers and scientists in biotechnology and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of redirecting microbial metabolism for biofuel synthesis, detailing cutting-edge tools like CRISPR/Cas9 and synthetic biology for pathway optimization. The scope encompasses troubleshooting common challenges such as metabolic burdens and inhibitor tolerance, and provides a comparative analysis of model and non-conventional hosts like E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and microalgae. By integrating systems biology with fermentation engineering, this review outlines a strategic framework for developing robust microbial cell factories for sustainable and economically viable biofuel production.

The Foundation of Microbial Biofactories: Core Principles and Economic Drivers

Defining Metabolic Engineering in the Context of Biofuel Production

The global energy crisis and the urgent need to mitigate climate change have catalyzed the search for sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels. Biofuels, derived from biological sources, are pivotal in this transition, offering the potential for renewable energy with reduced greenhouse gas emissions [1]. However, traditional first-generation biofuels, produced from food crops like corn and sugarcane, present significant limitations, including competition with food supply, high land-use demands, and relatively low energy efficiency [1]. The field of metabolic engineering has consequently emerged as a critical discipline to address these challenges by redesigning biological systems for enhanced production of advanced biofuels. Metabolic engineering can be defined as the targeted and systematic modification of metabolic pathways in microbial, algal, or plant systems to improve the production and yield of desired compounds—in this context, fuel-quality molecules. By leveraging sophisticated genetic tools and a deep understanding of cellular physiology, metabolic engineering aims to transform microorganisms and plants into efficient "cell factories" for the renewable synthesis of high-energy, infrastructure-compatible fuels such as butanol, isoprenoids, and fatty acid-derived compounds [2] [3]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of the principles, methodologies, and applications of metabolic engineering in developing next-generation biofuel production systems.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Metabolic engineering for biofuels operates on several foundational principles. A primary goal is to maximize the carbon flux from a renewable feedstock (e.g., sugars, lignocellulosic biomass, or CO₂) toward the pathway leading to the target biofuel molecule. This often involves rewiring central metabolism to redirect carbon from native metabolic products (e.g., for cell growth) toward the desired fuel [3]. A second principle is the optimization of redox balance, ensuring that the metabolic pathway has adequate reducing equivalents (e.g., NADPH, NADH) to drive biosynthetic reactions without causing cellular stress [3]. Furthermore, engineers strive to overcome cellular regulatory mechanisms that naturally limit the overproduction of a single metabolite, and to enhance host robustness to withstand the inherent toxicity of fuel molecules and inhibitors present in industrial feedstocks [1] [3].

The methodological toolkit for implementing these principles is extensive and continually evolving. Key approaches include:

- Heterologous Pathway Expression: Introducing complete biosynthetic pathways from other organisms into user-friendly industrial hosts like Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae. A landmark example is the reconstruction of the clostridial n-butanol pathway in E. coli [2].

- Gene Knock-Outs and Knock-Downs: Deleting or suppressing genes encoding competing or inefficient metabolic pathways to prevent carbon and energy diversion. For instance, deleting genes for lactate (ldhA), acetate (pta), and ethanol (adhE) production in E. coli significantly improved n-butanol yields by eliminating major byproducts [2].

- Precision Genome Editing: Utilizing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 for targeted, multiplexed genetic modifications. This enables precise gene insertions, deletions, and transcriptional control without the need for selective markers, dramatically accelerating the engineering cycle [4] [3].

- Enzyme Engineering: Improving the catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, or stability of key enzymes in the biofuel pathway through directed evolution or rational design [4].

- Dynamic Pathway Regulation: Implementing genetically encoded biosensors that link the concentration of a pathway intermediate or product to the expression of critical pathway genes, allowing the cell to self-regulate flux for optimal productivity [5].

Engineering Microbial Hosts for Biofuel Production

Model Organisms:E. coliandS. cerevisiae

The choice of microbial host is critical, with E. coli and S. cerevisiae serving as the predominant workhorses due to their rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, and extensive available toolkits for manipulation [3]. Table 1 summarizes key performance metrics for various advanced biofuels produced in engineered microbes, highlighting the progress enabled by metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Production Metrics of Advanced Biofuels from Engineered Microbes

| Biofuel | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Titer / Yield | Key Pathway Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Butanol | E. coli | Expression of clostridial pathway; Deletion of ldhA, adhE, frdBC, pta, fnr | 0.5 g/L (3-fold increase vs. wild-type) [2] | Thiolase (Thl/ AtoB), 3-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA Dehydrogenase (Hbd), Crotonase (Crt), Butyryl-CoA Dehydrogenase (Bcd), Butyraldehyde Dehydrogenase (Bldh), Alcohol Dehydrogenase (Adh) |

| Isobutanol | E. coli | Keto-acid pathway; Overexpression of AlsS, IlvC, IlvD; Deletion of competing pathways | ~20 g/L at 86% theoretical yield [2] | Acetolactate Synthase (AlsS), Ketoacid Reductoisomerase (IlvC), Dihydroxyacid Dehydratase (IlvD), 2-Ketoacid Decarboxylase (KivD), Alcohol Dehydrogenase (AdhA) |

| Fatty Acid-Derived Biodiesel | Various microbes | Engineering of fatty acid biosynthesis (FAS) pathway; Overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthases | 91% conversion efficiency from lipids [1] | Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (Acc), Malonyl-CoA:Acyl-ACP Transacylase (FabD), Ketoacyl-ACP Synthase (FabH/FabB/FabF) |

| Isoprenoids | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Engineering of mevalonate (MVA) or non-mevalonate (DXP) pathways; CRISPR-mediated optimization | Varies by compound (e.g., farnesene, pinene) [1] [3] | Acetyl-CoA Acetyltransferase (AtoB), HMG-CoA Synthase (MvaS), HMG-CoA Reductase (MvaE), Mevalonate Kinase (Mvk) |

Experimental Protocol: EngineeringE. colifor Isobutanol Production

The production of isobutanol in E. coli via the keto-acid pathway is a canonical example of a metabolically engineered system. The following detailed protocol outlines the key steps [2]:

Pathway Design and Gene Selection:

- Objective: Divert carbon from pyruvate (a central metabolite in glycolysis) to isobutanol.

- Pathway: Pyruvate → Acetolactate → 2,3-Dihydroxyisovalerate → 2-Ketoisovalerate → Isobutyraldehyde → Isobutanol.

- Key Heterologous Genes:

- alsS from Bacillus subtilis (encodes acetolactate synthase).

- kivD from Lactococcus lactis (encodes a broad-substrate 2-ketoacid decarboxylase).

- Key Native E. coli Genes: ilvC (encodes ketol-acid reductoisomerase), ilvD (encodes dihydroxy-acid dehydratase), and endogenous alcohol dehydrogenases (e.g., adhA).

Strain Construction:

- Vector Assembly: Clone the genes alsS, ilvC, ilvD, and kivD into one or more expression plasmids under the control of strong, inducible promoters (e.g., P_{lac}).

- Host Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid(s) into a suitable E. coli host strain (e.g., BW25113).

- Genome Deletions: Use λ-Red recombination or CRISPR-Cas9 to delete genes that compete for pyruvate or acetyl-CoA, such as those encoding lactate dehydrogenase (ldhA), fumarate reductase (frdBC), and the pyruvate-formate lyase regulator (pflB). This directs flux toward the isobutanol pathway.

Fermentation and Analysis:

- Cultivation: Grow engineered strains in a defined mineral medium with glucose as the carbon source in anaerobic or microaerobic conditions. Induce gene expression at mid-log phase.

- Product Quantification: Monitor cell growth (OD_{600}). Quantify isobutanol and byproducts (e.g., acetate, lactate) from culture supernatants using Gas Chromatography (GC) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) or GC-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

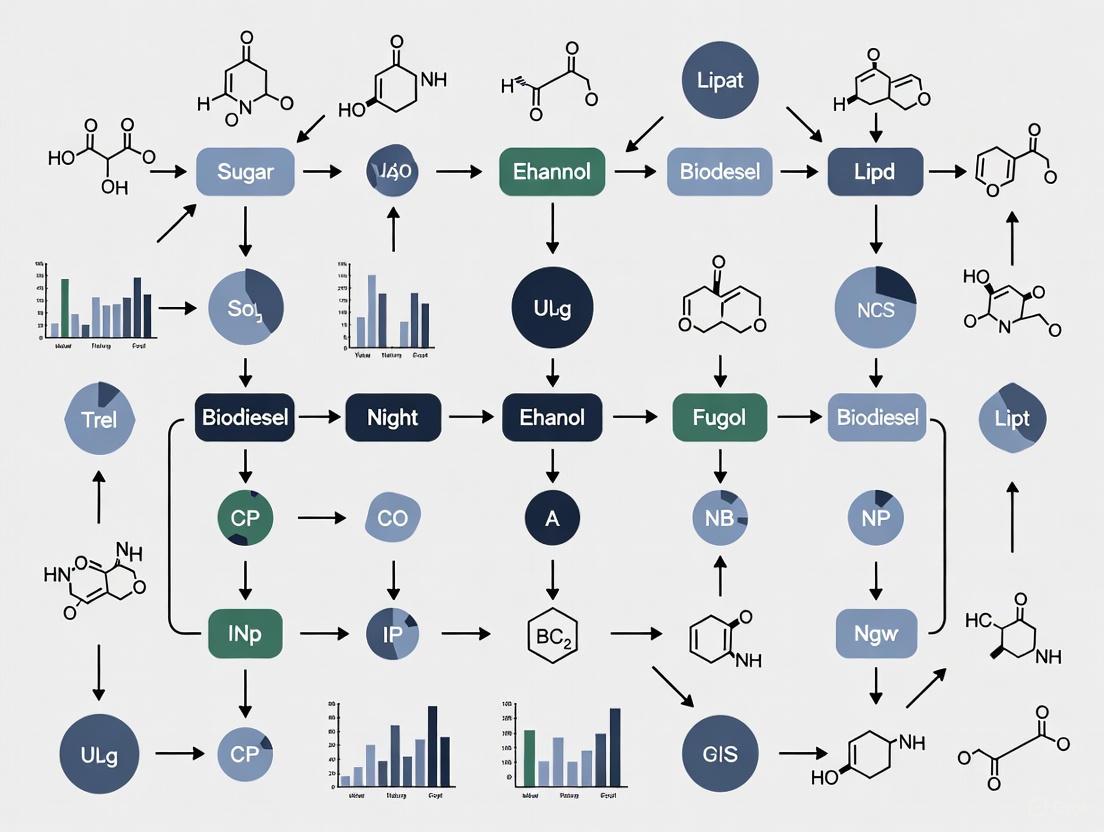

The following diagram visualizes the engineered isobutanol pathway and the associated genetic modifications within the E. coli host.

Diagram 1: Engineered Isobutanol Pathway in E. coli. Heterologous enzymes (red) divert carbon from pyruvate. Gene knockouts (blue) remove competing pathways.

Advanced Tools and Enabling Technologies

High-Throughput Screening with Biosensors

A major bottleneck in metabolic engineering is the slow pace of evaluating engineered strain libraries. Genetically encoded biosensors address this by converting intracellular metabolite levels into a detectable signal, enabling high-throughput screening [5]. The primary classes of biosensors include those based on cytosolic transcription factors (TFs), RNA riboswitches, fluorescent proteins (FRET / SFPBs), and two-component systems [5].

Application Example: A TF-based biosensor for malonyl-CoA, a key intermediate for fatty acid-derived biofuels, has been deployed in S. cerevisiae. The B. subtilis transcription factor FapR represses a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) in the absence of malonyl-CoA. When malonyl-CoA accumulates, it binds FapR, causing derepression and GFP expression. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) can then isolate high-producing cells from a large library [5].

Computational and Multi-Omics Guided Engineering

Modern metabolic engineering heavily relies on computational tools to guide design. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) simulate the entire metabolic network of an organism, allowing in silico prediction of gene knockout/overexpression effects and the identification of flux bottlenecks [3]. Furthermore, Design of Experiments (DoE) is a statistical framework used to efficiently explore the vast combinatorial space of pathway optimization (e.g., promoter strengths, enzyme variants). For a pathway with 7 genes, a full factorial design (testing all combinations) requires 128 (2⁷) strains. DoE methods like Resolution IV designs can significantly reduce this number while still capturing critical interactions between genes, making the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle more efficient [6].

The general workflow integrating these advanced tools is summarized below.

Diagram 2: The DBTL Cycle for Biofuel Strain Engineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofuel Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Model Host Organisms | Escherichia coli (e.g., BW25113, BL21), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (e.g., CEN.PK, S288C) | Well-characterized "chassis" with extensive genetic tools for heterologous pathway expression and optimization [2] [3]. |

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9 (e.g., pCAS, pTarget series), Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) | Enable precise gene knock-ins, knock-outs, and transcriptional regulation. MAGE allows simultaneous diversification of multiple genomic sites [4] [3]. |

| Specialized Enzymes | Thermophilic cellulases (e.g., from Thermobifida fusca), Ligninases, Broad-substrate 2-ketoacid decarboxylases (KivD) | Degrade lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars or catalyze key steps in non-native biofuel pathways (e.g., isobutanol) [1] [2]. |

| Biosensors | Transcription Factor-based (e.g., FapR for malonyl-CoA), FRET-based (e.g., for NADPH) | High-throughput screening of strain libraries via FACS or selection; dynamic pathway regulation [5]. |

| Analytical Chemistry | GC-FID/MS, HPLC, High-throughput MS (e.g., RapidFire, NIMS) | Gold-standard quantification of biofuel titers, rates, and yields from culture broth [5]. |

Metabolic engineering has fundamentally transformed the landscape of biofuel production, moving the field from reliance on natural fermentations toward the rational design of efficient cellular factories. By employing a sophisticated toolkit that includes heterologous pathway engineering, CRISPR-based genome editing, biosensor-driven screening, and computational modeling, researchers have demonstrated the viable production of advanced, energy-dense biofuels like isobutanol and fatty acid esters [1] [2] [3]. These fuels offer superior properties over first-generation bioethanol, including higher energy density and compatibility with existing fuel infrastructure.

Future progress will be driven by deeper integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with multi-omics data to predict optimal genetic designs [1] [6]. Furthermore, expanding the range of robust non-model hosts, engineering synthetic consortia for division of labor, and developing circular economy approaches that convert industrial waste streams and CO₂ directly into fuels represent the next frontier [1]. Overcoming the remaining challenges of host toxicity, substrate recalcitrance, and economic scalability will require sustained multidisciplinary efforts. Through continued innovation in metabolic engineering, biofuels are poised to play an increasingly central role in building a sustainable and secure global energy system.

The global energy landscape is at a pivotal juncture. Liquid and gaseous fuels currently supply more than half of global energy consumption, forming the backbone of transportation, industrial production, and electricity generation [7]. However, only approximately 2% of this consumption is supplied by clean fuels, creating a significant sustainability gap that must be addressed through technological innovation [7]. The recent "Belém 4x" pledge at COP30, where 23 countries committed to quadrupling sustainable fuel production and use by 2035, underscores the global recognition of this urgent need [7]. This transition is not merely an environmental imperative but represents a major economic opportunity, with clean fuels offering job creation potential at one-and-a-half to two times the job intensity of conventional fuels [7].

Within this context, metabolic engineering has emerged as a transformative discipline enabling the biological production of advanced biofuels. By precisely manipulating microbial metabolic pathways, researchers are developing efficient cellular factories that convert renewable feedstocks into sustainable fuels with reduced environmental impacts compared to fossil resources [1]. The integration of synthetic biology, enzyme engineering, and genome editing tools is accelerating the development of these bio-production platforms, making sustainable fuels an increasingly viable component of the global energy portfolio [4].

Biofuel Generations: Technological Evolution and Quantitative Comparison

The development of biofuels has progressed through distinct generations, each representing significant technological advances and addressing limitations of previous approaches. Understanding this evolution is critical for contextualizing current research directions in metabolic engineering for biofuel production.

Table 1: Comparison of Biofuel Generations and Their Characteristics

| Generation | Feedstock Type | Technology | Yield (per ton feedstock) | Sustainability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Food crops (corn, sugarcane) | Fermentation, transesterification | Ethanol: 300–400 L | Competes with food supply; high land use [1] |

| Second | Crop residues, lignocellulose | Enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation | Ethanol: 250–300 L | Better land utilization; moderate GHG savings [1] |

| Third | Algae | Photobioreactors, hydrothermal liquefaction | Biodiesel: 400–500 L | High GHG savings; scalability challenges [1] |

| Fourth | Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) | CRISPR, synthetic biology, electrofuels | Varies (hydrocarbons, isoprenoids) | High potential; regulatory considerations [1] |

First-generation biofuels, derived from food crops like corn and sugarcane, utilize established production methods but face significant criticism due to the food-versus-fuel competition and substantial land requirements [1]. Second-generation biofuels instead utilize non-food lignocellulosic feedstocks such as crop residues and dedicated energy crops, offering improved sustainability profiles but facing challenges related to feedstock recalcitrance and conversion efficiency [1]. Third-generation biofuels, primarily derived from algae, offer high biomass and oil yields without competing with agricultural land, though scale-up issues and production costs remain obstacles [1].

Fourth-generation biofuels represent the cutting edge of biofuel technology, leveraging synthetic biology to create engineered microbial systems for fuel production [1]. These approaches include genetically modified algae with enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and lipid accumulation, photobiological solar fuels, and electro-fuels produced through engineered metabolic pathways [1]. The application of advanced genome-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN enables precise reprogramming of metabolic networks to optimize biofuel production [1].

Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Metabolic engineering has revolutionized biofuel production by enabling the optimization of microorganisms for enhanced substrate utilization, biofuel synthesis, and industrial resilience. Through precise genetic modifications, microbial hosts can be transformed into efficient biofactories for sustainable fuel production.

Engineering Microbial Metabolism for Biofuel Production

Advanced metabolic engineering approaches have yielded significant improvements in biofuel production efficiency. Notable achievements include a 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency from microbial lipids and a three-fold increase in butanol yield in engineered Clostridium species [1]. For bioethanol production, engineered S. cerevisiae strains have achieved approximately 85% conversion efficiency of xylose to ethanol, significantly improving the utilization of lignocellulosic sugars [1]. These advances demonstrate the powerful role of metabolic engineering in overcoming natural metabolic limitations for industrial biofuel production.

The integration of synthetic biology has further expanded the capabilities of biofuel-producing microorganisms. Synthetic biology enables the precision manipulation of metabolic pathways using tools like CRISPR-Cas9, allowing researchers to design and construct biosynthetic circuits for the conversion of carbon dioxide and other waste streams into advanced biofuels [1]. These approaches facilitate the production of drop-in fuels with superior energy density and full compatibility with existing transportation infrastructure, including jet fuel analogs and other hydrocarbons [1].

Enzymatic Innovations in Biomass Conversion

The efficient conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to fermentable sugars represents a critical step in advanced biofuel production. Key enzymes including cellulases, hemicellulases, and ligninases facilitate the breakdown of recalcitrant biomass components [1]. Recent innovations have focused on developing thermostable and pH-tolerant enzyme variants to withstand industrial processing conditions [1]. Additionally, the optimization of lignin-degrading enzymes and the development of co-catalytic systems have significantly improved the efficiency and reduced the costs of bioconversion processes [1].

Metagenomic approaches are being employed to discover novel enzymes from uncultured microbial consortia, expanding the repertoire of biocatalysts available for biomass deconstruction [4]. Through functional gene analysis and enzyme engineering, researchers are identifying and optimizing enzymes with enhanced activity against recalcitrant biomass components, thereby improving the overall efficiency of biofuel production pipelines [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Metabolic Engineering in Biofuel Production

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application in Biofuel Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precision genome editing for metabolic pathway engineering [1] [4] |

| Cellulases, Hemicellulases | Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose/hemicellulose to fermentable sugars [1] |

| Ligninases | Degradation of lignin to access polysaccharides in biomass [1] |

| Engineered Microorganisms | Biofuel production hosts (e.g., Clostridium spp., S. cerevisiae, algae) [1] |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Discovery of novel enzymes from uncultured microbial communities [4] |

| Synthetic Biosynthetic Circuits | Programmed metabolic pathways for advanced biofuel synthesis [1] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Consolidated Bioprocessing Protocol

Consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) represents an integrated approach that combines enzyme production, biomass hydrolysis, and sugar fermentation into a single step. The following protocol outlines a standard methodology for implementing CBP in biofuel production:

Strain Engineering: Utilize CRISPR-Cas9 systems to introduce or enhance cellulolytic capabilities in ethanologenic strains such as S. cerevisiae or Zymomonas mobilis. Alternatively, introduce biofuel synthesis pathways into naturally cellulolytic organisms like Clostridium thermocellum [1].

Inoculum Preparation: Grow engineered strains in seed culture medium (e.g., YPD for yeast or reinforced clostridial medium for Clostridium) overnight at optimal growth temperatures (30°C for yeast, 55-60°C for thermophilic Clostridium).

Biomass Pretreatment: Subject lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover, switchgrass) to alkaline or dilute acid pretreatment at 121°C for 30-60 minutes to partially degrade lignin and hemicellulose.

Bioreactor Setup: Transfer pretreated biomass to bioreactor at 5-10% (w/v) solid loading. Supplement with minimal nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, trace elements) without external hydrolytic enzymes.

Inoculation and Process Monitoring: Inoculate bioreactor with 10% (v/v) seed culture. Maintain anaerobic conditions for bacterial fermentation or microaerobic conditions for yeast fermentation. Monitor sugar consumption, inhibitor tolerance (furan, phenolic compounds), and biofuel production over 72-120 hours.

Product Recovery: Employ distillation for volatile fuels (ethanol, butanol) or in-situ extraction using organic solvents (e.g., dodecanol) for continuous product removal to mitigate toxicity.

This integrated approach significantly reduces operational costs by eliminating separate enzyme production and hydrolysis steps, though it requires robust engineered strains capable of both biomass degradation and fuel production [1].

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution for Enhanced Strain Performance

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) is employed to enhance microbial tolerance to inhibitors and overall biofuel productivity:

Baseline Assessment: Determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of target biofuel (e.g., butanol, isoprenoid) or hydrolysate inhibitors (furfural, HMF) for the initial strain.

Serial Passaging: Inoculate cultures in medium containing sub-inhibitory concentrations of stressors. Perform daily transfers (1-2% v/v inoculum) to fresh medium, gradually increasing stressor concentrations by 5-15% each transfer.

Monitoring and Screening: Track growth rates (OD600) and product tolerance weekly. Isolate clones from endpoint populations showing improved growth under stress conditions.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: Utilize whole-genome sequencing of evolved strains to identify causal mutations through comparison with ancestral strains.

Characterization of Evolved Strains: Evaluate performance in bioreactors under industrial conditions, assessing key metrics including titer (g/L), yield (g product/g substrate), and productivity (g/L/h).

This protocol enables the development of robust industrial strains with enhanced tolerance to process-derived inhibitors and improved biofuel production capabilities [1].

Visualization of Metabolic Engineering Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key metabolic engineering workflows and signaling pathways for advanced biofuel production, created using DOT language and compliant with the specified color and contrast requirements.

Diagram 1: Biomass to Biofuel Conversion Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Metabolic Pathways for Biofuel Synthesis

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances, several technical and economic challenges remain in the widespread implementation of metabolic engineering for sustainable fuel production. Key barriers include biomass recalcitrance, limited biofuel yields, and economic feasibility concerns that hinder commercial scalability [1]. Additionally, regulatory hurdles and societal acceptance of genetically modified organisms represent significant implementation challenges [1].

Future research directions should focus on leveraging artificial intelligence for enzyme and pathway discovery, expanding non-food feedstock utilization, and enhancing policy frameworks to support international cooperation [1]. Emerging strategies such as consolidated bioprocessing, adaptive laboratory evolution, and AI-driven strain optimization show considerable promise for addressing current limitations [1]. The integration of biofuel production within circular economy frameworks, with an emphasis on waste recycling and carbon-neutral operations, will be essential for achieving true sustainability [1].

Multidisciplinary research approaches integrating metabolic engineering, systems biology, process engineering, and sustainability science are essential to enhance both the economic viability and environmental performance of biofuel technologies [1]. Through continued innovation and collaboration, biofuels produced via advanced metabolic engineering can play a central role in global renewable energy systems and contribute significantly to the transition away from fossil resources.

The transition from fossil-based fuels to sustainable alternatives is a cornerstone of global decarbonization efforts. Biofuels, derived from biological sources, represent a promising path forward, particularly when their production is enhanced through advanced metabolic engineering. This field involves the deliberate modification of microbial metabolic pathways to optimize the production of target compounds, creating efficient cellular factories for biofuel synthesis [3]. The evolution of biofuels is categorized into generations, each defined by its feedstock and technological sophistication. First-generation biofuels, such as bioethanol and biodiesel, are produced from food crops like corn and sugarcane, raising concerns about competition with food supply and land use [1] [8]. Second-generation biofuels utilize non-food lignocellulosic biomass—such as agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover, wheat straw), wood chips, and dedicated energy crops (e.g., switchgrass)—to produce advanced biofuels like cellulosic ethanol and renewable diesel, thereby avoiding the food-versus-fuel dilemma [9] [1]. Third-generation biofuels primarily use microalgae as a feedstock, offering high biomass yields and the ability to cultivate on non-arable land [1]. Fourth-generation biofuels further advance this concept by employing synthetic biology and genetically modified (GM) microorganisms (e.g., algae, cyanobacteria) designed for enhanced carbon capture, higher lipid production, and direct secretion of hydrocarbon fuels [1].

Metabolic engineering serves as a pivotal tool across these generations, enabling researchers to rewire the core metabolism of model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [3]. Through strategies such as heterologous gene expression, pathway optimization, and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, scientists can significantly increase the yield and efficiency of biofuel production, paving the way for commercially viable, next-generation hydrocarbons [1] [3].

Conventional Biofuel Molecules: Properties and Production

Conventional biofuels, primarily first-generation, have established the commercial market for renewable fuels. The two most prominent examples are ethanol and biodiesel (FAME), which are commonly blended with their petroleum counterparts.

Bioethanol (C₂H₅OH): Bioethanol is an alcohol produced primarily via the fermentation of sugars by microorganisms like yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). First-generation production relies on sugar- or starch-based crops like corn and sugarcane [9]. Second-generation cellulosic ethanol employs enzymatic hydrolysis to break down lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., agricultural residues) into fermentable sugars, a process enhanced by engineering microbes to express cellulolytic enzymes [9] [3]. It is widely used as a blending agent in gasoline (e.g., E10, E15, E85) to increase octane and reduce carbon monoxide emissions [9]. Its production is a mature technology, with global leaders including Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) and Valero in the US, and Raízen in Brazil [10].

Biodiesel (FAME): Biodiesel, or Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME), is produced via transesterification of vegetable oils, animal fats, or waste cooking oils with methanol [9]. This chemical reaction converts triglycerides into biodiesel and glycerol. It is a direct replacement for petroleum diesel, used in blends like B5 (5% biodiesel) or B20 (20% biodiesel) in compression-ignition engines [9]. Major producers include Renewable Energy Group (REG) and Neste [10]. While it reduces particulate matter and sulfur emissions, it has limitations such as lower energy density and cold-weather performance issues compared to conventional diesel [11].

Table 1: Properties of Conventional and Emerging Biofuels

| Fuel Molecule | Chemical Formula | Feedstock | Energy Content (Lower Heating Value) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline (Reference) | C4-C12 Hydrocarbons | Crude Oil | 112,114–116,090 Btu/gal [11] | - | - |

| Bioethanol | C₂H₅OH | Corn, Sugarcane, Cellulosic Biomass | 76,330 Btu/gal (E100) [11] | High Octane Number (110) [11] | 33% lower energy content than gasoline [11] |

| Biodiesel (FAME) | R–COOCH₃* | Soybean Oil, Waste Oils | 119,550 Btu/gal (B100) [11] | Biodegradable, reduces particulates | Lower energy density than diesel [11] |

| Renewable Diesel | C8-C25 Hydrocarbons | Fats, Oils, Greases | 123,710 Btu/gal [11] | Drop-in fuel, high cetane (70-85) [11] | High production cost (CapEx) [12] |

| n-Butanol | C₄H₉OH | Lignocellulosic Biomass | ~105,000 Btu/gal (Est.) | Higher energy density than ethanol, blendable [3] | Toxicity to production microbes [3] |

| Green Hydrogen | H₂ | Water, Renewable Electricity | 51,585 Btu/lb [11] | Zero CO₂ combustion, energy carrier | Low energy density, storage challenges [10] |

| Green Ammonia | NH₃ | Air, Water, Renewable Electricity | ~ | Hydrogen carrier, zero-carbon fuel | Toxicity, requires new infrastructure [10] |

*R represents a long-chain alkyl group derived from fatty acids.

Advanced Hydrocarbon Biofuels: The "Drop-In" Solution

Advanced biofuels, often termed "drop-in" fuels, are hydrocarbons that are chemically identical to their petroleum-derived counterparts (gasoline, diesel, jet fuel). This makes them fully compatible with existing engines, pipelines, and distribution infrastructure, a significant advantage over conventional biofuels like ethanol and FAME biodiesel [9] [13]. Key molecules include renewable diesel, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and biofuels derived from fatty acid and isoprenoid pathways.

Renewable Diesel (HVO/HEFA): Also known as Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) or Green Diesel, it is produced via hydroprocessing of fats, oils, and greases. The process, known as Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA), uses hydrogen to remove oxygen from triglycerides, producing straight-chain alkanes (C8-C25) identical to fossil diesel [10] [13]. It features a high cetane number (70-85) and superior cold-weather performance compared to FAME [11]. HEFA is also the dominant pathway for producing Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), which is a drop-in replacement for conventional jet fuel [13].

Biofuels from Fatty Acid and Isoprenoid Pathways: Metabolic engineering enables the production of advanced hydrocarbons directly in microorganisms.

- Fatty Acid-Derived Biofuels: Engineered E. coli and yeast can be tailored to overproduce fatty acids, which are then converted into alkanes, alkenes, and esters through modified metabolic pathways. These molecules serve as precursors for renewable diesel and jet fuel [1] [3].

- Isoprenoid-Based Biofuels: Isoprenoids are a large class of natural compounds that can be synthesized into high-energy density fuels, such as pinene and limonene, which are suitable as jet fuel substitutes. Engineering the mevalonate or non-mevalonate pathways in microbes allows for the production of these advanced isoprenoid biofuels [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Biofuel Production Pathways

| Production Pathway | Key Feedstock | Primary Output(s) | Technology Readiness | Minimum Product Selling Price (MPSP) Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEFA/HVO | Vegetable Oils, Animal Fats | Renewable Diesel, SAF | Commercial | Highly dependent on feedstock cost [13] |

| Gasification + Fischer-Tropsch | Lignocellulosic Biomass | Diesel, Jet Fuel | Demonstration | High Capital Expenditure (CapEx) [12] [13] |

| Pyrolysis + Upgrading | Biomass, Plastic Waste | Bio-Crude Oil | Pilot/Demonstration | Moderate to High [9] [13] |

| Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) | Ethanol, Isopropanol | Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) | Early Commercial | Decreasing with process optimization [13] |

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) | Wet Biomass, Algae | Bio-Crude Oil | Pilot/Demonstration | Moderate [9] |

Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Production

Metabolic engineering is central to overcoming the natural limitations of microorganisms for industrial biofuel production. The following strategies and protocols are employed to develop robust microbial cell factories.

Microbial Engineering for Lignocellulosic Biomass Utilization

Lignocellulosic biomass is a complex polymer of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Engineering microbes to efficiently deconstruct and utilize this biomass is critical for second-generation biofuels.

- Experimental Protocol: Engineering a Cellulolytic Consortium

- Gene Identification & Cloning: Identify and clone genes for key hydrolytic enzymes (endoglucanases, exoglucanases, β-glucosidases, xylanases) from cellulolytic microbes into suitable expression vectors [3].

- Strain Development: Genetically engineer separate yeast strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae) to express either a) a scaffoldin protein (e.g., mini CipA) or b) different cellulases engineered with dockerin domains that bind to the scaffoldin [3] [3].

- Consortium Cultivation: Co-culture the engineered strains in a consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) setup with pre-treated lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover) as the sole carbon source.

- Analysis: Monitor sugar release, microbial growth, and biofuel (e.g., ethanol) production over time via HPLC and GC-MS. Engineered consortia have demonstrated direct ethanol production from cellulose [3].

Overcoming Inhibitor Tolerance

Pre-treatment of lignocellulose generates microbial growth inhibitors like furfural and acetic acid. Engineering tolerance is essential.

- Strategy: In E. coli, furfural induces oxidative stress and depletes NADPH. A key protocol involves:

- Deleting the gene for the NADPH-consuming oxidoreductase (yqhD).

- Overexpressing the pntAB genes for transhydrogenase activity to balance NADPH/NADH pools.

- Supplementing the medium with cysteine to rescue sulfate assimilation [3]. This combined approach has been shown to significantly enhance microbial growth in the presence of furfural [3].

Pathway Optimization for Advanced Biofuels

Engineering pathways for molecules like n-butanol and isoprenoids requires precise genetic manipulation.

- Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Pathway Engineering in E. coli for n-Butanol

- Target Selection: Select the native E. coli pathway competing for the acetyl-CoA pool (e.g., the ldhA gene for lactate production).

- CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting ldhA. Co-transform the sgRNA and Cas9 nuclease into E. coli to generate a clean knockout mutant [3].

- Heterologous Pathway Insertion: Introduce a plasmid containing the complete clostridial n-butanol biosynthesis pathway (thl, hbd, crt, bcd-etfAB, adhE2) under a strong constitutive promoter.

- Fermentation & Analysis: Cultivate the engineered strain in a bioreactor with defined glucose medium. Analyze n-butanol titer using GC-MS and calculate yield (g/g glucose). Engineered strains have achieved a 3-fold increase in butanol yield [1].

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow for developing a metabolically engineered microbe for biofuel production.

Diagram 1: Metabolic engineering workflow for biofuel production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Technologies

Successful metabolic engineering for biofuels relies on a suite of sophisticated reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Biofuel Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise, multiplex genome editing (e.g., gene knockouts, promoter swaps) in model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae to redirect metabolic flux [1] [3]. |

| Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) | Allows high-throughput, iterative genomic modifications across multiple target sites simultaneously, accelerating the evolution of optimized production strains [3]. |

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzyme Cocktails | Pre-formulated enzyme mixtures used to hydrolyze pre-treated lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars (glucose, xylose) for microbial fermentation [9] [3]. |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) Software | Computational tools (e.g., COBRApy) that use 13C-labeling and mass spectrometry data to quantify intracellular metabolic reaction rates, identifying bottlenecks in biofuel synthesis pathways [3]. |

| GC-MS / HPLC Systems | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are essential for quantifying biofuel titers, yield, and productivity, and for analyzing metabolic intermediates [3]. |

| Synthetic Gene Circuits | Engineered genetic components (promoters, ribosome binding sites, reporters) used to construct orthogonal metabolic pathways and biosensors for real-time monitoring of pathway activity [1]. |

The journey from first-generation ethanol to advanced, engineered hydrocarbon biofuels illustrates a paradigm shift toward sustainable and infrastructure-compatible energy sources. Metabolic engineering, powered by tools like CRISPR-Cas9 and sophisticated modeling, is the key driver in this transition, enabling the creation of efficient microbial cell factories [1] [3]. The continued development of "drop-in" fuels like renewable diesel and SAF via HEFA and other pathways is crucial for decarbonizing hard-to-electrify sectors such as aviation and shipping [13].

Future progress hinges on multidisciplinary research focused on several frontiers: the development of non-model organisms with unique tolerances and metabolic capabilities; the application of AI and machine learning to predict optimal genetic edits and fermentation conditions; and the full integration of biofuel production within a circular bioeconomy framework that valorizes all biomass streams [1] [8]. While challenges in economic viability, scalability, and feedstock sustainability remain, the integration of synthetic biology with process engineering promises to unlock the full potential of biofuels, solidifying their role in a comprehensive renewable energy portfolio.

Central Metabolic Pathways as Platforms for Biofuel Synthesis

The global energy crisis and the urgent need to mitigate climate change have driven the search for sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels [3]. Biofuels, produced from renewable biological resources, represent a promising solution. Metabolic engineering has emerged as a pivotal discipline for optimizing microbial cellular factories, redesigning their metabolic networks to enhance the production of valuable compounds, including advanced biofuels [3] [14]. Unlike first-generation biofuels derived from food crops, next-generation biofuels are produced from non-food feedstocks like lignocellulosic biomass and are engineered to have properties similar to conventional fossil fuels, such as higher energy density and better compatibility with existing infrastructure [3] [15].

This technical guide explores how central metabolic pathways in model microorganisms are engineered to serve as platforms for the synthesis of these advanced biofuels. We focus on the scientific principles and methodologies that enable the redirection of carbon flux from central metabolism toward the high-yield production of molecules like n-butanol, iso-butanol, isoprenoid-based fuels, and fatty acid-derived biofuels [3]. The integration of synthetic biology tools, such as CRISPR-Cas systems, with traditional metabolic engineering is opening new paths to develop robust industrial strains, paving the way for a sustainable bio-based economy [3] [15].

Engineering Central Metabolism for Biofuel Synthesis

The primary objective in engineering central metabolism for biofuel production is to rewire the native metabolic network to redirect carbon flow from key intermediates toward the desired fuel molecules. This involves introducing novel synthetic pathways and optimizing the host's physiology to maximize yield, titer, and productivity.

Key Metabolic Pathways and Precursors

Central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, generates precursor molecules that serve as the building blocks for biofuel synthesis. The table below summarizes the key precursors and their roles.

Table 1: Key Central Metabolites as Biofuel Precursors

| Central Metabolite | Origin in Central Metabolism | Target Biofuels |

|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | Pyruvate decarboxylation, Fatty acid β-oxidation | Fatty acid-derived biofuels (alkanes, alkenes, fatty acid esters), Isoprenoids, n-Butanol, Iso-butanol |

| Pyruvate | Glycolysis | Iso-butanol, n-Butanol, Fatty acids (via acetyl-CoA) |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) & Pyruvate | Glycolysis, Calvin cycle (in photosynthetic organisms) | Isoprenoids (via the MEP pathway) |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | Glycolysis | Aromatic compounds, enhancement of precursor supply |

Synthetic Pathways for Advanced Biofuels

The Isoprenoid Pathway

Isoprenoids (terpenoids) represent a vast class of compounds with potential as advanced biofuels, such as bisabolane (a diesel substitute) and pinene (a jet fuel precursor) [16] [3]. Their biosynthesis relies on two key, five-carbon precursor molecules: isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) [16].

Microorganisms employ one of two pathways to produce IPP and DMAPP:

- The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway: Predominant in most eukaryotes and some bacteria, using acetyl-CoA as a precursor.

- The 2-C-Methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) Pathway: Found in most bacteria and the plastids of plant cells, using pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) as precursors [16].

Notably, some organisms like diatoms possess both pathways, while most green algae contain only the MEP pathway [16]. Engineering these pathways in hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae involves overexpressing key enzymes, knocking out competing pathways, and balancing the supply of precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA for the MVA pathway) to drive carbon flux toward isoprenoid biosynthesis [16] [14].

The Fatty Acid Biosynthesis Pathway

Fatty acid biosynthesis, starting from acetyl-CoA, provides acyl-ACPs and fatty acids that can be converted into a diverse range of biofuels. These include fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs), which are biodiesel components, as well as medium and long-chain alkanes and alkenes that are direct replacements for petroleum-based gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel [3]. Metabolic engineering strategies focus on:

- Overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthases (FAS) to boost the initial steps of fatty acid production.

- Introduction of heterologous enzymes like acyl-ACP thioesterases, fatty acid decarboxylases (e.g., OleTJE), and aldehyde deformylating oxygenases (ADOs) to convert the fatty acid intermediates into finished fuel molecules.

- Engineering cofactor supply, particularly NADPH, which is essential for fatty acid biosynthesis [3].

Non-Fermentative Pathways for Higher Alcohols

While ethanol is a well-known biofuel, higher alcohols like n-butanol and iso-butanol offer superior energy density and lower hygroscopicity. Synthetic biology has enabled the construction of non-fermentative pathways for their production.

- n-Butanol: Typically produced by introducing the CoA-dependent pathway from Clostridium species into E. coli or S. cerevisiae, utilizing acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA as precursors.

- Iso-butanol: Synthesized from pyruvate via the valine biosynthesis pathway, involving acetolactate synthase (ALS) and subsequent decarboxylation and dehydrogenation steps [3] [14].

A key challenge in these pathways is the imbalance of enzyme expression levels, which can lead to the accumulation of toxic intermediates. Pathway optimization is therefore critical [17] [14].

Quantitative Performance of Engineered Pathways

Extensive metabolic engineering has led to significant improvements in the production metrics of various biofuels. The following table summarizes representative data from engineered microbial systems.

Table 2: Biofuel Production Metrics in Engineered Microbes

| Biofuel Product | Host Organism | Key Engineering Strategy | Reported Titer/Yield/Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| n-Butanol | Engineered Clostridium spp. | Metabolic pathway optimization | 3-fold yield increase reported [15] |

| Iso-butanol | E. coli | Non-fermentative pathway from pyruvate | Data not specified in search results |

| Isoprenoid-based Fuels | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | MVA or MEP pathway engineering; precursor balancing | Data not specified in search results |

| Fatty Acid-derived Biodiesel | Various microbes | Engineered β-oxidation reversal & esterification | 91% conversion efficiency from lipids [15] |

| Ethanol from Xylose | S. cerevisiae | Engineered co-utilization of xylose and glucose | ~85% conversion from xylose [15] |

| Lycopene (Isoprenoid model) | E. coli | RBS optimization, codon usage, gene order shuffling | Data not specified in search results |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Engineering

The construction and optimization of synthetic pathways for biofuel production follow a cyclical process of design, build, test, and learn (DBTL). Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments in this workflow.

Protocol 1: Constructing a Synthetic Metabolic Pathway using Oligo-Linker Mediated Assembly (OLMA)

The OLMA method is a PCR-free and zipcode-free DNA assembly technique ideal for simultaneously varying multiple regulatory targets (promoters, RBSs, gene order, coding sequences) in a pathway [17].

Materials:

- DNA Modules: Gene coding sequences (e.g., crtE, crtB, crtI, idi for lycopene pathway) cloned in a standard vector.

- Double-Stranded Oligonucleotides (Ds-oligos): Chemically synthesized, designed to function as linkers, promoters, and RBSs with specific overhangs.

- Enzymes: T4 DNA Ligase, T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (for phosphorylation).

- Host Strain: Competent E. coli cells.

Procedure:

- Design and Prepare Ds-oligos: Design a library of oligonucleotides with overhangs that will bridge the DNA modules in the desired order. These oligos can also encode regulatory elements like RBSs of varying strengths, predicted using tools like the RBS Calculator [17]. Anneal complementary single strands and phosphorylate them using T4 PNK.

- Prepare DNA Modules: Digest the standard vectors containing the coding sequences with appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI for Golden Gate assembly) to release the modules with specific overhangs.

- Assembly Reaction: Set up a ligation reaction containing the digested DNA modules, the phosphorylated Ds-oligo linkers, T4 DNA Ligase, and buffer. The overhangs on the Ds-oligos will direct the sequential and correct assembly of the modules.

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli cells. Plate on selective media. Screen colonies for the desired phenotype (e.g., color for lycopene) or via colony PCR and sequencing to confirm the correct assembly of the pathway [17].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Pathways using CRISPR-dCas12a Genetic Circuits

CRISPR-dCas12a systems allow for multiplexed, fine-tuned regulation of pathway genes without cutting DNA, enabling dynamic pathway optimization [18].

Materials:

- Plasmids: Expressing dCas12a protein and guide RNAs (gRNAs).

- gRNA Library: Designed to target the promoters or coding sequences of genes in the biofuel pathway.

- Host Strain: E. coli or S. cerevisiae with the integrated biofuel pathway.

Procedure:

- Design and Clone gRNA Library: Design a library of gRNAs targeting different genes in the synthetic pathway with varying binding affinities. Clone them into a suitable expression vector.

- Cohort Assembly: Co-transform the dCas12a expression plasmid and the gRNA library into the production host.

- Screening and Selection: Culture the transformed population under selective pressure for biofuel production. Use high-throughput screening (e.g., fluorescence-activated cell sorting linked to a biosensor) or selective growth conditions to isolate high-producing clones.

- Validation and Analysis: Quantify biofuel titer in the selected clones using methods like GC-MS or HPLC. Analyze the gRNA sequences in the best performers to identify optimal repression/activation levels for each gene in the pathway [18].

Protocol 3: Integrating Machine Learning for Pathway Optimization

Machine learning (ML) models can predict optimal pathway configurations by learning from large multi-parameter datasets, drastically reducing experimental trial-and-error [19].

Materials:

- Dataset: Historical data on strain performance (titer, yield, productivity) with corresponding genetic modifications (promoter strength, RBS variants, gene copy number).

- Computational Resources: Software for ML model training (e.g., Python with Scikit-learn, TensorFlow).

Procedure:

- Data Generation and Curation: Generate a training dataset by measuring biofuel production from a diverse library of engineered strains (e.g., created via OLMA or CRISPR). Record all engineering parameters (genotype) and production metrics (phenotype).

- Model Training: Train an ML model (e.g., Random Forest, Bayesian Optimization, Neural Network) to map the genotype to the phenotype. Use k-fold cross-validation to assess model performance.

- Prediction and Design: Use the trained model to predict the performance of new, untested genetic combinations. Select the top-performing predicted designs for experimental validation.

- Iterative Learning (DBTL Cycle): Incorporate the new experimental results back into the dataset to retrain and improve the ML model in the next iteration of the DBTL cycle [19].

Pathway Diagrams and Engineering Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core metabolic pathways and key engineering workflows discussed in this guide.

Central Metabolism and Biofuel Synthesis Pathways

Metabolic Engineering DBTL Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key reagents, tools, and methodologies essential for conducting metabolic engineering research in biofuel synthesis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Engineering

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Function and Application in Biofuel Research |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly Systems | Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate Assembly, OLMA (Oligo-Linker Mediated Assembly) | Seamless construction of large DNA constructs, pathways, and combinatorial libraries; OLMA allows simultaneous variation of promoters, RBS, gene order [17]. |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-dCas12a (for regulation), MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) | Precision gene knockout, activation, or repression (CRISPRi/a); multiplexed genome editing for rapid strain optimization [3] [18]. |

| Regulatory Element Libraries | Synthetic Promoter Libraries, RBS Library (designed using RBS Calculator) | Fine-tuning the transcriptional and translational strength of each gene in a pathway to balance enzyme expression and eliminate metabolic bottlenecks [17] [14]. |

| Analytical Techniques | HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography), GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Quantification of biofuel titers, yields, and productivity; identification and measurement of metabolic intermediates [3]. |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Bayesian Optimization, Random Forest, Neural Networks | Analyzing multi-omic datasets, predicting optimal genetic designs, and guiding the DBTL cycle to accelerate strain development [19]. |

| Host Organisms | Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Clostridium spp., Microalgae (e.g., C. reinhardtii) | Model chassis organisms with well-characterized genetics and metabolism for heterologous pathway expression; microalgae offer photosynthetic CO₂ fixation [16] [3]. |

| Pathway-Specific Enzymes | Terpene Synthases (for isoprenoids), Thioesterases/Decarboxylases (for fatty acid-derived fuels), ALS/Decarboxylase (for iso-butanol) | Heterologous enzymes that define the synthetic pathway and catalyze the formation of the final biofuel molecule from central metabolites [16] [3] [14]. |

The Metabolic Engineering Market and Key Industrial Players

The metabolic engineering market is experiencing a period of significant expansion, driven by the global push for sustainable, bio-based alternatives to petroleum-derived products. Metabolic engineering, which involves modifying an organism's metabolic pathways to optimize the production of target substances, has become a cornerstone of industrial biotechnology. The market's growth is underpinned by technological advancements in synthetic biology, gene editing, and bioprocess optimization, which collectively enhance the efficiency and scope of bio-manufacturing.

Table 1: Global Metabolic Engineering Market Forecast

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Market Size (2025) | USD 6.72 Billion | [20] |

| Projected Market Size (2032) | USD 12.9 Billion | [20] |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 10.3% | 2025-2032 [20] |

| Alternative 2025 Estimate | USD 10.2 Billion | [21] |

| Alternative 2033 Forecast | USD 21.4 Billion | [21] |

This robust growth is fueled by several key drivers. Escalating demand for sustainable bio-based products amid tightening environmental regulations is a primary factor, particularly in the biofuels sector [20] [21]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning has dramatically reduced development cycles for novel pathways by up to 40%, accelerating innovation [20]. The expanding application of metabolic engineering in pharmaceutical manufacturing, especially for complex biologics like monoclonal antibodies, is another significant contributor, with this segment itself experiencing a CAGR of about 15% [20].

The market is segmented by technology, application, and organism type, each presenting distinct opportunities.

Table 2: Market Segmentation and Key Characteristics

| Segment | Category | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| By Technology | Gene Editing Tools (e.g., CRISPR) | Precise genome modification; saw 12% price reduction in kits in 2025, boosting adoption [20]. |

| Systems Biology Platforms | Holistic analysis of metabolic networks for targeted engineering [20]. | |

| Bioprocess Optimization & Bioinformatics | Enhances production efficiency and yield in bioreactors [20] [22]. | |

| By Application | Biofuels | Driven by energy security and emissions norms; focus on lignocellulosic biomass conversion [20] [23]. |

| Pharmaceuticals | High-value segment; production of therapeutics, vaccines, and complex biologics [20] [24]. | |

| Specialty Chemicals & Food & Beverages | Includes bioplastics, rare sugars, flavors, and enzymes [20] [24]. | |

| By Organism Type | Bacteria (e.g., E. coli) | Versatile and well-understood chassis; widely used for diverse products [24] [22]. |

| Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Robust platform for ethanol, bio-pharmaceuticals; engineered for xylose utilization [23] [22]. | |

| Algae & Cyanobacteria | Explored for biodiesel and direct CO₂ conversion to fuels [23] [22]. |

Geographically, North America currently holds a dominant market share, but the Asia-Pacific region is expected to witness the fastest growth, with growth rates surpassing 12% in 2024, propelled by expanding bio-based industries and increased governmental funding [20].

Key Industrial Players and Competitive Strategies

The metabolic engineering landscape is populated by a mix of established industrial giants and agile biotechnology pioneers. These companies compete and collaborate to develop superior microbial strains, efficient processes, and innovative products.

Table 3: Key Companies in the Metabolic Engineering Landscape

| Company | Primary Focus / Specialty | Notable Activities / Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Ginkgo Bioworks | Organism Design & Platform | Partnership with chemical manufacturers led to 25% increase in industrial enzyme production efficiency (2024) [20]. |

| Amyris Inc. | Synthetic Biology & Biofuels | Acquired synthetic biology startups, achieving 30% market share boost in biofuels [20]. |

| Genomatica Inc. | Bio-based Chemicals | Technology leader for chemical industry; produces intermediates from renewable feedstocks [20] [25]. |

| Novozymes A/S | Industrial Enzymes & Microorganisms | Leading producer of enzymes for biomass degradation and other industrial processes [20] [21]. |

| LanzaTech | Gas Fermentation & Waste Valorization | Uses engineered microbes to convert industrial waste gases (e.g., CO) into ethanol and chemicals [20]. |

| DSM | Materials & Nutritional Products | Active in biotechnology for materials and nutritional products [20]. |

| Cysbio | Metabolic Engineering for Biochemicals | Uses synthetic biology to create bacterial cell factories converting sugars to high-value biochemicals [26]. |

| Pivot Bio | Agricultural Biologicals | Engineers nitrogen-fixing microbes to reduce synthetic fertilizer use [26]. |

The competitive landscape is characterized by continuous innovation and strategic alliances. Common go-to-market strategies include collaborative R&D, mergers and acquisitions, and technology licensing to expand portfolio capabilities, reduce time to market, and capture increased market share [20]. Despite the positive outlook, companies in this space face significant challenges, including high capital expenditure, regulatory complexities, and difficulties in scaling up processes with reproducibility [20].

Metabolic Engineering in Biofuel Production: Applications and Methodologies

Within the broader market, the application of metabolic engineering for biofuel production represents a critical research and commercial frontier, directly supporting the transition to a sustainable energy system. Engineering efforts focus on developing robust microbial cell factories that can efficiently convert various feedstocks into advanced biofuels.

Engineering Microbial Chassis for Biofuel Production

Different microorganisms are engineered as platforms, or "chassis," for biofuel production, each with distinct advantages.

- Escherichia coli: A versatile and genetically tractable host, E. coli has been engineered for the production of a wide range of biofuels, including ethanol, butanol, and fatty acid-derived alkanes [22]. Its well-understood physiology and the availability of extensive genetic tools make it a popular choice for pathway prototyping and optimization [23] [22].

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae: This yeast is a traditional workhorse for ethanol production. Metabolic engineering has expanded its substrate range to include pentose sugars like xylose from lignocellulosic biomass, with engineered strains achieving ∼85% conversion efficiency [1]. It is also engineered for the production of more advanced biofuels like isobutanol [22].

- Clostridium spp.: Certain species of Clostridium are natural solvent producers and are central to acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation. Metabolic engineering has been employed to enhance butanol yield and tolerance, with some strains showing a 3-fold increase in butanol yield [1] [22].

- Cyanobacteria (e.g., Synechocystis spp.): These photosynthetic organisms are engineered to directly convert carbon dioxide and solar energy into biofuels and chemicals, such as ethanol, isobutanol, and alkanes, bypassing the need for biomass feedstocks [23] [22].

- Oleaginous Yeasts and Microalgae: Organisms like Yarrowia lipolytica and various microalgae are engineered to accumulate high levels of lipids (TAGs), which can then be converted into biodiesel. Some processes have achieved up to 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency from lipids [1].

Core Metabolic Engineering Strategies and Protocols

The engineering of these microbial chassis involves a suite of sophisticated molecular biology techniques aimed at redirecting cellular metabolism toward the desired biofuel.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Metabolic Engineering | Specific Example in Biofuel Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise, targeted genome editing (gene knock-outs, knock-ins, repression). | Used to knockout the AGP gene in microalga Tetraselmis sp. to enhance lipid productivity [22]. |

| DNA Sequencing & Synthesis | Facilitates genome analysis and synthetic gene/pathway construction. | Falling costs accelerate the design and assembly of heterologous pathways for isoprenoid biofuels [27]. |

| RNA-guided Cas9 variants (dCas9) | Allows for fine-tuned transcriptional regulation without altering DNA sequence. | Used in E. coli to dynamically repress competing pathways, directing flux toward free fatty acid production [22]. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | Amplifies DNA fragments for cloning, diagnostic analysis, and pathway assembly. | Used in Real-Time PCR tests for monitoring gene expression changes in engineered pathways [27]. |

| Synthetic Oligonucleotides | Building blocks for gene synthesis and primers for site-directed mutagenesis. | Essential for creating mutagenic libraries of promoter or enzyme-coding sequences to optimize pathway flux [27]. |

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for developing a biofuel-producing microorganism, integrating the tools and strategies listed above.

The core methodologies employed in this workflow include:

- Pathway Engineering and Gene Overexpression: This involves introducing heterologous genes or overexpressing native ones to create or enhance a biosynthetic route. For example, introducing the Clostridium butanol synthesis pathway into E. coli enables it to produce butanol [22]. A key protocol is the assembly of multi-gene pathways using standard techniques like Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate cloning into a plasmid vector, followed by transformation into the host.

- Deletion of Competing Pathways: To maximize carbon and energy flux toward the desired biofuel, genes involved in competing metabolic pathways are knocked out. For instance, deleting genes for mixed-acid fermentation in E. coli can improve ethanol or butanol yields [22]. This is routinely achieved using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing.

- Enzyme Engineering: Native or heterologous enzymes in the pathway may have low activity, poor stability, or undesirable regulation. Directed evolution or rational design is used to create mutant enzyme libraries with improved properties, which are then screened for enhanced performance [22].

- Cofactor Engineering: Biofuel pathways often require specific redox cofactors (NADH/NADPH). Engineering the balance and supply of these cofactors is crucial for high yield. This can involve switching the cofactor specificity of a key enzyme or modulating the expression of genes in central carbon metabolism [22].

- Tolerance Engineering: Biofuels are often toxic to the production host at high concentrations. Strategies like Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE), where microbes are gradually exposed to increasing levels of the biofuel, can select for more robust phenotypes. Genomic analysis of evolved strains then identifies the mutations responsible for tolerance, which can be engineered into production strains [23] [22].

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

The field of metabolic engineering is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends poised to reshape biofuel production and the broader market.

- Shift Towards Synthetic Consortia and Co-cultures: Instead of engineering a single super-strain, researchers are designing synthetic microbial consortia where different engineered microbes work together. Recent studies demonstrate that co-culture systems can improve biosynthesis efficiency by 28% for high-demand biochemicals by distributing metabolic tasks and mitigating toxicity [20].

- Rise of Cell-Free Metabolic Engineering: This approach utilizes purified enzymatic systems rather than living cells, providing unprecedented flexibility in pathway design and avoiding complications of cellular toxicity and complex regulation. It is particularly promising for rapid prototyping of new pathways and producing toxic compounds [20].

- AI-Driven Strain Optimization: Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to analyze complex biological data, predict optimal genetic modifications, and design novel enzymes. AI accelerates the discovery of new metabolic pathways and the optimization of fermentation processes [21] [27].

- Expansion of Feedstock Utilization: Future research is heavily focused on improving the economic viability of biofuels by enabling the efficient use of non-food, lignocellulosic biomass and industrial waste gases (e.g., CO₂, CO). This involves engineering microbes to better tolerate inhibitors in biomass hydrolysates and to metabolize a wider range of carbon sources [23] [1].

- Integration with Circular Economy Models: Metabolic engineering is increasingly viewed through the lens of the circular economy, focusing on waste recycling and carbon-neutral operations. This includes designing processes that convert agricultural residues, municipal waste, and industrial emissions into valuable biofuels and chemicals [1].

In conclusion, the metabolic engineering market is on a strong growth trajectory, fundamentally driven by the global demand for sustainable solutions. Key industrial players are leveraging advanced genetic tools and strategic partnerships to develop innovative bio-production platforms. In the specific context of biofuel research, continuous advancements in pathway engineering, CRISPR-based genome editing, and AI-driven design are systematically addressing the challenges of yield, titer, and production cost, paving the way for next-generation biofuels to play a central role in the future renewable energy landscape.

Engineering the Biofuel Assembly Line: Tools, Hosts, and Pathway Design

The global demand for sustainable energy has catalyzed intense research into biofuel production, with metabolic engineering emerging as a pivotal discipline for optimizing microbial biofuel pathways [3]. Traditional metabolic engineering approaches, while useful, often faced limitations in speed, scale, and precision when reprogramming cellular factories [28] [29]. The advent of advanced genetic toolkits, specifically the CRISPR/Cas9 system and Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE), has ushered in a new era, enabling unprecedented control over complex metabolic networks in model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [3] [30]. These tools facilitate the systematic rewiring of central metabolism to enhance the production of advanced biofuels—such as n-butanol, iso-butanol, and fatty acid-derived compounds—addressing critical challenges of yield, titer, and productivity that are essential for commercial viability [3] [28]. This technical guide details the core mechanisms, methodologies, and synergistic application of CRISPR/Cas9 and MAGE within the context of biofuel research.

CRISPR/Cas9 System

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system is an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that has been repurposed for precise genome editing. The most widely used variant, CRISPR/Cas9, employs a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA sequence, resulting in a double-strand break (DSB) [30] [29]. The cell repairs this break primarily through two pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair process that often introduces insertions or deletions (indels), leading to gene knockouts.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a donor DNA template to incorporate specific mutations, insertions, or gene replacements [29].

The system's versatility has been expanded through protein engineering, creating derivative tools such as:

- CRISPR interference (CRISPRi): Utilizing a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) to block transcription without cleaving DNA, enabling targeted gene repression [30].

- CRISPR activation (CRISPRa): Employing dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators to enhance gene expression [30].

- Base and Prime Editors: Engineered Cas proteins that enable precise nucleotide changes without creating DSBs, offering higher specificity and reduced off-target effects [29].

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE)

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) is a high-throughput genome editing technology that utilizes synthetic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides (oligos) to introduce targeted modifications across multiple genomic loci simultaneously [29]. This method leverages the endogenous λ Red recombinase system in E. coli to incorporate these oligos into the chromosome during DNA replication. A key feature of MAGE is the temporary suppression of the host's mismatch repair (MMR) system (e.g., by knocking out mutS), which significantly enhances the efficiency of oligo incorporation by preventing the cell from recognizing and correcting the introduced changes [29]. The process is cyclical, allowing for iterative rounds of engineering to accumulate desired mutations rapidly across a population, facilitating the exploration of vast combinatorial genetic landscapes.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 and MAGE

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics of both technologies for easy comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 and MAGE Technologies

| Feature | CRISPR/Cas9 | MAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | RNA-guided DNA cleavage by Cas nuclease [30] [29] | ssDNA oligo recombineering using λ Red system [29] |

| Primary Editing Outcome | Knockouts (via NHEJ), precise edits (via HDR) [29] | Primarily point mutations, small insertions/deletions [29] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (using multiple sgRNAs) [30] [29] | Very High (dozens of oligos per cycle) [29] |

| Key Advantage | High precision, versatility (knockout/activation/repression) [3] [30] | Rapid, scalable, combinatorial library generation [29] |

| Primary Limitation | Can be cytotoxic with multiple DSBs; lower HDR efficiency than NHEJ [29] | Requires MMR suppression, leading to potential background mutations [29] |

| Optimal Application | Pathway gene knock-ins/knock-outs, transcriptional regulation [3] [30] | Optimizing enzyme coding sequences, fine-tuning regulatory regions [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Biofuel Pathway Engineering

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout for Toxin Tolerance

Enhancing microbial tolerance to inhibitors found in lignocellulosic hydrolysates, such as furfural, is critical for efficient biofuel production [3]. The following protocol outlines steps to knockout the yqhD gene in E. coli, which depletes NADPH upon furfural exposure, thereby improving strain survival [3].

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Knockout

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Plasmid | Constitutively expresses the Cas9 nuclease. |

| sgRNA Expression Cassette | Expresses sgRNA targeting the yqhD gene. |

| Donor DNA Template (Optional) | For HDR-mediated precise edits; not always required for knockout via NHEJ. |

| Electrocompetent E. coli Cells | Host strain prepared for transformation via electroporation. |

| LB Agar Plates with Selective Antibiotic | For selection and growth of transformed cells. |

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design a 20-nucleotide sgRNA sequence complementary to the early exonic region of the yqhD gene. Ensure the target site is adjacent to a PAM (5'-NGG-3') sequence [30].

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequence into a CRISPR plasmid under a suitable promoter. This plasmid should also carry the Cas9 gene and a selectable marker (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene).

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into electrocompetent E. coli cells via electroporation.

- Selection and Screening: Plate the transformed cells on LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotic. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Mutant Verification: Screen individual colonies for the yqhD knockout. This can be done via:

- PCR and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): Amplify the target region and digest with a restriction enzyme. An altered banding pattern may indicate a successful edit.

- DNA Sequencing: Sanger sequence the PCR-amplified target locus to confirm the presence of indels.

- Tolerance Assay: Grow the verified knockout strain and a wild-type control in medium containing a sub-lethal concentration of furfural (e.g., 1.5 g/L). Monitor growth (OD600) over 24 hours to confirm enhanced tolerance [3].

MAGE for Optimizing Enzyme Expression in a Biofuel Pathway

MAGE is ideal for optimizing codons or regulatory elements of multiple genes within a biosynthetic pathway, such as the n-butanol pathway in E. coli.

Table 3: Key Reagents for MAGE

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| ssDNA Oligonucleotides | 90-mer oligos homologous to the target site with the desired mutation(s). |

| MMR-Deficient E. coli Strain | Host strain (e.g., ΔmutS) to enhance recombination efficiency [29]. |

| Plasmid expressing λ Red Beta Protein | Provides the recombinase function essential for oligo incorporation. |

| Temperature-Controlled Shaker | For precise induction of the λ Red system. |

| Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth and Agar | Standard media for cell growth and recovery. |

Procedure:

- Oligo Design: Design ~90-nucleotide ssDNA oligos for each target gene (e.g., thl, hbd, crt, bcd in the n-butanol pathway). The oligo should be homologous to the lagging strand during DNA replication and contain the desired silent mutation(s) to optimize codon usage or alter Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strength.

- Strain Preparation: Grow an MMR-deficient E. coli strain harboring a plasmid with the λ Red genes (gam, exo, beta) under a temperature-inducible promoter (e.g., λ pL) to an OD600 of ~0.5.

- λ Red Induction: Shift the culture to 42°C for 15 minutes to induce the expression of λ Red proteins.

- Cell Washing and Electroporation: Make cells electrocompetent by chilling and washing repeatedly with ice-cold water. Electroporate a pool of all designed ssDNA oligos (each at ~100 nM final concentration) into the cells.

- Outgrowth and Cycling: Allow cells to recover in SOC medium at 34°C for 2-3 hours. This completes one MAGE cycle. A small aliquot can be plated to check editing efficiency.

- Iterative Cycling: Use a small portion of the recovered culture to inoculate fresh medium and repeat steps 2-5 for multiple (e.g., 10-15) cycles to accumulate mutations across the population.