Engineering Secondary Metabolites in Plants and Microbes: Pathways, CRISPR, and Microbial Synthesis for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for engineering the production of valuable secondary metabolites in plants and microbes.

Engineering Secondary Metabolites in Plants and Microbes: Pathways, CRISPR, and Microbial Synthesis for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for engineering the production of valuable secondary metabolites in plants and microbes. It covers foundational knowledge of major metabolic pathways, explores advanced methodological tools like CRISPR-Cas9 and microbial co-culture, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and discusses validation and comparative analysis techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current research to guide the efficient production of plant-derived pharmaceuticals and other high-value compounds.

The Foundation of Chemical Diversity: Understanding Plant and Microbial Secondary Metabolites

Defining Secondary Metabolites and Their Crucial Roles in Defense and Medicine

Secondary metabolites (SMs) are specialized organic compounds produced by plants, microbes, and other organisms that are not directly essential for basic growth, development, or reproduction but are crucial for survival, ecological interactions, and environmental adaptation [1] [2]. Unlike primary metabolites, which are ubiquitous and involved in fundamental life processes, the production of SMs is often restricted to specific species, genera, or families, and their synthesis can be induced by various environmental stresses [3] [2]. These molecules serve as a primary interface between the producing organism and its environment, fulfilling a multitude of roles from chemical defense to communication. In the context of modern biotechnology, understanding the structure, function, and biosynthesis of these compounds is fundamental to engineering plants and microbes for enhanced agricultural output and novel pharmaceutical applications. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of secondary metabolites, delineating their classifications, biosynthetic origins, and pivotal functions in defense and medicine, thereby framing the critical knowledge base for ongoing metabolic engineering research.

Classification and Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites

Secondary metabolites are categorized based on their chemical structures and biosynthetic pathways. The three major classes are terpenoids, phenolics, and nitrogen-containing compounds (including alkaloids). Their biosynthesis diverges from primary metabolic pathways, utilizing key precursors to generate a vast array of complex structures.

Table 1: Major Classes of Plant Secondary Metabolites

| Class | Basic Structure/Building Block | Key Examples | Biosynthetic Pathway(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Isoprene units (C₅H₈) | Artemisinin (antimalarial), Taxol (anticancer), Limonene [4] [5] [2] | Mevalonate (MVA) pathway; Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) pathway [2] |

| Phenolics | C6 aromatic ring with hydroxyl group(s) | Flavonoids (e.g., Quercetin), Lignins, Tannins, Resveratrol [5] [3] [2] | Shikimate pathway; Phenylpropanoid pathway [5] [2] |

| Alkaloids | Nitrogen-containing heterocycles | Morphine (analgesic), Quinine (antimalarial), Caffeine [5] [6] [2] | Derived from amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, tryptophan) [2] |

| Sulfur-containing Compounds | Molecules containing sulfur | Glucosinolates, Allicin (from garlic) [5] [7] | Derived from amino acids like cysteine and methionine [7] |

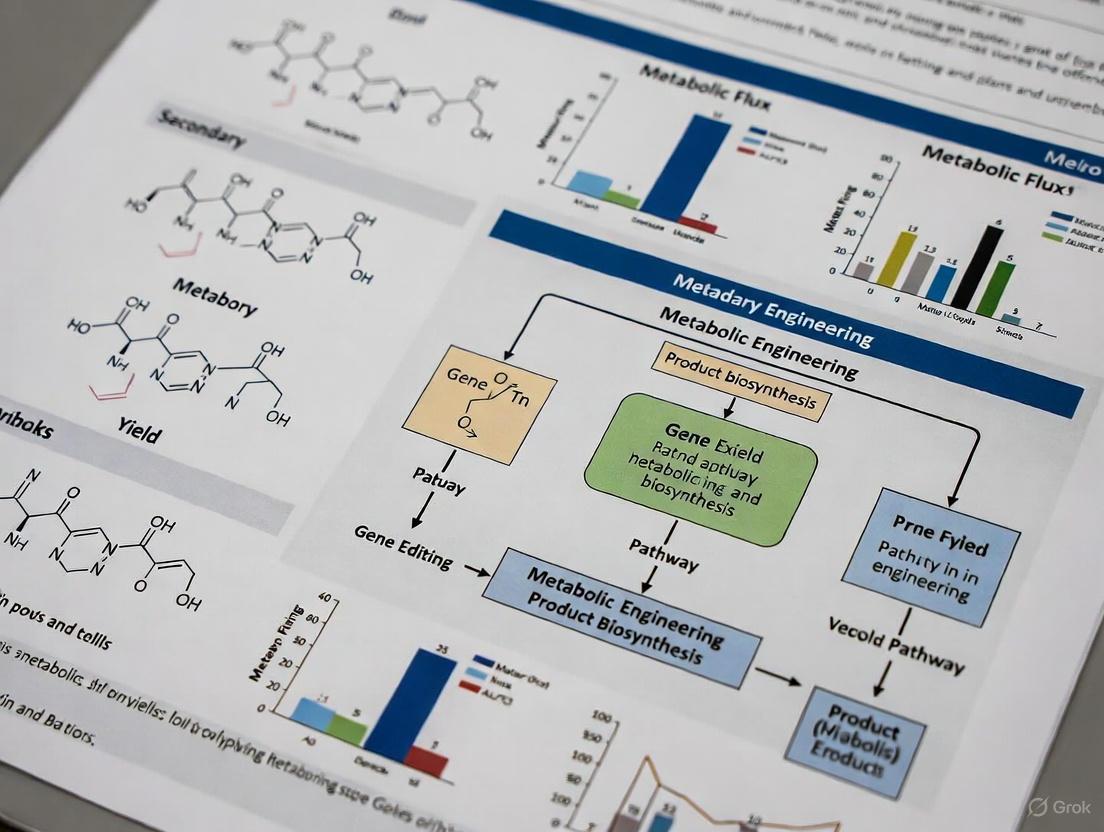

The diagram below illustrates the major biosynthetic pathways for terpenoids and phenolics, highlighting the key intermediates and their subcellular compartmentalization.

The Defense Arsenal: Ecological Roles of Secondary Metabolites

As sessile organisms, plants rely heavily on chemical warfare, mediated by SMs, to defend against biotic and abiotic stresses [1] [7]. These defenses can be constitutive (always present) or inducible (synthesized or activated upon attack) [7]. The roles of SMs in defense are multifaceted and highly effective.

Defense Against Pathogens: SMs act as phytoalexins and phytoanticipins, providing direct antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of bacteria and fungi [7]. For instance, the phenolic compound resveratrol from grapevines exhibits antifungal properties by disrupting the cellular ultrastructure of Botrytis cinerea [7]. Similarly, glucosinolates in Brassicales and their hydrolysis products (e.g., sulforaphane) can inhibit virulence factors in pathogens like Pseudomonas syringae by suppressing the expression and assembly of its type III secretion system (T3SS) [7].

Deterrence of Herbivores: Many SMs serve as potent feeding deterrents or toxins against insects and larger herbivores. Alkaloids like morphine and caffeine can be toxic or repellent [5] [2]. The diterpenoid kauralexin A3 not only has antifungal activity but also displays significant feeding deterrent activity against the European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) [7].

Indirect Defense and Signaling: Plants release Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), which can directly inhibit pathogens or attract natural enemies of herbivores [7]. Furthermore, some SMs are crucial for regulating the plant's own immune responses. They can act as signaling molecules to prime systemic defenses, such as Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) and Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR), enhancing the plant's ability to resist subsequent infections [7] [8]. For example, Trichoderma-derived SMs can activate ISR in plants, providing broad-spectrum resistance [8].

Table 2: Defense Functions of Key Secondary Metabolite Classes

| Metabolite Class | Direct Antibiotic/Antifungal Action | Antioxidant Activity | Herbivore Deterrence | Indirect Defense (VOCs, Signaling) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Terpinen-4-ol (antifungal) [7] | Carotenoids (quench ROS) [5] | Kauralexins [7] | Carvacrol, Thymol (VOCs) [7] |

| Phenolics | Resveratrol, Flavonoids [7] | Flavonoids, Tannins (radical scavenging) [5] [3] | Tannins (reduce palatability) [5] | Salicylic Acid (SAR signal) [7] |

| Alkaloids | Berberine (antibacterial) [5] | – | Morphine, Caffeine (toxic/deterrent) [5] [2] | – |

| S-containing | Allicin (antibacterial) [7] | Glucosinolates [5] | Glucosinolates [5] | – |

Therapeutic Potential: Secondary Metabolites in Medicine

The biological activities of SMs that evolved for ecological interactions have made them an invaluable source of pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and lead compounds for drug development [4] [3] [6]. Their structural diversity provides unique scaffolds that often interact with biologically relevant molecular targets.

Anticancer Agents: Numerous plant SMs are used directly as chemotherapeutic drugs or as precursors for synthetic analogs. Paclitaxel (Taxol), a diterpenoid from the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia), stabilizes microtubules and is a frontline treatment for ovarian, breast, and lung cancers [3] [6]. Pristimerin and tingenone, quinonemethide triterpenoids from Celastraceae species, exhibit potent cytotoxicity and are under investigation for their antitumor properties [4].

Antimicrobials and Antiparasitics: The sesquiterpene lactone artemisinin, from Artemisia annua, is a cornerstone of modern malaria treatment, especially against drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum [4] [6]. Similarly, secondary metabolites from microbial sources, such as those produced by Trichoderma fungi (e.g., peptaibols, pyrones), display strong antifungal and antibacterial effects, highlighting their potential as novel antibiotics [9] [8].

Treatment of Chronic Diseases: Beyond infectious diseases and cancer, SMs show promise in managing chronic conditions. Silymarin, a flavonoid complex from milk thistle (Silybum marianum), is used for its hepatoprotective and antidiabetic effects [3]. Lignans from flaxseed and sesame are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and certain hormone-related cancers due to their antioxidant and phytoestrogenic activities [3]. The anti-inflammatory properties of flavonoids and saponins are also being harnessed to develop treatments for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease [4] [3].

Table 3: Clinically Relevant Secondary Metabolites and Their Applications

| Secondary Metabolite | Class | Natural Source | Clinical/Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisinin | Sesquiterpene lactone | Artemisia annua (plant) [4] | First-line treatment for malaria [4] [6] |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Diterpenoid | Taxus brevifolia (Pacific Yew) [6] | Treatment of ovarian, breast, and lung cancers [3] [6] |

| Morphine | Alkaloid | Papaver somniferum (Opium Poppy) [5] [6] | Potent analgesic for severe pain [5] [6] |

| Silymarin | Flavonoid complex | Silybum marianum (Milk Thistle) [3] | Hepatoprotective; treatment of liver disorders [3] |

| Digoxin/Digitoxin | Cardenolide | Digitalis purpurea (Foxglove) [6] | Treatment of congestive heart failure and arrhythmia [6] |

| (-)-Rabdosiin | Lignan | Ocimum tenuiflorum (Holy Basil) [4] | Selective proapoptotic activity against cancer cell lines (MCF-7, SKBR3, HCT-116) [4] |

| Cordycepin | Nucleoside analogue | Cordyceps militaris (fungus) [4] | Xanthine oxidase inhibitor; potential for hyperuricemia treatment [4] |

Experimental and Computational Toolkit for Research

Advancing the field of secondary metabolite engineering requires a sophisticated suite of experimental and computational tools. The following section details key methodologies and resources for the discovery, analysis, and production of SMs.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Genome Mining for Novel Metabolites

Genome mining is a powerful, hypothesis-driven approach to discover novel SMs from culturable and unculturable microorganisms without the need for traditional activity-guided fractionation [10].

Genome Sequencing and Assembly: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from the target microbe or environmental sample. Perform whole-genome sequencing using a long-read platform (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to facilitate accurate assembly of repetitive biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) regions. Assemble reads into contiguous sequences (contigs).

Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) Identification: Annotate the assembled genome using specialized software tools. The most current and comprehensive platform is PRISM 4 (PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolomes), which uses 1,772 hidden Markov models (HMMs) to identify BGCs for 16 different classes of secondary metabolites, including nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, terpenes, and β-lactams [10]. Input the genome sequence into the PRISM 4 web application or standalone software.

In Silico Chemical Structure Prediction: PRISM 4 analyzes the identified BGCs and employs 618 in silico tailoring reactions to predict the complete chemical structure of the encoded metabolite. The algorithm considers all possible enzymatic reactions and their combinations, generating a set of plausible chemical structures [10]. The accuracy of predictions is validated by calculating the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) between predicted and known structures for reference BGCs.

Biological Activity Prediction: To prioritize BGCs for experimental characterization, employ machine-learning models trained on the predicted chemical structures. These models can predict the likely biological activity (e.g., antibacterial, anticancer) of the encoded molecule based on its structural features and similarity to known bioactive compounds [10].

Heterologous Expression and Validation: Clone the entire predicted BGC into a suitable bacterial or fungal expression host (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor, Aspergillus nidulans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae) using transformation-associated recombination (TAR) or other large-fragment cloning techniques. Ferment the engineered host and analyze the culture extract using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to detect the production of the novel metabolite. Compare the observed mass and fragmentation pattern with the in silico prediction. Isolate the compound using preparative chromatography for full structural elucidation by NMR and subsequent biological activity assays.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Secondary Metabolite Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PRISM 4 Software | Comprehensive prediction of secondary metabolite structures from genomic DNA sequences [10]. | In silico identification and structural prediction of novel antibiotics from bacterial genomes. |

| antiSMASH Software | Detection and annotation of biosynthetic gene clusters in genomic data [10]. | Comparative genomics and initial BGC screening to complement PRISM 4 analysis. |

| Heterologous Expression Hosts | Production of secondary metabolites from cloned BGCs in a controllable genetic background. | Cloning of a cryptic BGC from an unculturable bacterium into Streptomyces coelicolor for compound production [10]. |

| LC-HRMS (Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry) | Separation, detection, and accurate mass determination of metabolites in complex mixtures. | Metabolite profiling of plant extracts or microbial fermentation broths; dereplication of known compounds. |

| HPLC-PDA (with Photodiode Array Detection) | Analytical and preparative separation of compounds with UV-Vis spectral analysis. | Quantification of specific metabolites like pristimerin and tingenone in plant root extracts [4]. |

Visualizing the Genome Mining Workflow

The following diagram outlines the integrated computational and experimental workflow for the discovery of novel secondary metabolites via genome mining, as described in the protocol above.

Secondary metabolites represent a critical interface between an organism and its environment, serving as sophisticated weapons in defense and a treasure trove for medicine. Their intricate chemical structures, born from evolutionarily refined biosynthetic pathways, confer a vast range of biological activities that can be harnessed to protect crops and combat human disease. For researchers in the field of metabolite engineering, a deep understanding of these compounds—from their fundamental classifications and ecological roles to the advanced computational and experimental tools used for their discovery—is indispensable. The integration of modern genomics, predictive bioinformatics, and synthetic biology is poised to unlock the full potential of secondary metabolites, enabling the rational engineering of plants and microbes for the sustainable production of novel bioprotectants and pharmaceuticals. This knowledge base is the foundation upon which the next generation of biocontrol strategies and life-saving drugs will be built.

Secondary metabolites are organic compounds that are not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of plants but play crucial roles in defense, environmental interaction, and adaptation. These specialized compounds have garnered significant attention from researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals due to their vast pharmacological potential and ecological importance. Within the context of secondary metabolite engineering in plants and microbes, three major classes stand out for their structural diversity and biological significance: terpenoids, alkaloids, and phenylpropanoids. These compounds represent nature's chemical arsenal, with complex biosynthetic pathways that have evolved over millions of years. The engineering of these pathways in heterologous systems presents a promising strategy for sustainable production of high-value compounds, reducing reliance on traditional plant extraction methods that are often limited by low yields and environmental concerns. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core biosynthetic pathways for these three metabolite classes, recent advances in their elucidation, and emerging strategies for their engineering in microbial and plant systems.

Terpenoid Biosynthesis

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, represent the largest and most chemically diverse class of natural products, with over 80,000 identified structures [11]. These compounds are essential for plant functions including growth regulation, defense, and ecological interactions, and have significant industrial applications in pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, flavors, fragrances, and increasingly as biofuels [12] [13]. All terpenoids are derived from two universal five-carbon precursors: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [12]. Plants employ two distinct pathways for the production of these precursors, localized in different subcellular compartments, providing a fundamental carbon skeleton for the synthesis of a wide variety of terpenoid compounds [12].

The mevalonate (MVA) pathway operates primarily in the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum, with potential peroxisomal contributions, and utilizes acetyl-CoA as the starting substrate [12] [13]. This pathway consumes three acetyl-CoA molecules, three ATP equivalents, and two NADPH molecules to yield a single IPP molecule through a six-enzyme cascade [12]. A pivotal rate-limiting step is the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, catalyzed by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) within the ER membrane [12].

In contrast, the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway occurs exclusively within plastids and utilizes pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) as starting materials [12] [13]. This pathway involves seven enzymatic reactions that convert these precursors into IPP and DMAPP, consuming three ATP and three NADPH molecules in the process [12]. The first committed step, catalyzed by 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), represents another crucial regulatory point in terpenoid biosynthesis [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Terpenoid Precursor Pathways

| Feature | MVA Pathway | MEP Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Subcellular Localization | Cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisomes | Plastids |

| Initial Substrates | Acetyl-CoA | Pyruvate + glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) |

| Energy Cofactors Consumed | 3 ATP, 2 NADPH | 3 ATP, 3 NADPH |

| Key Regulatory Enzymes | HMG-CoA reductase (HMGR) | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) |

| Primary End Products | Sesquiterpenes (C15), triterpenes (C30) | Monoterpenes (C10), diterpenes (C20), tetraterpenes (C40) |

| Environmental Response | Increased activity in darkness | Increased activity in light |

Formation of Terpenoid Backbones

The structural diversity of terpenoids begins with the action of isoprenyl diphosphate synthases (IDSs), which catalyze the sequential condensation of isoprenoid units to form prenyl diphosphate metabolites of varying chain lengths [12]. The initial condensation of one DMAPP and one IPP, catalyzed by geranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GPPS), yields geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), the precursor of monoterpenes (C10) [12]. Further elongation via farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (FPPS) incorporates an additional IPP with GPP to form farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), serving as the backbone of sesquiterpenes (C15) [12]. Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) catalyzes the addition of three IPPs to one DMAPP, generating geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP), a precursor for diterpenes (C20) [12]. FPP and GGPP can then undergo further polymerization to form triterpenes (C30) and tetraterpenes (C40), respectively [12].

Terpene synthases (TPS) then process these linear intermediates, generating a structurally diverse array of terpenes through stereospecific cyclization and rearrangement reactions [12]. Further structural elaboration occurs via oxidative modifications mediated by cytochrome P450 oxygenases (CYP450s), which significantly modulate the functional diversity of terpenoids [12]. The remarkable structural diversity of terpenoids is further enhanced by variations in enzyme architecture and alternative catalytic mechanisms that generate unconventional terpene scaffolds, including cis-configured intermediates produced by specialized cis-isoprenoid diphosphate synthases [12].

Figure 1: Terpenoid Biosynthesis Network Showing MVA and MEP Pathways

Engineering Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Recent advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology have enabled the reconstruction and optimization of terpenoid pathways in microbial and plant systems, significantly increasing production yields [13] [11]. Several key strategies have emerged:

Host System Selection: Prokaryotic hosts like Escherichia coli have become preferred platforms for terpenoid biosynthesis due to rapid proliferation, clear metabolic background, and mature genetic manipulation systems [13]. Eukaryotic hosts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae offer unique advantages with their natural MVA pathway and endoplasmic reticulum machinery that efficiently facilitates proper folding of plant-derived cytochrome P450 enzymes [13]. Plant chassis like Nicotiana benthamiana provide natural metabolic environments and compartmentalized cells conducive to complex biosynthesis [14] [13].

Critical Enzyme Optimization: Enhanced expression of rate-limiting enzymes through analyses of subcellular compartmentalization, gene expression network modeling, and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms helps remove metabolic bottlenecks [13]. Tissue-specific promoter elements enable spatially precise enrichment of target metabolites, while heterologous co-expression systems of key enzyme genes in MEP and MVA pathways dynamically optimize precursor metabolic flux [13].

Pathway Elucidation Methods: Traditional approaches include iterative identification of gene candidates via correlation of product titers with expressed sequence tags, followed by functional characterization in heterologous production chassis like N. benthamiana [15]. Emerging technologies such as automation, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and combinatorial screening are accelerating the exploration of microbial terpenoid chemical space and strain preparation [15].

Table 2: Terpenoid Engineering in Microbial and Plant Systems

| Engineering Strategy | Experimental Approach | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Host System Engineering | Transformation with terpene synthase genes + precursor pathway optimization | E. coli produced β-farnesene (1.3 g/L) [13] |

| Enzyme Engineering | Directed evolution, rational design, machine-learning guided optimization | Enhanced catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, and stability [15] |

| Pathway Balancing | Modular pathway optimization, promoter engineering, gene copy number adjustment | Improved flux to target terpenoids, reduced accumulation of intermediates [13] |

| Compartmentalization | Targeting enzymes to specific organelles using signal peptides | Enhanced precursor availability, reduced metabolic cross-talk [12] [13] |

| Plant Metabolic Engineering | Stable transformation or transient expression in N. benthamiana | Production of complex terpenoids requiring plant-specific modifications [14] |

Alkaloid Biosynthesis

Structural Diversity and Neuroactive Alkaloids

Alkaloids are nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites with remarkable structural diversity and potent biological activities, particularly notable for their effects on the nervous system [14]. These compounds are classified based on their chemical structures and biosynthetic origins, with significant categories including isoquinoline, indole, tropane, and quinolizidine alkaloids. Among the numerous plant-derived alkaloids with neuroactive properties, huperzine A and galantamine stand out as the only plant-derived alkaloids currently approved and marketed as specific treatments for Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions [14].

Huperzine A, derived from Huperzia serrata (Lycopodiaceae), is a well-known acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI) that has been widely used in traditional Chinese medicine [14]. Galantamine, an alkaloid derived from plants in the Amaryllidaceae family, particularly daffodils (Narcissus spp.), is another crucial AChEI used in Alzheimer's disease treatment [14]. While numerous other plant alkaloids exhibit varying degrees of neuroactive properties, these two represent the most clinically significant examples.

Biosynthetic Pathways of Key Alkaloids

Huperzine A Biosynthesis: The elucidation of the huperzine A biosynthetic pathway has provided crucial insights into the formation of Lycopodium alkaloids and uncovered numerous enzymes with novel functions [14]. Recent studies have identified three novel neofunctionalized α-carbonic anhydrase-like (CAL) enzymes responsible for key Mannich-like condensations that form core carbon-carbon bonds in Lycopodium alkaloids, representing key steps in the construction of their polycyclic skeletons [14]. Through transcriptome analysis and enzyme characterization, researchers have identified key enzymes such as CAL-1 and CAL-2, which promote crucial annulation reactions [14]. The pathway proceeds through stereospecific modifications and scaffold tailoring, involving additional enzymes like Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases that introduce oxidation steps crucial for the final bioactive form of huperzine A [14].

Galantamine Biosynthesis: The galantamine biosynthetic pathway begins with the key precursor 4′-O-methylnorbelladine (4OMN), followed by oxidative coupling catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes such as NtCYP96T6 [14]. This enzyme facilitates the para-ortho (p-o') oxidative coupling necessary to produce the galantamine skeleton. Subsequent methylation and reduction steps, catalyzed by NtNMT1 and NtAKR1 respectively, complete the biosynthesis [14]. The discovery of this pathway has profound implications for synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, particularly since galantamine is currently sourced primarily from natural populations of daffodils [14].

Figure 2: Biosynthetic Pathways of Neuroactive Alkaloids Huperzine A and Galantamine

Engineering Challenges and Future Directions

The elucidation of huperzine A and galantamine biosynthetic pathways underscores the complexity and elegance of plant specialized metabolism [14]. However, several significant challenges remain in the engineering of these compounds:

Functional Understanding: The in vivo functional roles of these alkaloids in plants are not fully understood, though it is speculated that they serve as defense metabolites against herbivores [14]. The regulatory mechanisms governing their production remain elusive, and further research into their ecological roles could provide important insights into the evolution of medicinal plants and their biosynthetic pathways [14].

Scalability Issues: While transient expression in N. benthamiana has demonstrated proof-of-concept for alkaloid biosynthesis, translating these findings into industrial-scale production requires optimization of gene expression, precursor supply, and enzymatic activity in microbial or plant-based platforms [14]. Optimizing precursor supply, enhancing enzyme activity, and achieving high-yield production in heterologous systems represent critical bottlenecks.

Technical Solutions: Microbial synthetic biology platforms, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris, offer promising avenues for large-scale production due to their scalability and ease of genetic manipulation [14]. Advances in CRISPR-based genome editing, multi-gene pathway assembly, and metabolic flux optimization are pivotal for overcoming current limitations [14].

Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis

Pathway Architecture and Metabolic Branches

The phenylpropanoid pathway serves as a key target for climate-resilient crop development, being the precursor to over 8,000 metabolites, including flavonoids, lignin compounds, and their derivatives [16]. These metabolites play essential roles in biotic and abiotic stress tolerance, making them crucial for plant survival and adaptation [16]. The pathway begins with aromatic amino acids derived from the shikimate pathway, which itself originates from intermediates of glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway [16].

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) serves as the gateway enzyme to phenylpropanoid metabolism, catalyzing the deamination of phenylalanine to form cinnamic acid [16]. This reaction opens the route to several glycosylation, acylation, hydroxylation, and methylation reactions that ultimately form the vast array of phenylpropanoid metabolites [16]. In some grasses, tyrosine also serves as a starting point, diverging from phenylalanine at the arogenate step but reconverging to yield p-coumarate, a central precursor to coumaroyl CoA [16].

The pathway branches into two major routes producing numerous lignin- and flavonoid-related metabolites [16]. Lignin, a heterogeneous phenolic polymer, is the second most abundant polymer after cellulose, forming 30% of the earth's organic carbon in the biosphere [16]. The heterogeneity of lignin results from its polymerization from various hydroxycinnamoyl alcohol derivatives, and it is deposited in cell walls of vascular plants, conferring many stress tolerance traits [16]. Flavonoid metabolism represents the second major branch, producing over 6,000 polyphenolic metabolites characterized by a C6-C3-C6 diphenylpropane skeleton where three carbon chains link two aromatic rings [16].

Biological Functions and Stress Responses

Phenylpropanoid-derived metabolites play indispensable roles in plant-environment interactions, particularly in response to various stressors:

Biotic Stress Resistance: Phenylpropanoids contribute significantly to plant defense against pathogens and herbivores. Lignin forms physical barriers against pathogen invasion, while various flavonoids and phenolic compounds exhibit direct antimicrobial and antifeedant activities [16]. Specific phenylpropanoids also function as signaling molecules in plant-microbe interactions, regulating relationships between plants and beneficial microorganisms [1].

Abiotic Stress Tolerance: These metabolites provide crucial protection against environmental challenges including drought, temperature extremes, UV radiation, and heavy metal toxicity [16]. Their antioxidant properties enable them to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) that accumulate under stressful conditions, preventing oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA [16]. Flavonoids particularly contribute to UV protection through their light-absorbing properties.

Structural Support: Lignin provides mechanical support for plant growth and promotes water and mineral uptake and partitioning in plants [16]. This structural function is essential for normal development and becomes particularly important under stress conditions where mechanical integrity is challenged.

Table 3: Major Phenylpropanoid Classes and Their Functions

| Class | Representative Compounds | Primary Functions | Stress Response Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Phenylpropanoids | Cinnamic, p-coumaric, ferulic, caffeic acids | Pathway intermediates, antimicrobial compounds | Immediate defense response, signaling molecules |

| Flavonoids | Flavones, flavonols, anthocyanins, isoflavonoids | Pigmentation, UV protection, antioxidant activity | ROS scavenging, UV screening, microbial signaling |

| Lignin | Heterogeneous polymer from hydroxycinnamyl alcohols | Structural support, mechanical strength | Physical barrier against pathogens, drought adaptation |

| Coumarins | Scopoletin, umbelliferone | Antimicrobial, allelopathic compounds | Iron mobilization, pathogen inhibition |

| Stilbenoids | Resveratrol, piceid | Phytoalexins, antioxidant compounds | Defense against fungal pathogens, oxidative stress protection |

Regulation and Engineering Strategies

The phenylpropanoid pathway is regulated at multiple levels, including transcriptional, post-transcriptional, post-translational, and epigenetic modifications [16]. Understanding these regulatory mechanisms provides opportunities for metabolic engineering aimed at enhancing the production of valuable phenylpropanoids or improving plant stress resilience.

Recent research has comprehensively elucidated the molecular regulation of phenylpropanoids, their diversity, and plasticity [16]. The role of phenylpropanoid metabolites in biotic and abiotic stress interactions is continuously changing the face of climate-resilient germplasm development [16]. Engineering approaches include:

Transcription Factor Modulation: Manipulation of key transcription factors that regulate multiple genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway can simultaneously enhance flux through multiple branches.

Enzyme Engineering: Optimization of key enzymes, particularly those at branch points, can redirect flux toward desired compounds while reducing competition between pathways.

Synthetic Biology Approaches: Reconstruction of specific phenylpropanoid pathways in microbial hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae enables sustainable production of high-value compounds without the need for plant extraction [17] [15].

Figure 3: Phenylpropanoid Biosynthetic Pathway and Branching to Lignin and Flavonoids

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Secondary Metabolite Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Heterologous Host Systems | Platform for pathway reconstruction and optimization | Escherichia coli [13], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [15] [14], Nicotiana benthamiana [15] [14] |

| Enzyme Engineering Tools | Optimization of catalytic efficiency and specificity | Machine-learning guided directed evolution [15], rational design, site-saturation mutagenesis |

| Analytical Platforms | Metabolite profiling and quantification | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, NMR spectroscopy [17] |

| Pathway Elucidation Methods | Identification of biosynthetic genes and enzymes | Co-expression analysis [17], GWAS [17], protein complex identification [17] |

| Gene Editing Systems | Precise genetic modifications in host organisms | CRISPR-Cas9 [14], TALENs, zinc finger nucleases |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Pathway prediction and enzyme discovery | Genome mining, phylogenetic analysis, molecular docking |

| Synthetic Biology Tools | Multi-gene pathway assembly | Golden Gate assembly, Gibson assembly, yeast assembly |

| Specialized Enzymes | Key catalysts for specific reactions | Cytochrome P450s [12] [14], terpene synthases [12], carbonic anhydrase-like enzymes [14] |

The comprehensive understanding of terpenoid, alkaloid, and phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathways has advanced significantly in recent years, driven by interdisciplinary approaches combining biochemistry, molecular biology, and synthetic biology. The elucidation of these complex metabolic networks not only deepens our fundamental knowledge of plant chemistry but also opens unprecedented opportunities for sustainable production of high-value compounds through metabolic engineering.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, the continued discovery and characterization of novel enzymes with unique catalytic properties will expand the toolbox available for pathway engineering. Second, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches will accelerate enzyme optimization, pathway design, and strain development. Third, the development of more sophisticated regulatory systems for fine-tuning metabolic flux will enhance production yields while maintaining host viability. Finally, the exploration of non-model plant species and their specialized metabolisms will likely reveal new biochemical pathways and compounds with potential pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

As synthetic biology tools become more advanced and accessible, the engineering of plant secondary metabolic pathways in microbial and plant systems will play an increasingly important role in the sustainable production of medicinal compounds, specialty chemicals, and agricultural products. This transition from traditional extraction to biotechnology-based production represents a paradigm shift in how we harness plant chemical diversity, with significant implications for drug development, agriculture, and industrial biotechnology.

Microbial secondary metabolites represent a rich source of bioactive compounds with critical applications in medicine and industry. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the major biosynthetic pathways for three key metabolite classes: antibiotics, pigments, and immunomodulators. Within the broader context of secondary metabolite engineering in plants and microbes, we examine the enzymatic machinery, regulatory networks, and precursor systems that govern the production of these valuable compounds. Recent advances in genetic engineering, pathway optimization, and synthetic biology are discussed alongside detailed experimental methodologies to support research and development efforts. The integration of multi-omics data and computational modeling is creating new paradigms for the discovery and optimization of microbial metabolites with enhanced bioactivities and production efficiencies.

Microbial secondary metabolites are organic compounds produced through specialized metabolic pathways that are not essential for basic growth but provide significant ecological advantages and possess valuable bioactivities. The engineering of these pathways in both plants and microbes has emerged as a critical strategy for enhancing the production of pharmaceuticals, colorants, and therapeutic agents [1]. Actinomycetes, particularly Streptomyces species, are prolific producers of secondary metabolites, accounting for over 76% of known bioactive compounds including many clinically used antibiotics and immunosuppressants [18] [19].

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites typically utilizes precursors derived from primary metabolism and occurs through dedicated pathways that are often clustered in the microbial genome. Key precursor pathways include the acetate-malonate pathway for polyketides, the mevalonate pathway for terpenoids, the shikimate pathway for aromatic compounds, and various amino acid incorporation pathways [19]. Understanding these fundamental biosynthetic routes, their regulatory mechanisms, and the experimental approaches for their manipulation forms the foundation of metabolic engineering for enhanced compound production.

Antibiotic Biosynthetic Pathways and Engineering

Major Antibiotic Classes and Biosynthetic Origins

Antibiotics from actinomycetes encompass diverse structural classes including aminoglycosides, macrolides, phenazines, indoles, and carbazoles [19]. These compounds are synthesized through complex enzymatic pathways that are genetically clustered, facilitating both study and manipulation. Polyketide antibiotics such as actinorhodin are assembled by polyketide synthases (PKSs) using acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA as precursors, while non-ribosomal peptide antibiotics are synthesized by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) that incorporate amino acid building blocks.

Table 1: Major Antibiotic Classes from Actinomycetes and Their Biosynthetic Pathways

| Antibiotic Class | Example Compounds | Biosynthetic Pathway | Key Precursors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Streptomycin, Neomycin | Sugar biosynthesis & modification | Glucose, amino acids |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin, Rapamycin | Polyketide | Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA, Methylmalonyl-CoA |

| Enediyne Macrolides | Calicheamicin | Polyketide with enediyne core | Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA |

| Phenazines | Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid | Shikimate | Chorismic acid |

| Indoles and Carbazoles | Staurosporine | Tryptophan-derived | Tryptophan |

| β-Lactams | Penicillins, Cephalosporins | Amino acid | L-α-aminoadipic acid, L-cysteine, L-valine |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Engineering Strategies

Antibiotic biosynthesis is tightly regulated by both pathway-specific and global regulatory networks. Pathway-specific regulators such as TetR-family proteins, LAL (Large ATP-binding regulators of the LuxR family), and SARP (Streptomyces Antibiotic Regulatory Proteins) family transcription factors directly control the expression of biosynthetic gene clusters [19]. For example, in Streptomyces virginiae, the pathway-specific regulatory gene vmsR positively regulates virginiamycin production, while in Streptomyces rapamycinicus, knockout of the regulatory gene rapY enhanced rapamycin yield by 3.7-fold [19].

Global regulators influence multiple metabolic pathways and morphological differentiation. Recent research has highlighted the value of regulatory genes as beacons for discovering and prioritizing biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in Streptomyces [20]. Protein domain architecture analysis of 128,993 potential regulators from 440 complete Streptomyces genomes revealed that subsets of SARP and LuxR families are strongly associated with biosynthetic pathways encoding bioactive compounds [20].

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

| Method | Mechanism | Application Example | Efficiency/Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Gene Modification | Overexpression or deletion of pathway-specific regulators | Overexpression of sanmR0484 in S. dichotomus; deletion of gbnR in S. venezuelae | Activation of silent type I polyketide cluster; identification of gaburedins A-F [19] |

| Strong Promoter Introduction | Heterologous expression under constitutive strong promoters | Expression of phenazine cluster under ermE* promoter in S. coelicolor M512a | Production of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid and novel glutamine conjugate [19] |

| Small Molecule Elicitors | Addition of epigenetic modifiers or antibiotics at subinhibitory concentrations | Use of β-lactams, histone deacetylase inhibitors, heavy metal ions | Activation of various silent gene clusters; diversified secondary metabolite production [19] |

| Precursor Enhancement | Engineering precursor supply pathways | Modulation of acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, or amino acid biosynthesis | Increased flux through target pathways; enhanced antibiotic yields [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Optimization of Antibiotic Production via Precursor Engineering

Objective: Enhance antibiotic yield by engineering precursor supply pathways in actinomycetes.

Methodology:

- Identification of Key Precursors: Analyze antibiotic structure to determine primary building blocks (e.g., acetyl-CoA for polyketides, specific amino acids for NRPS-derived compounds).

- Genetic Modification:

- Amplify genes encoding rate-limiting enzymes in precursor biosynthesis (e.g., acetyl-CoA carboxylase for malonyl-CoA supply).

- Clone genes into integrative or replicative expression vectors under control of strong, constitutive promoters (e.g., ermE*).

- Introduce constructs into production host via PEG-mediated protoplast transformation or conjugation.

- Fermentation Optimization:

- Inoculate modified strains in optimal production media (e.g., R5, SFM, or YEME for streptomycetes).

- Cultivate at appropriate temperature (28-30°C) with agitation (200-250 rpm) for 5-14 days.

- Analytical Quantification:

- Extract metabolites using appropriate solvents (ethyl acetate, butanol).

- Analyze antibiotic titers via HPLC-MS with authentic standards.

- Quantify precursor pools using LC-MS/MS with stable isotope-labeled internal standards.

Expected Outcomes: Engineered strains typically show 1.5 to 4-fold increases in antibiotic production compared to wild-type strains when precursor supply is successfully enhanced [19].

Pigment Biosynthesis Pathways and Applications

Structural Diversity and Biosynthetic Classification

Microbial pigments encompass diverse chemical classes including carotenoids, quinones, azaphilones, melanins, and flavonoids [21] [22]. These compounds are classified based on their chemical structures, colors, and biosynthetic origins. Carotenoids such as β-carotene and astaxanthin are terpenoids synthesized via the mevalonate (MVA) or methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, while quinones like actinorhodin and juglomycin are polyketides derived from the acetate-malonate pathway [21].

Table 3: Major Microbial Pigment Classes and Their Properties

| Pigment Class | Representative Pigments | Color | Microbial Sources | Biosynthetic Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | β-Carotene, Astaxanthin, Lycopene | Yellow, Orange, Red | Blakeslea trispora, Rhodotorula spp. | MEP/MVA pathways |

| Quinones | Actinorhodin, Juglomycin, Naphthoquinone | Blue, Yellow | Streptomyces spp. | Polyketide |

| Azaphilones | Monascin, Rubropunctatin | Yellow, Orange, Red | Monascus spp. | Polyketide-amino acid hybrid |

| Melanins | Eumelanin, Allomelanin | Brown, Black | Various fungi and bacteria | Tyrosine-derived |

| Pyrroles | Prodigiosin, Tambjamine | Red, Pink, Yellow | Serratia spp., Pseudoalteromonas | Bipyrrole/tripyrrole assembly |

| Flavins | Riboflavin | Yellow | Ashbya gossypii | Purine precursor |

Optimization of Pigment Production: A Case Study

Recent research with Streptomyces parvulus strain S145 demonstrates a systematic approach to optimizing pigment production [18]. A Plackett-Burman design was first used to identify significant factors influencing pigment yield, followed by optimization using a Box-Behnken design. The key findings were:

- Significant Factors: Temperature, incubation time, and agitation speed were identified as the most influential parameters.

- Optimal Conditions: 30°C, 50 rpm agitation, and 7-day incubation yielded a pigment concentration of 465.3 μg/mL.

- Nutrient Optimization: Soluble starch as carbon source and yeast extract-malt extract as nitrogen source supported maximal pigment production.

- Chemical Characterization: LC-MS analysis revealed three 1,4-naphthoquinone-containing compounds—juglomycin Z, WS-5995B, and naphthopyranomycin—as the main constituents.

This optimized fermentation model enhances pigment yield while reducing resource consumption, demonstrating the value of systematic optimization approaches [18].

Experimental Protocol: Fermentation Optimization for Microbial Pigments

Objective: Maximize pigment production through systematic optimization of fermentation parameters.

Methodology:

- Initial Screening:

- Employ Plackett-Burman design to evaluate multiple factors (temperature, pH, carbon/nitrogen sources, agitation, incubation time).

- Use 12-20 run designs to identify statistically significant factors (p < 0.05).

- Response Surface Methodology:

- Implement Box-Behnken or Central Composite Design with 3-5 critical factors identified from screening.

- Include 15-30 experimental runs with center points for error estimation.

- Analytical Methods:

- Extract pigments from biomass or supernatant using ethyl acetate.

- Quantify pigment concentration via spectrophotometry at characteristic wavelengths.

- Characterize chemical composition using HPLC-DAD and LC-MS.

- Validation:

- Conduct verification experiments at predicted optimal conditions.

- Compare experimental yields with model predictions.

Expected Outcomes: Typically 2-5 fold increases in pigment yield compared to unoptimized conditions, with comprehensive understanding of critical parameter interactions [18].

Immunomodulatory Metabolites and Their Mechanisms

Major Classes and Biosynthetic Pathways

Immunomodulatory metabolites from microbes include short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acid derivatives, tryptophan metabolites, polyamines, and specialized lipids [23] [24]. These compounds are primarily generated through microbial transformation of dietary components and host-derived precursors, creating a complex network of immunologically active molecules.

Table 4: Immunomodulatory Microbial Metabolites and Their Activities

| Metabolite Class | Key Examples | Producing Microbes | Biosynthetic Pathway | Immunomodulatory Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate | Clostridium, Bacteroides | Dietary fiber fermentation | Promote Treg differentiation, enhance barrier function, inhibit HDAC [23] |

| Bile acid derivatives | Deoxycholic acid, Lithocholic acid | Clostridium, Bacteroides | 7α-dehydroxylation of primary bile acids | Activate FXR, TGR5; modulate Treg/Th17 balance [24] |

| Tryptophan metabolites | Indole-3-propionic acid, Kynurenine | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Tryptophan degradation via indole/kynurenine pathways | Activate AhR; promote IL-22 secretion; Treg induction [23] |

| Polyamines | Putrescine, Spermidine, Spermine | Bacteroides fragilis | Arginine/ornithine decarboxylation | Regulate macrophage polarization; control T-cell fate [23] |

| Lipid mediators | Conjugated linoleic acids | Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | Linoleic acid biotransformation | Suppress NF-κB signaling via PPARγ [23] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Immune Regulation

Immunomodulatory metabolites exert their effects through multiple receptor systems and signaling pathways:

- SCFAs activate G protein-coupled receptors (GPR41, GPR43, GPR109A) and inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs), leading to altered gene expression in immune cells [23]. Butyrate promotes regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation through enhanced acetylation of the Foxp3 promoter region.

- Bile acid derivatives engage nuclear receptors (FXR) and membrane receptors (TGR5), influencing cytokine expression and barrier function [24]. Specific secondary bile acids such as 3-oxoLCA inhibit Th17 cell differentiation, while isoalloLCA promotes Treg generation [23].

- Tryptophan metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), leading to IL-22 production and enhanced mucosal defense [23]. The balance between the indole pathway (microbial) and kynurenine pathway (host) significantly influences immune polarization.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Immunomodulatory Activity

Objective: Evaluate the immunomodulatory potential of microbial metabolites in macrophage models.

Methodology:

- Metabolite Preparation:

- Purify metabolites from microbial culture supernatants using preparative HPLC.

- Verify purity and structure by NMR and MS.

- Prepare stock solutions in DMSO or PBS.

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Maintain murine macrophage cell line (e.g., RAW 264.7) or primary bone marrow-derived macrophages.

- Pre-treat cells with metabolites (1-100 μM) for 2-6 hours.

- Stimulate with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 18-24 hours.

- Immunological Assays:

- Quantify cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12) via ELISA.

- Analyze surface marker expression (CD80, CD86, MHC-II) by flow cytometry.

- Assess phagocytic activity using fluorescent beads or opsonized particles.

- Mechanistic Studies:

- Evaluate receptor binding via competitive assays.

- Analyze signaling pathway activation (NF-κB, MAPK, STAT) by western blot.

- Assess epigenetic modifications (histone acetylation) through ChIP assays.

Expected Outcomes: Identification of metabolite-mediated cytokine modulation (e.g., TNF-α inhibition up to 36.9% and IL-10 stimulation up to 38.4% as reported for Streptomyces parvulus pigment fraction [18]).

Pathway Engineering and Synthetic Biology Approaches

Regulatory Gene Manipulation for Pathway Activation

A key strategy for enhancing secondary metabolite production involves the manipulation of regulatory genes that control biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Research has demonstrated that regulatory genes serve as effective beacons for the discovery and prioritization of BGCs in Streptomyces [20]. Protein domain architecture analysis of regulators has revealed strong associations between specific regulator families (particularly SARP and LuxR families) and biosynthetic pathways encoding bioactive compounds. This approach enabled the discovery of 82 putative SARP-associated BGCs that escaped detection by state-of-the-art bioinformatics software [20].

Experimental Protocol: Regulatory Gene Overexpression for Metabolite Enhancement

Objective: Activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters or enhance metabolite production through regulatory gene overexpression.

Methodology:

- Regulator Identification:

- Analyze target BGC for pathway-specific regulatory genes.

- Alternatively, identify global regulators through comparative genomics.

- Vector Construction:

- Amplify regulatory gene with native RBS.

- Clone into integrative (e.g., pSET152 derivatives) or replicative (e.g., pIJ86) vectors under strong constitutive promoters (ermE, kasOp).

- Strain Engineering:

- Introduce construct into wild-type or production host via intergeneric conjugation or protoplast transformation.

- Verify integration and gene expression via PCR and RT-qPCR.

- Metabolite Analysis:

- Culture engineered and control strains in appropriate media.

- Extract metabolites and analyze via HPLC-MS.

- Compare metabolite profiles and quantify target compound production.

Expected Outcomes: Successful activation of silent BGCs with production of novel metabolites, or 2-10 fold enhancement of known metabolites through regulatory overexpression [20] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Microbial Secondary Metabolite Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pSET152, pIJ86, pKC1139 | Integrative and replicative vectors for genetic manipulation in actinomycetes |

| Promoter Systems | ermE, kasOp, TipA | Strong constitutive and inducible promoters for gene expression control |

| Fermentation Media | R5, SFM, YEME, ISP2 | Specialized media for actinomycete growth and secondary metabolite production |

| Chromatography Standards | Actinorhodin, Nystatin, Rapamycin | Authentic standards for HPLC calibration and metabolite identification |

| DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitors | 5-Azacytidine | Epigenetic modifier for silent gene cluster activation |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors | Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid | Epigenetic modifier for altering secondary metabolite profiles |

| Analytical Columns | C18 reverse-phase, HILIC | HPLC and LC-MS separation of diverse metabolite classes |

| Detection Reagents | DPPH, ABTS, MTT | Assay reagents for antioxidant and cytotoxicity testing |

Pathway Visualization and Regulatory Networks

The following diagrams illustrate key biosynthetic pathways and regulatory relationships described in this technical guide.

Diagram 1: Microbial secondary metabolite biosynthesis network showing primary metabolic precursors, major biosynthetic pathways, regulatory systems, and final bioactive products. Regulatory influences are shown with dashed lines.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for microbial secondary metabolite optimization combining fermentation strategies and genetic engineering approaches.

The systematic engineering of major biosynthetic pathways in microbes for antibiotics, pigments, and immunomodulators represents a frontier in biotechnology and drug development. The integration of traditional fermentation optimization with modern genetic tools and computational approaches has dramatically accelerated the discovery and production of valuable secondary metabolites. As our understanding of regulatory networks, precursor supply systems, and pathway architecture continues to deepen, the potential for creating novel compounds with enhanced bioactivities through synthetic biology approaches expands considerably. Future advances will likely focus on the development of more sophisticated heterologous expression platforms, the application of machine learning for pathway prediction and optimization, and the integration of multi-omics data for comprehensive metabolic engineering. These approaches will continue to bridge the fundamental research on secondary metabolite pathways in both plants and microbes with applied biotechnology for human health and industrial applications.

Light as a Key Environmental Regulator of Plant Secondary Metabolism

Secondary metabolites (SMs) are low-molecular-weight organic compounds produced by plants under specific conditions. While not directly involved in fundamental growth and developmental processes, they play crucial roles in plant defense, protection, and regulation, serving as the material basis for the clinically curative effects of medicinal plants [25] [26]. These specialized compounds primarily include phenolics, terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, with over 200,000 chemically diverse structures identified to date [27]. Light environment, with its unique spatial distribution, spectral properties, irradiation intensity, and photoperiod, represents a key environmental factor that profoundly influences the biosynthesis and accumulation of plant secondary metabolites through multidimensional regulatory mechanisms [25] [28].

Understanding the molecular regulatory mechanisms of light signals on plant secondary metabolism holds significant scientific importance and practical value for researchers and drug development professionals. It reveals the molecular networks through which plants adapt to their environment while providing theoretical support for developing light-based technologies to improve crop quality and enhance bioactive compound production in medicinal plants [25] [28]. For the broader context of secondary metabolite engineering in plants and microbes, light regulation offers critical targets for the directed regulation of medicinal components and functional nutrients [25]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the mechanisms of light-regulated SM biosynthesis and provides detailed experimental approaches for manipulating these pathways in research settings.

Molecular Mechanisms of Light-Mediated Regulation

Photoreceptor Systems and Light Signaling Networks

Plants utilize specialized photoreceptor systems to perceive different light wavelengths and initiate signal transduction cascades that regulate secondary metabolic pathways [27]. The major photoreceptors include:

- Phytochromes (PHYA-PHYE): perceive red (620-670 nm) and far-red (690-750 nm) light [27]

- Cryptochromes (CRY1 and CRY2): sense blue/UV-A light (315-400 nm) [27]

- UV Resistance Locus 8 (UVR8): detects UV-B light (280-315 nm) [25] [27]

Upon light perception, these photoreceptors become activated and transmit signals to downstream components, including transcriptional activators and repressors that regulate light-responsive biological processes [27]. Key signaling components include Phytochrome Interacting Factors (PIFs), Elongated Hypocotyl 5 (HY5), B-box proteins (BBX), Constitutive Photomorphogenic 1 (COP1), Suppressor of PHYA-105 (SPA), and De-Etiolated 1 (DET1) [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core light signaling network that integrates with secondary metabolite biosynthesis:

Diagram Title: Core Light Signaling Network Regulating Secondary Metabolism

In darkness, active COP1/SPA and DET1 promote the ubiquitination and degradation of HY5 while stabilizing PIFs, repressing light-mediated responses [27]. Under light conditions, activated photoreceptors suppress COP1/SPA and DET1 activity, resulting in HY5 stabilization and PIF degradation, thereby activating light-responsive genes including those involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis [27].

Spectral Specificity in Regulating Metabolic Pathways

UV Light Regulation

UV radiation activates distinct defense mechanisms in plants, primarily enhancing biosynthesis of flavonoids, phenolics, and terpenoids [25]. The molecular mechanism of UV-mediated regulation involves:

- UV-B (280-315 nm) specifically activates the UVR8 photoreceptor, promoting its combination with COP1 and activating the HY5 transcription factor [25]

- Activated HY5 induces expression of key enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway, including Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL) and Chalcone Synthase (CHS) [25]

- This signaling cascade enhances synthesis and accumulation of anthocyanins and flavonoids, significantly improving plant resistance to oxidative stress [25]

- UV-B also modulates the terpenoid biosynthetic gene network through both the MEP and MVA pathways, dynamically regulating terpenoid diversity and yield [25]

The following experimental data illustrate specific gene expression changes under UV light exposure:

Table 1: UV Light-Mediated Regulation of Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Genes

| Species | UV Type | Exposure Duration | Regulated Genes | Metabolite Changes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brassica napus | UV-B (280-315 nm) | 3 days | ↑PAL, C4H, 4CL, CHS, CHI, F3H, FLS | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, anthocyanin ↑ | [28] |

| Artemisia argyi | UV-B (280-315 nm) | 6 days | ↑HY5, bHLH25, bHLH18, MYB114, MYB12 | Terpenoids, phenolic compounds ↑ | [25] [28] |

| Taxus wallichiana | UV-B (280-320 nm) | 48 hours | ↑Bapt, Dbtnbt; ↓CoA, Ts, Dbat | Cephalomannine, paclitaxel ↑ | [25] [28] |

| Ocimum basilicum | UV-A (365-399 nm) | 14 days (16 h/d) | ↑PAL activity | Total phenolic concentration ↑ | [25] [28] |

| Morus alba | UV-B (280-320 nm) | 15 minutes | ↑PAL, CHI, LAR | Proanthocyanins, moracin N, chalcomaricin ↑ | [25] [28] |

Blue Light Regulation

Blue light (400-495 nm) mediates its effects primarily through cryptochrome and phototropin protein complexes, influencing phenylpropanoid metabolism by acting on transcriptional regulatory networks including HY5 and MYB transcription factors [25] [28]. Experimental evidence demonstrates:

- Blue light treatment of Oryza sativa for 9-14 days upregulates PAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI, F3H, and FLS gene expression, enhancing flavonoid accumulation [28]

- The regulatory mechanism involves cryptochrome-mediated suppression of COP1, leading to HY5 stabilization and subsequent activation of flavonoid biosynthetic genes [27]

- Blue light also influences alkaloid biosynthesis through modulation of hormonal signaling pathways [25]

Red Light Regulation

Red light (620-670 nm) perceived by phytochromes modulates terpenoid production through phytochrome-mediated hormonal signaling pathways that alter endogenous hormone levels [25]. Key mechanisms include:

- Red light treatment (660-665 nm) of wheat sprouts for 4 days upregulates PAL, C4H, and 4CL expression, increasing total phenolic content [28]

- In Atropa belladonna, red LED exposure (620-660 nm) for 35 days upregulates GDHA, At2g42690, PAO5 genes, enhancing hyoscyamine and scopolamine accumulation [28]

- Scots pine under red/far-red LED (660/720 nm) for 40 days shows upregulation of CHS and JAZa, increasing proanthocyanidins and catechins [28]

Experimental Approaches for Light Manipulation

Light Treatment Methodologies

UV Light Treatment Protocols

UV-B Treatment for Enhanced Flavonoid Production:

- Light Source: UV-B fluorescent lamps (280-320 nm) or supplemental UV-B tubes (311 nm) [28]

- Intensity: Varies by species, typically 0.5-3 W/m² biologically effective UV-B

- Exposure Duration: Ranges from 15 minutes for Morus alba to 4 days for Ocimum basilicum [25] [28]

- Treatment Conditions: For Brassica napus, apply 3 days of continuous UV-B exposure [28]

- Post-Treatment Handling: For Morus alba, include 36 hours of dark incubation after 15-minute UV-B irradiation to enhance secondary metabolite biosynthesis [25] [28]

UV-A Treatment Protocol:

- Light Source: UV-A LED (365-399 nm) [28]

- Exposure Regimen: 16 hours per day for 14 days for Ocimum basilicum [28]

- Outcome Assessment: Measure PAL enzyme activity and total phenolic concentration [25]

Monochromatic LED Treatments

Blue Light Treatment for Flavonoid Enhancement:

- Light Source: Blue lamps or LEDs (400-495 nm) [28]

- Photoperiod: 10-14 hours per day for 9-14 days [28]

- Application: Particularly effective in Oryza sativa for enhancing flavonoid biosynthesis genes [28]

Red Light Treatment for Terpenoids and Alkaloids:

- Light Source: Red LED (620-660 nm) [28]

- Photoperiod: 16-18 hours per day for 35-42 days [28]

- Species-Specific Applications: Effective for enhancing tropane alkaloids in Atropa belladonna and proanthocyanidins in Scots Pine [28]

Mixed LED Lighting Systems

Combined Red/Blue Treatments:

- Ratio: 70% red (650 nm) / 30% blue (460 nm) for Melissa officinalis [28]

- Photoperiod: 16 hours per day for 49 days [28]

- Outcome: Upregulation of DAHPS, TAT, RAS genes, increasing total phenolics and rosmarinic acid [28]

Analytical Methods for Metabolite Profiling

Comprehensive analysis of light-induced secondary metabolites requires advanced analytical techniques:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): For targeted and non-targeted analysis of phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and terpenoids [29]

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Particularly suitable for volatile terpenoids and certain phenolic compounds [29]

- High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Provides accurate mass measurements for structural elucidation of novel metabolites [29]

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: For definitive structural characterization of isolated compounds [29]

Quantitative Effects of Light on Secondary Metabolites

The effects of light quality on secondary metabolite accumulation have been quantitatively documented across numerous plant species. The following table summarizes key experimental findings:

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Light Quality on Plant Secondary Metabolites

| Plant Species | Light Treatment | Key Metabolites Enhanced | Magnitude of Increase | Key Regulated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangifera indica | UV-B/White LED (312 nm), 14 days | Anthocyanins, flavonoids, phenolics | Significant increase | MYB, C2H2, HSF, bHLH [28] |

| Stevia rebaudiana | UV-B exposure | Total flavonoid, phenolic content | Marked enhancement | Not specified [25] |

| Oryza sativa | Blue lamp, 14 days | Flavonoids, JA | Significant accumulation | PAL, 4CL, CCR, CHS, CHI [28] |

| Atropa belladonna | Red LED (620-660 nm), 35 days | Hyoscyamine, scopolamine | Notable enhancement | GDHA, At2g42690, PAO5 [28] |

| Scots Pine | Red/Far-red LED (660/720 nm), 40 days | Proanthocyanidins, catechins | Significant increase | CHS, JAZa [28] |

| Taxus wallichiana | UV-B (280-320 nm), 48 h | Paclitaxel, cephalomannine | Enhanced production | Bapt, Dbtnbt [25] [28] |

| Melissa officinalis | 70%R/30%B LED, 49 days | Total phenolics, rosmarinic acid | Marked accumulation | DAHPS, TAT, RAS [28] |

| Brassica napus | Supplemental UV-B, 3 days | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, anthocyanin | Significant increase | PAL, C4H, 4CL, CHS, CHI [28] |

Integration with Metabolic Engineering Approaches

The understanding of light-mediated regulation of secondary metabolism provides critical tools for metabolic engineering approaches aimed at enhancing valuable compounds. Several strategies have emerged:

CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Metabolic Engineering

The CRISPR/Cas system has been widely applied in genome editing with high accuracy, efficiency, and multiplex targeting ability for enhancing secondary metabolite production [30]. Key applications include:

- Carotenoid Enhancement: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of OsOr gene increased β-carotene accumulation in rice endosperm [30]

- Lycopene Enhancement: Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 editing of SGR1, LCY-E, Blc, LCY-B1, and LCY-B2 genes increased lycopene content by 5.1-fold in tomato fruit [30]

- Alkaloid Modulation: Precise knockout of alkaloid biosynthetic genes to redirect metabolic flux toward desired compounds [30]

Combined Light and Genetic Engineering Strategies

Integrated approaches combining light treatment with genetic engineering show promise for synergistic enhancement of secondary metabolites:

- Light-Controlled Gene Expression: Using light-responsive promoters to temporally control transgene expression in metabolic pathways

- Photoreceptor Engineering: Modifying photoreceptor genes to enhance plant sensitivity to specific light wavelengths

- Transcription Factor Optimization: Engineering HY5, MYB, or bHLH transcription factors for enhanced responsiveness to light signals

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table provides essential research reagents and materials for investigating light-regulated secondary metabolism:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Light-Mediated Secondary Metabolism Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic LED Systems | Provide specific light wavelengths for quality experiments | Red LED (620-660 nm), Blue LED (450-495 nm), UV-A LED (365-399 nm) [28] [26] |

| UV-B Light Sources | UV-B treatment for eliciting defense responses | UV-B fluorescent lamps (280-320 nm), supplemental UV-B tubes (311 nm) [25] [28] |

| Light Measurement Equipment | Quantify light intensity and spectral quality | Spectroradiometers, quantum sensors, photometers |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Genome editing for metabolic engineering | Cas9 nucleases, guide RNAs, transformation vectors [30] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Analyze gene expression of biosynthetic genes | Primers for HY5, MYB, PAL, CHS, DFR, etc. [25] [28] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Metabolite profiling and quantification | High-resolution systems for targeted/untargeted analysis [29] |

| ELISA Kits | Phytohormone analysis in light signaling | JA, SA, ABA quantification kits [25] |

| Protein Extraction Kits | Study photoreceptor protein interactions | Native extraction buffers, co-immunoprecipitation reagents [27] |

Light regulation of plant secondary metabolism represents a sophisticated adaptive mechanism that integrates environmental sensing with chemical defense strategies. The multidimensional regulatory mechanisms—spanning light quality, intensity, and photoperiod—offer researchers and drug development professionals precise tools for directing the biosynthesis of valuable medicinal compounds. The continued integration of photobiological knowledge with emerging metabolic engineering technologies, particularly CRISPR/Cas systems, promises to enhance our ability to produce plant-derived pharmaceuticals and functional nutrients in a controlled and sustainable manner. Future research directions should focus on elucidating species-specific light responses, developing more precise light delivery systems, and integrating multi-omics approaches to fully unravel the complex networks connecting light perception to secondary metabolic output.

Historical Impact of Natural Products in Drug Discovery and Development

Natural products (NPs) and their secondary metabolites have served as a cornerstone in the development of therapeutics for millennia, with their historical application in traditional medicines forming the basis of modern pharmacotherapy. This whitepaper delineates the historical trajectory of NP-derived drug discovery, from ancient empirical uses to contemporary, precision-driven engineering of secondary metabolites in plants and microbes. It underscores the critical role of NPs in treating cancers, infectious diseases, and other complex conditions, and details the advanced methodologies—including metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and AI-driven discovery—that are revitalizing NP research today. Framed within the context of engineering secondary metabolite pathways, this review provides a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, offering structured data, experimental protocols, and pathway visualizations to support ongoing innovation in this field.

The historical significance of natural products in drug discovery is irrefutable. Natural products (secondary metabolites) are low molecular weight compounds produced by plants, microbes, and marine organisms that are not essential for primary growth and development but play crucial roles in the organism's adaptation and defense [31] [32]. These compounds have been the most successful source of potential drug leads historically, providing unique structural diversity unmatched by standard combinatorial chemistry [31] [33]. Despite a decline in interest from the pharmaceutical industry in the late 20th century due to technical barriers, recent technological and scientific developments are revitalizing NP-based drug discovery, particularly for tackling antimicrobial resistance and complex diseases like cancer [33] [34].

The structural complexity and bioactivity profiles of NPs stem from their evolutionary optimization for specific biological interactions. Secondary metabolites are hypothesized to be produced through modifications in biosynthetic pathways, potentially due to natural causes like viruses or environmental changes, as organisms adapt for longevity [31]. This evolutionary refinement makes them privileged structures for interacting with biological targets, with an estimated 25% of modern pharmaceuticals in western countries being derived from plants alone [35]. The global market for plant-derived secondary metabolites is valued at approximately US$30 billion annually, highlighting their immense economic and therapeutic significance [36].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Natural Product Discovery and Development

| Era/Period | Key Developments | Representative Natural Products |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient (2600 BC - 1000 AD) | Early documentation in Mesopotamian cuneiform, Egyptian Ebers Papyrus, Chinese Materia Medica [31] | Oils from Cupressus sempervirens (Cypress), Commiphora species (myrrh) [31] |

| 18th-19th Century | Isolation of pure bioactive compounds from medicinal plants [31] [32] | Morphine from Papaver somniferum (opium poppy), salicin from Salix alba (willow bark) [31] |

| Early-Mid 20th Century | Development of semi-synthetic derivatives; birth of chemical ecology and chemotaxonomy [31] [32] | Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin), heroin (from morphine) [31] |

| Late 20th Century | Decline in NP pursuit by big pharma; rise of plant cell and tissue culture for NP production [33] [35] | Taxol (paclitaxel) from Taxus species [35] |

| 21st Century - Present | Re-emergence fueled by omics, metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and AI [33] [37] [34] | Artemisinin, NP-derived Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) [34] |

Historical Foundations and Key Discoveries

Ancient and Traditional Medicine Origins

The earliest records of natural product medicine are depicted on clay tablets in cuneiform from Mesopotamia (2600 B.C.), which documented oils from Cupressus sempervirens (Cypress) and Commiphora species (myrrh) that are still used today to treat coughs, colds, and inflammation [31]. Subsequent ancient documents, including the Ebers Papyrus (2900 B.C.), an Egyptian pharmaceutical record documenting over 700 plant-based drugs, and the Chinese Materia Medica (1100 B.C.), established foundational knowledge that was preserved and expanded through Greek, Arab, and European traditions [31]. The dominant source of knowledge of natural product uses from medicinal plants resulted from humans experimenting by trial and error for hundreds of centuries through palatability trials, searching for available foods and treatments for diseases [31].

Landmark Natural Product-Derived Pharmaceuticals

Probably the most famous example of a natural product-derived drug is the anti-inflammatory agent acetylsalicyclic acid (aspirin), derived from the natural product salicin isolated from the bark of the willow tree Salix alba L. [31]. Investigation of Papaver somniferum L. (opium poppy) resulted in the isolation of several alkaloids including morphine, a commercially important painkiller first reported in 1803 [31]. In the 1870s, crude morphine was boiled in acetic anhydride to yield diacetylmorphine (heroin), and was found to be readily converted to codeine, another vital painkiller [31]. These early discoveries established a template for the isolation, structural elucidation, and synthetic modification of natural products that continues to drive drug discovery.

Table 2: Historically Significant Natural Products and Their Derivative Drugs

| Natural Product Source | Bioactive Compound | Derivative Drug/Therapeutic Use | Discovery Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salix alba L. (Willow Bark) | Salicin | Acetylsalicylic Acid (Aspirin) / Anti-inflammatory, analgesic [31] | ~400 BC (Willow use); 1897 (Synthesis) |

| Papaver somniferum L. (Opium Poppy) | Morphine, Codeine | Pain Management / Strong analgesic [31] | 1803 (Isolation) |

| Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar Periwinkle) | Vinblastine, Vincristine | Cancer Chemotherapy / Anticancer [32] | 1950s |

| Taxus brevifolia (Pacific Yew) | Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Cancer Chemotherapy / Ovarian, breast cancer [35] | 1971 (Isolation) |

| Artemisia annua (Sweet Wormwood) | Artemisinin | Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies / Antimalarial [34] | 1972 (Isolation) |

| Digitalis purpurea (Foxglove) | Digitoxin | Digoxin / Heart failure, arrhythmia [32] | 1785 (First described) |

The Shift to Engineering and Production of Secondary Metabolites

From Wild Harvest to In Vitro Production