Inverse Metabolic Engineering and Metabolic Control Analysis: A Synergistic Framework for Advanced Bioproduction and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the synergistic relationship between inverse metabolic engineering (IME) and metabolic control analysis (MCA) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Inverse Metabolic Engineering and Metabolic Control Analysis: A Synergistic Framework for Advanced Bioproduction and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the synergistic relationship between inverse metabolic engineering (IME) and metabolic control analysis (MCA) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing how IME identifies key genetic targets through phenotypic screening while MCA quantifies control distribution in metabolic networks. The content covers advanced combinatorial methodologies, 'omics' integration, and computational frameworks for troubleshooting pathway bottlenecks. Through comparative case studies across microbial and plant systems, it validates the combined power of these strategies for optimizing the production of high-value pharmaceuticals and biofuels, concluding with future directions in multi-targeted therapy and AI-driven strain design.

Core Principles: From Single Rate-Limiting Steps to Distributed Metabolic Control

Inverse metabolic engineering (IME) represents a fundamental shift in the approach to strain and cell line development for biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications. Unlike classical metabolic engineering, which begins with a predetermined genetic target, IME first identifies, constructs, or calculates a desired phenotype, then determines the genetic or environmental factors conferring that phenotype, and finally endows that phenotype on another strain or organism through directed genetic or environmental manipulation [1]. This phenotype-first approach has demonstrated remarkable success in contexts ranging from eliminating growth factor requirements in mammalian cell culture to increasing the energetic efficiency of microaerobic bacterial respiration [1]. The paradigm is particularly valuable when engineering products like recombinant proteins that are intricately coupled to the growth process, where identifying beneficial genetic manipulations through direct approaches would be challenging [2].

The limitations of classical metabolic engineering approaches provide the necessary context for understanding IME's emergence. Traditional methods often focused on identifying a presumed rate-determining step in a pathway and alleviating this bottleneck through enzyme overexpression [1] [3]. However, this direct approach frequently encountered confounding factors such as intervention of other limiting steps, counter-balancing regulation, and unknown coupled pathways [1]. Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) subsequently demonstrated that control of metabolic flux is typically distributed across multiple enzymes rather than residing in a single "rate-limiting step" [3]. This theoretical foundation explains why inverse approaches, which let the cellular system reveal which modifications yield the desired phenotype, often prove more successful than predetermined interventions.

Core Principles and Comparative Framework

Conceptual Foundation and Definitions

Inverse metabolic engineering operates on three fundamental principles that distinguish it from forward engineering approaches. First, it is phenotype-driven, meaning the desired cellular performance characteristic is defined before any genetic manipulation is considered. Second, it employs comparative analysis between strains or conditions to identify genetic basis for superior performance. Third, it utilizes directed genotype implementation to transfer identified beneficial traits to production hosts [1] [2].

The conceptual framework can be formally described as a three-step process:

- Identification of a desired phenotype through screening, construction, or computational design

- Determination of genetic/environmental basis through omics analysis, library screening, or other discovery methods

- Implementation in target host through genetic engineering or environmental optimization

Comparative Analysis: Inverse vs. Classical Metabolic Engineering

Table 1: Comparison between Classical and Inverse Metabolic Engineering Approaches

| Feature | Classical Metabolic Engineering | Inverse Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Known genetic target | Desired phenotype |

| Knowledge Requirement | Complete pathway understanding | Can work with partial knowledge |

| Control Assumption | Single rate-limiting step | Distributed control [3] |

| Approach to Complexity | Targeted manipulation | Systems-level analysis |

| Success Rate | Limited by preconceptions | Higher for complex phenotypes |

| Primary Applications | Simple pathway modifications | Complex trait engineering [2] |

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Core Workflow and Implementation Strategies

The implementation of inverse metabolic engineering follows a structured workflow that can be adapted to various biological systems and desired phenotypes. The following diagram illustrates the core iterative process:

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Library-Based Screening for Recombinant Protein Production

The following protocol, adapted from a study on E. coli strain improvement, demonstrates a practical implementation of IME for enhancing recombinant protein yields [2]:

Phase 1: Library Construction

- Genomic DNA Fragmentation: Partially digest E. coli genomic DNA to obtain fragments ranging from 200-800 bp using restriction enzymes with appropriate recognition sites.

- Vector Preparation: Prepare expression vectors (e.g., pRSET A with strong T7 promoter or pBAD33 with weaker arabinose promoter) by digestion with compatible restriction enzymes and dephosphorylation to prevent self-ligation.

- Ligation and Transformation: Ligate genomic fragments into prepared vectors and transform into appropriate host strain (E. coli BL21 pLysS for pRSET constructs). Plate transformants on selective media and incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Library Quality Assessment: Pick random colonies to verify insert size distribution by colony PCR and ensure library diversity exceeds 8,000 independent clones.

Phase 2: Phenotypic Screening

- Primary Screening for Growth Phenotype: Replica plate library clones onto induction plates containing IPTG (1 mM) or arabinose (0.2%). Identify clones showing significantly reduced growth post-induction compared to non-induced controls.

- Secondary Metabolic Activity Screening: Inoculate selected slow-growing clones into M9 minimal medium with glucose (0.4%) and allow growth to mid-log phase. Induce with appropriate inducer and monitor glucose consumption rates, selecting clones with unimpaired metabolic activity despite growth retardation.

- Tertiary Product Screening: Transform selected clones with reporter plasmid (e.g., GFP expression vector). Measure specific product yields (mg product/g DCW) post-induction, selecting clones with enhanced production capabilities.

Phase 3: Target Identification and Validation

- Insert Sequencing: Isolate plasmid DNA from superior producers and sequence inserted fragments using vector-specific primers.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform BLAST search against host genome database to identify silenced genes and pathway context.

- Confirmation Studies: Construct defined knockdowns or knockouts of identified targets and validate phenotype reproduction in fresh genetic background.

Table 2: Key Genetic Targets Identified Through IME for Recombinant Protein Production

| Gene Target | Gene Function | Effect on Specific Product Yield | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| ribB | 3,4 dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase | 7-fold increase | Redirects metabolic flux from growth to product synthesis [2] |

| kdpD | Sensory histidine kinase | 3.2-fold increase | Alters global regulation and stress response [2] |

| cysN | Sulfate adenylyltransferase subunit 1 | Significant improvement | Modifies cofactor availability and redox balance [2] |

| aroC | Chorismate synthase | Enhanced production | Shifts aromatic amino acid precursors [2] |

Integration with Metabolic Control Analysis

Theoretical Foundations and Complementarity

Inverse metabolic engineering and Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) share a fundamental recognition that metabolic control is distributed across multiple pathway steps rather than residing in a single rate-limiting enzyme [3]. MCA provides the theoretical framework quantifying how enzymes exert control over fluxes and metabolite concentrations through flux control coefficients (CEJ) and concentration control coefficients [3] [4]. IME operates as the experimental implementation framework that leverages this distributed control principle by allowing the cellular system to reveal which modifications actually impact the desired phenotype.

The power of combining these approaches lies in their complementary strengths. MCA enables quantitative prediction of how perturbations will affect system behavior, while IME provides empirical validation and can identify non-intuitive targets that would be missed through purely rational design. This synergy is particularly valuable for understanding why traditional approaches of overexpressing presumed rate-limiting enzymes often fail – these enzymes typically have low flux control coefficients, and IME can identify the steps with higher control coefficients for the desired phenotype [3].

Advanced MCA Methodologies for IME Support

Modern MCA methodologies provide sophisticated tools to support IME campaigns:

Control Coefficient Determination in Intact Systems: Methodologies exist for determining control coefficients in intact metabolic systems without enzyme purification through co-response analysis of steady-state variables [4]. When metabolic fluxes and intermediate concentrations are measured in response to perturbations, the co-response coefficients (slopes when plotting logarithm of one variable against another) can be transformed through matrix operations to yield complete elasticity and control coefficient matrices [4].

Metabolic Control Analysis under Uncertainty: Computational frameworks employing Monte Carlo sampling procedures simulate uncertainty in kinetic data and apply statistical tools for identifying rate-limiting steps in metabolic networks [5]. This approach is particularly valuable for IME as it allows interpretation and prediction of metabolic network responses to genetic changes while accounting for parameter uncertainty.

Flux-Dependent Graph Analysis: Novel network constructions like Flux-Dependent Graphs (FDGs) and Mass Flow Graphs (MFGs) incorporate directional flow information and environmental context into metabolic network analysis [6]. These graphs capture how metabolic connectivity changes under different conditions, providing insights into which modifications might enhance specific fluxes.

Computational and Analytical Tools

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in IME Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Construction | pRSET A, pBAD33 vectors, E. coli BL21 pLysS | Generation of antisense libraries for partial gene silencing | Vectors with different promoter strengths enable tuning knockdown level [2] |

| Pathway Analysis | Metabolic Control Analysis, Flux Balance Analysis | Quantifying control coefficients and predicting flux distributions | Essential for interpreting IME results and identifying non-intuitive targets [3] [6] |

| Network Modeling | RuleBender, BioNetGen | Rule-based modeling of signaling and metabolic networks | Handles combinatorial complexity of metabolic systems [7] |

| Flux Analysis | Mass Flow Graphs, Normalised Flow Graphs | Context-specific metabolic network analysis | Reveals environment-dependent pathway importance [6] |

| Pathway Design | Retro-biosynthetic tools, Graph search algorithms | Designing novel metabolic pathways | Expands possible phenotypes for IME targeting [8] |

Computational Pathway Design and Analysis

Computational tools for metabolic pathway design have become essential components of the IME toolkit, enabling more systematic identification of potential metabolic interventions. These tools can be categorized based on their underlying algorithms:

Graph-Based Approaches: These methods represent metabolic networks as graphs with metabolites as nodes and reactions as edges (or vice versa). Search algorithms then identify possible pathways between target compounds and starting metabolites. These approaches benefit from intuitive representation but may generate biologically infeasible pathways without additional constraints [8].

Stoichiometric Matrix-Based Approaches: Utilizing flux balance analysis (FBA) and constraint-based modeling, these methods operate on the stoichiometric matrix of metabolic networks. They can predict optimal flux distributions for desired phenotypes and identify essential genes or reactions. These approaches incorporate mass balance constraints but require objective function definition [6] [8].

Retrosynthetic Search Algorithms: Inspired by organic chemistry retrosynthesis, these methods work backward from the target compound to identify plausible biosynthetic routes. They excel at discovering novel pathways but may require additional filtering for biological relevance [8].

The integration of these computational approaches with IME creates a powerful cycle: computational tools suggest potential phenotypes and genetic modifications, IME validates these predictions experimentally, and the resulting data refines the computational models.

Applications in Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Development

Pharmaceutical and Bioprocessing Applications

IME has demonstrated particular value in pharmaceutical applications where complex phenotypes are required. A prominent example is the engineering of quiescent cells for recombinant protein production – non-growing but metabolically active cells that divert metabolic fluxes toward product formation rather than growth [2]. This application exemplifies how IME can identify non-intuitive targets that decouple growth and production, a longstanding challenge in biotechnology.

In biopharmaceutical development, IME approaches have been applied to enhance production of therapeutic proteins, antibiotics, and other complex natural products. The methodology is especially valuable for identifying generic host modifications that improve production across multiple products, such as engineering chaperone systems to enhance protein folding, modifying transcriptional/translational machinery, or altering central metabolism to increase precursor supply [2].

Environmental and Sustainability Applications

The principles of IME are increasingly applied in environmental biotechnology for biodetection, bioremediation, and sustainable biomanufacturing [9]. Key applications include:

Biosensor Development: IME approaches enable creation of microbial biosensors for environmental pollutants by identifying and implementing genetic elements that confer detection capabilities. For example, transcription factors that respond to heavy metals or organic pollutants can be coupled to reporter systems for sensitive detection [9].

Bioremediation Strain Development: Microorganisms with enhanced capabilities to degrade environmental contaminants can be developed through IME by first identifying desired detoxification phenotypes, then determining the genetic basis in naturally occurring strains, and finally implementing these capabilities in robust industrial hosts [9].

Waste Valorization: IME facilitates engineering of strains that convert waste streams (agricultural residues, plastic waste, C1 compounds) into valuable chemicals, supporting circular economy approaches [9].

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

The future development of inverse metabolic engineering is likely to be shaped by several converging technological trends. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with high-throughput experimental data will enhance pattern recognition in phenotypic screens and enable more accurate prediction of genetic determinants [10]. The expanding toolkit of genome editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-based systems, will facilitate more precise implementation of identified modifications. Additionally, the continued development of multi-omics analytical methods will provide richer data for determining the genetic basis of desirable phenotypes.

The framework of inverse metabolic engineering represents a powerful paradigm for addressing complex metabolic engineering challenges where rational design approaches are insufficient. By allowing the biological system to reveal which modifications yield the desired phenotype, IME bypasses many limitations of incomplete metabolic understanding and distributed control. As computational tools advance and high-throughput experimental methods become more accessible, the application of IME is likely to expand further, accelerating development of improved microbial and cell line platforms for pharmaceutical manufacturing, sustainable chemical production, and environmental applications.

The diagram below illustrates the integrated future of IME combining computational and experimental approaches:

Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) provides a robust mathematical and theoretical framework for describing metabolic, signaling, and genetic pathways, enabling researchers to quantify the control exerted by different components over system variables such as metabolic fluxes and metabolite concentrations [11] [12]. Developed in the 1970s by Kacser and Burns and independently by Heinrich and Rapoport, MCA offers a quantitative alternative to the outdated qualitative concept of a single "rate-limiting step" in biochemical pathways [11] [3]. This framework is particularly valuable in inverse metabolic engineering, where it helps identify non-intuitive genetic targets for optimizing industrial microbial strains when a detailed understanding of pathway regulation is lacking [13] [14].

The power of MCA lies in its ability to deal with systems of any complexity or architecture without requiring all system components to be known a priori, making it an exceptionally valuable post-genomic tool [11]. By integrating local kinetic information with systems-level properties, MCA enables researchers to determine how best to manipulate metabolic pathways for biotechnological applications such as metabolite overproduction or for clinical purposes like drug therapy design [3]. The analysis establishes that control over metabolic fluxes is typically shared among multiple pathway components, fundamentally changing our understanding of metabolic regulation and providing a more accurate basis for rational metabolic engineering strategies [11] [12].

Core Theoretical Principles of Metabolic Control Analysis

Fundamental Coefficients and Their Relationships

MCA quantifies how system variables depend on network parameters through three primary coefficients: control coefficients, elasticity coefficients, and response coefficients [12]. These parameters form the mathematical foundation for understanding and predicting pathway behavior.

Control coefficients measure the systemic response of a pathway to changes in enzyme activity. The flux control coefficient (( C{vi}^{J} )) quantifies the relative change in steady-state pathway flux (( J )) in response to a relative change in the activity of enzyme (( i )), defined as ( C{vi}^{J} = \frac{d \ln J}{d \ln vi} ) [12]. Similarly, the concentration control coefficient (( C{vi}^{S} )) expresses the relative change in metabolite concentration (( S )) in response to the same perturbation: ( C{vi}^{S} = \frac{d \ln S}{d \ln vi} ) [12].

Elasticity coefficients (( \varepsilon )) describe local enzyme properties, quantifying how the rate of an individual enzyme responds to changes in metabolite concentrations, defined as ( \varepsilonS^{vi} = \frac{\partial vi}{\partial S} \times \frac{S}{vi} ) [12]. Unlike control coefficients, which are systemic properties, elasticities are intrinsic to individual enzymes and their kinetic properties.

Response coefficients (( R )) link MCA to practical applications by describing how external factors (such as drugs or nutrients) influence system variables [12]. The response coefficient theorem states that ( Rm^X = Ci^X \varepsilon_m^i ), where ( X ) is a system variable, ( m ) is an external effector, and ( i ) is the target enzyme [12]. This relationship highlights that an external factor's effectiveness depends on both its ability to affect its target (elasticity) and the target's control over the system (control coefficient).

The Summation and Connectivity Theorems

The theoretical foundation of MCA rests on two fundamental theorems that govern the relationships between control coefficients and elasticity coefficients [12].

The summation theorems state that the sum of all flux control coefficients in a pathway equals 1 (( \sumi C{vi}^{J} = 1 )), while the sum of all concentration control coefficients for any metabolite equals 0 (( \sumi C{vi}^{S} = 0 )) [12]. These theorems mathematically formalize the concept of shared flux control, demonstrating that metabolic fluxes are emergent systemic properties rather than being controlled by a single enzyme.

The connectivity theorems establish specific quantitative relationships between control coefficients and elasticity coefficients [12]. For flux control coefficients: ( \sumi Ci^J \varepsilons^i = 0 ). For concentration control coefficients: ( \sumi Ci^{Sn} \varepsilon{Sm}^i = 0 ) when ( n \neq m ), and ( \sumi Ci^{Sn} \varepsilon{S_m}^i = -1 ) when ( n = m ) [12].

Table 1: Key Theorems in Metabolic Control Analysis

| Theorem Type | Mathematical Expression | System Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Flux Summation | ( \sumi C{v_i}^{J} = 1 ) | Control over flux is shared among all pathway steps |

| Concentration Summation | ( \sumi C{v_i}^{S} = 0 ) | Changes in enzyme activities balance metabolite concentrations |

| Flux Connectivity | ( \sumi Ci^J \varepsilon_s^i = 0 ) | Systemic flux control is related to local enzyme sensitivities |

| Concentration Connectivity | ( \sumi Ci^{Sn} \varepsilon{S_m}^i = \begin{cases} 0 & n \neq m \ -1 & n = m \end{cases} ) | Metabolite concentrations are interconnected through enzyme kinetics |

These theorems enable researchers to understand how control is distributed in metabolic networks and provide a mathematical basis for predicting how perturbations will affect system behavior.

Experimental Methodologies for Control Coefficient Determination

Classical Approaches for Flux Control Analysis

Several experimental methodologies have been developed to determine flux control coefficients in metabolic pathways, each with specific applications and limitations. The enzyme titration approach directly modulates enzyme activity through genetic manipulation (overexpression, knockdown) or specific inhibitors, measuring the resulting changes in pathway flux [3]. For example, Niederberger et al. demonstrated that overexpression of four of the five enzymes in the yeast tryptophan biosynthetic pathway was required to significantly increase tryptophan production, illustrating distributed flux control [11].

The inhibitor titration method uses specific, reversible inhibitors to modulate enzyme activity, with the degree of flux inhibition relative to enzyme inhibition indicating the enzyme's flux control coefficient [3]. A hyperbolic inhibition curve suggests high control, while a sigmoidal curve indicates low control. This approach was used to identify GAPDH as having significant flux control in Streptococcus lactis glycolysis using iodoacetate as a specific inhibitor [3].

Top-down control analysis allows researchers to analyze control in complex pathways by grouping reactions into blocks, simplifying the system while retaining essential regulatory features [11]. This approach was successfully applied by Krauss and Brand to quantify contributions of known and unknown signal transduction pathways in thymocyte response to mitogen stimulation, revealing a significant role (30% of total control) for calcineurin signal transduction pathways [11].

Inverse Metabolic Engineering Approaches

Inverse metabolic engineering provides powerful combinatorial methods for identifying control points when rational target selection is challenging. These approaches first generate genetic diversity, then screen for desired phenotypes, and finally identify the genetic modifications responsible [14].

Table 2: Combinatorial Approaches for Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Methodology | Mechanism | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Mutagenesis | Natural mutation accumulation during adaptive evolution | Increased tolerance to isobutanol and ethanol in E. coli; improved xylose utilization in S. cerevisiae [14] |

| Chemical Mutagenesis | Exposure to mutagens (e.g., EMS, NTG) | Enhanced isobutanol and full-length IgG antibody production in E. coli [14] |

| Transposon Mutagenesis | Random gene disruption via mobile genetic elements | Identification of inhibitory genes in lycopene production (E. coli); riboflavin production (B. subtilis) [14] |

| Gene Overexpression Libraries | Systematic overexpression of genomic fragments | Identification of genes enhancing alcohol tolerance and galactose fermentation in S. cerevisiae [14] |

| Coexisting/Coexpressing Genomic Libraries (CoGeLs) | Simultaneous screening of two genomic libraries | Identification of distantly located gene combinations increasing acid resistance in E. coli [14] |

These inverse approaches are particularly valuable for complex phenotypes where multiple genes may interact, such as stress tolerance or the production of compounds through poorly characterized pathways. Once genetic targets are identified through screening, MCA can provide the theoretical framework to understand how these modifications affect flux control distribution.

MCA Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

Elucidation of Biological Design Principles

MCA has fundamentally altered our understanding of metabolic regulation by replacing the concept of a single rate-limiting step with the principle of distributed control [11]. This shift has important implications for metabolic engineering strategies, explaining why overexpressing a single "rate-limiting" enzyme often fails to increase flux, while coordinated expression of multiple pathway enzymes succeeds [11]. For example, in the urea synthetic pathway in rats, eight enzymes increased significantly when urea output rose fourfold in response to dietary protein, demonstrating natural coordination of enzyme expression [11].

The distributed control principle also explains why most mutations in diploid organisms are fully recessive [11]. Since most enzymes have low flux control coefficients, a 50% reduction in enzyme concentration from a null mutation in one allele has minimal effect on pathway flux [11]. This phenomenon was demonstrated in artificial diploids of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where the same extent of recessive mutations occurred without selection pressure [11].

Biotechnological Applications and Case Studies

MCA provides critical guidance for engineering microbial cell factories for bio-production. In a recent application, inverse metabolic engineering based on metabolomics identified cryptic rate-limiting steps in hydroxytyrosol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae [13]. Researchers implemented a three-module engineering strategy: reinforcing the precursor pool, optimizing cofactor supply, and weakening competitive pathways, resulting in a 118.53% titer increase to 639.84 mg/L [13].

The same principles apply to pharmaceutical development, where MCA helps identify optimal drug targets by quantifying how strongly potential targets control flux through essential pathogen pathways [12]. The response coefficient (( Rm^X = Ci^X \varepsilonm^i )) is particularly relevant, showing that drug effectiveness depends on both the drug's ability to inhibit its target (( \varepsilonm^i )) and the target's control over the pathway (( C_i^X )) [12].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of MCA requires specific research reagents and tools that enable precise manipulation and measurement of metabolic systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Control Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Enzyme Inhibitors | Titration of enzyme activity to determine flux control coefficients | Iodoacetate for GAPDH inhibition in glycolytic flux analysis [3] |

| Gene Deletion Collections | Systematic analysis of gene knockout effects on flux | Keio collection (E. coli K-12 knockouts); yeast deletion collection [14] |

| Gene Overexpression Libraries | Identification of limiting steps through systematic gene overexpression | ASKA library (E. coli ORFs); FLEXgene collection (yeast ORFs) [14] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Comprehensive metabolite profiling to identify pathway bottlenecks | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS for differential metabolite analysis [13] |

| Metabolic Engineering Toolkits | Genetic manipulation of pathway enzymes | CRISPR-Cas systems, plasmid vectors for promoter engineering [13] |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Optimization of cofactor supply for redox-balanced production | NADH/FADH2 regeneration modules [13] |

These reagents enable both the theoretical application of MCA principles and the practical implementation of metabolic engineering strategies identified through control analysis.

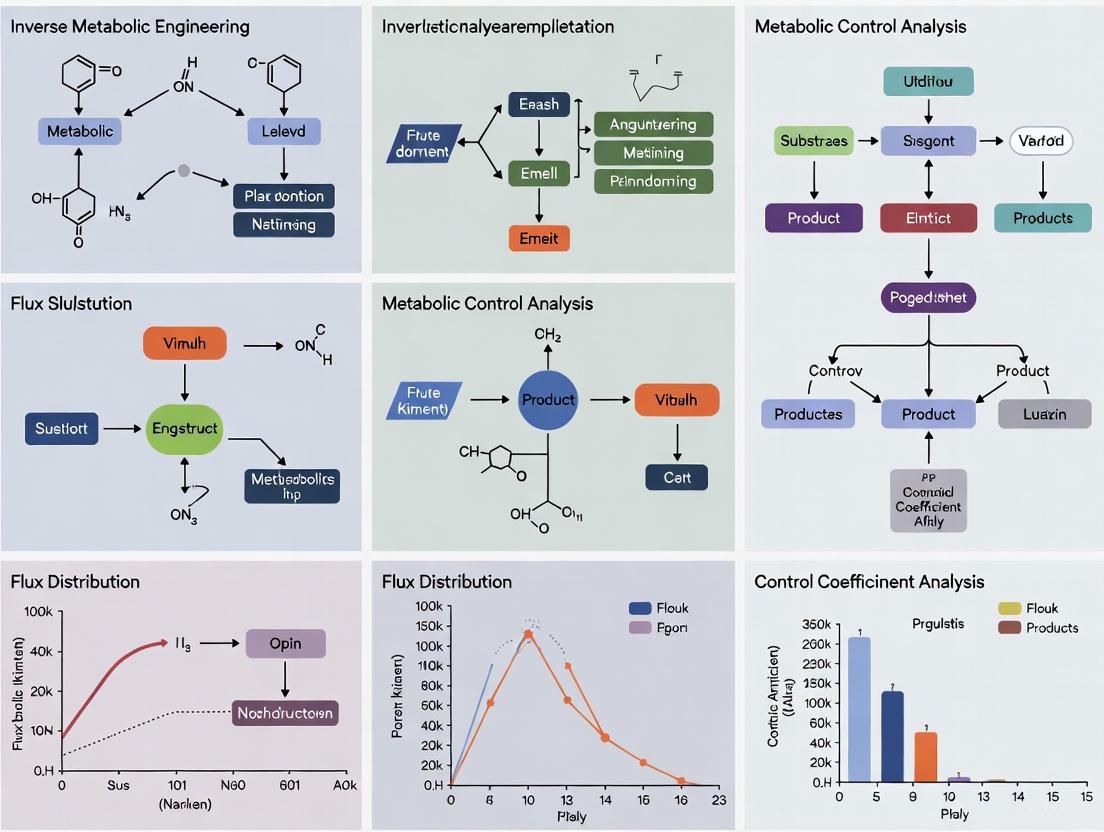

Visualizing Metabolic Control Analysis Concepts and Applications

Theoretical Framework of Metabolic Control Analysis

Diagram 1: Theoretical relationships between MCA coefficients showing how external effectors influence pathway flux through both local enzyme properties and system-level control distribution.

Inverse Metabolic Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Inverse metabolic engineering workflow combining combinatorial approaches for generating genetic diversity with MCA principles for strain improvement.

Modular Engineering Strategy for Metabolite Overproduction

Diagram 3: Modular metabolic engineering strategy based on metabolomics identification of rate-limiting steps, demonstrating how MCA principles guide targeted strain improvement.

For decades, metabolic engineering and drug discovery have been guided by a simplifying principle: identify and target the single rate-limiting enzyme in a pathway to enhance product yield or achieve therapeutic effect. This approach, while intuitively appealing, has proven inadequate for addressing the complex, interconnected nature of cellular metabolism. The failure of prominent single-target inhibitors in advanced clinical trials, such as the IDO1 inhibitor Epacadostat in cancer immunotherapy, starkly illustrates this limitation [15]. The inherent robustness and distributive control of biological networks often enable bypass mechanisms through pathway redundancy or compensatory regulation, leading to diminished efficacy and emergent resistance [16] [17].

This whitepaper examines the paradigm shift toward multi-target intervention strategies and sophisticated network-level analyses that are reshaping metabolic engineering and therapeutic development. Framed within the context of inverse metabolic engineering and Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA), we document the experimental and computational methodologies enabling researchers to move beyond the single rate-limiting enzyme concept toward a more holistic understanding of metabolic control. For researchers and drug development professionals, this represents a fundamental transition from reductionist to systems-level thinking, with profound implications for designing effective metabolic modifications and combination therapies.

Theoretical Foundations: Inverse Metabolic Engineering and Metabolic Control Analysis

Core Principles and Definitions

The theoretical framework for moving beyond single enzymes rests on two complementary approaches:

Inverse Metabolic Engineering: This strategy first identifies a desired phenotype, then determines the genetic or environmental conditions that confer it, and finally engineers those changes into a target host [18]. It is inherently phenotype-driven rather than gene-driven, allowing discovery of non-intuitive multi-gene interventions.

Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA): MCA quantitatively describes how control of metabolic flux is distributed among multiple enzymes in a pathway. It formally demonstrates that control is typically shared, with the degree of control (flux control coefficient) varying with physiological conditions [16].

Inverse Metabolic Control Analysis (IMCA): An extension that uses kinetic models and metabolomics data to identify which enzyme activities need modification to achieve a desired change in metabolic state [16]. IMCA represents a powerful fusion of theoretical and data-driven approaches.

The Network Control Paradigm

The key insight from these frameworks is that metabolic networks exhibit distributive control rather than single-point control. A study applying IMCA to sphingolipid metabolism in yeast found that multiple enzymes—not just the first committed step—significantly influence flux distributions and final product spectra [16]. The analysis revealed that enzymes like D-phospholipase SPO14 played prominent roles in regulating the distribution of sphingolipids among species, findings that would be missed by focusing solely on traditional rate-limiting steps.

Computational Approaches for Network-Level Analysis

Advanced Modeling Frameworks

Table 1: Computational Methods for Multi-Target Metabolic Analysis

| Method | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inverse Metabolic Control Analysis (IMCA) [16] | Identifies enzyme modifications for desired metabolic changes | Integrates kinetic models with lipidomics data; Works with MCA | Pathway-specific engineering; Lipid metabolism |

| Quantitative Heterologous Pathway Design (QHEPath) [19] | Designs heterologous pathways to break stoichiometric yield limits | Uses cross-species metabolic network; Quality-controlled reaction database | 300+ products across 5 industrial organisms |

| Cross-Species Metabolic Network (CSMN) [19] | Provides standardized metabolic reaction database | Incorporates 28,301 reactions from 108 GEMs across 35 species; Automated error elimination | Pan-organism metabolic engineering |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with Machine Learning [20] | Predicts flux distributions in genome-scale models | Integrates multi-omics data; Scalable to multi-tissue/organ models | Context-specific network behavior prediction |

| Dynamic Genome-Scale Models [21] | Simulates transient metabolic behaviors | Uses approximative stochastic simulation; Analyzes reaction profiling over time | Transient behavior under changing conditions |

Workflow for Network Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for identifying multi-target interventions using inverse metabolic engineering principles:

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Inverse Metabolic Engineering Screening

Protocol: Identification of Metabolic Blocks for Enhanced Protein Production [18]

- Step 1: Library Construction - Create an antisense genomic library by cloning 200-800 bp random genomic fragments in reverse orientation under inducible promoters in expression vectors (e.g., pRSET A with T7 promoter).

- Step 2: Phenotypic Screening - Transform library into production host (e.g., E. coli BL21 pLysS) and screen >8000 transformants for slow-growth/no-growth phenotypes upon induction while maintaining metabolic activity.

- Step 3: Functional Validation - Co-transform selected clones with reporter protein plasmid (e.g., pBAD33-GFP) and measure specific product yields under induced vs. non-induced conditions.

- Step 4: Target Identification - Sequence inserts from high-performing clones and map to genomic features. Example: Down-regulation of ribB gene increased specific GFP yields 7-fold.

Quantitative Metabolomics for Dynamic Analysis

Protocol: Stable Isotope Labeled Internal Standards Method (SILIS) [22]

- Step 1: SILIS Preparation - Cultivate E. coli BW25113 on U-13C6-glucose as sole carbon source to generate fully 13C-labeled metabolites for use as internal standards.

- Step 2: Metabolite Extraction - Harvest cells and perform metabolite extraction using methanol:water:chloroform (2:1:2) with 0.1% formic acid.

- Step 3: LC-MS Analysis - Analyze samples using reversed-phase LC-MS with simultaneous detection of 12C (native) and 13C (internal standard) ions.

- Step 4: Absolute Quantification - Calculate metabolite concentrations using the ratio of 12C to 13C peak areas, normalized to internal standard concentration.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Target Metabolic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pRSET A (T7 promoter), pBAD33 (araBAD promoter) [18] | Antisense library construction; Tunable gene expression |

| Stable Isotope Labels | U-13C6-glucose [22] | Metabolic flux analysis; Internal standard preparation |

| Analytical Standards | Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), FeCl₃ [22] | Cofactor supplementation; Enzyme activity assays |

| Inducers | Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), L-Arabinose [18] | Controlled gene induction; Pathway modulation |

| Model Organisms | E. coli BW25113 (Keio Collection base) [22], S. cerevisiae | Well-characterized metabolic models; Genetic manipulation |

Case Studies in Multi-Target Intervention

Metabolic Engineering: Breaking Yield Barriers

The QHEPath algorithm systematically evaluated 12,000 biosynthetic scenarios across 300 products in 5 industrial organisms, revealing that over 70% of product pathway yields could be improved by introducing appropriate heterologous reactions [19]. This study identified thirteen conserved engineering strategies (categorized as carbon-conserving and energy-conserving) effective for breaking stoichiometric yield limits, with five strategies applicable to over 100 different products.

Example: Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) yield in E. coli was enhanced beyond the native network's stoichiometric limit by introducing the heterologous non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) pathway, demonstrating how multi-reaction interventions can overcome theoretical constraints [19].

Therapeutic Development: Dual-Target Inhibitors

Table 3: Representative Dual-Target Inhibitor Approaches

| Target Combination | Therapeutic Area | Rationale | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDO1/TDO2 [15] [17] | Cancer Immunotherapy | Prevents compensatory tryptophan metabolism; Overcomes immunosuppressive TME | Three inhibitors in clinical trials |

| PD-L1/NAMPT [23] | Cancer Immunotherapy | Combines immune checkpoint blockade with metabolic targeting of NAD+ synthesis | Preclinical development |

| PD-L1/HDAC [23] | Cancer Immunotherapy | Epigenetic modulation enhances response to immune checkpoint inhibition | Preclinical development |

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic rationale for dual IDO1/TDO2 inhibition in cancer immunotherapy:

The failure of single-agent IDO1 inhibition in Phase III trials despite promising earlier results has been attributed to compensatory TDO2 upregulation, validating the need for dual targeting approaches [15] [17]. The IDO1/TDO2-KYN-AHR axis creates an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by promoting Treg differentiation and MDSC expansion while suppressing effector T cells and NK cells [17].

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Analytical Hurdles

Implementing multi-target strategies presents several significant challenges:

- Model Quality: Large-scale metabolic models frequently contain errors that must be addressed through automated quality control workflows, such as eliminating infinite energy generation loops in cross-species models [19].

- Experimental Complexity: High-throughput screening requires sophisticated libraries and phenotyping methods, such as the antisense RNA approach for partial gene silencing in prokaryotic systems [18].

- Dynamic Analysis Limitations: Most genome-scale models are designed for steady-state analysis (FBA), with dynamic simulation remaining computationally challenging for large networks [21].

Emerging Solutions and Innovations

Promising approaches are addressing these limitations:

- Automated Model Refinement: New algorithms using parsimonious enzyme usage FBA (pFBA) can iteratively identify and remove reactions causing network errors [19].

- Approximative Stochastic Simulation: δ-leaping methods enable efficient dynamic simulation of genome-scale models by approximating reaction events [21].

- Integrated Tool Platforms: Web servers like QHEPath (https://qhepath.biodesign.ac.cn/) make sophisticated multi-target design accessible to non-specialists [19].

The paradigm shift beyond single rate-limiting enzymes represents a fundamental advancement in metabolic engineering and therapeutic development. By embracing distributive control principles and implementing network-level interventions through inverse metabolic engineering and multi-target strategies, researchers can overcome the limitations that have constrained traditional approaches. The integrated computational and experimental frameworks described in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for designing effective multi-target interventions, whether for industrial biotechnology or pharmaceutical development. As these methodologies continue to mature, they promise to unlock new possibilities for optimizing metabolic networks and developing more robust therapeutic interventions that preempt compensatory resistance mechanisms.

Metabolic engineering aims to systematically optimize cellular metabolism for the production of valuable compounds, yet researchers have historically faced a fundamental challenge: identifying which genetic modifications will yield a desired phenotypic outcome. Two powerful frameworks have emerged to address this challenge—Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) and Inverse Metabolic Engineering (IME)—each with complementary strengths. MCA provides a quantitative theoretical framework for understanding how control is distributed across metabolic networks, moving beyond the outdated concept of a single "rate-limiting step" to recognize that flux control is typically shared among multiple enzymes [3] [24]. In parallel, IME offers a strategic methodology that begins with the identification of a desired phenotype and works backward to elucidate the genetic or environmental factors conferring that phenotype [1]. When integrated, these approaches create a powerful synergy that accelerates the design of engineered microbial strains for biomedical, pharmaceutical, and industrial applications.

The foundational principle of this synergy lies in their complementary approaches to the same problem. MCA quantitatively identifies which enzymes exert the most significant control over metabolic fluxes, while IME provides a practical engineering framework for implementing this knowledge through targeted genetic modifications. For researchers in drug development and therapeutic agent production, this integration offers a more systematic pathway for optimizing microbial factories for pharmaceutical compounds, antibiotic precursors, and therapeutic metabolites. This whitepaper examines the theoretical underpinnings of both frameworks, demonstrates their integrated application through case studies, and provides practical methodologies for implementation in research settings.

Theoretical Foundations

Principles of Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA)

Metabolic Control Analysis provides a quantitative framework for understanding how control is distributed within metabolic networks. Its foundational concept is that control of metabolic flux is typically shared among multiple enzymes rather than residing in a single "rate-limiting step" [3]. MCA introduces two key coefficients to quantify this distribution:

- Flux Control Coefficients (FCCs): These quantify the effect of a small change in enzyme activity on the steady-state flux through a pathway. An FCC value close to 1 indicates that the enzyme exerts significant control over the flux, while values near 0 suggest minimal control [3] [24].

- Concentration Control Coefficients: These measure how enzyme activities affect metabolite concentrations within the pathway.

The summation theorem of MCA states that the sum of all FCCs in a pathway equals 1, confirming that control is distributed rather than concentrated [3]. This distribution depends not only on stoichiometric structure but also on kinetic parameters, including enzyme saturation levels, distance from thermodynamic equilibrium, and presence of feedback regulatory loops [24]. Understanding these determinants is crucial for predicting how metabolic adaptation occurs in response to genetic or environmental perturbations.

The power of MCA becomes particularly evident when compared to earlier approaches that relied on identifying single "rate-limiting steps" through qualitative methods such as inspecting pathway architecture, determining non-equilibrium reactions, or identifying enzymes with the lowest Vmax values [3]. These traditional approaches often led to unsuccessful metabolic engineering attempts because they failed to account for the distributed nature of metabolic control and the complex regulatory mechanisms that maintain metabolic homeostasis.

Principles of Inverse Metabolic Engineering (IME)

Inverse Metabolic Engineering represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering strategy. Rather than beginning with genetic modifications whose phenotypic consequences are uncertain, IME follows a systematic three-step process:

- Identification of a desired phenotype through analysis of natural variants, laboratory evolution, or random mutagenesis [1]

- Determination of the genetic basis responsible for conferring the superior phenotype using omics technologies and functional genomics [1] [13]

- Transfer of this genetic basis to the target strain through directed genetic manipulation [1]

This approach effectively reverses the traditional metabolic engineering workflow, moving from phenotype to genotype rather than from genotype to phenotype. The power of IME lies in its ability to leverage naturally evolved or experimentally selected superior phenotypes as blueprints for engineering, thus bypassing the limited success of traditional approaches that often encountered counter-balancing regulation and unknown coupled pathways [1].

IME has been successfully applied in diverse contexts, including elimination of growth factor requirements in mammalian cell culture and increasing the energetic efficiency of microaerobic bacterial respiration [1]. With the advent of advanced omics technologies, IME has gained powerful tools for identifying the genetic determinants of desirable phenotypes, making it increasingly effective for strain optimization [13].

Theoretical Integration: How MCA Informs IME and Vice Versa

The synergy between MCA and IME emerges from their complementary approaches to understanding and manipulating metabolic networks. MCA provides the theoretical framework for predicting which enzymatic modifications will most significantly impact flux, while IME offers the engineering strategy for implementing these modifications based on phenotypic evidence.

MCA helps prioritize genetic targets for IME by identifying enzymes with high flux control coefficients, thus increasing the efficiency of the IME process. Conversely, IME can generate phenotypic data that refine MCA models, particularly regarding complex regulatory interactions that may not be fully captured in theoretical frameworks. This iterative feedback between the two approaches creates a powerful cycle of hypothesis generation and experimental validation.

The integration is particularly valuable for understanding allosteric regulation and multi-enzyme synergy in key metabolic pathways. For example, research on the shikimate pathway—fundamental for aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in bacteria, plants, and fungi—reveals how enzymes like 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase (DAHPS), chorismate mutase, and tryptophan synthase function as integrated teams with sophisticated coordination mechanisms [25]. Understanding these allosteric networks through MCA provides crucial insights for IME strategies aimed at optimizing these pathways for industrial biocatalysis.

Figure 1: Theoretical Integration of MCA and IME - This diagram illustrates how MCA and IME function as complementary approaches, with MCA providing quantitative identification of key control points and IME offering a phenotype-driven implementation strategy, together creating an iterative cycle for metabolic optimization.

Quantitative Frameworks and Data Presentation

Metabolic Control Coefficients in Practice

The application of MCA requires precise quantification of flux control coefficients across metabolic pathways. Experimental determination of FCCs involves systematically modulating enzyme activities and measuring the resulting changes in metabolic fluxes. Several methodologies have been developed for this purpose, including enzyme titration using specific inhibitors, modulation of enzyme expression through genetic engineering, and monitoring flux changes in response to these perturbations [3].

Table 1: Flux Control Coefficient Ranges in Central Metabolic Pathways

| Pathway | Enzyme/Step | FCC Range | Organism | Method of Determination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | Glucose transporter | 0.2-0.4 | S. cerevisiae | Enzyme titration [3] |

| Glycolysis | Phosphofructokinase | 0.1-0.3 | S. cerevisiae | Enzyme titration [3] |

| Glycolysis | GAPDH | 0.3-0.6 | S. lactis | Iodoacetate inhibition [3] |

| Shikimate Pathway | DAHPS | 0.4-0.7 | E. coli | Enzyme overexpression [25] |

| TCA Cycle | Citrate synthase | 0.2-0.5 | Mammalian cells | 13C-MFA [26] |

The data in Table 1 illustrates how control is distributed across multiple steps in central metabolic pathways, with no single enzyme typically exerting complete control. This distribution varies significantly between organisms and growth conditions, highlighting the importance of context-specific MCA rather than general assumptions about rate-limiting steps.

Recent advances in MCA have extended its application to whole-cell analysis, considering metabolism in the evolutionary context of growth-rate maximization through optimization of protein concentrations [27]. This framework allows for predicting flux control coefficients from proteomics data or stoichiometric modeling, recognizing that genes compete for finite biosynthetic resources and all protein concentrations are interdependent [27].

Success Metrics in Inverse Metabolic Engineering

The effectiveness of IME strategies can be quantified through specific success metrics, particularly the fold-increase in product yield or titer achieved through identified genetic modifications. Case studies across different microbial platforms and target compounds demonstrate the consistent success of this approach.

Table 2: IME Success Metrics in Various Bioproduction Applications

| Target Compound | Host Organism | Identified Gene Target | Fold-Increase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxytyrosol | S. cerevisiae | Multiple modules (precursor, cofactor, competition) | 1.2x (118.53% increase) | [13] |

| Recombinant GFP | E. coli | ribB (3,4 dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase) | 7x specific yield | [18] |

| Recombinant GFP | E. coli | kdpD (histidine kinase) | 3.2x specific yield | [18] |

| Recombinant GFP | E. coli | mfd (mutation frequency decline protein) | 4x specific yield | [18] |

The data in Table 2 demonstrates how IME can identify non-intuitive genetic targets that significantly enhance product formation. For example, the identification of ribB as a target for downregulation to enhance recombinant protein production in E. coli was unexpected, as this gene encodes 3,4 dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase involved in riboflavin biosynthesis [18]. This highlights the power of IME to uncover non-obvious genetic determinants of desirable phenotypes.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Experimental Workflow for Integrated MCA-IME Approach

The synergy between MCA and IME is most effectively realized through a systematic experimental workflow that leverages the strengths of both approaches. This integrated methodology provides a structured pathway from initial phenotypic identification to strain optimization.

Figure 2: Integrated MCA-IME Experimental Workflow - This diagram outlines a systematic approach combining MCA and IME methodologies, beginning with phenotype identification, proceeding through modeling and genetic analysis, and culminating in targeted genetic modifications with an iterative feedback loop for continuous optimization.

Protocol 1: Determining Flux Control Coefficients

Objective: Quantify the flux control coefficients for enzymes in a target metabolic pathway using enzyme titration and metabolic flux analysis.

Materials:

- Specific enzyme inhibitors or CRISPRi system for targeted knockdown

- Isotopically labeled substrates (e.g., 13C-glucose)

- LC-MS or GC-MS system for flux analysis

- Stoichiometric model of the metabolic network

Procedure:

- Cultivate cells under controlled conditions in chemically defined medium

- Implement graded enzyme inhibition using specific inhibitors or titratable CRISPRi system

- Supplement with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose) during metabolic steady-state

- Measure extracellular fluxes (substrate uptake, product secretion rates)

- Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites

- Analyze mass isotopomer distributions using LC-MS or GC-MS

- Calculate metabolic fluxes using computational tools such as INCA or OpenFlux

- Determine FCCs from the relationship between enzyme activity changes and flux changes

Calculation: FCC = (ΔJ/J) / (ΔE/E) Where J is the pathway flux and E is the enzyme activity [3] [24]

Protocol 2: Implementing Inverse Metabolic Engineering

Objective: Identify genetic determinants of a high-production phenotype and transfer them to a production host.

Materials:

- Reference strain with desired production phenotype

- Production host strain for engineering

- Genomic library construction kit

- Metabolomics and transcriptomics platforms

- CRISPR-Cas9 system for genome editing

Procedure:

- Identify or create a reference strain with superior production characteristics through adaptive laboratory evolution or screening of natural isolates

- Conduct multi-omics analysis comparing reference and base strains:

- Perform metabolomic profiling to identify differential metabolite pools

- Conduct transcriptomic analysis to identify differentially expressed genes

- Integrate omics data with genome-scale metabolic models using constraint-based approaches

- Construct targeted genomic library or identify specific genetic modifications for testing

- Implement genetic modifications in production host using CRISPR-Cas9 or other genome editing tools

- Screen engineered strains for production phenotype and growth characteristics

- Validate performance in controlled bioreactor conditions [13] [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MCA and IME Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Analysis Tools | [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose | Isotopic labeling for MFA | Enables precise flux measurements through metabolic networks [26] |

| Gene Modulation Systems | CRISPRi, antisense RNA, sRNA | Targeted gene knockdown | Enables partial gene silencing for flux control studies [28] [18] |

| Omics Platforms | LC-MS, GC-MS, RNA-seq | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Identifies differential expression and metabolite pools [13] |

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox, INCA, TIDE | Metabolic modeling and analysis | Predicts flux distributions and control coefficients [29] [26] |

| Genome Engineering | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, ZFNs | Precise genetic modifications | Implements identified targets from IME screens [28] |

Case Studies in Therapeutic Applications

Drug Target Identification through MCA-IME Integration

The integration of MCA and IME has proven particularly valuable in drug discovery, especially for identifying potential targets in pathogenic organisms. A compelling application involves the shikimate pathway, which is essential in bacteria, plants, and fungi but absent in mammals, making it an attractive target for antimicrobial development [25].

Research on Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) demonstrates how MCA can identify key control points in this pathway. Studies revealed that DAHPS (3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase), which catalyzes the first committed step, exhibits significant flux control with FCC values ranging from 0.4-0.7 in various bacterial systems [25]. Furthermore, Mtb DAHPS demonstrates sophisticated inter-enzyme allostery through direct interaction with chorismate mutase (CM), creating a regulated metabolic complex that controls aromatic amino acid biosynthesis [25].

IME approaches complemented these findings by identifying natural variants with altered flux through the shikimate pathway and determining the genetic basis for these phenotypes. This combination allows researchers to not only identify potential drug targets but also predict resistance mechanisms that might emerge through metabolic adaptation, enabling the design of more robust therapeutic interventions.

Cancer Metabolism and Therapeutic Synergy

The MCA-IME framework has also advanced cancer metabolism research and therapeutic development. A recent study investigated the metabolic effects of kinase inhibitors and their synergistic combinations in gastric cancer cells using genome-scale metabolic models and transcriptomic profiling [29].

Researchers applied the Tasks Inferred from Differential Expression (TIDE) algorithm to infer pathway activity changes following treatment with TAK1, MEK, and PI3K inhibitors, both individually and in combination. The analysis revealed widespread down-regulation of biosynthetic pathways, particularly in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism [29]. Combinatorial treatments induced condition-specific metabolic alterations, including strong synergistic effects in the PI3Ki–MEKi condition affecting ornithine and polyamine biosynthesis.

This approach demonstrates how MCA principles can identify control points in cancer metabolism, while IME strategies help understand the metabolic basis of drug synergy. The integration of these frameworks provides insights into drug synergy mechanisms and highlights potential therapeutic vulnerabilities that might not be apparent through traditional pharmacological approaches alone.

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Technical Limitations and Solutions

Despite the powerful synergy between MCA and IME, researchers face several implementation challenges. A primary limitation is the resource intensity of determining precise flux control coefficients experimentally, particularly in eukaryotic systems with compartmentalized metabolism. Advances in computational modeling, including constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) and 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), are helping to address this challenge by enabling more accurate predictions of flux distributions [26].

Another significant challenge is the context-dependence of flux control coefficients, which can vary with growth conditions, genetic background, and metabolic network state. This necessitates condition-specific analyses rather than relying on universal FCC values. Multi-omics integration approaches help address this limitation by providing comprehensive molecular data that capture the dynamic nature of metabolic control [13].

Emerging single-cell technologies present both challenges and opportunities for the MCA-IME framework. While traditional MCA assumes population homogeneity, single-cell metabolomics and flux analysis reveal significant heterogeneity in metabolic states [26]. Developing approaches to account for this heterogeneity will enhance the predictive power of integrated MCA-IME strategies.

Emerging Technologies and Methodological Advances

Several emerging technologies promise to enhance the integration of MCA and IME in metabolic engineering and drug discovery:

Machine Learning Integration: Computational approaches are being developed to predict flux control coefficients from omics data, reducing the experimental burden of traditional MCA [26]. These models can learn from IME datasets to improve their predictive accuracy.

Single-Cell Metabolomics: Advances in mass spectrometry enable metabolic flux analysis at single-cell resolution, revealing heterogeneity in metabolic control within populations [26]. This resolution is particularly valuable for understanding cancer metabolism and microbial community dynamics.

Dynamic Flux Analysis: Traditional MCA focuses on steady-state conditions, but new approaches enable monitoring of flux dynamics in response to perturbations [26]. This temporal dimension provides insights into metabolic adaptation processes.

CRISPRi/a Screening Platforms: High-throughput CRISPR interference and activation screens enable systematic mapping of gene expression effects on metabolic fluxes [28]. These platforms generate valuable data for both MCA and IME applications.

The continued integration of MCA and IME represents a promising frontier in metabolic engineering, particularly for drug development professionals seeking to optimize microbial production of therapeutic compounds or identify novel drug targets in pathogenic and cancer metabolism. As both frameworks evolve with technological advances, their synergy will likely become increasingly central to rational metabolic design strategies.

Key Historical Developments and Foundational Research

Inverse metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from classical metabolic engineering approaches. While conventional forward metabolic engineering relies on a deep understanding of specific metabolic networks, gene functions, and regulatory elements to rationally design genetic modifications, inverse metabolic engineering adopts a fundamentally different strategy [13] [14]. This approach first identifies or constructs a desired phenotype, then determines the genetic or environmental factors conferring that phenotype, and finally transfers these factors to the target strain or organism [1] [18].

The field of metabolic engineering has evolved through three distinct waves of innovation [30]. The first wave (1990s) utilized rational pathway analysis and flux optimization to redirect metabolic fluxes. The second wave (2000s) incorporated systems biology and genome-scale metabolic models to bridge genotype-phenotype relationships. The current third wave leverages synthetic biology tools to design, construct, and optimize complete metabolic pathways for producing both natural and non-natural compounds [30]. Inverse metabolic engineering has emerged as a powerful strategy within this third wave, particularly for complex phenotypes where rational design is challenging.

Historical Development and Foundational Concepts

The term "inverse metabolic engineering" was formally codified in 2002 by Bailey and colleagues, who defined it as: "the elucidation of a metabolic engineering strategy by: first, identifying, constructing, or calculating a desired phenotype; second, determining the genetic or the particular environmental factors conferring that phenotype; and third, endowing that phenotype on another strain or organism by directed genetic or environmental manipulation" [1].

This approach was developed in response to the limitations of classical metabolic engineering, where intervention at presumed rate-determining steps often led to unexpected outcomes due to counter-balancing regulation and unknown coupled pathways [1]. The foundational principle of inverse metabolic engineering acknowledges that for many industrially valuable phenotypes, the critical genetic determinants are either unknown or would be impossible to predict through rational approaches alone [14].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Year | Development | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Formal codification of inverse metabolic engineering | Provided clear methodology for phenotype-driven strain engineering | [1] |

| 2012 | Application to recombinant protein production in E. coli | Demonstrated anti-sense RNA library screening for quiescent cell factories | [18] |

| 2013 | Comprehensive review of combinatorial approaches | Cataloged genetic diversity generation methods for inverse metabolic engineering | [14] |

| 2024 | Inverse engineering for hydroxytyrosol production in yeast | Showed integration of metabolomics with modular pathway engineering | [13] |

Fundamental Methodologies and Approaches

Core Workflow and Implementation Framework

The implementation of inverse metabolic engineering follows a systematic three-phase approach that distinguishes it from conventional methods [1] [14]:

Phenotype Identification: A desired phenotype is first identified through analysis of natural variants, laboratory evolution, or computational modeling of ideal properties.

Determinant Elucidation: The genetic, metabolic, or environmental basis for the superior phenotype is determined using various analytical methods.

Phenotype Transfer: The identified determinants are transferred to the target production host through appropriate genetic engineering.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comparative strategies between classical and inverse metabolic engineering approaches:

Genetic Diversity Generation Methods

A critical component of inverse metabolic engineering is the generation of genetic diversity, which enables the identification of non-obvious genetic determinants of superior phenotypes. Multiple methods have been developed for this purpose:

Table 2: Genetic Diversity Generation Methods in Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Method | Mechanism | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Mutagenesis | Natural accumulation of mutations during serial passaging | Ethanol/isobutanol tolerance in E. coli; xylose utilization in yeast [14] | Models natural evolution; minimal technical requirements | Time-consuming; mutations randomly distributed |

| Chemical/UV Mutagenesis | DNA damage using mutagens (EMS, NTG) or UV irradiation | Isobutanol production, membrane protein expression in E. coli [14] | High mutation frequency; genome-wide coverage | Potential for undesirable mutations |

| Transposon Mutagenesis | Random insertion of mobile genetic elements | Identification of inhibitory genes in lycopene, riboflavin production [14] | Direct genotype-phenotype links; comprehensive knockout libraries | Limited to non-essential genes; insertion bias |

| Genomic Library Overexpression | Expression of random genomic fragments in vectors | Alcohol tolerance, galactose fermentation in yeast [14] | Identifies gain-of-function improvements; covers essential genes | Screening complexity; false positives |

| Antisense RNA Libraries | Gene silencing via antisense RNA expression | Recombinant protein production in E. coli [18] | Tunable gene expression; targets essential genes; partial silencing | Variable silencing efficiency; design complexity |

Analytical Framework for Determinant Identification

Once genetic diversity is generated and desired phenotypes are identified, the next critical phase involves determining the specific genetic factors responsible. Modern inverse metabolic engineering heavily relies on multi-omics integration for this purpose [13]:

- Metabolomics: Provides quantitative analysis of metabolic differentials, identifying rate-limiting steps and pathway bottlenecks through comparison with reference strains [13].

- Genome Sequencing: Reveals mutations, insertions, deletions, and rearrangements contributing to improved phenotypes.

- Flux Correlation Analysis: Examines relationships between reaction fluxes over all feasible steady states, using reaction correlation coefficients (φij) to identify key regulatory nodes [31].

- Transcriptomics/Proteomics: Identifies expression changes underlying phenotypic improvements.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated omics framework for identifying genetic determinants in inverse metabolic engineering:

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: Inverse Metabolic Engineering for Hydroxytyrosol Production inS. cerevisiae

A recent landmark application of inverse metabolic engineering demonstrates the efficient production of hydroxytyrosol, a valuable plant-derived phenolic compound, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [13]. The detailed methodology exemplifies modern inverse metabolic engineering approaches:

Background and Objective: Hydroxytyrosol possesses significant antioxidant, antisteatotic, and neuroprotective properties, but its natural extraction is complex and chemical synthesis environmentally unfriendly [13]. Previous metabolic engineering achieved 308.65 mg/L, but hidden rate-limiting steps remained.

Experimental Workflow:

Metabolomic Profiling: Comprehensive metabolomics compared the engineered hydroxytyrosol-producing strain (YLYJ4-Pac) with the wild-type BY4741 reference strain under identical conditions [13].

Differential Metabolite Analysis: Identified significant alterations in central carbon metabolism, cofactor balances, and competing pathway fluxes.

Modular Pathway Engineering Implementation:

- Module I: Reinforced precursor (tyrosol) pool through promoter engineering and key pathway gene overexpression (aro4K229L, aro7G141S for tyrosine feedback inhibition relief; Pcaasopt, Bbxfpkopt for flux rewiring).

- Module II: Optimized cofactor supply (NADH and FADH2) through regeneration and reconstruction of cofactor cycles.

- Module III: Weakened competitive pathways by deleting competing genes (pdc, gpd) [13].

Validation: Combined regulation of three modules increased hydroxytyrosol titer by 118.53% over the initial background strain, reaching 639.84 mg/L in shake-flask fermentation [13].

Table 3: Quantitative Results from Hydroxytyrosol Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Engineering Module | Specific Genetic Modifications | Hydroxytyrosol Titer (mg/L) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Strain (YLYJ4-Pac) | Previous metabolic engineering | 308.65 | Reference |

| Module I | Precursor enhancement: aro4K229L, aro7G141S, promoter engineering | 427.82 | 1.39x |

| Module II | Cofactor optimization: NADH/FADH2 regeneration | 385.46 | 1.25x |

| Module III | Competitive pathway reduction: Δpdc, Δgpd | 352.17 | 1.14x |

| Combined Modules | Integrated all modifications | 639.84 | 2.07x |

Protocol: Inverse Metabolic Engineering for Recombinant Protein Production

Another foundational protocol demonstrates inverse metabolic engineering for designing improved E. coli hosts for recombinant protein production [18]:

Objective: Generate non-growing but metabolically active quiescent cells to divert metabolic fluxes toward recombinant protein production rather than growth.

Experimental Design:

Antisense Library Construction:

- Partial digestion of E. coli genomic DNA to generate 200-800 bp fragments.

- Ligation into pRSET A vector (strong T7 promoter) and pBAD33 (weaker arabinose promoter).

- Transformation into E. coli BL21 pLysS strain, generating ~8,000 transformants.

Phenotype Screening:

- Primary screening for slow-growth/no-growth phenotype upon IPTG induction.

- Secondary screening for metabolic activity via glucose consumption rates.

- Identification of 17 clones with growth retardation but maintained metabolic activity.

Protein Production Screening:

- Co-transformation with pBAD33-GFP reporter plasmid.

- Assessment of GFP fluorescence under induced vs. control conditions.

- Identification of clones with significantly increased specific product yields.

Key Findings:

- Down-regulation of ribB (3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase) increased specific product yield 7-fold.

- Down-regulation of mfd (mutation frequency decline protein) increased specific yield 4-fold.

- Down-regulation of kdpD (histidine kinase) increased specific yield 3.2-fold [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Inverse Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector Systems | pRSET A (T7 promoter), pBAD33 (araBAD promoter) | Antisense library construction; tunable expression | [18] |

| Host Strains | E. coli BL21 pLysS, S. cerevisiae BY4741 | Model platforms for library screening and validation | [18] [13] |

| Mutagenic Agents | N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG), ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) | Chemical mutagenesis for genetic diversity generation | [14] |

| Transposon Systems | Commercial transposon kits; Keio collection (E. coli knockout library) | Genome-wide gene disruption studies | [14] |

| Analytical Platforms | GC-MS, LC-MS for metabolomics; NGS for genome sequencing | Determinant identification and validation | [13] [31] |

| Reporter Systems | GFP, antibiotic resistance markers | Phenotype screening and selection | [18] |

| Pathway Assembly Tools | Golden Gate assembly, CRISPR-Cas systems | Modular pathway engineering for phenotype transfer | [13] [30] |

Integration with Metabolic Control Analysis

Inverse metabolic engineering interfaces strongly with metabolic control analysis (MCA), particularly through advanced computational approaches. The Probabilistic Minimum Dominating Set (PMDS) model represents one such integration, identifying minimum sets of driver nodes that control entire metabolic networks in contexts of probabilistic interaction failures [31].

Key Research Findings:

- Cancer metabolic states generally show higher flux correlations than healthy states in breast, kidney, and urothelial tissues.

- Cancer states require fewer controller nodes than healthy states, suggesting more streamlined flux distributions.

- Central metabolic pathways (glycolysis, pyruvate metabolism, citrate cycle) are enriched in controller nodes across both healthy and cancer networks [31].

This integration enables more sophisticated identification of control points for inverse metabolic engineering strategies, particularly for complex phenotypes involving multiple interconnected pathways.

Inverse metabolic engineering has evolved from a conceptual framework to a robust methodology that complements conventional metabolic engineering approaches. The integration of multi-omics technologies, high-throughput screening, and computational modeling has significantly enhanced its predictive power and application scope [13] [30] [31].

Future developments will likely focus on:

- Machine learning integration for more efficient determinant identification from complex datasets.

- Expanded application to non-model organisms through adapted genetic tools.

- Dynamic regulation systems for real-time metabolic flux optimization.

- Integration with genome-scale metabolic models for more comprehensive pathway contextualization.

The continued refinement of inverse metabolic engineering approaches promises to accelerate the development of microbial cell factories for sustainable production of high-value chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and materials, addressing critical challenges in resource efficiency, environmental protection, and climate change mitigation [13] [30].

Integrated Workflows: From Genetic Screening to Pathway Optimization

Inverse Metabolic Engineering (IME) serves as a powerful framework for integrating evolutionary engineering approaches with direct metabolic engineering strategies. IME is defined by a three-step process: first, the identification or calculation of a desired phenotype; second, the determination of the genetic or environmental factors conferring that phenotype; and third, the endowment of that phenotype on another strain or organism through directed genetic or environmental manipulation [32]. This approach has become increasingly valuable for developing microbial cell factories that produce useful chemicals, fuels, and materials from renewable resources, representing a key enabling technology for sustainable biomanufacturing [30].