Advanced Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Developing Microbial Cell Factories

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary metabolic engineering strategies for developing efficient microbial cell factories, targeting researchers and scientists in drug development and industrial biotechnology.

Advanced Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Developing Microbial Cell Factories

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary metabolic engineering strategies for developing efficient microbial cell factories, targeting researchers and scientists in drug development and industrial biotechnology. It explores foundational concepts, from host selection to pathway reconstruction, and delves into advanced methodological tools including CRISPR/Cas9, synthetic biology, and systems-level approaches. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as managing metabolic homeostasis and overcoming toxicity, and validates these strategies through comparative analysis of model and non-model organisms. By synthesizing recent advances and future directions, this review serves as a strategic guide for engineering robust microbial platforms for the sustainable production of high-value nutraceuticals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals.

Building the Foundation: Core Principles and Host Selection for Microbial Cell Factories

Defining Microbial Cell Factories and Their Role in Sustainable Biomanufacturing

Microbial Cell Factories (MCFs) are engineered microorganisms—typically bacteria or yeast—that function as biological platforms for the sustainable production of valuable substances [1]. At its core, an MCF is a living organism, meticulously reprogrammed through genetic and metabolic engineering to serve as a miniature production plant. These cellular systems convert simple, renewable input materials, such as sugars or agricultural waste, into specific, high-value output products through a series of enzymatic reactions [1]. This paradigm represents a significant shift from traditional, often polluting, chemical synthesis methods toward more sustainable, bio-based manufacturing [1].

The operational significance of MCFs is realized through the disciplines of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology, which focus on manipulating cellular networks to enhance the yield and specificity of target molecules [1]. In the contemporary bioeconomy era, MCFs are regarded as the fundamental "chips" of biomanufacturing, capable of producing a wide array of bioproducts including bioenergy, biochemicals, pharmaceuticals, food ingredients, and nutrients [2]. Their importance stems from their ability to perform complex biochemical transformations with remarkable precision under mild environmental conditions, thereby reducing energy consumption and generating fewer hazardous byproducts compared to conventional chemical processes [1].

Engineering Microbial Cell Factories: Core Principles and Strategies

The development of efficient MCFs requires a systematic, multi-layered approach that integrates knowledge from genomics, systems biology, and synthetic biology. This process involves a deep understanding of the host organism's metabolic network and the application of advanced genetic tools to redirect cellular resources toward the desired product.

Foundational Engineering Workflow

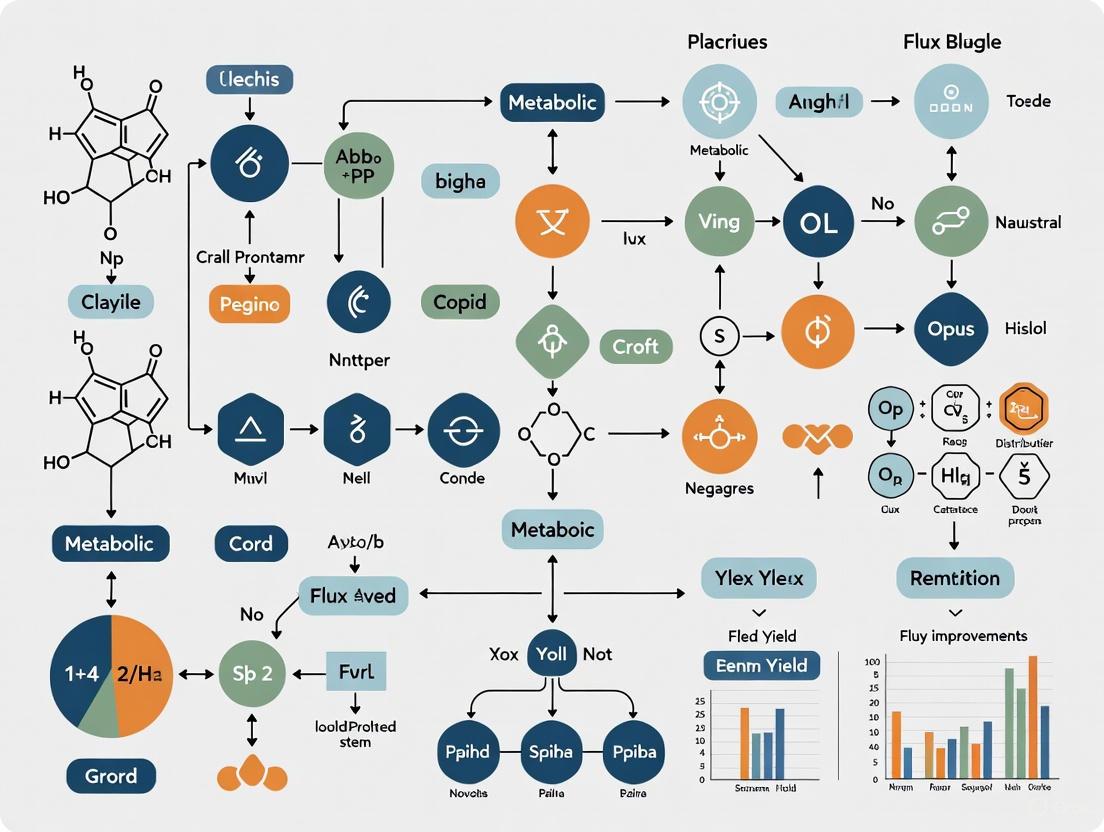

The process of transforming a native microorganism into an efficient cell factory follows a logical and iterative workflow, as illustrated below.

Metabolic Pathway Design and Optimization

The heart of MCF development lies in metabolic pathway engineering, which involves designing and optimizing the biochemical routes that convert carbon sources into target chemicals. The diagram below outlines the key considerations for this process.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The engineering of MCFs relies on a specialized toolkit of reagents and materials. The following table details key research reagent solutions essential for metabolic engineering experiments.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in MCF Development |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Enables precise genome editing for gene knockouts, insertions, and regulatory adjustments; considered the most promising tool for transformative advancements in genome editing due to its accuracy and adaptability [3]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Mathematical representations of metabolic networks used for in silico simulation of metabolic fluxes, prediction of optimal genetic modifications, and calculation of theoretical production yields [4] [5]. |

| Cloning Vectors & Expression Plasmids | DNA carriers for introducing heterologous genes into host microorganisms, enabling the expression of non-native enzymes and pathways for novel product synthesis [1]. |

| Specialized Culture Media | Formulated growth media providing optimized nutrient profiles, selective antibiotics, and specific inducers for gene expression to maintain and select for engineered strains [6]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., GC/MS, LC/MS) | Certified reference materials for accurate quantification of target chemicals, intermediates, and byproducts during fermentation for metabolic flux analysis [4]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Enzyme or chemical systems that regenerate essential cofactors (e.g., NADH, NADPH, ATP) to sustain the thermodynamic driving force of engineered biosynthetic pathways [4] [7]. |

Quantitative Analysis of Microbial Chassis Performance

Selecting an appropriate microbial host is a critical first step in developing an efficient MCF. Recent research has provided a comprehensive quantitative framework for evaluating and comparing the inherent metabolic capacities of different industrial microorganisms.

Systematic Host Selection Framework

A landmark 2025 study conducted by KAIST researchers performed a comprehensive in silico evaluation of five representative industrial microorganisms for the production of 235 bio-based chemicals [4] [5]. The study utilized Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) to calculate two key metrics for each chemical:

- Maximum Theoretical Yield (Yₜ): The maximum production of the target chemical per given carbon source when all cellular resources are fully allocated to production, ignoring requirements for growth and maintenance [4].

- Maximum Achievable Yield (Yₐ): A more realistic yield that accounts for non-growth-associated maintenance energy and sets a lower bound for specific growth rate, ensuring minimum growth requirements are met [4].

This systematic analysis involved constructing 1,360 GEMs, with 1,092 requiring the addition of heterologous reactions not native to the host strain [4]. Importantly, for over 80% of the target chemicals, fewer than five heterologous reactions were needed to establish functional biosynthetic pathways across the different hosts [4].

Comparative Performance of Industrial Microorganisms

The following table summarizes the metabolic capabilities of the five most frequently employed industrial microbial strains as identified in the comprehensive evaluation.

Table 2: Metabolic Capacities of Representative Industrial Microorganisms [4]

| Microbial Host | Key Characteristics | Exemplary Chemical Production (Yₐ on Glucose) | Preferred Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Fast growth, well-characterized genetics, extensive toolbox, simple cultivation [4] | L-Lysine: 0.7985 mol/mol [4] | Recombinant proteins, organic acids, biofuels, natural products [1] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), eukaryotic protein processing, robust in fermentation [4] | L-Lysine: 0.8571 mol/mol (highest) [4] | Ethanol, pharmaceuticals, complex natural products, vaccines [1] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | GRAS, natural secretion of amino acids, industrial workhorse [4] | L-Glutamate: Industrial producer [4]; L-Serine: Engineered strains [7] | Amino acids (L-glutamate, L-lysine), organic acids, diamines [4] |

| Bacillus subtilis | GRAS, efficient protein secretion, sporulation capability [4] | L-Lysine: 0.8214 mol/mol; Pimelic Acid: Host-specific superiority [4] | Industrial enzymes, antibiotics, vitamins [4] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Metabolic versatility, stress resistance, can use diverse carbon sources [4] | L-Lysine: 0.7680 mol/mol [4] | Bioremediation, aromatics, difficult-to-synthesize chemicals [4] |

Yield Optimization Through Pathway Engineering

The comprehensive evaluation also proposed and quantified strategies to surpass the innate metabolic capacities of microorganisms. By introducing heterologous enzyme reactions from other organisms and engineering cofactor usage, researchers demonstrated yield improvements for various industrially important chemicals [5]. The study quantitatively identified relationships between specific enzyme reactions and target chemical production, determining which enzymatic steps should be up-regulated or down-regulated to maximize production capacity [4] [5].

For instance, in the case of L-serine production, metabolic engineering strategies in both E. coli and C. glutamicum have included:

- Augmenting precursor supply (3-phosphoglycerate)

- Repressing competitive metabolic pathways that divert intermediates

- Implementing transporter engineering to facilitate product secretion and reduce feedback inhibition

- Applying cofactor engineering to balance redox cofactors (NADH/NAD⁺) [7]

Experimental Protocols in Metabolic Engineering

The development of robust MCFs relies on standardized yet advanced experimental methodologies. Below are detailed protocols for key processes in the metabolic engineering workflow.

Protocol for Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEM) Analysis

Purpose: To computationally predict metabolic capabilities and identify engineering targets for improved chemical production [4] [5].

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of target microorganism (e.g., from BiGG Models database)

- Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) toolbox

- Biochemical data for mass and charge-balanced reaction equations (e.g., Rhea database)

- Carbon source uptake constraints (e.g., glucose: 10 mmol/gDW/h)

Methodology:

- Model Curation: Reconstruct metabolic network based on genome annotation, ensuring mass and charge balance for all reactions [4].

- Pathway Incorporation: Incorporate biosynthetic pathway for target chemical using known metabolic reactions, adding heterologous reactions if not present in the native model [4].

- Constraint Definition: Set constraints to reflect cultivation conditions:

- Carbon source uptake rate

- Oxygen uptake (aerobic: ~15-20 mmol/gDW/h; anaerobic: 0 mmol/gDW/h)

- ATP maintenance requirements (NGAM) [4]

- Yield Calculation:

- Yₜ (Theoretical Yield): Perform flux balance analysis with biomass formation set to zero.

- Yₐ (Achievable Yield): Set lower bound of biomass formation to 10% of maximum and include NGAM constraint [4].

- Intervention Simulation: Identify gene knockout or up/down-regulation targets using optimization algorithms (e.g, OptKnock) to couple target chemical production with growth [4].

Protocol for CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing

Purpose: To implement precise genetic modifications in microbial hosts for metabolic pathway engineering [3].

Materials:

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid system (expressing Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA)

- Donor DNA template for homologous recombination (if needed)

- Electrocompetent or chemically competent cells of target microorganism

- Appropriate selection media (antibiotics, indicator media)

- Gel electrophoresis equipment for verification

Methodology:

- gRNA Design: Design 20-nucleotide guide RNA sequence complementary to target genomic locus with PAM (NGG) sequence immediately downstream [3].

- Vector Construction: Clone gRNA expression cassette into CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and transform into engineering host.

- Transformation: Introduce plasmid and donor DNA (if needed) into competent cells via electroporation or chemical transformation.

- Selection and Screening: Plate transformed cells on selective media and incubate. Screen individual colonies for desired mutation via colony PCR or sequencing.

- Plasmid Curing: Remove CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid through serial passage in non-selective media or using temperature-sensitive replicons [3].

- Validation: Confirm genotype and phenotype through sequencing, PCR, and product quantification.

Critical Considerations:

- Off-target effects: Optimize gRNA design using computational tools to minimize off-target cleavage [3].

- Editing efficiency: Optimize Cas9 codon usage, promoter strength, and donor DNA design for specific host [3].

- Host compatibility: Adapt protocol for non-model organisms that may lack efficient genetic tools [3].

Microbial Cell Factories represent a transformative technological paradigm for sustainable biomanufacturing in the bioeconomy era. The field is rapidly evolving from the engineering of single pathways toward the holistic design of complex cellular systems. Future advancements will be increasingly driven by the integration of automation and artificial intelligence with biotechnology to facilitate the development of customized artificial synthetic MCFs [2]. The emerging trends of continuous fermentation processes, AI-powered bioprocess optimization, and closed-loop systems promise to further enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impact [8].

However, significant challenges remain in translating laboratory successes to industrial-scale production. The inherent conflict between host fitness and synthetic pathway performance represents a fundamental biological constraint that requires sophisticated balancing [1]. Additionally, evolutionary instability in engineered strains and the complexities of downstream processing present substantial hurdles for commercial implementation [1]. Future research must focus on developing integrated frameworks that combine systems-level understanding of microbial physiology with advanced engineering principles to create robust, high-performing MCFs that can reliably meet the growing demand for sustainable chemicals and materials.

The ongoing technological convergence of synthetic biology, systems biology, and AI promises to accelerate the development of next-generation MCFs, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable circular bioeconomy through the replacement of petroleum-based processes with biological alternatives.

The development of efficient microbial cell factories (MCFs) is a cornerstone of industrial biotechnology, enabling the sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and biochemicals. A critical initial decision in this process is the selection of an appropriate microbial host, a choice that fundamentally shapes all subsequent metabolic engineering strategies. For decades, model organisms such as Escherichia coli (bacteria) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) have dominated the landscape due to their well-characterized genetics and extensive toolkits. However, non-model yeasts, particularly Yarrowia lipolytica, are increasingly demonstrating superior capabilities for specific applications, challenging the hegemony of traditional workhorses. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of these host organisms, framing the selection criteria within the context of systems metabolic engineering. It synthesizes contemporary research data and experimental protocols to guide researchers and scientists in making informed, strategic decisions for MCF development.

Systems metabolic engineering integrates tools from synthetic biology, systems biology, and evolutionary engineering to optimize microbial hosts for chemical production [4]. The selection of a chassis organism is a multifaceted decision that extends beyond the mere presence of a biosynthetic pathway. It requires a holistic consideration of the host's innate metabolic capacity, genetic stability, safety, and resilience to process conditions and product toxicity [4] [9].

Model microorganisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae have been the primary workhorses due to the abundance of available knowledge on their genetic and metabolic characteristics, as well as highly developed gene manipulation tools [4] [10]. E. coli, a prokaryotic model, offers rapid growth and high-density cultivation. S. cerevisiae, a eukaryotic model, provides the advantages of a GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) status, robustness in industrial fermentations, and the ability to perform complex eukaryotic post-translational modifications [10].

In contrast, non-model yeasts like Y. lipolytica are "rising stars" in industrial biotechnology. This Crabtree-negative, oleaginous yeast is recognized for its innate ability to utilize a wide range of low-cost substrates, including hydrocarbons and industrial waste streams, and its high flux through acetyl-CoA and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, making it an exceptional host for the production of organic acids, lipids, and other acetyl-CoA-derived compounds [11] [12]. The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison to elucidate the strategic fit of each host.

Comparative Analysis of Host Organisms

The metabolic capabilities and industrial suitability of a host can be quantitatively and qualitatively evaluated against several key criteria. The table below summarizes a systematic comparison of E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and Y. lipolytica.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microbial Chassis Organisms

| Feature | Escherichia coli (Model Bacterium) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Model Yeast) | Yarrowia lipolytica (Non-Model Yeast) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic & Metabolic Background | Prokaryote; extensively characterized; minimal genetic tools available [4] [13]. | Eukaryote; most thoroughly investigated eukaryote; complete genome sequenced [10]. | Eukaryote; genetics less developed than model systems but tools rapidly advancing [14] [12]. |

| Safety & Regulation | Can harbor toxins; not always suitable for pharmaceutical products [10]. | GRAS (Generally Regarded as Safe) status [10]. | GRAS (Generally Regarded as Safe) status [11] [12]. |

| Metabolic Strengths | Simple metabolism; rapid growth; high achievable yields on simple sugars [4] [13]. | High glycolytic flux; robust in industrial fermentations; natural ethanologen [10]. | High TCA flux; oleaginous (lipid-accumulating); efficient NADH regeneration; metabolizes diverse substrates (e.g., glycerol, alkanes) [11] [12]. |

| Substrate Range | Primarily simple sugars (glucose, xylose) [4] [13]. | Simple sugars (glucose, sucrose); some strains engineered for xylose [10]. | Broad range: glucose, glycerol, organic acids, hydrocarbons; thrives on food waste hydrolysate [11]. |

| Product Secretion | Efficient for some organic acids and proteins; can require engineering for export [9]. | Naturally secretes ethanol; can be engineered for protein and organic acid secretion [10] [9]. | Naturally secretes organic acids (e.g., citric, succinic); demonstrated secretion of crocetin, an apocarotenoid [12]. |

| Tolerance to Stress | Variable tolerance to organic acids and solvents; can be improved via engineering [9] [13]. | High tolerance to acidic conditions and ethanol; suitable for organic acid production [11]. | High tolerance to acidic pH and organic acids; naturally robust in harsh environments [11]. |

| Theoretical Yield (Example) | High yield for products from glycolytic precursors (e.g., 5-HTP at 0.095 g/g glucose) [13]. | High theoretical yield for lysine (0.8571 mol/mol glucose under aerobic conditions) [4]. | High yield for acetyl-CoA-derived products (e.g., lipids, carotenoids, D-lactic acid) [11] [12]. |

| Key Applications | Amino acid derivatives (5-HTP) [13], biofuels, recombinant proteins [9]. | Ethanol, lactic acid [10], recombinant proteins, pharmaceuticals [10] [9]. | Lipids, omega-3 fatty acids, organic acids (D-LA) [11], carotenoids (β-carotene, crocetin) [12], polymers. |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Theoretical and achievable yields are central to assessing a host's metabolic capacity. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational tools for this purpose, enabling the prediction of maximum theoretical yield (Y~T~) and maximum achievable yield (Y~A~), which accounts for cellular maintenance and growth [4].

Table 2: Representative Production Metrics in Engineered Strains

| Product | Host | Titer | Yield | Productivity | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) | E. coli K-12 [13] | 8.58 g/L | 0.095 g/g glucose | 0.48 g/L/h | Systematic modular engineering; heterologous TPH2 pathway; NADPH regeneration. |

| D-Lactic Acid (D-LA) | Y. lipolytica Po1d [11] | ~1.8 g/L (shake flask) | N/R | N/R | Heterologous expression of ldhA from K. pneumoniae; ACS2 overexpression. |

| Crocetin | Y. lipolytica YB392 [12] | 30.17 mg/L (shake flask) | N/R | N/R | Pathway engineering with hybrid promoters; two-step temperature-shift fermentation. |

| L-Lysine | S. cerevisiae [4] | N/A | 0.8571 mol/mol glucose (Y~T~) | N/A | Innate L-2-aminoadipate pathway shows highest theoretical yield among 5 hosts analyzed. |

| Zeaxanthin | Y. lipolytica [12] | 1575.09 mg/L | N/R | N/R | Engineered β-carotene strain precursor; pathway optimization. |

N/R: Not Reported in the sourced context; N/A: Not Applicable.

Experimental Protocols for Host Engineering

The genetic toolkits and engineering methodologies vary significantly between model and non-model organisms. Below are detailed protocols for key genetic manipulations cited in recent literature.

High-Throughput Promoter Replacement inYarrowia lipolytica(TUNEYALI Method)

The TUNEYALI (TUNing Expression in Yarrowia lipolytica) method is a CRISPR-Cas9-based system for high-throughput, scarless promoter replacement, enabling precise tuning of gene expression levels [14].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Design and Synthesis: Design a synthetic DNA construct containing:

- A target-specific sgRNA sequence targeting the promoter region of the gene of interest.

- Upstream Homology Arm (62 bp or 162 bp): Matches the genomic sequence immediately upstream of the native promoter.

- Downstream Homology Arm (62 bp or 162 bp): Matches the start of the coding sequence (CDS) of the target gene.

- A double SapI restriction site between the homology arms, which generates an ATG overhang for scarless assembly.

- This ~300-500 bp synthetic construct is cloned into a plasmid backbone via Gibson assembly [14].

- Promoter Library Assembly: A library of native Y. lipolytica promoters of varying strengths is inserted into the plasmid between the homology arms using a Golden Gate assembly reaction with SapI enzyme. The reaction mix includes DNA parts, T4 ligase buffer, T7 ligase, BsmBI/BsaI, and nuclease-free water. The thermal profile is 90 cycles of (37°C for 2 min + 16°C for 5 min), followed by 60°C for 10 min and 80°C for 10 min [14].

- Transformation and Editing: The resulting plasmid library is transformed into Y. lipolytica using a chemical transformation protocol with 100 μL volume containing 1.5 pmol of NotI-digested plasmid and 85 μL of 50% PEG 4000. The sgRNA directs Cas9 to create a double-strand break in the native promoter. The linear repair template within the plasmid, flanked by homology arms, replaces the native promoter via homologous recombination [14].

- Screening and Validation: Successfully edited clones are screened for the desired phenotypic change (e.g., altered fluorescence, production titers). Genomic DNA is extracted from selected clones, and the edited locus is PCR-amplified and sequenced to confirm the correct promoter swap [14].

Systematic Modular Engineering inEscherichia colifor 5-HTP Production

This protocol outlines the systematic modular approach used to engineer E. coli for high-level 5-HTP production, demonstrating the power of modular pathway optimization in a model bacterium [13].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Chassis Strain Development:

- Integrate a P~xylF~-driven T7 RNA polymerase gene into the lacIZ locus of E. coli K-12 w3110 for strong, xylose-inducible expression.

- Delete the tnaA gene to prevent degradation of the precursor L-Trp and the product 5-HTP.

- Mutate the promoter region of the mlc gene to alleviate carbon catabolite repression, ensuring efficient glucose utilization [13].

- Tryptophan Hydroxylation Module Construction:

- Introduce a heterologous tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) synthesis pathway. Key genes include mtrA (GTP cyclohydrolase I, GCHI), PTPS (6-pyruvate-tetrahydropterin synthase), and SPR (sepiapterin reductase).

- Co-express the BH4 regeneration pathway to maintain cofactor homeostasis.

- Express a mutant of human tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) with high heterologous activity in E. coli to catalyze the conversion of L-Trp to 5-HTP [13].

- L-Tryptophan Synthesis Module Enhancement:

- Engineer the native L-Trp biosynthesis pathway to enrich the precursor pool. This involves modifying key metabolic nodes, such as upregulating rate-limiting enzymes and deleting competing pathways, to channel carbon flux towards L-Trp [13].

- NAD(P)H Regeneration Module Integration:

- To address redox imbalances and reduce L-Trp byproduct accumulation, introduce a heterologous cofactor regeneration system. This is achieved by moderately expressing a glucose dehydrogenase (GDH~esi~) from Exiguobacterium sibiricum, which consumes glucose to regenerate NAD(P)H from NAD(P)^+^ [13].

- Fermentation and Analysis:

- Cultivate the final engineered strain (e.g., HTP11) in a bioreactor with controlled feeding of glucose.

- Monitor cell density, substrate consumption, and product formation. Quantify 5-HTP and L-Trp (byproduct) titers using analytical methods like HPLC [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section catalogues key reagents, genetic tools, and systems used in the metabolic engineering of the discussed hosts, as derived from the featured experiments and literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / System | Function | Example Host | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Targeted genome editing; gene knockout, insertion, and regulation. | Y. lipolytica, S. cerevisiae, E. coli | TUNEYALI method for promoter swapping in Y. lipolytica [14]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly | Modular, hierarchical DNA assembly standard using Type IIs restriction enzymes. | Y. lipolytica | Used in YaliCraft toolkit for plasmid and pathway construction [12]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic flux, theoretical yields (Y~T~, Y~A~), and gene knockout targets. | All hosts | Used to calculate metabolic capacities of 5 hosts for 235 chemicals [4]. |

| Xylose-Inducible T7 System | Tight, high-level gene expression system. | E. coli | Provides controlled, strong expression for heterologous pathways (e.g., 5-HTP production) [13]. |

| Hybrid Promoters | Synthetic promoters created by fusing elements of different native promoters to fine-tune strength. | Y. lipolytica | Employed to optimize gene expression in the β-carotene and crocetin pathways [12]. |

| Heterologous Dehydrogenases (e.g., LdhA, GDH) | Introduces novel catalytic activity or enhances cofactor regeneration. | Y. lipolytica, E. coli | ldhA from K. pneumoniae for D-LA production [11]; GDH~esi~ for NADPH regeneration in E. coli [13]. |

| Two-Step Temperature Shift | Fermentation strategy to decouple growth phase (optimal temp) from production phase (enzyme-optimal temp). | Y. lipolytica | Used to improve crocetin production by accommodating enzyme activity at lower temperatures [12]. |

The paradigm for selecting microbial chassis for cell factory development is evolving. While model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae remain powerful and versatile platforms with unparalleled genetic toolkits, non-model yeasts like Yarrowia lipolytica offer compelling and often superior advantages for specific product classes and process conditions. The choice is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment.

E. coli excels in speed and yield for many pathway-specific, non-toxic products derived from central carbon metabolism. S. cerevisiae is unmatched for its industrial robustness and safety in food and pharmaceutical applications. Y. lipolytica demonstrates clear dominance in the realm of lipogenesis, organic acid production, and the valorization of complex, low-cost waste streams, thanks to its unique metabolic architecture.

The future of host selection lies in the continued development of systems biology tools—such as more accurate GEMs and multi-omics integration—and sophisticated high-throughput engineering methods, like TUNEYALI, that bring the genetic tractability of non-model hosts to par with traditional models. This will enable a more rational, design-driven approach to not only select the best host but also to engineer it with maximum efficiency, ultimately accelerating the development of sustainable bioprocesses for a bio-based economy.

Acetyl-CoA stands as a fundamental metabolic hub in microbial central carbon metabolism, serving as a critical precursor for a vast array of value-added chemicals. This whitepaper delineates strategic approaches for leveraging native microbial metabolism to amplify acetyl-CoA flux, thereby enhancing the production capabilities of engineered cell factories. Within the broader context of metabolic engineering for microbial cell factory development, we present quantitative analyses of acetyl-CoA generation routes from various carbon sources, detailed experimental methodologies for pathway optimization, and advanced engineering paradigms that integrate systems and synthetic biology. The methodologies and data frameworks provided herein serve as an essential technical reference for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of efficient microbial production platforms for chemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals.

The Strategic Importance of Acetyl-CoA in Biomanufacturing

Acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) is a fundamental metabolite in central metabolic pathways for all living organisms, functioning as a critical hub that interconnects the catabolism and anabolism of major nutrients including sugars, fats, and proteins [15]. As the primary donor of the acetyl group, it provides the essential C2 building block for the biosynthesis of numerous industrial chemicals and natural compounds [16]. This multifaceted molecule is involved in various biological processes and serves as a platform chemical for producing diverse high-value products such as isoprenoids (used as flavors, biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and vitamins), 1-butanol, 3-hydroxypropionate, and polyhydroxyalkanoates [17].

The strategic manipulation of intracellular acetyl-CoA pools represents a central focus in metabolic engineering to enhance the production of acetyl-CoA-derived chemicals [17]. Microbial cell factories can synthesize acetyl-CoA from multiple carbon sources, including glucose, acetate, and fatty acids, each offering distinct advantages in terms of carbon conversion efficiency and theoretical yield [17]. The innate metabolism of certain microorganisms, particularly oleaginous yeasts like Yarrowia lipolytica, is characterized by a naturally high flux toward acetyl-CoA, making them ideal chassis organisms for synthesizing complex molecules like carotenoids, flavonoids, and specialty lipids [18] [19]. The engineering of these native pathways to optimize acetyl-CoA availability represents a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology, enabling the sustainable production of valuable compounds from renewable resources instead of fossil fuels [20] [16].

Microbial cell factories can generate acetyl-CoA through various metabolic routes, each with distinct carbon conversion efficiencies and theoretical yields. A comprehensive understanding of these pathways enables strategic selection of carbon sources and host organisms for specific bioproduction goals.

Table 1: Comparison of Acetyl-CoA Production Routes from Different Carbon Sources

| Carbon Source | Pathway | Key Enzymes | Theoretical Carbon Recovery | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Glycolysis → Pyruvate Decarboxylation | Pyruvate dehydrogenase, Pyruvate-formate lyase | 66.7% [17] | Efficient but involves carbon loss as CO₂ [17] |

| Acetate | ACS Pathway | Acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) | 100% [17] | High affinity for acetate (Km ~200 μM) but consumes more ATP [17] |

| Acetate | ACK-PTA Pathway | Acetate kinase (ACK), Phosphate acetyltransferase (PTA) | 100% [17] | Functions at high acetate concentrations (Km 7-10 mM) [17] |

| Fatty Acids | β-oxidation | Acyl-CoA oxidases, Bifunctional enzyme, Thiolase | 100% [17] | Generates abundant NADH and FADH₂ alongside acetyl-CoA [17] |

| One-Carbon Compounds | Synthetic Acetyl-CoA (SACA) Pathway | Glycolaldehyde synthase (GALS), Acetyl-phosphate synthase (ACPS) | ~50% demonstrated yield [15] | ATP-independent, carbon-conserving, oxygen-insensitive [15] |

Table 2: Performance of Engineered Microbial Hosts for Acetyl-CoA-Derived Chemical Production

| Host Organism | Target Product | Engineering Strategy | Production Performance | Key Metabolic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | N-Acetylglutamate (NAG) | ∆argB, ∆argA, ∆ptsG::glk, ∆galR::zglf, ∆poxB::acs, ∆ldhA, ∆pta with Ks-NAGS overexpression [17] | 98.2% glutamate conversion, 6.25 mmol/L/h productivity [17] | Optimized glucose utilization and acetyl-CoA supply [17] |

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Terpenoids, Flavonoids, Sphingolipids | Enhanced lipolysis, β-oxidation overexpression, PDC regulation, heterologous ACL expression [18] [19] | High acetyl-CoA flux innate capability [18] [19] | Natural high acetyl-CoA capacity, GRAS status, peroxisome compartmentalization [18] |

| Escherichia coli | Acetyl-CoA from One-Carbon | Synthetic Acetyl-CoA (SACA) pathway with engineered GALS and phosphoketolase [15] | Carbon yield ~50% in vitro [15] | Shortest, ATP-independent pathway from formaldehyde [15] |

The data reveal critical trade-offs in carbon source selection. While glucose is efficiently utilized through glycolysis, it incurs carbon loss during pyruvate decarboxylation, limiting theoretical carbon recovery to 66.7% [17]. In contrast, acetate and fatty acids offer 100% theoretical carbon recovery, making them attractive alternatives despite potential challenges in cellular uptake and regulation [17]. The metabolic capacity of host strains varies significantly, with systematic evaluations of five major industrial microorganisms (Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) revealing chemical-specific host superiority that doesn't always follow conventional biosynthetic pathway categorizations [4].

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Acetyl-CoA Supply

Engineering Acetyl-CoA Supply from Glucose in E. coli

Objective: To rewire central carbon metabolism in E. coli for enhanced acetyl-CoA generation from glucose while minimizing byproduct formation.

Methodology:

- Modify Glucose Uptake System: Replace the native phosphotransferase system (PTS) with a more efficient uptake mechanism by:

- Deleting ptsG and galR genes

- Integrating glk (glucokinase) and zglf (galactose:H+ symporter from Zymomonas mobilis) into the chromosome [17]

Block Pyruvate Bypass Pathways: Increase pyruvate availability for acetyl-CoA conversion by:

- Replacing pyruvate oxidase gene (poxB) with acetyl-CoA synthetase gene (acs)

- Inactivating lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhA) to prevent lactate formation [17]

Eliminate Acetyl-CoA Competing Pathways: Direct acetyl-CoA toward target products by:

- Inactivating phosphate acetyltransferase (pta) to reduce acetate formation

- Modifying citrate synthase (gltA) to control TCA cycle drain [17]

Validation: Measure acetyl-CoA pool size and N-acetylglutamate production (when coupled with NAGS overexpression) after 8 hours of whole-cell bioconversion with 50 mM sodium glutamate and 50 mM glucose [17].

Engineering Acetyl-CoA Supply from Fatty Acids

Objective: To enhance acetyl-CoA generation from fatty acids via the β-oxidation pathway.

Methodology:

- Deregulate Fatty Acid Uptake: Overcome transcriptional repression by:

- Deleting fadR global regulator [17]

Enhance Fatty Acid Activation: Increase fatty acid conversion to acyl-CoA by:

- Constitutively expressing fadD under a strong promoter (e.g., CPA1) [17]

Amplify β-oxidation Capacity: Enhance peroxisomal fatty acid degradation by:

Validation: Quantify acetyl-CoA production using palmitic acid as carbon source and measure molar conversion rate of glutamate to N-acetylglutamate (>80% conversion demonstrates effective acetyl-CoA supply) [17].

Implementing the Synthetic Acetyl-CoA (SACA) Pathway

Objective: Construct an efficient, artificial pathway for acetyl-CoA biosynthesis from one-carbon sources.

Methodology:

- Enzyme Engineering for C1 Condensation:

- Screen ThDP-dependent enzymes for formaldehyde condensation activity using molecular docking focused on C2 atom to glycolaldehyde distance [15]

- Perform iterative combinatorial mutagenesis (e.g., 64,512 clones screened) around the active center [15]

- Develop high-throughput screening using color reaction between glycolaldehyde and diphenylamine (measured at 650 nm) [15]

Pathway Assembly:

Validation:

Pathway Engineering and Visualization

The metabolic engineering of acetyl-CoA supply routes requires a systems-level understanding of native pathways and their synthetic alternatives. The following diagram illustrates key natural and engineered routes for acetyl-CoA biosynthesis in microbial cell factories.

Diagram 1: Natural and Engineered Pathways for Acetyl-CoA Biosynthesis. This workflow illustrates key metabolic routes for acetyl-CoA production from different carbon sources. Yellow nodes represent carbon inputs, green nodes indicate metabolic intermediates, blue nodes show natural enzymatic pathways, red nodes highlight engineered components, and the final red product node signifies acetyl-CoA. The synthetic SACA pathway (red connections) demonstrates a novel, efficient route from one-carbon compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Acetyl-CoA Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Engineering Tools | Engineered Glycolaldehyde Synthase (GALS) [15] | Condenses formaldehyde to glycolaldehyde in SACA pathway | 70-fold improved catalytic efficiency over wild-type [15] |

| Pathway Enzymes | Acetyl-CoA Synthetase (ACS) [17] | Converts acetate to acetyl-CoA | High affinity for acetate (Km ~200 μM) [17] |

| Pathway Enzymes | Acetate Kinase (ACK) / Phosphate Acetyltransferase (PTA) [17] | Converts acetate to acetyl-CoA via acetyl-phosphate | More ATP-efficient than ACS pathway [17] |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems [18] | Precise gene editing for pathway optimization | Enables targeted gene knockouts and integrations [18] |

| Analytical & Screening Tools | (^{13})C-labeled metabolites [15] | Pathway flux validation and confirmation | Verifies carbon fate through engineered pathways [15] |

| Analytical & Screening Tools | Transcription factor-based biosensors [18] | Detect intracellular acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA | Enables high-throughput screening of engineered strains [18] |

| Host Engineering Tools | Peroxisomal targeting signals [18] | Compartmentalization of metabolic pathways | Increases substrate channeling and reduces cytotoxicity [18] |

Advanced Engineering Paradigms: Systems and Synthetic Biology Approaches

The third wave of metabolic engineering integrates sophisticated systems and synthetic biology approaches to overcome the limitations of traditional pathway engineering. These advanced paradigms enable more predictable and efficient rewiring of cellular metabolism for enhanced acetyl-CoA supply and utilization.

Systems Biology and Multi-Omics Integration

Systems biology approaches utilize comprehensive multi-omics analyses to identify non-intuitive engineering targets that would be difficult to discover through conventional methods. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) integrated with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data provide unprecedented insights into cellular behavior and bottlenecks [18]. For example, GEMs have been employed to calculate maximum theoretical yields (YT) and maximum achievable yields (YA) for 235 different bio-based chemicals across five representative industrial microorganisms, enabling data-driven host selection for specific target compounds [4]. These models account for non-growth-associated maintenance energy and minimum growth requirements, providing more realistic yield predictions than stoichiometric calculations alone [4].

In Yarrowia lipolytica, systems biology approaches have proven highly effective for enhancing production of acetyl-CoA-derived compounds. Comparative transcriptomics has revealed key competing pathways in terpenoid production, enabling targeted gene deletions that significantly boost precursor flux [18]. Similarly, for bioactive lipids, multi-omics analysis has identified critical links between amino acid catabolism and product formation that inform engineering strategies [18]. The application of flux scanning based on enforced objective flux has successfully identified overexpression targets for enhancing lycopene production, demonstrating the power of these computational approaches for predicting genetic modifications that optimize metabolic flux [20].

Synthetic Biology and Compartmentalization Strategies

Synthetic biology provides a powerful toolbox that elevates the predictability and efficiency of metabolic engineering beyond traditional methods. In Yarrowia lipolytica, two prominent synthetic biology strategies have been successfully implemented for enhancing acetyl-CoA-derived compound production: subcellular compartmentalization and biosensor-driven dynamic control [18].

The complex cellular organelle structure of Y. lipolytica, including peroxisomes and lipid droplets, offers unique opportunities for metabolic compartmentalization [18]. This strategy involves targeting biosynthetic pathways to specific organelles to increase substrate and enzyme concentration, isolate metabolic intermediates, and alleviate cytotoxicity. The highly developed peroxisomal system has been particularly exploited for this purpose [18]. Engineering peroxisomal import mechanisms through peroxisomal targeting signal modifications has enabled successful compartmentalization of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways, resulting in improved yields [18]. Similarly, mitochondrial engineering has shown great potential, with targeting of the mevalonate pathway to mitochondria demonstrating enhanced precursor availability while maintaining cellular energy homeostasis [18].

The implementation of biosensors enables not only high-throughput screening for rapid selection of high-efficiency strains but also dynamic real-time control of metabolic pathways [18]. Transcription factor-based biosensors that respond to key metabolites such as acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, and farnesyl diphosphate have been successfully developed and integrated into feedback control circuits that automatically regulate gene expression in response to intracellular metabolite concentrations [18]. These advanced synthetic biology tools represent the cutting edge of metabolic engineering for optimizing acetyl-CoA flux and downstream product formation in microbial cell factories.

The strategic engineering of acetyl-CoA metabolism represents a cornerstone in the development of efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction. Through quantitative analysis of different carbon source utilization, implementation of targeted genetic modifications, and application of advanced systems and synthetic biology approaches, researchers can significantly enhance acetyl-CoA supply for diverse biotechnological applications. The experimental protocols and engineering frameworks presented in this technical guide provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for optimizing this central metabolic node across various microbial platforms. As metabolic engineering continues to evolve through the integration of sophisticated computational tools and synthetic biology approaches, the precise control of acetyl-CoA flux will remain essential for achieving industrial-scale production of valuable acetyl-CoA-derived chemicals, driving the transition toward a more sustainable bio-based economy.

The development of microbial cell factories (MCFs) represents a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology, enabling the sustainable production of chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources. Pathway reconstruction refers to the process of designing, introducing, and optimizing biological pathways in a host organism to enable the production of target compounds. Within this domain, heterologous pathway reconstruction specifically involves transferring and implementing biosynthetic routes from a donor organism into a microbial host that lacks these pathways naturally. This approach has emerged as a powerful strategy to expand the metabolic capabilities of industrial workhorses like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, allowing them to produce valuable compounds that would otherwise be inaccessible through their native metabolism [21] [22].

The strategic importance of heterologous pathways lies in their ability to overcome inherent limitations of native metabolism. While some microorganisms naturally produce desired chemicals, they often suffer from poor growth characteristics, limited genetic tools, or suboptimal productivity. Heterologous reconstruction allows researchers to combine advantageous physiological traits of well-characterized platform hosts with specialized metabolic capabilities from diverse biological sources. This integration is fundamental to systems metabolic engineering, which combines traditional metabolic engineering with synthetic biology, systems biology, and evolutionary engineering to develop efficient microbial cell factories [21]. The field has evolved from simple single-gene transfers to the reconstruction of complex, multi-enzyme pathways, with recent advances enabling the creation of completely synthetic pathways that do not exist in nature [21].

Fundamental Principles and Strategic Framework

Classification of Biosynthetic Pathways

Biosynthetic pathways in engineered microorganisms can be systematically categorized into three distinct types based on their origin and relationship to the host organism [21]:

Native-existing pathways: These are inherent to the host organism and can be optimized through metabolic engineering without introducing foreign genetic material. Examples include Corynebacterium glutamicum naturally producing L-glutamate and L-lysine, or Bacillus and Lactobacillus species producing L-lactate [21].

Nonnative-existing pathways: These pathways exist in other organisms in nature but are reconstructed in a non-native host through heterologous expression. The adipic acid biosynthesis pathway from Thermobifida fusca expressed in E. coli exemplifies this category [21].

Nonnative-created pathways: These are completely synthetic pathways designed de novo using enzymes with novel functions or created through computational design, representing pathways that do not exist in nature [21].

Core Principles of Heterologous Pathway Design

Successful implementation of heterologous biosynthetic routes relies on several fundamental principles that guide the reconstruction process:

Host Compatibility and Metabolic Integration: The introduced pathway must functionally integrate with the host's existing metabolic network. This requires consideration of cofactor compatibility, energy balance, precursor availability, and potential metabolic conflicts. The choice of host organism is critical and depends on factors such as the nature of the target compound, precursor availability, tolerance to pathway intermediates and products, and availability of genetic tools [21] [22].

Functional Expression of Heterologous Enzymes: Heterologous enzymes must be properly expressed, folded, and localized within the host cell. This often requires codon optimization, selection of appropriate promoters and ribosomal binding sites, and consideration of post-translational modifications that may differ between the source and host organisms [22].

Metabolic Flux Optimization: Simply expressing pathway enzymes is insufficient for efficient production. The metabolic flux through the heterologous pathway must be optimized while minimizing diversion of carbon to competing pathways. This often involves down-regulating native competing reactions and fine-tuning the expression levels of heterologous enzymes to avoid intermediate accumulation or enzyme saturation [21].

Toxicity and Regulatory Management: Heterologous pathways may produce intermediates or end products that are toxic to the host cell, or they may trigger native regulatory responses that limit production. Successful implementation requires strategies to manage these issues, such as inducible expression systems, transporter engineering, or evolution of resistant hosts [21].

Computational Design and Pathway Databases

The design of heterologous pathways increasingly relies on computational tools and databases that facilitate the identification and optimization of biosynthetic routes.

Table 1: Major Pathway Databases for Heterologous Pathway Design

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Applications in Pathway Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG [23] | Multi-organism pathway database | Graphical representations of metabolic pathways; KGML format for computational access | Reference pathway maps; enzyme commission information; organism-specific pathways |

| MetaCyc/BioCyc [23] | Metabolic pathways and enzymes | Curated database of experimentally demonstrated pathways; organism-specific databases | Evidence-based pathway design; enzyme function prediction |

| Reactome [24] | Biological pathways with focus on human data | Curated, peer-reviewed pathway information; sophisticated analysis tools | Pathway analysis; cross-species comparisons |

| BRENDA [21] | Comprehensive enzyme information | Enzyme functional data; kinetic parameters; physiological information | Enzyme selection based on kinetic properties; host compatibility assessment |

These databases provide essential information for identifying potential biosynthetic routes, selecting appropriate enzymes, and understanding pathway stoichiometry and energetics. When designing heterologous pathways, researchers should first exhaustively search these resources to identify existing pathways that can be reconstructed in the chosen host [25]. The Pathway Commons database aggregates pathway information from multiple sources, providing a unified interface for querying biological pathway data across numerous databases [25].

Pathway Design and Analysis Workflow

The computational design of heterologous pathways follows a systematic workflow that integrates data from multiple sources:

Computational Pathway Design Workflow

The process begins with identification of potential biosynthetic routes to the target compound through database mining and literature review. Multiple potential routes may be identified, each with different starting precursors, pathway lengths, and energy requirements. These candidate pathways are then evaluated using constraint-based metabolic modeling approaches such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which uses genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to predict pathway functionality and potential production yields within the context of the host's complete metabolic network [21]. Tools like MetaboAnalyst provide additional capabilities for metabolic pathway analysis and visualization, supporting more than 120 different species [26].

Advanced computational approaches include retrobiosynthesis, which designs novel pathways to target compounds by working backward from the desired product and identifying possible biochemical routes that could form it. This approach can identify non-natural pathways that may have superior properties compared to naturally occurring ones [21].

Experimental Implementation and Optimization

DNA Assembly and Pathway Construction

The physical construction of heterologous pathways involves assembling multiple genetic parts into functional expression units. Several standardized methods have been developed for this purpose:

Golden Gate Assembly: This method uses type IIS restriction enzymes that cleave outside their recognition sequences, enabling seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments without留下scar sequences. It is particularly suitable for pathway construction as it allows precise, modular assembly of multiple genes in a single reaction.

Gibson Assembly: This one-step isothermal method uses 5' exonuclease, DNA polymerase, and DNA ligase to assemble multiple overlapping DNA fragments simultaneously. It is highly efficient for combining large DNA fragments and entire pathways.

CRISPR-Cas Mediated Integration: Genome editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 enable precise integration of pathway genes into specific genomic loci, providing stable expression without the need for antibiotic selection and reducing genetic instability associated with plasmid-based expression.

The choice of assembly method depends on factors such as the number of genes to be assembled, desired precision, and available cloning infrastructure. For large pathways, hierarchical assembly strategies are often employed, where smaller modules are first constructed and then combined into full pathways [22].

Expression Optimization Strategies

Simply assembling pathway genes is insufficient for optimal production. Fine-tuning gene expression is critical for balancing metabolic flux and preventing intermediate accumulation or toxic effects:

Promoter Engineering: Selection and engineering of promoters with appropriate strengths is crucial for balancing pathway expression. Strategies include using promoter libraries of varying strengths, synthetic promoters with designed properties, or inducible promoters for temporal control of pathway expression.

RBS Optimization: The translation initiation rate, controlled by the ribosomal binding site (RBS), significantly influences protein expression levels. Computational tools can design RBS sequences with predicted strengths to optimize the relative expression levels of pathway enzymes.

Codon Optimization: Heterologous genes may contain codons that are rare in the host organism, leading to translational inefficiency. Gene synthesis with host-preferred codons can significantly improve expression levels and protein functionality.

Spatial Organization: Recent advances include controlling the spatial organization of pathway enzymes through synthetic protein scaffolds or bacterial microcompartments to substrate channeling and reduce intermediate diffusion [22].

Host Selection and Engineering

The choice of host organism significantly impacts the success of heterologous pathway implementation. Common platform hosts each offer distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Comparison of Major Microbial Hosts for Heterologous Pathway Implementation

| Host Organism | Type | Advantages | Limitations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli [21] | Gram-negative bacterium | Well-established tools; rapid growth; well-characterized metabolism | Endotoxin production; limited native precursor supply | Shikimic acid, adipic acid, recombinant proteins |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae [21] [22] | Eukaryotic yeast | GRAS status; eukaryotic protein processing; robust industrial performer | Limited tolerance to inhibitors; complex pathway engineering | Artemisinin, steviol glycosides, biofuels |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum [21] | Gram-positive bacterium | Powerful metabolism; industrial robustness; GRAS status | Fewer genetic tools compared to E. coli | Amino acids, organic acids, diamines |

| Pseudomonas putida [21] | Gram-negative bacterium | Metabolic versatility; stress tolerance; utilization of diverse carbon sources | More complex regulation; smaller toolbox | Aromatics, difficult substrates |

| Yarrowia lipolytica [21] | Oleaginous yeast | High lipid accumulation; strong acetyl-CoA flux | Less developed genetic tools | Lipids, terpenoids, fatty acid-derived compounds |

Host engineering often involves deleting competing pathways that divert precursors away from the heterologous pathway, enhancing the supply of key cofactors (e.g., NADPH, ATP, acetyl-CoA), and improving tolerance to pathway intermediates and products [21].

Analytical Framework and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Assessment of Pathway Performance

Robust analytical methods are essential for evaluating the performance of reconstructed heterologous pathways. Key performance metrics include:

Titer: The concentration of the target compound in the fermentation broth, typically measured in grams per liter (g/L). This is the primary metric for production efficiency.

Yield: The amount of product formed per amount of substrate consumed, expressed as gram product per gram substrate (g/g) or as a percentage of the theoretical maximum. Yield reflects carbon efficiency and economic viability.

Productivity: The production rate, measured as gram product per liter per hour (g/L/h). This metric is particularly important for industrial applications where bioreactor throughput determines process economics.

Metabolic Flux: The rate of carbon flow through specific pathways, determined using techniques such as 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), which provides insights into intracellular pathway activity [21].

Advanced analytical platforms like MetaboAnalyst support comprehensive metabolomics analysis, including statistical analysis, biomarker analysis, pathway analysis, and network analysis, enabling systems-level evaluation of pathway performance [26].

Case Studies and Performance Benchmarks

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Selected Heterologous Pathway Implementations

| Product | Host Organism | Pathway Type | Maximum Titer | Yield | Key Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipic Acid [21] | E. coli | Nonnative-existing | Not specified | Not specified | Pathway reconstruction from Thermobifida fusca |

| Butanol [27] | Clostridium spp. | Nonnative-existing | Not specified | 3-fold yield increase | Metabolic engineering of native producer |

| Biodiesel [27] | Multiple | Heterologous | 91% conversion efficiency | Not specified | Lipid engineering; transesterification |

| Ethanol from Xylose [27] | S. cerevisiae | Heterologous | Not specified | ~85% conversion | Xylose utilization pathway introduction |

| Steviol Glycosides [22] | S. cerevisiae | Heterologous | Commercial production | Not specified | Multi-step pathway reconstruction |

These case studies demonstrate that successful heterologous pathway implementation typically requires multiple rounds of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, with iterative improvements based on performance data and systems-level analysis [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous Pathway Reconstruction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly Systems | Golden Gate, Gibson Assembly, Gateway | Modular construction of multi-gene pathways; hierarchical assembly |

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, Red/ET recombination | Precise genomic integration; gene knockouts; multiplexed engineering |

| Expression Regulatory Parts | Inducible promoters (PT7, PGAL), RBS libraries, terminators | Fine-tuning gene expression; metabolic flux control |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, auxotrophic markers (URA3, LEU2), counter-selection markers | Stable pathway maintenance; marker recycling; sequential engineering |

| Vector Systems | Plasmid libraries (different copy numbers), integrative vectors, shuttle vectors | Gene expression optimization; pathway stability; cross-species applications |

| Metabolic Analytes | LC-MS/MS standards, GC-MS derivatization kits, NMR isotopes | Pathway intermediate tracking; flux analysis; product quantification |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, MetaCyc, Reactome, BRENDA | Pathway design; enzyme selection; host-pathway integration |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MetaboAnalyst, OptFlux, antiSMASH | Pathway analysis; flux prediction; natural pathway identification |

This toolkit enables the entire pathway reconstruction workflow, from initial design and DNA construction to functional analysis and optimization. The selection of appropriate tools depends on the specific host organism, pathway complexity, and desired production metrics [21] [22] [26].

Future Perspectives and Emerging Technologies

The field of heterologous pathway reconstruction continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in several key technologies:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI approaches are increasingly being applied to pathway design, enzyme engineering, and host optimization. Machine learning models can predict enzyme function, optimize codon usage, and identify optimal gene expression levels based on training data from previous engineering efforts [21].

Automated Strain Engineering: High-throughput robotic systems enable the construction and testing of thousands of pathway variants, dramatically accelerating the DBTL cycle. Automation is particularly powerful when combined with combinatorial assembly methods and micro-cultivation systems [21].

de Novo Pathway Design: Computational tools are advancing beyond the reconstruction of natural pathways to the design of completely novel biosynthetic routes that may not exist in nature. These nonnative-created pathways can bypass regulatory bottlenecks or utilize different precursor pools [21].

Multi-omics Integration: The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data provides systems-level understanding of pathway function and host responses, enabling more rational design strategies [21] [26].

Expanded Host Range: While E. coli and S. cerevisiae remain popular hosts, there is growing interest in non-conventional hosts with specialized metabolic capabilities, such as Yarrowia lipolytica for lipid-derived compounds, Pseudomonas putida for aromatics, and photosynthetic organisms for direct CO2 utilization [21] [27].

As these technologies mature, heterologous pathway reconstruction will become increasingly predictable and efficient, expanding the range of compounds accessible through microbial production and contributing to the development of a more sustainable bio-based economy [21] [27] [22].

In the field of metabolic engineering, particularly in the development of microbial cell factories, the ability to reconstruct, analyze, and engineer metabolic networks is paramount. These networks provide a comprehensive blueprint of an organism's metabolism, enabling researchers to predict cellular behavior and identify strategic interventions for optimizing the production of valuable compounds. The process leverages genomic, biochemical, and physiological data to build computational models that simulate metabolic flux. This guide provides an in-depth technical resource for scientists and drug development professionals, detailing the essential databases, computational tools, and methodologies that underpin modern metabolic network analysis. Framed within the context of microbial cell factory development, it emphasizes practical protocols and curated resources for advancing research in sustainable chemical and therapeutic production.

Core Databases for Metabolic Information

Curated databases are foundational to metabolic network reconstruction, providing the structured, annotated biological data required for building accurate models. The table below summarizes key databases critical for metabolic engineering research.

Table 1: Core Databases for Metabolic Network Reconstruction

| Database Name | Primary Content & Function | Key Features | Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG [28] [29] | A repository of curated reference metabolic pathways, genes, enzymes, and reactions. | Standardized nomenclature; Manually drawn pathway maps; Links genes to pathways via KO identifiers. | Serves as a reference for automated reconstruction tools; used for functional annotation of genomes. |

| MetaCyc [29] [30] | A curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes from all domains of life. | Contains organism-specific pathway diagrams; literature references for reactions. | Used as a knowledge base for predicting metabolic pathways in sequenced genomes; supports enzyme discovery. |

| BiGG [29] | A knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions. | Manually curated, mass-and-charge balanced models; includes compartmentalization and gene-protein-reaction associations. | Provides high-quality, ready-to-use models for simulation and analysis (e.g., flux balance analysis). |

| BioCyc [29] | A collection of thousands of Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs). | Includes tools for data visualization, omics data analysis, and comparative pathway analysis. | Enables comparative metabolism studies and analysis of omics data in the context of metabolic pathways. |

Computational Tools for Reconstruction and Analysis

A robust ecosystem of software tools has been developed to translate data from metabolic databases into functional, computable models. These tools facilitate the reconstruction process, enable advanced topological and functional analyses, and allow for the simulation of metabolic phenotypes.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Methodology / Key Innovation | Input/Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| MetaDAG [28] | Automated metabolic network reconstruction and analysis. | Constructs a reaction graph and a metabolic Directed Acyclic Graph (m-DAG) by collapsing strongly connected components. | Input: KEGG organisms, reactions, enzymes, or KOs. Output: Interactive network visualizations, core/pan metabolism. |

| Model SEED [29] | High-throughput, automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models. | Integrates genome annotations, gap-filling, and thermodynamic analysis to draft and refine models. | Input: Genome annotation data. Output: Draft metabolic models in SBML and other formats. |

| Sensitivity Correlation Analysis [31] | Functional comparison of metabolic networks across species. | Quantifies similarity of flux responses to perturbations; captures how network context shapes gene function. | Input: Genome-scale metabolic models (GSMs). Output: Functional similarity metrics, phylogenetic trees. |

| SBMLKinetics [32] | Annotation-independent classification of reaction kinetics. | Classifies reactions using a two-dimensional scheme (Kinetics Type and Reaction Type) based on algebraic expressions and stoichiometry. | Input: SBML models. Output: Classification of kinetic laws, recommendations for modelers. |

| KinModGPT [33] | Automatic generation of SBML kinetic models from natural language text. | Uses GPT as a natural language interpreter and Tellurium to generate SBML code. | Input: Natural language descriptions of biochemical systems. Output: Valid SBML kinetic models. |

Specialized Workflows and Applications

Functional Comparison with Sensitivity Analysis: A key challenge is comparing metabolic functions across different organisms, where mere presence or absence of reactions is insufficient. Sensitivity correlations offer a refined method by quantifying how perturbations in enzyme-catalyzed reactions affect metabolic fluxes across different network structures [31]. This approach links genotype to phenotype by considering the entire network context, enabling the functional alignment of reactions and inference of phylogenetic relationships. For instance, this method has been used to correctly separate bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea in a phylogenetic tree based on 16 manually curated GSMs [31].

Kinetic Model Generation and Classification: The choice of kinetic laws is critical for creating dynamic models that accurately predict system behavior. Tools like SBMLKinetics provide an annotation-independent method to classify and recommend kinetic laws (e.g., mass action, Michaelis-Menten, Hill kinetics) based on the reaction's stoichiometry and the algebraic form of the rate law [32]. For rapid model development, KinModGPT leverages large language models to automatically generate SBML-encoded kinetic models from natural language descriptions of biochemical reactions, significantly accelerating the modeling process [33].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

This section details a standard workflow for genome-scale metabolic model reconstruction and its application in strain engineering, using the improvement of spinosad production in Saccharopolyspora spinosa as a case study [34].

Protocol: Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Reconstruction and Validation

Objective: To reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic network for a target microorganism and use it to identify metabolic engineering targets for enhanced product yield.

Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic Data: Annotated genome sequence of the target organism (e.g., Saccharopolyspora spinosa).

- Bioinformatics Databases: KEGG [28], MetaCyc [30], and other resources from Table 1 for pathway and reaction data.

- Reconstruction Software: Tools such as Model SEED [29] or platform-specific scripts for automated draft reconstruction.

- Simulation Environment: A software platform capable of running constraint-based modeling, such as the COBRA Toolbox.

- Culture Media: Appropriate growth media for the target organism (e.g., for S. spinosa).

- Chemical Standards: Analytical standards for the target product (e.g., spinosad) and key metabolites for validation.

Methodology:

Draft Reconstruction:

- Data Retrieval: Using the annotated genome, systematically query databases (KEGG, MetaCyc) to generate a list of all metabolic reactions inferred to be present in the organism.

- Compartmentalization: Define the subcellular compartments relevant to the organism (e.g., cytosol, mitochondria, periplasm) and assign reactions accordingly.

- Network Assembly: Construct a stoichiometric matrix (S) where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. This forms the core of the model.

Model Curation and Refinement:

- Gap Analysis: Identify "gaps" in the network—metabolites that can be produced but not consumed, or vice-versa. Use biochemical literature and comparative genomics to fill these gaps with missing reactions.

- Biomass Definition: Formulate a biomass reaction that defines the stoichiometric composition of major cellular constituents (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, lipids) required for cell growth. This reaction is the primary objective function in flux balance analysis (FBA).

- Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association: Link metabolic reactions to their corresponding genes using Boolean rules (e.g.,

Gene_A and Gene_B), enabling gene-centric analysis.

In Silico Validation:

- Test the model's ability to produce known biomass precursors and essential metabolites under defined growth conditions.

- Perform in silico gene essentiality screens and compare the predictions with experimental data, if available.

- As performed for S. spinosa, simulate the impact of nutrient supplementation (e.g., amino acids) on growth or product formation and compare with experimental fermentation data to validate model predictions [34].

Target Identification and Engineering:

- Use the validated model to simulate metabolic flux distributions and identify engineering targets. For example, in silico analysis of S. spinosa suggested that modulating transhydrogenase (PntAB) activity could optimize NADPH/NADH balance and enhance spinosad yield [34].

- Genetic Manipulation: Overexpress the identified target gene (e.g., pntAB) in the host strain using genetic engineering tools like CRISPR-Cas systems [35].

- Fermentation and Validation: Cultivate the engineered strain in a bioreactor and measure the final product titer. In the case of S. spinosa with overexpressed pntAB, spinosad production increased by 86.5% compared to the wild-type strain [34].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Workflow for Model Reconstruction and Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful metabolic network analysis and strain engineering rely on a suite of computational and experimental reagents. The following table details key resources for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Category / Item | Specific Examples / Formats | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Standard File Formats | SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) [29] [32] [33], BioPAX [29] | Enables exchange and reuse of biochemical network models between different software tools. |

| Genome Annotation & Modeling Suites | Model SEED [29], Pathway Tools [29], SEED framework [29] | Provides integrated platforms for high-throughput genome annotation and automated draft model reconstruction. |

| Simulation & Modeling Environments | COBRA Toolbox, Tellurium [33], COPASI [32] | Offers environments for constraint-based modeling, dynamic simulation, and analysis of biochemical networks. |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas Systems [35] | Enables precise genome editing and transcriptional regulation in microbial cell factories for metabolic reprogramming. |

| Flux Analysis Technologies | C13 Isotope Labeling [36], FRET-based Nanosensors [36] | Measures metabolic fluxes: C13 provides system-wide flux maps, while FRET sensors offer subcellular resolution of metabolite dynamics. |

The systematic reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks represent a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering. By leveraging curated biological databases, sophisticated computational tools for reconstruction and functional analysis, and integrated experimental-computational protocols, researchers can transform genomic blueprints into predictive models of cellular function. This structured approach, framed within the development of microbial cell factories, provides a powerful roadmap for identifying key metabolic interventions. As tools continue to evolve—especially with the integration of AI for model generation and more sophisticated functional comparison algorithms—the precision and speed of designing high-yield microbial production strains will be profoundly enhanced, accelerating the development of sustainable bioprocesses for drugs and chemicals.

Methodological Toolbox: From Gene Editing to Systems-Level Engineering

Precision Genome Engineering with CRISPR/Cas9 and Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE)

The development of efficient microbial cell factories is a central goal of modern industrial biotechnology, enabling the sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and platform chemicals. Metabolic engineering aims to rewire microbial metabolism to optimize the production of target compounds, a process that often requires simultaneous modification of multiple genes within complex regulatory networks [37] [38]. Multiplex genome engineering has emerged as a transformative approach, allowing researchers to make coordinated changes at multiple genomic locations in a single experiment, dramatically accelerating the design-build-test cycle for strain development [39] [40].

Before the advent of these technologies, metabolic engineers faced significant limitations. Traditional methods like homologous recombination were inefficient and labor-intensive, while earlier nuclease-based platforms such as Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) required complex protein engineering for each target site, making simultaneous modification of multiple loci technically challenging and costly [39]. The field was revolutionized by two complementary technologies: Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE), which enables large-scale programming through oligonucleotide libraries, and CRISPR-Cas9 systems, which provide RNA-guided precision for targeted genome modifications [40] [41]. When integrated within metabolic engineering frameworks, these technologies enable comprehensive optimization of complex phenotypes in microbial hosts by simultaneously targeting multiple pathway genes, regulatory elements, and competing metabolic routes [42] [38].

Technology Fundamentals: Mechanisms and Components

CRISPR-Cas9 System: Components and Mechanisms