Beyond the Blueprint: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Next-Generation Metabolic Model Architectures

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the expanding landscape of metabolic modeling architectures.

Beyond the Blueprint: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Next-Generation Metabolic Model Architectures

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the expanding landscape of metabolic modeling architectures. It covers foundational principles of genome-scale, dynamic, and constraint-based models, explores their specific applications in strain engineering and drug target discovery, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like flux imbalances and gaps. By comparing the predictive performance and validation standards of different model types, this guide empowers scientists to select, optimize, and implement the most effective modeling strategies for their specific biomedical research goals.

Mapping the Metabolic Modeling Landscape: From Core Principles to Advanced Architectures

Metabolic modeling has emerged as a cornerstone of systems biology, providing computational frameworks to simulate and predict cellular behavior. These models serve as critical tools for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand metabolic alterations in disease states, engineer industrial microbial strains, and investigate host-microbiome interactions in health and aging. The field is primarily dominated by two complementary architectural paradigms: stoichiometric models and kinetic models. Each architecture possesses distinct theoretical foundations, data requirements, and predictive capabilities, making them suitable for different research scenarios and objectives. Stoichiometric models, including constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, enable genome-scale analysis of metabolic networks by leveraging mass balance constraints and reaction stoichiometry. In contrast, kinetic models incorporate enzyme mechanics and dynamic parameters to simulate metabolic concentration changes over time, providing temporal resolution at the expense of scale and comprehensive parameter requirements. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these architectural frameworks, their hybrid derivatives, and their applications in biotechnology and biomedical research, equipping scientists with the knowledge to select appropriate modeling strategies for their specific research contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Architectural Principles

Stoichiometric Modeling Architecture

Stoichiometric modeling approaches are built upon the fundamental principle of mass conservation within biochemical reaction networks. The core mathematical representation is the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sᵢⱼ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. This architecture operates under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, mathematically expressed as S·v = 0, where v is the flux vector through each metabolic reaction [1] [2]. This formulation enables the analysis of feasible metabolic states without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, making it particularly valuable for genome-scale modeling where comprehensive kinetic data is seldom available.

The most widely applied implementation of stoichiometric modeling is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which optimizes an objective function (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis, or metabolite synthesis) to predict flux distributions through metabolic networks [3]. FBA and related approaches have been successfully implemented in numerous genome-scale models (GEMs) of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, including Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and human metabolic models [3]. Related methodologies include Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis, which identifies minimal functional metabolic pathways that operate at steady state, providing insight into network redundancy and pathway efficiency [2]. The architectural strength of stoichiometric models lies in their scalability to organism-wide networks encompassing thousands of reactions, though this comes at the cost of temporal resolution and concentration dynamics.

Kinetic Modeling Architecture

Kinetic models employ differential equations to describe the time-dependent changes in metabolite concentrations based on enzymatic mechanisms and kinetic parameters. The general form is dX/dt = S·v(X,p), where X represents metabolite concentrations, S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the vector of reaction rates that are functions of both metabolite concentrations and kinetic parameters p [1]. Unlike stoichiometric approaches, kinetic models explicitly incorporate enzyme mechanics through parameters such as the catalytic constant (kcat), Michaelis-Menten constant (Km), and enzyme inhibition/activation constants [1]. This architectural framework enables the simulation of metabolic dynamics, transient responses to perturbations, and concentration changes over time.

The implementation of kinetic models requires extensive parameterization, typically restricting their application to pathway-scale models of central carbon metabolism, glycolysis, or specialized biosynthetic pathways [1]. Recent advances in deep learning frameworks have aimed to predict substrate affinities (Km) and catalytic turnover rates (kcat) from molecular features of enzymes and substrates, potentially expanding the scope of kinetic modeling [3]. However, even state-of-the-art predictors like DLkcat and TurNup are not yet sufficiently reliable for precise strain design applications without experimental validation [3]. The architectural advantage of kinetic models is their ability to provide dynamic predictions of metabolic behavior, though this comes with significant parameterization challenges and computational constraints at larger scales.

Hybrid and Integrated Modeling Approaches

Next-generation metabolic modeling architectures are increasingly embracing hybrid approaches that integrate principles from both stoichiometric and kinetic frameworks. These integrated architectures aim to overcome the limitations of individual approaches while leveraging their respective strengths. Enzyme-constrained models represent one such hybrid architecture, incorporating proteomic limitations into stoichiometric models by imposing constraints on total enzyme capacity and catalytic rates [3] [1]. These models implement the total enzyme activity constraint, which limits the sum of enzyme concentrations based on the assumption that engineered organisms should not significantly exceed the protein production capacity of wild-type strains [1].

Another emerging hybrid approach integrates molecular import/export mechanisms with traditional metabolic networks, addressing the limitation of "promiscuous nonspecific uptake channels" in standard GEMs [3]. These integrated models employ explicit molecular modeling of nutrient uptake through specific channels, such as the use of PoreDesigner for tuning solute selectivity in outer membrane pores, leading to more accurate predictions of intracellular metabolite pools [3]. Additionally, multi-scale modeling architectures now enable the investigation of host-microbiome metabolic interactions through integrated "metaorganism" models that combine individual metabolic networks of host tissues and microbial species via shared extracellular compartments [4]. These advanced architectures represent the cutting edge of metabolic modeling, pushing the boundaries of predictive capability while introducing new computational challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Modeling Architectures

| Architectural Feature | Stoichiometric Models | Kinetic Models | Hybrid/Integrated Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Mass balance, steady-state assumption | Enzyme kinetics, differential equations | Combined principles from multiple approaches |

| Mathematical Representation | Stoichiometric matrix S with S·v = 0 | Differential equations dX/dt = S·v(X,p) | Varies (often constrained optimization) |

| Primary Scale of Application | Genome-scale (100s-1000s of reactions) | Pathway-scale (10s of reactions) | Pathway to multi-scale systems |

| Temporal Resolution | None (steady-state only) | Dynamic (time-course simulations) | Limited dynamic or multiple timescales |

| Key Parameters | Reaction stoichiometry, flux bounds | kcat, Km, enzyme inhibition constants | Combined parameters with additional constraints |

| Computational Demand | Moderate (linear/convex optimization) | High (numerical integration of ODEs) | Moderate to high depending on integration method |

| Key Limitations | No dynamics, requires objective function | Parameter uncertainty, limited scalability | Implementation complexity, data integration challenges |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Experimental Data and Applications

Predictive Performance Across Biological Domains

The performance of different metabolic modeling architectures varies significantly across biological applications. For metabolic engineering objectives, stoichiometric models have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting gene knockout strategies for strain optimization, with tools like OptKnock and OptForce enabling targeted overproduction of valuable compounds including 1,4-butanediol and limonene in engineered E. coli strains [3]. Comparative studies have shown that enzyme-constrained variants of stoichiometric models improve prediction accuracy by incorporating proteomic limitations, better aligning simulated fluxes with experimental measurements [1]. In one detailed optimization case study aiming to increase sucrose accumulation in sugarcane, the introduction of a total enzyme activity constraint reduced the objective function value 10-fold, while additional homeostatic constraints further refined predictions to achieve a 34% improvement over the original model [1].

In biomedical research, stoichiometric models have enabled the investigation of cancer metabolism through context-specific reconstruction algorithms that integrate transcriptomic data with generic human metabolic models [5]. A benchmark-driven comparison of these algorithms revealed substantial variation in predictive performance, leading to the development of hybrid approaches that combine advantageous features from multiple methods [5]. More recently, integrated host-microbiome metabolic models have elucidated aging-associated metabolic decline, demonstrating reduced beneficial interactions in older mice and predicting microbiota-dependent host functions in nucleotide metabolism critical for intestinal barrier function [4]. Kinetic models have found particular utility in pathway analysis and drug targeting, where dynamic simulations of enzyme inhibition provide critical insights for therapeutic development, especially in viral infections where pathogens reprogram host metabolism [3].

Quantitative Validation and Model Accuracy

Rigorous validation of metabolic model predictions against experimental data is essential for assessing architectural performance. 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) serves as the gold standard for validating intracellular flux predictions, enabling direct comparison between computational and empirical flux measurements [2]. A landmark study comparing Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis with experimental flux measurements in Corynebacterium glutamicum and Brassica napus revealed a clear relationship between structural network properties and metabolic activity, validating the predictive capacity of constraint-based approaches [2]. The consistency between EFM analysis and experimental flux measurements across these distinct biological systems demonstrates that structural analysis can capture significant aspects of metabolic activity, particularly for central carbon metabolism [2].

For kinetic models, parameter uncertainty remains a significant challenge, with studies showing that optimization without appropriate constraints can lead to biologically unrealistic predictions, including 1500-fold concentration increases that would be cytotoxic [1]. The implementation of homeostatic constraints, which limit metabolite concentration changes to physiologically plausible ranges (±20% in the sugarcane case study), dramatically improves prediction biological feasibility despite reducing objective function values [1]. Benchmarking studies of context-specific metabolic reconstruction algorithms have employed diverse validation metrics including essential gene prediction, growth rate correlation, and metabolite secretion rates, revealing that no single algorithm performs optimally across all benchmarks, highlighting the need for careful architectural selection based on specific research objectives [5].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Metrics for Metabolic Modeling Architectures

| Validation Approach | Application in Stoichiometric Models | Application in Kinetic Models | Representative Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis | Comparison of predicted vs. measured fluxes | Less commonly applied due to scale limitations | Clear relationship between EFM structure and measured fluxes in C. glutamicum and B. napus [2] |

| Gene Essentiality Predictions | Comparison with gene knockout experiments | Rarely applied at genome-scale | Context-specific cancer models show varying performance (AUC: 0.65-0.82 across algorithms) [5] |

| Metabolite Concentration Validation | Indirect via flux coupling | Direct comparison with measured concentrations | Homeostatic constraints prevent unrealistic concentration predictions (>1000-fold changes) [1] |

| Growth Rate Predictions | Correlation with measured growth rates | Limited to specific conditions | Cancer cell line growth predictions show moderate correlation (R²: 0.41-0.68) [5] |

| Enzyme Capacity Constraints | Validation against proteomic data | Built into model structure | Total enzyme activity constraint improves biological realism of predictions [1] |

| Community Interaction Prediction | Metabolite exchange validation | Rarely applied | Consensus models improve functional coverage in microbial communities [6] |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Stoichiometric Model Reconstruction and Simulation

The reconstruction of stoichiometric metabolic models follows a systematic workflow that transforms genomic information into predictive computational models. The protocol begins with genome annotation and reaction network assembly, where genes are mapped to biochemical reactions using databases such as BiGG Models and ModelSEED [3] [6]. For consensus reconstruction approaches, multiple automated tools (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) are employed in parallel, followed by integration of their outputs to reduce tool-specific biases and improve reaction coverage [6]. The draft reconstruction then undergoes network refinement, including gap-filling to eliminate dead-end metabolites and ensure network connectivity, and the definition of biomass composition reactions appropriate for the target organism [6].

Once reconstructed, the model is constrained using experimental data, including metabolite uptake/secretion rates and gene essentiality information [5]. The constrained model can then be simulated using Flux Balance Analysis to predict optimal flux distributions under specified environmental conditions or genetic perturbations. For context-specific applications, such as modeling cancer metabolism or host-microbiome interactions, additional transcriptomic or proteomic data integration is performed using algorithms like GIMME, iMAT, mCADRE, or INIT to generate tissue- or condition-specific models [5]. Validation against experimental flux measurements and essential gene datasets completes the workflow, with iterative refinement to improve model accuracy and predictive capability.

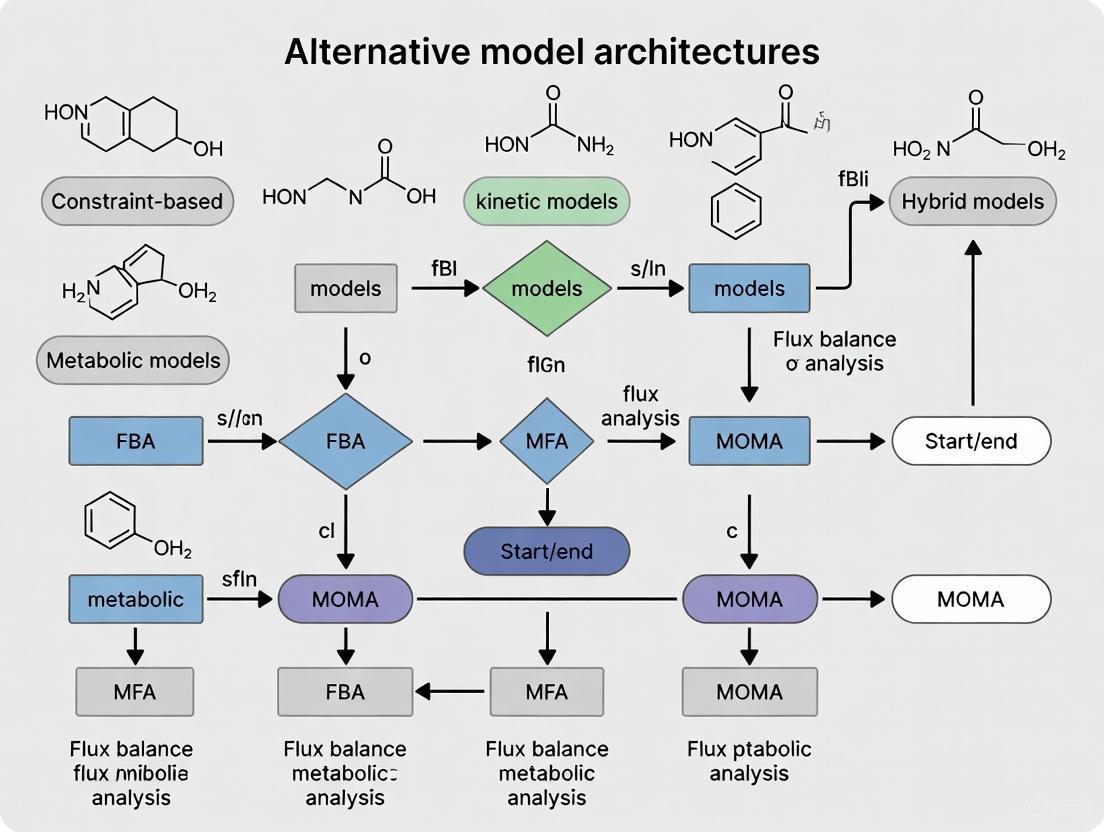

Diagram 1: Stoichiometric Model Reconstruction Workflow. This protocol outlines the systematic process for developing stoichiometric metabolic models from genomic information.

Protocol for Kinetic Model Development and Parameterization

Kinetic model development follows a distinct workflow focused on dynamic parameterization and validation. The protocol initiates with pathway definition and mechanistic specification, where the target metabolic pathway is delineated and appropriate enzymatic mechanisms (Michaelis-Menten, mass action, allosteric regulation) are assigned to each reaction [1]. The subsequent parameter acquisition phase involves compiling kinetic constants (kcat, Km, Ki) from literature, databases, or experimental measurements, with emerging approaches using deep learning predictors like DLkcat to estimate unknown parameters [3]. Parameter estimation through model fitting to experimental data follows, often employing optimization algorithms to minimize the difference between simulated and measured metabolite concentrations.

The parameterized model undergoes steady-state identification and stability analysis to identify biologically feasible operating points, with eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix calculated to ensure stability [1]. Critical to this process is the implementation of physiological constraints, including total enzyme activity limits and homeostatic metabolite concentration ranges, to maintain biological realism [1]. The constrained model is then simulated to predict dynamic responses to perturbations, with validation against time-course metabolomic data completing the initial development cycle. For models of engineered systems, strain design optimization can be performed by manipulating enzyme expression levels within physiologically plausible bounds, followed by experimental implementation and model refinement based on performance data.

Diagram 2: Kinetic Model Development Protocol. This workflow outlines the iterative process for developing kinetic models with emphasis on parameter acquisition and constraint implementation.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Metabolic Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Architectural Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction Software | CarveMe, gapseq, KBase | Automated generation of draft genome-scale models from genomic data | Primarily stoichiometric models |

| Simulation Platforms | COBRA Toolbox, RAVEN Toolbox, CellNetAnalyzer | Constraint-based simulation and analysis of metabolic networks | Primarily stoichiometric models |

| Kinetic Parameter Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Source of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) for model parameterization | Primarily kinetic models |

| Deep Learning Predictors | DLkcat, TurNup | Prediction of catalytic turnover rates from molecular features | Kinetic and enzyme-constrained models |

| Stoichiometric Databases | BiGG Models, ModelSEED | Curated biochemical reaction databases with standardized nomenclature | Primarily stoichiometric models |

| Flux Validation Tools | 13C-MFA, elementary flux mode analysis | Experimental and computational validation of predicted flux distributions | Both architectures (validation phase) |

| Context-Specific Algorithms | GIMME, iMAT, mCADRE, INIT | Integration of omics data to generate tissue/condition-specific models | Primarily stoichiometric models |

| Community Modeling Frameworks | COMMIT, MICOM | Metabolic modeling of microbial communities and host-microbiome interactions | Both architectures (increasing application) |

The comparative analysis of metabolic modeling architectures reveals a complex landscape where no single approach dominates across all applications. Each architectural framework offers distinct advantages and suffers from specific limitations that must be carefully considered in the context of research objectives, data availability, and computational resources. Stoichiometric models, particularly implementations of flux balance analysis and elementary flux mode analysis, provide unparalleled scalability to genome-wide networks and have demonstrated remarkable success in metabolic engineering and biomedical applications. Their relatively modest data requirements and computational efficiency make them ideal for initial system characterization and hypothesis generation. However, their inability to simulate dynamics and reliance on steady-state assumptions represent significant limitations for investigating transient metabolic behaviors or regulatory mechanisms.

Kinetic models offer superior temporal resolution and the ability to simulate metabolic dynamics, making them invaluable for pathway analysis, drug target identification, and understanding metabolic regulation. Their demanding parameter requirements and limited scalability currently restrict their application to focused metabolic subsystems, though advances in parameter estimation and deep learning prediction are gradually alleviating these constraints. Hybrid approaches, including enzyme-constrained models and integrated host-microbiome frameworks, represent the cutting edge of metabolic modeling architecture, combining strengths from multiple paradigms while introducing new computational challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, architectural selection should be guided by specific research questions, with stoichiometric approaches preferred for genome-scale discovery and kinetic methods reserved for focused dynamic investigations of prioritized pathways. As the field advances, continued development of hybrid architectures and parameter prediction methods will further blur the distinctions between approaches, ultimately providing more comprehensive and predictive models of metabolic systems.

A Brief History and Expanding Scope of GEMs

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational frameworks that define the relationship between genotype and phenotype by mathematically representing the metabolic network of an organism. They computationally describe gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for entire metabolic genes, allowing prediction of metabolic fluxes for systems-level studies [7]. The first GEM was reconstructed for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999, marking the beginning of a new era in systems biology [7]. Since then, the field has expanded dramatically, with GEMs now covering diverse organisms across bacteria, archaea, and eukarya [8].

The growth in GEM development has been exponential. As of February 2019, GEMs had been reconstructed for 6,239 organisms (5,897 bacteria, 127 archaea, and 215 eukaryotes), with 183 of these being manually curated to high quality [7]. This expansion has been powered by both manual reconstruction efforts and the development of automated reconstruction tools, enabling researchers to model organisms with scientific, industrial, and medical importance [7] [8].

Table: Milestone GEMs in Model Organisms

| Organism | Key Model Versions | Gene Count | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | iJE660, iML1515 | 1,515 genes | Strain development, core metabolism analysis [7] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | iFF708, Yeast7, Yeast8, Yeast9 | >1,700 genes (Yeast8) | Bioproduction, systems biology [9] |

| Bacillus subtilis | iYO844, iBsu1103, iBsu1144 | 1,144 genes | Enzyme and protein production [7] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | iEK1101 | 1,101 genes | Drug target identification [7] |

| Homo sapiens | Recon 1-3, HMR 1-2 | Thousands of reactions | Disease modeling, drug discovery [10] |

The reconstruction of GEMs follows a systematic process beginning with genome annotation, followed by drafting the network from databases like KEGG, manual curation to fill metabolic gaps, and finally validation through experimental data [11]. The resulting models are converted into a mathematical format—a stoichiometric matrix (S matrix)—where columns represent reactions, rows represent metabolites, and entries are stoichiometric coefficients [12].

Core Architecture: How GEMs Work

Fundamental Principles and Constraints

GEMs are built upon several foundational principles that enable accurate prediction of metabolic behavior. The core mathematical representation is the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sᵢⱼ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. This matrix defines the system of linear equations under the steady-state assumption, meaning internal metabolites must be produced and consumed in a flux-balanced manner (Sv = 0), where v is the vector of reaction fluxes [12] [13].

The most widely used approach for simulating GEMs is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a linear programming technique that optimizes an objective function (typically biomass production) to predict flux distributions [12]. FBA identifies optimal flux distributions that maximize or minimize this objective while respecting network stoichiometry and other physiological constraints [12] [13].

GEM Reconstruction and Simulation Workflow

Multi-Scale and Context-Specific Model Architectures

As the field has advanced, classical GEMs have evolved into more sophisticated multi-scale models that incorporate additional biological constraints. Enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) integrate enzyme kinetic parameters and abundance data [9], while Metabolism and Expression models (ME-models) incorporate macromolecular processes including gene expression [8] [9]. For multicellular organisms, context-specific GEMs can be extracted to represent particular cell types, tissues, or strains using omics data [14].

Another significant advancement is the development of pan-genome scale models that capture metabolic diversity across multiple strains of a species. For example, pan-GEMs-1807 was built from 1,807 S. cerevisiae isolates, covering approximately 98% of genes in the CEN.PK strain and enabling the generation of strain-specific models [9]. Similar approaches have been applied to 55 E. coli strains, 410 Salmonella strains, and 64 S. aureus strains [8].

Comparative Analysis of Model Architectures

Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Different GEM architectures offer distinct advantages and limitations for various applications. The table below summarizes key architectures with their respective capabilities and validation metrics.

Table: Comparison of GEM Architectures and Performance

| Model Type | Key Features | Validation Accuracy | Computational Demand | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical GEM | Standard stoichiometry, GPR associations, FBA | 71-94% gene essentiality prediction in model organisms [11] [7] | Low | Metabolic engineering, phenotype prediction [7] |

| ecGEM | Enzyme kinetics, catalytic constraints | Improved prediction of proteome allocation [9] | Medium | Understanding enzyme usage, overflow metabolism [9] |

| ME-model | Integrated metabolism & gene expression | Accurate prediction of transcriptome & proteome [8] | High | Systems biology, cellular resource allocation [8] |

| Pan-GEM | Multiple strain variants, accessory genes | 85% growth prediction accuracy across 1,807 yeast strains [9] | Medium to High | Strain selection, evolutionary studies [8] [9] |

| Hybrid ML-GEM (FlowGAT) | FBA + graph neural networks | 接近FBA gold standard in E. coli [13] | High (training) Medium (prediction) | Gene essentiality prediction, biomarker discovery [13] |

Experimental Protocols for GEM Validation

Gene Essentiality Prediction Protocol:

- Model Constraint Setting: Define medium composition using measured substrate uptake rates [11]

- Gene Deletion Simulation: Set flux of reactions catalyzed by target gene to zero [11] [13]

- Growth Simulation: Perform FBA with biomass as objective function [11]

- Essentiality Classification: If growth rate decreases below threshold (typically <1% of wild-type), gene is classified as essential [11]

- Experimental Validation: Compare predictions with knockout fitness assays (e.g., CRISPR screens) [13]

Context-Specific Model Reconstruction (using mCADRE or INIT):

- Omics Data Collection: Obtain transcriptomic/proteomic data for specific tissue or condition [14]

- Reaction Scoring: Score metabolic reactions based on expression evidence [14]

- Network Extraction: Remove low-scoring reactions while maintaining network functionality [14]

- Gap Filling: Ensure biomass production and metabolic functionality [11]

- Validation: Compare predicted metabolic functions with experimental data [14]

Impact and Applications Across Industries

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

GEMs have revolutionized drug discovery, particularly for infectious diseases. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis, GEMs have identified potential drug targets by simulating the pathogen's metabolic state under in vivo hypoxic conditions and evaluating metabolic responses to antibiotic pressure [7]. Host-pathogen interaction models integrating M. tuberculosis GEMs with human alveolar macrophage models provide insights into infection mechanisms [7].

In the emerging field of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), GEMs guide the selection and design of therapeutic microbial strains. The AGORA2 resource, containing 7,302 curated strain-level GEMs of gut microbes, enables screening of strains for specific therapeutic functions [15]. GEMs can predict LBP interactions with resident microbes, production of beneficial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids for IBD), and potential side effects like antibiotic resistance gene transfer [15].

For human metabolism, GEMs have been reconstructed for 126 human tissues, enabling patient-specific metabolic modeling that integrates transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to identify disease mechanisms and potential drug targets [10] [14].

Diverse Applications of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

Industrial Biotechnology and Metabolic Engineering

GEMs have become indispensable tools for developing microbial cell factories. For Saccharomyces cerevisiae, multiple model versions have been optimized for predicting metabolic behavior under industrial conditions, enabling strain engineering for biofuel and chemical production [9]. The Yeast8 and Yeast9 models incorporate SLIME reactions, updated GPR associations, and thermodynamic parameters for enhanced prediction accuracy [9].

Similar successes have been achieved with non-model yeasts including Pichia pastoris, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Starmerella bombicola, where GEMs like iEM759 have guided metabolic engineering strategies coupling product synthesis with cellular growth [9]. For example, GEMs have been used to optimize production of sophorolipids in S. bombicola under high-sugar conditions [9].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for GEM Development and Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | Identifies metabolic genes and functions | RAST, ModelSEED [11] |

| Metabolic Databases | Provides reaction stoichiometry and metabolites | KEGG, MetaCyc, BiGG [12] |

| Reconstruction Tools | Automates draft model generation | RAVEN, CarveFungi, ModelSEED [9] |

| Simulation Platforms | Performs FBA and related analyses | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python) [12] |

| Optimization Solvers | Mathematical optimization | GUROBI, CPLEX [11] |

| Model Testing | Validates model quality and predictions | MEMOTE [11] |

The field of genome-scale metabolic modeling continues to evolve rapidly. Emerging areas include the integration of machine learning approaches like graph neural networks with GEMs, as demonstrated by FlowGAT for gene essentiality prediction [13]. There is also growing emphasis on multi-omics integration, incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create context-specific models [14].

The expansion of microbial community modeling represents another frontier, enabling the simulation of complex metabolic interactions in microbiomes [8] [15]. As the scale and resolution of omics technologies continue to advance, GEMs are poised to become increasingly accurate and comprehensive, further solidifying their role as indispensable tools in biomedical research and industrial biotechnology.

The rise of GEMs has fundamentally transformed metabolic research, providing a powerful framework for integrating genomic information with physiological outcomes. From their beginnings with single microorganisms to current applications in human health and complex ecosystems, GEMs have demonstrated remarkable versatility and predictive power across diverse biological systems.

The quest to understand, predict, and optimize cellular metabolism relies heavily on mathematical modeling. Two dominant frameworks have emerged: Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) and Dynamic Kinetic Modeling. They represent fundamentally different philosophies for tackling the complexity of metabolic networks. The COBRA framework uses stoichiometric constraints and an assumption of steady-state operation to predict metabolic fluxes, making it highly scalable for genome-scale analyses [16] [17]. In contrast, dynamic kinetic modeling employs systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the time evolution of metabolite concentrations based on enzyme kinetics and regulatory mechanisms, offering detailed, time-resolved insights at the cost of greater parametric demands [16] [18]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these core frameworks, detailing their theoretical foundations, practical applications, and performance, framed within the broader thesis of evaluating model architectures for metabolic research.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

The COBRA Framework: Predicting Phenotypes from Stoichiometry

The COBRA approach is built upon the physicochemical constraints that inherently govern metabolic network behavior. Its core principle is that the stoichiometric matrix (S), which encodes the mass balance of all metabolic reactions, defines the space of all possible flux distributions (denoted by vector v).

The fundamental equation is: [ S \cdot v = 0 ] This equation represents the steady-state assumption, where the production and consumption of every internal metabolite are balanced [17]. The solution space for v is further constrained by lower and upper bounds ((v{lb} \leq v \leq v{ub})) that incorporate enzyme capacity and reaction directionality [19]. As this system is typically underdetermined, an objective function (e.g., biomass maximization) is optimized to find a single, biologically relevant flux distribution [16]. This formulation, known as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), is a linear programming problem. Extensions like dynamic FBA (dFBA) apply FBA sequentially to simulate time-course behaviors in batch or fed-batch cultures by using ODEs for extracellular metabolites and biomass, while retaining the steady-state assumption for intracellular metabolism at each time point [20].

Diagram 1: The COBRA/FBA Workflow. The process begins with network reconstruction and culminates in a flux prediction by solving a linear optimization problem under constraints.

Dynamic Kinetic Modeling: Capturing Metabolic Dynamics

Dynamic kinetic models explicitly describe the temporal changes in metabolite concentrations. The state of the system is given by a vector of metabolite concentrations (x), and its dynamics are governed by a system of ODEs: [ \frac{d\textbf{x}}{dt} = F(k, \textbf{x}(t)) ] Here, the function F is determined by the stoichiometry and the kinetic rate laws (e.g., Michaelis-Menten) of each reaction, and k is a vector of kinetic parameters (e.g., (k{cat}), (KM)) [18]. Unlike COBRA, kinetic models do not assume steady-state for internal metabolites and can incorporate allosteric regulation and detailed enzyme mechanisms [18] [21]. This allows them to simulate transient behaviors, such as metabolic responses to perturbations or nutrient shifts. However, constructing these models is challenging due to the frequent lack of known kinetic mechanisms and parameters, leading to the use of ensemble modeling and Monte Carlo sampling approaches to explore feasible parameter sets consistent with experimental data [22] [23].

Diagram 2: Dynamic Kinetic Modeling Workflow. The process involves specifying kinetic equations and parameters, followed by numerical simulation of ODEs, often with iterative validation.

Quantitative Comparison of Framework Performance

Table 1: High-level comparison of the COBRA and Dynamic Kinetic Modeling frameworks.

| Feature | COBRA/Constraint-Based | Dynamic Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mathematical Formulation | Linear/Quadratic Programming | Systems of Nonlinear ODEs |

| Primary Output | Steady-state flux distribution | Metabolite concentrations over time |

| Timescale | Steady-state or pseudo-steady-state | Transient and steady-state dynamics |

| Typical Network Scale | Genome-scale (1,000s of reactions) | Pathway-scale (10s-100s of reactions) |

| Key Data Requirements | Stoichiometry, reaction bounds, objective function | Kinetic parameters (e.g., (KM), (V{max})), rate laws, initial concentrations |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Ensemble modeling, Monte Carlo sampling |

| Computational Demand | Generally low (linear programming) | High (numerical integration of ODEs) |

Performance in Predictive Tasks

Table 2: Quantitative performance of frameworks in common metabolic modeling tasks.

| Modeling Task / Metric | COBRA/Constraint-Based | Dynamic Kinetic Modeling | Experimental Data & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shikimic Acid Production in E. coli | dFBA predicted theoretical maximum yield [20] | N/A | Experimental strain achieved ~84% of dFBA-predicted maximum in batch culture [20] |

| Incidence of Physiologically Relevant Models | N/A | As low as <1% for large-scale stable models before filtering; REKINDLE method increased yield to >97% [22] | Based on generation of kinetic models for E. coli central carbon metabolism matching observed dynamics [22] |

| Strain Design Optimization | Successfully identifies gene knockout strategies; may overpredict yield by ignoring kinetics [16] | Better predicts outcomes of engineering; identifies flux and concentration controls [24] | MCA on kinetic models showed engineering decisions are highly sensitive to assumed metabolite concentrations [24] |

| Representation of Regulation | Limited (requires extensions like rFBA); indirect via constraints | Direct, through allosteric regulation and signaling in rate laws [18] | Kinetic models can explicitly simulate the impact of effectors on enzyme activity and pathway flux. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic FBA for Production Strain Evaluation

This protocol, as applied to shikimic acid production in E. coli [20], details how to use dFBA to benchmark the performance of an engineered strain against its theoretical potential.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Approximation: Extract time-course experimental data for key extracellular variables (e.g., glucose concentration) and biomass from the literature or experiments. Approximate these data using polynomial regression to obtain continuous functions, (Glc(t)) for glucose and (X(t)) for biomass.

- Constraint Calculation: Differentiate the approximation functions with respect to time to calculate the specific glucose uptake rate and the specific growth rate at any time (t). For example: [ v_{uptake_Glc}^{approx}(t) = \frac{- \frac{dGlc(t)}{dt}}{X(t)} ]

- Dynamic Simulation: Discretize the cultivation time. At each time step, perform a standard FBA simulation where the objective is to maximize the production flux of the target compound (e.g., shikimic acid). The calculated specific uptake rate from the previous step is used as the constraint for the glucose exchange reaction at that specific time point.

- Integration and Evaluation: Numerically integrate the predicted production flux over the cultivation time to obtain the total simulated maximum product concentration. Compare this value to the actual experimental product titer to evaluate the strain's performance (e.g., experimental titer / simulated maximum titer × 100%).

Protocol 2: Generating Ensembles of Kinetic Models with REKINDLE

This protocol uses the REKINDLE framework, which employs Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to efficiently generate kinetic models with desirable dynamic properties [22].

Methodology:

- Initial Sampling and Labeling: Use a traditional kinetic modeling framework (e.g., ORACLE) to perform Monte Carlo sampling of the kinetic parameter space. Simulate the dynamic behavior of each parameterized model and label each set as "biologically relevant" or "not relevant" based on predefined criteria (e.g., model stability and agreement with experimentally observed response times).

- GAN Training: Train a conditional GAN on the labeled dataset. The generator network learns to map random noise to kinetic parameter sets, while the discriminator network learns to distinguish between "real" relevant parameter sets from the training data and "fake" ones produced by the generator. This process is conditioned on the "biologically relevant" label.

- Model Generation and Validation: Use the trained generator to produce new kinetic parameter sets. Validate the generated models by ensuring they are statistically similar to the training data (e.g., using Kullback-Leibler divergence) and by confirming that they satisfy the desired dynamic properties through linear stability analysis (e.g., checking that the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix have negative real parts).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key software tools and resources for implementing COBRA and kinetic modeling frameworks.

| Tool Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Framework | Reference/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A comprehensive MATLAB suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. | COBRA | [19] |

| COBRApy | An open-source Python package that recapitulates and extends the functions of the COBRA Toolbox. | COBRA | [17] [21] |

| DFBAlab | A MATLAB tool for efficiently solving dynamic FBA problems. | COBRA (dFBA) | [20] |

| MASSpy | A Python package for building, simulating, and visualizing dynamic metabolic models using mass action kinetics. | Kinetic / Hybrid | [21] |

| SKiMpy / ORACLE | A toolbox for constructing large-scale kinetic models and performing sampling and optimization. | Kinetic | [22] |

| REKINDLE | A deep-learning (GAN) framework for efficiently generating kinetic models with tailored dynamic properties. | Kinetic | [22] |

| libRoadRunner | A high-performance simulation engine for SBML models, used by tools like MASSpy for ODE solving. | Kinetic | [21] |

| Escher | A web-based tool for visualizing pathways and overlaying omics data on metabolic maps. | Visualization | [21] |

Integrated and Hybrid Approaches

Recognizing the complementary strengths of both frameworks, researchers are developing hybrid methods. MASSpy is a prime example, built upon COBRApy to provide a unified framework that integrates constraint-based and kinetic modeling [21]. It allows for the construction of dynamic models with detailed enzyme mechanisms while leveraging the network curation and steady-state analysis tools of the COBRA ecosystem. Another strategy involves using steady-state fluxes and metabolite concentrations from COBRA models as a scaffold around which to build kinetic models, though this must account for the uncertainty in these values [24] [18]. These integrated approaches aim to balance scalability with dynamical insight, representing a promising future direction for metabolic modeling.

Diagram 3: A Hybrid Modeling Workflow. Steady-state solutions from COBRA models are used to inform and parameterize populations of kinetic models, leveraging the strengths of both frameworks.

In the field of metabolic modeling, genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a systemic overview of an organism's metabolic potential, embracing all available knowledge about biochemical transformations within a cell or organism [25] [26]. The functional integrity and predictive power of these models rest upon two fundamental components: Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) associations and biomass formulations. These building blocks enable researchers to translate genomic information into actionable metabolic insights, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype.

GPR rules describe the Boolean logic relationships between gene products—such as enzyme isoforms or subunits—associated with catalyzing specific metabolic reactions [25] [26]. These rules use AND operators to connect genes encoding different subunits of the same enzyme complex and OR operators to join genes encoding distinct protein isoforms that can alternatively catalyze the same reaction [26]. Meanwhile, biomass formulations quantitatively define the biosynthetic requirements for cellular growth, representing the drain of metabolites toward producing new cellular components. Together, these elements enable critical applications from gene essentiality analysis to prediction of metabolic phenotypes under varying genetic and environmental conditions [27] [28].

This guide objectively compares alternative approaches for reconstructing GPR associations and formulating biomass objectives, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating these core components within metabolic network architectures.

GPR Associations: From Manual Curation to Automated Reconstruction

The Critical Role of GPR Rules in Metabolic Models

GPR associations provide the crucial link between an organism's genotype and its metabolic phenotype. In GEMs, these Boolean rules define how gene products combine to catalyze metabolic reactions, enabling critical analyses including gene deletion simulations, integration of transcriptomic data, and identification of essential genes [25] [28]. Without accurate GPR rules, metabolic models cannot reliably predict the metabolic consequences of genetic perturbations or explain how multiple genes can encode isozymes and enzyme complexes that collectively determine reaction fluxes.

The complexity of biological systems presents significant challenges for GPR reconstruction. Enzymes may exist as monomeric entities (single gene → single protein) or oligomeric complexes (multiple genes → single functional enzyme), while multiple isozymes (different proteins → same function) may catalyze the same reaction [26]. Furthermore, promiscuous enzymes (one protein → multiple functions) can participate in multiple reactions. This biological complexity necessitates sophisticated logical representations that accurately capture genetic constraints on metabolic capabilities.

Comparative Analysis of GPR Reconstruction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of GPR Rule Reconstruction Tools and Approaches

| Method/Tool | Primary Data Sources | Automation Level | Boolean Logic | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPRuler | 9 biological databases including UniProt, Complex Portal, KEGG, MetaCyc [25] [26] | Fully automated | Complete AND/OR rules | Open-source, applicable to any organism, high accuracy in benchmarks | - |

| Manual Curation | Literature, biochemical evidence, genome annotations [26] | Fully manual | Complete AND/OR rules | High-quality, evidence-based | Time-consuming, not scalable |

| RAVEN Toolbox | KEGG, genome annotations [26] | Semi-automated | Gene-reaction associations without Boolean operators | Part of broader reconstruction pipeline | Requires manual curation for Boolean logic |

| SimPheny | BLASTP against existing models [26] | Semi-automated | Draft Boolean rules | - | Closed source, requires intensive manual revision |

| merlin | KEGG BRITE, KEGG ORTHOLOGY [26] | Fully automated | Complete AND/OR rules | User-friendly graphical interface | Limited to single data source |

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that automated tools can achieve high accuracy in GPR reconstruction. When evaluated against manually curated models for Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, GPRuler reproduced original GPR rules with high accuracy, and in many mismatched cases, the tool proved more accurate than the original models upon manual investigation [25] [29]. This suggests that automated approaches have reached maturity sufficient for reliable draft reconstruction, though manual refinement may still be necessary for mission-critical applications.

Experimental Protocols for GPR Validation

Gene Essentiality Prediction Protocol:

- Reaction Deactivation: For each gene knockout, constrain reactions associated with that gene to zero flux based on GPR rules [27]

- Growth Simulation: Perform flux balance analysis with biomass maximization objective [27] [28]

- Growth Prediction: Classify genes as essential if simulated growth rate falls below threshold (typically 1-5% of wild-type) [27]

- Experimental Comparison: Compare predictions to experimental gene essentiality data from knockout libraries (e.g., TnSeq, BarSeq) [27]

- Mismatch Resolution: Identify and correct GPR errors when predictions contradict experimental evidence [27]

Transcriptomic Data Integration Protocol:

- Expression Mapping: Convert transcriptomic data to enzyme activity levels using expression thresholds [28]

- Model Constraining: Limit reaction fluxes based on GPR rules and expression-dependent enzyme capacities [28]

- Context-Specific Model Extraction: Generate condition-specific models using algorithms that integrate expression data with GPR rules [25]

- Phenotype Prediction: Simulate metabolic fluxes under the specified transcriptomic constraints [28]

- Validation: Compare predicted growth phenotypes and metabolic capabilities to experimental observations [28]

GPR Logical Relationships: This diagram illustrates how genes encode proteins that assemble into complexes (AND logic) or function as isozymes (OR logic) to enable metabolic reactions.

Biomass Formulations: Quantifying Cellular Growth Requirements

The Biomass Objective Function in Metabolic Modeling

The biomass objective function represents the drain of metabolic precursors toward synthesizing all essential cellular components required for growth. This formulation typically includes amino acids for protein synthesis, nucleotides for DNA and RNA, lipid precursors for membrane formation, carbohydrates for cell wall structures, and various cofactors and ions [27]. The biomass reaction serves as the primary optimization target in most flux balance analyses, simulating the biological objective of growth maximization [27] [28].

Accurate biomass formulation is particularly challenging because cellular composition varies significantly across organisms and growth conditions. The biomass objective must reflect these differences to generate biologically relevant predictions. While early metabolic models used simplified biomass representations, contemporary approaches increasingly incorporate condition-specific and tissue-specific biomass compositions to improve predictive accuracy [27].

Comparative Analysis of Biomass Estimation Techniques

Table 2: Comparison of Biomass Estimation Methods in Metabolic Modeling

| Method | Measurement Requirements | Implementation Complexity | Quantitative Accuracy | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Model-Based | Nutrient uptake rates, stoichiometric coefficients [30] | High | Variable, depends on kinetic parameters | Well-characterized organisms with extensive experimental data |

| Metabolic Black-Box Model | Online substrate uptake rates, offline biomass measurements [30] | Medium | High (closely matches offline measurements) | Industrial fermentation processes with fluctuating inputs |

| Asymptotic Observer | Online gas analysis (CO₂, O₂), substrate feeding rates [30] | Medium | Moderate to high | Large-scale fermentation with limited online biomass measurements |

| Artificial Neural Network | Historical process data for training [30] | High | High (after sufficient training) | Processes with complex nonlinear relationships between variables |

| Differential Evolution | Multiple online measurements [30] | High | Good convergence to measurements | Optimization of fed-batch fermentation processes |

Experimental comparisons of these methods using industrial-scale yeast fermentation data reveal important performance trade-offs. The metabolic black-box model approach most closely matched offline biomass measurements across different fermentation types, while mechanistic models showed higher sensitivity to initial conditions and fermentation characteristics [30]. When evaluated by implementation requirements, neural networks and metabolic black-box models required the fewest direct measurements, whereas differential evolution needed the most comprehensive measurement suite [30].

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Formulation

Biomass Composition Determination Protocol:

- Cellular Component Quantification: Experimentally measure cellular amounts of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, DNA, and RNA [27]

- Macromolecular Breakdown: Determine precise compositions of each macromolecule (e.g., amino acid composition of proteins, fatty acid composition of lipids) [27]

- Energy Requirements: Calculate ATP requirements for macromolecular polymerization and assembly [27]

- Stoichiometric Formulation: Construct balanced biomass equation incorporating all cellular components [27]

- Model Integration: Incorporate biomass reaction as primary objective function in constraint-based model [27]

Growth Rate Prediction Validation Protocol:

- Experimental Cultivation: Grow organism in defined medium under controlled conditions [27]

- Growth Rate Measurement: Quantify growth rates through optical density, cell counting, or dry weight measurements [30]

- In Silico Simulation: Predict growth rates using flux balance analysis with biomass objective [27]

- Statistical Comparison: Calculate correlation between predicted and measured growth rates across conditions [27]

- Model Refinement: Adjust biomass composition and maintenance costs to improve prediction accuracy [27]

Biomass Synthesis Pathway: This diagram illustrates how nutrients are processed through metabolic networks to generate biomass components that collectively define the biomass objective function.

Integrated Workflow: From Genomic Data to Phenotypic Prediction

Unified Framework for Model Reconstruction and Validation

The integration of accurate GPR rules with quantitatively precise biomass formulations enables robust phenotypic predictions from genomic information. The following workflow represents current best practices for metabolic model development and application:

Model Reconstruction Workflow: This diagram outlines the integrated process for reconstructing metabolic models, combining GPR rule reconstruction with biomass formulation to enable predictive simulations.

Performance Benchmarks and Validation Metrics

Model validation remains essential for establishing predictive credibility. For GPR rules, gene essentiality predictions typically achieve 83-95% accuracy when compared to experimental data for well-characterized organisms like Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Bacillus subtilis [27]. Discrepancies between predictions and experiments often reveal gaps in metabolic networks or incorrect GPR assignments, providing opportunities for model refinement [27].

For biomass formulations, prediction accuracy is typically assessed by comparing simulated growth rates to experimental measurements across different nutrient conditions. State-of-the-art models successfully predict nutrient utilization capabilities and secretion products, with more sophisticated biomass formulations demonstrating improved correspondence with quantitative physiological measurements [27].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GPR and Biomass Research

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Databases | UniProt, KEGG, MetaCyc, Complex Portal [25] [26] | Source protein complex data, metabolic pathways, and functional annotations | GPR rule reconstruction and validation |

| Computational Tools | GPRuler, RAVEN Toolbox, merlin [25] [26] | Automate GPR reconstruction from genomic data | Draft model reconstruction for non-model organisms |

| Constraint-Based Modeling | COBRA Toolbox, ModelSEED, CarveMe [27] [28] | Simulate metabolic fluxes and predict phenotypic outcomes | Strain design, gene essentiality analysis |

| Experimental Validation | TnSeq, BarSeq mutant libraries [27] | High-throughput gene essentiality determination | GPR rule validation and refinement |

| Analytical Techniques | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR [27] | Quantitative metabolomics and biomass composition analysis | Biomass formulation refinement |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that strategic selection of GPR reconstruction methods and biomass formulation approaches significantly impacts predictive accuracy in metabolic modeling. Automated GPR reconstruction tools like GPRuler provide scalable solutions for non-model organisms while maintaining competitive accuracy with manual curation [25] [26]. For biomass formulation, metabolic black-box models and asymptotic observers offer distinct advantages for industrial applications with limited measurements [30].

The ongoing integration of diverse biological data sources—from protein complex databases to mutant fitness assays—continues to enhance the resolution and predictive power of both GPR rules and biomass formulations. As metabolic modeling expands into complex areas such as microbial communities and human diseases, these fundamental building blocks will remain essential for translating genomic information into mechanistic understanding of metabolic phenotypes.

In the field of systems biology, computational modeling of metabolic networks has become an indispensable approach for investigating the underlying principles of cellular growth, metabolic engineering, and drug target identification [31]. The reconstruction and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) depend critically on access to high-quality biochemical databases and standardized model exchange formats. Among the numerous resources available, BioCyc and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) have emerged as two foundational database collections, while SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) serves as the primary standard for model representation and exchange [31] [32] [33]. These resources employ fundamentally different architectural philosophies: BioCyc provides organism-specific pathway/genome databases (PGDBs) with tiered quality levels, whereas KEGG offers manually drawn reference pathway maps that can be organism-specific through gene identifier mapping [34] [32]. This comparative analysis examines the technical architectures, data curation approaches, and practical applications of these resources within the context of metabolic modeling research, providing experimental protocols and quantitative comparisons to guide researchers in selecting appropriate tools for their specific investigations.

Architectural Frameworks and Database Structures

BioCyc: A Tiered Collection of Pathway/Genome Databases

The BioCyc collection represents a comprehensive infrastructure for electronic reference sources on pathways and genomes of diverse organisms, primarily microbial, though it also includes important model eukaryotes and humans [34]. Its architecture is characterized by a three-tiered system that reflects varying degrees of manual curation:

- Tier 1: Databases receiving intensive manual curation and continuous updating, including EcoCyc (Escherichia coli K-12), MetaCyc (experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways from multiple organisms), HumanCyc, YeastCyc (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), and AraCyc (Arabidopsis thaliana) [34].

- Tier 2: Approximately 80 computationally generated databases created by the PathoLogic program that have undergone moderate manual review and updating [34].

- Tier 3: Over 19,000 computationally generated databases that have received no manual review, providing draft metabolic reconstructions for a vast array of sequenced genomes [34].

A key architectural feature of BioCyc is its ortholog computation methodology, which employs Diamond (version 2.0.4) for sensitive sequence comparisons with an E-value cutoff of 0.001, defining orthologs as bidirectional best hits between proteomes [34]. This approach facilitates comparative analyses across the entire collection. The pathway boundary definition in BioCyc contrasts sharply with KEGG's approach; BioCyc pathways are typically smaller, more biologically coherent units bounded by common currency metabolites, whereas KEGG maps are on average 4.2 times larger because they group multiple biological pathways that converge on single metabolites [34].

KEGG: Reference Pathway Maps and Orthology-Based Mapping

KEGG employs a significantly different architectural philosophy centered on manually drawn reference pathway maps that represent molecular interaction and reaction networks [32]. These maps serve as templates that can be customized for specific organisms through identifier mapping:

- Reference Pathways: Manually curated maps identified by prefixes including 'map' (reference pathway), 'ko' (highlighting KEGG Orthology groups), 'ec' (highlighting EC numbers), and 'rn' (highlighting reactions) [32].

- Organism-Specific Pathways: Generated by converting KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers to organism-specific gene identifiers, denoted by organism code prefixes [32].

- Classification Hierarchy: Pathways are organized into a hierarchical classification system encompassing metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, cellular processes, organismal systems, human diseases, and drug development [32].

KEGG's pathway representation is primarily visualization-oriented, originally designed for illustrative purposes rather than computational modeling [35]. This orientation creates challenges for simulation purposes, as KGML (KEGG Markup Language) files do not include kinetic information and may contain biochemical inconsistencies due to visualization priorities, such as duplicate compounds that disrupt stoichiometric calculations [35].

SBML: The Interoperability Standard for Model Exchange

SBML functions as the critical interoperability layer that enables exchange of models between different software tools and databases. Unlike BioCyc and KEGG, which are primarily data resources, SBML is a model representation format with these key characteristics:

- Standardized XML Format: SBML represents models using a structured XML format that can encode biochemical reactions, parameters, and mathematical relationships [36].

- Layout and Render Packages: These SBML extensions enable standardized visualization of biochemical models, storing positioning and styling information together with model data in a single file [36].

- Community-Driven Development: SBML is maintained by elected editors and developed through community consensus, with current editors representing leading institutions in computational biology [33].

The SBMLNetwork tool addresses previous limitations in utilizing the Layout and Render specifications by providing a force-directed auto-layout algorithm enhanced with biochemistry-specific heuristics, making standards-based visualization more accessible [36]. This tool represents reactions as hyper-edges anchored to centroid nodes and draws connections as role-aware Bézier curves that preserve reaction semantics while minimizing edge crossings [36].

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison of BioCyc, KEGG, and SBML

| Feature | BioCyc | KEGG | SBML |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Organism-specific metabolic networks | Reference pathway maps | Model representation and exchange |

| Data Structure | Tiered PGDBs | Reference maps with organism-specific mapping | XML-based model format |

| Pathway Boundaries | Biologically coherent units | Larger composite maps | User-defined in imported models |

| Curation Approach | Mix of manual and computational | Manual for reference maps | Format specification, not content curation |

| Orthology Method | Bidirectional best hits (Diamond) | KEGG Orthology (KO) groups | Not applicable |

| Visualization | Cellular overview diagrams | Manually drawn pathway maps | SBML Layout and Render packages |

Quantitative Comparison of Database Content and Coverage

Scope and Scale Assessment

The BioCyc collection has experienced substantial growth over time, expanding from 376 PGDBs in 2005 to 20,077 PGDBs in 2025, demonstrating a massive scale-up to accommodate the increasing number of sequenced genomes [37]. This expansion reflects its comprehensive coverage of microbial genomes alongside key model eukaryotes. KEGG does not explicitly report its total number of organism-specific pathway maps in the search results, but its systematic classification system encompasses seven major categories with numerous subcategories, suggesting extensive coverage of biological processes [32].

In terms of pathway definition philosophy, quantitative analysis reveals that KEGG maps are approximately 4.2 times larger on average than BioCyc pathways because KEGG tends to group multiple biological pathways that converge on single metabolites into composite maps [34]. This fundamental difference in pathway granularity has significant implications for computational modeling and biological interpretation.

Content Quality Indicators

The tiered structure of BioCyc enables transparent communication of data quality expectations for users:

- Tier 1 Databases: These undergo continuous manual curation, with EcoCyc receiving regular updates including characterization of previously unannotated genes, addition of post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and new metabolic reactions [37].

- Tier 2 Databases: These benefit from targeted curation efforts, such as the recent addition of a manually curated PGDB for Vibrio natriegens ATCC 14048, which received ortholog propagation from the curated Vibrio cholerae database and upgrades to central metabolic enzymes and pathways [37].

- Tier 3 Databases: While generated computationally without manual review, these still provide valuable draft metabolic networks for little-studied organisms [34].

KEGG's quality approach relies on manual curation of reference maps, which are considered highly reliable, though the automatic generation of organism-specific pathways through orthology mapping may propagate annotation errors [35]. The KEGGconverter tool acknowledges limitations in KEGG data for modeling, noting that KGML files may contain duplicate compounds and reactions that disrupt biochemical consistency for simulation purposes [35].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Database Content and Features

| Characteristic | BioCyc | KEGG | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Databases/Pathways | 20,077 PGDBs (2025) | Not explicitly quantified | [37] |

| Organism Coverage | Primarily microbial, plus key eukaryotes | All domains of life | [34] [32] |

| Pathway Granularity | Smaller, biologically coherent units | Composite maps (4.2× larger on average) | [34] |

| Update Frequency | Every 6-12 months for computational PGDBs | Not specified | [34] |

| Orthology Computation | Diamond (v2.0.4), E-value < 0.001, bidirectional best hits | KEGG Orthology (KO) system | [34] [32] |

| Manual Curation | Tier-dependent: Intensive for Tier 1, none for Tier 3 | For reference pathways only | [34] |

| Metabolic Modeling Support | Direct export of metabolic networks | Requires conversion and correction | [31] [35] |

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization in Metabolic Modeling

Protocol 1: Reconstruction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models Using BioCyc and moped

The moped Python package provides a reproducible workflow for constructing metabolic models directly from BioCyc databases, demonstrating how BioCyc's structured data can be leveraged for computational modeling [31]:

Data Import: Import metabolic network data from BioCyc PGDB flat files or existing models in SBML format. PGDBs contain annotated reactions and compounds with detailed information including sum formulas, charges, and subcellular localization [31].

Network Expansion Analysis: Perform metabolic network expansion to investigate structural properties and biosynthetic capacities. This algorithm computes the metabolic scope - all compounds producible from a given initial set of seed compounds through iterative application of metabolic reactions [31].

Cofactor and Reversibility Handling: Apply specialized methods for biologically meaningful expansion:

- Reversibility Duplication: Identify all reversible reactions and add reversed versions to the network with the suffix '_rev' [31].

- Cofactor Duplication: Duplicate reactions involving cofactor pairs (e.g., ATP/ADP, NAD+/NADH) with 'mock cofactors' (suffix '_cof') to allow cofactor-dependent reactions to proceed without unrealistic constraints while maintaining metabolic fidelity [31].

Gap Filling: Use topological gap-filling tools like Meneco to identify and add missing reactions necessary to achieve metabolic functionality observed experimentally [31].

Model Export: Export the curated model as a CobraPy object for constraint-based analysis or as SBML for sharing and further integration [31].

Protocol 2: Integration of KEGG Pathways for Simulation with KEGGconverter

The KEGGconverter tool addresses specific challenges in transforming KEGG pathway data into simulation-capable models, implementing a multi-stage biochemical correction process [35]:

KGML Acquisition: Obtain KGML files for target pathways from the KEGG database. KGML provides graph information for computational reproduction of KEGG pathway maps but lacks kinetic information and contains visualization-driven redundancies [35].

Pathway Merging: Concatenate entries, relations, and reaction elements from multiple KGML files into a single file, modifying ID attributes to indicate source files and removing redundant inter-pathway relations [35].

SBML Conversion: Transform the merged KGML file to SBML format through a two-stage process:

Biochemical Consistency Resolution: Address KEGG-specific issues that affect simulation validity:

Kinetic Law Addition: Incorporate default kinetic equations to enable dynamic simulations, as KGML files lack rate law information [35].

Protocol 3: Database Reconciliation and Model Curation for Zymomonas mobilis

A comprehensive reconciliation of genome-scale metabolic models for Zymomonas mobilis ZM4 demonstrates practical integration of multiple database resources and computational tools [38]:

Draft Network Assembly: Compile metabolic network components from previously published GEMs and core metabolic networks, identifying and resolving inconsistencies in metabolite names, reaction abbreviations, and stoichiometric errors [38].

Gene-Protein-Reaction Association Enhancement:

Gap Analysis and Filling:

- Identify no-production and no-consumption metabolites representing knowledge gaps

- Use computational tools like fastGapFill and GapFind to propose biologically relevant missing reactions [38]

- Manually evaluate proposed gap-filling reactions using genomic and biochemical evidence

Directionality and Thermodynamic Validation:

- Determine reaction reversibility based on BioCyc and KEGG annotations, resolving discrepancies through literature search [38]

- Add spontaneous reactions confirmed experimentally in model organisms

Model Validation and Testing:

- Compare simulation results with experimental growth data under various conditions

- Perform gene essentiality analysis to test predictive capability

- Validate against gene expression data from different environmental conditions [38]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioCyc PGDBs | Database | Organism-specific metabolic pathway data | Source of curated metabolic reconstructions for target organisms [34] |

| KEGG Pathway | Database | Reference metabolic maps and orthology | Comparative analysis and initial pathway identification [32] |

| SBML | Format Standard | Model representation and exchange | Interoperability between different modeling tools and databases [33] |

| moped | Python Package | Metabolic model construction and curation | Reproducible model reconstruction from BioCyc databases [31] |

| KEGGconverter | Software Tool | KGML to SBML conversion with biochemical correction | Creating simulation-ready models from KEGG pathways [35] |

| Pathway Tools | Software Suite | PGDB creation, curation, and analysis | Generating and maintaining BioCyc databases [34] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB Package | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Flux balance analysis and metabolic network optimization [38] |

| libSBML | Programming Library | SBML reading, writing, and manipulation | Low-level access to SBML structures in custom applications [33] |

| SBMLNetwork | Software Library | Standards-based visualization of biochemical models | Creating SBGN-compliant visualizations with SBML Layout/Render [36] |

| Meneco | Software Tool | Topological network gap-filling | Identifying missing reactions in draft metabolic networks [31] |

The comparative analysis of BioCyc, KEGG, and SBML reveals distinctive strengths and applications for each resource in metabolic modeling research. BioCyc excels in providing organism-specific metabolic reconstructions with transparent quality stratification through its tiered system, making it particularly valuable for detailed organism-specific investigations and comparative analyses across multiple species. The moped package further enhances its utility by enabling reproducible model construction directly from BioCyc databases [31]. KEGG offers comprehensive coverage of biological processes through its manually curated reference pathways, though its visualization-oriented architecture requires significant correction for biochemical consistency in computational modeling [35]. SBML serves as the essential interoperability standard that enables integration and exchange of models across different platforms and tools, with ongoing development focused on enhancing visualization capabilities through the Layout and Render packages [36] [33].

Strategic selection of these resources depends on specific research objectives: BioCyc is optimal for organism-specific metabolic modeling and comparative genomics; KEGG provides valuable pathway context and orthology-based mapping across diverse organisms; and SBML enables model sharing, integration, and reproducibility across the systems biology community. As metabolic modeling continues to evolve toward more comprehensive and multiscale representations, the complementary strengths of these resources will remain essential for advancing our understanding of cellular physiology and optimizing metabolic engineering applications.

Strategic Model Selection and Application in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Discovery

Selecting the optimal computational model is a critical step in metabolic modeling research. The architecture of a model determines its ability to answer specific biological questions, from elucidating metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer to optimizing microbial production of chemicals. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary model architectures, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to help researchers match the right tool to their scientific inquiry.

Model architectures in metabolic research span from mechanistic, constraint-based models to purely data-driven machine learning (ML) approaches, and increasingly, hybrid systems that integrate both. Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) provide a structured network of biochemical reactions and have been powerful tools for over two decades [39]. More recently, ML techniques like random forests and XGBoost have been applied to identify complex patterns and biomarkers from high-throughput omics data [40] [41]. The emerging class of hybrid architectures, such as Metabolic-Informed Neural Networks (MINNs), embeds mechanistic knowledge from GEMs into neural networks, aiming to leverage the strengths of both approaches [42]. The choice between these paradigms depends heavily on the biological question, data availability, and desired interpretability.

Comparative Analysis of Model Architectures

The table below summarizes the core architectural features, performance characteristics, and ideal use cases for the primary model types discussed in recent literature.

Table 1: Architecture Comparison for Metabolic Modeling

| Model Architecture | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Experimental Results | Ideal for Biological Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEM) with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Constraint-based modeling using linear programming to predict steady-state reaction fluxes [39]. | Prediction accuracy of growth rates, metabolite production/consumption rates [39]. | Successfully applied to identify metabolic vulnerabilities in lung cancer and mast cells [40]; widely used for microbial strain design [39] [43]. | Predicting systemic metabolic flux distributions; identifying essential genes/reactions; in silico strain design. |