Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Tolerance to Industrial Stress

This article synthesizes the latest strategies in synthetic and systems biology for enhancing microbial tolerance to harsh industrial conditions, a critical bottleneck in biomanufacturing.

Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Tolerance to Industrial Stress

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest strategies in synthetic and systems biology for enhancing microbial tolerance to harsh industrial conditions, a critical bottleneck in biomanufacturing. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational tolerance mechanisms to advanced engineering methodologies. We explore the molecular basis of microbial stress responses to toxins, acids, and solvents; detail cutting-edge tools like adaptive laboratory evolution, tolerance engineering, and genome-scale perturbation; address troubleshooting for common optimization challenges; and evaluate validation frameworks for assessing performance. The goal is to serve as a strategic guide for constructing robust microbial cell factories that improve yield and efficiency in producing pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and chemicals.

Decoding Microbial Defense: Core Mechanisms of Stress Tolerance and Industrial Robustness

Core Concepts FAQ

What is the fundamental role of the cell envelope in microbial tolerance? The cell envelope is a complex, multilayered structure that serves as the primary protective barrier, separating the cytoplasm from its often hostile and unpredictable environment [1]. It is not merely a passive bag but a sophisticated interface that protects the cell while allowing selective passage of nutrients and waste products [1]. Beyond its barrier function, it is critical for maintaining cellular shape, stability, and rigidity, and is directly involved in communication with the environment [2]. In industrial contexts, where microbes are exposed to toxic chemicals (e.g., solvents, biofuels) and other stresses, the integrity of the cell envelope is paramount for survival and productivity [3].

How do the basic architectures of Gram-negative and Gram-positive cell envelopes differ, and why does this matter for engineering? The fundamental architectural differences dictate which engineering strategies are most feasible and effective for enhancing tolerance [3].

- Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli) possess a dual-membrane structure. The inner membrane (IM) is a phospholipid bilayer, while the outer membrane (OM) has an inner leaflet of phospholipids and an outer leaflet composed primarily of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [1]. A thin layer of peptidoglycan is situated in the periplasmic space between the two membranes. The LPS layer provides a formidable barrier against hydrophobic toxins and antibiotics [1].

- Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) lack an outer membrane. Instead, they have a single cytoplasmic membrane that is often enriched with long-chain fatty acids and lipoteichoic acids [3]. This membrane is surrounded by a much thicker peptidoglycan cell wall, which is threaded with anionic polymers like teichoic acids [1]. The absence of an OM makes them inherently more susceptible to hydrophobic toxins [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Cell Envelope Architectures and Engineering Strategies

| Microorganism Type | Key Envelope Components | Suitable Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative Bacteria | Inner membrane, periplasm, outer membrane with LPS, thin peptidoglycan layer [3] | Modifying phospholipid composition, engineering membrane proteins, reinforcing LPS layer [3] |

| Gram-positive Bacteria | Single membrane, thick peptidoglycan wall, contains teichoic acids [1] [3] | Membrane protein engineering, strengthening the peptidoglycan wall, altering teichoic acids [3] |

| Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Eukaryotic plasma membrane (rich in ergosterol), cell wall with β-glucan, mannoproteins, and chitin [3] | Controlling sterol content and type, engineering efflux pumps, remodeling cell wall components [3] |

What are the major mechanisms by which the cell envelope maintains its integrity under stress? Cells employ multiple, often cooperative, mechanisms to repair a damaged plasma membrane [4]:

- Exocytosis-mediated repair: Intracellular membranes (e.g., from lysosomes or reserve granules) fuse with the plasma membrane at or near the injury site. This either patches the wound directly or reduces membrane tension to allow the edges to reseal [4].

- Endocytosis-mediated repair: The damaged section of the membrane, often containing pores, is removed via clathrin- or caveolin-mediated endocytosis and targeted for degradation [4].

- ESCRT-mediated shedding: The Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery facilitates the shedding of damaged membrane regions as microparticles or ectosomes [4].

- Protein-driven repair: Calcium-sensitive proteins like Annexins and MG53 rapidly aggregate at the wound site. They can form 2D arrays that restrict wound expansion, promote membrane bending, and reduce lipid tension to facilitate resealing [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Genetically engineered production host shows poor viability and cell lysis upon accumulation of the target product (e.g., biofuels, organic acids).

Potential Cause 1: The product is disrupting membrane integrity by fluidizing the lipid bilayer or dissolving into it.

- Solution: Engineer membrane lipid composition to enhance stability.

- Protocol - Modifying Fatty Acid Saturation in E. coli:

- Clone and express a desaturase gene (e.g., Bacillus Δ5-desaturase) under an inducible promoter.

- Grow the engineered strain in the presence of the toxic product (e.g., octanoic acid) and induce desaturase expression.

- Analyze membrane fluidity using fluorescence anisotropy with dyes like DPH.

- Measure the degree of fatty acid unsaturation via Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) of lipid extracts.

- Expected Outcome: Increased levels of unsaturated fatty acids (e.g., from 15% to 30% of total lipids) can maintain membrane fluidity under stress, leading to a 41% increase in titers for products like octanoic acid [3].

- Protocol - Modifying Fatty Acid Saturation in E. coli:

- Solution: Enhance the sterol content in yeast membranes.

- Protocol - Upregulating Ergosterol Biosynthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica:

- Overexpress key ergosterol biosynthesis genes (e.g., ERG1, ERG11) using strong, constitutive promoters.

- Cultivate the strain under organic solvent stress.

- Quantify ergosterol content using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Assess membrane integrity with propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry.

- Expected Outcome: A 2.2-fold increase in ergosterol content can significantly improve resistance to organic solvents [3].

- Protocol - Upregulating Ergosterol Biosynthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica:

- Solution: Engineer membrane lipid composition to enhance stability.

Potential Cause 2: The toxic product is accumulating to high levels inside the cell because it is not being effluxed.

- Solution: Overexpress endogenous or heterologous transporter proteins.

- Protocol - Engineering Efflux in S. cerevisiae for Fatty Alcohol Production:

- Identify and clone a heterologous transporter protein (e.g., an ATP-binding cassette transporter).

- Integrate the gene into the yeast genome under a stress-inducible promoter.

- Ferment the engineered strain and measure extracellular and intracellular product concentrations using GC-MS.

- Monitor real-time export using a fluorescently tagged product analog, if available.

- Expected Outcome: Overexpression of specific transporters can lead to a 5-fold increase in the secretion of toxic products like fatty alcohols, drastically reducing intracellular accumulation [3].

- Protocol - Engineering Efflux in S. cerevisiae for Fatty Alcohol Production:

- Solution: Overexpress endogenous or heterologous transporter proteins.

Problem: Engineered strain performs well in lab-scale cultures but fails in large-scale bioreactors with complex feedstocks (e.g., containing lignin-derived inhibitors).

- Potential Cause: The cell wall is compromised by chemical inhibitors or physical shear stress in the bioreactor, leading to integrity loss.

- Solution: Engineer the cell wall to enhance its robustness.

- Protocol - Strengthening the Peptidoglycan Layer in E. coli:

- Overexpress genes involved in peptidoglycan precursor synthesis (e.g., murA, murB).

- Modulate the expression of peptidoglycan hydrolases and synthases to promote a thicker, more cross-linked wall.

- Challenge the engineered strain with known cell wall-targeting antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin) to test for increased Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC).

- Quantify cell wall thickness using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

- Expected Outcome: A reinforced cell wall can lead to a 93% increase in the accumulation of toxic bioproducts like polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and significantly improve tolerance to lignin-derived inhibitors [3].

- Protocol - Strengthening the Peptidoglycan Layer in E. coli:

- Solution: Engineer the cell wall to enhance its robustness.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Methods

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Cell Envelope Engineering

| Reagent / Method | Function / Application | Key Details & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane integrity staining [5]. | A charged dye that is excluded by intact membranes. Cells with compromised membranes fluoresce red. Ideal for flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. |

| SYTOX Stains | Membrane integrity staining [5]. | Similar to PI but with different spectral properties (e.g., SYTOX Green). Useful for multiplexing assays. |

| Laurdan | Membrane fluidity and phase analysis [2]. | A fluorescent dye whose emission spectrum shifts based on the polarity of its environment, reporting on lipid packing and phase separation (liquid-ordered vs. liquid-disordered). |

| GC-MS | Analysis of membrane lipid composition [3]. | Used to quantitatively profile fatty acid chains (saturation, chain length) from extracted membrane lipids. Critical for verifying engineering outcomes. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Nanoscale topological and mechanical analysis of membranes [6] [2]. | Provides exceptional resolution of membrane roughness, thickness, and the presence of lipid domains. Can be performed on live cells. |

| Force Spectroscopy (FS) | Measuring membrane elasticity and nanomechanical properties [6]. | An AFM mode that measures Young's modulus, providing a direct readout of membrane stiffness and resilience in response to engineering. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Genome editing for metabolic engineering [7]. | Enables precise knockout or knock-in of genes involved in lipid biosynthesis, efflux pumps, and cell wall assembly. |

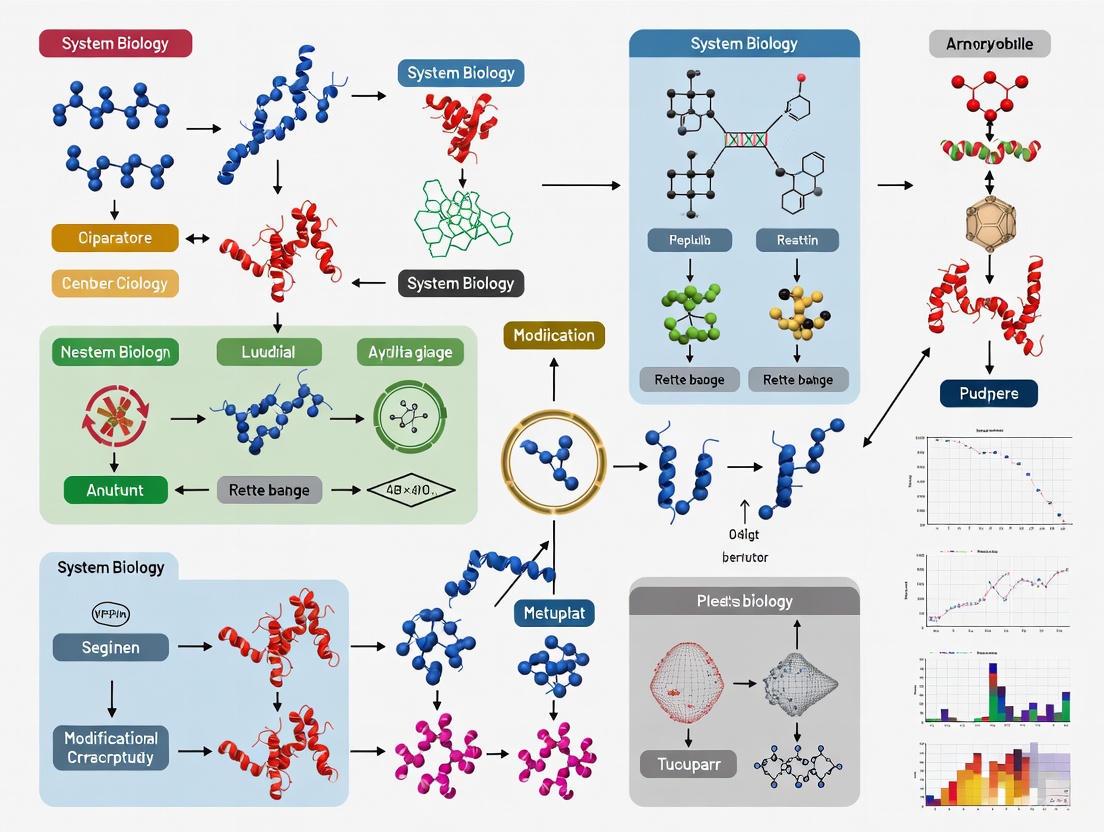

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Visualization

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for a research project aimed at enhancing microbial tolerance through cell envelope engineering.

Diagram 1: Cell Envelope Engineering Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the coordinated role of membrane lipids and the cell wall in maintaining overall envelope integrity, a key concept for troubleshooting.

Diagram 2: Envelope Integrity Maintenance Mechanisms

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues in Microbial pH Homeostasis Research

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Causes | Proposed Solutions & Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid cell death in acidic bioreactor | Compromised cell membrane integrity leading to excessive proton influx [8]; Insufficient activity of proton efflux pumps (e.g., H+-ATPase) [8]. | 1. Analyze membrane lipid composition: Check for changes in tetraether lipids or bulky isoprenoid cores [8] [9].2. Measure H+-ATPase activity: Assay activity and increase ATP supply via auxiliary energy cosubstrates like citrate [8].3. Genetic analysis: Screen for mutations in genes encoding key membrane porins (e.g., Omp40) [9]. |

| Inability to maintain ΔpH under organic acid stress | Organic acids (e.g., acetic, lactic) acting as uncouplers, diffusing into the cell in protonated form and dissociating [9]. | 1. Pre-adapt culture: Gradually expose microbes to sub-inhibitory levels of the organic acid [8].2. Enhance degradation pathways: Engineer or select for strains with enhanced organic acid degradation enzymes [9].3. Modify membrane permeability: Use adaptive evolution to select for strains with less permeable membranes [8]. |

| Low cytoplasmic pH despite functional proton pumps | Inadequate energy (ATP) supply to power proton efflux systems [8]; Excessive inward proton leak due to membrane defects. | 1. Boost ATP generation: Add auxiliary energy substrates (e.g., citrate) to enhance oxidative phosphorylation [8].2. Measure membrane potential (ΔΨ): Use fluorescent dyes (e.g., DiS-C3-5) to determine if a reversed, inside-positive ΔΨ is established to restrict H+ influx [9] [10].3. Check potassium transporters: Ensure K+ uptake systems are active to generate a chemiosmotic gradient [8]. |

| Unstable protein/DNA function in isolated acidophile enzymes | In vitro assay pH is too low, failing to replicate the near-neutral cytoplasmic conditions [9]. | 1. Adjust assay pH: Perform functional assays at a pH close to the maintained cytoplasmic pH (e.g., ~6.5) rather than the extreme external pH [9].2. Add stabilizing factors: Include cytoplasmic buffering molecules (e.g., histidine, arginine) or chaperones in the assay buffer [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms microbes use to prevent proton influx across the cell membrane? Microbes, especially acidophiles, employ a multi-layered strategy to restrict proton influx, which is critical for maintaining a large pH gradient (ΔpH) [9]:

- Membrane Impermeability: They possess highly impermeable cell membranes, often reinforced by unique lipid compositions like tetraether lipids in some archaea, which form a robust monolayer barrier [8] [9].

- Porin Regulation: Acidophiles like Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans modulate outer membrane porins (e.g., Omp40). A large external loop can control pore size and ion selectivity, limiting proton access to the periplasm [8] [9].

- Generation of a Donnan Potential: Many acidophiles generate an inside-positive membrane potential (Δψ) through the accumulation of positive charges, often via potassium ion transporters. This positive internal charge creates a chemiosmotic barrier that electrostatically repels incoming protons [8] [9] [10].

Q2: How do proton pumps like H+-ATPase contribute to pH homeostasis, and how can I enhance their activity in a production strain? Proton pumps, such as the H+-ATPase, are active systems that purge excess protons from the cytoplasm at the cost of ATP hydrolysis [8] [10]. Enhancing their activity is a key strategy in tolerance engineering:

- Function: They directly counteract the inward leak of protons, helping to maintain a circumneutral cytoplasmic pH [8].

- Enhancement Strategies:

- Increase ATP Supply: The activity of H+-ATPase is energy-dependent. Adding auxiliary energy cosubstrates like citrate to the medium can enhance ATP regeneration through oxidative phosphorylation, thereby fueling the proton pumps [8].

- Genetic Overexpression: Overexpressing the genes encoding the H+-ATPase complex can increase the number of functional pumps in the membrane.

- Promoter Engineering: Using strong, constitutive, or stress-induced promoters can ensure high-level expression of pump components under industrial stress conditions [11].

Q3: My experiment requires measuring the cytoplasmic pH and membrane potential. What are the established methods? Accurately measuring these parameters is essential for quantifying pH homeostasis. The table below summarizes key methodological approaches [10]:

| Parameter | Method | Principle & Key Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasmic pH & ΔpH | Fluorescent Probes (e.g., BCECF, Oregon Green) | The fluorescence spectrum of the cell-entrapped dye shifts with pH. A standard curve is generated after PMF collapse and pH equilibration [10]. |

| Weak Acid/Base Distribution (e.g., DMO, benzoic acid) | The passive distribution of a radioactive or fluorescent weak acid across the membrane is used to calculate the ΔpH (alkaline inside) and thus the cytoplasmic pH [10]. | |

| pH-Sensitive GFP | Genetically encoded GFP mutants whose fluorescence is pH-dependent allow direct, non-invasive monitoring of cytoplasmic or periplasmic pH [10]. | |

| Membrane Potential (ΔΨ) | Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., DiS-C3-5, oxonols) | Cationic or anionic dyes accumulate in the cell in a manner dependent on the Δψ (typically negative inside), causing fluorescence quenching or shifts [10]. |

| Radiolabeled Probes (e.g., triphenylphosphonium, SCN⁻) | The distribution of lipophilic ions between cells and the medium is measured to determine the magnitude of the Δψ [10]. |

Q4: Why is potassium ion transport frequently mentioned in the context of acidophile pH homeostasis? Potassium transporters are considered one of the most efficient systems for generating a protective chemiosmotic gradient [8]. The active uptake of K+ ions leads to a net accumulation of positive charges inside the cell, creating a "reversed" inside-positive membrane potential (Δψ) [9] [10]. This positive potential directly inhibits the inward movement of positively charged protons, serving as a critical primary barrier against the immense proton gradient faced by acidophiles [8].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing H+-ATPase Proton Pump Activity

Principle: This protocol measures the inorganic phosphate (Pi) released from ATP hydrolysis by H+-ATPase in membrane preparations to quantify pump activity [8].

Workflow Diagram:

Steps:

- Cell Harvest & Membrane Preparation: Grow microbial culture to mid-log phase. Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash, and resuspend in appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). Disrupt cells using sonication or French press. Remove unbroken cells and debris by low-speed centrifugation. Pellet the membrane fraction via ultracentrifugation (e.g., 100,000 × g for 1 hour) and resuspend in storage buffer.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reaction mixtures containing assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5), an ATP-regenerating system, and the membrane protein sample. Pre-incubate at the desired assay temperature (e.g., 30°C).

- Initiate Reaction & Quench: Start the reaction by adding ATP (final conc. 5 mM). Aliquot the reaction mixture at specific time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 10, 15 minutes) into a stopping solution (e.g., SDS or acid).

- Phosphate Detection: Use a colorimetric method (e.g., malachite green assay) to measure the amount of inorganic phosphate (Pi) released in each quenched sample.

- Calculation: Plot Pi generated versus time. The slope of the initial linear phase represents the ATPase activity. Normalize this value to the total membrane protein concentration to obtain specific activity (μmol Pi/min/mg protein).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Membrane Permeability to Protons

Principle: This method monitors the collapse of a pre-established pH gradient in cells or membrane vesicles to assess passive proton leak rates [9].

Workflow Diagram:

Steps:

- Dye Loading: Harvest and wash cells. Load with a pH-sensitive fluorescent dye like BCECF-AM by incubating with the dye ester in a weak buffer.

- Establish pH Gradient: Resuspend the dye-loaded cells in a weakly buffered acidic medium (e.g., pH 4.0 for a neutralophile). The cells will actively maintain a higher internal pH, creating a ΔpH.

- Initiate Proton Leak: Rapidly add a pulse of a strong acid to the suspension or inhibit active proton pumps with a specific inhibitor (e.g., N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide for F-type ATPases). Do not add protonophores at this stage.

- Monitor Fluorescence: Continuously monitor the fluorescence of the dye (e.g., excitation 490/440 nm, emission 535 nm for BCECF). The rate of fluorescence decrease reflects the rate of cytoplasmic acidification due to passive proton influx.

- Calibrate and Calculate: At the end of the experiment, calibrate the fluorescence signal to pH using high-K+ buffers and the ionophore nigericin. The initial rate of pH decline after pump inhibition is a direct measure of the membrane's passive proton permeability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in pH Homeostasis Studies |

|---|---|

| Proton Ionophores (e.g., CCCP, FCCP) | Uncouplers that dissipate the proton gradient (ΔpH) across the membrane. Used to collapse the PMF and study its necessity in various processes or to measure maximum proton leak rates [9]. |

| H+-ATPase Inhibitors (e.g., DCCD, Esomeprazole) | Specifically target and inhibit the proton-pumping activity of H+-ATPase. DCCD is a classical biochemical tool, while Esomeprazole is a PPI that can be used to study related ATPases [8] [12]. |

| K+ Ionophores (e.g., Valinomycin, Nigericin) | Valinomycin carries K+ ions, allowing the manipulation of the membrane potential (ΔΨ). Nigericin exchanges K+ for H+, collapsing both ΔpH and ΔΨ. Essential for dissecting the components of the PMF [10]. |

| pH-Sensitive Fluorophores (e.g., BCECF-AM, Oregon Green) | Cell-permeant dyes used to measure real-time changes in cytoplasmic pH. The AM ester is cleaved by intracellular esterases, trapping the dye inside the cell [10]. |

| ATP-Regenerating System (e.g., Phosphocreatine & Creatine Kinase) | Maintains a constant ATP level in in vitro assays of ATP-dependent processes like H+-ATPase activity, preventing substrate depletion and ensuring linear reaction kinetics [8]. |

Conceptual FAQs: Understanding the Core Mechanisms

FAQ 1: What are the key transcription factors that orchestrate the global transcriptional reprogramming in response to proteotoxic stress? The Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) is the master regulator of the heat shock response (HSR), an evolutionarily conserved survival program activated by proteotoxic stress [13] [14]. In response to stress, HSF1 undergoes trimerization, translocates to the nucleus, and binds to Heat Shock Elements (HSEs) in the promoters of target genes [13]. This process is tightly regulated by post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, sumoylation, and acetylation [13]. Activation of HSF1 leads to the rapid and massive upregulation of genes encoding molecular chaperones, known as Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs), which function to protect and repair cellular components [15] [13]. In the yeast osmostress response, the Hog1 SAPK acts as a key signaling molecule and direct transcriptional regulator, recruiting chromatin-modifying enzymes and RNA Polymerase II to target genes [16].

FAQ 2: How do cells globally repress transcription upon stress, and what is its functional significance? During acute stress, cells initiate a massive transcriptional reprogramming that involves not only the activation of stress-responsive genes but also the active and global attenuation of non-essential transcription [15] [14]. Genome-wide studies using Precision Run-On sequencing (PRO-seq) have shown that in heat-stressed mammalian cells, RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) accumulates at the promoter-proximal pause region of repressed genes, effectively halting their transcription [15]. This global repression targets gene categories related to ribosome biogenesis, translation machinery, and cell growth, thereby conserving energy and cellular resources to prioritize the execution of survival programs [15] [16]. This repressive state is an active process, facilitated by a general breakdown of transcription machinery and decreased mRNA stability [16].

FAQ 3: Why is transcriptional heterogeneity important in microbial populations under stress? Single-cell RNA-sequencing studies in yeast have revealed that isogenic cell populations display highly heterogeneous expression of stress-responsive programs, organizing into distinct combinatorial patterns [16]. This heterogeneity is not random; it generates functionally distinct cellular subpopulations with different adaptive potentials. For example, some cells may strongly induce chaperones, while others prioritize metabolic shifts [16]. This "bet-hedging" strategy ensures that a subset of pre-adapted cells survives a sudden environmental insult, thereby increasing the overall fitness of the population. This heterogeneity is influenced by factors such as differential transcription factor activity and chromatin remodeling [16].

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Experimental Challenges

Problem: High Cell-to-Cell Variability in Reporter Gene Expression

- Problem Description: When using a reporter gene (e.g., GFP under a stress-inducible promoter), microscopy or flow cytometry reveals a wide distribution of expression levels across an isogenic population, rather than a uniform response.

- Possible Cause: This is often a biological phenomenon, not an experimental artifact. Stress responses are inherently heterogeneous due to variations in transcription factor nuclear localization, chromatin state, and pre-existing cellular conditions [16] [13].

- Solution:

- Confirm the Finding: Perform single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH) to validate transcript heterogeneity at the single-cell level [16].

- Investigate the Cause: Consider tracking the dynamics of key transcription factors (e.g., Msn2/4 in yeast) using live-cell imaging to see if their oscillatory behavior correlates with output heterogeneity [16].

- Embrace the Heterogeneity: Instead of treating it as noise, analyze the data to identify distinct functional subpopulations. Tools like unsupervised clustering (e.g., PCA) on single-cell data can reveal these subpopulations [16].

Problem: Inefficient Activation of the Heat Shock Response

- Problem Description: Expected strong upregulation of HSP genes is not observed upon heat stress, as measured by qPCR or RNA-seq.

- Possible Causes:

- Attenuated HSF1 Activity: In aged microbial cultures or after prolonged stress, the HSF1 signaling pathway can become attenuated. This may be due to decreased expression of regulators like SIRT1 or increased levels of HSP70 that sequester HSF1 in an inactive complex [13].

- Insufficient Stress Signal: The stress threshold for activation may not have been reached.

- Solution:

- Titrate Stressor: Perform a dose-response experiment to find the optimal activation threshold (e.g., 37°C to 42°C for heat shock).

- Assess HSF1 Status: Use western blotting to check for HSF1 post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) and its localization via immunofluorescence [13].

- Modulate the Pathway: Pharmacologically activate SIRT1 with compounds like resveratrol, which has been shown to prolong HSF1 binding to target promoters and enhance the heat shock response [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Mapping of Transcriptionally-Engaged RNA Polymerase II

Objective: To capture the precise location of transcribing RNA Pol II complexes at nucleotide resolution during stress response [15].

Method: Precision Run-On sequencing (PRO-seq)

- Cell Harvesting: Harvest cultured cells (e.g., mouse fibroblasts, yeast) at baseline and at multiple time points after stress application (e.g., 2.5, 5, 10, 15 minutes post-heat shock).

- Nuclear Run-On: Permeabilize cells and isolate nuclei. Incubate nuclei in a run-on reaction mixture containing biotin-labeled ribonucleotides (e.g., Biotin-11-NTP).

- RNA Extraction & Purification: Extract and fragment the newly synthesized, biotin-labeled nascent RNA. Purify the RNA using streptavidin beads.

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare a high-throughput sequencing library from the purified RNA. Sequence the libraries to map the 3' ends of nascent transcripts, revealing the exact position of Pol II [15].

Key Data Interpretation: PRO-seq data allows for the quantification of Pol II density at promoter-proximal pause sites, along gene bodies, and at enhancers. Repressed genes will show a loss of Pol II along coding sequences or accumulation at pause sites, while activated genes will show increased Pol II density throughout [15].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell RNA-seq for Profiling Transcriptional Heterogeneity

Objective: To longitudinally assess transcriptional dynamics and heterogeneity during stress adaptation in microbial populations [16].

- Cell Preparation: Culture wild-type and mutant strains (e.g.,

hog1Δin yeast) with unique genetic barcodes. Mix strains before processing to control for technical variability. - Stress Application & Sampling: Apply stress (e.g., 0.4 M NaCl for osmostress) and collect cells at multiple time points (e.g., 5, 15, 30 minutes).

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation: Use a droplet-based scRNA-seq platform (e.g., 10x Genomics) to partition single cells and barcode their transcripts. Sequence the libraries.

- Computational Analysis:

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality cells (e.g., those with <500 or >3000 genes detected).

- Clustering: Perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) on the expression data to identify distinct transcriptional subtypes.

- Heterogeneity Scoring: Calculate the percentage of cells expressing specific stress-responsive genes and the average expression level of transcriptional programs across the population [16].

Quantitative Data from Key Studies: The following table summarizes kinetic classes of gene expression observed during heat stress in mammalian cells, as defined by PRO-seq data [15]:

| Gene Class | Example Genes | Pol II Kinetics Upon Heat Stress | Proposed Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapidly Induced | HSP70, HSP40 | Pol II density increases within 2.5 minutes | Instant protection & repair of protein folding [15] |

| Transiently Induced | Cytoskeletal genes | Rapid induction followed by repression below baseline | Rapid, transient adjustment of cell structure [15] |

| Rapidly Repressed | Ribosomal proteins, translation factors | Pol II density decreases within 10 minutes | Energy conservation, shutdown of growth [15] |

| Delayed Repressed | RNA processing factors | Pol II density declines more slowly | Delayed metabolic adjustment [15] |

Pathway and Mechanism Visualizations

Diagram Title: HSF1 Activation and Feedback in Heat Shock Response

Diagram Title: Transcriptional Subpopulations from scRNA-seq

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Method | Function in Stress Research | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Run-On seq (PRO-seq) | Maps the exact position of transcriptionally-engaged RNA Polymerase II genome-wide at nucleotide resolution [15]. | Kinetic analysis of transcriptional repression/activation during heat shock; identifies promoter-proximal pausing [15]. |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) | Profiles transcriptomes of individual cells to quantify population heterogeneity and identify distinct transcriptional states [16]. | Revealed combinatorial patterns of osmoresponsive gene usage in yeast, defining hyper-adapted subpopulations [16]. |

| Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) | Master transcription factor that binds Heat Shock Elements (HSEs) to drive chaperone gene expression [13]. | Target for modulating proteostasis capacity; overexpression enhances aggregation resistance [13]. |

| Hog1 SAPK Mutants | Lacks the key kinase in the yeast High-osmolarity Glycerol pathway, abolishing the core transcriptional response to osmostress [16]. | Essential control strain to distinguish Hog1-dependent and independent stress signaling in scRNA-seq experiments [16]. |

| SIRT1 Activators (e.g., Resveratrol) | Activates SIRT1 deacetylase, which prolongs HSF1 binding to DNA and enhances the heat shock response [13]. | Used to counteract age-related or stress-induced attenuation of the heat shock response [13]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Microbial Cultivation with Toxic Products

When cultivating microbes for the production of high-value chemicals, researchers often encounter roadblocks related to product toxicity. The table below outlines common symptoms, their likely causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Product Toxicity Issues

| Observed Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sudden cessation of cell growth after initial logarithmic phase [17] | Accumulation of toxic end-products (e.g., alcohols, organic acids) to a critical inhibitory threshold. | • Implement in-situ product removal (ISPR) techniques.• Use fed-batch instead of batch fermentation to control substrate concentration.• Evolve or engineer strains for higher tolerance [3] [18]. |

| Decreased product yield or productivity over time [18] | Toxicity from intermediates or end-products reduces metabolic activity and cell viability. | • Modulate pathway expression to prevent intermediate accumulation.• Engineer efflux transporters to secrete the product from the cell [3].• Optimize media and culture conditions to reduce stress. |

| High cell mortality in production bioreactors compared to seed trains | Combined stress from toxic products and harsh industrial conditions (e.g., pH, osmolality) [11]. | • Employ adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) under simulated industrial conditions [18].• Engineer global stress response regulators [18]. |

| Inconsistent performance between lab-scale and large-scale fermentations | Scale-dependent differences in mixing and exposure to inhibitors or localized stress zones [18]. | • Use scale-down models to simulate large-scale heterogeneity in lab bioreactors.• Develop strains with robust tolerance independent of reactor geometry. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms by which end-products become toxic to the microbial cells that produce them?

Toxicity manifests through several mechanisms, often simultaneously [3] [17]:

- Membrane Disruption: Hydrophobic compounds like alcohols and aromatic molecules can integrate into and disrupt the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. This compromises membrane integrity, leading to leakage of vital cellular components and dissipation of proton motive force [3].

- Inhibition of Metabolic Enzymes: Products or intermediates can act as feedback inhibitors, binding to and inhibiting key enzymes in central metabolic pathways. This halts energy production and precursor synthesis [17].

- Protein Denaturation and Misfolding: Certain compounds, such as reactive aldehydes, can cause oxidative damage or directly interfere with protein folding, leading to loss of enzyme function and aggregation of misfolded proteins [3].

- Disruption of Energy Metabolism: Some toxins can uncouple electron transport from ATP synthesis or interfere with the function of ATPases, causing a catastrophic drop in cellular energy levels [18].

Q2: Beyond genetic engineering, what practical strategies can I use to mitigate product inhibition during fermentation?

Several process-level strategies can be implemented:

- In-situ Product Removal (ISPR): This involves continuously removing the inhibitory product from the fermentation broth as it is produced. Techniques include liquid-liquid extraction, pervaporation, adsorption, or stripping. This keeps the product concentration in the bioreactor below toxic levels [18].

- Fed-Batch Cultivation: By controlling the feed of the carbon source, you can prevent the simultaneous accumulation of high levels of substrate and product, thereby reducing metabolic burden and toxicity [17].

- Two-Phase Fermentation: Adding a water-immiscible organic solvent as a second phase can create a reservoir for extracting hydrophobic inhibitory products from the aqueous culture medium [18].

- Culture Condition Optimization: Fine-tuning parameters like pH and temperature can significantly influence the degree of product toxicity. For example, the undissociated form of organic acids is more toxic, so controlling pH can modulate their effect [17].

Q3: How can I quickly improve the tolerance of my microbial host without a fully sequenced genome or detailed mechanistic understanding?

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) is a powerful non-rational approach for this purpose [18].

- Protocol:

- Inoculate your microbial strain in a medium containing a sub-lethal concentration of the toxic product or hydrolysate.

- Serially passage the culture repeatedly (e.g., daily or as it reaches stationary phase) into fresh medium. Gradually and incrementally increase the concentration of the toxin over many generations.

- Monitor growth (OD600) to select populations that show improved growth rates or yields under stress.

- Once a desired phenotype is achieved, isolate single clones from the evolved population.

- Validation: Characterize the evolved clones for stable, improved tolerance and production performance in controlled fermentations. Whole-genome sequencing of the evolved isolates can later identify the causal mutations [18].

Q4: What are the key differences in engineering tolerance in Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, and yeast?

The different cell envelope structures dictate distinct engineering priorities, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Tolerance Engineering Strategies by Microbial Host [3]

| Microbial Host | Envelope Architecture | Suitable Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-Negative Bacteria (e.g., E. coli) | Inner membrane, thin peptidoglycan layer, and an outer membrane containing LPS [3]. | • Modify phospholipid composition in the inner membrane.• Engineer membrane proteins and efflux pumps.• Reinforce the outer membrane and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer. |

| Gram-Positive Bacteria (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) | A single membrane surrounded by a thick peptidoglycan cell wall [3]. | • Engineer the thick peptidoglycan wall for enhanced integrity.• Alter membrane protein composition.• Modify teichoic acids in the cell wall. |

| Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | A eukaryotic plasma membrane rich in ergosterol and a cell wall composed of β-glucan, mannoproteins, and chitin [3]. | • Control the content and type of sterols (e.g., ergosterol) to modulate membrane fluidity.• Engineer efflux pumps (e.g., Pdr family).• Remodel cell wall components like β-glucan and mannoproteins. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Microbial Tolerance

Protocol 1: Cell Membrane Engineering for Enhanced Solvent Tolerance

This rational engineering protocol aims to stabilize the cell membrane against the disruptive effects of hydrophobic compounds [3].

- Objective: To increase microbial tolerance to hydrophobic biofuels (e.g., fatty alcohols, alkanes) by modifying membrane lipid composition.

- Key Reagents:

- Plasmids for overexpression of genes like OLE1 (fatty acid desaturase in yeast) or cfa (cyclopropane-fatty-acyl-phospholipid synthase in bacteria) [18].

- Antibiotics for selective pressure.

- Toxic compound of interest (e.g., 1-decanol, octanoic acid).

- Methodology:

- Genetic Modification: Clone and express genes involved in fatty acid saturation (e.g., OLE1), chain length, or phospholipid headgroup composition in your host strain [3] [18].

- Tolerance Assay: Perform spot assays or growth curve analyses in liquid media with and without the toxic compound.

- Analysis: Compare the growth of the engineered strain to the wild-type control. Successful engineering is indicated by a higher growth rate or final cell density in the presence of the toxin [18].

- Workflow Visualization: The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of this membrane engineering process.

Protocol 2: Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME)

This semi-rational approach aims to reprogram the cellular transcriptome to elicit a broad tolerance phenotype [18].

- Objective: To generate mutant global transcription factors (e.g., Spt15 in yeast) that confer enhanced, multi-factorial tolerance to industrial conditions.

- Key Reagents:

- Mutagenesis library of a global transcription factor gene.

- Selective plates or liquid media containing a cocktail of inhibitors (e.g., alcohols, weak acids, furans).

- Methodology:

- Library Creation: Create a mutant library of a key transcription factor gene (e.g., using error-prone PCR).

- Selection: Transform the library into the host strain and plate on selective media containing inhibitory levels of the target stressor(s). Isolate colonies that show improved growth.

- Screening & Validation: Screen these isolates in microtiter plates or small-scale fermentations for both tolerance and production performance. Sequence the mutated gene in the best-performing strains [18].

- Workflow Visualization: The diagram below outlines the key steps in a gTME campaign.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Microbial Tolerance Engineering Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oleic Acid (C18:1) | A unsaturated fatty acid used to supplement media to directly modulate membrane fluidity. | Testing if increased membrane unsaturation confers tolerance to ethanol or butanol [3]. |

| Ergosterol | The primary sterol in yeast membranes; can be supplemented in anaerobic cultures where yeast cannot synthesize it. | Enhancing yeast tolerance to organic solvents by reinforcing membrane integrity [3]. |

| Plasmid for OLE1 Overexpression | Encodes a delta-9 fatty acid desaturase, which introduces double bonds into fatty acyl chains. | Engineering S. cerevisiae for increased membrane unsaturation and tolerance to octanoic acid [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | For precise genome editing to knock-in, knock-out, or modulate gene expression. | Introducing specific mutations into transcription factors or promoters of efflux transporters [7] [18]. |

| Inhibitor Cocktails | Custom mixtures of common hydrolysate inhibitors (e.g., furfural, HMF, acetic acid, phenolic compounds). | Mimicking the harsh environment of lignocellulosic hydrolysates during ALE or screening [18]. |

| Dodecane Overlay | A water-immiscible solvent used in two-phase fermentations. | In-situ removal of toxic, hydrophobic products like fatty alcohols or alkanes to alleviate toxicity [18]. |

Synthetic Biology Toolkit: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Tolerance and Production

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Microbial Survival in Industrial Bioreactors

Problem: Bacterial viability drops significantly during industrial-scale production due to combined stresses like desiccation, oxidation, and chemical toxicity.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid viability loss during spray drying | Membrane rupture from mechanical stress during dehydration [19] | Membrane integrity staining (e.g., propidium iodide) | Implement pre-conditioning with gradual desiccation or add external protectants like trehalose [19] |

| Low recovery post-rehydration | Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) causing cellular damage [19] | ROS detection assays (e.g., H2DCFDA staining), measure SOD/Catalase activity [19] | Engineer strains with enhanced antioxidant defenses (e.g., overexpress SOD/catalase genes); use anaerobic storage [20] [19] |

| Cell clumping & inconsistent performance | Inadequate protection from EPS or biofilms; genetic instability [21] | Biofilm formation assays (e.g., crystal violet), genomic DNA electrophoresis | Utilize surface engineering (e.g., LbL coatings) for more uniform protection; check for genetic mutations [19] |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting DNA Damage Repair and Tolerance Experiments

Problem: Unreliable or inconsistent results when assessing DNA damage tolerance pathways in engineered microbial strains.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Tests | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High mutation rates in product | Over-reliance on error-prone Translesion Synthesis (TLS) pathways [22] | piggyBlock assay or similar to quantify TLS vs. HDR pathway use [22] | Modulate expression of TLS polymerases (e.g., Rev1) to steer repair toward more accurate HDR [22] |

| Low overall survival after DNA damage | General deficiency in DNA Damage Tolerance (DDT) pathways [22] [20] | Clonogenic survival assays after UV or chemical damage | Overexpress key DDT genes (e.g., DRT100 from Sedum alfredii enhances Cd tolerance and genome stability) [20] |

| Failed complementation in mutant strains | Inefficient transfection/transformation of lesion-containing plasmids [22] | Check plasmid quality (gel electrophoresis), transformation efficiency | Optimize transfection protocol (e.g., use HyPB transposase for higher efficiency); verify plasmid construction with restriction digest [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary defense lines bacteria use against antimicrobial agents or industrial stresses? Bacteria employ a hierarchical, three-tiered defense system [21]:

- First Line (Biofilms): Physical barrier formed by extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that restricts agent penetration and creates protective microenvironments.

- Second Line (Cell Envelope): Comprises the cell wall, cell membrane, and encased efflux pumps that block entry or actively expel threats.

- Third Line (Intracellular Responses): Once a stressor enters the cytoplasm, bacteria alter targets, perform enzymatic detoxification, and activate DNA repair systems like Translesion Synthesis (TLS) and Homology-Dependent Repair (HDR) [22] [21].

Q2: How can we experimentally determine which DNA damage tolerance pathway a cell uses to bypass a specific lesion? The piggyBlock assay is a chromosomal method designed for this purpose. It involves [22]:

- Integrating a specific lesion (e.g., TT-CPD or BP-G) into the mammalian chromosome via piggyBac transposition.

- Isolating individual clonal events where the lesion has been bypassed.

- Sequencing the bypass outcome to identify the molecular signature of the pathway used. Error-prone, mutagenic bypass indicates TLS, while error-free bypass suggests template switching or HDR [22].

Q3: Our engineered probiotic strains show poor desiccation tolerance. What surface engineering strategies can improve their survival? Surface engineering creates a protective microenvironment around the cell. Promising strategies include [19]:

- Bio-inspired Coatings: Polydopamine (PDA) forms a universal, adherent layer that can induce a protective, spore-like dormant state.

- Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Encapsulation: Sequential deposition of oppositely charged polymers (e.g., Chitosan and Alginate) to build a customizable protective shell.

- Nanomaterial Integration: Incorporating nanoparticles into coatings can add functionalities like enhanced stability or reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging.

Q4: A key gene in our study is DRT100. What is its known function in stress tolerance? The DRT100 (DNA-damage repair/toleration 100) gene, characterized in the hyperaccumulator plant Sedum alfredii Hance, plays a critical role in genome stability maintenance under metal stress. When overexpressed in A. thaliana, it confers:

- Enhanced Cd hypertolerance and reduced Cd accumulation in shoots.

- Reduced ROS levels and decreased oxidative damage.

- Improved genome stability, evidenced by reduced DNA strand breaks and chromosomal aberrations under Cd stress [20]. It contains leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domains, often involved in protein-protein interactions [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The piggyBlock Assay for Quantifying DNA Damage Tolerance Pathways

Purpose: To measure the division of labor between Translesion Synthesis (TLS) and Homology-Dependent Repair (HDR) in bypassing a specific DNA lesion in mammalian cells [22].

Workflow:

Materials:

- piggyBlock vector (derived from 5'-PTK-3' piggyBac) [22]

- Lesion-containing oligonucleotides (e.g., with TT-CPD or BP-G) [22]

- Helper plasmid encoding transposase (e.g., mPB or HyPB) [22]

- Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) or other mammalian cell lines [22]

- Jet PEI or similar transfection reagent [22]

Steps:

- Lesion Plasmid Construction:

- Anneal lesion-containing and supporting oligos to form a duplex "lesion core."

- Ligate this core into the BpiI/SfiI-digested piggyBlock vector. Excise the supercoiled ligation product from an agarose gel [22].

- Cell Transfection & Culture:

- Transfect cells in a 10 cm dish with 10 ng of lesion plasmid and transposase-helper plasmid using Jet PEI [22].

- Culture transfected cells for 48-72 hours to allow for integration and lesion bypass.

- Clonal Selection:

- Use appropriate selection (e.g., puromycin) to isolate individual clones. Expand each clone for genomic DNA extraction [22].

- Molecular Analysis:

- Isolate genomic DNA from clones. Use PCR to amplify the genomic region containing the integrated cassette.

- Sequence the PCR product to determine the nucleotide sequence at the lesion site.

Interpretation:

- TLS Bypass: The sequence will show a mutagenic or accurate bypass of the lesion itself.

- HDR Bypass: The sequence will be restored to the wild-type, error-free sequence, indicating the use of the sister chromatid as a template [22].

Protocol 2: Engineering Bacterial Surfaces with Polydopamine (PDA) Coatings

Purpose: To apply a protective PDA coating on beneficial bacteria to enhance tolerance to desiccation and acidic stress [19].

Workflow:

Materials:

- Beneficial bacterial strain (e.g., a probiotic)

- Dopamine hydrochloride

- 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5)

- Shaking incubator

Steps:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest mid-log phase bacterial cells by centrifugation. Wash twice with sterile, pure water to remove media components [19].

- Dopamine Solution: Resuspend the bacterial pellet in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5) to a final OD600 of ~1.0.

- Coating Process: Add dopamine hydrochloride to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 0.5-2 mg/mL. Incubate the mixture at 25-37°C for 30-60 minutes with gentle shaking. The solution will darken as PDA polymerizes [19].

- Collection: Centrifuge the cells to pellet the PDA-coated bacteria. Wash gently with buffer or water to remove unreacted monomers.

- Validation: Confirm coating uniformity using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Test the enhanced stress tolerance by exposing coated and uncoated cells to desiccation, low pH, or oxidative stress and performing viability counts [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| piggyBlock Vector System | Chromosomal integration of specific DNA lesions (e.g., TT-CPD, BP-G) for in vivo DNA damage tolerance studies [22]. |

| HyPB/mPB Transposase | High-efficiency helper plasmid for genomic integration of the piggyBlock cassette [22]. |

| SaDRT100 Gene | A key gene from Sedum alfredii that, when expressed in heterologous systems, confers Cd hypertolerance and maintains genome stability by mitigating oxidative DNA damage [20]. |

| Polydopamine (PDA) | A versatile bio-adhesive polymer used to form a protective, spore-like coating on bacterial surfaces, enhancing survival under GI tract and desiccation stresses [19]. |

| Chitosan & Alginate | Natural polysaccharides used in Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly to create multi-layered, protective microcapsules around individual bacterial cells [19]. |

| Trehalose | A non-reducing disaccharide that acts as a compatible solute and stress protectant, stabilizing proteins and membranes during desiccation [19]. |

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) is an experimental technique that harnesses the power of natural selection under controlled laboratory conditions to engineer microbial cells with enhanced traits for biotechnological applications. By cultivating microorganisms for hundreds to thousands of generations under specified selective pressures, ALE facilitates the accumulation of beneficial mutations that improve fitness in the target environment [23] [24]. This approach has become increasingly valuable in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology for developing robust microbial cell factories capable of withstanding industrial stress conditions, such as the toxicity of end-products, heat, or extremes of pH [11] [3].

Unlike classical genetic engineering, ALE does not require a priori knowledge of the genetic basis for desired phenotypes, allowing for the discovery of novel and complex solutions through the exploration of the genotype-phenotype landscape [25]. The rise of next-generation sequencing and automation has further empowered ALE, enabling researchers to rapidly link selected phenotypes to their underlying genotypes [23] [26].

Fundamental ALE Methodologies and Experimental Design

ALE experiments can be broadly categorized into three main methods, each with distinct advantages and applications. The choice of method depends on the research objectives, the microbial host, and the nature of the selective pressure.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary ALE Methods

| ALE Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Applications | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial Transfer [24] | Repeated transfer of an aliquot of a batch culture to fresh medium at regular intervals. | Easy to automate; suitable for high-throughput parallel experiments; low cost. | Long-term evolution experiments (LTEE); resistance to chemicals; co-culture evolution [23]. | Discontinuous growth; fluctuating environmental conditions; not ideal for aggregating cells. |

| Continuous Culture (Chemostat) [23] [24] | Continuous cultivation in a bioreactor with a constant inflow of fresh medium and outflow of spent culture. | Constant growth rate & population density; tight control over environmental conditions (pH, O₂). | Nutrient-limited evolution; morbidostat for antibiotic resistance; carbon source utilization [23]. | Higher operational cost; potential for biofilm formation; fewer parallel replicates. |

| Colony Transfer [24] | Sequential transfer of single colonies on solid agar plates over many generations. | Introduces a single-cell bottleneck; suitable for cells that aggregate in liquid media. | Mutation accumulation studies; evolution of antibiotic resistance in biofilm-forming species like Mycobacterium [24]. | Low-throughput; difficult to automate; limited control over the growth environment. |

Workflow of a Typical ALE Experiment

The following diagram outlines the generalized workflow of an ALE experiment, from design to analysis.

ALE for Enhancing Microbial Tolerance to Industrial Conditions

In industrial bioprocesses, microbial cell factories are often inhibited by the accumulation of toxic end-products (e.g., alcohols, organic acids) or harsh environmental conditions [3]. ALE is a powerful tool to enhance microbial robustness under these stresses. The strategies can be conceptualized based on the spatial level of the engineered tolerance.

Table 2: ALE Applications in Engineering Tolerant Phenotypes

| Targeted Stress/Industrial Condition | Microbial Host | ALE Strategy | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic End-Products (e.g., Fatty Alcohols, Organic Acids) | E. coli, S. cerevisiae | Serial transfer in progressively higher concentrations of the toxic compound. | Improved membrane integrity and efflux capacity; increased product titer and yield. | [3] |

| Inhibitory Bio-product Accumulation (Citrate) | E. coli | Long-term serial transfer in minimal media with citrate as a potential carbon source. | Evolution of aerobic citrate utilization, a trait not native to the wild-type strain under these conditions. | [24] |

| Antibiotic Resistance | E. coli, M. smegmatis | Serial transfer or colony transfer with escalating drug concentrations or on drug-gradient plates. | Identification of resistance mechanisms; study of evolutionary dynamics. | [24] |

| Stressful Environmental Conditions (pH, Temperature) | Various Bacteria and Yeasts | Continuous culture in chemostats or serial batch culture under constant stress. | Selection of strains with improved growth and survival under sub-optimal fermentation conditions. | [23] |

Mechanisms of Evolved Tolerance

The following diagram illustrates the multi-level defense mechanisms that microbes can evolve through ALE to cope with industrial stress conditions, particularly toxic chemicals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for ALE Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemostat Bioreactors | Enables continuous cultivation with precise control over growth rate and environment. | Small-volume, parallel bioreactor systems (e.g., from DASGIP, BioFlo) allow for multiple, controlled ALE lines [23]. |

| Automated Cultivation Systems | High-throughput serial transfer cultivation; reduces manual labor and improves reproducibility. | Platforms like the eVOLVER system can run dozens of turbidostat-based ALE experiments in parallel [24]. |

| Selective Agents | Applies the selective pressure to drive evolution. | Toxic end-products (e.g., octanoic acid), antibiotics, alternative carbon sources (e.g., xylose, citrate) [24] [3]. |

| DNA Sequencing Kits | For whole-genome resequencing of evolved clones to identify causal mutations. | Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms (e.g., Illumina) are standard for post-ALE genotypic analysis [23] [26]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic capacities and identification of engineering targets. | GEMs for hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae help calculate maximum theoretical yields (YT) and plan ALE strategies [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My ALE experiment shows no signs of fitness improvement even after 100 generations. What could be wrong? A: This lack of adaptive response can stem from several factors:

- Insufficient Mutational Supply: The population size might be too small to generate beneficial mutations. Increase your inoculum size or use mutagenesis strains to elevate the mutation rate.

- Excessive Selection Pressure: If the selective condition is too harsh (e.g., a concentration of a toxin that completely inhibits growth), it may kill the entire population before a beneficial mutation can arise. Consider starting with a milder stress level and gradually increasing it.

- Incorrect Choice of Selective Condition: Ensure that the phenotype you wish to improve is directly linked to growth advantage or survival in your chosen condition. If not, consider alternative selection strategies [23] [24].

Q2: How do I decide between serial transfer in flasks and continuous culture in a chemostat for my project? A: The choice depends on your research goal.

- Use serial transfer for its simplicity, low cost, and high parallelization. It is ideal for selecting for faster growth in nutrient-rich conditions or for traits where fluctuating environments are acceptable [23].

- Use chemostat (continuous) culture when you need to maintain a constant growth rate, enforce nutrient limitation, or require tight, consistent control over environmental parameters like dissolved oxygen and pH. This method is more expensive and less parallelizable but is superior for studying adaptation to specific nutrient limitations [23] [24].

Q3: I have isolated an evolved strain with a desired phenotype, but it shows severe growth defects in other conditions. What is happening? A: This is a classic example of an evolutionary trade-off. Adaptation to a specialized environment often comes at the cost of performance in other conditions. This can be due to mutations that optimize one function while disrupting another (e.g., reallocating cellular resources). To mitigate this, you can:

- Perform ALE in a condition that more closely mimics the final application, including shifting or multi-stress conditions.

- Use genome sequencing to identify the mutations responsible for the trade-off and use rational engineering to remove detrimental changes while keeping the beneficial ones [23] [3].

Q4: How many generations are typically needed to observe a significant phenotypic improvement? A: The required timescale varies, but many studies report significant fitness increases within 100 to 500 generations (several weeks to a few months). The degree of improvement and the time required depend on the complexity of the trait, the selection pressure, and the organism. Some studies continue for over 1,000 generations to achieve more profound adaptations [23] [24].

Q5: My evolved population seems to be a mixture of different genotypes. How do I find the best performer? A: This phenomenon, known as clonal interference, is common in ALE. The solution is to:

- Isolate single clones from the evolved population by streaking on solid media.

- Screen these individual clones for the desired phenotype.

- Sequence the genomes of the top-performing clones to identify the combination of mutations conferring the best phenotype [23] [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between strain "tolerance" and "robustness" in an industrial bioprocess context? A1: While often used interchangeably, these terms describe distinct strain characteristics. Tolerance refers to a strain's ability to grow or survive when exposed to a single specific stressor (e.g., high lactate concentration), typically measured by growth-related parameters like viability or specific growth rate. Robustness is a broader, more critical property for production, defined as the ability of a strain to maintain stable production performance (titer, yield, and productivity) in the face of various predictable and stochastic perturbations encountered during scale-up, such as metabolic imbalance, substrate variability, or by-product toxicity. A robust strain must be tolerant, but a tolerant strain does not guarantee robust production [28].

Q2: My engineered production strain grows well in the lab but performs poorly in a bioreactor. What could be the cause? A2: This is a common challenge often stemming from a lack of robustness. Lab conditions are typically optimized and stable, whereas industrial bioreactors present a complex and dynamic environment. Key factors include:

- Metabolic Burden: Expression of heterologous pathways competes with the host for cellular resources like ribosomes and metabolites, perturbing the evolved optimal balance for growth and leading to metabolic imbalance [29].

- Product/Substrate Toxicity: The accumulation of the target product (e.g., organic acids like lactate) or inhibitors in the feedstock can stress the cells, limiting growth and production capacity [30].

- Genetic Instability: The engineered genetic constructs may not be stable over many generations in non-selective, large-scale fermentation.

Q3: What are the main strategic approaches for enhancing microbial robustness? A3: Strategies can be broadly categorized into non-rational and (semi-)rational approaches [28]:

- Non-Rational: These methods do not require prior knowledge of the genetic basis for robustness.

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Long-term cultivation under selective pressure to force the evolution of desired traits.

- Random Mutagenesis: Using physical (e.g., UV, ARTP) or chemical agents to introduce random mutations.

- (Semi-)Rational: These methods use genomic knowledge to guide engineering.

- Transcription Factor Engineering: Reprogramming global cellular regulation to activate multiple stress-response pathways simultaneously.

- Membrane Engineering: Modifying cell membrane composition to improve tolerance against toxic compounds.

- Computational Design: Using genome-scale models (GEMs) and machine learning to predict beneficial mutations.

Q4: What advanced tools are available for making multiple, simultaneous genomic edits? A4: Multiplex Genome Engineering allows for the simultaneous modification of multiple genomic locations in a single experiment. A leading-edge tool is ReaL-MGE (Recombineering and Linear CRISPR/Cas9 assisted Multiplex Genome Engineering). This technology enables precise, high-efficiency insertion of multiple kilobase-scale DNA sequences into diverse bacterial hosts (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas putida) without off-target errors, dramatically accelerating the engineering of complex traits [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Final Product Titer Despite High Cell Growth

Potential Cause: Suboptimal metabolic flux where the cell prioritizes growth over production. Strains engineered for very high growth may consume most of the substrate for biomass rather than product synthesis [29].

Solutions:

- Implement a Two-Stage Process: Use genetic circuits to separate growth and production phases. First, let the cells grow to a high density without production. Then, induce a genetic "switch" that slows growth and redirects cellular resources toward product synthesis [29].

- Fine-Tune Enzyme Expression: Avoid overexpressing synthesis pathway enzymes alone. Instead, use a "host-aware" approach to balance the expression of host metabolic enzymes (e.g.,

E) and heterologous synthesis enzymes (e.g.,Ep,Tp). For maximum volumetric productivity, designs often require a moderate sacrifice in growth rate coupled with robust synthesis [29].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Engineered Strains with Different Growth/Synthesis Trade-offs

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Growth Rate | Specific Synthesis Rate | Volumetric Productivity | Product Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Growth / Low Synthesis | ~0.06 min⁻¹ | Low | Low | Low |

| Medium Growth / Medium Synthesis | ~0.019 min⁻¹ | Medium | Maximum | Medium |

| Low Growth / High Synthesis | ~0.01 min⁻¹ | High | Low | High |

Data derived from multi-scale modeling of batch culture performance [29].

Problem: Poor Strain Tolerance to a Specific Inhibitor (e.g., Organic Acids, Flavonoids)

Potential Cause: The native cellular machinery is overwhelmed by the stressor, leading to inhibited growth and production.

Solutions:

- Employ Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): Subject the strain to prolonged cultivation under progressively increasing concentrations of the inhibitor. For example, ALE was successfully used to enhance E. coli W's tolerance and performance in a flavonoid glycosylation process [32].

- Engineer Global Transcription Factors: Use Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) to reprogram cellular stress responses. For instance:

- Target Specific Mechanisms: Overexpress native or heterologous efflux pumps to expel toxins, or engineer membrane composition to reduce permeability.

Table 2: Selected Transcription Factors for Engineering Robustness

| Transcription Factor | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Improved Trait | Effect on Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoD | E. coli | gTME (mutant library) | Ethanol, SDS tolerance | Increased lycopene yield |

| rpoD | Z. mobilis | gTME | Ethanol tolerance (9%) | Two-fold increase in ethanol production |

| CRP | E. coli | Mutant overexpression (K52I/K130E) | Osmotic tolerance (0.9 M NaCl) | Not Detected |

| irrE (from D. radiodurans) | E. coli | Heterologous expression | Ethanol, butanol tolerance | 10-100x higher tolerance |

| Haa1 | S. cerevisiae | Mutant overexpression (Haa1S135F) | Acetic acid tolerance | Not Detected |

Data compiled from review of proven robustness strategies [28].

Problem: Inefficient Metabolic Flux Toward Target Metabolite

Potential Cause: Native regulation tightly controls key precursors, and introducing a heterologous pathway may not be sufficient to overcome this regulation.

Solutions:

- Use Multiplex Genome Engineering (ReaL-MGE): Simultaneously target multiple nodes in a metabolic network. This was demonstrated for enhancing intracellular malonyl-CoA levels. In a single round in E. coli, ReaL-MGE was used to alter 14 genomic sites, leading to a 26-fold increase in malonyl-CoA and an 11.4-fold improvement in the yield of the polyketide aloesone [31].

- Knock Out Competing Pathways: Identify and delete genes that divert the key precursor away from your desired product. For example, to boost UDP-glucose for glycosylation, E. coli W was engineered with knockouts in

zwf(redirects carbon from glycolysis) andpgito optimize flux [32].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Enhanced Inhibitor Tolerance

Application: This protocol is used to improve the tolerance and robustness of a microbial strain to a specific stressor, such as a toxic product or inhibitory substrate, without prior knowledge of the genetic basis [30] [32].

Procedure:

- Strain and Medium: Start with your base production strain. Use a defined production medium.

- Inoculation: Inoculate the strain into a flask with the medium containing a sub-lethal concentration of the stressor (e.g., 10 g/L lactate).

- Serial Transfer:

- Incubate the culture under standard conditions (e.g., 30°C, 100 rpm) until mid- to late-exponential phase.

- Transfer a small aliquot (e.g., 1-5% v/v) into fresh medium containing the same or a slightly increased concentration of the stressor.

- Automation Note: For high-throughput ALE, automated systems can be used to maintain hundreds of parallel cultures with serial transfers, ensuring consistent timing and handling [33].

- Progression: Gradually increase the stressor concentration over successive transfers as the population adapts and growth recovers.

- Endpoint and Isolation: Continue the process for a predetermined number of generations (e.g., 100-300) or until a target tolerance level is reached. Isolate single colonies from the final evolved population.

- Screening: Screen the isolated clones for both improved growth under stress and, crucially, maintained or improved production performance.

Protocol: ReaL-MGE for Multiplex Genome Engineering

Application: This protocol enables the simultaneous insertion, deletion, or replacement of multiple large (kb-scale) DNA sequences across the genome in a single experiment [31].

Procedure:

- Design and Synthesis:

- dsDNA Donors: Design double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) HR substrates with homology arms (≥500 bp) flanking the target genomic sites. Generate these via PCR, with phosphorothioate modifications at the 5' ends to protect against exonuclease degradation.

- gRNA Cassettes: Design linear gRNA-expression cassettes, each containing a promoter (e.g., J23119) and the gRNA sequence targeting the wild-type genomic locus. Also protect these with 5' end phosphorothioates.

- Plasmid Introduction: Transform the host strain with a plasmid containing inducible systems for the phage recombinase (e.g., Redγβα under a rhamnose-inducible promoter) and Cas9 (under a tightly regulated, e.g., arabinose-inducible promoter).

- First Recombineering:

- Induce the recombinase system (e.g., with rhamnose).

- Electroporate a mixture of all the designed dsDNA donor fragments into the cells.

- CRISPR Counterselection:

- Induce the Cas9 system (e.g., with arabinose) during the recovery period after the first electroporation.

- Perform a second electroporation with the mixture of all the linear gRNA cassettes (e.g., 200 ng total). Cas9 will cleave the unmodified wild-type genomes, providing a powerful selection for cells that have successfully incorporated the edits at all target sites.

- Screening and Verification: Plate the cells and screen for successful recombinants. Verify the genotypes of the edited strains via PCR and whole-genome sequencing to confirm the absence of off-target mutations.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logic of the ReaL-MGE process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Genome-Scale Engineering of Robust Strains

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Precision gene editing, gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa). | Targeted gene knockouts, biosensor-assisted high-throughput screening for lactate production [30]. |

| Recombineering Systems (Red/ET) | Homology-based genetic engineering using phage proteins; enables use of ss-oligos or dsDNA. | Core component of MAGE and ReaL-MGE for multiplexed genome editing [34] [31]. |

| Automated Cultivation Systems (e.g., eVOLVER) | High-throughput, automated serial transfer for ALE experiments. | Enables parallel evolution of dozens to hundreds of lines under different stress conditions [33]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models predicting metabolic flux; identify key gene targets for knockout/overexpression. | "Host-aware" modeling to design strains that optimize culture-level productivity and yield [29]. |

| Physical Mutagens (ARTP, HIBM) | Atmospheric Room-Temperature Plasma & Heavy Ion Beam Mutagenesis; generate diverse random mutation libraries. | Used in Zymomonas mobilis to generate mutants with improved lactate tolerance [30]. |

| Global Transcription Factor Libraries | Mutant libraries of global regulators (e.g., rpoD, CRP) for gTME. | Reprogramming global gene expression to enhance complex phenotypes like ethanol tolerance [28]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers employing CRISPR, biosensors, and microfluidics to enhance microbial tolerance to industrial conditions. The content is designed to help you identify and resolve specific issues encountered during experimental workflows.

Troubleshooting CRISPR Screening in Microbial Systems

FAQ: How can I improve the accuracy of my CRISPR screen in a complex microbial population?

Issue: High noise and inaccurate hit calling in pooled CRISPR screens due to population heterogeneity and bottleneck effects during microbial cultivation.

Solution: Implement an internally controlled screening method like CRISPR-StAR (Stochastic Activation by Recombination) to overcome intrinsic and extrinsic heterogeneity [35]. This method uses Cre-inducible sgRNA expression and single-cell barcoding to generate clonal, single-cell-derived internal controls.

Protocol: CRISPR-StAR for Enhanced Screening Accuracy [35]

- Library Cloning: Clone your sgRNA library (e.g., 5,870 sgRNAs targeting 1,245 genes) into the CRISPR-StAR backbone vector.

- Cell Transduction: Transduce microbial cells expressing Cas9 and Cre::ERT2 at a high representation (≥ 1,000 cells per sgRNA).

- Selection & Bottlenecking: After selection, subject the cell population to an artificial bottleneck via limiting dilution to simulate low survival rates.

- Clone Expansion: Re-expand the cells to over 1,000 cells per sgRNA.

- Induction: Induce Cre::ERT2 recombinase with 4-OH tamoxifen to stochastically activate the sgRNA in only a portion of each clone's progeny, creating the internal control.

- Harvest and Sequence: Harvest cells after a suitable phenotypic selection period (e.g., 14 days) and quantify the abundance of active versus inactive sgRNAs within each clonal barcode population.

Troubleshooting Table: Common CRISPR Screening Challenges

| Challenge | Root Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| High off-target effects [36] | Mismatches between guide RNA and off-target DNA. | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants, truncated guide RNAs (tru-gRNAs), or paired Cas9 nickases. |

| Poor screen resolution in vivo [35] | Bottleneck effects and skewed clonal expansion during engraftment. | Adopt internally controlled methods (e.g., CRISPR-StAR) and use unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) for clonal tracking. |

| Low editing efficiency [37] | Inefficient delivery of CRISPR components or poor gRNA design. | Optimize gRNA design for target site, ensure efficient delivery (e.g., via lentivirus), and verify Cas protein activity. |

| PAM sequence limitation [36] | Cas protein's reliance on a specific Protospacer Adjacent Motif. | Explore natural Cas orthologs with different PAM requirements or use engineered PAM-free nucleases. |

Diagram: Workflow for Internally Controlled CRISPR Screening

CRISPR Screening with Internal Control

Troubleshooting Microfluidic Device Integration

FAQ: My microfluidic device is experiencing clogging and inconsistent results during long-term microbial culture. What can I do?

Issue: Clogging, contamination, or fluid flow inconsistency in microfluidic devices used for high-throughput screening of microbial cultures.

Solution: Address the core challenges of fluid control, contamination prevention, and material compatibility through integrated design and protocol optimization [38] [39].

Protocol: Microfluidic Workflow for CRISPR-based Screening [36]

- Device Design: Select a valved or droplet-based microfluidic chip design suitable for your application (e.g., continuous culture or single-cell encapsulation). Ensure channel geometry minimizes dead volumes and facilitates laminar flow [39].