Advanced Screening Methods for Amino Acid Overproducers: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern screening strategies for amino acid overproducing strains, which are crucial for advancing microbial fermentation in biomedical and pharmaceutical industries.

Advanced Screening Methods for Amino Acid Overproducers: From Foundational Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

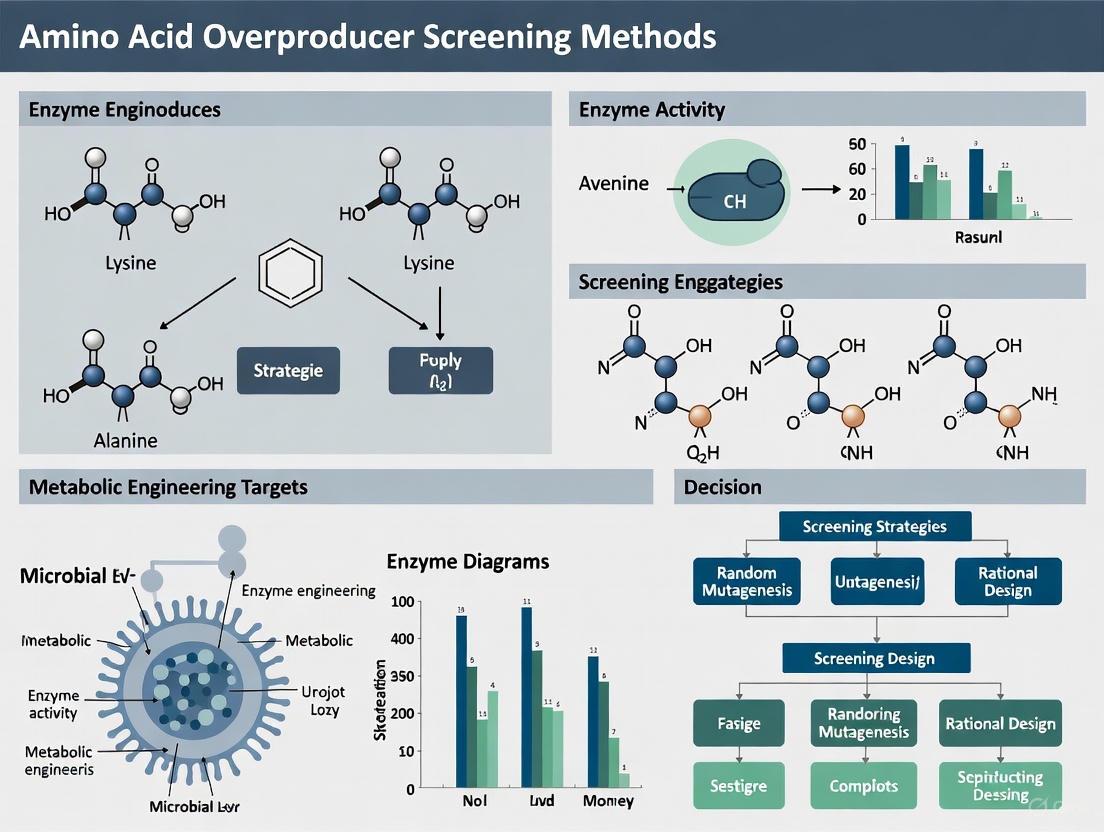

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern screening strategies for amino acid overproducing strains, which are crucial for advancing microbial fermentation in biomedical and pharmaceutical industries. Covering foundational principles to cutting-edge methodologies, we explore auxotrophic, biosensor, and innovative translation-based screening systems. The content is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing core intents from exploratory concepts and methodological applications to troubleshooting and comparative validation. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select, optimize, and implement high-throughput screening strategies that enhance accuracy, efficiency, and applicability across diverse microbial hosts for producing both standard and nonstandard amino acids.

The Essential Framework: Understanding Amino Acid Overproduction and Screening Principles

The Critical Role of Microbial Fermentation in Global Amino Acid Production

Microbial fermentation stands as a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology, serving as the primary method for the global production of amino acids. These molecules are indispensable across diverse sectors, including pharmaceuticals, animal nutrition, food fortification, and cosmetics [1]. The process leverages the natural metabolic capabilities of microorganisms—such as bacteria, yeast, and fungi—to convert organic substrates into high-value amino acids [1]. The global market for fermented amino acid complexes is substantial and growing, projected to rise from USD 17,948.2 million in 2025 to USD 31,505.4 million by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.8% [2]. This growth is largely driven by the scalability, efficiency, and sustainability of microbial fermentation compared to chemical synthesis or direct extraction methods [3].

The efficiency of microbial fermentation hinges on the development and application of advanced screening methods and metabolic engineering to create robust microbial strains capable of high-yield production. Techniques such as atmospheric and room-temperature plasma (ARTP) mutagenesis and high-throughput screening using synthetic biology tools are revolutionizing the selection of amino acid overproducers [3]. This document details the applications, quantitative data, and experimental protocols that underpin microbial amino acid production, providing a framework for researchers engaged in strain development and process optimization.

Table 1: Global Fermented Amino Acid Complex Market Overview

| Metric | Value | Time Period/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Market Value (2025) | USD 17,948.2 Million | Estimated |

| Market Value (2035) | USD 31,505.4 Million | Forecasted |

| Forecast CAGR | 5.8% | 2025 to 2035 |

| Leading Product Type | Essential Amino Acids | 38% market share in 2025 |

| Leading Source | Microbial Fermentation | 54% market share in 2025 |

| Fastest-Growing Source | Algal Fermentation | 8.5% CAGR (2025-2035) |

Applications and Industrial Impact

Amino acids produced via microbial fermentation find critical applications in numerous industries. In animal nutrition, which holds the largest application share (28%), fermented amino acids like lysine, methionine, and threonine are essential for optimizing feed efficiency and reducing antibiotic reliance [2]. The dietary supplements and sports nutrition sector is the fastest-growing application, expanding at a CAGR of 8.4%, driven by demand for branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) such as L-valine for muscle recovery and metabolic health [3] [2].

Beyond traditional sectors, emerging research highlights the role of specific amino acids as sensory and nutritional signals. For instance, a deficiency in essential amino acids can trigger behavioral changes in animals, fine-tuning their olfactory systems to seek out protein-rich sources or specific bacteria that aid in nutrient absorption [4]. Furthermore, archaea like Methanothermobacter marburgensis have demonstrated the ability to excrete proteinogenic amino acids, such as glutamic acid, alanine, and glycine, under nitrogen-fixing conditions, presenting a novel biotechnological avenue [5].

Traditional food fermentation also provides a rich source of amino acids. During soy sauce fermentation, microorganisms like Aspergillus oryzae, Tetragenococcus halophilus, and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii are actively involved in producing enzymes that generate umami-associated amino acids [6]. The choice of microbial starter cultures significantly impacts the final amino acid profile, as seen in the distinct flavors of Cantonese and Japanese-type soy sauces [7] [8].

Quantitative Data and Market Analysis

The quantitative landscape of the fermented amino acid market underscores its economic and industrial significance. The following table provides a detailed segmental analysis based on product type, source, and application.

Table 2: Segmental Analysis of the Fermented Amino Acid Complex Market

| Segment | Category | Market Share (2025) / Notes | Growth Trend (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Essential Amino Acids | 38% share | 6.1% |

| Specialty Fermented Blends | 16% share | 8.2% (Fastest) | |

| Source | Microbial Fermentation | 54% share | 5.6% |

| Algal Fermentation | 12% share | 8.5% (Fastest) | |

| Application | Animal Nutrition | 28% share (Largest) | 5.1% |

| Dietary Supplements & Sports Nutrition | 26% share | 8.4% (Fastest) | |

| Cosmetics & Personal Care | 8% share | 7.1% |

Regional analysis identifies India (9.2% CAGR) and China (8.4% CAGR) as high-growth hotspots, fueled by expanding nutraceutical demand and feed industry modernization [2]. The dominance of microbial fermentation is attributed to its technological maturity and scalability, particularly for producing workhorse amino acids like L-glutamic acid and L-lysine [2]. However, high production costs and scalability challenges for certain amino acids and newer sources like algal fermentation remain significant restraints [2].

Screening Methods and Experimental Protocols

A critical step in microbial amino acid production is the development of high-yielding bacterial strains. The following section outlines a detailed protocol for screening L-valine overproducing Escherichia coli using a rare-codon-based biosensor, a method that can be adapted for other amino acids [3].

Protocol: Construction and Screening of L-Valine High-YieldingE. coli

Objective: To generate and isolate mutant strains of E. coli with enhanced L-valine production using ARTP mutagenesis and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Principle: An artificial screening marker (LESG) is constructed by replacing all L-valine codons in a target gene sequence with the rare L-valine codon GTC. In low L-valine producing cells, the rare tRNA is poorly charged, limiting the translation of the marker and its linked fluorescent protein. In high-producing cells, sufficient intracellular L-valine ensures charged tRNA availability, enabling fluorescent protein expression. Mutants with elevated fluorescence are thus indicative of high L-valine yield [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli DB-1-1 [3].

- Plasmid Vector: pUC-57 [3].

- Growth Media:

- LB Medium: 10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, pH 7.2 [3].

- Seed Medium: 10 g/L polypeptone, 5 g/L yeast powder, 2.5 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L glucose, 6.5 g/L ground beef [3].

- Fermentation Medium: 6 g/L glucose, 2.2 g/L yeast powder, 1.25 g/L phosphoric acid, 1.125 g/L KCl, 0.41 g/L MgSO₄, 0.019 g/L FeSO₄, 0.004 g/L MnSO₄·H₂O, 0.01 g/L vitamin B3 [3].

- Antibiotic: Ampicillin (25 μg/mL) [3].

- Inducer: Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 0.6 mM [3].

- Equipment: ARTP mutagenesis system, Flow Cytometer (for FACS), UV Spectrophotometer, Bioreactor or Fermenter [3].

Procedure:

Construction of Fluorescent Expression Vector (pUC-57-LESG):

- Identify a gene sequence (e.g., levE) with a high proportion of L-valine codons from the host strain's genome.

- Synthesize a gene fragment where all L-valine codons are replaced with the rare codon GTC. Fuse this fragment to a gene encoding a stable fluorescent protein (e.g., StayGold).

- Ligate the synthesized LESG fragment into the pUC-57 plasmid at the EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites.

- Transform the constructed plasmid into competent E. coli DB-1-1 cells. Verify positive clones and plasmid integrity using colony PCR and DNA sequencing [3].

ARTP Mutagenesis:

- Inoculate recombinant E. coli DB-1-1 (carrying pUC-57-LESG) into LB medium with ampicillin and grow to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.8) at 37°C and 200 rpm.

- Add IPTG (0.6 mM) to induce fluorescent protein expression and incubate for 10-12 hours at 25°C and 200 rpm.

- Spread 10 μL of the induced culture onto a sterilized metal slide.

- Subject the cells to ARTP irradiation at 120 W power and a helium flow rate of 10 SLM. Test a range of exposure times (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 minutes) to determine the optimal mutation rate [3].

High-Throughput Screening via FACS:

- After mutagenesis, resuspend and dilute the cells.

- Use a flow cytometer to sort the mutant library, gating for cells with the highest fluorescence intensity.

- Plate the sorted cells onto LB agar plates containing ampicillin and incubate to obtain single colonies [3].

Validation with Flask Fermentation:

- Inoculate single, highly fluorescent colonies into seed medium and grow overnight.

- Transfer the seed culture to fermentation medium and incubate for 24-48 hours at 37°C and 200 rpm.

- Measure L-valine titer in the culture broth using validated analytical methods like HPLC. Compare the yield to the wild-type strain to identify superior mutants [3].

Bioreactor Scale-Up:

- For the most promising mutant, perform a fed-batch fermentation in a 5 L bioreactor using optimized conditions to achieve high-titer production, as demonstrated by a final titer of 84.1 g/L of L-valine in 24 hours [3].

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables the efficient screening of a large mutant library. The study cited achieved a sorting efficiency of 59.5% for highly fluorescent cells, with 62.5% of those screened showing improved L-valine production, resulting in a 23.1% increase in fermentation titer for the best mutant [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents, their sources, and critical functions based on the protocols and studies cited in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Amino Acid Production and Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Source / Note |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DB-1-1 Strain | High-yielding production host for L-valine. | Mutant E. coli strain [3]. |

| pUC-57 Plasmid | Cloning vector for constructing the expression plasmid carrying the screening marker. | Common lab vector [3]. |

| ARTP Mutagenesis System | Instrument for generating diverse mutant libraries via physical mutagenesis; higher mutation rate than traditional methods. | Used with parameters: 120 W, 10 SLM He flow [3]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Equipment for high-throughput screening and isolation of high-fluorescing (and thus high-producing) mutant cells. | Critical for screening efficiency [3]. |

| Aspergillus oryzae Strain 3.042 | Fungal starter culture (koji mold) used in traditional fermentation to produce proteolytic and amylolytic enzymes. | Used in soy sauce koji production [7]. |

| Tetragenococcus halophilus | Lactic acid bacterium dominant in the moromi stage of soy sauce fermentation; contributes to flavor and amino acid release. | Identified via metagenomics [6]. |

| Zygosaccharomyces rouxii | Salt-tolerant yeast used as a starter in Japanese-style soy sauce; contributes to aroma and amino acid metabolism. | Starter culture [7]. |

| Methanothermobacter marburgensis | Methanogenic archaeon shown to excrete amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid, alanine) under N₂-fixing conditions. | DSM 2133 [5]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Metabolic Pathways

High-Throughput Screening Workflow for Amino Acid Overproducers

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the screening protocol described in Section 4.1, from vector construction to the isolation of validated high-yield strains.

Key Microbial Interactions in a Traditional Fermentation Ecosystem

This diagram summarizes the functional roles of dominant microorganisms and their contributions to amino acid metabolism during a multi-stage fermentation process, such as soy sauce production [7] [6].

The global amino acid market, valued at USD 28 billion in 2021, relies heavily on microbial fermentation, which accounts for approximately 80% of total production [9]. The efficiency of this process hinges on obtaining high-performance microbial cell factories (MCFs) capable of overproducing target amino acids [9]. These industrial strains are primarily derived from screening enormous mutant libraries, making the identification of optimal screening strategies a critical research focus [9]. An ideal screening system must simultaneously satisfy three core requirements: high throughput to rapidly process ever-expanding libraries, high accuracy to minimize false positives and false negatives, and broad universality to accommodate diverse amino acids and non-standard analogs [9]. This application note delineates the essential components of such ideal screening systems, providing structured data comparisons, detailed protocols, and visual workflows to advance amino acid overproducer research.

Core Requirements of an Ideal Screening System

Quantitative Comparison of Screening Strategy Performance

The performance of different screening strategies can be quantitatively evaluated across several critical parameters. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major screening approaches used in amino acid overproducer development.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Amino Acid Screening Strategies

| Screening Strategy | Throughput Capacity | Accuracy/Fidelity | Universality | Target Amino Acids | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strain-Based [9] | Medium | Medium | Low | L-His, L-Trp [9] | Limited to specific amino acids; two-step process |

| Transcription Factor Biosensors [9] [10] | High | Medium-High | Medium | L-Lys, L-Thr, L-Glu, L-Trp [9] [10] | Cross-reactivity with structurally similar amino acids [10] |

| Rare Codon-Based Translation [9] [3] | High | High | High | L-Val, L-Leu, L-Pro, L-Ser, L-Arg [9] [3] | Requires genetic engineering of screening marker |

| Amino Acid Analog-Based [9] | Medium | Low-Medium | Low | L-Val, L-Ile, L-Pro, L-Met, L-Phe [9] | Toxicity complications; mutant survival issues [3] |

Essential Characteristics of Optimal Systems

Based on comparative analysis, an ideal screening system should embody four essential characteristics. First, it must offer high throughput to rapidly screen vast mutant libraries exceeding 100,000 clones, enabling genome-wide studies of metabolic regulators within weeks rather than years [11] [9]. Second, it requires high fidelity with robust signal-to-background ratios and excellent Z'-factor values (>0.7) to correctly identify true overproducers while minimizing false positives [9] [12]. Third, the system must demonstrate operational simplicity with minimal steps, no requirement for specialized equipment, and compatibility with automation [9]. Finally, broad universality is essential for application across various proteinogenic amino acids, non-standard amino acids, and diverse microbial hosts with industrial potential [9].

Advanced Screening Methodologies and Protocols

Rare Codon-Based Screening for L-Valine Overproducers

This protocol describes the construction and screening of L-valine high-yielding Escherichia coli using an artificial screening marker based on rare codon usage [3].

Principle and Workflow

The method leverages genetic code redundancy and the differential translation rates of synonymous codons. Common codons recognized by abundant tRNAs enable efficient translation, while rare codons limit translation efficiency. During amino acid deficiency, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases struggle to charge rare tRNA isoacceptors, stalling translation of genes containing rare codons. In high-yield producers with sufficient intracellular amino acid levels, normal translation proceeds despite codon bias, allowing expression of fluorescent markers [3].

Diagram: Rare Codon Screening Workflow for L-Valine Overproduction

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Rare Codon Screening

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli DB-1-1 | L-valine production strain | Host organism for engineering | Laboratory stock [3] |

| pUC-57 plasmid | Cloning vector | Carries engineered screening marker | Commercial source [3] |

| StayGold fluorescent protein | Stable green fluorescent protein | Reporter for screening | NCBI database [3] |

| ARTP mutagenesis system | 120 W, 10 SLM helium | Creates diverse mutant library | Commercial system [3] |

| Flow cytometer | FACS capability | High-throughput sorting of mutants | Commercial system [3] |

| LB medium | 10 g/L peptone, 10 g/L NaCl, 5 g/L yeast extract | Bacterial cultivation | Standard formulation [3] |

| Fermentation medium | 60 g/L glucose, minerals, vitamins | L-valine production evaluation | Custom formulation [3] |

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Codon Usage Analysis: Retrieve the E. coli DB-1-1 genome sequence from NCBI database. Analyze codon frequency and identify gene sequences for extracellular proteins with the highest proportion of L-valine codons [3].

- Screening Marker Construction: Select the green fluorescent protein StayGold gene from NCBI. Replace all L-valine codons in the target gene with the rare GTC codon (23% replacement frequency). Synthesize the gene fragment (e.g., Kingsley Biotechnology) and clone into EcoRI-and HindIII-digested pUC-57 plasmid to create pUC-57-LESG [3].

- Strain Transformation: Introduce pUC-57-LESG into competent E. coli DB-1-1 cells. Select positive recombinant colonies on LB medium with 25 μg/mL ampicillin. Incubate at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm [3].

- ARTP Mutagenesis: Culture recombinant strains to logarithmic phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.8). Add 0.6 mM IPTG inducer and incubate at 25°C for 10 h at 200 rpm. Subject bacterial samples to ARTP irradiation at five time intervals (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 min) with parameters set to 120 W incident power and 10 SLM helium flow rate [3].

- High-Throughput Sorting: Analyze mutants using flow cytometry. Sort cells exhibiting elevated fluorescence intensity. In validation studies, this approach achieved 59.5% sorting efficiency, identifying 143 highly fluorescent strains from 240 total [3].

- Fermentation Validation: Cultivate promising mutants in 5 L fermenters with optimized fermentation medium. Monitor L-valine production over 24 hours. The top-performing mutant achieved 84.1 g/L L-valine titer, representing a 23.1% improvement over wild-type strain [3].

Transcription Factor Biosensor Engineering for Multiple Amino Acids

This protocol details the development of transcription factor-based biosensors for sensitive detection of L-glutamic acid, L-lysine, and L-threonine through directed evolution of YpItcR [10].

Principle and Workflow

Transcription factor biosensors consist of a transcriptional regulator and its cognate promoter controlling a reporter gene. The native YpItcR biosensor from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis recognizes itaconic acid (ITA), a structural analog of many amino acids that doesn't exist in normal metabolic pathways. Through directed evolution, YpItcR mutants are created with enhanced specificity for target amino acids while maintaining minimal response to ITA, eliminating interference during high-throughput screening [10].

Diagram: Transcription Factor Biosensor Engineering Workflow

Materials and Reagents

- YpItcR/Pccl biosensor system from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis [10]

- Error-prone PCR kit (e.g., EmeraldAmp MAX PCR Master Mix) [10]

- Gibson assembly kit (e.g., Hieff Clone One Step Cloning Kit) [10]

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorter for high-throughput screening [10]

- Microplate readers for fluorescence detection [10]

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics for selection [10]

Step-by-Step Protocol

- Biosensor Construction: Clone the native YpItcR-based ITA biosensor, comprising the transcriptional regulator YpItcR and its promoter Pccl, into an appropriate E. coli vector system. Validate functionality by measuring reporter gene activation in response to ITA [10].

- Directed Evolution Library Creation: Perform error-prone PCR on the YpItcR gene sequence using low-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., EmeraldAmp MAX PCR Master Mix) to introduce random mutations. Assemble mutated fragments using Gibson assembly and transform into E. coli MG1655 to create a comprehensive mutant library [10].

- Dual Screening Strategy: Screen the mutant library using a dual selection approach. First, identify mutants showing strong reporter activation in response to the target amino acid (L-glutamic acid, L-lysine, or L-threonine). Counter-screen these hits to eliminate mutants maintaining strong response to ITA. This ensures specificity for the target amino acid [10].

- Mutant Characterization: Isolate specific mutants with desired properties: YpItcR-ᵢGlu for L-glutamic acid, YpItcR-ᵢLys for L-lysine, and YpItcR-ᵢThr for L-threonine. Quantitatively characterize biosensor performance by measuring dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity against structurally similar amino acids [10].

- Application to Strain Screening: Implement optimized biosensors in high-throughput campaigns to screen mutant libraries for amino acid overproducers. Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting to isolate clones with highest reporter signal, indicating superior amino acid production capabilities [10].

Technological Integration and Future Perspectives

Emerging Technologies Enhancing Screening Performance

The integration of advanced technologies is pushing the boundaries of screening system capabilities. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are rapidly reshaping the global high-throughput screening market by enhancing efficiency, lowering costs, and driving automation in drug discovery and molecular research. AI enables predictive analytics and advanced pattern recognition, allowing researchers to analyze massive datasets generated from HTS platforms with unprecedented speed and accuracy [11]. For instance, random forest algorithms have successfully predicted translation-enhancing peptide activities based on sequence features, demonstrating strong correlation with experimental measurements [13].

Ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) platforms represent another significant advancement, capable of testing millions of compounds daily compared to 10,000-100,000 for conventional HTS [14] [15]. These systems utilize high-density microwell plates (1536-well format) with volumes of 1-2 μL and advanced microfluidics, though fluid handling remains a technical challenge [15]. The cell-based assays segment continues to dominate the technology landscape, holding 39.4% market share in 2025 due to superior physiological relevance and predictive accuracy in early drug discovery [14].

Market Outlook and Regional Adoption

The global high-throughput screening market is projected to grow from USD 26.12 billion in 2025 to USD 53.21 billion by 2032, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of 10.7% [11]. North America leads the market with 39.3% share in 2025, while the Asia-Pacific region shows the fastest growth with 24.5% market share, driven by expanding pharmaceutical industries and increasing R&D investments in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea [11]. This growth is further supported by strategic collaborations between technology providers and drug developers aimed at streamlining discovery pipelines [14].

Ideal screening systems for amino acid overproducers must balance three fundamental requirements: high throughput to efficiently process large mutant libraries, high accuracy to ensure reliable identification of true positives, and broad universality to accommodate diverse amino acids and microbial hosts. The methodologies detailed in this application note—including rare codon-based screening and engineered transcription factor biosensors—provide robust frameworks satisfying these criteria. As the field advances, integration of artificial intelligence, ultra-high-throughput platforms, and improved biosensor designs will further enhance screening capabilities. Researchers should select and optimize screening strategies based on their specific target amino acids, host organisms, and available infrastructure, while considering the quantitative performance metrics and implementation protocols outlined herein.

The global amino acid market is a multi-billion dollar industry experiencing robust growth, propelled by diverse applications spanning nutrition, pharmaceuticals, and industrial biotechnology. This expansion is closely linked to advancements in microbial fermentation technologies and the parallel development of sophisticated screening methods for high-yield amino acid overproducers.

Table 1: Global Amino Acids Market Projections (2025-2035)

| Metric | Value | Source/Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size (2025) | USD 29.9 - 33.72 Billion | [16] [17] |

| Projected Market Size (2034/2035) | USD 66.35 - 75.3 Billion | [16] [18] |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 8.3% - 9.7% | [16] [17] |

| Dominant Regional Market (2024) | Asia-Pacific (49% revenue share) | [17] |

| Leading Application Segment (2024) | Food & Dietary Supplements (57% revenue share) | [17] |

Key market drivers include rising consumer health awareness, a shift towards protein-rich and plant-based diets, and growing demand from the pharmaceutical and animal feed industries [16] [18]. Microbial fermentation dominates production, contributing to approximately 80% of global amino acid yield and aligning with trends toward sustainable and bio-based manufacturing [9]. This reliance on fermentation underscores the critical need for high-performance microbial cell factories, driving intensive research into advanced screening methodologies for amino acid overproducers [9] [19].

Analytical and Screening Protocols for Amino Acid Overproducers

The identification and development of high-yield microbial strains are fundamental to the amino acid industry. The following protocols detail established and emerging methodologies for screening amino acid overproducers.

Protocol 1: Rare Codon-Based Screening for Amino Acid Overproducers

This modern screening strategy exploits the natural competition for amino acids between common and rare codons during protein translation, providing a high-throughput and accurate method for strain selection [19].

- Principle: Under amino acid starvation, the charging level of tRNA isoacceptors corresponding to rare codons drops dramatically, halting the translation of genes containing these codons. In an amino acid overproducer, the abundant intracellular amino acid pool ensures adequate charging of even the rare tRNAs, allowing for the successful translation of rare codon-rich reporter genes and enabling cell survival or signal detection [19].

- Applications: Successfully applied to screen for overproducers of L-leucine, L-arginine, and L-serine in E. coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum [19].

- Procedure:

- Reporter Gene Engineering: Replace common codons in a reporter gene (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene like

kanRor a fluorescent protein gene) with synonymous rare codons for the target amino acid. For example, replace common leucine codons with the rare CTA codon in E. coli [19]. - Strain Transformation: Introduce the engineered rare codon-rich reporter construct into the mutant library of the host strain (e.g., generated via ARTP mutagenesis) [19].

- Selection/Screening:

- Selection System: Plate transformed cells on medium containing the corresponding antibiotic. Only strains producing sufficient target amino acid to translate the rare codon-rich resistance protein will form colonies [19].

- Screening System: For color-based screening, colonies expressing a rare codon-rich chromogenic protein (e.g., prancerpurple protein) will show enhanced color intensity if they are overproducers [19].

- Validation: Confirm the amino acid titer of selected strains using quantitative methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [19].

- Reporter Gene Engineering: Replace common codons in a reporter gene (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene like

Protocol 2: Biosensor-Based Screening Using Transcription Factor-Regulated Reporters

This strategy utilizes natural cellular sensing mechanisms to link intracellular amino acid concentration to a detectable fluorescent signal, enabling high-throughput screening.

- Principle: A transcription factor (TF) that naturally binds to a specific amino acid is used to regulate the expression of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, YFP). When the target amino acid is present, it binds to the TF, causing a conformational change that allows the TF to activate or repress the promoter controlling the reporter gene. The resulting fluorescent signal is proportional to the intracellular amino acid concentration [9].

- Applications: Widely applicable for various amino acids. Examples include using the Lrp-regulated promoter

PbrnFfor branched-chain amino acids (Leu, Ile, Val) and the LysG-regulated promoterPlysEfor basic amino acids (Lys, Arg, His) in C. glutamicum [9]. - Procedure:

- Biosensor Construction: Genetically integrate a reporter gene (e.g.,

gfp,eyfp) under the control of an amino acid-responsive promoter and its cognate transcription factor into the host chromosome [9]. - Library Cultivation: Grow the mutant library in microtiter plates or on solid medium under appropriate conditions.

- Signal Detection: Measure the fluorescence intensity of individual colonies or cultures using a fluorescence plate reader, flow cytometer, or fluorescence microscopy.

- Isolation and Validation: Isolate clones displaying the highest fluorescence and validate amino acid production levels through HPLC [9].

- Biosensor Construction: Genetically integrate a reporter gene (e.g.,

Protocol 3: Auxotrophic Strain-Based Co-culture Screening

This classical method relies on the growth dependency of an auxotrophic indicator strain on amino acids produced by a library of potential overproducers.

- Principle: An auxotrophic strain, which cannot synthesize a specific essential amino acid, will only grow if that amino acid is provided externally. When co-cultured with a production strain from a mutant library, the growth of the auxotroph serves as a biosensor for the amount of amino acid secreted into the medium [9].

- Applications: A two-step or co-culture system for identifying overproducers of amino acids like L-tryptophan and L-histidine [9].

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Generate a mutant library of the production strain (e.g., via chemical mutagenesis). Prepare an indicator strain with a knockout in a gene essential for synthesizing the target amino acid (e.g.,

ΔhisLfor histidine auxotrophy) [9]. - Co-culture Setup: Spot or streak the production library and the auxotrophic indicator strain in close proximity on a solid minimal medium that lacks the target amino acid.

- Growth Observation: Incubate and observe for a "halo" of growth of the indicator strain around colonies of amino acid overproducers.

- Recovery and Validation: Pick the production colonies surrounded by the largest halos and validate their productivity in liquid culture using HPLC.

- Preparation: Generate a mutant library of the production strain (e.g., via chemical mutagenesis). Prepare an indicator strain with a knockout in a gene essential for synthesizing the target amino acid (e.g.,

Table 2: Comparison of Amino Acid Overproducer Screening Methods

| Method | Throughput | Fidelity | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare Codon-Based [19] | High | High | Minimizes non-specific cellular stress; highly tunable via codon frequency. | Requires sophisticated genetic engineering of reporter genes. |

| Biosensor-Based [9] | Very High | Moderate to High | Enables real-time, quantitative monitoring in live cells. | Potential for false positives from regulator mutations; dynamic range can be limited. |

| Auxotrophic Co-culture [9] | Moderate | Moderate | Conceptually simple; requires no specialized equipment for initial screening. | Lower throughput; two-step process can be laborious; growth cross-feeding can be complex. |

| Toxic Analogue Selection [19] | High | Low to Moderate | Powerful for direct selection without reporters. | High false-positive rate from detoxification mechanisms; analogues can have pleiotropic toxic effects. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Amino Acid Overproducer Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function in Screening | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

Rare Codon-Engineered Antibiotic Resistance Genes (e.g., kanR-RC29) |

Selection marker; translation and thus antibiotic resistance is dependent on intracellular amino acid supply. | Selection for L-leucine overproducers in E. coli using a kanR gene where all Leu codons are replaced with the rare CTA codon [19]. |

Amino Acid-Responsive Promoter Reporters (e.g., PlysE-eyfp) |

Fluorescent biosensor; links amino acid concentration to measurable fluorescence output. | Screening for L-lysine overproducers in C. glutamicum using the LysG-regulated PlysE promoter driving eyfp expression [9]. |

| Amino Acid Auxotrophic Strains | Biosensor strain; growth indicates the presence and quantity of the target amino acid in the environment. | Identifying L-histidine overproducers by using an E. coli JW2000 ΔhisL indicator strain in a co-culture assay [9]. |

| Toxic Amino Acid Analogues (e.g., 4Azaleucine) | Selective agent; overproducers of the native amino acid can outcompete the analogue for incorporation into proteins, surviving the selection. | Traditional selection for L-leucine overproducers using the toxic analogue 4-azaleucine [19]. |

| Chromatography Standards (e.g., pure amino acids) | Analytical calibration; essential for accurate quantification of amino acid titers in validation steps. | Used in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify amino acid concentration in culture supernatants from selected strains [19] [20]. |

The expanding multi-billion dollar amino acid industry is intrinsically linked to technological progress in microbial strain development. The shift from traditional methods like toxic analogue selection towards more sophisticated, genetically encoded systems—such as transcription factor-based biosensors and rare codon-based selection—marks a significant evolution in the field. These advanced screening protocols enable higher throughput, greater accuracy, and minimal side-effects on cellular physiology, thereby accelerating the development of high-performance microbial cell factories. As demand for amino acids continues to grow across food, feed, and pharmaceutical sectors, these refined screening methods will play an increasingly vital role in optimizing production efficiency, reducing costs, and driving innovation in the bio-based economy.

Application Notes

Amino acids represent a multibillion-dollar market with applications spanning food, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics, with the global market reaching $28 billion in 2021 and expected continued growth [9]. Microbial fermentation contributes to approximately 80% of global amino acid production, making the development of high-performance microbial cell factories (MCFs) a critical industrial objective [9]. The key to advancing this field lies in innovative screening strategies that can rapidly and accurately identify amino acid overproducers from vast mutant libraries.

Traditional screening methods, such as the use of toxic amino acid analogs, face significant limitations including off-target cellular toxicity and the development of microbial resistance mechanisms that are unrelated to production titers [19] [21]. Recent advances have introduced novel approaches based on fundamental biological principles, particularly exploiting the relationship between intracellular amino acid pools and protein translation fidelity. These methods leverage codon usage bias, transcription factor biosensors, and auxotrophic co-culture systems to directly link cellular metabolic states with easily detectable phenotypic markers [9] [19].

The most promising new strategies include translation-based screening systems that utilize rare codons, which depend on charged tRNA availability that directly correlates with intracellular amino acid concentration [22] [19]. When implemented with fluorescent reporters or antibiotic resistance markers, these systems enable high-throughput screening of mutant libraries using flow cytometry or simple selection plates, dramatically improving screening efficiency and positive clone identification rates compared to conventional methods [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Amino Acid Overproducer Screening Strategies

| Screening Strategy | Key Principle | Target Amino Acids | Throughput | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strain-Based | Growth correlation with amino acid concentration [9] | L-His, L-Trp, others [9] | Moderate | Simple principle, can be coupled with fluorescence |

| Transcription Factor Biosensors | Natural TF-promoter interactions [9] [23] | L-Lys, L-Val, L-Cys, others [9] | High | Highly specific, can be engineered |

| Rare Codon-Based | tRNA charging depends on amino acid abundance [22] [19] | L-Leu, L-Arg, L-Ser, L-Val [22] [19] | Very High | Analog-independent, broadly applicable |

| Amino Acid Analog-Based | Competition with toxic analogs [19] | L-Leu, L-Val, others [9] [19] | Low-Moderate | Established methodology |

| FRET-Based Sensors | Conformational change in binding proteins [9] | L-Lys, L-Met, L-Gln [9] | High | Real-time monitoring capability |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Rare Codon Screening for L-Valine Production in E. coli [22]

| Parameter | Wild-Type Strain | Mutant Strain (DK2) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Positivity Rate | Baseline | 62.5% | - |

| Fluorescence Intensity | Baseline | Significantly Increased | - |

| L-Valine Titer (24h) | Baseline | 84.1 g/L | 23.1% increase |

| Screening Efficiency | - | 59.5% of sorted strains were highly fluorescent | - |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rare Codon-Based Screening for L-Valine Overproducers

Background and Principle This protocol exploits the fundamental biological relationship between codon usage bias and intracellular amino acid pools. Rare codons (e.g., GTC for L-valine in E. coli) require corresponding rare tRNAs that cannot be fully charged under amino acid starvation conditions [22] [19]. When intracellular amino acid concentrations are high, these rare tRNAs become charged, enabling efficient translation of reporter genes containing rare codon-rich sequences. By linking this translation efficiency to fluorescent output, high-producing strains can be identified through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [22].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Rare Codon Screening

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strain | E. coli DB-1-1 | Wild-type production host for engineering |

| Expression Vector | pUC-57 with Ptrc promoter | Shuttle vector for reporter gene expression |

| Fluorescent Protein | StayGold | High-stability reporter for screening |

| Target Genes | levE CDS | Valine-rich protein sequence for codon replacement |

| Culture Medium | LB (10 g/L peptone, 10 g/L NaCl, 5 g/L yeast extract) | Standard microbial growth medium |

| Antibiotic | Ampicillin (25 μg/mL) | Selection pressure for plasmid maintenance |

| Inducer | IPTG (0.6 mM) | Induction of reporter gene expression |

| Mutagenesis System | Atmospheric Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) | Physical mutagenesis for library generation |

| Screening Instrument | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-throughput screening based on fluorescence |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Codon Usage Frequency Analysis

- Analyze the E. coli genome sequence using the NCBI database to identify the rarest codon for the target amino acid [22]. For L-valine, GTC is identified as the appropriate rare codon.

- Screen the genome for protein sequences with the highest proportion of the target amino acid codons to identify optimal genes for rare codon incorporation.

Fluorescent Reporter Vector Construction

- Select the StayGold fluorescent protein gene and levE CDS as reporter genes due to their high valine content [22].

- Synthesize gene fragments with all L-valine codons replaced by GTC (approximately 23% replacement frequency) through commercial gene synthesis.

- Clone the synthesized rare codon-rich fragments into the pUC-57 plasmid using EcoRI and HindIII restriction sites, creating the pUC-57-LESG expression vector.

- Verify construct integrity through colony PCR and nucleotide sequencing.

Strain Mutagenesis and Transformation

- Subject the wild-type E. coli DB-1-1 to Atmospheric Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) mutagenesis to generate genetic diversity [22].

- Transform the mutagenized library with the pUC-57-LESG vector using standard heat-shock transformation protocols.

- Plate transformed cells on LB agar containing 25 μg/mL ampicillin and incubate at 37°C overnight for colony development.

Expression Induction and Fluorescence Screening

- Inoculate positive recombinant colonies into 50 mL of LB medium with 25 μg/mL ampicillin, starting at OD600 of 0.3.

- Incubate at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 12 hours.

- Add 0.6 mM IPTG to induce fluorescent protein expression and continue incubation at 25°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 12 hours.

- Measure fluorescence intensity using a plate reader or analyze using flow cytometry.

High-Throughput Sorting and Validation

- Sort cells exhibiting increased fluorescence intensity using FACS [22].

- Collect the top 10-15% of fluorescent clones for further validation.

- Assess L-valine production titer of sorted clones using fermentation in optimized medium and quantitative analysis (HPLC).

- Validate performance in bioreactor systems with the mutant strain E. coli DK2 achieving 84.1 g/L L-valine in 24 hours [22].

Protocol 2: Biosensor-Based Screening Using Transcription Factors

Background and Principle This approach utilizes natural transcription factors that undergo conformational changes upon binding specific amino acids, subsequently activating promoter regions linked to reporter genes [9] [23]. For example, the Lrp-regulated promoter PbrnF can be fused with eyfp for branched-chain amino acid detection, while LysG-regulated PlsyE promoters respond to multiple amino acids including L-lysine, L-arginine, and L-histidine [9].

Materials and Reagents

- Transcription Factors: Lrp (branched-chain amino acids), LysG (basic amino acids), TyrR (aromatic amino acids)

- Promoters: PbrnF (L-valine responsive), PlysE (L-lysine responsive), Ptyr/Pmtr (L-phenylalanine responsive)

- Reporter Genes: eyfp, mCherry, gfp

- Culture Conditions: Minimal media to avoid background amino acid interference

Step-by-Step Procedure

Biosensor Construction

- Clone the appropriate amino acid-responsive promoter (e.g., PbrnF for L-valine) upstream of a fluorescent reporter gene (eyfp) in a shuttle vector [9].

- Co-express the corresponding transcription factor (Lrp) either chromosomally or from the same vector.

Library Transformation and Cultivation

- Transform the mutant library with the biosensor construct.

- Culture transformed cells in minimal medium under selective conditions.

Screening and Sorting

- Measure fluorescence intensity during mid-log phase using plate readers or flow cytometry.

- Sort high-fluorescence clones for further validation.

- Confirm amino acid overproduction through HPLC analysis of culture supernatants.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Amino Acid Overproducer Screening

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Systems | StayGold fluorescent protein, GFP, eyfp, mCherry, PrancerPurple | Visual detection of amino acid abundance |

| Selection Markers | Rare codon-modified kanR, ampR | Antibiotic-based selection linked to amino acid production |

| Induction Systems | IPTG-inducible Ptrc promoter | Controlled expression of screening markers |

| Mutagenesis Tools | ARTP (Atmospheric Room Temperature Plasma) | Library generation through random mutagenesis |

| Screening Instruments | FACS, plate readers, HPLC | High-throughput sorting and validation |

| Host Strains | E. coli, Corynebacterium glutamicum | Industrial production platforms for amino acids |

| Biosensor Components | Lrp-regulated promoters, LysG-regulated promoters | Natural amino acid sensing systems |

Screening in Action: Comparative Analysis of Modern Methodologies and Their Practical Implementation

Application Notes and Protocols

Within the framework of developing advanced amino acid overproducer screening methods, auxotrophic strains present two powerful, complementary paradigms. First, they can be engineered into biosensors for the high-throughput selection of high-yielding mutants from vast libraries. Second, they can be assembled into synthetic microbial consortia based on mutualistic cross-feeding, enabling stable, long-term bioproduction processes. This document details the experimental workflows for implementing a Two-Step Auxotrophic Screening system for L-valine overproducers and for constructing and tuning a Two-Strain Auxotrophic Co-culture. These protocols are designed for researchers and scientists engaged in metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and drug development, where the demand for efficient strain improvement and robust fermentation systems is paramount.

Methodology and Workflows

Two-Step Auxotrophic Screening for Amino Acid Overproducers

This protocol describes a method for screening L-valine overproducing E. coli strains, leveraging an artificial auxotrophic marker based on rare codon usage [3] [22]. The strategy links the intracellular level of the target amino acid to the expression of a fluorescent protein, enabling high-throughput isolation of high-yielding mutants.

1.1. Principle An engineered biosensor strain is constructed where the expression of a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., StayGold) is contingent upon the intracellular concentration of a specific amino acid (e.g., L-valine). This is achieved by replacing all codons for that amino acid in the reporter gene with its rare codon counterpart (e.g., GTC for L-valine) [3] [22]. In a low-yielding strain, the scarcity of charged rare tRNAs causes ribosomal stalling and low fluorescence. In a high-yielding strain, the abundant amino acid pool ensures efficient charging of the rare tRNAs, enabling full translation of the reporter gene and resulting in high fluorescence. This creates a direct, selectable link between production phenotype and fluorescence signal.

1.2. Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps for the two-step screening process:

1.3. Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Biosensor Plasmid Construction

- Procedure: Identify a bright, stable fluorescent protein (e.g., StayGold). Analyze its sequence and replace every codon for your target amino acid (e.g., L-valine) with its rarest synonymous codon in your host organism (e.g., GTC in E. coli) [3] [22]. Synthesize the modified gene fragment and clone it into a standard expression vector (e.g., pUC-57) under an inducible promoter (e.g., Ptrc).

- Notes: The replacement frequency in the cited study was 23% for L-valine codons [22].

Step 2: Host Strain Transformation

Step 3: Mutant Library Generation

- Procedure: Subject the biosensor strain to mutagenesis to create genetic diversity. Atmospheric and Room-Temperature Plasma (ARTP) is highly effective [3] [22].

- Parameters: Use an incident power of 120 W and a helium flow rate of 10 SLM. Test irradiation times from 0 to 9 minutes to determine a kill rate of 80-95% to optimize mutation efficiency.

Step 4: Reporter Gene Induction & Expression

Step 5: High-Throughput Sorting via FACS

- Procedure: Dilute the induced culture to an appropriate cell density (OD600 ~0.6-0.8). Use a Flow Cytometer equipped with a cell sorter (FACS) to analyze and sort the cell population based on fluorescence intensity [3] [22].

- Gating Strategy: Set gates to collect the top 1-5% of the most fluorescent cells.

Step 6: Validation and Fermentation

- Procedure: Plate the sorted cells and pick isolated colonies. Screen these in 96-deep well plates to confirm high production titers. The final validation step involves culturing the best candidates in controlled bioreactors (e.g., 5 L fermenters) to assess maximum titer, yield, and productivity [3] [22]. The cited study achieved an L-valine titer of 84.1 g/L in 24 hours using this method [3].

Establishing and Tuning a Two-Strain Auxotrophic Co-culture

This protocol outlines the creation of a stable, mutually dependent microbial consortium using two auxotrophic E. coli strains that cross-feed essential metabolites [24] [25]. This system is valuable for division-of-labor approaches in biomanufacturing and for studying microbial ecology.

2.1. Principle Two strains, each with a deletion in a different essential biosynthetic gene (e.g., ΔargC and ΔmetA), are co-cultured [24]. Each strain overproduces and excretes the metabolite its partner requires (arginine and methionine, respectively), but cannot produce itself. This obligate mutualism forces stable coexistence. The population ratio can be precisely tuned by exogenously adding the cross-fed metabolites, which differentially alters the growth rates of the two strains [24].

2.2. Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core logic of the cross-feeding co-culture system:

2.3. Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Strain Selection and Cultivation

- Procedure: Select two mutually auxotrophic strains (e.g., E. coli ΔargC and ΔmetA from the Keio collection) [24]. Maintain each strain in monoculture using minimal media (e.g., M9) supplemented with the required metabolite (50 µg/mL L-arginine for ΔargC and 50 µg/mL L-methionine for ΔmetA).

Step 2: Co-culture Inoculation and Steady-State

- Procedure: Inoculate a continuous bioreactor (e.g., a turbidostat set to maintain a constant OD600, like 0.5) with both strains in minimal media without supplements [24]. The initial inoculation ratio can vary widely (e.g., from 1:99 to 99:1) as the system will self-correct.

- Parameters: The culture will reach a stable equilibrium ratio (e.g., ~75:25 ΔmetA:ΔargC) within approximately 24 hours, which will persist over the long term [24]. Monitor population ratios by plating dilutions on supplemented solid media that selectively support one strain.

Step 3: Ratio Tuning via Metabolite Supplementation

- Procedure: To alter the steady-state ratio, supplement the fresh media reservoir with low concentrations of the cross-fed metabolites [24].

- Tuning Guide:

- To increase the proportion of a strain, add the metabolite it is auxotrophic for. This directly increases its growth rate.

- To decrease the proportion of a strain, add the metabolite it overproduces. This reduces its dependency on the partner, indirectly favoring the partner's growth.

- The system allows for fine-grained control, enabling population shifts from 10% to 90% of the total population for a given strain [24].

Results and Data Presentation

Quantitative Data from Case Studies

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Two-Step Auxotrophic Screening Method for L-Valine [3] [22]

| Parameter | Result / Value | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Efficiency | 59.5% | Percentage of highly fluorescent strains sorted from the mutant library (143/240). |

| Positivity Rate | 62.5% | Percentage of sorted strains confirmed as high producers in validation. |

| Fermentation Titer | 84.1 g/L | Maximum L-valine concentration achieved in a 5 L fermenter at 24 hours. |

| Titer Improvement | 23.1% | Increase in L-valine production compared to the wild-type strain. |

Table 2: Population Dynamics and Tunability in an Auxotrophic Co-culture (ΔmetA / ΔargC) [24]

| Condition | Steady-State Ratio (ΔmetA : ΔargC) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| No Supplement (Baseline) | ~75 : 25 | Consortium reaches a stable, robust equilibrium regardless of initial inoculation ratio (1:99 to 99:1). |

| Supplement with Arginine | Decreased ΔmetA | Increases growth rate of ΔargC strain, shifting balance in its favor. |

| Supplement with Methionine | Increased ΔmetA | Increases growth rate of ΔmetA strain, shifting balance in its favor. |

| Tuning Range | ~10 : 90 to ~90 : 10 | The full range of population ratios achievable through metabolite supplementation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Auxotrophic Strain Strategies

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Auxotrophic Strains | Core organisms for building biosensors or consortia. | E. coli Keio Collection single-gene knockouts (e.g., ΔargC, ΔmetA) [24]; Bacillus subtilis ΔSAS for stringent response studies [26]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Engineered genetic constructs for linking metabolite production to a detectable signal. | pUC-57-LESG (containing rare-codon-modified StayGold) [3] [22]; pESC-URA with pGAL1 for inducible expression in yeast [27]. |

| Mutagenesis Equipment | Creating genetic diversity in a production host for screening. | Atmospheric and Room-Temperature Plasma (ARTP) instrument [3] [22]. |

| High-Throughput Sorter | Isolating high-performing variants from a large library. | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) [3] [22]. |

| Controlled Bioreactors | Maintaining continuous co-cultures and validating production at scale. | Turbidostat systems for continuous culture [24]; 5 L fermenters for production validation [3]. |

| Defined Minimal Media | Cultivating auxotrophic strains and forcing cross-feeding dependencies. | M9 medium for E. coli [24]; AB minimal medium for Agrobacterium [28]; S7 medium for B. subtilis [26]. |

Discussion

The protocols outlined herein demonstrate the versatility of auxotrophic strains as foundational tools in modern biotechnology. The two-step screening method transforms a cellular burden—the inability to synthesize an essential metabolite—into a powerful selection advantage, enabling rapid mining of high-performing mutants from immense libraries that are intractable with traditional methods. The co-culture system leverages the same principle of auxotrophy to create stable, synthetic ecosystems. The ability to precisely control population ratios via simple metabolite supplementation, as predicted by robust ordinary differential equation models [24], provides an unparalleled level of process control for complex biomanufacturing tasks.

A critical consideration when designing these systems is metabolic cross-talk beyond the target amino acids. Recent evidence shows that cross-feeding in auxotrophic co-cultures can involve pathway intermediates (e.g., histidinol, L-citrulline), not just the final amino acid product [29]. This adds a layer of complexity that must be characterized for precise modeling and engineering. Furthermore, the principles of auxotrophy extend beyond bacteria, as demonstrated by their use in controlling contamination in Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation [28] and in high-throughput yeast strain engineering pipelines [27].

In conclusion, when integrated into a comprehensive Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle, auxotrophic strain-based strategies for screening and co-culture assembly significantly accelerate the development of robust microbial systems for the production of valuable biochemicals and therapeutics.

The development of high-throughput screening methods is a critical pillar in the advancement of microbial cell factories for amino acid production. Among the most powerful tools to emerge in this field are genetically encoded biosensors, which enable real-time monitoring of intracellular metabolites and facilitate the rapid selection of high-performance industrial strains [30]. This Application Note focuses on two principal biosensor architectures: Transcription Factor (TF)-Based Biosensors and Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Biosensors. We detail their operational mechanisms, provide validated protocols for their implementation in amino acid sensing, and present quantitative data on their performance, specifically for the detection of L-threonine and L-proline. These methodologies provide robust frameworks for screening amino acid overproducers, a core requirement in modern metabolic engineering and biomanufacturing.

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors for Amino Acid Sensing

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are genetically encoded devices that utilize a cell's native regulatory machinery to convert the intracellular concentration of a target metabolite into a quantifiable signal, typically fluorescence [30]. Their inherent modularity, genetic tunability, and ability to function within the host's regulatory network make them indispensable for dynamic metabolic control and high-throughput screening (HTS) [30].

Mechanism of Action

The operation of a TFB involves a sequential process [30]:

- Analyte Recognition: A transcription factor (TF) specifically binds to its target ligand (effector).

- Signal Transduction: This binding induces a conformational change in the TF, altering its affinity for a specific DNA promoter sequence.

- Output Generation: The change in DNA binding affinity either activates or represses the transcription of a downstream reporter gene, such as a fluorescent protein. The resulting fluorescence intensity is quantitatively correlated with the intracellular concentration of the target metabolite.

Diagram: Mechanism of a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor

Protocol: Development and Application of a SerR-Based Biosensor for L-Threonine and L-Proline

The following protocol describes the process for creating and utilizing a biosensor for L-threonine and L-proline, based on the engineering of the transcriptional regulator SerR [31].

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strain: Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 or an appropriate production host.

- Plasmids: Cloning and expression vectors compatible with the host strain.

- Genes: serR (wild-type and mutant serRF104I), eyfp (enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein), serE (exporter).

- Culture Media: Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) for seed culture; CGXII minimal medium for production and screening [31].

- Equipment: Microplate reader with fluorescence detection, flow cytometer for high-throughput screening, bioreactors or deep-well plates for cultivation.

Procedure

Part A: Biosensor Construction and Validation

- Sensor Assembly: Clone the mutant serRF104I gene and its native promoter (Pser) upstream of the eyfp reporter gene in a suitable plasmid vector [31].

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed biosensor plasmid into the C. glutamicum host strain.

- Dose-Response Characterization:

- Inoculate biosensor-bearing strains in CGXII medium supplemented with a gradient of L-threonine or L-proline concentrations (e.g., 0 to 100 mM).

- Grow cultures in a microplate reader at 30°C with continuous shaking.

- Measure optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (Ex/Em: ~513/527 nm for eYFP) at regular intervals.

- Calculate the fold-change in fluorescence by normalizing to the negative control (0 mM effector) and plot against effector concentration to determine the dynamic range.

Part B: High-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Variants

- Library Generation: Create mutant libraries of key biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., l-homoserine dehydrogenase, Hom, for L-threonine; γ-glutamyl kinase, ProB, for L-proline) via error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis.

- Transformation: Co-transform the biosensor plasmid and the mutant enzyme library into the production host strain.

- Screening:

- Plate the transformed library on solid CGXII medium and incubate until colonies form.

- Pick individual colonies into deep-well plates containing liquid CGXII medium and cultivate for 24-48 hours.

- Using a flow cytometer or a plate reader, measure the fluorescence intensity of each culture during the mid-exponential growth phase.

- Isolate the top 0.1-1% of clones exhibiting the highest fluorescence signals.

- Validation: Ferment selected clones in a controlled bioreactor or shake flask and quantify final L-threonine or L-proline titers using HPLC to confirm the correlation between biosensor signal and production yield [31].

Key Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the SerRF104I-Based Biosensor [31]

| Effector | Transcription Factor | Dynamic Range (Fold-Change) | Key Application | Screening Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Threonine | SerRF104I | >10-fold | HTS of Hom mutants | 25 novel Hom mutants increasing titer by >10% |

| L-Proline | SerRF104I | >10-fold | HTS of ProB mutants | 13 novel ProB mutants increasing titer by >10% |

FRET-Based Biosensors

FRET biosensors are another class of genetically encoded reporters that rely on the distance-dependent energy transfer between two fluorescent proteins. While mentioned as a technology for sensing various metabolites [31], detailed protocols and quantitative data specific to amino acid sensing were not identified in the available literature. The general principle involves a ligand-binding domain fused between a donor and an acceptor fluorescent protein. Upon binding the target amino acid, a conformational change alters the distance or orientation between the fluorophores, thereby changing the FRET efficiency, which can be measured as a ratio of acceptor-to-donor emission.

Diagram: Generic Workflow for a FRET-Based Biosensor Screen

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Implementing Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors [30] [31]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Regulator (TF) | The sensory component that binds the target metabolite. Can be wild-type or engineered. | SerR and its evolved mutant, SerRF104I. |

| Reporter Protein | A easily detectable protein whose expression is controlled by the TF. Used for quantification. | Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (eYFP). |

| Reporter Plasmid | A vector containing the TF-regulated promoter controlling the reporter gene. | Plasmid with Pser promoter driving eyfp expression. |

| Production Host Strain | The engineered microorganism used for amino acid production and screening. | Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032. |

| Key Enzyme Targets | Enzymes in the biosynthetic pathway that are engineered to enhance metabolic flux. | l-Homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom), γ-glutamyl kinase (ProB). |

| Directed Evolution Tools | Methods to create genetic diversity for engineering TFs or metabolic enzymes. | Error-prone PCR, site-saturation mutagenesis. |

| HTS Instrumentation | Equipment for rapidly assaying fluorescence output from thousands of clones. | Flow cytometer, fluorescence microplate reader. |

The pursuit of high-performance microbial cell factories for amino acid production is a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology. Conventional screening methods, particularly those using toxic amino acid analogs, face significant limitations including off-target cellular toxicity, the development of detoxification mechanisms in host strains, and a limited scope of available analogs for many amino acids [9] [19]. Translation-based screening emerges as a powerful alternative that directly links intracellular amino acid abundance with the expression of selectable or screenable markers. This method leverages the fundamental biological process of protein translation, specifically the phenomenon of codon usage bias—the non-uniform preference for certain synonymous codons over others in the genetic code of an organism [19].

The core principle of this technology rests on the differential charging of transfer RNA (tRNA) isoacceptors under varying intracellular amino acid concentrations. During amino acid starvation, the charging levels of rare tRNA isoacceptors approach zero, while common isoacceptors maintain higher charging levels for longer periods [19]. By engineering marker genes where common codons are replaced with their synonymous rare alternatives, researchers can create genetic elements whose translation becomes directly dependent on the intracellular concentration of the target amino acid. This approach enables the development of highly specific, high-throughput screening systems that accurately reflect the metabolic state of the cell, allowing for direct selection of amino acid overproducers from vast mutant libraries [9] [19] [32].

Theoretical Foundation and Mechanism

The Molecular Basis of Codon Usage Bias

Codon usage bias stems from the degeneracy of the genetic code, where 61 sense codons encode 20 standard amino acids [19]. Organisms exhibit distinct preferences for certain synonymous codons, categorizing them as "common" or "rare" based on their frequency of occurrence in the genome [19]. This bias has profound implications for translation efficiency and accuracy. The translation of rare codons depends on corresponding rare tRNAs, which are present in low abundances within the cellular tRNA pool [19]. During protein synthesis, the availability of charged tRNAs directly influences the rate of translation elongation, with rare codons often causing ribosomal stalling due to limited cognate tRNA availability [33].

The critical insight for screening applications is that rare tRNAs cannot be fully charged under conditions of amino acid starvation [19]. The charging of rare isoacceptors occurs only when intracellular amino acid concentrations are sufficient after charging the more abundant common isoacceptors [19] [32]. This creates a natural competition between common and rare tRNA isoacceptors for the available amino acid pool, establishing a molecular link between amino acid abundance and translational efficiency at rare codons.

From Principle to Practical Screening System

The translation-based screening strategy transforms this molecular principle into a practical tool by engineering reporter genes with modified codon compositions. When common codons in antibiotic resistance genes or fluorescent protein genes are systematically replaced with their synonymous rare alternatives, the expression of these markers becomes sensitive to intracellular amino acid levels [19] [3]. Under standard conditions, translation of these engineered markers is inefficient due to ribosomal stalling at rare codons. However, in amino acid overproducers, the elevated intracellular concentration of the target amino acid ensures sufficient charging of rare tRNAs, enabling efficient translation and consequent marker expression [19].

This approach creates a direct functional link between the metabolic phenotype (amino acid overproduction) and a easily selectable or screenable trait (antibiotic resistance or fluorescence). The system is inherently high-throughput and can be applied to various amino acids simply by modifying the codon replacement strategy, overcoming a significant limitation of analog-based methods [9] [19].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of translation-based screening requires carefully engineered genetic components and selection systems. The table below outlines essential research reagents and their specific functions in developing rare-codon-based screening platforms.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Rare-Codon-Based Screening

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Screening System |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Resistance Markers | Rare-codon-rich kanR (Kanamycin resistance) [19]; Rare-codon-rich specR (Spectinomycin resistance) [19] |

Selectable marker for amino acid overproducers; Cell growth under antibiotic selection indicates sufficient target amino acid production [19]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Rare-codon-rich gfp (Green Fluorescent Protein) [19]; StayGold fluorescent protein [3] |

Screenable marker for high-throughput sorting; Fluorescence intensity correlates with intracellular amino acid levels [19] [3]. |

| Chromogenic Reporters | PPG (PrancerPurple Protein) [19] | Visual screening of producer strains; Colony color intensity indicates amino acid production levels [19]. |

| Rare Codon-Rich Markers | kanR-RC29 (29 leucine codons replaced with rare CTA) [19]; LESG marker with all valine codons as rare GTC [3] |

Engineered genes with common codons replaced by rare synonyms; Translation efficiency becomes dependent on target amino acid supply [19] [3]. |

| Model Organisms | Escherichia coli [19] [3]; Corynebacterium glutamicum [19] | Industrial production hosts; Well-characterized genetics and codon usage tables enable rational design of rare-codon markers [19]. |

Quantitative Foundations: Codon Usage and Replacement Strategies

Effective implementation of rare-codon screening requires careful consideration of codon usage frequencies and replacement strategies. The table below presents quantitative data on rare codon usage in E. coli, a commonly used host for amino acid production.

Table 2: Rare Codon Usage Frequencies and Replacement Strategies in E. coli

| Amino Acid | Rare Codon | Frequency in E. coli Genome (%) | Replacement Strategy | Effect on Protein Expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucine | CTA | 0.39 [19] | Replace some or all of 29 leucine codons in kanR [19] |

Dose-dependent reduction; 29 replacements (kanR-RC29) caused 8.5-fold OD600 decrease vs. wild-type [19]. |

| Arginine | AGG | 0.11 [19] | Replace common arginine codons (e.g., CGT, CGC) in marker genes [19] | Significant inhibition of marker translation under arginine starvation; restored in overproducers [19]. |

| Serine | TCC | 0.86 [19] | Replace common serine codons in selection markers [19] | Reduced marker expression under standard conditions; selective advantage for serine overproducers [19]. |

| Valine | GTC | 23% of valine codons (in specific strains) [3] | Replace all valine codons in fluorescent marker StayGold [3] | Fluorescence intensity correlates with intracellular valine concentration; enables FACS sorting [3]. |

The data demonstrates that rare codon frequency directly influences protein expression levels in a dose-dependent manner. This relationship forms the quantitative foundation for tuning the stringency of selection systems. For example, in the case of leucine screening, replacing increasing numbers of leucine codons with the rare CTA codon resulted in progressively stronger inhibition of kanamycin resistance gene expression, with maximal effect observed when all 29 leucine codons were replaced [19].

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanism of Rare-Codon Screening. This diagram illustrates how intracellular amino acid (AA) levels control marker expression through tRNA charging and translation efficiency.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of Rare-Codon-Rich Markers

Purpose: To engineer antibiotic resistance or reporter genes with rare-codon substitutions for target amino acids.

Materials:

- Wild-type marker gene (e.g.,

kanR,gfp,ppg) - Codon usage table for host organism (e.g., EcoGene for E. coli)

- PCR-based gene synthesis reagents

- Cloning vector (e.g., pUC-57) [3]

- Restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, HindIII) [3]

- Competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α, TOP10) [19]

Procedure:

- Codon Usage Analysis: Identify the frequency of all codons for your target amino acid in the host organism using genomic databases. Select the rarest synonymous codon for replacement [19]. For example, in E. coli, CTA (0.39%) is the rarest leucine codon, AGG (0.11%) is the rarest arginine codon, and TCC (0.86%) is a rare serine codon [19].

Gene Design: Design a variant of your marker gene where common codons for the target amino acid are replaced with the selected rare synonymous codon. Replacement can be partial or complete, with more extensive replacement typically resulting in stronger translation inhibition [19]. For example, in developing a leucine biosensor, researchers created

kanRvariants with 6, 16, 26, or all 29 leucine codons replaced with CTA [19].Gene Synthesis: Synthesize the rare-codon-rich (RC) gene using PCR-based accurate synthesis or commercial gene synthesis services [19]. The resulting genes can be designated with RC notation (e.g.,

kanR-RC29for a kanamycin resistance gene with 29 leucine-to-CTA replacements) [19].Cloning and Verification: Clone the synthesized RC-gene into an appropriate plasmid vector using standard molecular biology techniques. Verify the sequence integrity through colony PCR and Sanger sequencing [3].

Protocol 2: Screening for Amino Acid Overproducers

Purpose: To identify amino acid overproducing strains from mutant libraries using rare-codon-rich markers.

Materials:

- Mutant library (e.g., generated by ARTP mutagenesis) [3]

- Selection media with appropriate antibiotics

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) for fluorescence-based screening [3]

- Microplate reader for fluorescence quantification [3]

- HPLC system for amino acid quantification [19]

Procedure:

- Library Transformation: Introduce the plasmid containing the rare-codon-rich marker into the mutant library cells by transformation [19].

Selection/Screening Conditions:

- Antibiotic Selection: Plate transformed cells on media containing the appropriate antibiotic at a predetermined concentration. For E. coli with rare-codon-rich

kanR, 0.2x LB medium provided significant differentiation between producers and non-producers [19]. - Fluorescence Screening: For fluorescence-based screening, induce marker expression (e.g., with 0.6 mM IPTG) and incubate under appropriate conditions (e.g., 25°C for 12 hours) [3]. Measure fluorescence using a microplate reader or sort cells using FACS [3].

- Antibiotic Selection: Plate transformed cells on media containing the appropriate antibiotic at a predetermined concentration. For E. coli with rare-codon-rich

Validation of Candidates:

Diagram 2: High-Throughput Screening Workflow. This flowchart outlines the complete process from library generation to validation of high-yielding strains.

Applications and Performance Data

Translation-based screening has been successfully applied to select overproducers of various amino acids in different microbial hosts. The table below summarizes documented applications and performance metrics.

Table 3: Documented Applications of Rare-Codon-Rich Marker Screening

| Amino Acid | Host Organism | Marker Type | Screening Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Leucine | E. coli | Kanamycin resistance with CTA codons | Successful selection of overproducers from random mutation libraries | [19] |

| L-Arginine | E. coli | Kanamycin resistance with AGG codons | Effective selection of arginine overproducers | [19] |

| L-Arginine | C. glutamicum | Antibiotic resistance with AGG (0.32% frequency) codons | Demonstration of cross-species application | [19] |

| L-Serine | E. coli | Antibiotic resistance with TCC codons | Selection of serine overproducing strains | [19] |

| L-Valine | E. coli DB-1-1 | Fluorescent marker (StayGold) with GTC codons | 59.5% sorting efficiency; 23.1% titer improvement; 84.1 g/L in 24h | [3] |

The data demonstrates the broad applicability of this approach across different amino acids and host organisms. Particularly noteworthy is the performance in L-valine screening, where the rare-codon-based system achieved a remarkable 59.5% sorting efficiency for high-producing strains, with the best mutant producing 84.1 g/L of L-valine in 24 hours—a 23.1% improvement over the wild-type strain [3]. This highlights the method's efficiency in identifying high-performing production strains.

Advantages Over Traditional Methods

Translation-based screening offers several distinct advantages compared to conventional analog-based selection: