Balancing Metabolic Flux: A Pathway Engineering Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on balancing metabolic flux through advanced pathway engineering.

Balancing Metabolic Flux: A Pathway Engineering Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on balancing metabolic flux through advanced pathway engineering. It covers the foundational principles of metabolic flux analysis, explores cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for flux quantification, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing pathway bottlenecks, and discusses frameworks for validating and comparing strain designs. By integrating insights from constraint-based modeling, isotope tracing, and combinatorial optimization, this resource aims to equip professionals in drug development and biomedical research with the tools to rationally engineer efficient microbial cell factories for the production of valuable chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

Understanding Metabolic Flux: Core Principles and Network Analysis

Defining Metabolic Flux and Its Role as a Determinant of Cell Physiology

Core Concept: What is Metabolic Flux?

Metabolic flux is defined as the rate of turnover of molecules through a metabolic pathway. It is the movement of matter through metabolic networks that are interconnected by metabolites and cofactors. In practical terms, it represents the flow of metabolites through the biochemical pathways within a cell [1].

Think of metabolic flux like the flow of traffic on a network of roads. The overall movement of vehicles (metabolites) from origin to destination is determined by the combined activity and capacity of all the interconnected roads (enzymatic reactions) in the network [2]. This flux is regulated by the enzymes involved in a pathway and is vital for all metabolic pathways to regulate their activity under different conditions [1].

Why is Metabolic Flux a Central Concept?

Metabolic fluxes are considered the ultimate representation of the cellular phenotype [3]. They provide integrative information because they are the final outcome of cellular regulation at many different levels, including gene expression, translation, post-translational protein modifications, and protein-metabolite interactions [3]. While other 'omics' technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) describe the cellular potential, fluxomics describes the actual metabolic activities occurring in the cell [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I directly predict metabolic fluxes from mRNA expression data? A: mRNA expression alone is often a poor predictor of metabolic flux due to complex post-transcriptional regulation. Studies in yeast have shown that while mRNA levels may change significantly under stress, the correlation with actual flux changes can be very low (e.g., r = 0.07) [5]. Metabolic control involves multiple layers beyond transcription, including:

- Translational regulation

- Post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation)

- Allosteric regulation by metabolites

- Protein-metabolite interactions

Integrating network-based models that include metabolite-enzyme interactions can dramatically improve the correlation between mRNA and flux data [5].

Q2: What is the fundamental assumption when calculating intracellular fluxes? A: The key assumption is that all fluxes into a given intracellular metabolite pool balance all fluxes out of the pool [3]. This implies that intracellular metabolite concentrations remain constant over time (metabolic steady state). Although this is not strictly true in an absolute sense, cells rapidly adjust metabolite levels, typically reaching new constant concentrations within 1-2 minutes after environmental changes [3].

Q3: My flux resolution in peripheral pathways is poor. How can I improve it? A: This is a common challenge. Consider these approaches:

- Use multiple labeling substrates (COMPLETE-MFA) to provide more isotopomer constraints [4] [6]

- Implement INST-MFA to capture transient labeling patterns before isotopic steady state is reached [7] [4]

- Integrate additional measurements such as extracellular uptake/secretion rates, enzyme activity assays, or thermodynamic constraints [7]

- Ensure your metabolic network model accurately represents all relevant reactions and compartments

Q4: How do I choose between FBA, 13C-MFA, and INST-MFA for my study? A: The choice depends on your research question and system:

| Method | Best For | Key Requirements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Genome-scale predictions; Systems-level modeling | Metabolic network model; Objective function (e.g., growth) | Predictive only; Doesn't use experimental flux measurements [4] |

| 13C-MFA | Accurate quantification of central carbon metabolism | Metabolic & isotopic steady state; 13C-labeled substrate | Slow isotopic steady state in mammalian cells [4] [6] |

| INST-MFA | Systems where isotopic steady state is slow or not achievable | Metabolic steady state; Time-course labeling data | Computationally intensive; Complex data analysis [7] [4] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Labeling Patterns Between Biological Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient Metabolic Steady State: Ensure cells are maintained in a constant environment long enough to reach a true metabolic steady state before introducing the labeled tracer. Chemostat cultivations are ideal for this purpose [5].

- Variability in Extraction Efficiency: Standardize metabolite quenching and extraction protocols. Use internal standards where possible.

- Incomplete Isotopic Steady State: For 13C-MFA, verify that isotopic steady state has been reached by measuring labeling patterns at multiple time points [4] [6]. For mammalian cells, this may require several hours or even a day [4].

Problem: Poor Fit Between Experimental Data and Computational Model

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Network Completeness: Ensure your metabolic network model includes all relevant reactions, particularly around problematic metabolites.

- Verify Carbon Transitions: Review the carbon atom mapping for each reaction - incorrect mappings will produce systematic errors.

- Examine Residuals: Identify which specific measurements show the largest discrepancies - this often points to missing pathways or regulatory mechanisms.

Problem: Low Signal-to-Noise in Isotope Labeling Measurements

Optimization Strategies:

Analytical Platform Selection:

Tracer Selection: Use tracers that maximize information content for your pathways of interest. Uniformly labeled [U-13C] glucose is a good starting point for central carbon metabolism [4] [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are essential for successful metabolic flux analysis:

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | Tracing glycolytic and PPP fluxes | Specific labeling positions provide different information [4] |

| [U-13C] Glucose | Uniform labeling of central carbon metabolites | Most common tracer for initial studies [4] [6] |

| 13C-Glutamine | Tracing TCA cycle and anaplerotic fluxes | Essential for cancer cell metabolism studies |

| Quenching Solution | Rapid inactivation of metabolism | Typically cold methanol-based, composition affects metabolite recovery |

| Internal Standards | Quantification normalization | Use 13C-labeled or otherwise distinguishable analogs |

| METRAN, INCA, or OpenFLUX Software | Computational flux analysis | INCA is widely used for 13C-MFA with user-friendly interface [4] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard 13C-MFA Workflow for Microbial Systems

Principle: Cells are cultivated at metabolic steady state with 13C-labeled substrate until isotopic steady state is reached. Labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are then used to calculate fluxes [4] [6].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Grow cells in unlabeled medium to desired metabolic steady state (e.g., mid-exponential phase in batch culture or steady state in chemostat).

- Labeling Experiment: Rapidly transfer cells to identical medium containing 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-13C] glucose).

- Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points after isotopic steady state is reached (typically 2-3 generation times for microbes).

- Quenching: Rapidly cool cells in cold methanol (-40°C) to stop all metabolic activity.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use appropriate extraction solvent (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform) to recover intracellular metabolites.

- Analysis: Derivatize metabolites (for GC-MS) or directly analyze (for LC-MS) to determine mass isotopomer distributions.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational software (e.g., INCA) to find the set of fluxes that best fit the measured labeling patterns and external flux data.

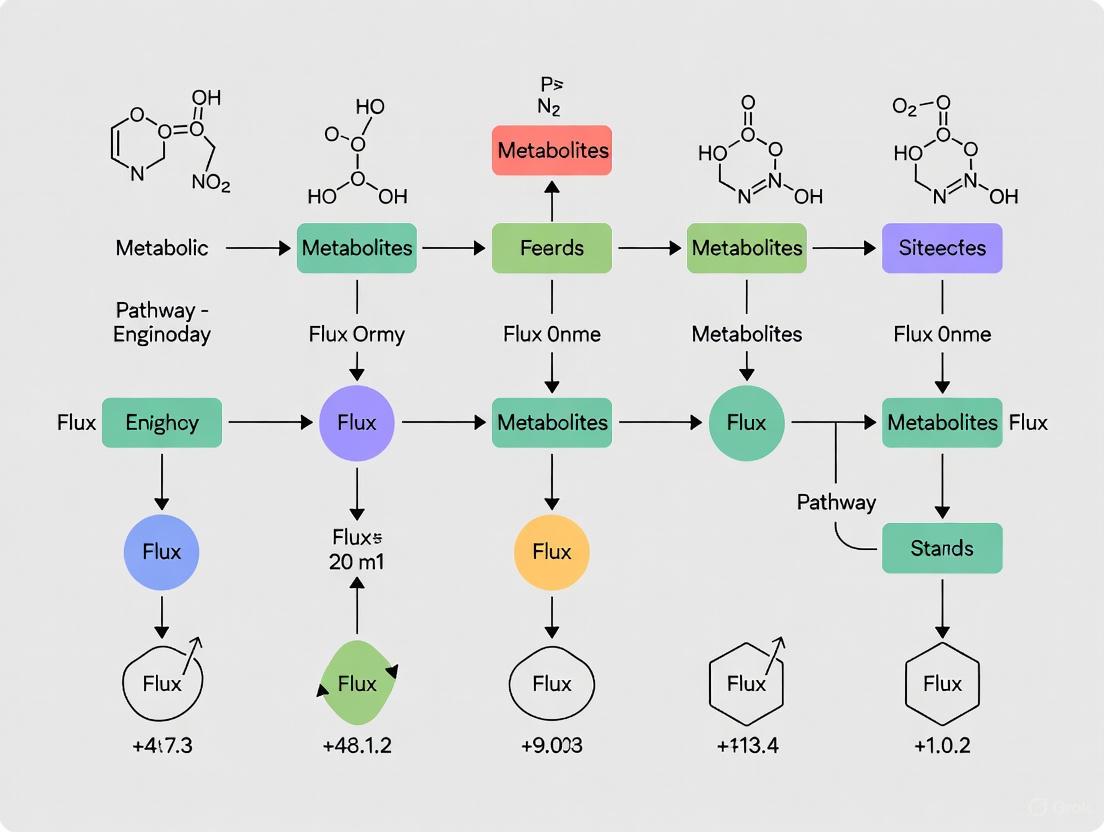

Figure 1: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow

Protocol 2: INST-MFA for Mammalian Cells

When to Use: When isotopic steady state takes too long to reach (e.g., in mammalian cells) or when studying transient metabolic states [7] [4].

Key Modifications from Standard 13C-MFA:

- Time Course Sampling: Collect samples at multiple early time points (seconds to minutes) after introducing the labeled tracer.

- Rapid Sampling Techniques: Use automated systems or rapid filtration for precise timing.

- Dynamic Modeling: Use computational approaches that solve differential equations for isotopomer dynamics rather than algebraic balance equations.

Metabolic Network Visualization and Flux Relationships

Understanding how fluxes are interconnected through metabolic networks is crucial for interpreting flux data and designing engineering strategies.

Figure 2: Central Carbon Metabolic Network

Key Regulatory Nodes in the Network:

- G6P Branch Point: Distribution between glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway is tightly regulated by NADPH demand and metabolic state [1]

- Pyruvate Node: Critical branch point between mitochondrial oxidation (via PDH), anaplerosis (via PC), and lactate production

- Acetyl-CoA: Central metabolite linking carbohydrate, lipid, and energy metabolism

Advanced Applications in Pathway Engineering

Case Study: Engineering E. coli for Acetol Production

A recent study used 13C-MFA to identify that acetol production in E. coli was limited by NADPH supply. By quantifying fluxes, researchers could strategically engineer the strain to enhance NADPH regeneration, thereby increasing product yield [7].

Case Study: Cyanobacterial Aldehyde Production

In S. elongatus, INST-MFA analysis revealed negative correlations between pyruvate metabolism routes and aldehyde production. Knocking down competing pathways identified through flux analysis resulted in a 50% increase in productivity [7].

Integrative Analysis Approach: Successful pathway engineering requires combining flux analysis with other data types:

- Transcriptomics: Identifies regulatory bottlenecks

- Proteomics: Reveals enzyme abundance limitations

- Metabolomics: Detects potential inhibitory metabolite accumulation

- Thermodynamics: Identifies potentially irreversible reactions

This multi-omics integration provides a systems-level understanding for rational design of engineered strains with optimized metabolic fluxes for desired outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a metabolic network model and what is its primary purpose? A metabolic network model is a computational representation of the complete set of metabolic reactions within an organism, correlating its genome with molecular physiology. Its primary purpose is to provide a structured, mathematical platform to understand systems biology of metabolic pathways, allowing researchers to predict an organism's metabolic capabilities, identify essential genes, and analyze network robustness. These models are fundamental for predicting how manipulations to the network, such as gene knockouts, will affect the production of biomass or target metabolites [8] [9].

2. What is the Stoichiometric Matrix (S)?

The stoichiometric matrix (S) is the core mathematical component of a constraint-based metabolic model. It is a matrix of size m x n, where m is the number of metabolites and n is the number of reactions in the network. Each entry in the matrix, S(i,j), is the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j. A negative coefficient indicates the metabolite is a substrate (consumed), while a positive coefficient indicates it is a product (formed). A coefficient of zero means the metabolite does not participate in the reaction [10] [11] [12].

3. What does the "steady-state assumption" mean?

The steady-state assumption is a fundamental constraint in models like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). It states that the concentration of internal metabolites does not change over time. Mathematically, this is represented by the equation S ⋅ v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the vector of reaction fluxes. This means that for every internal metabolite, the total rate of production is equal to the total rate of consumption [11] [13] [9].

4. What is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and how does it use the stoichiometric matrix?

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a widely used constraint-based method for simulating metabolism in genome-scale models. It uses the stoichiometric matrix S to define the system of linear equations S ⋅ v = 0 under the steady-state assumption. Because this system is typically underdetermined (more reactions than metabolites), FBA finds a single, optimal solution by postulating that the cell has evolved to optimize a biological objective (e.g., maximization of growth). This is solved using linear programming to find a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes a defined objective function [11] [13].

5. My model fails to produce biomass in simulations. What could be wrong? A common reason for this is "gaps" in the draft metabolic network, often due to missing reactions from incomplete annotations. This is frequently addressed through a process called gapfilling. Gapfilling algorithms compare your model to a database of known reactions and find a minimal set of reactions that, when added to your model, will allow it to produce biomass on a specified growth medium. It is often advisable to perform initial gapfilling on a minimal media to ensure the algorithm adds the necessary biosynthetic pathways [14].

6. How do I choose an appropriate objective function for FBA? The choice of objective function is context-dependent. For simulating microbial growth, a common objective is to maximize the flux through a biomass reaction, which drains various biomass precursor metabolites (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides) in their required proportions. Other objective functions can be used, such as maximizing ATP production or the synthesis rate of a particular metabolite of biotechnological interest [11] [13].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model cannot produce biomass | Missing essential metabolic reactions (gaps) in the network. | Use a gapfilling algorithm to identify and add missing reactions [14]. |

| Unrealistic flux predictions | Incorrect constraints on exchange reactions (e.g., unlimited oxygen or nutrient uptake). | Apply physiologically realistic lower and upper bounds (lb, ub) on nutrient uptake and other exchange fluxes [11] [13]. |

| Infeasible FBA solution | The constraints are too restrictive and no solution satisfies S ⋅ v = 0. |

Check reaction directionality (irreversible reactions set with lb=0). Review and relax nutrient uptake constraints if necessary. |

| Gene deletion does not affect growth in silico | Presence of redundant, alternative pathways in the network. | Perform double gene deletion analysis to identify synthetic lethal pairs [13]. |

Key Quantitative Data from Established Metabolic Models

The following table summarizes the scale of several manually curated, genome-scale metabolic models, highlighting the relationship between genome size and model complexity [8].

| Organism | Genes in Genome | Genes in Model | Reactions | Metabolites | Date of Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1,775 | 296 | 488 | 343 | June 1999 |

| Escherichia coli | 4,405 | 660 | 627 | 438 | May 2000 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 6,183 | 708 | 1,175 | 584 | February 2003 |

| Homo sapiens | 21,090 | 3,623 | 3,673 | -- | January 2007 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Databases and Software

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG | Database | A bioinformatics resource containing information on genes, proteins, reactions, and pathways [8]. |

| BioCyc/MetaCyc | Database | A collection of pathway/genome databases and an encyclopedia of experimentally defined metabolic pathways and enzymes [8]. |

| BRENDA | Database | A comprehensive enzyme database providing functional data [8]. |

| BiGG Models | Database | A knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions [8]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Toolbox | A MATLAB toolbox for performing constraint-based reconstruction and analysis, including FBA [11]. |

| Pathway Tools | Software | Assists in constructing pathway/genome databases and can generate metabolic models from annotated genomes [8]. |

| ModelSEED | Web Resource | An online resource for the automated reconstruction, analysis, and curation of genome-scale metabolic models [8] [14]. |

Workflow Diagram: From Genome to Metabolic Model

The diagram below illustrates the general workflow for reconstructing and analyzing a genome-scale metabolic model.

Mathematical Foundation of the Stoichiometric Matrix

The stoichiometric matrix S is the foundation for constraint-based modeling. The dynamics of the metabolic network are described by:

dC/dt = S · v [10] [9]

Where:

- C is the vector of metabolite concentrations.

- t is time.

- v is the vector of reaction rates (fluxes).

Applying the steady-state assumption simplifies this to a system of linear equations: S · v = 0 [11] [13] [9]

This equation, along with constraints on reaction fluxes (lb ≤ v ≤ ub), defines the solution space of all possible metabolic flux distributions. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) finds an optimal flux vector within this space by solving the linear programming problem:

Maximize cᵀv

Subject to: S · v = 0 and lb ≤ v ≤ ub [13]

where c is a vector of weights defining the objective function, such as biomass production.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean if my FBA problem is infeasible? An infeasible FBA problem means that no flux distribution satisfies all your constraints simultaneously. This often occurs when integrating measured flux values that violate the steady-state condition or other physicochemical constraints [15]. The mathematical problem becomes unsolvable until these inconsistencies are corrected.

2. What are the most common causes of infeasibility in FBA? The primary causes include:

- Inconsistent measured fluxes: Experimentally determined reaction rates that conflict with mass balance or other constraints [15]

- Violated reversibility constraints: Flux bounds that force irreversible reactions to operate in the thermodynamically infeasible direction

- Conflicting inequality constraints: Limitations such as enzyme capacity constraints that cannot all be satisfied simultaneously [15]

3. What methods can resolve infeasible FBA problems? Two main computational approaches can identify minimal corrections to restore feasibility:

- Linear Programming (LP): Finds the minimal number of flux constraints that need adjustment [15]

- Quadratic Programming (QP): Identifies the minimal squared deviation from measured fluxes required to achieve feasibility [15]

4. How does classical Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) differ from FBA in handling inconsistencies? Classical MFA uses algebraic methods and least-squares approaches to resolve inconsistencies in flux scenarios but cannot handle inequality constraints like reaction reversibilities or enzyme capacity limits that FBA can accommodate [15].

5. What are the key limitations of standard FBA? Major limitations include the steady-state assumption that may not reflect dynamic processes, lack of kinetic information and regulatory mechanisms, and dependence on accurate network reconstruction and appropriate objective function selection [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Diagnosing Infeasible FBA Scenarios

Problem: Your FBA problem returns as infeasible after integrating measured flux values.

Diagnosis Protocol:

Check constraint consistency [15]:

- Verify that all fixed flux values (

ri = fi) comply with reaction directionality constraints - Ensure measured exchange fluxes align with known substrate uptake capabilities

- Confirm steady-state mass balance is not violated by the combined flux constraints

- Verify that all fixed flux values (

Analyze system redundancy [15]:

- Calculate the degrees of redundancy:

degR = m - rank(NU) - Identify metabolites with conflicting mass balance requirements

- Determine if the system is over-constrained due to too many fixed fluxes

- Calculate the degrees of redundancy:

Systematically relax constraints [15]:

- Temporarily remove recently added flux constraints one by one

- Test if the problem becomes feasible with fewer fixed fluxes

- Identify the specific constraint(s) causing the conflict

Table: Quantitative Standards for Flux Scenario Analysis [15]

| System Property | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Determinacy | rank(NU) = x |

All fluxes uniquely determined |

| Underdetermined | rank(NU) < x |

Some fluxes not uniquely calculable |

| Degrees of Freedom | x - rank(NU) |

Dimension of nullspace of NU |

| Redundancy | m - rank(NU) |

Number of linearly dependent metabolite rows |

Issue 2: Resolving Infeasibility with Minimal Corrections

Solution Approaches:

Method 1: Linear Programming Approach [15]

This LP finds the minimal number of flux corrections (δ_i) to restore feasibility.

Method 2: Quadratic Programming Approach [15]

This QP finds minimal squared deviations from measured fluxes.

Implementation Workflow:

Issue 3: Addressing Limitations in FBA Predictions

Problem: FBA predictions diverge from experimental observations despite feasible solutions.

Troubleshooting Strategy:

Validate network reconstruction completeness [16]:

- Audit gap-filled reactions for thermodynamic plausibility

- Verify all essential metabolic functions are present

- Check for missing cofactor balances or energy requirements

Assess objective function appropriateness [16]:

- Test alternative biological objectives (ATP production, substrate uptake)

- Implement multi-objective optimization approaches

- Validate that chosen objective aligns with experimental conditions

Incorporate additional constraints [17]:

- Add thermodynamic constraints using Gibbs free energy values

- Implement enzyme capacity constraints based on proteomic data

- Include transcriptional regulatory constraints when available

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Flux Balance Analysis

Purpose: Predict optimal metabolic flux distributions maximizing biomass production [16].

Materials:

- Stoichiometric matrix (S): Mathematical representation of metabolic network

- Flux bounds (lb, ub): Thermodynamic and capacity constraints

- Objective vector (c): Biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization)

- Linear programming solver: Computational tool for optimization

Procedure:

- Formulate the optimization problem:

Implement in COBRApy or similar framework [17]:

Validate solution feasibility and biological plausibility

Perform sensitivity analysis on key flux bounds

Expected Output: Optimal flux distribution satisfying all constraints while maximizing objective function.

Protocol 2: FBA with Integrated Experimental Flux Measurements

Purpose: Incorporate known flux measurements while predicting remaining fluxes [15].

Materials:

- Measured flux values (f_i): Experimentally determined reaction rates

- Measurement confidence weights (w_i): Reliability estimates for measurements

- Extended constraint set: Base constraints plus flux equality constraints

Procedure:

- Identify reactions with measured fluxes (set F)

- Add equality constraints:

v_i = f_ifor all i ∈ F - If system becomes infeasible, apply correction methods:

- Implement LP or QP approaches to find minimal corrections δ_i

- Solve for

v_i = f_i + δ_iinstead of strict equalities

- Validate that corrected fluxes remain biologically plausible

- Compare predictions with and without flux measurements

Expected Output: Flux distribution consistent with both measurements and network constraints.

Protocol 3: Pathway Ranking Using Multi-Metric FBA

Purpose: Evaluate and rank heterologous pathways using multiple performance metrics [17].

Materials:

- Heterologous pathways (SBML format): Pathways to evaluate

- Host metabolic model (SBML): Chassis organism model (e.g., E. coli iML1515)

- Target molecule: Compound of interest (e.g., lycopene)

- Thermodynamic calculator: Tool for Gibbs free energy estimation

Procedure:

- Flux Analysis:

- Merge heterologous pathways with host model

- Perform FBA enforcing biomass flux at 75% of maximum

- Optimize for target production flux

- Record production flux values [17]

Thermodynamic Analysis:

- Calculate Gibbs free energy for each reaction using component contribution method

- Combine reaction energies to estimate pathway thermodynamics

- Identify thermodynamically favorable pathways (ΔG < 0) [17]

Multi-criteria Scoring:

- Calculate global score combining target flux, thermodynamics, pathway length, and enzyme availability

- Rank pathways based on composite score [17]

Expected Output: Ranked list of pathways with quantitative performance metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for FBA [15] [16] [17]

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis | Python package for FBA implementation and simulation [17] |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | Network structure representation | Mathematical foundation for mass balance constraints [16] |

| Linear Programming Solver | Optimization algorithm | Finding optimal flux distributions [15] |

| SBML Models | Standardized model format | Sharing and comparing metabolic models [17] |

| Thermodynamic Calculator | Gibbs free energy estimation | Assessing pathway feasibility [17] |

| Flux Variability Analysis | Solution space characterization | Identifying alternative optimal solutions [15] |

| Model SEED | Genome-scale reconstruction | Draft model generation from genomic data [16] |

| BiGG Database | Curated metabolic models | Access to validated genome-scale models [17] |

| eQuilibrator | Thermodynamic calculations | Estimating reaction Gibbs energies [17] |

In the field of metabolic engineering, the directed improvement of cellular properties requires a deep understanding of intracellular reaction rates, or metabolic fluxes [18]. 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold standard technique for quantifying these in vivo fluxes in living cells [19] [20]. This powerful methodology integrates stable isotope tracing, analytical measurements, and mathematical modeling to generate quantitative maps of metabolic pathway activities [21] [22]. For researchers engineering organisms to produce valuable biochemicals, fuels, or pharmaceuticals, 13C-MFA provides indispensable insights into metabolic network functionality, enabling the identification of flux bottlenecks, verification of pathway engineering outcomes, and discovery of unforeseen metabolic rearrangements [22] [23]. Unlike indirect measurements of metabolism, 13C-MFA directly quantifies reaction rates, offering a systems-level perspective that is crucial for balancing metabolic flux in engineered pathways [18] [24].

Core Methodology and Experimental Workflow

The foundation of 13C-MFA lies in tracking stable carbon isotopes (13C) as they distribute through metabolic networks, with the resulting labeling patterns serving as constraints for computational flux calculation [19] [20]. The complete workflow encompasses several standardized phases, as visualized below.

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

The initial phase involves strategic selection of 13C-labeled substrates (tracers), which critically impacts the resolution of estimated fluxes [25]. For example, while single-labeled [1-13C]glucose costs approximately $100/g, the more informative double-labeled [1,2-13C]glucose (∼$600/g) significantly enhances flux estimation accuracy in central carbon metabolism [20] [25]. The optimal tracer depends on the specific metabolic pathways under investigation and the biological system, with common choices including [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, and various labeled glutamine tracers [21] [25].

Cell Culture and Steady-State Achievement

Cells are cultured in controlled bioreactors containing the selected 13C-tracer as the carbon source [24]. For stationary state 13C-MFA (SS-MFA), the system must reach both metabolic steady-state (constant metabolite concentrations and fluxes) and isotopic steady-state (constant isotopologue distributions) [21] [24]. This typically requires culturing for at least five residence times to ensure complete isotope equilibration [20]. During culture, precise measurements of growth rates and extracellular fluxes (nutrient uptake and product secretion rates) are essential for constraining the metabolic model [19].

Sample Processing and Analytical Measurement

Upon reaching isotopic steady-state, cells are rapidly quenched (e.g., using cold methanol) to halt metabolic activity, followed by metabolite extraction [24]. Intracellular metabolites are then analyzed using techniques including GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, or NMR to determine mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) [19] [20]. These MIDs represent the fractional abundances of different isotopic variants of each metabolite, encoding information about the metabolic fluxes that produced them [26].

Computational Flux Estimation

The core of 13C-MFA involves solving an inverse problem where fluxes are estimated by minimizing the difference between measured MIDs and those simulated by a metabolic network model [21] [19]. This is formalized as a least-squares optimization problem:

Where x represents simulated labeling patterns, xM represents measured labeling patterns, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and v is the flux vector [21]. This computation leverages frameworks such as the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework to efficiently simulate isotopic labeling, implemented in software platforms like INCA, Metran, and 13CFLUX2 [19] [20] [24].

Statistical Validation and Interpretation

The final flux solution undergoes rigorous statistical validation to evaluate its reliability and precision [20] [26]. This includes calculating confidence intervals for estimated fluxes using methods like sensitivity analysis or Monte Carlo simulation, and assessing the model fit through statistical tests such as the χ²-test or residual sum of squares (SSR) evaluation [20] [26]. The outcome is a quantitative flux map with assigned confidence intervals, enabling biological interpretation of pathway activities [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key reagents and computational tools for 13C-MFA experiments

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine | Carbon tracers that generate distinct labeling patterns dependent on pathway fluxes [20] [25]. |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, NMR | Quantification of mass isotopomer distributions in metabolic intermediates [19] [20]. |

| Cell Culture Materials | Bioreactors, Defined Media Components | Maintain controlled growth conditions and precise delivery of labeled substrates [24]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Kits | Methanol/Water-based Kits | Rapid quenching of metabolism and efficient metabolite extraction [24]. |

| Computational Software | INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX | Perform flux estimation using EMU framework and statistical validation [19] [20] [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Q: How do I select the optimal 13C-tracer for my specific research question? A: Tracer selection depends on the pathways of interest. For central carbon metabolism focusing on pentose phosphate pathway vs. glycolysis splits, [1,2-13C]glucose is often superior to [1-13C]glucose [25]. Use multi-objective optimal experimental design (OED) principles to balance information content with tracer costs [25]. For complex systems, consider parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers to significantly improve flux resolution [20].

Q: My experimental costs for labeled substrates are prohibitively high. What alternatives exist? A: Consider these cost-saving strategies: (1) Use tracer mixtures (e.g., mixing 20% [1,2-13C]glucose with 80% unlabeled glucose) rather than pure tracers [25]; (2) Employ multi-objective experimental design to identify cost-effective mixtures that maintain high information content [25]; (3) Scale down culture volumes while maintaining sufficient cell mass for analysis.

Cell Culture and Sampling

Q: How can I verify that my culture has reached isotopic steady-state before sampling? A: For microbial systems, ensure cultivation lasts at least five residence times [20]. Monitor labeling patterns in key metabolites (e.g., alanine, lactate) at multiple time points; when these patterns stabilize, isotopic steady-state has been achieved [24]. For mammalian cells with slower turnover, longer cultivation times (24-72 hours) may be necessary [19].

Q: I observe inconsistent extracellular flux measurements between biological replicates. How should I address this? A: Calculate extracellular fluxes during exponential growth phase using established formulas [19]:

- For proliferating cells:

r_i = 1000 · μ · V · ΔC_i / ΔN_x - For non-proliferating cells:

r_i = 1000 · V · ΔC_i / (Δt · N_x)Ensure accurate cell counting and metabolite concentration measurements. For unstable metabolites like glutamine, correct for chemical degradation using control experiments without cells [19].

Analytical Measurement Issues

Q: My mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) show high measurement noise. How can I improve data quality? A: Implement these best practices: (1) Increase biological replicates (n≥5 recommended for robust statistics) [26]; (2) Use appropriate internal standards for instrument calibration; (3) Verify that your extraction protocol efficiently quenches metabolism; (4) For GC-MS, derivative samples properly to ensure consistent fragmentation patterns [20].

Q: How should I handle apparently biased MID measurements where minor isotopomers are consistently underestimated? A: This common issue with orbitrap instruments requires specific correction approaches [26]: (1) Apply instrument-specific correction factors determined from standard measurements; (2) Consider using alternative analytical platforms (e.g., GC-MS) for validation; (3) Adjust your error model to account for these systematic biases during computational flux estimation [26].

Computational Flux Analysis and Model Selection

Q: My model consistently fails the χ² goodness-of-fit test. What are the potential causes and solutions? A: Poor model fit can stem from multiple sources [26]:

- Incomplete metabolic network: Add missing reactions or pathways based on genomic evidence

- Incorrect measurement error estimates: Re-evaluate your error model using biological replicates

- Metabolic non-steady-state: Verify culture conditions and sampling timing Systematically address these possibilities rather than arbitrarily increasing measurement error estimates [26].

Q: How do I select the most appropriate metabolic network model among multiple candidates? A: Move beyond traditional χ²-testing and implement validation-based model selection [26]: (1) Split your data into estimation and validation sets; (2) Fit each candidate model to the estimation data; (3) Select the model that best predicts the independent validation data. This approach is more robust to uncertainties in measurement errors and prevents overfitting [26].

Q: What do I do if my flux estimation results have unacceptably wide confidence intervals? A: Wide confidence intervals indicate poor flux identifiability. Consider these approaches: (1) Switch to more informative tracers (e.g., from [1-13C] to [1,2-13C]glucose) [25]; (2) Design parallel labeling experiments with complementary tracers [20]; (3) Incorporate additional physiological measurements (e.g., ATP demands, growth rates) as model constraints [19].

Interpretation and Application

Q: How can I distinguish between actual flux changes and artifacts of model misspecification? A: Apply rigorous statistical validation: (1) Use chi-square tests to evaluate model fit [20]; (2) Perform statistical tests for flux differences (e.g., using confidence intervals from Monte Carlo simulations) [20]; (3) Validate key findings with orthogonal approaches (e.g., enzyme assays, genetic manipulations) [23].

Q: What are the limitations of 13C-MFA that I should acknowledge in my research? A: Key limitations include: (1) Primarily applicable to central carbon metabolism due to computational constraints; (2) Requires metabolic and isotopic steady-state for standard implementations [21]; (3) Limited temporal resolution for dynamic processes; (4) Relatively high costs for labeled substrates [25]. Consider alternative methods like INST-MFA for non-steady-state systems or flux balance analysis for genome-scale predictions [21] [24].

Advanced Methodological Variations

Table 2: Comparison of 13C-MFA methodologies

| Method Type | Applicable System | Computational Complexity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary State MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems where fluxes and labeling are constant [21] | Medium | Not applicable to dynamic systems [21] |

| Isotopically Instationary MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems where labeling is dynamic but fluxes are constant [21] | High | Requires precise pool size measurements and multiple timepoints [27] [24] |

| Metabolically Instationary MFA | Systems where fluxes and labeling are variable [21] | Very High | Extremely challenging to perform and validate [21] |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | Systems with sequential linear reactions [21] | Medium | Limited to local subnetworks [21] |

| Flux Ratio Analysis | Systems where overall topology is unclear [21] | Medium | Provides relative, not absolute flux values [21] |

13C-MFA represents an indispensable methodology in the metabolic engineer's toolkit, providing unprecedented capability to quantify in vivo metabolic fluxes [22] [19]. As the field advances, several emerging trends are broadening its applications: the development of more user-friendly computational tools that make 13C-MFA accessible to non-experts [19]; the integration of multi-omics data constraints to create more comprehensive metabolic models [23]; and the advancement of instationary approaches that enable flux quantification in dynamic systems [27] [24]. For researchers engineering metabolic pathways, mastery of 13C-MFA principles and troubleshooting approaches is crucial for generating reliable, quantitative insights into cellular metabolism and guiding effective engineering strategies. By implementing the best practices and solutions outlined in this technical guide, scientists can overcome common experimental challenges and robustly apply 13C-MFA to advance their pathway engineering objectives.

Metabolic Steady-State vs. Isotopic Non-Stationarity

Core Concept Definitions

What are the fundamental definitions of Metabolic Steady-State and Isotopic Non-Stationarity?

- Metabolic Steady-State: A condition where intracellular metabolite concentrations and metabolic flux values remain constant over time. This state is characterized by balanced rates of metabolite production and consumption.

- Isotopic Non-Stationarity: A transient labeling period during which the incorporation of an isotopic tracer (e.g., 13C) into metabolic intermediates is still changing and has not reached equilibrium. This is also referred to as an isotopically non-stationary state.

How do these states relate to each other in experimental design? It is possible, and often desirable, to have a system that is in a metabolic steady-state but an isotopic non-stationary state. This means the underlying biochemistry and flux network is stable, while the label from a newly introduced tracer is still propagating through the system. This combination is the foundational principle for Isotopically Nonstationary Metabolic Flux Analysis (INST-MFA) [28] [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

FAQ: When should I choose INST-MFA over traditional steady-state 13C-MFA?

INST-MFA is the preferred method when your experimental system or question makes achieving isotopic steady state impractical or uninformative. The following table summarizes key scenarios.

| Scenario | Reason for Choosing INST-MFA | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Autotrophic Systems | Organisms using CO₂ as a carbon source reach a uniform, uninformative labeling pattern at isotopic steady state [31]. | Quantifying fluxes in cyanobacteria or plant leaves [28] [31]. |

| Short-Lived Metabolic States | The metabolic state changes faster than the time required to reach isotopic steady state [31]. | Measuring fluxes during transient oxidative stress or other rapid perturbations [31]. |

| Large Metabolite Pools or Bottlenecks | Systems with slow isotope labeling due to large intermediate pools [29]. | Studying metabolism in plant storage organs or heterotrophic tissues [31]. |

| Anuclear or Non-Replicating Cells | Cells with limited lifespan cannot be labeled for the extended periods needed for isotopic steady state [32]. | Flux analysis in human blood platelets [32]. |

| Enhanced Flux Resolution | INST-MFA provides increased sensitivity for estimating reversible exchange fluxes and metabolite pool sizes [29]. | Precisely quantifying substrate cycling and futile cycles [28]. |

FAQ: My isotopic labeling data is noisy or does not fit the model well. What could be wrong?

- Problem: Breach of Metabolic Steady-State Assumption. The underlying metabolism was not stable during the labeling experiment.

- Solution: Ensure rigorous environmental control (constant nutrient levels, pH, temperature) throughout the labeling time-course. For cell cultures, maintain cells in a chemostat or in well-controlled batch conditions during the exponential growth phase [32].

- Problem: Inadequate Sampling Frequency.

- Problem: Incorrect Metabolite Pool Size Estimation.

- Solution: INST-MFA simultaneously estimates fluxes and metabolite pool sizes. Poor fits can arise if the initial pool size estimates provided to the model are highly inaccurate. Use quantitative metabolomics to measure pool sizes for key intermediates to provide better initial constraints [29].

FAQ: How do I design an effective tracer experiment for INST-MFA?

- Tracer Selection: Use parallel labeling experiments with complementary tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C₂]glucose and [U-13C₆]glucose) to improve flux resolution [32]. Computational simulation of tracers in software like INCA can help identify optimal tracer mixtures before the wet-lab experiment [32].

- Experimental Workflow: A robust INST-MFA experiment follows a defined sequence, from model design to statistical validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: INST-MFA in Heterotrophic Plant Cells

This protocol, adapted from Frontiers in Plant Science, outlines the key steps for applying INST-MFA to heterotrophic Arabidopsis thaliana cell cultures, a system relevant to pathway engineering [31].

1. Cell Culture and Perturbation:

- Grow heterotrophic Arabidopsis cell cultures in the dark at 22°C in MS medium with 30 g/L glucose.

- To study a transient metabolic state, apply a perturbation such as 60 µM menadione to induce mild oxidative stress. Incubate for 6 hours before labeling.

2. Pulse Labeling and Rapid Sampling:

- Introduce a pulse of [13C₆]glucose to the culture. The final fractional enrichment should be high (e.g., ~60%).

- Begin immediate, rapid time-course sampling. Critical early time points include 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 10, 15, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 270 minutes after tracer addition.

- At each time point, rapidly separate cells from medium (e.g., vacuum filtration in <10 seconds) and quench metabolism immediately using a cold mixture of dichloromethane:ethanol (2:1 v/v) on dry ice.

3. Metabolite Extraction and Analysis:

- Homogenize the quenched cells and perform a biphasic extraction.

- Collect the aqueous phase, acidify it, and filter it using a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) filter.

- Analyze the extracts using Ion Chromatography coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (IC-HRMS) in negative ion mode.

4. Data Processing and Flux Estimation:

- Process the raw LC-MS data with software like El-Maven to identify compounds and obtain Mass Isotopologue Distributions (MIDs).

- Correct the MIDs for natural abundance of heavy isotopes using a tool like AccuCor.

- Input the time-course MID data, extracellular flux data (e.g., substrate uptake rates), and metabolite pool sizes into specialized INST-MFA software such as INCA to compute the fluxes [28] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and computational tools for conducting INST-MFA studies.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| [1,2-13C₂]Glucose | Tracer to resolve parallel pathways and reversibility in central carbon metabolism (e.g., upper glycolysis) [32] [30]. |

| [U-13C₆]Glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer; provides high information content for comprehensive flux mapping [32]. |

| [1-13C]Acetate | Tracer to specifically probe TCA cycle activity and oxidative metabolism [32]. |

| INCA Software | A MATLAB-based software package for performing INST-MFA; automates network specification and model fitting [28] [32]. |

| OpenMebius | An open-source software alternative for INST-MFA calculations [28]. |

| IC-HRMS System | Analytical platform (e.g., Thermo Scientific ICS-5000+ coupled to Q-Exactive) for separating and measuring the isotopic labeling of a wide range of metabolic intermediates [31]. |

| El-Maven | Open-source software for automated processing of LC-MS data, including feature detection and MID extraction [31]. |

Advanced Tools for Flux Quantification and Strain Design

Experimental Design for 13C-Labeling and Tracer-Based Flux Analysis

Core Concepts of 13C-MFA

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful technique for quantifying intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) in living cells. By using 13C-labeled substrates and tracking their incorporation into metabolic products, researchers can determine the operational rates of metabolic pathways under specific physiological conditions [34]. This approach is particularly valuable for metabolic engineering, as it provides a quantitative map of cellular metabolism, revealing pathway bottlenecks, redundant routes, and energy efficiency that can be optimized for bioproduction [35] [36].

The technique relies on cultivating cells on a specifically chosen 13C-labeled tracer substrate (e.g., glucose or glutamine). As the cells metabolize the tracer, the 13C atoms are distributed through the metabolic network, creating unique labeling patterns in intracellular and extracellular metabolites. These patterns are measured using techniques like Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [34] [37]. The core of 13C-MFA is a computational process that estimates the intracellular fluxes by finding the best fit between the experimentally measured labeling data and the labeling patterns simulated by a stoichiometric metabolic network model [34] [36].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

Q: How do I select the best 13C-tracer for my specific metabolic question? A: Tracer selection is critical and should not be based on convention alone. The optimal tracer depends on which pathway fluxes you aim to observe [37] [38].

- Rational Design: Use the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) basis vector methodology. This framework helps identify tracers that maximize the number of independent observable labeling measurements, thereby improving the precision of flux estimation [37] [39].

- Avoid Trial-and-Error: Instead of testing a limited set of tracers, use rational design principles. For instance, to quantify the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (oxPPP) flux in mammalian cells, [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose has been identified as an optimal novel tracer, while [3,4-13C]glucose is optimal for elucidating pyruvate carboxylase (PC) flux [38].

- Parallel Labeling: Conducting parallel experiments with multiple different tracers can significantly enhance the information content for resolving complex metabolic networks, such as those in photomixotrophic cyanobacteria [40].

Q: What are common pitfalls in tracer experiment design, and how can I avoid them? A: A major pitfall is the failure to achieve a true isotopic steady state, leading to uninterpretable data [40].

- Protocol: For microbial systems, use a two-step labeling protocol. First, grow a pre-culture on the 13C tracer (e.g., from OD=0.1 to 1.5). Then, use this pre-culture to inoculate a main culture (again from OD=0.1 to 1.5). This ensures that the inoculum's unlabeled biomass is diluted to a negligible fraction (<0.5%), guaranteeing the culture is in both metabolic and isotopic steady state at the time of sampling [40].

- Evaporation and Degradation: For long-term experiments (>24 h), correct for medium evaporation and spontaneous degradation of unstable molecules like glutamine by running control experiments without cells [34].

Cell Cultivation and Data Acquisition

Q: How do I accurately measure the external nutrient consumption and by-product secretion rates needed for 13C-MFA? A: These external fluxes provide essential constraints for the model [34].

- For Exponentially Growing Cells: Measure the change in metabolite concentration (ΔCi in mmol/L) and cell number (ΔNx in millions of cells) between two time points during the labeling experiment. The external rate ri (nmol/10^6 cells/h) is calculated as: ri = 1000 · (μ · V · ΔCi) / ΔNx where μ is the specific growth rate (1/h) and V is the culture volume (mL). Uptake rates are negative, and secretion rates are positive [34].

- Growth Rate Calculation: The specific growth rate (μ) is determined from cell counts: μ = [ln(Nx,t2) - ln(Nx,t1)] / Δt. The doubling time is td = ln(2)/μ [34].

Q: My model fails to fit the measured labeling data. What could be wrong? A: This can stem from an incorrect or incomplete metabolic network model [36].

- Network Completeness: Ensure your model includes all relevant reactions for your organism and condition. In cyanobacteria, for example, this includes not just glycolysis and TCA cycle, but also the Entner-Doudoroff pathway, phosphoketolase pathway, and the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle [40].

- Model Exchange and Validation: Use standardized model description languages like FluxML to unambiguously define your network, including atom mappings and constraints. This improves reproducibility and allows other researchers to validate or build upon your work [36].

Computational Flux Analysis

Q: What software tools are available for 13C-MFA, and how do I choose? A: Several user-friendly software tools are available, built on efficient algorithms like the EMU framework [34].

- Popular Options: INCA (Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis) and Metran are dedicated software packages for 13C-MFA that simplify the flux estimation process [34].

- Standardized Formats: The FluxML language allows for the creation of model files that are independent of the software, enhancing reproducibility and model sharing [36].

Q: Why are the confidence intervals for my estimated fluxes unacceptably large? A: Large confidence intervals indicate low precision, often due to insufficient information in your data [37] [38].

- Improve Tracer Choice: Re-evaluate your tracer using the EMU basis vector method. A poor tracer choice can make certain fluxes fundamentally unobservable [37].

- Increase Measurement Redundancy: Measure labeling patterns in multiple metabolites (e.g., amino acids from protein hydrolysates, sugars from glycogen) and use multiple analytical techniques (e.g., combining GC-MS and NMR) [40].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rational Tracer Selection using EMU Framework

- Define Metabolic Network: Construct a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network, including atom transitions for each reaction [37] [39].

- Perform EMU Decomposition: Use software like Metran to decompose the network model into its constituent Elementary Metabolite Units. This identifies the minimal set of metabolite fragments needed to simulate the measured labeling patterns [37].

- Identify EMU Basis Vectors: The decomposition will reveal the EMU basis vectors. The number of independent basis vectors sets a hard limit on how many free fluxes can be determined [37] [38].

- Analyze Coefficient Sensitivities: Evaluate how sensitive the coefficients of the key EMU basis vectors are to changes in the free fluxes you wish to estimate. Tracers that lead to high sensitivity are preferable [38].

- Select Optimal Tracer: Choose the tracer substrate that maximizes both the number of independent EMU basis vectors and the sensitivities related to your target fluxes [37] [38].

Protocol 2: Steady-State 13C-Labeling Experiment for Microbes

- Pre-culture Preparation: Inoculate a pre-culture in minimal medium containing the chosen 13C-labeled tracer substrate. Grow the cells to mid-exponential phase (e.g., OD750 from 0.1 to 1.5) [40].

- Main Culture Inoculation: Use the pre-culture to inoculate the main experimental culture (again starting at OD750 ~0.1) with fresh medium containing the same 13C tracer. This two-step process ensures isotopic steady state [40].

- Monitoring and Sampling: Monitor cell growth (optical density) and metabolite concentrations over time.

- Analytical Measurements:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for 13C-MFA

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Substrates with specific 13C atomic positions to trace metabolic pathways. | [1,2-13C]glucose to trace glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway activity [34] [37]. |

| Metran / INCA Software | User-friendly software platforms for performing 13C-MFA calculations. | Quantifying intracellular fluxes from GC-MS measured MIDs using the EMU framework [34]. |

| FluxML Language | A universal, machine-readable modeling language for 13C-MFA models. | Unambiguously defining and sharing a complete metabolic network model, including atom mappings [36]. |

| GC-MS Instrument | Analytical instrument for measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of metabolites. | Determining the labeling patterns of proteinogenic amino acids to infer fluxes in central carbon metabolism [34] [40]. |

| Stoichiometric Model | A mathematical matrix (S) defining all metabolic reactions and their mass balances. | Formulating the core constraints (S·v = 0) for flux estimation [35] [16]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram Title: 13C-MFA Workflow

Diagram Title: EMU Basis Vector Concept

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using TIObjFind over traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)? Traditional FBA often uses a static objective function, like biomass maximization, which may not accurately capture cellular behavior under all conditions, leading to a mismatch with experimental data [41] [42]. TIObjFind addresses this by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific metabolic objectives from experimental data. It identifies Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) for reactions, providing a data-driven objective function that better aligns with observed fluxes and enhances the interpretability of metabolic networks [41] [42].

Q2: My FBA predictions do not match my experimental flux data. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge and often stems from an inappropriate objective function [41]. The TIObjFind framework was specifically designed to address this issue. Furthermore, FBA can perform poorly in predicting fluxes for engineered strains, and its intracellular flux predictions are not always consistent with fluxes measured by more advanced methods like 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [35]. You should ensure that your model constraints (e.g., nutrient uptake rates) are accurate and consider using TIObjFind to identify an objective function that aligns with your experimental conditions [41] [35].

Q3: How can computational frameworks help in selecting a Microbial Cell Factory (MCF) chassis? Genome-scale metabolic models, a core component of frameworks like FBA, are critical for host selection [43]. They can be used to assess metabolic capabilities, such as the availability of precursors and cofactors (ATP, NAD(P)H) required for your target pathway. Computational tools allow you to evaluate multiple potential hosts to see which best accommodates the biosynthetic pathway of interest, and to identify metabolic engineering strategies to optimize the chassis for production [43].

Q4: What are "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) in TIObjFind? Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) are quantitative measures assigned to each metabolic reaction within the TIObjFind framework [41] [42]. They quantify a reaction's contribution to a data-driven objective function. A higher CoI suggests that the reaction's flux is critical for aligning the model's predictions with the experimental data, thereby indicating its importance to the cellular objective under specific conditions [41] [42].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High Discrepancy Between Predicted and Experimental Flux Values

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Objective Function | Compare FBA predictions using biomass maximization vs. product synthesis against your data [41]. | Implement the TIObjFind framework to identify a weighted objective function with Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that minimizes the difference from experimental data [41] [42]. |

| Overly Restrictive Flux Bounds | Check if measured uptake/secretion rates are correctly set as model constraints [35]. | Recalibrate flux bounds using available experimental data, such as nutrient absorption and product secretion rates [35]. |

| Inadequate Model Coverage | Verify if all relevant pathways for your product are present in the network model. | Consult databases like KEGG and MetaNetX to incorporate missing heterologous or artificial biosynthetic pathways into your model [41] [43]. |

Problem: Model Fails to Predict Growth or Product Yield in Engineered Strain

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic Pathway Intermediates | Analyze growth inhibition post-pathway introduction; check for known toxic metabolites [43]. | Consider chassis engineering for tolerance or pathway modification to avoid toxic intermediates [43]. |

| Incorrect Maintenance Energy Assumption | Review the ATP maintenance flux (ATPM) value in the model. | Adjust the ATP maintenance reaction flux to a level appropriate for your chassis and condition [35]. |

| Gene Knockout Lethality | Perform single gene deletion analysis using the model. | Identify and implement alternative metabolic routes to bypass the lethal knockout using model-guided design [35]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Implementing the TIObjFind Framework

The TIObjFind framework identifies metabolic objective functions by integrating FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) [41] [42]. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

1. Prerequisite Data and Model Preparation

- Metabolic Network Model: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model in a stoichiometric matrix format (S) for your organism of interest.

- Experimental Flux Data ($v^{exp}$): Collect measured flux data for key reactions under the condition you are modeling. This can be derived from methods like 13C-MFA or from measured uptake and secretion rates [35].

2. Single-Stage Optimization for Candidate Objectives

- Reformulate the FBA problem to a single-stage optimization that minimizes the squared error between predicted fluxes ($v$) and experimental data ($v^{exp}$), while maximizing a hypothesized objective ($c^{obj} \cdot v$) [42].

- Mathematically, this is represented as finding the best-fit FBA solutions by evaluating different candidate objective vectors ($c$). The output is an optimal flux distribution ($v^*_j$) [42].

3. Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction and Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA)

- Graph Construction: Map the derived flux solution ($v^*_j$) onto a directed, weighted graph called a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), $G(V,E)$ [41] [42].

- Pathway Identification: Apply a path-finding algorithm (e.g., a minimum-cut algorithm like Boykov-Kolmogorov) to this graph. Define a start reaction (s), such as glucose uptake, and a target reaction (t), such as product secretion. The algorithm will identify critical pathways and bottlenecks between s and t [41] [42].

4. Calculation of Coefficients of Importance (CoIs)

- The results from the minimum-cut analysis are used to compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients quantify the contribution of each reaction to the objective function that best explains the experimental data [41] [42].

- The CoIs ($c_j$) are then used as weights in a new, data-informed objective function ($c^{obj} \cdot v$) for subsequent FBA simulations, ensuring predictions are aligned with experimental observations [41] [42].

TIObjFind Framework Workflow: This diagram outlines the step-by-step process for implementing the topology-informed objective function identification framework.

Protocol: Constraint-Based Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

1. Define the Stoichiometric Matrix and Constraints

- Compile the stoichiometric matrix (S) of the metabolic network, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions [35].

- Apply the steady-state assumption, mathematically represented as $S \times v = 0$, meaning the net production and consumption of each intracellular metabolite is balanced [35].

- Set lower and upper flux bounds ($LB \leq v \leq UB$) for each reaction based on thermodynamic constraints (irreversibility) and measured uptake/secretion rates [35].

2. Define and Solve the Linear Programming Problem

- Choose an objective function to be maximized (or minimized). A common objective is the biomass reaction ($v_{biomass}$) to simulate growth [35].

- The linear programming problem is formulated as:

- Maximize $v_{biomass}$ (or other objective $Z = c \cdot v$)

- Subject to:

- $S \times v = 0$

- $-v{glucose} = GUR{max}$ (and other nutrient constraints)

- $LB \leq v \leq UB$ [35]

- Solve using a linear programming solver (e.g., within the COBRA Toolbox) [35].

Data Presentation

Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Engineering

Table 1: Essential research reagents, tools, and their functions in metabolic flux analysis and engineering.

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Substrates | Experimental Reagent | Used in 13C-MFA tracer experiments to determine precise intracellular metabolic fluxes based on isotopic labeling patterns [35]. |

| Glucose Uptake Assay Kit | Experimental Reagent | Measures the rate of glucose consumption by cells, a critical parameter for constraining metabolic models [35]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Toolkit | A MATLAB-based suite that integrates various FBA algorithms and constraint-based modeling methods for metabolic engineering [35]. |

| Model SEED | Software Tool | An automated platform for building, comparing, and analyzing genome-scale metabolic models across thousands of potential microbial hosts [43]. |

| MetaNetX | Database/Software | A resource that allows for the direct incorporation of new de novo biosynthetic pathways into existing genome-scale models for analysis [43]. |

| MIDAS Platform | Research Platform | A technology platform to systematically identify interactions between metabolites and proteins, suggesting new ways to target pathways for drug development [44]. |

Quantitative Analysis of FBA and Enhancements

Table 2: Comparison of flux analysis methods and performance outcomes from case studies.

| Method / Framework | Key Inputs | Primary Output | Reported Outcome / Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FBA [35] | Stoichiometric Model (S), Objective Function, Flux Bounds | Predicted Flux Distribution | Predicts E. coli max growth ~1.0 h⁻¹; Can be inconsistent with 13C-MFA data [35]. |

| 13C-MFA [35] | Stoichiometric Model (S), 13C-labeling data, Extracellular Rates | Estimated Intracellular Fluxes | Provides high-precision flux measurements in complex biological systems [35]. |

| TIObjFind [41] [42] | Stoichiometric Model (S), Experimental Flux Data ($v^{exp}$) | Data-Driven Objective Function (CoIs), Aligned Fluxes | Case Study (C. acetobutylicum): Reduced prediction errors and improved alignment with experimental data [41]. |

| Deuterium Replacement [45] | Lead Compound with Metabolic Soft Spot | Metabolically Stabilized Analog | Strategy to lower intrinsic clearance and extend half-life by blocking susceptible sites [45]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

- 13C-labeled Substrates: These are crucial for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), the gold-standard method for experimentally measuring intracellular metabolic fluxes with high precision. The labeling patterns from these substrates provide data to estimate fluxes [35].

- Enzyme Activity Assay Kits (e.g., Hexokinase, PDH): These kits allow researchers to measure the in vitro activity of specific metabolic enzymes. This data can be used to set maximum enzyme flux capacity constraints ($v_{max}$) in genome-scale models, making FBA predictions more accurate [35].

- Metabolite Assay Kits (e.g., ATP, PEP, Glucose-6-Phosphate): Quantifying the concentration of key metabolites and cofactors (ATP, NADH) helps validate model predictions and provides insight into the energy and redox state of the cell, which governs metabolic flux [35].

- COBRA Toolbox: This is a fundamental software toolkit for performing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and related constraint-based modeling methods. It is widely used in metabolic engineering to predict growth rates, metabolic yields, and design engineering strategies [35].

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: These are computational representations of an organism's metabolism, structured as a stoichiometric matrix (S). They serve as the core platform for running FBA, TIObjFind, and other in silico simulations to predict cellular phenotype from genotype [35] [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle behind Comparative Flux Sampling Analysis (CFSA)? CFSA is a strain design method that identifies metabolic engineering targets by extensively comparing the complete spaces of feasible metabolic fluxes (the "solution space") under different physiological scenarios. Instead of predicting a single optimal flux state, it statistically analyzes the differences in flux distributions between growth-oriented, production-oriented, and slow-growth phenotypes to suggest interventions like gene knock-outs, down-regulations, and over-expressions that can lead to growth-uncoupled production [46].

2. How does flux sampling in CFSA differ from traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)? Unlike FBA, which computes a single, optimal flux distribution based on a defined cellular objective (e.g., maximizing growth), flux sampling explores the entire range of possible flux distributions that a metabolic network can achieve at steady-state, without the need for an objective function. This provides a probability distribution for each reaction's flux, capturing network robustness and eliminating observer bias introduced by assuming a cellular goal [47].

3. What are the main advantages of using CFSA for strain design? The primary advantages include:

- Growth-Uncoupled Production: It specifically identifies targets for two-stage fermentation processes, where growth and production phases are separated, helping to alleviate metabolic stress [46].

- Comprehensive Exploration: It considers all feasible flux solutions simultaneously, unlike FVA which analyzes reactions in isolation [46].

- No A Priori Data: The method does not require pre-existing experimental fluxomic data to predict engineering targets [46].

4. Which sampling algorithm should I use for my genome-scale model? The choice of algorithm can impact efficiency and convergence. Based on a rigorous comparison:

- OptGP is well-suited for larger models and supports parallel processing, which can significantly reduce computation time [48] [47].

- ACHR does not support parallel execution but has good convergence properties and is almost Markovian [48].

- CHRR has been shown to have the fastest run-time and convergence for some models, but may be implementation-dependent (e.g., available in MATLAB COBRA toolbox) [47]. We recommend benchmarking with your specific model.

5. I've generated flux samples. How do I know if they are valid and the sampling has converged?

- Validation: Use the

validatefunction available in sampler objects (e.g.,achr.validate(samples)). It quickly checks for feasibility violations, returning 'v' for valid points, and codes for violations like lower/upper bound ('l', 'u') or steady-state ('e') errors [48]. - Convergence: Use diagnostic tools like the Geweke diagnostic to check chain convergence. Samples from reactions whose distributions have not converged should be discarded [46]. Visual inspection of trace and auto-correlation plots for key reactions is also recommended [47].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Sampling Process is Too Slow

Problem: Generating a sufficient number of samples for a genome-scale model takes an impractically long time.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Large, complex model | Use the OptGP sampler with parallel processing. Increase the processes argument to match the number of available CPU cores [48]. |

| Unnecessarily high thinning factor | Adjust the thinning parameter. A higher factor (e.g., 100) creates less correlated samples but increases computation. For initial tests, a lower factor can be used, but ensure convergence diagnostics are performed [48] [46]. |

| Inefficient sampler | Consider alternative algorithms. If using ACHR, test OptGP for potential speed gains, especially on multi-core systems [48] [47]. |

Issue 2: Generated Samples Are Invalid or Infeasible

Problem: The validate function returns many samples with errors (e.g., 'le' for lower bound and equality violations).

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Numerical instability in the model | Check model constraints. Ensure all reaction bounds and additional constraints are numerically stable and consistent. |

| Sampler falling into "numerical traps" | Use the sampler's built-in robustness. The sampler objects in cobrapy are designed to generate large sample sets without falling into these traps. If invalid samples are found, you can filter them out post-sampling using the validate function without rerunning the entire process [48]. |

| Incorrect constraint setup | Re-check the scenario constraints. In CFSA, ensure the constraints for the growth, production, and slow-growth scenarios are correctly applied to the model [46]. |

Issue 3: High Correlation Between Consecutive Samples

Problem: Analysis shows that subsequent samples are highly correlated, meaning the sampler is not efficiently exploring the entire solution space.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Thinning factor is too low | Increase the thinning parameter. This ensures that only every n-th iterate is recorded, reducing correlation. For final analyses, a thinning factor of 100 is recommended to create roughly uncorrelated samples [48]. |

| Insufficient number of samples | Generate more samples. The chain may not have converged. Use convergence diagnostics (e.g., Geweke, Raftery & Lewis) to determine the required number of samples [46] [47]. |

Issue 4: CFSA Does Not Yield a Reduced List of Engineering Targets

Problem: The statistical comparison returns an overwhelming number of potential targets, making experimental prioritization difficult.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficiently strict filtering parameters | Adjust statistical cut-offs. Make the criteria for the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test p-value and the minimum flux change threshold more stringent [46]. |

| Inclusion of non-biological reactions | Apply reaction category filters. Exclude reactions without associated genes, non-biological reactions (e.g., boundary, exchange), and transport reactions from the target list [46]. |

| Target redundancy | Cluster reactions. Cluster potential targets based on the correlation of their absolute fluxes across samples. This identifies reactions from the same metabolic pathway, allowing you to select a single, representative target [46]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core CFSA Workflow for Strain Design

The following diagram illustrates the step-by-step CFSA protocol for identifying metabolic engineering targets.

Detailed Protocol: Implementing the CFSA Workflow

Step 1: Define Sampling Scenarios Configure your Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) for three distinct sampling scenarios [46]:

- Growth Scenario: Constrain the model to achieve a high growth rate (e.g., >90% of the maximum growth rate predicted by FBA).

- Production Scenario: Constrain the model to achieve a high production rate for your target compound (e.g., >90% of its maximum theoretical production).

- Slow Growth Scenario: Calculate the maximum growth rate compatible with a minimal production rate and use this as an upper bound for biomass synthesis. This scenario serves as a negative control for identifying down-regulation targets. Apply parsimonious FBA constraints in this and the production scenario to limit unrealistic futile cycles.

Step 2: Perform Flux Sampling For each scenario, generate a large number of flux distributions.

- Tool: Use the

OptGPSamplerfrom thecobrapypackage [48] [46]. - Parameters: Set the

processesargument to utilize multiple CPU cores. Set athinningfactor of 100 or higher to reduce correlation between samples. - Execution: Generate thousands of samples per scenario. The number of samples should be a multiple of the number of processes.

- Validation: Use the sampler's

validate()function to check a subset of samples for feasibility. Filter out any invalid samples [48].

Step 3: Filter Potential Targets Statistically compare the flux distributions from the different scenarios to identify reactions with significantly altered fluxes.

- Statistical Test: Perform a two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test for each reaction, comparing its flux distributions between the growth and production scenarios [46].

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a Bonferroni correction to the p-values.

- Filtering Criteria: Select reactions that meet the following criteria:

- Statistically significant difference (e.g., corrected p-value < 0.05 and KS-statistic above a threshold).

- Absolute flux change between scenarios exceeds a user-defined threshold.

- The reaction is associated with a gene (has a Gene-Protein-Reaction association).

- The reaction is not essential for growth.

- The reaction flux does not strongly correlate with biomass flux.

Step 4: Classify Interventions Categorize the filtered reactions into genetic intervention types.

- Over-expression Target: The mean fold change of the reaction's flux (comparing production to growth scenario) is greater than 1 [46].

- Down-regulation Target: The mean fold change is less than 1 [46].

- Knock-out Target: A down-regulation target where the associated gene is non-essential [46].