Kinetic vs. Stoichiometric Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of kinetic and stoichiometric metabolic models, two foundational approaches in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Kinetic vs. Stoichiometric Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of kinetic and stoichiometric metabolic models, two foundational approaches in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles, unique strengths, and inherent limitations of each framework. We delve into their methodological applications, from predicting flux distributions to simulating dynamic pathway behavior, and address key challenges in model construction, parameterization, and optimization. By synthesizing validation strategies and offering a clear comparative analysis, this guide aims to empower the informed selection and application of metabolic modeling techniques to advance biomedical discovery and therapeutic design.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Differences Between Kinetic and Stoichiometric Frameworks

Stoichiometric models have become indispensable tools in metabolic engineering and systems biology for predicting organism behavior and optimizing strains for industrial and therapeutic applications. This guide provides a comparative analysis of stoichiometric modeling against kinetic modeling, detailing the core principles, experimental methodologies, and practical applications that define their use in research and drug development.

Core Principles and Comparative Framework

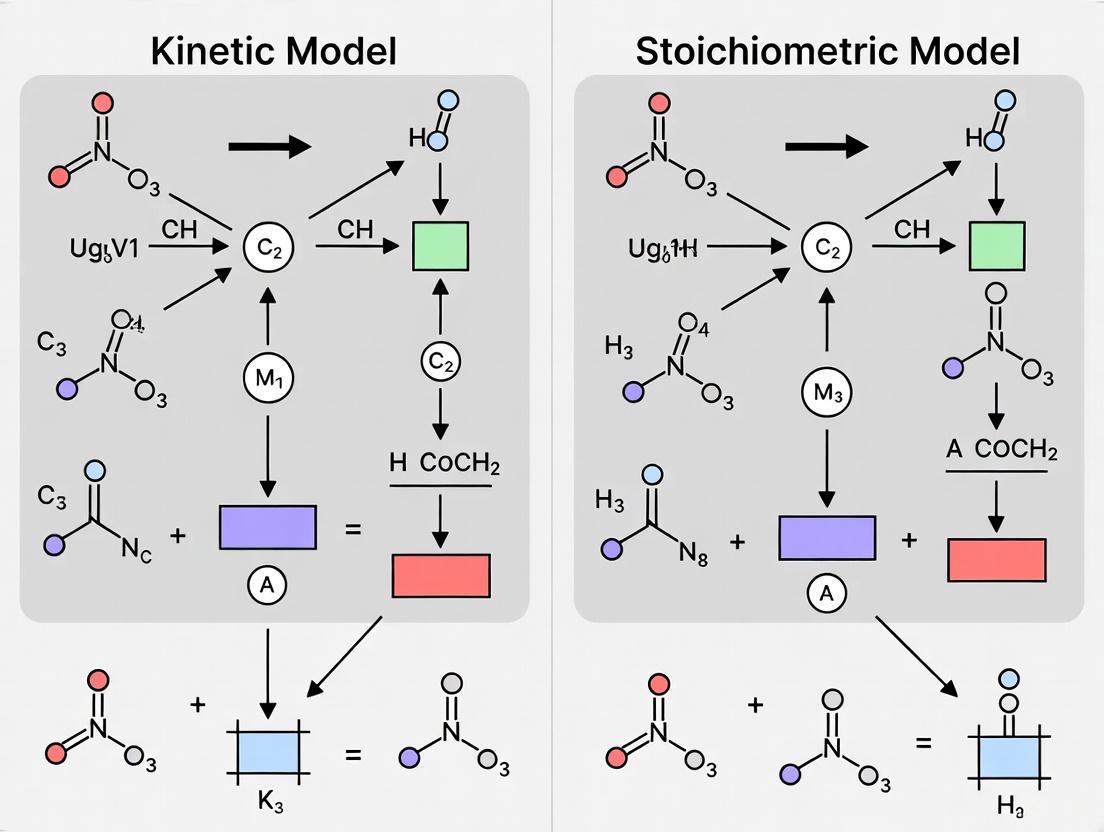

Stoichiometric and kinetic models represent two fundamentally different approaches to modeling metabolic networks. The table below summarizes their defining characteristics and primary constraints.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Stoichiometric and Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Stoichiometric Models | Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Basis | Mass balance constraints and the steady-state assumption [1] [2]. | Reaction rate laws and enzyme kinetics [1]. |

| Temporal Dynamics | Do not simulate changes over time; analyze feasible steady-states [1] [2]. | Explicitly simulate metabolite concentrations and fluxes as functions of time [1]. |

| Model Scale | Applicable at genome-scale (1000s of reactions) [1]. | Typically limited to pathways or subsystems (10s of reactions) [1]. |

| Primary Constraints | Reaction stoichiometry, flux bounds, reaction directionality [1]. | Kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat, Km), enzyme concentrations, metabolite concentrations [1]. |

| Key Outputs | Steady-state flux distributions, network capabilities (e.g., FBA) [2]. | Dynamic profiles of metabolite levels and reaction fluxes [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Construction and Validation

The construction and application of genome-scale stoichiometric models follow a structured pipeline, from network reconstruction to experimental validation. The workflow below outlines the key stages in developing a functional metabolic model.

Detailed Methodologies

Genome-Scale Reconstruction: This foundational step involves building a network of all known metabolic reactions in an organism based on its genomic and biochemical data [2]. The output is a stoichiometric matrix (N), where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. Each element nij denotes the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [2].

Defining the Biomass Objective Function (BOF): The BOF is a pseudo-reaction that drains essential biomass precursors (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, lipids) in proportions required to form new cellular material [3]. Accurately defining the BOF is critical for predicting growth phenotypes. Tools like BOFdat use experimental data to generate species-specific BOFs in a standardized way, calculating coefficients for major macromolecules and identifying key coenzymes [3].

Applying Physiological Constraints: The model is constrained using physiological data:

- Flux Boundaries: Setting lower and upper bounds (

lb,ub) for reaction fluxes, often based on enzyme capacity or substrate uptake rates [1]. For example, an irreversible reaction would havelb = 0. - Thermodynamic Constraints: Enforcing reaction directionality based on energy considerations [1].

- Total Enzyme Capacity: Constraining the sum of enzyme activities to reflect the organism's limited protein synthesis resources [1].

- Flux Boundaries: Setting lower and upper bounds (

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): FBA is a widely used computational method to predict steady-state reaction fluxes [2] [4]. It involves solving the system of linear equations defined by N · v = 0 (where v is the flux vector) subject to the applied constraints. This is typically done while optimizing a biological objective, such as maximizing biomass growth or the production of a target metabolite [2] [4].

Validation with Experimental Data: Model predictions are validated against experimental data, such as measured growth rates or gene essentiality data [3] [5]. Techniques like flux variability analysis (FVA) assess the range of possible fluxes for each reaction. Models can also be refined by integrating omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) to create context-specific models, which results in more precise simulations [5].

Supporting Experimental Data and Case Studies

Case Study: Predicting Metabolic Biomarkers with SAMBA

The SAMpling Biomarker Analysis (SAMBA) approach demonstrates the application of stoichiometric models to predict metabolic changes in disease states [4]. It uses a human genome-scale metabolic model to simulate fluxes in exchange reactions under healthy and perturbed (e.g., gene knock-out) conditions. By comparing the simulated flux distributions, it ranks differentially exchanged metabolites as potential biomarkers detectable in biofluids like blood or urine [4]. This method shows good concordance with experimental metabolite differential abundances from patient databases and mGWAS studies, providing a computational tool for biomarker discovery and study design [4].

Case Study: The Impact of Constraints in Kinetic Modeling

While not a stoichiometric model, a kinetic model of sucrose accumulation in sugarcane illustrates the critical role of constraints in generating biologically feasible predictions [1]. An unconstrained optimization suggested a massive (2.6 × 10^6-fold) increase in the objective function, requiring unrealistic 1500-fold changes in metabolite concentrations [1]. The introduction of a total enzyme activity constraint (preventing an overall increase in enzyme levels) and a homeostatic constraint (limiting metabolite concentration changes to ±20%) drastically reduced the predicted objective function to a biologically plausible 4.7-fold increase [1]. This highlights how constraints prevent over-optimistic predictions by accounting for cellular limitations.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance to Model Type |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model | A structured knowledge base of an organism's metabolism (e.g., Recon for human, iML1515 for E. coli). | Serves as the foundational framework for both stoichiometric and kinetic modeling [1] [4]. |

| Biomass Objective Function (BOF) | A pseudo-reaction defining the drain of biomass precursors for growth. | Essential for predicting growth phenotypes in stoichiometric models using FBA [3]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A computational algorithm to predict steady-state reaction fluxes. | The primary simulation method for stoichiometric models [2] [4]. |

| Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (kcat, Km) | Constants defining the catalytic rate and substrate affinity of an enzyme. | Core parameters required for constructing and simulating kinetic models [1]. |

| BOFdat | A Python package for generating BOFs from experimental data. | Standardizes the creation of a critical component in stoichiometric models [3]. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software (e.g., COBRA) | Software toolboxes for performing FBA, FVA, and related analyses. | Enables simulation and analysis of genome-scale stoichiometric models [4]. |

Stoichiometric models, defined by their foundation in mass balance and the steady-state assumption, offer a powerful and scalable framework for analyzing metabolic networks at the genome scale. Their ability to integrate diverse experimental constraints and data types makes them particularly valuable for predicting metabolic phenotypes, identifying engineering targets, and, as shown by tools like SAMBA, discovering clinically relevant biomarkers. While kinetic models provide superior dynamic resolution, the scalability and integrative capacity of stoichiometric models ensure their continued central role in metabolic research and drug development.

This guide provides an objective comparison between kinetic and stoichiometric models of metabolism, detailing their core principles, applications, and performance based on current research data and methodologies.

Core Model Comparison: Kinetic vs. Stoichiometric Frameworks

Kinetic and stoichiometric models are fundamental to metabolic research, yet they differ significantly in structure, data requirements, and predictive capabilities. The table below summarizes their defining characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Kinetic and Stoichiometric Models

| Feature | Kinetic Models | Stoichiometric Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | System of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) describing reaction rates [6] | Stoichiometric matrix representing mass balance of all reactions [1] |

| Primary Input | Kinetic parameters (e.g., ( Km ), ( V{max} )), enzyme levels, metabolite concentrations [6] [7] | Reaction stoichiometry, network topology, flux constraints [1] |

| Dynamic Capability | Predicts time-dependent changes in metabolite concentrations and fluxes [8] [6] | Analyzes feasible steady-states; no inherent time component [1] |

| Key Constraints | Thermodynamic laws, enzyme activity, metabolite homeostasis [1] | Mass balance, energy balance, steady-state assumption [1] |

| Typical Scale | Pathway- to large-scale (100s of reactions) [6] [7] | Genome-scale (1000s of reactions) [1] |

| Regulatory Insight | Explicitly models enzyme inhibition, activation, and allosteric regulation [6] | Infers regulation indirectly through constraints; no explicit kinetics [1] |

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

The practical performance of these modeling approaches is assessed through their ability to recapitulate experimental observations and generate testable hypotheses.

Table 2: Model Performance and Experimental Validation

| Aspect | Kinetic Models | Stoichiometric Models |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Demand | High; requires parameter sampling and ODE integration [6] | Low; typically uses linear programming [1] |

| Data Integration | Directly integrates metabolomics, fluxomics, and proteomics into ODEs [6] [7] | Integrates omics data as inequality constraints on fluxes [6] |

| Representative Performance | REKINDLE: Generates models with up to 97.7% incidence of desired dynamics [8].RENAISSANCE: Achieves up to 100% valid models matching E. coli doubling time [7] | Accurately predicts steady-state fluxes and essential genes in many organisms [1] |

| Perturbation Robustness | RENAISSANCE: 100% of 1,000 perturbed models returned to steady-state [7] | Not designed for dynamic perturbation analysis [1] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Populations of models represent parameter uncertainty [8] [7] | Solution space analysis (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis) shows possible flux distributions [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Model Generation

The REKINDLE Protocol (Deep Learning-Based Generation)

The REKINDLE framework uses generative adversarial networks (GANs) to create kinetic models with tailored dynamic properties [8].

- Input and Labeling: A dataset of kinetic parameter sets is generated using traditional sampling methods (e.g., via ORACLE framework). Each parameter set is labeled as "biologically relevant" or "not relevant" based on whether the resulting model's dynamic responses (e.g., time evolution of metabolic states) match experimental observations [8].

- Network Training: A conditional GAN, comprising generator and discriminator neural networks, is trained on the labeled dataset. The generator learns to produce kinetic parameters, while the discriminator learns to distinguish them from real "relevant" parameters [8].

- Model Generation: The trained generator is used to produce new kinetic parameter sets conditioned on the "relevant" class [8].

- Validation: The generated models undergo rigorous validation, including:

- Statistical comparison of parameter distributions to the training data (e.g., Kullback-Leibler divergence).

- Linear stability analysis (eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix) to verify dynamic properties.

- Dynamic response testing against perturbations to assess robustness [8].

Figure 1: The REKINDLE workflow for generating kinetic models using deep learning.

The RENAISSANCE Protocol (Machine Learning-Based Parameterization)

RENAISSANCE employs neural networks and natural evolution strategies (NES) to parameterize models without pre-existing training data [7].

- Input and Initialization: The framework starts with a steady-state profile of metabolite concentrations and fluxes. A population of generator neural networks is initialized with random weights [7].

- Parameter Generation and Evaluation: Each generator produces a batch of kinetic parameters, which are used to parameterize the kinetic model. The dynamics of each model are evaluated by computing the eigenvalues of its Jacobian matrix to check if they match experimentally observed timescales (e.g., a dominant time constant corresponding to the cell doubling time) [7].

- Reward and Evolution: A reward is assigned to each generator based on the proportion of generated models that are valid (i.e., have the correct dynamics). The weights of the generators are updated using a NES algorithm, which mutates the highest-reward generators to create a new population for the next generation [7].

- Iteration: The process of generation, evaluation, and evolution is repeated iteratively until a generator is obtained that meets the design objective, such as a high incidence of biologically relevant kinetic models [7].

Figure 2: The RENAISSANCE iterative framework for parameterizing kinetic models.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

This section lists key software and resources used in modern kinetic and stoichiometric modeling.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type/Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SKiMpy | Software Toolbox | A semiautomated workflow for constructing and parametrizing kinetic models using a stoichiometric model as a scaffold; implements the ORACLE framework for sampling kinetic parameters [6]. |

| Tellurium | Software Environment | A versatile modeling tool for systems and synthetic biology that supports standardized model formulations, ODE simulation, and parameter estimation [6]. |

| MASSpy | Software Toolbox | A framework for kinetic model construction that is built on COBRApy, enabling integration with constraint-based modeling tools; often uses mass-action rate laws by default [6]. |

| GINtoSPN | R Package | Automates the conversion of molecular interaction networks from a Global Integrative Network (GIN) into Petri net models for simulation [9]. |

| PetriNuts Platform | Computational Platform | A set of tools utilizing colored Petri nets for constructing and analyzing complex, multilevel biological models [10]. |

| MONALISA | Open-Source Software | Provides creation, visualization, and analysis of Petri nets, including stochastic simulation capabilities using algorithms like Gillespie's SSA [11]. |

| Kinetic Parameter Databases | Data Resource | Curated collections of enzyme properties (e.g., ( Km ), ( k{cat} )) used to inform and parameterize kinetic models [6]. |

| Thermodynamic Data | Data Resource | Estimated Gibbs free energies of reactions, calculated using methods like group contribution, used to enforce thermodynamic constraints [6] [1]. |

Mathematical models are indispensable tools for simulating the complex reaction networks of cellular metabolism, aiding in drug development and biotechnological advances [12] [1]. The behavior of these biological systems is not arbitrary but is strongly determined by fundamental physical constraints. Universal laws governing mass and energy impose strict boundaries on what metabolic networks can and cannot do. Mass conservation, energy balance, and thermodynamic principles form the non-negotiable foundation upon which all physically feasible models are built [12] [1]. For researchers and scientists, the conscious integration of these constraints is what separates predictive, biologically relevant models from computationally convenient but physically impossible simulations. This guide provides a detailed comparison of how these universal constraints are implemented across the two primary modeling approaches: kinetic and stoichiometric models. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate modeling framework for a given application, interpreting results correctly, and developing strategies that are feasible in real-world biological systems.

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Frameworks

Kinetic and stoichiometric models serve distinct but complementary roles in metabolic engineering and systems biology. Their core differences lie in how they handle time, concentration, and the application of universal constraints.

- Stoichiometric Models, also known as Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) models, rely on the steady-state assumption and a known stoichiometric matrix to define the network structure. They require less detailed information and can be applied at the genome scale [1] [13]. A key tool for these models is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which optimizes an objective function (e.g., biomass production) to predict flux distributions without calculating metabolite concentrations or temporal dynamics [13].

- Kinetic Models use ordinary differential equations to describe the temporal changes in metabolite concentrations, relating reaction fluxes to concentrations, enzyme levels, and kinetic parameters [14]. They are nonlinear, highly parameterized, and typically cover smaller pathways, but they excel at predicting dynamic behavior, transient states, and regulatory mechanisms far from steady state [14] [6].

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of Stoichiometric and Kinetic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Stoichiometric Models | Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Basis | Stoichiometric matrix & mass balance [13] | Ordinary differential equations & kinetic rate laws [14] |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state only (no time dynamics) [1] | Dynamic (can simulate changes over time) [14] [6] |

| Metabolite Concentrations | Not calculated [1] | Core output of the model [14] |

| Typical Network Scale | Genome-scale [1] | Pathway-scale (a few to dozens of reactions) [1] |

| Key Constraints | Mass balance, steady-state, flux bounds [1] [13] | Mass balance, thermodynamics, enzyme kinetics [12] [1] |

| Implementation of Thermodynamics | As inequality constraints on reaction directionality [1] [6] | Directly embedded in reaction rate equations [12] [6] |

The Application of Universal Constraints

The predictive power of both modeling frameworks hinges on their adherence to universal physical constraints. The following sections and table detail how these principles are implemented.

Mass Conservation

The principle of mass conservation states that mass cannot be created or destroyed. In metabolic models, this is captured by balance equations. For stoichiometric models, this is the foundational constraint, expressed as S·v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector, ensuring that for every internal metabolite, the mass consumed equals the mass produced [1] [13]. In kinetic models, mass conservation is structurally embedded within the system of ordinary differential equations, where the rate of change of each metabolite concentration is equal to its production flux minus its consumption flux [12].

Energy Balance and Thermodynamics

The laws of thermodynamics are critical for ensuring that models do not describe biologically impossible systems, such as a chemical perpetual motion machine [12]. The second law, in particular, demands that a system will reach thermodynamic equilibrium if isolated from its surroundings.

- Detailed Balance and Wegscheider Conditions: For kinetic models of closed systems, the principle of detailed balance (microscopic reversibility) requires that at thermodynamic equilibrium, every individual reaction has a net flux of zero [12]. This imposes the Wegscheider conditions on the kinetic parameters, ensuring that the product of equilibrium constants around any stoichiometric cycle equals one [12]. Violating these conditions results in thermodynamically infeasible models.

- Directionality and Thermodynamic Feasibility: In stoichiometric models, thermodynamic constraints are often applied as inequality constraints that limit the direction of reactions based on the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) [1]. This prevents cycles that create energy from nothing. Kinetic models naturally incorporate this through the structure of their rate laws, where the ratio of forward and backward reaction rates is dictated by the displacement from thermodynamic equilibrium [6].

- Energy Dissipation in Growing Systems: A recent analysis of unicellular growth data revealed an empirical thermodynamic rule: the amount of energy dissipated per unit of biomass grown is largely conserved across different metabolic types and domains of life, with a median value of approximately 500 kJ per carbon mole (Cmol) of biomass [15]. This highlights a fundamental thermodynamic constraint on metabolic versatility.

Table 2: Comparison of Universal Constraint Implementation

| Constraint | Implementation in Stoichiometric Models | Implementation in Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Conservation | Foundation of the model via the steady-state assumption: S·v = 0 [1] [13]. | Embedded in the structure of the ODEs: ( \frac{dci}{dt} = \sum S{ij} v_j ) [12]. |

| Energy Balance / 1st Law | Validated by comparing predicted enthalpy changes with calorimetric heat measurements [15]. | Implicitly ensured by correct parametrization and adherence to the second law. |

| Thermodynamics / 2nd Law | Applied as directionality constraints on fluxes; prevents thermodynamically infeasible cycles [1]. | Detailed Balance: Ensures zero flux at equilibrium for all reactions [12]. Rate Laws: Reaction direction is a function of the thermodynamic force [12] [6]. |

| Key Experimental Validation | Feasibility of steady-state flux distributions [13]. | Agreement with time-resolved metabolomics data and observed stable steady states [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Constraint Validation

Protocol for Validating Mass Conservation and Energy Balance

This protocol is used to validate the fundamental constraints of macroscopic growth data, as applied in large-scale analyses of unicellular growth [15].

- Data Collection: Gather measured exchange fluxes from growth experiments, including substrate consumption, product formation, and biomass production rates. Key yields (e.g., biomass per electron donor) are often used.

- Stoichiometric Balancing (Element Conservation): For any unmeasured yields, use element conservation (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen) to infer the missing values and balance the "macrochemical equation" of growth.

- Enthalpy and Heat Calculation: Calculate the net exchange of enthalpy from the stoichiometrically balanced growth equation.

- Calorimetric Validation: Compare the predicted enthalpy exchange with direct calorimetric measurements of heat released during growth. A strong agreement validates the application of the first law [15].

- Dissipation Calculation: Compute the free energy dissipation per electron donor consumed using the framework of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. The second law is validated if >99% of data points show net dissipation [15].

Protocol for Imposing Detailed Balance in Kinetic Models

This methodology ensures that a kinetic model obeys the principle of detailed balance, making it thermodynamically feasible [12].

- Identify All Stoichiometric Cycles: Analyze the complete, uncompressed stoichiometry of the network to identify all true cyclic reaction paths. Note: Futile cycles driven by external energy sources (e.g., ATP hydrolysis) are excluded from this analysis [12].

- Formulate Wegscheider Conditions: For each identified cycle, formulate the condition that the product of the equilibrium constants (or the ratio of forward/backward kinetic constants) around the cycle must equal one.

- Parameterization: During model parameterization, either:

- Constrained Fitting: Use the Wegscheider conditions as explicit constraints during parameter estimation.

- Use a Thermodynamic-Kinetic Formalism: Adopt a modeling formalism that structurally enforces detailed balance by defining reaction rates as functions of thermokinetic potentials and forces, making detailed balance inherent for all parameter values [12].

- Validation: Simulate the model with all boundary fluxes set to zero. A valid model will reach a steady state where all reaction fluxes are zero, confirming the existence of a thermodynamic equilibrium.

Workflow Diagram: Implementing Constraints in Metabolic Models

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for applying universal constraints in metabolic modeling.

The following table lists key computational tools, databases, and conceptual "reagents" essential for developing and constraining metabolic models.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [6] | Software Toolbox | Python-based simulation and analysis of stoichiometric models. | Enforces mass balance and steady-state; applies flux constraints. |

| SKiMpy [6] | Software Toolbox | Semi-automated construction and parametrization of large-scale kinetic models. | Samples kinetic parameters consistent with thermodynamic constraints. |

| AGORA & BiGG [13] | Model Databases | Repositories of curated, genome-scale metabolic models. | Provides high-quality, mass-balanced stoichiometric templates. |

| Group Contribution Method [6] | Computational Method | Estimates standard Gibbs free energy of reactions (ΔG°') for metabolites. | Provides essential parameters for applying thermodynamic constraints. |

| Tellurium [6] | Software Toolbox | Kinetic modeling and simulation in systems and synthetic biology. | Used for simulating ODEs and fitting models to time-resolved data. |

| Thermodynamic-Kinetic Modeling (TKM) [12] | Modeling Formalism | A framework using potentials and forces from irreversible thermodynamics. | Structurally observes detailed balance, ensuring thermodynamic feasibility. |

| Homeostatic Constraint [1] | Modeling Concept | Limits optimized metabolite concentrations to a physiologically plausible range. | Prevents unrealistic model predictions that violate cellular regulation. |

| Total Enzyme Activity Constraint [1] | Modeling Concept | Sets a limit for the sum of enzyme concentrations in a cell. | Accounts for limited proteomic resources, improving model feasibility. |

The quest to understand and predict cellular phenotype has positioned metabolic modeling as a cornerstone of systems biology. Within this field, two predominant frameworks have emerged: stoichiometric (constraint-based) models and kinetic models. Both aim to decipher the complex interplay of biochemical reactions within an organism, but they approach the integration of organism-level constraints—such as enzyme activity limits and homeostatic control—from fundamentally different angles. Constraint-based models simulate metabolism by leveraging reaction stoichiometry and thermodynamic constraints to define a space of possible flux distributions at steady state [16]. In contrast, kinetic models employ detailed reaction rate laws and enzyme kinetic parameters to simulate the dynamic changes in metabolite concentrations over time [16]. The central thesis of this comparison is that while both frameworks are powerful, their effectiveness in incorporating the critical biological realities of enzyme capacity and homeostatic regulation varies significantly, influencing their suitability for specific applications in drug development and basic research.

The concept of homeostasis—the maintenance of a stable internal environment despite external perturbations—is a fundamental physiological principle [17] [18]. At the cellular level, homeostatic control mechanisms ensure that variables like pH, temperature, and energy charge remain within narrow limits conducive to optimal enzyme function and cell survival [18]. These controls often operate through feedback loops, where a sensor detects a change in a variable and triggers effector responses to counteract it, a process known as negative feedback [19]. Metabolism is a primary target of such regulation, which is achieved through allostery, enzyme abundance adjustments, and post-translational modifications [16]. Consequently, any metabolic model that aspires to predictive accuracy must adequately represent these constraints. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of how kinetic and stoichiometric models meet this challenge, supported by experimental data and protocol details.

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Frameworks

Fundamental Principles and Data Requirements

The core distinction between the two modeling approaches lies in their structure and foundational assumptions.

Stoichiometric Models, including those analyzed with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), are built upon the stoichiometric matrix (S), which encapsulates the mass balance of all metabolic reactions [16]. The fundamental equation is Sv = 0, which assumes the system is at a steady state, with no net accumulation or depletion of internal metabolites [20] [16]. These models typically require three sets of data: the network stoichiometry, the reversibility/irreversibility of reactions, and upper/lower flux bounds [20]. A major advantage is their scalability to genome-size, enabling system-wide analyses without requiring extensive kinetic parameter sets [16].

Kinetic Models use ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe the rate of change of metabolite concentrations: dx/dt = Sv, where v is a vector of reaction rates (fluxes) that are typically nonlinear functions of metabolite concentrations, enzyme levels, and kinetic parameters [16]. These models excel at simulating transient dynamics and the effects of metabolic perturbations. However, they are often limited to smaller pathways due to the scarcity of reliable kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) and the computational complexity of integrating large sets of ODEs [16].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Stoichiometric and Kinetic Models

| Feature | Stoichiometric Models | Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear algebra (Stoichiometric matrix) [16] | Nonlinear ordinary differential equations [16] |

| Primary Inputs | Network stoichiometry, Reaction bounds [20] | Kinetic parameters (kcat, Km), Enzyme concentrations [16] |

| Temporal Resolution | Steady-state [16] | Dynamic (time-course) [16] |

| Typical Network Size | Genome-scale (1000s of reactions) [16] | Small to medium-scale pathways (10s-100s of reactions) [16] |

| Treatment of Enzyme Constraints | Often via linear capacity constraints (e.g., v_i ≤ kcat_i * E_i) [20] [21] |

Explicitly embedded in nonlinear reaction rate laws [16] |

| Incorporation of Homeostasis | Implicit via steady-state assumption and flux boundaries [16] | Explicit via feedback mechanisms in rate laws [16] |

Performance and Predictive Capabilities

Experimental applications of both modeling paradigms highlight their distinct strengths and weaknesses in predicting metabolic behavior.

Stoichiometric models have been successfully enhanced by incorporating enzyme constraints to improve phenotype predictions. The GECKO (Genzyme-Consrained using Kinetic and Omics data) framework, for instance, expands the stoichiometric matrix by adding enzymes as pseudo-metabolites and introduces a capacity constraint for each reaction: v_j ≤ kcat_j * E_j [21]. When applied to a genome-scale model of Aspergillus niger, the GECKO-enhanced model demonstrated a significant reduction in the solution space, with flux variability decreasing in over 40% of metabolic reactions [21]. This model also showed improved accuracy in predicting gene essentiality and differential enzyme expression across different growth conditions [21]. Similarly, the sMOMENT method incorporates an enzyme allocation constraint, Σ v_i * (MW_i / kcat_i) ≤ P, which limits the total mass of metabolic enzymes [20]. This approach, applied to an E. coli model, successfully predicted metabolic switches like overflow metabolism without needing to pre-constrain substrate uptake rates [20].

Kinetic models, while more parameter-intensive, offer a more direct and mechanistic representation of homeostasis and regulation. They can explicitly represent feedback inhibition, where an end-product allosterically inhibits an upstream enzyme, thereby maintaining metabolite homeostasis [16]. A study investigating optimal enzyme utilization from an evolutionary perspective developed a framework to estimate kinetic parameters that maximize catalytic efficiency (v_net / E_tot) under given metabolite concentrations and thermodynamic constraints [22]. This approach revealed that optimal enzyme operation is highly dependent on reactant concentrations and that random-order binding mechanisms are often optimal under physiological conditions [22]. Such insights are crucial for understanding the design principles of homeostatic control but are difficult to derive from purely stoichiometric models.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison from Case Studies

| Application / Metric | Stoichiometric Model with Enzyme Constraints | Kinetic Model |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction of Overflow Metabolism | Successfully predicted in E. coli [20] | Naturally emerges from substrate-level regulation |

| Flux Variability Reduction | >40% reduction in A. niger [21] | Not directly applicable (single solution per condition) |

| Gene Knockout Simulation | Improved prediction accuracy [21] | High accuracy for small networks [16] |

| Requirement for Kinetic Parameters | Low (only kcat values required) [20] [21] |

High (full kcat, Km sets required) [16] |

| Dynamic Response to Perturbation | Not directly possible | High fidelity [16] |

| Scalability to Genome-Scale | High (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli) [20] | Low, limited by parameter availability [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Incorporating Constraints

Protocol for Building an Enzyme-Constrained Stoichiometric Model (GECKO)

The GECKO method provides a standardized workflow for enhancing a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) with enzyme constraints [21].

- Model Preprocessing: Convert the base GEM into an irreversible model. This involves splitting every reversible reaction into separate forward and backward reactions.

- Data Acquisition:

- Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (

kcat): Collectkcatvalues from databases like BRENDA [23] [21] and SABIO-RK [20]. For reactions without data, use a pipeline to estimatekcatvalues, for example, by using cross-species data or machine learning models. - Enzyme Abundance (Proteomics): Obtain absolute enzyme abundance data (in mg/gDW) from resources like PAXdb [21] or organism-specific proteomics studies.

- Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (

- Model Expansion:

- Introduce each enzyme as a "fake" metabolite in the reactions it catalyzes.

- For each enzyme-catalyzed reaction

j, add the enzyme to the reaction with a stoichiometric coefficient of-1/kcat_j. For example, the reactionA -> Bcatalyzed by enzymeEbecomesA + (1/kcat_E) E -> B. - Introduce a "draw" reaction for each enzyme (

-> E) to represent its synthesis and set its upper bound to the measured enzyme abundance,E_j.

- Handling Isozymes and Complexes:

- For isozymes (different enzymes catalyzing the same reaction), create a pseudo-metabolite and branch the reaction through each isozyme with its specific

kcat. - For enzyme complexes, ensure the stoichiometry reflects the number of subunits required for a functional catalyst.

- For isozymes (different enzymes catalyzing the same reaction), create a pseudo-metabolite and branch the reaction through each isozyme with its specific

- Model Simulation and Analysis: Use the expanded model with standard constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) or Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to predict growth rates, flux distributions, and gene essentiality [21]. The enzyme constraints will naturally limit the maximum flux through reactions based on the available enzyme pool.

Protocol for Constructing a Kinetic Model with Regulatory Feedback

Building a kinetic model capable of simulating homeostatic control involves capturing regulatory interactions within the reaction rate laws.

- Network Definition: Define the stoichiometry of the pathway of interest, including all metabolites, reactions, and enzymes.

- Parameterization:

- Kinetic Parameters: Collect

Km(Michaelis constant) andkcatvalues from databases like BRENDA [23] or the literature. For missing parameters, use parameter estimation algorithms fitted to experimental data (e.g., metabolite time-courses or steady-state fluxes) [16]. - Regulatory Parameters: Identify known allosteric activators and inhibitors from the literature. For each regulatory interaction, determine a dissociation constant (

Kd) and the type of effect (activation/inhibition).

- Kinetic Parameters: Collect

- Formulate Rate Laws: Use appropriate mathematical functions that incorporate both substrate/product kinetics and regulation. A generalized Michaelis-Menten equation with allosteric terms is often used. For example, a rate law for reaction

vinhibited by metaboliteIcould be:v = (Vmax * [S] / (Km + [S])) * (Ki / (Ki + [I]))whereVmax = kcat * [Enzyme_total]. - Model Implementation and Simulation:

- Code the system of ODEs

dx/dt = Svin a suitable software environment (e.g., Python with SciPy, MATLAB, or specialized tools like IsoSim [24]). - Use an ODE solver to simulate the system dynamics over time from a defined initial state.

- Code the system of ODEs

- Model Validation: Test the model's ability to maintain homeostasis by simulating perturbations, such as a sudden change in substrate availability or a gene knockout. A valid homeostatic model should show robust return of key metabolite concentrations to their steady-state levels after a transient response.

Visualization of Modeling Approaches and Constraints

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and the integration of constraints in both modeling frameworks.

Enzyme-Constrained Stoichiometric Modeling

Kinetic Modeling with Homeostasis

Successful development and application of metabolic models rely on a suite of computational tools, databases, and software.

Table 3: Key Resources for Metabolic Modeling with Organism-Level Constraints

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA [23] [21] | Database | Comprehensive repository of enzyme kinetic data (kcat, Km). |

Provides essential parameters for both enzyme capacity constraints in stoichiometric models and rate laws in kinetic models. |

| SABIO-RK [20] | Database | Curated database for biochemical reaction kinetics. | Source for organism-specific kinetic parameters, enhancing model biological relevance. |

| COBRA Toolbox [21] | Software Suite | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling and analysis. | Used to implement and simulate enzyme-constrained models (e.g., GECKO, sMOMENT). |

| AutoPACMEN [20] | Software Tool | Automated pipeline for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models. | Automates the integration of enzymatic data from databases into a stoichiometric model using the sMOMENT method. |

| GECKO Toolbox [21] | Software Tool | A toolbox for enhancing GEMs with enzyme constraints. | Implements the GECKO framework, facilitating the incorporation of proteomics and kinetic data. |

| IsoSim [24] | Software Tool | R package for kinetic and isotopic modeling. | Enables the simulation of metabolic dynamics, including the integration of regulatory constraints. |

| PAXdb [21] | Database | Resource for protein abundance data across organisms. | Provides the experimental enzyme concentration data (E_j) required to set flux constraints in enzyme-constrained models. |

A Comparative Guide to Stoichiometric and Kinetic Metabolic Modeling

For researchers in systems biology and drug development, selecting the appropriate metabolic modeling framework is crucial. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Kinetic Modeling represent two fundamentally different approaches, each with distinct strengths, data requirements, and output capabilities. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies to inform model selection for specific research objectives.

Core Principles and Outputs: A Quantitative Comparison

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics and outputs of FBA and kinetic models, highlighting their contrasting capabilities.

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Linear programming; constraint-based [25] [26] | Systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) [6] [14] |

| Primary Outputs | Steady-state flux distributions ((v)) [26] | Time-course metabolite concentrations ((C(t))) and fluxes ((v(t))) [6] [14] |

| Temporal Dynamics | No (Steady-state assumption, (\mathbf{S \cdot v = 0})) [25] [26] | Yes (Dynamic simulations of transients) [6] [14] |

| Typical Model Scope | Genome-scale (1,000s of reactions) [6] [1] | Pathway-scale (10s-100s of reactions) [6] [1] |

| Key Data Inputs | Stoichiometric matrix, exchange reaction bounds, objective function [25] | Enzyme kinetics ((Km), (k{cat})), metabolite concentrations, enzyme levels [6] [14] |

| Regulatory Insight | Indirect (via constraints) [27] | Direct (allosteric regulation, feedback inhibition) [6] [14] |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

The reliability of model predictions hinges on robust experimental workflows for data acquisition and rigorous computational protocols for model construction.

Protocol for FBA and Flux Map Validation

Flux Balance Analysis relies on network stoichiometry and optimization, with validation often performed by comparing predictions to independent experimental data.

Workflow: FBA Model Construction and Validation

Detailed Methodologies:

- Model Construction: Genome-scale metabolic models are reconstructed from annotated genomes, defining the stoichiometric matrix S. Environment-specific constraints on uptake and secretion rates are applied as bounds on exchange reactions ((\mathbf{l}(t) \le \mathbf{v} \le \mathbf{u}(t))) [25] [26].

- Objective Function Selection: A biological objective, most commonly biomass maximization, is defined as (\max \, \muj = v{\mathrm{biomass},j}). The linear programming problem is solved to find an optimal flux distribution [25] [26].

- Validation with ¹³C-MFA: The most robust validation involves comparing FBA-predicted internal fluxes against those estimated by ¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA). ¹³C-MFA uses isotopic labeling data from cells fed with ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-¹³C]glucose) to infer intracellular fluxes, providing an independent benchmark for FBA predictions [26]. Statistical tests, like the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, can assess the agreement between model predictions and experimental data [26].

Protocol for Kinetic Model Construction and Parameterization

Kinetic models aim to capture the dynamic behavior of metabolism, a process that requires significant parameterization.

Workflow: Kinetic Model Development

Detailed Methodologies:

- Network and Rate Law Assignment: A targeted metabolic network (e.g., central carbon metabolism) is defined. Each reaction is assigned a kinetic rate law, such as Michaelis-Menten or Hill equations, which describe the reaction rate as a function of metabolite concentrations and enzyme levels [6] [14].

- Parameterization Frameworks: Two modern approaches are widely used:

- SKiMpy: A semi-automated workflow that uses a stoichiometric model as a scaffold, automatically assigns rate laws from a library, and samples kinetic parameter sets consistent with thermodynamic constraints and experimental data [6].

- MASSpy: Built on COBRApy, this framework integrates constraint-based modeling tools to sample steady-state fluxes and concentrations, often using mass-action kinetics, to parametrize the model [6].

- Data Integration and Fitting: Time-resolved metabolomics and proteomics data are integrated. Parameter fitting involves solving an optimization problem to minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental data, refining the initial parameter estimates [6] [14].

- Model Selection and Validation: The model's ability to fit the training data and, more importantly, to predict the metabolic behavior of unseen mutant strains or under new environmental conditions is assessed. Techniques like Bayesian inference can be used to quantify parameter uncertainty [6] [26].

Successful model development and validation depend on key computational tools and databases.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [6] [25] | A Python toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. | Setting up, solving, and analyzing FBA and dFBA problems. |

| SKiMpy [6] | A computational framework for the construction and parametrization of large-scale kinetic models. | Accelerating kinetic model development through efficient parameter sampling. |

| Tellurium [6] | A modeling environment for systems and synthetic biology. | Simulating and analyzing kinetic models defined using standard formats. |

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates [26] | Tracers (e.g., [1,2-¹³C]glucose) for experimental flux determination. | Generating data for ¹³C-MFA to validate FBA predictions or inform kinetic models. |

| Kinetic Parameter Databases [6] | Databases (e.g., BRENDA) of enzyme kinetic parameters ((Km), (k{cat})). | Providing initial parameter estimates for kinetic model construction. |

| LC-MS/MS Platforms | Analytical instruments for quantifying metabolite concentrations and isotopic labeling. | Generating time-resolved metabolomics data for kinetic model fitting and validation. |

The choice between FBA and kinetic modeling is not one of superiority but of appropriateness for the research question.

- Use FBA for genome-scale predictions of steady-state fluxes, such as identifying gene knockout targets for metabolic engineering or simulating growth phenotypes across nutrients. Its strength lies in its scalability and minimal data requirements [25] [26].

- Use kinetic models to understand and predict dynamic and regulatory behaviors, such as metabolite concentration transients, responses to sudden perturbations, or the effects of enzyme inhibition. Their application is critical when moving beyond steady-state assumptions, though it demands significant parametrization effort [6] [14].

Emerging hybrid frameworks, such as TIObjFind [27] and NEXT-FBA [28], seek to combine the scalability of stoichiometric models with the contextual awareness of kinetic and regulatory data, pointing toward a more integrated future for metabolic modeling.

Practical Applications: Choosing the Right Model for Your Research Objective

Stoichiometric and kinetic models represent two powerful computational approaches for modeling metabolic networks, each with distinct strengths and optimal application areas. While kinetic models incorporate enzyme mechanics and metabolite concentrations to predict dynamic system behavior, stoichiometric models rely on reaction stoichiometry, mass balance, and an assumption of steady-state to analyze network capabilities [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of their performance in predicting growth rates, identifying gene knockouts, and calculating theoretical yields to inform model selection in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Stoichiometric models, particularly Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs), map the entire metabolic network of an organism using a stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [29] [30]. The core principle is the steady-state mass balance equation: S · v = 0, where v is the vector of reaction fluxes [29]. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based optimization method, is then used to predict physiological states, often by maximizing an objective function such as biomass production [29] [30].

Kinetic models, in contrast, employ differential equations to describe the dynamics of metabolite concentrations as a function of time, incorporating detailed enzyme kinetic parameters like kcat and Km [1]. This makes them more biochemically detailed but also more parameter-intensive and difficult to scale.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and decision points for employing each modeling approach.

Performance Comparison: Stoichiometric vs. Kinetic Models

The choice between stoichiometric and kinetic models involves a fundamental trade-off between scope and mechanistic detail. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and performance across key tasks.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of stoichiometric and kinetic metabolic models

| Feature | Stoichiometric Models | Kinetic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Reaction stoichiometry, mass balance, steady-state assumption [29] | Enzyme kinetics, metabolite concentrations, differential equations [1] |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (thousands of reactions) [1] [30] | Pathway-scale (tens of reactions) [1] |

| Primary Output | Metabolic flux distribution | Dynamic changes in metabolite concentrations and fluxes |

| Growth Rate Prediction | Quantitative predictions of maximal growth possible; validated with experimental data [31] [30] | Possible but limited to small-scale networks; can simulate transient growth |

| Knockout Prediction | High efficacy; used to identify drug targets and engineer strains [32] [30] | Possible but limited by network size and parameter availability |

| Theoretical Yield | Directly calculated as a constraint-based optimization problem | Can be inferred from simulated steady-state fluxes |

| Key Advantage | Applicable to large networks without needing kinetic parameters | Provides dynamic and concentration-level insight |

| Major Limitation | Cannot predict metabolite concentrations or transients | Difficult to construct for large networks due to missing parameters |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Predicting Growth Rates with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

FBA is a standard methodology used with stoichiometric models to predict growth rates under different environmental or genetic conditions.

- Model Construction: Reconstruct or obtain a genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM) for the target organism, represented by the stoichiometric matrix S [29] [30].

- Constraint Definition: Define constraints for exchange fluxes (e.g., glucose uptake = 10 mmol/gDW/h) and reaction reversibility/irreversibility [31] [1].

- Objective Function: Set the objective function, typically the biomass reaction, to be maximized.

- Linear Programming: Solve the linear programming problem: maximize c(^Tv (biomass production) subject to S · v = 0 and lower/upper flux bounds [29].

- Validation: Compare the predicted growth rate with experimentally measured values from chemostat or batch cultures [31].

Protocol 2: Identifying Gene Knockouts using cMCS and Optimization Algorithms

Constrained Minimal Cut Sets (cMCSs) represent a powerful approach to compute intervention strategies that block undesired metabolic functions (e.g., low product yield) while maintaining desired functions (e.g., cell growth) [32].

- Problem Formulation: Define the undesired flux space (e.g., low product yield) and the desired flux space (e.g., high growth rate) using constraints Tr ≤ t and Dr ≤ d, respectively [32].

- Dual Network Calculation: Transform the problem using the dual metabolic network to enable direct computation of cMCS from the stoichiometric matrix [32].

- Optimization: Solve a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem to find the minimal set of reaction knockouts (cMCS) that satisfy the design constraints. Advanced optimization algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) can be integrated to efficiently find optimal designs satisfying multiple objectives [32].

- In silico Validation: Simulate the knockout strain using FBA to verify the predicted phenotype, such as reduced growth of cancer cells or enhanced product synthesis [30].

Research Reagent and Computational Solutions

The following toolkit is essential for researchers conducting metabolic modeling studies.

Table 2: Essential research toolkit for metabolic modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [30] | Performing FBA, pFBA, and gene knockout simulations in GSMMs |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical representation of the metabolic network [29] | The foundational input for all stoichiometric model analyses |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A metaheuristic algorithm for solving complex non-linear optimization problems [32] | Identifying optimal knockout strategies in large metabolic networks |

| MOMA | Algorithm to predict the metabolic state after a gene knockout [30] | Simulating the flux distribution in engineered or diseased cells |

| Chemostat Culture | A controlled bioreactor system for steady-state cell growth [31] | Experimentally measuring maximum substrate uptake rates and growth parameters for model validation |

| Genome Annotation Database | Provides gene-protein-reaction associations for network reconstruction | Building and curating genome-scale metabolic models |

Stoichiometric and kinetic models are complementary tools. Stoichiometric models are the preferred choice for genome-scale analyses, including predicting growth rates under various conditions, identifying genome-wide knockout strategies for metabolic engineering or drug target discovery [32] [30], and calculating maximum theoretical yields. Their reliance on stoichiometric constraints and optimization makes them uniquely powerful for these tasks without requiring difficult-to-obtain kinetic parameters. Kinetic models are indispensable when dynamic and concentration-level insights are required, but their application is confined to well-characterized, smaller pathways [1]. The informed selection between these models, and sometimes their synergistic use [1], is fundamental to advancing metabolic research and biotechnology.

In the realm of metabolic modeling, researchers primarily leverage two mathematical frameworks: stoichiometric (constraint-based) models and kinetic (dynamic) models. While stoichiometric models, such as those used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have become a cornerstone for predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes, they lack explicit information about enzyme kinetics and regulation [33]. Kinetic models, formulated as systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), dynamically link metabolite concentrations, metabolic fluxes, and enzyme levels through mechanistic relationships [34] [6]. This capability makes them uniquely suited for investigating scenarios where the steady-state assumption breaks down or where understanding temporal evolution is critical. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on three specific application areas where kinetic models offer distinct advantages: predicting metabolic states, analyzing non-growth physiologies, and evaluating metabolic stability.

Comparative Analysis: Application-Based Performance

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of kinetic and stoichiometric models across key application domains relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Kinetic vs. Stoichiometric Metabolic Models

| Application Domain | Kinetic Models | Stoichiometric Models (e.g., FBA) |

|---|---|---|

| State Prediction (Dynamic) | Predict time-course metabolite & flux changes [34] | Limited to steady-state predictions; cannot capture transients [33] |

| Non-Growth Physiology | Explicitly models metabolite conc., enabling non-growth studies [35] | Typically requires a biomass objective; less suited for non-growth states |

| Metabolic Stability Analysis | Linear stability analysis (Jacobian eigenvalues) assesses robustness to perturbation [8] | Cannot assess dynamic stability; assumes a steady-state exists |

| Regulatory Mechanism Insight | Captures allosteric regulation, feedback inhibition via kinetic rate laws [6] | Requires imposition as external constraints |

| Data Integration | Directly integrates multi-omics (metabolomics, fluxomics, proteomics) into ODEs [34] | Uses inequality constraints to loosely couple different data types [34] |

| Parameter Requirements | High: Requires kinetic parameters (e.g., KM, Vmax) [34] | Low: Requires only stoichiometry and uptake/secretion rates |

| Computational Cost | High (Non-linear ODE integration, parameter estimation) [6] | Low (Linear/Convex optimization) |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Modeling

Protocol 1: Generative Machine Learning for Model Parameterization

Objective: To efficiently parameterize large-scale kinetic models whose dynamic properties match experimental observations, overcoming traditional challenges of low yield of valid models [34] [8].

- Input Data Preparation: Integrate structural and experimental data into a stoichiometric model scaffold. This includes the reaction network (stoichiometry), regulatory structure, and available multi-omics data (e.g., metabolomics, fluxomics, thermodynamics, proteomics) to compute steady-state profiles of metabolite concentrations and fluxes [34].

- Generator Network Setup: Initialize a population of feed-forward neural networks (generators). The complexity of these networks is dictated by the size of the kinetic model to be parameterized [34].

- Iterative Model Generation & Evaluation:

- Step I: Each generator produces a batch of kinetic parameter sets from multivariate Gaussian noise [34].

- Step II: These parameters are used to instantiate a kinetic model [34].

- Step III: The dynamics of each model are evaluated by computing the eigenvalues of its Jacobian matrix. A model is considered valid if its dominant time constant aligns with experimental observation (e.g., a doubling time of 134 min for E. coli corresponds to a dominant eigenvalue λmax < -2.5) [34].

- Step IV: Generators are rewarded based on the incidence of valid models they produce. The population of generators is updated using Natural Evolution Strategies (NES), mutating high-performing generators to create the next generation [34].

- Validation: The process iterates until a generator meets a design objective (e.g., >92% incidence of valid models). The output is a population of parameterized, large-scale kinetic models ready for dynamic studies [34].

Diagram 1: REKINDLE/RENAISSANCE machine learning workflow for kinetic model generation.

Protocol 2: Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) for Engineering Decisions

Objective: To identify enzymes with the strongest control over metabolic fluxes and concentrations, guiding targeted metabolic engineering [35].

- Model Construction: Build a population of large-scale kinetic models that are consistent with an observed physiology (e.g., optimal growth of E. coli). It is critical to account for alternative steady-state solutions in the model construction, as different flux/concentration profiles can satisfy the same physiology [35].

- Perturbation Simulation: Systematically perturb the activity of each enzyme in the network (e.g., by varying its concentration or kinetic parameters) and simulate the kinetic model to compute the new steady-state [35].

- Control Coefficient Calculation: Calculate flux control coefficients (FCCs) and concentration control coefficients (CCCs). These coefficients quantify the fractional change in a flux or metabolite concentration in response to a fractional change in enzyme activity [35].

- Robustness Analysis: Perform MCA across the entire population of models representing alternative steady states. This analysis reveals which control coefficients are robust (consistent across all models) and which are sensitive to the underlying uncertainty in fluxes and concentrations [35].

- Decision Making: Prioritize engineering targets (e.g., enzyme overexpression or knockdown) based on control coefficients that are both large in magnitude and robust across the model population. Studies indicate that MCA-based decisions are more sensitive to uncertainties in metabolite concentrations than fluxes [35].

Visualization of Logical Workflows

Kinetic Model Application Decision Pathway

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate modeling approach based on the biological question, highlighting the specific use cases where kinetic models are indispensable.

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for selecting kinetic versus stoichiometric models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below lists essential computational tools, databases, and methodologies that form the foundation of modern kinetic modeling research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Kinetic Modeling

| Tool/Reagent Name | Type | Primary Function in Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| REKINDLE/RENAISSANCE [34] [8] | Generative ML Framework | Efficiently parameterizes large-scale kinetic models with desired dynamic properties, drastically reducing computational time. |

| SKiMpy [6] | Modeling Workflow | Semiautomated construction of kinetic models using stoichiometric models as a scaffold; samples kinetic parameters. |

| ORACLE [8] | Modeling Framework | Generates populations of kinetic models consistent with thermodynamics and experimental data. |

| BRENDA Database [33] | Kinetic Parameter Database | Curated repository of enzyme kinetic data (e.g., KM, kcat values) used to inform model parameters. |

| ECMpy [33] | Software Workflow | Adds enzyme constraints to genome-scale models, improving flux predictions by capping fluxes based on enzyme availability and catalytic efficiency. |

| Tellurium [6] | Software Tool | A versatile modeling environment for systems and synthetic biology, supporting simulation, parameter estimation, and visualization. |

| MASSpy [6] | Software Tool | A framework for building and simulating kinetic models, well-integrated with constraint-based modeling tools (COBRApy). |

| Thermodynamic Constraints [35] [6] | Modeling Principle | Ensures model consistency with the second law of thermodynamics, coupling reaction directionality with metabolite concentrations. |

| Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) [35] | Analytical Method | Quantifies the control exerted by individual enzymes over system variables like fluxes and metabolite concentrations. |

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) represents a cornerstone computational approach in systems biology for predicting metabolic flux distributions within biochemical networks. By applying conservation principles to stoichiometric models of metabolism, FBA calculates optimal metabolic flux distributions that align with specific cellular objectives, typically maximizing biomass production or metabolite synthesis [36]. Unlike kinetic models that simulate metabolite concentrations and flux changes over time using detailed enzyme parameters, stoichiometric models like those used in FBA focus on analyzing feasible steady states based primarily on reaction stoichiometry, flux bounds, and directionality constraints [1]. This fundamental difference makes stoichiometric modeling particularly suitable for genome-scale analyses where comprehensive kinetic parameter data remains limited, though it comes at the cost of temporal resolution and concentration predictions [1].

The evolution of FBA has progressed from basic optimization frameworks to sophisticated methodologies that integrate diverse biological data and contextual constraints. This progression addresses a critical challenge in metabolic modeling: selecting appropriate objective functions that accurately represent system performance across different biological contexts and conditions [36] [37]. As research extends beyond microbial systems to complex multicellular eukaryotes like plants and mammals, including specialized applications in cancer metabolism [38] [39], the extensions of FBA have become increasingly important for bridging the gap between model predictions and experimental observations.

Comparative Analysis of FBA Extensions

Table 1: Comparison of Major FBA Extension Methodologies

| Method | Core Innovation | Experimental Validation | Key Application Context | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind [36] [37] | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to determine Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Case studies on Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and multi-species IBE system | Identifying metabolic objective functions; analyzing adaptive shifts in cellular responses | Improved alignment with experimental flux data; enhanced interpretability of complex networks |

| Gene Expression-Weighted FBA [40] [41] | Incorporates relative gene expression levels between tissues as penalty weights in parsimonious FBA | 13C-MFA flux maps in Arabidopsis thaliana rosette leaf central metabolism | Multi-tissue plant metabolic modeling; central metabolism under varying light conditions | Reduced prediction error from 169-180% to 10-13% in high light; 94-103% to 9-11% in low light |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [42] | Machine learning framework using Monte Carlo sampling of metabolic space geometry | Gene essentiality predictions in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and CHO cells | Predicting metabolic gene deletion phenotypes; small molecule production | 95% accuracy for E. coli gene essentiality (vs. 93.5% with FBA); improved nonessential (1%) and essential (6%) gene classification |

| OptKnock [40] | Bilevel programming framework for identifying gene knockout strategies | Microbial strain optimization for metabolite overproduction | Biotechnological strain design; identifying gene knockouts for chemical production | Not quantitatively specified in available literature |

| Regulatory FBA (rFBA) [43] | Integrates Boolean logic-based regulatory rules with FBA constraints | Limited benchmark data against experimental flux maps | Context-specific modeling incorporating gene regulation | Performance heavily dependent on quality and quantity of gene expression data |

Table 2: Technical Implementation Characteristics of FBA Extensions

| Method | Software Availability | Computational Requirements | Data Integration Capabilities | Multi-Tissue Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | MATLAB implementation available via GitHub [37] | Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for computational efficiency | Experimental flux data; network topology | Limited (demonstrated in multi-species system) |

| Gene Expression-Weighted FBA | Python code available via GitHub [40] [41] | Standard linear programming with added weight constraints | Transcriptomic and proteomic data; 13C-MFA flux maps | Yes (native multi-tissue support) |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | Not specified (custom implementation) | High (Monte Carlo sampling + machine learning training) | Gene essentiality screens; phenotypic fitness data | Limited (primarily single-cell organisms) |

| OptKnock | COBRA Toolbox implementations | Bilevel optimization challenges | Genome-scale metabolic models | No |

| Regulatory FBA (rFBA) | Multiple implementations (PROM, PROM2.0, TRFBA) [43] | Varies by implementation | Gene regulatory networks; expression data | Limited |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Tissue-Specific Gene Expression Integration

The integration of gene expression data into FBA represents a significant advance for improving prediction accuracy in complex multicellular systems. The experimental protocol for implementing gene expression-weighted FBA involves several key stages [40]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collect transcriptomic or proteomic datasets from multiple tissues or conditions. Calculate relative expression levels between tissues for genes associated with metabolic reactions through Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) mappings.

Weight Calculation: For each reaction in the metabolic network, calculate a penalty weight coefficient (cj) derived from the relative expression of genes encoding the enzyme(s) that catalyze that reaction. Reactions mapped to highly expressed genes receive small cj values, while those mapped to minimally expressed genes receive large values.

Model Optimization: Solve the modified parsimonious FBA problem that minimizes the weighted sum of fluxes: min∑j∈Reactionscj*vj, where vj represents the flux through reaction j. This formulation maintains the steady-state constraint Sv=0 while incorporating expression-based penalties.

Validation Against Experimental Flux Maps: Compare predicted flux distributions with experimentally determined fluxes from 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). Calculate weighted average percent error to quantify agreement between predictions and experimental measurements.

This methodology dramatically improved agreement with experimental flux maps in Arabidopsis thaliana, reducing prediction errors from 169-180% to 10-13% under high light conditions and from 94-103% to 9-11% under low light conditions compared to standard parsimonious FBA [40].

TIObjFind Framework Implementation

The TIObjFind framework introduces a topology-informed approach to objective function identification through a structured multi-step process [37]:

Problem Formulation: Reformulate objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal.

Mass Flow Graph Construction: Map FBA solutions onto a flux-dependent weighted reaction graph (Mass Flow Graph) that enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions.

Minimum-Cut Algorithm Application: Apply graph theory algorithms (Boykov-Kolmogorov minimum-cut) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization.

Pathway-Centric Analysis: Focus analysis on specific pathways rather than the entire network by defining start reactions (e.g., glucose uptake) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion) to enhance interpretability of dense metabolic networks.

This framework has demonstrated effectiveness in capturing stage-specific metabolic objectives in biological systems such as Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation, where it successfully identified shifting metabolic priorities across different fermentation stages [37].

Flux Cone Learning for Phenotype Prediction

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) represents a paradigm shift from optimization-based to machine learning-based metabolic phenotype prediction. The experimental workflow comprises [42]:

Feature Generation via Monte Carlo Sampling: For each gene deletion, generate multiple random flux samples (typically 100-5000) from the corresponding metabolic space (flux cone) using Monte Carlo sampling techniques.

Training Data Assembly: Construct a feature matrix with k×q rows and n columns, where k is the number of gene deletions, q is the number of flux samples per deletion cone, and n is the number of reactions in the GEM. Assign fitness labels from experimental deletion screens to all samples from the same deletion cone.

Supervised Learning: Train machine learning models (random forest classifiers shown to be effective) on the flux sample data to predict phenotypic outcomes from metabolic space geometry.

Prediction Aggregation: Apply majority voting across sample-wise predictions to generate deletion-wise phenotypic predictions.

This approach achieved 95% accuracy in predicting metabolic gene essentiality in Escherichia coli, outperforming FBA predictions, and demonstrated particular strength in identifying nonessential and essential genes with 1% and 6% improvements respectively [42].

Visualization of Method Workflows

Graph 1: Workflow for gene expression-weighted FBA methodology. The diagram illustrates the sequential process of integrating transcriptomic/proteomic data with metabolic models to improve flux prediction accuracy.

Graph 2: TIObjFind framework workflow. This topology-informed approach identifies key metabolic pathways and calculates Coefficients of Importance to infer biological objective functions from experimental data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Advanced FBA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Libraries | COBRApy [39] | Python package for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Open-source |

| COBRA Toolbox [39] | MATLAB implementation of constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | MATLAB-based | |

| memote [39] | Model testing and quality assurance for genome-scale metabolic models | Open-source | |

| Data Resources | BiGG Models [39] | Database of curated genome-scale metabolic models | Publicly accessible |

| KEGG [37] | Reference database of biological pathways and genomic information | Subscription-based | |

| EcoCyc [37] | Encyclopedia of E. coli genes and metabolism | Publicly accessible | |

| Experimental Validation | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [40] | Experimental technique for determining intracellular metabolic fluxes | Specialized equipment required |

| CRISPR-Cas9 deletion screens [42] | High-throughput gene essentiality determination | Specialized expertise required | |

| Sampling & ML | Monte Carlo Samplers [42] | Generate random flux samples from metabolic space | Custom implementation |

| Random Forest Classifiers [42] | Machine learning for phenotype prediction from flux samples | Multiple open-source implementations |

Discussion: FBA in the Context of Kinetic vs. Stoichiometric Modeling

The extensions of FBA highlighted in this analysis demonstrate the evolving capacity of stoichiometric modeling to address one of its fundamental limitations: the need for appropriate cellular objective functions. While kinetic models explicitly incorporate enzyme mechanisms, metabolite concentrations, and temporal dynamics [1], they face significant challenges in scaling to genome-wide analyses due to the immense parameterization requirements. Stoichiometric approaches like FBA and its extensions sacrifice temporal resolution and concentration predictions to enable system-wide analyses with more limited parameter needs.

The integration of additional constraints represents a convergence point between kinetic and stoichiometric modeling philosophies. Methods like TIObjFind and expression-weighted FBA incorporate biological context through topology-aware weighting and multi-omics integration, effectively constraining the solution space in biologically meaningful ways [36] [40] [37]. Similarly, the application of machine learning in Flux Cone Learning demonstrates how patterns in metabolic space geometry can predict phenotypes without explicit optimality assumptions [42], potentially bridging conceptual gaps between mechanistic and data-driven modeling approaches.

For cancer metabolism and therapeutic development, these advanced FBA techniques offer promising avenues for identifying metabolic vulnerabilities. The recognition that different cell types, including cancer cells, exhibit objectives beyond biomass maximization - such as supporting tissue functions, developmental processes, and redox homeostasis [38] - necessitates more nuanced modeling approaches. Context-specific FBA extensions that incorporate tissue-specific gene expression, regulatory constraints, and metabolic objectives particular to different cancer types hold significant potential for identifying novel therapeutic targets.