Mastering the Equilibrium: Strategies for Balancing Growth and Production in Microbial Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing the critical balance between cellular growth and fatty acid production in engineered systems.

Mastering the Equilibrium: Strategies for Balancing Growth and Production in Microbial Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing the critical balance between cellular growth and fatty acid production in engineered systems. We explore foundational metabolic pathways and competing objectives, detail methodological approaches for pathway engineering and dynamic regulation, address common bottlenecks and optimization strategies, and compare validation techniques across different host platforms. The synthesis offers a roadmap for optimizing yield, titer, and productivity in biomedical and industrial applications.

The Metabolic Crossroads: Understanding the Fundamental Trade-off Between Biomass and Fatty Acid Yield

Troubleshooting & FAQ Guide: Balancing Flux for Fatty Acid Production

Thesis Context: This technical support center provides guidance for researchers working to optimize the balance between microbial growth (biomass yield) and product titers in metabolic engineering efforts focused on fatty acid biosynthesis, where acetyl-CoA is the critical precursor.

FAQ 1: My engineered E. coli strain shows poor growth and low fatty acid titer. How can I diagnose if acetyl-CoA availability is the bottleneck?

Answer: Poor growth with low production often indicates a "pull" conflict, where the engineered pathway drains acetyl-CoA from the TCA cycle, crippling energy generation. To diagnose:

- Measure Key Metabolites: Use LC-MS to quantify intracellular acetyl-CoA, citrate, and malonyl-CoA levels. Compare to your control strain.

- Check Growth Rate vs. Induction: Delay induction of your fatty acid synthase (FAS) system until mid-log phase. If growth recovers but production remains low, the issue is likely insufficient acetyl-CoA for production post-induction.

- Test Pyruvate Supplementation: Add sodium pyruvate (5-10 mM) to the medium. If both growth and production improve, it confirms a bottleneck in converting pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (e.g., via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex).

FAQ 2: I've overexpressed an acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) to boost flux, but my strain's yield is unchanged. What are common failure points?

Answer: Simply overexpressing a single enzyme often fails due to lack of cofactors or downstream bottlenecks.

- ATP Limitation: ACS requires ATP. High activity can deplete ATP pools, stalling growth. Check dissolved oxygen and consider a fed-batch strategy.

- Acetate Accumulation: ACS converts acetate to acetyl-CoA. If your strain also produces acetate (a common overflow metabolite), you create a futile cycle. Knock out acetate-producing pathways (e.g., pta-ackA).

- Malonyl-CoA Conversion Limit: The increased acetyl-CoA flux may hit the next bottleneck: conversion to malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). Co-express a functional ACC complex.

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Intracellular Acetyl-CoA Pools

- Method: Metabolite extraction followed by LC-MS/MS.

- Procedure:

- Culture & Quench: Grow cells to target OD600. Rapidly quench 5 mL of culture by injecting into 10 mL of -40°C quenching solution (40:40:20 methanol:acetonitrile:water with 0.1 M formic acid).

- Extraction: Pellet cells at -20°C. Resuspend in 1 mL of 80% methanol (-20°C) with 0.1 µM internal standard (e.g., D4-succinate). Vortex for 30 min at 4°C.

- Clear & Dry: Centrifuge at 16,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Transfer supernatant, evaporate in a speed vacuum, and reconstitute in 100 µL water for LC-MS/MS.

- Analysis: Use a HILIC column. Quantify against a standard curve of pure acetyl-CoA. Normalize to cell dry weight.

FAQ 3: How do I dynamically divert flux from growth (TCA cycle) to production (malonyl-CoA/FAS) at the right time?

Answer: This is the core challenge. Implement genetic/molecular switches.

- Promoter Strategy: Use a growth-phase inducible promoter (e.g., PBAD for arabinose) to activate FAS genes only after sufficient biomass is achieved.

- CRISPRi Tuning: Use a CRISPRi system to repress a key TCA cycle gene (e.g., gltA, citrate synthase) after growth, redirecting acetyl-CoA to production.

- Small Molecule Induction: Use an orthogonal acyl-CoA synthetase/inducer pair (e.g., AcuI with cumate) to trigger FAS expression without interfering with native metabolism.

Key Quantitative Data in Acetyl-CoA Metabolic Engineering

Table 1: Common Strategies to Enhance Acetyl-CoA Supply in Model Microbes

| Strategy | Host Organism | Typical Acetyl-CoA Increase (Fold) | Impact on Fatty Acid Titer | Key Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overexpress pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) | E. coli | 1.5 - 2.5 | Moderate (10-50% increase) | Liu et al., 2020 |

| Express heterologous ATP-neutral PDH bypass | S. cerevisiae | 3.0 - 5.0 | High (2-4x increase) | Kozak et al., 2014 |

| Disrupt competitive pathways (e.g., pta-ackA) | E. coli | 2.0 - 3.0 | Variable; can impair growth | Xu et al., 2021 |

| Overexpress ACS with acetate supplementation | Multiple | 5.0 - 10.0 | Very High, but adds cost | Vuoristo et al., 2015 |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Balanced Growth-Production Scenarios

| Engineering Approach | Final OD600 | Fatty Acid Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g glucose) | Acetyl-CoA Pool Size (nmol/mg DW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type (No FAS overexpression) | 8.5 | <0.1 | - | 15 ± 3 |

| Constitutive FAS Overexpression | 3.2 | 1.5 | 0.05 | 5 ± 1 |

| Inducible FAS + PDH Overexpression | 7.8 | 4.2 | 0.12 | 25 ± 4 |

| Inducible FAS + ACS + pta knockout | 6.5 | 6.8 | 0.18 | 45 ± 7 |

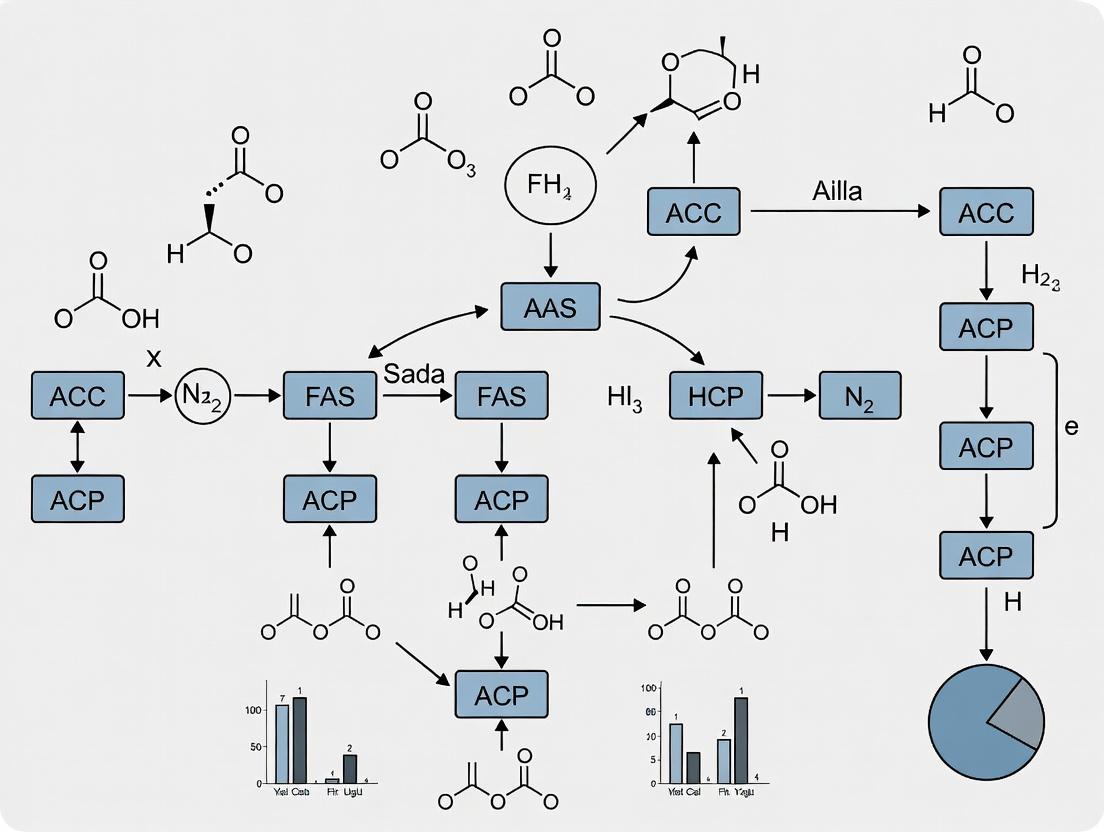

Visualizing Core Pathways and Workflows

Title: Acetyl-CoA as the Central Node Diverting Metabolic Flux

Title: Experimental Workflow for Diagnosing Acetyl-CoA Flux Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Acetyl-CoA/FAS Research |

|---|---|

| Sodium [1-¹³C] or [U-¹³C] Acetate | Isotopic tracer for quantifying acetyl-CoA flux into the TCA cycle vs. malonyl-CoA via metabolomics (flux analysis). |

| Malonyl-CoA (¹³C₃-labeled) | Quantitative standard for LC-MS/MS to accurately measure intracellular malonyl-CoA pools, the direct precursor to FAS. |

| Triacsin C | Small molecule inhibitor of acyl-CoA synthetases. Used experimentally to block fatty acid degradation and recycle pathways, helping to isolate de novo synthesis. |

| Cerulenin | Natural inhibitor of the FabB/FabF condensing enzymes in FAS. Used to inhibit native FAS, allowing study of engineered heterologous pathways in isolation. |

| Anti-Acetyl Lysine Antibody | For detecting global protein acetylation status. Important because acetyl-CoA is also a substrate for protein acetylation, a major competing sink. |

| Pyruvate Dehydrogenase (PDH) Enzyme Activity Assay Kit | Colorimetric kit to measure PDH complex activity directly from cell lysates, confirming if overexpressed enzymes are functional. |

| Custom CRISPRi sgRNA Library | For targeted, tunable repression of competing acetyl-CoA consuming pathways (e.g., gltA, poxB) to dynamically shift flux. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Welcome, Researcher. This support center addresses common experimental challenges in fatty acid biosynthesis studies where lipid overproduction compromises cell proliferation. All content is framed within the thesis: Balancing growth and production in fatty acid biosynthesis research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In my engineered S. cerevisiae strain, I observe a severe growth arrest (extended lag phase and reduced specific growth rate) upon inducing the heterologous fatty acid synthase (FAS) system. What are the primary culprits?

A: Growth arrest upon induction is a classic symptom of the growth-production dilemma. The primary issues, based on current research, are:

- Metabolic Burden & Resource Competition: Heterologous FAS expression diverts acetyl-CoA, ATP, and NADPH from central metabolism (like TCA cycle and amino acid synthesis) needed for growth.

- Lipotoxicity: Accumulation of free fatty acids (FFAs) or intermediate lipids can disrupt membrane integrity, inhibit enzymes, and induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress.

- Feedback Inhibition: Elevated levels of long-chain acyl-CoAs can allosterically inhibit key enzymes like Acc1 (acetyl-CoA carboxylase), further disrupting native metabolism.

Mitigation Protocol: Implement a dynamic induction system. Instead of strong, constitutive promoters, use promoters (e.g., GAL1, MET25) that allow you to separate the growth phase (promoter OFF) from the production phase (promoter ON at mid-log phase). Titrate inducer concentration to find a sub-maximal level that maintains some growth.

Q2: My bacterial culture (E. coli) for free fatty acid (FFA) production shows a significant drop in cell viability (CFU counts) and increased filamentation at high titers. How can I diagnose and fix this?

A: Increased filamentation indicates a direct impairment of cell division machinery, often due to:

- Inhibition of FtsZ Ring Formation: Acyl-ACP or FFA accumulation can inhibit the GTPase activity of FtsZ, preventing proper septum formation.

- Membrane Stress Response Activation: The σ^E and Cpx pathways activated by membrane defects can downregulate cell division genes.

Diagnostic Workflow:

- Stain for Nucleoids (DAPI) and Membrane (FM 4-64). Filamented cells with regularly spaced nucleoids suggest a dedicated division block.

- Perform qRT-PCR on key division genes (ftsZ, ftsA, ftsQ) and stress markers (rpoH, cpxP).

- Co-express an acyl-ACP thioesterase (TesA) to rapidly convert inhibitory acyl-ACP to less toxic FFAs for export.

- Supplement the medium with primrose oil (0.1% v/v) or other unsaturated fatty acids to help maintain membrane fluidity under stress.

Q3: For mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK293) engineered for lipid droplet (LD) accumulation, how can I measure the direct impact of LD load on cell cycle progression?

A: You need to correlate LD content with cell cycle phase at the single-cell level. Detailed Protocol:

- Induce Lipid Production: Treat cells with your inducer (e.g., oleate/palmitate mixture, gene switch) for 24-48h.

- Stain Lipid Droplets: Use BODIPY 493/503 or Nile Red in live cells.

- Stain DNA for Cell Cycle: Fix and permeabilize cells, then stain with Propidium Iodide (PI) or DAPI.

- Perform Flow Cytometry: Use a high-throughput analyzer (e.g., ImageStream) that captures:

- Fluorescence Intensity (BODIPY): Quantifies neutral lipid content per cell.

- DNA Content (PI): Assigns G1, S, G2/M phase.

- Gate Analysis: Gate cells based on high vs. low BODIPY signal. Compare the cell cycle distribution (histogram of PI signal) between these two populations. High-LD cells often show a significant accumulation in G1 phase.

Table 1: Impact of Lipid Overproduction on Cellular Parameters in Model Organisms

| Organism / Strain | Intervention (Induced Gene/Pathway) | Lipid Titer Increase | Specific Growth Rate Reduction (%) | Cell Division Defect Observed | Key Molecular Insight | Citation (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli ML103 | 'TesA (Thioesterase) overexpression | 8.5-fold (FFA) | ~75% | Cell filamentation | Acyl-ACP accumulation inhibits FtsZ polymerization | (J. Bacteriol, 2022) |

| S. cerevisiae FY23 | Heterologous type I FAS from Y. lipolytica | 6.2-fold (TAG) | ~60% | Extended G1/S phase | CDK activity inhibition; SBF/MBF transcription factor mislocalization | (Metab. Eng., 2023) |

| HEK293 Cells | DGAT1 & DGAT2 co-overexpression | 4-fold (LD count) | ~40% (Proliferation) | G1/S arrest | p27Kip1 upregulation; Rb hypo-phosphorylation | (Cell Rep., 2023) |

| Y. lipolytica PO1f | Push-Pull-Block strategy (ACC, FAS, DGA1) | 12-fold (Lipids) | ~25% (Managed) | Mild elongation | Balanced carbon flux maintained via peroxisomal β-oxidation knockdown | (Nat. Comm., 2024) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Growth-Production Trade-offs

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in This Context |

|---|---|

| BODIPY 493/503 | Neutral lipid-specific fluorescent dye for quantifying lipid droplets via microscopy or flow cytometry. Superior photostability vs. Nile Red. |

| FM 4-64FX | Fixable lipophilic styryl dye for staining and visualizing plasma membrane and endocytic compartments; useful for assessing membrane integrity and division septa. |

| Cerulenin | A natural inhibitor of fungal FAS (FabB/F in bacteria). Used as a control to chemically inhibit de novo fatty acid synthesis and study the effects of lipid depletion. |

| C170 Fatty Acid (Heptadecanoic acid) | Odd-chain fatty acid internal standard. Added to cultures pre-extraction for absolute quantification of FFA/TAG via GC-MS. Not produced by most native systems. |

| CellTrace Violet | Fluorescent cytoplasmic dye for tracking cell proliferation by dilution. Allows correlation of division cycles with lipid content (via BODIPY) in live cells. |

| Antibody: Phospho-Rb (Ser807/811) | Marker for G1/S transition via Western Blot. Hypo-phosphorylation indicates cell cycle arrest in G1, linking lipid stress to cycle machinery. |

| Tunable Fatty Acid Inducer Mix | Defined blend of oleate (C18:1), palmitate (C16:0), and stearate (C18:0) in a BSA-complexed formulation. Allows precise titration of lipid stress. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Title: Dynamic Induction Workflow for Balancing Growth and Lipid Production

Title: Signaling Pathways Linking Lipid Stress to Division Arrest

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Fatty Acid Biosynthesis Experiments

This support center provides targeted guidance for common experimental challenges in studying the regulatory axis of Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC), Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS), and the dual role of malonyl-CoA. The content is framed within the research thesis on Balancing growth and production in fatty acid biosynthesis research.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our cell culture assays show inconsistent malonyl-CoA levels despite using a standard ACC inhibitor (e.g., TOFA). What could be causing this variability? A: Inconsistent malonyl-CoA levels often stem from unaccounted metabolic crosstalk. Malonyl-CoA is not only a precursor for FAS but also a potent inhibitor of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), regulating fatty acid oxidation (FAO). Variability can arise from:

- Cell State Dependence: The balance between biosynthesis and oxidation is highly sensitive to nutrient status (e.g., glucose vs. lipid media).

- Feedback Loops: Inhibition of FAS can lead to upstream accumulation of malonyl-CoA, which may further inhibit ACC phosphorylation.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Standardize Nutrient Conditions: Ensure identical serum starvation/re-feeding protocols pre-experiment.

- Parallel Measurement: Concurrently measure β-oxidation rates (e.g., via ³H-palmitate assay) when quantifying malonyl-CoA.

- Inhibitor Titration: Perform a dose-response curve for TOFA; effects can be biphasic.

- Use an Internal Control: Spike samples with a stable isotope-labeled malonyl-CoA standard (if using LC-MS) to correct for recovery differences.

Q2: When attempting to knock down ACC1 (ACACA) to reduce malonyl-CoA, we observe compensatory upregulation of ACC2 (ACACB) or FASN. How can this be mitigated? A: This is a classic feedback response due to the interconnected regulatory network. The primary signal is often the depletion of malonyl-CoA or downstream lipids.

- Solution - Combinatorial Targeting: Use dual targeting strategies.

- Experimental Protocol:

- siRNA/shRNA Knockdown: Target ACACA (ACC1, cytosolic) with validated sequences.

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Co-treat with a low-dose FAS inhibitor (e.g., C75, Cerulenin) to prevent feedback signaling from unutilized malonyl-CoA.

- Monitor Key Nodes: Confirm target knockdown via qPCR (for ACC1, ACC2, FASN mRNA) and Western blot (for protein). Measure malonyl-CoA levels (see Table 1) to confirm the desired net effect.

- Critical Control: Include a condition with FAS inhibitor alone to distinguish direct effects from compensatory ones.

Q3: Our in vitro ACC activity assay (using [¹⁴C]-bicarbonate) shows high background or low incorporation. What are the potential pitfalls? A: The radiometric ACC assay is sensitive to reaction conditions and substrate purity.

- Troubleshooting Checklist:

- Substrate Stability: Prepare fresh acetyl-CoA and ATP solutions; they degrade upon freeze-thaw.

- Cofactor Integrity: Ensure biotin and MnCl₂ are present and active. Mn²⁺ is preferred over Mg²⁺ for animal ACCs.

- Enzyme Preparation: If using cell lysates, include protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of lysates.

- Background Reduction: Include a "no acetyl-CoA" control to subtract non-specific fixation of [¹⁴C]-bicarbonate.

- Quench Correctly: The reaction must be stopped with concentrated HCl or perchloric acid to release unincorporated [¹⁴C]-CO₂.

Q4: How can we reliably distinguish the "signaling" role of malonyl-CoA from its "precursor" role in experimental models? A: This requires disentangling its metabolic flux from its protein-binding interactions.

- Recommended Experimental Workflow:

- Manipulate Levels: Use ACC inhibitors (TOFA; lowers malonyl-CoA) or FAS inhibitors (C75; raises malonyl-CoA).

- Measure Specific Outcomes:

- Precursor Role: Directly correlate malonyl-CoA levels with de novo palmitate synthesis rates (using ¹³C-glucose or ¹⁴C-acetate tracer).

- Signaling Role: Measure downstream events independent of FAS activity:

- CPT1 Inhibition: Assess β-oxidation rates (via Seahorse analyzer or radiolabeled palmitate).

- Transcriptional Effects: Perform RNA-Seq/qPCR for malonyl-CoA sensitive genes (e.g., FASN, SREBP1c).

- Use a Malonyl-CoA Decoupler: Overexpress a malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MLYCD) in a specific compartment (cytosol vs. mitochondria) to degrade malonyl-CoA without directly affecting ACC or FAS activity. This can isolate signaling effects.

Table 1: Typical Malonyl-CoA Concentrations and Effects Under Different Metabolic States

| Metabolic State / Intervention | Approx. Malonyl-CoA Concentration (nmol/g in liver / nmol/mg protein in cells) | Primary ACC Isoform Affected | Net Effect on Fatty Acid Synthesis | Net Effect on Fatty Acid Oxidation (via CPT1 inhibition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fed / High-Carbohydrate | 15-25 nmol/g (high) | ACC1 (Active, dephosphorylated) | ↑↑↑ | ↑ (Inhibited) |

| Fasted / Starvation | 2-5 nmol/g (low) | ACC2 (Inactive, phosphorylated) | ↓↓↓ | ↓ (Derepressed) |

| ACC Inhibitor (TOFA, 10µM) | ~60% reduction from baseline | ACC1 & ACC2 | ↓↓ | ↓↓ (Derepressed) |

| FAS Inhibitor (C75, 20µM) | ~300% increase from baseline | (ACC allosterically inhibited) | ↓ (Direct inhibition) | ↑↑ (Potently inhibited) |

Table 2: Common Genetic and Pharmacological Modulators of the ACC-FAS Axis

| Target | Reagent/Tool (Example) | Mode of Action | Primary Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | siRNA/shRNA (ACACA/ACACB) | Gene knockdown | Study isoform-specific functions |

| ACC | TOFA (5-(Tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid) | Allosteric inhibitor; promotes polymerization/inactivation | Acute reduction of malonyl-CoA |

| ACC | ND-630 (formerly GS-0976) | Phosphorylation-mimicking inhibitor (clinical stage) | Target ACC in disease models (NAFLD, HCC) |

| FAS | siRNA/shRNA (FASN) | Gene knockdown | Study consequences of loss of synthesis capacity |

| FAS | C75 (α-Methylene-γ-butyrolactone) | Inhibits β-ketoacyl synthase activity | Raise malonyl-CoA; inhibit synthesis; anorectic effects |

| FAS | Cerulenin | Binds and inhibits β-ketoacyl synthase domain | Classical FAS inhibitor; often used in vitro |

| Malonyl-CoA | MLYCD (Malonyl-CoA Decarboxylase) overexpression | Enzymatic degradation of malonyl-CoA | Dissect precursor vs. signaling roles |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measurement of Cellular Malonyl-CoA Levels via LC-MS/MS Principle: Extraction and quantitative analysis of malonyl-CoA using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Method:

- Cell Quenching: Rapidly aspirate medium from cultured cells (6-well plate). Quench metabolism by adding 1 mL of -20°C 80% methanol/water.

- Extraction: Scrape cells on dry ice. Transfer suspension to a pre-chilled microtube. Add 400 µL of cold chloroform. Vortex for 10 min at 4°C.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The upper aqueous phase contains malonyl-CoA.

- Sample Preparation: Transfer aqueous layer to a new tube. Dry completely in a vacuum concentrator. Reconstitute in 50 µL H₂O for LC-MS/MS.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Column: HILIC column (e.g., BEH Amide, 2.1 x 100 mm, 1.7 µm).

- Mobile Phase: A) 10mM Ammonium acetate in water (pH 9.0), B) Acetonitrile. Gradient elution.

- MS: Negative ion mode. MRM transition: malonyl-CoA: 852.1 → 408.9.

- Quantification: Use a standard curve from pure malonyl-CoA (e.g., 1 nM to 10 µM). Normalize to total cellular protein.

Protocol 2: In Vitro ACC Enzyme Activity Assay (Radiometric) Principle: ACC catalyzes: Acetyl-CoA + HCO₃⁻ + ATP → Malonyl-CoA + ADP + Pi. The fixation of ¹⁴C-bicarbonate into acid-stable malonyl-CoA is measured. Method:

- Reaction Mix (100 µL total):

- 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)

- 10 mM Sodium Citrate (allosteric activator)

- 2.5 mM MgCl₂ / 0.5 mM MnCl₂

- 1 mM DTT

- 0.2 mM Acetyl-CoA

- 10 mM ATP

- 20 mM NaH¹⁴CO₃ (0.1 µCi/µL)

- Cell lysate (20-50 µg protein) or purified ACC enzyme.

- Incubation: Run reaction at 37°C for 10-20 min. Perform in triplicate.

- Termination & Detection: Stop reaction with 50 µL of 6M HCl. Dry the entire mixture in a scintillation vial under a heat lamp (90°C, 60 min) to evaporate unincorporated ¹⁴CO₂.

- Scintillation Counting: Add 5 mL scintillation fluid to the vial. Count radioactivity (disintegrations per minute, DPM) in a β-counter.

- Calculation: Activity (nmol/min/mg) = [(DPMsample - DPMblank) / (specific activity of ¹⁴C-bicarbonate)] / (time * protein amount). Include a "no acetyl-CoA" blank.

Diagrams

Title: Malonyl-CoA's Dual Role in Growth vs. Oxidation

Title: Workflow to Dissect Malonyl-CoA Functions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Supplier Examples (for identification) | Function in ACC/FAS Research |

|---|---|---|

| TOFA (5-(Tetradecyloxy)-2-furoic acid) | Cayman Chemical, Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris | Small molecule allosteric inhibitor of ACC; used to acutely lower cellular malonyl-CoA levels. |

| C75 (α-Methylene-γ-butyrolactone) | Cayman Chemical, Sigma-Aldrich | Inhibitor of FAS (β-ketoacyl synthase domain); raises malonyl-CoA and suppresses appetite. |

| [1-¹⁴C]-Acetate / [U-¹³C]-Glucose | American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Cambridge Isotopes | Tracer substrates to measure de novo lipogenesis flux from acetyl-CoA precursors. |

| Anti-Phospho-ACC (Ser79) Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology (#3661) | Detects the inactive, phosphorylated form of ACC (AMPK site); key for signaling studies. |

| Anti-FASN Antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-48357), Cell Signaling Tech (#3180) | Detects FAS protein levels; used to monitor feedback regulation. |

| Malonyl-CoA, Lithium Salt (Pure Standard) | Sigma-Aldrich (M4263) | Critical standard for generating calibration curves in LC-MS/MS or enzymatic assays. |

| Seahorse XF Palmitate-BSA Substrate | Agilent Technologies | Used with Seahorse XF Analyzers to directly measure fatty acid oxidation (FAO) rates in live cells. |

| ACACA and ACACB siRNA Pools | Dharmacon, Santa Cruz Biotechnology | For isoform-specific knockdown of ACC1 (cytosolic) and ACC2 (mitochondrial). |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My in vitro fatty acid synthesis (FAS) reaction stalls prematurely. Acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA substrates are still present. What are the primary energetic causes?

A1: The most likely culprits are depletion of ATP or NADPH. Stalling despite substrate presence indicates a cofactor limitation.

- ATP Depletion: Required for the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). Monitor ATP levels with a coupled assay.

- NADPH Depletion: Required by β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (KR) and enoyl-ACP reductase (ER) steps. A low NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio halts reduction reactions.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Pause the reaction and measure ATP concentration using a luciferase-based assay kit.

- Spectrophotometrically measure absorbance at 340 nm to assess NADPH levels.

- Supplement with a regenerating system: e.g., Phosphocreatine/Creatine Kinase for ATP; glucose-6-phosphate/Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase for NADPH.

Q2: I observe an accumulation of β-hydroxyacyl-ACP intermediates in my yeast culture engineered for fatty acid overproduction. What does this indicate, and how can I rebalance the pathway?

A2: Accumulation of β-hydroxyacyl-ACP suggests a bottleneck at the enoyl-ACP reductase (ER) step or a redox imbalance. This step requires NADPH. The issue may be insufficient NADPH supply relative to the accelerated upstream pathway.

- Solution: Modulate NADPH supply.

- Overexpress NADPH-generating enzymes: Introduce or overexpress genes from the pentose phosphate pathway (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, ZWF1 in yeast).

- Use a redox-cofactor engineering strategy: Express a transhydrogenase to balance NADH/NADPH pools.

- Reduce flux into FAS temporarily by lowering inducer concentration to match the cell's NADPH regeneration capacity.

Q3: When scaling up bacterial fermentation for free fatty acid (FFA) production, yield decreases despite high cell density. Are energetic constraints a probable cause?

A3: Yes. At high cell density, oxygen limitation can cripple oxidative phosphorylation, reducing ATP synthesis. Simultaneously, precursor (acetyl-CoA) generation may shift to less efficient pathways, increasing ATP demand per unit acetyl-CoA. This creates an energy crisis.

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Enhance aeration and mixing to maintain dissolved O₂ >20% saturation.

- Consider an alternative carbon source (e.g., glycerol vs. glucose) that generates acetyl-CoA with lower ATP cost.

- Engineer a metabolic "toggle": Implement dynamic pathway control to divert resources from growth (high ATP demand) to production during stationary phase.

Q4: How can I experimentally quantify the ATP and NADPH consumption per molecule of palmitate synthesized in my recombinant cell line?

A4: Use a metabolomics flux analysis combined with a tracing experiment.

- Detailed Protocol:

- Culture Cells: Grow your recombinant cell line in a defined medium with [1-¹³C]glucose as the sole carbon source.

- Quantify Palmitate: Use GC-MS to measure the rate of palmitate secretion or accumulation (µmol/gDCW/h).

- Measure Metabolite Fluxes: Calculate the flux through the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP) from ¹³CO₂ release data, which directly indicates NADPH production for FAS.

- Calculate ATP Demand: Measure the consumption rates of glucose and oxygen. Using stoichiometric models (e.g., metabolic flux analysis, MFA), estimate the ATP expenditure attributed to FAS, accounting for malonyl-CoA synthesis and other anabolic costs.

- Integrate Data: The ATP/NADPH demand per palmitate is derived from the incremental consumption of these cofactors when FAS is induced versus a baseline condition.

Table 1: Stoichiometric Demands for De Novo Palmitate (C16:0) Synthesis

| Component | Theoretical Stoichiometry (Molecules per Palmitate) | Notes / Experimental Range Observed |

|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | 8 | 1 as primer + 7 as malonyl-CoA. |

| ATP | 7 (theoretical) | For malonyl-CoA synthesis: 1 ATP per malonyl-CoA. Actual cellular demand can be 14-21 due to activation and transport costs. |

| NADPH | 14 | Required for 7 cycles of reduction (KR and ER steps). In vivo measurements often show 12-16 due to pathway inefficiencies. |

| HCO₃⁻ | 7 | Incorporated by Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC). |

Table 2: Common Engineered Strategies to Alleviate Cofactor Limitations

| Strategy | Target Cofactor | Method | Potential Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|

| oxPPP Overexpression | NADPH | Overexpress G6PDH, 6PGDH. | May lower glycolytic flux, reducing acetyl-CoA precursors. |

| Transhydrogenase Expression | NADPH | Express soluble pntAB (E. coli). | Can disrupt native NADH/NADPH balance, affecting growth. |

| ATP Regeneration Modules | ATP | Co-express polyphosphate kinases or glycolysis/oxphos genes. | Increased metabolic burden; heat dissipation challenges. |

| Non-Oxidative Glycolysis (NOG) | ATP | Implement synthetic pathways for acetyl-CoA production with net zero or positive ATP. | Pathway complexity and enzyme compatibility issues. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) Activity Assay with Cofactor Monitoring

Objective: Measure real-time FAS enzyme activity while tracking ATP/NADPH consumption.

Reagents:

- Purified FAS complex (mammalian type I or bacterial type II system).

- Assay Buffer: 100 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 6.8, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA.

- Substrate Master Mix: 100 µM Acetyl-CoA, 200 µM Malonyl-CoA.

- Cofactor Master Mix: 2 mM NADPH, 5 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl₂.

- Regenerating System: 5 mM Phosphocreatine, 10 U/mL Creatine Kinase (ATP); 2 mM Glucose-6-Phosphate, 2 U/mL G6PDH (NADPH).

Method:

- In a spectrophotometer cuvette, mix 500 µL Assay Buffer, 50 µL Substrate Master Mix, 50 µL Cofactor Master Mix, and 20 µL of each Regenerating System component.

- Initiate the reaction by adding 10-50 µg of purified FAS enzyme. Total volume: 700 µL.

- Immediately monitor absorbance at 340 nm (for NADPH oxidation) and 660 nm (for a linked phosphate assay kit to monitor ATP) every 30 seconds for 30 minutes.

- Calculate initial rates. Control reactions should omit either FAS or a key substrate.

Protocol 2: Measuring In Vivo NADPH/NADP⁺ Redox Ratio during FAS Induction

Objective: Snap-freeze cells to capture the instantaneous redox state of the NADP pool upon induction of fatty acid synthesis.

Reagents:

- Quenching Solution: 60% Methanol, 40% 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), pre-chilled to -40°C.

- Extraction Buffer: 100% HPLC-grade Methanol, -40°C.

- LC-MS/MS system with appropriate columns for nucleotide separation.

Method:

- Grow cultures to mid-log phase. Induce FAS (e.g., with IPTG for recombinant systems).

- At precise time points (0, 5, 15, 30 min post-induction), rapidly syringe 1 mL culture into 4 mL of Quenching Solution. Vortex immediately.

- Centrifuge at -9°C, 5000 x g for 5 min. Discard supernatant.

- Extract metabolites from pellet with 500 µL cold Extraction Buffer. Vortex 10 min at 4°C.

- Centrifuge at 15,000 x g, 4°C for 10 min. Collect supernatant for LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Quantify NADPH and NADP⁺ peaks using standard curves. Report as NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: ATP & NADPH Flux in Cytosolic Palmitate Synthesis

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Low FAS Yield

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating FAS Energetics

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function in FAS Energetics Research | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| NADPH/NADP⁺ Quantification Kit | Measures absolute concentrations or ratio of this critical redox cofactor in cell lysates. Essential for in vivo flux balance. | Sigma-Aldrich MAK038 (Colorimetric); BioVision K347-100 (Fluorometric). |

| ATP Assay Kit (Luminescence) | Highly sensitive detection of ATP levels in cell cultures or in vitro reactions to diagnose energy limitation. | Promega FF2000; Abcam ab83355. |

| Recombinant FAS Enzyme (Human or Yeast) | For controlled in vitro studies of kinetics and cofactor requirements without cellular complexity. | Sino Biological 10729-H07B (Human FASN); homemade purification from engineered yeast. |

| [1-¹³C] or [U-¹³C] Glucose | Tracer for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) to quantify flux through oxPPP, glycolysis, and TCA cycle, informing on NADPH & ATP production. | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories CLM-1396; CLM-1396. |

| Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC) Inhibitor | Tool compound to block malonyl-CoA synthesis, helping to study the system's response to halted ATP consumption at this step. | TOFA (AB142085); Soraphen A (ab145865). |

| Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PDH) | Enzyme used to create NADPH-regenerating systems in in vitro assays or to test supplementation strategies. | Sigma-Aldrich G6378. |

| Phosphocreatine / Creatine Kinase | Enzymatic ATP-regenerating system for maintaining constant [ATP] in in vitro FAS assays. | Sigma-Aldrich 2387/ C3755. |

Transcriptional Regulators and Feedback Inhibition Mechanisms

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Issue Category 1: Unproductive Strains & Low Yield

- Q: My engineered microbial strain shows poor growth and negligible fatty acid (FA) production. What is the primary regulatory culprit?

- A: This is a classic symptom of unmodulated transcriptional repression. The key transcriptional regulator FadR (in E. coli) or its homologs likely remain active, repressing genes for FA biosynthesis (fab genes) while activating those for β-oxidation. Simultaneously, overproduction may trigger feedback inhibition of key enzymes like AccABCD (acetyl-CoA carboxylase). First, check your genetic modifications to ensure constitutive fadR knockout or use of a promoter decoy system.

- Q: After knocking out a transcriptional repressor, I see improved growth but FA titer plateaus early. Why?

- A: You have likely relieved growth-linked repression but are now encountering potent end-product feedback inhibition. Free fatty acids (FFAs) or acyl-ACPs directly allosterically inhibit enzymes such as FabI (enoyl-ACP reductase) and AccABCD. Implement one of the following:

- Regular extraction: Use in situ extraction resins (e.g., Amberlite XAD) or two-phase fermentation.

- Engineered export: Overproduce native efflux pumps or heterologous transporters.

- Immediate conversion: Channel FFAs directly into less-toxic products like fatty acyl esters or alcohols.

- A: You have likely relieved growth-linked repression but are now encountering potent end-product feedback inhibition. Free fatty acids (FFAs) or acyl-ACPs directly allosterically inhibit enzymes such as FabI (enoyl-ACP reductase) and AccABCD. Implement one of the following:

Issue Category 2: Dynamic Regulation & Sensing

- Q: How can I verify that my intervention effectively disrupted the feedback loop between acyl-ACP and the transcriptional regulator?

- A: Perform a Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using a tagged version of the regulator (e.g., FadR-FLAG). Compare binding at target promoters (e.g., fabA promoter) in wild-type vs. your mutant strain under both FA-starved and FA-rich conditions. Reduced binding in the mutant confirms disrupted sensing.

- Q: My dynamic sensor system for acyl-CoA levels is not producing the expected fluorescent output. How do I troubleshoot?

- A:

- Check sensor specificity: Confirm your biosensor is specific for the acyl-CoA chain length you are producing. C12-CoA sensors may not respond to C16-CoA.

- Calibrate in vivo: Create a calibration curve by supplementing known amounts of the specific acyl-CoA precursor and measuring fluorescence over time.

- Test promoter strength: The output promoter driving the reporter must have a dynamic range suitable for the expected intracellular ligand concentration.

- A:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ChIP-qPCR to Assess Transcriptional Regulator Binding Objective: Quantify in vivo binding of a transcriptional regulator (e.g., FadR) to target DNA sequences under different metabolic states.

- Culture & Crosslinking: Grow WT and engineered strains to mid-log phase. Add 1% formaldehyde for 15 min to crosslink proteins to DNA. Quench with 125mM glycine.

- Cell Lysis & Sonication: Lyse cells via lysozyme/sonication. Sonicate to shear DNA to 200-500 bp fragments. Confirm fragment size by agarose gel.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate lysate with magnetic beads conjugated to an antibody against your regulator's tag (e.g., anti-FLAG). Use IgG beads as negative control.

- Wash, Elution, & Reverse Crosslinks: Wash beads stringently. Elute complexes and reverse crosslinks at 65°C overnight.

- DNA Purification & qPCR: Purify DNA. Perform qPCR using primers for the target promoter region and a control, non-target genomic region. Calculate % input and fold enrichment.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Feedback Inhibition Assay for Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (AccABCD) Objective: Measure direct inhibition of Acc activity by increasing concentrations of acyl-ACP.

- Enzyme Preparation: Purify recombinant AccABCD complex or use clarified cell lysate from an overexpressing strain.

- Reaction Setup: In a 96-well plate, assemble reactions containing: 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 10 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 µM acetyl-CoA, 10 mM NaHCO3, 0.1 mg/ml BSA.

- Inhibitor Titration: Add purified acyl-ACP (C16:0-ACP) to final concentrations of 0, 2, 5, 10, 20 µM. Pre-incubate with enzyme for 5 min.

- Kinetic Measurement: Start reaction by adding NaH¹⁴CO₃ (or use a coupled NADPH depletion assay). Monitor consumption of substrate/product formation spectrophotometrically or via scintillation counting for 10-20 min.

- Data Analysis: Calculate initial velocities. Plot activity (%) vs. [acyl-ACP] to determine IC₅₀.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Transcriptional Regulators in Model Organisms

| Organism | Regulator | Primary Ligand/Signal | Target Process | Effect on FA Biosynthesis Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | FadR | Long-chain acyl-CoA | Repression/Activation | Represses fab genes. Relief increases yield. |

| B. subtilis | FapR | Malonyl-CoA | Repression | Represses fab genes. Low malonyl-CoA relieves repression. |

| S. cerevisiae | Opi1 | PA (Phosphatidic acid) | Repression | Represses INO1 & FA genes. Relief increases flux. |

| M. circinelloides | - | Malonyl-CoA / Citrate | Activation | Binds FAS promoter; sensing enhances lipid accumulation. |

Table 2: Feedback Inhibition Points in Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

| Enzyme (Complex) | Inhibitor | Approximate IC₅₀ (µM)* | Bypass/Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| AccABCD | Palmitoyl-ACP | 5 - 10 µM | Express feedback-resistant acc mutants (e.g., D35A). |

| FabI (T. maritima) | Palmitoyl-ACP | ~2 µM | Use feedback-resistant FabI homolog (e.g., from B. subtilis). |

| FabH (β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III) | Long-chain acyl-ACP | 10 - 20 µM | Knock out and rely on FabF/B for initiation. |

*IC₅₀ values are organism- and condition-dependent. Values represent typical ranges from literature.

Mandatory Visualizations

Title: Dual-Layer Feedback Inhibition in Fatty Acid Synthesis

Title: Iterative Research Workflow for Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic Beads | For immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged transcriptional regulators in ChIP assays. |

| C16:0-ACP (E. coli) | Pure acyl-ACP substrate used for in vitro feedback inhibition assays on AccABCD or FabI. |

| Amberlite XAD-4 Resin | Hydrophobic resin for in situ removal of free fatty acids, relieving toxicity & feedback inhibition. |

| Malonyl-CoA Biosensor Kit | Live-cell reporter system to monitor real-time changes in cytoplasmic malonyl-CoA pools. |

| Feedback-resistant acc Mutant Plasmid | Expression vector for acetyl-CoA carboxylase with point mutations (e.g., D35A) reducing sensitivity to acyl-ACP. |

| Acyl-CoA Synthetase Inhibitor (Triacsin C) | Chemical tool to probe effects of accumulating intracellular free fatty acids vs. acyl-CoAs. |

Engineering the Balance: Methodologies for Decoupling and Optimizing Fatty Acid Flux

Promoter Engineering and Synthetic Genetic Circuits for Dynamic Control

This technical support center is designed for researchers implementing promoter engineering and synthetic genetic circuits to dynamically balance growth and production in microbial fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB). The guides address common experimental pitfalls specific to this context.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My inducible promoter system shows high basal expression of the FAB enzymes even in the "OFF" state, causing growth retardation. How can I reduce leakiness? A: High basal expression is common. Solutions include:

- Promoter Tuning: Incorporate synthetic operator sites with tighter repressor binding (e.g., engineered LacI or TetR variants).

- Genetic Insulation: Flank the promoter with transcriptional terminators upstream to prevent read-through from genomic context.

- Circuit Layering: Use a NOT gate or repression cascade to sharpen the response. See Protocol 1 for a leak-reduction workflow.

Q2: The dynamic control circuit successfully shuts down FAB enzyme expression, but cell growth does not recover as expected. What could be happening? A: This indicates potential metabolic burden or toxicity.

- Check Metabolic Drain: Overexpression of FAB enzymes, even for a short time, may deplete acetyl-CoA or ATP pools. Monitor key metabolites (see Table 1).

- Check for Intermediate Toxicity: Accumulation of fatty acids or intermediates (e.g., acyl-ACPs) can inhibit growth. Consider introducing a non-toxic storage product (e.g., triacylglycerol) sink.

- Tune Induction Timing: Initiate FAB enzyme expression later in growth phase (higher cell density) to separate growth and production phases more effectively.

Q3: My logic gate circuit (AND gate) for dual-input control of FAB shows unstable output and low dynamic range. How can I improve it? A: Unstable logic gates often suffer from imbalance in component expression.

- RBS Optimization: Use computational tools (e.g., RBS Calculator) to fine-tune the translation initiation rates of all transcriptional regulators in the circuit.

- Promoter Matching: Ensure the promoters driving regulator expression are of appropriate strength relative to each other. Avoid using identical promoters for different parts to prevent homologous recombination.

- Implement Positive Feedback: Carefully introduce a tuned positive feedback loop on the output regulator to sharpen the ON state. See Protocol 2.

Q4: When scaling my dynamic FAB control system from a microplate to a bioreactor, the production yield collapses. What scale-up factors are critical? A: Scale-up failure often relates to inadequate control of induction parameters.

- Inducer Diffusion: Ensure rapid and uniform mixing of the chemical inducer. Consider switching to an inducer with better diffusion properties or using a gaseous inducer (e.g., aTc vs. IPTG).

- Oxygen Sensitivity: Many synthetic genetic parts are oxygen-sensitive. Monitor and control dissolved oxygen tightly, as it differs greatly from shake flasks.

- Cell Density Effect: Autoinducer-based quorum sensing circuits are highly density-dependent. Re-calibrate the cell density threshold for induction in the bioreactor.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reducing Promoter Leakiness via Operator Site Engineering

Objective: Modify a core inducible promoter (e.g., Plac) to minimize basal expression of an FAB enzyme (e.g., fabZ).

- Design: Use mutagenic PCR to introduce point mutations in the -10 and -35 regions or to insert additional/stronger repressor-binding operators.

- Library Construction: Clone the mutated promoter variants upstream of a weak RBS and a reporter gene (e.g., gfpmut3) in a medium-copy plasmid.

- Screening: Transform library into production host. Culture in minimal media +/- inducer. Use flow cytometry to screen for variants with the highest ON/OFF ratio (fluorescence).

- Validation: Clone the top 3-5 promoter variants driving your FAB gene. Measure basal and induced expression via qRT-PCR and correlate with growth (OD600) and fatty acid titer.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Tunable Positive Feedback Loop for Circuit Output Sharpening

Objective: Add a feedback loop to an existing FAB repression circuit to improve switching dynamics.

- Circuit Design: Design a construct where the output transcriptional activator (e.g., AraC variant) of your circuit also activates its own expression from a separate, weaker promoter (Pfeedback).

- Tuning Element: Place the feedback promoter (Pfeedback) under the control of a library of RBSs with varying strengths.

- Assembly: Assemble the circuit using Gibson Assembly. The main output promoter (Pout) drives the FAB gene cluster.

- Characterization: Transform individual RBS variants. Characterize the response curve to input signal. Measure the ON/OFF output ratio and the transition steepness. Select the variant that provides sharp switching without causing hysteresis or instability.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Metabolite Pools to Monitor During Dynamic FAB Control

| Metabolite | Target Pool Size in Growth Phase (nmol/OD600) | Significant Deviation Indicative Of | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | 15-25 | Depletion → Impaired TCA cycle & growth | Enzymatic assay / LC-MS |

| Malonyl-CoA | 0.5-2.0 | Accumulation → Poor FabH/D activity; Depletion → FabB/D overload | LC-MS |

| ATP | 8-12 | Sustained depletion → Metabolic burden | Bioluminescence assay |

| NADPH | 4-6 | Depletion → Redox stress, limits FA elongation | Enzymatic cycling assay |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Common Inducible Systems for FAB Control

| System | Inducer | Typical ON/OFF Ratio | Induction Kinetics | Key Drawback for FAB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plac/LacI | IPTG | 50-200 | Fast (minutes) | High basal expression; Carbon catabolite repression |

| Ptet/TetR | aTc | 500-1000 | Moderate (hours) | Slow diffusion at high cell density; Cost |

| Para/AraC | L-Arabinose | 100-300 | Fast (minutes) | Metabolized by host, causing non-linear response |

| Quorum Sensing (e.g., LuxR/LuxI) | AHL (Autoinducer) | 20-100 | Cell-density dependent | Poorly defined in bioreactors; Cross-talk |

Mandatory Visualization

Diagram 1: Logic of dynamic FAB control circuits.

Diagram 2: Workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing circuits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Dynamic FAB Circuit Construction & Testing

| Item | Function | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Error-free amplification of promoter/gene parts for assembly. | Q5 Hot Start Polymerase (NEB M0493) |

| Modular Cloning Toolkit (e.g., MoClo) | Standardized assembly of multiple genetic parts (promoters, RBS, genes, terminators). | Golden Gate Assembly Kit (BsaI-HFv2, NEB) |

| Broad-Host-Range Expression Vector | Maintains circuit in production hosts (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas). | pSEVA series vectors (SEVA 231, 331) |

| Chemical Inducers (Analogs) | Tight, non-metabolizable control of inducible systems. | IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside), aTc (Anhydrotetracycline) |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Rapid, high-throughput screening of promoter activity and circuit logic. | sfGFP (superfolder GFP), mScarlet-I |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Standards | Quantification of fatty acid production profile via GC-MS. | 37 Component FAME Mix (Supelco 47885-U) |

| NADPH/NADH Quantification Kit | Monitor redox cofactor pools critical for FAB enzyme function. | NADP/NADPH-Glo Assay (Promega G9081) |

| Acetyl-CoA Assay Kit | Direct measurement of central metabolite precursor pool. | Acetyl-CoA Assay Kit (Fluorometric) (Abcam ab87546) |

CRISPRi/a and sRNA Strategies for Fine-Tuning Competing Pathway Expression

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My CRISPRi knockdown of the TCA cycle gene sucB shows no growth phenotype but fatty acid titer also did not improve. What could be wrong? A: This is a common issue indicating insufficient knockdown. First, verify dCas9 expression via Western blot. Ensure your sgRNA is designed with a GN19NGG PAM sequence and targets the non-template strand within -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS. Check for sgRNA promoter strength (we recommend a strong, constitutive promoter like J23119). Quantify knockdown efficiency using RT-qPCR. If efficiency is <70%, consider using a second, tandem sgRNA expression construct. Also, confirm your growth medium—residual acetate or fatty acids can mask expected metabolic shifts.

Q2: I am using an sRNA (MicC scaffold) to repress fabZ. My cell growth is severely inhibited, contrary to the expected mild tuning effect. How should I proceed? A: Severe growth inhibition suggests off-target effects or excessive repression. Perform the following troubleshooting steps:

- Dose Control: Titrate the expression of the sRNA using a tunable promoter (e.g., tetO or araBAD) instead of a strong constitutive one.

- Specificity Check: Run a transcriptomic analysis (RNA-seq) to identify off-target gene silencing. Redesign the sRNA seed region if necessary.

- Genetic Control: Express the target fabZ mRNA sequence with silent mutations in the sRNA-binding region from a plasmid. If this reverses the growth defect, the sRNA effect is on-target but too strong.

Q3: When using CRISPRa to overexpress accABCD, I observe metabolic burden and reduced overall protein synthesis. How can I mitigate this? A: Overexpression of multi-subunit complexes is challenging. Implement a balanced activation strategy:

- Use Weaker Activators: Switch from a strong activator like dCas9-VPR to a milder one like dCas9-SunTag-p65.

- Staggered Activation: Employ multiple sgRNAs targeting different positions upstream of the promoter, and test combinations to find the optimal expression window.

- Inducible System: Use a chemically inducible dCas9 (e.g., with a degron or split-intein system) to pulse expression only during production phase.

Q4: My combined CRISPRi (on pfkA) and sRNA (on fadD) strategy leads to rapid genetic instability and loss of the production phenotype in batch culture. How do I stabilize the strain? A: This indicates high selective pressure against your engineered metabolic state.

- Mitigate Stress: Introduce the perturbations gradually. Use inducible promoters for both systems and induce only at the onset of production phase.

- Genetic Stabilization: Move expression constructs to the genome using Tn7 transposition to avoid plasmid loss. Alternatively, implement essential gene complementation (e.g., fabI) on the plasmid harboring the repression tools to maintain selective pressure.

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution: Subject the unstable strain to short-term evolution in selective conditions, then screen for stable, high-producing clones.

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Fine-Tuning Modalities

| Strategy | Typical Repression Range | Typical Activation Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi (dCas9) | 70-95% | N/A | High specificity, multiplexable | Possible residual binding interference |

| CRISPRa (dCas9-activator) | N/A | 5-50x | Targeted, programmable | High metabolic burden, more off-target effects |

| sRNA (e.g., MicC scaffold) | 30-85% | N/A | Fast response, tunable via promoter | Seed region off-targets, requires Hfq |

| Tunable Promoters | 0-100% | 1-100x | Predictable, well-characterized | Limited number, can be large in size |

Table 2: Impact of Competing Pathway Knockdown on Fatty Acid Yield in E. coli

| Target Gene (Pathway) | Modulation Tool | Knockdown Efficiency | Change in Growth Rate | Change in FA Titer | Optimal Production Phase Induction (OD600) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pfkB (Glycolysis) | CRISPRi | 88% | -12% | +45% | 0.6 |

| sucC (TCA Cycle) | sRNA | 73% | -8% | +32% | 0.8 |

| fadD (β-oxidation) | CRISPRi | 95% | -3% | +110% | 0.5 |

| fabZ (FA Synthesis) | sRNA (Tuned) | 52% | -5% | +65% | 1.0 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Multiplexed CRISPRi for Competing Pathways Objective: To simultaneously repress fadD (β-oxidation) and sucB (TCA cycle) to redirect carbon flux toward fatty acid synthesis. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Steps:

- sgRNA Array Construction: Design two sgRNAs targeting the non-template strand of fadD and sucB. Clone them as a tandem array under the control of the J23119 promoter into plasmid pCRISPRi (Addgene #84832) using Golden Gate assembly (BsaI sites).

- Strain Engineering: Transform the pCRISPRi-sgRNA array plasmid into your production E. coli strain harboring a genomically integrated dCas9 expression cassette (under tetO control).

- Induction & Cultivation: Inoculate main culture in M9 minimal media with 2% glucose. At OD600 = 0.5, add 100 ng/mL anhydrotetracycline (aTc) to induce dCas9 expression. Continue cultivation for 16-24h.

- Validation: Harvest cells at OD600 ~2.0. Verify knockdown via RT-qPCR for each target using rpoB as a housekeeping control. Quantify fatty acid titer via GC-MS.

Protocol 2: sRNA-Mediated Fine-Tuning of fabZ Expression Objective: To titrate the expression of fabZ (β-hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase) to balance growth and FA overproduction. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below. Steps:

- sRNA Design: Design a 22-nt target-complementary sequence specific to the RBS/start codon region of fabZ. Clone this into the MicC scaffold of plasmid pSRNA (Addgene #112862) under the control of the araBAD promoter.

- Cultivation with Titration: Transform pSRNA-fabZ into your FA production strain. Grow cultures in LB, then subculture into M9 + 2% glucose with varying concentrations of L-arabinose (0%, 0.0002%, 0.002%, 0.02%, 0.2%) to induce sRNA.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Measure growth (OD600) over 24h. Harvest cells in mid-stationary phase. Correlate arabinose concentration with fabZ mRNA levels (RT-qPCR) and final FA titer (GC-MS) to identify the optimal induction level.

Visualization

Title: Metabolic Flux Balancing for FA Production

Title: Experimental Selection and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPRi/a and sRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Source / Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Plasmid | Constitutively or inducibly expresses catalytically dead Cas9 protein, the core scaffold for CRISPRi/a. | Addgene #44246 (pLOW-dCas9, anhydrotetracycline-inducible) |

| CRISPRi/a sgRNA Cloning Vector | Backbone for expressing single or arrays of sgRNAs under a strong promoter. | Addgene #84832 (pCRISPRi, BsaI Golden Gate sites) |

| sRNA Cloning Plasmid | Vector containing a stable sRNA scaffold (e.g., MicC) for inserting target-specific sequences. | Addgene #112862 (pSRNA, araBAD promoter, AmpR) |

| Tunable Inducer (aTc, Arabinose) | Small molecules to precisely control the timing and level of dCas9 or sRNA expression. | Sigma-Aldrich, Gold Biotechnology |

| dCas9-Activator Fusion Plasmid | Plasmid expressing dCas9 fused to transcriptional activation domains (e.g., VPR, p65). | Addgene #63798 (dCas9-VPR) |

| RT-qPCR Kit for Bacterial mRNA | Validates knockdown/activation efficiency by quantifying target mRNA levels. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 11732020 |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Standard Mix | External standard for calibrating and quantifying fatty acid production via GC-MS. | Sigma-Aldrich, Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix |

| Hfq-Expressing Strain | Essential host strain for experiments using Hfq-dependent sRNA scaffolds (e.g., MicC). | E. coli Hfq-overexpression strains (e.g., BW25113 hfq+) |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My synthesis flux is stalling. The precursor (acetyl-CoA) does not seem to be efficiently channeled to the elongating fatty acid chain. What could be wrong?

- Answer: This is a classic symptom of spatial mislocalization or insufficient precursor pool generation. First, verify the cellular compartmentalization of your system.

- Check 1: Confirm the activity and localization of ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) or acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). In cytosolic fatty acid synthesis, ACLY generates cytosolic acetyl-CoA from mitochondria-derived citrate. Reduced flux often indicates a problem in this initial translocation and conversion step.

- Check 2: Measure the NADPH/NADP+ ratio. Fatty acid elongation is highly NADPH-dependent. A low ratio will stall the reductase steps of FAS.

- Protocol: Subcellular Fractionation & Metabolite Profiling:

- Harvest cells and lyse using a gentle, isotonic homogenization buffer (e.g., 250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

- Perform differential centrifugation: 1,000 x g (nuclei/debris), 10,000 x g (heavy mitochondria), 100,000 x g (microsomes/cytosol).

- Deproteinize fractions using cold methanol/acetonitrile extraction.

- Analyze acetyl-CoA, citrate, and malonyl-CoA levels in each fraction via LC-MS/MS.

- Solution: If ACLY/ACC localization is correct but precursors are low, consider upregulating mitochondrial export (e.g., modulate the citrate carrier) or supplementing with acetate (with CoA and an ATP source) to bypass the citrate shuttle.

FAQ 2: I am trying to divert flux toward a specific, non-standard fatty acid product (e.g., C12:0 for a drug candidate), but yield is poor and I get heterogeneous chain lengths. How can I improve product sink specificity?

- Answer: Poor specificity indicates weak channeling to your engineered sink. You must enhance the spatial and functional coupling between the FAS complex and your terminating thioesterase (TE).

- Check 1: Verify the physical interaction between your engineered TE (e.g., Umbellularia californica FatB for C12) and the FAS core. Use co-immunoprecipitation.

- Check 2: Analyze the kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) of your TE relative to the endogenous ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KAS) that elongates C12-ACP. The TE must outcompete KAS for the C12-ACP substrate.

- Protocol: Competitive Kinetic Assay for Substrate Channeling:

- Purify the FAS multi-enzyme complex and your recombinant TE.

- In a reconstituted system, provide malonyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, NADPH, and ACP.

- Set up reactions with varying molar ratios of TE:FAS (e.g., 0:1, 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1).

- Stop reactions at timed intervals and quantify free fatty acid chain lengths via GC-FID.

- Calculate the efficiency of channeling: (C12 product)/(Total C12+ products) vs. TE:FAS ratio.

- Solution: If competition is weak, consider creating a fusion protein linking the TE directly to the C-terminus of the FAS acyl carrier protein (ACP) or enoyl reductase (ER) domain to force substrate channeling.

FAQ 3: My engineered overproduction system is causing cellular toxicity, halting growth. How can I balance growth and production?

- Answer: Toxicity often arises from depletion of universal precursors (acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, NADPH) or membrane disruption from fatty acid/lipid overload. You need dynamic, temporal control.

- Check 1: Monitor growth (OD600) and production (e.g., fluorescence from a product-linked reporter) in real-time. A sharp dip in growth rate coinciding with induction is a clear sign.

- Check 2: Measure ATP and NADPH levels post-induction. A significant drop indicates resource overdraw.

- Protocol: Inducible Two-Stage Fermentation for Balance:

- Stage 1 (Growth): Grow culture under permissive conditions without FAS pathway induction. Use a carbon source like glycerol that feeds TCA but not overwhelming FAS.

- Stage 2 (Production): At mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6), induce FAS gene expression with a tightly regulated promoter (e.g., arabinose- or rhamnose-inducible).

- Simultaneously, shift carbon source or supplement with precursors (e.g., malonate) to boost the precursor pool specifically for the synthesis phase.

- Solution: Implement a feedback-regulated system. Use a promoter responsive to acyl-ACP levels (a proxy for precursor availability) to dynamically control FAS gene expression, decoupling it from strong constitutive drivers.

Table 1: Key Metabolite Pools in Cytosolic Fatty Acid Synthesis

| Metabolite | Typical Cytosolic Concentration (nmol/mg protein) | Critical Threshold for Flux Maintenance | Primary Source in Cytosol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | 10 - 30 | > 5 | ATP-citrate lyase (from mitochondrial citrate) |

| Malonyl-CoA | 2 - 10 | > 1 | Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC) |

| NADPH | 50 - 100 (ratio > 1) | NADPH/NADP+ > 0.5 | Pentose phosphate pathway, ME1 reaction |

Table 2: Engineered Thioesterase Specificity & Yield

| Thioesterase Source | Preferred Substrate (Acyl-ACP) | Reported C12:0 Yield (% of total FAs) | Notes for Compartmentalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbellularia californica (FATB) | C12:0-ACP, C14:0-ACP | 40-60% | Strong intrinsic specificity; best fused to ACP. |

| Cuphea hookeriana | C8:0-ACP, C10:0-ACP | 70-80% (C8+C10) | Very short-chain; may require KAS inhibition. |

| Engineered E. coli TesA (leaderless) | Mixed chain lengths | <20% (for C12) | Broad specificity; poor for targeted channeling. |

Experimental Protocol: Proximity Ligation Assay for FAS Complex-TE Interaction

Objective: To visually confirm the spatial co-localization of the Fatty Acid Synthase (FAS) complex and an engineered terminating Thioesterase (TE) within cells.

Materials:

- Fixed cells expressing tagged FAS (e.g., FASN-FLAG) and tagged TE (e.g., Myc-UcFatB).

- Duolink PLA probes (anti-FLAG PLUS, anti-Myc MINUS).

- Duolink Detection Reagents (Ligation buffer, Ligation stock, Amplification buffer, Amplification stock, Wash buffers A & B).

- Fluorescence microscope.

Method:

- Seed and transfer cells to chamber slides. Induce expression as required.

- Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min.

- Block with Duolink Blocking Solution for 60 min at 37°C.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (mouse anti-FLAG, rabbit anti-Myc) diluted in antibody diluent overnight at 4°C.

- Wash with Wash Buffer A (2 x 5 min).

- Add PLA probes (anti-mouse PLUS, anti-rabbit MINUS) and incubate for 60 min at 37°C.

- Wash with Wash Buffer A (2 x 5 min).

- Prepare Ligation Solution (Ligation Stock in Ligation Buffer). Add to samples and incubate for 30 min at 37°C.

- Wash with Wash Buffer A (2 x 5 min).

- Prepare Amplification Solution (Amplification Stock in Amplification Buffer). Add to samples and incubate for 100 min at 37°C in the dark.

- Wash with Wash Buffer B (2 x 10 min), then briefly with 0.01x Wash Buffer B.

- Mount slides with Duolink In Situ Mounting Medium with DAPI.

- Image using a fluorescence microscope. PLA signals (red puncta) indicate proximity (<40 nm) between FAS and TE.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Precursor Channeling in Engineered Fatty Acid Synthesis

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Low Synthesis Flux

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Spatio-Temporal Studies |

|---|---|

| Digitonin | A mild, cholesterol-specific detergent used for selective plasma membrane permeabilization to access the cytosolic fraction without disrupting organelles. |

| Anti-HA/FLAG/Myc Magnetic Beads | For rapid immunoprecipitation of tagged FAS or TE proteins to assess protein-protein interactions or complex composition. |

| C13-Glucose & C13-Acetate | Stable isotope tracers for following the flux of carbon through glycolysis, the citrate shuttle, and into fatty acid chains via GC- or LC-MS. |

| Duolink Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) Kit | Detects in situ protein-protein interactions (<40 nm apart) with high specificity, ideal for visualizing FAS-TE channeling. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems (pBAD, rhaBAD) | Allows temporal decoupling of growth (no induction) from production (induced), critical for balancing cellular resources. |

| Acyl-ACP Synthetase (AasS) & Acyl-ACP Standards | Enzymatically generates defined acyl-ACP substrates for in vitro kinetic assays of thioesterase specificity. |

| NADPH/NADP+ Glo Assay | Luminescent-based assay for quantifying the real-time ratio of NADPH to NADP+ in lysates, indicating reductase capacity. |

Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: Our engineered strain for fatty acid biosynthesis (FAB) shows good growth but poor product titer. What could be the issue? A: This is a classic "growth vs. production" imbalance. High growth often drains NADPH and acetyl-CoA pools for biomass, not FAB. Troubleshoot by:

- Measure Intracellular Cofactor Pools: Use enzymatic cycling assays or LC-MS to quantify [NADPH]/[NADP+] ratio during production phase. A low ratio confirms the bottleneck.

- Check Gene Expression: Use qPCR to verify expression of your NADPH-boosting enzymes (e.g., G6PDH, ME, NOX) is not silenced.

- Induction Timing: Consider decoupling growth and production by using a late-phase or stress-inducible promoter for your FAB genes.

Q2: Overexpressing NADPH regeneration enzymes (e.g., PntAB, G6PD) is causing growth retardation. How can I mitigate this? A: This indicates metabolic burden and redox imbalance.

- Solution 1: Use tunable promoters (e.g., Pbad, T7 with lac operator) to fine-tune expression levels, avoiding toxic overexpression.

- Solution 2: Switch to a NADPH transhydrogenase (PntAB) instead of de novo pathways (PPP) to reduce carbon flux diversion.

- Solution 3: Implement dynamic control where the NADPH regeneration pathway is only induced when cellular NADPH drops below a threshold.

Q3: Our fermentation results show high NADPH levels but low fatty acid yield. What's the disconnect? A: NADPH may not be effectively channeled to the fatty acid synthase (FAS).

- Check for Competing Pathways: Engineer out major NADPH sinks (e.g., knockout gdhA to reduce glutamate synthesis drain).

- Enzyme Colocalization: Create synthetic metabolons by fusing NADPH regeneration enzymes (e.g., malic enzyme) directly to FAS to create a local, high-concentration NADPH pool.

- Substrate Limitation: Ensure acetyl-CoA supply is not the new bottleneck. Overexpress a deregulated acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC).

Q4: Which NADPH regeneration pathway is most effective for my host (E. coli vs. Yeast vs. CHO cells)? A: The optimal pathway is host and condition-dependent. See comparison table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Key NADPH Regeneration Pathways

| Pathway (Enzyme) | Host Organism | Theoretical Yield (NADPH/Glucose) | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentose Phosphate (G6PDH, 6PGDH) | E. coli, Yeast, Mammalian | 2 | Provides precursors for nucleic acids | Carbon loss as CO2, complex regulation | General use, especially if biomass growth is also needed |

| Malic Enzyme (MAE) | E. coli, Yeast | 1 or 2 | Can work anaplerotically | Lower theoretical yield, can be reversible | Systems where TCA intermediates are abundant |

| NADPH Transhydrogenase (PntAB) | E. coli | 0 | Does not consume carbon skeleton, reversible | Membrane-bound, can dissipate proton gradient | Fine-tuning redox balance, high-cell density conditions |

| Ferredoxin-NADP+ Reductase (FNR) | Cyanobacteria, Plants | Varies | Can be light-driven in photoautotrophs | Not native in most industrial hosts | Photosynthetic production systems |

| Formate Dehydrogenase (FDH) | In vitro systems | 1 | Uses inexpensive formate as substrate | Generally low activity/ stability in vivo | Cell-free FAS systems |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enzymatic Assay for Intracellular [NADPH]/[NADP+] Ratio

Objective: Quantify the redox cofactor pool to diagnose limitations. Materials: Quenching solution (60% methanol, -40°C), Extraction buffer (100mM K₂HPO₄, pH 8.0), NADP+/NADPH extraction kit, Cycling assay reagents. Method:

- Rapid Quench: Filter 5 mL of culture and immediately immerse filter in 5 mL -40°C quenching solution for 3 min.

- Metabolite Extraction: Transfer cells to extraction buffer, heat at 95°C for 5 min, then centrifuge at 15,000xg for 10 min. Keep supernatant on ice.

- Specific Measurement:

- For Total NADP(H): Add 20 µL extract to 180 µL total NADP(H) assay buffer (containing alcohol dehydrogenase, diaphorase, resazurin). Monitor fluorescence (Ex/Em 540/590 nm).

- For NADP+ only: Heat separate extract at 60°C for 30 min to degrade NADPH, then assay as above.

- Calculation: NADPH = Total - NADP+. Ratio = NADPH/NADP+.

Protocol 2: Dynamic Knock-in of NOX for NADPH Regeneration

Objective: Implement an oxygen-dependent NADPH oxidase (NOX) to dynamically regenerate NADP+ without carbon loss. Materials: pBAD or other inducible vector, Bacillus subtilis NOX gene, bioreactor with dissolved oxygen (DO) control. Method:

- Clone NOX gene under a promoter sensitive to anaerobic conditions (e.g., nar promoter) or low NADPH.

- Transform into your production host.

- In a fed-batch fermentation, allow growth to high density under high DO.

- Induce FAS and shift to microaerobic conditions (DO <10%). This will concurrently induce NOX expression.

- NOX converts excess NADPH to NADP+, recycling the pool for FAS, while O₂ is reduced to H₂O.

Visualizations

Title: NADPH Regeneration via Pentose Phosphate Pathway

Title: Balancing Growth Phase and FAS Production Phase

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Cofactor Engineering | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic NADP/NADPH Assay Kit | Quantifies oxidized and reduced cofactor pools directly from cell extracts. Critical for diagnosing bottlenecks. | Sigma-Aldrich MAK038, Promega G9081. Prefer cycling assays for sensitivity. |

| qPCR Reagents for Pathway Genes | Validates transcriptional activation of introduced NADPH regeneration genes (e.g., pntAB, zwf). | Use SYBR Green or TaqMan probes specific to your engineered constructs. |

| Tunable Induction Systems | Allows fine-control over expression of NADPH enzymes to avoid metabolic burden. | pBAD (arabinose), Tet-On, T7-lac systems. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents & Standards | For absolute quantification of fatty acid products and central carbon metabolites (e.g., G6P, malate). | Enables flux analysis to see how carbon is diverted. |

| Oxygen-Sensitive Promoters | Enables dynamic, condition-dependent expression of NADPH recycling enzymes (e.g., NOX). | nar, Pvgb promoters for microaerobic response. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | To engineer NADPH-dependent enzymes (e.g., ACC, FAS) for improved binding affinity (lower Km). | NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System | To reconstitute and test NADPH regeneration pathways coupled to FAS in vitro without cellular complexity. | PURExpress (NEB) or PUREfrex. |

| Codon-Optimized Gene Fragments | For heterologous expression of NADPH enzymes (e.g., B. subtilis NOX) in your host for maximum activity. | Synthesized from vendors like IDT or Twist Bioscience. |

Two-Stage and Fed-Batch Fermentation Strategies for Separating Growth and Production Phases

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: In a two-stage fermentation for fatty acid production, cell growth is robust in Stage 1, but productivity crashes after the inducer is added in Stage 2. What could be the cause? A: This is often due to nutrient exhaustion or a metabolic burden shock. Ensure the production medium (Stage 2) contains sufficient carbon and energy sources to support both maintenance and product synthesis. Monitor dissolved oxygen (DO) closely; a rapid drop post-induction indicates an unsustainable metabolic load. Consider a fed-batch approach in Stage 2 to gradually feed nutrients.

Q2: When switching to a production phase, how do I determine the optimal time for induction or medium shift? A: Induction should occur at the late exponential phase, typically when the culture reaches a specific optical density (OD₆₀₀) or cell dry weight (CDW). The precise threshold depends on your organism. Perform a time-course experiment measuring growth and a key metabolite (e.g., acetyl-CoA for fatty acid biosynthesis) to identify the inflection point just before growth rate decline.

Q3: We observe acetate/byproduct accumulation in our fed-batch process aimed at separating growth and production. How can this be mitigated? A: Acetate accumulation (overflow metabolism) occurs when the glucose feed rate exceeds the cells' oxidative capacity. Implement an exponential feeding strategy that matches the culture's maximum substrate consumption rate. Use online monitoring (pH, DO spikes) to control the feed rate dynamically. Alternatively, switch to a less-repressive carbon source like glycerol for the production phase.

Q4: Our fatty acid yields are inconsistent between bioreactor runs using the same two-stage protocol. What are the key parameters to tightly control? A: Focus on the reproducibility of the transition point. Key parameters include:

- Precise harvesting of Stage 1 cells: Control centrifugation/resuspension time and temperature.

- Production medium temperature and pH: Deviations can drastically alter enzyme kinetics in biosynthesis pathways.

- Inducer concentration homogeneity: Ensure rapid and uniform mixing upon addition.

Q5: For a fed-batch strategy, what is the best feeding strategy to decouple growth from production? A: A "limited-growth" or "maintenance feeding" strategy post-induction is most effective. After inducing the production pathway, reduce the feed rate to provide substrates primarily for product formation and cell maintenance, not for net growth. This often requires a shift from an exponential to a constant, low feed rate.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Two-Stage Fermentation for Fatty Acid Overproduction Objective: To maximize fatty acid titer by first achieving high cell density, then switching cells to a production-optimized medium.

- Stage 1 (Growth): Inoculate a 5L bioreactor containing 3L of rich growth medium (e.g., LB or TB). Incubate at optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli) with controlled pH (7.0) and high agitation/aeration to maintain DO >30%.

- Monitoring: Sample periodically to measure OD₆₀₀ and CDW. Calculate the specific growth rate (μ).

- Harvest & Transition: At OD₆₀₀ ~10-15 (mid-late exponential phase), rapidly transfer cells via peristaltic pump to a second, sterile bioreactor containing 2L of production medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium with glycerol, specific nitrogen sources, and cofactors like biotin).

- Stage 2 (Production): Immediately add pathway inducer (e.g., IPTG for engineered systems) and any pathway-specific precursors (e.g., malonate). Lower temperature to 30°C to reduce metabolic burden. Maintain pH and DO. Supplement with a controlled, low feed of carbon source if needed.

- Termination: Harvest cells 24-48 hours post-induction for fatty acid extraction and analysis.

Protocol 2: Fed-Batch Process with Inducer-Based Phase Separation Objective: To achieve high cell density and high productivity in a single vessel by using feeding and induction control.

- Batch Phase: Begin with a defined volume (e.g., 2L in a 5L vessel) of complete medium. Allow cells to grow at maximum μ until the initial carbon source (e.g., glucose) is nearly depleted, indicated by a sharp DO rise.

- Fed-Batch Growth Phase: Initiate an exponential feed of concentrated carbon/nutrient feed solution. The feed rate, F(t), is calculated as F = (μ/V) * (X₀ * V₀ / Y˅(x/s)) * e^(μ*t), where X₀ is initial biomass, V₀ is initial volume, and Y˅(x/s) is yield coefficient. Maintain this to achieve high cell density while avoiding overflow metabolism.

- Induction/Production Trigger: At the target CDW (e.g., 50 g/L), add the inducer. Simultaneously, switch the feed solution to a "production feed" with a lower C:N ratio, possible alternative carbon source, and essential precursors.

- Production Phase Feeding: Reduce the feed rate to a constant, maintenance level (typically 10-25% of the final growth phase rate) to limit further growth and direct resources toward product formation.

- Process Monitoring: Continuously monitor and control pH, DO, and off-gas analysis. Use DO spikes or pH rises as indicators to adjust feed rates dynamically.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Two-Stage vs. Fed-Batch Strategies for Fatty Acid Production

| Parameter | Two-Stage Fermentation | Fed-Batch Fermentation (Induction-Triggered) |

|---|---|---|

| Max Cell Density (g CDW/L) | 15-25 (at end of Stage 1) | 50-100+ |

| Volumetric Productivity (mg/L/h) | Medium-High | Very High |

| Process Complexity | High (two vessels, transfer step) | Medium (single vessel, complex control) |

| Scale-Up Challenge | Sterile transfer at scale | Feed and mixing control at high density |