Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Fluxes in Yeast: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic regulation of metabolic fluxes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a pivotal model in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Fluxes in Yeast: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic regulation of metabolic fluxes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a pivotal model in systems biology and metabolic engineering. We explore the foundational principles of metabolic flux control, detailing advanced methodologies like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), 13C-MFA, and novel computational approaches such as SIMMER for uncovering regulatory mechanisms. The content addresses common challenges in flux quantification and model uncertainty, offering optimization strategies. Furthermore, we examine rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of different modeling frameworks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review highlights how understanding yeast flux regulation provides critical insights into human metabolic diseases, including cancer, and informs therapeutic discovery.

Unveiling the Core Principles of Metabolic Flux Dynamics in Yeast

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) stands as a powerful investigative tool within the realm of systems biology, providing a dynamic lens through which we can examine the intricate flow of molecules within living organisms [1]. Unlike static snapshots offered by traditional metabolomics, MFA quantitatively describes the flow of metabolites through intricate metabolic pathways, enabling researchers to decipher the rate at which metabolites move through these pathways and shedding light on the driving forces behind cellular energy production, growth, and product synthesis [2] [1]. In the context of yeast research, understanding the dynamic regulation of these metabolic fluxes is paramount for unraveling how these organisms adapt their metabolism in response to genetic and environmental perturbations. This application note details the core methodologies and applications of MFA, with a specific focus on its implementation in studying the dynamic metabolic networks of yeast.

Core Principles and Methodologies of MFA

At its core, MFA is the simultaneous identification and quantification of metabolic fluxes, interpreted numerically as the relative fraction of a specific metabolite [2]. These fluxes allow investigators to probe the effect of genetic and environmental modifications on a vast set of reactions that define the metabolism and physiology of cells. Over the years, several flux analysis techniques have been developed, each with specific applications and requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Abbreviation | Use of Labeled Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | No | Yes | No | Genome-scale prediction of fluxes using mathematical optimization [2] |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | No | Yes | No | Smaller-scale analysis focused on central carbon metabolism [2] |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Yes (e.g., 13C) | Yes | Yes | Highly accurate quantification of fluxes in central metabolism [2] [3] |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | 13C-INST-MFA | Yes | Yes | No | Rapid sampling before isotopic steady state is reached; useful for slow-growing cells [2] |

| Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis | DMFA | No | No | No | Tracking flux changes over time in non-steady state cultures [2] |

The most informative and widely adopted method is 13C-MFA [2]. This technique involves feeding cells a substrate enriched with a stable isotope, most commonly carbon-13 (13C) [2] [3]. As the cells grow, the labeled carbon atoms are incorporated into the metabolic network. The resulting distribution of isotopes within intracellular metabolites is measured using analytical techniques such as Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [2]. Computational models are then used to infer the intracellular flux map that best fits the experimentally observed isotope labeling patterns [3].

Experimental Protocol: 13C-MFA in Yeast

Objective: To quantify the in vivo metabolic fluxes of S. cerevisiae under glucose-limited conditions.

Procedure:

- Pre-culture and Growth: Inoculate the yeast strain into a standard growth medium (e.g., YPD or synthetic complete medium) and grow overnight to mid-exponential phase.

- Tracer Experiment: Harvest cells and transfer them into a fresh, well-defined medium where the sole carbon source is a 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-13C] glucose). This ensures that all carbon entering metabolism is from the labeled tracer [2].

- Cultivation and Sampling: Cultivate the cells under controlled conditions (temperature, pH, aeration). Once metabolic steady state is achieved (constant growth rate and metabolite concentrations), sample the culture rapidly.

- Quenching and Metabolite Extraction: Quench cellular metabolism instantly using cold methanol or other quenching solutions to "freeze" the metabolic state. Extract intracellular metabolites using a suitable solvent system like cold methanol/water [2].

- Analytical Measurement: Analyze the metabolite extract using GC-MS or LC-MS to determine the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of key metabolites from central carbon metabolism (e.g., amino acids, organic acids) [2]. The MID represents the fractions of a metabolite with different numbers of 13C atoms.

- Data Integration and Computational Modeling:

- Utilize a genome-scale metabolic model of yeast (e.g., iMM904) [4].

- Input the measured MIDs and extracellular uptake/secretion rates into a flux analysis software platform (e.g., OpenFLUX, INCA) [2].

- The software performs an iterative optimization to find the flux distribution that minimizes the difference between the simulated and experimentally measured MIDs [3].

- Employ statistical analysis (e.g., Monte Carlo sampling) to estimate confidence intervals for the calculated fluxes.

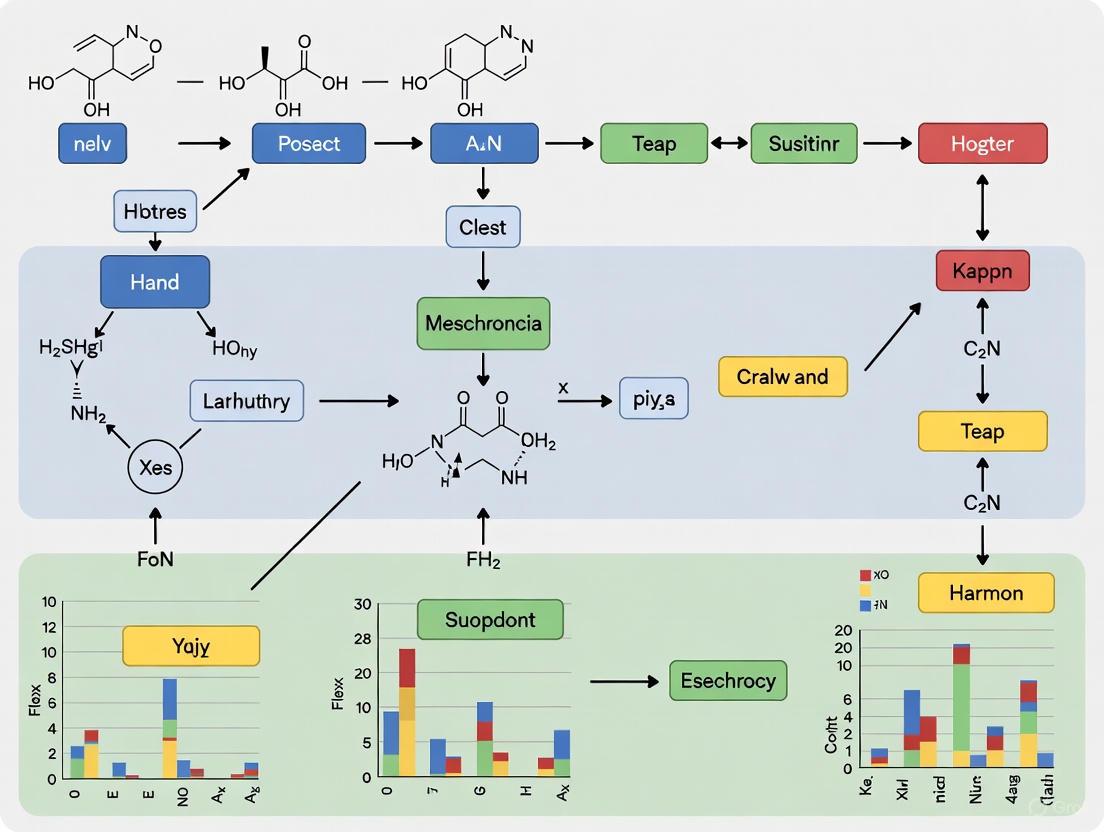

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA experimental and computational workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of 13C-MFA requires a specific set of research reagents and tools, as outlined below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Serves as the isotopic source for tracing carbon atoms through metabolic pathways. | [1,2-13C] Glucose; [U-13C] Glucose; 13C-CO2 [2] |

| Quenching Solution | Instantly halts all metabolic activity to preserve the in vivo metabolic state at the time of sampling. | Cold Methanol Buffer [2] |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvent | Disrupts cells and extracts polar and non-polar intracellular metabolites for analysis. | Cold Methanol/Water mixture [2] |

| Analytical Instrumentation | Identifies and quantifies the isotopic labeling patterns (mass isotopomers) of metabolites. | GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry), LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-MS) [2] [3] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | A computational representation of the organism's metabolism, essential for simulating fluxes. | S. cerevisiae iMM904 model [4] |

| Flux Analysis Software | Platform for integrating experimental data and performing computational flux optimization. | INCA, OpenFLUX, Metran [2] |

MFA in Action: Decoding Dynamic Regulation in Yeast

MFA transitions from a technical methodology to a pivotal biological tool when applied to elucidate dynamic metabolic regulation. A prime example is its use in studying the Yeast Metabolic Cycle (YMC) and epigenetic regulation.

In S. cerevisiae, metabolic fluxes oscillate robustly under glucose-limited conditions [5] [4]. Researchers have leveraged MFA, integrated with transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and epigenomic (ChIP-seq) data, to investigate the interplay between metabolic flux and histone modifications [5] [4]. Using constraint-based models, studies have inferred the production fluxes of two key metabolic cofactors: acetyl-CoA and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) [4]. The results demonstrated that the fluxes leading to acetyl-CoA and SAM are asynchronous during the YMC, suggesting distinct regulatory roles [5] [4]. Acetyl-CoA flux dynamics correlated with the acetylation of histone H3K9 (H3K9Ac) on genes associated with metabolic functions, while SAM flux dynamics correlated with the trimethylation of histone H3K4 (H3K4me3) on genes linked to translation [4]. This provides a direct link between the dynamic flow of metabolism and the regulation of gene expression.

Diagram 2: Dynamic metabolic-epigenetic regulatory loop in yeast.

Beyond fundamental science, MFA is indispensable in metabolic engineering for optimizing yeast as a cell factory. It helps identify metabolic bottlenecks—where flux is constrained—that limit the production of desired compounds, such as biofuels or oleochemicals [6] [1]. For instance, in oleaginous yeasts like Yarrowia lipolytica, MFA can guide strategies to rewire central metabolism, boosting the production titers of fatty acid-derived products by dynamically regulating competing pathways [6].

Emerging Frontiers and Future Perspectives

The field of MFA continues to evolve rapidly. A significant trend is the move away from steady-state analyses toward dynamic and single-cell flux measurements [2] [7]. Methods like 13C-DMFA (Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis) are being developed to capture flux transients in batch cultures, providing a more complete view of metabolic adaptation [2].

Furthermore, the integration of MFA with other omics data types through machine learning (ML) is a promising frontier [8]. Supervised ML models trained on transcriptomics and/or proteomics data have shown potential in predicting metabolic fluxes with high accuracy, potentially complementing traditional constraint-based modeling approaches [8]. Another emerging approach involves inferring genome-scale flux wiring directly from large-scale transcriptional perturbation datasets, as demonstrated in C. elegans, a strategy that could be readily adapted to yeast systems [7].

In conclusion, Metabolic Flux Analysis provides an indispensable quantitative framework for systems biology. Its application in yeast research, from unraveling dynamic metabolic-epigenetic interplay to engineering efficient microbial cell factories, underscores its central role in advancing our understanding and manipulation of biological systems.

Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) provides a quantitative framework for understanding the distribution of control within metabolic pathways, moving beyond the outdated concept of a single 'rate-limiting step' [9]. For researchers engineering yeast metabolism, a core principle is the Flux Control Coefficient (FCC), defined as the fractional change in steady-state pathway flux ((J)) resulting from a fractional change in the activity of a specific enzyme ((E_i)) [10] [11] [12]. The FCC is formally expressed as:

[ C{Ei}^{J} = \frac{dJ}{dEi} \cdot \frac{Ei}{J} = \frac{d \ln J}{d \ln E_i} ]

The Summation Theorem states that the sum of all FCCs in a pathway equals 1 [12]. This confirms that control is shared among multiple steps; an FCC of 0.15 for an enzyme means that a 1% increase in its activity yields a 0.15% increase in pathway flux [11] [12]. A related concept, the Group Flux Control Coefficient (gFCC), extends this analysis to a group of reactions manipulated simultaneously, where the gFCC is the sum of the individual FCCs of the reactions within that group [10].

Quantitative Data and Key Findings in Yeast

Systems-level studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have quantified the relationships between enzyme levels, metabolite concentrations, and metabolic fluxes across 25 different steady-state, nutrient-limited conditions [13] [14]. The following table summarizes the primary flux control findings from these studies.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings from Yeast MCA Studies

| Study Focus | Key Finding | Quantitative Impact | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Flux Control | Substrate concentrations are the strongest driver of metabolic reaction rates [13]. | Metabolite concentrations had more than double the physiological impact of enzyme levels on net reaction rates. | Chemostat cultures with varying nutrient limitations. |

| Flux-Enzyme Correlation | Flux changes correlate better with pathway-level enzyme levels than with individual enzyme levels [14]. | Pathway-level integration of expression data outperformed single-reaction or whole-network models in predicting flux. | Integration of proteomic data with flux balances analysis (FBA) predictions. |

| Specific Regulatory Interactions | New cross-pathway regulatory mechanisms were identified and verified [13]. | Examples include inhibition of pyruvate kinase by citrate (p < 0.00003; q < 0.02), which curtails glycolytic outflow under nitrogen limitation. | SIMMER analysis combining metabolomic, proteomic, and fluxomic data. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Flux Control

Protocol 1: Direct Determination of FCCs via Genetic Perturbation

This protocol outlines the direct experimental determination of FCCs in yeast by genetically modulating enzyme activity and measuring the consequent flux change [10] [9].

Key Reagents & Strains:

- Yeast Strain: Haploid laboratory strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (e.g., BY4741).

- Plasmids: Multicopy plasmids (e.g., 2µ origin) with strong, inducible promoters (e.g., GAL1, TEF1) for gene overexpression [10]. CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for targeted gene deletion or knockdown.

- Culture Media: Defined synthetic media (e.g., YNB) with a limiting carbon source (e.g., 0.1% glucose) to control growth rate in chemostats.

- Inhibitors: Specific, titratable inhibitors if available for the enzyme of interest.

Methodology:

- Generate Perturbation Series: Create a set of isogenic yeast strains with varying activities of the target enzyme. This can be achieved by:

- Maintain Steady-State Cultures: Grow all strains in controlled chemostats, ensuring that environmental conditions (temperature, pH, nutrient feed) are constant and that the culture has reached a metabolic steady-state (typically >5 generations).

- Measure Steady-State Flux ((J)):

- For glycolytic flux, measure the glucose consumption rate and/or ethanol production rate. For a specific pathway, use (^{13}\mathrm{C})-tracer experiments and metabolic flux analysis (MFA) [13].

- Determine Enzyme Activity ((Ei)):

- Prepare cell-free extracts from steady-state cultures.

- Assay the maximum activity ((V{\text{max}})) of the target enzyme under saturating substrate conditions.

- Calculate FCC:

Protocol 2: The SIMMER Approach for Identifying Reaction-Level Regulation

The Systematic Identification of Meaningful Metabolic Enzyme Regulation (SIMMER) method leverages multi-omics data to identify which factors (substrates, products, enzymes, allosteric regulators) control the flux through individual reactions [13].

Key Reagents & Strains:

- Yeast Cultures: Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown under a wide range of steady-state conditions (e.g., carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, leucine, or uracil limitation at different dilution rates) to generate physiological diversity [13].

- Omics Measurement Kits:

- Proteomics: LC-MS/MS kit for relative and absolute protein quantification (e.g., using (^{15}\mathrm{N})-labeled reference).

- Metabolomics: LC-MS/MS kit for absolute quantification of intracellular metabolites (e.g., using isotope ratio-based internal standards).

- Fluxomics: (^{13}\mathrm{C})-labeled glucose and flux balance analysis constrained by uptake/excretion rates.

Methodology:

- Generate Multi-Omics Dataset: For each steady-state condition, perform parallel measurements of:

- Absolute metabolic enzyme concentrations (Proteomics).

- Absolute metabolite concentrations (Metabolomics).

- Metabolic reaction fluxes (Fluxomics via FBA/MFA).

- Formulate Kinetic Model: For a reaction of interest, use a reversible Michaelis-Menten rate law that accounts for substrate, product, and enzyme concentrations [13].

- Parameter Optimization: Use non-linear optimization to find the kinetic parameters (e.g., (k{\text{cat}}), (Km)) that maximize the consistency between the predicted flux (from metabolite and enzyme data) and the measured flux across all conditions.

- Test for Allosteric Regulation: If the initial model fit is poor ((R^2 < 0.35)), systematically test the effect of including each measured metabolite as a potential activator or inhibitor in the rate law. Use a likelihood ratio test with false discovery rate (FDR) correction to identify significant regulators (e.g., (q < 0.1)) [13].

- Generate Multi-Omics Dataset: For each steady-state condition, perform parallel measurements of:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Yeast MCA Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in MCA | Specific Example / Kit |

|---|---|---|

| Chemostat Bioreactor | Maintains microbial cultures at a constant, nutrient-limited steady-state, essential for reliable flux and concentration measurements. | DASbox Mini Bioreactor System or equivalent. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Enables precise determination of in vivo metabolic fluxes via Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA). | (^{13}\mathrm{C})-Labeled Glucose (e.g., [1-(^{13}\mathrm{C})]-Glucose). |

| LC-MS/MS System | Quantifies absolute levels of proteins (proteomics) and metabolites (metabolomics) from the same sample. | Agilent 6495C Triple Quadrupole LC/MS System. |

| Multicopy Plasmid Kit | For genetic perturbation series; allows controlled overexpression of target enzymes in a deletion background. | Yeast 2µ plasmid vectors with GAL1 or TEF1 promoter. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Toolkit | Enables targeted gene knockouts or precise point mutations for generating specific mutant strains. | CRISPR-Cas9 system with sgRNA expression cassette for S. cerevisiae. |

Data Analysis and Computational Modeling

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA)

Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) is a computational algorithm that predicts relative flux changes by integrating enzyme expression data at the pathway level, rather than relying on single enzymes or the entire network [14].

- Procedure:

- Input Data: Provide a genome-scale metabolic model and relative enzyme levels (from proteomics or transcriptomics) across multiple conditions.

- Calculate Flux Potential: For each reaction, compute a "flux potential" by integrating the expression levels of its cognate enzyme and enzymes in neighboring reactions, weighted by their proximity in the metabolic network.

- Optimize Distance Parameter: Use experimental flux data (e.g., from FBA) to optimize the "distance factor" that defines the size of the network neighborhood, achieving an optimal balance between reaction-specific and network-wide integration [14].

- Predict Flux: The optimized eFPA algorithm can then be applied to predict relative flux levels from new expression datasets (e.g., from human tissues or single-cell RNA-seq), providing insights into metabolic function without performing full MFA.

Alternative Modeling Approaches

For systems with incomplete kinetic information, alternative modeling strategies can be employed:

- White-Box Modeling: Uses detailed, mechanism-based kinetic equations for all reactions. Requires comprehensive knowledge of kinetic parameters and is computationally intensive [15].

- Grey-Box Modeling: Combines traditional kinetic models with an added statistical adjustment term to account for missing regulatory complexity, often providing a better fit than pure white-box models [15].

- Black-Box Modeling: Uses data-driven approaches, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), to learn the relationship between enzyme activities and flux without prior knowledge of kinetics. While powerful, it can be a "black box" and requires large datasets to avoid overfitting [15].

Application in Drug Development and Biotechnology

Understanding FCCs enables rational design in biotechnology and drug discovery. In yeast-based bioproduction, efforts should focus on simultaneously modulating multiple enzymes with significant gFCCs, rather than a single "rate-limiting" enzyme, to enhance flux to a desired product [10] [9]. In anti-fungal or anti-parasitic drug development, potential drug targets are enzymes that exhibit high FCCs in pathways essential to the pathogen but absent or non-essential in the host [15] [9]. For instance, MCA of E. histolytica glycolysis identified 3-phoshoglycerate mutase (PGAM) as a major flux-controlling step, highlighting its potential as a drug target [15].

The Yeast Metabolic Cycle as a Model System for Studying Dynamic Flux Regulation

The Yeast Metabolic Cycle (YMC) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a powerful, naturally synchronized model system for investigating the dynamic regulation of cellular metabolism. Under glucose-limited conditions, yeast populations undergo robust, continuous oscillations in metabolic state, gene expression, and epigenetic modifications. This periodicity provides a unique window to study how metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites flow through biochemical pathways—are regulated over time and how they in turn influence broader cellular processes, from epigenetics to phenotype determination [16] [5] [4].

Studying metabolic fluxes is central to understanding metabolic regulation. However, directly measuring intracellular fluxes is technically challenging. Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) have become indispensable computational tools for inferring these fluxes. These approaches use genome-scale metabolic models, stoichiometric constraints, and optimization principles to predict flux distributions that support observed physiological states [17] [4]. The YMC is an ideal testbed for these methods, as its dynamic nature allows researchers to validate model predictions against oscillating experimental data.

Key Findings and Quantitative Insights from YMC Studies

Research on the YMC has yielded critical quantitative insights into the dynamic coupling between metabolic flux, epigenetics, and gene expression.

Table 1: Dynamic Coupling Between Metabolic Fluxes and Histone Modifications During the YMC

| Metabolic Cosubstrate | Associated Histone Mark | Phase Relationship | Biological Processes Correlated with Mark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA Flux | H3K9Acetylation (H3K9Ac) | Asynchronous dynamics | Metabolic functions |

| S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM) Flux | H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) | Asynchronous dynamics | Translation processes, Cell cycle regulation |

A seminal study integrated flux analysis with multi-omics data to investigate the production fluxes of the epigenetic cosubstrates acetyl-CoA and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). The results demonstrated that the flux dynamics of these two metabolites are asynchronous, suggesting distinct and specialized regulatory roles during the metabolic cycle. Furthermore, the study provided evidence that chromatin accessibility is a precondition for metabolic fluxes to influence the enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K9Ac on gene promoter regions. This supports a model where metabolism provides essential, timely cosubstrates for histone post-translational modifications (PTMs), thereby linking metabolic state directly to the epigenetic landscape [16] [5] [4].

Beyond single genotypes, studies have shown how genetic interactions can rewire metabolic networks. Research on interacting SNPs (MKT189G and TAO34477C) revealed that their combination uniquely activates a latent arginine biosynthesis pathway while suppressing ribosome biogenesis. This metabolic rewiring, which enhances sporulation efficiency, was uncovered by integrating time-resolved transcriptomics, absolute proteomics, and targeted metabolomics, highlighting the power of multi-omics approaches to decode complex metabolic regulation [18].

Table 2: Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques and Their Applications

| Method/Algorithm | Core Principle | Input Data | Application in YMC/Dynamic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Maximizes biomass yield or other objectives subject to stoichiometric constraints | Genome-scale model, exchange fluxes | Predicting fluxomes; basis for more advanced techniques [17] [4] |

| Entropy Maximization CBMs | Predicts fluxomes that can occur in the greatest number of ways (maximum entropy) | Transcriptomic data, uptake rates | Inferring acetyl-CoA/SAM flux without predefined weights; used in YMC epigenetic studies [4] |

| METAFlux | Uses FBA to infer metabolic reaction flux from gene expression | Bulk or Single-cell RNA-seq | Characterizing metabolic heterogeneity and interactions in dynamic systems [17] |

| Enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) | Integrates enzyme expression at the pathway level to predict flux | Proteomic or Transcriptomic data | Robustly predicts relative flux levels; handles single-cell data sparsity [19] |

| Flux-Sum Coupling Analysis (FSCA) | Categorizes metabolite pairs based on interdependencies of their flux-sums | Stoichiometric model, flux distributions | Exploring metabolite concentration interdependencies without direct measurement [20] |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Flux-EPigenetic Coupling in the YMC

This protocol details the procedure for synchronizing a yeast culture in the YMC and analyzing the dynamic relationship between metabolic fluxes and histone modifications.

YMC Synchronization and Sampling

Materials:

- S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., CEN.PK)

- Chemostat system (e.g., Biostat Qplus)

- Glucose-limited defined medium

- Sampling apparatus

Procedure:

- Chemostat Cultivation: Inoculate the yeast strain into a chemostat with a working volume of 1-2 liters. Maintain culture under glucose-limited conditions with a defined medium. Set the dilution rate to 0.09-0.12 h⁻¹, temperature to 30°C, and pH to 4.5. Continuously monitor the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration.

- Synchronization and Monitoring: Allow the culture to reach steady state (typically >10 generations). The YMC is established when robust, high-amplitude oscillations in dissolved oxygen (DO) are observed, with a period of approximately 4-5 hours.

- Time-Course Sampling: Once synchronized, collect samples across one full metabolic cycle (∼5 hours). Sample more frequently during metabolic phase transitions based on the DO trace. The three primary phases are:

- Oxidative (OX): Peak DO consumption.

- Reductive Building (RB): Rising DO.

- Reductive Charging (RC): Peak DO. Process samples immediately for downstream omics analyses.

Multi-Omics Data Acquisition for Flux and Epigenetics

Workflow Diagram: Synchronized Multi-Omics Sampling in the YMC

Materials:

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy)

- Kits for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

- Antibodies: anti-H3K9Ac, anti-H3K4me3

- ATAC-seq kit (e.g., Illumina)

- LC-MS/MS for extracellular metabolite analysis (e.g., acetate, ethanol)

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Transcriptomics (RNA-seq):

- For each time point, collect 5-10 million cells and stabilize RNA using RNAlater or immediate lysis.

- Extract total RNA, ensure RIN > 8.0.

- Prepare stranded RNA-seq libraries and sequence on an Illumina platform to a depth of 20-30 million reads per sample.

Epigenomics (ChIP-seq):

- Cross-link 20 million cells per time point with 1% formaldehyde for 15 min.

- Quench with glycine, lyse cells, and sonicate chromatin to an average fragment size of 200-500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitate with specific antibodies against H3K9Ac and H3K4me3.

- Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare sequencing libraries.

Chromatin Accessibility (ATAC-seq):

- Collect 50,000 viable cells per time point.

- Perform tagmentation using the Th5 transposase as per kit instructions.

- Purify tagmented DNA and amplify with indexed primers for multiplexing.

- Sequence to a depth of 10-20 million reads per sample.

Extracellular Metabolite Measurement:

- Rapidly filter culture broth (0.45 μm filter) to separate cells from medium.

- Analyze filtrate using LC-MS/MS or HPLC to quantify concentrations of key metabolites like glucose, acetate, and ethanol. This data is used to constrain the flux model.

Computational Protocol: Inferring Metabolic Fluxes from YMC Data

This protocol describes the use of constraint-based models to infer dynamic metabolic fluxes, particularly for epigenetic cosubstrates, from transcriptomic data.

Model Preparation and Contextualization

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model for S. cerevisiae (e.g., iMM904 from BiGG Models)

- Constraint-based modeling software (e.g., COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB/Python)

- Transcriptomic data (TPM or FPKM values) from YMC time series.

Procedure:

- Model Import: Load the genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iMM904). This model contains the stoichiometry of all metabolic reactions, gene-protein-reaction rules, and exchange reactions.

- Add Epigenetic Reactions: To study fluxes relevant to epigenetics, add enzymatic reactions that consume acetyl-CoA and SAM for histone modification. For example:

- Add histone acetyltransferase reactions:

Acetyl-CoA + Histone → CoA + Acetyl-Histone - Add histone methyltransferase reactions:

SAM + Histone → SAH + Methyl-Histone

- Add histone acetyltransferase reactions:

- Integrate Transcriptomic Data: Map gene expression values from RNA-seq onto the model reactions. A common method is to create a reaction expression value based on the gene-protein-reaction rules.

Flux Estimation using Entropy Maximization

Workflow Diagram: Computational Flux Inference Pipeline

Given the limitations of traditional FBA for multi-substrate studies, an entropy-maximizing CBM is recommended for its ability to provide a unique solution without predefined weights for multiple cosubstrate fluxes [4].

Procedure:

- Set Constraints: For each YMC time point, apply the measured uptake/secretion rates (e.g., glucose, oxygen, acetate) and the reaction expression constraints to the model. This creates a time-series of condition-specific models.

- Perform Flux Estimation: For each contextualized model, run the optimization to find the flux distribution that maximizes the Shannon entropy of the fluxome. The objective function is

max Σ -vᵢ ln(vᵢ)for all reaction fluxesvᵢ, subject to stoichiometric (Sv=0) and capacity constraints. - Extract Cosubstrate Fluxes: From the resulting flux distribution, extract the production fluxes (flux-sums) for acetyl-CoA and SAM in the relevant cellular compartments (cytosol, nucleus).

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate the correlation between the dynamic fluxes of acetyl-CoA and H3K9Ac enrichment (from ChIP-seq), and between SAM flux and H3K4me3 enrichment, across the YMC time points. Gene ontology analysis of genes whose histone mark enrichment correlates with cosubstrate flux can reveal functional insights.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for YMC and Flux Analysis

| Category / Item | Specific Example / Tool | Function in YMC/Flux Research |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Strain | S. cerevisiae CEN.PK | A well-characterized strain with robust YMC synchronization in chemostats [5] [4]. |

| Cultivation System | Biostat Qplus (Sartorius) | A advanced benchtop chemostat for maintaining continuous, glucose-limited cultures essential for YMC studies. |

| Antibody for ChIP | Anti-H3K9Ac (abcam ab4441) | Immunoprecipitation of acetylated histone H3 (Lys9) for ChIP-seq to map active regulatory elements. |

| Antibody for ChIP | Anti-H3K4me3 (Diagenode C15410003) | Immunoprecipitation of trimethylated histone H3 (Lys4) for ChIP-seq to map active promoters. |

| Chromatin Assay Kit | Illumina Tagment DNA TDE1 Kit | For ATAC-seq library preparation to assess genome-wide chromatin accessibility. |

| Metabolic Model | iMM904 (BiGG Models) | A high-quality, manually curated genome-scale metabolic model of S. cerevisiae for flux balance analysis [4] [20]. |

| Flux Analysis Tool | COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB/Python toolbox for constraint-based modeling and flux prediction [17] [4]. |

| Flux Analysis Tool | METAFlux | A computational pipeline for inferring metabolic fluxes from bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data [17]. |

The Yeast Metabolic Cycle provides a uniquely powerful and dynamic model system for dissecting the principles of metabolic flux regulation. The protocols outlined here—combining rigorous experimental synchronization, multi-omics profiling, and advanced constraint-based modeling—enable researchers to move beyond static snapshots and capture the temporal interactions between metabolism, gene expression, and epigenetics. The insights gained, such as the asynchronous regulation of acetyl-CoA and SAM fluxes and the precondition of chromatin accessibility for their action, underscore the deep functional integration of cellular processes. The continued application and refinement of these approaches in the YMC will be instrumental in building predictive models of metabolic regulation, with broad implications for foundational biology and applied fields like metabolic engineering and drug development.

The dynamic interplay between cellular metabolism and the epigenetic landscape represents a frontier in understanding how eukaryotic cells regulate gene expression and identity. Within the nucleus, histones are subject to post-translational modifications (PTMs) that act as crucial epigenetic regulators of DNA accessibility and transcriptional activity. Acetylation and methylation are among the most studied histone PTMs, and they are directly catalyzed by enzymes that utilize metabolic intermediates as essential co-substrates. Acetyl-CoA serves as the donor for histone acetylation, while S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) acts as the methyl donor for histone methylation [4] [21].

The regulation of these epigenetic marks is therefore intrinsically linked to the availability of their metabolic precursors. However, a critical challenge lies in quantifying the production fluxes of these co-substrates and understanding how their dynamic changes influence the epigenetic landscape. This Application Note details a comprehensive, data-driven workflow to investigate this metabolic-epigenetic interplay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during its Yeast Metabolic Cycle (YMC). The YMC provides an ideal model system, as it exhibits robust, synchronous oscillations in metabolism, gene expression, and histone modifications under glucose-limited conditions [4] [5]. The protocols herein describe how to computationally estimate the fluxes of acetyl-CoA and SAM and correlate them with dynamic changes in histone marks H3K9Ac and H3K4me3, while also accounting for the critical role of chromatin accessibility.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and tools used in the featured studies for investigating metabolic-epigenetic regulation in yeast.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae YMC Model | Biological System | A synchronous, oscillating system for studying dynamic relationships between metabolism, gene expression, and epigenetics [4] [5]. |

| iMM904 Genome-Scale Model | Computational Tool | A high-quality, manually curated metabolic model of S. cerevisiae used to constrain flux balance analysis and estimate metabolic fluxes [4]. |

| Auxin-Inducible Degron (AID) System | Molecular Tool | Enables rapid, conditional depletion of target proteins (e.g., acetyl-CoA carboxylase, Acc1p) to study essential metabolic enzymes without lethal gene deletion [22]. |

| Oryza sativa TIR1 | Genetic Component | The plant auxin receptor expressed in yeast to reconstitute the AID system for targeted protein degradation [22]. |

| RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq Data | Omics Datasets | Used to profile transcriptomics, histone modification enrichment (H3K9Ac, H3K4me3), and chromatin accessibility, respectively [4]. |

| m6A Methyltransferase (Ime4) | Epigenetic Enzyme | An mRNA methyltransferase; its overexpression can be used as a strategy to rewire cellular metabolism and increase flux toward desired pathways [23]. |

Integrated analysis of multi-omics data from the Yeast Metabolic Cycle reveals distinct dynamics and functional associations for acetyl-CoA and SAM.

Table 2: Correlations Between Metabolic Fluxes and Histone Marks During the YMC

| Parameter | Acetyl-CoA / H3K9Ac | SAM / H3K4me3 |

|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Mark | H3K9 Acetylation (H3K9Ac) | H3K4 Trimethylation (H3K4me3) |

| Primary Genomic Location | Gene regulatory elements [4] | Transcription start sites of active genes [4] |

| Flux-Mark Correlation | Positive correlation with acetyl-CoA production flux [4] | Positive correlation with SAM production flux [4] |

| Associated Biological Processes (Gene Ontology) | Metabolic functions [4] [5] | Translation and protein synthesis processes [4] [5] |

| Key Regulatory Metabolite | Acetyl-CoA (K(_m) of Gcn5 KAT: 2.5 μM) [21] | SAM (K(_m) of EZH2 KMT: 1.2 μM) [21] |

| Inhibitory Metabolite | CoA (K(_i) for Gcn5: 6.7 μM) [21] | S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH; K(_i) for EZH2: 7.5 μM) [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Estimating Cosubstrate Production Fluxes Using Constraint-Based Modeling

This protocol outlines the computational estimation of acetyl-CoA and SAM production fluxes by integrating a genome-scale metabolic model with transcriptomic data [4].

Materials:

- High-quality genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iMM904 for S. cerevisiae) [4].

- Context-specific transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq from YMC time points).

- Software for constraint-based modeling (e.g., COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB or Python).

Procedure:

- Model Curation: Augment the base metabolic model (iMM904) with reactions directly involved in histone modification. This includes adding reactions for acetylation and methylation, ensuring metabolites like acetyl-CoA and SAM are consumed, and products like CoA and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) are produced. The network should account for subcellular compartmentalization (e.g., cytosol vs. nucleus) [4].

- Integration of Transcriptomic Data: Map the provided RNA-seq data from multiple YMC time points onto the metabolic model. This step converts gene expression levels into constraints on the fluxes of their associated enzyme-catalyzed reactions, creating a context-specific model for each time point.

- Flux Estimation via Maximum Entropy: Apply a constraint-based model that maximizes the Shannon entropy of the flux distribution. This approach, as an alternative to traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), provides a unique optimal solution and has demonstrated higher predictive performance for yeast and human metabolic networks. It does not require pre-defined weighting parameters for multiple co-substrate fluxes [4].

- Extraction of Cosubstrate Fluxes: From the resulting flux distribution, extract the production fluxes for acetyl-CoA and SAM in the relevant compartment (e.g., cytosolic acetyl-CoA flux) at each time point in the YMC. These flux values are the key output for downstream correlation with epigenetic data.

Protocol 2: Correlating Metabolic Fluxes with Histone Modifications

This protocol describes the methodology for analyzing the relationship between estimated metabolic fluxes and ChIP-seq data for histone marks [4] [5].

Materials:

- ChIP-seq data for histone marks (e.g., H3K9Ac, H3K4me3) across synchronized YMC time points.

- ATAC-seq data for assessing chromatin accessibility.

- Genome annotations (e.g., SacCer2 from UCSC database).

- Bioinformatics software for sequence analysis (e.g., R/Bioconductor).

Procedure:

- Data Synchronization: Align the time points of the ChIP-seq and RNA-seq datasets using a consistent marker of metabolic state, such as oxygen consumption rates. This may involve averaging data from adjacent time points to create a synchronized series [4].

- Calculation of Histone Mark Enrichment: Using the ChIP-seq read counts and genome annotations, compute the enrichment of histone marks (H3K9Ac, H3K4me3) in promoter regions, typically defined as ±500 base pairs around the transcription start site (TSS) of each gene [4].

- Correlation Analysis: For each gene, perform a temporal correlation analysis (e.g., Pearson correlation) across the YMC between the enrichment level of a specific histone mark and the production flux of its corresponding metabolic co-substrate (H3K9Ac vs. acetyl-CoA flux; H3K4me3 vs. SAM flux).

- Integration of Chromatin Accessibility: Incorporate ATAC-seq data to determine the chromatin accessibility state of promoter regions. Test the hypothesis that chromatin accessibility is a precondition for metabolic fluxes to influence histone enrichment by stratifying genes based on their accessibility [4] [5].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis (Gene Ontology): For the sets of genes whose histone mark enrichment significantly correlates with acetyl-CoA or SAM flux, perform Gene Ontology analysis to identify the biological processes they are associated with (e.g., metabolism for acetyl-CoA-linked genes; translation for SAM-linked genes) [4].

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation via Targeted Protein Depletion

This protocol employs the auxin-inducible degron system for conditional, rapid depletion of metabolic enzymes to validate their role in epigenetic regulation [22].

Materials:

- Yeast strain engineered to express the plant auxin receptor Oryza sativa TIR1.

- Strain with an AID tag fused to the gene of interest (e.g., ACC1 for acetyl-CoA carboxylase).

- Synthetic auxin analog (e.g., 1-Naphthaleneacetic Acid, NAA).

- Standard materials for yeast cultivation and analysis (e.g., fluorescence measurement if using a reporter).

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering: Construct yeast strains where an essential metabolic enzyme (e.g., Acc1p) is C-terminally tagged with an optimized auxin-inducible degron (AID). Co-express a codon-optimized *O. sativa TIR1 gene under a medium-strength promoter (e.g., ACS2) in the same strain [22].

- Induction of Protein Depletion: Grow the engineered strain to early log phase (OD600 ≈ 1). Add 1 mM NAA to the culture to induce the degradation of the AID-tagged target protein. An untreated culture serves as a control.

- Monitoring Depletion Efficiency: Track the depletion of the target protein over time. This can be done via Western blot if an antibody is available, or via fluorescence if the target is fused to a reporter like yEGFP. Effective systems can achieve >99% depletion within 3-6 hours [22].

- Downstream Phenotypic Analysis: After confirming protein depletion, measure the consequent effects:

- Metabolic: Quantify changes in intracellular metabolite levels (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, SAM) using mass spectrometry.

- Epigenetic: Perform ChIP-seq or ChIP-qPCR to assess changes in global or gene-specific histone acetylation (e.g., H3K9Ac) or methylation (e.g., H3K4me3).

- Transcriptional: Use RNA-seq to analyze changes in the transcriptome, particularly for genes involved in processes identified in the correlation analysis.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Metabolic-Epigenetic Regulation Workflow

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for analyzing metabolic-epigenetic regulation during the yeast metabolic cycle.

Acetyl-CoA and SAM in Epigenetic Signaling

Diagram 2: Metabolic co-substrates acetyl-CoA and SAM drive histone acetylation and methylation, which are subject to feedback inhibition.

The Impact of Nutrient Limitation on Flux Distribution and Cellular Physiology

Within the broader context of dynamic metabolic flux regulation in yeast research, understanding how nutrient limitations rewire intracellular flux distributions is fundamental for both basic science and applied biotechnology. The carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio in the growth medium is a critical determinant of yeast physiology, acting as a key regulatory input that shapes metabolic network activity, transcriptional programs, and proteome allocation [24]. Saccharomyces cerevisiae deploys distinct metabolic strategies when facing either carbon or nitrogen scarcity, leading to profound differences in flux distribution, energy metabolism, and biomass composition. These physiological adaptations are not merely academic curiosities; they directly impact biotechnological processes including biofuel production, pharmaceutical development, and fermented beverage manufacturing [24]. This Application Note synthesizes recent advances in quantifying and modeling these metabolic adaptations, providing researchers with robust methodologies to investigate flux distributions under nutrient-limited conditions, particularly focusing on the differential responses to carbon versus nitrogen limitation.

Physiological and Metabolic Responses to Nutrient Limitation

Differential Metabolic Responses to Carbon vs. Nitrogen Limitation

Yeast cells exhibit strikingly different metabolic phenotypes depending on whether carbon or nitrogen serves as the growth-limiting nutrient. These differences manifest in energy metabolism, biomass composition, and global regulatory programs.

Table 1: Characteristic Metabolic Responses to Carbon vs. Nitrogen Limitation in S. cerevisiae

| Physiological Parameter | Carbon Limitation | Nitrogen Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Limiting Metabolite | Low pyruvate [25] | Low glutamine [25] |

| Energy Charge | High adenylate energy charge [25] | Low adenylate energy charge [25] |

| Biomass Composition | High protein content [26] | Low protein content; increased lipids/carbohydrates [24] |

| Metabolic Strategy | Maximizes biomass production [24] | Shifts toward storage compound accumulation [24] |

| Crabtree Effect | Induced at high glucose levels [24] | Enhanced ethanol production [24] |

| ATP Homeostasis | Maintained through respiratory regulation [24] | Maintained via alternative futile cycles [24] |

| Proteome Reserve Capacity | ~50% reserve capacity [26] | Minimal reserve capacity [26] |

Nitrogen-limited conditions trigger a substantial reprogramming of cellular economics. When nitrogen availability becomes restricted, cells maintain growth by economizing their proteome, reducing total protein content by up to 50% while preserving flux through central carbon metabolism [26]. This remarkable adaptation demonstrates the extensive reserve capacity built into yeast metabolic networks, with some pathways maintaining >80% reserve capacity under non-limiting conditions [26].

Intracellular Metabolite Signatures of Nutrient Limitation

Metabolomic profiling reveals distinct metabolite signatures associated with different nutrient limitations. These signatures provide functional readouts of the intracellular metabolic state and potential growth rate determinants.

Table 2: Key Metabolite Changes Under Different Nutrient Limitations

| Limiting Nutrient | Metabolite Signature | Concentration Change | Proposed Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (Glucose) | Pyruvate | Decreased [25] | Potential growth rate determinant [25] |

| Nitrogen (Ammonium) | Glutamine | Decreased [25] | Nitrogen status sensor; growth regulator [25] |

| Nitrogen (Ammonium) | Amino Acids (total pool) | Decreased [25] | Reduced biosynthetic capacity |

| Phosphorus (Phosphate) | ATP | Decreased [25] | Phosphorus charge indicator [25] |

| Phosphorus (Phosphate) | Adenylate Energy Charge | Significantly reduced [25] | Energy status indicator |

| Carbon (Glucose) | Nucleotides | Increased [25] | Potential redistribution of resources |

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual relationship between nutrient limitation, intracellular metabolites, and growth rate:

Experimental Protocols

Chemostat Cultivation for Nutrient-Limited Steady-State Studies

Purpose: To establish precisely controlled nutrient-limited conditions for studying flux distributions and physiological responses.

Procedure:

- Medium Preparation:

- For nitrogen limitation: Use mineral medium with fixed carbon source (e.g., 20 g/L glucose) and progressively reduce ammonium sulfate concentration to achieve C/N ratios from 5 (carbon-limited) to 115 (severely nitrogen-limited) [26].

- For carbon limitation: Maintain excess nitrogen while limiting glucose concentration (typically 2-10 g/L).

Inoculum Preparation:

- Grow a single colony overnight in 3 mL batch culture using complete medium.

- Inoculate chemostat with 0.5-1 mL of pre-culture.

Chemostat Operation:

- Use 500 mL chemostat vessels with 300 mL working volume.

- Maintain constant dilution rate (typically 0.05-0.30 h⁻¹) using peristaltic pumps.

- Control environmental parameters: temperature (30°C), pH (5.0, maintained with automatic KOH addition), aeration (5 L/min humidified air), agitation (400 rpm) [25].

Steady-State Confirmation:

- Monitor culture density (Klett units), cell count, and mean cell size for at least 5 volume changes.

- Sample only after these parameters stabilize for >24 hours.

Sampling:

- Take multiple samples over consecutive days (minimum 4 time points) to confirm steady-state maintenance.

- Process samples immediately for metabolite, transcriptome, and proteome analysis.

Metabolome Sampling and Extraction Protocol

Purpose: To accurately capture intracellular metabolite levels without significant turnover or degradation.

Materials:

- Pre-chilled methanol (-80°C)

- Extraction solvent (acetonitrile:methanol:water, 40:40:20, -20°C)

- Pre-chilled centrifuge (-10°C) with JA-25.50 rotor

- 0.45 μm pore size nylon filters (Millipore)

- Liquid nitrogen for flash freezing

Option A: Methanol Quenching Method [25]

- Rapidly transfer 10 mL culture broth into 20 mL of -80°C methanol.

- Centrifuge immediately for 5 min at 4000 rpm in -80°C pre-chilled rotor at -10°C.

- Discard supernatant and add 0.4 mL of -20°C extraction solvent to pellet.

- Vortex thoroughly and extract for 15 min at 4°C.

- Centrifuge and transfer supernatant to fresh tube.

- Repeat extraction with additional 0.4 mL solvent.

- Pool supernatants (total volume 0.8 mL).

- Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until analysis.

Option B: Vacuum Filtering Method [25]

- Rapidly sample 10 mL culture and vacuum filter through 0.45 μm nylon filter.

- Immediately transfer filter to 0.6 mL of -20°C extraction solvent.

- Extract for 15 min at -20°C.

- Wash filter with 0.1 mL additional solvent.

- Centrifuge at 4°C and transfer supernatant.

- Repeat extraction with 0.1 mL solvent.

- Pool supernatants (total volume 0.8 mL).

- Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

¹³C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA) Protocol

Purpose: To quantify metabolic flux distributions in central carbon metabolism under nutrient-limited conditions.

Procedure:

- Labelled Substrate Preparation:

- Prepare medium with identical composition to steady-state chemostat medium but with [1,2-¹³C] glucose, [1,6-¹³C] glucose, or uniformly labelled [U-¹³C] glucose as carbon source [2].

- Filter-sterilize labelled medium (0.22 μm pore size).

Isotopic Steady-State Achievement:

- Once metabolic steady state is confirmed in chemostat, switch feed to labelled medium.

- Maintain same dilution rate for sufficient time to reach isotopic steady state (typically 5-7 residence times).

- Confirm isotopic steady state through time-series sampling until isotope enrichment stabilizes.

Sampling for Flux Analysis:

- Collect biomass samples as described in Protocol 3.2.

- Analyze isotopic labeling patterns in proteinogenic amino acids and intracellular metabolites.

Analytical Methods:

Computational Flux Analysis:

- Utilize modeling software (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX) to estimate metabolic fluxes.

- Apply elementary metabolite unit (EMU) modeling to reduce computational complexity [2].

- Validate flux estimates with experimental measurements of extracellular rates.

The experimental workflow for comprehensive flux analysis is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nutrient Limitation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotopes | [1,2-¹³C] glucose; [U-¹³C] glucose; ¹³C-NaHCO₃ | Tracers for ¹³C-MFA to quantify metabolic fluxes [2] |

| MS Internal Standards | UPS2 Proteomic Dynamic Range Standard; isotope-labeled ATP, glutamine, glutamate | Absolute quantification of metabolites and proteins [25] [26] |

| Chromatography Columns | Aminopropyl stationary phase (HILIC); C18 with tributylamine ion-pairing | Metabolite separation for LC-MS/MS analysis [25] |

| Culture Systems | Sixfors 500 mL chemostats; 0.22 μm sterilization filters | Precise control of nutrient-limited growth conditions [25] |

| Extraction Solvents | Acetonitrile:methanol:water (40:40:20, -20°C) | Metabolite quenching and extraction [25] |

| Proteomics Reagents | Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) reagents; iBAQ standards | Multiplexed protein quantification [26] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | ATP determination kits; NADPH/NADP+ assay kits | Validation of energy metabolism changes |

| Yeast Strains | FY derivatives (DBY11069, DBY11167); oleaginous yeasts (R. toruloides, Y. lipolytica) | Model systems for nutrient limitation research [25] [27] |

Computational Modeling Approaches

Coarse-Grained Kinetic Modeling of Nutrient Limitations

The coarse-grained modeling approach has proven particularly valuable for integrating multi-omics data and generating testable hypotheses about metabolic regulation under nutrient limitations. These models reduce biological complexity by grouping entities with similar functions into single variables, creating manageable yet insightful representations of yeast physiology [24].

Key Model Components:

- Proteome Sectors: Proteins are categorized into functional sectors (e.g., R-sector for transcription/translation machinery, E-sectors for metabolic enzymes, Z-sector for remaining proteome) [24].

- Nutrient Assimilation Modules:

- Carbon assimilation through glycolysis and central metabolism

- Nitrogen assimilation through ammonium incorporation into glutamate/glutamine

- Explicit lipid metabolism to capture biomass composition changes

- Regulatory Loops: Feedback inhibition, nutrient sensing, and growth rate control

Implementation Insights:

- The model successfully captures differential metabolic characteristics under carbon- vs. nitrogen-limited conditions [24].

- It highlights the significance of protein activity regulation at varying C/N ratios [24].

- The framework elucidates distinct ATP homeostasis maintenance strategies under different nutrient limitations [24].

The regulatory network connecting nutrient sensing to metabolic outputs can be visualized as:

The investigation of nutrient limitation effects on flux distribution and cellular physiology reveals the remarkable plasticity and strategic resource allocation capabilities of yeast cells. The differential responses to carbon versus nitrogen limitation—from metabolic flux redistributions to proteome economization—highlight the sophisticated regulatory networks that maintain cellular functionality across diverse nutrient environments. The methodologies outlined in this Application Note, particularly the integration of chemostat cultivation with multi-omics analyses and computational modeling, provide researchers with powerful tools to dissect these complex phenomena. As metabolic engineering and synthetic biology applications continue to advance, understanding these fundamental principles of nutrient-responsive regulation will be crucial for optimizing microbial cell factories and developing novel biotechnological processes.

Advanced Techniques for Measuring and Modeling Metabolic Fluxes

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) represents a powerful computational approach for simulating and predicting the metabolic behavior of biological systems, particularly when detailed kinetic parameters are unavailable. This methodology has revolutionized our ability to investigate and engineer microbial metabolism, with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serving as its cornerstone technique [28]. FBA enables researchers to predict steady-state metabolic fluxes by leveraging genome-scale metabolic reconstructions, which catalog all known biochemical reactions within an organism based on its genomic information [28]. For yeast research, specifically studies involving Saccharomyces cerevisiae, these approaches have become indispensable tools for unraveling the complex regulation of metabolic fluxes and designing optimized strains for industrial biotechnology and therapeutic production.

The fundamental principle underlying FBA is the application of mass-balance constraints to metabolic networks, effectively describing the production and consumption of each metabolite within the system. This constraint-based framework has been extensively applied to yeast metabolism, enabling researchers to predict how intracellular flux distributions shift in response to genetic modifications or environmental perturbations [29]. By simulating metabolic behavior under different conditions, FBA provides valuable insights into the dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways that would be challenging to obtain through experimental approaches alone. The extension of FBA to Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) further enhances its utility by incorporating time-dependent changes in extracellular metabolites, allowing researchers to model batch fermentation processes and transient metabolic states highly relevant to industrial applications [29] [30].

Within the context of yeast research, these modeling approaches have been instrumental in advancing our understanding of eukaryotic metabolic regulation and facilitating the engineering of yeast strains for improved production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and industrial enzymes. The ability to predict system-level metabolic responses has positioned constraint-based modeling as an essential component in the metabolic engineer's toolkit, bridging the gap between genomic information and observable physiological behavior.

Theoretical Foundations of Flux Balance Analysis

Mathematical Framework and Key Assumptions

Flux Balance Analysis employs mathematical optimization to predict flux distributions in metabolic networks at steady state. The core mathematical formulation relies on the stoichiometric matrix S, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [28]. The mass balance equation is expressed as:

where v is the vector of metabolic fluxes. This equation embodies the steady-state assumption, indicating that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time as production and consumption rates balance each other [28]. To solve this underdetermined system (typically more reactions than metabolites), FBA incorporates an objective function to be optimized, most commonly biomass maximization, which reflects the biological assumption that microbial metabolism has evolved toward growth optimization [28] [29].

The linear programming problem for FBA can be formally stated as:

where c is a vector indicating the weight of each reaction in the objective function, and lbi and ubi represent lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux v_i [28]. These bounds incorporate known biochemical constraints, such as reaction irreversibility or measured uptake rates for nutrients.

FBA relies on two key simplifying assumptions that enable its application to genome-scale models without requiring extensive parameterization. First, the steady-state assumption presumes that metabolite concentrations remain constant over the timescale of analysis, valid when metabolic fluxes adjust rapidly compared to cell growth [28]. Second, the optimality assumption posits that metabolism operates in a manner that optimes a particular cellular objective, most commonly biomass production [28]. While these assumptions represent simplifications of biological reality, FBA has demonstrated remarkable predictive capability across diverse microorganisms and growth conditions.

Computational Implementation

The implementation of FBA typically begins with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction that defines the biochemical reaction network for a specific organism. For yeast, several such reconstructions exist, including iFF708, iND750, iLL672, iMM904, and Yeast 4.0, each expanding in scope and comprehensiveness [29]. These reconstructions form the foundation for stoichiometric matrices used in FBA simulations.

Practical implementation of FBA involves several key steps. First, the model reconstruction phase involves compiling all known metabolic reactions based on genomic annotation and biochemical literature [28]. Next, the constraint definition phase establishes flux boundaries for exchange reactions based on environmental conditions [31]. Finally, the optimization phase solves the linear programming problem to predict flux distributions [28].

Computational tools such as the COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) toolbox in MATLAB or the COBRApy library in Python provide standardized implementations of FBA and related methods [31]. These tools enable researchers to perform various types of analyses, including gene deletion studies, reaction essentiality assessment, and growth phenotype predictions [28]. The computational efficiency of FBA allows for rapid simulation of genome-scale models, making it practical for high-throughput analysis and metabolic engineering design.

Dynamic Extensions of Flux Balance Analysis

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) Methodology

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis extends the fundamental principles of FBA to incorporate time-dependent changes in the extracellular environment, making it particularly valuable for modeling batch and fed-batch fermentation processes relevant to yeast biotechnology [29] [30]. The dFBA framework couples the constraint-based optimization of FBA with extracellular mass balances, creating a hybrid system that can simulate metabolic adaptation over time [29]. This approach enables researchers to predict how microbial communities, including yeast co-cultures, respond to changing nutrient availability and metabolic byproduct accumulation [30].

The mathematical formulation of dFBA incorporates ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe changes in extracellular metabolite concentrations:

where MEX is the vector of extracellular metabolite concentrations, VEX represents the specific consumption and production rates determined by FBA, and X_V denotes the viable biomass concentration in the culture [29]. This system of equations is solved iteratively, with FBA calculating instantaneous flux distributions at each time step based on current metabolite concentrations, followed by integration of the ODEs to update these concentrations for the next time step [29].

A key advancement in dFBA implementations for yeast research has been the incorporation of dynamic constraints that reflect the changing physiological state of the cells throughout fermentation. These include substrate uptake kinetics that model how nutrient consumption rates depend on extracellular concentrations, maintenance requirements that account for non-growth associated ATP consumption, and biomass composition changes that may occur under different nutrient limitations [29]. For microaerobic yeast fermentations, some dFBA implementations also incorporate dissolved oxygen balances to more accurately capture the metabolic shifts between respiratory and fermentative metabolism [30].

Implementation Protocols for Dynamic FBA in Yeast

Successful implementation of dFBA for yeast metabolic engineering requires careful attention to several procedural aspects. The following protocol outlines the key steps for constructing and validating a dynamic metabolic model for Saccharomyces cerevisiae:

Step 1: Model Initialization and Setup

- Select an appropriate genome-scale metabolic reconstruction for the specific yeast strain under investigation (e.g., iMM904 for S288c-derived strains) [29]

- Define the stoichiometric matrix S and identify exchange reactions for key metabolites (glucose, oxygen, ethanol, glycerol, etc.)

- Establish the objective function, typically biomass maximization during exponential growth phases [29]

Step 2: Parameter Estimation from Experimental Data

- Determine substrate uptake kinetic parameters (Vmax, Ks) from batch pure culture data [30]

- Estimate maintenance coefficients and biomass yields under relevant culture conditions

- For microaerobic fermentations, determine oxygen mass transfer coefficients (kLa) correlated to sparging rates [30]

Step 3: Dynamic Simulation Algorithm

- Implement the iterative solution procedure alternating between FBA optimization and ODE integration [29]

- Set appropriate time steps (typically 0.5-1 hour) to balance computational efficiency with numerical accuracy

- Implement switching logic for objective functions when nutrients become depleted (e.g., from growth maximization to ATP minimization) [29]

Step 4: Model Validation and Refinement

- Compare model predictions to experimental time-course data for biomass, substrates, and metabolic products [29] [30]

- Adjust uptake parameters and constraints to improve agreement with experimental observations

- Validate model extensibility by testing predictions under culture conditions not used for parameter estimation [30]

Table 1: Key Parameters for Dynamic FBA of S. cerevisiae

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Typical Values | Estimation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Uptake | Glucose V_max | 10-20 mmol/gDW/h [29] | Batch culture data fitting |

| Glucose K_s | 0.1-0.5 mM [29] | Chemostat experiments | |

| Kinetic Constants | Oxygen V_max | 2-5 mmol/gDW/h [30] | Respiration assays |

| Xylose V_max (S. stipitis) | 3-6 mmol/gDW/h [30] | Co-culture data | |

| Physical Constants | kLa (oxygen transfer) | 5-100 h⁻¹ [30] | Correlation with sparging rate |

| Biomass yield on glucose | 0.1-0.5 gDW/g [29] | Elemental balancing |

Application Notes: Dynamic Metabolic Modeling in Yeast Co-culture Systems

Case Study: Microaerobic Co-culture of S. cerevisiae and S. stipitis

The application of dFBA to yeast co-culture systems demonstrates the power of this methodology for optimizing bioprocesses with industrial relevance. A representative case study involves the microaerobic co-culture of respiratory-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae and wild-type Scheffersomyces stipitis for efficient conversion of glucose/xylose mixtures to ethanol [30]. This system addresses a significant challenge in lignocellulosic biofuel production – the simultaneous fermentation of hexose and pentose sugars derived from plant biomass hydrolysis.

In this application, dFBA modeling began with the development of individual dynamic models for each yeast species from their respective genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [30]. The S. cerevisiae model was adapted to reflect the metabolic limitations of respiratory-deficient strains, while the S. stipitis model incorporated its unique characteristic of being Crabtree-negative and requiring precise oxygen regulation for efficient ethanol production from xylose [30]. The individual models were then integrated by assuming a community objective of total biomass maximization, with the models connected through shared extracellular metabolites including glucose, xylose, oxygen, and ethanol.

A critical finding from this modeling effort was the identification of substrate competition dynamics that were not apparent from pure culture studies. The dFBA model revealed that S. cerevisiae competed less successfully for glucose in co-culture than predicted from pure culture behavior, necessitating adjustment of its maximum glucose uptake rate in the model to accurately predict co-culture dynamics [30]. This adjustment highlights how dFBA can capture emergent properties in microbial communities that result from species interactions.

Protocol for Yeast Co-culture dFBA

Step 1: Individual Model Development

- Obtain genome-scale reconstructions for each yeast species (e.g., iMM904 for S. cerevisiae, a specialized reconstruction for S. stipitis) [30]

- Estimate species-specific uptake parameters from pure culture experiments under relevant conditions

- For Crabtree-negative yeasts like S. stipitis, incorporate dissolved oxygen balances with mass transfer correlations [30]

Step 2: Model Integration and Community Objective Definition

- Combine individual models through shared extracellular metabolites

- Implement a community objective function, typically maximization of total community biomass [30]

- Define differential equations for all extracellular metabolites tracked in the system

Step 3: Model Calibration with Co-culture Data

- Conduct batch co-culture experiments at different aeration levels and initial sugar ratios [30]

- Adjust uptake parameters (particularly V_max values) to improve prediction of substrate consumption dynamics

- Validate model predictions against experimental data not used in parameter estimation

Step 4: Process Optimization and Strain Design

- Use the calibrated model to predict optimal inoculum ratios and aeration profiles for maximum ethanol productivity [30]

- Identify potential metabolic engineering targets by simulating gene knockouts or overexpression strategies

- Predict how modifications to substrate transport systems (e.g., S. stipitis xylose transporters) would affect co-culture performance [30]

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Yeast Co-culture dFBA Validation

| Parameter | S. cerevisiae | S. stipitis | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Biomass | 0.05-0.2 gDW/L | 0.05-0.2 gDW/L | OD600 with dry weight correlation |

| Sugar Consumption | Glucose only | Glucose and xylose | HPLC analysis |

| Oxygen Sensitivity | Crabtree-positive | Crabtree-negative | Dissolved oxygen probes |

| Ethanol Production Profile | Early phase | Late phase | GC or enzymatic assays |

| Optimal kLa Range | 5-20 h⁻¹ | 5-15 h⁻¹ | Varying sparging rates |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation and Refinement

Metabolite Concentration and Flux Measurement Techniques

Validating constraint-based models requires experimental determination of extracellular metabolite concentrations and intracellular metabolic fluxes. The following protocols describe established methodologies for obtaining these critical data sets in yeast systems:

Protocol 5.1.1: Extracellular Metabolite Time-Course Analysis

- Culture Sampling: Collect culture broth samples at regular intervals (every 1-2 hours for batch fermentations) [30]

- Sample Processing: Immediately separate cells from medium by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 3 minutes, 4°C)

- Metabolite Analysis:

- Biomass Quantification: Measure optical density at 600 nm with correlation to dry cell weight

Protocol 5.1.2: Intracellular Metabolic Flux Analysis Using Isotopic Tracers

- Tracer Experiment Design:

- Metabolite Extraction:

- Rapidly harvest cells using vacuum filtration

- Extract intracellular metabolites using cold methanol/chloroform/water mixture [32]

- Separate aqueous phase containing polar metabolites for analysis

- Isotopic Labeling Measurement:

- Flux Calculation:

- Use computational software (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX) to estimate fluxes by fitting isotopic labeling patterns

- Apply statistical analysis to determine confidence intervals for estimated fluxes

Integration of Experimental Data with Constraint-Based Models

The integration of experimental measurements with constraint-based models significantly enhances their predictive capability and biological relevance. The following protocol outlines procedures for incorporating various data types into metabolic models:

Protocol 5.2.1: Integrating Transcriptomic and Proteomic Data

- Data Collection:

- Obtain transcriptome data via RNA sequencing under specific growth conditions

- Acquire proteome data through mass spectrometry-based quantification

- Data Transformation:

- Convert expression values to reaction constraints using methods like E-Flux or MOMENT

- Define capacity constraints based on enzyme abundance measurements

- Model Contextualization:

- Create condition-specific models by removing reactions associated with non-expressed genes

- Adjust flux bounds proportional to enzyme abundance levels

Protocol 5.2.2: Incorporating Measured Fluxes as Model Constraints

- Flux Validation:

- Compare FBA-predicted fluxes with experimentally determined fluxes from 13C-MFA

- Identify reactions with significant discrepancies between predictions and measurements

- Model Refinement:

- Add thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible cyclic flux loops

- Incorporate regulatory constraints based on known allosteric regulation

- Uncertainty Quantification:

- Perform flux variability analysis to determine ranges of possible fluxes

- Use Monte Carlo sampling to explore the space of feasible flux distributions

Successful implementation of constraint-based modeling and its experimental validation requires specific reagents, computational tools, and datasets. The following table compiles essential resources for researchers working on dynamic metabolic flux analysis in yeast systems.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Yeast Metabolic Flux Studies

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Strains | S. cerevisiae laboratory strains | Model system for eukaryotic metabolism | S288c, CEN.PK, BY4741 |

| Specialized mutants | Study of specific pathway perturbations | Respiratory-deficient mutants [30] | |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-labeled glucose | Metabolic flux analysis | [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose [33] |

| 13C-labeled amino acids | Analysis of nitrogen metabolism | [U-13C]glutamine [32] | |

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated internal standards | Metabolite quantification | d4-succinate, 13C6-citrate |

| Derivatization reagents | GC-MS sample preparation | MSTFA, TBDMS [32] | |

| Culture Media | Defined synthetic media | Controlled nutrient availability | Synthetic Complete (SC) media [32] |

| Complex media | Industrial-relevant conditions | Yeast Extract-Peptone-Dextrose | |

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based FBA/dFBA implementation | git.io/cobratoolbox |

| COBRApy | Python implementation of COBRA methods | opcobrapy.readthedocs.io [31] | |

| Metabolic Models | Yeast genome-scale models | Foundation for constraint-based modeling | iMM904, Yeast 8 [29] |

Visualizing Metabolic Networks and Flux Distributions

Effective visualization of metabolic networks and computational results is essential for interpreting constraint-based modeling outcomes. The following diagrams illustrate key concepts and workflows in dynamic metabolic flux analysis.

Fundamental FBA Workflow

Diagram 1: The FBA workflow illustrates the process from genomic information to flux predictions, highlighting the iterative model refinement based on experimental validation.

Dynamic FBA Integration with Extracellular Environment

Diagram 2: The dFBA procedure shows the iterative coupling between intracellular flux optimization and extracellular mass balances that enables prediction of time-dependent metabolic behaviors.

Constraint-based modeling approaches, particularly Flux Balance Analysis and its dynamic extensions, provide powerful frameworks for investigating and engineering yeast metabolism. The methodologies and protocols outlined in this document offer researchers comprehensive guidance for implementing these computational techniques and validating their predictions through targeted experimentation. As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with high-throughput omics data and machine learning algorithms promises to further enhance our ability to understand and manipulate the dynamic regulation of metabolic fluxes in yeast systems for both fundamental research and industrial applications.