Harnessing Genetic Algorithms for Advanced Metabolic Strain Design: From Foundations to Future Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genetic algorithms (GAs) for optimizing microbial strain designs in metabolic engineering.

Harnessing Genetic Algorithms for Advanced Metabolic Strain Design: From Foundations to Future Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of genetic algorithms (GAs) for optimizing microbial strain designs in metabolic engineering. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational principles of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) and flux balance analysis that underpin GA applications. The content delves into methodological implementations for identifying optimal gene knockout strategies, discusses critical parameter optimization and convergence challenges, and validates GA performance against alternative machine learning approaches like reinforcement learning. By synthesizing current research and practical case studies, particularly in E. coli and S. cerevisiae, this guide serves as a strategic resource for advancing bio-based production of pharmaceuticals and chemicals.

The Bedrock of In Silico Metabolic Engineering: GEMs and Optimization Principles

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the complete metabolic network of an organism. They quantitatively define the relationship between genotype and phenotype by contextualizing different types of Big Data, including genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics [1]. A GEM computationally describes a whole set of stoichiometry-based, mass-balanced metabolic reactions using gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations formulated from genome annotation data and experimental information [2]. Since the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae was reported in 1999, models have been developed for an increasing number of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [2].

The core structure of a GEM can be mathematically represented as a stoichiometric matrix (S matrix), where columns represent reactions, rows represent metabolites, and each entry is the stoichiometric coefficient of a particular metabolite in a reaction [3]. This mathematical format enables computational prediction of multi-scale phenotypes through optimization techniques, most commonly flux balance analysis (FBA) [3].

Table 1: Core Components of a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

| Component | Description | Function in the Model |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolites | Small molecules participating in metabolic reactions | Represented as rows in the stoichiometric matrix; represent network nodes |

| Reactions | Biochemical transformations between metabolites | Represented as columns in the stoichiometric matrix; include stoichiometry |

| Genes | Genetic elements encoding metabolic enzymes | Linked to reactions through GPR rules |

| GPR Rules | Gene-Protein-Reaction associations | Boolean rules defining gene requirements for each reaction |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | Mathematical representation of the metabolic network | Enables constraint-based simulation and flux prediction |

GEM Reconstruction and Simulation

Reconstruction Pipeline

GEM reconstruction involves systematic steps from genomic data to a functional model. Automatic and semi-automated tools leverage annotated genome sequences mapped to metabolic knowledge bases like the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [3]. The process involves draft model generation from genome annotation, network gap filling to ensure functionality, manual curation to incorporate experimental data, and model validation against known physiological capabilities [1] [2].

As of 2019, GEMs have been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms (5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryotes), with 183 organisms subjected to manual reconstruction [2]. High-quality models for scientifically and industrially important organisms have undergone multiple iterations. For example, the E. coli GEM has progressed from iJE660 to iML1515, now containing information on 1,515 open reading frames with 93.4% accuracy for gene essentiality simulation under minimal media with different carbon sources [2].

Simulation Methods

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most widely used approach to simulate GEMs [3]. FBA predicts metabolic flux distributions by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production) while respecting constraints including the stoichiometric matrix, steady-state assumption for internal metabolites, and limits on nutrient uptake rates and enzyme capacities [3]. FBA and related analysis methods are available through computational tools like the COBRApy package in Python or the COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB [3].

Other simulation methods include:

- 13C-metabolic flux analysis (13C MFA): Uses labeled isotope tracers to predict metabolic fluxes [1]

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Predicts metabolic fluxes under non-steady-state conditions [1]

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction [4]

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Framework for Strain Design

Principles of Genetic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are optimization techniques inspired by natural biological evolution, based on concepts of natural selection and genetic inheritance [5]. In metabolic engineering, GAs solve the challenging problem of identifying optimal genetic interventions to achieve desired production phenotypes [4]. The key characteristics of GAs include: (i) a genetic representation of solutions, (ii) populations of individuals as evolutionary communities, (iii) a fitness function for evaluating solution quality, and (iv) operators that generate new populations from existing ones [4].

For strain design optimization, GAs are particularly advantageous because they can handle complex, non-linear engineering objectives, identify gene target-sets according to logical GPR associations, minimize the number of network perturbations, and incorporate non-native reactions [4]. They effectively navigate the nested, bilevel-optimization problem inherent to metabolic engineering, where the outer problem optimizes an engineering objective (e.g., product yield) and the inner problem returns the microbial phenotype for a given intervention strategy [4].

Implementation for Metabolic Engineering

In the GA framework for strain design, an individual represents a set of proposed reaction or gene deletions, typically encoded as a binary string where each bit corresponds to a potential deletion target [4]. The algorithm evolves a population of these intervention sets over generations through selection, crossover, and mutation operations [4] [6].

The fitness of each individual is evaluated by simulating the engineered metabolic network using methods like FBA or Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) and calculating the resulting production yield of the target compound [4]. Parameter sensitivity is crucial, as premature convergence to sub-optimal solutions can occur if optimization parameters are not properly adapted to the specific problem [4].

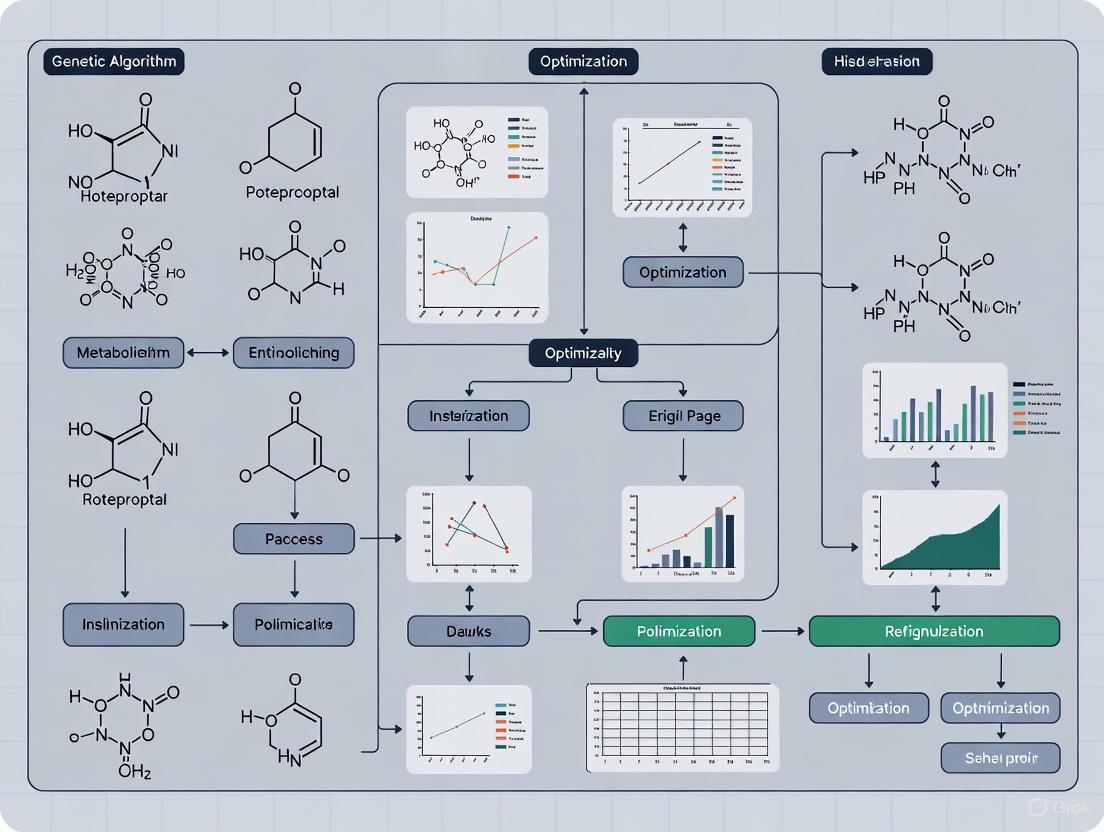

Diagram 1: Genetic Algorithm Workflow for Strain Design. The process iteratively evolves intervention sets toward optimal production.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Strain Optimization Using Genetic Algorithms

Objective: Identify optimal gene knockout strategies for enhanced succinate production in E. coli using a GA framework.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli (e.g., iML1515)

- COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) or COBRApy (Python)

- Genetic algorithm implementation (custom or OptGene-based)

- Computing hardware with sufficient memory for repeated model simulations

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GEM Analysis and Strain Design

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB software for constraint-based modeling | Provides FBA, FVA, and strain design algorithms [3] |

| COBRApy | Python package for constraint-based analysis | Enables simulation and manipulation of GEMs [3] |

| OptGene | Genetic algorithm framework for strain design | Identifies knockout strategies for overproduction [4] |

| Gurobi/CPLEX | Mathematical optimization solvers | Solves linear programming problems in FBA |

| KEGG Database | Metabolic pathway knowledgebase | Source of reaction information for model reconstruction [3] |

Procedure:

Problem Formulation (Day 1)

- Define the engineering objective: Maximize succinate production rate

- Define the cellular objective: Often biomass formation

- Set the environmental conditions: Specify carbon source, oxygen availability, etc.

GA Parameter Configuration (Day 1)

- Set population size (typically 100-500 individuals)

- Define number of generations (typically 50-200)

- Set mutation rate (typically 0.01-0.05)

- Set crossover rate (typically 0.7-0.9)

- Define number of deletions per individual (ND) based on desired intervention complexity

Initialization (Day 1)

- Generate initial population of random intervention sets

- Encode each intervention set as a binary string representing potential gene/reaction deletions

Fitness Evaluation (Iterative) For each individual in the population:

- Apply the proposed knockouts to the base metabolic model

- Simulate the mutant using FBA with maximized product formation as objective

- Record the production rate as the fitness value

Evolutionary Operations (Iterative)

- Selection: Select parents with probability proportional to fitness

- Crossover: Create offspring by combining parts of parent intervention sets

- Mutation: Randomly flip bits in offspring intervention sets with low probability

- Replacement: Form new generation from best parents and offspring

Termination and Validation (Final Day)

- Terminate after specified generations or when convergence is achieved

- Validate top strategies by comparing predicted yields with experimental data

- Analyze flux distributions of optimal strains to understand metabolic rewiring

Troubleshooting:

- If convergence is too rapid, increase mutation rate or population size

- If optimization stagnates, consider expanding the target space of possible interventions

- If predictions lack biological feasibility, add thermodynamic constraints

Protocol: Multi-Strain GEM Reconstruction and Analysis

Objective: Create a pan-genome scale metabolic model to understand metabolic diversity across multiple strains of a bacterial species.

Background: Multi-strain reconstructions help elucidate conserved and strain-specific metabolic capabilities, with applications in understanding pathogenesis and host adaptation [1]. For example, Monk et al. created a multi-strain GEM from 55 individual E. coli models, defining a "core" model (intersection of all models) and "pan" model (union of all models) [1].

Procedure:

Genome Collection and Annotation

- Collect genome sequences for all target strains

- Perform consistent functional annotation across all genomes

Draft Model Reconstruction

- Reconstruct individual GEMs for each strain using automated tools

- Map reactions and metabolites to a consistent namespace

Pan-Model Construction

- Identify core reactions present in all strains

- Identify accessory reactions present in subsets of strains

- Create unified pan-model encompassing all metabolic capabilities

Comparative Analysis

- Simulate growth capabilities across different nutrient conditions

- Identify strain-specific essential genes and reactions

- Correlate metabolic capabilities with phenotypic traits

Diagram 2: Multi-Strain GEM Reconstruction Workflow. This process enables comparative analysis of metabolic capabilities across strains.

Applications in Biotechnology and Biomedicine

GEMs have diverse applications across industrial biotechnology and biomedical research. Key application areas include:

Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

GEMs are extensively used to design microbial cell factories for production of biofuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. Model-driven approaches identify key genetic modifications that redirect metabolic flux toward desired products [2]. For example, GEMs of S. cerevisiae and E. coli have been used to optimize production of compounds like succinate and L-tryptophan [4] [7] [8].

Drug Target Identification

In infectious disease research, GEMs of pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis help identify potential drug targets by simulating gene essentiality in different conditions [2]. Comparative analysis of metabolic fluxes between in vivo and in vitro conditions reveals conditionally essential pathways that represent attractive therapeutic targets [2].

Host-Microbe Interactions

GEMs can be extended to model metabolic interactions between hosts and their associated microbiomes. Integrated models of human cells and microbial pathogens elucidate metabolic dependencies during infection [1] [2]. The Human Microbiome Project has generated terabytes of data that can be contextualized using GEMs to understand how niche microbiota affect their hosts [1].

Pan-Reactome Analysis

Multi-strain GEMs enable pan-reactome analysis, identifying conserved and variable metabolic capabilities across strains [1] [2]. This approach has been applied to study metabolic diversity in Salmonella (410 strains), S. aureus (64 strains), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22 strains) [1].

Table 3: Representative GEMs for Model Organisms

| Organism | Model Name | Genes | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | iML1515 | 1,515 | Metabolic engineering, core metabolism [2] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Yeast 7 | 1,175 | Bioproduction, eukaryotic biology [2] [8] |

| Bacillus subtilis | iBsu1144 | 1,144 | Enzyme production, Gram-positive model [2] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | iEK1101 | 1,101 | Drug target identification [2] |

| Methanosarcina acetivorans | iMAC868 | 868 | Methanogenesis, archaeal metabolism [2] |

Integration with Advanced Computational Methods

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Recent advances integrate GEMs with machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches. Reinforcement learning (RL) methods have been developed to optimize enzyme expression levels without prior knowledge of the metabolic network structure [7]. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) is particularly suited for leveraging parallel experiments, such as multi-well plate cultivations [7].

These AI approaches learn from experimental data to suggest strain modifications, effectively automating parts of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [7]. When combined with GEMs, they can account for cellular regulation beyond mass balance and thermodynamic constraints [7].

Multi-Scale Modeling

Next-generation GEMs incorporate additional cellular processes beyond metabolism. ME-models (Models with Expression) include macromolecular expression constraints, enabling more accurate predictions of proteome allocation and resource balance [1]. Models with kinetic constraints integrate enzyme turnover numbers and metabolic concentrations to predict dynamic behaviors [7] [9].

These advanced models provide a more comprehensive view of cellular physiology, enabling more reliable prediction of metabolic engineering outcomes and better understanding of fundamental biological principles governing metabolic operation.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, serving as a cornerstone technique for predicting metabolic phenotypes in systems biology and metabolic engineering [10]. This constraint-based method calculates the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks, enabling researchers to predict critical biological outcomes such as microbial growth rates or the production of biotechnologically important metabolites without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data [10] [11]. FBA has become particularly valuable for analyzing genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions, which contain all known metabolic reactions for specific organisms and the genes encoding each enzyme [10].

The fundamental principle underlying FBA is the application of physicochemical constraints to narrow down the possible metabolic flux distributions until an optimal phenotype is identified according to a specified biological objective [10]. Unlike kinetic models that require detailed enzyme parameter data, FBA differentiates itself by relying primarily on the stoichiometry of metabolic reactions and capacity constraints, making it particularly suitable for large-scale network analysis where comprehensive kinetic data is unavailable [10] [11]. This capability has established FBA as an indispensable tool for harnessing the knowledge encoded in metabolic models, with applications spanning microbial strain improvement, drug target identification, and understanding evolutionary dynamics [12] [13].

Mathematical Foundations and Core Principles

Stoichiometric Representation of Metabolism

The first step in FBA involves mathematically representing metabolic reactions through a stoichiometric matrix (S) of size m×n, where m represents the number of metabolites and n represents the number of reactions in the network [10]. Each column in this matrix corresponds to a specific biochemical reaction, while each row represents a unique metabolite. The entries in each column are the stoichiometric coefficients of the metabolites participating in a reaction, with negative coefficients indicating metabolites consumed and positive coefficients indicating metabolites produced [10]. Reactions not involving particular metabolites receive a coefficient of zero, resulting in a characteristically sparse matrix since most biochemical reactions involve only a few metabolites [10].

The system of mass balance equations at steady state (dx/dt = 0) is represented as: Sv = 0 where v is the vector of reaction fluxes of length n, and x is the vector of metabolite concentrations of length m [10]. This equation represents the core constraint of FBA, ensuring that the total production and consumption of each metabolite is balanced. For any realistic large-scale metabolic model where reactions outnumber metabolites (n > m), this system of equations is underdetermined, meaning no unique solution exists without additional constraints [10].

Constraints and Objective Functions in FBA

FBA incorporates two primary types of constraints. The stoichiometric matrix imposes flux balance constraints that maintain mass conservation, while separately defined upper and lower bounds (vmin and vmax) define the maximum and minimum allowable fluxes for each reaction [10] [11]. These balances and bounds collectively define the space of allowable flux distributions through the metabolic network.

To identify a single solution within this constrained space, FBA requires the definition of a biological objective function formulated as a linear combination of fluxes: Z = c^Tv, where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective [10]. In practice, when maximizing or minimizing a single reaction, c becomes a vector of zeros with a value of one at the position of the reaction of interest [10]. Common biological objectives include biomass production (simulating growth), ATP production, or synthesis of specific target metabolites [10] [12].

Table 1: Key Components of the FBA Mathematical Framework

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | S | m×n matrix of metabolite coefficients | Defines network structure and mass balance constraints |

| Flux Vector | v | n×1 vector of reaction fluxes | Variables to be optimized |

| Capacity Constraints | vmin, vmax | Lower and upper flux bounds | Defines physiological limits |

| Objective Coefficients | c | n×1 vector of weights | Defines biological objective to optimize |

Optimization via Linear Programming

The complete FBA problem can be formulated as a linear programming optimization problem [10] [11]: Maximize (or Minimize): Z = c^Tv Subject to: Sv = 0 vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

This system is solved using linear programming algorithms, with the simplex method being particularly suitable as it guarantees basic feasible solutions that satisfy the optimality conditions [11] [14]. The output is a specific flux distribution (v) that maximizes or minimizes the objective function while satisfying all imposed constraints [10].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Implementation

Core FBA Protocol

The standard FBA protocol involves several methodical steps, beginning with network reconstruction and culminating in flux prediction and validation [10] [11]:

Network Reconstruction: Compile all known metabolic reactions for the target organism from databases such as KEGG or EcoCyc, including gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations [13].

Stoichiometric Matrix Formulation: Construct the S matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, with stoichiometric coefficients indicating consumption (negative) or production (positive) [10].

Constraint Application: Define the steady-state constraint (Sv = 0) and set physiologically relevant flux bounds (vmin, vmax) based on environmental conditions or enzyme capacities [10] [11].

Objective Function Definition: Specify the biological objective, typically biomass maximization for growth prediction or metabolite production for biotechnological applications [10] [12].

Linear Programming Solution: Utilize optimization algorithms (e.g., simplex method) to identify the flux distribution that optimizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [10] [14].

Solution Validation: Compare predictions with experimental data, such as measured growth rates or metabolite secretion profiles, to validate model accuracy [10] [13].

Implementation with COBRA Toolbox

The COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox provides a standardized implementation of FBA and related methods in MATLAB [10]. The following code demonstrates a basic FBA implementation:

For anaerobic conditions, simply constrain oxygen uptake to zero:

Table 2: Sample FBA Results for E. coli under Different Conditions

| Condition | Objective | Growth Rate (hr⁻¹) | Glucose Uptake (mmol/gDW/hr) | Oxygen Uptake (mmol/gDW/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic [10] | Biomass Maximization | 1.65 | 18.5 | ~15.5 |

| Anaerobic [10] | Biomass Maximization | 0.47 | 18.5 | 0 |

| Succinate Overproduction [12] | Succinate Maximization | 0.31 | 18.5 | Variable |

Advanced Implementation: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

Standard FBA solutions are often degenerate, with multiple flux distributions yielding the same optimal objective value. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) addresses this by determining the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while maintaining optimal or sub-optimal objective function values [14]. The FVA problem can be formulated as:

For each reaction i: Maximize/Minimize: vi Subject to: Sv = 0 c^Tv ≥ μZ0 (where μ is the optimality factor) vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Traditional FVA requires solving 2n+1 linear programs (n = number of reactions), but improved algorithms reduce computational burden by utilizing basic feasible solution properties to eliminate redundant optimizations [14]. The following pseudocode illustrates an efficient FVA implementation:

The solution inspection procedure checks if flux variables in intermediate solutions are at their upper or lower bounds, eliminating the need to solve individual optimization problems for those reactions [14].

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for FBA Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Software | Function/Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Toolboxes [10] | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) | FBA and related methods | SBML support, extensive model repository |

| COBRApy (Python) [14] | Python implementation of COBRA | Integration with scientific Python stack | |

| FastFVA [14] | High-performance FVA | Parallel processing for large models | |

| Model Databases [10] | BiGG Models | Curated metabolic models | Standardized naming conventions |

| KEGG [13] | Pathway and reaction data | Comprehensive biochemical database | |

| EcoCyc [13] | E. coli database | Detailed enzyme and pathway information | |

| Modeling Formats [10] | Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | Model exchange format | Community standard, tool interoperability |

| Optimization Solvers [11] [14] | Gurobi, CPLEX | Linear programming | High-performance optimization algorithms |

| GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) | Open-source LP solver | Free alternative for basic implementations |

Advanced Applications in Metabolic Engineering

Integration with Genetic Algorithms for Strain Design

FBA serves as the foundational evaluation method within genetic algorithm frameworks for optimal mutant strain design [12]. In this context, FBA predicts metabolic phenotypes for candidate knockout strains, while genetic algorithms explore the combinatorial space of gene deletions to identify optimal genetic modifications that enhance production of target metabolites while maintaining microbial viability [12].

The RBI (Reliability-Based Integrating) algorithm represents an advanced approach that integrates gene regulatory networks with metabolic networks using FBA as the core simulation engine [12]. This integration enables more accurate prediction of metabolic phenotypes after genetic modifications by accounting for complex regulatory interactions, including Boolean rules in empirical gene regulatory networks and GPR rules [12]. Applications have successfully enhanced succinate and ethanol production in E. coli and S. cerevisiae while maintaining strain survival [12].

Objective Function Identification with TIObjFind

Selecting appropriate biological objectives remains a challenge in FBA applications. The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework addresses this by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to infer cellular objectives from experimental flux data [13]. This approach:

Formulates objective identification as an optimization problem that minimizes differences between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [13].

Maps FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) to enable pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions [13].

Applies a minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization [13].

This methodology has demonstrated effectiveness in case studies including Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and multi-species isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) systems, successfully capturing stage-specific metabolic objectives and improving alignment with experimental data [13].

Pharmaceutical Applications and Drug Target Identification

FBA facilitates drug target identification by predicting essential reactions in pathogens under infection conditions [12]. By simulating gene knockout effects, researchers can identify metabolic chokepoints whose inhibition would disrupt pathogen growth while minimizing human toxicity [12]. The method has been applied to understand cellular responses to varying conditions and identify potential targets in various disease models [12].

Table 4: FBA Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

| Application Domain | Methodology | Key Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Succinate Production [12] | RBI algorithm with FBA | Enhanced succinate production in E. coli while maintaining viability | [12] |

| Ethanol Optimization [12] | Regulatory-metabolic modeling | Improved ethanol yield in S. cerevisiae | [12] |

| Drug Target Identification [12] | Gene essentiality analysis | Identification of pathogen-specific essential reactions | [12] |

| Dynamic Bioprocess Optimization [13] | TIObjFind framework | Stage-specific objective identification for fermentation | [13] |

Limitations and Future Directions

While FBA provides powerful capabilities for metabolic phenotype prediction, several limitations merit consideration. FBA does not inherently predict metabolite concentrations, as it operates at steady-state without incorporating kinetic parameters [10]. Additionally, basic FBA does not account for regulatory effects such as enzyme activation by protein kinases or regulation of gene expression, which can lead to discrepancies between predictions and experimental observations [10].

Future developments focus on addressing these limitations through several approaches:

Integration with Regulatory Networks: Methods like rFBA (regulatory FBA) incorporate Boolean rules based on gene expression to constrain reaction fluxes, improving prediction accuracy [12] [13].

Dynamic Extensions: dFBA (dynamic FBA) incorporates time-varying changes in extracellular metabolites, enabling simulation of batch cultures and dynamic processes [13].

Incorporation of Kinetic Constraints: New approaches integrate limited kinetic information with constraint-based modeling to enhance prediction accuracy while maintaining FBA's computational efficiency [13].

Multi-Scale Modeling: Integration of FBA with models of other cellular processes provides more comprehensive representations of cellular physiology [12] [13].

These advancing methodologies continue to expand FBA's applicability across biological research and biotechnology, solidifying its role as a core algorithm for predicting metabolic phenotypes in increasingly complex biological systems.

A foundational challenge in metabolic engineering is the development of microbial cell factories that efficiently produce high-value chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fuels. To address this challenge, bilevel optimization problems have emerged as a core computational framework for identifying optimal genetic intervention strategies [4]. These problems mathematically formalize the metabolic engineer's goal of maximizing the production of a target biochemical (the outer-level objective) while accounting for the fact that the engineered microbial strain will adjust its metabolism to optimize its own fitness, such as growth rate (the inner-level objective) [15]. This framework captures the inherent conflict between engineering objectives and cellular objectives, allowing for the systematic in silico prediction of genetic modifications—such as gene knockouts, knockdowns, or overexpressions—that force the cellular metabolism to overproduce the desired compound [4] [15].

The appeal of this approach lies in its ability to model the competitive yet interdependent relationship between the engineer and the cell. Solving these bilevel problems yields strategic reaction knockouts that create obligatory coupling between cell growth and product synthesis, making overproduction a necessary consequence of survival [15]. While classical methods transform these nested problems into single-level mixed-integer linear programs (MILPs), metaheuristics like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) offer a flexible alternative, particularly suited for handling complex, non-linear engineering objectives and large-scale metabolic networks [4].

Mathematical Formulation of the Bilevel Problem

Core Optimization Structure

The generic bilevel optimization problem for strain design can be formally expressed as a nested problem. The outer level maximizes an engineering objective, such as the production rate of a target biochemical ((v{chemical})), by manipulating a set of genetic interventions ((zj)). The inner level, conditioned on these interventions, models the cellular response by solving a metabolic network problem that typically maximizes biomass growth ((v_{biom})) [15].

In this formulation, (S{ij}) represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite (i) in reaction (j), and (vj) is the flux through reaction (j). The binary variables (z_j) indicate whether a reaction is active (1) or knocked out (0). The constant (K) limits the total number of allowed knockouts [15].

Inner-Level Objective Variants

The choice of inner-level objective function defines the model for cellular survival. The most common variants include:

- Biomass Maximization (OptKnock): The inner problem maximizes biomass yield, operating under the assumption that evolution has selected for maximal growth [15].

- Regulatory On/Off Minimization (ROOM): This model assumes that the mutant's metabolism undergoes minimal changes relative to the wild-type flux distribution. The inner problem minimizes the number of significant flux changes, which can be formulated using binary variables or quadratic penalties [15].

A Genetic Algorithm Framework for Bilevel Optimization

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) provide a powerful metaheuristic approach for solving the complex bilevel strain design problem. Their evolutionary principles of selection, crossover, and mutation are particularly advantageous when dealing with high-dimensional objective functions and non-linear constraints [4]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a GA applied to metabolic strain design.

Key Genetic Algorithm Parameters

The performance of a GA is highly sensitive to its parameter settings. Comprehensive parameter sensitivity analyses are required to prevent premature convergence to sub-optimal solutions [4]. The table below summarizes the core parameters and their roles.

Table 1: Key Parameters in a Genetic Algorithm for Strain Optimization

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Search Performance |

|---|---|---|

Population Size (N_P) |

Number of candidate solutions (individuals) in each generation. | A larger population increases diversity but also computational cost per generation [4]. |

| Number of Generations | Total number of evolutionary cycles. | More generations allow for greater refinement but with diminishing returns [4]. |

| Mutation Rate | Probability of randomly altering a binary target within an individual. | Prevents premature convergence and maintains genetic diversity [4]. |

| Crossover Rate | Probability that two parents will recombine to produce offspring. | Balances the exploration of new solutions with the exploitation of existing good ones [4]. |

Number of Targets per Individual (N_D) |

User-defined maximum number of reaction or gene deletions an individual can encode. | Defines the complexity of the knockout strategies being explored [4]. |

Binary Representation of Strain Designs

In a GA, a potential strain design (an "individual") is represented as a set of potential reaction or gene deletions. This set is encoded using a binary string of length N_B, calculated to sufficiently represent the entire target space of N_T reactions [4]. The number of bits is determined by:

N_B = Round( log(50 · N_T) / log(2) )

This ensures that each potential reaction knockout in the target space is assigned to at least 50 binary values, guaranteeing a near-uniform probability of selection and preventing bias towards a specific number of deletions per individual [4].

Advanced Considerations and Robust Formulations

Pessimistic Optimization for Robust Strain Design

A significant limitation of classical bilevel formulations like OptKnock and ROOM is their optimistic assumption that the mutant cell will always adopt a metabolic flux state that cooperates with the engineering objective [15]. In reality, the cell's response might be non-cooperative, and the model itself is an approximation. To address this, pessimistic optimization formulations (P-OptKnock and P-ROOM) have been developed. These frameworks aim to identify robust knockout strategies that maximize the desired biochemical production under the worst-case scenario of the inner-level model's uncertainty or non-cooperation [15]. These formulations can be transformed into single-level MIP problems using strong duality theory, making them tractable for large-scale models [15].

Integration of Multi-Scale Objectives

The flexibility of GAs allows for the integration of multiple, sophisticated engineering objectives beyond a single production yield, including:

- Handling Logical Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Associations: Allowing the algorithm to work directly with gene knockouts while accounting for complex enzymatic rules [4].

- Minimization of the Number of Network Perturbations: Incorporating a penalty for the number of knockouts to favor more practical, minimal genetic interventions [4].

- Insertion of Non-Native Reactions: Dynamically adding heterologous reactions from a candidate pool during the optimization process, inspired by frameworks like OptStrain [4].

Experimental Protocol: In Silico Strain Optimization with a Genetic Algorithm

This protocol details the steps for setting up and running a genetic algorithm to identify optimal reaction knockouts for biochemical overproduction using a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM).

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for In Silico Strain Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A stoichiometric matrix (S) of all metabolic reactions in the target organism. Serves as the in silico representation of cellular metabolism for FBA simulations [4] [15]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Solver | A linear programming (LP) solver (e.g., COBRA, Gurobi, CPLEX) used to compute the inner-level cellular objective (e.g., growth rate) for a given strain design [15]. |

| Genetic Algorithm Software Framework | A computational environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python) implementing the GA operators: selection, crossover, and mutation [4]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Problem Definition and Pre-processing: a. Define the Engineering Objective: Select the target exchange reaction for the biochemical of interest (e.g., succinate). The objective is to maximize its flux (

v_chemical). b. Define the Inner-Level Cellular Objective: Typically, this is the biomass reaction (v_biom). Alternative models like ROOM can be used. c. Define the Target Space (N_T): Select the set of reactions eligible for knockout (e.g., all non-essential cytoplasmic reactions). d. Set GA Parameters: Define population size (N_P), number of generations, mutation rate, crossover rate, and maximum number of knockouts per individual (N_D). Initial values can be based on sensitivity analyses from literature [4]. e. Calculate Binary Encoding Size (N_B): Use EquationN_B = Round( log(50 · N_T) / log(2) )to determine the bit string length for each individual [4].Initial Population Generation: a. Randomly generate

N_Pindividuals. Each individual is a binary matrix of sizeN_D x N_B. b. Each binary sequence in the matrix maps to a specific reaction in the target space. An individual thus represents a set ofN_Dpotential reaction knockouts.Fitness Evaluation: a. For each individual in the population, decode its binary sequence to identify the set of reaction knockouts. b. For this knockout set, solve the inner-level optimization problem (e.g., FBA with growth maximization) while constraining the flux of knocked-out reactions to zero. c. The fitness of the individual is the flux of the target biochemical (

v_chemical) obtained from the inner-level solution.Evolutionary Cycle (Repeat for each generation): a. Selection: Select parent individuals from the current population with a probability proportional to their fitness (e.g., using tournament or roulette wheel selection). b. Crossover: Pair parent individuals and, with a defined probability, perform crossover (e.g., single-point) to create offspring. c. Mutation: Apply point mutation to the offspring with a low probability, flipping bits to introduce new genetic material. d. Evaluate New Population: Assess the fitness of the new offspring population as in Step 3. e. Termination Check: Proceed to the next generation or terminate if the maximum number of generations is reached or convergence is achieved.

Post-processing and Validation: a. Output the Best Strategy: Identify the individual with the highest fitness score across all generations. b. In Silico Validation: Analyze the flux distribution of the final design. Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to check the robustness of the production profile. c. Experimental Implementation: The final list of predicted gene/reaction knockouts can be genetically implemented in the laboratory strain (e.g., E. coli or Y. lipolytica) for experimental validation [4] [16].

Connection to Emerging AI and Machine Learning Approaches

While GAs are a powerful heuristic, the field is rapidly evolving with new computational strategies. Reinforcement Learning (RL), particularly Multi-Agent RL (MARL), presents a model-free alternative that learns optimal policies for tuning enzyme levels directly from experimental data, without requiring a pre-defined metabolic model [7] [17]. Furthermore, active machine learning workflows like METIS can dramatically reduce experimental burden by interactively suggesting the most informative next experiments based on previous results, effectively optimizing complex biological systems with minimal trials [18]. These approaches are increasingly integrated into the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, automating the design and learning phases to accelerate strain development [7] [17].

Why Genetic Algorithms? Advantages Over Traditional Optimization Methods for Complex Networks

In the field of metabolic strain design, researchers are consistently challenged with optimizing complex biological systems to enhance the production of valuable compounds. Traditional optimization methods often fall short when dealing with the high-dimensional, non-linear, and multi-modal landscapes of metabolic networks. Genetic Algorithms (GAs), inspired by the principles of natural selection and evolutionary biology, offer a powerful alternative for navigating these complex search spaces [19]. Unlike traditional methods that often rely on deterministic rules and gradient information, GAs use a population-based, stochastic approach to evolve increasingly optimal solutions over successive generations [20]. This application note details the advantages of GAs and provides a detailed protocol for their application in metabolic network optimization, with a specific focus on strain design for improved succinic acid production.

Comparative Analysis: Genetic Algorithms vs. Traditional Methods

Fundamental Differences in Approach

Genetic Algorithms belong to a class of heuristic search methods that mimic natural evolution, maintaining a population of potential solutions which undergo selection, crossover, and mutation to produce improved offspring over generations [21] [22]. This approach contrasts sharply with traditional optimization methods, which typically operate on a single solution and use deterministic rules to traverse the solution space.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Algorithm Characteristics

| Feature | Genetic Algorithms | Gradient Descent | Simulated Annealing | Particle Swarm Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Population-based, Stochastic [20] | Single-solution, Deterministic [20] | Single-solution, Stochastic [20] | Population-based, Stochastic [20] |

| Uses Derivatives | No [20] | Yes [20] | No [20] | No [20] |

| Handles Local Minima | Yes [20] | No [20] | Yes [20] | Yes [20] |

| Suitable Problem Types | Complex, rugged, non-differentiable, or noisy search spaces [19] [20] | Smooth, convex, differentiable functions [20] | Problems with many local optima [20] | Continuous optimization [20] |

| Parallelizability | Highly [20] | Somewhat [20] | Somewhat [20] | Highly [20] |

Key Advantages for Metabolic Network Optimization

- Handling of Non-Linear and Discontinuous Functions: Metabolic networks are characterized by complex, non-linear interactions and regulatory constraints. GAs do not require the objective function to be differentiable or continuous, making them suitable for optimizing models that incorporate non-smooth functions or logical constraints (e.g., Boolean rules in Gene Regulatory Networks) [19] [23].

- Robustness in Multi-Modal Landscapes: Metabolic engineering problems often possess numerous local optima. The population-based nature of GAs, combined with mutation operators, allows them to explore diverse regions of the search space simultaneously, reducing the probability of becoming trapped in suboptimal solutions [20] [24].

- Integration of Complex Constraints: GAs can readily handle various types of constraints, such as those derived from genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), regulatory networks, and empirical biological knowledge. This facilitates the design of feasible and viable microbial strains [16] [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for a Model Problem

| Algorithm | Solution Quality (Fitness) | Convergence Speed (Generations) | Success Rate (%) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm | Global or Near-Global Optimum [24] | Moderate to High (100-1000) [22] | High (>90%) [25] | High [24] |

| Gradient Descent | Local Optimum [20] | Fast (<100) [20] | Low on rugged landscapes (<50%) | Low [20] |

| Simulated Annealing | Good to Near-Global Optimum [20] | Moderate (500-5000) [20] | Moderate (70-80%) | Moderate [20] |

Application Protocol: GA for Succinic Acid Production inYarrowia lipolytica

This protocol outlines the use of a Genetic Algorithm to identify optimal gene knockout and overexpression targets for enhancing succinic acid (SA) production in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, based on a Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) [16].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the genetic algorithm for metabolic strain optimization.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Problem Formulation and GEM Reconstruction

- Objective: Maximize the in silico predicted flux toward succinic acid production while maintaining a minimum growth rate.

- GEM Reconstruction: Reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic model for your target organism. For Y. lipolytica W29, this resulted in model iWT634, comprising 634 genes, 1130 metabolites, and 1364 reactions [16].

- Solution Encoding (Chromosome): Encode a potential solution as a chromosome where each gene represents a potential metabolic intervention.

- Example: A chromosome could be a binary vector indicating the knockout (0) or non-knockout (1) of specific genes, or an integer vector suggesting overexpression levels.

Step 2: Initialize the Genetic Algorithm Population

- Generate an initial population of N random chromosomes (e.g., N=100-500). Each chromosome represents a unique strain design strategy.

Step 3: Define the Fitness Function

- The fitness function quantitatively evaluates each chromosome. A typical function for maximizing SA production is:

Fitness = w₁ * (SA_Production_Rate) + w₂ * (Growth_Rate)wherew₁andw₂are weighting coefficients that prioritize production versus growth, determined by the researcher [16]. The production and growth rates are simulated using the GEM and constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA).

Step 4: Selection for Reproduction

- Employ a selection operator (e.g., Tournament Selection) to choose parent chromosomes for breeding based on their fitness [21]. This ensures that fitter solutions have a higher probability of passing their genes to the next generation.

Step 5: Crossover (Recombination)

- Perform crossover on selected parent pairs to create offspring. A Single-Point or Two-Point Crossover can be used to exchange genetic material between two parents, generating new combinations of gene targets [21].

Step 6: Mutation

- Apply a Flip Bit or Swap Mutation operator with a low probability (e.g., 0.5-1%) to randomly alter genes in the offspring [21]. This introduces genetic diversity and helps explore new regions of the solution space.

Step 7: Evaluation and Replacement

- Evaluate the fitness of the new offspring population.

- Replace the old population with the new one, often using an Elitism strategy to carry the best few solutions from the previous generation forward unchanged, preserving top performers [21].

Step 8: Termination

- Repeat Steps 4-7 for a predefined number of generations (e.g., 100-1000) or until the fitness score converges (shows no significant improvement over multiple generations) [21] [22].

Step 9: Experimental Validation

- The highest-scoring chromosomes from the final generation indicate the optimal gene manipulation targets.

- Example Predictions: The algorithm might identify knockout targets like Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) and ACH, and overexpression targets in the TCA cycle and glyoxylate shunt [16].

- These targets are then genetically engineered into the host strain (e.g., Y. lipolytica), and succinic acid production is validated experimentally via fermentation and analytical methods like HPLC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for GEM-Guided Strain Design with GA

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A computational framework representing the organism's entire metabolic network; used for in silico flux simulations. | Y. lipolytica model iWT634 [16] |

| Genetic Algorithm Software Platform | The computational environment for implementing the GA workflow. | Python with DEAP library, MATLAB, or specialized tools like OptRAM [23] |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | A software suite for performing constraint-based modeling, including FBA, within MATLAB/GNU Octave. | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A mathematical algorithm used to simulate metabolic flux distributions and predict growth or production rates in the GEM. | Core algorithm within COBRA Toolbox [23] |

| Gene Knockout Tools | Molecular biology tools for targeted gene deletion in the host strain (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9). | CRISPR-Cas9 system for Y. lipolytica |

| Gene Overexpression Tools | Vectors and promoters for inserting and enhancing the expression of target genes. | Strong constitutive or inducible promoters for Y. lipolytica |

Genetic algorithms provide a robust and powerful framework for tackling the complex optimization challenges inherent in metabolic network engineering. Their ability to efficiently navigate high-dimensional, non-linear, and multi-modal solution spaces without requiring derivative information makes them particularly well-suited for identifying non-intuitive genetic engineering targets in strain design. When integrated with genome-scale metabolic models and experimental validation, GAs significantly accelerate the development of high-performance microbial cell factories for the production of bio-based chemicals.

The selection of a suitable microbial host is a critical first step in the design of efficient cell factories for bioproduction. Among the plethora of available microorganisms, Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Bacillus subtilis have emerged as the foundational chassis organisms in metabolic engineering due to their distinct metabolic capabilities, genetic tractability, and industrial relevance. These organisms represent a spectrum of biological complexity from prokaryotic to eukaryotic systems, each offering unique advantages for specific production pipelines. E. coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, provides rapid growth and extensive genetic tools; S. cerevisiae, a eukaryotic yeast, offers eukaryotic protein processing and robustness in industrial fermentations; and B. subtilis, a Gram-positive bacterium, presents a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status and exceptional protein secretion capability. The strategic implementation of these organisms, guided by computational frameworks like genetic algorithm optimization, enables the systematic development of strains tailored for the production of high-value compounds, from therapeutic proteins to platform chemicals. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging these model organisms within a comprehensive metabolic strain design strategy.

Comparative Analysis of Model Organisms

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Model Organisms in Metabolic Engineering

| Feature | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Bacillus subtilis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organism Type | Gram-negative bacterium | Unicellular fungus (Yeast) | Gram-positive bacterium |

| Genetic Tools | Extensive (CRISPR/Cas9, plasmids) [26] [27] | Well-developed [28] | Available [29] |

| Growth Rate | High | Moderate | High |

| Industrial Status | Workhorse for recombinant proteins & metabolites [30] | Industrial fermentation for therapeutics & biofuels [28] [31] | GRAS status; used for enzymes & antimicrobials [29] |

| Typical Product Titer | Hypoxanthine: 30.6 g/L [26] [27] | Recombinant Protein: >1.53 g/L [28] | p-Coumaric Acid: 128.4 mg/L [29] |

| Metabolic Engineering Strategy | Blocking decomposition pathways, dynamic regulation [26] [27] | Plasma agitation to modulate metabolism [31] | Heterologous pathway expression & promoter engineering [29] |

| Computational Guidance | Genome-scale models for gene knockout prediction [32] | Multivariate Bayesian approach for process optimization [28] | Genome-scale models for analyzing metabolic differentiation [33] |

Application Notes & Case Studies

Escherichia coli: High-Yield Production of Hypoxanthine

Background: Hypoxanthine is a key precursor for nucleoside antiviral drugs and immunosuppressants. Traditional production methods face challenges like high costs and environmental impact. Metabolic engineering of E. coli offers a sustainable alternative [26] [27].

Objective: To develop a plasmid-free, high-yield E. coli strain for hypoxanthine production using a dual synergistic pathway.

Key Engineering Strategies & Outcomes: Table 2: Key Engineering Strategies for E. coli Hypoxanthine Production

| Strategy | Rationale | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Decomposition | Prevent product loss | Knockout of xdhABC genes [26] [27]. |

| Alleviating Feedback Inhibition | Overcome regulatory bottlenecks | Introduce mutant purF and prs genes from B. subtilis [26] [27]. |

| Dual Pathway Engineering | Enhance metabolic flux; avoid auxotrophy | Overexpression of adenosine deaminase (add) and adenine deaminase (ade) [26] [27]. |

| Precursor Supply | Boost substrate availability | Introduce mutant glnA gene and overexpress aspC for glutamine and aspartate supply [26] [27]. |

| Dynamic Regulation | Optimize branch pathway flux | Use a quorum-sensing system to dynamically regulate the guaB gene [26] [27]. |

Results: The engineered strain, when fermented in a 5 L bioreactor for 48 hours, achieved a hypoxanthine titer of 30.6 g/L, with a maximum real-time productivity of 1.4 g/L/h—the highest yield reported for microbial hypoxanthine fermentation [26] [27].

Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Optimized Fermentation for Therapeutic Proteins

Background: S. cerevisiae is a preferred host for producing therapeutic recombinant proteins. Maximizing titer and ensuring quality are critical for industrial application [28].

Objective: To optimize a S. cerevisiae fermentation process using a multivariate Bayesian approach to define a robust design space.

Key Engineering Strategies & Outcomes: A risk assessment was first conducted to identify Critical Process Parameters (CPPs), such as temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen. A Design of Experiments (DoE) study was then executed to model the response surface of critical quality attributes and titers. Finally, a multivariate Bayesian predictive approach was employed to identify the operational region where all attributes met specifications simultaneously [28].

Results: This systematic optimization led to broth titers exceeding 1.53 g/L. The model's prediction was verified by 12 consistency runs, confirming the reliability of the defined process design space [28].

Bacillus subtilis: Engineered Synthesis of p-Coumaric Acid

Background: p-Coumaric acid (p-CA) is a valuable phenolic acid with pharmacological properties. B. subtilis, with its GRAS status, is an ideal host for producing compounds for food and medical applications [29].

Objective: To heterologously express a tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) in B. subtilis for de novo p-CA production and optimize yield via promoter engineering.

Key Engineering Strategies & Outcomes:

The TAL gene from Saccharothrix espanaensis was codon-optimized and introduced into B. subtilis WB600. A series of constitutive and dual promoters were screened to maximize TAL expression. The highest p-CA production was achieved using the nprE promoter. Subsequent fermentation optimization, informed by Plackett-Burman (PB) and Box-Behnken (BBD) experimental designs, identified key medium components [29].

Results: The final engineered strain PBnprE produced 128.4 mg/L of p-CA. The fermentation broth extract demonstrated significant antibacterial and antioxidant activities, showcasing the biotechnological potential of the engineered strain [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fermentation of High-Yield E. coli for Hypoxanthine

This protocol details the fed-batch fermentation process for producing hypoxanthine using the engineered E. coli strain HX5 (or its derivatives) [26] [27].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| E. coli HX5 Strain | Engineered hypoxanthine production chassis [26] [27]. |

| Fermentation Medium | Contains glucose, citric acid, salts, yeast extract, and vitamins; supports high-density growth [26] [27]. |

| 25% (v/v) Ammonium Hydroxide | Used for automatic pH control during fermentation [26] [27]. |

| LB Medium | Used for seed culture activation [26] [27]. |

II. Procedure

- Seed Culture Preparation: Inoculate 10 µL of bacterial glycerol stock into a tube containing LB medium. Incubate at 37°C with shaking at 225 rpm for 15 hours.

- Bioreactor Setup: Prepare a 5 L bioreactor with 2 L of fermentation medium (omitting phenol red).

- Inoculation and Initial Cultivation: Transfer the seed culture to the bioreactor. Cultivate until the OD₆₀₀ reaches approximately 20.

- Fed-Batch Operation: Retain 400 mL of the culture and use a peristaltic pump to add fresh fermentation medium, restoring the volume to 2 L.

- Process Control:

- Maintain temperature at 37°C.

- Control pH at approximately 6.7 via the automatic addition of 25% ammonium hydroxide.

- Adjust the stirring speed and aeration rate to maintain dissolved oxygen above 50%.

- Monitoring and Harvest: Sample the broth every two hours to monitor glucose levels. Continue fermentation for 48 hours. Harvest the broth for hypoxanthine quantification.

Protocol: Plasma Agitation for S. cerevisiae Phenotypic Enhancement

This protocol describes a method to induce phenotypic changes in S. cerevisiae using atmospheric-pressure plasma agitation to improve fermentation efficiency [31].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae Strain | The industrial yeast strain targeted for improvement. |

| kINPen Plasma Jet | Source of non-thermal atmospheric-pressure plasma [31]. |

| Starter Culture Media | Standard rich (YPD) or defined minimal media for yeast growth. |

| Fermentation Culture Media | Media designed for ethanol or recombinant protein production. |

II. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Grow S. cerevisiae on solid agar plates to form isolated colonies.

- Plasma Treatment:

- Expose yeast colonies to the atmospheric-pressure plasma jet.

- For a stimulatory effect (non-lethal), apply treatment for 3 to 10 minutes. A 20-minute treatment is typically lethal [31].

- Maintain a defined distance (e.g., several millimeters) between the plasma nozzle and the colonies.

- Recovery and Expansion: Transfer the entire treated colony to a flask containing starter culture media. Incubate with shaking to allow cell recovery and expansion.

- Fermentation and Analysis: Use the expanded culture to inoculate the main fermentation culture. Analyze the resulting metabolites and enzyme activity (e.g., hexokinase) and compare with untreated controls [31].

Computational & Visualization Tools

Workflow Diagram for Strain Design

The following diagram illustrates a generic DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycle for metabolic strain design, integrating computational and experimental approaches.

Central Metabolism and Engineering Targets

This diagram provides a simplified view of central metabolic pathways in model organisms, highlighting key engineering targets mentioned in the case studies.

Implementing Genetic Algorithms for Strain Design: A Step-by-Step Framework

In the field of metabolic strain design, a core challenge is computationally identifying optimal genetic interventions to maximize the production of target metabolites. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) have emerged as a powerful metaheuristic for solving this complex, NP-hard optimization problem [4] [34]. The performance of a GA is heavily dependent on its encoding scheme—the method by which potential solutions (sets of gene or reaction knockouts) are represented as data structures within the algorithm [34]. This application note details the implementation, efficacy, and practical protocols for binary encoding strategies used to represent gene and reaction knockouts in GAs for metabolic engineering. We frame this within the broader context of optimizing microbial cell factories for the production of valuable chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and fuels [4] [12].

Theoretical Foundation of Binary Encoding

Definition and Structure

Binary encoding represents a solution—a set of proposed gene or reaction knockouts—as a one-dimensional array of bits (0s and 1s) [34]. Each bit in the array corresponds to a specific gene or reaction within the predefined target space of the metabolic network.

- Value of 1: Indicates that the corresponding gene or reaction is selected for knockout [34].

- Value of 0: Indicates that the corresponding gene or reaction remains unperturbed.

The length of the binary array (NB) is determined by the total number of potential targets (NT) in the network. To ensure a uniform probability of selection for each target and avoid bias towards a smaller number of knockouts, the number of bits is calculated to provide at least 50 unique binary representations per target [4]. The formula for calculating the number of bits per binary number is:

NB = Round( log(50 · NT) / log(2) ) [4]

This representation guarantees a user-defined, fixed number of potential knockouts (ND) per individual solution, where each "individual" is a binary string of length NB × ND [4].

Comparison with Integer Encoding

Binary encoding stands in contrast to integer encoding, another common strategy. The table below summarizes the key differences in the context of representing knockout strategies.

Table 1: Binary vs. Integer Encoding for Knockout Strategies

| Feature | Binary Encoding | Integer Encoding |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Representation | Array of 0s and 1s; length = number of potential targets [34]. | Array of integers; length = number of knockouts (k) [34]. |

| Meaning of Elements | Element index = target ID; value (1/0) = selected/not selected [34]. | Element value = the ID of the selected target [34]. |

| Solution Space | Represents all possible combinations of selected/non-selected from NT targets. |

Represents all possible combinations of k targets from NT. |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive mapping to knockout/no-knockout decisions. | Inherently prevents invalid solutions with too many knockouts. |

Binary Encoding in Metabolic Strain Design

Integration with Genetic Algorithms

In a typical GA workflow for metabolic engineering, a population of binary-encoded individuals evolves over generations [4]. The fitness of each individual is evaluated by applying the corresponding knockouts to a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) and simulating metabolism using methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict the production yield of the target compound [4] [12]. Genetic operators—selection, crossover, and mutation—are then applied to create new, potentially better-performing knockout strategies.

Performance and Optimized Operator Selection

The choice of genetic operators significantly impacts the performance of binary-encoded GAs. Experimental comparisons on benchmark problems show that the combination of uniform crossover with a random repair operator is particularly effective for binary encoding [34]. This combination has been shown to improve the average objective value by up to 3.24% compared to other operator combinations like one-point crossover with random repair [34]. Uniform crossover allows for a more thorough exploration of the solution space by deciding independently for each gene whether to swap its value between two parent solutions, which is well-suited to the structure of binary encoding [34].

Figure 1: Workflow of a genetic algorithm using binary encoding for metabolic strain design. The process involves creating a population of random binary strings, evaluating their fitness via metabolic modeling, and iteratively improving them through genetic operations.

Advanced Integrated Frameworks

While binary encoding in GAs is powerful, its solutions can be further refined by integrating regulatory information. The Reliability-Based Integrating (RBI) algorithm is a novel approach that enhances knockout strategies by incorporating Boolean rules from empirical Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) and Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations [12].

This algorithm uses reliability theory to model the probabilities of gene states and reaction fluxes, comprehensively accounting for the types of interactions (activation/inhibition) between transcription factors and their target genes [12]. When a GA proposes a set of knockouts via binary encoding, the RBI algorithm can validate or refine this set by checking its consistency with the broader regulatory network, leading to more robust and physiologically feasible strain designs [12]. This hybrid approach demonstrates strong performance in designing E. coli and S. cerevisiae mutants for enhanced succinate and ethanol production [12].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Binary-Encoded GA

Protocol: GA-Based Identification of Knockout Strategies

Objective: To identify a set of gene knockouts that maximize the production of a target metabolite using a binary-encoded genetic algorithm.

Materials:

- Metabolic Model: A genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., for E. coli or S. cerevisiae) [4] [12].

- Software Environment: A computational environment capable of running constraint-based modeling (e.g., Python with COBRApy, Matlab) [4].

- GA Implementation: Custom code or optimization toolbox that supports binary encoding.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) | In silico representation of the organism's metabolism for simulating knockout effects [4] [12]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Constraint-based modeling technique to predict metabolic flux distributions and growth/production yields [4] [12]. |

| Binary-Encoded GA Framework | Metaheuristic search algorithm to evolve optimal knockout strategies [4] [34]. |

| Uniform Crossover Operator | Genetic operator that mixes parent solutions at the bit-level to create offspring [34]. |

| Random Repair Operator | Operator that corrects invalid offspring (e.g., wrong number of knockouts) in binary encoding by randomly flipping bits [34]. |

Procedure:

Preprocessing:

- Define the target space (

NT). This is the list of all gene-associated reactions considered candidate knockouts. - Define the number of knockouts per individual (

ND) and calculate the required bit length (NB) using Equation 1 [4]. - Map each possible target to a range of binary number permutations.

- Define the target space (

Initialization:

- Generate an initial population of

NPindividuals. Each individual is a binary string of lengthNB×ND, initialized randomly [4].

- Generate an initial population of

Fitness Evaluation:

- For each individual in the population:

- Decode the binary string to identify the set of genes/reactions to knockout.

- Apply these knockouts to the GSMM by constraining the corresponding reaction fluxes to zero.

- Perform FBA with the objective to maximize the target metabolite production rate.

- The production rate (or a function of it) is assigned as the individual's fitness score [4].

- For each individual in the population:

Genetic Operations:

- Selection: Select parent individuals from the population with a probability proportional to their fitness.

- Crossover: Apply uniform crossover to pairs of parents to generate offspring. For each bit position, randomly choose from which parent the bit is inherited [34].

- Mutation: Apply point mutation by flipping each bit in the offspring with a low probability (e.g., 0.01-0.05).

- Repair: Apply a random repair operator to ensure the feasibility of the offspring. If the number of '1's (knockouts) is incorrect, randomly flip bits until the constraint is satisfied [34].

Termination:

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 for a predetermined number of generations or until convergence is observed.

- Select the individual with the highest fitness score from the final generation as the optimal knockout strategy.

Figure 2: Visual comparison of how knockout strategies are represented in binary versus integer encoding. Binary encoding uses a bit array where the index corresponds to a gene ID, while integer encoding stores a list of the targeted gene IDs directly.

Binary encoding provides a straightforward and effective method for representing gene and reaction knockouts in genetic algorithm-driven metabolic engineering. Its performance is robust, especially when paired with optimized genetic operators like uniform crossover and random repair. The integration of binary-encoded GA solutions with advanced network modeling techniques, such as the RBI algorithm, paves the way for designing next-generation microbial cell factories with enhanced production capabilities for a wide array of biologically synthesized compounds.

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are metaheuristic optimization methods inspired by the principles of natural evolution and are particularly suited for solving complex, high-dimensional problems in metabolic engineering [4]. In the context of metabolic strain design, they facilitate the identification of optimal genetic interventions—such as gene knockouts, knockdowns, or the introduction of heterologous reactions—to maximize the production of target biochemicals [4] [35]. The core operators of a GA—selection, crossover, and mutation—work in concert to evolve a population of candidate solutions toward an optimal metabolic configuration. This document details the application of these core operators and provides standardized protocols for their implementation in metabolic engineering research.

Core Operator Mechanisms and Representations

Genetic Representation of Metabolic Networks

In metabolic strain design, an individual in the GA population typically represents a set of proposed genetic modifications. A common and effective representation uses a binary coding scheme [4].

- Individual Encoding: Each individual consists of a sequence of

NBbits, forming a binary number. Each unique value of this binary number is assigned to a specific reaction or gene within the target metabolic network that is a candidate for deletion or intervention [4]. - Target Space and Bit Calculation: The target space encompasses all

NTpossible reaction or gene targets in the network. To ensure a uniform probability of selecting any target and to avoid bias in the number of deletions, the number of bits per binary numberNBis calculated to be large enough to assign each target to at least 50 binary values. This is determined by the formula [4]:NB = Round( log(50 * NT) / log(2) ) - Fixed-Size Intervention Sets: The user defines the maximum number of targets (

ND) per individual. The actual number of network perturbations may be lower if multiple binary values point to the same gene or reaction [4].

The Role of Selection, Crossover, and Mutation

The iterative process of a GA involves applying three core operators to a population of individuals over multiple generations.

- Selection: This operator favors individuals with higher fitness—a quantitative measure of how well a candidate strain design achieves the engineering objective, such as the predicted yield of a target metabolite [4] [35]. Fitter individuals have a higher probability of being selected as parents for the next generation.

- Crossover (or Recombination): This operator combines genetic material from two parent individuals to create one or more offspring. It allows for the merging of beneficial genetic interventions from different solutions [4]. For graph-based representations, such as molecular structures, specialized cut-and-join crossover operators can be employed. These operators make small cuts in the graph representations of two parent molecules and rejoin the resulting subgraphs to create novel, yet chemically plausible, offspring molecules [36].

- Mutation: This operator introduces random changes into an individual's genetic code, for example, by flipping bits in the binary representation. It helps maintain population diversity and enables the exploration of new regions in the solution space, preventing premature convergence to sub-optimal solutions [4].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow of a genetic algorithm in metabolic engineering.

Quantitative Data and Performance

The performance of a GA is highly sensitive to its parameter settings. Comprehensive parameter sensitivity analyses are crucial for avoiding premature convergence and ensuring the algorithm finds optimal strain designs [4]. The table below summarizes key parameters and their impact, synthesized from research in the field.

Table 1: Key Genetic Algorithm Parameters and Performance Impact in Metabolic Engineering

| Parameter | Description | Quantitative Impact / Typical Consideration | Source Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Probability of altering a single bit in an individual. | Requires tuning; high rates can prevent convergence, low rates lead to premature convergence. | [4] |

| Population Size | Number of individuals (candidate solutions) in each generation. | Larger sizes improve exploration but increase computational cost per generation. | [4] |

| Number of Generations | Total number of evolutionary iterations. | Directly impacts convergence; must be balanced with population size. | [4] |

Number of Targets (ND) |

User-defined maximum number of genetic interventions per individual. | Fixed per individual; actual perturbations may be fewer due to encoding. | [4] |

| Prediction Validation | Comparison of GA-predicted outcomes with experimental results. | Close alignment observed; e.g., material property predictions within 1-5% of experimental values. | [37] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a GA for Predicting Gene Knockouts

This protocol outlines the steps for using a GA to identify gene knockout strategies for enhanced metabolite production [4] [35].

Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Define the target metabolite and the production objective (e.g., maximize yield).

- Host and Model: Select a host organism (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae) and a corresponding genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) or enzyme-constrained model (ecModel) like ecYeastGEM [35].

- Fitness Function: Define a function that simulates microbial phenotype (e.g., using Flux Balance Analysis - FBA) for a given knockout strategy and returns the production yield [4] [13].

GA Configuration:

- Representation: Use a binary representation as described in Section 2.1. Calculate

NBbased on the size of your target spaceNT. - Initialization: Randomly generate an initial population of

NPindividuals. - Parameter Setting: Set parameters such as mutation rate, crossover rate, population size, and number of generations based on preliminary sensitivity analysis.

- Representation: Use a binary representation as described in Section 2.1. Calculate

Evolutionary Loop:

- Evaluation: Calculate the fitness of each individual in the population by running the fitness function (e.g., FBA simulation) for the encoded knockout set.

- Selection: Apply a selection method (e.g., tournament selection) to choose parents.

- Crossover: Perform crossover on selected parent pairs to create offspring.

- Mutation: Apply the mutation operator to the offspring with a defined probability.

- Termination: Repeat the loop until a termination criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations or fitness plateau).

Output and Validation:

- The algorithm outputs the best-performing strain design(s).

- These predicted gene targets must be validated through experimental testing in the laboratory [35].