Debottlenecking Constructed Metabolic Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Driven Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on debugging and debottlenecking engineered metabolic pathways.

Debottlenecking Constructed Metabolic Pathways: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Driven Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on debugging and debottlenecking engineered metabolic pathways. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of pathway bottlenecks and their impact on the production of high-value natural products and therapeutics. The piece then explores a suite of established and cutting-edge methodological approaches, including genetic optimization at the DNA, RNA, and protein levels, fermentation strategies, and the application of machine learning for predictive flux balancing. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls, such as the challenges of cytochrome P450-dependent pathways and metabolic burden, offering practical solutions. Finally, the article covers validation and comparative analysis techniques, emphasizing the use of over-representation analysis, topological pathway analysis, and multi-omics integration to confirm pathway efficiency and guide iterative improvement. By synthesizing these four intents, this resource aims to equip scientists with a systematic framework for transforming proof-of-concept pathways into industrially viable production systems.

Understanding Metabolic Bottlenecks: The Core Challenge in Pathway Engineering

Fundamental Concepts: What is a Pathway Bottleneck?

What exactly is a metabolic pathway bottleneck?

A metabolic pathway bottleneck is a specific point within a series of enzymatic reactions that critically limits the overall production rate of a desired end product. It represents the slowest step in the pathway, causing an imbalance where upstream metabolites may accumulate while downstream products are synthesized inefficiently [1]. Bottlenecks arise from limitations in enzyme activity, capacity, or from imbalances in metabolic flux.

What are the different types of bottlenecks I might encounter?

Bottlenecks can be broadly categorized based on their underlying cause. The table below summarizes the primary types.

| Bottleneck Type | Primary Cause | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Level Limitation | Low catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) or insufficient enzyme abundance [2]. | Caused by non-optimal enzyme kinetics, low expression, or instability. |

| Flux Imbalance | Disproportionate reaction rates between consecutive pathway steps [3]. | Leads to accumulation of intermediate metabolites; often revealed by Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). |

| Regulatory Constraint | Allosteric inhibition or transcriptional repression [3]. | Native cellular regulation that cannot be lifted by simply increasing enzyme expression. |

How does epistasis complicate bottleneck resolution?

Epistasis refers to a phenomenon where the effect of a beneficial mutation in one enzyme is dependent on the genetic background of other pathway enzymes [2]. This creates a "rugged evolutionary landscape," meaning that improving one enzyme might render another enzyme rate-limiting or even be detrimental to the overall pathway flux. This complexity often traps directed evolution efforts at local performance maxima, making straightforward optimization ineffective [2].

Identification & Diagnosis: How do I find the bottleneck?

What experimental methods can I use to identify bottlenecks?

A multi-faceted approach is often required to pinpoint the exact nature of a bottleneck. The following table outlines key experimental strategies.

| Method | Application in Bottleneck Identification | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Assays | Measuring in vitro kinetic parameters (KM, kcat) of individual pathway enzymes [2]. | Identifies enzymes with inherently low catalytic efficiency. |

| Metabolomics | Quantifying intracellular levels of pathway intermediates [4]. | Reveals accumulating metabolites, indicating the reaction immediately preceding the accumulation is potentially rate-limiting. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Using genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) to simulate flux distributions [3] [5]. | Predicts systemic flux imbalances and identifies reactions whose overexpression would increase product yield. |

How can I use Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to find flux bottlenecks?

FBA is a constraint-based modeling technique that uses linear programming to predict metabolic flux distributions at steady state. To identify bottlenecks:

- Reconstruct/Select a Model: Use a Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GSMM) for your organism. If modeling secondary metabolism, ensure the pathway is included, which may require manual curation or specialized tools [5].

- Define Constraints: Set constraints such as substrate uptake rates and growth conditions.

- Run Simulation: Typically, the objective function is set to maximize biomass or the production of your target metabolite.

- Analyze Flux Predictions: Reactions carrying very low flux relative to the input and output of the pathway are potential bottlenecks. The model can also be used to predict which gene knockouts or enzyme overexpressions would relieve the bottleneck [3].

What is a standard metabolomics workflow for bottleneck analysis?

Metabolomics can identify bottlenecks by revealing accumulating intermediates [4]. A generalized workflow is as follows:

- Sample Preparation: Quench metabolism rapidly in your production culture and extract metabolites.

- Data Acquisition: Analyze samples using platforms like LC-MS or GC-MS to separate and detect a wide range of metabolites.

- Data Preprocessing: Use software like XCMS or MZmine for peak detection, alignment, and integration [4].

- Compound Identification: Match mass spectrometry data against authentic standards or public databases.

- Data Analysis & Interpretation: Statistically compare the levels of pathway intermediates between high- and low-producing strains. A significant accumulation of a specific intermediate points to the subsequent enzymatic step as a potential bottleneck.

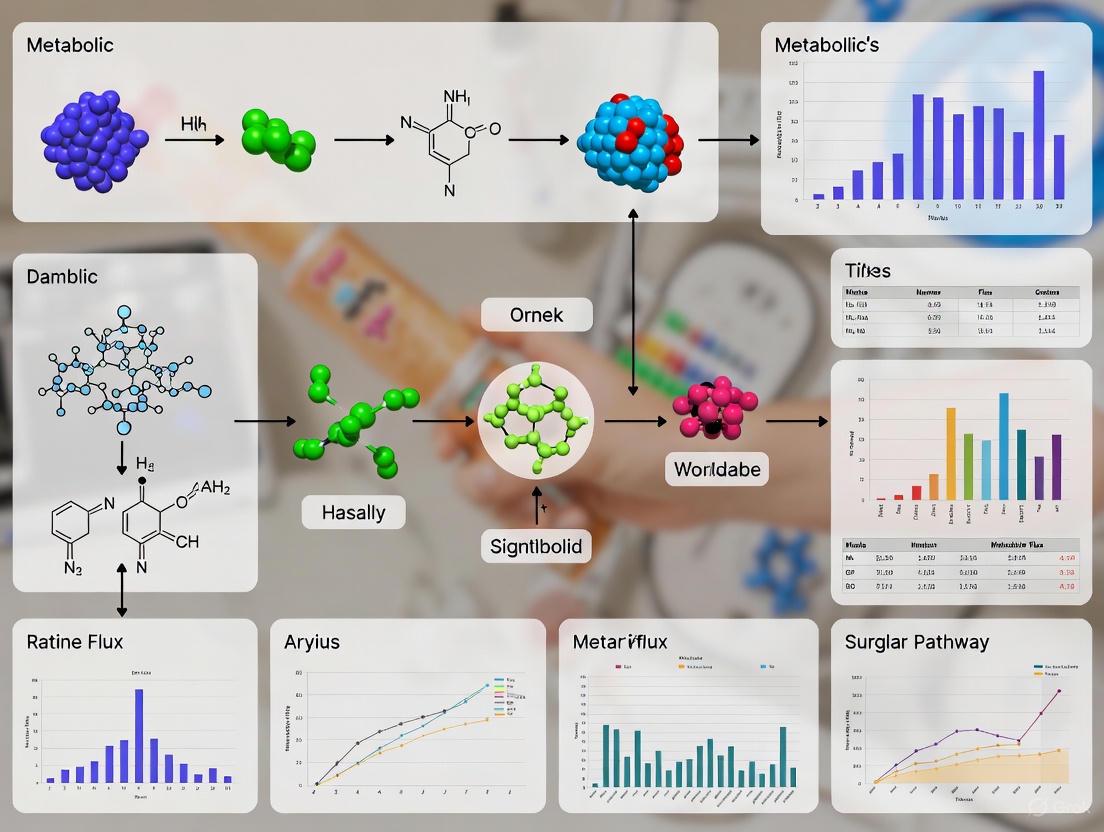

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for diagnosing a pathway bottleneck, integrating both computational and experimental approaches.

Resolution Strategies: How do I fix a bottleneck?

What is the 'bottlenecking and debottlenecking' strategy in directed evolution?

This is an automated, biofoundry-assisted strategy designed to navigate complex epistatic landscapes. It involves two key phases [2]:

- Bottlenecking: The pathway is intentionally constrained by placing a library of one enzyme on a low-copy-number plasmid. This creates a manageable evolutionary landscape where beneficial mutations for that enzyme can be more easily discovered.

- Debottlenecking: Once an improved enzyme variant is found, it becomes the new baseline. The bottleneck is then intentionally shifted to the next enzyme in the pathway by placing its library on a low-copy plasmid, and the selection process is repeated. This enables the parallel and iterative evolution of all pathway enzymes along a predictable trajectory.

What computational tools can predict genetic interventions for debottlenecking?

Several optimization-based algorithms use GSMMs to suggest engineering strategies. These methods typically use Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to identify optimal sets of genetic changes [3].

| Method / Framework | Primary Function | Underlying Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| OptKnock | Identifies gene knockout strategies for overproduction [3]. | Bilevel Optimization (MILP) |

| TIObjFind | Infers context-specific metabolic objective functions to better align FBA with data [6]. | Linear Programming (LP)/Graph Theory |

How can machine learning be applied to pathway debottlenecking?

After initial enzyme improvement, Machine Learning (ML) can further balance pathway flux without the need for further mutagenesis. For instance, the ProEnsemble model was used to optimize the transcription of individual pathway genes by screening a vast combinatorial space of promoter combinations [2]. This approach relaxes epistatic constraints by fine-tuning the expression levels of evolved enzyme variants, ensuring optimal flux through the entire pathway.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated strategy of directed evolution and machine learning for comprehensive pathway debottlenecking.

Protocols & Technical Guides

Protocol: Biofoundry-assisted bottlenecking and debottlenecking

This protocol summarizes the method used to achieve over 3 g/L of naringenin production in E. coli [2].

- Step 1: Pathway Bottlenecking. Clone a random mutagenesis library of the target enzyme (e.g., TAL) into a low-copy-number plasmid (e.g., pBbS8C with SC101 replicon, 5-10 copies). Co-transform with a plasmid harboring the rest of the pathway genes.

- Step 2: High-Throughput Screening. Screen the library for improved producers using a high-throughput assay (e.g., the Al³⁺ assay for naringenin). Validate top hits with HPLC.

- Step 3: Iterative Debottlenecking. Integrate the improved variant into the pathway. Shift the selection pressure to the next enzyme by constructing its library on the low-copy plasmid. Repeat steps 1-2.

- Step 4: Pathway Balancing with ML. Once all enzymes are evolved, use a machine learning model (e.g., ProEnsemble) to optimize the promoter combinations for each gene, further balancing expression and maximizing flux.

Protocol: Gap-filling a draft Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

Gap-filling is essential for creating functional models that can accurately predict bottlenecks using FBA [7].

- Step 1: Generate a Draft Model. Use an automated reconstruction tool like ModelSEED with your annotated genome.

- Step 2: Select a Media Condition. For initial gap-filling, a "Complete" media or a defined minimal media is recommended [7].

- Step 3: Run the Gapfill App. In a platform like KBase, run the gapfilling analysis. The algorithm uses linear programming to find a minimal set of reactions that, when added to the model, allow it to produce biomass on the specified media [7].

- Step 4: Manual Curation. Examine the added reactions (sorted by the "Gapfilling" column in the output). The solution is a prediction and may require manual refinement based on biological knowledge [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents used in the featured experiments for debugging metabolic pathways.

| Item | Function & Application in Debottlenecking |

|---|---|

| Plasmids with varied copy numbers (e.g., pBbS8C (low), pBbE5K (high)) [2] | Used in the bottlenecking strategy to modulate enzyme expression and manage epistasis during directed evolution. |

| Al³⁺ Assay Kit | A high-throughput colorimetric assay used to screen libraries for increased naringenin production [2]. |

| ModelSEED / KBase | A platform and biochemistry database for the automated reconstruction and gap-filling of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models [7]. |

| antiSMASH Software | A genome mining tool for identifying Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs), crucial for incorporating secondary metabolic pathways into models [5]. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS Platforms | Analytical platforms for metabolomics, used to profile intermediate metabolites and identify accumulation points [4]. |

The Impact of Complex Epistasis on Predictable Pathway Evolution

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is complex epistasis and why is it a problem in metabolic engineering? Complex epistasis occurs when the effect of a mutation in one pathway gene depends on the genetic background of other pathway genes. This creates a rugged and unpredictable evolutionary landscape, making it difficult to improve biosynthetic pathways through simple directed evolution. Beneficial mutations in one context can become neutral or even detrimental when combined with other necessary mutations, often trapping evolution at local maxima and preventing straightforward optimization [2].

2. What is the difference between pathway bottlenecking and debottlenecking?

- Bottlenecking is the intentional creation of a rate-limiting step in a pathway, often by using a low-copy plasmid for a specific gene. This simplifies the evolutionary landscape by providing a clear, manageable selection pressure [2].

- Debottlenecking is the subsequent process of evolving the constrained gene to overcome the limitation. Once improved, the focus can shift to the next emerging bottleneck in the pathway. This sequential approach enables parallel evolution of all pathway enzymes along a more predictable trajectory [2].

3. My pathway production seems stuck. How can I tell if epistasis is the cause? A strong indicator of complex epistasis is when a beneficial enzyme variant, identified through screening in a specific genetic context (e.g., on a low-copy plasmid), fails to improve performance when placed into the final, high-expression production chassis. For example, a TAL mutant (TAL-26E7) showed a 3.86-fold increase in enzyme activity on a low-copy plasmid but resulted in lower overall naringenin production when moved to a high-copy plasmid, directly demonstrating the context-dependence of mutational effects [2].

4. What tools can help balance a pathway after evolving the enzymes? After evolving enzyme sequences, machine learning (ML) models can be employed to fine-tune expression levels and balance metabolic flux. For instance, the study used a model called ProEnsemble to optimize the combination of promoters for individual genes, thereby relaxing epistatic constraints and further enhancing pathway performance [2].

5. Besides directed evolution, what other techniques can provide insight into pathway dynamics? Metabolic tracing is a powerful complementary technique. It uses isotopically labeled nutrients (e.g., 13C-glucose) to track the flow of molecules through metabolic pathways. This provides a dynamic picture of pathway activity, helping to identify which nutrients are being used, how fast they are consumed, and where potential bottlenecks or alternative metabolic routes exist [8].

Experimental Protocol: A Biofoundry-Assisted Strategy for Pathway Evolution

This protocol outlines the bottlenecking/debottlenecking strategy used to evolve a naringenin biosynthetic pathway in E. coli [2].

1. Pathway Assembly and Initial Setup

- Assemble your heterologous pathway genes (e.g., TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI for naringenin) in a single operon or on separate plasmids with compatible origins of replication.

- Transform the constructed plasmid(s) into your production host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Quantify the baseline production of the target metabolite (e.g., via HPLC) to establish a starting point.

2. Identification and Creation of a Strategic Bottleneck

- Clone individual pathway genes onto plasmids with varying copy numbers (e.g., SC101, p15a, ColE1, RSF replicons).

- Co-transform these plasmids with the rest of the pathway on a separate backbone.

- Measure production to identify which gene, when placed on a low-copy plasmid, creates a manageable bottleneck without halting production entirely. This gene becomes the first target for evolution.

3. Directed Evolution of the Bottlenecked Enzyme

- Generate a random mutagenesis library of the bottlenecked gene.

- Clone the mutant library into the low-copy plasmid identified in the previous step.

- Co-transform the library with the plasmid containing the rest of the pathway.

- Use a high-throughput assay (e.g., the Al3+ assay for naringenin) to screen for variants that show improved production.

- Validate top hits from the primary screen with a more precise analytical method (e.g., HPLC).

- Sequence the validated mutants to identify beneficial mutations.

4. Iterative Debottlenecking and Characterization

- Introduce the evolved, improved gene variant back into higher-copy plasmids or different genetic contexts to test for epistatic effects.

- Characterize the kinetic parameters (KM, kcat) of the purified wild-type and evolved enzymes to quantify the improvement at the protein level [2].

- Repeat the bottlenecking process for the next gene that becomes the limiting factor in the pathway.

5. Final Pathway Balancing with Machine Learning

- Once all enzymes have been evolved, use a machine learning model to optimize their expression levels.

- Input data such as promoter strengths, enzyme sequences, and production titers into the model (e.g., ProEnsemble).

- Let the model predict the optimal promoter combinations for each gene to maximize flux and minimize residual epistasis.

- Construct and test the final, balanced pathway in your production chassis.

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of Evolved Naringenin Pathway Enzymes [2]

| Enzyme | Variant | Mutation | KM (mM) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat / KM (mM⁻¹s⁻¹) | Fold Improvement (kcat/KM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAL | Wild-type | - | 0.38 | 114.00 | 300.00 | - |

| TAL | 26E7 | H174Q | 2.09 | 2416.00 | 1158.20 | 3.86 |

| 4CL | Wild-type | - | 0.65 | 3.01 x 10⁶ | 4.63 x 10³ | - |

| 4CL | 11C1 | L66P | 0.06 | 5.75 x 10⁶ | 9.58 x 10³ | 2.07 |

Table 2: Naringenin Production Under Different Genetic Contexts [2]

| Genetic Context | TAL Variant | Naringenin Titer (mg/L) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCDF-T4SI (Reference) | Wild-type | 129.67 | All genes on a single medium-copy plasmid. |

| pBbE5K (High-copy) + pCDF-4SI | Wild-type | 357.66 | TAL on a high-copy plasmid improves titer. |

| pBbS8C (Low-copy) + pCDF-4SI | Wild-type (TAL) | (Baseline) | Used as a baseline for screening TAL mutants. |

| pBbS8C (Low-copy) + pCDF-4SI | Evolved (26E7) | >Baseline | Confirmed improved production in low-copy context. |

| pBbE5K (High-copy) + pCDF-4SI | Evolved (26E7) | 86.00 | Demonstrates epistasis: beneficial mutation in low-copy context is detrimental in high-copy context. |

| Final Optimized Chassis | Evolved & Balanced | 3,650.00 | After sequential evolution and ML-based balancing. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions [2]

| Item | Function / Application in Pathway Debugging |

|---|---|

| Plasmids with different replicons (e.g., SC101, p15a, ColE1) | Essential for the bottlenecking strategy. Allows for tuning of gene copy number to create manageable evolutionary landscapes. |

| Random Mutagenesis Library Kits | Used to generate genetic diversity in individual pathway genes for directed evolution. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay (e.g., Al³⁺ assay for flavonoids) | Enables rapid screening of thousands of enzyme variants for improved product formation. |

| HPLC / Mass Spectrometry | Provides accurate quantification of metabolite titers for validation of top-performing variants and system characterization. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., ProEnsemble) | Used post-evolution to predict optimal gene expression levels (e.g., promoter combinations) for final pathway balancing. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | For metabolic tracing experiments to map flux through pathways and identify active routes or bottlenecks [8]. |

Pathway Bottlenecking and Debottlenecking Workflow

The Epistasis Dilemma in Pathway Engineering

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Low Enzyme Activity

Q: My metabolic pathway is producing far less product than predicted. How can I determine if low enzyme activity is the bottleneck?

A: Low catalytic efficiency of one or more pathway enzymes is a primary bottleneck. Diagnosis involves evaluating enzyme kinetics and using biosensors to identify rate-limiting steps.

Diagnosis:

- Measure Enzyme Kinetics: For suspected enzymes, assay their activity in vitro. Determine key parameters like ( KM ) (affinity for substrate) and ( k{cat} ) (catalytic turnover). A high ( KM ) or low ( k{cat }) compared to other pathway enzymes indicates a likely bottleneck [2].

- Use a Biosensor for High-Throughput Screening: Employ a product-specific sensor (e.g., the Al³⁺ assay for naringenin) to rapidly screen thousands of enzyme variants. Co-express a library of mutant enzymes and select clones that produce a stronger sensor signal, indicating higher product titer [2].

Solution: Directed Evolution

- Create a Mutant Library: Generate a diverse library of the target enzyme gene via error-prone PCR or other mutagenesis techniques.

- Screen for Improved Variants: Use the biosensor or HPLC to identify top-performing variants from the library. For example, a TAL (tyrosine ammonia-lyase) mutant, TAL-26E7, was isolated this way and showed a 3.86-fold increase in ( k{cat}/KM ) [2].

- Validate in Pathway Context: Introduce the evolved enzyme back into the full pathway to confirm it improves final product yield.

Table: Example of Enzyme Kinetic Improvement via Directed Evolution

| Enzyme | Mutation | ( K_M ) (mM) | ( k_{cat} ) (s⁻¹) | ( k{cat}/KM ) (mM⁻¹s⁻¹) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAL (Wild-type) | - | 0.38 | 114.00 | 300.00 | 1.00x |

| TAL-26E7 (Evolved) | H174Q | 2.09 | 2416.00 | 1158.20 | 3.86x |

| 4CL (Wild-type) | - | 0.65 | 3.01 x 10⁶ | 4.63 x 10³ | 1.00x |

| 4CL-11C1 (Evolved) | L66P | 0.06 | 5.75 x 10⁶ | 9.58 x 10³ | 2.07x |

Experimental Protocol: In Vitro Enzyme Kinetics Assay

- Objective: Determine the ( KM ) and ( k{cat} ) of an enzyme.

- Materials: Purified enzyme, substrate, reaction buffer, spectrophotometer or HPLC.

- Method:

- Prepare a series of reactions with a fixed amount of enzyme and varying substrate concentrations ([S]).

- Measure the initial reaction rate (v₀) for each [S] by tracking product formation over time.

- Plot v₀ against [S]. The data should fit the Michaelis-Menten curve.

- Derive ( KM ) (the [S] at which v₀ is half of Vₘₐₓ) and ( V{max} ) (the maximum reaction rate) from the plot.

- Calculate ( k{cat} ) using the formula: ( k{cat} = V{max} / [E]t ), where [E]_t is the total enzyme concentration.

Directed Evolution Workflow for Low Enzyme Activity

Guide 2: Addressing Enzyme and Genetic Instability

Q: My engineered strain loses productivity over successive generations, or I observe failed reactions. What could be causing this instability?

A: Instability can arise from protein misfolding/degradation or genetic rearrangements in the engineered pathway, often triggered by metabolic stress.

Diagnosis:

- Check Plasmid and Gene Integrity: Use PCR and sequencing to verify that pathway genes have not acquired mutations or deletions over time.

- Test for Gross Chromosomal Rearrangements (GCRs): In yeast, genetic assays can detect GCRs like translocations and deletions, which are associated with genome instability and can disrupt engineered pathways [9].

- Monitor Protein Levels: Use Western blotting to see if enzyme proteins are being degraded or are not expressed.

Solution:

- Reduce Metabolic Burden: Use low-copy-number plasmids instead of high-copy plasmids to lessen the cellular burden of heterologous gene expression, which can improve stability [2].

- Utilize Genome Integration: Stably integrate pathway genes into the host genome to avoid plasmid loss.

- Employ Advanced Genetic Tools: Use CRISPR-based tools to identify mutations that confer instability and design more robust constructs [10].

Table: Common Sources and Solutions for Instability

| Source of Instability | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Misfolding | SDS-PAGE, Western Blot | Use codon optimization; employ chaperone proteins; lower expression strength. |

| Genetic Mutation/Deletion | PCR, DNA Sequencing | Use stable, low-copy plasmids; integrate genes into the host chromosome [2]. |

| Gross Chromosomal Rearrangement (GCR) | Specialized genetic assays (e.g., in S. cerevisiae) [9] | Engineer host with defects in GCR-formation mechanisms (e.g., DNA repair pathways) [9]. |

| Metabolic Burden | Growth rate analysis, Omics | Balance enzyme expression; use inducible promoters; down-compete non-essential pathways. |

Guide 3: Managing Metabolic Burden and Flux Imbalance

Q: My host strain grows poorly after introducing the pathway, and metabolic by-products accumulate. How can I rebalance the metabolism?

A: This is a classic symptom of metabolic burden, where resource competition and imbalanced flux choke the pathway. Systematic debottlenecking is required.

Diagnosis:

- Conduct Metabolomics: Use untargeted metabolomics to profile intracellular metabolites. Identify which pathways are over- or under-active compared to a control strain [11].

- Perform Metabolic Pathway Enrichment Analysis (MPEA): Statistically analyze metabolomics data to find which entire metabolic pathways (e.g., Pentose Phosphate Pathway, CoA biosynthesis) are significantly perturbed [11].

- Use Computational Models: Employ Enzyme-constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (ecGEMs). Tools like

ecFactorycan predict protein limitations and identify which enzyme reactions are flux-limiting, distinguishing between stoichiometric and enzyme-driven constraints [12].

Solution:

- Fine-Tune Expression Levels: Use promoter engineering or RBS optimization to balance the expression of all pathway genes, preventing the over-accumulation of intermediates [2].

- Augment Cofactor/Precursor Supply: Overexpress native genes in bottlenecked precursor pathways identified by MPEA or ecGEMs (e.g., genes in PPP for NADPH supply) [11] [12].

- Apply Machine Learning: Tools like ProEnsemble can optimize promoter combinations for pathway genes to minimize burden and maximize product formation [2].

Experimental Protocol: Metabolomics for Pathway Debottlenecking

- Objective: Identify dysregulated metabolic pathways in an engineered production host.

- Materials: Quenched cell pellets from production and control strains, LC-HRMS system.

- Method:

- Extraction: Metabolites are extracted from cell pellets using a solvent like cold methanol/acetonitrile/water.

- Data Acquisition: Analyze extracts using Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) in an untargeted mode.

- Data Processing: Use software to pick peaks, align samples, and putatively identify metabolites.

- Pathway Analysis: Input the list of significantly changed metabolites into an enrichment tool (e.g., MetaboAnalyst). The output will show metabolic pathways that are statistically over-represented, highlighting potential bottlenecks [11].

Metabolic Burden Diagnosis and Resolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is epistasis in metabolic pathways, and why does it matter for debottlenecking? A: Epistasis occurs when the effect of a mutation in one gene depends on the presence of mutations in other genes. In pathways, this creates a "rugged evolutionary landscape," meaning that improving one enzyme can make another enzyme the new bottleneck. This complicates sequential engineering and highlights the need for strategies that enable parallel evolution of multiple pathway enzymes [2].

Q2: Are there computational tools that can predict bottlenecks before I start lab work?

A: Yes. Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) like ecYeastGEM are particularly powerful. The ecFactory pipeline uses such models to predict optimal gene knockout and overexpression targets for producing specific chemicals, accounting for the physical limit of how much protein a cell can produce [12]. These predictions can prioritize your experimental efforts.

Q3: Can bottlenecks be beneficial? A: In a specific context, yes. Recent research shows that intentionally creating metabolic bottlenecks (e.g., through mutations in essential metabolic genes) can reduce bacterial growth rates and decrease susceptibility to antibiotics. However, for industrial bioproduction, bottlenecks are almost always undesirable as they limit yield and productivity [10].

Q4: How do I choose the right pathway modeling format for sharing my results? A: For creating reusable and computationally analyzable pathway models, follow FAIR principles. Use standardized formats like SBGN (Systems Biology Graphical Notation) for diagrams and SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) or BioPAX for data exchange. Always annotate model components with resolvable database identifiers (e.g., UniProt for proteins, ChEBI for chemicals) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for Pathway Debottlenecking

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Al³⁺ Assay | A colorimetric biosensor for flavonoids like naringenin. | High-throughput screening of mutant enzyme libraries for improved activity [2]. |

| Enzyme-constrained GEM (ecGEM) | A genome-scale model that incorporates enzyme kinetics to predict protein-limited metabolic fluxes. | In silico prediction of metabolic engineering targets and identification of protein-constrained products [12]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis Library | A tool for generating comprehensive sets of mutants, often in essential genes. | Systematically identifying metabolic mutations that affect non-metabolic phenotypes, like antibiotic susceptibility [10]. |

| Metabolic Pathway Enrichment Analysis (MPEA) Software | Statistical tools to find biologically relevant pathways from omics data. | Interpreting untargeted metabolomics data to find significantly modulated pathways in a production strain [11]. |

| Low-/Medium-Copy Number Plasmids | Vectors with controlled replication to reduce metabolic burden. | Maintaining stable expression of heterologous pathways without severely impacting host growth [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is metabolic flux and why is it a critical parameter in metabolic engineering? Answer: Metabolic flux is defined as the rate of turnover of molecules through a metabolic pathway. It is the definitive parameter for investigating cell metabolism because the activation and inactivation of metabolic pathways can be directly evaluated by determining metabolic flux levels [14]. It represents the ultimate representation of the cellular phenotype and provides a quantitative readout of cellular function, helping to understand cell growth, maintenance, and responses to environmental changes [15] [14]. In metabolic engineering, controlling flux is vital for regulating a pathway's activity under different conditions to achieve desired outcomes, such as increased production of a target compound [15].

2. What does "debottlenecking" mean in the context of engineered metabolic pathways? Answer: Debottlenecking refers to the process of identifying and overcoming limiting steps, or "bottlenecks," within a constructed metabolic pathway. These bottlenecks are often enzymatic steps that suffer from low activity, instability, or poor expression, which seriously impair the development of a high-performing bioprocess [16]. For example, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases are a versatile enzyme superfamily used in biosynthesis but often require debottlenecking through protein engineering to achieve sufficient activity and stability for commercial production [16].

3. Why might a pathway enzyme with high in vitro activity still create a flux bottleneck in a living cell? Answer: The control of flux is a systemic property. A result that may seem counterintuitive is that regulated steps often have small flux control coefficients [15]. This is because these steps are part of a control system that stabilizes fluxes; a perturbation in the activity of a regulated step will trigger the control system to resist the change. Therefore, a step with high in vitro activity might have less influence over the steady-state flux in the intact system than a less obvious step elsewhere in the network [15].

4. What are some common methods for measuring or estimating metabolic fluxes? Answer: Metabolic fluxes cannot be measured directly but must be inferred from other observables [14]. Common methodologies include:

- Material Balance Analysis: Determining specific consumption/production rates from time-course analysis of medium components and cell numbers under a metabolic steady state [14].

- Stable Isotope Labeling: Using technologies like NMR or GC-MS to monitor stable isotope labeling profiles, which provide highly informative flux indicators [15] [14].

- Extracellular Flux Analysis: Using instruments like a flux analyzer to measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) as indirect estimates of mitochondrial and glycolytic flux [17] [14].

- Luminescent ATP Assay: A high-throughput method that directly measures ATP levels after systematic inhibition of specific pathways to calculate a cell's dependency on different energy metabolic pathways [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Total Titer of Target Natural Product

Potential Cause: A metabolic bottleneck at a cytochrome P450-dependent step. These enzymes are versatile but can suffer from low activity and instability [16].

Debugging Steps:

- Confirm Enzyme Function: Express and purify the P450 enzyme. Test its activity and stability in vitro under simulated process conditions.

- Profile Intermediate Metabolites: Use LC-MS or GC-MS to profile intermediate metabolites in the pathway. An accumulation of the substrate for the P450 enzyme and a low level of its product strongly indicates a bottleneck at this step.

- Check Cofactor Availability: Ensure that cofactors and redox partners are present at sufficient levels to support P450 activity.

- Implement Protein Engineering: If a bottleneck is confirmed, deploy protein engineering strategies (e.g., directed evolution, rational design) to improve the enzyme's activity, stability, and expression in the host organism [16].

Problem 2: Inability to Resolve Intracellular Fluxes

Potential Cause: Relying solely on extracellular consumption rates for a complex network, which is insufficient to resolve intracellular flux distributions [14].

Debugging Steps:

- Design a Tracer Experiment: Use a stable isotope-labeled carbon source (e.g., U-¹³C glucose) and allow the system to reach an isotopic steady state.

- Measure Labeling Patterns: Use NMR or GC-MS to measure the labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites.

- Perform Computational Flux Analysis: Use computational software to perform ¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis (¹³C-MFA). The software will fit a flux map to your measured labeling data, providing estimates of the intracellular fluxome [14].

Problem 3: Characterizing Energy Metabolism Dependencies

Potential Cause: Existing methods (e.g., extracellular flux analyzers) are expensive, low-throughput, or provide indirect measurements [17].

Debugging Steps: Follow this high-throughput protocol to directly measure ATP production dependency on different pathways [17]:

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Energy Metabolic Pathway Dependency

- Key Principle: Direct measurement of ATP levels after systematic inhibition of specific metabolic pathways to calculate their relative contribution to cellular ATP production.

| Step | Procedure | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Seeding | Seed cells in a 96-well plate. | Use a white plate for ATP assays and a clear plate for viability assays. Ensure cells are in exponential growth phase [17]. |

| 2. Perturbation | Treat cells with the compound of interest (e.g., Metformin). | Incubate for a desired period to induce a new metabolic state [17]. |

| 3. Metabolic Inhibition | Systematically inhibit specific pathways. | Add inhibitors: - 2-deoxy-D-glucose (Glycolysis) - Oligomycin A (Oxidative Phosphorylation) - Other pathway-specific inhibitors [17]. |

| 4. Assay Execution | Perform cell viability and ATP assays. | Viability Assay: Use XTT-based kit on clear plate. ATP Assay: Use luminescent ATP detection kit on white plate [17]. |

| 5. Data Analysis | Normalize ATP levels and calculate dependencies. | Normalize luminescence (ATP) by absorbance (viability). Calculate % dependency for each pathway based on ATP drop upon inhibition [17]. |

Problem 4: Visualizing Dynamic Changes in Metabolite Levels

Potential Cause: Static pathway maps make it difficult to interpret time-course metabolomic data and identify correlated changes [18].

Debugging Steps:

- Generate Time-Course Data: Collect metabolomic samples at multiple time points during your experiment.

- Utilize Dynamic Visualization Software: Use tools like GEM-Vis or SBMLsimulator [18].

- Create an Animated Flux Map: Input your quantitative time-course data and a corresponding metabolic network map (SBML format). The software will create an animation where metabolite nodes change their fill level, color, or size over time, allowing you to visually track metabolic shifts and generate new hypotheses [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the experiments and methodologies cited in this guide.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Flux Analysis and Pathway Debugging

| Research Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 2-deoxy-D-glucose | A glycolytic inhibitor. Used in pathway dependency assays to block glucose utilization and assess the contribution of glycolysis to energy production [17]. |

| Oligomycin A | An ATP synthase inhibitor. Used to block mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, allowing measurement of the mitochondrial dependency of ATP production [17]. |

| Uniformly ¹³C-Labeled Glucose | A stable isotope tracer. Crucial for ¹³C Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to experimentally determine intracellular metabolic fluxes by tracking the incorporation of the label through the metabolic network [15] [14]. |

| Luminescent ATP Detection Assay Kit | Provides reagents for a high-throughput, sensitive bioluminescent assay to directly quantify ATP concentrations in cell populations, essential for energy metabolism profiling [17]. |

| Metformin | A metabolic perturbant. Often used in experimental models to induce a shift in cellular energy metabolism, mimicking a stressed or diseased state for study [17]. |

| Cytochrome P450 Enzymes | A superfamily of heme-containing enzymes. Common targets for debottlenecking in the biosynthesis of natural products due to their catalytic versatility but frequent issues with low activity and instability [16]. |

Key Conceptual Diagrams

Metabolic Flux and Debottlenecking Concept

Energy Metabolism Profiling Workflow

Flux Control in a Linear Pathway

A Toolkit for Pathway Debugging: From Genetic Tuning to AI and Fermentation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary genetic levels for fine-tuning in metabolic engineering? Fine-tuning in metabolic engineering is performed at three primary levels:

- DNA (Transcriptional) Level: Controls whether and how much mRNA is produced from a gene. This includes the engineering of promoters, transcription factors, and CRISPR-based systems [19] [20].

- RNA (Post-Transcriptional/Translational) Level: Regulates how efficiently mRNA is translated into protein, often using synthetic sRNAs or riboswitches [19].

- Protein (Post-Translational) Level: Manages the activity, stability, and degradation of existing enzyme proteins through degrons or scaffold systems [19] [20].

FAQ 2: My pathway has a bottleneck, but I don't know which enzyme is limiting. How can I identify it? A bottlenecking and debottlenecking strategy can systematically identify and resolve flux limitations.

- Method: Place the gene for a suspected bottleneck enzyme on a low-copy plasmid while keeping other pathway genes on a high-copy plasmid. The low gene dosage creates a controlled bottleneck. A mutagenesis library of this gene is then screened for variants that improve final product titers when expressed from the low-copy plasmid, indicating you've found a beneficial mutation for a limiting step [2].

- Example: In a naringenin pathway, placing the TAL enzyme on a low-copy plasmid and evolving it under this constraint yielded a mutant (TAL-26E7) with a 3.86-fold higher catalytic efficiency, which subsequently improved pathway flux [2].

FAQ 3: How can I balance the expression of multiple genes in a pathway without testing every possible combination? Instead of a one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach, use Design of Experiments (DoE) or Machine Learning (ML)-guided optimization.

- DoE Approach: This statistical method tests a fraction of all possible combinations (a fractional factorial design) to build a model that predicts optimal expression levels. For example, testing just 3 promoter strengths for each of 4 genes requires 81 (3^4) combinations. A definitive screening design can identify the most impactful factors with far fewer experiments [21].

- ML Approach: After generating an initial dataset of promoter combinations and their resulting titers, a machine learning model (like ProEnsemble) can be trained to predict high-performing configurations, dramatically reducing the experimental workload [2].

FAQ 4: What are the advantages of dynamic regulation over static, constitutive expression? Static, strong expression can lead to toxic intermediate accumulation or resource competition that hinders host cell growth. Dynamic regulation uses sensors to trigger pathway expression only when needed.

- Mechanism: A biosensor is engineered to detect a key pathway metabolite or a cellular state. This sensor controls the expression of the pathway genes.

- Benefit: It automatically decouples cell growth from product synthesis, allowing high biomass accumulation before production begins, often leading to higher final titers and robustness [19].

FAQ 5: What computational tools can I use to model and predict the behavior of my engineered pathway? Leverage existing databases and modeling software.

- Network Reconstruction & Analysis: Tools like Model SEED can help draft genome-scale metabolic models. The BiGG database provides curated, mass-and-charge balanced metabolic networks. Visualize pathways using KEGG PATHWAY or MetaCyc [22].

- Standardized Formats: Use the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) to represent your model, ensuring compatibility with over 200 software tools for simulation and analysis [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Final Product Titer Despite High Pathway Gene Expression

Possible Cause 1: Metabolic Imbalance The expression levels of your pathway enzymes are not balanced, causing a bottleneck at a slow step and accumulation of a possibly toxic intermediate.

- Diagnosis:

- Measure intermediate metabolites via HPLC or LC-MS to identify the point of accumulation.

- Check for impaired host cell growth, which can indicate toxicity.

- Solution:

- Fine-tune transcription: Use a suite of promoters with varying strengths or inducible systems to adjust the expression of the bottlenecked gene [19] [20].

- Implement dynamic control: Replace constitutive promoters with metabolite-responsive promoters that upregulate downstream genes only when the intermediate is present [19].

Possible Cause 2: Resource Competition The heterologous pathway is drawing too many essential precursors (e.g., acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA) or cofactors (e.g., NADPH) from host metabolism, crippling growth.

- Diagnosis: Monitor growth rates. If the host grows poorly immediately after pathway induction, resource competition is likely.

- Solution:

Problem: Engineered Strain Performs Well in Lab Media but Poorly in a Bioreactor

Possible Cause: Suboptimal Bioprocess Conditions The environmental factors (pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrient feed) are not optimized for your specific strain and pathway.

- Diagnosis: Use Design of Experiments (DoE) to systematically evaluate the impact of multiple process variables.

- Solution:

- Screening Design: First, use a Plackett-Burman design to identify the most critical factors from a large list (e.g., temperature, pH, inducer concentration, carbon source level) [21].

- Optimization Design: Then, apply a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) like Central Composite Design (CCD) to find the optimal levels for the 2-4 most critical factors identified in the screening [21].

Problem: Protein Aggregation or Misfolding of a Key Pathway Enzyme

Possible Cause: Incompatibility between the heterologous protein and the host's chaperone system.

- Diagnosis: Analyze protein solubility via fractionation and SDS-PAGE or use a fluorescent tag to visualize inclusion bodies.

- Solution:

- Fine-tune at the protein level: Fuse an engineered degron (degradation tag) to the problematic enzyme. This allows you to control its cellular concentration and reduce the burden of aggregated proteins [20].

- Use directed evolution: Create a mutagenesis library of the enzyme gene and screen for variants that maintain activity but are more soluble in your host [2].

Table 1: Fine-Tuning Toolsets at Different Regulatory Levels

| Regulatory Level | Tool/Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Example Application & Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA (Transcriptional) | Promoter Engineering | Varies the strength of RNA polymerase binding and initiation [19]. | Naringenin in E. coli: 2.1-fold titer increase (→191 mg/L) [19]. |

| CRISPRi/a | Uses a deactivated Cas9 to block (interference) or recruit activators (activation) to a gene promoter [19]. | β-Amyrin in S. cerevisiae: 44.3% titer increase (→156.7 mg/L) [19]. | |

| Artificial Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Engineered proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to activate or repress transcription [19]. | Fatty Acids in E. coli: 15.7-fold titer increase (→3.86 g/L) [19]. | |

| RNA (Post-Transcriptional) | Synthetic sRNAs | Engineered small RNAs that bind target mRNAs, blocking their translation [19]. | L-Threonine in E. coli: Titer increased to 22.9 g/L [19]. |

| Riboswitches | Ligand-binding mRNA domains that undergo conformational change to regulate translation [20]. | Used for dynamic control in various biosynthetic pathways [20]. | |

| Protein (Post-Translational) | Degrons | Tags added to a protein to target it for controlled degradation by cellular proteases [20]. | Improved monoterpene production in yeast by regulating enzyme abundance [20]. |

| Scaffold Engineering | Co-localizes sequential enzymes in a pathway via protein-protein interaction domains to substrate channel [19]. | Increased efficiency in mevalonate pathway [19]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Results from Pathway Fine-Tuning Case Studies

| Target Compound | Host Organism | Optimization Strategy | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | E. coli | Bottlenecking/Debottlenecking + Machine Learning (ProEnsemble) promoter balancing [2]. | 3.65 g/L final titer. |

| Mevalonate | Pseudomonas putida | CRISPRa-mediated transcriptional activation of pathway genes [19]. | 40-fold increase in titer (→402 mg/L). |

| TAL Enzyme (in Naringenin pathway) | E. coli | Directed evolution under bottlenecking conditions [2]. | 3.86-fold increase in kcat/KM for the evolved TAL-26E7 mutant. |

| L-Proline | E. coli | Fine-tuning central metabolism using synthetic sRNAs [19]. | 54.1 g/L final titer. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning Using Promoter Libraries

Objective: To balance a 3-gene pathway (Gene A, Gene B, Gene C) by testing different promoter strengths.

Materials:

- A set of 3 characterized promoters of low, medium, and high strength.

- Plasmid backbone(s) with compatible origins of replication and selection markers.

- Host strain (E. coli or S. cerevisiae).

Procedure:

- Construct Variants: Assemble the pathway by cloning each gene (A, B, C) under the control of the low, medium, or high-strength promoter. This creates a library of 27 (3^3) possible genetic constructs.

- Transform and Culture: Transform the library variants into your host strain and culture them in a deep-well plate with the appropriate production medium.

- Screen for Production: After a suitable incubation period, measure the final product titer for each variant using HPLC or a relevant assay.

- Analyze and Iterate: Identify the top-performing promoter combinations. Use this data to refine the library or to train a machine learning model for further prediction [2].

Protocol 2: Implementing a CRISPRi System for Gene Downregulation

Objective: To knock down the expression of a competitive native gene to redirect flux toward your desired pathway.

Materials:

- Plasmid expressing a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9).

- Plasmid expressing a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting your gene of interest.

- Control: A non-targeting sgRNA.

Procedure:

- Design sgRNAs: Design 2-3 sgRNAs targeting the promoter or coding region of the competitive gene.

- Co-transform: Co-transform the dCas9 and sgRNA plasmids into your production strain.

- Evaluate Knockdown: Measure the mRNA level of the target gene (via qPCR) and/or the product titer of your desired pathway. Compare to the control strain with the non-targeting sgRNA [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Library | A collection of DNA sequences with varying transcriptional strengths to systematically adjust mRNA levels of a gene [19]. | Balancing expression of multiple genes in a heterologous pathway. |

| CRISPRi/a System | A programmable system (dCas9 + sgRNA) for targeted gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) without altering the DNA sequence [19]. | Dynamically repressing a competing pathway or activating a limiting pathway gene. |

| Synthetic sRNA | An engineered non-coding RNA that base-pairs with target mRNA to inhibit its translation [19]. | Fine-tuning gene expression at the translational level without modifying the gene itself. |

| Degron Tag | A peptide sequence fused to a protein that targets it for degradation by the host's proteolytic machinery [20]. | Controlling the half-life and cellular concentration of a key enzyme. |

| DNA Aptamer | A single-stranded DNA molecule that binds a specific small molecule ligand, often used in biosensor construction [19]. | Forming the sensing component of a dynamic regulation circuit. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pathway Bottlenecking and Debottlenecking Workflow

Diagram 2: Multi-Level Gene Expression Fine-Tuning

The Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking Strategy for Parallel Enzyme Evolution

This technical support guide details the Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking strategy, a method designed to overcome a major hurdle in metabolic engineering: the unpredictable, complex epistatic interactions that hinder the directed evolution of multiple pathway enzymes simultaneously. This guide provides researchers with the protocols and troubleshooting knowledge necessary to implement this approach for debugging and optimizing constructed metabolic pathways, enabling the efficient development of microbial cell factories for chemical and drug production.

Core Concept and Experimental Protocol

The Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking strategy is a biofoundry-assisted method that enables the parallel evolution of all enzymes in a metabolic pathway along a predictable trajectory. The process is designed to circumvent complex epistasis, where the effect of a mutation in one enzyme depends on the sequence of other pathway enzymes, which traditionally makes pathway optimization challenging [23].

The complete workflow, from initial pathway construction to a high-titer production chassis, is summarized in the diagram below.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

Initial Pathway Construction: Clone the genes for the target metabolic pathway (e.g., the naringenin biosynthetic pathway) into your production host (e.g., Escherichia coli). Confirm baseline production of the target molecule [23] [24].

Pathway Bottlenecking (Identification Phase):

- Objective: To sequentially force each enzyme in the pathway to become the rate-limiting step, thereby revealing its evolutionary potential and constraints.

- Method: Systematically weaken each enzyme in the pathway one at a time. This is achieved by replacing its native promoter with a progressively weaker constitutive promoter or by employing CRISPRi to titrate its expression down.

- Measurement: For each constrained enzyme, measure the resulting titer of the final product. A significant drop in titer indicates that the enzyme is a potential bottleneck and a good candidate for directed evolution [23].

Library Generation (Evolution Phase):

- For each enzyme identified as a bottleneck, generate a mutant library using error-prone PCR or other mutagenesis techniques.

- The libraries are designed to explore sequence space around each bottlenecked enzyme [23].

Parallel Debottlenecking (Screening Phase):

- Objective: To find optimal enzyme variants by considering synergistic effects across the entire pathway.

- Method: Rather than evolving enzymes in isolation, screen the mutant libraries combinatorially. This involves co-transforming the library of one bottlenecked enzyme with the libraries of other pathway enzymes and screening for clones that restore or exceed original production levels.

- Outcome: This step identifies beneficial mutations that work cooperatively across different enzymes, effectively "debottlenecking" the pathway along a more predictable fitness landscape [23].

Machine Learning-Aided Flux Balancing (Optimization Phase):

- Objective: To fine-tune the expression levels of all evolved pathway genes for maximum flux toward the product.

- Method: Use a machine learning model, such as ProEnsemble. Train the model on data comprising different promoter combinations (controlling gene expression) and their corresponding product titers.

- Output: The model predicts the optimal promoter combination to balance metabolic flux, which is then implemented in the final strain [23] [25].

Validation: Ferment the final engineered strain and quantify the product titer, yield, and productivity [23].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and tools used in the successful implementation of this strategy for naringenin production [23].

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| E. coli chassis strain | Heterologous production host for the reconstructed metabolic pathway. |

| Naringenin pathway genes | The enzymatic components for the biosynthetic pathway (e.g., TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI). |

| Promoter library | A set of constitutive promoters of varying strengths used for bottlenecking and final flux balancing. |

| ProEnsemble ML model | A machine learning model trained to predict optimal gene expression levels from promoter performance data. |

| Automated Biofoundry | Robotics system for high-throughput strain construction, library screening, and fermentation. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the main advantage of the Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking strategy over traditional directed evolution? Traditional directed evolution often evolves pathway enzymes sequentially or in isolation, which can fail due to complex epistasis. This strategy uses bottlenecking to force the pathway into a state where the fitness landscape is simpler and more predictable, allowing for effective parallel evolution of all enzymes and the discovery of synergistic mutations [23].

Q2: Within the broader thesis of debugging metabolic pathways, what problem does this strategy specifically solve? It specifically addresses the challenge of unpredictable evolutionary landscapes in complex pathways. When multiple enzymes are evolved, epistatic interactions mean that a beneficial mutation in one enzyme might be neutral or deleterious in the context of mutations in another. This strategy creates a controlled evolutionary trajectory that manages this complexity [23].

Q3: How long does a typical Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking cycle take? In the cited research, the entire process—from initial bottlenecking to the creation of a chassis with evolved and balanced pathway genes—was completed in approximately six weeks, demonstrating its efficiency for rapid strain development [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Diversity in Screening Hits After Debottlenecking

- Potential Cause: The bottlenecking phase was too severe, constraining the enzyme to a point where very few mutations can restore function.

- Solution: Titrate the bottlenecking intensity. Use a range of promoter strengths to weakly constrain the enzyme, allowing for a broader set of potential improving mutations to be discovered during debottlenecking [23].

Problem: Machine Learning Model (ProEnsemble) Fails to Identify a Superior Combination

- Potential Cause 1: The training dataset for the model is too small or lacks diversity, failing to capture the underlying relationship between expression and titer.

- Solution: Expand the high-throughput screening effort to generate a larger and more comprehensive dataset of promoter combinations and their corresponding production metrics.

- Potential Cause 2: A hidden bottleneck exists outside the targeted pathway, such as in central metabolism or cofactor availability.

- Solution: Profile intracellular metabolites to identify accumulation or depletion of pathway intermediates. This may require broadening engineering efforts to the host's native metabolism [26].

Problem: Final Strain Titer is High, but Productivity/Rate is Low

- Potential Cause: The optimization focused solely on titer (final concentration) without considering productivity (rate of production). The pathway may be unbalanced during the growth phase.

- Solution: Implement dynamic regulation or multi-phase fermentation processes where pathway expression is induced after achieving high cell density, separating growth from production phases [26].

Performance Data

The effectiveness of the Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking strategy is demonstrated by its application in producing high-value compounds. The table below summarizes key outcomes from the primary research study [23].

| Metric | Result Before Optimization | Result After Strategy Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Naringenin Titer | Low baseline | 3.65 g L⁻¹ |

| Development Time | N/A | ~6 weeks |

| Key Enabling Tools | N/A | Bottlenecking-Debottlenecking, ProEnsemble ML model |

| Additional Benefit | N/A | Optimized chassis also enhanced production of other flavonoids |

Leveraging Machine Learning and ProEnsemble for Predictive Flux Balancing

Within metabolic engineering, the processes of debugging (identifying and correcting errors in engineered genetic constructs) and debottlenecking (alleviating limiting steps in metabolic pathways) are critical for developing efficient microbial cell factories. The integration of mechanistic models like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with data-driven Machine Learning (ML) models creates a powerful hybrid framework to address these challenges. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers employing these advanced methodologies, directly addressing common experimental hurdles in the context of a broader thesis on improving constructed metabolic pathways.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental advantage of combining ML with FBA?

Answer: The combination leverages the strengths of both approaches while mitigating their individual weaknesses.

- FBA provides a knowledge-driven, mechanistic framework based on biochemical stoichiometry and network topology for predicting metabolic fluxes at a genome-scale [27].

- ML offers a data-driven approach that can learn complex, non-linear patterns from large, multi-omics datasets without requiring a priori knowledge of all underlying mechanisms [28].

- The Integrated Advantage: This hybrid approach allows you to use FBA to narrow down a vast genetic design space and then employ ML to model the complex, multi-level regulation (transcriptional, allosteric) that is not fully captured by stoichiometric models alone. This has been shown to successfully predict high-performing strains for compounds like tryptophan, surpassing the performance of the training data [28].

FAQ 2: My FBA predictions are biologically unrealistic. How can I resolve conflicts between different model constraints?

Problem: FBA predictions may suggest thermodynamically infeasible pathways or conflict with enzyme capacity constraints, often due to the model's assumption of "free" intermediate metabolites that are, in reality, channeled by enzyme complexes [29].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify Anomalies: Use Thermodynamic Driving Force (MDF) analysis to check if predicted pathways are thermodynamically feasible [29].

- Check for Enzyme Compartmentalization: Investigate if the unrealistic flux is caused by ignoring the physical channeling of metabolites within multi-functional enzymes or enzyme complexes. Model these compartments explicitly [29].

- Rational Reaction Combination: Manually group reactions that are catalyzed by a single enzyme complex into a single, combined reaction within the model. This prevents the model from treating channeled intermediates as free pools and corrects pathway structures [29].

- Re-run and Validate: Execute the FBA with the corrected model and validate the new predictions against experimental data, such as measured uptake/excretion rates or known essential genes.

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for preparing data to train ML models for flux prediction?

Problem: ML model performance is highly dependent on the quality and structure of the input data.

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Step | Action | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Ensure High Variation | Construct a combinatorial library that maximizes genotypic and phenotypic diversity [28]. | Provides a rich dataset for the ML algorithm to learn meaningful patterns. |

| 2. Use High-Throughput Biosensors | Employ biosensors that link product concentration to a fluorescent signal [28]. | Enables accurate, high-throughput phenotyping of thousands of strain variants, generating the large datasets needed for ML. |

| 3. Feature Selection | Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Random Forest to identify the most important variables from your multi-omics data [27]. | Reduces data dimensionality, improves model performance, and aids interpretation. |

| 4. Choose the Right ML Algorithm | Select algorithms based on your goal: classification (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Random Forest) or regression (e.g., Lasso, Neural Networks) [27]. | Matches the model to the specific predictive task (e.g., classifying flux states vs. predicting continuous titer levels). |

FAQ 4: Which tools and databases are essential for building and analyzing metabolic pathways?

Problem: Researchers need to find and reuse existing biological knowledge to build accurate models.

Solution: The table below lists key resources for pathway modeling and analysis.

Table 1: Essential Resources for Pathway Research

| Resource Type | Name | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Databases | Reactome, WikiPathways, KEGG, BioCyc [13] | Provide curated pathway models and information from published literature. |

| Interaction Databases | STRING, IntAct, Complex Portal [13] | Offer protein-protein and genetic interaction data to inform network connections. |

| Entity Annotation | UniProt (proteins), ChEBI (chemicals), Ensembl (genes) [13] | Provide standardized, resolvable identifiers for precise annotation of model components. |

| Modeling & Simulation | Pathway Tools, CellDesigner, COBRA Toolbox (implied) | Tools for creating, visualizing, and simulating pathway models (e.g., using SBGN, SBML). |

| ML-FBA Integration | Tools like PMFA, GEESE [27] | Dedicated tools for applying machine learning to flux balance analysis data. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: A Hybrid FBA-ML Workflow for Metabolic Engineering

This protocol outlines the "design-build-test-learn" cycle for optimizing a metabolic pathway, as demonstrated for tryptophan production in yeast [28].

Diagram 1: Hybrid FBA-ML Engineering Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- FBA-Guided Target Identification:

- Use a genome-scale model (GSM) of your host organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae).

- Simulate growth and product synthesis to pinpoint gene targets whose manipulation may enhance flux toward your desired product. For tryptophan, this included genes in the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) and glycolysis [28].

Combinatorial Library Design:

- Select a set of well-characterized, sequence-diverse promoters (e.g., 25-30) from transcriptomics data mining [28].

- Combine these promoters with the target genes identified by FBA to define a comprehensive library of genetic designs.

Strain Construction:

- Create a platform strain by deleting or knocking down the native target genes. Use a helper plasmid to maintain essential genes [28].

- Integrate feedback-resistant enzymes (e.g., ARO4, TRP2 for AAA pathway) to lift native regulation [28].

- Perform a one-pot assembly of the expression cassettes for the target genes into a single genomic locus using high-fidelity homologous recombination and CRISPR/Cas9.

High-Throughput Testing:

- Encode a biosensor for the target metabolite (e.g., tryptophan) into the strain library.

- Use the biosensor's fluorescent output in a high-throughput screen to collect extensive time-series phenotyping data on hundreds of strain variants.

Machine Learning and Validation:

- Train a suite of ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Neural Networks) using the genetic designs (genotype) and biosensor-derived production rates (phenotype).

- Use the trained model to predict the best-performing strain designs from the full, untested library space.

- Validate the top ML-predicted strains by physically constructing them and measuring final product titer and productivity in bioreactors.

Protocol 2: Debugging Pathway Models with Standardized Naming

Problem: A pathway model is not reusable or fails during computational analysis due to inconsistent or ambiguous entity names.

Solution: Follow a strict curation protocol for naming and annotation [13].

Diagram 2: Pathway Model Curation Protocol

Detailed Methodology:

- Reuse Existing Models: Before building a new model, search databases like Reactome, WikiPathways, and KEGG for relevant content that can be extended or cited [13].

- Determine Scope: Decide on the boundaries and level of detail. For enrichment analysis, smaller, focused pathways perform better than large meta-pathways [13].

- Use Standard Identifiers: Annotate all entities with resolvable identifiers from authoritative databases.

- Genes: Use NCBI Gene or Ensembl IDs.

- Proteins: Use UniProt IDs.

- Chemicals: Use ChEBI or LIPID MAPS IDs.

- Complexes: Use Complex Portal IDs [13].

- Export in Standard Formats: Use data exchange formats like SBML or BioPAX to ensure your model is interoperable and reusable by other tools and researchers [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for ProEnsemble and ML-guided FBA Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GSM) | Mechanistic basis for predicting metabolic fluxes and identifying initial engineering targets. | Model for host organism (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) from resources like BioModels [27] [28]. |

| Promoter Library | Provides a range of transcriptional strengths to vary gene expression levels in combinatorial libraries. | A set of 25-30 sequence-diverse promoters mined from transcriptomic data [28]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Enables precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and multiplexed assembly of pathway variants. | Plasmid-based or endogenous system for the host organism [28]. |

| Metabolite Biosensor | Allows high-throughput screening of strain libraries by linking intracellular metabolite concentration to a measurable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | Engineered transcription factor-based biosensor for the target product (e.g., tryptophan) [28]. |

| ML Software Packages | Trains predictive models on genotype-phenotype data to recommend optimal designs. | Python libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, TensorFlow) or specialized tools like PMFA [27]. |

| Enzyme Constraints | Adds realism to FBA by accounting for the limited catalytic capacity of enzymes, based on proteomic data and kinetic parameters. | kcat values from databases like BRENDA incorporated into the GSM [29]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common fermentation problems encountered in a research or production setting? Two of the most common challenges are proper yeast nutrition and fermentation temperature control [30]. Inadequate nutrition can lead to stuck or sluggish fermentations and the production of off-flavors, while incorrect temperatures can stress microbial cells, slowing metabolism at low temperatures or causing loss of delicate aromas and the production of undesirable compounds like hydrogen sulfide at high temperatures [30]. For engineered strains, these issues are compounded by the metabolic burden of heterologous pathways.

FAQ 2: Why is my fermentation process unstable, yielding different results batch-to-batch? Batch-to-batch variability often stems from inconsistencies in strain performance, media composition, or fermentation parameters [31]. An unoptimized strain may not consistently express the target product. Small changes in the quality or concentration of raw materials in the media, or fluctuations in physical parameters like temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen, can significantly impact bioactivity, purity, and final product stability [31]. Systematic optimization and control are essential for reproducibility.

FAQ 3: How can I optimize a fermentation process for a newly engineered metabolic pathway? A systematic, multi-scale approach is recommended. This begins with strain screening and improvement, followed by media and fermentation parameter optimization at a small scale [31]. Tools like single-factor experiments and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) can efficiently identify optimal conditions [32] [33]. The process must then be validated and scaled up, investigating the effects of agitation strategies and pH control in bioreactors [32]. Modular pathway engineering is a powerful strategy to balance the heterologous pathway with endogenous metabolism for improved product titers [34].

FAQ 4: What is modular pathway engineering and how does it aid in debottlenecking? Modular pathway engineering involves the systematic assembly and optimization of distinct metabolic modules to balance the entire cellular network for production [34]. Unlike traditional methods that may address one bottleneck at a time, modular engineering simultaneously optimizes multiple parts of the biosynthesis pathway and related metabolic networks. This avoids a scenario where eliminating one limitation introduces another, thereby globally regulating resource allocation (e.g., carbon and energy) to enhance the yield of the target product [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low or No Product Yield in Engineered Strain

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden | Analyze growth curve; compare with wild-type strain. Measure central metabolite levels. | Refactor the heterologous pathway using modular engineering to balance expression [34]. |

| Insufficient Nutrient Availability | Check OD600 and nutrient depletion profiles. | Optimize carbon and nitrogen sources and their concentrations via single-factor and RSM experiments [32] [33]. |

| Suboptimal Physical Conditions | Monitor temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen in real-time. | Determine and control for optimal parameters. For example, a two-stage agitation strategy or allowing pH to fluctuate freely can enhance yield [32]. |

| Competing Pathways | Analyze for accumulation of unexpected by-products (e.g., lactate, acetate). | Knock out genes for by-product synthesis (e.g., ldh, pta) to redirect carbon flux [34]. |

Problem 2: Fermentation Stalls or is Unusually Slow

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Yeast/Nutrient Health | Check viability of starter culture. Test nutrient levels in must/wort. | Rehydrate yeast properly before inoculation [35]. Add complex yeast nutrients to cover potential deficiencies [30]. |

| Incorrect Temperature | Log temperature data throughout fermentation. | Move fermentation to an environment within the optimal range for the specific microbe (e.g., 30°C for some Bacillus strains) [33] [30]. |

| Inhibitory Compound Accumulation | Test for high levels of metabolic by-products like sulfur compounds. | If a "rotten egg" smell is present, aerate the ferment and ensure proper nutrient levels to relieve yeast stress [36]. |

Problem 3: Undesirable By-Products or Off-Flavors

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Stressed Microbes | Correlate off-flavor detection (e.g., hydrogen sulfide) with temperature logs. | Improve temperature control. For barrel fermentations, use cooling strategies to prevent overheating [30]. |

| Contamination | Plate fermentation broth on non-selective media and look for morphologically distinct colonies. | Ensure strict sanitation of all equipment. Discard contaminated batches and sterilize equipment before restarting [36]. |

| Unbalanced Metabolic Pathway | Analyze intermediate metabolites in the engineered pathway. | Use synthetic small RNAs (sRNAs) to fine-tune the expression of native genes that compete for precursors, rebalancing the metabolic network [34]. |

Optimized Fermentation Parameters from Literature

The table below summarizes key parameters from published optimization studies, providing a reference for initial experimental setup.

| Organism | Optimal Temperature | Optimal pH | Key Media Components | Agitation Strategy | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rossellomorea marisflavi NDS | 32 °C | 7.3 (free fluctuation beneficial) | 1% corn flour, 1% peptone, 0.3% beef extract, 0.2% KCl | Two-stage: 150 rpm (0-20h), then 180 rpm (20-32h) | Enhanced single cell protein yield | [32] |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ck-05 | 30 °C | 6.6 | Soluble starch, peptone, magnesium sulfate | 150 rpm | OD600 increased by 72.79% | [33] |

| Bacillus subtilis (GlcNAc production) | 37 °C | N/A | Defined fermentation medium | N/A | GlcNAc titer reached 31.65 g/L in fed-batch | [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Factor and Response Surface Methodology for Media Optimization

This methodology is effective for systematically optimizing culture medium and conditions [32] [33].

- Strain Activation: Inoculate the strain from a glycerol stock into a liquid medium (e.g., LB). Incubate with shaking until growth is observed [33].

- Seed Culture Preparation: Inoculate a single colony or a volume of activated culture into a fresh flask of basic medium. Grow to the mid-exponential phase to create a standardized inoculum [32] [33].

- Single-Factor Experiments:

- Carbon/Nitrogen Source Screening: Prepare basal media where a single component (e.g., carbon source) is replaced with different alternatives (e.g., glucose, sucrose, starch, etc.), keeping other factors constant [32] [33].

- Physical Parameter Testing: Cultivate the strain in the optimal medium while varying one physical parameter at a time (e.g., temperature from 25-45°C, pH from 5.7-8.1) [33].

- Analysis: After a fixed fermentation time, measure the response variable (e.g., OD600 for biomass, or a specific product assay). Identify the best-performing factor level for each parameter.

- Statistical Optimization with RSM:

- Plackett-Burman (PB) Design: Use this design to screen a large number of factors and identify the most significant ones that impact the response [33].

- Box-Behnken Design (BBD): For the significant factors identified in the PB design, use a BBD to model the response surface. This design helps understand the interaction effects between factors and pinpoint the true optimum [33].

- Validation: Perform fermentation runs using the predicted optimal conditions from the RSM model and compare the results with the model's predictions.

Protocol 2: Modular Pathway Engineering for Metabolic Debottlenecking

This protocol outlines a strategy to balance an engineered pathway with host metabolism [34].

- Divide the Metabolic Network: Segment the relevant metabolism into modules (e.g., "Product Synthesis Module," "Glycolysis Module," "Precursor Consumption Module").

- Strengthen the Product Synthesis Module: Overexpress the heterologous and native genes critical for the target product's biosynthesis. Use promoter engineering to fine-tune the expression levels of each gene to avoid imbalances that could inhibit growth [34].