13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), a cornerstone technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), a cornerstone technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of isotopic tracing and metabolic steady-state assumptions. The scope extends to detailed, high-resolution protocols for experimental design, sample preparation, and data analysis using modern software platforms. It further addresses critical steps for troubleshooting, model optimization, and statistical validation to ensure robust and reproducible flux estimates. By synthesizing established best practices with recent methodological advances, this guide aims to empower the application of 13C-MFA in diverse areas, including metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and the investigation of disease mechanisms in cancer and neurodegeneration.

Understanding 13C-MFA: Core Principles and Its Role in Quantitative Systems Biology

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), particularly 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), has emerged as a cornerstone technique in systems biology for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activities. By leveraging stable isotope tracers and sophisticated computational models, 13C-MFA provides an unparalleled capacity to elucidate the functional metabolic phenotype of cells, bridging the gap between genetic potential and observed physiological function. This application note delineates the core principles, detailed protocols, and unique capabilities of 13C-MFA, underscoring its transformative role in phenotyping across diverse fields from metabolic engineering to disease mechanism research [1] [2] [3].

Metabolic flux, defined as the in vivo conversion rate of metabolites through biochemical pathways, represents the ultimate functional output of cellular regulation. Understanding these fluxes is crucial for revealing the sites and mechanisms of metabolic regulation and how cells balance growth with maintenance under varying environmental conditions [1]. While genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics describe the hierarchical blueprint of cellular potential, it is fluxomics—the quantitative analysis of metabolic fluxes—that characterizes the integrated metabolic phenotype. 13C-MFA stands as the most powerful and widely applied method in fluxomics, enabling the precise quantification of absolute flux values throughout central carbon metabolism [2] [4].

Core Principles and Classifications of Fluxomics

13C-based fluxomics has evolved into a diverse family of methods, each suited to specific experimental scenarios and system constraints [1].

Classification of 13C Metabolic Fluxomics Methods

Table 1: Classification and characteristics of major 13C metabolic fluxomics methods.

| Method Type | Applicable Scenario | Computational Complexity | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) | Any system | Easy | Provides only local, qualitative flux information [1] |

| Metabolic Flux Ratios Analysis | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are constant | Medium | Provides only local, relative quantitative values [1] |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | Systems where fluxes and metabolites are constant but labeling is variable | Medium | Limited to local fluxes and relative quantification [1] |

| Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and their labeling are constant | Medium | Not applicable to dynamic systems [1] [2] |

| Isotopically Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems where fluxes and metabolites are constant but labeling is variable | High | Not applicable to metabolically dynamic systems [1] [2] |

| Metabolically Instationary 13C-MFA | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are all variable | Very High | Experimentally and computationally challenging [1] |

The fundamental principle underlying 13C-MFA is that the distribution of 13C labels from a labeled substrate into intracellular metabolites is uniquely determined by the activities of the metabolic pathways. By measuring these labeling patterns, one can infer the underlying metabolic flux distribution [4]. The process can be formalized as an optimization problem where flux values (v) are estimated by minimizing the difference between experimentally measured isotope labeling patterns (xM) and model-simulated patterns (x), subject to stoichiometric constraints (S·v = 0) and other physiological bounds [1].

The 13C-MFA Workflow: A Detailed Protocol

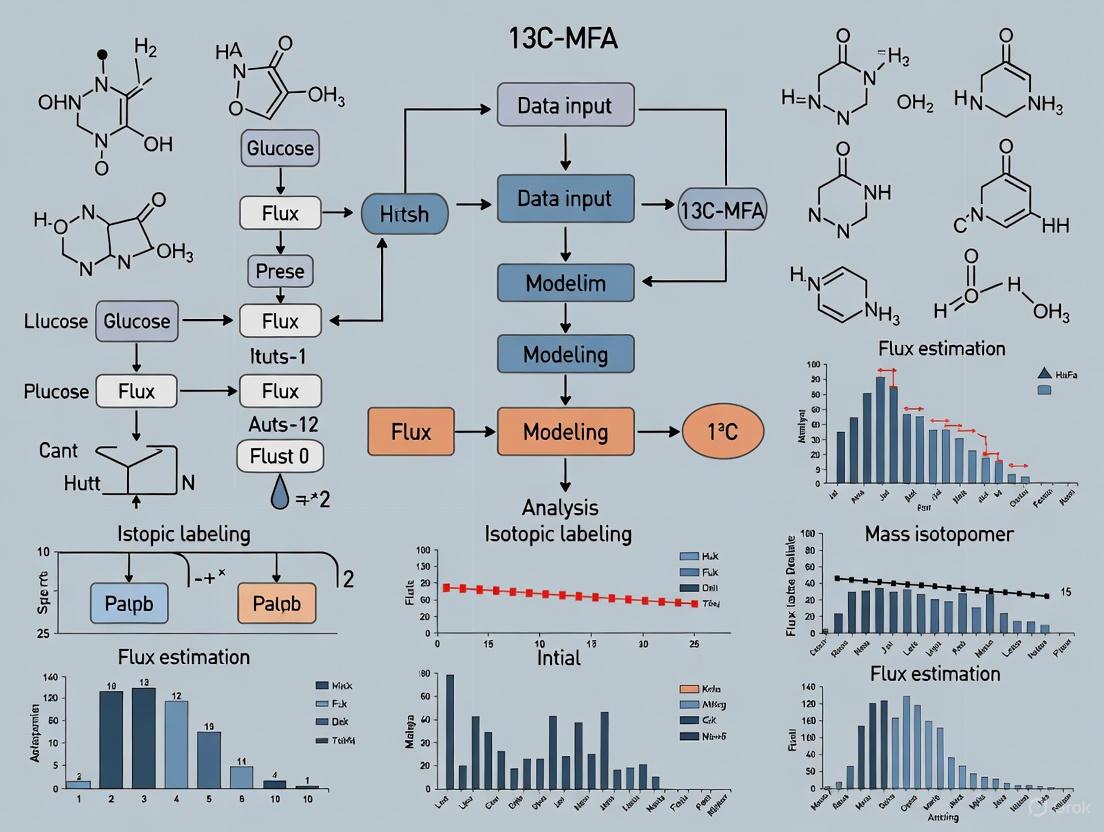

The execution of 13C-MFA involves a series of critical steps, from experimental design to statistical validation [2] [4]. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow.

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

The first and most critical step is the selection of an appropriate 13C-labeled tracer. The choice depends on the biological question, the organism under study, and the specific pathways of interest [4].

- Common Tracers: Glucose is the most common carbon source, used in various labeling patterns such as [1-13C], [1,2-13C], or uniformly labeled [U-13C] glucose. The use of doubly labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C] glucose) is recommended as it significantly improves the accuracy of flux estimation compared to single labels [4].

- Experimental Setup: To ensure metabolic steady state (constant metabolic fluxes) and isotopic steady state (static isotope incorporation), cells are cultured for an extended period—often more than five residence times—in a medium containing the chosen tracer. This can be achieved through prolonged incubation in bioreactors or controlled batch cultures where the cell growth rate is constant [2] [4].

Sample Collection, Quenching, and Metabolite Extraction

Once isotopic steady state is reached, metabolism is rapidly quenched, typically using cold methanol, to instantly halt all enzymatic activity and preserve the in vivo labeling patterns. Intracellular metabolites are then extracted using solvent systems like methanol/water or chloroform/methanol. This process must be optimized for completeness and reproducibility to ensure accurate flux determination [2].

Isotopic Labeling Measurement

The isotopic enrichment of extracted metabolites is measured using analytical techniques, primarily Mass Spectrometry (MS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [1] [2].

- Gas Chromatography-MS (GC-MS): This is the most widely used technique due to its high sensitivity, precision, and ability to separate a broad range of metabolites. It provides mass isotopomer distribution data essential for flux calculation [2] [4].

- Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS/MS): Excellent for analyzing less volatile compounds and can provide superior separation for complex metabolite mixtures [4].

- NMR Spectroscopy: While generally less sensitive than MS, NMR offers the unique advantage of providing positional labeling information for atoms within a molecule, which can greatly enhance flux resolution [2].

Flux Estimation and Computational Modeling

This is the computational core of 13C-MFA. The goal is to find the set of metabolic fluxes that best fits the experimentally measured isotope labeling patterns. This involves [1] [4]:

- Constructing a Stoichiometric Model: A network model encompassing the major metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle) is built.

- Simulating Labeling Patterns: The model simulates the isotopic labeling of metabolites for a given set of trial fluxes.

- Non-Linear Regression: An optimization algorithm iteratively adjusts the flux values to minimize the difference (residual sum of squares, SSR) between the simulated and measured labeling data.

Software tools like INCA, OpenFLUX, and Metran that utilize the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework have dramatically reduced the computational burden of this process [2] [4].

Statistical Analysis and Validation

The reliability of the estimated flux map must be rigorously assessed [4].

- Goodness-of-Fit: The minimized SSR is evaluated using χ² statistics to determine if the model adequately fits the data.

- Confidence Intervals: Sensitivity analysis or Monte Carlo simulations are performed to quantify the uncertainty and establish confidence intervals for each estimated flux. A flux is considered well-resolved if its confidence interval is within ±5-10% of the estimated value [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for 13C-MFA experiments.

| Item | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Carbon source for flux tracing; enables tracking of metabolic pathways. | [1,2-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glucose, 13C-Glutamine. Using mixtures of tracers can enhance flux resolution [2] [4]. |

| Cell Culture System | Provides a controlled environment for maintaining metabolic and isotopic steady state. | Bioreactors, chemostats, or well-controlled batch cultures [4]. |

| Quenching Solution | Instantly halts metabolic activity to preserve in vivo flux states. | Cold methanol or buffered aqueous methanol solutions [2]. |

| Extraction Solvents | Liberates intracellular metabolites for analysis. | Methanol/water, chloroform/methanol/water mixtures [2]. |

| Analytical Instrumentation | Measures the isotopic labeling patterns of metabolites. | GC-MS (most common), LC-MS/MS, NMR Spectroscopy [2] [4]. |

| Computational Software | Performs flux estimation by fitting models to experimental data. | INCA, OpenFLUX, Metran (often based on the EMU framework) [2] [4]. |

Unique Phenotyping Power and Applications

13C-MFA provides a dynamic, functional readout that static 'omics' data cannot, making it uniquely powerful for phenotyping.

- Revealing Pathway Activity: It can identify relative contributions of parallel pathways (e.g., glycolysis vs. pentose phosphate pathway), quantify flux through reversible reactions, and uncover the activity of redundant or cyclic pathways like the TCA cycle [1] [4].

- Metabolic Engineering: 13C-MFA is the "gold standard" for quantifying fluxes in living cells, guiding the rational redesign of metabolic networks in industrial microbes to optimize the production of target compounds like biofuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals [1] [2] [4].

- Disease Mechanism Research: The technique is instrumental in characterizing the metabolic reprogramming associated with diseases. It has been used to reveal flux alterations in cancer (e.g., colorectal adenocarcinomas), diabetes, retinal degenerative diseases, and immune cell activation, thereby identifying potential therapeutic targets [1] [3].

- Drug Discovery and Pharmacology: 13C-MFA helps elucidate the mechanisms of drug action and the emergence of drug resistance by characterizing changes in metabolic flux profiles in response to treatment [3].

The following diagram conceptualizes how 13C-MFA integrates data to reveal the functional metabolic phenotype, which is invisible to other analytical layers.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a powerful technique for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity in various biological systems, from microbes to mammalian cells [1]. It is considered the gold standard for quantifying the fluxes (conversion rates) of metabolites within living cells, providing a dynamic picture of metabolic phenotype that goes beyond static metabolomic measurements [4] [5]. The fundamental principle underpinning 13C-MFA is the systematic tracing of 13C-labeled atoms from specific substrates as they propagate through complex metabolic networks. The resulting isotopic patterns in intracellular metabolites are a rich source of information that, when interpreted through mathematical models, reveals the absolute in vivo fluxes of enzymatic reactions [1] [6].

This capability is crucial for understanding cellular physiology in both health and disease. In cancer biology, for instance, 13C-MFA has been instrumental in uncovering how cancer cells rewire their metabolism to support rapid proliferation, a phenomenon that extends beyond the classic Warburg effect to include pathways like reductive glutamine metabolism and serine/glycine biosynthesis [6]. The technique plays an important role in revealing patho-physiological mechanisms, identifying changes in metabolic pathway activity, and discovering novel metabolic pathways [1]. Furthermore, 13C-MFA is widely used in metabolic engineering to guide the optimization of target product synthesis, such as biofuels and pharmaceuticals [1] [4].

Fundamental Principles

Core Concept: From Labeling Patterns to Metabolic Fluxes

At its core, 13C-MFA is based on a straightforward but powerful concept: when a 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., glucose or glutamine) is introduced to a biological system and metabolized, the enzymatic reactions rearrange the carbon atoms, leading to specific isotope labeling patterns in downstream metabolites [6]. These patterns are highly sensitive to the relative fluxes of different pathways. For example, different flux distributions at a metabolic branch point will result in distinctly different isotopic enrichments in the products [4].

The relationship between the substrate's labeling state and the resulting intracellular labeling patterns is governed by the topology of the metabolic network and the specific atom transitions in each enzymatic reaction [1]. This relationship can be described mathematically. The flux estimation process in 13C-MFA is formalized as an optimization problem, where the goal is to find the set of fluxes that minimizes the difference between the experimentally measured isotope labeling patterns and those simulated by the model [1]. The general optimization problem can be represented as:

Where v is the vector of metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is the vector of simulated isotope-labeled molecules, and x_M is the corresponding experimental measurement [1].

The Role of the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) Framework

A key breakthrough in 13C-MFA was the development of the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework, which allows for efficient simulation of isotopic labeling in large, complex biochemical networks [6] [7]. The EMU framework decomposes the complex problem of simulating isotope distributions by breaking down metabolites into smaller, manageable fragments ("EMUs") [7]. This framework significantly reduces the computational complexity of flux estimation and has been incorporated into user-friendly software tools like Metran and INCA, making 13C-MFA accessible to a broader scientific audience [6].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of 13C-MFA, integrating both experimental and computational phases:

Experimental Protocols

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The first critical step in any 13C-MFA study is the careful selection of an appropriate 13C-labeled tracer. The choice of tracer depends on the biological question, the cell type under investigation, and the specific metabolic pathways of interest [6] [4].

- Common Tracers: Early 13C-MFA approaches often used various mixtures of [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, and unlabeled glucose as substrates [1]. Currently, double-labeled substrates such as [1,2-13C]glucose are recommended because they can significantly improve the accuracy of flux estimation by providing more informative labeling patterns, despite their higher cost (~$600/g) [4].

- Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs): To further enhance flux resolution, the COMPLETE MFA approach employing multiple, complementary tracers in parallel experiments has been developed. For example, using all six singly labeled glucose tracers for E. coli flux analysis has resulted in the most accurate and precise flux parameters obtained to date [8]. This approach leverages the synergy of complementary information to resolve fluxes across different parts of the metabolic network [8].

Cell Culture and Sampling under Metabolic Steady State

A fundamental requirement for traditional 13C-MFA is that the system must be at metabolic and isotopic steady state [4]. This means that both the metabolic flux values and the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites are constant over time.

- Culture Conditions: Cells are cultured with the chosen 13C-labeled substrate as the carbon source. For microbial systems, this is often done in controlled bioreactors (chemostat or fed-batch), while mammalian cells are typically grown in T-flasks or bioreactors [6].

- Achieving Isotopic Steady State: The incubation time must be sufficient to ensure the system reaches an isotopic steady state. A common guideline is to extend the incubation for more than five residence times (the time required to replace the entire metabolite pool) [4]. For exponentially growing cells, this often means harvesting during the mid-exponential growth phase when the growth rate is constant.

- Sampling: Samples are collected for the measurement of extracellular rates (see below) and for the analysis of isotopic labeling in intracellular metabolites. Sampling typically involves rapid quenching of metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol), extraction of intracellular metabolites, and preparation for analysis by GC-MS or LC-MS [6].

Measurement of External Rates and Isotopic Labeling

Quantifying the cross-talk between the cells and their environment is essential for constraining the metabolic model.

- External Rates: This involves measuring the uptake rates of nutrients (e.g., glucose, glutamine) and the secretion rates of metabolic by-products (e.g., lactate, ammonium). The growth rate of the cells must also be determined precisely [6]. For exponentially growing cells, the growth rate (µ) is determined from the change in cell number over time. The external rate of a metabolite

i(r_i, in nmol/10^6 cells/h) can be calculated as:r_i = 1000 · (µ · V · ΔC_i) / ΔN_xwhereΔC_iis the change in concentration (mmol/L),ΔN_xis the change in cell number (millions), andVis the culture volume (mL) [6]. - Isotopic Labeling Measurement: The isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites, such as amino acids or organic acids, is measured using Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS, LC-MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [1] [6]. GC-MS is the most commonly used method due to its high sensitivity and precision [4]. Tandem MS (MS/MS) and LC-MS/MS are also employed to improve the resolution of complex metabolite spectra [4] [8].

Table 1: Key Analytical Techniques for Isotopic Labeling Measurement

| Technique | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | High sensitivity, high precision, requires derivatization | Analysis of amino acids, organic acids |

| LC-MS/MS | Excellent for liquid samples, high separation ability | Analysis of complex metabolite spectra without derivatization |

| NMR | Provides structural information, non-destructive | Global metabolic information, positional isotopomer analysis |

Computational Flux Estimation and Statistical Validation

The computational phase translates the experimental data into a quantitative flux map.

- Flux Estimation: The measured extracellular fluxes and isotopic labeling data are integrated into a stoichiometric metabolic model. Using computational tools like OpenFLUX2, INCA, or 13CFLUX2, the intracellular fluxes are estimated by solving a non-linear least-squares optimization problem [8]. The algorithm iteratively adjusts the flux values in the model until the simulated labeling patterns best fit the experimental data [1] [6].

- Statistical Validation: After flux estimation, rigorous statistical analysis is required to validate the results.

- Goodness-of-fit: This is typically evaluated using the residual sum of squares (SSR), which should conform to a χ² distribution. A poor fit may indicate an incomplete metabolic model or low-quality data [4].

- Confidence Intervals: The precision of the estimated fluxes is assessed by calculating confidence intervals, often through sensitivity analysis or Monte Carlo simulation [4] [8].

Application Note: Metabolic Shift During Erythroid Differentiation

A recent study demonstrated the power of 13C-MFA to uncover metabolic shifts during cellular differentiation [9] [10]. The research aimed to understand the metabolic changes in K562 cells (a model cell line) before and after differentiation into erythroid cells (red blood cell precursors), a process critical for regenerative medicine.

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Culture and Differentiation: K562 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium and differentiated into erythroid cells by treatment with 1 mM sodium butyrate for four days. Successful differentiation was confirmed by a color change (red due to hemoglobin synthesis) and flow cytometry for surface markers CD71 and CD235a [10].

- 13C-Tracer Experiment: Both undifferentiated and differentiated cells were cultured with a 13C-labeled substrate (the specific tracer is not mentioned in the abstract, but [U-13C]glucose is a common choice).

- Flux Analysis: 13C-MFA was performed to quantify the fluxes in central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the TCA cycle.

Key Findings: The 13C-MFA results revealed a significant metabolic reprogramming upon differentiation:

- Decreased Glycolytic Flux: Differentiated cells showed a reduction in the flow of carbon through glycolysis.

- Increased TCA Cycle Flux: The flux through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle was enhanced, indicating a shift towards oxidative metabolism [9] [10].

This flux-level insight provided a mechanistic understanding of the energy metabolism supporting erythroid differentiation. Furthermore, based on this finding, the researchers inhibited ATP synthase with oligomycin and found that it significantly suppressed K562 differentiation, functionally validating that the activation of oxidative metabolism is required for proper differentiation [9].

The metabolic shift observed in this study can be visualized as a change in flux distribution through the central metabolic network:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of 13C-MFA relies on a combination of specialized reagents, analytical instrumentation, and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for 13C-MFA

| Category | Item | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose | Provides complementary labeling information to resolve fluxes in pentose phosphate pathway, glycolysis, and TCA cycle [4]. |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer; useful for probing overall network activity and for parallel labeling experiments (PLEs) [8]. | |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS System | Workhorse for measuring isotopic labeling of amino acids and organic acids with high precision after derivatization [4]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Used for analysis of a broader range of metabolites without derivatization; provides high sensitivity and resolution [4]. | |

| Software & Modeling | OpenFLUX2 | Open-source software for 13C-MFA, adjusted for comprehensive analysis of both single and parallel labeling experiments [8]. |

| INCA / Metran | User-friendly software tools incorporating the EMU framework, facilitating flux estimation for non-experts [6]. | |

| FluxML | A universal modeling language to unambiguously express and conserve all information for 13C-MFA model re-use and exchange [7]. |

Tracing 13C-labeled substrates through metabolic networks is the foundational principle that enables 13C-MFA to provide quantitative insights into the operational rates of metabolic pathways in living cells. The technique's power lies in the synergy between carefully designed tracer experiments, precise analytical measurements of isotopic labeling, and sophisticated computational modeling. As demonstrated in the erythroid differentiation case study, 13C-MFA can reveal critical, functionally validated metabolic shifts that underlie cellular processes. The continued development of standardized formats like FluxML for model sharing [7], robust open-source software like OpenFLUX2 for handling complex experimental designs [8], and comprehensive guidelines for publishing 13C-MFA studies [5] ensures that this methodology will remain a cornerstone for researchers in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and biomedical science.

In the realm of 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), the accurate quantification of intracellular reaction fluxes hinges on clearly defined and experimentally controlled steady-state conditions [1]. Metabolic fluxes represent the in vivo conversion rates of metabolites, providing a dynamic perspective on cellular phenotype that static "omics" data cannot [1] [6]. 13C-MFA has emerged as the primary technique for quantifying these fluxes in various biological systems, from microorganisms to human cells [11] [6]. The power of 13C-MFA lies in integrating data from stable isotope tracer experiments with computational models to infer flux distributions that would otherwise be inaccessible to direct measurement [1]. Central to this methodology are two fundamental assumptions about system stability: metabolic steady state and isotopic steady state. This article delineates the distinctions between these concepts, their specific applications in 13C-MFA variants, and provides detailed protocols for their experimental implementation in research and drug development contexts.

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Metabolic Steady State

Metabolic steady state describes a condition where the net rates of formation and consumption for all intracellular metabolites are balanced, resulting in constant metabolite pool sizes over time [1]. This implies that metabolic fluxes—the flows through biochemical pathways—remain stable during the experimental period. In practical terms, the concentrations of intermediates in central carbon metabolism (e.g., glycolytic intermediates, TCA cycle metabolites) do not exhibit net accumulation or depletion. This steady state is typically maintained in exponentially growing cells where growth conditions are optimized and nutrient limitations are avoided [6]. The metabolic steady state is a foundational assumption for most 13C-MFA approaches, as it allows for the simplification of complex dynamic systems to tractable models with constant flux parameters.

Isotopic Steady State

Isotopic steady state (also called isotope stationarity) represents a condition where the fractional labeling of all metabolite pools remains constant over time [12] [1]. This occurs when the incorporation of the heavy isotope (e.g., 13C) from the labeled tracer has reached equilibrium throughout the metabolic network. At isotopic steady state, the pattern of isotope labeling—whether measured as mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) or positional enrichments—no longer changes, reflecting a balance between the influx of labeled atoms from the tracer and the efflux of labeled atoms through metabolic reactions [4]. The time required to reach isotopic steady state varies significantly depending on the organism, growth rate, and the specific metabolite pool sizes, ranging from hours for microbial systems to days for slower-growing mammalian cells [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Steady-State Conditions in 13C-MFA

| Characteristic | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Constant metabolite concentrations & fluxes over time | Constant isotope labeling patterns over time |

| Governed By | Metabolic reaction rates & pool sizes | Atom transition rates & labeling input |

| Typical Time to Achieve | Several cell doublings | Varies from hours to days |

| Primary Application | Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) |

| Measurement Focus | Extracellular rates & growth kinetics | Mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Design

Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA)

Stationary State 13C-MFA requires both metabolic and isotopic steady state assumptions [1]. This approach involves growing cells on a 13C-labeled substrate until full isotopic equilibrium is reached, typically requiring incubation for more than five residence times to ensure complete isotope mixing [4]. The methodology is particularly powerful for quantifying fluxes in complex networks with parallel pathways, reversible reactions, and metabolic cycles [11]. SS-MFA has been successfully applied to study microbial physiology, plant metabolism, and cancer cell lines [12] [6].

Protocol 1: Implementing SS-MFA for Mammalian Cell Cultures

Experimental Setup

- Culture cells in appropriate medium until exponential growth phase is established.

- Replace medium with identical formulation containing 13C-labeled tracer (e.g., [U-13C]glucose or [1,2-13C]glucose).

- Maintain culture for sufficient duration to reach isotopic steady state (typically 24-72 hours for mammalian cells, depending on doubling time).

Sampling and Quenching

- Collect cells at multiple time points to verify steady-state conditions.

- Rapidly quench metabolism using cold methanol or specialized quenching solutions.

- Separate cells from medium by centrifugation (500 × g, 5 min, 4°C).

Metabolite Extraction

- Resuspend cell pellet in 1 mL of 80% methanol (-20°C) and vortex vigorously.

- Incubate for 15 minutes at -20°C.

- Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer supernatant to a new tube and evaporate solvent under nitrogen stream.

- Store dried extracts at -80°C until analysis.

Data Acquisition

- Reconstitute samples in appropriate solvent for LC-MS or GC-MS analysis.

- Measure mass isotopomer distributions of intracellular metabolites.

- Quantify extracellular substrate consumption and product secretion rates.

Flux Analysis

Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA)

Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) relaxes the requirement for isotopic steady state while maintaining the assumption of metabolic steady state [12] [1]. This approach utilizes time-resolved labeling data collected during the transition toward isotopic steady state. INST-MFA is particularly valuable for systems where achieving isotopic steady state is impractical or where isotopic stationarity provides insufficient information flux estimation, such as in autotrophic organisms or for nitrogen metabolism studies [12].

Protocol 2: INST-MFA for Rapid Kinetic Flux Profiling

Tracer Pulse Design

- Grow cells to exponential phase in standard medium.

- Rapidly introduce 13C-labeled tracer without disrupting metabolic state.

- Collect samples at high temporal resolution (seconds to minutes) immediately after tracer introduction.

Rapid Sampling Protocol

- Use automated sampling systems for high-time-resolution experiments.

- Quench metabolism instantaneously upon sampling.

- Preserve samples at -80°C until extraction.

Analytical Considerations

- Measure both mass isotopomer distributions and absolute concentrations.

- Focus on metabolites with rapid turnover times (e.g., glycolytic intermediates).

- Utilize LC-MS/MS for enhanced sensitivity and specificity.

Computational Modeling

- Implement systems of ordinary differential equations describing isotopomer dynamics.

- Estimate fluxes by fitting simulated labeling time courses to experimental data.

- Apply local approaches (KFP, NSMFRA, ScalaFlux) for subnetwork flux analysis [12].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of SS-MFA vs. INST-MFA

| Parameter | SS-MFA | INST-MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Required Assumptions | Metabolic & isotopic steady state | Metabolic steady state only |

| Experimental Duration | Longer (days) | Shorter (minutes to hours) |

| Data Requirements | Single time point at isotopical stationarity | Multiple time points during labeling kinetics |

| Computational Complexity | Medium | High |

| Best Suited For | Heterotrophic systems | Autotrophic systems, nitrogen metabolism |

| Information Obtained | Global flux map | Localized fluxes with temporal resolution |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | Dual-labeled tracer for improved flux resolution | Precise quantification of PPP flux, glycolytic entry points [4] |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer for comprehensive labeling | Broad assessment of central carbon metabolism [14] |

| [U-13C]Glutamine | Essential amino acid tracer for nitrogen metabolism | Analysis of TCA cycle, reductive carboxylation in cancer cells [6] |

| GC-MS System | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions | Quantification of 13C incorporation into proteinogenic amino acids [4] |

| LC-MS/MS System | High-sensitivity analysis of labile metabolites | Measurement of glycolytic & TCA cycle intermediates [15] |

| INCA Software | Integrated flux analysis platform | Comprehensive 13C-MFA modeling & statistical validation [6] |

| Metran Software | Flux estimation tool using EMU framework | Efficient simulation of isotopic labeling patterns [6] |

The distinction between metabolic steady state and isotopic steady state represents a fundamental conceptual and practical consideration in 13C-MFA experimental design. SS-MFA, requiring both conditions, provides a robust framework for comprehensive flux quantification in established model systems. In contrast, INST-MFA, requiring only metabolic steady state, offers flexibility for studying specialized metabolic scenarios and provides temporal resolution of labeling kinetics. The choice between these approaches should be guided by biological context, experimental constraints, and specific research questions. As 13C-MFA continues to evolve, with applications expanding to human patients and complex disease models, rigorous attention to these foundational assumptions remains paramount for generating physiologically relevant and statistically valid flux measurements [16] [14].

Metabolic flux analysis represents a cornerstone of quantitative systems biology, providing crucial insights into the integrated functional phenotype of living systems by determining the rates of biochemical reactions within metabolic networks [17]. Among the various techniques developed for flux quantification, 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) stands as a gold standard approach, particularly in metabolic engineering and biotechnology [18]. However, 13C-MFA exists within a broader ecosystem of fluxomic methods, each with distinct principles, applications, and limitations. This article provides a systematic comparison of 13C-MFA against three other prominent techniques: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), Isotopically Nonstationary Metabolic Flux Analysis (INST-MFA), and Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis (DMFA). Understanding the relative strengths and optimal application domains of each method is essential for researchers selecting the most appropriate tool for investigating specific biological questions in microbial, plant, or mammalian systems.

Methodological Comparison of Fluxomic Techniques

The core distinction between fluxomic methods lies in their foundational assumptions, data requirements, and computational approaches. The following table provides a systematic comparison of the four methods, highlighting their key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative overview of major fluxomic methods

| Feature | 13C-MFA | FBA | INST-MFA | DMFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Fitting fluxes to isotopic steady-state data [2] | Linear optimization of an objective function [17] | Fitting fluxes to transient isotopic labeling data [2] [19] | Estimating flux changes across multiple time intervals [2] |

| Metabolic Steady State | Required [18] | Required | Required [2] | Not required |

| Isotopic Steady State | Required [2] [19] | Not applicable | Not required; uses transient data [2] [19] | Can be applied, but not assumed |

| Key Data Inputs | Extracellular rates, Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) [17] | Stoichiometric model, exchange constraints, objective function [17] | Time-course MIDs, pool sizes [19] [12] | Multiple sets of extracellular rates/MIDs over time [2] |

| Typical Network Scale | Core metabolism (10s-100s of reactions) [2] | Genome-scale (1000s of reactions) [2] [18] | Core metabolism [12] | Core metabolism |

| Key Output | Accurate, absolute fluxes through central carbon pathways [18] | Predicted flux distribution based on optimization principle [20] | Absolute fluxes, without waiting for isotopic steady state [2] | Dynamic flux maps showing flux changes over time [2] |

| Major Strength | High precision and accuracy for central carbon metabolism [18] | Scalability to genome-wide networks; no need for isotopic tracers [17] [2] | Speed (avoids long incubation times); application to autotrophic systems [2] [12] | Captures dynamic, non-steady-state physiological transitions [2] |

| Major Limitation | Limited to networks where isotopic steady state is achievable [2] | Relies on a pre-defined objective function, which may not reflect biological reality [20] | Computational complexity of solving differential equations [2] [19] | High data demand and computational complexity [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for 13C-MFA

Objective: To quantify absolute intracellular metabolic fluxes at metabolic and isotopic steady state.

Workflow Steps:

- Experimental Design: Select an appropriate 13C-labeled tracer (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) based on the metabolic pathways of interest [2] [21].

- Cell Cultivation: Grow cells in a controlled bioreactor. Replace the natural abundance carbon source with the defined 13C-labeled substrate once the culture reaches metabolic steady state (constant metabolite concentrations and growth rate) [2].

- Isotopic Steady-State Achievement: Continue cultivation until the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites no longer changes (typically requiring several generations) [2].

- Metabolite Quenching & Extraction: Rapidly quench cellular metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol) and perform intracellular metabolite extraction [2].

- Mass Isotopomer Measurement: Analyze the extracted metabolites using GC-MS or LC-MS to obtain Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) data [2] [19].

- Computational Flux Estimation: Use specialized software (e.g., 13CFLUX, Iso2Flux) to find the flux map that minimizes the difference between the simulated and experimentally measured MIDs, subject to stoichiometric constraints [17] [22] [20].

Figure 1: A standard workflow for a 13C-MFA experiment.

Protocol for INST-MFA

Objective: To quantify metabolic fluxes without the need to reach isotopic steady state, enabling faster experiments and studies of autotrophic systems like plants.

Workflow Steps:

- Tracer Pulse: Introduce a 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., 13CO2 for plant studies) to a system already at metabolic steady state [2] [12].

- Rapid Sampling: Collect multiple samples over short time intervals (seconds to minutes) immediately after tracer introduction [2].

- Metabolite Extraction: Rapidly quench and extract metabolites from each sample.

- Time-Course MID Measurement: Analyze the MIDs of intracellular metabolites for each time point using MS [12].

- Flux Estimation with Pool Sizes: Use computational models (e.g., based on Elementary Metabolite Units - EMUs) that incorporate metabolite pool sizes and solve ordinary differential equations to fit the time-course labeling data and estimate fluxes [19] [12].

Protocol for FBA

Objective: To predict genome-scale flux distributions based on stoichiometric constraints and an assumed biological objective.

Workflow Steps:

- Network Reconstruction: Build a genome-scale stoichiometric model (S-matrix) incorporating all known metabolic reactions for the organism [18].

- Define Constraints: Apply constraints based on experimental data (e.g., substrate uptake rates, oxygen consumption) and/or thermodynamic considerations [17].

- Select Objective Function: Define a linear objective function to be optimized (e.g., maximize biomass growth, maximize ATP production, or minimize total flux) [17] [20].

- Linear Programming: Use linear optimization algorithms to find a flux distribution that satisfies the constraints and optimizes the objective function [17] [18].

Protocol for DMFA

Objective: To estimate how metabolic fluxes change over time during a dynamic fermentation process.

Workflow Steps:

- Experiment Segmentation: Divide a non-steady-state culture (e.g., a fed-batch fermentation) into multiple discrete time intervals [2].

- Interval Analysis: For each time interval, measure the extracellular fluxes, such as substrate consumption and product formation rates [2].

- Data Integration: Apply a computational framework that assumes relatively slow flux transients (on the order of hours) and calculates a distinct flux map for each time interval based on the measured data [2]. 13C-DMFA can be performed by integrating isotopic labeling data from multiple time points [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

Successful execution of flux analysis requires a combination of wet-lab reagents and sophisticated computational tools.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and software solutions for fluxomics

| Category | Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, 13C-Glutamine) | Serve as the carbon source for tracing experiments; the specific labeling pattern informs on different pathway activities [2] [21]. |

| Analytical Instruments | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) / Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) | Workhorse platforms for measuring the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of metabolites in 13C-MFA and INST-MFA [2] [19]. |

| Software for 13C-MFA/INST-MFA | 13CFLUX(v3) | A high-performance, open-source platform for both isotopically stationary and nonstationary 13C-MFA, supporting multi-tracer studies and Bayesian analysis [22]. |

| INCA | A widely used software for INST-MFA, implementing the EMU framework [12]. | |

| Iso2Flux | An open-source software for 13C-MFA that includes implementations like parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA) for integrating transcriptomic data [20]. | |

| Software for FBA | COBRA Toolbox / cobrapy | Standard software toolboxes for Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA), enabling FBA and related algorithms [17] [23]. |

| Computational Frameworks | ML-Flux | An emerging machine learning framework that uses neural networks to map isotope patterns to metabolic fluxes, offering rapid computation [21]. |

Logical Decision Framework for Method Selection

Choosing the most appropriate fluxomic method depends on the biological question, the system under study, and practical experimental constraints. The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway.

Figure 2: A decision framework for selecting the most suitable fluxomic method.

13C-MFA, FBA, INST-MFA, and DMFA each offer unique capabilities for quantifying metabolic fluxes. 13C-MFA remains the gold standard for obtaining highly accurate and precise flux maps of core metabolism under steady-state conditions. In contrast, FBA provides a scalable, genome-scale predictive framework that is less dependent on experimental data but relies on the correct specification of an objective function. INST-MFA breaks the key limitation of 13C-MFA by forgoing the need for isotopic steady state, opening doors to studying systems like photosynthetic organisms and enabling faster experiments. Finally, DMFA extends the flux analysis paradigm to dynamic bioprocesses, capturing transient metabolic physiological changes. The choice of method is not a question of which is universally best, but which is the most appropriate tool for the specific biological system, scientific question, and experimental constraints at hand. The ongoing development of more powerful software and integration with machine learning promises to further enhance the accessibility, speed, and scope of all fluxomic methods [21] [22].

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a powerful model-based technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells [11]. By tracing stable isotope-labeled nutrients (e.g., 13C-glucose) through metabolic pathways, 13C-MFA enables researchers to determine the in vivo rates of enzymatic reactions and transport processes that define cellular phenotype [6] [1]. Unlike other omics technologies that provide static snapshots of cellular components, 13C-MFA delivers dynamic information about the functional activity of metabolic networks, making it indispensable for both basic research and applied biotechnology [11]. Over the past two decades, 13C-MFA has evolved from a specialized methodology used by a handful of expert groups to a standardized tool with diverse applications across metabolic engineering, systems biology, and biomedical research [11] [6].

The core principle of 13C-MFA involves feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates, measuring the resulting isotope labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites, and using computational modeling to infer the metabolic flux map that best explains the experimental data [1]. This approach provides significant advantages over alternative flux estimation methods like flux balance analysis, as it can accurately resolve fluxes through parallel pathways, metabolic cycles, and reversible reactions [11]. With the development of user-friendly software tools and standardized protocols, 13C-MFA is now accessible to a broader scientific community, enabling unprecedented insights into cellular metabolism under various physiological and pathological conditions [6].

Key Applications of 13C-MFA

13C-MFA has become a fundamental tool across multiple research domains, each leveraging its capability to quantify metabolic phenotype with precision. The table below summarizes the core application areas and their specific focus.

Table 1: Key Application Areas of 13C-MFA

| Application Area | Primary Research Focus | Representative Organisms/Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Engineering | Optimizing cell factories for bioproduction; Revealing pathway limitations [11] [1] | E. coli, Yeast, Industrial cell lines |

| Biomedical Research | Understanding metabolic rewiring in disease; Identifying therapeutic targets [6] | Cancer cells, Neural cells, Immune cells |

| Systems Biology | Quantitative modeling of cellular metabolism; Understanding metabolic regulation [11] [1] | Model organisms (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis) |

| Biotechnology | Improving product yields and cellular productivity in bioprocesses [11] | Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, Microbial production strains |

Metabolic Engineering and Biotechnology

In metabolic engineering, 13C-MFA serves as a cornerstone for rational design of microbial cell factories. By quantifying carbon routing through central metabolism, researchers can identify flux bottlenecks, quantify the yield of alternative pathways, and validate the functional impact of genetic modifications [11]. This has proven crucial for optimizing the production of valuable compounds such as acetaldehyde, isopropanol, and vitamin B2 [1]. For instance, in E. coli and yeast, 13C-MFA has been used to elucidate the relative contributions of glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and the Entner-Doudoroff pathway, guiding engineering strategies to enhance precursor supply for target molecules [13]. In industrial biotechnology, 13C-MFA is applied to cell lines like Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells to understand their metabolic physiology and engineer more efficient phenotypes for recombinant protein production [11] [6].

Biomedical and Disease Research

The application of 13C-MFA in biomedical research, particularly in cancer biology, has transformed our understanding of metabolic reprogramming in disease states. The technique has been instrumental in quantifying the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) and uncovering other dysregulated pathways in cancer cells, including reductive glutamine metabolism, serine and glycine biosynthesis, and one-carbon metabolism [6]. By providing absolute flux values, 13C-MFA moves beyond qualitative gene expression data to reveal how cancer cells fundamentally reorganize their metabolic networks to support rapid proliferation, survival, and resistance to therapy. Beyond oncology, 13C-MFA is increasingly applied to study metabolic alterations in neural cells, immune cells, and in pathological conditions such as diabetes and retinal degenerative diseases [1]. This detailed flux information helps in identifying critical metabolic dependencies that can be exploited for therapeutic intervention.

Experimental Protocol: 13C-MFA in Cancer Cell Metabolism

This protocol details a standard workflow for employing stationary state 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) to investigate the metabolic fluxes of cancer cells in culture, such as HeLa or MCF-7 cells [6] [1].

Stage 1: Cell Culture and Tracer Experiment

Objective: To cultivate cancer cells and introduce a 13C-labeled substrate for metabolic labeling.

Materials:

- Cancer cell line of interest (e.g., MCF-7, HeLa)

- Appropriate cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM, RPMI-1640)

- 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose)

- Cell culture flasks/dishes

- Standard cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2)

Procedure:

- Culture Expansion: Maintain cells in standard growth medium and passage as needed to ensure logarithmic growth.

- Experimental Seeding: Seed an appropriate number of cells into multiple culture vessels to achieve a desired initial cell density (e.g., 0.5 × 10^6 cells per T-25 flask).

- Tracer Introduction:

- Once cells are attached and stabilized, remove the standard growth medium.

- Wash the cell monolayer gently with pre-warmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Add fresh medium containing the 13C-labeled tracer. A common starting point is 100% [U-13C]glucose as the sole glucose source.

- Return cells to the incubator.

- Sampling: Culture cells for a sufficient duration to achieve isotopic steady state in central metabolites (typically 24-48 hours for many mammalian cell lines). Harvest cells and medium at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 24, and 48 hours) for subsequent analysis.

Stage 2: Data Collection and Measurement

Objective: To quantify external metabolic rates and measure isotopic labeling.

Materials:

- Hemocytometer or automated cell counter

- Metabolite concentration analyzer (e.g., HPLC, Bioprofile Analyzer)

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) system

- Quenching solution (e.g., cold methanol)

- Derivatization reagents (e.g., MSTFA for GC-MS)

Procedure:

- Growth and External Rate Quantification:

- At each sampling point, detach and count cells to determine cell density.

- Collect culture medium and analyze concentrations of key metabolites (glucose, lactate, glutamine, glutamate, amino acids).

- Calculate the specific growth rate (µ, 1/h) using the exponential growth equation and external metabolite rates (nmol/10^6 cells/h) using established formulas [6].

- Isotopic Labeling Measurement:

- For intracellular labeling analysis, quickly quench cell metabolism (e.g., with cold methanol) and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Derivatize metabolites (e.g., proteinogenic amino acids from hydrolyzed cell pellets) for analysis by GC-MS.

- Acquire mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for the fragments of interest.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| [U-13C]Glucose | Tracer for mapping carbon fate through glycolysis, TCA cycle, and anabolic pathways [6] | Commonly used as 100% tracer or in mixtures |

| GC-MS Instrument | Analytical workhorse for measuring Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) [13] [1] | Provides high-sensitivity data for 13C-MFA |

| Metabolic Network Model | Computational representation of the biochemical reactions used for flux simulation and estimation [11] | Must include atom transitions for 13C-MFA |

| Software (INCA, Metran) | User-friendly platforms for flux estimation, goodness-of-fit, and confidence interval analysis [6] | Implements the EMU framework for efficient calculation |

Stage 3: Computational Flux Analysis

Objective: To estimate intracellular metabolic fluxes and their confidence intervals from the collected data.

Materials:

- 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA, Metran, OpenMebius)

- Metabolic network model of central carbon metabolism

- Computer workstation

Procedure:

- Model Definition: Import a stoichiometric model of central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, etc.) that includes atom transition information for each reaction [13].

- Data Input: Provide the software with:

- The measured external flux data (growth rate, uptake/secretion rates).

- The uncorrected mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) from GC-MS [11].

- The labeling pattern of the input tracer(s).

- Flux Estimation:

- The software performs a non-linear least-squares regression to find the set of intracellular fluxes that best fit the measured MIDs.

- The optimization minimizes the residual sum of squares (RSS) between the simulated and measured data [13].

- Statistical Analysis:

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams, created using the specified color palette and contrast guidelines, illustrate the core workflow of 13C-MFA and the central metabolic pathways it probes.

13C-MFA Core Workflow

Central Carbon Metabolism Pathways

Executing 13C-MFA: A Step-by-Step Protocol from Cell Culture to Flux Estimation

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a cornerstone technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells, providing critical insights for metabolic engineering, bioprocess optimization, and biomedical research [24] [6]. The precision and accuracy of flux determinations depend significantly on the strategic selection of isotopic tracers and experimental design. A key advancement in the field is the use of parallel labeling experiments (COMPLETE-MFA), where multiple complementary tracer experiments are conducted and analyzed simultaneously to dramatically improve flux resolution [25] [26]. This protocol outlines systematic approaches for selecting optimal tracers and designing parallel labeling strategies to maximize flux information content while considering practical experimental constraints.

Tracer Selection Fundamentals

Essential Concepts in 13C-MFA

The core principle of 13C-MFA involves feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates and tracing the incorporation of labeled carbon atoms through metabolic pathways. As these substrates undergo enzymatic reactions, carbon atoms are rearranged, creating specific labeling patterns in downstream metabolites that can be measured using techniques such as mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [24] [6]. The measured labeling data are then integrated with a metabolic network model to compute intracellular fluxes through a parameter estimation process [6].

The selection of an appropriate isotopic tracer is crucial because different tracers illuminate different metabolic pathways with varying effectiveness. A well-chosen tracer produces distinct labeling patterns for alternative metabolic routes, enabling accurate flux quantification, while a poor tracer choice may fail to resolve fluxes between competing pathways [25].

Evaluation Metrics for Tracer Performance

Two key metrics have been developed to quantitatively evaluate tracer performance:

Precision Score (P): This metric quantifies the improvement in flux precision for a given tracer experiment relative to a reference tracer. It is calculated as the average of individual flux precision scores (p_i) for n fluxes of interest [25]:

where UB95,i and LB95,i represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals for flux i. A precision score >1 indicates improved performance over the reference tracer.

Synergy Score (S): This metric quantifies the additional information gained by combining multiple parallel labeling experiments compared to analyzing them separately. It is calculated as [25]:

where pi,1+2 is the precision score for the parallel experiment, and pi,1 and p_i,2 are the precision scores for individual experiments. A synergy score >1 indicates a greater-than-expected gain in flux information through complementary tracer use.

Optimal Tracer Selection

Performance of Single Tracers

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Select Glucose Tracers

| Tracer Type | Example | Relative Cost | Flux Precision | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singly labeled | [1-13C]glucose | Low (~$100/g) [4] | Moderate | Basic flux mapping |

| Doubly labeled | [1,2-13C]glucose | High (~$600/g) [4] | High | Overall central metabolism |

| Position-specific | [1,6-13C]glucose | High | Very high | Glycolysis and PPP |

| Uniformly labeled | [U-13C]glucose | Moderate | Variable | Comprehensive coverage |

| Mixture | 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose | Moderate | Moderate | Common practice benchmark |

Research evaluating thousands of tracer schemes has identified doubly 13C-labeled glucose tracers as consistently superior for single-tracer experiments [25]. The best-performing single tracers include [1,6-13C]glucose, [5,6-13C]glucose, and [1,2-13C]glucose, which produce the highest flux precision scores across diverse metabolic networks. These tracers outperform the commonly used tracer mixture of 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose [25].

An important finding is that pure glucose tracers generally perform better than glucose tracer mixtures for single-tracer experiments [25]. This challenges conventional practices of using tracer mixtures and highlights the value of systematic tracer evaluation.

Tracer Selection for Specific Applications

Different metabolic systems and research questions may benefit from specialized tracer selection:

- Mammalian cell systems: For cancer metabolism studies, [1,2-13C]glucose has been identified as excellent for resolving the phosphoglucoisomerase flux and other fluxes in central carbon metabolism [27].

- Microbial systems: In E. coli studies, different tracers excel for different parts of metabolism. The mixture 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose performs best for upper metabolism (glycolysis, PPP), while [4,5,6-13C]glucose and [5-13C]glucose optimize flux resolution in lower metabolism (TCA cycle, anaplerotic reactions) [26].

- COMPLETE-MFA: For parallel labeling approaches, the optimal pair is [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose, which combined improve flux precision nearly 20-fold compared to the standard 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose mixture [25].

Parallel Labeling Strategies

COMPLETE-MFA Framework

The COMPLETE-MFA (COMPlementary Parallel Labeling Experiments Technique for Metabolic Flux Analysis) approach represents the current gold standard in fluxomics [26]. This methodology involves:

- Designing multiple tracer experiments with complementary labeling patterns

- Growing cells in parallel under identical conditions but with different tracers

- Collecting labeling data for each experiment

- Simultaneously fitting all labeling datasets to a single metabolic model

The power of COMPLETE-MFA stems from its ability to provide more comprehensive labeling information, improving both flux precision and flux observability (the number of independent fluxes that can be resolved) [26]. This approach is particularly valuable for quantifying exchange fluxes (reversible reactions) and resolving parallel pathway activities that are difficult to characterize with single tracers.

Implementation Protocol

Table 2: Protocol for Parallel Labeling Experiments

| Step | Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Experimental Design | Select 2-4 complementary tracers based on precision scores | Balance information content with experimental cost [27] |

| 2. Culture Conditions | Establish reproducible, controlled growth conditions | Use identical inoculum, medium composition, and environmental parameters [26] |

| 3. Tracer Administration | Add specific tracers to parallel cultures | Use equal carbon amounts; verify tracer purity and composition |

| 4. Sampling | Collect samples during metabolic and isotopic steady state | For microbial systems: mid-exponential phase; ensure >5 residence times for isotope steady state [4] |

| 5. Labeling Measurement | Analyze mass isotopomer distributions | Use GC-MS or LC-MS platforms; include technical replicates |

| 6. Data Integration | Simultaneously fit all labeling datasets | Use appropriate software (INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX); validate model fit [22] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the COMPLETE-MFA process:

Scaling and Applications

Large-scale parallel labeling studies have demonstrated the remarkable capabilities of COMPLETE-MFA. One landmark study successfully integrated 14 parallel labeling experiments in E. coli, utilizing more than 1200 mass isotopomer measurements to determine highly precise metabolic fluxes [26]. This massive-scale analysis confirmed that:

- No single tracer is optimal for all parts of a metabolic network

- Tracers that perform well for upper metabolism (glycolysis, PPP) often perform poorly for lower metabolism (TCA cycle, anaplerotic reactions), and vice versa

- Parallel labeling significantly improves the resolution of exchange fluxes, which are particularly challenging to estimate with single tracers

For most applications, 2-4 parallel experiments provide an excellent balance between experimental effort and flux information gain. The specific number should be determined based on the complexity of the metabolic network and the required flux precision.

Technical Considerations and Tools

Analytical Methods

Accurate measurement of isotopic labeling is essential for successful 13C-MFA. The primary analytical platforms include:

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): The most widely used platform for 13C-MFA, providing robust quantification of proteinogenic amino acid labeling patterns [4].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Increasingly popular, especially with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes, offering enhanced coverage of central carbon metabolites [28].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): Provides positional labeling information but generally with lower sensitivity than MS methods [4].

Recent advances in LC-MRM-MS methodologies have significantly improved the coverage of unstable metabolites in central carbon metabolism. A dual derivatization/non-derivatization strategy using reagents such as N-Methylphenylethylamine (MPEA) has enabled precise flux analysis of 101 metabolites, including challenging compounds like α-keto acids, nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), and deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) [28].

Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX, OpenFLUX | Flux estimation from labeling data [22] |

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]glucose, [1,6-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine | Generate specific labeling patterns [25] |

| Analytical Standards | Stable isotope-labeled amino acids, organic acids | Quantification and method development |

| Derivatization Reagents | N-Methylphenylethylamine (MPEA), 3-NPH | Stabilize metabolites for improved MS detection [28] |

Modern 13C-MFA relies on sophisticated computational tools that implement the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework to efficiently simulate isotopic labeling in complex metabolic networks [22] [6]. Key software packages include:

- INCA: A user-friendly software for both isotopically stationary and non-stationary MFA [24]

- Metran: Integrated with MATLAB, supports comprehensive flux analysis [24]

- 13CFLUX: High-performance software supporting advanced statistical analysis [22]

These tools have dramatically increased the accessibility of 13C-MFA for researchers without extensive computational backgrounds, enabling broader adoption across biological research fields.

Strategic selection of isotopic tracers and implementation of parallel labeling experiments represent the current state-of-the-art in 13C metabolic flux analysis. The systematic approach outlined in this protocol enables researchers to design more informative labeling studies that yield higher-resolution flux maps. Key principles include:

- Prioritizing doubly-labeled glucose tracers such as [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose for optimal flux resolution

- Implementing COMPLETE-MFA with complementary tracers to overcome the limitations of single-tracer experiments

- Leveraging advanced computational tools and analytical methodologies for comprehensive flux quantification

As 13C-MFA continues to evolve, these tracer selection and experimental design strategies will play an increasingly important role in elucidating metabolic networks across diverse biological systems, from engineered microbes to human diseases.

Within the framework of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) research, achieving and validating metabolic and isotopic steady-state is the foundational prerequisite for obtaining accurate, quantifiable intracellular flux maps [11] [6]. This state ensures that the intracellular reaction rates and metabolite concentrations are constant, and that the incorporation of the 13C-label from the tracer substrate has stabilized throughout the metabolic network [1]. This protocol details the methodologies for designing and executing cell culture experiments to establish these steady-state conditions, which are critical for reliable flux determination in both microbial and mammalian systems, including applications in cancer biology and biotechnology [6] [4].

Defining Steady-State in 13C-MFA

For 13C-MFA, two distinct but concurrent steady-states must be established:

- Metabolic Steady-State: The rates of all intracellular reactions (fluxes) and the concentrations of all intracellular metabolites are constant over time [1] [8]. This is typically achieved in continuous chemostat cultures or in batch cultures during the exponential growth phase where the growth rate is constant [6] [4].

- Isotopic Steady-State: The fractional enrichment of 13C in all metabolite pools within the network has reached a constant value. The labeling patterns no longer change with time, reflecting a balance between the influx of labeled atoms from the tracer and the efflux of metabolites [1] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and the pivotal role of steady-state within the 13C-MFA process.

Figure 1. The 13C-MFA Workflow. This chart outlines the key stages of a 13C-MFA study, highlighting that successful flux calculation is contingent upon the verification of both metabolic and isotopic steady-state.

Quantitative Criteria for Steady-State

The criteria for confirming steady-state are quantitative and must be rigorously assessed prior to sample collection for flux analysis.

Table 1: Quantitative Criteria for Verifying Steady-State Conditions

| Parameter | Metric for Metabolic Steady-State | Metric for Isotopic Steady-State | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Growth | Constant exponential growth rate (µ) [6]. Doubling time (t~d~) is stable [6]. | N/A | Cell counting, optical density, dry cell weight. |

| Nutrient & Metabolite Pools | Constant uptake and secretion rates. Linear changes in metabolite concentrations over time in batch culture [6]. | N/A | HPLC, GC-MS, or enzymatic assays of culture medium. |

| Isotopic Labeling | N/A | Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of intracellular metabolites are constant over time [1] [4]. | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR. |

| Key Validation | Carbon and electron balances close within acceptable limits (e.g., 95-105%) [11]. | MIDs of key metabolites (e.g., proteinogenic amino acids) from duplicate samples taken at different time points are statistically identical [29]. | Mass spectrometry with statistical comparison (e.g., t-test). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Metabolic Steady-State in Batch Culture

This protocol is suitable for many adherent and suspension mammalian cell lines, as well as microbial cultures.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Cell Line: e.g., CHO, HEK293, or E. coli.

- Basal Medium: Appropriate for the cell type (e.g., DMEM, RPMI-1640, M9).

- 13C-Labeled Tracer: e.g., [U-13C~6~] Glucose, [1,2-13C] Glucose.

- Supplements: FBS, glutamine, antibiotics as required.

- Bioreactor or Shake Flasks: For controlled cultivation.

- Cell Counter or Spectrophotometer: For monitoring cell density.

II. Procedure

- Pre-culture: Inoculate cells into unlabeled medium and grow until the mid-exponential phase is reached.

- Inoculation: Dilute the pre-culture into fresh, pre-warmed medium containing the chosen 13C-labeled tracer. Ensure the initial cell density is appropriate for exponential growth (e.g., 0.05-0.1 OD~600~ for microbes; 2-5 x 10^5^ cells/mL for mammalian cells).

- Environmental Control: Maintain constant temperature, pH, and agitation throughout the experiment.

- Monitoring Growth: Take periodic measurements of cell density (OD~600~ or direct cell count) and plot the natural logarithm of cell density versus time.

- Calculating Growth Rate: Calculate the growth rate (µ) using the formula: ( \mu = \frac{\ln(N{x,t2}) - \ln(N{x,t1})}{\Delta t} ) where ( N_{x,t} ) is the cell number at time t [6]. A stable µ over multiple time intervals confirms metabolic steady-state for growth.

- Monitoring Extracellular Fluxes: Periodically sample the culture medium and measure the concentrations of key substrates (e.g., glucose, glutamine) and products (e.g., lactate, ammonium). Calculate the consumption/production rates using the formula for exponentially growing cells: ( ri = 1000 \cdot \frac{\mu \cdot V \cdot \Delta Ci}{\Delta Nx} ) where ( ri ) is the rate (nmol/10^6^ cells/h), V is culture volume (mL), and ( \Delta C_i ) is the change in metabolite concentration (mmol/L) [6]. Constant rates confirm metabolic steady-state for extracellular fluxes.

Protocol 2: Validating Isotopic Steady-State

This protocol runs concurrently with Protocol 1 once the metabolic steady-state is established.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Quenching Solution: Cold methanol or saline (e.g., 0.9% NaCl) at -40°C.

- Extraction Solvent: Methanol/water or chloroform/methanol mixtures.

- Derivatization Reagents: e.g., MTBSTFA (for GC-MS), Methoxyamine hydrochloride (for methoximation).

- GC-MS or LC-MS System: For mass isotopomer analysis.

II. Procedure

- Time-Course Sampling: Once metabolic steady-state is confirmed, collect cell samples at multiple, spaced time points (e.g., t=24h, 36h, 48h for mammalian cells; or 2-3 consecutive residence times for microbes).

- Rapid Quenching and Metabolite Extraction:

- Rapidly transfer a known volume of culture to a pre-chilled quenching solution to halt metabolic activity.

- Pellet cells by centrifugation.

- Extract intracellular metabolites using an appropriate solvent system (e.g., 40:40:20 methanol:acetonitrile:water).

- Centrifuge to remove cell debris and collect the supernatant for analysis.

- Sample Preparation for GC-MS:

- Dry the metabolite extract under a gentle stream of nitrogen or in a vacuum concentrator.

- Derivatize the metabolites to increase volatility (e.g., methoximation followed by silylation).

- Reconstitute in a suitable solvent for GC-MS injection.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Inject samples and acquire mass spectra for target metabolites (e.g., proteinogenic amino acids from hydrolyzed biomass or organic acids).

- Record the mass isotopomer distribution (MID), which is the fractional abundance of the M+0, M+1, M+2, ... M+n isotopomers for each metabolite.

- Data Comparison:

- Plot the MIDs of key metabolites (e.g., alanine, glutamate, serine) from the different time points.

- Isotopic steady-state is confirmed when the MIDs from consecutive time points show no statistically significant difference (assessed by a method such as a chi-square test).

The relationship between the two steady-states and the process of isotopic labeling is sequential, as shown below.

Figure 2. Sequential Progression to Full Steady-State. Metabolic steady-state must be established before meaningful isotopic labeling can begin. Isotopic steady-state is reached after sufficient time for the tracer to fully incorporate into all relevant metabolite pools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function/Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Carbon source for labeling metabolic networks; different labeling patterns probe different pathways [6] [4]. | [1,2-13C] Glucose, [U-13C~6~] Glucose, [U-13C~5~] Glutamine. |

| Culture Media & Supplements | Provide nutrients and maintain physiological conditions for cell growth during labeling. | Custom glucose-free DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine. |

| Quenching & Extraction Solvents | Rapidly halt metabolic activity and extract intracellular metabolites for analysis. | Cold methanol (-40°C), methanol/acetonitrile/water mixtures. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemically modify metabolites to make them volatile for GC-MS analysis. | N-methyl-N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA). |

| Software for Flux Calculation | Perform computational flux estimation from labeling data and network models. | INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX2, 13CFLUX2 [6] [8]. |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Insufficient Labeling: If isotopic steady-state is not achieved, ensure the culture is growing healthily and consider increasing the incubation time. For plant systems, reducing light intensity can minimize dilution from unlabeled CO~2~ fixation [29].

- Metabolic Shifts: Avoid sampling too late in batch culture when nutrients are depleted and metabolism shifts. Use data from the exponential phase only.

- Data Quality: Always report uncorrected mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) and standard deviations for measurements to allow for reproducibility and verification [11].

- Experimental Design: For enhanced flux resolution, consider using Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLEs) with multiple different tracers, which can be integrated and analyzed using software like OpenFLUX2 [8].

Within the framework of 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), sample preparation is a critical foundational step that directly determines the quality and reliability of the resulting flux map. The overarching goal of 13C-MFA is to quantitatively describe cellular fluxes, thereby elucidating metabolic phenotypes and functional behavior following genetic or environmental perturbations [2] [30]. This process involves culturing cells with a 13C-labeled substrate, such as [1,2-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glucose, allowing the tracer to be incorporated into the metabolic network until an isotopic steady state is achieved [2] [31].

The quenching and extraction phases are designed to capture a snapshot of the intracellular metabolic state that accurately reflects the in vivo condition. Any deviation or delay can cause significant changes in metabolite levels and labeling patterns, leading to incorrect flux estimations [11]. This protocol details robust, widely adopted methods for sample preparation tailored specifically for 13C-MFA, ensuring the accurate measurement of isotopic labeling essential for computational flux modeling [2] [32].

The sample preparation process for 13C-MFA, from culture to analysis, follows a structured sequence to preserve metabolic fidelity. The diagram below illustrates the key stages:

Protocols for Sample Preparation

Quenching

The immediate cessation of all metabolic activity, known as quenching, is the most critical step for capturing an accurate snapshot of intracellular metabolites.

- Objective: To instantaneously halt all enzymatic activity, preserving the in vivo metabolite concentrations and labeling distributions [32].

- Key Consideration: The quenching method must be rapid and effective while avoiding metabolite leakage from cells, which can lead to significant underestimation of intracellular concentrations [32].

Detailed Protocol: Cold Methanol Quenching

This is a widely used and effective method for microbial and mammalian cells [32].