Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling: A Systems Biology Framework for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

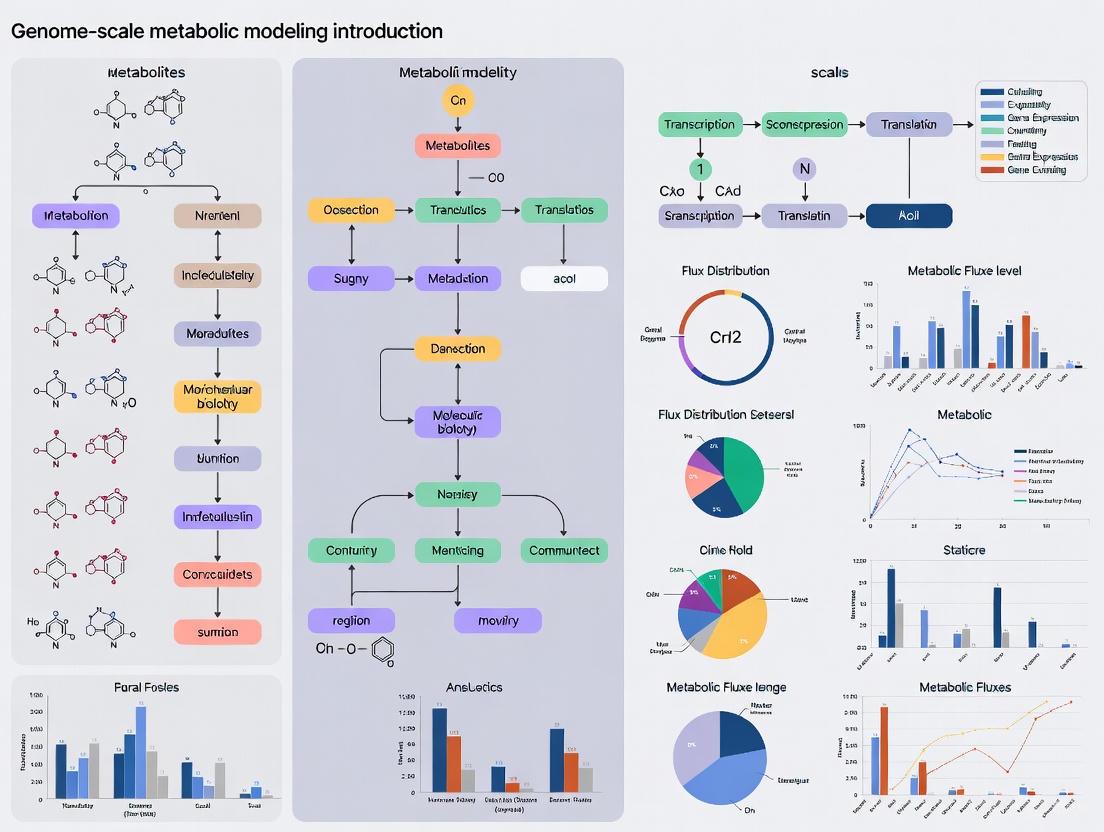

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), computational tools that define gene-protein-reaction relationships for an organism's entire metabolic network.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling: A Systems Biology Framework for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), computational tools that define gene-protein-reaction relationships for an organism's entire metabolic network. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, reconstruction methodologies, and cutting-edge applications. The scope extends from core concepts and constraint-based analysis techniques to advanced troubleshooting and validation approaches. It highlights how GEMs integrate multi-omics data to predict metabolic fluxes, identify drug targets in pathogens and cancer, design live biotherapeutic products, and enable personalized medicine strategies through machine learning integration.

Core Principles and Evolution of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) are computational reconstructions of the metabolic networks of organisms that define the relationship between genotype and phenotype through gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations [1] [2]. These stoichiometry-based, mass-balanced models encompass all known metabolic reactions within an organism, providing a systems-level framework for simulating metabolic capabilities [2]. Since the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae was published in 1999, the field has expanded dramatically, with models now available for thousands of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [2]. By mathematically representing metabolism, GEMs enable researchers to predict metabolic fluxes, understand organismal capabilities under different conditions, and design biological systems with preferred features [3].

The fundamental value of GEMs lies in their ability to serve as scaffolds for integrating and contextualizing various types of 'omics' data (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [3] [1]. Unlike traditional metabolic pathway databases, GEMs maintain stoichiometric balance for all reactions, ensuring mass and energy conservation while enabling system-level metabolic response analysis through flux simulations [1]. This unique combination of features has established GEMs as indispensable tools in fields ranging from industrial biotechnology to systems medicine, facilitating both basic scientific discovery and applied biomedical research [1] [4].

Core Components and Mathematical Framework of GEMs

Structural Elements of GEMs

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models are built upon several interconnected components that collectively represent an organism's metabolic potential. The core elements include:

- Metabolites: All known metabolic compounds in the organism, serving as reactants and products in biochemical reactions.

- Reactions: Biochemical transformations between metabolites, complete with stoichiometric coefficients that quantify input and output relationships.

- Genes: All metabolic genes annotated in the organism's genome.

- GPR Associations: Boolean relationships that connect genes to enzymes and enzymes to reactions, directly linking genomic information to metabolic capabilities [1] [2].

These components are systematically organized into a structured knowledgebase that can be computationally queried and simulated. The GPR associations are particularly crucial as they encode the genetic basis for metabolic functionality, enabling researchers to predict the metabolic consequences of genetic perturbations [2].

Mathematical Representation

The mathematical foundation of GEMs centers on the stoichiometric matrix (S matrix), where each element Sij represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [1]. This matrix formulation allows modeling of the entire metabolic network under the assumption of steady-state mass balance, meaning there is no net accumulation of metabolites within the system [1].

Table 1: Key Components of the Stoichiometric Matrix in GEMs

| Matrix Element | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning | Example Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sij > 0 | Metabolite i is produced in reaction j | Product of biochemical reaction | ATP produced in glycolysis |

| Sij < 0 | Metabolite i is consumed in reaction j | Substrate of biochemical reaction | Glucose consumed in glycolysis |

| Sij = 0 | Metabolite i is not involved in reaction j | No participation in reaction | Oxygen in anaerobic reactions |

This mathematical framework enables the application of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based optimization technique that predicts metabolic flux distributions by optimizing an objective function (typically biomass production) subject to stoichiometric and capacity constraints [3] [2]. The general formulation of FBA is:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv Subject to: S∙v = 0 and: vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Where Z is the objective function, c is a vector of weights, v is the flux vector, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and vmin/vmax represent flux constraints [1].

GEM Reconstruction: Methodologies and Workflows

Reconstruction Pipeline

The process of reconstructing a high-quality GEM follows a systematic workflow that transforms genomic information into a predictive metabolic model. The reconstruction pipeline consists of four major phases, each with specific tasks and validation steps:

Manual Curation and Quality Assurance

While automated reconstruction tools have accelerated GEM development, manual curation remains essential for producing high-quality models [2]. This process involves:

- Gap Analysis: Identifying metabolic gaps where known metabolic functions lack complete pathways and implementing gap-filling strategies [1].

- Biomass Composition: Defining the precise molecular composition of biomass for the target organism, including amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and cofactors [2].

- Thermodynamic Validation: Incorporating thermodynamic information to verify reaction directionality and ensure feasibility of metabolic flux distributions [2].

The quality of a reconstructed GEM is typically validated through gene essentiality analysis, where in silico knockouts are compared with experimental essentiality data [1]. For well-established models like the E. coli GEM iML1515, this approach has achieved prediction accuracies exceeding 90% [2]. Additional validation includes comparing simulated growth phenotypes across different nutrient conditions with experimental measurements and testing the model's ability to predict substrate utilization capabilities [1].

Analytical Applications of GEMs

Constraint-Based Analysis Techniques

GEMs support a diverse set of analytical techniques that enable systems-level investigation of metabolic capabilities:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Predicts optimal metabolic flux distributions under steady-state assumptions by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production) [3] [2].

- Gene/Reaction Essentiality Analysis: Identifies critical metabolic genes or reactions whose deletion disrupts specific biological functions [1].

- Synthetic Lethality Analysis (SLA): Discovers combinations of non-essential gene/reaction knockouts that become lethal when deleted together [1].

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Extends FBA to simulate time-dependent metabolic changes in dynamic environments [3].

- 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA): Integrates isotopic tracer data with constraint-based modeling to estimate intracellular metabolic fluxes [3].

These techniques have been instrumental in advancing both basic science and biotechnology applications, from identifying novel drug targets in pathogens to engineering industrial microbial strains for chemical production [1] [2].

Multi-Strain and Pan-Genome Analysis

The expansion of genomic data has enabled the development of multi-strain GEMs that capture metabolic diversity across different isolates of the same species. This approach involves creating:

- Core Models: Contain metabolic functions shared by all strains of a species [3].

- Pan-Models: Incorporate the union of metabolic capabilities across multiple strains [3].

Table 2: Representative Multi-Strain GEM Studies

| Organism | Number of Strains | Key Findings | Reference Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 55 | Identified core and strain-specific metabolic functions | Understanding metabolic diversity [3] |

| Salmonella strains | 410 | Predicted growth in 530 different environments | Phenotype prediction [3] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 64 | Analyzed growth under 300 different conditions | Pathogen metabolism [3] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 22 | Simulated growth on various nutrient sources | Metabolic versatility [3] |

| Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus | 6 | Revealed strain-specific host interactions | Plant pathogen studies [3] |

These multi-strain analyses provide insights into metabolic adaptations, niche specialization, and strain-specific virulence factors, with particular relevance for understanding pathogen ecology and evolution [3].

GEMs in Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Modeling Human Diseases

GEMs have become valuable tools for investigating the metabolic basis of human diseases, with applications spanning cancer, metabolic disorders, and infectious diseases [4] [2]. In cancer research, context-specific GEMs reconstructed from transcriptomic data of tumor samples have identified metabolic dependencies and potential drug targets in various cancer types [4]. For infectious diseases, GEMs of pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been used to simulate metabolic states under in vivo conditions, enabling the identification of essential metabolic functions that could serve as therapeutic targets [2].

The integration of GEMs with other data types has enabled several innovative approaches to disease research:

- Host-Pathogen Modeling: Combining GEMs of human cells and pathogens to study metabolic interactions during infection [2].

- Drug Targeting: Identifying essential metabolic reactions in pathogens that are absent in human hosts, enabling selective therapeutic development [2].

- Toxicology Studies: Predicting metabolic responses to pharmaceutical compounds and environmental toxins [1].

Applications in Systems Medicine

In systems medicine, GEMs facilitate the analysis of individual metabolic variations and their relationship to disease susceptibility and treatment response [1] [4]. The reconstruction of tissue-specific and cell-type-specific models has enabled researchers to investigate metabolic aspects of human physiology and pathology at unprecedented resolution [4]. For example, GEMs of human alveolar macrophages integrated with M. tuberculosis models have provided insights into host-pathogen interactions and potential intervention strategies [2].

The wealth of omics data generated by initiatives like the Human Microbiome Project (42 terabytes of data) and the Earth Microbiome Project (expected 15 terabytes of data) provides rich resources for constructing context-specific GEMs relevant to human health and disease [3]. These datasets, when integrated with GEMs, enable researchers to elucidate the metabolic basis of complex diseases and identify novel therapeutic strategies.

Critical Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for GEM Development and Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Tools | RAVEN, ModelSEED, CarveMe | Automated GEM reconstruction from genome annotations | Draft model generation [2] |

| Simulation Software | COBRA Toolbox, GEM Software | Flux balance analysis and constraint-based modeling | Metabolic flux prediction [1] [2] |

| Gene Essentiality Data | Keio Collection (E. coli), YEAS (Yeast) | Experimental validation of model predictions | Model validation [1] |

| Multi-omics Datasets | Transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics data | Context-specific model construction | Tissue/condition-specific modeling [3] [1] |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, BRENDA | Reaction and enzyme information | Network curation [1] |

| Strain Collections | Multi-strain isolates | Pan-genome analysis | Metabolic diversity studies [3] |

Specialized Analytical Frameworks

For advanced analysis of gene-environment interactions, specialized tools have been developed to handle the computational complexity of large-scale metabolic studies:

- GEM (Gene-Environment interaction analysis for Millions of samples): Software for efficient genome-wide interaction studies that can handle large sample sizes [5].

- REGEM (RE-analysis of GEM summary statistics): Enables re-analysis of summary statistics from a single multi-exposure genome-wide interaction study to derive analogous sets of summary statistics with arbitrary sets of exposures and interaction covariate adjustments [5].

- METAGEM (META-analysis of GEM summary statistics): Extends current fixed-effects meta-analysis models to incorporate multiple exposures from multiple studies, facilitating large-scale integrative analyses [5].

These tools help maximize the value of summary statistics from diverse and complex gene-environment interaction studies, enabling more powerful investigation of metabolic interactions in human populations [5].

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The field of genome-scale metabolic modeling continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future applications. The integration of machine learning approaches with GEMs represents a promising frontier, potentially enhancing predictive capabilities and enabling more efficient model reconstruction [3]. Similarly, the development of next-generation GEMs with expanded capabilities, including macromolecular expression and dynamic resolution, will provide more comprehensive representations of cellular physiology [3].

Community efforts toward model standardization and quality control are increasingly important as the number of published GEMs grows [2]. The establishment of consensus networks, such as the Yeast consensus model that resolved inconsistencies across different S. cerevisiae GEMs, provides a template for future collaborative model refinement [2]. As metabolic modeling continues to expand into new research areas, including microbial community modeling and host-microbiome interactions, GEMs will remain essential tools for translating genomic information into biological understanding with applications across biotechnology, medicine, and basic science [3] [2].

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, systematically connecting genomic information to metabolic phenotypes [2]. These models computationally describe gene-protein-reaction associations for an organism's entire metabolic genes, forming a knowledge base that can be simulated to predict metabolic fluxes for various systems-level studies [2]. The defining feature of GEMs is their ability to predict metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolic reactions occur—rather than merely describing static concentrations of biomolecules [6]. Since the first GEM for Haemophilus influenzae was reported in 1999, the scientific community has developed models for thousands of organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [2].

GEMs have become indispensable tools in systems biology, enabling researchers to move beyond descriptive genomics to predictive modeling of cellular behavior. By serving as a platform for integrating and analyzing various data types, including omics and kinetic data, GEMs provide context for interpreting experimental results and generating testable hypotheses [2]. Their applications span from strain development for industrial biotechnology and drug target identification in pathogens to understanding complex human diseases [3] [2]. The mathematical foundation of GEMs allows researchers to perform in silico experiments that would be time-consuming, expensive, or technically challenging in the laboratory, accelerating the pace of biological discovery and biotechnological innovation.

Core Components of a GEM

Fundamental Building Blocks

The structure of a genome-scale metabolic model is built upon four interconnected core components that form the foundation of all subsequent simulations and predictions.

Genes: In GEMs, genes represent the genetic potential of an organism to perform metabolic functions. The model includes open reading frames associated with metabolic enzymes, transporters, and other metabolic functions. As of 2019, GEMs have been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms (5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryotes) [2]. The first E. coli GEM, iJE660, contained information on 660 genes, while recent versions like iML1515 have expanded to include 1,515 genes, demonstrating how improved annotations have steadily increased gene coverage [2].

Proteins: Proteins are the functional executants of metabolic processes, primarily enzymes that catalyze biochemical reactions. GEMs represent the connection between genes and proteins through gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations [7]. These associations define the complex relationships where a single functional role can be involved in multiple enzyme complexes, and multiple functional roles can constitute a single enzyme complex [7]. For example, the "Ubiquinol-cytochrome C complex" requires ten different functional roles each encoded by separate genes [7].

Reactions: Reactions form the functional core of a GEM, representing biochemical transformations, transport processes, or exchange mechanisms. Each reaction is represented as a stoichiometric equation with substrates and products. The latest human GEM, Human1, contains 13,417 reactions after extensive curation removed 8,185 duplicated reactions [6]. Reactions are categorized into subsystems that represent specific metabolic pathways or functional modules, enabling organized analysis of metabolic capabilities.

Metabolites: Metabolites are the chemical compounds that participate in biochemical reactions, serving as substrates, products, or intermediates. In GEMs, metabolites are tracked with their formulas, charges, and compartmental localization. Human1 includes 10,138 metabolites (4,164 unique after removing duplicates), with extensive curation to ensure mass and charge balance [6]. Standardized identifiers from databases like KEGG, MetaCyc, and ChEBI facilitate integration with external resources and comparison across models.

The Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association

The GPR association forms the critical link between an organism's genotype and its metabolic phenotype, creating a logical bridge between genomics and metabolism [7]. These associations follow Boolean logic rules that define which gene products are necessary for a reaction to occur.

The relationships within GPRs can be complex:

- One-to-one: A single gene encodes a protein that catalyzes a reaction (e.g., "Alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1)" encoded by the phoA gene in E. coli) [7].

- One-to-many: A single functional role participates in multiple enzyme complexes (e.g., "Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase of PTS system (EC 2.7.3.9)" encoded by ptsI is involved in importing different sugars) [7].

- Many-to-one: Multiple proteins form an enzyme complex required for a single reaction (e.g., the Ubiquinol-cytochrome C complex requires ten different functional roles) [7].

Diagram 1: Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations showing how multiple genes encode proteins that form enzyme complexes to catalyze metabolic reactions.

Quantitative Composition of GEMs

Model Statistics Across Organisms

The scale and complexity of GEMs vary significantly across organisms, reflecting their biological complexity and the extent of research investment. The table below summarizes the quantitative composition of representative high-quality GEMs from different taxonomic groups.

Table 1: Quantitative composition of representative genome-scale metabolic models across different organisms

| Organism | Model Name | Reactions | Metabolites | Genes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens (Human) | Human1 | 13,417 | 10,138 (4,164 unique) | 3,625 | [6] |

| Escherichia coli | iML1515 | 2,712 | 1,872 | 1,515 | [2] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) | Yeast 7 | 1,845 | 1,207 | 911 | [2] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | iEK1101 | 1,101 | 829 | 737 | [2] |

| Bacillus subtilis | iBsu1144 | 1,447 | 1,044 | 1,144 | [2] |

| Methanosarcina acetivorans (Archaea) | iMAC868 | 868 | 747 | 868 | [2] |

Quality Metrics for Model Evaluation

As GEMs have evolved, so have the standards for evaluating their quality and comprehensiveness. The Memote framework provides a standardized set of tests and metrics for assessing GEMs [6]. For the Human1 model, key quality metrics demonstrate substantial improvements over previous iterations:

- Stoichiometric consistency: 100% in Human1 compared to 19.8% in Recon3D [6]

- Mass-balanced reactions: 99.4% in Human1 compared to 94.2% in Recon3D [6]

- Charge-balanced reactions: 98.2% in Human1 compared to 95.8% in Recon3D [6]

- Annotation score: Average of 66% for metabolites, reactions, genes, and SBO terms, substantially improved from 25% for Recon3D [6]

Additional quality indicators include the percentage of reactions and metabolites mapped to standard identifiers (88.1% and 92.4% respectively in Human1), which facilitates integration with external databases and comparison across models [6].

Mathematical Framework and Simulation

The Stoichiometric Matrix

The core mathematical structure of a GEM is the stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows represent metabolites, columns represent reactions, and entries are stoichiometric coefficients [8]. This matrix quantitatively defines the metabolic network topology, encoding all possible biochemical transformations within the organism.

The steady-state assumption is fundamental to most GEM simulations, expressed mathematically as S · v = 0, where v is the flux vector representing reaction rates [8]. This equation states that the production and consumption of each internal metabolite must balance, implying that internal metabolite concentrations remain constant over time. This steady-state approximation is valid for many physiological conditions where metabolic processes operate at pseudo-steady state.

Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most widely used method for simulating GEMs [9] [8]. FBA uses linear programming to predict the flow of metabolites through the metabolic network, optimizing an objective function subject to constraints. The general FBA formulation is:

Maximize: c^T · v Subject to: S · v = 0 and: vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Where c is a vector defining the objective function (typically biomass production for microbial growth), and vmin and vmax represent lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes [7].

Table 2: Common constraints used in Flux Balance Analysis

| Constraint Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Constraints | Defined by the S matrix; ensures mass balance of metabolites | S · v = 0 |

| Capacity Constraints | Physicochemical and enzyme capacity limitations | vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax |

| Environmental Constraints | Nutrient availability in growth medium | Glucose uptake < 10 mmol/gDW/h |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | Directionality of reactions based on energy considerations | Irreversible reactions constrained to v ≥ 0 |

| Regulatory Constraints | Additional limitations from gene regulation | Reaction fluxes set to zero when regulating gene is knocked out |

FBA has proven remarkably effective in predicting microbial growth rates, substrate uptake rates, byproduct secretion, and the outcomes of gene knockouts [7]. The success of FBA stems from the evolutionary optimization of metabolic networks for growth and energy production, making biomass optimization a reasonable objective function for many microorganisms.

Construction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

The Model Reconstruction Pipeline

Building a high-quality GEM is a multi-step process that transforms genomic information into a predictive mathematical model. The reconstruction pipeline involves both automated and manual curation steps to ensure biological accuracy.

Diagram 2: Workflow for reconstructing genome-scale metabolic models from genomic data.

The reconstruction process begins with genome annotation using tools like RAST, PROKKA, or BG7 to identify protein-encoding genes and assign functional roles [7]. These functional roles are then connected to enzyme complexes and subsequently to biochemical reactions using databases like Model SEED, KEGG, or MetaCyc [7]. The collected reactions are assembled into a network, with particular attention to transport reactions (moving metabolites between cellular compartments) and exchange reactions (defining which metabolites can enter or leave the system).

A critical component is the biomass reaction, which defines the stoichiometric composition of macromolecules (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, DNA, RNA) required for cellular growth [6]. For Human1, a new generic human biomass reaction was constructed based on various tissue and cell composition data sources [6]. The final steps involve extensive manual curation to resolve gaps, inconsistencies, and thermodynamic infeasibilities, followed by model validation using experimental data on growth capabilities, gene essentiality, and substrate utilization patterns.

Tools and Databases for GEM Reconstruction

Table 3: Essential tools, databases, and resources for GEM reconstruction and analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Reference/URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAST | Annotation Pipeline | Identifies protein-encoding genes and assigns functional roles | [7] |

| Model SEED | Biochemistry Database | Connects functional roles to enzymes and reactions | [7] |

| KEGG | Metabolic Pathway Database | Reference metabolic pathways and reaction information | [8] |

| PyFBA | Software Package | Python-based platform for building metabolic models and running FBA | [7] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | [8] |

| COBRApy | Software Package | Python implementation of COBRA methods | [8] |

| Memote | Quality Assessment | Standardized test suite for evaluating GEM quality | [6] |

| MetaNetX | Resource Integration | Database for mapping model components to standard identifiers | [6] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Context-Specific Models and Multi-Omics Integration

While global GEMs represent the metabolic potential of an organism, context-specific models capture the metabolic state of particular cell types, tissues, or conditions by removing inactive reactions based on omics data [10]. These models are generated by integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomic data to create a condition-specific subset of the global metabolic network.

A recent study demonstrated the power of this approach by constructing SNP-specific GEMs using gene expression data from a yeast allele replacement panel during sporulation [10]. The researchers identified how SNP-SNP interactions impact the connectivity of metabolic regulators and alter flux through key pathways including glycolysis, steroid biosynthesis, and amino acid metabolism [10]. This study exemplifies how GEMs can bridge the gap between genetic variation and metabolic phenotype, revealing that autophagy acts as a pentose pathway-dependent compensatory mechanism supplying critical precursors like nucleotides and amino acids to enhance sporulation [10].

Emerging Frontiers in Metabolic Modeling

GEM applications continue to expand into new research areas. Multi-strain metabolic models have been developed to understand metabolic diversity within species, such as the 55 individual E. coli GEMs used to create core and pan-metabolic models [3]. Host-microbiome models integrate GEMs of human metabolism with models of microbial species to study metabolic interactions in health and disease [3]. The Human Microbiome Project has generated terabytes of data that can be contextualized using GEMs to understand how niche microbiota affect their hosts [3].

Methodological advances continue to enhance GEM capabilities. Enzyme-constrained models (ecGEMs) incorporate kinetic parameters and enzyme abundance data to improve flux predictions [6]. Dynamic FBA extends the steady-state assumption to simulate time-dependent metabolic changes [3]. Machine learning approaches are being integrated with GEMs to identify patterns in high-dimensional omics data and generate novel biological insights [3].

Community-driven development platforms like Metabolic Atlas provide interactive web portals for exploring metabolic networks, visualizing omics data on metabolic maps, and facilitating collaborative model improvement [6]. The use of version-controlled repositories like GitHub for model development, as demonstrated with Human1, represents a paradigm shift toward more transparent, reproducible, and community-engaged metabolic modeling [6].

Genome-scale metabolic models represent a powerful synthesis of genomic knowledge and computational methods, transforming how researchers investigate and manipulate cellular metabolism. The structured organization of genes, proteins, reactions, and metabolites within a mathematical framework enables quantitative prediction of metabolic behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions. As reconstruction methods become more sophisticated and omics data more abundant, GEMs will continue to expand their applications in basic research, biotechnology, and medicine. The ongoing development of community standards, version-controlled repositories, and interactive exploration platforms ensures that GEMs will remain at the forefront of systems biology, providing increasingly accurate models to guide scientific discovery and engineering applications.

The field of systems biology was fundamentally reshaped by a pivotal achievement in 1995: the completion of the first entire genome sequence of a free-living organism, Haemophilus influenzae [11]. This Gram-negative bacterium, once incorrectly believed to cause influenza, became the foundational template for computational modeling of biological systems [11] [2]. The sequencing breakthrough, accomplished by Craig Venter and his team using whole-genome shotgun sequencing, provided the essential parts list of 1,830,138 base pairs and 1,740 genes required to reconstruct its complete metabolic network [11] [2]. This historical milestone marked the genesis of genome-scale metabolic modeling, a discipline that has since expanded to encompass thousands of organisms across all domains of life, transforming how researchers investigate metabolism, engineer strains for biotechnology, identify drug targets, and understand human disease [3] [2].

H. influenzae served as an ideal candidate for this pioneering work due to its relatively small genome and the extensive biochemical knowledge accumulated from decades of study as a significant human pathogen [11] [12]. Prior to its genome sequencing, H. influenzae type b (Hib) was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis and other invasive diseases in children younger than five years, driving substantial research into its biology and pathogenesis [12] [13]. The successful sequencing project, published in Science, demonstrated the feasibility of whole-genome shotgun sequencing and established the methodological framework for subsequent genome projects, including the human genome [11].

Historical Context and Biological Significance ofH. influenzae

Historical Landmarks and Misidentification

The history of Haemophilus influenzae is characterized by initial misidentification and subsequent scientific clarification. First described in 1892 by Richard Pfeiffer during an influenza pandemic, the bacterium was incorrectly identified as the causative agent of influenza, leading to its misleading name [11] [12] [13]. This misattribution persisted until 1933, when the influenza virus was definitively established as the true etiological agent, with H. influenzae functioning primarily as a cause of secondary infection [12]. In the 1930s, Margaret Pittman's seminal work demonstrated that H. influenzae existed in both encapsulated (typeable) and unencapsulated (nontypeable) forms, with virtually all isolates from cerebrospinal fluid and blood belonging to capsular type b [12]. This distinction proved critical for understanding the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Hib disease.

Clinical Impact in the Pre-Vaccine Era

Before the introduction of effective conjugate vaccines, Hib represented a devastating public health threat, particularly affecting young children. In the pre-vaccine era, approximately one in 200 children developed invasive Hib disease by age five, with up to 60% of cases occurring before 12 months of age [12]. The most common manifestation was meningitis, accounting for 50-65% of invasive cases, with case fatality ratios of 3-6% despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy [12]. Neurological sequelae, including hearing impairment and developmental delays, affected 15-30% of survivors [12] [13]. Globally, prior to vaccine introduction in resource-poor countries, H. influenzae was responsible for an estimated 8.13 million illnesses and 371,000 deaths in children under five years of age in 2000 alone, predominantly attributable to serotype b [14].

Table 1: Historical Impact of Haemophilus influenzae Type b in the Pre-Vaccine Era

| Aspect | Pre-Vaccine Statistics | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 20-50/100,000 in industrialized countries [15] | Major cause of childhood mortality and morbidity |

| Peak Age Susceptibility | 6-11 months [12] | Reflected the gap between loss of maternal antibodies and acquisition of natural immunity |

| Most Common Disease | Meningitis (50-65% of invasive cases) [12] | Leading cause of bacterial meningitis in young children |

| Case Fatality Ratio | 3-6% for meningitis [12] | Significant mortality despite antibiotic therapy |

| Neurological Sequelae | 15-30% of meningitis survivors [12] [13] | Long-term disability including hearing impairment and developmental delays |

| Global Burden (2000) | 8.13 million illnesses, 371,000 deaths in children <5 [14] | Highlighted disproportionate impact in developing countries |

Microbiological Characteristics and Pathogenesis

H. influenzae is a small, Gram-negative, pleomorphic coccobacillus that requires specific growth factors present in blood: hemin (X factor) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (V factor) [11] [12] [16]. Its classification includes six encapsulated serotypes (a-f) and non-typeable strains (NTHi) that lack a polysaccharide capsule [11] [12]. The type b capsule, composed of polyribosyl-ribitol-phosphate (PRP), served as the critical virulence factor enabling invasive disease and became the target for conjugate vaccine development [12].

The pathogenesis of H. influenzae begins with colonization of the nasopharynx, followed in susceptible individuals by invasion of the bloodstream and dissemination to distant sites [12]. Non-typeable strains primarily cause mucosal infections such as otitis media, sinusitis, and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) through local invasion rather than bloodstream dissemination [16]. The bacterium employs various adhesins, including pili, Hia, and Hap proteins, to attach to host epithelial cells, and can form biofilms that contribute to chronicity and antibiotic resistance [11] [16].

The Genesis of Genome Sequencing and Metabolic Modeling

First Whole-Genome Sequencing Breakthrough

The sequencing of the H. influenzae Rd KW20 strain in 1995 represented a methodological revolution in genomics. Prior to this achievement, sequencing efforts had focused on smaller viral or organellar genomes. The H. influenzae project, led by Craig Venter and Hamilton Smith at The Institute for Genomic Research, demonstrated for the first time that whole-genome shotgun sequencing could be successfully applied to a complete bacterial genome [11] [2]. This approach involved fragmenting the genome into random pieces, cloning and sequencing these fragments, and then using sophisticated algorithms to assemble the sequences based on overlapping regions.

The completed genome sequence revealed a circular chromosome containing 1,830,138 base pairs encoding 1,604 protein-coding genes, 117 pseudogenes, 57 tRNA genes, and 23 other RNA genes [11]. Comparative genomics showed approximately 90% of the genes had homologs in E. coli, another gamma-proteobacterium, with protein sequence identity ranging from 18% to 98% (averaging 59%) [11]. This genetic conservation provided early insights into evolutionary relationships between bacterial species while highlighting species-specific adaptations.

From Genome Sequence to the First Metabolic Model

The availability of the complete genome sequence enabled the reconstruction of the first genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for H. influenzae in 1999, just four years after its sequencing [2]. This foundational model compiled all known metabolic reactions, their associated genes, and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules into a structured knowledge base that could be mathematically simulated [2]. The reconstruction process involved:

- Genome Annotation: Identifying genes encoding metabolic enzymes through homology searches and functional prediction [2].

- Reaction Network Assembly: Mapping the annotated genes to known metabolic reactions based on biochemical literature and databases [8].

- Stoichiometric Matrix Formulation: Representing the metabolic network as a mathematical matrix where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent reactions [8].

- Constraint Definition: Incorporating physiological constraints such as substrate uptake rates and energy requirements [2] [8].

The resulting model provided a computational representation of H. influenzae metabolism that could predict metabolic fluxes under different environmental conditions and genetic perturbations [2].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of the First Haemophilus influenzae Genome and Initial Metabolic Model

| Characteristic | H. influenzae Rd KW20 | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | 1,830,138 base pairs [11] | First complete genome sequence of a free-living organism |

| Chromosome Structure | Single, circular chromosome [11] | Established standard for bacterial genome organization |

| Protein-Coding Genes | 1,604 genes [11] | Provided the first complete set of genes for an organism |

| Metabolic Model | Reconstructed in 1999 [2] | First genome-scale metabolic model of any organism |

| Modeling Approach | Flux Balance Analysis [2] | Enabled prediction of metabolic capabilities from genomic data |

| Homology with E. coli | ~90% of genes have homologs [11] | Revealed evolutionary conservation despite phenotypic differences |

Methodology: Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction and Simulation

Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction Workflow

The reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models follows a systematic workflow that transforms genomic information into a mathematical representation of cellular metabolism. The standard pipeline includes:

- Draft Reconstruction: Automatic generation of an initial model from genome annotation using tools that query biochemical databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc) [3] [8].

- Network Refinement: Manual curation to fill knowledge gaps, remove incorrect annotations, and add organism-specific metabolic capabilities based on experimental literature [2].

- Biomass Composition: Definition of the biosynthetic requirements for cellular growth, including amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and cofactors [2] [8].

- GPR Association Formalization: Establishment of logical relationships between genes, their protein products, and the metabolic reactions they catalyze [2] [8].

- Model Validation: Testing model predictions against experimental data on growth capabilities, gene essentiality, substrate utilization, and byproduct secretion [2].

This iterative process produces a stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) where each element Sij represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. This mathematical formulation enables constraint-based modeling approaches [8].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Principles

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the primary computational method for simulating genome-scale metabolic models. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling prediction of growth rates, nutrient uptake, byproduct secretion, and gene essentiality [9] [8]. The methodology involves:

- Stoichiometric Constraints: Applying mass balance constraints such that for each metabolite, the sum of production fluxes equals the sum of consumption fluxes at metabolic steady state [8].

- Capacity Constraints: Defining upper and lower bounds for reaction fluxes based on enzyme capacities and thermodynamic feasibility [2] [8].

- Objective Function: Identifying an optimal flux distribution by maximizing or minimizing a biological objective, typically biomass production as a proxy for cellular growth [2] [8].

- Linear Programming: Solving the resulting system of linear equations using optimization algorithms to determine the flux through each reaction [8].

The mathematical formulation can be represented as:

Maximize Z = cᵀv Subject to: Sv = 0 and vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Where Z is the objective function, c is a vector of weights, v is the flux vector, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and vmin/vmax are flux bounds [8].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Experimental validation of metabolic model predictions employs several well-established protocols:

1. Gene Essentiality Profiling:

- Method: Systematic knockout of metabolic genes using homologous recombination or transposon mutagenesis [2].

- Growth Conditions: Testing mutant strains in minimal and rich media with different carbon sources [2].

- Validation Metric: Comparing predicted essential genes with experimental viability data [2].

2. Substrate Utilization Assays:

- Culture Conditions: Growing wild-type strains in defined minimal media with single carbon sources [2].

- Growth Measurements: Monitoring optical density (OD600) over time to determine growth rates [2].

- Comparison: Correlating experimental growth capabilities with model predictions [2].

3. ¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA):

- Isotope Labeling: Using ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose, acetate) to track metabolic fluxes [3].

- Mass Spectrometry: Measuring isotopic labeling patterns in proteinogenic amino acids or central metabolites [3].

- Flux Estimation: Computational inference of intracellular fluxes from labeling data [3].

4. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Integration:

- Data Collection: Measuring gene expression (RNA-seq) or protein abundance (mass spectrometry) under different conditions [3] [2].

- Model Contextualization: Creating condition-specific models using expression data as constraints [2].

- Prediction Accuracy: Assessing whether integrated models show improved phenotypic predictions [2].

Expansion to Thousands of Organisms: Current Status and Applications

Quantitative Expansion Across Biological Domains

Since the initial reconstruction of the H. influenzae GEM, the field has experienced exponential growth in both model quantity and complexity. As of February 2019, GEMs have been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms across all domains of life, including 5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryotes [2]. This expansive coverage enables comparative studies of metabolic evolution, niche adaptation, and phylogenetic conservation of metabolic pathways. The growth trajectory of available GEMs demonstrates the increasing accessibility of genomic data and computational reconstruction tools, with particular emphasis on scientifically, industrially, and medically important organisms.

Table 3: Current Status of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models Across Biological Domains

| Domain | Number of Organisms with GEMs | Representative Organisms | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 5,897 [2] | Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis [2] | Metabolic engineering, antibiotic targeting, biotechnology |

| Archaea | 127 [2] | Methanosarcina acetivorans, Methanobacterium formicicum [3] [2] | Understanding extremophile metabolism, methane production |

| Eukarya | 215 [2] | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Homo sapiens, Arabidopsis thaliana [2] | Bioproduction, disease modeling, plant metabolism |

Multi-Strain Models and Pan-Reactome Analysis

The expansion beyond single reference strains to multi-strain metabolic models represents a significant advancement in GEM capabilities. Pan-genome analysis, which examines the full complement of genes across multiple strains of a species, has been extended to metabolic networks through pan-reactome analysis [3]. This approach involves:

- Core-Pan Model Construction: Creating a "core" model containing metabolic reactions shared by all strains and a "pan" model encompassing the union of all reactions across strains [3].

- Strain-Specific Simulations: Predicting growth capabilities and metabolic phenotypes for individual strains in various environments [3].

- Metabolic Diversity Assessment: Identifying strain-specific metabolic capabilities that may correlate with virulence, niche specialization, or biotechnological potential [3].

Notable examples include multi-strain models of E. coli (55 strains), Salmonella (410 strains), Staphylococcus aureus (64 strains), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (22 strains) [3]. These models have revealed substantial metabolic diversity even within closely related strains, with implications for understanding pathogenesis and designing broad-spectrum therapeutic interventions.

Advanced Applications in Research and Industry

Contemporary applications of GEMs extend far beyond their original use for metabolic prediction, spanning diverse fields from biotechnology to medicine:

1. Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design:

- Objective: Engineering microorganisms for high-value chemical production [3] [2].

- Methodology: Using GEMs to identify gene knockout, overexpression, or insertion targets that optimize product yield while maintaining growth [2].

- Examples: Production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and specialty chemicals in E. coli and S. cerevisiae [2].

2. Drug Target Identification in Pathogens:

- Objective: Discovering essential metabolic reactions as potential antibiotic targets [3] [2].

- Methodology: Simulating gene essentiality in pathogen GEMs under host-like conditions [2].

- Examples: Identification of targets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other ESKAPEE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp., and E. coli) [3] [2].

3. Host-Microbe Interaction Modeling:

- Objective: Understanding metabolic interactions between hosts and their associated microbiota [3] [2].

- Methodology: Integrating GEMs of host cells and microbes to simulate metabolite exchange [2].

- Examples: Integrated models of M. tuberculosis with human alveolar macrophages [2].

4. Disease Mechanism Elucidation:

- Objective: Understanding metabolic aspects of human diseases [3] [2].

- Methodology: Building cell-type specific GEMs using transcriptomic data from diseased tissues [2].

- Examples: Cancer metabolism models, metabolic disorders [2].

5. Enzyme Function Prediction:

- Objective: Annotating genes of unknown function [2].

- Methodology: Using gap-filling algorithms to identify missing metabolic functions in GEMs [2].

- Examples: Discovery of previously unknown metabolic enzymes and pathways [2].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [8] | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | FBA simulation, model validation, gap filling |

| COBRApy [8] | Python implementation of COBRA methods | Scriptable metabolic modeling, integration with data science workflows |

| ModelSEED [3] | Web-based resource for automated model reconstruction | Draft model generation from genome annotations |

| RAVEN Toolbox [3] | MATLAB-based suite for network reconstruction and analysis | KEGG-based reconstruction, comparative genomics |

| CarveMe [3] | Automated model reconstruction from genome annotation | Rapid generation of species-specific models |

| AGORA [3] | Resource of curated GEMs for gut microbiota | Host-microbiome interaction studies |

| BiGG Models [2] | Knowledgebase of curated metabolic models | Model comparison, reaction database |

| KEGG [8] | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes | Pathway information, enzyme nomenclature |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Directions

The future of genome-scale metabolic modeling is evolving toward increased integration, dynamism, and multi-scale resolution. Several emerging areas are particularly promising:

1. Integration of Macromolecular Expression (ME-Models): Next-generation models explicitly incorporate protein synthesis and catalytic constraints, moving beyond purely metabolic networks to include proteomic limitations on cellular growth [3].

2. Dynamic and Spatial Modeling: Current FBA approaches assume metabolic steady-state, but new methods incorporating kinetic parameters and spatial compartmentalization are enabling dynamic simulations of metabolic responses to changing environments [3].

3. Machine Learning Integration: Combining GEM predictions with machine learning algorithms enhances pattern recognition from large omics datasets and improves prediction of complex phenotypes that cannot be captured by metabolic constraints alone [3].

4. Community and Ecosystem Modeling: Scaling from individual organisms to microbial communities represents a frontier in metabolic modeling, with potential applications in understanding human microbiomes, environmental ecosystems, and industrial consortia [3] [2].

5. Clinical and Therapeutic Applications: Patient-specific metabolic models derived from genomic and metabolomic data hold promise for personalized medicine applications, including tailored nutritional interventions and cancer therapies [2].

The progression from a single H. influenzae model to thousands of organism-specific GEMs demonstrates how foundational biological resources can catalyze an entire research field. As modeling frameworks continue to incorporate additional cellular processes and data types, genome-scale models will remain essential tools for bridging genomic information and phenotypic expression across the tree of life.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the biochemical reaction networks occurring within an organism. These models link genomic information to metabolic capabilities, providing a framework for predicting phenotypic behavior from genotypic data [17]. By representing the entire metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix, GEMs enable the application of constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, notably Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), to predict metabolic fluxes, substrate utilization, growth rates, and essential genes [17] [18]. The reconstruction of high-quality, organism-specific GEMs is a critical first step in metabolic engineering, enabling the rational design of microbial cell factories, investigating host-pathogen interactions, and understanding disease mechanisms [19] [20].

The value of GEMs is profoundly amplified when they are developed for well-characterized model organisms. Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Homo sapiens represent three pillars of biological research whose reference metabolic models serve as foundational tools and community standards. These curated models provide a platform for integrating multi-omic data, testing biological hypotheses in silico, and facilitating comparative systems biology [19]. This guide details the premier metabolic models for these key organisms, their applications, and the experimental methodologies used for their validation, providing an essential resource for researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Reference Models for Key Organisms

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) Models

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a fundamental model for eukaryotic biology and a critical workhorse in industrial biotechnology. Its metabolic models have evolved significantly in complexity and predictive power.

Table 1: Evolution of High-Quality Yeast Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Model Name | Reactions | Metabolites | Genes | Key Features and Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iFF708 [21] | 1,175 | - | 708 | Early model; many lipid metabolism reactions were lumped or missing. |

| iND750 [21] | 1,498 | - | 750 | Fully compartmentalized; validated with large-scale gene deletion data. |

| iLL672 [21] | 1,038 | - | 672 | Derived from iFF708; improved accuracy for single-gene deletion predictions. |

| iIN800 [21] | 1,446 | 1,013 | ~800 | Incorporated detailed lipid metabolism; new biomass equations; validated with 13C-labeling. |

| Yeast8 [22] | 3,991 | 2,691 | 1,149 | Includes 14 compartments; 2,614 gene-associated reactions. |

| yETFL [22] | - | - | 1,393* | Integrates expression constraints & thermodynamics; includes metabolic (1,149) + expression (244) genes. |

The yETFL model represents a paradigm shift, moving beyond traditional metabolic networks. It is a Metabolism and Expression (ME-) model that efficiently integrates RNA and protein synthesis with the metabolic network of Yeast8 [22]. Key innovations include the incorporation of thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible solutions and the explicit modeling of the compartmentalized eukaryotic expression machinery, including mitochondrial and nuclear ribosomes and RNA polymerases [22]. This allows yETFL to predict maximum growth rate, essential genes, and the phenomenon of overflow metabolism with high accuracy.

Homo sapiens (Human) Models

Human genome-scale metabolic models are crucial for understanding human physiology, disease states, and host-microbiome interactions, particularly in the context of drug development.

Table 2: Applications of Human Metabolic Models in Biomedical Research

| Application Area | Specific Use-Case | Model/Approach | Findings/Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) [20] | Screening for therapeutic strains against pathogenic E. coli. | AGORA2 (7302 GEMs of gut microbes) | Identified Bifidobacterium breve and B. animalis as promising candidates. |

| Personalized Medicine [20] | Designing multi-strain LBP formulations. | AGORA2 & strain-specific GEMs | Enables in silico prediction of strain interactions and metabolite exchange for precise formulations. |

| Toxicology & Safety [20] | Assessing LBP candidate safety. | GEMs of therapeutic strains | Predicts potential for detrimental metabolite production and drug-metabolite interactions. |

| Antimicrobial Pharmacology [23] | Deciphering microbial & host responses to drugs. | Tissue & cell-type specific GEMs | Elucidates mechanisms of drug action, resistance pathways, and off-target effects. |

The AGORA2 resource, which contains manually curated, strain-level GEMs for 7,302 human gut microbes, is a prime example of the scale and precision now possible in human metabolic modeling [20]. These models are used to simulate the metabolic interactions between the host, gut microbiota, and therapeutic interventions, providing a systems-level perspective that is revolutionizing the development of microbiome-based therapeutics [23] [20].

Escherichia coli Models

Escherichia coli is one of the most extensively studied model organisms, and its metabolic models are among the most advanced and widely used. The original ETFL formulation, which laid the groundwork for the yeast yETFL model, was developed for E. coli [22]. This framework set the standard for integrating metabolic networks with expression constraints. Furthermore, high-throughput tools like Bactabolize, while demonstrated on Klebsiella pneumoniae, exemplify the methodology for rapid, reference-based generation of strain-specific models that can be directly applied to E. coli studies [17]. These approaches rely on a pan-genome reference model and can produce draft models in under three minutes per genome, enabling large-scale comparative analyses of metabolic diversity within a bacterial species [17].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

The predictive power of any genome-scale model is contingent upon rigorous experimental validation. The following protocols outline standard methodologies for validating model predictions.

Protocol 1: Validation of Predicted Substrate Utilization

This protocol tests in silico predictions of whether a model organism can utilize specific carbon sources for growth.

- In Silico Prediction: Use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). Constrain the model to a minimal medium, with the uptake of all carbon sources set to zero except for the single substrate being tested. Set the biomass reaction as the objective function. A predicted growth rate greater than zero indicates the substrate supports growth [17].

- Experimental Setup:

- Culture Conditions: Grow the organism in a defined minimal medium with the test substrate as the sole carbon source. Use a biological replicate of at least

n=3. - Inoculum: Standardize the inoculum density (e.g., OD600 = 0.05) to ensure consistent starting conditions.

- Controls: Include a positive control (a known growth substrate, e.g., glucose) and a negative control (no carbon source).

- Culture Conditions: Grow the organism in a defined minimal medium with the test substrate as the sole carbon source. Use a biological replicate of at least

- Growth Measurement: Monitor culture growth by measuring optical density (OD600) over time (e.g., 24-48 hours) using a plate reader or spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the maximum growth rate (μmax) for each substrate from the exponential phase of the growth curve. Compare experimental results with model predictions to calculate accuracy [17].

Protocol 2: Validation of Gene Essentiality Predictions

This protocol validates computational predictions of genes essential for growth under a specific condition.

- In Silico Prediction: Perform in silico single-gene deletion analysis using the model. For each gene, simulate growth by setting the flux through all reactions associated with that gene to zero. A predicted growth rate of zero indicates an essential gene [21] [22].

- Experimental Validation via Gene Knockout:

- Strain Construction: Create a knockout mutant for each gene predicted to be essential, using homologous recombination or CRISPR-Cas9.

- Growth Assay: Attempt to culture the knockout strain on solid and in liquid minimal medium under the same conditions used for the in silico prediction.

- Essentiality Scoring: A gene is confirmed experimentally essential if the knockout mutant cannot grow, while the wild-type strain can.

- Data Analysis: Compare the list of predicted essential genes with the experimentally confirmed ones to determine the true positive rate and model accuracy [21].

Protocol 3: Validation of Metabolic Fluxes using 13C-Labeling

This protocol uses isotopic tracers to validate internal metabolic flux distributions predicted by the model.

- In Silico Flux Prediction: Perform FBA or related techniques (e.g., parsimonious FBA) to predict the intracellular flux distribution for the given growth condition.

- Experimental 13C-Labeling:

- Tracer Preparation: Use a 13C-labeled carbon source (e.g., [1-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glucose) in the growth medium.

- Cultivation: Grow the organism in a controlled bioreactor with the labeled substrate until metabolic steady state is reached.

- Metabolite Extraction: Quench metabolism rapidly and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the extract using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) to measure the mass isotopomer distributions of key intermediate metabolites.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational software to infer the actual intracellular metabolic fluxes that best fit the measured mass isotopomer distribution data.

- Model Validation: Compare the model-predicted fluxes with the experimentally inferred fluxes. Statistical correlation (e.g., R² value) between the two sets of fluxes validates the model's predictive capability [21].

Visualization of Model Reconstruction and Workflow

The process of building and utilizing a high-quality genome-scale metabolic model follows a structured workflow, from initial reconstruction to final validation and application.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bactabolize | Command-line tool for draft model generation | High-throughput; uses species-specific reference model; rapid (≈3 min/model). | [17] |

| Model SEED | Web-based high-throughput modeling | Automated reconstruction from genome sequence; integrates gap-filling. | [19] [24] |

| CarveMe | Command-line tool for draft model generation | Uses a universal biochemical database; fast. | [17] |

| gapseq | Command-line tool for draft model generation | Leverages an independent universal database; reported high accuracy. | [17] |

| AGORA2 | Database of curated metabolic models | 7,302 manually curated GEMs of human gut microbes. | [20] |

| COBRApy | Python library for constraint-based modeling | Core software library for simulation and analysis (used by Bactabolize). | [17] |

| SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) | Data format standard | Common format for representing and exchanging models. | [19] |

| BiGG Models | Database of curated metabolic models | Mass- and charge-balanced models with standardized nomenclature. | [17] [19] |

| MOST | Software for strain design | Intuitive interface for FBA and genetic design algorithms (GDBB). | [25] |

| RAVEN Toolbox | MATLAB toolbox for metabolic modeling | Model reconstruction, simulation, and visualization. | [26] |

High-quality, reference metabolic models for E. coli, human, and yeast are indispensable resources in systems biology and metabolic engineering. The field is moving towards more complex and integrative models, such as yETFL for yeast, which capture not only metabolism but also the constraints of the expression machinery and thermodynamic laws [22]. Concurrently, the development of extensive, manually curated databases like AGORA2 for the human microbiome provides the resolution needed for personalized medicine applications [20]. As these tools and models continue to evolve, validated by robust experimental protocols, they will play an increasingly critical role in accelerating drug discovery, optimizing bioproduction, and deepening our understanding of fundamental biology.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as indispensable tools for systems biology, providing a computational framework to simulate an organism's metabolism at a systemic level. The construction, refinement, and application of high-quality GEMs are fundamentally dependent on comprehensive and curated biological databases. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of three critical resources—KEGG, MetaCyc, and AGORA2—that support metabolic modeling efforts. KEGG and MetaCyc serve as foundational knowledge bases of metabolic pathways and reactions, while AGORA2 represents a pioneering application of this knowledge, providing ready-to-use, manually curated GEMs for thousands of human-associated microorganisms. Together, these resources enable researchers to decipher complex metabolic interactions in health and disease, accelerating advances in personalized medicine and therapeutic development [27] [20].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of KEGG, MetaCyc, and AGORA2

| Feature | KEGG | MetaCyc | AGORA2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Integrated knowledge base encompassing biological systems and chemicals [28] | Curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways [29] | Collection of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions of human microbes [27] |

| Content Type | Pathways, genomes, drugs, diseases | Pathways, reactions, enzymes, compounds | Strain-specific metabolic models, drug biotransformation reactions |

| Organism Scope | Broad across all domains of life | 3,443 different organisms [29] | 7,302 human microbial strains [27] |

| Curation Approach | Manually drawn pathway maps [28] | Literature-based manual curation [29] | Data-driven reconstruction refinement (DEMETER pipeline) [27] |

| Quantitative Content | 7 pathway categories [28] | 3,128 pathways, 18,819 reactions, 76,283 citations [29] | 7,302 strain reconstructions, 98 drugs with degradation capabilities [27] |

| Key Applications | Multi-omics data annotation and enrichment analysis [28] | Metabolic engineering, pathway prediction, metabolomics [29] [30] | Personalized modeling of host-microbiome interactions, drug metabolism prediction [27] |

Database-Specific Technical Profiles

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes)

KEGG is a versatile integrated database resource launched in 1995, consisting of approximately fifteen constituent databases categorized into systems information, genomic information, chemical information, and health information [28]. Its most recognized component, KEGG PATHWAY, contains manually drawn pathway maps representing current knowledge on molecular interactions and reaction networks. These pathways are organized into seven categories: Metabolism, Genetic Information Processing, Environmental Information Processing, Cellular Processes, Organismal Systems, Human Diseases, and Drug Development [28].

A critical feature of KEGG is its standardized identifier system and nomenclature. Pathways are encoded with 2-4 letter prefixes followed by five numbers (e.g., map00010 for glycolysis). In pathway maps, rectangular boxes represent enzymes, while circles represent metabolites [28]. This consistent visualization framework supports the interpretation of high-throughput data through color-coding schemes where, for example, differentially expressed genes can be marked red for up-regulation or green for down-regulation when mapped to KEGG pathways [28].

KEGG's structured data organization enables sophisticated computational analyses, particularly through enrichment analysis based on the hypergeometric distribution. This statistical approach identifies biologically significant pathways in omics datasets by comparing the frequency of specific genes or metabolites in a target dataset against background expectations [28]. The formula for this calculation is:

[ P = 1 - \sum_{i=0}^{m-1} \frac{\binom{M}{i} \binom{N-M}{n-i}}{\binom{N}{n}} ]

Where N is the total number of genes annotated to KEGG, n is the number of differentially expressed genes annotated to KEGG, M represents the number of genes annotated to a specific pathway, and m is the number of differentially expressed genes annotated to that pathway [28].

MetaCyc

MetaCyc is a member of the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases, distinguished by its multiorganism scope and exclusive focus on experimentally elucidated pathways [29]. Unlike many other resources that mix experimental data with computational predictions, MetaCyc serves as a curated reference database that captures the universe of metabolism by storing representative examples of each experimentally demonstrated metabolic pathway [29]. This rigorous curation philosophy makes it particularly valuable for applications requiring high-quality reference data.

The MetaCyc curation process involves extracting information through a step-wise process from primary literature, review articles, patent applications, and selected external databases [29]. For model organisms including Arabidopsis thaliana, Escherichia coli K-12, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, data are imported from authoritative sources including AraCyc, EcoCyc, and YeastCyc, respectively [29]. This meticulous approach ensures that MetaCyc provides reliable, evidence-based information across diverse biological domains.

MetaCyc supports multiple access methods to accommodate different use cases. The database is available through a web interface for interactive search and visualization, as downloadable flat files for local parsing and analysis, and through the Pathway Tools software which provides programmatic querying capabilities using Python, Java, Perl, and Lisp APIs [29]. This flexibility enables researchers to integrate MetaCyc data into diverse computational workflows for metabolic reconstruction, enzyme engineering, and metabolomics studies [29] [30].

AGORA2

AGORA2 (Assembly of Gut Organisms through Reconstruction and Analysis, version 2) represents a significant scaling of genome-scale metabolic reconstruction resources for human microorganisms, encompassing 7,302 strains spanning 1,738 species and 25 phyla [27]. This resource was developed through a substantially revised and expanded data-driven reconstruction refinement pipeline called DEMETER (Data-drivEn METabolic nEtwork Refinement), which integrates automated draft reconstruction with extensive manual curation [27].

A groundbreaking feature of AGORA2 is its inclusion of strain-resolved drug degradation and biotransformation capabilities for 98 drugs, capturing known microbial drug transformations with an accuracy of 0.81 [27]. This expansion enables researchers to investigate personalized variations in drug metabolism mediated by the gut microbiome, a crucial consideration for precision medicine. The resource has been extensively validated against three independently collected experimental datasets, achieving predictive accuracies between 0.72 and 0.84, surpassing other reconstruction resources [27].

AGORA2 reconstructions are fully compatible with both generic and organ-resolved, sex-specific whole-body human metabolic reconstructions, enabling integrated simulation of host-microbiome metabolic interactions [27]. This interoperability facilitates systems-level investigations of how microbial metabolism influences human physiology and pharmacology, particularly in the context of personalized differences in gut microbiome composition.

Table 2: AGORA2 Resource Specifications and Applications

| Attribute | Specification | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Strain Coverage | 7,302 strains, 1,738 species, 25 phyla [27] | Comprehensive representation of human gut microbial diversity |

| Drug Metabolism | 98 drugs with biotransformation reactions [27] | Prediction of personalized drug metabolism and microbiome-derived effects |

| Validation Performance | 0.81 accuracy for drug transformations; 0.72-0.84 against experimental datasets [27] | High-confidence predictions for translational applications |

| Technical Implementation | DEMETER refinement pipeline; manual curation of 446 gene functions [27] | Quality-assured reconstructions suitable for precision medicine |

| Integration Capability | Compatible with whole-body human metabolic models [27] | Holistic simulation of host-microbiome interactions |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Protocol for Metabolic Reconstruction Using Reference Databases

The construction of genome-scale metabolic models typically follows a multi-stage process that leverages databases like KEGG and MetaCyc as reference knowledge bases. A standardized protocol for this process involves:

Genome Annotation and Draft Reconstruction: Initial automated annotation of the target genome identifies metabolic genes and their putative functions. Draft reconstructions are generated using platforms like KBase, which reference pathway databases to propose metabolic capabilities [27].

Pathway Mapping and Gap-Filling: Predicted reactions are mapped to reference pathways in KEGG or MetaCyc to identify missing components and fill metabolic gaps. MetaCyc is particularly valuable for this purpose due to its experimental focus, providing evidence-based pathway templates that increase reconstruction accuracy [29].

Curation and Refinement: Manual curation is performed against biochemical literature and experimental data. For AGORA2, this involved manual validation of 446 gene functions across 35 metabolic subsystems for 74% of genomes using PubSEED, supplemented by literature searches spanning 732 peer-reviewed papers [27].

Stoichiometric Matrix Assembly and Testing: The curated reaction list is formalized into a stoichiometric matrix, and network properties are verified through flux consistency analysis. AGORA2 reconstructions showed significantly higher percentages of flux-consistent reactions compared to automated drafts (P < 1×10⁻³⁰, Wilcoxon rank-sum test) [27].

Biomass Reaction Formulation: Organism-specific biomass equations are constructed representing cellular composition, enabling simulation of growth phenotypes [27].

Model Validation: The resulting reconstruction is validated against experimental phenotyping data, such as substrate utilization capabilities or gene essentiality data. AGORA2 was validated against three independent experimental datasets with accuracy ranging from 0.72 to 0.84 [27].

Protocol for Personalized Drug Metabolism Prediction

AGORA2 enables strain-resolved prediction of microbial drug metabolism through the following methodological workflow:

Microbiome Profiling: Obtain strain-level microbial abundance data from metagenomic sequencing of an individual's gut microbiome.

Community Model Construction: Create a personalized microbiome model by integrating the AGORA2 reconstructions of detected strains, weighted by their relative abundance [27].

Drug Transformation Mapping: Identify potential drug metabolism capabilities by querying the community model for reactions associated with the 98 drugs encoded in AGORA2 [27].

Flux Balance Analysis: Simulate drug metabolism potential using constraint-based modeling approaches, applying nutritional constraints reflecting the host's dietary intake or gut environment.

Metabolite Exchange Prediction: Predict production of drug metabolites and their potential absorption or interaction with host metabolism.

Interindividual Comparison: Compare predictions across individuals to identify factors (age, BMI, disease status) correlating with variations in drug metabolism potential. In a demonstration, AGORA2 predicted substantial variation in drug conversion potential of gut microbiomes from 616 colorectal cancer patients and controls, correlating with age, sex, BMI and disease stage [27].

Implementation in Therapeutic Development

Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) Development Framework

AGORA2 serves as a cornerstone for model-guided development of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs), which are promising microbiome-based therapeutics. A systematic framework for LBP development leveraging metabolic models involves three key phases [20]:

In Silico Screening: Candidate strains are shortlisted through top-down or bottom-up approaches. Top-down screening isolates microbes from healthy donor microbiomes and characterizes their therapeutic potential using AGORA2 GEMs. Bottom-up approaches begin with predefined therapeutic objectives (e.g., restoring short-chain fatty acid production in inflammatory bowel disease) and identify compatible strains from AGORA2 that align with the intended mechanism [20].

Strain Evaluation: Shortlisted candidates undergo qualitative evaluation for quality, safety, and efficacy. Quality assessment focuses on metabolic activity, growth potential, and adaptation to gastrointestinal conditions. Safety evaluation addresses antibiotic resistance, drug interactions, and pathogenic potentials. Efficacy assessment predicts therapeutic metabolite production and host interaction capabilities [20].

Multi-Strain Formulation Design: Promising candidates are rationally combined into consortia based on metabolic complementarity. AGORA2 models simulate nutrient competition and cross-feeding to identify stable, synergistic strain combinations that maximize therapeutic output [20].

Diagram: GEM-guided framework for Live Biotherapeutic Product (LBP) development, integrating top-down and bottom-up screening approaches with multi-strain formulation design [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Metabolic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | KEGG [28], MetaCyc [29] | Provide curated metabolic pathways and reactions for model reconstruction and annotation |

| Model Reconstruction Tools | CarveMe [27], gapseq [27], Pathway Tools [29] | Generate draft genome-scale metabolic models from annotated genomes |

| Curated Model Resources | AGORA2 [27], BiGG [27] | Offer manually curated, ready-to-use metabolic reconstructions |