CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Pathway Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screening for optimizing metabolic pathways in microbial hosts.

CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Pathway Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screening for optimizing metabolic pathways in microbial hosts. It covers foundational principles, including the mechanism of dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression and its advantages over nuclease-active CRISPR systems for metabolic engineering. The content explores advanced methodological applications such as titratable repression, combinatorial multi-gene regulation, and high-throughput screening strategies using biosensors. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects like off-target effects, sgRNA design optimization, and screening data interpretation. Finally, it examines validation techniques and comparative analysis with other gene regulation tools, offering researchers and drug development professionals a practical framework for implementing CRISPRi to enhance bioproduction and accelerate therapeutic development.

Understanding CRISPRi: Foundational Principles for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering, primarily through two distinct mechanistic paradigms: nuclease-active editing and dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression. Nuclease-active CRISPR-Cas9 utilizes the catalytically competent Cas9 enzyme to create double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in genomic DNA, activating endogenous DNA repair mechanisms that can result in gene knockout through insertions or deletions (indels) [1]. In contrast, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) employs a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that retains DNA-binding capability but lacks cleavage activity [1]. This system functions as a programmable transcriptional regulator that can precisely modulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [2]. For metabolic pathway optimization research, understanding the fundamental distinctions between these approaches is crucial for selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental goals, whether complete gene ablation or fine-tuned transcriptional control is required.

Core Mechanism and Molecular Consequences

Fundamental Mechanism of Action

The primary distinction between these technologies lies in their fundamental mode of action and consequent cellular effects, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression and nuclease-active editing

| Parameter | dCas9-Mediated Transcriptional Repression (CRISPRi) | Nuclease-Active Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Status | Catalytically dead (dCas9) | Catalytically active |

| DNA Cleavage | None | Double-stranded breaks (DSBs) |

| Mechanism | Blocks RNA polymerase binding or elongation; recruits repressive chromatin modifiers [1] [2] | Activates non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) [1] |

| Genetic Outcome | Reversible transcription inhibition | Permanent indels or specific sequence changes |

| Expression Effect | Tunable knockdown | Complete knockout (via frameshift) |

| DNA Damage Response | Not triggered | Activated [2] [3] |

| Off-Target Concerns | Primarily on-target binding specificity | DNA cleavage at off-target sites |

| Theoretical Applications | Functional genomics, essential gene studies, metabolic fine-tuning [4] [2] | Gene knockout, gene correction, therapeutic mutation repair |

CRISPRi Repression Mechanisms and Enhancements

The core CRISPRi system consists of two primary components: the dCas9 protein and a customizable single-guide RNA (sgRNA) complementary to the target gene's promoter region [1]. The binding of the dCas9/sgRNA complex to DNA causes transcriptional interference by physically blocking RNA polymerase binding or transcription elongation [1]. This mechanism functions analogously to RNA interference (RNAi) in achieving gene silencing but operates at the transcriptional (DNA) level rather than post-transcriptional (mRNA) level [1].

Advanced CRISPRi platforms significantly enhance repression efficiency by fusing dCas9 to transcriptional repressor domains. The most common fusion partners include:

- KRAB (Krüppel-associated box) domain: Recruits endogenous repressive complexes that promote heterochromatin formation [2] [5]

- Novel repressor combinations: Recent engineering efforts have identified superior repressors such as dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), which shows significantly enhanced target gene silencing and reduced variability across gene targets and cell lines [2]

Table 2: Experimentally determined performance metrics of CRISPR technologies

| Performance Metric | CRISPRi | Nuclease-Active Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Knockdown/Knockout Efficiency | Up to 20-30% improvement with novel repressors like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) compared to earlier versions [2] | Highly variable; depends on repair pathway utilization |

| Detection of Essential Genes | >90% detection rate with compact 5 sgRNA/gene library [6] | Comparable but with more false positives due to DNA damage toxicity |

| Non-Specific Toxicity | No detectable non-specific toxicity [6] | Observable DNA damage toxicity [6] |

| On-Target Errors | Minimal (near zero) [3] | Can reach 10-16% incorrectly edited cells [3] |

| Editing Accuracy | 90-99.6% [3] | 10-38% [3] |

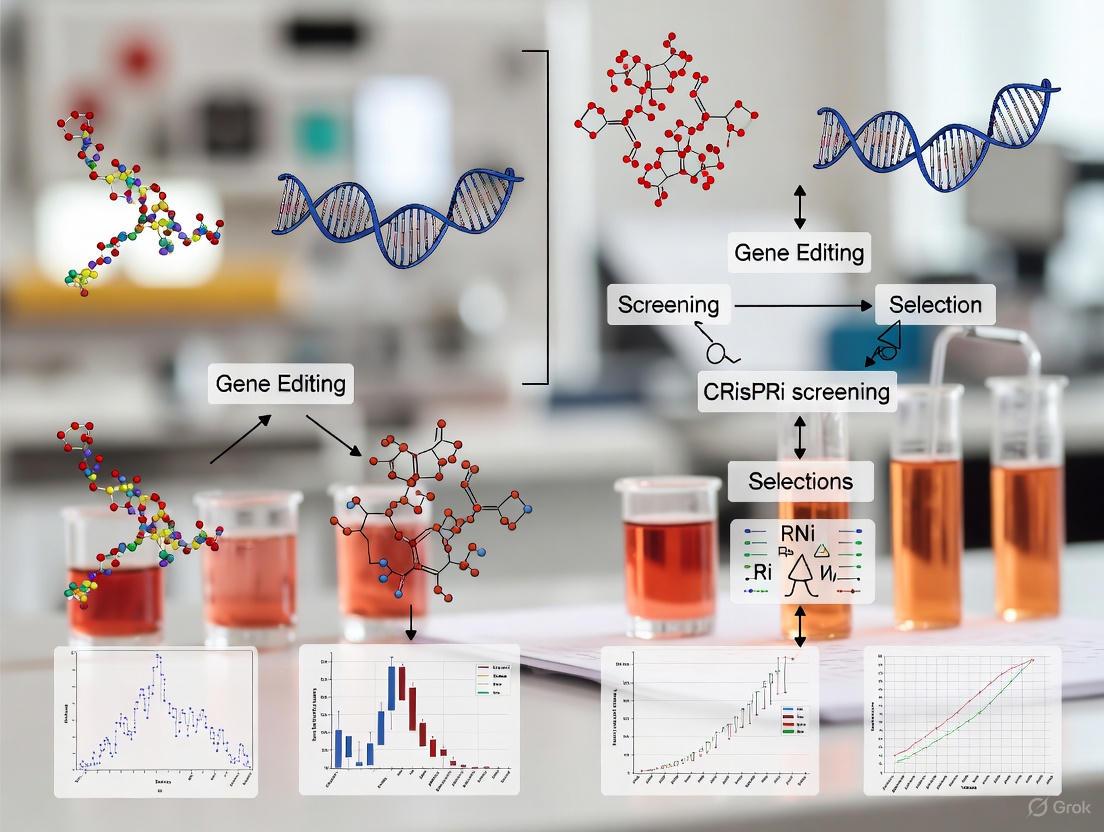

Diagram 1: CRISPRi mechanism showing dCas9/sgRNA binding and transcriptional repression. The core dCas9/sgRNA complex binds target DNA, physically blocking transcription. When fused to repressor domains like KRAB, additional chromatin modifications enhance silencing.

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

CRISPRi Implementation for Metabolic Engineering

Protocol: Establishing a CRISPRi System for Bacterial Metabolic Pathway Optimization Application: Dynamic regulation of TCA cycle for d-pantothenic acid production in Bacillus subtilis [4]

Materials and Reagents:

- dCas9 Expression Vector: Contains dCas9 gene fused to repressor domains (e.g., KRAB)

- sgRNA Expression Vector: With customizable spacer sequence for target gene

- Host Strain: Bacillus subtilis MU8 or appropriate production chassis

- Culture Media: M9 medium (14 g/L K₂HPO₄·3H₂O, 5.2 g/L KH₂PO₄, 2 g/L (NH₄)₂SO₄, 0.3 g/L MgSO₄, 1g/L tryptone with 10 g/L glucose) [4]

- Antibiotics for Selection: Bleomycin (20 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), erythromycin (5 μg/ml), spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), or kanamycin (15 μg/ml) [4]

Methodology:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNA complementary to the promoter region of target metabolic gene (e.g., citZ encoding citrate synthase for TCA cycle regulation). Optimal targeting occurs -50 to +300 bp relative to transcription start site [6].

- Vector Construction: Clone sgRNA expression cassette into appropriate vector backbone containing terminator sequences.

- Strain Transformation: Introduce dCas9 and sgRNA vectors into production host via electroporation or chemical transformation.

- Screening and Validation: Select transformants on appropriate antibiotic plates. Validate repression efficiency via:

- qRT-PCR to measure transcript levels

- Western blotting to assess protein reduction

- Functional assays for metabolic flux changes

- Fermentation Optimization: Cultivate engineered strains in 5L fed-batch fermentations with appropriate feeding strategy [4].

- Product Quantification: Analyze DPA titers via HPLC or LC-MS at 24-hour intervals.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Incomplete repression may require sgRNA redesign or testing multiple target sites

- Growth defects may indicate excessive repression of essential pathways

- For dynamic control, consider integrating quorum-sensing systems for autonomous regulation [4]

Advanced CRISPRi Screening Protocol

Protocol: Genome-wide CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Gene Identification Application: Identification of genes affecting cisplatin response in human gastric organoids [5]

Materials and Reagents:

- Inducible dCas9-KRAB Cell Line: TP53/APC double knockout gastric organoid line with doxycycline-inducible dCas9-KRAB system [5]

- sgRNA Library: Genome-scale human CRISPRi-v2 library with 5-10 sgRNAs per gene [6]

- Lentiviral Packaging System: For sgRNA library delivery

- Culture Reagents: Appropriate organoid culture media with growth factors

- Doxycycline: For induction of dCas9-KRAB expression

- Selection Antibiotics: Puromycin for selection of transduced cells

- Cisplatin: For drug treatment screens

Methodology:

- Cell Line Preparation: Culture iCRISPRi organoids and confirm dCas9-KRAB expression via Western blot after doxycycline induction (1 μg/mL) [5].

- Virus Production and Transduction: Package sgRNA library into lentiviral particles. Transduce organoids at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single sgRNA integration.

- Selection and Expansion: Treat with puromycin (dose optimized for organoids) 48 hours post-transduction. Maintain >1000 cells per sgRNA throughout screening to preserve library representation [5].

- Drug Treatment Screen: Split organoids into control and treatment groups after puromycin selection. Treat with IC₅₀ concentration of cisplatin for 7-14 days.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest organoids at multiple timepoints. Extract gDNA and amplify integrated sgRNAs with barcoded primers for next-generation sequencing.

- Hit Identification: Calculate sgRNA abundance changes between treatment and control using MAGeCK or similar algorithms. Identify significantly depleted or enriched sgRNAs (FDR < 0.05).

Validation:

- Confirm hits using individual sgRNAs rather than pooled library

- Measure growth inhibition via cell viability assays

- Assess transcriptomic changes via single-cell RNA sequencing if applicable [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key research reagents for dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Vector | Encodes catalytically dead Cas9 protein | pLV-dCas9-KRAB; with repressor domain fusions (KRAB, MeCP2, ZIM3) [2] [5] |

| sgRNA Library | Targets dCas9 to specific genomic loci | hCRISPRi-v2 library; 5-10 sgRNAs/gene; designed with chromatin accessibility algorithms [6] |

| Repressor Domains | Enhances transcriptional repression efficiency | KRAB, ZIM3(KRAB), MeCP2(t); novel combinations show 20-30% improvement [2] |

| Induction System | Controls dCas9 expression temporally | Doxycycline-inducible systems (rtTA); enables timed repression [5] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Lentiviral vectors (for stable integration); AAV vectors (for in vivo applications) [3] |

| Validation Tools | Confirms repression efficiency | qRT-PCR reagents; Western blot equipment; flow cytometry antibodies [5] |

Diagram 2: CRISPRi screening workflow for metabolic pathway research. The process begins with research question formulation, proceeds through sgRNA design and system delivery, includes induction and treatment phases, and concludes with analysis and target identification.

Application in Metabolic Pathway Optimization

The application of dCas9-mediated transcriptional repression in metabolic pathway optimization represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, enabling precise control of flux through competing pathways without permanent genetic alterations. In one compelling example, researchers developed a quorum sensing-controlled type I CRISPRi system (QICi) in Bacillus subtilis that dynamically regulated the TCA cycle by repressing citrate synthase (citZ), resulting in dramatic increases in d-pantothenic acid (DPA) production—achieving titers of 14.97 g/L in 5L fed-batch fermentations without precursor supplementation [4]. Similarly, QICi-mediated repression of glycolysis genes redirected metabolic flux into the pentose phosphate pathway, boosting riboflavin production by 2.49-fold [4].

For pharmaceutical applications, CRISPRi has been instrumental in optimizing secondary metabolic pathways in medicinal plants. By precisely regulating key enzymes and transcription factors in biosynthetic pathways for valuable compounds like tanshinone, artemisinin, and ginsenosides, researchers have enhanced both the yield and quality of active ingredients in medicinal plants [7]. This approach demonstrates the particular advantage of CRISPRi for fine-tuning complex metabolic networks where complete gene knockout would be detrimental to cell viability or pathway function.

The reversibility of CRISPRi-mediated repression makes it uniquely suited for optimizing essential gene expression in metabolic engineering, allowing researchers to balance cell growth with product synthesis by titrating repression levels rather than eliminating gene function entirely [4]. This precise control enables sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies that were previously challenging with all-or-nothing nuclease approaches.

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful and versatile tool for metabolic engineering, enabling precise reprogramming of cellular metabolism without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This technology utilizes a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) protein, which binds to target DNA sequences under the guidance of a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) but does not cleave the DNA, thereby serving as a programmable transcriptional repressor [8]. The binding of the dCas9-sgRNA complex to promoter regions or coding sequences physically blocks RNA polymerase, leading to suppressed transcription initiation or elongation [8] [2]. This mechanism allows researchers to dynamically fine-tune metabolic fluxes, address pathway bottlenecks, and redirect cellular resources toward the production of valuable compounds. Within the broader context of CRISPR screening for metabolic pathway optimization, CRISPRi offers distinct advantages for probing gene function and engineering industrial microbes, particularly through its precise tunability, capacity for multiplexed repression, and ability to target essential genes without causing cell death. This application note details these advantages and provides practical protocols for their implementation in metabolic engineering projects.

Key Advantages and Applications

Precise Tunability of Gene Expression

A defining feature of CRISPRi is the ability to finely dial in the level of gene repression, which is crucial for balancing metabolic pathways where complete gene knockout could be detrimental or suboptimal.

- Inducible Systems: Repression levels can be controlled by regulating the expression of dCas9 or the sgRNA. For instance, a L-rhamnose-inducible promoter can control dCas9 expression, allowing researchers to titrate the level of repression by varying the inducer concentration [9]. This enables dynamic control, where repression can be initiated at a specific time in the fermentation process to maximize both cell growth and product formation.

- sgRNA Design: The repression efficiency can also be modulated by designing sgRNAs that target different regions of a gene (e.g., the promoter for strong repression or the coding sequence for moderate repression) and by adjusting the expression level of the sgRNA itself [8] [9].

Table 1: Examples of Tunable CRISPRi for Metabolic Engineering

| Host Organism | Target Gene(s) | Tuning Method | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Mevalonate (MVA) pathway genes | Varying inducer concentration for dCas9 | Enhanced production of isoprene, (-)-α-bisabolol, and lycopene | [9] |

| E. coli | pta, frdA, ldhA, adhE | Inducible dCas9 system | Redirected carbon flux, increasing n-butanol yield 5.4-fold | [9] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | Flux-control genes | Promoter libraries to control sgRNA/dCas9 | Optimized L-proline biosynthesis flux | [10] |

Multiplexed Repression of Gene Networks

Metabolic engineering often requires simultaneous regulation of multiple genes to effectively rewire complex cellular networks. CRISPRi is exceptionally well-suited for this task.

- sgRNA Arrays: Multiple sgRNAs can be expressed from a single transcript using a single promoter, reducing the genetic footprint and metabolic burden on the host [11] [9]. Some systems, particularly those based on Cas12a, can autoprocess a single transcript into multiple functional gRNAs, simplifying multiplexed system construction [8].

- Combinatorial Optimization: This capability allows for the exploration of synergistic effects between different genetic perturbations. By repressing combinations of genes involved in competing pathways, researchers can rapidly identify optimal genetic configurations for maximizing product titers.

Table 2: Applications of Multiplexed CRISPRi in Metabolic Engineering

| Application | Host Organism | Multiplexed Targets | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redirect carbon flux | E. coli | pta, frdA, ldhA, adhE (quadruple repression) | Simultaneous reduction of acetate, succinate, lactate, and ethanol; enhanced n-butanol production | [9] |

| Combinatorial metabolic engineering | S. cerevisiae | Orthogonal CRISPRa, CRISPRi, and CRISPRd | 3-fold increase in β-carotene production; 2.5-fold improvement in endoglucanase display | [11] |

| Genome-wide screening | E. coli, B. subtilis | Library of gRNAs targeting all transporters | Discovery of novel L-proline exporter (Cgl2622) in C. glutamicum | [10] |

Targeting Essential Genes and Minimizing Cellular Toxicity

Unlike nuclease-active CRISPR-Cas systems that cause irreversible double-strand breaks (DSBs), CRISPRi is a reversible and non-mutagenic tool, making it ideal for manipulating essential genes.

- Reversible Knockdown: CRISPRi results in transcriptional repression rather than permanent gene deletion. This allows for the functional study and modulation of essential genes required for cell viability or central metabolism without causing cell death [9] [2].

- Reduced Toxicity and Unwanted DNA Damage: The use of dCas9 eliminates the cytotoxic effects associated with DSBs, such as the activation of DNA damage response pathways and potential chromosomal rearrangements. This leads to more robust and interpretable results in functional genomics screens and industrial bioprocessing [12] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CRISPRi-Mediated Multiplex Repression in E. coli

This protocol outlines the steps for repressing multiple genes in E. coli to redirect metabolic flux, based on the work for n-butanol production [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Example/Description |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Plasmid | Encodes the nuclease-deficient Cas9 protein. | Use a plasmid with a tightly regulated, inducible promoter (e.g., L-rhamnose-inducible) to control dCas9 expression and minimize toxicity [10] [9]. |

| sgRNA Expression Plasmid | Encodes the guide RNA(s) targeting specific genes. | For multiplexing, use a plasmid with a constitutive promoter (e.g., J23119) expressing an array of sgRNAs targeting genes like pta, frdA, ldhA, and adhE [9]. |

| Host Strain | The microbial chassis for metabolic engineering. | An E. coli strain engineered with a heterologous n-butanol production pathway (e.g., pAB-HCTA plasmid) [9]. |

| Inducer | A molecule to precisely control dCas9 expression. | L-rhamnose for induction of the dCas9 gene in the system described [9]. |

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Cloning: Design sgRNAs with 20-nt protospacer sequences complementary to the non-template strand of the target gene's promoter or transcription start site. For multiplex repression, synthesize an sgRNA array where individual sgRNA sequences are separated by direct repeats (for Cas12a systems) or expressed as a polycistronic transcript [8] [9]. Clone this array into an sgRNA expression plasmid.

- Strain Transformation: Co-transform the dCas9 expression plasmid and the sgRNA array plasmid into your production E. coli strain. Include controls (e.g., strain with dCas9 but non-targeting sgRNA).

- Cultivation and Induction: Inoculate transformants into a suitable medium with appropriate antibiotics. Grow cultures to mid-exponential phase and then induce dCas9 expression by adding a predetermined optimal concentration of L-rhamnose.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Repression Efficiency: After several hours of post-induction growth, harvest cells. Analyze transcript levels of target genes using RT-qPCR to quantify repression.

- Phenotypic Analysis: Measure the concentration of pathway byproducts (acetate, succinate, lactate, ethanol) and the desired product (n-butanol) in the culture supernatant using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Fermentation: Perform fed-batch fermentations with the best-performing strain to assess production metrics (titer, yield, productivity) under scaled-up conditions.

Protocol: Arrayed CRISPRi Screening for Transporter Discovery

This protocol describes the use of an arrayed CRISPRi library to identify novel transporters, as demonstrated for L-proline export in C. glutamicum [10].

Procedure:

- Library Design: Design a genome-wide arrayed CRISPRi library where each well in a multi-well plate contains a single strain with a unique sgRNA targeting a specific gene. For focused screens, target a specific gene family (e.g., all 397 predicted transporters in C. glutamicum).

- Strain Array Construction: Introduce each sgRNA plasmid into a Cas9-expressing production host. This can be done via high-throughput transformation or conjugation, maintaining the arrayed format.

- Screening:

- Grow the arrayed strains in a defined medium under selective pressure for the desired phenotype (e.g., L-proline overproduction).

- After a suitable incubation period, measure the growth (OD600) and L-proline accumulation in the medium for each well. Strains with repressed proline exporters may show higher intracellular but lower extracellular proline, while successful exporter discovery will correlate with higher extracellular titers.

- Hit Validation: Isolate candidate strains showing improved product export or tolerance. Re-test these hits in shake-flask fermentations and validate the repression of the target transporter gene via RT-qPCR. The final validation involves constructing a plasmid-, antibiotic-, and inducer-free production strain with the identified exporter overexpressed for fed-batch fermentation [10].

Concluding Remarks

CRISPRi has firmly established itself as an indispensable component of the metabolic engineer's toolkit. Its core strengths—tunable repression, facile multiplexing, and the ability to target essential genes—provide a level of control that is perfectly suited for the nuanced task of optimizing complex metabolic networks. As the technology continues to evolve with the development of more effective repressor domains [2] and broader host range systems [8], its impact on developing robust microbial cell factories for the sustainable production of biofuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals will only grow. Integrating CRISPRi with other CRISPR-derived tools and multi-omics analyses promises to further accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle, bringing us closer to the goal of predictive and rational metabolic design.

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has emerged as a powerful tool for programmable gene repression, enabling precise metabolic pathway optimization without introducing DNA double-strand breaks. This system primarily utilizes a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) that acts as a DNA-binding platform, single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) for target specificity, and regulatory elements that control system expression and performance. For metabolic engineering, CRISPRi allows fine-tuning of pathway fluxes by selectively repressing competing or bottleneck enzymes, offering significant advantages over complete gene knockout strategies. This application note details the key components, their properties, and practical implementation for effective CRISPRi screening in metabolic pathway optimization.

dCas9 Variants and Selection Criteria

The dCas9 protein serves as the foundational component of CRISPRi systems, with variants offering distinct properties suited to different experimental needs. Selection depends on multiple factors including origin, size, specificity, and compatibility with host organisms.

Table: Comparison of Key dCas9 Variants for Metabolic Engineering

| dCas9 Variant | Origin | Size (aa) | PAM Sequence | Key Features | Optimal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 (Spy) | Streptococcus pyogenes | 1368 | NGG | High efficiency, extensive validation | General purpose screening |

| dCas9 (St1) | Streptococcus thermophilus | 1121 | NNAGAAW (W = A/T) | Efficient in bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria | Dairy and gut microbiome engineering |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-designed | ~1368 | NGG | Improved specificity, 400 mutations from SpCas9 | High-fidelity applications |

| dCas9-KRAB | Fusion protein | ~1600 | NGG | Enhanced repression via KRAB domain | Strong transcriptional repression |

Beyond these well-characterized variants, artificial intelligence is now generating novel editors with optimized properties. OpenCRISPR-1, an AI-designed gene editor, exhibits comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence, demonstrating the potential for tailor-made editors [13]. For metabolic pathway engineering in non-model organisms, sourcing dCas9 from compatible species can significantly improve performance, as demonstrated by the effective use of Streptococcus thermophilus dCas9 in bifidobacteria [14].

For enhanced repression efficiency, dCas9 is typically fused to repressive domains. The most common configuration is dCas9-KRAB (Krüppel-associated box), which recruits chromatin-modifying complexes to establish repressive heterochromatin states [15]. The inducible dCas9-KRAB system enables temporal control of repression, allowing investigation of essential genes whose constitutive repression might affect cell viability [16].

sgRNA Design and Engineering

The single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is a chimeric molecule that combines the functions of crRNA (target recognition) and tracrRNA (scaffold for Cas9 binding) into a single transcript [17]. Proper sgRNA design is critical for maximizing on-target efficiency and minimizing off-target effects in metabolic engineering applications.

Key Considerations for sgRNA Design

Target Selection: The sgRNA should be complementary to the template strand within the promoter region or early coding sequence for transcriptional repression [18]. For metabolic pathway optimization, target the 5' region of genes encoding metabolic enzymes to block transcription initiation or elongation.

PAM Requirement: Each dCas9 variant requires a specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) adjacent to the target site. Verify PAM compatibility between your sgRNA and dCas9 variant [13].

Specificity and Off-Target Potential: Evaluate potential off-target sites across the genome using specialized algorithms. Synthetic sgRNAs with chemical modifications can achieve consistently high editing efficiencies with lower risk of off-target effects [17].

Advanced sgRNA Engineering

For multiplexed metabolic pathway engineering, where multiple genes are targeted simultaneously, competition for dCas9 can significantly alter repression dynamics. To address this, implement a dCas9 regulator that maintains constant apo-dCas9 levels through negative feedback, ensuring consistent repression across all targeted genes regardless of sgRNA load [18].

Table: sgRNA Design Parameters for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

| Parameter | Optimal Configuration | Rationale | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Region | -35 to +50 relative to TSS | Blocks RNA polymerase binding or progression | RNA-seq, RT-qPCR |

| sgRNA Length | 20 nt | Balance of specificity and efficiency | Dose-response curves |

| GC Content | 40-60% | Stability and binding affinity | Melting temperature analysis |

| Off-Target Score | <0.2 (algorithm-specific) | Minimize non-specific binding | Whole-genome sequencing |

| Chemical Modifications | 2'-O-methyl 3' phosphorothioate | Enhanced stability, reduced immune response | Editing efficiency assays |

Regulatory Elements and Circuit Design

Effective CRISPRi systems require precisely engineered regulatory elements to control the expression of dCas9 and sgRNAs. These elements determine system dynamics, leakiness, and compatibility with host organisms.

Expression Systems for dCas9

Constitutive Expression: Strong, constitutive promoters provide consistent dCas9 levels but may cause cellular burden. For metabolic engineering, moderate-strength promoters often provide optimal balance between repression efficiency and growth impact [18].

Inducible Systems: Doxycycline-inducible (Tet-On) systems enable temporal control of dCas9 expression, allowing repression to be initiated at specific growth phases or environmental conditions [15].

Auto-regulatory Circuits: Implement negative feedback control using sgRNA g0 to maintain constant apo-dCas9 levels, neutralizing competition effects in multiplexed repression [18].

sgRNA Expression Platforms

Polycistronic tRNA-gRNA Arrays: Enable simultaneous expression of multiple sgRNAs from a single transcript for multiplexed metabolic engineering.

Inducible Promoters: Chemical or environmental inducers allow dynamic control of sgRNA expression, enabling sequential rather than simultaneous gene repression.

Library Formats: For CRISPRi screening, sgRNA libraries are typically cloned into lentiviral vectors with U6 promoters for high-expression in mammalian systems [16].

Experimental Protocol: CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

This protocol outlines the complete workflow for implementing CRISPRi to optimize exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Streptococcus thermophilus, adaptable to other metabolic engineering applications.

System Design and Vector Construction (Days 1-5)

Materials:

- dCas9 expression vector (e.g., pCRISPRi-St1 containing S. thermophilus dCas9)

- sgRNA cloning vector with appropriate promoter

- E. coli DH5α competent cells

- Restriction enzymes (BsaI, BsmBI) or Golden Gate assembly reagents

Procedure:

- Select dCas9 variant appropriate for host organism. For S. thermophilus and related bacteria, use dCas9 from S. thermophilus [19].

- Design sgRNAs targeting metabolic pathway genes (e.g., galK for UDP-glucose metabolism, epsA and epsE for EPS synthesis) following guidelines in Section 3.

- Clone sgRNA expression cassettes into appropriate vectors using Golden Gate assembly or traditional restriction-ligation.

- Sequence confirm constructs and transform into host organism using optimized methods.

Library Delivery and Screening (Days 6-15)

Materials:

- Electroporator or conjugation equipment

- Selection antibiotics

- Metabolite quantification assays (e.g., EPS quantification)

Procedure:

- Deliver CRISPRi constructs to host organism via electroporation or conjugation.

- Plate on selective media and incubate until colonies form.

- Screen for successful transformants via colony PCR and sequencing.

- For pooled screening, harvest cells and quantify target metabolite (e.g., EPS) versus control strains.

Validation and Optimization (Days 16-25)

Materials:

- RNA extraction kit

- RT-qPCR reagents

- Metabolite analysis equipment (HPLC, GC-MS)

Procedure:

- Validate gene repression via RT-qPCR comparing to control strains.

- Quantify metabolic output (e.g., EPS titer) using appropriate analytical methods.

- For multiplexed repression, implement dCas9 regulator circuit if competition effects are observed [18].

- Iterate sgRNA design and targeting strategy based on initial results.

Visualization of CRISPRi Workflows

CRISPRi System Components and Interactions

CRISPRi Component Interactions

Metabolic Pathway Engineering Workflow

Metabolic Engineering Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for CRISPRi Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Systems | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-St1, OpenCRISPR-1 | Transcriptional repression scaffold | Addgene, commercial providers |

| sgRNA Synthesis | RUO sgRNA, INDe sgRNA, GMP sgRNA | Target-specific guide RNA | Synthego, Integrated DNA Technologies |

| Delivery Vectors | Lentiviral, plasmid, integrative vectors | Nucleic acid delivery | Addgene, Thermo Fisher |

| Screening Libraries | Custom sgRNA libraries, genome-wide libraries | High-throughput screening | Custom synthesis providers |

| Validation Reagents | RT-qPCR kits, antibodies, metabolite assays | Experimental confirmation | Various molecular biology suppliers |

Effective CRISPRi screening for metabolic pathway optimization requires careful consideration of three core components: dCas9 variants matched to the host organism, precisely designed sgRNAs with appropriate chemical modifications, and regulatory elements that maintain system functionality under multiplexed conditions. The demonstrated success in optimizing exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Streptococcus thermophilus - achieving approximately 2-fold increase in EPS titer through targeted repression of galK and overexpression of epsA and epsE - highlights the power of this approach [19]. By following the protocols and design principles outlined here, researchers can implement robust CRISPRi systems for metabolic engineering across diverse microbial hosts and pathway configurations.

In the field of metabolic engineering and therapeutic development, achieving precise control over cellular metabolic pathways remains a fundamental challenge. The advent of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technology has revolutionized our approach to modulating gene expression without permanent genetic alterations. This application note details optimized protocols and experimental frameworks for implementing CRISPRi screening to investigate and optimize metabolic flux, enabling researchers to establish critical connections between genetic regulation and pathway performance. By leveraging recent advances in CRISPRi repressor engineering and screening methodologies, scientists can now systematically identify genetic bottlenecks, characterize nutrient transporters, and dynamically balance metabolic pathways for both industrial biomanufacturing and basic research applications. The following sections provide detailed protocols, data analysis frameworks, and practical implementation strategies to accelerate research in this rapidly evolving field.

CRISPRi Platform Selection and Optimization

Next-Generation CRISPRi Repressors

Traditional CRISPRi systems utilizing dCas9 fused to single repressor domains often exhibit variable performance across cell lines and gene targets. Recent protein engineering efforts have developed enhanced CRISPRi platforms through systematic optimization of repressor domains and their configurations:

Novel Repressor Domain Combinations: Screening of bipartite and tripartite repressor fusions has identified several high-performance configurations. The most potent repressor, dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), demonstrates significantly improved gene repression at both transcript and protein levels across multiple cell lines. This fusion reduced variability dependent on guide RNA sequences and showed enhanced performance in genome-wide screens compared to gold-standard repressors [20].

Domain Truncation and Optimization: Truncated versions of established repressor domains maintain functionality while potentially reducing cellular burden. A truncated MeCP2 domain (MeCP2(t)) of only 80 amino acids achieved similar knockdown efficiency as the full-length 283-amino acid version, enabling more compact genetic constructs [20]. Further engineering identified an ultra-compact NCoR/SMRT interaction domain (NID) that enhanced CRISPRi performance by approximately 40% compared to canonical MeCP2 subdomains [21].

Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) Optimization: Strategic placement of NLS sequences significantly impacts CRISPRi efficiency. Incorporating a single carboxy-terminal NLS enhanced gene knockdown efficiency by an average of 50% across tested repressor architectures [21].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimized CRISPRi Repressors

| Repressor Configuration | Relative Efficiency | Key Advantages | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) | ~20-30% improvement vs. dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) | Reduced guide-dependent variability | Multiple cell lines, endogenous targets, genome-wide screens |

| dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS | Superior silencing capability | Enhanced NLS configuration | Genome-wide dropout screens, multiple sgRNA targets |

| dCas9-KOX1(KRAB)-MeCP2(t) | Significant improvement vs. standards | Compact design | Reporter assays, proliferation assays |

| dCas9-KRBOX1(KRAB)-MAX | ~20-30% improvement vs. gold standards | Novel domain combination | GFP reporter assays in HEK293T cells |

Implementation Considerations

When selecting a CRISPRi platform, consider the following factors:

- Cell Line Compatibility: Performance varies across cellular contexts; validate repressor efficiency in your specific model system [20]

- Expression System: Utilize inducible systems where prolonged repressor expression may cause cellular toxicity [22]

- Guide RNA Design: While novel repressors show reduced sequence-dependence, follow established sgRNA design principles for optimal performance [22]

Experimental Protocols for CRISPRi Screening in Metabolic Studies

Protocol 1: Genome-Scale CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Transporters

This protocol adapts methods from a comprehensive nutrient transporter study to identify metabolic dependencies across microenvironmental conditions [23].

Materials and Reagents:

- K562 cells expressing dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi) or dCas9-SunTag (CRISPRa)

- Custom sgRNA library targeting SLC and ABC transporters (10 sgRNAs/gene + 730 non-targeting controls)

- Lentiviral packaging plasmids (psPAX2, pMD2.G)

- Selection antibiotics appropriate for your expression system

- Base medium for screening (e.g., RPMI-1640 without specific nutrients)

- Nutrient stocks for medium supplementation

Procedure:

Library Design and Cloning:

- Design sgRNAs targeting all solute carrier (SLC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in your species of interest

- Include 10 sgRNAs per gene and a minimum of 730 non-targeting control sgRNAs

- Clone library into appropriate lentiviral transfer plasmid under U6 promoter

Lentiviral Production:

- Transfect HEK293T cells with transfer plasmid and packaging plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000

- Collect viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection

- Concentrate virus using ultracentrifugation or PEG precipitation

- Titrate virus using target cells to achieve MOI of 0.3-0.4

Cell Line Engineering and Screening:

- Transduce target cells at low MOI to ensure single integration events

- Select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics for 7 days

- Split cells into experimental conditions (e.g., nutrient-limited media) and control conditions

- Maintain library representation of at least 500 cells per sgRNA throughout screening

- Passage cells every 2-3 days, collecting samples for genomic DNA extraction at multiple timepoints

Sample Processing and Sequencing:

- Extract genomic DNA using salt precipitation method or commercial kits

- Amplify sgRNA regions using nested PCR with barcoded primers for multiplexing

- Purify PCR products and quantify using Qubit dsDNA HS assay

- Sequence on Illumina platform to obtain minimum of 50-100 reads per sgRNA

Data Analysis:

- Process sequencing data using MAGeCK algorithm to calculate enrichment/depletion scores

- Identify significantly enriched/depleted sgRNAs under experimental conditions

- Validate hits using secondary assays before proceeding to functional characterization

Protocol 2: Arrayed CRISPRi Screening for Metabolic Engineering

This protocol describes an arrayed screening approach for identifying optimal metabolic flux modifications, adapted from successful application in Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-proline production [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Arrayed CRISPRi library targeting genes of interest (individual constructs in multi-well format)

- Appropriate microbial or mammalian host strain

- Culture vessels compatible with high-throughput screening (96-well or 384-well plates)

- Metabolite detection system (HPLC, LC-MS, or enzymatic assays)

- Selective media for specific nutrient limitations

Procedure:

Library Design and Validation:

- Select target genes based on prior knowledge of metabolic pathways

- Design 3-5 sgRNAs per target with validated efficiency

- Clone individual sgRNAs into appropriate CRISPRi vectors with different selection markers

- Sequence-verify all constructs before screening

Strain Transformation/Transduction:

- Introduce arrayed CRISPRi constructs into target host using optimized method

- Include non-targeting sgRNA controls and empty vector controls

- For microbial systems, perform transformation in 96-well format

- Select successfully engineered clones with appropriate antibiotics

Phenotypic Screening:

- Inoculate engineered strains into defined media with appropriate carbon sources

- Culture under controlled conditions with monitoring of growth and metabolite production

- For nutrient limitation studies, use media formulations that reduce proliferation by ~50%

- Collect samples at multiple timepoints for endpoint analysis

Metabolite Analysis:

- Quantify target metabolites using appropriate analytical methods

- For amino acids, use HPLC with fluorescence detection or LC-MS

- Measure pathway intermediates to identify flux bottlenecks

- Correlate metabolite levels with growth characteristics

Hit Validation:

- Select top-performing strains for secondary validation in larger culture volumes

- Measure additional parameters: substrate consumption, byproduct formation, growth rate

- Confirm target gene knockdown using qRT-PCR or Western blotting

- Iterate on top hits through combinatorial targeting or promoter engineering

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: L-Proline Hyperproduction in C. glutamicum

A comprehensive metabolic engineering approach combining CRISPRi screening with pathway optimization achieved remarkable L-proline production [10]:

Implementation Framework:

- Enzyme Engineering: Used CRISPR-assisted ssDNA recombineering to screen feedback-deregulated variants of γ-glutamyl kinase (ProB), the key rate-limiting enzyme in L-proline biosynthesis

- Flux Control: Employed in silico analysis to predict flux-control genes, then fine-tuned their expression using tailored promoter libraries

- Transporter Discovery: Constructed an arrayed CRISPRi library targeting all 397 transporters in C. glutamicum to identify the L-proline exporter Cgl2622

Results:

- Final engineered strain produced L-proline at 142.4 g/L titer

- Achieved productivity of 2.90 g/L/h and yield of 0.31 g/g glucose

- Created plasmid-, antibiotic-, and inducer-free production strain suitable for industrial application

Table 2: Metabolic Engineering Outcomes for L-Proline Production

| Engineering Step | Specific Target | Improvement Achieved |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme deregulation | ProB (γ-glutamyl kinase) | Released feedback inhibition by L-proline |

| Flux fine-tuning | Central metabolic genes | Increased carbon flux toward L-proline biosynthesis |

| Transporter discovery | Cgl2622 | Identified and optimized L-proline export |

| Combined optimization | Multiple targets | 142.4 g/L titer, 0.31 g/g yield |

Case Study 2: Dynamic Metabolic Regulation Using Quorum Sensing-CRISPRi

Integration of quorum sensing (QS) circuits with type I CRISPRi systems enabled autonomous dynamic control of metabolic pathways in Bacillus subtilis [4]:

System Design:

- Developed QS-controlled type I CRISPRi (QICi) using PhrQ-RapQ-ComA QS system

- Optimized component expression levels to enhance regulation dynamic range

- Implemented streamlined crRNA vector construction for simplified targeting

Metabolic Applications:

- D-Pantothenic Acid Production: Dynamically regulated citrate synthase (citZ) to balance TCA cycle flux with precursor supply

- Riboflavin Biosynthesis: Suppressed EMP pathway flux to redirect carbon through pentose phosphate pathway

Performance Outcomes:

- Achieved D-pantothenic acid titer of 14.97 g/L in fed-batch fermentation without precursor supplementation

- Increased riboflavin production by 2.49-fold through optimized flux redistribution

- Demonstrated inducer-free autonomous regulation based on cell density signals

Pathway Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

Figure 1: CRISPRi Screening Workflow for Metabolic Optimization

Figure 2: Integration of Genetic Regulation with Metabolic Flux

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPRi Metabolic Screening

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi Repressors | dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), dCas9-ZIM3-NID-MXD1-NLS | Transcriptional repression; Enhanced knockdown efficiency [20] [21] |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, Lipofectamine 2000, Electroporation | Introduction of CRISPRi components into target cells |

| Screening Libraries | Custom SLC/ABC transporter libraries, Arrayed metabolic gene libraries | Targeted interrogation of specific gene families [23] |

| Analytical Tools | LC-MS, HPLC, Seahorse Analyzer, Flow cytometry | Metabolite quantification, metabolic flux analysis, phenotype detection |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MAGeCK, ICE, Benchling sgRNA designer | Screen analysis, editing efficiency quantification, sgRNA design [24] [22] |

| Cell Lines/Strains | K562 CRISPRi/a cells, C. glutamicum, B. subtilis, hPSCs-iCas9 | Optimized host systems for screening [23] [10] [4] |

The integration of advanced CRISPRi platforms with metabolic flux analysis represents a powerful framework for optimizing biological systems across research and industrial applications. The protocols and case studies presented here demonstrate how systematic genetic perturbation screening can identify critical regulatory nodes, characterize nutrient transporters, and dynamically balance metabolic pathways. As CRISPRi technology continues to evolve with enhanced repressor domains, improved delivery systems, and more sophisticated screening methodologies, researchers will gain unprecedented capability to connect genetic regulation with metabolic outcomes. The experimental approaches outlined provide a foundation for advancing both basic understanding of metabolic networks and developing optimized systems for bioproduction and therapeutic intervention.

Implementing CRISPRi Screens: From Library Design to High-Throughput Applications

The precise regulation of multiple genes is fundamental to metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, enabling the redirection of metabolic flux toward desired compounds in engineered microorganisms [25]. Before the advent of modern CRISPR tools, researchers relied on sequential gene knockouts or RNA interference (RNAi), which were often time-consuming and labor-intensive for targeting multiple genes [26]. The development of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has revolutionized this field by providing a programmable and efficient platform for simultaneous multi-gene repression [25] [27].

Two primary strategies have emerged for implementing multi-gene CRISPRi: sgRNA arrays and orthogonal inducible promoters. sgRNA arrays enable the simultaneous expression of multiple guide RNAs from a single construct, allowing coordinated repression of several targets [27] [28]. Alternatively, orthogonal inducible promoter systems permit independent control of individual sgRNAs through different small-molecule inducers, facilitating tunable and combinatorial regulation [25]. Both approaches have demonstrated significant success in optimizing metabolic pathways for biofuel production [29] [30], pharmaceutical precursors [25], and other valuable compounds.

This article explores the technical implementation, applications, and protocol development for both strategies within the context of CRISPRi screening for metabolic pathway optimization. We provide detailed methodologies and resource guides to assist researchers in selecting and implementing the most appropriate multi-gene regulation strategy for their specific metabolic engineering objectives.

Fundamental Principles and Design Considerations

sgRNA arrays consist of multiple guide RNA sequences transcribed as a single unit from a common promoter, typically separated by cleavable spacer sequences [27]. This approach enables simultaneous repression of several genes through expression of a polycistronic sgRNA transcript that is processed into individual functional guides. The compact nature of sgRNA arrays makes them particularly valuable when coordinated repression of multiple pathway genes is desired.

A significant advantage of sgRNA arrays is their compatibility with high-throughput screening applications. Arrayed CRISPR libraries containing thousands of sgRNA expression plasmids enable genome-wide perturbation studies [28]. For instance, Reis et al. developed a system employing extra-long sgRNA arrays containing three independently targetable sgRNA moieties within a single nonrepetitive structure [27]. When designing sgRNA arrays, careful attention must be paid to avoiding sequence repetitiveness that could trigger homologous recombination, potentially solved by using different tracrRNA variants for each sgRNA [28].

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and experimental workflow for implementing multi-gene regulation using either sgRNA arrays or orthogonal inducible promoters:

Key Applications in Metabolic Engineering

sgRNA arrays have demonstrated remarkable success in various metabolic engineering applications. In Pseudomonas putida, predictive CRISPR-mediated gene downregulation identified optimal gene targets for enhanced production of sustainable aviation fuel precursors [29]. Similarly, in Escherichia coli, simultaneous inhibition of adhE, ldhA, and fabH using sgRNA arrays significantly enhanced isopentyl glycol production, achieving 12.4 ± 1.3 g/L titers during fed-batch cultivation [25].

In brewing yeast, separate inhibition of four candidate genes identified three highly efficient targets (TYR1, AAT2, and ALD3). Construction of an sgRNA array for simultaneous inhibition of these targets increased 2-phenylethanol production by 1.89-fold [25]. These examples highlight how sgRNA arrays enable systematic identification of optimal gene repression combinations for metabolic pathway optimization.

System Architecture and Components

Orthogonal inducible promoter systems utilize distinct regulatory elements that respond to different small-molecule inducers to control individual sgRNA expression [25]. This approach enables combinatorial control over multiple genes without constructing numerous individual sgRNA plasmids. A well-designed orthogonal system features promoters with low background leakage, high dynamic range, and minimal cross-talk between inducers [25].

A recent study developed a combinatorial repression system for E. coli using three optimized inducible promoters: PlacO1, PLtetO−1, and ParaBAD [25]. Each promoter drives expression of a different sgRNA targeting specific metabolic genes. By adding different inducer combinations (IPTG, aTc, and arabinose), researchers can rapidly test various repression combinations, significantly reducing construction time compared to traditional sgRNA array approaches.

Quantitative Performance of Promoter Systems

Table 1: Characteristics of Orthogonal Inducible Promoters for Multi-Gene Regulation

| Promoter | Inducer | Inducer Concentration | Leakage Level | Dynamic Range | Orthogonality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PlacO1 | IPTG | 0.1-1 mM | Low | ~200-fold | High |

| PLtetO−1 | aTc | 10-100 ng/mL | Very Low | ~500-fold | High |

| ParaBAD | Arabinose | 0.01-0.2% | Moderate | ~100-fold | Moderate |

| PLlac0-1 | IPTG | 0.01-1 mM | Low | ~150-fold | High |

Implementation Advantages for Metabolic Engineering

The principal advantage of orthogonal inducible promoters lies in their ability to facilitate combinatorial testing without constructing numerous plasmids. In one application, researchers optimized N-acetylneuraminic acid (NeuAc) biosynthesis in E. coli by testing various inhibition combinations of pta, ptsI, and pykA genes [25]. This approach identified an optimal repression pattern that resulted in a 2.4-fold increase in NeuAc yield compared to the control strain [25].

This system enables fine-tuning of metabolic flux by adjusting inducer concentrations to modulate repression levels of different pathway genes. This tunability is particularly valuable for balancing metabolic pathways where either insufficient or excessive repression of specific enzymes could limit overall flux [25]. The ability to independently control multiple genes through simple inducer additions makes this approach highly adaptable for rapid optimization cycles in metabolic engineering.

Comparative Analysis of Strategies

Technical Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Gene Regulation Strategies

| Parameter | sgRNA Arrays | Orthogonal Inducible Promoters |

|---|---|---|

| Construction Time | Weeks for multiple combinations | Days once base system established |

| Tunability | Limited (fixed ratios) | High (independent tuning via inducers) |

| Repression Kinetics | Coordinated | Independent temporal control |

| Pathway Balancing Capability | Moderate | High |

| Library Scale Compatibility | Excellent for large screens | Moderate (limited by orthogonal promoters) |

| Metabolic Application Examples | Isopentyl glycol, 2-phenylethanol production | N-acetylneuraminic acid optimization |

| Maximum Reported Yield Improvement | 5.76-fold (dicinnamoylmethane) | 2.4-fold (NeuAc) |

Selection Guidelines for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

The choice between sgRNA arrays and orthogonal inducible promoters depends on specific metabolic engineering goals and experimental constraints. sgRNA arrays are preferable for large-scale screening applications targeting many genes, such as genome-wide identification of essential genes or pathway bottlenecks [28] [16]. Their compact nature enables efficient packaging of multiple guides, making them ideal for pooled screening formats [26].

Orthogonal inducible promoters excel in applications requiring fine-tuning of metabolic flux through precise, adjustable control of individual pathway genes [25]. This approach is particularly valuable when optimizing complex pathways where the optimal repression level for each gene must be determined empirically. The ability to test different repression combinations through simple inducer additions significantly accelerates the optimization cycle time compared to constructing individual plasmids for each combination [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of Multi-sgRNA Arrays Using Modified Golden Gate Assembly

This protocol describes a rapid method for constructing sgRNA expression plasmids, specifically the p3gRNA-LTA vector containing three distinct sgRNA insertion sites [25].

Reagents and Equipment

- Vector backbone (p3gRNA-LTA with spectinomycin resistance)

- Type IIS restriction endonucleases (BbsI, BsaI, SapI)

- T4 DNA ligase, T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK)

- Complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides for sgRNA sequences

- Chemically competent E. coli cells

- LB agar plates with spectinomycin (25 µg/mL)

- PCR reagents and sequencing primers

Step-by-Step Procedure

sgRNA Fragment Preparation:

- Design complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides for each sgRNA target sequence with appropriate overhangs (see Table S3 in reference [25]).

- Anneal oligonucleotides by mixing equimolar amounts in 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer, heating to 95°C for 5 minutes, and slowly cooling to room temperature.

Sequential Golden Gate Assembly:

First sgRNA insertion:

- Set up 20 µL reaction containing: 0.5 µL first sgRNA fragment, 1 µg p3gRNA-LTA vector, 1 µL appropriate Type IIS restriction enzyme, 0.5 µL T4 DNA ligase, 0.5 µL T4 PNK, 2 µL T4 DNA ligase buffer.

- Cycle between 37°C (5 minutes) and 25°C (15 minutes) for 10 cycles.

Second sgRNA insertion:

- Add to the reaction: 1 µL second sgRNA fragment, 1 µL second Type IIS restriction enzyme, 0.5 µL T4 DNA ligase, 0.5 µL T4 PNK, 2 µL T4 DNA ligase buffer, 16 µL ddH2O.

- Repeat cycling as in previous step.

Third sgRNA insertion:

- Add to the reaction: 1 µL third sgRNA fragment, 1 µL third Type IIS restriction enzyme, 0.5 µL T4 DNA ligase, 0.5 µL T4 PNK, 2 µL T4 DNA ligase buffer, 16 µL ddH2O.

- Repeat cycling as in previous step.

Transformation and Verification:

- Transform entire ligation product into competent E. coli cells.

- Plate on LB agar containing spectinomycin (25 µg/mL).

- Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Screen colonies by sequencing to confirm correct sgRNA insertions.

Critical Notes

- Use distinct Type IIS restriction enzymes for each insertion site to maintain directionality.

- Verify sgRNA sequences completely after each construction step.

- The modified one-step ligation method reduces handling time compared to traditional cloning.

Protocol 2: Combinatorial Repression Using Orthogonal Inducible Promoters

This protocol enables rapid testing of different gene repression combinations using a single plasmid with three sgRNAs under control of different inducible promoters [25].

Reagents and Equipment

- Engineered E. coli strain carrying p3gRNA-LTA with sgRNAs targeting genes of interest

- dCas9 expression plasmid (compatible antibiotic resistance)

- Inducers: IPTG, aTc, arabinose

- MTB medium (12 g/L tryptone, 24 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl)

- Appropriate antibiotics

- Microplate reader for fluorescence/OD600 measurement

Step-by-Step Procedure

Strain Preparation:

- Transform the p3gRNA-LTA plasmid (containing sgRNAs under PlacO1, PLtetO−1, and ParaBAD promoters) and dCas9 expression plasmid into production host.

- Select on appropriate antibiotic plates.

Combinatorial Induction Testing:

- Inoculate 2 mL MTB medium in 24-well plates with 2% overnight culture.

- Add inducers according to desired repression pattern (see Table S4 in reference [25]):

- IPTG (0.1-1 mM) for PlacO1-driven sgRNA

- aTc (10-100 ng/mL) for PLtetO−1-driven sgRNA

- Arabinose (0.01-0.2%) for ParaBAD-driven sgRNA

- Include control wells without inducers.

Fermentation and Analysis:

- Incubate plates at 37°C with high-speed shaking for 18-24 hours.

- Monitor OD600 and product formation (e.g., fluorescence for reporter genes, HPLC for metabolites).

- For NeuAc production, specific analytical methods would include:

- HPLC analysis of culture supernatants

- Cell harvesting at mid-log and stationary phases for yield quantification

Optimal Combination Identification:

- Compare product yields across different inducer combinations.

- Select combination showing highest yield improvement.

- Validate optimal combination in larger-scale bioreactors.

Critical Notes

- Optimize inducer concentrations for each specific host strain and target gene.

- Include controls with single, double, and no inducer conditions to assess individual and synergistic effects.

- Monitor cell growth to ensure repression does not cause significant growth defects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Gene Regulation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmids | p3gRNA-LTA, pJMP1189, Mobile-CRISPRi vectors [25] [27] | sgRNA expression and dCas9 delivery | Multiple sgRNA sites, inducible systems, modular design |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | BbsI, BsaI, SapI [25] | Golden Gate Assembly | Recognition site outside target sequence, directional cloning |

| Inducers | IPTG, aTc, Arabinose [25] | Control of orthogonal promoters | Low cross-reactivity, tunable response, high dynamic range |

| Competent Cells | E. coli DH5α, BW25113, MG1655 [25] | Plasmid propagation and engineering | High transformation efficiency, recA-deficient for stability |

| Selection Antibiotics | Spectinomycin, Ampicillin, Kanamycin [25] | Strain and plasmid selection | Different modes of action for combinatorial selection |

| Library Design Tools | CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP, CRISPR Library Designer [31] | sgRNA design and off-target prediction | Genome-wide scanning, efficiency scoring, specificity analysis |

Application Notes for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Pathway Balancing for N-Acetylneuraminic Acid Production

The orthogonal inducible promoter system was successfully applied to optimize NeuAc biosynthesis in E. coli [25]. The experimental workflow for this application is detailed below:

Implementation of this approach identified optimal combinatorial inhibition of pta, ptsI, and pykA genes, resulting in a 2.4-fold increase in NeuAc yield compared to control strains [25]. The orthogonal promoter system enabled testing of multiple repression combinations without constructing numerous individual plasmids, significantly accelerating the optimization process.

Advanced sgRNA Array Designs for Enhanced Efficiency

Recent advances in sgRNA array technology include the development of quadruple-guide RNA (qgRNA) systems, where four distinct sgRNAs target the same gene, each driven by different RNA polymerase III promoters (human U6, mouse U6, human H1, and human 7SK) [28]. This approach demonstrates that multiple sgRNAs targeting a single gene can achieve more potent repression than individual guides.

The ALPA (Automated Liquid-Phase Assembly) cloning method enables high-throughput construction of these qgRNA plasmids without traditional colony picking [28]. This system achieved 75-99% deletion efficiency and 76-92% silencing efficacy in validation experiments, demonstrating the potential for highly efficient multi-gene regulation using advanced array designs [28].

Both sgRNA arrays and orthogonal inducible promoters offer powerful, complementary approaches for multi-gene regulation in metabolic engineering. sgRNA arrays provide an efficient solution for coordinated repression of multiple genes, particularly valuable in large-scale screening applications [28] [16]. Orthogonal inducible promoters enable combinatorial testing and fine-tuning of metabolic pathways without constructing numerous individual plasmids [25].

Future developments in multi-gene regulation will likely focus on expanding the toolbox of orthogonal systems, improving the efficiency and specificity of sgRNA designs, and integrating machine learning approaches to predict optimal repression patterns [30]. The continued refinement of these technologies will further enhance our ability to engineer microbial cell factories for sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other valuable chemicals.

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) has revolutionized functional genomics by enabling programmable gene repression. However, traditional CRISPRi approaches that completely silence gene expression are insufficient for optimizing metabolic pathways, where precise control over flux redistribution is required. Binary on/off repression often fails because maximal product synthesis typically requires intermediate enzyme levels that balance growth and production, avoiding the accumulation of toxic intermediates [32] [33].

The emergence of mismatch sgRNA technology addresses this limitation by enabling titratable gene repression. By introducing specific base mismatches between the sgRNA and its DNA target, researchers can predictably tune knockdown efficiency across a wide continuum. This approach allows for systematic exploration of expression-fitness relationships and optimal pathway balancing without requiring labor-intensive cloning of multiple genetic constructs [34] [32]. This Application Note details the implementation of mismatch sgRNA libraries for fine-tuning gene expression in metabolic pathway optimization.

Core Mechanism: How Mismatch sgRNAs Enable Titratable Repression

Fundamental Principles

Mismatch sgRNA technology leverages the predictable reduction in CRISPRi efficacy when base-pairing imperfections exist between the sgRNA spacer sequence and the target DNA protospacer. Unlike CRISPR nuclease applications where off-target effects are undesirable, this system intentionally designs mismatches to generate a spectrum of repression efficiencies from a single target sequence [34].

The binding efficiency of the dCas9-sgRNA complex to DNA is primarily determined by the energy of RNA-DNA hybridization. Mismatches, particularly in the seed region proximal to the PAM sequence, destabilize this interaction, reducing the dwell time of dCas9 at the target site and consequently lowering repression efficiency. This relationship between mismatch characteristics and repression efficacy forms the basis for predictable titratable control [35].

Key Determinants of Mismatch Efficacy

The impact of a mismatch on repression efficiency depends on three primary factors:

- Mismatch Position: PAM-proximal positions (particularly in the seed region 1-8) have dramatically greater effects on efficacy than PAM-distal mismatches [34] [35].

- Base Substitution Type: Mismatches that cause greater thermodynamic destabilization (e.g., G-A, C-T) typically result in more significant reductions in repression efficacy [34].

- Mismatch Combination: Multiple mismatches can compound to further reduce repression or create a more gradual titration profile [32].

Table 1: Impact of Single Mismatch Parameters on CRISPRi Efficacy

| Parameter | Effect on Efficacy | Experimental Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM-proximal (Seed) Mismatch | Severe reduction | 5-95% of full activity | Mismatches at positions 3-8 most impactful [34] |

| PAM-distal Mismatch | Mild to moderate reduction | 30-100% of full activity | Positions 18-20 show minimal efficacy reduction [34] |

| Mismatch Type | Varies by base change | 10-90% of full activity | Correlates with ΔΔG of RNA-DNA hybridization [34] |

| Double Mismatches | Compounded reduction | 0-80% of full activity | Enables nearly full range of repression [32] |

System Comparison: Bacterial vs. Mammalian CRISPRi

The performance of mismatch sgRNAs differs significantly between bacterial and mammalian CRISPRi systems, primarily due to their distinct repression mechanisms. In bacteria, dCas9 functions mainly by sterically blocking RNA polymerase elongation during transcription, while in mammalian systems, dCas9 is typically fused to repressive domains like KRAB that recruit chromatin-modifying complexes to promoters [34].

These mechanistic differences result in important practical considerations. Bacterial CRISPRi tolerates mismatches better, particularly in the seed region, where mammalian systems experience nearly complete loss of activity. Additionally, mammalian systems generally show steeper efficacy drop-offs with increasing mismatches and greater position-dependent effects [34].

Table 2: Comparison of Mismatch sgRNA Performance Across Systems

| Characteristic | Bacterial CRISPRi | Mammalian CRISPRi (dCas9-KRAB) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Transcriptional elongation blocking [34] | Chromatin modification & promoter occlusion [34] |

| Seed Region Mismatch Tolerance | Moderate (retains some activity) [34] | Low (near-complete activity loss) [34] |

| Efficacy Range with Mismatches | Full continuum (0-100%) [34] [32] | Limited without seed matches [34] |

| Optimal Mismatch Strategy | Single/double in seed region [32] | Multiple in distal region or truncated guides [34] |

| Correlation Between Systems | R² = 0.61 for mismatch effects [34] | N/A |

Experimental Design and Implementation

Library Design Considerations

Effective mismatch sgRNA library design requires strategic planning to ensure coverage of the desired repression range while maintaining library compactness. For comprehensive titration, researchers have successfully employed different approaches:

- Full Mismatch Coverage: Designing all possible single mismatch variants for each target sgRNA generates 60 sgRNAs per target, suitable for detailed fitness landscape mapping [34].

- Focused Dual Mismatch Libraries: Incorporating two consecutive random mismatches in the sgRNA seed region creates a compact 16-variant library per target that still covers a wide repression range [32].

- Empirically Informed Design: Using predictive models based on mismatch position, type, and local GC content to select a minimal set of mismatched sgRNAs that provide evenly spaced repression levels [34].

The choice between these approaches depends on the screening scale, desired resolution, and available resources. For most metabolic engineering applications, the focused dual mismatch approach provides an excellent balance between comprehensiveness and practical implementation [32].

Protocol: Implementation of a Titratable CRISPRi Screen for Metabolic Optimization

Phase 1: Library Design and Construction

Target Selection and Validation:

Mismatch Library Synthesis:

- For each validated target, design a set of sgRNA variants with predefined mismatches

- For bacterial systems: Focus on positions 3-8 with 1-2 mismatches [32]

- For mammalian systems: Focus on positions 12-18 with 1-3 mismatches [34]

- Include perfectly matched and non-targeting controls

- Synthesize oligo pool containing all sgRNA variants

Library Cloning and Validation:

Phase 2: Screening Implementation

Cell Transformation and Culturing:

- Transform library into your working strain expressing dCas9

- For bacterial systems: Use conjugative transfer if electroporation efficiency is low [37]

- Ensure ≥500x library coverage to maintain representation

- Culture under selective conditions for stable maintenance

Phenotypic Screening:

Sequencing and Hit Identification:

- Harvest cells at appropriate screening endpoint

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify sgRNA regions for sequencing

- Map sequencing reads to library design to calculate enrichment/depletion [36]

Protocol: BATCH Screening for Metabolic Production Enhancement

The Biosensor-Assisted Titratable CRISPRi High-Throughput (BATCH) screening system combines mismatch CRISPRi with biosensor detection for efficient production strain development [32]:

Biosensor Implementation:

- Select or engineer a transcription factor-based biosensor responsive to your target metabolite

- Clone biosensor controlling a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., eGFP)

- Validate biosensor dynamic range and specificity

Mismatch Library Design:

- Design doubly mismatched sgRNA pools targeting 15-25 pathway genes

- Include 2-3 independent targets per gene with 16 mismatch variants each

- Clone library into appropriate expression vector

High-Throughput Screening:

- Transform library into production strain containing biosensor and dCas9

- Sort populations based on fluorescence intensity using FACS

- Collect multiple bins representing different production levels

- Sequence sgRNAs from each bin to identify optimal knockdown combinations [32]

Validation:

- Reconstruct top hits as individual strains

- Ferment and measure product titers to confirm improvements

Applications in Metabolic Pathway Optimization

Case Study: p-Coumaric Acid Production in E. coli

Implementation of mismatch CRISPRi screening for p-coumaric acid optimization demonstrates the power of this approach:

- Target Selection: Library targeted 20 genes in central carbon metabolism and aromatic amino acid pathways

- Mismatch Design: Employed doubly mismatched sgRNAs with two consecutive random mismatches in the seed region

- Screening: Used a PadR-based p-coumaric acid biosensor with eGFP reporter for FACS sorting

- Results: Identified optimal knockdown levels for pfkA and ptsI, increasing titer by 40.6% to 1308.6 mg/L from glycerol in shake flasks [32]

Case Study: Butyrate Production Enhancement

Similar approaches successfully improved butyrate production:

- Library: Targeted sucA and ldhA with mismatch sgRNA variants

- Screening: Utilized HpdR-based butyrate biosensor for high-throughput screening

- Results: Achieved 19.0% and 25.2% titer increases with sucA and ldhA targeting, respectively [32]

Expression-Fitness Landscape Mapping

Beyond direct production enhancement, mismatch CRISPRi enables fundamental studies of expression-fitness relationships:

- Comprehensive Profiling: Used 90 mismatched sgRNAs per essential gene in E. coli and B. subtilis

- Relationship Diversity: Revealed diverse expression-fitness relationships ranging from linear to bimodal

- Evolutionary Conservation: Found remarkable conservation of expression-fitness relationships between homologs despite ~2 billion years of evolutionary separation [34]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Mismatch CRISPRi Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effectors | CRISPRi repression machinery | Zim3-dCas9 (optimal balance of efficacy/specificity) [38]; dCas9-KRAB [34] |

| sgRNA Scaffold | dCas9 binding and localization | Standard S. pyogenes scaffold with modified stem loops for enhanced stability [33] |

| Library Vectors | sgRNA expression and delivery | Lentiviral (mammalian); Mobilizable plasmids (bacterial) [36] [37] |

| Biosensor Systems | High-throughput production detection | PadR-based (p-coumaric acid); HpdR-based (butyrate) [32] |

| Prediction Models | Mismatch efficacy forecasting | Linear models incorporating position, substitution type, GC% [34] |

| Analysis Tools | sgRNA sequencing data processing | Custom pipelines for enrichment calculation; MAGeCK [36] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Low Repression Dynamic Range:

- Verify dCas9 expression levels and functionality with control sgRNAs

- Test alternative target sites within the gene of interest

- For mammalian systems, ensure targeting to promoter regions rather than coding sequences [38] [33]

Poor Library Representation:

- Maintain ≥500x coverage throughout screening

- Use high-efficiency transformation methods (electroporation/conjugation)

- Minimize bottleneck steps during cell passaging [37]

Inconsistent Mismatch Effects:

- Validate model predictions with small-scale tests

- Consider local chromatin environment or DNA accessibility issues

- Test multiple target sites per gene to account for position effects [34] [33]

Mismatch sgRNA libraries represent a powerful methodology for achieving precise, titratable control of gene expression in metabolic pathway optimization. By enabling systematic exploration of expression-fitness landscapes and optimal flux redistribution, this technology moves beyond traditional binary perturbation approaches. The combination of mismatch CRISPRi with biosensor-enabled high-throughput screening creates an exceptionally powerful platform for strain development, as demonstrated by successful applications in diverse bacterial systems for biochemical production [34] [32].

The continued refinement of mismatch efficacy prediction models and the development of more compact, highly active library designs will further enhance the accessibility and implementation of this technology across diverse host organisms and application areas [38] [34].

Biosensor-Assisted High-Throughput Screening (BATCH) for Rapid Phenotype Identification