Integrating Omics Data into Metabolic Network Models: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Biomedicine

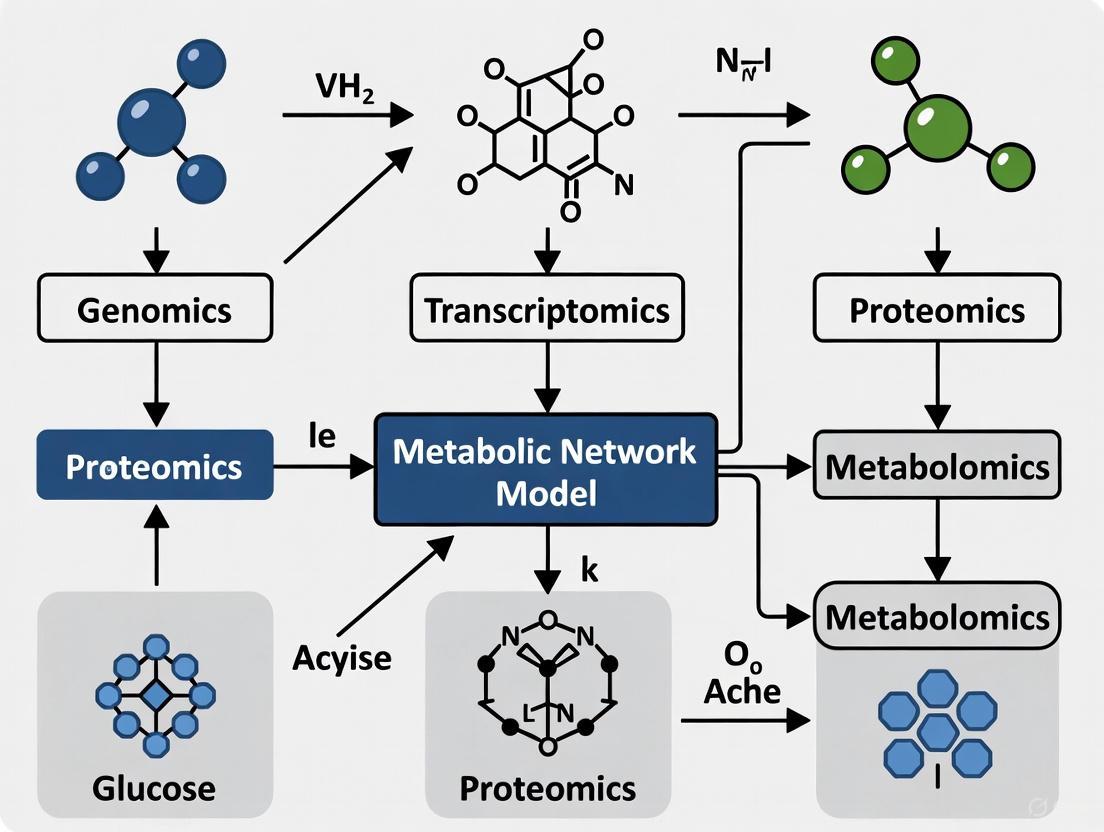

The integration of multi-omics data into genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) is revolutionizing systems biology and precision medicine.

Integrating Omics Data into Metabolic Network Models: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Biomedicine

Abstract

The integration of multi-omics data into genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) is revolutionizing systems biology and precision medicine. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling and the evolution of human metabolic reconstructions like Recon and HMR. It details cutting-edge methodological approaches for data integration, from transcriptomics to metabolomics, and addresses critical challenges in data processing, normalization, and computational implementation. Through a comparative analysis of tools and validation techniques, we illustrate how integrated models enhance the prediction of metabolic fluxes, identify drug targets, and pave the way for personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype.

The Foundation of Metabolic Modeling: From Networks to Multi-Omics Integration

Understanding Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) and Constraint-Based Frameworks

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, transforming cellular growth and metabolism processes into mathematical formulations based on stoichiometric matrices [1]. Since the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae was reconstructed in 1999, the number and complexity of these models have steadily increased, with thousands now available for diverse organisms including bacteria, yeast, and humans [1] [2]. GEMs have evolved from basic metabolic networks to sophisticated multiscale models that integrate various cellular processes and constraints, serving as indispensable tools in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research [1] [3].

The fundamental principle underlying GEMs is the constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) approach, which employs mass-balance, thermodynamic, and capacity constraints to define the set of possible metabolic phenotypes [1] [2]. By leveraging genomic and biochemical information, GEMs enable researchers to predict cellular behavior under different genetic and environmental conditions, providing a powerful framework for linking genotype to phenotype [1]. The development of computational toolboxes such as COBRA, COBRApy, and RAVEN has further accelerated the adoption of GEMs across biological research domains [2].

Core Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling

Mathematical Foundations

Constraint-based modeling relies on the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sₙₘ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite n in reaction m. The fundamental equation governing metabolic fluxes under steady-state assumptions is:

S · v = 0

where v is the vector of metabolic reaction fluxes [1]. This mass balance constraint ensures that metabolite production and consumption rates are balanced, reflecting homeostasis in biological systems. The solution space is further constrained by enzyme capacity and thermodynamic constraints:

α ≤ v ≤ β

where α and β represent lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, respectively [1]. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) identifies optimal flux distributions by maximizing an objective function (typically biomass production) within these constraints:

maximize cᵀv subject to S·v = 0, α ≤ v ≤ β [1]

Types of Constraints in Metabolic Models

Table: Key Constraint Types in Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Significance | Implementation Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric | S·v = 0 | Mass conservation of metabolites | FBA, FVA |

| Thermodynamic | ΔG = ΔG°' + RT·ln(Q) | Reaction directionality based on energy | TMFA, NET analysis |

| Enzymatic | v ≤ kₐₜₜ·[E]·MWE | Catalytic limits of enzymes | GECKO, MOMENT |

| Transcriptional | vᵢ = 0 if geneᵢ not expressed | Gene expression regulation | iMAT, GIM3E, INIT |

| Environmental | αₑₓ ≤ vₑₓ ≤ βₑₓ | Nutrient availability | dFBA, COMETS |

Thermodynamic constraints incorporate Gibbs free energy calculations to determine reaction directionality, eliminating thermodynamically infeasible pathways [1] [4]. Enzymatic constraints account for the limited catalytic capacity of enzymes and cellular proteome allocation [5]. The integration of these constraints significantly improves the predictive accuracy of GEMs by incorporating more biological realism into the models.

Multiscale Frameworks and Omics Integration

Multi-Omics Data Integration

Modern GEMs have evolved beyond metabolic networks to incorporate multiscale data from transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [1] [6]. This integration enables context-specific model extraction, where generic GEMs are tailored to particular biological conditions, cell types, or disease states [7] [2]. Algorithms such as iMAT, MADE, and GIM3E leverage transcriptomic data to create condition-specific models by constraining reactions based on gene expression levels [1]. More recently, methods like TIDE (Tasks Inferred from Differential Expression) infer pathway activity changes directly from gene expression data without requiring full GEM reconstruction [7].

The MINIE framework represents a cutting-edge approach for multi-omic network inference from time-series data, integrating single-cell transcriptomics with bulk metabolomics through a Bayesian regression framework [6]. This method explicitly models the timescale separation between molecular layers using differential-algebraic equations (DAEs), where slow transcriptomic dynamics are captured by differential equations and fast metabolic dynamics are encoded as algebraic constraints [6]. Such approaches demonstrate how multi-omic integration provides a more holistic understanding of biological systems.

Enzyme-Constrained Frameworks

The GECKO (Enhancement of GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox represents a major advancement in enzyme-constrained modeling [5]. GECKO extends classical FBA by incorporating detailed enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [5]. The toolbox automates the retrieval of kinetic parameters from the BRENDA database and enables direct integration of proteomics data as constraints for individual enzyme usage [5].

Table: GECKO 2.0 Implementation Workflow

| Step | Function | Input Requirements | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Preparation | Convert standard GEM to enzyme-aware structure | Stoichiometric model, proteomic data | Expanded metabolite/reaction set |

| kcat Assignment | Retrieve and apply enzyme kinetic parameters | BRENDA database, organism-specific preferences | kcat values for enzyme reactions |

| Proteome Integration | Constrain model with measured enzyme abundances | Mass spectrometry proteomics data | Protein allocation profiles |

| Model Simulation | Solve proteome-constrained optimization problem | Growth medium composition | Predictive flux distributions |

The GECKO framework has been successfully applied to models of S. cerevisiae, E. coli, and even human cells, improving predictions of metabolic behaviors such as the Crabtree effect in yeast [5]. Enzyme-constrained models have demonstrated particular value in predicting cellular responses to genetic and environmental perturbations, as they explicitly account for the metabolic costs of protein synthesis [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Construction of Context-Specific GEMs Using Multi-Omics Data

Objective: Reconstruct a cell-type specific metabolic model from a generic GEM using transcriptomic and proteomic data.

Materials:

- High-quality generic GEM (e.g., Human1, Yeast8)

- RNA-seq transcriptomic data for target condition

- Mass spectrometry-based proteomic data (optional)

- Computational environment with COBRA Toolbox v3.0 or COBRApy

- Model extraction algorithm (iMAT, FASTCORE, or INIT)

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize transcriptomic data using TPM or FPKM values

- Map gene identifiers to model gene rules using biomart or custom mapping files

- Convert expression values to reaction confidence scores using percentile ranking

Model Extraction:

- Define core reactions based on expression thresholds (e.g., top 60% expressed genes)

- Implement the chosen extraction algorithm to create a context-specific model:

- For iMAT: maximize the number of highly expressed reactions carrying flux while minimizing flux through lowly expressed reactions

- For FASTCORE: identify the minimal set of reactions consistent with the expression data

Model Validation:

- Test essential gene predictions against siRNA or CRISPR screening data

- Compare predicted growth rates with experimentally measured values

- Validate substrate utilization preferences with experimental data

Advanced Constraint Integration:

- Incorporate enzyme constraints using the GECKO toolbox if proteomic data is available

- Add thermodynamic constraints using the TMFA framework

- Integrate metabolite levels as additional constraints if metabolomic data exists

This protocol typically requires 24-48 hours of computational time depending on model size and can be implemented in MATLAB or Python environments [1] [2].

Protocol: Metabolic Task Analysis Using TIDE Framework

Objective: Identify metabolic pathway activity changes from differential gene expression data.

Materials:

- RNA-seq data from control and treatment conditions

- Predefined metabolic tasks (e.g., from MetaCyc or KEGG)

- MTEApy Python package (implements TIDE algorithm)

- Reference GEM for the studied organism

Procedure:

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Identify differentially expressed genes using DESeq2 or similar tools

- Calculate log2 fold changes and adjusted p-values

Task Feasibility Assessment:

- For each metabolic task, determine the set of associated genes

- Assess the impact of expression changes on task feasibility using TIDE scoring

- Compute significance values through permutation testing

Synergy Analysis (for combinatorial treatments):

- Compare observed task activities in combination treatments to expected additive effects

- Calculate synergy scores for significantly altered metabolic processes

Visualization and Interpretation:

- Create heatmaps of significantly altered metabolic tasks

- Map results onto pathway diagrams using KEGG or Reactome

This approach has been successfully applied to study drug-induced metabolic changes in cancer cells, revealing synergistic effects of kinase inhibitor combinations on specific biosynthetic pathways [7].

Reproducibility and Quality Control

FROG Analysis Framework

Ensuring reproducibility in GEM development remains a significant challenge, with studies indicating that approximately 40% of models cannot be reproduced based on originally published information [3]. The FROG (Flux variability, Reaction deletion, Objective function, Gene deletion) analysis framework was developed to address this issue by standardizing reproducibility assessments [3].

FROG analysis generates comprehensive reports that serve as reference datasets, enabling independent verification of model simulations. The framework includes four core components:

- Flux Variability Analysis: Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value

- Reaction Deletion Analysis: Predicts growth phenotypes after single reaction knockouts

- Objective Function Analysis: Tests model sensitivity to different biological objectives

- Gene Deletion Analysis: Predicts growth phenotypes after single gene knockouts

Integration of FROG analysis into the BioModels repository has demonstrated that approximately 40% of submitted GEMs reproduce without intervention, 28% require minor technical adjustments, and 32% need author input to resolve reproducibility issues [3]. This highlights both the importance and current limitations in GEM reproducibility.

Tools for Model Quality Assessment

MEMOTE provides an automated testing suite for GEM quality assessment, evaluating factors such as stoichiometric consistency, metabolite charge balance, and annotation completeness [3]. The tool generates a quality score that allows researchers to quickly identify potential model deficiencies and compare different model versions. Combined with FROG analysis, these tools are establishing much-needed standards for model quality and reproducibility in the field.

Table: Essential Tools for GEM Construction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Requirements | Output | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | Enzyme constraint integration | GEM, kcat values, proteomics | ecModel | MATLAB/Python |

| MetaDAG | Metabolic network reconstruction | KEGG organisms, reactions, enzymes | Reaction graphs, m-DAG | Web-based |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling | Stoichiometric model, constraints | Flux predictions, gene essentiality | MATLAB |

| COBRApy | Python implementation of COBRA | Same as COBRA Toolbox | Same as COBRA Toolbox | Python |

| MEMOTE | Model quality assessment | GEM in SBML format | Quality report | Web-based/CLI |

| FROG | Reproducibility analysis | GEM, simulation conditions | Reproducibility report | Multiple |

MetaDAG is a particularly valuable web-based tool that constructs metabolic networks from KEGG database information, generating both reaction graphs and metabolic directed acyclic graphs (m-DAGs) [8] [9]. The tool can process various inputs including specific organisms, sets of organisms, reactions, enzymes, or KEGG Orthology identifiers, making it applicable to both single organisms and complex microbial communities [8].

Applications in Biomedical Research

Drug Discovery and Combination Therapy

GEMs have demonstrated significant utility in drug discovery, particularly in identifying metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells and understanding mechanisms of drug synergy [7]. For example, constraint-based modeling of kinase inhibitor combinations in gastric cancer cells revealed widespread down-regulation of biosynthetic pathways, with combinatorial treatments inducing condition-specific metabolic alterations [7]. The PI3Ki-MEKi combination showed strong synergistic effects on ornithine and polyamine biosynthesis, highlighting potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [7].

Disease Subtyping and Personalized Medicine

The integration of GEMs with clinical omics data enables metabolic subtyping of diseases and development of personalized therapeutic approaches. In endometrial cancer, GEM-based analysis identified two metabolic subtypes with distinct patient survival outcomes, correlated with histological features and genomic alterations [2]. Such approaches facilitate the stratification of patients based on their metabolic profiles, potentially guiding targeted interventions.

Similar methodologies have been applied to study metabolic changes in platelets during cold storage [2] and to investigate the metabolic signatures of COVID-19 [2], demonstrating the versatility of GEMs across diverse biomedical applications.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for GEM Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Databases | BioModels, BIGG Models | Repository of curated GEMs | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels/, http://bigg.ucsd.edu |

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Enzyme kinetic parameters | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/, https://sabio.h-its.org/ |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, Reactome | Metabolic pathway information | https://www.genome.jp/kegg/, https://metacyc.org/ |

| Software Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy, RAVEN | GEM simulation and analysis | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/, https://github.com/opencobra/cobrapy |

| Quality Control Tools | MEMOTE, FROG | Model testing and reproducibility | https://memote.io/, https://github.com/opencobra/COBRA.paper |

| Specialized Tools | GECKO, MetaDAG | Enzyme constraints, network analysis | https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/GECKO, https://bioinfo.uib.es/metadag/ |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The field of genome-scale metabolic modeling continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges. The integration of machine learning approaches with constraint-based models shows particular promise for enhancing predictive capabilities and handling multi-omics data complexity [1] [2]. Deep learning applications include EC number prediction (DeepEC) and multi-omics algorithms for phenotype prediction [1].

Whole-cell modeling represents another frontier, aiming to unify metabolic networks with other cellular processes within comprehensive simulation frameworks [1]. Tools such as WholeCellKB, CellML, and CellDesigner provide platforms for developing these integrated models [1].

Key challenges that remain include improving the reproducibility of GEM simulations, standardizing context-specific model extraction methods, and expanding the coverage of kinetic parameters for non-model organisms [5] [3]. The development of automated pipelines for model updating, such as the ecModels container in GECKO 2.0, addresses the need for version-controlled model resources that keep pace with expanding biological knowledge [5].

As GEM methodologies continue to mature, their application in biomedical research and therapeutic development is expected to grow substantially, ultimately contributing to more effective personalized medicine approaches and biological discovery.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) serve as foundational platforms for interpreting multi-omics data and predicting metabolic phenotypes in health and disease. The evolution from RECON 1 to Human1 represents a paradigm shift in the comprehensiveness, quality, and applicability of human metabolic reconstructions. This technical review documents the quantitative and qualitative advances across model generations, detailing the experimental and computational protocols that enabled this progression. Framed within the broader context of omics data integration, we highlight how these community-driven resources have transformed systems biology approaches in basic research and therapeutic development, particularly through the generation of tissue-specific models for studying cancer, metabolic disorders, and inflammatory diseases.

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions are structured knowledge bases that represent the biochemical transformations occurring within a cell or organism. Formulated as stoichiometric matrices, these reconstructions enable constraint-based modeling approaches, notably Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), to predict metabolic flux distributions, nutrient utilization, and growth capabilities under defined conditions [10] [11]. For human systems, GEMs provide an mechanistic framework for mapping genotype to phenotype, contextualizing high-throughput omics data, and identifying metabolic vulnerabilities in pathological states [11].

The reconstruction process systematically assembles metabolic knowledge from genomic, biochemical, and physiological data into a computable format [11]. Early human metabolic models were limited in scope and suffered from compartmentalization inaccuracies, identifier inconsistencies, and knowledge gaps that hampered their predictive accuracy and integrative potential. The progression from RECON 1 to the unified Human1 model reflects two key developments: first, the formal integration of multiple model lineages into a consensus resource, and second, the establishment of version-controlled, community-driven development frameworks that ensure ongoing curation and refinement [12].

The Founding Generation: RECON 1 and Its Contributions

RECON 1, published in 2007, established the first global human metabolic reconstruction, formalizing over 50 years of biochemical research into a structured knowledge base [10] [11]. This foundational model accounted for 1,496 open reading frames, 2,004 proteins, 2,766 metabolites, and 3,311 metabolic reactions, compartmentalized across the cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondria, lysosome, peroxisome, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum [10].

RECON 1 Reconstruction Methodology and Validation

The reconstruction employed a rigorous "bottom-up" protocol that began with an initial set of 1,865 human metabolic genes identified from genome sequence Build 35 [11]. Associated enzymes and reactions were drafted from databases including KEGG and ExPASy, followed by extensive manual curation using over 1,500 primary literature sources. Model functionality was validated against 288 known human metabolic functions, ensuring basic network capability [11]. A key structural feature was the incorporation of gene-protein-reaction (GPR) annotations—Boolean rules defining the relationships between genes, transcripts, proteins, and catalytic functions—thus establishing a mechanistic genotype-phenotype link [11].

Knowledge Gaps and Computational Gap-Filling

Flux variability analysis of RECON 1 identified 175 blocked reactions (5% of total reactions) distributed across 80 reaction cascades caused by 109 dead-end metabolites [10]. These gaps, predominantly found in cytosolic amino acid metabolism (particularly tryptophan degradation pathways), represented regions of incomplete metabolic knowledge where metabolites were either only produced or consumed within the network [10]. Researchers employed the SMILEY algorithm to computationally propose gap-filling solutions, suggesting candidate reactions from universal databases like KEGG to restore flux through blocked reactions [10]. This approach generated biologically testable hypotheses, such as novel metabolic fates for iduronic acid following glycan degradation and for N-acetylglutamate in amino acid metabolism [10].

The Evolution to Human1: A Unified Consensus Model

Human1 represents the first version of a unified human GEM lineage (Human-GEM), created by integrating and extensively curating the previously parallel Recon and HMR model series [12] [13]. This consensus model was developed to address critical challenges in existing GEMs, including non-standard identifiers, component duplication, error propagation, and disconnected development efforts [12].

Human1 Integration and Curation Protocol

The generation of Human1 involved systematic integration of components from HMR2, iHsa, and Recon3D, followed by extensive curation [12]. The multi-stage curation process included:

- Removal of duplicates: 8,185 duplicated reactions and 3,215 duplicated metabolites were identified and removed.

- Formula revision: 2,016 metabolite formulas were corrected based on biochemical evidence.

- Reaction re-balancing: 3,226 reaction equations were mass and charge-balanced.

- Connectivity enhancement: Gene-reaction associations from HMR2, Recon3D, and iHsa were combined with enzyme complex information from CORUM database.

- Identifier standardization: 88.1% of reactions and 92.4% of metabolites were mapped to standard identifiers (KEGG, MetaCyc, ChEBI) using MetaNetX, facilitating interoperability with external databases and omics datasets [12].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Human Metabolic Reconstructions

| Feature | RECON 1 | Human1 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | 1,496 | 3,625 | +142% |

| Reactions | 3,311 | 13,417 | +305% |

| Metabolites | 2,766 | 10,138 | +266% |

| Unique Metabolites | - | 4,164 | - |

| Compartments | 7 | 8 | +1 |

| Mass Balanced Reactions | Not reported | 99.4% | - |

| Charge Balanced Reactions | Not reported | 98.2% | - |

Quality Assessment Using Memote

Human1 underwent rigorous quality assessment using Memote, a standardized test suite for GEM evaluation [12]. The model demonstrated 100% stoichiometric consistency, 99.4% mass-balanced reactions, and 98.2% charge-balanced reactions—markedly improved over Recon3D, which showed only 19.8% stoichiometric consistency in its base form [12]. The average annotation score for model components reached 66%, substantially higher than previous models (HMR2: 46%, Recon3D: 25%), though indicating an area for continued community effort [12].

Methodological Advances: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Flux Variability Analysis for Gap Identification

Flux variability analysis (FVA) identifies blocked reactions and dead-end metabolites in metabolic networks by determining the range of possible fluxes through each reaction under steady-state conditions [10]. The protocol involves:

- Model preconditioning: Set exchange reactions to allow minimal uptake/secretion of metabolites required for network functionality.

- Optimization: Maximize and minimize flux through each reaction subject to:

- Steady-state constraint: ( S \cdot v = 0 )

- Thermodynamic constraints: ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i )

- Optional biomass optimization constraint

- Gap classification: Reactions with both minimum and maximum flux bounds equal to zero are classified as blocked [10].

- Metabolite tracing: Identify dead-end metabolites that serve as either only produced (root no-consumption) or only consumed (root no-production) within the network [10].

Figure 1: Flux Variability Analysis Workflow for Identifying Network Gaps

SMILEY Algorithm for Automated Gap-Filling

The SMILEY algorithm computationally proposes reactions to fill network gaps by integrating metabolic reactions from universal databases [10]. The methodology:

- Input preparation: Compile stoichiometric matrices for the target model (S), universal biochemical reactions (U), and transport reactions (X).

- Problem formulation: For each dead-end metabolite, identify minimal sets of reactions from U and X that enable flux through associated blocked reactions.

- Solution generation: Return up to twenty candidate solutions per gap, ranked by minimal number of added reactions.

- Solution categorization:

- Category I: Solutions requiring reversal of blocked reaction directionality

- Category II: Solutions requiring addition of novel metabolic reactions

- Category III: Solutions requiring transport reactions for dead-end metabolites [10]

Context-Specific Model Reconstruction

The generation of tissue- and cell-type-specific models from the generic Human1 framework enables precision modeling of metabolic specialization [12] [11]. The standard protocol involves:

- Data acquisition: Collect transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomic data for the target cell/tissue type.

- Reaction activity scoring: Integrate omics data with gene-protein-reaction associations to score reaction presence/activity.

- Network pruning: Remove reactions with insufficient evidence of activity in the target context.

- Functionality validation: Ensure the pruned network retains essential metabolic functions through simulation tests.

- Biomass formulation: Adjust biomass composition to reflect tissue-specific requirements when necessary [12] [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Metabolic Modeling

| Resource | Type | Function/Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-GEM Repository | Version-controlled model | Primary source for Human1 model files & documentation | GitHub: SysBioChalmers/Human-GEM [13] |

| Metabolic Atlas | Web portal | Interactive visualization, omics data integration, pathway exploration | https://www.metabolicatlas.org/ [12] |

| Memote | Quality assessment tool | Standardized test suite for GEM validation and quality reporting | Open source [12] |

| MetaNetX | Reference database | Identifier mapping, reaction/metabolite standardization | https://www.metanetx.org/ [12] |

| SMILEY | Algorithm | Automated gap-filling of network reconstructions | Available in COBRA Toolbox [10] |

| CORUM Database | Protein complex data | Provides enzyme complex information for GPR associations | https://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/corum/ [12] |

Applications in Omics Data Integration and Disease Modeling

Multi-Omic Integration for Precision Pathology

Human1 serves as a scaffold for integrating multi-omics data to investigate metabolic dysregulation in disease contexts. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), researchers reconstructed context-specific metabolic models from transcriptomic data of colon biopsies and blood samples, identifying 3,115 and 6,114 reactions significantly associated with disease activity, respectively [14]. Concurrent microbiome metabolic modeling revealed complementary disruptions in NAD, amino acid, and one-carbon metabolism, suggesting novel host-microbiome co-metabolic dysfunction in IBD pathogenesis [14].

Advanced multi-omic network inference approaches like MINIE (Multi-omIc Network Inference from timE-series data) leverage the timescale separation between molecular layers, using differential-algebraic equations to model slow transcriptomic and fast metabolomic dynamics [6]. This enables causal inference of regulatory interactions across omic layers, moving beyond correlation-based analyses [6].

Figure 2: Multi-Omic Data Integration Workflow Using Human1

Flux-Sum Coupling Analysis for Metabolite Concentration Proxies

Flux-sum coupling analysis (FSCA) extends constraint-based modeling to study interdependencies between metabolite concentrations by defining coupling relationships based on flux-sums [15]. The flux-sum of a metabolite ( \Phi_i ) is defined as:

[ \Phii = \frac{1}{2} \sum |S{ij}| \cdot |v_j| ]

where ( S{ij} ) represents stoichiometric coefficients and ( vj ) represents reaction fluxes [15]. FSCA categorizes metabolite pairs into three coupling types:

- Directionally coupled: Non-zero flux-sum of metabolite A implies non-zero flux-sum of metabolite B, but not vice versa

- Partially coupled: Non-zero flux-sum of A implies non-zero flux-sum of B and vice versa

- Fully coupled: Non-zero flux-sum of A implies a fixed, non-zero flux-sum of B and vice versa [15]

Applied to models of E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and A. thaliana, FSCA revealed directional coupling as the most prevalent relationship (ranging from 3.97% to 80.66% of metabolite pairs across models), demonstrating the method's utility as a proxy for metabolite concentrations when direct measurements are unavailable [15].

The evolution from RECON 1 to Human1 represents more than a quantitative expansion of metabolic knowledge—it embodies a fundamental shift in how biological knowledge is structured, shared, and applied. The establishment of version-controlled, community-driven development frameworks ensures that human metabolic models will continue to evolve in accuracy and scope, directly addressing the reproducibility and transparency concerns prevalent in computational research [12].

Future developments will likely focus on enhanced multi-omic integration, single-cell metabolic modeling, and dynamic flux prediction capabilities. Tools like GEMsembler, which enables consensus model assembly from multiple reconstruction tools, demonstrate the potential for hybrid approaches that harness unique strengths of different algorithms [16]. As these models become increasingly refined and accessible, they will play an indispensable role in drug development, personalized medicine, and our fundamental understanding of human physiology and pathology.

The rapid advancement of high-throughput technologies has enabled comprehensive characterization of cellular models across multiple molecular layers, generating vast multi-omics datasets that offer unprecedented opportunities for precision medicine [17]. However, integrating these diverse datasets remains fundamentally challenging due to their high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and technical artifacts [17]. This technical review examines the central challenges in multi-omics data integration and demonstrates how overcoming these limitations through advanced computational methods enhances predictive power in genome-scale metabolic modeling, ultimately enabling more accurate predictions of genotype-phenotype relationships in complex biological systems [18].

Multi-omics studies have become commonplace in precision medicine research, providing holistic perspectives of biological systems and uncovering disease mechanisms across molecular scales [17]. Several major consortia, including TCGA/ICGC and ProCan, have generated invaluable multi-omics resources, particularly for cancer studies [17]. Despite this potential, predictive modeling faces three fundamental challenges: scarcity of labeled data, generalization across domains, and disentangling causation from correlation [18].

The integration of omics data—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—within mathematical frameworks like genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) has revolutionized our understanding of biological systems by providing a structured approach to bridge genotypes and phenotypes [19]. This integration is essential for predicting metabolic capabilities and identifying key regulatory nodes, representing a paradigm shift in omics data analysis that moves beyond simple correlation toward causal understanding [18] [19].

Core Computational Challenges in Multi-Omics Integration

Data Heterogeneity and Dimensionality

Multi-omics datasets comprise thousands of features generated through diverse laboratory techniques, leading to inconsistent data distributions and structures [17]. This heterogeneity manifests across multiple dimensions:

- Technical variation: Different omics platforms produce data with varying scales, distributions, and noise characteristics

- Temporal dynamics: Molecular processes operate at different timescales, creating integration challenges

- Spatial organization: Cellular compartmentalization adds spatial complexity to already complex datasets

The high-dimensional nature of these datasets, where features vastly exceed samples, creates statistical challenges that can lead to overfitting and reduced generalizability in predictive modeling [17].

Data Sparsity and Missing Values

Multi-omics datasets are frequently characterized by missing values due to experimental limitations, data quality issues, or incomplete sampling [17]. This sparsity arises from:

- Technical limitations: Detection thresholds vary across assay technologies

- Cost constraints: Comprehensive profiling of all molecular layers remains expensive

- Biological reality: Some molecular species exist at low abundances below detection limits

These missing values undermine the accuracy and reliability of predictive models if not properly addressed through sophisticated imputation methods [19].

Biological Interpretation and Causal Inference

Current machine learning methods primarily establish statistical correlations between genotypes and phenotypes but struggle to identify physiologically significant causal factors, limiting their predictive power across different conditions and domains [18]. The challenge lies in distinguishing correlation from causation within complex, interconnected biological networks where perturbations propagate nonlinearly.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Multi-Omics Data Integration for Predictive Modeling

| Challenge Category | Specific Technical Issues | Impact on Predictive Power |

|---|---|---|

| Data Heterogeneity | Diverse data types, formats, and measurement scales [19] | Reduces model generalizability across studies |

| Dimensionality | Features (P) >> Samples (N) high-dimensionality [17] | Increases overfitting risk; requires regularization |

| Sparsity | Missing values across omics layers [17] | Creates incomplete cellular pictures; biases predictions |

| Batch Effects | Technical variations between experiments [19] | Introduces non-biological variance; masks true signals |

| Biological Scale | Multi-scale data from molecules to organisms [18] | Creates integration complexity across biological hierarchies |

Methodological Approaches for Multi-Omics Integration

Classical Statistical and Machine Learning Methods

Traditional approaches for multi-omics integration include correlation-based methods, matrix factorization, and probabilistic modeling:

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and its extensions explore relationships between two sets of variables with the same samples, finding linear combinations that maximize cross-covariance [17]. Sparse and regularized generalizations (sGCCA/rGCCA) address high-dimensionality challenges and extend applicability to more than two datasets [17].

Matrix factorization techniques like JIVE and NMF decompose omics matrices into joint and individual components, reducing dimensionality while preserving shared and dataset-specific variations [17]. These methods effectively condense datasets into fewer factors that reveal patterns for identifying disease-associated biomarkers or cancer subtypes [17].

Probabilistic-based methods like iCluster incorporate uncertainty estimates and handle missing data more effectively than deterministic approaches, offering substantial advantages for flexible regularization [17].

Deep Learning and Hybrid Approaches

Recent advances have shifted focus from classical statistical to deep learning approaches, particularly generative methods:

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) have gained prominence since 2020 for tasks including imputation, denoising, and creating joint embeddings of multi-omics data [17]. These models learn complex nonlinear patterns through flexible architecture designs that can support missing data and denoising operations [17].

Hybrid neural networks like the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) integrate multi-omics data into GEMs to predict metabolic fluxes, combining strengths of mechanistic and data-driven approaches [20]. These frameworks handle the trade-off between biological constraints and predictive accuracy, outperforming purely mechanistic (pFBA) or machine learning (Random Forest) approaches on specific tasks [20].

AI-powered biology-inspired frameworks integrate multi-omics data across biological levels, organism hierarchies, and species to predict genotype-environment-phenotype relationships under various conditions [18].

Multi-Omics Integration Methodological Landscape

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models as Integration Frameworks

GEMs provide a structured mathematical framework for integrating multi-omics data by representing known metabolic reactions, enzymes, and genes within a stoichiometrically consistent model [19]. The evolution of human metabolic reconstructions from Recon 1 to Human1 represents increasing comprehensiveness in metabolic pathway coverage [19].

Key advantages of GEMs for multi-omics integration include:

- Structured knowledge base: Incorporates existing biochemical and genetic information

- Constraint-based modeling: Enables prediction of metabolic capabilities without kinetic parameters

- Context-specificization: Allows generation of tissue- or condition-specific models from omics data

- Gap analysis: Identifies inconsistencies between predicted and measured metabolic states

Table 2: Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Reconstructions for Human Metabolism

| Model Name | Key Features | Applications in Predictive Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Recon 1 | Early comprehensive reconstruction of human metabolism [19] | Foundation for studying human metabolic pathways |

| Recon 2 | Expanded coverage of human metabolic pathways [19] | Enhanced understanding of metabolic processes in health and disease |

| Recon 3D | Three-dimensional reconstruction integrating spatial information [19] | Context-specific view of human metabolism with cellular compartmentalization |

| Human1 | Unified human GEM with web portal (Metabolic Atlas) [19] | Identification of metabolic vulnerabilities in diseases like acute myeloid leukemia |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Data Preprocessing and Normalization Pipeline

Effective multi-omics integration requires meticulous data preprocessing to handle technical variations:

Quality control measures include outlier removal, artifact correction, and noise filtering to improve data quality [19]. Specific approaches vary by data type but typically involve:

- RNA-seq: Adapter trimming, quality filtering, and read alignment

- Proteomics: Peak detection, alignment, and normalization

- Metabolomics: Peak picking, alignment, and compound identification

Normalization methods standardize scale and range across samples or conditions [19]. Method selection depends on data type:

- Gene expression: Quantile normalization, TMM, RPKM, or CPM using DESeq2, edgeR, or limma [19]

- Proteomics: Central tendency-based normalization (mean/median intensity alignment) [19]

- Metabolomics: NOMIS normalization using optimal selection of multiple internal standards [19]

Batch effect correction addresses technical variations between experiments using tools like ComBat for microarray data or ComBat-seq for RNA-seq studies [19]. The RUVSeq tool removes unwanted variation in RNA-seq data through factor analysis-based approaches [19].

Hybrid Model Implementation Framework

The Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) protocol exemplifies hybrid approach implementation [20]:

- Model architecture design: Construct neural network layers with GEM embedding that maintains stoichiometric constraints

- Multi-omics input processing: Normalize and transform diverse omics inputs into compatible formats

- Constraint integration: Implement metabolic constraints as regularization terms or architectural components

- Conflict resolution: Implement strategies to mitigate conflicts between data-driven predictions and mechanistic constraints

- Model training: Optimize parameters balancing prediction accuracy and biological plausibility

- Validation: Compare predictions against experimental flux measurements and physiological constraints

Multi-Omics Integration Experimental Workflow

Computational Tools and Software Suites

Several standalone software suites provide comprehensive functionalities for metabolic reconstructions, modeling, and omics integration [19]:

- COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis): MATLAB/Python toolbox for constraint-based modeling [19]

- RAVEN (Reconstruction, Analysis, and Visualization of Metabolic Networks): MATLAB-based software suite for GEM reconstruction and curation [19]

- Microbiome Modeling Toolbox: Specialized tools for host-microbiome metabolic interactions [19]

- FastMM: Toolbox for personalized constraint-based metabolic modeling [19]

Databases and Knowledge Repositories

Table 3: Essential Databases for Multi-Omics Integration in Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Name | Primary Function | Application in Predictive Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| BiGG Database | Repository for benchmark GEMs with open access [19] | Reference models for simulation and comparison |

| Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) | Database for human and gut microbial metabolic reconstructions [19] | Host-microbiome metabolic interaction studies |

| Metabolic Atlas | Web portal for Human1 unified metabolic model [19] | Exploration of metabolic pathways and prediction of essential genes |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational reagents for multi-omics integration include:

- Reference metabolic models: Curated GEMs (Recon3D, Human1) providing biochemical frameworks [19]

- Normalization algorithms: DESeq2, edgeR, and limma for RNA-seq; NOMIS for metabolomics [19]

- Batch correction tools: ComBat and ComBat-seq for removing technical variations [19]

- Integration algorithms: CCA, NMF, and VAE implementations specialized for multi-omics data [17]

- Quality control metrics: Frameworks for assessing data quality and integration success [19]

The field of multi-omics integration is rapidly evolving toward foundation models and multimodal data integration capable of leveraging patterns across diverse biological contexts [17]. Future methodologies must better incorporate biological constraints to move beyond correlation toward causal inference, particularly for identifying novel molecular targets, biomarkers, and personalized therapeutic strategies [18].

The central challenge of multi-omics integration represents both a technical bottleneck and opportunity for advancing predictive power in biological models. By developing methods that effectively overcome data heterogeneity, sparsity, and interpretability limitations, researchers can unlock the full potential of multi-scale data to predict complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Continued advancement in this domain requires close collaboration between computational scientists, biologists, and clinical researchers to ensure that integration methodologies address biologically and clinically meaningful questions.

As integration methods mature, multi-omics approaches will increasingly enable predictive biology capable of accurately forecasting system responses to genetic, environmental, and therapeutic perturbations—ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine through enhanced predictive power derived from integrated molecular profiles.

Gene-Protein-Reaction Associations and Metabolic Flux

Gene-Protein-Reaction Associations (GPRs) form the critical genetic cornerstone of genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs). These logical Boolean statements (e.g., "Gene A AND Gene B → Protein Complex → Reaction") explicitly connect genes to the metabolic reactions they enable through the proteins they encode. GPRs delineate protein complexes (AND relationships) and isozymes (OR relationships), defining an organism's biochemical capabilities based on its genomic annotation [21]. Concurrently, Metabolic Flux represents the flow of metabolites through biochemical pathways, quantified as the rate of metabolite conversion per unit time. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a cornerstone constraint-based modeling approach, computes these fluxes by solving a linear programming problem that optimizes an objective function (e.g., biomass production) subject to stoichiometric constraints derived from the metabolic network: Sij • vj = 0, where Sij is the stoichiometric coefficient matrix and vj is the flux vector constrained between lower and upper bounds [22] [21].

The integration of these concepts creates a mechanistic bridge between genomic information and phenotypic outcomes. When framed within omics data integration research, GPRs and flux analysis transform static metabolic reconstructions into dynamic models capable of predicting how genetic perturbations (e.g., gene deletions) or environmental changes affect system-level metabolic behavior, with profound implications for drug target identification and biotechnology development [22] [23] [21].

Fundamental Principles and Relationships

The GPR-Metabolic Flux Axis

The relationship between GPRs and metabolic flux is governed by mechanistic constraints. GPR rules directly determine reaction capacity within flux models. When a gene is deleted, the GPR map identifies which reaction fluxes must be constrained to zero in the GSMM, mathematically represented by setting Vi^min = Vi^max = 0 for affected reactions [22]. This gene-reaction mapping enables in silico simulation of knockout mutants and prediction of essential genes—those whose deletion prevents growth or a target metabolic function.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling

| Parameter | Mathematical Representation | Biological Significance | Typical Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Sij • vj = 0 | Encodes network topology; mass-balance constraints | Genome annotation, biochemical databases [21] |

| Flux Constraints | Vi^min ≤ vi ≤ V_i^max | Thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints | Experimental measurements, sampling [22] |

| Gene Essentiality Threshold | grRatio < 0.01 | Predicts lethal mutations; potential drug targets | In silico deletion studies [21] |

| Objective Function | Maximize c^T v | Cellular goal (e.g., biomass, ATP production) | Physiological data, -omics measurements [22] [21] |

Advanced Computational Frameworks

Recent methodological advances extend beyond traditional FBA. Flux Cone Learning (FCL) leverages Monte Carlo sampling of the metabolic flux space defined by stoichiometric constraints to predict gene deletion phenotypes without requiring an optimality assumption [22]. This machine learning framework captures how gene deletions perturb the shape of the high-dimensional flux cone and correlates these geometric changes with experimental fitness measurements. FCL has demonstrated best-in-class accuracy (≈95%) for predicting metabolic gene essentiality in Escherichia coli, outperforming standard FBA predictions, particularly for higher organisms where cellular objectives are poorly defined [22].

Diagram 1: GPR to Metabolic Flux Logical Framework. This workflow illustrates how genetic information flows through GPR rules to constrain metabolic network functionality and predict phenotypic outcomes.

Integration with Multi-Omics Data

Network-Based Integration Strategies

The integration of GPR-constrained metabolic models with multi-omics data creates powerful frameworks for biological discovery and therapeutic development. Network-based integration approaches leverage biological networks (e.g., protein-protein interactions, metabolic reaction networks) as scaffolds to fuse heterogeneous omics data types [23]. These methods can be categorized into four primary computational paradigms:

- Network Propagation/Diffusion: Algorithms that simulate information flow through biological networks to identify regions significantly perturbed by experimental conditions or genetic variants.

- Similarity-Based Approaches: Methods that compute multi-dimensional similarity metrics across omics layers to detect conserved patterns.

- Graph Neural Networks: Deep learning architectures that operate directly on network structures to learn predictive features.

- Network Inference Models: Algorithms that reconstruct context-specific networks from omics data [23].

In drug discovery applications, these integration strategies have demonstrated particular value in identifying novel drug targets, predicting drug responses, and repurposing existing therapeutics. For example, integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and methylomic data within protein-protein interaction networks elucidated anthracycline cardiotoxicity mechanisms, identifying a core network of 175 proteins associated with mitochondrial and sarcomere dysfunction [24].

Chromatin Remodeling and Metabolic Regulation

Beyond direct metabolic applications, GPR-informed models interface with epigenetic regulation through metabolite-epigenome cross-talk. Chromatin-modifying enzymes utilize metabolic intermediates as substrates or cofactors, creating a direct mechanism for metabolic status to influence gene expression patterns [25]. For instance, acetyl-CoA—a central metabolic intermediate—serves as an essential cofactor for histone acetyltransferases, while S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) provides methyl groups for DNA and histone methylation [25]. This metabolic regulation of chromatin states creates feedback loops wherein metabolic fluxes influence epigenetic landscapes that in turn regulate metabolic gene expression through transcription factor accessibility [26].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Technologies for Metabolic Network Validation

| Omics Layer | Technology Examples | Applications in Metabolic Modeling | Integration Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Whole-genome sequencing, Mutant libraries | GPR curation, Essentiality validation [21] | Variant effect prediction, Regulation inference |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, PRO-seq | Context-specific model extraction [23] | Protein abundance correlation, Metabolic flux coupling |

| Proteomics | LC-MS, Protein arrays | Enzyme abundance constraints [24] | Absolute quantification, Post-translational modifications |

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, GC-MS | Flux validation, Network gap filling [21] | Compartmentalization, Rapid turnover |

| Epigenomics | MeDIP-seq, ChIP-seq | Metabolic gene regulation [24] | Causal inference, Cell-type specificity |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Reconstruction

The reconstruction of high-quality genome-scale metabolic models with accurate GPR associations follows a systematic workflow [21]:

Step 1: Draft Model Construction

- Obtain genome annotation using RAST or similar automated tools

- Generate initial GPR associations through homology transfer from template organisms (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus) using BLAST with thresholds of ≥40% identity and ≥70% query coverage

- Compile reaction list from ModelSEED automated pipeline and manual curation

Step 2: Metabolic Gap Filling

- Identify blocked reactions and pathway gaps using gapAnalysis tools in COBRA Toolbox

- Manually add missing reactions based on biochemical literature and phenotypic evidence

- Verify metabolic network connectivity to ensure synthesis of all biomass precursors

Step 3: Model Refinement and Validation

- Balance reaction stoichiometry for mass and charge

- Define biomass composition based on experimental measurements (e.g., macromolecular proportions: proteins 46%, DNA 2.3%, RNA 10.7%, lipids 3.4%)

- Validate model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions

This protocol was applied to reconstruct the Streptococcus suis iNX525 model, containing 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions, achieving 71.6-79.6% agreement with gene essentiality data from mutant screens [21].

Flux Cone Learning for Phenotype Prediction

The Flux Cone Learning methodology provides a machine learning alternative to traditional FBA for predicting gene deletion phenotypes [22]:

Step 1: Metabolic Space Sampling

- For each gene deletion, modify GPR rules in the GSMM to constrain associated reaction fluxes

- Use Monte Carlo sampling to generate multiple flux distributions (typically 100-500 samples) that satisfy stoichiometric constraints S·v = 0

- Repeat for all gene deletions in the training set

Step 2: Feature Engineering and Model Training

- Create feature matrix with dimensions (k × q) × n, where k = number of deletions, q = samples per deletion, n = number of reactions

- Label all samples from the same deletion cone with experimental fitness measurements

- Train supervised learning model (e.g., random forest classifier) to correlate flux distribution patterns with phenotypic outcomes

Step 3: Prediction and Validation

- Apply trained model to predict phenotypes for held-out gene deletions

- Aggregate sample-wise predictions using majority voting to generate deletion-wise classifications

- Compare predictions with experimental essentiality data across multiple organisms

This approach has demonstrated superior performance to FBA, particularly for predicting gene essentiality in higher organisms where optimality assumptions break down [22].

Diagram 2: Flux Cone Learning Workflow. This protocol uses Monte Carlo sampling of the metabolic flux space combined with machine learning to predict gene deletion phenotypes without optimality assumptions.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Drug Target Identification

GPR-constrained metabolic models enable systematic identification of essential metabolic genes as potential drug targets. In Streptococcus suis, model iNX525 identified 131 virulence-linked genes, with 79 participating in 167 metabolic reactions [21]. Through in silico gene essentiality analysis, 26 genes were predicted as essential for both bacterial growth and virulence factor production, highlighting high-priority targets that would simultaneously inhibit growth and pathogenicity. Among these, enzymes involved in capsular polysaccharide and peptidoglycan biosynthesis emerged as particularly promising for antibacterial development [21].

Similar approaches have been applied to cancer research, where metabolic dependencies of tumor cells are exploited for therapeutic intervention. In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), mutations in the PBRM1 chromatin remodeling subunit correlate with glycolytic dependency, creating a metabolic vulnerability that could be targeted therapeutically [26].

Network Pharmacology and Drug Repurposing

Network-based multi-omics integration facilitates the identification of novel drug indications and combination therapies. By mapping drug-protein interactions onto biological networks and overlaying multi-omics signatures from disease states, researchers can identify unexpected connections between drugs and disease modules [23]. For example, proteomic, transcriptomic, and methylomic analysis of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in human cardiac microtissues revealed conserved perturbation modules across four different drugs (doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin, daunorubicin), identifying mitochondrial and sarcomere function as common vulnerability pathways [24]. These network-based signatures were subsequently validated in cardiac biopsies from cardiomyopathy patients, demonstrating the translational potential of this approach.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Construction Tools | RAST, ModelSEED, COBRA Toolbox | Automated annotation, Draft reconstruction, Simulation | [21] |

| Simulation Environments | MATLAB, GUROBI Solver, Python | Numerical optimization, Flux calculation | [22] [21] |

| Experimental Validation | Chemically Defined Media (CDM), Mutant libraries | Growth phenotyping, Gene essentiality validation | [21] |

| Multi-omics Platforms | RNA-seq, LC-MS proteomics, MeDIP-seq | Context-specific model constraints, Validation data | [24] |

| Specialized Databases | TCDB, UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, Virulence Factor DB | Transporter annotation, Protein function, Pathogenicity | [21] |

The integration of GPR associations and metabolic flux analysis with multi-omics data represents a paradigm shift in metabolic network research. Current frontiers include the development of metabolic foundation models through representation learning on flux cones across diverse species [22], the incorporation of temporal and spatial dynamics into constraint-based models [23], and the deepening integration of epigenetic regulation mechanisms that link metabolic status to gene expression [26] [25].

Future methodological advancements will need to address several critical challenges: improving computational scalability for large-scale multi-omics integration, maintaining biological interpretability in increasingly complex models, and establishing standardized frameworks for method evaluation [23]. Furthermore, non-enzymatic chromatin modifications derived from metabolism represent an emerging layer of regulation whose systematic incorporation into metabolic models remains largely unexplored [25].

As these technologies mature, GPR-constrained metabolic models integrated with multi-omics data will become increasingly central to both basic biological discovery and translational applications, particularly in drug development where they offer a powerful framework for identifying therapeutic targets, predicting drug toxicity, and understanding complex disease mechanisms. The continued refinement of these approaches promises to further bridge the gap between genomic information and phenotypic expression, ultimately advancing predictive biology and precision medicine.

Methodologies and Applications: Techniques for Integrating Omics Data into Metabolic Models

The integration of omics data into mathematical frameworks is essential for fully leveraging the potential of high-throughput biological data to understand complex systems [19]. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a robust constraint-based framework for simulating metabolic networks and predicting phenotypic behaviors from genotypic information [19]. Within this field, specialized computational pipelines have been developed to contextualize generic metabolic models using omics data, enabling researchers to study tissue-specific metabolism, identify metabolic alterations in disease, and predict drug targets [27].

This technical guide focuses on three core integration techniques: GIMME (Gene Inactivity Moderated by Metabolism and Expression), iMAT (integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool), and INIT (Integrative Network Inference for Tissues) [27]. Although the search results do not specifically mention a pipeline named "INTEGRATE," the well-documented INIT algorithm represents a foundational approach for tissue-specific model reconstruction and is included here as a core technique. These methods represent distinct philosophical and mathematical approaches for creating context-specific metabolic models from transcriptomic data and genome-scale reconstructions.

The following sections provide an in-depth analysis of each method's underlying principles, mathematical formulations, implementation protocols, and comparative strengths and limitations, framed within the broader context of omics data integration in metabolic network research.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

GIMME (Gene Inactivity Moderated by Metabolism and Expression)

GIMME uses gene expression data to create context-specific models by minimizing the flux through reactions associated with lowly expressed genes while maintaining a specified biological objective [27]. The algorithm first defines a threshold to classify genes as expressed or unexpressed. Reactions linked to genes below this threshold are penalized in the optimization. GIMME finds a flux distribution that satisfies metabolic constraints while minimizing the weighted sum of fluxes through penalized reactions.

The objective function is formulated as:

[ \min \sum{i=1}^{R} wi |v_i| ]

where (vi) represents the flux of reaction (i), and (wi) is a weight assigned based on gene expression data. Reactions associated with low expression levels receive higher weights, incentivizing the algorithm to minimize their fluxes. The solution must satisfy the typical metabolic constraints: (\mathbf{S \cdot v = 0) and (\mathbf{v{min} \leq v \leq v{max}}), while achieving a specified fraction of the optimal growth rate or other biological objectives [27].

iMAT (integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool)

iMAT adopts a constraint-based approach that does not require pre-defining an cellular objective function, making it particularly suitable for multicellular organisms and tissues where the primary biological objective may not be clearly defined [27]. The method operates by categorizing reactions into highly expressed (H) and lowly expressed (L) sets based on transcriptomic data and a user-defined threshold.

iMAT formulates a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem to maximize the number of reactions active in the high-expression set and inactive in the low-expression set:

[ \max \left( \sum{i \in H} yi + \sum{i \in L} (1 - yi) \right) ]

where (yi) is a binary variable indicating whether reaction (i) is active [27]. The solution satisfies stoichiometric constraints (\mathbf{S \cdot v = 0) and flux bound constraints (\mathbf{v{min} \leq v \leq v{max}}), with the additional constraint that (vi \neq 0) if (y_i = 1).

INIT (Integrative Network Inference for Tissues)

INIT algorithm is designed specifically for building tissue-specific models from global human metabolic reconstructions [27]. It uses high-throughput proteomic or transcriptomic data to determine reaction activity states. Unlike binary classification approaches, INIT can incorporate quantitative confidence scores derived from experimental data.

The algorithm maximizes the total weight of included reactions while producing a functional network capable of generating biomass precursors:

[ \max \left( \sum{i=1}^{R} wi \cdot y_i \right) ]

where (wi) represents the confidence weight for reaction (i), and (yi) indicates whether the reaction is included in the context-specific model [27]. The resulting network must satisfy metabolic constraints and maintain functionality for producing tissue-specific essential metabolites.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Integration Methodologies

| Feature | GIMME | iMAT | INIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Minimize flux through low-expression reactions | Maximize consistency between flux state and expression state | Maximize inclusion of high-confidence reactions |

| Expression Data Usage | Continuous values to weight fluxes | Binary classification (high/low) | Quantitative confidence scores |

| Mathematical Formulation | Linear programming | Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) | Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) |

| Requires Growth Objective | Yes | No | No (but requires functionality test) |

| Key Applications | Adaptive evolution, tissue-specific modeling [27] | Tissue-specific activity mapping [27] | Tissue-specific model reconstruction [27] |

| Implementation Tools | COBRA Toolbox [19] | COBRA Toolbox, RAVEN [19] | Matlab-based implementations |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Workflow for Context-Specific Model Extraction

The process of generating context-specific models using GIMME, iMAT, and INIT follows a systematic workflow with both shared and method-specific steps. The following diagram illustrates the generalized protocol for integrating transcriptomic data with genome-scale metabolic reconstructions.

Detailed Methodological Protocols

GIMME Implementation Protocol

Data Preprocessing: Normalize transcriptomic data using appropriate methods such as quantile normalization for microarray data or DESeq2/edgeR for RNA-seq data [19]. Map gene identifiers to those used in the metabolic model.

Threshold Determination: Calculate a expression threshold based on the distribution of expression values. This can be a percentile-based threshold (e.g., lowest 25%) or an absolute threshold derived from control samples.

Reaction Classification: Identify reactions associated with genes below the expression threshold. For reactions associated with multiple genes, apply gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules to determine the expression state.

Weight Assignment: Assign weights to low-expression reactions, typically inversely proportional to their expression levels. Highly expressed reactions receive zero weight.

Optimization Setup: Define the metabolic constraints, including the stoichiometric matrix (\mathbf{S}), flux bounds (\mathbf{v{min}}) and (\mathbf{v{max}}), and the biological objective (e.g., biomass production).

Model Extraction: Solve the linear programming problem to minimize the weighted sum of fluxes through penalized reactions while maintaining a specified fraction of the optimal objective value.

Validation: Assess the functionality of the extracted model by testing its ability to produce known metabolic requirements and compare predictions with experimental data where available.

iMAT Implementation Protocol

Expression Data Processing: Normalize transcriptomic data and map to metabolic genes. Determine thresholds for classifying reactions as highly expressed (H) or lowly expressed (L) using statistical methods or percentile cuts.

Reaction Categorization: Apply thresholds to classify each reaction into H, L, or unclassified categories based on associated gene expression and GPR rules.

MILP Formulation:

- Create binary variables (yi) for each reaction indicating whether it is active ((vi \neq 0)).

- Add constraints linking binary variables to continuous flux variables using big-M constraints: (vi^{min} \cdot yi \leq vi \leq vi^{max} \cdot y_i).

- Define the objective function to maximize the sum of active states for H reactions and inactive states for L reactions.

Network Extraction: Solve the MILP problem to obtain a flux distribution consistent with the expression data. Extract the active reaction set from the solution.

Functional Analysis: Verify that the extracted network can perform essential metabolic functions and compare with tissue-specific metabolic capabilities documented in the literature.

INIT Implementation Protocol

Confidence Scoring: Assign confidence scores to reactions based on proteomic or transcriptomic data from resources like the Human Protein Atlas. Scores can be derived from detection calls or expression levels.

Metabolic Requirements Definition: Define the metabolic functionality that the tissue-specific model must maintain, such as production of essential biomass components or known secreted metabolites.

MILP Problem Setup:

- Create binary variables (y_i) for reaction inclusion.

- Formulate constraints to ensure the network can produce all required metabolites.

- Define the objective function to maximize the sum of confidence scores for included reactions.

Model Reconstruction: Solve the optimization problem to obtain a functional metabolic network enriched for high-confidence reactions.

Gap Filling and Curation: Perform manual curation to address any gaps in essential metabolic pathways and validate against known tissue metabolic functions.

Successful implementation of GIMME, iMAT, and INIT pipelines requires both computational tools and biological data resources. The following table catalogues essential components for researchers applying these integration techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Metabolic Modeling Pipelines

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose | Applicable Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Model Databases | BiGG Models [19], Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) [19], HMR [19], Recon3D [19] | Provide curated genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for various organisms | All |

| Modeling Software & Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox [19], RAVEN Toolbox [19], ModelSEED [28], CarveMe [28] | Implement constraint-based reconstruction, simulation, and analysis algorithms | All |

| Expression Data Repositories | GEO, ArrayExpress, TCGA, GTEx, Human Protein Atlas | Source tissue- or condition-specific transcriptomic and proteomic data | All |

| Normalization Methods | Quantile normalization [19], ComBat [19], RUVSeq [19], DESeq2 [19] | Preprocess omics data to remove technical artifacts and make samples comparable | All |

| Optimization Solvers | Gurobi, CPLEX, GLPK | Solve linear and mixed-integer programming problems in the optimization steps | All |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction Mapping | Metabolic atlas [19], BiGG [19] | Standardize associations between genes, enzymes, and metabolic reactions | All |

Comparative Performance and Applications

Method Evaluation in Biological Contexts

Systematic evaluation of transcriptomic integration methods using E. coli and S. cerevisiae datasets has revealed that no single method consistently outperforms others across all conditions and validation metrics [27]. The performance varies depending on the biological system, data quality, and validation criteria.

In many cases, simple flux balance analysis with growth maximization and parsimony criteria produced predictions comparable to or better than methods incorporating transcriptomic data [27]. This highlights the challenge of establishing direct correspondence between transcript levels and metabolic fluxes due to post-transcriptional regulation, enzyme kinetics, and metabolic control mechanisms.

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of Integration Methods

| Performance Metric | GIMME | iMAT | INIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness to Noise | Moderate | High | High |

| Computational Complexity | Low (LP) | High (MILP) | High (MILP) |

| Dependence on Thresholds | High | High | Moderate |

| Sensitivity to Objective Function | High | Low | Low |

| Validation with Experimental Fluxes | Variable [27] | Variable [27] | Not fully evaluated |

Advanced Applications and Integration Frontiers

These core integration techniques have enabled significant advances in metabolic modeling applications:

Tissue-Specific Modeling for Human Disease: iMAT and INIT have been extensively used to create cell-type specific models for investigating cancer metabolism, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases [19] [27].

Host-Microbiome Interactions: Integrated host-microbe metabolic models built using these pipelines have revealed metabolic cross-feeding relationships and identified potential therapeutic targets [28].

Multi-omics Biomarker Discovery: Combining these integration methods with machine learning has identified metabolic features associated with clinical outcomes, such as radiation resistance in cancer [29].

Metabolic Network Inference: Recent approaches like MINIE leverage time-series multi-omics data to infer regulatory networks across molecular layers, extending beyond static integration methods [6].

Technical Considerations and Implementation Challenges

Critical Parameter Selection

The performance of GIMME, iMAT, and INIT is highly sensitive to parameter choices, particularly expression thresholds. Studies have shown that varying threshold values can significantly impact the size and functionality of extracted models [30]. The following diagram illustrates the decision process for parameter optimization in method selection.

Data Quality and Preprocessing Requirements

Successful implementation requires careful attention to data preprocessing:

Normalization Strategy Selection: Choice of normalization method (e.g., quantile normalization, RUVSeq, ComBat) should align with data generation technology and experimental design [19].

Batch Effect Correction: Multi-omics studies frequently encounter batch effects requiring specialized correction methods like ComBat to remove technical variation while preserving biological signals [19] [31].

Missing Data Imputation: Metabolic models are particularly sensitive to incomplete data. Advanced imputation methods including matrix factorization and deep learning approaches may be necessary for handling missing values [31].

Emerging Methodological Extensions

Recent advances have built upon these core methodologies:

Machine Learning Integration: Hybrid approaches like MINN (Metabolic-Informed Neural Network) combine GEMs with neural networks to improve flux prediction accuracy while maintaining biological constraints [20].

Multi-omics Network Frameworks: Unified frameworks integrating lipids, metabolites, and proteins enable comprehensive multi-omics analysis and biomarker discovery [32].

Dynamic Integration Methods: Approaches like MINIE leverage time-series multi-omics data to infer causal regulatory relationships across molecular layers, addressing temporal dynamics in metabolic regulation [6].

GIMME, iMAT, and INIT represent foundational methodologies in the constraint-based modeling landscape that continue to enable important discoveries in systems biology and precision medicine. While each method employs distinct mathematical strategies for integrating transcriptomic data into metabolic models, they share the common goal of creating biologically realistic, context-specific metabolic networks.

The selection of an appropriate integration pipeline depends on multiple factors including biological context, data availability, computational resources, and research objectives. Methodological advances continue to address current limitations in data integration, with emerging approaches incorporating machine learning, dynamic modeling, and multi-omics network frameworks pushing the boundaries of metabolic modeling capabilities.

As the field progresses toward more comprehensive multi-omics integration, these core techniques provide the foundation upon which next-generation metabolic modeling approaches are being built, ultimately enhancing our ability to translate genomic information into mechanistic understanding of metabolic physiology and disease.

Leveraging Transcriptomics and Proteomics to Constrain Reaction Fluxes

Constraint-based modeling (CBM) serves as a powerful computational framework for predicting cellular physiology, including metabolic flux distributions, under different environmental and genetic conditions [33]. These models have found extensive applications in metabolic engineering, drug discovery, and understanding disease mechanisms [33]. Traditional simulation methods like parsimonious Flux Balance Analysis (pFBA) predict fluxes by maximizing biomass yield and minimizing total flux without incorporating molecular-level omics data [33]. However, the rising availability of high-throughput transcriptomics and proteomics data presents an opportunity to refine these models by incorporating regulatory information.