Advanced Biosensor Development for High-Throughput Metabolite Screening: Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biosensor technology for high-throughput metabolite screening, catering to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Biosensor Development for High-Throughput Metabolite Screening: Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in biosensor technology for high-throughput metabolite screening, catering to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of transcription factor-based, whole-cell, and nucleic acid-based biosensors, detailing their mechanisms and design considerations. The content covers cutting-edge methodological applications across various screening platforms—including well plates, agar plates, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)—highlighting their use in metabolic pathway optimization and functional strain identification. The article further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, such as statistical modeling and Design of Experiments (DoE), to enhance biosensor performance parameters like dynamic range and sensitivity. Finally, it examines validation frameworks and comparative analyses against traditional analytical methods, discussing the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for improved data interpretation and predictive modeling in biomedical and clinical research contexts.

Biosensor Fundamentals: Core Principles and Design for Metabolite Detection

Biosensors are sophisticated analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes with high specificity and sensitivity [1]. In the context of high-throughput metabolite screening for drug development, biosensors serve as powerful tools for rapidly quantifying metabolic fluxes, identifying enzyme inhibitors, and optimizing microbial production strains [2]. The fundamental operation involves the biorecognition element selectively binding to the target metabolite, followed by the transducer converting this biological event into a quantifiable electrical, optical, or thermal signal [3] [4]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these core components, detailing their characteristics, selection criteria, and implementation protocols to accelerate biosensor development for metabolic research.

Biorecognition Elements

Biorecognition elements are the molecular components that confer specificity to a biosensor by interacting selectively with a target analyte. The choice of biorecognition element profoundly influences the sensor's sensitivity, selectivity, reproducibility, and stability [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Biorecognition Elements for Metabolite Sensing

| Biorecognition Element | Mechanism of Action | Typical Targets | Affinity (Kd) | Stability | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies [5] [6] | Affinity-based binding to form immunocomplexes | Proteins, peptides, large molecules | nM - pM | Moderate (susceptible to denaturation) | High specificity and affinity; wide commercial availability | Animal-based production is costly; batch-to-batch variation; limited shelf life |

| Enzymes [5] [6] | Catalytic conversion of substrate to measurable product | Small molecules, substrates, inhibitors | Varies (Km) | Moderate | Signal amplification via catalysis; well-characterized | Specificity can be for a class of compounds, not a single analyte |

| Nucleic Acids (Aptamers) [5] [6] | Folding into 3D structures for affinity binding | Ions, small molecules, proteins, cells | nM - µM | High (tolerant of wide pH/temperature) | Synthetic production; small size; "induced fit" binding | SELEX process for development can be costly and time-consuming |

| Transcription Factors (TFs) [2] [7] | Allosteric regulation; binding to DNA promoter sequences upon analyte recognition | Metabolites, ions | µM - nM | High in cell-free systems | Native biological regulators; ideal for metabolic pathways | Can require engineering for optimal performance [8] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [5] [1] | Synthetic polymers with templated cavities for analyte binding | Small molecules, toxins | µM - nM | Very high (robust, reusable) | Excellent stability; no biological source required | Can suffer from heterogeneity in binding sites |

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor for Metabolite Quantification in a Cell-Free System

This protocol is adapted from methods used to develop and apply biosensors for metabolites like lactate and heavy metals [8] [7]. It outlines the steps for employing a TF-based biosensor in a cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) environment to quantify a target metabolite.

Principle: An allosteric transcription factor (TF) is encapsulated within a reaction vessel. Upon binding to the target metabolite, the TF undergoes a conformational change, enabling it to bind a promoter and initiate transcription/translation of a reporter gene (e.g., fluorescent protein). The fluorescence intensity is proportional to the metabolite concentration [2] [7].

Materials:

- Purified Transcription Factor (TF): Specific to your target metabolite (e.g., purified PbrR for lead sensing [7]).

- DNA Construct: Plasmid containing the TF-specific promoter fused to a reporter gene (e.g., eGFP, luciferase) [7].

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System: A commercial kit (e.g., PUREfrex2.0 [8]) or homemade E. coli extract.

- Reaction Vessels: 96-well or 384-well optical plates.

- Microplate Reader: Capable of measuring fluorescence or luminescence.

- Analyte Standards: Serial dilutions of the pure target metabolite for generating a calibration curve.

- Test Samples: Cell lysates or culture media containing the metabolite of unknown concentration.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In each well of the microplate, mix the following components on ice:

- 10 µL of CFPS reaction mix.

- 2 µL (~ 50 ng) of the DNA construct.

- 1 µL of the purified TF.

- 2 µL of analyte standard (for the calibration curve) or test sample.

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL. Include a negative control with water instead of the analyte and a positive control with a known saturating concentration of the analyte.

Incubation and Signal Generation: Seal the plate and incubate at 30-37°C for 2-6 hours in the microplate reader to allow for the coupled transcription, translation, and reporter maturation.

Signal Measurement: Measure the fluorescence/ luminescence intensity at appropriate time intervals (endpoint or kinetic mode) using the pre-configured settings on the microplate reader.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the fluorescence intensity of the standards against their known concentrations to generate a standard calibration curve.

- Fit the data to a non-linear regression (e.g., sigmoidal dose-response curve) to determine the dynamic range and limit of detection (LOD).

- Use the resulting equation from the standard curve to calculate the concentration of the target metabolite in the test samples based on their measured signal.

Transducers

The transducer is the component that converts the biorecognition event into a measurable analytical signal. The selection of a transduction mechanism is critical and depends on the nature of the biorecognition event and the requirements of the application, particularly in high-throughput settings where speed and miniaturization are paramount [3] [9].

Table 2: Overview of Transducer Technologies for Biosensing

| Transducer Type | Detection Principle | Measurable Signal | Throughput Compatibility | Example Application in Metabolite Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical [3] [4] | Measures changes in electrical properties due to a bio-recognition event. | Current (Amperometric), Potential (Potentiometric), Impedance (Impedimetric) | High (compatible with microelectrode arrays) | Detection of electroactive metabolites (e.g., glucose, lactate); enzyme activity assays. |

| Optical [3] [9] [8] | Measures changes in the properties of light. | Fluorescence Intensity/Lifetime (FLIM), Absorbance, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | High (compatible with well plates and flow cytometry) | Genetically encoded biosensors (e.g., LiLac [8]); label-free binding studies. |

| Piezoelectric [9] [4] | Measures change in the resonance frequency of a crystal due to mass adsorption. | Frequency Shift (Hz) | Medium | Detection of mass changes from binding of large biomolecules or whole cells. |

| Thermal [9] [4] | Measures the enthalpy change of a biochemical reaction. | Temperature Change (ΔT) or Heat (Calorimetric) | Low | Enzyme kinetic studies and inhibitor screening. |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of a Microbial Library Using FACS and a Fluorescent Biosensor

This protocol describes a high-throughput method for screening large libraries of microbial variants (e.g., for metabolic engineering) using a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [2].

Principle: A microbial library (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) is engineered to express a biosensor whose fluorescence intensity or lifetime changes in response to the intracellular concentration of a target metabolite. Cells with higher fluorescence are isolated using FACS, as they are likely to be superior producers of the metabolite [2] [8].

Materials:

- Microbial Library: A diverse population of cells (e.g., generated via error-prone PCR, ARTP mutagenesis, or CRISPR-based editing) [2].

- Fluorescent Biosensor Plasmid: A genetically encoded biosensor responsive to the target metabolite (e.g., LiLac for lactate [8]).

- Flow Cytometer / FACS Machine: Capable of detecting the biosensor's fluorescence (e.g., 488 nm laser for GFP).

- Growth Media: Appropriate sterile media for the microbial strain.

- Glycerol Stock Solution: 40% (v/v) sterile glycerol for preserving sorted cells.

Procedure:

- Library Transformation & Culture: Transform the biosensor plasmid into the microbial library. Grow the transformed library in an appropriate medium to mid-log phase under selective pressure.

Sample Preparation: Harvest cells by gentle centrifugation and resuspend them in an appropriate sorting buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) to a concentration of ~10^6 - 10^7 cells/mL. Keep samples on ice until sorting to minimize metabolic changes.

FACS Gating and Sorting:

- Pass the control strain (with low metabolite production) through the FACS to establish the baseline fluorescence.

- Create a sorting gate set to collect the top 0.1-5% of cells with the highest fluorescence intensity.

- Pass the entire library through the FACS and sort the gated high-fluorescence population into a tube containing recovery media or directly onto an agar plate.

Recovery and Validation:

- Allow the sorted cells to recover in rich media overnight.

- Plate the cells on selective agar plates to obtain single colonies.

- Inoculate individual colonies into deep-well plates for small-scale production.

- Validate the metabolite titer of the sorted hits using a gold-standard analytical method like LC-MS/MS to confirm the correlation between biosensor signal and production yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development and Screening

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) System [8] [7] | Provides the transcriptional/translational machinery for biosensor expression outside a living cell. | Rapid, compartmentalized screening of biosensor variants or for detection in toxic samples [7]. |

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) [2] [7] | Native biological receptors that undergo conformational change upon metabolite binding. | Engineering biosensors for specific metabolites like heavy metals (MerR, PbrR) or central carbon metabolites [7]. |

| Droplet Microfluidics [8] | Encapsulates single cells or biosensor reactions in picoliter-volume droplets for ultra-high-throughput screening. | Screening millions of variants in a single experiment, as demonstrated in the BeadScan platform [8]. |

| Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying) Reagents [7] | Stabilizes cell-free biosensor reactions for long-term storage at room temperature. | Creating ready-to-use, shelf-stable paper-based biosensors for point-of-care or field deployment [7]. |

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Reporters [2] [8] | Proteins (e.g., eGFP, mCherry) whose fluorescence intensity or lifetime serves as the biosensor output. | Real-time monitoring of metabolite dynamics in live cells or in vitro systems [8]. |

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are sophisticated genetic tools that enable the detection of specific metabolites and the dynamic regulation of cellular pathways. These biosensors function by leveraging allosteric transcription factors (aTFs), which are proteins that undergo conformational changes upon binding to small molecules, thereby modulating their affinity for specific DNA operator sequences and controlling downstream gene expression [10] [11]. This fundamental mechanism allows TFBs to convert intracellular metabolite concentrations into quantifiable outputs such as fluorescence, luminescence, or colorimetric changes, making them invaluable for real-time monitoring and control in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology [10] [12].

The significance of TFBs extends across multiple domains, including high-throughput screening of microbial strain libraries, dynamic metabolic pathway control, environmental monitoring, and biomedical diagnostics [10] [13]. Their genetic tunability, modular architecture, and ability to interface with host regulatory networks position them as central components in the development of next-generation biosensing technologies [12]. Unlike traditional biosensors that rely on enzymes or antibodies, TFBs offer the unique advantage of real-time intracellular sensing and seamless integration with genetic circuits, enabling sophisticated programming of cellular behavior [10].

As the field advances, TFBs are being integrated with engineered living materials (ELMs), combining living cells with synthetic matrices to create responsive, adaptive systems with enhanced stability and functionality for applications in environmental monitoring and smart infrastructure [14]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms, regulatory circuit designs, performance parameters, experimental protocols, and cutting-edge applications of TFBs, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for biosensor implementation.

Molecular Mechanisms and Regulatory Circuits

Core Sensing Mechanisms

The operational principle of TF-based biosensors centers on aTF function, where ligand binding induces conformational changes that alter DNA-binding affinity [10] [11]. These systems typically comprise three essential components: a sensing element (the aTF), a genetic operator (promoter/operator sequence), and a reporter gene. The mechanism proceeds through three fundamental stages:

- Analyte Recognition: The aTF specifically binds its target ligand (effector molecule), inducing structural rearrangement.

- Signal Transduction: This conformational change modulates the aTF's interaction with its cognate operator sequence.

- Output Generation: Altered operator binding activates or represses transcription of the reporter gene, producing a measurable signal [10].

These interactions follow specific operational modes based on the aTF's native function. Table 1 outlines the four primary modes of aTF action in biosensor design.

Table 1: Modes of Action for Allosteric Transcription Factors in Biosensor Design

| Mode of Action | Mechanism | Ligand Effect | Example Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repression of Repressor | Ligand binding causes repressor to dissociate from DNA | Derepression of reporter gene expression | TetR family regulators [11] |

| Activation of Activator | Ligand binding enables activator to recruit RNA polymerase | Activation of reporter gene expression | AraC family regulators [11] |

| Activation of Repressor | Ligand binding enhances repressor's DNA affinity | Enhanced repression of reporter gene | Some MerR family regulators [11] |

| Repression of Activator | Ligand binding inactivates activator's DNA binding | Reduced activation of reporter gene | Unknown natural occurrences, possible through engineering |

The following diagram illustrates the genetic circuit organization and regulatory logic for a repressor-based TFB system:

Figure 1: Regulatory logic of a repressor-based transcription factor biosensor. In the absence of ligand, the aTF binds the operator and represses transcription. Ligand binding induces a conformational change causing aTF dissociation, leading to derepression and reporter gene expression.

Advanced Regulatory Circuit Designs

Engineering sophisticated regulatory circuits expands TFB capabilities beyond simple induction/repression systems. A notable example is the LC100-2 biosensor for ultra-trace cadmium detection, which incorporates the LacI protein as both a signal amplifier and negative feedback module [15]. This circuit employs a "CadR-PJ23100-PT7-cadO-lacO-cadO-mRFP1-LacI" architecture, where LacI acts as an autoregulatory negative feedback component, significantly enhancing sensitivity while minimizing background leakage [15]. This design achieved a record low detection limit of 0.00001 nM for Cd²⁺, demonstrating the power of advanced circuit engineering.

Another innovative approach utilizes hybrid promoters that respond to multiple inputs. For instance, the PT7-cadO-lacO-cadO dual-input promoter integrates binding sites for both CadR (Cd²⁺-responsive) and LacI, enabling signal processing that improves response characteristics and reduces false positives [15]. Such multi-input circuits facilitate complex logical operations within cells, broadening biosensor application scope.

The emerging field of engineered living materials (ELMs) further demonstrates advanced circuit integration, where TFBs are embedded in hydrogel-encapsulated cells to create robust environmental sensors. For example, E. coli expressing a ZntR-based Cd²⁺ biosensor within polyacrylamide-alginate hydrogels maintained functionality for over five days, detecting concentrations as low as 0.01 μM [14].

Performance Characterization and Quantitative Data

Key Performance Metrics

Systematic evaluation of TFB performance requires quantification of several critical parameters that collectively define biosensor efficacy and application suitability [16] [13]:

- Dynamic Range: The fold-change between maximal and minimal reporter output (induced vs. uninduced states). A wider dynamic range provides better signal discrimination.

- Sensitivity: The concentration range over which a biosensor responds, often defined by the EC₅₀ (concentration producing half-maximal response) or the limit of detection (LOD).

- Specificity: The ability to distinguish target ligands from structurally similar molecules, minimizing false positives.

- Response Time: The duration required to reach half-maximal output after ligand exposure, crucial for real-time monitoring applications.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: The ratio between output signal in induced versus uninduced states, indicating output clarity and measurement reliability [16].

Quantitative Performance of Representative Biosensors

Table 2 summarizes the performance characteristics of recently developed TFBs, highlighting the remarkable sensitivity achievable through circuit engineering.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Transcription Factor | Host Organism | Detection Limit | Dynamic Range | Key Engineering Strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd²⁺ | CadR with LacI feedback | E. coli | 0.00001 nM | 3748-fold improvement | Negative feedback circuit | [15] |

| Flavonoids | Wild-type TtgR | E. coli | 0.01 mM | Not specified | Native regulator exploitation | [17] |

| Resveratrol | TtgR N110F mutant | E. coli | 0.01 mM | >90% accuracy | Binding pocket engineering | [17] |

| Quercetin | TtgR N110F mutant | E. coli | 0.01 mM | >90% accuracy | Binding pocket engineering | [17] |

| Naltrexone | Engineered TtgR variant | E. coli | Not specified | High (F-score >1) | Sensor-seq high-throughput screening | [18] |

| Quinine | Engineered TtgR variant | E. coli | Not specified | High (F-score >1) | Sensor-seq high-throughput screening | [18] |

| Pb²⁺ | PbrR | B. subtilis | 0.1 μg/L | Not specified | ELM encapsulation | [14] |

| Hg²⁺ | MerR | B. subtilis | 0.05 μg/L | Not specified | ELM encapsulation | [14] |

The ultra-sensitive Cd²⁺ biosensor LC100-2 exemplifies how circuit optimization dramatically enhances performance. The initial single-input biosensor CP100 already met WHO detection requirements, but the incorporation of LacI-based amplification and negative feedback increased sensitivity by 3748-fold, enabling detection in the ultra-trace range (0.00001–0.02 nM) [15]. This biosensor also demonstrated excellent specificity for Cd²⁺ against other divalent metal ions and performed effectively in real water samples with minimal volume requirements (1 μL) [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementation and Validation of a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor

This protocol describes the procedure for constructing and characterizing a TFB in E. coli, based on established methodologies from recent literature [15] [17].

Materials Required

- Plasmid Vectors: pCDF-Duet or pET-21a(+) for gene expression [17]

- Host Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) for protein expression [17]

- Restriction Enzymes: NdeI, NotI, BglII, XbaI for molecular cloning [17]

- Ligase: T4 DNA Ligase for fragment assembly

- Growth Media: Lysogeny Broth (LB) for cell cultivation [17]

- Reporter Gene: eGFP, mRFP1, or other fluorescent protein genes

- Inducer Compounds: Target analyte dissolved in DMSO or water [17]

Procedure

Day 1: Circuit Assembly

- Amplify the coding sequence of your chosen transcription factor (e.g., TtgR, CadR, ZntR) and its native promoter/operator region from genomic DNA or a synthetic template using PCR with primers containing appropriate restriction sites [17].

- Digest both the PCR product and plasmid vector with compatible restriction enzymes (e.g., NdeI/NotI for the TF, BglII/XbaI for the promoter) [17].

- Purify digested fragments using a gel extraction kit and ligate them into the vector using T4 DNA ligase.

- Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli DH5α cells for propagation and isolate validated plasmid DNA [17].

Day 2: Biosensor Strain Preparation

- Co-transform the validated TF/promoter plasmid with a reporter plasmid containing the output gene (e.g., eGFP) under control of the TF-responsive promoter into your expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21) [17].

- Plate transformed cells on LB agar with appropriate antibiotics and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Day 3: Biosensor Assay

- Inoculate single colonies into liquid LB medium with antibiotics and grow overnight at 37°C with shaking [17].

- Dilute overnight cultures 1:100 into fresh medium in a multi-well plate and grow to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5).

- Add varying concentrations of the target analyte to separate wells, including negative controls (vehicle only).

- Incubate with shaking for an additional 4-6 hours or until a clear response is observed.

Day 3: Data Collection and Analysis

- Measure fluorescence output (e.g., excitation/emission 488/510 nm for eGFP) and optical density (OD₆₀₀) using a plate reader.

- Calculate normalized fluorescence by dividing fluorescence values by OD₆₀₀ to account for cell density differences.

- Plot dose-response curves (normalized fluorescence vs. analyte concentration) and determine key parameters: dynamic range, EC₅₀, and limit of detection.

Protocol 2: Engineering Biosensor Specificity Through Binding Pocket Modification

This protocol describes a structure-guided approach to modify aTF ligand specificity, based on successful TtgR engineering campaigns [17] [18].

Materials Required

- Template Plasmid: Plasmid containing wild-type ttgR gene [17]

- Mutagenesis Primers: Primers designed to introduce specific mutations

- High-Fidelity Polymerase: PfuTurbo for site-directed mutagenesis [17]

- Docking Software: AutoDock Vina or similar for computational screening

- Ligand Library: Compounds for specificity profiling

Procedure

Step 1: Computational Analysis

- Obtain the protein structure of your target aTF from the Protein Data Bank or generate a homology model using AlphaFold2 [11].

- Identify residues in the ligand-binding pocket through structural analysis and literature review.

- Perform molecular docking of target ligands to identify potential mutations that would enhance binding affinity or alter specificity.

Step 2: Site-Directed Mutagenesis

- Design mutagenic primers targeting key binding pocket residues (e.g., Asn110, His114, Val96, Ile141 in TtgR) [17].

- Perform PCR amplification using PfuTurbo polymerase with the wild-type plasmid as template [17].

- Digest parental DNA with DpnI and transform the mutated plasmid into E. coli DH5α.

- Verify mutations by Sanger sequencing of the entire TF coding region.

Step 3: Functional Characterization

- Introduce mutant TF plasmids into biosensor strains and evaluate responses to target and non-target ligands following Protocol 1.

- Select variants with improved specificity or altered ligand recognition profiles for further analysis.

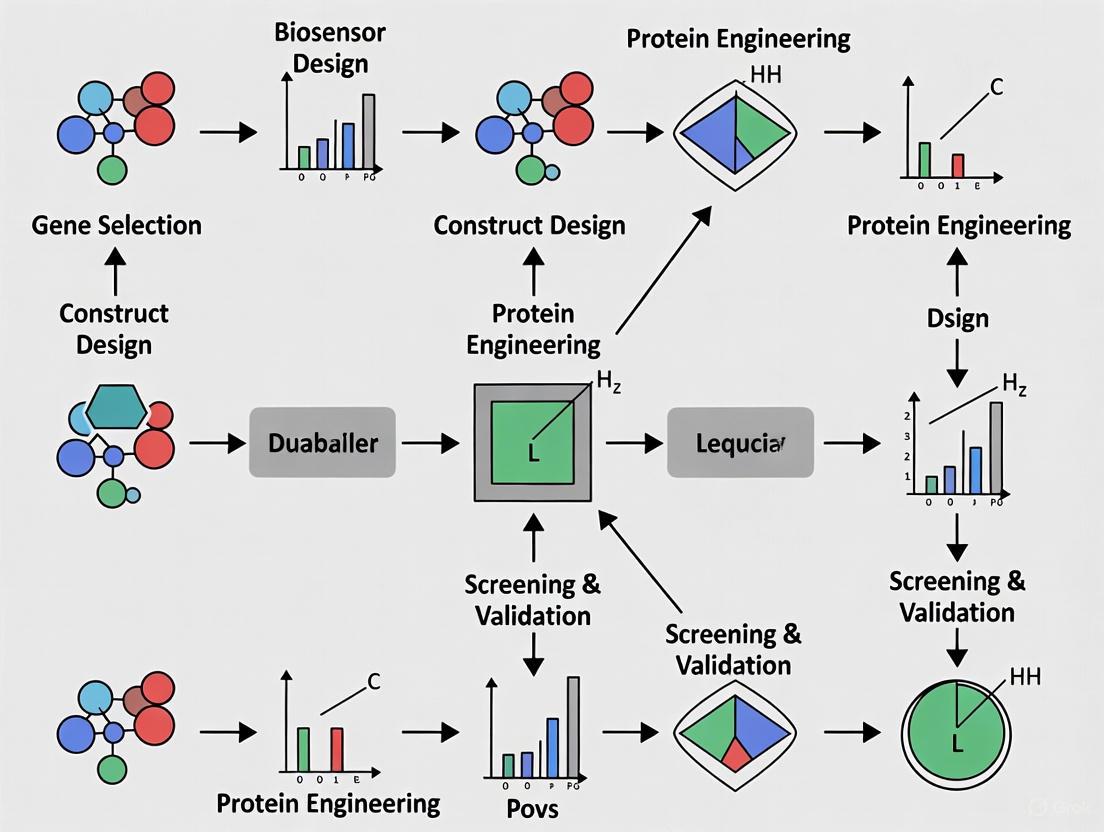

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in the biosensor engineering and optimization process:

Figure 2: Biosensor engineering and optimization workflow. The process begins with component selection informed by biological databases, followed by iterative engineering cycles to optimize performance parameters for specific applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3 catalogues critical reagents, materials, and computational tools for developing and implementing TF-based biosensors, compiled from referenced studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for TFB Development

| Category | Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application Purpose | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pCDF-Duet, pET-21a(+) | Medium copy number, compatible origins | Housing sensing and reporter circuits | Novagen [17] |

| Host Strains | E. coli BL21(DE3) | T7 RNA polymerase expression | Protein expression and biosensor hosting | Stratagene [17] |

| Reporter Genes | eGFP, mRFP1, mCherry | Fluorescence emission spectra | Quantitative signal output | Common fluorescent proteins [17] [14] |

| Native TFs | TtgR, CadR, ZntR, MerR | Respond to flavonoids, Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺, Hg²⁺ | Sensing element for different analyte classes | Literature [15] [17] |

| Engineering Tools | PfuTurbo Polymerase | High-fidelity DNA amplification | Site-directed mutagenesis | Invitrogen [17] |

| Screening Platform | Sensor-seq | RNA barcoding + deep sequencing | High-throughput variant characterization | Custom implementation [18] |

| Computational Tools | AlphaFold2, DeepTFactor | Protein structure/function prediction | aTF identification and engineering | Public servers [11] |

| Databases | GroovDB, RegTransBase | Curated aTF-ligand interactions | Identifying natural biosensor components | Online databases [11] [18] |

Applications in High-Throughput Metabolite Screening

TF-based biosensors have become indispensable tools for high-throughput screening (HTS) in metabolic engineering, enabling rapid identification of high-producing microbial strains [10] [13]. By linking intracellular metabolite concentrations to easily measurable outputs like fluorescence, TFBs facilitate the screening of large mutant libraries that would be impractical to analyze with traditional chromatographic methods [10]. This application is particularly valuable for optimizing biosynthetic pathways for biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and specialty chemicals.

The integration of TFBs with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) creates a powerful platform for strain development. For example, biosensors responsive to key metabolic intermediates such as malonyl-CoA, mevalonate, or flavonoids have been used to screen combinatorial libraries of enzyme variants and regulatory elements, leading to significant improvements in pathway flux and product yield [13]. This approach bypasses the need for laborious small-scale fermentations and analytical chemistry, dramatically accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle in metabolic engineering.

Recent advances in HTS applications include the development of Sensor-seq, a highly multiplexed platform that combines RNA barcoding with deep sequencing to characterize thousands of aTF variants simultaneously [18]. This technology enables the identification of rare, functional biosensors from large libraries, overcoming the limitations of conventional screening methods. In one application, Sensor-seq screened 17,737 TtgR variants against eight ligands, identifying biosensors for diverse compounds including naltrexone and quinine with high dynamic range and specific response profiles [18].

Beyond conventional HTS, TFBs are increasingly deployed for dynamic metabolic control, where pathway regulation occurs in response to real-time metabolite levels [16] [11]. This approach mimics natural regulatory networks and helps overcome metabolic imbalances that limit productivity in statically engineered strains. For instance, a TFB responsive to a pathway intermediate can dynamically control rate-limiting enzymes, maintaining optimal flux and preventing toxic metabolite accumulation [16].

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of TF-based biosensors is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Computational design and artificial intelligence are playing increasingly prominent roles, with tools like Cello enabling in silico optimization of genetic circuits before construction [10] [12]. Machine learning algorithms trained on large-scale screening data, such as those generated by Sensor-seq, are accelerating the engineering of aTFs with novel specificities and improved performance characteristics [18].

Integration with engineered living materials represents another frontier, where TFBs are encapsulated in synthetic matrices to create robust, portable sensing devices [14]. These systems protect the biological components from environmental stresses while maintaining functionality for extended periods. Examples include hydrogel-encapsulated biosensors for environmental monitoring of heavy metals or water contaminants, with potential applications in field-deployable detection systems [14].

Future developments will likely focus on expanding the detectable ligand space through continued aTF engineering, enhancing biosensor orthogonality to minimize host interference, and improving operational stability under industrial conditions. As synthetic biology advances, TF-based biosensors will play an increasingly central role in creating intelligent microbial cell factories capable of self-regulated optimization and real-time adaptation to production conditions.

Whole-cell biosensors represent a powerful synthetic biology platform that integrates complete sensing, signal transduction, and reporting mechanisms within living cells. These biosensors leverage cellular machinery to detect specific analytes—from environmental contaminants to valuable metabolites—and convert this recognition into measurable signals [19]. The fundamental architecture consists of three core components: a sensing element that recognizes the target molecule, an intracellular signal transduction pathway that amplifies and processes the detection event, and a reporting element that generates a quantifiable output [19] [20]. Unlike purified enzyme-based detection systems, whole-cell biosensors offer self-replicating, cost-effective platforms that maintain homeostasis against environmental fluctuations, making them particularly suitable for high-throughput metabolite screening in industrial biotechnology and pharmaceutical development [19] [2].

The integration of these components creates a biosystem capable of autonomous function. When a target metabolite enters the cell, it interacts with the sensing element, triggering a conformational change that initiates signal transduction. This signal is processed through genetic circuits and ultimately activates expression of reporter genes, generating detectable outputs such as fluorescence, colorimetric changes, or gas production [19]. This seamless integration enables real-time monitoring of metabolic fluxes, pathway optimization, and compound screening directly in living systems, providing unprecedented insight into cellular biochemistry for drug development professionals and metabolic engineers [20].

Core Components and Operating Principles

Sensing Elements: Molecular Recognition Systems

Sensing elements serve as the molecular recognition foundation of whole-cell biosensors, providing specificity for target metabolites. The primary sensing modalities include:

Transcription Factors (TFs): These proteins bind to specific DNA promoter sequences and regulate transcription in response to target ligand binding. Natural TFs have been discovered for hundreds of compounds, while synthetic biology approaches enable engineering of TFs with novel specificities through truncation, chimerism, functional domain mutation, whole-protein mutation, and de novo design [19]. For example, researchers optimized the specificity of the CadR transcription factor for cadmium and mercury ions by truncating 10 and 21 amino acids from its C-terminal [19]. In another instance, the MphR transcription factor was subjected to saturated mutagenesis to create variants with increased specificity and sensitivity for macrolide antibiotics [19].

Riboswitches: These untranslated mRNA regions undergo conformational changes upon binding small molecules, thereby regulating translation by exposing or hiding ribosome binding sites [19]. Riboswitches offer an alternative recognition mechanism that operates at the RNA level without requiring protein synthesis.

Engineered Protein Scaffolds: Novel sensing interfaces can be created by fusing single-domain antibodies to monomer DNA binding domains, enabling the development of transcription factors for targets without natural recognition elements [19]. This de novo design approach significantly expands the range of detectable compounds.

Signal Transduction: Processing Molecular Information

Signal transduction mechanisms convert molecular recognition events into gene expression changes. In natural systems, ligand binding to transcription factors induces conformational changes that alter their affinity for operator sequences, thereby activating or repressing transcription [19]. Synthetic biology has expanded these natural paradigms through engineered genetic circuits that provide signal amplification, noise filtering, and logical processing:

Amplification Systems: Multi-stage transcriptional cascades can amplify weak signals, improving detection sensitivity for low-abundance metabolites [2].

Logic Gates: AND, OR, and NOT gates enable selective activation only when multiple metabolites are present or absent, increasing specificity in complex biological mixtures [19].

Feedback Loops: Positive feedback can create ultrasensitive responses, while negative feedback enables adaptation to background signals [2].

The TtgR-based biosensor exemplifies elegant signal transduction: flavonoid binding to the TtgR repressor causes its dissociation from the PttgABC promoter, derepressing transcription of downstream reporter genes [21]. This simple yet effective mechanism enables quantitative detection of bioactive compounds.

Reporting Elements: Generating Detectable Outputs

Reporting elements convert processed signals into measurable outputs compatible with high-throughput screening:

Fluorescent Proteins: The workhorses of biosensor reporting include GFP derivatives (CFP, YFP, RFP) and newer variants with improved brightness, photostability, and spectral properties [22] [20]. For instance, the eGFP reporter enables sensitive detection of flavonoids in TtgR-based systems [21].

FRET-Based Reporters: Förster resonance energy transfer between fluorescent protein pairs (e.g., CFP/YFP) creates rationetric sensors with internal calibration [23] [20]. Recent advances include chemogenetic FRET pairs with near-quantitative efficiency, such as the ChemoG series that combines fluorescent proteins with synthetic fluorophores bound to HaloTag [23].

Alternative Outputs: Gas production, colorimetric enzymes, and bioluminescent proteins offer additional detection modalities for various application contexts [19].

Performance Characteristics of Whole-Cell Biosensors

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Whole-Cell Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Sensing Element | Reporting Element | Dynamic Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Wild-type TtgR | eGFP | ~5-50 μM | ~5 μM | [21] |

| Resveratrol | TtgR N110F mutant | eGFP | Not specified | 10 μM (90% accuracy) | [21] |

| Quercetin | TtgR N110F mutant | eGFP | Not specified | 10 μM (90% accuracy) | [21] |

| Calcium ions | Calmodulin/M13 | FRET (CFP/YFP) | 130-400% FRET change | Not specified | [20] |

| ATP/NAD+ | Chemogenetic binders | FRET (ChemoG5-SiR) | >20-fold ratio change | Not specified | [23] |

| Macrolides | Engineered MphR | Fluorescence | Improved specificity | Not specified | [19] |

| Hg²⁺/Cd²⁺ | Truncated CadR | GFP | Specific for Cd²⁺/Hg²⁺ | Not specified | [19] |

Table 2: Fluorescent Protein Palette for Biosensor Design

| Fluorescent Protein | Excitation Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Relative Brightness | Applications | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eBFP2 | ~380 | ~448 | Low (~25% of EGFP) | FRET pairs, transcription reporting | UV excitation, phototoxic |

| Cerulean (CFP) | ~433 | ~475 | Moderate (~40% of EGFP) | FRET biosensors | Improved brightness vs ECFP |

| eGFP | ~488 | ~507 | High (reference) | General reporting | Standard, widely used |

| Venus (YFP) | ~515 | ~528 | High | FRET biosensors | Reduced environmental sensitivity |

| mKusabira Orange | ~548 | ~562 | Moderate | Multicolor imaging | Useful for multiplexing |

| mCherry (RFP) | ~587 | ~610 | Moderate | Multicolor imaging, deep tissue | Monomeric, improved folding |

| mScarlet | ~569 | ~594 | High | FRET pairs, multiplexed assays | Bright monomeric red protein |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Development of Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

This protocol outlines the construction and optimization of TF-based biosensors for metabolite detection, based on the TtgR-flavonoid system [21].

Materials:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) or DH5α competent cells

- Plasmid vectors (e.g., pCDF-Duet, pZnt-eGFP)

- Restriction enzymes (NdeI, NotI, BglII, XbaI)

- PfuTurbo DNA polymerase for site-directed mutagenesis

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Target metabolites (e.g., flavonoids, resveratrol) dissolved in DMSO

- Fluorescence plate reader or spectrometer

Procedure:

Genetic Construction of Biosensor

- Amplify the transcription factor gene (e.g., ttgR) and its native promoter/operator region (e.g., PttgABC) from source genomic DNA

- Clone the TF gene into an expression plasmid (e.g., pCDF-TtgR) using NdeI/NotI restriction sites

- Clone the promoter region upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., egfp) in a reporter plasmid (e.g., pTtg-eGFP) using BglII/XbaI sites

- Co-transform both plasmids into E. coli BL21 host cells

Engineering Enhanced Specificity (Optional)

- Identify key residues in the TF binding pocket through structural analysis or literature

- Perform site-directed mutagenesis to alter specificity (e.g., TtgR N110F mutant for resveratrol detection)

- Verify mutations by DNA sequencing

Biosensor Assay

- Inoculate overnight cultures of biosensor cells in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Dilute fresh LB medium to OD600 = 0.05 and grow at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm)

- At OD600 = 0.3, add target metabolites across desired concentration range (e.g., 0.005-5 mM)

- Incubate for 1-3 hours to allow full induction

- Measure fluorescence (excitation 480 nm, emission 510 nm for eGFP) and normalize to cell density (OD600)

- Calculate induction coefficient: (fluorescence with compound)/(fluorescence without compound)

Data Analysis

- Plot induction coefficient versus metabolite concentration to generate dose-response curves

- Determine dynamic range, sensitivity, and limit of detection

- Assess specificity by testing against structural analogs

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening Using Biosensor-Enabled FACS

This protocol enables screening of large microbial libraries for metabolite overproduction using biosensor-coupled fluorescence-activated cell sorting [2].

Materials:

- Microbial library (e.g., enzyme variant library, whole-cell mutant library)

- Metabolite-responsive biosensor cells

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS)

- Appropriate growth media

- Metabolite standards for calibration

Procedure:

Biosensor Calibration

- Generate a standard curve by measuring biosensor response to known metabolite concentrations

- Determine the linear range of detection and establish sorting gates

Library Screening

- Co-culture biosensor cells with library variants, or culture library variants to produce metabolites

- For extracellular detection, concentrate and process culture supernatants if necessary

- Incubate biosensor cells with library samples or co-culture directly

- Apply samples to FACS instrument with appropriate laser and filter settings for biosensor reporter

Cell Sorting and Recovery

- Set sorting gates to select variants that induce highest biosensor response (top 0.1-1%)

- Sort positive clones into recovery media or agar plates

- Culture sorted cells and validate metabolite production using analytical methods (HPLC, GC-MS)

Iterative Screening (Optional)

- Subject enriched populations to additional rounds of sorting for further improvement

- Isolate single clones from final sorted population for characterization

Visualization of Biosensor Architectures

Diagram 1: Whole-Cell Biosensor Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the complete signal transduction pathway from metabolite detection to reporter output.

Diagram 2: High-Throughput Screening Workflow. This workflow diagram outlines the iterative process for identifying microbial variants with improved metabolite production using whole-cell biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Whole-Cell Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chassis Organisms | E. coli BL21(DE3), E. coli DH5α, Pseudomonas putida | Host for biosensor construction and operation | Genetic tractability, growth characteristics, compatibility with target metabolites |

| Transcription Factors | TtgR, CadR, MerR, ZntR, MphR | Molecular recognition of target compounds | Specificity, sensitivity, dynamic range, engineering potential |

| Reporter Proteins | eGFP, mCherry, Luciferase, Gas-producing enzymes | Generation of detectable signals | Brightness, stability, detection compatibility, quantifiability |

| Plasmid Vectors | pCDF-Duet, pET series, pZA series | Genetic maintenance and expression of biosensor components | Copy number, compatibility, selection markers, expression control |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Labels | SiR, TMR, JF525, JF669 (for HaloTag) | Chemogenetic FRET acceptors, secondary detection | Cell permeability, photostability, spectral properties |

| Library Generation Tools | error-prone PCR kits, ARTP mutagenesis systems | Creation of diversity for biosensor or pathway engineering | Mutation rate, bias, efficiency, library size |

| Screening Equipment | FACS instruments, fluorescence plate readers | High-throughput measurement of biosensor response | Sensitivity, throughput, compatibility with output modality |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Whole-cell biosensors have evolved beyond simple detection devices to become sophisticated analytical tools for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Recent advances include:

Multiplexed Biosensing Systems: The development of color-tunable FRET pairs, such as the ChemoX series (ChemoB, ChemoC, ChemoG, ChemoY, ChemoR), enables simultaneous monitoring of multiple metabolites in a single cell [23]. This spectral multiplexing allows researchers to track complex metabolic networks and pathway interactions in real time.

Dynamic Range Engineering: Novel chemogenetic FRET pairs achieving near-quantitative FRET efficiencies (≥95%) significantly improve biosensor sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratios [23]. For example, the ChemoG5 variant combined with silicon rhodamine labeling demonstrates unprecedented dynamic ranges for ATP and NAD+ detection.

Integrated Bioprocessing Monitoring: Whole-cell biosensors are being incorporated into wearable devices such as masks, hand rings, and clothing for continuous environmental monitoring [19]. This technology translation demonstrates the robustness and practical applicability of these biosystems.

Future development directions include the creation of biosensors for previously undetectable metabolites, integration with machine learning for predictive analysis, and implementation in industrial bioprocessing for real-time fermentation control. As synthetic biology tools advance, whole-cell biosensors will play an increasingly central role in accelerating metabolic engineering cycles and pharmaceutical development pipelines.

Nucleic acid-based biosensors represent a powerful class of analytical tools that leverage the molecular recognition properties of DNA and RNA for detecting specific targets. These biosensors have gained significant traction in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology due to their high specificity, stability, and design flexibility [24]. Unlike protein-based sensors, nucleic acid biosensors can be quickly synthesized in vitro, easily engineered, and provide rapid response times by avoiding complicated protein-protein interactions [25]. This application note details the working principles, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks for three primary nucleic acid-based biosensors—aptamers, riboswitches, and toehold switches—within the context of high-throughput metabolite screening for drug development and metabolic engineering research.

The significance of these biosensors is underscored by their ability to address critical bottlenecks in metabolic engineering, particularly in screening large libraries of microbial variants. Conventional analytical methods like mass spectrometry or chromatography, while accurate, are time-consuming and low-throughput, creating a major bottleneck in identifying high-producing strains from libraries containing millions of variants [2]. Nucleic acid-based biosensors overcome this limitation by converting metabolite concentrations into measurable optical or electrochemical signals, enabling rapid screening and selection of optimal producers [26] [27].

Biosensor Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Working Principles and Mechanisms

Aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that fold into specific three-dimensional structures capable of binding to target molecules with high affinity and specificity. They are typically isolated from random sequence libraries through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [24]. Aptamers function as the recognition element in biosensors and can be coupled with various signal transduction mechanisms, including fluorescent, electrochemical, and colorimetric readouts.

Riboswitches are regulatory elements found in messenger RNA (mRNA) that modulate gene expression in response to ligand binding. A typical riboswitch consists of two functional domains: an aptamer domain (sensory region) that binds the target ligand, and an expression platform (regulatory region) that undergoes conformational changes upon ligand binding, thereby controlling transcription or translation [25]. These conformational changes can activate or repress gene expression by modulating access to the ribosome binding site (RBS) or forming transcription terminator structures.

Toehold switches are a class of engineered riboregulators that operate in trans. They consist of a switch sequence embedded in the 5' untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA that represses translation by sequestering the RBS and start codon in a hairpin structure. Upon binding to a specific trigger RNA sequence through strand displacement, the switch undergoes conformational changes that expose the RBS and initiate translation of the reporter gene [25]. This mechanism provides highly specific detection of RNA sequences and has been successfully deployed for diagnostic applications.

Comparative Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensor Platforms

| Feature | Aptamers | Riboswitches | Toehold Switches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Target-induced conformational change | cis-regulatory transcriptional/translational control | trans-activator triggered RBS exposure |

| Target Range | Metabolites, ions, proteins, cells [24] | Primarily small molecules and metabolites [25] | RNA sequences, including pathogen genomes [25] |

| Detection Limit | Variable (e.g., 100 nM for MOMS [28]) | ~10 μM for small molecules [28] | High specificity for RNA targets [25] |

| Throughput Capacity | >10⁷ cells/run (MOMS platform) [28] | Limited by host cell replication | Compatible with cell-free systems [25] |

| Key Advantages | High stability, design flexibility, various readout formats | Autonomous function in cells, no protein components needed | Programmable, high specificity, minimal cross-talk |

| Common Readouts | Fluorescence, electrochemistry, colorimetry [24] | GFP, RFP, other fluorescent proteins [29] | GFP, RFP, enzymatic reporters [25] |

| Screening Applications | Metabolite detection, strain screening [26] [28] | Dynamic pathway regulation, HTS [26] | Molecular diagnostics, pathogen detection [25] |

Biosensor Engineering and Implementation Protocols

Sensor Engineering and Optimization Strategies

Aptamer Integration into Functional Platforms: The MOMS (Molecular Sensors on the Membrane Surface of Mother Yeast Cells) platform demonstrates an advanced implementation of aptamer technology for high-throughput screening [28]. This system utilizes biotin-streptavidin conjugation to densely anchor DNA aptamers specifically to mother yeast cells, where they remain confined during cell division. The protocol involves:

- Cell surface biotinylation using membrane-impermeable sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin

- Streptavidin conjugation to biotinylated cell surfaces

- Attachment of biotin-labeled DNA aptamers specific to target metabolites

- Validation of sensor density and functionality via flow cytometry and confocal microscopy

This approach achieves a high-density sensor coating (1.4 × 10⁷ sensors/cell) that enables detection limits of 100 nM and screening throughput of over 10⁷ single yeast cells [28].

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor Engineering: When natural biosensors for specific metabolites are unavailable, transcription factors can be engineered through directed evolution. A protocol for developing a 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) biosensor exemplifies this approach [29]:

- Select a structurally similar transcription factor (AsnC for aspartate was used for 5-ALA)

- Perform saturation mutagenesis at key amino acid positions in the ligand-binding domain

- Screen mutant libraries using positive-negative alternative screening

- Couple evolved transcription factors with reporter genes (e.g., RFP)

- Validate biosensor specificity against structurally similar metabolites

This methodology successfully converted AsnC into a 5-ALA responsive transcription factor (mutant AC103-3H) capable of regulating RFP expression in response to 5-ALA concentration [29].

Riboswitch and Toehold Switch Optimization: Performance of RNA-based switches can be enhanced through:

- Systematic mutagenesis of aptamer domains to alter ligand specificity

- Engineering of ribosome binding site strength to modulate dynamic range

- Balancing switching efficiency and regulatory function [25]

High-Throughput Screening Implementation

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening Platform Comparison

| Screening Method | Throughput Capacity | Detection Limit | Key Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOMS | >10⁷ cells/run, 3.0×10³ cells/second | 100 nM | Yeast extracellular secretion analysis, vanillin production | [28] |

| FACS | ~10³-10⁴ cells/second | Variable (μM range) | Microbial library screening, enzyme evolution | [26] [2] |

| Droplet FADS | 10-200 cells/second | ~10 μM for most metabolites | α-amylase, lactate, ethanol detection | [28] |

| RAPID | Limited by encapsulation rate (~1-10%) | ~260 μM | Extracellular secretion measurement | [28] |

| Well-plate Assays | 10³-10⁴ variants | Variable | Targeted library screening, validation | [2] |

Experimental Protocols

MOMS Platform Implementation for Metabolite Detection

Materials:

- Yeast strain of interest

- Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Thermo Scientific)

- Streptavidin (New England Biolabs)

- Biotin-labeled DNA aptamers (Integrated DNA Technologies)

- Alexa Fluor 488-Concanavalin A (Thermo Fisher)

- Cy5-labeled aptamers (for validation)

- Flow cytometer or fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- Confocal laser scanning microscope

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation:

- Grow yeast cells to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6-0.8) in appropriate medium

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 5 minutes)

- Wash twice with PBS (pH 7.4)

Cell Surface Biotinylation:

- Resuspend cells at 2.0 × 10⁷ cells/mL in PBS

- Add sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin to final concentration of 1 mM

- Incubate at room temperature for 30 minutes with gentle mixing

- Quench reaction with 100 mM glycine for 10 minutes

- Wash three times with PBS to remove excess biotin

Streptavidin Conjugation:

- Resuspend biotinylated cells in PBS with 0.1 mg/mL streptavidin

- Incubate at room temperature for 20 minutes

- Wash three times with PBS to remove unbound streptavidin

Aptamer Immobilization:

- Incubate cells with biotin-labeled DNA aptamers (0.5-5 μM) for 30 minutes

- Wash cells to remove unbound aptamers

- Validate coating density using flow cytometry with Cy5-labeled aptamers

Functional Validation:

- Confirm sensor localization via confocal microscopy with Alexa Fluor 488-Concanavalin A counterstaining

- Assess cell viability (>90% expected) using fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining

- Perform calibration with known metabolite concentrations

High-Throughput Screening:

- Implement screening using flow cytometry at rates up to 3.0 × 10³ cells/second

- Sort cells based on fluorescence intensity corresponding to metabolite production

- Validate sorted populations using analytical methods (HPLC, LC-MS)

Toehold Switch Implementation for RNA Detection

Materials:

- DNA template for toehold switch and trigger RNA

- In vitro transcription kit (NEB)

- Cell-free protein expression system (PURExpress, NEB)

- Fluorescence plate reader

- Custom RNA synthesis service (if needed)

Procedure:

- Toehold Switch Design:

- Design switch sequence with complementary region to trigger RNA

- Incorporate ribosome binding site and start codon in hairpin structure

- Clone reporter gene (GFP, RFP) downstream of switch sequence

In Vitro Validation:

- Perform in vitro transcription to generate toehold switch RNA and trigger RNA

- Set up cell-free reactions containing toehold switch, ribosomes, and translation machinery

- Add varying concentrations of trigger RNA

- Monitor reporter protein expression via fluorescence over time

Specificity Testing:

- Test against non-cognate RNA sequences to verify minimal activation

- Evaluate detection limit with serial dilutions of trigger RNA

- Optimize switch sequence if cross-reactivity is observed

Cellular Implementation:

- Clone toehold switch construct into appropriate expression vector

- Transform into host organism (E. coli commonly used)

- Measure response to endogenous or exogenous trigger RNAs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensors

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin | Cell surface biotinylation for aptamer immobilization | MOMS platform fabrication | Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Streptavidin | Bridge between biotinylated surfaces and biotin-labeled aptamers | Aptamer sensor assembly | New England Biolabs, Sigma-Aldrich |

| DNA/RNA Aptamers | Molecular recognition elements | Metabolite detection, biosensor construction | Integrated DNA Technologies, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, RFP) | Reporter genes for biosensor output | Visualizing metabolite concentrations | Addgene, Clontech |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | In vitro characterization of RNA-based biosensors | Toehold switch validation | New England Biolabs (PURExpress) |

| SELEX Kit Systems | Aptamer selection against novel targets | Developing sensors for new metabolites | AMS Biotechnology, Base Pair Biotechnologies |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generators | High-throughput screening platform | FADS implementation | Dolomite Microfluidics, Bio-Rad |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorters | High-throughput screening and sorting | Library screening, producer strain isolation | BD Biosciences, Beckman Coulter |

Visualizing Biosensor Workflows and Mechanisms

MOMS Platform Fabrication and Screening Workflow

Riboswitch and Toehold Switch Operational Mechanisms

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Diagnostics

Nucleic acid-based biosensors have demonstrated remarkable success in various applications, particularly in metabolic engineering and molecular diagnostics. In metabolic engineering, biosensor-driven high-throughput screening has enabled significant improvements in product titers. For instance, a transcription factor-based biosensor for p-coumaric acid was used to develop an Escherichia coli strain producing 9.61 g/L of caffeic acid—the highest reported titer to date [26]. Similarly, the MOMS platform identified yeast strains with 2.7-fold higher vanillin production compared to parental strains [28].

In molecular diagnostics, toehold switches have been successfully deployed for detecting pathogenic viruses such as Ebola and Zika with high accuracy and specificity [25]. Their integration with cell-free systems and paper-based platforms has facilitated the development of point-of-care diagnostic devices that meet the WHO ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and Robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable) [25].

The future development of nucleic acid-based biosensors will likely focus on expanding the repertoire of detectable metabolites, improving sensitivity and dynamic range, and integrating with emerging technologies such as machine learning and cell-free systems. These advancements will further enhance their utility in high-throughput screening programs for drug development and metabolic engineering.

In high-throughput metabolite screening research, the performance of a biosensor directly dictates the quality and reliability of the data generated. Achieving high-throughput analysis requires biosensors that are not only fast but also exceptionally reliable, providing accurate quantitative data over a wide range of metabolite concentrations. This document details the core performance metrics—Sensitivity, Specificity, Dynamic Range, and OFF/ON States—that are critical for the development and validation of biosensors in this demanding context. The application notes and standardized protocols that follow provide a framework for researchers to quantitatively assess and optimize these parameters, ensuring that biosensor platforms meet the rigorous demands of drug development and metabolic engineering.

Defining the Key Performance Metrics

Sensitivity

Sensitivity refers to the smallest change in target analyte concentration that a biosensor can reliably distinguish. In the context of metabolite screening, high sensitivity is paramount for detecting low-abundance metabolites that may be pharmacologically relevant. Sensitivity is often quantified as the Limit of Detection (LoD), which is the lowest concentration that can be statistically differentiated from a blank sample. For quantitative sensors, the dose-response slope is also a key indicator, where a steeper slope signifies a more sensitive biosensor. A recent study on a nanostructured glucose sensor demonstrated exceptionally high sensitivity of 95.12 ± 2.54 µA mM−1 cm−², which is crucial for detecting subtle fluctuations in metabolite levels [30].

Specificity

Specificity defines a biosensor's ability to respond exclusively to its intended target metabolite while ignoring structurally similar compounds or other components in a complex biological sample. This is primarily determined by the biorecognition element (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer, or transcription factor). For example, a biosensor engineered for the metabolite l-carnitine was specifically designed around the transcription factor CaiF, which is naturally activated by an intermediate in the carnitine metabolic pathway. The specificity of such a system can be enhanced through computer-aided design and mutagenesis of the binding site to minimize off-target interactions [31].

Dynamic Range

The Dynamic Range is the span of analyte concentrations over which a biosensor provides a usable quantitative signal. A wide dynamic range is essential for high-throughput screening, as metabolite concentrations in biological systems can vary by several orders of magnitude. The useful dynamic range is typically defined as the concentration interval between the lower limit of detection and the saturation point where the signal no longer increases. A classic limitation of single-site binding is its relatively narrow ~81-fold dynamic range [32]. Advanced engineering strategies, such as combining multiple receptor variants with different affinities, can dramatically extend this range. For instance, one study created a biosensor with a log-linear dynamic range spanning nearly 900,000-fold, far exceeding the capacity of a single receptor [32].

OFF/ON States and Signal-to-Noise

The OFF-state (basal signal) and ON-state (saturated signal) are fundamental to defining a biosensor's performance. The OFF-state output should be minimized to reduce background noise, while the ON-state should be maximized for a strong, easily detectable signal. The ratio of the ON-state to the OFF-state signal is the Dynamic Range (or Signal-to-Noise Ratio), a critical figure of merit. A high dynamic range allows for confident identification of "hits" in a screening assay. In the optimization of a protocatechuic acid (PCA) biosensor, researchers achieved an ON/OFF ratio of 417, which was later improved to over 500-fold through systematic engineering [33].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics and Their Definitions in Metabolite Screening

| Metric | Definition | Significance in High-Throughput Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (LoD) | Lowest detectable concentration difference | Enables detection of low-abundance metabolites; reduces false negatives. |

| Specificity | Ability to distinguish target from interferents | Ensures accurate identification in complex mixtures; reduces false positives. |

| Dynamic Range | Concentration span from detection limit to saturation | Allows quantification across diverse cellular states without sample dilution. |

| OFF/ON Ratio | Ratio of saturated signal to basal signal | Determines the assay's signal window and robustness for automated screening. |

Application Notes: Quantifying Metrics in Metabolite Biosensors

Case Study: Optimizing a Protocatechuic Acid (PCA) Biosensor

This case study highlights the systematic optimization of a whole-cell biosensor for PCA, a lignin-derived metabolite, using a Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology [33]. The goal was to enhance performance for applications in metabolic engineering and screening.

- Experimental System: The biosensor consisted of the PCA-responsive transcription factor PcaV and its cognate promoter controlling the expression of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene on a single plasmid in E. coli.

- Performance Pre-Optimization: The initial single-plasmid biosensor showed a dynamic range (ON/OFF) of 417, but with only modest GFP expression levels [33].

- Optimization Strategy: A Definitive Screening Design (DSD) was employed to systematically vary three key genetic components: the promoter strength controlling pcaV expression (Preg), the promoter strength controlling gfp expression (Pout), and the ribosome binding site (RBS) strength for gfp (RBSout). This structured approach efficiently mapped the multidimensional experimental space with a minimal number of experiments.

- Quantitative Outcomes: The DoE approach led to dramatic improvements in biosensor performance, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Performance Enhancement of a PCA Biosensor via DoE [33]

| Construct/Variant | OFF-State (A.U.) | ON-State (A.U.) | Dynamic Range (ON/OFF) | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Design | Not Specified | Not Specified | 417 | Baseline performance |

| Variant pD3 | 28.9 ± 0.7 | 45.7 ± 4.7 | 1.6 ± 0.16 | Very low background, low output |

| Variant pD5 | 1543.3 ± 46.2 | 5546.2 ± 101.7 | 3.6 ± 0.11 | High background, low range |

| Optimized Variant (pD2) | 397.9 ± 3.4 | 62,070.6 ± 1042.1 | 156.0 ± 1.5 | Balanced, high-output, wide dynamic range |

| Post-Optimization Capability | --- | --- | >500-fold | Maximum dynamic range achieved |

| >1500-fold | Increase in sensitivity achieved |

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Biosensor Dose-Response

Objective: To generate a dose-response curve for determining the sensitivity, dynamic range, and OFF/ON states of a metabolite biosensor.

Materials:

- Biosensor strain (e.g., recombinant E. coli with metabolite-responsive GFP).

- Target metabolite stock solution (e.g., PCA, l-carnitine, ferulic acid).

- Culture medium (e.g., LB, M9 minimal medium).

- Microplate reader (capable of fluorescence and OD measurements).

- 96-well or 384-well black-walled, clear-bottom microplates.

- Plate shaker/incubator.

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Inoculate the biosensor strain into medium and grow overnight to saturation.

- Dilution: Sub-culture the overnight culture into fresh medium to a standardized low OD600 (e.g., 0.05).

- Dosing: Aliquot the diluted culture into a microplate. Add the target metabolite to each well, creating a concentration series spanning at least 6-8 orders of magnitude (e.g., from 1 nM to 100 mM). Include control wells without metabolite (for OFF-state) and with a saturating metabolite concentration (for ON-state). Each condition should be performed with a minimum of n=3 technical replicates.

- Incubation and Measurement: Seal the plate and incubate with shaking at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C). Periodically monitor both OD600 (biomass) and GFP fluorescence (signal) until the biosensor response reaches a plateau, typically in the mid-to-late exponential growth phase.

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize the GFP fluorescence signal of each well to its OD600 value to calculate the specific signal (e.g., A.U./OD600).

- Average the replicate values for each metabolite concentration.

- Plot the normalized signal (y-axis) against the logarithm of the metabolite concentration (x-axis).

- Fit the data with a four-parameter logistic (4PL) sigmoidal curve.

- Calculate Metrics:

- OFF-state: Mean signal from the zero-metabolite control.

- ON-state: Mean signal from the saturating metabolite concentration.

- Dynamic Range: ON-state / OFF-state.

- Sensitivity (EC50): The metabolite concentration that yields a half-maximal signal, derived from the 4PL curve fit.

- Linear Range: The concentration range between approximately 10% and 90% of the maximal response.

Advanced Engineering: Expanding Dynamic Range

The intrinsic dynamic range of a single bioreceptor is limited. Advanced protein and genetic engineering strategies can overcome this barrier, which is crucial for screening pathways where metabolite titers can vary dramatically.

Strategy: Combining Receptor Variants

A foundational strategy involves engineering a set of receptor variants that retain specificity but span a wide range of affinities for the target. These variants are then combined in a single assay to create a composite biosensor with an extended dynamic range [32].

- Mechanism: By mixing, for example, a high-affinity receptor (sensitive to low concentrations) with a low-affinity receptor (sensitive to high concentrations) in optimized ratios, the overall response curve is effectively "stitched together." This approach has been successfully used to create biosensors with a log-linear dynamic range of over 900,000-fold [32].

- Application to Metabolite Screening: This is particularly valuable for screening mutant libraries in metabolic engineering, where production yields of a target metabolite can range from undetectable to several grams per liter.

Case Study: Engineering anl-Carnitine Biosensor

To address a limited detection range in a biosensor for the metabolite l-carnitine, researchers employed a Functional Diversity-Oriented Volume-Conservative Substitution Strategy on the key residues of the transcription factor CaiF [31].

- Method: Computer-aided design was used to model the CaiF structure and its DNA binding site. Key residues were identified and subjected to saturation mutagenesis.

- Result: A specific variant, CaiF-Y47W/R89A, was isolated. This engineered biosensor exhibited a dramatically expanded concentration response range from 10⁻⁴ mM to 10 mM, which is 1000-fold wider than the control biosensor, along with a 3.3-fold higher output signal intensity [31]. This performance is ideal for monitoring and optimizing l-carnitine production in fermentation processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development and Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Allosteric Transcription Factors (aTFs) | Biorecognition element; binds metabolite and regulates transcription. | PcaV for protocatechuic acid detection [33]; CaiF for l-carnitine [31]. |

| Constitutive Promoter Libraries | Provides a tunable range of expression levels for biosensor components. | Systematic optimization of transcription factor expression to tune biosensor performance [33]. |

| RBS Libraries | Provides a tunable range of translation initiation rates. | Fine-tuning the expression level of the reporter protein (e.g., GFP) independent of transcription [33]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP) | Generates a quantifiable signal upon metabolite detection. | Standard reporter for quantifying biosensor OFF/ON states and dynamic range in high-throughput plates [33]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Magnetic labels for biosensor signal transduction. | Used in magnetoresistive (MR)-based biosensors for highly sensitive, label-free detection [34]. |

| Nanostructured Materials (e.g., porous Au, graphene) | Enhances electrode surface area and electron transfer. | Used in electrochemical biosensors (e.g., glucose sensor) to achieve high sensitivity and low LoD [30] [35]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Algorithms | Models nonlinear relationships between fabrication parameters and sensor response. | Predicting optimal biosensor fabrication conditions (e.g., enzyme loading, pH) to reduce experimental burden [35]. |

The rigorous characterization and optimization of sensitivity, specificity, dynamic range, and OFF/ON states are non-negotiable steps in developing biosensors fit for purpose in high-throughput metabolite screening. The protocols and engineering strategies outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to systematically enhance these metrics. As the field advances, the integration of computational design, machine learning, and novel nanomaterials will continue to push the boundaries of biosensor performance, thereby accelerating discovery in drug development and synthetic biology.

High-Throughput Screening Platforms and Real-World Applications

In the field of biosensor development for high-throughput metabolite screening, selecting the appropriate screening modality is a critical determinant of success. The journey from a genetically encoded biosensor to a validated tool for discovering high-producing microbial strains relies on the effective interrogation of vast libraries. This article details the core methodologies of well plates, agar plates, and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), providing a comparative analysis and detailed protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in applying these techniques within a metabolic engineering workflow. These platforms enable the screening and sorting of libraries ranging from thousands to billions of variants, directly impacting the efficiency of optimizing biosynthetic pathways for metabolite production [2].

Comparative Analysis of Screening Platforms

The choice between well plates, agar plates, and FACS is guided by the required throughput, the sensitivity of the biosensor, and the available resources. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these three primary screening modalities.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of High-Throughput Screening Modalities

| Screening Modality | Approximate Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well Plates | (10^2) - (10^3) variants per run [2] | Quantitative data, multiple parameter measurement, controlled assay conditions. | Lower throughput, labor-intensive and time-consuming liquid handling. | Validation of biosensor function, small library screening, dose-response assays [2] [36]. |

| Agar Plates | (10^3) - (10^5) colonies per plate [2] | Very low cost, simple setup, no specialized equipment needed, visual screening. | Semi-quantitative at best, limited control over microenvironment, potential for cross-contamination. | Initial library enrichment, blue-white screening, visual screening with fluorescent/colorimetric biosensors [2] [29]. |

| FACS-Based Sorting | >(10^7) cells per hour [2] [28] | Ultra-high-throughput, quantitative, single-cell resolution, can sort live cells. | Requires biosensor signal to be detectable at high speed, high equipment cost, potential for sheath fluid waste. | Screening of large, diverse genomic or mutant libraries for metabolite production using fluorescent biosensors [2] [37]. |

Detailed Protocols and Applications

Well Plate-Based Screening

Well plate screening is a workhorse for quantitative assessment of biosensor performance and metabolite production in a controlled, multi-parameter format. It is ideal for validating hits from higher-throughput methods or screening smaller, focused libraries.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Well Plate and Agar Plate Screening

| Research Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| HepaRG Cells | Differentiated human hepatoma cell line; used in 96-well HTS platforms for toxicological metabolomics studies [36]. |

| PUREfrex2.0 System | A reconstituted in vitro transcription/translation (IVTT) system; used for high-yield cell-free expression of biosensor proteins in microfluidic droplets [8]. |

| Ehrlich's Reagent | A chemical reagent that reacts with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) to produce a distinctive color change; used in traditional, low-throughput colorimetric assays [29]. |

| Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin | A cell-impermeable biotinylating reagent; used to label surface proteins of yeast cells for subsequent attachment of streptavidin-linked molecular sensors [28]. |

| CdCl₂ (Cadmium Chloride) | A model toxicant; used in proof-of-principle studies to induce metabolome changes in HepaRG cells and validate HTS metabolomics workflows [36]. |