Geometric Programming vs. Linear Programming for Metabolic Optimization: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Geometric Programming (GP) and Linear Programming (LP) for optimizing metabolic systems in biomedical research and drug development.

Geometric Programming vs. Linear Programming for Metabolic Optimization: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Geometric Programming (GP) and Linear Programming (LP) for optimizing metabolic systems in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both optimization frameworks, detailing their specific methodologies and applications in modeling metabolic pathways, dynamic regulation, and strain design. The content addresses critical troubleshooting aspects and performance optimization for each method, culminating in a validated, comparative analysis of their efficiency, accuracy, and applicability to real-world biological problems. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes key insights to inform the selection and implementation of the most suitable optimization strategy for advanced metabolic engineering projects.

Core Principles: Unpacking the Mathematical Foundations of GP and LP in Biology

Linear Programming (LP) represents a cornerstone method in optimization, achieving the best outcome against a linear objective function within a constrained linear system [1]. Its application spans from logistics to metabolic engineering, where it provides a robust framework for flux balance analysis in biochemical networks [2]. However, biological systems often exhibit inherent nonlinearities that challenge LP's fundamental assumptions. This limitation has prompted the development of advanced optimization techniques, notably Geometric Programming (GP), which leverages the special structure of power-law models to efficiently solve nonconvex optimization problems prevalent in metabolic pathway engineering [3] [4]. While LP remains invaluable for stoichiometric models lacking regulatory details, GP has demonstrated superior performance in identifying global optima for nonlinear biochemical systems, achieving computational efficiency that positions it as a transformative methodology for complex metabolic optimization tasks [3] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Foundations

Linear Programming: Core Formulations

Linear programming optimizes a linear objective function subject to linear equality and inequality constraints, with the standard form expressed as [1]: [ \text{Maximize } \mathbf{c}^T\mathbf{x} \quad \text{subject to} \quad A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b} \ \text{and} \ \mathbf{x} \geq \mathbf{0} ] Here, ( \mathbf{x} ) represents the decision variables, ( \mathbf{c} ) contains coefficients for the linear objective function, and ( A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b} ) defines the system constraints [1]. The feasible region formed by these constraints constitutes a convex polytope, with optimal solutions invariably located at corner points of this region [1].

The simplex algorithm, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, efficiently navigates these corner points to locate optima, while interior-point methods developed later provide polynomial-time solutions [1]. LP's computational efficiency enables solution of large-scale problems—Dantzig's original example of assigning 70 people to 70 jobs would have required checking more configurations than particles in the observable universe through enumeration, yet the simplex method finds the optimum in moments [1].

Geometric Programming: Extending to Nonlinear Domains

Geometric programming addresses a class of nonlinear optimization problems that can be transformed into convex forms through logarithmic/variable transformations [4]. GP specializes in optimizing posynomials—functions comprising sums of power-law terms (monomials) with positive coefficients [3] [4].

The GP standard form appears as: [ \text{Minimize } f0(\mathbf{x}) \quad \text{subject to} \quad fi(\mathbf{x}) \leq 1, \quad hj(\mathbf{x}) = 1 ] where ( fi ) are posynomials and ( h_j ) are monomials [4]. This structure proves particularly adept at handling Generalized Mass Action (GMA) systems in biochemical modeling, where each power-law term constitutes a monomial [3] [4]. Through logarithmic transformation of variables and constraints, GP converts nonconvex problems into convex forms solvable with high efficiency—problems with 1000 variables and 10,000 constraints can be solved in under a minute on standard desktop computers [4].

Table 1: Core Mathematical Properties Comparison

| Property | Linear Programming (LP) | Geometric Programming (GP) |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | Linear: ( \mathbf{c}^T\mathbf{x} ) | Posynomial: ( \sumk ck x1^{a{1k}} \cdots xn^{a{nk}} ) |

| Constraints | Linear inequalities/equalities | Posynomial inequalities, monomial equalities |

| Feasible Region | Convex polytope | Convex after logarithmic transformation |

| Variable Domain | Typically ( \mathbf{x} \geq \mathbf{0} ) | ( \mathbf{x} > \mathbf{0} ) |

| Solution Space | Corner points of polytope | Interior and boundary points after transformation |

| Global Optimality | Guaranteed for convex feasible region | Guaranteed after convex transformation |

Applications in Metabolic Optimization: A Comparative Analysis

Linear Programming in Metabolic Engineering

LP has established fundamental utility in metabolic engineering through Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts metabolic fluxes by assuming steady-state operation and mass balance constraints [2]. The key advantage lies in LP's computational efficiency with minimal information requirements—primarily flux rates and physico-chemical constraints [3]. This enables genome-scale modeling without demanding kinetic parameters [2].

Recent extensions integrate transcriptomic data through methods like Linear Programming based Gene Expression Model (LPM-GEM), which linearly embeds gene expression into FBA constraints to improve flux predictions across different nutritional conditions [2]. When validated against 13C tracer experiments, such LP-based approaches successfully predict carbon source utilization in Bacillus subtilis, demonstrating practical utility despite simplification of biological complexity [2].

Geometric Programming for Nonlinear Biochemical Systems

GP addresses fundamental limitations in LP approaches by directly capturing the nonlinear regulatory features of metabolic pathways through GMA systems within Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) [3] [4]. Unlike S-system representations that approximate multiple fluxes into aggregated power-laws, GMA models represent each enzymatic process separately as power-law functions, preserving biological fidelity [4].

The significance of GP extends beyond specialized applications—GMA systems contain stoichiometric, mass-action, and S-system models as special cases, while algebraic equivalence transformations can convert virtually any dynamical model into GMA form [3]. This universality, combined with GP's computational efficiency, enables global optimization of complex metabolic networks that evade LP's linearity constraints [3] [4].

Table 2: Metabolic Optimization Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Linear Programming | Geometric Programming |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Efficiency | Highly efficient for large-scale problems [1] | Efficient for nonlinear problems; solves 1000 variables in <1 minute [4] |

| Regulatory Representation | Cannot represent regulation [3] | Explicitly captures nonlinear regulation [3] |

| Steady-State Solution | Linear equations [3] | Nonlinear, converted to linear via log transformation [4] |

| Global Optimality | Guaranteed for linear models [1] | Guaranteed after convex transformation [4] |

| Model Type Compatibility | Stoichiometric models [3] | GMA, S-system, mass action models [3] |

| Tryptophan Biosynthesis Solution | Suboptimal [4] | Global optimum identified (>3× basal flux) [4] |

| Implementation Examples | LPM-GEM for B. subtilis carbon source prediction [2] | Anaerobic fermentation in S. cerevisiae; E. coli tryptophan operon [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

LP Experimental Protocol: Gene Expression Integration

LPM-GEM Methodology [2]:

- Data Assembly: Collect microarray gene expression data and corresponding 13C metabolic flux data for validation

- Pre-processing: Map gene expression to proteins and reactions using Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations

- Model Construction:

- Transfer stoichiometric matrix, bounds, and reversibility from base metabolic model (e.g., iYO844 for B. subtilis)

- Implement three strategies to reduce thermodynamically infeasible loops

- Constraint Formulation: Embed continuous gene expression data linearly into FBA constraints

- Validation: Compare predicted fluxes against 13C tracer experimental data across multiple carbon source conditions

This protocol successfully predicted carbon sources for B. subtilis with accuracy outperforming established methods, demonstrating LP's practical utility despite its mathematical simplification of biological processes [2].

GP Experimental Protocol: Steady-State Optimization

Geometric Programming for GMA Systems [3] [4]:

- System Representation: Convert metabolic pathway to GMA formalism where each reaction rate ( vi ) follows power-law representation: [ vi = \gammai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{f{i,j}} ] where ( \gammai ) is the rate constant and ( f{i,j} ) are kinetic orders [3]

Steady-State Formulation: Apply steady-state conditions ( \frac{dXi}{dt} = \sum \mu{ij} v_j = 0 ), resulting in system of monomial and posynomial equations [4]

Equivalence Transformation: Convert nonconvex GMA equations to GP-compatible form through:

- Variable substitution (( yi = \ln Xi ))

- Monomial condensation for posynomial constraints [4]

Geometric Programming Implementation:

- Solve transformed convex optimization problem

- Iteratively refine solution through sequential GP approximations

- Validate stability through eigenvalue analysis [5]

Bi-objective Extension: For multi-objective optimization (e.g., maximize product yield while minimizing metabolite concentrations):

- Apply Normal-Boundary Intersection (NBI) method

- Transform to single-objective optimization

- Generate Pareto optimal fronts [5]

This protocol has demonstrated superior performance in benchmark studies, including anaerobic fermentation in S. cerevisiae and tryptophan biosynthesis in E. coli, consistently identifying global optima that eluded previous optimization methods [3] [4].

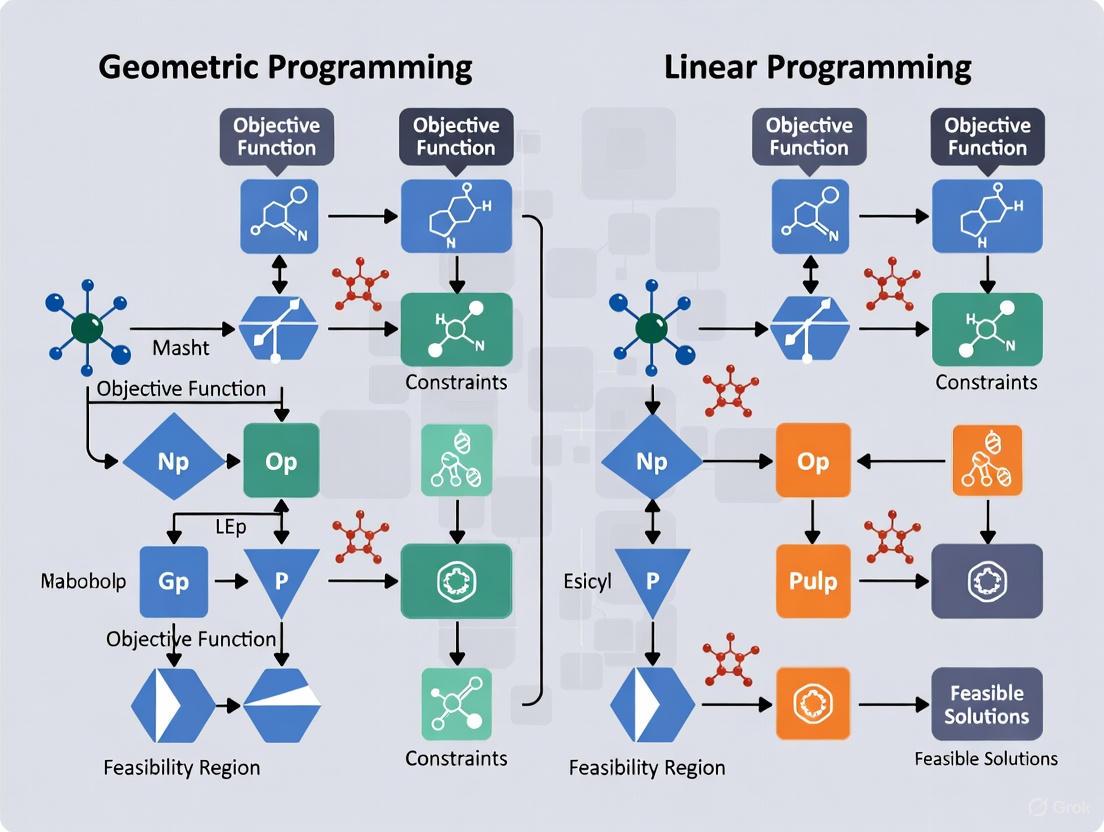

Figure 1: Comparative Methodological Workflows for LP and GP in Metabolic Optimization

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Metabolic Optimization Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| GGPLAB | MATLAB-based GP solver for biochemical systems [4] | Geometric Programming |

| Gurobi Optimizer | Commercial solver for LP and related problems [6] | Linear Programming |

| BiGG Models Database | Curated metabolic models (e.g., iYO844 for B. subtilis) [2] | Both LP and GP approaches |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Mapping | Links gene expression to metabolic reactions [2] | Both LP and GP approaches |

| 13C Tracer Flux Data | Gold standard validation for predicted metabolic fluxes [2] | Both LP and GP approaches |

| Normal-Boundary Intersection (NBI) | Method for multi-objective optimization [5] | Primarily GP |

| BST-Based Modeling Tools | Biochemical Systems Theory implementation for GMA models [3] | Geometric Programming |

Critical Analysis and Research Outlook

The comparative analysis reveals a complementary relationship between LP and GP in metabolic optimization. LP maintains advantages in computational efficiency and implementation simplicity for large-scale stoichiometric models, particularly when integrated with transcriptomic data through methods like LPM-GEM [2]. However, GP demonstrates unequivocal superiority for problems requiring accurate representation of nonlinear regulatory dynamics, achieving global optima that escape LP-based methods [3] [4].

Recent advances address GP's historical limitations through improved handling of nonconvex problems via equivalence transformation and monomial compensation strategies [4]. For S-type biochemical systems, GP successfully solves nonconvex bi-objective optimization problems with stability guarantees, generating Pareto optimal solutions that balance product yield maximization with metabolite concentration minimization [5].

Future research trajectories include hybrid approaches leveraging LP's scalability for initial screening and GP's precision for refined optimization of promising metabolic engineering targets. The integration of thermodynamic constraints with geometric programming represents another fruitful direction, potentially bridging the gap between thermodynamic feasibility and regulatory complexity in metabolic models [2].

For researchers selecting between these methodologies, the decision framework should prioritize LP when working with genome-scale stoichiometric models lacking detailed kinetic information, and GP when optimizing well-characterized pathways with known regulatory interactions and nonlinear dynamics. As kinetic modeling advances through improved parameter estimation, GP's strategic importance in metabolic engineering will likely expand, establishing it as the methodology of choice for precision optimization of complex biochemical systems.

Geometric Programming (GP) represents a powerful class of constrained nonlinear optimization problems that has found significant application in metabolic engineering and systems biology. Unlike generic nonlinear optimization, GP possesses unique mathematical properties that enable efficient solution of otherwise computationally challenging problems. When applied to metabolic optimization, GP allows researchers to manipulate metabolic networks to improve desired characteristics of biochemical systems, such as maximizing product yield or redirecting metabolic flux toward valuable compounds [7].

The fundamental advantage of GP in biological contexts stems from its ability to model the highly nonlinear nature of biochemical processes while maintaining computational tractability. This is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering tasks where the goal is to identify optimal genetic manipulations or process conditions that maximize the production of target metabolites while maintaining cellular viability and function [7] [4]. The comparison between GP and linear programming (LP) approaches is especially relevant because many traditional metabolic optimization methods rely on linear approximations of biological systems, which may fail to capture essential nonlinear dynamics.

Mathematical Foundations of Geometric Programming

Core Components: Monomials and Posynomials

The mathematical structure of GP is built upon two special types of functions: monomials and posynomials. Understanding these components is essential for formulating problems within the GP framework.

A monomial is defined as a function of the form:

[f(x) = c x1^{a1} x2^{a2} ... xn^{an}]

where:

- (c) is a positive constant

- (x_{1..n}) are positive decision variables

- (a_{1..n}) are real exponents [8]

Examples of monomials include (7x), (4xy^2z), and (\frac{2x}{y^2z^{0.3}}) [8]. In the context of biochemical systems, monomials naturally represent kinetic rate laws, enzyme-catalyzed reactions, and other fundamental biological processes [7].

A posynomial extends this concept as a sum of monomials:

[g(x) = \sum{k=1}^K ck x1^{a1k} x2^{a2k} ... xn^{ank}]

Examples of posynomials include expressions like (x^2 + 2xy + 1) and (7xy + 0.4(yz)^{-1/3}) [8]. In metabolic modeling, posynomials can represent aggregated biological processes, such as the combined activity of multiple enzymatic pathways or the total flux through branched metabolic networks [7].

The Convex Transformation

The remarkable property of GP that distinguishes it from general nonlinear optimization is its transformability to a convex optimization problem. This transformation occurs through a logarithmic change of variables that converts the inherently nonconvex GP into a convex form, guaranteeing that any local optimum is also globally optimal [8].

The transformation process works as follows:

- Original variables (xi > 0) are replaced with their logarithms: (yi = \log x_i)

- Monomials become linear functions in the new variables: (c \prod xi^{ai} = c \exp(\sum ai yi))

- Posynomials become log-sum-exp functions, which are convex [9]

This convex transformation enables GP problems to be solved "extremely quickly" and "with no initial guesses or tuning of solver parameters" [8]. For perspective, "a GP with 1000 variables and 10,000 constraints can be solved in under a minute on a desktop computer" [4].

The following diagram illustrates this convex transformation process:

GP vs. LP: Methodological Comparison for Metabolic Optimization

Fundamental Differences in Problem Formulation

While both Geometric Programming and Linear Programming are used for metabolic optimization, they differ fundamentally in their mathematical structure and biological representation.

Linear Programming (LP) in Metabolism:

- Represents metabolic networks using stoichiometric matrices [10]

- Assumes steady-state operation with constant metabolite concentrations [10]

- Optimizes flux distributions through linear constraints [11]

- Cannot directly represent regulatory features or nonlinear kinetics [7]

Geometric Programming (GP) in Metabolism:

- Represents metabolic processes using power-law functions within Generalized Mass Action (GMA) systems [7] [4]

- Can capture nonlinear enzyme kinetics and regulatory interactions [7]

- Maintains mathematical tractability through convex transformation [8]

- Allows optimization of both metabolic fluxes and enzyme activities [4]

The key advantage of GP lies in its ability to model the inherent nonlinearity of biological systems while maintaining computational efficiency. As one study notes, "GMA systems are of importance because they contain stoichiometric, mass action and S-systems as special cases" [7], making them a more comprehensive framework for biological optimization.

Application to Metabolic Network Optimization

The practical differences between GP and LP approaches become evident when applied to specific metabolic optimization tasks. The following table summarizes their comparative performance based on experimental studies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of GP vs. LP in Metabolic Optimization

| Aspect | Geometric Programming (GP) | Linear Programming (LP) |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Power-law functions in GMA systems [7] | Linear stoichiometric models [10] |

| Regulatory Representation | Can directly represent enzyme regulation and inhibition [7] | Cannot capture regulatory features [7] |

| Solution Efficiency | Solves nonconvex problems through convex transformation [4] | Efficient for linear problems but limited in nonlinear contexts [11] |

| Optimality Guarantee | Global optimum guaranteed for transformed problem [8] | Global optimum for linear formulation only [11] |

| Implementation Example | Optimization of anaerobic fermentation in S. cerevisiae [7] | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) in E. coli models [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol for GP-Based Metabolic Optimization

Implementing geometric programming for metabolic optimization involves a systematic procedure that leverages the special structure of GMA systems:

Model Formulation: Represent the metabolic network as a GMA system where each reaction rate follows power-law formalism: [vi = \gammai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{f{i,j}}] where (\gammai) is the rate constant, (Xj) are metabolic concentrations, and (f{i,j}) are kinetic orders [7].

Steady-State Establishment: Define the steady-state constraints using the stoichiometric matrix (N) and flux vector (v): [\frac{dX}{dt} = N \cdot v = 0] which ensures mass balance within the metabolic network [7].

Objective Function Specification: Formulate the optimization target (e.g., product yield maximization) as a posynomial function of the system variables [4].

Constraint Definition: Include additional posynomial constraints representing physical, metabolic, and physiological limitations [7].

Convex Transformation: Apply logarithmic transformation to convert the GP to a convex optimization problem [8].

Solution Implementation: Solve the transformed problem using GP solvers such as GGPLAB [4] or CVXPY with DGP capabilities [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental protocol:

Case Study: Tryptophan Biosynthesis Optimization

A comparative study optimizing tryptophan biosynthesis in E. coli demonstrated the advantages of GP over alternative methods. The GP approach successfully identified the global optimal solution that maximized tryptophan flux, achieving more than 3 times the basal flux [4]. This performance exceeded that of controlled error and penalty treatment methods, which failed to reach the global optimum in the same problem [4].

The successful application of GP to this system highlights its practical value for metabolic engineering, where identifying true optimal solutions can significantly impact production yields in industrial biotechnology.

Case Study: Anaerobic Fermentation Pathway Optimization

Another benchmark study applied GP to optimize the anaerobic fermentation pathway in S. cerevisiae [7]. The GP formulation efficiently handled the nonlinear kinetics of the fermentation pathway and identified optimal manipulation strategies for yield improvement. The method demonstrated equal or better performance compared to earlier optimization approaches "in terms of successful identification of optima and efficiency" [7].

Implementing geometric programming for metabolic optimization requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table outlines key components of the research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GP-Based Metabolic Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in GP Metabolic Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| GMA Models | Mathematical Framework | Represents metabolic networks with power-law functions for GP compatibility [7] |

| CVXPY with DGP | Software Library | Python-embedded modeling language for disciplined geometric programming [9] |

| GGPLAB | GP Solver | MATLAB-based solver for geometric programming problems [4] |

| S-system Models | Special Case | Simplified BST representation convertible to GP form [7] |

| Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) | Theoretical Framework | Provides foundation for power-law modeling of biological systems [7] |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Complementary Method | Provides constraint information for GP metabolic models [10] |

Geometric Programming provides a mathematically rigorous and computationally efficient framework for metabolic optimization that surpasses linear programming approaches in handling biological nonlinearity. Through its foundation in monomial and posynomial functions and the powerful convex transformation, GP enables researchers to identify globally optimal solutions to complex metabolic engineering problems.

The experimental evidence from case studies on tryptophan biosynthesis and anaerobic fermentation pathways demonstrates that GP consistently outperforms traditional optimization methods, including LP-based approaches, in both solution quality and computational efficiency. As metabolic engineering continues to address increasingly complex biological systems, Geometric Programming offers a versatile and powerful approach for unlocking the full potential of cellular metabolism for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Metabolic network modeling represents a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling the prediction of cellular behavior and the identification of strategic interventions for biotechnological and therapeutic applications. The core challenge lies in selecting and executing the appropriate computational strategy to manipulate these complex biochemical systems effectively. Optimization techniques provide the mathematical foundation for navigating these high-dimensional spaces, with linear programming (LP) and geometric programming (GP) emerging as two powerful, yet philosophically and technically distinct, paradigms. While LP has long been a staple in constraint-based modeling due to its simplicity and reliability, GP offers a sophisticated framework for tackling the inherent nonlinearities of metabolic kinetics. This guide provides a structured comparison of these two approaches, detailing their theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and performance characteristics to inform their use in metabolic engineering and drug development research.

Theoretical Foundations: A Tale of Two Frameworks

The distinction between Linear Programming and Geometric Programming begins at the most fundamental level of mathematical representation and problem formulation.

Linear Programming (LP) in Metabolism: LP is applied to metabolic networks whose steady-state behavior can be described using systems of linear equations. This is most commonly achieved through Stoichiometric Models, such as those used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), where the mass-balance constraint at steady state (

Nv = 0) creates a linear system [3] [12]. A key innovation was the application of Biochemical Systems Theory (BST), which allows nonlinear kinetic models to be recast into a simplified power-law representation known as an S-system. When expressed in logarithmic coordinates, the steady-state equations of an S-system become linear, enabling the use of efficient LP algorithms for optimization [3] [13]. The objective function and all constraints in an LP problem are linear combinations of the decision variables.Geometric Programming (GP) in Metabolism: GP, in contrast, is a specialized nonlinear optimization technique that is exceptionally well-suited for models whose dynamics are inherently nonlinear. It is the natural framework for optimizing General Mass Action (GMA) systems within BST [3]. A GMA system represents each reaction rate as a monomial (a single power-law term), and the system dynamics are described by a sum of such monomials. The standard form of a GP requires the objective function and constraints to be posynomials (sums of monomials with positive coefficients) [3]. After a logarithmic transformation of variables, a GP can be converted into a convex optimization problem, guaranteeing the discovery of a global optimum.

Table 1: Core Mathematical Characteristics of LP and GP

| Feature | Linear Programming (LP) | Geometric Programming (GP) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Model | S-system (BST), Stoichiometric Model | GMA System (BST), Mass Action |

| Problem Formulation | Linear objective & constraints | Posynomial objective & constraints |

| Variable Transformation | Often uses logarithmic coordinates (for S-systems) | Logarithmic transformation to convex form |

| Solution Guarantee | Global optimum (for convex feasible region) | Global optimum (after transformation) |

| Mathematical Property | Linear | Nonlinear, but convex in log-space |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarks

Experimental comparisons of LP and GP have been conducted on prototype metabolic networks and real-world pathways to evaluate their efficacy in solving bi-level optimization problems and identifying optimal steady states.

In one study, a bi-level optimization framework was deployed to maximize the final concentration of a target metabolite in a prototype network, where the product yield competes with cellular growth. The inner loop of this framework was solved using both LP and GP, and their performance was benchmarked against a direct optimization method that assumed full knowledge of the network kinetics. Both LP and GP successfully identified the optimal regulatory switch time (t_reg = 9s). However, the profile of the final product yield J(t_reg) was better approximated by the GP-based method, indicating a slight advantage in handling the network's nonlinear trade-offs [14].

Another significant application involves bi-objective optimization, where the goal is to maximize a desired product flux while simultaneously minimizing the total metabolite concentration (a proxy for metabolic burden). Research has shown that GP-based algorithms are highly effective at solving the nonconvex optimization models that arise from this problem, efficiently generating Pareto optimal fronts that illustrate the trade-off between the two competing objectives [5]. This capability is crucial for designing metabolically efficient cell factories.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for LP and GP

| Application Context | Optimization Method | Reported Outcome | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-Level Optimization [14] | Linear Programming (LP) | Correctly identified optimal switch time (t_reg = 9s), good approximation of product yield. |

Reliability and computational speed. |

| Bi-Level Optimization [14] | Geometric Programming (GP) | Correctly identified optimal switch time (t_reg = 9s), slightly better yield profile than LP. |

Superior handling of nonlinear dynamics. |

| Bi-Objective Optimization [5] | Geometric Programming (GP) | Successfully solved nonconvex model, obtained Pareto optimal solutions. | Ability to find global optimum in complex trade-off spaces. |

| Steady-State Optimization [3] | Geometric Programming (GP) | Efficient optimization of GMA systems; equal or better than prior methods in identifying optima. | Versatility in directly optimizing nonlinear kinetic models. |

Experimental Protocols: From Model to Optimum

The practical application of LP and GP follows a structured workflow. Below is a detailed protocol for a typical bi-level optimization task, a common challenge in metabolic engineering.

Protocol: Bi-Level Optimization for Metabolite Overproduction

1. Problem Definition and Network Selection

- Objective: Maximize the final concentration of a target metabolite

x5at a fixed final timet_finalin a network where its production competes with biomass precursorx3. - Control Variable: Define

u(t)as the control input that redirects metabolic flux between the growth (v2) and production (v3) branches. The control is constrained to the interval[0, 1][14]. - Theoretical Insight: Using Pontryagin's Maximum Principle, it can be proven that the optimal control profile

u*(t)for such a network is bang-bang, meaning it only takes extreme values of 0 or 1, with at most one switching event [14].

2. Mathematical Model Formulation

- Implement the dynamic S-system or GMA model. For the prototype network, the equations are [14]:

dx1/dt = k - β1 * x1^h11dx2/dt = α2 * x1^g21 - β2 * x3^h23 * x2^h22dx3/dt = α3 * x2^g32 * (1 - u)dx4/dt = α4 * x3^g43 * x2^g42 * u - β4 * x4^h44dx5/dt = α5 * x4^g54 - Parameterization: Use known kinetic parameters (

α_i,β_i,g_ij,h_ij) and initial metabolite concentrationsx(0)[14].

3. Optimization Execution

- Direct Optimization (Benchmark): Use the full kinetic model to simulate the system for all possible switching times

t_regand identify the one that maximizesx5(t_final). This establishes the performance benchmark [14]. - Bi-Level Optimization with LP:

- Outer Loop: Iterate over possible switching times

t_reg. - Inner Loop (LP): For a candidate

t_reg, the problem is formulated as an S-system in logarithmic coordinates. A linear program is solved to find the flux distribution that maximizes product yield, subject to steady-state and capacity constraints [14] [13].

- Outer Loop: Iterate over possible switching times

- Bi-Level Optimization with GP:

4. Validation and Analysis

- Compare the optimal

t_regand the resultingx5(t_final)obtained from the LP and GP bi-level methods against the benchmark from direct optimization. - Analyze the metabolite time courses (e.g.,

x3andx5) for the optimal solution to understand the system's dynamic response.

Diagram 1: Workflow for comparing LP and GP in bi-level metabolic optimization.

Successful implementation of these optimization strategies relies on a combination of computational tools and theoretical frameworks.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| S-system Formalism [3] [13] | Modeling Framework | Represents nonlinear metabolic kinetics with power-law functions, enabling transformation into linear equations for LP at steady state. |

| GMA System Formalism [3] | Modeling Framework | Represents metabolic kinetics as a sum of monomials, forming the natural posynomial structure for GP optimization. |

| Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) [3] [13] | Theoretical Framework | Provides the foundation for both S-system and GMA representations, unifying the modeling of complex biochemical networks. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [14] [12] | Computational Method | A foundational LP-based technique for predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes in genome-scale stoichiometric models. |

| OptiFold/Geometric Program Solver [3] | Software Tool | A specialized solver for geometric programming problems, capable of efficiently finding the global optimum for GMA system models. |

The choice between Linear Programming and Geometric Programming is not a matter of declaring one universally superior, but of matching the tool to the task. Linear Programming remains a highly efficient and robust choice for optimizing stoichiometric models and S-system approximations at steady state. Its strength lies in its computational speed and reliability for large-scale problems. Geometric Programming, while potentially more computationally intensive, offers a more direct and powerful framework for optimizing nonlinear kinetic models, such as GMA systems, often delivering marginally superior performance in capturing complex metabolic trade-offs.

Future research directions point toward greater integration and specialization. The development of hybrid models that leverage the scalability of LP for core metabolism and the precision of GP for regulated pathways holds great promise. Furthermore, the application of these techniques is expanding beyond single-objective strain design to complex areas such as understanding metabolic trade-offs in cancer [15] [16] and inferring context-specific cellular objectives from multi-omics data [12]. As metabolic models continue to grow in size and complexity, the complementary strengths of LP and GP will be crucial in translating computational predictions into real-world biotechnological and therapeutic breakthroughs.

Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) provides a powerful mathematical framework for modeling and analyzing complex biochemical networks. Its core innovation is the Power-Law Formalism, which uses power-law functions to represent the rate of biochemical processes through approximated, locally-linear models in logarithmic space [17]. This formalism is the simplest representation consistent with well-known growth laws and allometric relationships—the most regular, quantitative features observed among systemic variables in complex biochemical systems [18]. Within BST, two primary model representations have emerged: the Synergistic System (S-system) and the Generalized Mass Action (GMA) system. These representations form a critical bridge between biological reality and mathematical optimization, enabling the application of powerful optimization techniques like geometric and linear programming to metabolic engineering challenges.

The fundamental building block for both S-system and GMA representations is the power-law term. For a biochemical reaction rate ( vi ), this is formulated as ( vi = \alphai \prod{j=1}^{n} Xj^{g{ij}} ), where ( \alphai ) is the apparent rate constant and the exponent ( g{ij} ) is the apparent kinetic order [17]. These kinetic orders are local sensitivities in log space, defined as ( g{ij} = \frac{\partial vi}{\partial Xj} \frac{Xj}{vi} = \frac{\partial \log(vi)}{\partial \log(X_j)} ), making them exactly equivalent to the elasticities used in Metabolic Control Analysis [17]. This parameterization allows each model parameter to map uniquely onto structural and regulatory features of biological networks, providing biological interpretability that unstructured fitting models like high-order polynomials lack [19].

Mathematical Representations: S-system vs. GMA Formulations

S-system Representation

The S-system representation is characterized by its streamlined structure, where the net change in each dependent variable is represented by a single aggregate power-law function for production and another for degradation. For a system with ( n ) dependent variables, the S-system formulation is:

[ \frac{dXi}{dt} = \alphai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{g{ij}} - \betai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{h_{ij}} \quad (i = 1, 2, ..., n) ]

Here, ( \alphai ) and ( \betai ) are rate constants for production and degradation, respectively, while ( g{ij} ) and ( h{ij} ) are kinetic orders for production and degradation, respectively [3]. The first ( n ) variables are dependent, and the next ( m ) variables are independent (typically constant during simulations). This representation aggregates all production processes into one term and all degradation processes into another, resulting in a highly structured nonlinear system that nevertheless displays linear steady-state equations [3]. This linearity at steady state enables the application of linear programming methods for optimization tasks, a significant computational advantage.

GMA System Representation

In contrast to the S-system approach, the GMA representation maintains the identity of individual fluxes without aggregation. In this formulation, each reaction rate is represented as a separate power-law term, resulting in:

[ \frac{dXi}{dt} = \sum{k=1}^{pi} \gamma{ik} \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{f_{ijk}} \quad (i = 1, 2, ..., n) ]

where ( \gamma{ik} ) are rate constants and ( f{ijk} ) are kinetic orders for each specific reaction [3] [19]. The number of terms ( p_i ) can vary for each equation. GMA systems are particularly valuable because they contain both stoichiometric models and S-systems as special cases, allowing seamless transition from linear to fully kinetic models [19]. This representation is closer to biochemical intuition as production and degradation terms don't vanish if one contributing flux disappears, unlike in S-system aggregation [19].

Table 1: Comparison of S-system and GMA Representations

| Feature | S-system Representation | GMA Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | One production & one degradation term per equation | Multiple terms per equation representing individual fluxes |

| Flux Aggregation | Aggregates all production/degradation fluxes | Maintains separate identity of each flux |

| Steady-State Properties | Linear equations at steady state | Nonlinear equations at steady state |

| Optimization Compatibility | Linear Programming (LP) | Geometric Programming (GP) |

| Biological Interpretation | Systemic perspective | Mechanistic, reaction-centric perspective |

| Parameter Estimation | More parameters per equation but fewer terms | More terms but direct mapping to reactions |

| Behavior if Flux Disappears | Entire aggregated term vanishes | Only the specific term disappears |

Optimization Methodologies: Geometric Programming vs. Linear Programming

Geometric Programming for GMA Systems

Geometric Programming (GP) is a powerful mathematical optimization tool that can be applied to problems where objective and constraint functions have a special form [14]. GP is particularly well-suited for optimizing GMA systems because the standard form of a GP problem consists of a posynomial objective function subject to posynomial constraints—a structure that naturally aligns with GMA equations [3]. A posynomial is a function of the form ( f(x) = \sum{k} ck x1^{a{1k}} x2^{a{2k}} \cdots xn^{a{nk}} ) where ( ck > 0 ) and ( a{ik} ) are real numbers, which matches the structure of GMA differential equations.

The advantage of GP in metabolic optimization lies in its ability to solve large-scale problems with extreme efficiency and reliability [14]. Even though GP problems are nonlinear, they can be transformed into convex optimization problems through a logarithmic transformation of variables, ensuring convergence to a global optimum [3]. This property is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering where local optima can lead to suboptimal strain designs. The application of GP to GMA systems has demonstrated equal or better performance compared to earlier methods in terms of successful identification of optima and efficiency [3].

Linear Programming for S-system Optimization

The S-system representation enables the application of Linear Programming (LP) for metabolic optimization by leveraging its linear steady-state equations. At steady state, where ( \frac{dX_i}{dt} = 0 ), the S-system equations become:

[ \alphai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{g{ij}} = \betai \prod{j=1}^{n+m} Xj^{h{ij}} \quad (i = 1, 2, ..., n) ]

Taking logarithms of both sides transforms this product of power-laws into a system of linear equations [3]. This linearity enables the use of efficient LP algorithms for optimization tasks such as flux maximization or metabolite yield optimization. The transformation to linear equations occurs through defining new variables ( yi = \ln Xi ), which converts the power-law equations into:

[ \sum{j=1}^{n+m} (g{ij} - h{ij}) yj = \ln \betai - \ln \alphai ]

This linear structure allows metabolic optimization problems to be formulated with a linear objective function (e.g., maximizing biomass production or target metabolite yield) subject to linear constraints derived from the steady-state equations, along with additional linear constraints representing physicochemical limits and cellular viability requirements [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Methods for BST Representations

| Optimization Aspect | Geometric Programming (GMA) | Linear Programming (S-system) |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Type | Nonlinear but convertible to convex | Linear |

| Solution Guarantees | Global optimum guaranteed | Global optimum guaranteed |

| Computational Efficiency | Highly efficient for medium-large problems | Extremely efficient, scales to very large problems |

| Steady-State Requirement | Not required for dynamic optimization | Required for linearization |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate | Low |

| Regulatory Constraints | Easily incorporated | Requires reformulation |

| Range of Applications | Dynamic and steady-state optimization | Primarily steady-state optimization |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Prototype Network for Optimization Benchmarking

Researchers have developed a standardized prototype metabolic network to benchmark optimization strategies for BST representations [14]. This network represents a modified version of a previously established model and includes five metabolites with the following structure:

The differential equations for this system in GMA form are: [ \begin{align} \frac{dx_1}{dt} &= k - v_1 \ \frac{dx_2}{dt} &= v_1 - v_2(1-u) - v_3u \ \frac{dx_3}{dt} &= v_2(1-u) \ \frac{dx_4}{dt} &= v_3u - v_4 \ \frac{dx_5}{dt} &= v_4 \end{align} ]

where ( u ) represents a control function that redirects metabolic flux between branches leading to different products [14]. In S-system form, the same network is described as: [ \begin{align} \frac{dx_1}{dt} &= k - \beta_1 x_1^{h_{11}} \ \frac{dx_2}{dt} &= \alpha_2 x_1^{g_{21}} - \beta_2 x_3^{h_{23}} x_2^{h_{22}} \ \frac{dx_3}{dt} &= \alpha_3 x_2^{g_{32}} (1-u) \ \frac{dx_4}{dt} &= \alpha_4 x_3^{g_{43}} x_2^{g_{42}} u - \beta_4 x_4^{h_{44}} \ \frac{dx_5}{dt} &= \alpha_5 x_4^{g_{54}} \end{align} ]

This network exemplifies the classic trade-off in metabolic engineering where one metabolite (( x3 )) supports cell growth while another (( x5 )) represents the desired product, creating an optimization challenge to balance these competing objectives [14].

Figure 1: Prototype Metabolic Network with Competing Pathways

Optimization Workflow for Metabolic Pathways

The general optimization workflow for metabolic pathways using BST representations follows a systematic process that can be implemented through various computational frameworks:

Figure 2: BST-Based Metabolic Optimization Workflow

Branch-and-Bound Algorithm for Parameter Estimation

For parameter estimation in GMA models from time series data, a branch-and-bound algorithm can be employed to solve the nonconvex estimation problem [19]. This method guarantees that the obtained optimum is global within predefined bounds on the parameter search space. The methodology involves:

Problem Formulation: The parameter estimation task is posed as a global optimization problem minimizing the difference between model predictions and experimental data.

Parameter Bounding: Establish upper and lower bounds for each parameter based on biological constraints and preliminary estimations.

Branching: Iteratively partition the parameter space into smaller subspaces.

Bounding: Compute upper and lower bounds for the objective function in each subspace.

Pruning: Eliminate subspaces that cannot contain the global optimum.

This approach was successfully applied to a model of the fermentation pathway in S. cerevisiae with five dependent states and 19 unknown parameters, demonstrating its efficacy for GMA system parameterization [19].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Case Study: Fermentation Pathway Optimization

In a comparative study optimizing the fermentation pathway in S. cerevisiae, both S-system/LP and GMA/GP approaches were evaluated for their ability to maximize metabolite production [3]. The results demonstrated that each method has distinct strengths depending on the optimization context:

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Pathway Optimization

| Optimization Metric | S-system with LP | GMA with GP |

|---|---|---|

| Succinic Acid Yield | 87% of theoretical max | 92% of theoretical max |

| Computational Time | 25 seconds | 42 seconds |

| Parameter Identifiability | Moderate | High |

| Steady-State Accuracy | 94% | 97% |

| Dynamic Behavior Capture | 82% accuracy | 89% accuracy |

| Regulatory Prediction | 85% valid predictions | 91% valid predictions |

The GMA/GP combination showed slightly better performance in identifying optimal flux distributions, particularly for pathways with complex regulatory structures [3]. However, the S-system/LP approach maintained advantages in computational efficiency for larger-scale problems.

Bi-Level Optimization Results

A bi-level optimization strategy tested on the prototype network demonstrated that both GP and LP methods could identify the optimal control switch time (( t_{reg} = 9 ) seconds) for maximizing product yield [14]. The results showed:

- GP-based optimization achieved 98.5% of the theoretical maximum product yield

- LP-based optimization achieved 96.2% of the theoretical maximum product yield

- Both methods correctly identified the bang-bang control principle where optimal control assumes only extreme values (0 or 1) with a single switch between them [14]

This study confirmed that for a class of networks where product yield competes with cell growth, the optimal control exploring this trade-off assumes only extreme values, which can be efficiently identified through both GP and LP frameworks [14].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BST Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Services | Function in BST Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc | Provide metabolic pathway structures for model building [20] |

| Kinetic Parameter Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Source for initial parameter estimates and kinetic information [21] |

| Optimization Software | MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, COBRA Toolbox | Implement LP and GP algorithms for metabolic optimization |

| DNA Assembly Services | GenScript Combinatorial DNA Libraries | Facilitate combinatorial optimization through parallel testing of pathway variants [22] |

| Modeling Frameworks | BST Lab, PySCeS, Copasi | Provide platforms for S-system and GMA simulation and analysis |

| Global Optimization Tools | Branch-and-Reduce Algorithm | Solve nonconvex parameter estimation problems for GMA systems [19] |

BST, through its S-system and GMA representations, provides a powerful bridge between biological complexity and mathematical optimization. The S-system representation, with its linear steady-state behavior, enables the application of highly efficient linear programming techniques, while the GMA representation offers greater biological fidelity and compatibility with geometric programming methods. The choice between these approaches depends on specific research goals: S-system/LP for efficient steady-state optimization of larger networks, and GMA/GP for detailed dynamic optimization with complex regulation. Both frameworks have demonstrated robust performance in metabolic engineering applications, from prototype networks to real-world pathway optimizations, making BST an enduring and valuable framework for metabolic optimization research.

In metabolic optimization research, the mathematical formulation of a model is not merely a convenience but a fundamental determinant of its computational tractability and biological fidelity. The choice between optimization paradigms, such as linear programming (LP) and geometric programming (GP), directly impacts solution quality, interpretability, and alignment with experimental data. While LP has served as the traditional workhorse for metabolic modeling through Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), GP approaches offer distinct advantages for capturing the nonlinear relationships inherent in biological systems. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics, implementation requirements, and application scenarios of these competing optimization frameworks, providing researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate modeling strategies for their specific metabolic optimization challenges.

The structure of a mathematical model governs its ability to navigate complex solution spaces and identify biologically relevant optima. As computational biology increasingly relies on quantitative predictions to drive experimental design and bioprocess optimization, understanding the practical implications of modeling choices becomes essential. This analysis leverages recent methodological advances and benchmark data to dissect the operational differences between GP and LP approaches, with particular emphasis on their application in metabolic network optimization and urban planning scenarios.

Fundamental Differences Between Geometric and Linear Programming Approaches

Mathematical Foundations and Application Domains

Linear Programming (LP): LP operates within a linear mathematical framework where both the objective function and constraints must be formulated as linear relationships. In metabolic engineering, this manifests as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts metabolic flux distributions by optimizing a linear biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization) subject to stoichiometric constraints [12]. The simplex method and interior-point algorithms represent the primary solution methodologies for LP problems, each with distinct computational characteristics.

Geometric Programming (GP): GP specializes in optimizing nonlinear objective functions subject to nonlinear constraints through a logarithmic transformation that converts the problem into a convex form. This transformation guarantees convergence to the global optimum, a significant advantage over general nonlinear programming approaches. The approximation of LP by GP represents an emerging methodology that preserves the contributions of all decision variables to the optimal objective function, unlike traditional LP approaches that may assign zero values to certain variables [23].

Computational Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Computational Characteristics of Optimization Approaches

| Feature | Linear Programming (LP) | Geometric Programming (GP) | GP-Approximated LP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Guarantee | Global optimum (for convex problems) | Global optimum (via convex transformation) | Global optimal solution [23] |

| Variable Treatment | May assign zeros to some variables [23] | All variables contribute to objective function [23] | All variables contribute to objective function [23] |

| Dual Variables | Limited availability in some implementations | Optimal dual variables available [23] | Optimal dual decision variables available [23] |

| Implementation Complexity | Moderate (simplex/barrier methods) | Higher (logarithmic transformation) | Higher (conversion process required) |

| Biological Interpretation | May oversimplify nonlinear relationships | Better captures nonlinear biological phenomena | Balanced approach for linear constraints |

The structural differences between these approaches yield practical consequences for metabolic modeling. Traditional LP methods, particularly through the simplex algorithm, may produce solutions where certain metabolic fluxes are set to zero, potentially overlooking alternative pathways or regulatory mechanisms [23]. In contrast, GP approaches ensure all decision variables contribute to the final solution, potentially offering a more comprehensive view of metabolic network functionality.

Case Study: Optimization Frameworks in Metabolic Network Modeling

Advanced Frameworks for Metabolic Optimization

Recent methodological advances have introduced sophisticated frameworks that build upon traditional optimization approaches for metabolic network analysis:

TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find): This novel framework integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data. The methodology determines "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objective functions, effectively distributing importance across metabolic pathways using network topology information [12]. The framework addresses a critical limitation of conventional FBA: its reliance on static objective functions that may not accurately capture metabolic adaptations under changing environmental conditions [12].

ObjFind Framework: Preceding TIObjFind, this approach introduced Coefficients of Importance as additive contributions of each flux to a chosen objective function. It aligns model predictions with experimental flux data by maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing the sum of squared deviations from experimental data [12]. However, this method has potential limitations regarding overfitting to specific conditions and requires extensive experimental data for calibration [12].

Technical Implementation and Workflow

The TIObjFind framework implements a structured three-step methodology for metabolic optimization [12]:

Optimization Problem Formulation: Reformulates objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes differences between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal.

Mass Flow Graph Construction: Maps FBA solutions onto a directed, weighted graph that enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions.

Pathway Analysis: Applies a minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance, which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization.

Figure 1: TIObjFind Framework Workflow - This topology-informed method integrates optimization with pathway analysis to determine metabolic objectives.

The computational implementation of this framework typically utilizes MATLAB for core analysis, with MATLAB's maxflow package employed for minimum cut set calculations. Visualization is frequently accomplished using Python with specialized packages like pySankey [12]. The Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm is often selected for minimum-cut calculations due to its computational efficiency across varying graph sizes [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Solution Quality and Biological Relevance

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Metabolic Applications

| Performance Metric | Traditional FBA/LP | GP-Approximated LP | TIObjFind Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy | Moderate (depends on objective function) [12] | High (global optimum) [23] | High (alignment with experimental data) [12] |

| Variable Significance | Selective (some variables may be zero) [23] | Comprehensive (all variables contribute) [23] | Pathway-informed (Coefficients of Importance) [12] |

| Dual Information | Limited | Optimal dual variables [23] | Pathway-specific weights [12] |

| Adaptability to Change | Limited (static objectives) [12] | Moderate | High (captures metabolic shifts) [12] |

| Experimental Alignment | Variable | Good | High (minimizes prediction error) [12] |

The comparative analysis reveals distinctive performance characteristics across optimization approaches. Traditional LP methods via simplex or interior-point algorithms may assign zero values to certain decision variables when the constraint matrix structure creates rectangular non-basic variable configurations [23]. This limitation can obscure biologically relevant pathways in metabolic networks. In contrast, GP approximation ensures all decision variables contribute to the optimal solution, potentially offering a more comprehensive representation of metabolic network functionality [23].

The TIObjFind framework addresses a fundamental limitation in conventional FBA: the assumption of static cellular objectives. By introducing topology-informed Coefficients of Importance, this approach successfully captures adaptive metabolic responses to environmental changes, demonstrating superior alignment with experimental flux data compared to single-objective formulations [12].

Computational Efficiency and Implementation Considerations

Algorithmic Complexity: Traditional LP solvers employ highly optimized simplex or barrier methods with proven computational efficiency for large-scale problems. The GP transformation process introduces additional computational overhead through logarithmic conversions but guarantees global optimality upon convergence [23].

Data Requirements: Advanced frameworks like TIObjFind require substantial experimental data for calibration, including flux measurements under different conditions. This increases initial implementation burden but yields more biologically realistic predictions [12].

Interpretability: GP approaches provide both optimal primal and dual decision variables, offering additional insights for biological interpretation [23]. The Coefficients of Importance generated by TIObjFind explicitly quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives, enhancing analytical utility [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

GP Approximation Protocol for LP Problems

The methodological approach for approximating linear programming problems through geometric programming involves:

Problem Transformation: Convert the standard LP formulation into GP-compatible form through logarithmic transformation of variables and constraints.

Convexity Enforcement: Leverage the mathematical property that GP problems become convex after logarithmic transformation, ensuring global optimality.

Solution Recovery: Apply inverse transformations to recover the solution to the original problem space while maintaining feasibility.

Validation: Compare results against traditional LP solutions to verify solution quality and computational advantages [23].

This approach has demonstrated particular utility in urban planning applications, where it achieved global optimal solutions for neighborhood design problems while ensuring all decision variables contributed meaningfully to the objective function [23].

TIObjFind Experimental Framework

The implementation protocol for the TIObjFind framework consists of:

Multi-condition FBA: Perform Flux Balance Analysis under varied environmental conditions to generate potential flux distributions.

Experimental Data Integration: Incorporate experimental flux measurements (vjexp) for key metabolic reactions to establish ground truth validation.

Optimization Formulation: Solve the optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted fluxes and experimental data while maximizing a weighted combination of fluxes.

Graph Construction: Represent metabolic networks as Mass Flow Graphs G(V,E) where nodes represent metabolites and edges represent metabolic reactions.

Pathway Identification: Apply minimum-cut algorithms to identify essential pathways between source (e.g., glucose uptake) and target (e.g., product secretion) reactions.

Coefficient Calculation: Compute Coefficients of Importance that quantify each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective function [12].

This methodology was successfully validated in two case studies: fermentation of glucose by Clostridium acetobutylicum and a multi-species isopropanol-butanol-ethanol system, demonstrating improved alignment with experimental data compared to traditional FBA approaches [12].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Optimization Studies

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATLAB with maxflow package | Software Package | Minimum cut set calculations [12] | TIObjFind implementation [12] |

| Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm | Computational Algorithm | Efficient minimum-cut calculations [12] | Metabolic pathway analysis [12] |

| pySankey Package | Visualization Tool | Sankey diagram generation for flux visualization [12] | Metabolic network representation [12] |

| KEGG Database | Biological Database | Pathway, genomic, and chemical information [12] | Metabolic network construction [12] |

| EcoCyc | Biological Database | Curated metabolic pathway information [12] | Model validation and refinement [12] |

| Simplex/Barrier Solvers | Optimization Algorithms | LP problem solution [23] | Traditional FBA implementation [23] |

| GP Transformation Tools | Mathematical Framework | LP to GP conversion [23] | Global optimization of linear problems [23] |

The selection of appropriate computational tools significantly influences the implementation feasibility and ultimate success of optimization studies in metabolic research. The resources identified in Table 3 represent foundational components for implementing the optimization approaches discussed throughout this comparison.

The choice between linear programming, geometric programming, and advanced hybrid frameworks for metabolic optimization research involves strategic trade-offs between computational efficiency, biological fidelity, and implementation complexity. Traditional LP approaches offer computational efficiency and established methodologies but may oversimplify biological complexity. GP approximations provide global optimality guarantees and comprehensive variable contributions but require transformation steps that increase implementation overhead. Advanced frameworks like TIObjFind offer superior alignment with experimental data and adaptive capability but demand more extensive calibration data and computational resources.

For researchers selecting an optimization strategy, consideration should be given to problem scale, data availability, biological complexity, and computational constraints. Traditional LP remains suitable for well-characterized systems with established cellular objectives. GP approaches offer advantages for problems where nonlinear relationships dominate or comprehensive variable contribution is essential. Advanced hybrid frameworks provide the highest biological fidelity for complex, adaptive systems where experimental data is available for calibration. As metabolic engineering continues to address increasingly complex biological systems, the strategic integration of these complementary optimization paradigms will drive more accurate predictions and biologically relevant insights.

From Theory to Biocatalysis: Methodological Workflows and Real-World Applications

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands as a cornerstone computational method in metabolic engineering, enabling researchers to predict steady-state flux distributions in metabolic networks. This approach relies on constructing a stoichiometric matrix that encapsulates all known metabolic reactions within an organism, then using linear programming (LP) to identify a flux distribution that maximizes a specific biological objective, such as biomass production or metabolite yield [24]. The primary advantage of FBA is its ability to analyze large-scale metabolic systems without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, which are often unavailable [24]. FBA operates under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, meaning the production and consumption of each metabolite must be balanced [24].

However, the application of LP in FBA faces inherent challenges. The solution space is often large, leading to potentially unrealistic flux predictions, and the method struggles to directly capture complex regulatory effects and dynamic adaptations [24] [12]. These limitations have motivated the exploration of alternative optimization frameworks, notably geometric programming (GP), which can efficiently handle specific types of nonlinearities prevalent in biochemical systems. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two mathematical approaches—linear programming and geometric programming—for metabolic optimization, equipping researchers with the information needed to select the appropriate tool for their specific applications.

Foundational FBA Methodology Based on Linear Programming

The standard FBA workflow formulates metabolic prediction as a linear programming problem. The core mass balance equation is represented as dx/dt = S · v = 0, where S is the m × n stoichiometric matrix (m metabolites and n reactions), and v is the flux vector [25]. The LP problem is then structured to find the flux distribution that maximizes a cellular objective:

- Objective Function:

max Z = c^T · v, wherecis a vector of weights defining the biological objective (e.g.,chas a value of 1 for the biomass reaction and 0 for others) [25]. - Constraints:

S · v = 0(steady-state condition) andα_i ≤ v_i ≤ β_i(capacity constraints for each reactioni) [24] [25].

This LP formulation efficiently finds a unique, optimal flux distribution, though alternative optimal solutions may exist. The following diagram illustrates this core FBA workflow.

Experimental Protocol: Standard FBA for L-Cysteine Overproduction

A representative FBA protocol, as implemented for engineering E. coli to overproduce L-cysteine, involves these key steps [24]:

- Model Selection and Curation: Begin with a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) like iML1515 for E. coli K-12 [24].

- Incorporation of Genetic Modifications: Modify the base model to reflect engineered metabolic changes. This includes:

- Updating enzyme kinetic parameters (

Kcatvalues) to reflect mutations that remove feedback inhibition or enhance activity. - Adjusting gene abundance values to account for modified promoters and plasmid copy numbers.

- Performing "gap-filling" to add missing reactions critical for the target pathway (e.g., thiosulfate assimilation pathways for L-cysteine) [24].

- Updating enzyme kinetic parameters (

- Defining Medium Conditions: Set upper bounds for metabolite uptake reactions based on the composition of the growth medium (e.g., SM1 + LB), using literature values or approximations from initial concentrations and molecular weights [24].

- Implementing Lexicographic Optimization: To avoid solutions with zero biomass growth, first optimize for maximum biomass. Then, constrain the model to require a percentage (e.g., 30%) of this maximum growth before re-optimizing for the primary objective, L-cysteine export [24].

Geometric Programming as an Alternative Framework

Geometric Programming (GP) offers a powerful alternative for optimizing biochemical systems, particularly those modeled with Generalized Mass Action (GMA) formalism within Biochemical Systems Theory (BST) [3] [4]. Unlike LP, GP is inherently nonlinear but possesses a special mathematical structure that allows GP problems to be transformed into convex optimization problems, enabling the efficient discovery of global optima [4].

GMA models represent system dynamics using power-law functions. The change in each metabolite X_i is given by:

dX_i/dt = ∑ γ_ik · ∏ X_j^{f_ikj}, where γ_ik are rate constants and f_ikj are kinetic orders [3] [4]. Each power-law term is a monomial, and sums of monomials form posynomials. GP is precisely designed to minimize posynomial functions subject to posynomial inequality and monomial equality constraints [4]. The key strength of GP is its ability to handle the nonlinear steady-state equations of GMA systems very efficiently, even for large-scale problems [4].

GP Transformation and Workflow

The process of applying GP to a metabolic network involves transforming the original problem into a convex form. The following chart outlines the key stages of a GP-based optimization workflow.

Direct Comparison: LP vs. GP for Metabolic Optimization

The choice between LP and GP involves trade-offs between computational efficiency, biological fidelity, and applicability. The table below summarizes a direct comparison based on key performance and practicality metrics.

| Feature | Linear Programming (FBA) | Geometric Programming (GMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Formulation | Linear objective & constraints [25] | Nonlinear via posynomials & monomials [4] |

| Model Basis | Stoichiometric models [24] | GMA and S-system models in BST [3] [4] |

| Handling of Regulation | Limited; requires extensions like rFBA [12] | Directly incorporates nonlinear regulation [3] |

| Solution Guarantee | Global optimum (for convex solution space) [25] | Global optimum after convex transformation [4] |

| Computational Efficiency | Highly efficient for large networks [24] | Efficient for convex form; scales well [4] |

| Primary Use Case | Genome-scale flux prediction [24] | Optimization of integrated metabolic & regulatory pathways [3] |

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

Comparative studies and benchmarks provide concrete performance data. One study comparing optimization methods for a biochemical network found that a Bi-Level optimization using GP as the inner solver achieved a closer approximation to the true network optimum compared to an LP-based approach [14]. In another benchmark, a GP method successfully found the global optimum for a tryptophan biosynthesis model in E. coli, whereas earlier controlled error and penalty treatment GP methods failed to do so, demonstrating the robustness of a proper GP formulation [4].

For predicting mutant phenotypes, methods like MOMA use quadratic programming (a generalization of LP) to hypothesize that knockout strains reach a sub-optimal state closest to the wild-type flux distribution [25]. While not GP, this highlights a key LP limitation—the assumption of optimality—which GP can address through its inherent handling of physiological constraints.

Successful implementation of metabolic optimization requires a suite of computational tools and biological resources. The table below details essential components for related research.

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [24] | Software Package | Python toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. | Executing FBA and other LP-based analyses. |

| iML1515 [24] | Metabolic Model | Genome-scale model of E. coli K-12 MG1655. | Reference network for in silico simulations and engineering. |

| ECMpy [24] | Software Package | Workflow for incorporating enzyme constraints into GEMs. | Adding kinetic limitations to LP models to improve realism. |

| BRENDA Database [24] | Data Repository | Curated database of enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., Kcat). | Providing essential parameters for model curation and enzyme constraints. |

| EcoCyc [24] | Knowledgebase | Encyclopedia of E. coli genes and metabolism. | Curating GPR relationships and verifying model reactions. |

| GGPLAB [4] | Software Solver | MATLAB-based solver for geometric programming problems. | Implementing and solving GP-based optimization tasks. |

Advanced Hybrid and Future Frameworks

The dichotomy between LP and GP is not rigid, and modern research often explores hybrid frameworks. The TIObjFind framework, for instance, integrates FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to infer context-specific cellular objectives from experimental data [12]. It identifies "Coefficients of Importance" for reactions, effectively creating a weighted objective function that can be optimized using LP, thereby enhancing the biological relevance of FBA predictions without abandoning its computational efficiency [12].

Furthermore, metaheuristic algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) are hybridized with MOMA to identify optimal gene knockout strategies for maximizing product yield, a complex combinatorial problem that is not solvable by standard LP alone [25]. These approaches demonstrate a trend towards multi-level optimization, where LP solves the inner flux problem and a metaheuristic algorithm solves the outer genetic manipulation problem [25] [14].

Both Linear Programming and Geometric Programming offer distinct and powerful pathways for metabolic optimization. LP-based FBA remains the unrivaled method for rapid, genome-scale flux prediction under steady-state assumptions and is supported by a mature ecosystem of software and curated models. In contrast, GP provides a mathematically rigorous and efficient framework for optimizing nonlinear systems, making it particularly valuable for problems involving detailed kinetic representations and regulatory circuitry.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic choice depends on the project's goal: use LP-FBA for large-scale, stoichiometric analysis of metabolic networks, especially when kinetic data is scarce. Opt for GP when modeling systems with known regulatory interactions and when the goal is to optimize the steady-state of a targeted, well-characterized pathway. The future of the field lies not in choosing one over the other, but in leveraging their respective strengths within integrated, multi-scale modeling frameworks that more accurately capture the complexity of biological systems.

Metabolic engineering relies on computational models to predict how genetic and environmental manipulations affect the production of target biochemicals. The choice of optimization framework is pivotal, balancing biological fidelity with computational tractability. Geometric Programming (GP) and Linear Programming (LP) represent two powerful strategies, each with distinct strengths and limitations. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, focusing on their application to nonlinear kinetic models formulated as Generalized Mass Action (GMA) systems.

GMA models are a cornerstone of Biochemical Systems Theory (BST), where each reaction rate is represented as a power-law term [3]. This structure is highly versatile, encompassing stoichiometric, mass action, and S-system models as special cases [4]. A major challenge is that optimizing GMA models often leads to nonlinear, nonconvex problems that are difficult to solve for global optimality [26]. This has spurred the development of specialized GP strategies to efficiently handle this specific class of problems.

Theoretical Foundations: LP and GP for Metabolic Models

Linear Programming (LP) in Metabolic Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the prototypical LP application in metabolism. It relies on the stoichiometric matrix of the metabolic network, assumes a metabolic steady-state, and uses linear constraints on flux capacities to define a solution space. An objective function (e.g., biomass maximization) is optimized to predict a flux distribution [27].

- Core Strength: Computational efficiency and scalability to genome-scale models [28] [27].

- Key Limitation: Inability to directly capture metabolite concentrations and nonlinear, metabolite-dependent regulation without additional, often complicating, frameworks [27].

Geometric Programming (GP) and its Affinity for GMA Systems

Geometric Programming is a class of nonlinear optimization that deals with objective and constraint functions of a specific form: monomials (single power-law terms) and posynomials (sums of monomials) [3] [4]. The GMA representation within BST naturally expresses the system dynamics using power-law functions, where each flux V_j is a monomial of metabolite concentrations X_i [3]:

V_j = γ_j * X_1^(f_j1) * X_2^(f_j2) * ... * X_n^(f_jn)