Choosing the Right Goal: A Comprehensive Guide to Objective Functions in Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, but its predictive power is critically dependent on the selection of an appropriate biological objective function.

Choosing the Right Goal: A Comprehensive Guide to Objective Functions in Flux Balance Analysis

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, but its predictive power is critically dependent on the selection of an appropriate biological objective function. This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and scientists on comparing, selecting, and validating objective functions for FBA. We explore foundational concepts, from the basic principle of assuming an evolutionary metabolic goal to the practical application of different functions like biomass or ATP maximization. The guide then delves into advanced methodologies, including the integration of proteomic data and novel frameworks like TIObjFind for inferring context-specific objectives. Furthermore, we address common challenges such as model infeasibility and detail robust techniques for validating and comparing FBA predictions against experimental data. By synthesizing current research and best practices, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy and biological relevance of FBA applications in metabolic engineering and drug development.

What is an Objective Function? The Core Principle of FBA

In systems biology, constraint-based metabolic modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), serves as a powerful computational framework for predicting cellular behavior by leveraging the stoichiometry of metabolic networks. The core principle of FBA involves determining a flux distribution that optimizes a specific cellular objective, mathematically represented as the objective function. This function is a quantitative representation of a presumed metabolic goal, and its selection is arguably the most critical assumption in the model, as it ultimately dictates the predicted phenotypic state. The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that cellular objectives are not universal; they vary significantly across organisms, tissue types, and environmental contexts. While rapidly proliferating cells such as microbes in nutrient-rich conditions or aggressive cancer cells may prioritize biomass maximization, this assumption becomes biologically inaccurate for many other cell types. Specialized mammalian cells, including neurons, muscle cells, and quiescent adult cells, often prioritize objectives beyond growth, such as tissue maintenance, energy dynamics management, and the execution of specialized physiological functions [1].

The selection of an appropriate objective function is therefore not merely a technical step but a fundamental biological assumption that requires careful justification. An inappropriate choice can lead to model predictions that diverge significantly from experimental observations, limiting the model's utility in metabolic engineering, drug discovery, and understanding disease mechanisms. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the predominant objective functions used in FBA, evaluating their theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and experimental validation protocols. By framing this discussion within the context of a broader thesis on comparing objective functions, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to make informed decisions that enhance the biological relevance and predictive power of their metabolic models.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis of Objective Functions

The Biological Basis for Metabolic Objectives

Cells operate under constraints of limited resources and must make trade-offs between competing metabolic goals, a concept well-studied in evolutionary biology [1]. For instance, a cell cannot simultaneously maximize its growth rate, invest heavily in stress resistance mechanisms, and maintain high motility. This leads to the emergence of Pareto optimality, where improving one objective necessitates compromising another. The Y-model is a classic conceptual framework that depicts two phenotypes competing for a finite, shared resource pool [1]. In microbiology, studies of Escherichia coli have demonstrated a clear trade-off where the expression of growth genes is active in the exponential phase, while survival genes become dominant in the stationary phase [1]. Similarly, in cancer biology, tumors exhibit spatial and temporal trade-offs; cells in oxygen-rich niches may optimize for proliferation, whereas hypoxic regions select for phenotypes optimized for survival [1]. These observations confirm that the assumption of a single, static objective function is an oversimplification. Instead, cells exhibit a repertoire of context-dependent metabolic objectives.

Comparative Analysis of Common Objective Functions

The table below provides a structured comparison of the most commonly used objective functions in FBA, summarizing their mathematical goals, primary applications, and key limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Objective Functions in Flux Balance Analysis

| Objective Function | Mathematical Goal | Typical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Maximize the flux through a pseudo-reaction representing the synthesis of all biomass constituents [2]. | - Microbes in bioreactors [2].- Rapidly proliferating cancer cells [1].- Standard condition for growth prediction. | Biologically inaccurate for non-proliferating or specialized cells [1]. Oversimplifies complex cellular priorities. |

| ATP Maximization | Maximize the flux of ATP production (or the net yield of ATP-generating reactions) [2]. | - Simulating energy-intensive processes (e.g., muscle contraction [1]).- Investigating ATP-dependent phenotypes. | Can predict unrealistically high ATP cycling and may not correlate with growth or survival in all conditions [2]. |

| Parsimonious Enzyme Usage (pFBA) | First, maximize growth/biomass. Second, minimize the total sum of all metabolic fluxes, achieving optimal growth with minimal enzyme investment [2]. | - Improving flux predictions by incorporating enzyme cost constraints [2].- Yeast replicative aging studies [2]. | Relies on a pre-defined primary objective (e.g., growth). The biological rationale for global flux minimization is debated. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Simultaneously optimize two or more objectives (e.g., growth AND ATP production) to find a set of Pareto-optimal solutions [2]. | - Modeling cellular trade-offs [1].- Studying complex phenotypes like stress response. | Computationally intensive. Requires careful interpretation of a solution space rather than a single flux distribution. |

The choice between these objectives has demonstrable effects on model predictions. For example, a systematic study on yeast replicative aging found that while maximal growth was essential for achieving realistic lifespans, combining it with a parsimonious enzyme usage constraint or an energy cost objective improved predictions by aligning with observed respiratory activity and antioxidative processes in early life [2]. This underscores that the most appropriate objective function can be condition-dependent and must be selected and validated with care.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Metabolic Objectives

Theoretical predictions from FBA must be rigorously tested against experimental data. The following sections outline key methodologies for measuring metabolic fluxes and validating model assumptions.

Isotopically Stationary (^{13})C Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA)

(^{13})C-MFA is considered the gold standard for experimentally determining intracellular metabolic fluxes. It provides a direct, quantitative dataset for validating the flux distributions predicted by FBA under a given objective function [3].

Detailed Experimental Workflow:

- Cell Culture and Tracer Preparation: Cells are cultured in a controlled environment (e.g., a bioreactor) to maintain a metabolic steady-state, where metabolite concentrations remain constant. The growth medium is then replaced with one containing a (^{13})C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-(^{13})C] glucose). The label allows for tracking the fate of carbon atoms through the metabolic network [3].

- Reaching Isotopic Steady State: The cultivation continues until the isotopic steady state is achieved. This is the point where the (^{13})C label has been fully incorporated into the intracellular metabolite pools, and their isotopic distributions are no longer changing over time. For mammalian cells, this process can take several hours to a full day [3].

- Rapid Quenching and Metabolite Extraction: Cellular metabolism is instantaneously stopped ("quenched") by rapidly cooling the cells in cold methanol (e.g., -40°C). This is a critical step to preserve the in vivo metabolic state. Intracellular metabolites are then extracted using a mixture of methanol, water, and sometimes chloroform [3] [4].

- Analytical Measurement via LC-MS or NMR: The extracted metabolites are analyzed using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. These techniques identify metabolites and quantify their relative abundances and, crucially, their isotopologue distributions—the patterns of (^{13})C incorporation within each molecule [3] [5].

- Computational Flux Estimation: The measured isotopologue data is integrated into a stoichiometric model of the central carbon metabolism. Powerful computational software (e.g., INCA, 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX) is used to find the set of metabolic fluxes that best fits the experimental labeling data, typically via iterative least-squares regression [3] [4].

Figure 1: Workflow for isotopically stationary ¹³C-MFA.

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA)

INST-MFA is an advanced technique that overcomes a major limitation of traditional (^{13})C-MFA—the long wait for isotopic steady state. It is particularly useful for systems with slow labeling dynamics or when studying transient metabolic phenomena [3] [4].

Key Methodological Adjustments:

- Transient Sampling: Instead of waiting for isotopic equilibrium, cells are sampled multiple times at short intervals (seconds to minutes) immediately after the introduction of the (^{13})C-labeled substrate.

- Dynamic Modeling: The computational model uses a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to simulate the time-dependent evolution of isotopologue distributions in metabolite pools. The flux values are estimated by fitting the model to this time-course data [4].

- Computational Demand: While more powerful and faster experimentally, INST-MFA is computationally intensive. However, tools like the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) modeling approach and software such as INCA have significantly reduced this barrier [3].

Table 2: Core Reagents and Software for Metabolic Flux Experiments

| Category | Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Labeled Substrates | [U-(^{13})C] Glucose, (^{13})C-Glutamine | Carbon source for tracing; universally incorporated into metabolism to map flux routes [3]. |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Separates and identifies metabolites; quantifies mass isotopomer abundances with high sensitivity [3] [5]. |

| Software for Flux Estimation | INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) | Leading platform for both stationary (MFA) and non-stationary (INST-MFA) flux analysis [3] [4]. |

| Software for Flux Estimation | 13CFLUX2 / OpenFLUX | Specialized software for estimating metabolic fluxes from 13C labeling data at isotopic steady state [3] [4]. |

| Software for FBA | Cobrapy, MATLAB COBRA Toolbox | Standard toolkits for building, simulating, and analyzing constraint-based metabolic models, including FBA with various objectives [2]. |

Decision Framework and Applications in Therapeutic Development

A Framework for Selecting an Objective Function

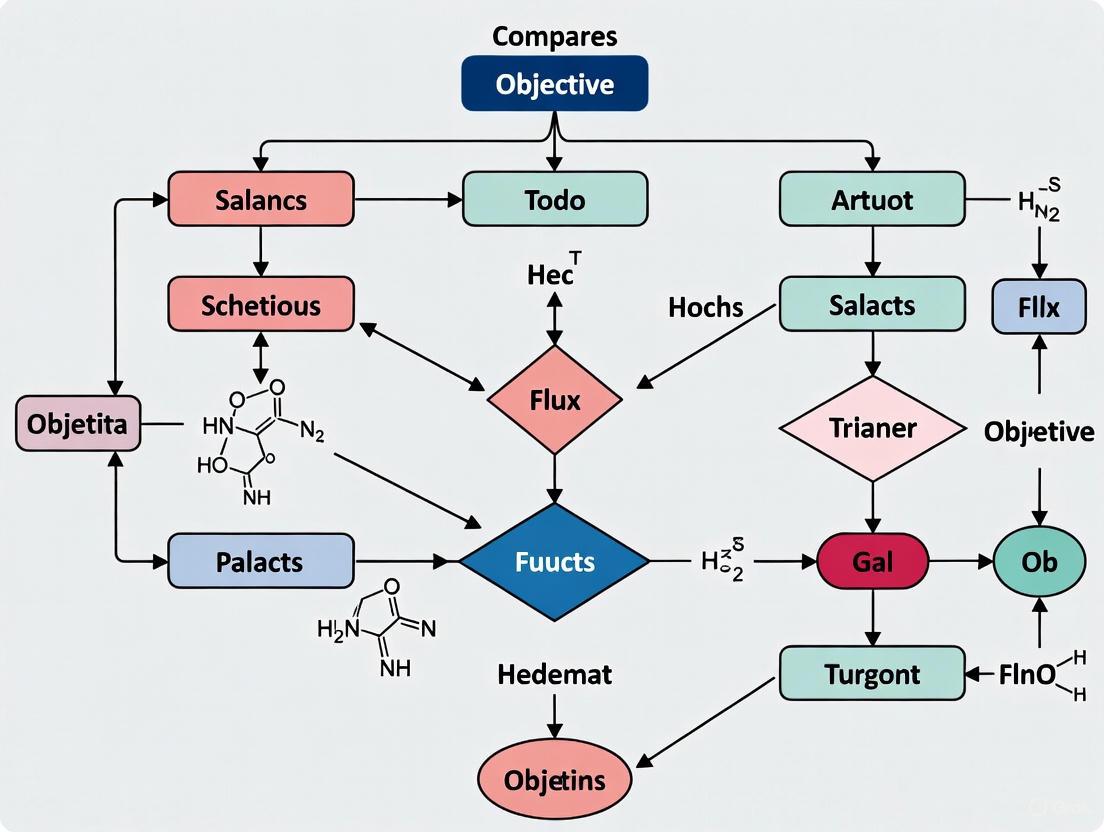

The following decision diagram provides a logical pathway for researchers to select an appropriate objective function based on their biological system and research question.

Figure 2: A decision framework for selecting an FBA objective function.

Application in Drug Discovery and Live Biotherapeutic Development

The choice of objective function directly impacts the translational success of metabolic models in biotechnology and medicine.

- Cancer Research: Tumor metabolism is highly heterogeneous. While core tumors might be modeled with biomass maximization, hypoxic, invasive regions may be better represented by objectives that prioritize ATP yield or redox balance (e.g., NADPH production) to combat oxidative stress, as suggested by the Warburg effect and its role in invasiveness [1] [5]. FBA models with context-appropriate objectives can help identify metabolic vulnerabilities for drug targeting.

- Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs): The development of LBPs—live bacteria used as drugs—relies on GEMs to predict strain functionality and host-microbe interactions. For a candidate like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, the objective might be set to maximize the production of the anti-inflammatory metabolite butyrate, rather than its own growth [6]. This model-guided approach allows for the in silico screening and design of multi-strain consortia with defined therapeutic outputs, streamlining the development process [6].

Defining the metabolic goal through an objective function is a fundamental step that bridges the gap between the topological structure of a metabolic network and the emergent phenotypic behavior of a cell. As this guide has detailed, there is no universal objective. The assumption of biomass maximization, while useful for modeling proliferative states, is often an oversimplification that fails to capture the complex priorities and trade-offs inherent in biological systems, from microbial communities to specialized human tissues. The rigorous, experimental validation of these assumptions via techniques like (^{13})C-MFA is paramount for building credible, predictive models. As the field progresses, the integration of multi-omics data and the application of more sophisticated, condition-specific objective functions will be crucial for advancing applications in metabolic engineering and drug development, ultimately leading to a more nuanced and accurate understanding of cellular metabolism.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone mathematical approach in systems biology for analyzing the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks [7]. As a constraint-based method, it predicts metabolic fluxes by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that contain all known metabolic reactions for an organism [8]. The core principle of FBA involves defining a biological objective that the metabolic network is hypothesized to optimize, then using linear programming to identify flux distributions that achieve this objective while satisfying stoichiometric and capacity constraints [7]. The selection of an appropriate objective function is paramount, as it directly determines the predicted phenotypic behavior [9].

The fundamental FBA problem is mathematically represented by the equation Sv = 0, where S is an m × n stoichiometric matrix, and v is an n-dimensional vector of metabolic fluxes [8] [7]. This equation enforces mass-balance constraints, ensuring that metabolite production equals consumption at steady state. Additional upper and lower bounds (Vi^min ≤ vi ≤ V_i^max) further constrain reaction fluxes based on physiological considerations [8]. FBA identifies an optimal flux distribution by maximizing or minimizing a linear objective function Z = c^T v, where c is a vector of weights that quantifies each reaction's contribution to the chosen cellular objective [7].

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of three principal objective functions—biomass maximization, ATP production, and metabolic task optimization—evaluating their predictive performance, experimental validation, and suitability for different research applications.

Comparative Analysis of Common Objective Functions

Biomass Maximization

Biomass maximization is the most prevalent objective function for predicting cellular growth rates and nutrient requirements [7]. It operates by defining a biomass reaction that drains essential biomass precursor metabolites—including amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and carbohydrates—from the metabolic network at stoichiometries reflecting their cellular composition [7]. The flux through this reaction is scaled to represent the exponential growth rate (μ) of the organism. Biomass maximization has proven exceptionally reliable for predicting gene essentiality and growth capabilities of model microorganisms such as Escherichia coli under various environmental conditions [8]. For example, FBA with biomass maximization as the objective accurately predicts the drop in E. coli's growth rate from 1.65 hr⁻¹ under aerobic conditions to 0.47 hr⁻¹ under anaerobic conditions [7].

ATP Production

ATP production, or maximizing the flux through ATP maintenance reactions, is often employed to simulate energy metabolism [7]. This objective function hypothesizes that metabolic networks are optimized to maximize energy (ATP) yield. While ATP production can be a relevant objective under specific energetic stress conditions, studies have demonstrated that it generally performs worse than biomass maximization in predicting microbial growth phenotypes [9]. Its primary utility lies in studies focused on cellular energetics, including investigations of ATP, NADH, or NADPH yields, and in modeling metabolic behaviors where growth is not the primary cellular focus [7].

Metabolic Task Optimization

Metabolic task optimization encompasses objective functions tailored to specific biochemical outputs, such as the production of primary or secondary metabolites, rather than growth [10] [11]. This approach is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering for predicting genetic modifications that enhance the synthesis of high-value compounds, including pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and industrial chemicals [8]. Frameworks like OptKnock utilize this principle to identify gene knockouts that couple the production of desirable metabolites with cellular growth [7]. A significant limitation of using a single, static task for optimization is its potential failure to capture the dynamic adaptive responses of metabolism to environmental changes [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Objective Functions in FBA

| Objective Function | Primary Application | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Predicting growth rates, gene essentiality, and nutrient utilization [8] [7] | High accuracy for microbial growth prediction; well-validated [8] | Less accurate for non-growth states or complex organisms [8] |

| ATP Production | Studying energy metabolism and ATP yield [7] | Relevant for energy-related phenotypes | Generally poor prediction of growth compared to biomass [9] |

| Metabolic Task Optimization | Metabolic engineering for chemical production [8] [7] | Directs flux toward specific, valuable products [7] | May not reflect native cellular objectives; can be condition-specific |

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

Rigorous comparative studies are essential to determine the most appropriate objective function for a given biological context. A 2014 review highlighted that while numerous studies have aimed to compare objective functions, their divergent methodologies, the quantity and type of experimental data used, and the classification of growth conditions have made it challenging to draw universally applicable conclusions [9]. This underscores the necessity for standardized, rigorous comparative frameworks.

The predictive accuracy of biomass maximization is well-established for E. coli, where it correctly predicts gene essentiality with high accuracy under glucose-limited aerobic conditions [8]. However, its performance declines when applied to higher-order organisms where the assumption of growth optimality may not hold [8]. Recent advancements have introduced machine learning approaches like Flux Cone Learning (FCL), which outperforms traditional FBA with biomass maximization by achieving 95% accuracy in predicting metabolic gene essentiality in E.. coli by learning the shape of the metabolic flux space without relying on a pre-defined objective function [8].

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Biomass Maximization vs. Advanced Frameworks

| Organism / Method | Objective Function | Predicted Phenotype | Performance / Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Biomass Maximization [7] | Aerobic growth rate on glucose | 1.65 hr⁻¹ (matches experimental data) [7] |

| E. coli | Biomass Maximization [8] | Metabolic gene essentiality | ~93.5% accuracy [8] |

| E. coli (FCL Framework) | Not Required [8] | Metabolic gene essentiality | 95% accuracy [8] |

| S. cerevisiae & CHO Cells | Biomass Maximization [8] | Metabolic gene essentiality | Lower accuracy than in E. coli [8] |

Advanced Frameworks for Objective Function Identification

The challenge of selecting a single, universally applicable objective function has spurred the development of sophisticated, data-driven frameworks.

The TIObjFind Framework

TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) is a novel framework that integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific metabolic objectives from experimental data [10] [11]. Its operation can be summarized in three key steps:

- It formulates an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between FBA-predicted fluxes and experimental flux data while maximizing an inferred, weighted metabolic goal [10].

- It maps the resulting FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), which provides a pathway-based interpretation of flux distributions [10].

- It applies a minimum-cut algorithm to this graph to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients quantify each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective, effectively serving as pathway-specific weights in the objective function [10].

This topology-informed approach enhances the interpretability of complex networks and successfully captures adaptive metabolic shifts, as demonstrated in case studies involving Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and a multi-species system [10] [11]. The following diagram illustrates the TIObjFind workflow.

The Flux Cone Learning Framework

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) represents a paradigm shift by circumventing the need for an explicit objective function altogether [8]. This machine learning strategy uses Monte Carlo sampling to generate random flux distributions that satisfy the stoichiometric constraints of a GEM for both wild-type and gene-deletion strains. The geometric changes in this "flux cone" resulting from gene deletions are then correlated with experimental fitness scores using a supervised learning algorithm, such as a random forest classifier [8]. FCL has demonstrated best-in-class accuracy for predicting gene essentiality across organisms of varying complexity and can be adapted to predict other phenotypes, such as small molecule production [8].

Experimental Protocols for Objective Function Comparison

A standardized protocol for comparing the predictive power of different objective functions is crucial for robust analysis. The following workflow, based on the COBRA Toolbox [7], outlines the key steps.

Step 1: Load a Metabolic Model. Begin by importing a curated genome-scale metabolic model, such as the E. coli core model, in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format into a computational environment like MATLAB using the COBRA Toolbox [7].

Step 2: Apply Physiological Constraints. Define the environmental conditions by setting lower and upper bounds on exchange reactions. For example, to simulate aerobic growth on glucose, set the glucose uptake rate to a realistic value (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr) and allow high oxygen uptake [7].

Step 3: Define the Objective Function. Specify the reaction(s) to be optimized. This is typically done by assigning a weight of 1 to the target reaction (e.g., the biomass reaction) and 0 to all others in the objective vector c [7].

Step 4: Perform Flux Balance Analysis. Solve the linear programming problem max c^T v subject to Sv = 0 and lb ≤ v ≤ ub using a solver like optimizeCbModel in the COBRA Toolbox to obtain a predicted flux distribution [7].

Step 5: Simulate Genetic Perturbations. Test the model's predictive power by simulating gene knockouts. This is achieved by using a Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) map to set the flux bounds of reactions associated with the deleted gene to zero [8].

Step 6: Validate with Experimental Data. Compare the FBA predictions (e.g., growth/no-growth phenotype, secretion product formation) against experimental datasets, such as gene essentiality screens or measured metabolite secretion rates [9] [8]. Quantitative metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall should be used for formal comparison [8].

Table 3: Key Resources for FBA and Objective Function Research

| Resource Type | Example(s) | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc [10] [11] | Foundational databases for pathway, genomic, and reaction information used in network reconstruction. |

| Software Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox [7], FlexFlux [10] [11] | Provide implemented algorithms for performing FBA, constraint-based modeling, and related analyses. |

| Modeling Frameworks | TIObjFind [10] [11], Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [8], ObjFind [10] [11] | Advanced computational frameworks for identifying objective functions or predicting phenotypes without predefined objectives. |

| Simulation Algorithms | Boykov-Kolmogorov Algorithm [10], Monte Carlo Sampler [8], Linear Programming Solvers [7] | Core computational engines for solving graph-theoretic problems, sampling flux distributions, and optimizing objective functions. |

| Model Organisms | Escherichia coli [8] [7], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [8], Clostridium acetobutylicum [10] [11] | Well-characterized organisms with curated GEMs used for method development and validation. |

Beyond Biomass: Advanced and Context-Specific Objective Functions

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic flux distributions in cellular networks. A fundamental challenge in FBA is selecting an appropriate biological objective function—the presumed goal driving cellular metabolism, such as biomass maximization or metabolite production [11] [10]. Traditional FBA often relies on single, static objectives that may not accurately capture the dynamic and adaptive nature of cellular metabolism under varying environmental conditions or disease states [11] [10].

The integration of proteomic and transcriptomic data offers a transformative path toward defining more accurate, context-specific objective functions. This multi-omics approach moves beyond simplistic assumptions by incorporating direct measurements of the proteome—the ultimate effectors of cellular function—and the transcriptome, which provides crucial information on regulatory dynamics [12] [13] [14]. This review compares how proteomics and transcriptomics, both independently and integrated, can be leveraged to infer biological objective functions, thereby enhancing the predictive power of metabolic models in both basic research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Omics Data for Defining Metabolic Objectives

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and limitations of transcriptomics and proteomics in the context of defining objective functions for FBA.

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptomic and Proteomic Approaches for Defining Metabolic Objectives

| Feature | Transcriptomics | Proteomics |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Measurement | mRNA expression levels [13] | Protein abundance, structure, and post-translational modifications [12] [15] |

| Primary Data Type | RNA-seq data (e.g., FPKM values) [13] | Mass spectrometry data (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ, label-free quantification) [13] [16] |

| Functional Relevance to FBA | Indirect indicator of metabolic enzyme potential; subject to post-transcriptional regulation [12] [14] | Direct measurement of enzyme abundance; closer link to actual metabolic reaction rates [12] [15] |

| Key Advantage | High-throughput; well-established computational tools for analysis [17] | Directly reflects functional cellular state; identifies active pathways and protein complexes [12] [18] |

| Main Limitation | Poor correlation with protein levels for many genes (~40%) [12] [14] | Technical challenges with dynamic range and low-abundance protein detection [12] [15] |

| Use in Objective Function Identification | Can constrain model by suggesting which reactions are up/down-regulated [11] | Can be used to weight reaction fluxes or define pathway-specific coefficients of importance [11] [10] |

Computational Frameworks for Integrating Multi-Omics Data into FBA

The TIObjFind Framework

The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework represents a significant advancement by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data [11] [10]. This framework introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which quantify each metabolic reaction's contribution to a cellular objective function, thereby aligning FBA predictions with experimental flux data [11] [10]. The implementation involves three critical steps:

- Reformulating objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes.

- Mapping FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) for pathway-based interpretation.

- Applying a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to extract critical pathways and compute CoIs, which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization [11] [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Frameworks for Data-Driven Objective Function Identification

| Framework | Core Methodology | Omics Data Integration | Key Output | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind [11] [10] | Combines FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) and graph theory | Utilizes experimental flux data, potentially derived from multi-omics studies | Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions | Topology-informed; reduces overfitting by focusing on key pathways |

| ObjFind [10] | Extension of FBA that maximizes a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing deviation from data | Can incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data to inform flux constraints | Weighting coefficients for all metabolic reactions | Directly aligns model predictions with experimental data |

| NEXT-FBA [19] | Hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven approach | Integrates various omics data types to improve intracellular flux predictions | Improved intracellular flux distributions | Leverages machine learning and data-driven constraints |

Multi-Omics Integration and Clustering Considerations

Integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data meaningfully requires specialized computational approaches. A comprehensive benchmark study evaluating 28 clustering algorithms on 10 paired transcriptomic and proteomic datasets revealed that methods like scAIDE, scDCC, and FlowSOM consistently performed well across both omics types [17]. This is crucial because single-cell proteomic data often exhibit markedly different data distributions and feature dimensionalities compared to transcriptomic data [17]. For multi-omics integration, methods such as moETM, sciPENN, and totalVI can create a unified representation of transcriptomic and proteomic data, providing a more comprehensive foundation for informing metabolic models [17].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration in Metabolic Modeling

Integrated Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analysis Workflow

The following protocol, adapted from epilepsy research, provides a robust methodology for generating paired omics data suitable for informing metabolic models [13]:

Sample Collection and Preparation: Obtain biological samples (e.g., brain tissue, microbial cultures) from both experimental and control conditions. For tissue samples, immediate stabilization using RNA/protein stabilization reagents is critical. Samples are typically flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C [13].

Transcriptomic Profiling (RNA-seq):

- RNA Extraction: Use TRIzol or similar reagents to isolate total RNA. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8 recommended).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Fragment mRNA to 200-300 bp. Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers. Perform paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform [13].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Align sequences to a reference genome. Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) using tools like DESeq2, with thresholds of |log2FoldChange| > 1 and p-value < 0.05. Perform functional enrichment analysis (GO and KEGG) [13].

Proteomic Profiling (TMT/iTRAQ):

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Lyse samples in SDS-containing buffer. Digest proteins with trypsin after reduction and alkylation.

- Peptide Labeling: Label peptides from each condition with different Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) or iTRAQ reagents.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate labeled peptides using liquid chromatography (Easy nLC 1200) and analyze by tandem mass spectrometry (Q-Exactive).

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs) using Proteome Discoverer or similar software, with thresholds of |log2FoldChange| > 1.2 and p-value < 0.05. Perform functional enrichment analysis [13].

Data Integration:

- Perform correlation analysis between DEGs and DEPs.

- Use Venn diagrams to identify overlapping changes.

- Conduct combined pathway enrichment analysis to identify biological processes significantly altered at both levels [13].

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for FBA: This diagram outlines the experimental workflow for integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data to constrain FBA models or define objective functions.

Protocol for TIObjFind Implementation

To implement the TIObjFind framework for identifying data-driven objective functions [11] [10]:

- Data Input Preparation: Collect experimental flux data (e.g., from isotopic tracing or physiological measurements) and a genome-scale metabolic model.

- Single-Stage Optimization: Solve a Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) formulation of FBA to find flux distributions that minimize squared error between predictions and experimental data for candidate objective functions.

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Represent the metabolic network and optimized fluxes as a directed, weighted graph (G(V,E)), where nodes represent metabolites and edges represent reactions weighted by flux.

- Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to identify essential pathways between source (e.g., glucose uptake) and target (e.g., product secretion) reactions.

- Coefficient of Importance Calculation: Compute CoIs based on each reaction's contribution to critical pathways, which then serve as weights in the final objective function.

TIObjFind Computational Framework: This diagram illustrates the TIObjFind computational process for identifying data-driven objective functions using metabolic pathway analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Driven FBA

| Category | Product/Technology | Key Function | Application in Objective Function Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | TRIzol Reagent [13] | Maintains RNA integrity during isolation from cells/tissues | Provides high-quality input for transcriptome sequencing |

| Proteomics Labeling | Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) / iTRAX Kits [13] | Multiplexed labeling for relative protein quantification across samples | Enables accurate differential protein expression analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry | Q-Exactive Mass Spectrometer [13] | High-resolution identification and quantification of peptides | Generates proteomic data for constraining metabolic models |

| Chromatography | Easy nLC 1200 System (Thermo Scientific) [13] | Nanoflow liquid chromatography for peptide separation | Front-end separation for complex proteomic samples |

| Computational Tools | MATLAB with maxflow package [11] [10] | Implementation of optimization and graph algorithms | Used for TIObjFind framework and minimum-cut calculations |

| Bioinformatics | Proteome Discoverer [13] | Computational pipeline for MS/MS data analysis | Protein identification, quantification, and statistical analysis |

| Single-Cell Proteomics | CITE-seq, ECCITE-seq [17] | Simultaneous measurement of transcriptome and proteome in single cells | Reveals cellular heterogeneity in metabolic networks |

The integration of proteomic and transcriptomic data represents a paradigm shift in defining biological objective functions for FBA. While transcriptomics offers a high-throughput snapshot of cellular regulation, proteomics provides a more direct link to metabolic activity through enzyme abundance. The development of advanced computational frameworks like TIObjFind, which can leverage these multi-omics datasets to calculate Coefficients of Importance, is significantly improving the biological relevance and predictive accuracy of metabolic models. As multi-omics technologies continue to advance, particularly in sensitivity and single-cell resolution, and as computational methods for integration become more sophisticated, researchers will be increasingly equipped to uncover context-specific metabolic objectives with profound implications for biotechnology and drug development.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone mathematical approach for analyzing metabolic networks, enabling researchers to predict cellular behavior by optimizing a defined biological objective under stoichiometric and capacity constraints [20]. The choice of objective function is arguably the most critical decision in FBA, as it mathematically represents the presumed evolutionary driving force that dictates how the metabolic network allocates resources. Early FBA implementations often relied on single objectives, most commonly maximization of biomass production, which serves as a proxy for cellular growth [20]. However, the biological reality is far more complex. Cells must balance the imperative for growth against other crucial metabolic demands, including energy maintenance (e.g., ATP production) and the management of repair processes [21] [2].

The limitations of single-objective optimization have led to the adoption of multi-objective frameworks. These approaches recognize that cellular metabolism operates not to satisfy a single goal, but to navigate trade-offs between competing objectives. A cell that maximizes only growth might neglect essential maintenance, while one that minimizes only energy expenditure would fail to proliferate. Therefore, the central challenge in modern FBA is to balance growth with energy and maintenance costs in a way that reflects true biological prioritization [21]. This guide compares the performance of different single and multi-objective functions, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed to inform their choice of objective function for more accurate metabolic modeling, particularly in fields like drug development where predicting cellular phenotypes is crucial.

Comparative Analysis of Objective Functions

Different objective functions lead to distinct predictions of metabolic flux, cellular growth, and even higher-order phenotypes like lifespan. The following table summarizes the performance of commonly used objective functions based on experimental validation studies, primarily in microbial models like E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Objective Functions in FBA

| Objective Function | Primary Mathematical Goal | Predicted Phenotype & Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximize Biomass [20] | Maximize flux through the biomass reaction (simulating growth) | Predicts high growth rates and essential nutrients accurately in standard conditions [20]. | Simple, well-understood, good for predicting growth rates and gene essentiality. | Often fails to predict byproduct secretion (e.g., acetate overflow) and metabolic switch behaviors [20]. |

| Maximize ATP Yield [20] | Maximize the total production of ATP from metabolic reactions | accurately describes data in some conditions, but can predict unrealistically low growth yields [20]. | Captures energy metabolism critical for maintenance; useful for simulating energy-limited environments. | May not be a primary evolutionary driver in many conditions; can violate energy balance if not properly constrained [20]. |

| Minimize Redox Potential [20] | Minimize the production of NADH (or equivalent redox carriers) | Identified as the most probable objective in one E. coli study, but condition-dependent [20]. | Can predict metabolic behaviors linked to redox balancing, such as fermentative pathways. | Less universally applicable than growth maximization; performance varies significantly across organisms and conditions. |

| Parsimonious Enzyme Usage [21] [2] | Two-stage: First maximize growth, then minimize total flux or enzyme usage. | Leads to more realistic flux distributions and improved predictions of replicative lifespan in yeast [21] [2]. | Reduces flux loops (loops); incorporates protein investment; improves lifespan predictions. | Increases computational complexity; requires careful tuning of flexibility constraints (ε) [21]. |

| Multi-Objective (Lexicographic) [21] [2] | Prioritized optimization (e.g., 1. Max Growth, 2. Max NGAM, 3. Min Glucose Uptake). | Simulates trade-offs; can replicate complex phenotypes like replicative ageing and metabolic switches [21]. | Most biologically realistic; can model condition-dependent priorities and hierarchical regulation. | Complex to implement and parameterize; solution can be sensitive to the chosen priority order [21]. |

The performance of these objectives is highly condition-dependent. For example, while maximizing ATP yield was found to be a good predictor in some E. coli studies, other analyses concluded that no single objective function performs best across all nutritional conditions [20]. The trend in the field is moving beyond single objectives. A multi-scale model of yeast ageing demonstrated that a parsimonious maximal growth objective (maximizing growth followed by minimizing enzyme usage) generated a realistic replicative lifespan of about 23 divisions, which was used as a reference for evaluating other objectives [21] [2]. This highlights how multi-objective optimization can better capture the compromises inherent in cellular metabolism.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Objective Functions

Validating the predictions of an FBA model against robust experimental data is essential. The following section outlines key methodologies used to generate data for comparing objective functions.

Multi-Scale Modeling of Replicative Ageing

Purpose: To systematically test the effect of different objective functions on long-term, dynamic phenotypes like replicative ageing in yeast, which cannot be easily measured from flux data alone [21] [2].

- Model Construction: A multi-scale model (yMSA) integrates several modules [21] [2]:

- Metabolism: An enzyme-constrained FBA (ecFBA) model of central carbon metabolism, including ROS production.

- Regulation: A Boolean model of key nutrient-sensing (Snf1, PKA, TOR) and oxidative stress (Yap1) pathways.

- Damage Dynamics: An ordinary differential equation (ODE) model tracking the accumulation of protein damage and its asymmetric distribution during cell division.

- Simulation Workflow:

- The FBA module is solved with a specific objective function (e.g., maximize growth, minimize ATP).

- The resulting optimal fluxes inform the regulatory network, which in turn imposes stricter constraints on enzyme usage.

- The regulated fluxes are used to update the ODE model for one time step, calculating damage accumulation and growth.

- Once a biomass threshold is reached, cell division is triggered.

- The cycle repeats until damage levels are too high and the FBA model becomes infeasible, marking cell death.

- Key Output Measurements:

- Replicative Lifespan: The total number of cell divisions before death.

- Generation Time: The time between successive cell divisions.

- Metabolic Fluxes: Average flux values for key reactions, particularly in early vs. late life.

This methodology connects the choice of objective function directly to an evolutionary property (ageing), providing a new validation metric beyond standard flux data [21] [2].

Lexicographic Optimization for Multi-Objective FBA

Purpose: To implement a hierarchical multi-objective optimization within a constraint-based model, ensuring a primary objective is satisfied before optimizing for secondary goals [21].

- Primary Optimization: Solve the initial Linear Programming (LP) problem, e.g.,

max z1 = c^T * v(such as biomass reaction), subject to mass balance (Sv=0), enzyme, and capacity constraints [21]. - Constraint Application: Fix the value of the first objective to its optimal value,

z1, allowing for a small flexibility factorε1(e.g., ≤ 1%). The new constraint isc^T * v ≥ z1 * (1 - ε1)[21]. - Secondary Optimization: Solve a second LP with a new objective, e.g.,

max/min z2 = d^T * v(such as minimizing total enzyme usage or maximizing NGAM), subject to all original constraints plus the new flexible constraint from step 2 [21]. - Iteration for Regulation: The process can be repeated, using the solution from the second optimization and applying another flexibility factor

ε2to prepare the flux distribution for the regulatory step in an integrated model [21].

This two-stage approach forces a priority order on the objectives, yielding a single, biologically interpretable solution that respects the hierarchical nature of cellular priorities [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualizations

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core logical relationships and workflows described in the experimental protocols.

Multi-Scale Model of Yeast Ageing Logic

Diagram 1: Multi-scale model logic for simulating replicative ageing.

Lexicographic Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Two-stage lexicographic optimization for multi-objective FBA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing and validating multi-objective FBA requires a combination of computational tools and biological resources. The following table details essential items for this research pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Multi-Objective FBA

| Item Name/Type | Function/Purpose | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstruction [20] | A structured database of all known metabolic reactions and genes for an organism. | Serves as the core model (constraint matrix S) for all FBA simulations. Examples include E. coli and yeast models. |

| ecFBA Model Formulation [21] | Extends standard FBA by adding explicit constraints on enzyme capacity and pool size. | Used to make flux distributions more realistic by accounting for proteomic investment [21]. |

| Lexicographic Optimization Code [21] | A script (e.g., in Python with COBRApy or MATLAB) that performs sequential LP optimizations. | Implements the two-stage approach to satisfy a primary objective (growth) before a secondary one (enzyme minimization). |

| Boolean Network Model [21] | A logical model representing the activity of transcription factors based on metabolic and stress signals. | Integrated with FBA to simulate regulation, e.g., down-regulating enzymes under oxidative stress [21]. |

| ODE Solver [21] | Numerical software for solving systems of ordinary differential equations. | Simulates the dynamics of damage accumulation and cell growth over time in a multi-scale model. |

| Isotopomer Flux Data [20] | Experimental data from 13C-labeling experiments that measure intracellular metabolic fluxes. | Serves as the gold-standard ground truth for validating and discriminating between different objective functions [20]. |

| Replicative Lifespan Data [21] [2] | Experimental measurements of the number of divisions a mother yeast cell undergoes. | Provides a phenotypic endpoint for validating model predictions from multi-objective functions related to ageing. |

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone of constraint-based metabolic modeling, enabling researchers to predict cellular metabolism at a genome scale. This mathematical approach utilizes an optimization criterion to select a distribution of fluxes from the feasible space delimited by metabolic reactions and imposed restrictions, all under the steady-state assumption [9]. The fundamental principle of FBA hinges on the hypothesis that cellular metabolism has evolved to optimize a specific biological objective. The choice of this objective function is therefore critical, as it directly determines the predicted flux distribution [21]. Historically, common objectives included the maximization of biomass (representing growth), the production of specific metabolites, or ATP generation [10] [21]. However, the assumption of a single, static objective function often fails to capture the dynamic adaptations of cellular metabolism in response to environmental changes [10] [11].

To address this limitation, computational frameworks have been developed to infer objective functions directly from experimental data. This guide spotlights two such frameworks: the established ObjFind framework and its novel extension, TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find). These frameworks aim to identify the metabolic objectives a cell is prioritizing under a given condition, thereby aligning FBA predictions with experimental observations and providing deeper insights into cellular metabolic strategies [10] [11] [22].

The ObjFind Foundation

The ObjFind framework represents a significant step toward data-driven inference of metabolic objectives. It builds upon traditional FBA by introducing Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which quantify each reaction's additive contribution to a proposed objective function [10] [11]. The core idea is to maximize a weighted sum of fluxes, ( \sum cj vj ), where the coefficients ( cj ) are scaled so their sum equals one. A higher ( cj ) value suggests that a reaction's flux aligns closely with its maximum potential in the experimental data, indicating its importance to the cellular objective [10]. Mathematically, ObjFind can be viewed as a scalarization of a multi-objective problem, where the goal is to minimize the sum of squared deviations between predicted and experimental flux data while maximizing the weighted combination of fluxes [10]. While demonstrating that a weighted combination of fluxes can capture the performance of observed data, a potential limitation of ObjFind is that it assigns weights across all metabolites, which could lead to overfitting to particular conditions [10].

TIObjFind: A Topology-Informed Evolution

TIObjFind is a novel framework that directly addresses some limitations of prior approaches by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA [10] [11]. Its primary innovation lies in using network topology to inform the inference process. Instead of weighting all reactions in the network, TIObjFind focuses on specific, critical pathways, thereby enhancing interpretability and reducing the risk of overfitting [10]. The framework is designed to analyze adaptive shifts in cellular responses across different stages of a biological system, quantifying each reaction's contribution through Coefficients of Importance derived from pathway structure [10] [11].

Table: Core Comparison between ObjFind and TIObjFind Frameworks

| Feature | ObjFind | TIObjFind |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Infers a weighted sum of fluxes as the objective function [10] | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA [10] [11] |

| Network Scope | Assigns Coefficients of Importance across all network reactions [10] | Focuses on specific pathways between start and target reactions [10] |

| Key Innovation | Introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions [10] | Uses topology (Mass Flow Graph) and minimum-cut algorithms to determine CoIs [10] |

| Primary Advantage | Data-driven alignment of FBA with experimental fluxes [10] | Enhanced interpretability and captures metabolic flexibility by highlighting critical pathways [10] [11] |

| Potential Drawback | Potential for overfitting to specific conditions [10] | Increased complexity in implementation and computation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The TIObjFind Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The TIObjFind framework operates through a structured, three-step process that combines optimization, network analysis, and interpretation [10].

Step 1: Optimization-based Objective Inference. The first step reformulates the problem of objective function selection as an optimization problem. The goal is to minimize the difference between FBA-predicted fluxes and available experimental flux data ((v^{exp})) while simultaneously maximizing an inferred metabolic goal represented by a weighted sum of fluxes ((c \cdot v)) [10]. This can be thought of as finding the Coefficients of Importance ((c)) that best explain the observed data through an FBA solution.

Step 2: Mass Flow Graph Construction. The flux distribution obtained from the optimization in Step 1 is mapped onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) [10]. This directed, weighted graph provides a pathway-based interpretation of the metabolic flux distribution, transforming the stoichiometric network into a flow network where reactions are nodes and edges represent metabolite flow between them.

Step 3: Pathway Analysis and Coefficient Calculation. Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) is applied to the Mass Flow Graph. A minimum-cut algorithm (specifically the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm, chosen for its computational efficiency) is used to identify critical pathways and bottlenecks between predefined start (e.g., glucose uptake) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion) [10]. The results of this analysis are used to compute the final Coefficients of Importance, which serve as pathway-specific weights, quantifying each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective under the given conditions [10].

Case Study: Clostridium acetobutylicum Fermentation

A key case study demonstrating TIObjFind's application involves the fermentation of glucose by Clostridium acetobutylicum [10] [11]. In this study, the framework was used to determine pathway-specific weighting factors across different fermentation stages. The method assessed the influence of Coefficients of Importance on flux predictions, demonstrating a significant impact on reducing prediction errors and improving alignment with experimental data compared to static objective functions [10] [11]. By analyzing the differences in Coefficients of Importance between stages, TIObjFind successfully revealed shifting metabolic priorities as the fermentation progressed, a dynamic adaptation that traditional FBA with a fixed objective would struggle to capture.

Case Study: Multi-Species IBE System

In a more complex second case study, TIObjFind was applied to a multi-species system for isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) production, comprising C. acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii [10] [11]. Here, the Coefficients of Importance were used as hypothesis coefficients within the objective function to assess cellular performance in a community context. The application of TIObjFind resulted in a good match with observed experimental data and successfully captured stage-specific metabolic objectives within the co-culture, showcasing its utility in modeling complex, multi-organism metabolic networks [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Approaches

Other Inverse FBA Methods

While ObjFind and TIObjFind are powerful frameworks, other methods also address the inverse FBA problem. The invFBA approach, for instance, uses linear programming duality to characterize the space of all possible objective functions compatible with measured fluxes [22]. Its key advantage is the guarantee of a globally optimal solution found in polynomial time. invFBA has been successfully tested on simulated E. coli data and applied to flux measurements in long-term evolved E. coli strains, revealing objective functions that provide insight into metabolic adaptation trajectories [22]. Another approach uses a Bayesian framework to estimate the objective function, though it assumes normally distributed experimental fluxes and does not fully exploit the structure of the FBA problem [22].

Comparison of Objective Function Inference Frameworks

Table: Comparison of Frameworks for Inferring Metabolic Objective Functions

| Framework | Underlying Methodology | Key Features | Validated Use-Cases | Software Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ObjFind | FBA with weighted sum of fluxes [10] | Infers Coefficients of Importance for all reactions; risk of overfitting [10] | Not specified in detail; precursor to TIObjFind [10] | GitHub: J-Morrissey/ObjFind-M [23] |

| TIObjFind | Integration of MPA and FBA [10] [11] | Topology-informed; uses Min-Cut algorithm; focuses on key pathways; reduces overfitting [10] | C. acetobutylicum fermentation; Multi-species IBE system [10] [11] | MATLAB and Python scripts available [10] [11] |

| invFBA | Linear programming duality [22] | Characterizes space of all possible objectives; guarantees global optimum [22] | Simulated E. coli data; Time-dependent S. oneidensis fluxes; Evolved E. coli strains [22] | Not specified in sources |

| KBase Compare FBA Solutions | Side-by-side comparison of pre-existing FBA solutions [24] | Compares objective values, reaction fluxes, and metabolite uptake/excretion [24] | General-purpose FBA comparison within the KBase platform [24] | Web app on KBase platform [24] |

Successfully implementing frameworks like TIObjFind requires a suite of computational and data resources. Below is a curated list of essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Objective Function Inference

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Relevance to TIObjFind/ObjFind |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | Data / Model | A stoichiometric matrix (S) defining all metabolic reactions and metabolites in the organism [10] | The foundational constraint matrix for all FBA and inverse FBA calculations. |

| Experimental Flux Data (v_exp) | Data | Measured intracellular or exchange fluxes, e.g., from ¹³C labeling experiments [10] [22] | Essential input data for inferring and validating the objective function. |

| MATLAB | Software | Numerical computing environment [10] | Primary implementation language for TIObjFind, including its maxflow package [10]. |

| Python with pySankey | Software | Programming language and visualization library [10] | Used for visualizing results and flux distributions from TIObjFind [10]. |

| KEGG / EcoCyc | Database | Curated databases of biological pathways, genomic, and chemical information [10] [11] | Foundational resources for building and curating metabolic network models. |

| GitHub Repository (TIObjFind) | Code | Custom scripts for the TIObjFind analysis [10] [11] | Contains case study data, metabolic models, and MATLAB/Python codes for running simulations. |

| ObjFind-M GitHub Repository | Code | Package to infer metabolic objectives from fluxomic and metabolomic data [23] | Reference implementation for the original ObjFind framework. |

Technical Implementation and Pathway Visualization

Implementation Details

The TIObjFind framework was implemented in MATLAB, with custom code for the primary analysis [10]. The critical minimum-cut set calculations were performed using MATLAB's maxflow package, employing the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for its superior computational efficiency, which delivers near-linear performance across various graph sizes [10]. Visualization of the resulting flux distributions and key pathways was accomplished using Python with the pySankey package, allowing for intuitive graphical representation of complex flow relationships [10].

Visualizing Metabolic Pathways and Flux Dependencies

Understanding the dependencies and flow of metabolites is central to TIObjFind. The following diagram illustrates a simplified metabolic network, showing how a primary input (e.g., Glucose) is distributed through central metabolism toward various target outputs, with the thickness of the arrows representing the flux magnitude.

The development of ObjFind and TIObjFind represents a significant shift from assuming static metabolic objectives to inferring them directly from experimental data. While ObjFind introduced the valuable concept of Coefficients of Importance, its potential for overfitting prompted the creation of the more sophisticated TIObjFind. By leveraging network topology and pathway analysis, TIObjFind enhances the interpretability of complex metabolic networks and provides a systematic framework for modeling adaptive cellular responses [10] [11].

The comparative case studies demonstrate that TIObjFind effectively reduces prediction errors and aligns with experimental data across different biological systems, from single-species fermentations to complex microbial communities [10] [11]. As the field of systems biology continues to evolve, the integration of multi-omics data and machine learning with these inference frameworks promises to further refine our understanding of cellular metabolic goals. The availability of their codebases on public platforms like GitHub ensures that these powerful tools are accessible to the broader research community, facilitating further development and application in fields ranging from microbial strain improvement to drug discovery [10] [23].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic behavior in various biological systems. As a constraint-based approach, FBA utilizes genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate metabolic flux distributions, enabling researchers to predict cellular phenotypes under specific environmental and genetic conditions. The core principle of FBA involves optimizing a defined cellular objective—most commonly biomass production—while satisfying stoichiometric and capacity constraints derived from biochemical knowledge. This powerful framework has found extensive applications across multiple domains, particularly in drug target identification and metabolic engineering of microbial strains for industrial biotechnology.

The predictive capability of FBA fundamentally depends on the appropriate selection of objective functions that accurately represent cellular goals in different contexts. While biomass maximization effectively simulates growth-oriented phenotypes in microorganisms, this assumption may not hold for specialized metabolic states such as secondary metabolite production or stressed conditions. Consequently, advanced FBA frameworks have been developed to address these limitations, incorporating multi-objective optimization, regulatory constraints, and machine learning integration to improve prediction accuracy. This review examines current FBA methodologies through comparative case studies, highlighting how different objective functions and optimization strategies impact predictive performance in pharmaceutical and bioproduction applications.

FBA Frameworks for Drug Target Prediction

Comparative Analysis of FBA Approaches for Secondary Metabolism

Table 1: Comparison of FBA Frameworks for Drug Target Identification in Secondary Metabolism

| Framework | Primary Approach | Objective Function | Advantages | Drug Discovery Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FBA | Linear programming with stoichiometric constraints | Biomass maximization | Computational efficiency, well-established | Limited for secondary metabolites unrelated to growth |

| TIObjFind | Integration of Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA | Pathway-weighted optimization using Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Identifies condition-specific objectives, aligns with experimental data | Captures metabolic adaptations in pathogens, identifies stage-specific drug targets [10] |

| smGSMM | Genome-scale modeling of secondary metabolic pathways | Varied objectives including product formation | Direct incorporation of secondary metabolite pathways | Antibiotic discovery, targeting specialized metabolite production in actinomycetes [25] |

| NEXT-FBA | Hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven approach | Context-specific objective inference | Improved intracellular flux predictions by integrating multiple data types | Enhanced prediction of metabolic vulnerabilities in disease states [19] |

Drug target identification requires understanding metabolic vulnerabilities in pathogens or diseased cells. Traditional FBA approaches face significant challenges in this domain, particularly when targeting secondary metabolism, as these metabolic pathways are often disconnected from growth objectives. The TIObjFind framework addresses this limitation by introducing Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to context-specific objective functions, thereby aligning predictions with experimental flux data [10]. This approach successfully captures adaptive metabolic shifts in pathogens throughout infection stages, enabling identification of stage-specific drug targets that might be missed by growth-centric models.

For antibiotic discovery specifically, FBA-based modeling of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes and other antibiotic-producing microorganisms has shown considerable promise. Specialized genome-scale metabolic models (smGSMMs) incorporate secondary metabolic pathways, allowing researchers to predict genetic interventions that enhance antibiotic production or identify essential reactions in pathogen metabolism that serve as potential drug targets [25]. These frameworks face unique challenges in pathway reconstruction due to incomplete database coverage of species-specific secondary metabolism, often requiring manual curation or specialized tools like BiGMeC for nonribosomal peptide and polyketide pathway assembly.

Experimental Protocol for Drug Target Identification Using FBA

The standard workflow for FBA-based drug target prediction involves multiple stages of computational analysis and experimental validation:

Pathogen Model Reconstruction: Develop a high-quality GEM for the target pathogen, incorporating all known metabolic reactions, gene-protein-reaction associations, and transport processes. Curated models can be obtained from databases like AGORA or constructed de novo from annotated genomes.

Condition-Specific Constraining: Define metabolic constraints reflecting the infection environment, including nutrient availability, pH, oxygen tension, and other relevant factors through uptake rate bounds on exchange reactions.

Objective Function Selection: Implement appropriate objective functions, which may include:

- Biomass maximization for growth-critical targets

- Pathway-weighted objectives using TIObjFind for condition-specific vulnerabilities [10]

- Vital cellular functions beyond growth (e.g., energy production, redox balance)

Essentiality Analysis: Perform systematic gene knockout simulations to identify essential reactions under infection-relevant conditions. Potential drug targets are reactions whose inhibition disrupts essential metabolic functions.

Selectivity Validation: Compare essential reactions in pathogen versus human metabolic models to identify targets with minimal host toxicity. The specificity of bacterial metabolic pathways often provides selective targeting opportunities.

Experimental Confirmation: Test predicted essential genes through genetic knockout experiments or chemical inhibition in culture models, measuring impacts on growth viability and metabolic function.

Figure 1: Workflow for FBA-based drug target identification

FBA Frameworks for Microbial Strain Engineering

Comparison of Strain Design Algorithms

Table 2: Comparison of FBA-Based Strain Engineering Tools

| Tool/Method | Optimization Approach | Modification Types | Performance Advantages | Case Study Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OptKnock | Bi-level optimization (maximize product while allowing growth) | Gene knockouts only | Simple implementation, growth-coupled production | Limited to 5 reactions, may yield low minimum product flux [26] |

| RobustKnock | Max-min optimization (maximize minimum product yield) | Gene knockouts only | Guarantees non-zero product yield under uncertainty | Improved production stability but limited to knockouts [26] |

| RobOKoD | Flux variability analysis profiling | Knockouts, overexpression, dampening | Comprehensive modification strategies, ranked interventions | Butanol production in E. coli, favorable predictions vs. experimental strains [26] |

| TIObjFind | MPA-integrated FBA with Coefficients of Importance | Pathway weighting, objective identification | Captures metabolic shifts, aligns with multi-stage fermentation | Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation, multi-species IBE system [10] |

Microbial strain engineering for biochemical production represents one of the most successful applications of FBA in industrial biotechnology. Traditional methods like OptKnock and RobustKnock focus exclusively on gene knockout strategies to couple product formation with growth, but their limitations have prompted development of more comprehensive approaches. RobOKoD (Robust, Overexpression, Knockout and Dampening) utilizes flux variability analysis to profile each reaction under different production levels of target compounds and biomass, subsequently identifying potential knockout, overexpression, or dampening targets ranked by their predicted effectiveness [26].

In a comparative case study of butanol production in Escherichia coli, RobOKoD demonstrated favorable design predictions when compared against both OptKnock and RobustKnock, with its predictions showing stronger alignment with experimentally validated strains [26]. This superior performance stems from its ability to recommend diverse genetic intervention types beyond mere knockouts, allowing more nuanced metabolic engineering strategies that better reflect practical laboratory approaches.

For complex fermentation processes involving multiple stages or species, the TIObjFind framework provides unique advantages by identifying stage-specific objective functions. Applied to Clostridium acetobutylicum fermentation and a multi-species isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) system, TIObjFind successfully captured metabolic objective shifts throughout fermentation stages, demonstrating close alignment with experimental data [10]. This capability is particularly valuable for industrial bioprocesses where metabolic objectives evolve throughout the production timeline.

Experimental Protocol for Strain Design Validation

Implementing FBA-predicted strain designs requires careful experimental validation:

Base Strain Preparation: Select appropriate microbial chassis (typically E. coli or yeast for well-characterized genetics) and establish baseline metabolic characteristics.

Genetic Modification Implementation:

- For knockout targets: Use CRISPR-Cas9 or homologous recombination for gene deletion

- For overexpression targets: Implement strong promoters or multi-copy plasmids

- For dampening targets: Use tunable promoters or ribosomal binding site engineering

Fermentation Conditions: Cultivate engineered strains in controlled bioreactors with defined media, monitoring growth parameters (OD600), substrate consumption, and product formation over time.

Metabolic Flux Analysis: Employ 13C-labeling experiments and metabolic flux analysis to quantify in vivo flux distributions, comparing them to FBA predictions.

Performance Metrics: Quantify key performance indicators including product yield (g product/g substrate), productivity (g/L/h), titer (g/L), and growth characteristics.

Model Refinement: Use discrepancies between predicted and measured fluxes to identify missing constraints or regulatory effects, iteratively improving model accuracy.

The E. coli iML1515 model exemplifies a well-curated GEM for strain engineering applications. This comprehensive model includes 1,515 open reading frames, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites, providing a robust platform for predicting metabolic behavior after genetic modifications [27]. Implementation of enzyme constraints using tools like ECMpy further enhances prediction accuracy by accounting for enzyme capacity limitations based on kcat values and protein abundance data [27].

Figure 2: Strain design and validation workflow

Critical Assessment of Objective Function Selection

Performance Metrics Across Applications

The selection of appropriate objective functions fundamentally influences FBA prediction accuracy across both drug target identification and strain engineering applications. Biomass maximization, while biologically reasonable for fast-growing microorganisms under optimal conditions, frequently fails to capture metabolic behaviors in specialized contexts such as secondary metabolite production or stress conditions. In secondary metabolism, where target compounds are often minimally connected to growth objectives, biomass maximization performs particularly poorly, necessitating alternative objective functions [25].

Framework-specific objective functions demonstrate variable performance across applications. TIObjFind's Coefficients of Importance approach shows superior performance in capturing metabolic adaptations throughout biological processes, successfully identifying stage-specific objectives in multi-stage fermentations and complex community interactions [10]. Similarly, RobOKoD's multi-intervention approach outperforms knockout-only methods in strain engineering applications, as evidenced by its favorable predictions for butanol-producing E. coli strains compared to experimentally validated designs [26].

For microbial community modeling, objective function selection becomes increasingly complex. Tools like MICOM and COMETS implement different strategies for community objective functions, with MICOM employing a cooperative trade-off approach that maximizes both community and individual growth rates, while COMETS uses dynamic FBA without a community-level objective [28]. Evaluation studies reveal that prediction accuracy varies significantly between these approaches, with curated metabolic models generally outperforming automated reconstructions regardless of the objective function selected [28].

Integrated Workflow for Objective Function Selection

Selecting optimal objective functions for specific applications requires systematic evaluation:

Context Analysis: Determine biological context (primary vs. secondary metabolism, monoculture vs. community, growth vs. non-growth conditions)

Data Availability Assessment: Evaluate available experimental data (transcriptomics, fluxomics, metabolomics) for constraint implementation

Algorithm Selection: Choose FBA framework matching application requirements:

Multi-Objective Considerations: Implement lexicographic optimization or Pareto front analysis when multiple cellular objectives potentially coexist

Validation Priority: Prioritize frameworks that enable experimental validation through clear testable predictions

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA Applications

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | iML1515 (E. coli) | Well-curated metabolic model for strain engineering | [27] |

| AGORA models | Semi-curated metabolic reconstructions for gut bacteria | [28] | |

| Sco-GEM (Streptomyces coelicolor) | Specialized model for secondary metabolism | [25] | |

| Pathway Reconstruction Tools | antiSMASH | Biosynthetic gene cluster identification | [25] |

| BiGMeC | Pathway reconstruction for NRPs and PKs | [25] | |

| RetroPath 2.0 | Retrosynthesis-based pathway design | [25] | |

| FBA Software Platforms | COBRApy | Python package for FBA implementation | [27] |

| COMETS | Dynamic FBA with spatial modeling | [28] | |

| MICOM | Microbial community metabolic modeling | [28] | |

| ECMpy | Enzyme-constrained model construction | [27] | |

| Experimental Validation Reagents | 13C-labeled substrates | Metabolic flux analysis | [10] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Genetic modification implementation | [26] | |

| Tunable promoter systems | Fine-tuning gene expression | [26] |