FBA Prediction Accuracy: Methods for Assessing Metabolic Model Reliability in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to assessing the accuracy of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

FBA Prediction Accuracy: Methods for Assessing Metabolic Model Reliability in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to assessing the accuracy of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental concepts that define FBA accuracy, detail current methodologies and their applications in biological discovery, address common challenges and optimization strategies, and evaluate comparative validation frameworks. The content synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower the reliable use of constraint-based metabolic models in systems biology and therapeutic development.

FBA Prediction Accuracy Fundamentals: Core Concepts and Defining Reliability Metrics

What is FBA Prediction Accuracy? Defining the Scope and Scientific Context

This whitepaper defines the scope and scientific context of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy. This topic is framed within a broader thesis dedicated to the systematic assessment and improvement of FBA prediction accuracy methodologies. FBA is a cornerstone mathematical approach in systems biology and metabolic engineering, used to predict organism behavior by calculating steady-state reaction fluxes within a constrained genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM). Its accuracy is paramount for applications ranging from microbial strain design for bioproduction to predicting essential genes in pathogens for drug target identification. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the sources, measurement, and limitations of this accuracy is critical for reliable translation of in silico predictions into in vivo or in vitro outcomes.

Defining FBA Prediction Accuracy

FBA prediction accuracy refers to the quantitative agreement between in silico flux predictions generated by an FBA simulation and experimentally measured phenotypic data. Accuracy is not a singular metric but is assessed across multiple prediction types, each with distinct experimental validation protocols.

Core Accuracy Dimensions:

- Growth Rate Prediction: Agreement between predicted and experimentally measured biomass accumulation rates under defined conditions.

- Essentiality Prediction (Gene/Reaction): Ability to correctly classify genes or reactions as essential or non-essential for growth in a given environment.

- Flux Distribution Prediction: Correlation between predicted internal metabolic reaction fluxes and experimentally determined fluxes (e.g., via 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis).

- Substrate Uptake/Secretion Rate Prediction: Accuracy in predicting exchange reaction fluxes for nutrients and by-products.

Scientific Context and Assessment Framework

Accuracy is contingent upon multiple interdependent factors. A comprehensive assessment framework must account for these variables, which form the core of ongoing methodological research.

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing FBA Prediction Accuracy

| Factor | Description | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Model Quality | Completeness, curation level, and correctness of the GSMM (stoichiometry, gene-protein-reaction rules, compartmentalization). | Foundational; errors here propagate systematically. |

| Constraint Definition | Precision and correctness of the constraints applied (e.g., uptake/secretion bounds, ATP maintenance, enzyme capacity). | Directly determines solution space; inaccurate constraints lead to inaccurate predictions. |

| Objective Function | The biological goal (e.g., biomass maximization) assumed for the organism in the simulated condition. | A critical biological assumption; incorrect objectives misdirect predictions. |

| Algorithm & Solution | The specific FBA variant (e.g., pFBA, ROOM, MOMA) and numerical solver used. | Affects precision and biological relevance of the selected flux solution from the feasible space. |

| Experimental Data Quality | Precision and relevance of the validation data used for comparison (e.g., chemostat vs. batch growth measurements). | Determines the reliability of the accuracy benchmark. |

Quantitative Data on Typical FBA Accuracy

Recent literature and meta-analyses provide benchmarks for expected accuracy across common prediction tasks. The data below summarizes findings from current research.

Table 2: Reported Ranges of FBA Prediction Accuracy in Literature

| Prediction Type | Typical Accuracy Range | Common Validation Method | Key Limiting Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate (Quantitative) | R² ~ 0.6 - 0.8 vs. experimental rates for microbes across carbon sources. | Measured specific growth rate (μ) in controlled bioreactors. | Inaccurate maintenance energy constraints; regulatory effects not captured. |

| Gene Essentiality (Classification) | 80-95% Sensitivity (true positive rate); 80-90% Specificity (true negative rate) for model organisms like E. coli. | Data from systematic gene knockout libraries and growth assays. | Incomplete model annotation; condition-specific regulation; isoenzymes. |

| Flux Distribution (13C MFA) | Pearson correlation ~ 0.4 - 0.7 for central carbon metabolism fluxes. | 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) under steady-state conditions. | Model gaps in peripheral metabolism; kinetic regulation; assumption of optimality. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 5.1: Validating Growth Rate Predictions

- Objective: Quantitatively compare FBA-predicted growth rates with experimentally measured rates.

- Methodology:

- FBA Simulation: For a specific strain and defined growth medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium with 2 g/L glucose), set the corresponding exchange reaction bounds in the GSMM. Perform FBA maximizing for the biomass reaction. Record the predicted growth rate (in h⁻¹).

- Experimental Cultivation: Grow the corresponding biological strain in triplicate in the defined medium under controlled conditions (e.g., in a microplate reader or bioreactor with controlled temperature and aeration).

- Data Collection: Measure optical density (OD600) at regular intervals. Record data for at least 5-6 generations during exponential phase.

- Analysis: Fit the exponential growth phase data to the equation ln(OD) = μt + ln(OD₀) to calculate the experimental specific growth rate (μexp). Compare μexp to the FBA-predicted rate (μ_pred). Calculate error metrics (e.g., Absolute Relative Error).

Protocol 5.2: Validating Gene Essentiality Predictions

- Objective: Assess the classification accuracy of FBA in predicting essential vs. non-essential genes.

- Methodology:

- In silico Knockout: For each gene in a test set, modify the GSMM to simulate a knockout (e.g., by setting the bounds of associated reaction(s) to zero if no isozymes exist).

- FBA Simulation: Perform FBA with biomass maximization for each knockout model in the defined medium. A gene is predicted essential if the maximum biomass flux is below a threshold (e.g., < 1% of wild-type flux).

- Reference Data Compilation: Obtain a gold-standard experimental essentiality dataset (e.g., from the Keio collection for E. coli) for the same strain and similar medium conditions.

- Confusion Matrix Analysis: Compare predictions against experimental data. Calculate Sensitivity = TP/(TP+FN), Specificity = TN/(TN+FP), and Accuracy = (TP+TN)/(Total).

Visualization of Key Concepts

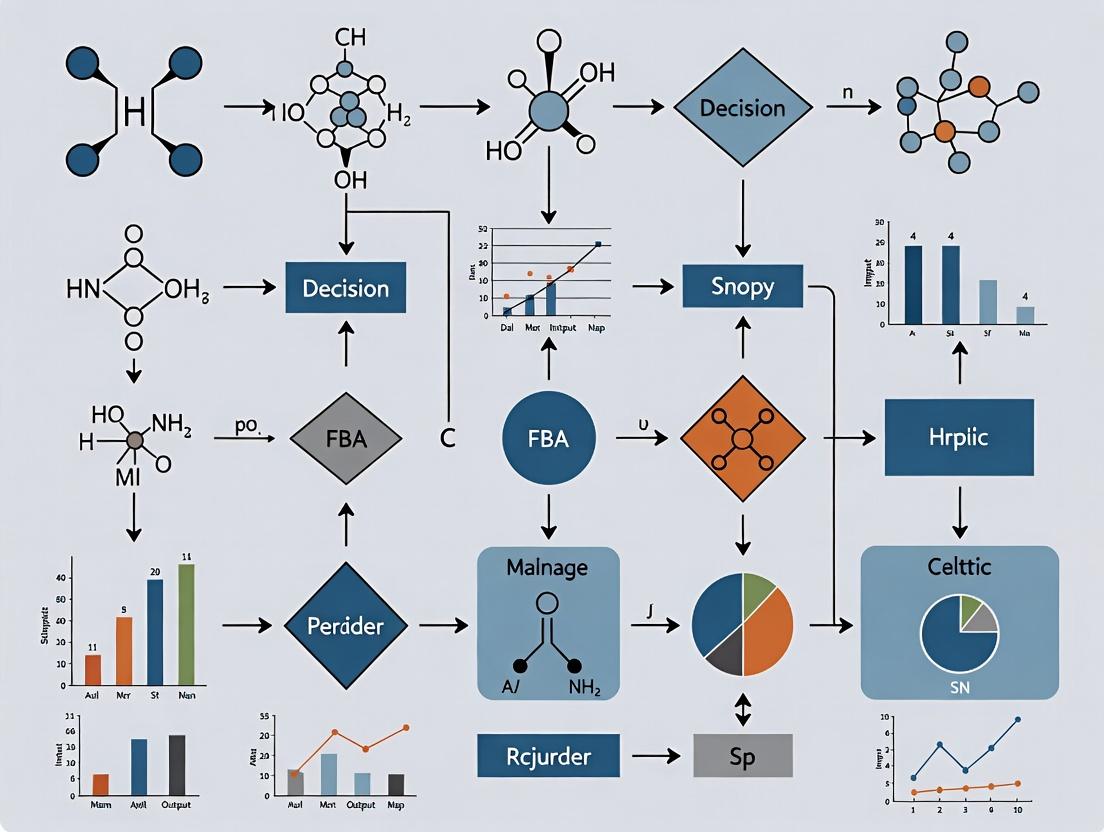

FBA Prediction Accuracy Assessment Framework

Iterative FBA Validation and Model Refinement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Resources for FBA Accuracy Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Curated GSMM Database | Provides standardized, peer-reviewed metabolic models for specific organisms as a starting point for analysis. | BioModels Database, CarveMe, ModelSEED. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction & Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | Primary software suite (Matlab/Python) for building models, running FBA simulations, and performing accuracy analyses. | COBRApy (Python), The COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB). |

| Omics Data Integration Platform | Enables generation of context-specific constraints (e.g., from RNA-Seq) to improve prediction accuracy. | GIMME, iMAT, INIT, PROM. |

| 13C-MFA Software & Isotope Tracers | Gold-standard for generating experimental intracellular flux data for validation of flux distribution predictions. | INCA, OpenFlux; [1-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glutamine. |

| Knockout Strain Collections | Provides physical reagents (bacterial strains) for systematic experimental validation of gene essentiality predictions. | E. coli Keio Collection, B. subtilis BKE Collection. |

| Cultivation & Growth Assay Systems | For generating quantitative growth phenotype data (growth rates, yields) under controlled conditions. | Microplate readers (e.g., BioTek), Bioreactors (DASGIP, BioFlo), OmniLog Phenotype MicroArrays. |

Key Challenges in Validating a Computational Model of Metabolism

The validation of computational models of metabolism, particularly those based on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), represents a cornerstone in systems biology and metabolic engineering research. This whitepaper details the core technical challenges in this validation process, framed explicitly within the ongoing research on FBA prediction accuracy assessment methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous validation is the critical bridge between in silico predictions and actionable biological insight, directly impacting areas like drug target identification and understanding metabolic adaptations in disease.

Core Validation Challenges and Quantitative Data

Validation necessitates a multi-faceted approach, comparing model predictions against quantitative experimental data. Key challenges and representative data are summarized below.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics and Typical Discrepancies

| Validation Metric | Experimental Method | Typical Goal (Model vs. Experiment) | Common Discrepancy Range (Literature Examples) | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate Prediction | Batch culture OD600/time, chemostat dilution rate | ≤ 20% error | 15-40% error common; context-dependent | Missing regulation, inaccurate ATP maintenance costs |

| Substrate Uptake/Secretion Rates | Metabolomics (LC-MS/GC-MS), EX rates | R² ≥ 0.8 | R² = 0.4-0.7 for full exometabolome | Incomplete transport reactions, co-factor imbalances |

| Gene Essentiality Prediction | CRISPR screens, transposon mutagenesis (Tn-Seq) | Accuracy ≥ 85%, Precision ≥ 0.8 | Accuracy: 70-90%, Precision: 0.65-0.85 | Poorly annotated isozymes, synthetic rescue mechanisms |

| (^{13})C Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) Comparison | (^{13})C labeling + isotopomer modeling | Major pathway fluxes within 10-20% | Central carbon fluxes within 15-30%; divergent elsewhere | Incorrect kinetic/gene regulatory constraints in model |

Table 2: Sources of Error in FBA Model Validation

| Error Source Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Model-Centric Errors | Incorrect stoichiometry, missing alternative pathways, wrong gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, inaccurate biomass composition. | Systemic bias; model cannot match data regardless of constraints. |

| Constraint-Centric Errors | Improper uptake bounds, wrong maintenance ATP (ATPM), lacking thermodynamic (loopless) or regulatory constraints. | Leads to physiologically impossible flux distributions that may still predict growth. |

| Data-Centric Errors | Noisy experimental data (e.g., low-throughput growth assays), mismatched culture conditions between model and experiment. | Invalid comparison baseline; apparent model error may be data error. |

| Context-Centric Errors | Model for standard lab strain, validation data from clinical isolate; ignoring plasmid burden in engineered strains. | Fundamental genotype/environment mismatch dooms validation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

To assess FBA accuracy, standardized protocols are essential.

Protocol 1: Coupling CRISPRi Essentiality Screens with FBA Predictions

- Design: Design sgRNAs targeting all metabolic genes in the model organism (e.g., E. coli K-12 MG1655).

- Library Construction: Clone sgRNAs into a inducible CRISPRi plasmid backbone. Transform into strain with dCas9 expression.

- Growth Experiment: Dilute transformation to OD600 0.01 in LB + inducer. Distribute into 96-well plates. Incubate at 37°C with continuous shaking in a plate reader.

- Data Acquisition: Measure OD600 every 15 minutes for 24 hours. Calculate maximum growth rate (μ_max) for each gene knockdown.

- Analysis: Normalize μ_max to non-targeting sgRNA control. Define essential gene as >50% growth defect. Compare to FBA-predicted essentiality (simulate gene knockout, growth <5% of wild-type).

- Key Reagents: Inducible CRISPRi plasmid system, appropriate chemocompetent cells, LB medium, inducing agent (aTc/IPTG).

Protocol 2: (^{13})C-MFA for Core Flux Validation

- Tracer Experiment: Grow organism in minimal medium with a (^{13})C-labeled carbon source (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]glucose). Use chemostat or mid-exponential phase batch culture.

- Quenching & Extraction: Rapidly quench metabolism (cold methanol/saline). Perform intracellular metabolite extraction.

- Derivatization & MS: Derivatize proteinogenic amino acids (from hydrolyzed biomass) or central metabolites. Analyze via GC-MS.

- Flux Calculation: Use software (e.g., INCA, Iso2Flux) to fit metabolic network model to measured mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs), estimating intracellular fluxes.

- Comparison: Statistically compare estimated net fluxes (e.g., PPP, TCA) to FBA predictions under the same nutrient conditions.

Visualization of Validation Workflows and Conceptual Relationships

Title: Iterative FBA Model Validation and Refinement Cycle

Title: Data Integration and Prediction Pathways for FBA Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for FBA Validation Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | The core in silico construct for prediction. Must be organism-specific (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli, Recon3D for human). | Currency: Use latest community-curated version. Ensure consistent annotation (e.g., BiGG IDs). |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software | Platform for simulating FBA and variants (pFBA, ROOM). Enables knockout simulations. | COBRApy (Python), CellNetAnalyzer (MATLAB), and the COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) are standards. |

| (^{13})C-Labeled Substrates | Tracers for experimental flux determination via (^{13})C-MFA. | Purity (>99% (^{13})C) is critical. Common tracers: [1-(^{13})C]glucose, [U-(^{13})C]glutamine. |

| CRISPRi/a Library | For high-throughput gene perturbation and essentiality testing. | Design for minimal off-target effects. Coverage of all metabolic genes in the model is ideal. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS System | For quantifying extracellular metabolites (exometabolomics) and analyzing (^{13})C mass isotopomers. | High sensitivity and linear dynamic range required. Use appropriate internal standards (e.g., (^{13})C, (^{15})N-labeled). |

| Chemostat Bioreactor | Enables steady-state cultivation for rigorous comparison of predicted vs. measured fluxes and rates. | Precise control of dilution rate, pH, dissolved O2 is necessary to match model assumptions. |

| Flux Estimation Software | Converts raw (^{13})C-MS data into intracellular flux maps. | INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) is the industry standard software suite. |

Within the context of Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment methods research, rigorous statistical evaluation is paramount. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on three core metrics essential for validating quantitative predictive models: Correlation Coefficients, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Prediction Confidence Intervals. These metrics collectively offer a framework to quantify the strength of association, magnitude of error, and the statistical uncertainty of predictions, which are critical for high-stakes applications such as inventory and sales forecasting.

Core Metrics: Definitions and Formulae

Correlation Coefficients

Correlation coefficients quantify the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables—typically predicted (Ŷ) and observed (Y) values.

- Pearson's r: Measures linear correlation.

- Formula: r = [Σ(Xᵢ - X̄)(Yᵢ - Ȳ)] / [√Σ(Xᵢ - X̄)² √Σ(Yᵢ - Ȳ)²]

- Range: -1 to +1.

- Spearman's ρ: Measures monotonic relationship (rank-based).

- Formula: ρ = 1 - [6Σdᵢ²] / [n(n² - 1)], where dᵢ is the difference in ranks.

- Range: -1 to +1.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

RMSE measures the average magnitude of prediction errors, giving higher weight to larger errors.

- Formula: RMSE = √[ Σ(Ŷᵢ - Yᵢ)² / n ]

- Units: Same as the original variable. Lower values indicate better predictive accuracy.

Prediction Confidence Intervals

A Prediction Interval (PI) provides a range for a single new observation, while a Confidence Interval (CI) provides a range for the mean response. For a linear regression prediction Ŷ₀ at point X₀, the 95% Prediction Interval is:

- PI: Ŷ₀ ± t(0.025, n-2) * S * √[1 + 1/n + (X₀ - X̄)² / Σ(Xᵢ - X̄)²]

- Where S is the residual standard error.

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

Table 1: Characteristics of Core Predictive Accuracy Metrics

| Metric | Primary Function | Sensitivity to Outliers | Interpretation | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson's r | Measures linear correlation | High | Strength/Direction of linear trend | Only captures linear dependence |

| Spearman's ρ | Measures monotonic correlation | Low (rank-based) | Strength/Direction of monotonic trend | Less powerful for linear data |

| RMSE | Measures average prediction error magnitude | High (due to squaring) | "Typical" error in original units | Scale-dependent; penalizes large errors heavily |

| Prediction Interval | Quantifies uncertainty for a single prediction | Moderate (via error variance) | Range likely to contain a future observation | Assumes normally distributed residuals |

Experimental Protocol for Metric Validation in FBA Research

A standardized protocol for applying these metrics to an FBA sales prediction model is as follows:

- Data Partitioning: Split historical FBA data (e.g., sales, inventory, seasonality metrics) into training (70%) and hold-out test (30%) sets.

- Model Training: Train the predictive model (e.g., ARIMA, Random Forest, or Neural Network) on the training set.

- Generate Predictions: Use the trained model to generate point predictions (Ŷᵢ) for the test set.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Compute Pearson's r and Spearman's ρ between vectors Ŷ and Y (actual test values).

- Compute RMSE using the formula in Section 1.2.

- For a selected key product (SKU), compute the 95% prediction intervals for its next 4-week forecast using the appropriate model-specific method (e.g., bootstrapping for ML models).

- Iterative Validation: Repeat steps 1-4 using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=10) to ensure robustness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Predictive Accuracy Assessment

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Assessment | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Core engine for calculation and visualization. | R: stats package; Python: scikit-learn, statsmodels, numpy. |

| Data Visualization Library | Creates diagnostic plots (residuals, Q-Q, actual vs. predicted). | ggplot2 (R), matplotlib/seaborn (Python). |

| Bootstrapping Library | Generates empirical prediction intervals for complex models. | boot (R), sklearn.utils.resample (Python). |

| Time-Series Database | Stores and queries temporal FBA data for model input. | InfluxDB, TimescaleDB. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables large-scale cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning. | Essential for complex models on large SKU datasets. |

Visualizing the Assessment Workflow

Diagram 1: Predictive Model Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Prediction, CI, and PI

Advanced Considerations in Metric Interpretation

- Metric Complementarity: Relying on a single metric is insufficient. A high r can coexist with a high RMSE if there is consistent bias. r assesses correlation, not agreement.

- Scale Dependency: RMSE is not comparable across different datasets or units. Use normalized metrics like Normalized RMSE (NRMSE) for such comparisons.

- Interval Estimation for ML Models: For non-linear machine learning models (e.g., gradient boosting), analytical PIs are often unavailable. Methods like quantile regression, conformal prediction, or bootstrapping are essential alternatives.

- Temporal Aspects in FBA: For time-series predictions, metrics must be computed on temporally held-out data to avoid autocorrelation artifacts, and intervals must account for increasing uncertainty over the forecast horizon.

In the systematic assessment of FBA prediction methods, correlation coefficients, RMSE, and prediction confidence intervals form a triad of indispensable metrics. Each addresses a distinct facet of model performance: association, error magnitude, and uncertainty quantification. Their integrated application, following rigorous experimental protocols, provides researchers and professionals with a comprehensive, statistically sound framework for model validation, selection, and deployment, ultimately driving more reliable and actionable forecasting in complex operational environments.

Within the critical research on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment methods, the validation of in silico metabolic models remains a paramount challenge. The predictive power of any FBA simulation is intrinsically tied to the quality of the constraints and objective functions applied, which must be grounded in empirical reality. This whitepaper examines the indispensable role of reference datasets derived from experimental flux measurements, which serve as the 'gold standards' against which model predictions are benchmarked, refined, and ultimately trusted.

The Imperative for Gold Standard Flux Data

FBA generates a solution space of possible metabolic flux distributions. Without experimental validation, it is impossible to determine if the predicted optimal flux state corresponds to the biological truth. Reference datasets from rigorous experimental techniques provide the necessary ground truth to:

- Assess Prediction Accuracy: Quantify the discrepancy between predicted and measured fluxes (e.g., using metrics like Mean Absolute Error or Pearson correlation).

- Guide Model Refinement: Identify systemic prediction errors, prompting corrections in gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, thermodynamic constraints, or network topology.

- Benchmark Algorithm Performance: Enable objective comparison between different FBA variants, optimization algorithms, or constraint methods.

Core Experimental Methodologies for Flux Measurement

The creation of gold standard datasets relies on a suite of advanced experimental protocols.

¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA)

This is the most established method for quantifying in vivo metabolic reaction rates in central carbon metabolism.

Detailed Protocol:

- Tracer Design: Cells are fed a substrate where one or more carbon atoms are replaced with the stable isotope ¹³C (e.g., [1-¹³C]glucose, [U-¹³C]glucose).

- Cultivation: Cells are cultured in a controlled bioreactor under defined physiological conditions until metabolic steady-state is achieved.

- Quenching & Extraction: Metabolism is rapidly quenched (e.g., using cold methanol). Intracellular metabolites are extracted.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Extracts are analyzed via Gas Chromatography- or Liquid Chromatography-coupled MS (GC-MS, LC-MS). The mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of key metabolites is determined.

- Computational Flux Estimation: An isotopic network model of the metabolic system is constructed. Non-linear least-squares regression is used to fit simulated MIDs to experimental MIDs, thereby estimating the flux map that best explains the labeling data. Statistical analysis (e.g., Monte Carlo sampling) provides confidence intervals for each estimated flux.

Fluxomics via Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

NMR spectroscopy provides complementary flux information, particularly useful for following ¹³C-labeling patterns through atomic bonds.

Detailed Protocol:

- Tracer Experiment: Similar setup using ¹³C-labeled substrates.

- In vivo or Extract Analysis: NMR can be performed on perchloric acid extracts or, uniquely, on living cells (in vivo NMR) for non-invasive time-course data.

- Spectrum Acquisition & Interpretation: ¹³C-NMR spectra reveal positional isotopomer information (e.g., fractional enrichment at each carbon atom). This data is used to constrain metabolic flux models.

Comparative Quantitative Analysis of Key Protocols

The choice of method involves trade-offs between resolution, scope, and technical demand.

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Flux Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Primary Resolution | Metabolic Scope | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-MFA (GC/LC-MS) | Net fluxes through pathways | Central Carbon Metabolism | High precision, comprehensive flux map in core metabolism. | Computationally intensive, limited scope beyond central metabolism. |

| ¹³C-NMR | Positional enrichment in molecules | Pathways producing NMR-visible compounds | Non-destructive (in vivo), provides direct bond-level labeling data. | Lower sensitivity compared to MS, requires larger sample sizes. |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) | Time-resolved fluxes | Central Carbon Metabolism | Captures transient metabolic states, no need for steady-state cultivation. | Extremely complex data acquisition and modeling. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Flux Experiments

| Item | Function in Flux Experiments |

|---|---|

| ¹³C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [U-¹³C]Glucose, [1,2-¹³C]Acetate) | Serve as isotopic tracers. The pattern of label incorporation into downstream metabolites is used to infer flux. |

| Silicon-coated Culture Ware | Minimizes cell adhesion and metabolite absorption to vessel walls, ensuring accurate extracellular metabolite measurements. |

| Quenching Solution (e.g., 60% cold Methanol with buffer) | Rapidly halts all enzymatic activity to "snapshot" the metabolic state at the time of sampling. |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MSTFA for GC-MS) | Chemically modify polar metabolites to increase their volatility and stability for GC-MS analysis. |

| Internal Standards (¹³C or ²H-labeled cell extract) | Added to samples prior to MS analysis to correct for variations in extraction efficiency and instrument response. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Amino Acid Mix (e.g., SILAC) | Used in proteomic-flux integrative studies to quantify protein turnover rates alongside metabolic fluxes. |

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Title: ¹³C-MFA Experimental and Computational Workflow

Title: FBA Validation Loop Using Gold Standard Flux Data

The advancement of FBA from a theoretical framework to a reliable predictive tool in systems biology and metabolic engineering is contingent upon the systematic use of high-quality reference datasets. Experimental flux measurements, primarily via ¹³C-based techniques, provide the essential gold standards that drive the iterative cycle of model prediction, validation, and refinement. For researchers focused on FBA prediction accuracy assessment, prioritizing the generation, curation, and intelligent application of these datasets is not merely beneficial—it is foundational to producing models that can accurately simulate and guide interventions in living systems, from microbial cell factories to human disease models in drug development.

This whitepaper serves as a core chapter in a broader thesis on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment methods. FBA is a cornerstone computational tool in systems biology and metabolic engineering, used to predict steady-state metabolic flux distributions within a reconstructed metabolic network. A critical yet often underappreciated aspect of applying FBA is establishing the theoretical, mathematical, and practical baselines that define the limits of its predictive capability. This document provides an in-depth technical guide to these limits, focusing on fundamental constraints, inherent uncertainties, and the establishment of objective performance benchmarks for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Mathematical and Theoretical Constraints

The predictive power of FBA is bounded by its foundational assumptions and mathematical structure. The core FBA problem is expressed as:

Maximize/Minimize: ( Z = c^T v ) Subject to: ( S \cdot v = 0 ) ( v{min} \leq v \leq v{max} )

Where ( S ) is the stoichiometric matrix, ( v ) is the flux vector, and ( c ) is the objective vector.

The theoretical limits arise from:

- Underdetermination: For most genome-scale models, the number of fluxes (n) far exceeds the number of metabolites (m), leading to a high-dimensional solution space (null space of S).

- Solution Non-Uniqueness: The optimal value of the objective function (Z) may be achieved by multiple, distinct flux distributions (alternate optimal solutions).

- Network Completeness: Predictions cannot account for reactions or regulatory mechanisms absent from the stoichiometric reconstruction.

- Steady-State Assumption: The model assumes constant internal metabolite concentrations, an idealization rarely true in vivo.

Quantitative Analysis of Prediction Boundaries

The following table summarizes key quantitative parameters that define the boundaries of FBA predictions, based on a survey of current literature and standard genome-scale reconstructions.

Table 1: Key Parameters Defining FBA Prediction Limits in Standard Models

| Parameter | E. coli (iJO1366) | S. cerevisiae (Yeast8) | Human (Recon3D) | Impact on Prediction Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactions (n) | 2,583 | 3,885 | 13,543 | Determines solution space dimensionality. |

| Metabolites (m) | 1,805 | 2,718 | 4,140 | Defines number of mass balance constraints. |

| Null Space Dimension (n - rank(S)) | ~778 | ~1,167 | ~9,403 | Primary driver of solution non-uniqueness. |

| Typical Measured Fluxes | 50-100 | 30-80 | <50 (often) | Severe limitation for validation/calibration. |

| Growth Rate Prediction Error (RMSE) | 0.05 - 0.12 h⁻¹ | 0.03 - 0.08 h⁻¹ | N/A (cell-type specific) | Baseline for objective function accuracy. |

| Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | 85-92% | 80-90% | 75-85% (context-dependent) | Baseline for gene-protein-reaction (GPR) logic. |

Experimental Protocols for Baseline Establishment

To empirically establish prediction baselines, the following methodologies are critical.

Protocol: Determining the Spectrum of Alternate Optimal Solutions

Purpose: To quantify the non-uniqueness of FBA solutions and establish a range of feasible flux distributions compatible with an observed phenotype.

- Solve the initial FBA problem to find the optimal objective value ( Z_{opt} ).

- Fix the objective function value to ( Z{opt} ) (or within a small tolerance, e.g., 99% of ( Z{opt} )) by adding a constraint: ( c^T v \geq 0.99 \cdot Z_{opt} ).

- Sample the resulting feasible solution space using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods (e.g., Artificial Centering Hit-and-Run, ACHR) or linear programming variance minimization.

- For each reaction, calculate the minimum and maximum possible flux across the sampled solutions. The range ( [v{min}^{opt}, v{max}^{opt}] ) defines the alternate optimum variability baseline. Interpretation: A reaction with a large range is poorly constrained by the model and objective; its FBA-predicted value should be considered highly uncertain.

Protocol: In Silico Gene Essentiality Screen Baseline

Purpose: To establish the upper limit of accuracy for predicting gene knockout effects based solely on network topology and GPR rules.

- Start with a validated, condition-specific metabolic model.

- For each gene ( gi ) in the model: a. Modify the flux bounds for all reactions associated with ( gi ) (via GPR rules) to zero. b. Solve the FBA problem for growth (or a relevant objective). c. If the optimal growth rate < ε (a small threshold, e.g., 0.001 h⁻¹), classify ( g_i ) as essential. Otherwise, classify as non-essential.

- Compare predictions to a gold-standard experimental dataset (e.g., from systematic knockout libraries).

- Calculate standard metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score. The F1-score represents the topology-based prediction baseline.

Protocol: Assessing Impact of Thermodynamic Constraints

Purpose: To evaluate how adding thermodynamic feasibility (via loopless constraints or Gibbs energy) narrows prediction boundaries.

- Perform flux variability analysis (FVA) on the base model to get initial ranges ( [v{min}^{base}, v{max}^{base}] ).

- Apply thermodynamic constraints (e.g., the loopless FBA constraint ( N{int} \cdot v = 0 ), where ( N{int} ) is the null space basis for internal reactions).

- Repeat FVA on the thermodynamically constrained model to get new ranges ( [v{min}^{thermo}, v{max}^{thermo}] ).

- For each reaction, compute the range reduction: ( 1 - (v{max}^{thermo} - v{min}^{thermo}) / (v{max}^{base} - v{min}^{base}) ). Interpretation: The average reduction across all reactions quantifies the tightening of prediction limits due to thermodynamics.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Diagram: FBA Solution Space and Theoretical Limits

Diagram: Experimental Protocol for Baseline Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Empirical Baseline Validation

| Item | Function in Baseline Research | Example/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Knockout Mutant Library | Provides experimental gold-standard data for gene essentiality baselines. Enables calculation of prediction accuracy limits. | E. coli Keio collection, S. cerevisiae Yeast Knockout (YKO) collection. |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [1-13C]Glucose) | Enables 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) to measure in vivo metabolic fluxes for comparison against FBA-predicted flux ranges. | Used with GC-MS or NMR to trace isotopic enrichment. |

| Chemically Defined Growth Media | Essential for controlled in silico and in vitro experiments. Ensures model nutrient constraints match experimental conditions. | M9 minimal media for bacteria, Synthetic Complete (SC) media for yeast. |

| Continuous Bioreactor (Chemostat) | Enables steady-state cultivation, the physiological condition assumed by FBA. Critical for generating matching model-experiment data. | Allows control of growth rate (dilution rate), a key FBA prediction output. |

| Flux Sampling Software | Computational tool to characterize the alternative optimal solution space and quantify prediction uncertainty. | COBRApy's sample function, MATLAB Cobra Toolbox's ACHRSampler. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Suite | Software platform to implement FBA, FVA, and gene knockout simulations for baseline establishment. | The COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python), Raven Toolbox. |

A Practical Guide to FBA Accuracy Assessment Methods and Their Applications

1. Introduction

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment, provides a technical guide for cross-validating genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). As FBA becomes integral to metabolic engineering and drug target discovery, robust validation frameworks bridging in silico predictions and in vivo observations are critical for model credibility and translational application.

2. Core Validation Paradigms & Quantitative Metrics

Validation requires comparing computational flux predictions against experimental data. Key quantitative metrics are summarized below.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Metrics for FBA Model Validation

| Metric | Description | Calculation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Proportion of correctly predicted growth/no-growth phenotypes. | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) | 1 |

| Precision | Proportion of predicted growth phenotypes that are correct. | TP/(TP+FP) | 1 |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | Proportion of actual growth phenotypes correctly predicted. | TP/(TP+FN) | 1 |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Average absolute difference between predicted and measured fluxes. | Σ|Predictedi - Measuredi| / n | 0 |

| Weighted Average Pearson Correlation | Correlation between predicted and measured fluxes, weighted by confidence. | Σ(wi * ri) / Σw_i | 1 |

3. Experimental Protocols for In Vivo Data Generation

In silico predictions must be tested against high-quality in vivo data. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments.

Protocol 3.1: Generation of Phenotypic Growth Data

- Objective: Create a gold-standard dataset of growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions.

- Materials: Microbial strain, defined minimal media, 96-well plates, plate reader.

- Method:

- Prepare minimal media with a single carbon source (e.g., glucose, acetate, succinate).

- Inoculate wells with a standardized cell density (OD600 ~0.05).

- Incubate in a plate reader at optimal growth temperature with continuous shaking.

- Measure OD600 every 15 minutes for 24-48 hours.

- Determine growth (OD600 increase >0.2) or no-growth.

- Output: Binary growth matrix (Condition × Growth).

Protocol 3.2: (^{13})C Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA)

- Objective: Obtain quantitative intracellular metabolic flux maps for comparison.

- Materials: (^{13})C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-(^{13})C]glucose), bioreactor, GC-MS, MFA software (e.g., INCA).

- Method:

- Grow cells in a chemostat or batch bioreactor with the (^{13})C-labeled substrate at steady-state.

- Quench metabolism rapidly, extract metabolites.

- Derivatize proteinogenic amino acids and measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) via GC-MS.

- Input MIDs, extracellular fluxes, and network model into MFA software.

- Iteratively fit fluxes to the experimental MID data.

- Output: Net and exchange fluxes for central carbon metabolism.

4. Cross-Validation Frameworks & Workflow

A systematic workflow integrates in silico and in vivo components.

Diagram Title: FBA Cross-Validation Iterative Workflow

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for FBA Cross-Validation

| Item | Function | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Curated GEM Database | Provides a starting point for organism-specific models. | BiGG Models, ModelSEED |

| FBA/QP Solver | Computes optimal flux distributions. | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), cobrapy (Python) |

| Defined Minimal Media | Enables controlled in vivo experiments and in silico constraint setting. | M9, MOPS minimal media kits |

| (^{13})C-Labeled Substrates | Essential tracers for generating in vivo flux data via (^{13})C-MFA. | [1-(^{13})C]Glucose, [U-(^{13})C]Glucose |

| MFA Software Suite | Calculates intracellular fluxes from mass isotopomer data. | INCA, IsoCor2, OpenFlux |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping | Rapidly generates growth data under many conditions. | Biolog Phenotype MicroArrays |

| Constraint Integration Tools | Algorithms to incorporate omics data as model constraints. | GIMME, iMAT, INIT |

6. Advanced Framework: Integrating Omics Data

Multi-omics data refines models, moving beyond binary validation. Transcriptomics can be integrated to create context-specific models.

Diagram Title: Omics Integration for Context-Specific FBA

7. Conclusion

A rigorous, iterative cross-validation framework is paramount for advancing FBA from a predictive tool to a reliable platform for in silico design in biotechnology and drug development. By systematically applying the protocols, metrics, and workflows outlined, researchers can quantitatively assess and iteratively improve model prediction accuracy, directly contributing to the core thesis of robust FBA assessment methodologies.

Within the systematic assessment of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy, the evaluation of phenotypic predictions—specifically microbial growth rates and substrate uptake kinetics—serves as the foundational empirical validation. This method directly compares in silico model outputs with in vitro experimental observations, providing a quantitative measure of a metabolic model's ability to recapitulate core physiological behavior. This guide details the protocols, data analysis, and key resources for executing this critical assessment.

Core Experimental Protocols

Chemostat-Based Growth Rate Determination

This protocol establishes steady-state conditions to isolate the relationship between a limiting substrate and growth rate.

- Apparatus Setup: Utilize a bench-top bioreactor with automated control of pH (e.g., maintained at 7.0), temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli), and dissolved oxygen (>30% saturation for aerobic cultures).

- Media & Inoculation: Prepare a defined minimal medium with a single carbon source (e.g., glucose, acetate) as the growth-limiting nutrient. All other nutrients are in excess. Inoculate with a pre-cultured microbial strain.

- Steady-State Achievement: Operate the chemostat at a fixed dilution rate (D). Steady-state is confirmed by stable optical density (OD₆₀₀) and effluent substrate concentration over at least five volume changes.

- Data Collection: At steady-state, measure:

- Biomass Concentration: Via OD₆₀₀, correlating to dry cell weight (DCW) using a pre-established calibration curve.

- Substrate Concentration: In the effluent via HPLC or enzymatic assay.

- Growth Rate (μ): Under steady-state chemostat conditions, μ = D (the dilution rate).

Batch Culture Substrate Uptake & Growth Kinetics

This protocol captures dynamic growth and uptake parameters.

- Culture Initiation: Inoculate defined minimal medium in a microtiter plate or shake flask with a single carbon source at a known concentration (e.g., 20 mM glucose).

- High-Frequency Monitoring: Use a plate reader or automated sampling system to measure:

- Biomass: OD₆₀₀ every 10-15 minutes.

- Substrate & Metabolites: Via in-line sensors or quenched samples analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

- Parameter Calculation: Fit the exponential phase of the OD curve to derive the maximum growth rate (μₘₐₓ). Calculate the substrate uptake rate from the disappearance of the carbon source during exponential growth, normalized to biomass.

Quantitative Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of FBA Models in Predicting E. coli K-12 MG1655 Phenotypes

| Carbon Source | Experimental μₘₐₓ (h⁻¹) | iML1515 Prediction (h⁻¹) | iJO1366 Prediction (h⁻¹) | Error (iML1515) | Error (iJO1366) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.79 | -3.5% | -7.1% |

| Glycerol | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.64 | -4.3% | -8.6% |

| Acetate | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.33 | +14.3% | -5.7% |

| Succinate | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.55 | -3.3% | -8.3% |

Table 2: Prediction Accuracy for Substrate Uptake Rates (mmol/gDCW/h)

| Carbon Source | Experimental Uptake | iML1515 Prediction | Absolute Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 10.2 | 9.8 | 0.4 |

| Glycerol | 8.5 | 8.9 | 0.4 |

| Pyruvate | 7.1 | 7.8 | 0.7 |

Visualizations

Workflow for Phenotypic Accuracy Assessment

Formulas for Growth, Uptake, and Error

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Phenotypic Validation Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Defined Minimal Medium (e.g., M9, MOPS) | Provides a chemically controlled environment, ensuring growth is solely linked to the single carbon source of interest, eliminating confounding nutrient effects. |

| Carbon Source Stocks (e.g., 40% Glucose, 1M Acetate) | High-purity, filter-sterilized solutions for precise control of substrate concentration in both batch and chemostat experiments. |

| Bioreactor / Fermentor System | Enables precise, continuous control of environmental parameters (pH, temp, O₂, feeding) essential for establishing reproducible steady-states in chemostats. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | For accurate quantification of substrate depletion and metabolite secretion (organic acids, alcohols) in culture supernatants. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits (e.g., for Glucose, Acetate) | Rapid, specific quantification of key metabolites, useful for high-throughput validation or when HPLC is unavailable. |

| Constraint-Based Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | The in silico subject (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli). Must be curated and formatted for use with simulation software (COBRApy, RAVEN). |

| FBA Simulation Software Suite (COBRA Toolbox) | Open-source platform to run FBA simulations, setting the objective function to maximize biomass reaction under the defined medium constraints. |

This whitepaper details the second method for assessing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy within a broader thesis research framework. FBA provides static, genome-scale flux predictions but lacks empirical validation. 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) offers experimentally determined, quantitative intracellular flux maps for central carbon metabolism. Flux Correlation Analysis directly compares FBA-predicted fluxes against 13C-MFA-measured fluxes, providing a rigorous, quantitative assessment of FBA model performance and identifying systematic gaps in predictive capability.

Core Methodology & Experimental Protocol

2.1 Prerequisite: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow A precise 13C-labeling experiment is foundational.

- Protocol:

- Tracer Selection: Cultivate cells in a defined medium where a carbon source (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) is partially or fully replaced with its 13C-labeled equivalent.

- Steady-State Cultivation: Maintain cells in a metabolic steady-state (e.g., continuous chemostat culture or exponential batch phase) for >5 generations to ensure isotopic equilibrium.

- Quenching & Extraction: Rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., cold methanol) and perform intracellular metabolite extraction.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Analyze extract via GC-MS or LC-MS to obtain mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of proteinogenic amino acids or metabolic intermediates.

- Computational Flux Estimation: Use software (e.g., INCA, 13CFLUX2) to fit a metabolic network model to the experimental MIDs via non-linear least-squares regression, yielding the statistically most likely flux map with confidence intervals.

2.2 Flux Correlation Analysis Protocol

- Step 1 – Flux Matching: Map the estimated net fluxes (in mmol/gDW/h) from 13C-MFA (typically for 50-100 reactions in central metabolism) onto their corresponding reactions in the genome-scale FBA model.

- Step 2 – FBA Simulation: Constrain the FBA model with the identical experimental conditions (e.g., substrate uptake rates, growth rate) measured during the 13C-MFA experiment. Solve the FBA problem to obtain predicted fluxes.

- Step 3 – Correlation & Statistical Analysis: Perform pairwise correlation (e.g., linear regression, Spearman's rank correlation) between the matched FBA-predicted and 13C-MFA-measured fluxes. Key metrics include the correlation coefficient (R), slope, and root-mean-square error (RMSE).

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparison

Table 1: Exemplary Flux Correlation Results from Published Studies

| Organism | FBA Model | 13C-MFA Condition | Correlation Coefficient (R) | Key Systemic Discrepancy Identified | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | iJO1366 | Aerobic, Glucose, Chemostat | 0.70 - 0.90 | Overprediction of TCA cycle vs. Glyoxylate shunt | (Antoniewicz, 2015) |

| S. cerevisiae | iMM904 | Anaerobic, Glucose, Batch | 0.40 - 0.65 | Poor prediction of pentose phosphate pathway split | (Kummel et al., 2010) |

| C. glutamicum | iCGB21FR | Biotin-Limited, Chemostat | 0.85 | Accurate prediction of lysine production fluxes | (Becker et al., 2020) |

| Mammalian Cells | RECON1 | HEK293, Glucose/Gln, Fed-Batch | 0.50 - 0.75 | Misallocation of glycolytic vs. mitochondrial fluxes | (Ahn et al., 2016) |

Table 2: Key Metrics for FBA Prediction Accuracy Assessment via Correlation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation in Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pearson's (R) | Cov(FBA, MFA) / (σFBA * σMFA) | Measures linear correlation strength. R² indicates variance explained. |

| Slope (m) | From regression: FluxFBA = m*FluxMFA + b | Ideal = 1. m < 1 indicates FBA under-predicts magnitude. |

| RMSE | √[ Σ(FBAi – MFAi)² / n ] | Absolute measure of average prediction error, in native flux units. |

| Bland-Altman Plot | Plot of (FBA+MFA)/2 vs. (FBA-MFA) | Visualizes bias (mean difference) and limits of agreement between methods. |

Visualizing the Workflow and Metabolic Networks

Title: 13C-MFA & FBA Correlation Analysis Workflow

Title: Key Central Carbon Metabolism for 13C-MFA

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 13C-MFA-based Flux Correlation Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function & Critical Specification |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon sources for tracer experiments (e.g., [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine). Purity >99% atom 13C is essential for accurate MID determination. |

| Defined Cell Culture Medium | Chemically defined medium without unlabeled carbon sources that would dilute the tracer, ensuring precise labeling input. |

| Quenching Solution | Cold aqueous methanol (-40°C to -80°C) for instantaneous halting of metabolic activity to capture in vivo MIDs. |

| Derivatization Reagents | For GC-MS analysis: e.g., MSTFA (N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) for converting metabolites to volatile trimethylsilyl derivatives. |

| Isotopic Flux Analysis Software | INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) or 13CFLUX2. Essential for non-linear fitting of fluxes to MID data. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Suite | COBRApy or MATLAB COBRA Toolbox. For running FBA simulations under 13C-MFA-derived constraints. |

| Statistical Software | R or Python (with SciPy/StatsModels). For performing robust correlation analysis, linear regression, and generating Bland-Altman plots. |

This guide details the third methodological pillar for assessing the accuracy of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) models within a broader research thesis. It focuses on validating model predictions of gene essentiality against empirical knockout data, providing a critical measure of a model's functional genetic representation.

Theoretical and Experimental Framework

Gene essentiality validation compares in silico predictions of growth/no-growth phenotypes following gene deletions with in vivo experimental results. The core metric is prediction accuracy, calculated as (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Predictions. High-throughput CRISPR-Cas9 screens now provide genome-wide experimental essentiality data (e.g., from projects like DepMap) as a gold standard for validation.

Table 1: Typical Performance Metrics of FBA Models in Gene Essentiality Prediction

| Model / Organism | Experimental Dataset (Source) | Prediction Accuracy (%) | Precision (Essential) | Recall (Essential) | Reference / Tool Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli iJO1366 | Keio Collection Phenotypes | 88.2 | 0.85 | 0.91 | Orth et al., 2011 |

| S. cerevisiae iMM904 | yeastGENOME Deletion Set | 83.5 | 0.89 | 0.78 | Dobson et al., 2010 |

| Human Recon 3D | CRISPR Screens (DepMap 22Q4) | 72.8 | 0.71 | 0.65 | Brunk et al., 2021 |

| M. tuberculosis iEK1011 | Transposon Sequencing (Tn-Seq) | 90.1 | 0.93 | 0.88 | Rienksma et al., 2015 |

Table 2: Impact of Medium Condition on Prediction Accuracy (Example: E. coli)

| Simulated Growth Medium | Genes Predicted Essential | True Positives | False Negatives | Condition-Specific Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Glucose (M9) | 356 | 312 | 44 | 87.6% |

| Rich Medium (LB) | 212 | 195 | 17 | 91.9% |

| Defined Anaerobic | 401 | 345 | 56 | 86.0% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Gene Knockout Simulation using FBA

- Model Preparation: Load the genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., in SBML format). Ensure gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules are correctly annotated.

- Knockout Implementation: For each gene

Gin the target list, set the flux bounds of all reactions associated exclusively withG(via its GPR rule) to zero. For reactions requiring multiple gene products, apply logical rules (e.g., AND/OR) to determine flux constraints. - Phenotype Prediction: Perform FBA, maximizing for the biomass objective function (BOF). A predicted growth rate > a defined threshold (e.g., 1e-6 mmol/gDW/hr) indicates a non-essential gene; growth below this threshold indicates an essential gene.

- Output: Generate a list of predicted essential and non-essential genes.

Protocol 2: Validation Using High-Throughput CRISPR-Cas9 Screen Data

- Data Acquisition: Download processed gene essentiality data (e.g., Chronos scores from DepMap). A Chronos score < -0.5 typically indicates essentiality; > -0.1 indicates non-essentiality.

- Data Mapping: Map the experimental gene identifiers (e.g., HUGO symbols) to the gene identifiers used in the metabolic model. This may require using annotation databases.

- Comparison & Metric Calculation: Create a confusion matrix by comparing the in silico predictions with the binarized experimental data.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), specificity, and F1-score. Perform receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis if quantitative fitness scores are available.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Title: In Silico Knockout Prediction Workflow

Title: Prediction Validation and Metric Calculation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Gene Essentiality Validation Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Genome-Scale Models | Provides the in silico framework with GPR rules for knockout simulations. | BiGG Models Database, MetaNetX |

| CRISPR Screen Datasets | Empirical genome-wide essentiality data for validation. | DepMap Portal, Project Score (Sanger) |

| Gene Annotation Mapper | Maps gene identifiers between model and experimental datasets. | UniProt ID Mapping, BioMart |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Suite | Software for performing in silico knockouts and FBA. | CobraPy (Python), COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) |

| Essentiality Analysis Pipeline | Streamlines comparison and statistical analysis. | GEM2EC (Model-to-Experiment Compare) |

| Chemically Defined Media Formulations | For simulating condition-specific gene essentiality in models and lab experiments. | ATCC Medium Recipes, Biolog Phenotype Microarrays |

This technical guide explores the rigorous application of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment within drug discovery and metabolic engineering. Positioned within a broader thesis on FBA accuracy assessment methodologies, this case study demonstrates how quantitative validation frameworks are critical for transitioning in silico predictions to in vivo therapeutic and bioproduction outcomes. The convergence of constraint-based modeling and multi-omics validation forms the cornerstone of reliable target identification and pathway engineering.

Foundational Concepts: FBA and Accuracy Metrics

Flux Balance Analysis is a mathematical approach for predicting steady-state metabolic fluxes in biochemical networks. Its accuracy in predicting phenotypes—essential for identifying drug targets or engineering high-yield pathways—must be systematically quantified.

Key Accuracy Assessment Metrics:

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation in Drug/Target Context |

|---|---|---|

| True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) | TPR = TP / (TP + FN) | Ability to correctly identify essential genes as potential drug targets. |

| Positive Predictive Value (Precision) | PPV = TP / (TP + FP) | Reliability of predicted essential genes; high value reduces costly experimental follow-up on false leads. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | MCC = (TP×TN - FP×FN) / √((TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)(TN+FN)) | Balanced measure for imbalanced datasets (e.g., few essential genes among many). |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | MAE = (1/n) Σ |ypred - yexp| | Measures average deviation of predicted from experimental growth rates or metabolite yields. |

TP: True Positive, FP: False Positive, TN: True Negative, FN: False Negative, y_pred: predicted flux/yield, y_exp: experimental flux/yield.

Case Study 1: Target Identification inMycobacterium tuberculosis

This case applies accuracy assessment to validate an FBA model of M. tuberculosis metabolism for pinpointing new antibacterial targets.

Experimental Protocol:In SilicoGene Essentiality Prediction vs. Experimental Validation

- Model Curation: Start with a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iEK1011). Apply constraints from transcriptomic data of M. tuberculosis under infection-like conditions.

- In Silico Knockout Simulation: For each gene, perform an FBA simulation with its reaction(s) constrained to zero flux. Predict growth rate.

- Classification: Classify genes as predicted essential (growth rate < 5% of wild-type) or non-essential.

- Reference Data Compilation: Compile high-confidence experimental essentiality data from saturated transposon mutagenesis (Tn-Seq) studies.

- Accuracy Calculation: Construct a confusion matrix comparing in silico predictions to experimental data. Calculate TPR, PPV, MCC.

- Model Refinement: Identify false predictions (FP/FN). Investigate gaps (e.g., missing isozymes, wrong gene-protein-reaction rules) and iteratively refine the model.

Results and Accuracy Assessment Table

Table 1: Accuracy metrics for *M. tuberculosis FBA model gene essentiality predictions.*

| Model Version | Sensitivity (TPR) | Precision (PPV) | MCC | Key Insight from False Predictions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Model (iNJ661) | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.55 | High FN in lipid metabolism; model lacked host-derived nutrient uptake. |

| Context-Specific (iEK1011) | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.82 | Inclusion of host-derived cholesterol & hypoxia constraints reduced FP. |

Fig 1. Workflow for assessing FBA target prediction accuracy.

Case Study 2: Accuracy-Driven Engineering of Lycopene Biosynthesis

This case assesses the accuracy of FBA in predicting flux changes for metabolic engineering in E. coli.

Experimental Protocol: Predicting and Validating Overproduction Strains

- Base Model & Objective: Use a high-quality E. coli model (e.g., iML1515). Set objective to maximize lycopene biosynthesis reaction flux.

- Design Interventions: Use FBA simulations to predict knockout/up-regulation targets (e.g., crtEIB overexpression, glgC, lpdA knockouts).

- Predict Yield: Simulate the engineered strain in silico and predict lycopene yield (mg/gDCW).

- Strain Construction: Build the top-predicted strain designs in vivo using CRISPR-Cas9 and plasmid overexpression.

- Fermentation & Measurement: Cultivate strains in controlled bioreactors. Measure growth (OD600), substrate uptake, and lycopene titer via HPLC.

- Accuracy Quantification: Calculate MAE and correlation (R²) between in silico predicted and in vivo measured yields across all engineered strains.

Results and Accuracy Assessment Table

Table 2: Comparison of predicted vs. experimental lycopene yields for different strain designs.

| Strain Design (Modifications) | FBA Predicted Yield (mg/gDCW) | Experimental Yield (mg/gDCW) | Absolute Error | Key Model Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.005 | Baseline flux minimal. |

| OE: crtEIB | 5.2 | 3.1 | 2.1 | Model overestimated precursor supply. |

| OE: crtEIB, KO: glgC | 18.7 | 16.5 | 2.2 | Improved match; competition for G3P captured. |

| OE: crtEIB, dxs, KO: glgC, lpdA | 24.3 | 19.8 | 4.5 | Model underestimated redox stress. |

| Aggregate Metrics | MAE = 2.2 mg/gDCW | R² = 0.93 |

Fig 2. Engineered pathway for lycopene with key modifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and tools for conducting FBA accuracy assessment studies.

| Item Name | Function & Application | Example Vendor/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | Structured knowledgebase of organism metabolism for simulation. | BIGG Models, MetaNetX, CarveMe |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction & Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | MATLAB/Python suite for running FBA and conducting accuracy tests. | COBRApy (Python), cvxGurobi (solver) |

| Experimental Essentiality Data (Tn-Seq) | Gold-standard reference data for validating in silico gene essentiality. | PkSeqDB, OGEE, Original Literature |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Toolkit | For precise genomic knockouts/edits in engineered strains. | Commercial kits (e.g., from NEB, Sigma) |

| HPLC-MS System | Quantifying metabolite titers (e.g., lycopene) for yield validation. | Agilent, Waters, Thermo Fisher |

| Fluxomics Standard (13C-Glucose) | Enables experimental flux measurement via 13C-MFA for direct model comparison. | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories |

| Omics Data (RNA-Seq) | Provides context-specific constraints for improving model accuracy. | NCBI GEO, ENA; Alignment tools (HISAT2, Salmon) |

Optimizing FBA Model Accuracy: Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls and Refinement Strategies

In the rigorous domain of drug development, the prediction of Fraction Bound to Albumin (FBA) is a critical pharmacokinetic parameter. Inaccuracies in FBA prediction can cascade into costly errors in dose estimation and clinical trial design. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on FBA prediction accuracy assessment methods, provides a systematic framework for researchers and scientists to diagnose the root cause of poor predictive performance. We dissect the triad of potential culprits: the predictive model itself, the quality and nature of the training data, and the experimental or computational methodology employed.

The Diagnostic Framework: A Systematic Approach

The first step is to isolate the source of error. The following workflow outlines a structured diagnostic pathway.

Interrogating the Data

Data quality is the most frequent source of error. Key quantitative checks must be performed.

Table 1: Data Quality Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Calculation/Description | Acceptance Threshold | Implication of Breach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Noise | Coefficient of Variation (CV) for replicate measurements. | CV < 15% | High intrinsic noise limits achievable accuracy. |

| Systematic Bias | Mean signed error between historical assay results and a gold-standard method. | Absolute Mean Error < 5% | Data used for training is inherently offset. |

| Structural Diversity | Tanimoto similarity index distribution across the dataset. | >70% of pairwise similarities < 0.4 | Model may not generalize to novel chemotypes. |

| Value Distribution | Histogram of FBA values. | Balanced across 0-100% range | Poor performance on under-represented ranges. |

| Outlier Density | Modified Z-score using Median Absolute Deviation. | <5% of data points | Outliers can disproportionately skew model parameters. |

Experimental Protocol for Data Validation (Equilibrium Dialysis Gold Standard):

- Preparation: Use a Teflon dialysis cell separated by a semi-permeable membrane (MWCO 12-14 kDa). Prepare a human serum albumin (HSA) solution in physiologically relevant buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4).

- Spiking: Add the test compound (radiolabeled or UV-detectable) to the HSA-containing chamber (donor). The buffer chamber is the receiver.

- Equilibration: Incubate cells at 37°C with gentle agitation for a predetermined time (e.g., 4-24 hrs) to reach equilibrium.

- Sampling & Analysis: Aliquot samples from both chambers. Quantify compound concentration using LC-MS/MS. Calculate FBA: %FBA = (Cdonor - Creceiver) / C_donor * 100.

- Controls: Include a negative control (compound in buffer only) and a high-binding positive control (e.g., warfarin).

Evaluating the Model

The model must be tested for its inherent capacity and bias.

Table 2: Model Diagnostic Tests

| Test | Protocol | Expected Outcome for a Robust Model |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Curve | Train models on incrementally larger random subsets of data. Plot training & validation error. | Validation error converges smoothly; gap between curves is small. |

| Residual Analysis | Plot prediction error (residual) vs. predicted value, molecular weight, LogP, etc. | Residuals are randomly scattered with no discernible pattern. |

| Applicability Domain | Calculate the leverage (h) for each prediction using the training set's feature matrix. | Predictions for compounds with high leverage (h > 3p/n, where p=features, n=samples) are flagged as extrapolations. |

| Baseline Comparison | Compare model performance to a simple baseline (e.g., predicting the mean FBA, or using a linear model). | The proposed model significantly outperforms (lower RMSE) the naive baseline. |

Scrutinizing the Method

Methodological inconsistencies between training data generation and prediction application are a common hidden flaw.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in FBA Assessment |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Serum Albumin (rHSA) | Provides a consistent, pathogen-free ligand source for binding studies, reducing batch-to-batch variability. |

| 96-Well Equilibrium Dialysis Blocks | Enables high-throughput measurement of free fraction, increasing data generation speed and consistency. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Gold-standard for sensitive and specific quantification of unlabeled compounds in complex matrices like plasma or buffer. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors | Measures binding kinetics (ka, kd) and affinity (KD) directly, informing mechanistic models beyond static %FBA. |

| Chemoinformatics Software (e.g., RDKit) | Enables calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints essential for QSAR and machine learning models. |

| Phospholipid Vesicle Suspensions | Used in methods like immobilized protein chromatography to account for non-specific membrane partitioning. |

An Integrated Experimental Protocol for Holistic Diagnosis

The following combined protocol assesses all three elements simultaneously.

Protocol: Tiered FBA Accuracy Verification

- Tier 1 - Internal Consistency: Select 20 diverse compounds from your dataset. Re-measure FBA using your primary method (e.g., equilibrium dialysis) in triplicate. Calculate the intra-method reproducibility (RMSE).

- Tier 2 - Cross-Methodological Validation: For the same 20 compounds, measure FBA using an orthogonal method (e.g., ultrafiltration or spectroscopic titration). Assess the inter-method concordance (Pearson's r, Bland-Altman plot).

- Tier 3 - Model Blind Test: Using the new, verified Tier 1 data, test the predictions of your existing model. Perform residual analysis to identify structural or physicochemical biases.

- Analysis: Systematic error in Tier 1 points to Method issues. Discordance in Tier 2 highlights Method-comparison problems. Consistent, structured errors in Tier 3 implicate the Model or the Data used to train it.

Diagnosing poor accuracy in FBA prediction requires moving beyond aggregate error metrics. By employing a structured framework that quantitatively dissects data quality, model behavior, and methodological alignment, researchers can precisely identify the root cause. This systematic approach, central to advancing FBA prediction accuracy assessment methods, ensures that corrective efforts are targeted efficiently—whether that entails refining assay protocols, curating higher-fidelity data, or developing more robust, generalizable models—ultimately de-risking critical decisions in pharmaceutical development.

Addressing Gaps and Inaccuracies in Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions (GEMs)

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions (GEMs) are in silico representations of the metabolic network of an organism, derived from its annotated genome and biochemical knowledge. They serve as a cornerstone for constraint-based metabolic modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). However, their predictive accuracy is fundamentally constrained by inherent gaps (missing reactions and genes) and inaccuracies (incorrectly annotated functions, erroneous stoichiometry, or false directionality). This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on FBA prediction accuracy assessment, provides a technical guide to identifying, characterizing, and rectifying these limitations to build more predictive metabolic models.

Curation and Annotation Errors

- Incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules: Automated annotations from sequence homology often propagate errors, leading to incorrect Boolean logical relationships.

- Missing or Erroneous Transport and Exchange Reactions: Incomplete definition of system boundaries severely limits predictive capability for environmental conditions.

- Inaccurate Reaction Stoichiometry and Directionality: Use of thermodynamically infeasible reaction directions or incorrect cofactor balances leads to energy-generating cycles and unrealistic flux predictions.

Biological Complexity

- Gaps in Pathway Knowledge: Known metabolic outputs with no genetically defined synthesis pathway.

- Promiscuous Enzyme Activities: Multifunctional enzymes that are not captured by standard GPR rules.

- Compartmentalization Uncertainty: Misassignment of reactions to cellular compartments (e.g., cytosol vs. mitochondria).

- Regulatory Constraints: Post-transcriptional, allosteric, and metabolic regulation not inherently captured in stoichiometric models.

Quantitative Assessment of Reconstruction Quality

Table 1: Key Metrics for GEM Quality Assessment

| Metric | Formula/Description | Target/Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Gap Fraction | (No. of Dead-End Metabolites / Total No. of Metabolites) * 100 | Lower is better (<10% is a typical goal). Indicates network connectivity issues. |

| Network Connectivity | Average number of reactions per metabolite. | Higher values suggest better integration and fewer gaps. |

| Functional Coverage | Percentage of metabolic subsystems (e.g., from ModelSEED or MetaCyc) represented in the GEM. | Higher coverage increases model generalizability. |

| Prediction Accuracy vs. Omics | e.g., Correlation between predicted essential genes and experimental knockout data (ROC-AUC). | AUC > 0.8 indicates good predictive capability. |

| Thermodynamic Feasibility | Percentage of reactions with assigned, consistent ΔG°' values enabling loopless flux solutions. | Prevents generation of thermodynamically infeasible cycles (Type III loops). |

Experimental Protocols for Gap Filling and Validation

Protocol: Gap Filling Using Growth Phenotype Data

Objective: To add missing reactions required for the model to simulate observed growth on specific carbon sources.

- Define Objective: Set biomass production as the objective function.

- Define Constraints: Constrain uptake rates for the target carbon source (e.g., glucose, myo-inositol) and essential nutrients (N, P, S, O2).

- Perform Simulation: Run FBA. If no growth is predicted, a gap exists.

- Identify Candidate Reactions: Use a universal biochemical database (e.g., MetaCyc, KEGG) as a reaction pool.

- Solve Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Problem: Minimize the number of reactions from the pool that must be added to the model to enable growth.

- Biochemical Validation: Literature search to prioritize added reactions based on genomic or enzymatic evidence.

Protocol: Validating GPR Associations with CRISPRi/KO Fitness Data

Objective: To test the accuracy of gene essentiality predictions.

- Generate In Silico Knockouts: For each gene in the GEM, modify its GPR rule to force it to be non-functional (e.g., set the gene's state to FALSE in a Boolean rule).

- Predict Growth Phenotype: Run FBA for each in silico knockout under defined media conditions. Predict growth (flux > 0) or no growth (flux = 0).

- Acquire Experimental Data: Obtain high-confidence gene fitness scores from pooled CRISPR-interference or knockout screens under matched conditions.

- Compare and Calculate Accuracy: Classify genes as essential (experimental fitness score < threshold, e.g., -0.5) or non-essential. Compare to FBA predictions to calculate Precision, Recall, and ROC-AUC (See Table 1).

Methodologies for Refining Reconstructions

Integrative Omics for Curation

- Transcriptomics/Proteomics: Used to create condition-specific models (GIMME, iMAT) or to weight reactions during gap-filling.

- Metabolomics: Crucial for identifying dead-end metabolites and validating predicted secretion profiles.

- Thermodynamic Data (Equilibrator): Assigning reaction directionality based on estimated ΔG°' under physiological conditions.

Computational Tools Pipeline

Diagram Title: Iterative GEM Curation and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Advanced GEM Development and Testing

| Item (Tool/Database) | Category | Primary Function in GEM Curation |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox (Matlab) | Software | Core suite for constraint-based modeling, FBA, and gap-filling. |

| CarveMe / ModelSEED | Reconstruction | Automated pipeline for draft GEM building from genome annotation. |

| RAVEN Toolbox | Software | Reconstruction, curation, and integration of omics data in MATLAB. |

| MEMOTE | Software | Suite for standardized testing and quality reporting of GEMs. |

| Equilibrator API | Database/Software | Calculates standard reaction Gibbs free energy (ΔG°') for thermodynamic consistency. |

| MetaCyc / KEGG | Database | Universal reaction databases used as pools for gap-filling algorithms. |

| BiGG Models | Database | Repository of high-quality, manually curated GEMs for comparison and validation. |

| GECKO Toolbox | Software | Enhances GEMs with enzyme constraints using proteomics data. |

Logical Framework for Addressing Inconsistencies

Diagram Title: Diagnostic Logic Flow for GEM Inaccuracies

Addressing gaps and inaccuracies in GEMs is not a one-time task but a continuous, iterative process of computational prediction and experimental validation. The integration of high-throughput phenotyping, CRISPR-based functional genomics, and metabolomics data provides an empirical foundation for rigorous model refinement. By employing the standardized metrics, protocols, and tools outlined in this guide, researchers can systematically improve the biochemical fidelity and predictive accuracy of metabolic reconstructions. This effort is central to advancing the utility of FBA and related methods in fundamental research, biotechnology, and drug development, where accurate in silico models can prioritize costly wet-lab experiments and generate testable mechanistic hypotheses.

Within the broader research on Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) prediction accuracy assessment methods, a critical frontier lies in moving beyond stoichiometric constraints. Classical FBA often yields infinite flux solutions or physiologically implausible predictions due to underdetermination. This whitepaper details advanced methodologies for refining constraint sets by integrating thermodynamic and kinetic data, thereby enhancing the predictive accuracy and practical utility of metabolic models in biotechnology and drug development.

Core Concepts: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Constraints

Thermodynamic Constraints

Thermodynamic constraints eliminate flux solutions that violate the laws of thermodynamics, primarily the second law which dictates the directionality of reactions based on Gibbs free energy.

- Gibbs Free Energy of Reaction (ΔᵣG'): Determines reaction reversibility. A negative ΔᵣG' favors the forward direction.

- Energy Balance Analysis (EBA): A formalism that integrates ΔᵣG' constraints into FBA, ensuring all loops are energy-dissipative.

Kinetic Constraints